Abstract

Background

The anterior-cruciate-ligament (ACL) contains mesenchymal stem cells (ACL-MSCs), suggesting the feasibility of regenerative treatments of this tissue. The immortalization of isolated cells results in cell-lines applicable to develop cell-based therapies. Immortal cell lines eliminate the need for frequent cell isolation from donor tissues. The objective of this study was to characterize cell lines that were generated from isolated ACL-MSCs using TERT gene transfer.

Methods

We isolated ACL-MSCs from human ACLs derived at the time of ACL reconstruction surgery or total knee arthroplasty. We generated cell lines and compared them to non-immortalized ACL-MSCs. We assessed the cellular morphology and we detected surface antigen expression. The resistance to senescence was inferred using the beta galactosidase activity. Histology, immunohistochemistry, and reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) were used to evaluate the multilineage differentiation capacity.

Results

The morphology of hTERT-ACL-MSCs was similar to ACL up to the last assessment at passage eight. We detected a strong surface expression of CD44, CD90, CD105, and STRO-1 in hTERT-ACL-MSCs. No substantial reduction in the ATP activity was observed in hTERT-ACL-MSCs.

Conclusion

Cell lines generated from ACL-MSCs maintain their morphology, surface antigen expression profile, and proliferative capacity; while markers of senescence appear to be reduced. These cell-lines maintained their multilineage differentiation capacity. The demonstrated model systems can be used for further development of new cell-based regenerative approaches in anterior cruciate ligament research, which may lead to new therapeutic strategies in the future.

Keywords: Anterior cruciate ligament, Mesenchymal stem cells, Immortalization, Senescence, Multilineage differentiation

At a glance of commentary

Scientific background on the subject

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) contains mesenchymal stem cells. Immortalization of those cells results in cell-lines, which might be used for regenerative therapies in the future. The objective of this study was to characterize these ACL-derived cell-lines.

What this study adds to the field

The study demonstrates that cell-lines generated from ACL-derived stem cells maintain their morphology, surface antigen expression profile, and proliferative capacity while markers of senscence are reduced. The developed cell-lines maintained their multilineage differentiation capacity. The demonstrated model can be used for further development of new cell-based regenerative approches in ACL research.

Injuries to the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) result in a gross destabilization of the joint and the development of osteoarthritis. The functional restoration of the ligament is a key component in the prevention of secondary meniscal tears [1], [2]. The current standard of care is the surgical replacement of the torn ACL with an autologous semitendinosus or patellar tendon graft [3], [4]. However, high-level evidence suggests that the current standard of care is not resulting in substantially improved subjective outcomes [5], [6]. Further radiographic signs of osteoarthritis are observed in a high frequency after ACL injury and reconstruction [7]. In order to improve outcomes after ACL injury, novel regenerative therapies are being explored, that might allow restoring the proprioceptive nerve functions of the native ACL and omitting the harvest of an autologous tendon graft.

Multipotent mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) might be used for the development of cell-based regenerative therapies. They can be isolated from a variety of different tissues including bone marrow, adipose tissue, trabecular bone, and tendon [8], [9], [10], [11]. We have recently shown that cells isolated from torn ACLs of young donors possess a surface antigen expression profile highly similar to those of bone-marrow-derived MSCs (BMSCs) and that they were able to undergo multilineage differentiation [12], which qualifies them as MSC types [13]. Thus, the use of ACL-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ACL-MSCs) for regenerative therapies of the injured ACL appears attractive. However, ACL-MSCs can only proliferate in vitro for a limited number of times. By reducing the tendency to senescence using immortalization techniques, cell lines can be created. Those cell lines can improve the design and development of regenerative therapies by limiting the need of cell-isolations from donor tissues and reducing the variability introduced by different donors.

In this study, we have used human TERT gene transfer (encoding Telomerase reverse transcriptase) to immortalize ACL-MSCs derived from one young and one old donor. We hypothesized that the created cell lines (hTERT-ACL-MSCs) maintain the cellular morphology, surface antigen expression profile, and proliferative capacity of naive non-immortalized ACL-MSCs. Further we assessed, whether ACL-MSC cell lines maintain their capacity for multilineage differentiation.

Material and methods

Patient characteristics and tissue collection

ACL tissue was obtained from one young (17 years) and one old (73 years) ACL donor at the time of ACL reconstruction or joint replacement surgery, respectively; according to the protocol approved by our university's Ethics Committee and after informed consent of the patients and parents in case of minors.

Isolation and culture of ACL-MSCs

ACL-MSCs were isolated using collagenase digestion [12]. Tissue specimens were cut into smaller pieces followed by 12.5 U/μl collagenase NB4 (Serva Electrophoresis GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany) in complete medium consisting of Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium DMEM/Ham's F12 (PAA), 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (PAA Laboratories GmbH, Coelbe, Germany), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (PAA) and 50 mg/ml l-ascorbic acid 2-phosphate (Sigma Aldrich GmbH, Taufkirchen, Germany) for 18 h. The released cells were separated from tissue debris using a cell strainer, pelleted at 1200 g for 5 min, resuspended in complete medium, and seeded in 75 cm2 flasks. For all subsequent differentiation protocols, cells were cultivated in an incubator at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in a humidified atmosphere with media changes every 2–3 days. Cells were passaged using 1% trypsin (PAA) for 5 min for detachment, an equal volume of complete medium to stop the reaction, centrifugation at 1200 g for 5 min to pellet cells, and resuspension in complete medium, after which the cells were seeded at a minimal density of 5 × 103 per ml in cell culture flasks.

Immortilization of ACL-MSCs

The viral overexpression of TERT (encoding human telomerase reverse transcriptase; hTERT) was used to immortalize third passage ACL-MSCs. The gene transfer was performed using a lentiviral vector, as previously described [14], [15].

Cell proliferation assay

The quantification of adenosine 5′ triphosphate (ATP) was used to assess the cell proliferation rate. The sensitive luminometric Cell Titer Glo® assay system (Promega, Mannheim, Germany) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, first passage ACL-MSCs were seeded at 1000 cells per well in 96 well plates (Thermo Fischer Scientific Nunc, Langenselbold, Germany) and cultured in 100 μL complete DMEM/F-12 media per well for 13 days, with media changes every 2 days. At days 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 13 the luminescence of 10 wells per cell type and donor was measured for 0.1 s in a luminometer after an equal volume of Cell Titer-Glo® Reagent was added per well followed by 5 min incubation at room temperature.

β-Galactosidase staining

Senescent cells were identified as previously described using the histological visualization of senescence-associated endogenous β-galactosidase activity [16], [17]. Briefly, following two washing steps with PBS (phosphate buffer solution), cells were fixed for 5 min in 2% (v/v) formaldehyde: 0.2% (v/v) glutaraldehyde (1:1). Following an additional PBS wash, cells were incubated with freshly prepared β-galactosidase staining solution at 37 °C without extra addition of carbon dioxide for 16 h. Subsequently, the monolayer was washed twice with PBS for 5 min, rinsed with deionized water and analyzed microscopically.

Chondrogenic differentiation

Chondrogenic differentiation was performed in a pellet culture system, as previously described [18]. Third passage cells were detached from the plastic surface of culture flasks using trypsin digestion, counted and 2.5 × 105 cells were transferred in 50 ml canonical tubes containing 500 μl of either chondrogenic or control media, followed by centrifugation at 1500 g. Pellets were cultured in DMEM High Glucose medium supplemented with 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 40 ng/ml l-proline, 50 ng/ml l-ascorbic acid 2-phosphate sesquimagnesium salt hydrate, 100 ng/ml pyruvate, 100 nM dexamethasone, 1% ITS (all Sigma-Aldrich, Schnelldorf, Germany), and human TGF-β1 (R&D Systems) for 28 days with the caps slightly opened to enable gas exchange. Control pellets were cultured in the absence of TGF-β1. RT-PCR of the chondrocyte marker genes ACAN (encoding aggrecan core protein), BGN (encoding biglycan), COMP (encoding cartilage oligomeric matrix protein) FMOD (encoding fibromodulin), as well as COL2A1 (encoding collagen alpha-1(II) chain) were used to gauge the degree of chondrogenic differentiation. COL10A1 (encoding collagen alpha-1(X) chain) expression was used to determine the degree of chondrocyte hypertrophy. Further qualitative histological assessment of alcian blue histology and type II collagen immunohistochemistry was performed.

Osteogenic differentiation

Osteogenic differentiation was performed in a monolayer culture system as previously described with slight modifications [18]. Cells were cultured in DMEM High Glucose medium containing 10% FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 10 ng/ml bone morphogenetic protein-2 (kindly provided by Prof. Dr. Walter Sebald, Emeritus Chair of Physiological Chemistry, Faculty of Medicine, University of Wuerzburg, Germany), 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 50 ng/ml l-ascorbic acid 2-phosphate sesquimagnesium salt hydrate, and 100 nM dexamethasone (all Sigma Aldrich GmbH) for 28 days. Control cells were cultured in DMEM High Glucose containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin only. RT-PCR of the osteocyte-specific marker gene ALPL (encoding alkaline phosphatase, tissue-nonspecific isozyme) and the qualitative assessment of alkaline phosphatase and alizarin red positive areas were performed to gauge the degree of osteogenic differentiation.

Adipogenic differentiation

Adipogenic differentiation was performed in a monolayer culture system according to a modified protocol described before [18]. Cells were incubated with DMEM High Glucose containing 10% FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 1 μg/ml insulin, 100 μM indomethacin, 0.5 mM 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine, and 1 μM dexamethasone (all Sigma Aldrich) for a total time of 21 days. Control cells were cultured in DMEM High Glucose containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin only. RT-PCR of the adipocyte-specific marker genes LPL (encoding lipoprotein lipase) and PPARG (encoding peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ), as well as the qualitative assessment of oil red O positive areas were performed to gauge the degree of adipogenic differentiation.

RNA isolation and RT-PCR

RNA was isolated using the NucleoSpin© RNA II kit (Machery-Nagel GmbH, Dueren, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The pellets of chondrogenic cultures were previously homogenized in the first buffer of the respective kit using a pestle. 1 μg of isolated RNA was transcribed into cDNA using the BioScript™ kit (Bioline GmbH, Luckenwalde, Germany) with random hexamer primers (Life Technologies GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocols. Gene expression was analyzed using RT-PCR with reaction mixtures containing 3 μl 10x reaction buffer (shipped with the MangoTaq™ from Bioline), 1 μl 10 mM dNTP mixture (Bioline), 1 μl of each forward and reverse primer corresponding to a concentration of 5 μM (See Table 1 for primers) and 3 μl MangoTaq™ polymerase (5000 U/ml, Bioline) and 1 μl of cDNA in 21.9 μl distilled water. The PCR was started by an initial denaturation step at 94 °C for 3 min followed by cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 45 s, primer annealing for 45 s with primer specific temperatures illustrated in Table 1, and an elongation step at 72 °C for 1 min. Subsequent agarose gel electrophoresis was performed using 1.5% agarose gels (Merck) containing 0.5 μg/l ethidium bromide (AppliChem GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany) and 0.5x TBE buffer at 0.9 V/cm of gel length. Gels were documented photographically using the Bio Profile software (LTF, Wasserburg, Germany) and analyzed densitometrically using the GelAnalyzer software (http://www.gelanalyzer.com). For all targeted gene expression analyses EEF1A1 (encoding Elongation factor 1-alpha) was used as housekeeping gene.

Table 1.

Primers and PCR conditions.

| Gene | Forward and reverse primer | Product length | Annealing temperature | MgCl2 Concentration | Accession ID (NCBI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adipogenic markers | |||||

| LPL | F: 5′-CTGCAAATGAGACACTTTCTC-3' R: 5′-CATGTCCTGGCAGTCTCTGA-3′ |

276 bp | 51 °C | 1.0 g/l | NM_000237 |

| PPARG | F: 5′-GCTGTTATGGGTGAAACTCTG-3' R: 5′-TAAGGTGGAGATGCAGGCTC-3′ |

350 bp | 51 °C | 1.0 g/l | NM_005037, NM_015869, NM_138711, NM_138712 |

| Osteogenic marker | |||||

| ALPL | F: 5′-TGGAGCTTCAGAAGCTCAACACCA-3' R: 5′-ATCTCGTTGTCTGAGTACCAGTCC-3′ |

454 bp | 51 °C | 1.0 g/l | NM_000478, NM_001127501, NM_001177520 |

| Chondrogenic markers | |||||

| ACAN | F: 5′-GCCTTGAGCAGTTCACCTTC-3' R: 5′-CTCTTCTACGGGGACAGCAG-3′ |

392 bp | 54 °C | 1.0 g/l | NM_001135, NM_013227 |

| BGN | F: 5′-AGTAGAGGCAGCTGCAGCCAC-3' R: 5′-GTGTCTGGACAGGTGCGGCAGC-3′ |

424 bp | 53 °C | 1.0 g/l | NM_001711 |

| COL2A1 | F: 5′-GGTATTGCTGGCTTCAAAGG-3' R: 5′-AGGACGACCATCTTCACCAG-3′ |

387 bp | 58 °C | 1.0 g/l | NM_001844, NM_033150 |

| COMP | F: 5′-CAGGACGACTTTGATGCAGA-3' R: 5′-AGGCTGGAGCTGTCCTGGTA-3′ |

312 bp | 54 °C | 1.0 g/l | NM_000095 |

| FMOD | F: 5′-ACCAGTGATAAGGTGGGCAG-3' R: 5′-AAGTAGCTATCGGGGACGGT-3′ |

368 bp | 54 °C | 1.0 g/l | NM_002023 |

| Hypertrophic marker | |||||

| COL10A1 | F: 5′-GGTATTGCTGGCTTCAAAGG-3' R: 5′-AGGACGACCATCTTCACCAG-3′ |

468 bp | 54 °C | 1.0 g/l | NM_000493 |

| Housekeeping gene | |||||

| EEF1A1 | F: 5′-AGGTGATTATCCTGAACCATCC-3' R: 5′-AAAGGTGGATAGTCTGAGAAGC-3′ |

235 bp | 54 °C | 1.0 g/l | NM_001402 |

Illustrated are the forward and reverse primers to amplify specific gene products along with their associated product lengths (lAmplicon), the annealing temperature (TAnneal), the concentrations of MgCl2 used in the reaction mixture (cMgCl), and the accession ID at the Gene database of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI).

Results

Cellular morphology and surface antigen expression

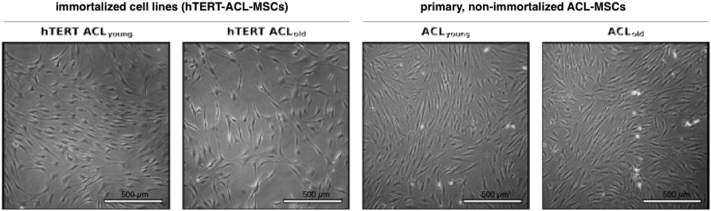

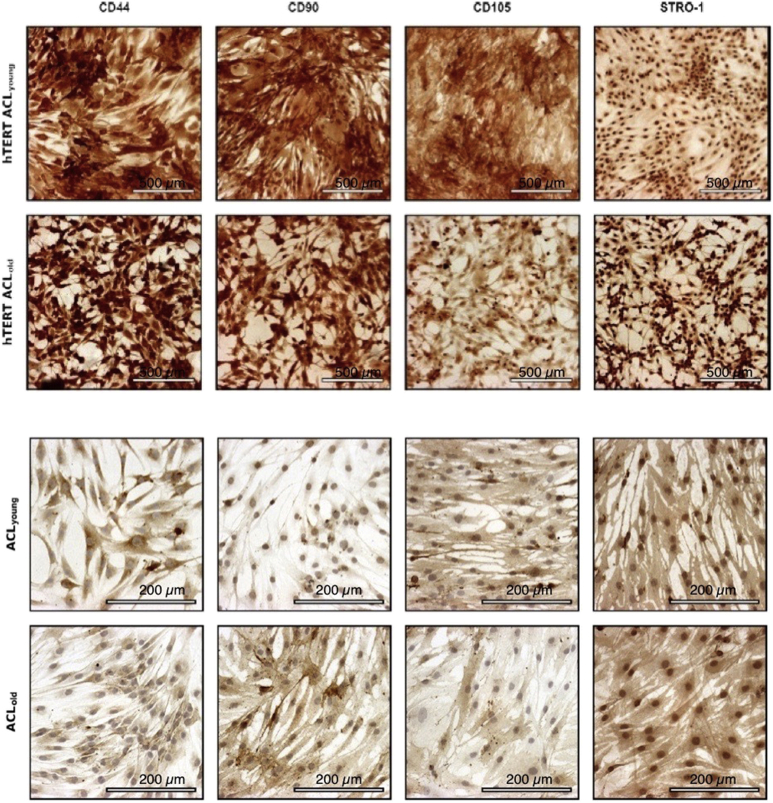

In monolayer culture, eighth passage hTERT-ACL-MSCs possessed a spindle-shaped morphology similar to non-passaged ACL-MSCs [Fig. 1]. A strong expression of the surface markers CD44, CD90, CD105, and STRO-1 was observed in hTERT-ACL-MSCs [Fig. 2].

Fig. 1.

Cellular morphology of hTERT-ACL-MSCs and non-immortalized ACL-MSCs. Phase contrast photo micrographs of the two immortalized cell lines (left panels) and the corresponding non-immortalized ACL-MSCs (right panels). No morphological differences were observed between the eighth passage hTERT-ACL-MSCs and the passage zero non-immortalized ACL-MSCs.

Fig. 2.

Immunophenotyping of hTERT-immortalized and non-immortalized primary ACL cells from young and old donors. A strong expression of the surface markers CD44, CD90, CD105, and STRO-1 was observed for immortalized cell-lines and non-immortalized primary ACL-MSCs of young and old donors. Bars indicating 200 μm (primary cells) or 500 μm (cell lines).

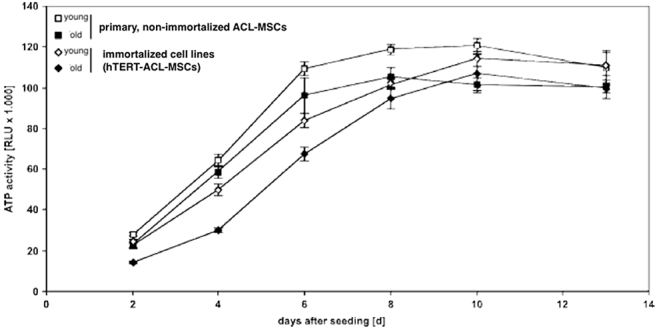

Proliferative capacity and cellular senescence

The short-term ATP activity assessed at day 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 13 within a single passage demonstrated the same pattern in hTERT-ACL-MSCs and ACL-MSCs. An increase in activity was observed in all groups until day 8. ACL-MSCs plateaued thereafter, while hTERT-MSCs demonstrated a slight increase in ATP activity until day 10. No substantial difference was observed between hTERT-ACL-MSCs and ACL-MSCs at all time points [Fig. 3]. Following long-term cultivation, ACL-MSCs demonstrated a high staining intensity for beta–galactosidase activity, indicating cellular senescence. In comparison, the staining intensity in hTERT-ACL-MSCs was reduced [Fig. 4].

Fig. 3.

Short-term proliferative capacity of hTERT-ACL-MSCs and non-immortalized ACL-MSCs. No substantial difference in the proliferative capacity was observed between hTERT-ACL-MSCs (diamonds) and the corresponding non-immortalized ACL-MSCs (squares).

Fig. 4.

β-galactosidase activity of hTERT-ACL-MSCs and non-immortalized ACL-MSCs after long-term culture. The staining intensity was reduced in hTERT-ACL-MSCs (left panels) when compared to non-immortalized ACL-MSCs (right panels), indicating a stronger senescent phenotype of the non-immortalized ACL-MSCs.

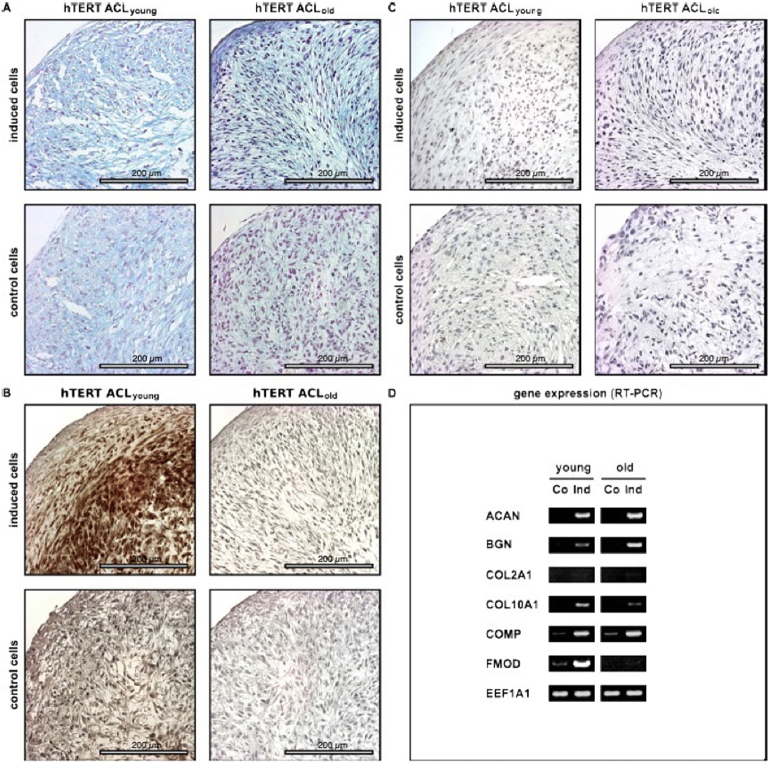

Chondrogenic differentiation

Cultivation of hTERT-ACL-MSCs as pellets in chondrogenic medium resulted in an upregulation of the proteoglycan encoding ACAN, BGN, and COMP, when compared to non-induced hTERT-ACL-MSC pellets. Fig. 5 shows the chondrogenic differentiation of the immortalized ACL fibroblasts. Chondrogenic differentiation was evaluated using alcian blue staining to visualize proteoglycans (A), hematoxylin and eosin staining to illustrate the cell nuclei (B), immunohistochemistry for the detection of COL2 (C) and by RT-PCR investigating chondrocyte-specific marker genes (D). hTERT ACLyoung fibroblasts are denoted as young and hTERT ACLold fibroblasts as old. Notably, FMOD expression was only induced in the cell line generated from the young donor [Fig. 5D]. Concomitantly, the alcian blue staining intensity was slightly increased in hTERT-ACL-MSCs after chondrogenic induction [Fig. 5A]. The type II collagen encoding COL2A1 was only slightly unregulated in hTERT-ACL-MSCs on the mRNA level, while a strong increase in type II collagen was detected on the protein level in the cell line generated from the young donor only. The COL10A1 expression was upregulated in hTERT-ACL-MSCs from both donors.

Fig. 5.

Potential for chondrogenic differentiation of immortalized hTERT-ACL-MSCs. After immortalization hTERT ACL cells of young (hTERT ACLyoung) and old (hTERT ACLold) donors were differentiated towards the chondrogenic lineage for 21 days. Chondrogenic differentiation (induced) was evaluated compared to controls (non-induced) using (A) staining for proteoglycans using alcian blue, (B) staining with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) to illustrate cell nuclei, and (C) immunohistochemistry for collagen (COL) 2 with bars indicating 200 μm. (D) Chondrogenic marker gene expression for the chondrogenic marker genes aggrecan (ACAN), biglycan (BCN), COL2 (COL2A1), COL10 (COL10A1), cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP), and fibromodulin (FMOD) was detected by RT-PCR analyses, with EEF1A1 serving as internal control. Co: Control; Ind: Induced.

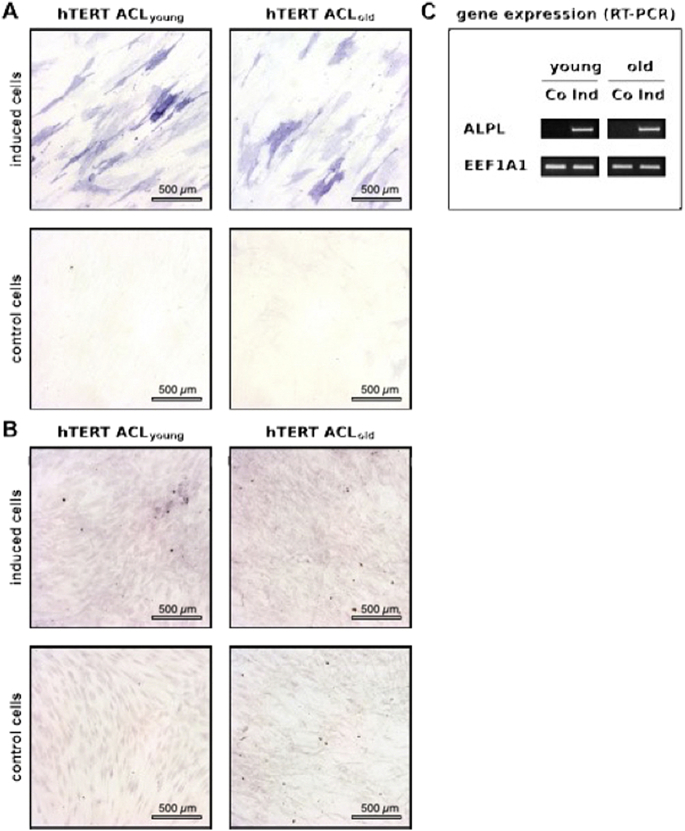

Osteogenic differentiation

Cultivation of hTERT-ACL-MSCs as monolayer in osteogenic medium resulted in an upregulation of ALPL gene expression [Fig. 6C], as well as a strong increase in staining for alkaline phosphatase activity [Fig. 6A]. Only a slight increase in alizarin red staining was observed at the assessed time point after induction in hTERT-ACL-MSCs [Fig. 6B].

Fig. 6.

Potential for osteogenic differentiation of immortalized hTERT-ACL-MSCs. hTERT immortalized ACL cells of young (hTERT ACLyoung) and old (hTERT ACLold) donors were differentiated towards the osteogenic lineage for 21 days. Osteogenic differentiation (induced) was evaluated compared to controls (non-induced) using staining for the osteogenic markers (A) alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and for mineralization using (B) alizarin red with bars indicating 500 μm. (C) Osteogenic marker gene expression for the ALPL gene was detected by RT-PCR analyses, with EEF1A1 serving as internal control. Abbreviations: Co: Control; Ind: Induced.

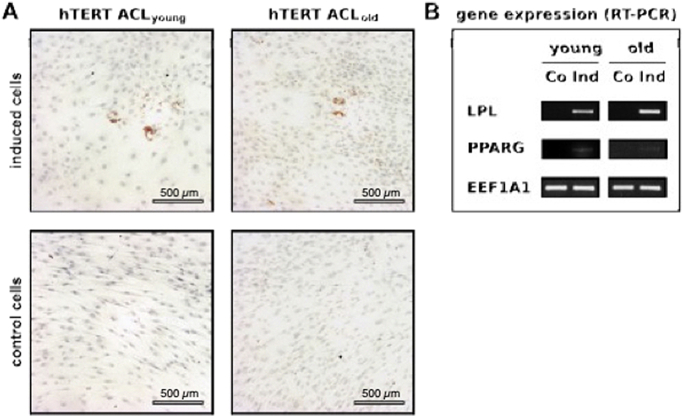

Adipogenic differentiation

Cultivation of hTERT-ACL-MSCs as monolayer in adipogenic medium resulted in strong upregulation of LPL and a slight upregulation of PPARG gene expression [Fig. 7B]. Concomitantly sporadic lipid vacuoles were observed in the induced hTERT-ACL-MSCs [Fig. 7A].

Fig. 7.

Potential for adipogenic differentiation of immortalized hTERT-ACL-MSCs. After immortalization and propagation, hTERT immortalized ACL cells of young (hTERT ACLyoung) and old (hTERT ACLold) donors were differentiated towards the adipogenic lineage for 21 days. (A) Adipogenesis after fat induction (induced) compared to controls (non-induced) was evaluated using oil red O staining for lipid droplets. Bars indicating 500 μm. (B) Adipogenic marker gene expression for LPL and PPAR was detected by RT-PCR analyses with EEF1A1 serving as internal control. Abbreviations: Co: Control; Ind: Induced.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to assess, whether cell lines that were generated from isolated ACL-MSCs using TERT gene transfer maintain the cellular morphology, surface antigen expression profile, and proliferative capacity of naive non-immortalized ACL-MSCs. Using two cell lines, one generated from a young donor (17 years) and one from an old donor (73 years), we did not observe morphological differences between the immortalized cell lines and the non-immortalized ACL-MSCs. The cell-lines maintained a strong expression of CD44, CD90, CD105, and STRO-1 surface markers, which are expressed on human MSCs, suggesting that the immortalized cell lines maintain their potential for multilineage differentiation as confirmed subsequently. No difference was observed in regards to the short-term proliferative capacity (the proliferative capacity within one passage) between the cell lines and the non-immortalized ACL-MSCs. After long-term culture the immortalized cell lines demonstrated a reduced beta–galactosidase activity, indicating reduced senescence in the cell lines, when compared to the non-immortalized ACL-MSCs.

Further, we have assessed whether the immortalized cell lines maintain their capacity for multilineage differentiation. Therefore, the two cell lines were cultured in chondrogenic, osteogenic, adipogenic media, or control media that were lacking the key differentiation factors. The immortalized cell lines maintained capable to differentiate along the chondrogenic, osteogenic, and adipogenic lineages. Specifically, the successful chondrogenic differentiation was demonstrated by increased glycosaminoglycan expression (increased alcian blue staining and ACAN, BGN, and COMP expression). Notably, an increased type II collagen expression on the protein level was only observed in the cell line generated from the young donor. Although not being the objective of this study, the finding might suggest age-specific differences in the capacity for chondrogenic differentiation. However, no statistical testing could be performed, since this study included one cell line per age group. The evaluation of this phenomenon requires future, adequately powered studies. The successful differentiation of the immortalized cell lines along the osteogenic and the adipogenic lineages were indicated by the increased alkaline phosphatase activity and in ALP expression, and the increased presence of oil red O stained lipid vacuoles and increased LPL and PPARG expression, respectively.

This study is the proof of concept that ACL-derived MSCs can be subjected to an immortalization procedure, specifically the lentiviral transfer of human TERT, to create a cell line that maintains the characteristics of the non-immortalized ACL-MSCs. Such model-systems can facilitate the development of new cell-based regenerative approaches, since they eliminate the need for frequent isolations of ACL-MSCs. Further, they eliminate intra-individual variations in the characteristics of the utilized mesenchymal stem cells throughout experiments and thus might reduce the number of needed biological replicates.

Although this experiment demonstrates that the creation of cell-lines from ACL-MSCs is feasible, it was not designed to test for subtle differences in the characteristics of immortalized cell lines and non-immortalized ACL-MSCs. However, towards the clinical application of cell-therapies that are based on ACL-MSCs, autologous non-immortalized ACL-MSCs would be used. Immortalized cell-lines are a tool to enhance the evaluation of the cell-characteristics and the development of new therapies.

Conclusions

Immortalized cell lines generated from anterior cruciate ligament derived mesenchymal stem cells maintain their morphology, surface antigen expression profile, and proliferative capacity, while markers of senescence appear to be reduced. These cell lines maintained their multilineage-differentiation-capacity. Comparing cell lines from a 17- and a 73-year-old donor, only the capacity for chondrogenic differentiation appeared to be decreased in the cell line generated from the older donor in regards to the expression of some of the assessed markers (type–II–collagen, FMOD). The demonstrated model-systems can be used for further development of new cell-based regenerative approaches in anterior cruciate ligament research, which may lead to new therapeutic strategies in the future.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was funded in part by a grant from the Bayerische Forschungsstiftung [FORZEBRA, TP2WP5]. It didn't influence the research presented in this article. This publication was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) and the University of Wuerzburg in the funding programme Open Access Publishing.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Viola Zehe and Martina Regensburger for their excellent technical assistance.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chang Gung University.

References

- 1.Daniel D.M., Stone M.L., Dobson B.E., Fithian D.C., Rossman D.J., Kaufman K.R. Fate of the ACL-injured patient. A prospective outcome study. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22:632–644. doi: 10.1177/036354659402200511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mihelic R., Jurdana H., Jotanovic Z., Madjarevic T., Tudor A. Long-term results of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a comparison with non-operative treatment with a follow-up of 17–20 years. Int Orthop. 2011;35:1093–1097. doi: 10.1007/s00264-011-1206-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lipscomb A.B., Johnston R.K., Snyder R.B. The technique of cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 1981;9:77–81. doi: 10.1177/036354658100900201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones K.G. Reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament: a technique using the central one-third of the patellar ligament. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1963;45:925–932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frobell R.B., Roos E.M., Roos H.P., Ranstam J., Lohmander L.S. A randomized trial of treatment for acute anterior cruciate ligament tears. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:331–342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frobell R.B., Roos H.P., Roos E.M., Roemer F.W., Ranstam J., Lohmander L.S. Treatment for acute anterior cruciate ligament tear: five year outcome of randomised trial. BMJ. 2013;346:232. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wen C., Lohmander L.S. Osteoarthritis: does post-injury ACL reconstruction prevent future OA? Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2014;10:577–578. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2014.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bi Y., Ehirchiou D., Kilts T.M., Inkson C.A., Embree M.C., Sonoyama W. Identification of tendon stem/progenitor cells and the role of the extracellular matrix in their niche. Nat Med. 2007;13:1219–1227. doi: 10.1038/nm1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nöth U., Osyczka A.M., Tuli R., Hickok N.J., Danielson K.G., Tuan R.S. Multilineage mesenchymal differentiation potential of human trabecular bone-derived cells. J Orthop Res. 2002;20:1060–1069. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(02)00018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang T.F., Chen Y.T., Yang T.H., Chen L.L., Chlou S.H., Tsai T.H. Isolation and characterization of mesenchymal stromal cells from human anterior cruciate ligament. Cytotherapy. 2008;10:806–814. doi: 10.1080/14653240802474323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friedenstein A.J., Gorskaja J.F., Kulagina N.N. Fibroblast precursors in normal and irradiated mouse hematopoietic organs. Exp Hematol. 1976;4:267–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steinert A.F., Kunz M., Prager P., Barthel T., Jakob F., Nöth U. Mesenchymal stem cell characteristics of human anterior cruciate ligament outgrowth cells. Tissue Eng Part A. 2011;17:1375–1388. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2010.0413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dominici M., Le Blanc K., Mueller I., Slaper-Cortenbach I., Marini F., Krause D. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2006;8:315–317. doi: 10.1080/14653240600855905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Böcker W., Yin Z., Drosse I., Haasters F., Rossmann O., Wierer M. Introducing a single-cell-derived human mesenchymal stem cell line expressing hTERT after lentiviral gene transfer. J Cell Mol Med. 2008;12:1347–1359. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00299.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Docheva D., Padula D., Popov C., Weishaupt P., Prägert M., Miosge N. Establishment of immortalized periodontal ligament progenitor cell line and its behavioural analysis on smooth and rough titanium surface. Eur Cell Mater. 2010;19:228–241. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v019a22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dimri G.P., Lee X., Basile G., Acosta M., Scott G., Roskelley C. A biomarker that identifies senescent human cells in culture and in aging skin in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9363–9367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kassem M., Ankersen L., Eriksen E.F., Clark B.F., Rattan S.I. Demonstration of cellular aging and senescence in serially passaged long-term cultures of human trabecular osteoblasts. Osteoporos Int. 1997;7:514–524. doi: 10.1007/BF02652556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pittenger M.F., Mackay A.M., Beck S.C., Jaiswal R.K., Douglas R., Mosca J.D. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science. 1999;284:143–147. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5411.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]