Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to assess the possible association between different factors such as age, sex, antibiotic consumption duration, angiogenesis and pain and “acceleration of wound healing” in pilonidal sinus patients after treating with platelet-rich plasma (PRP).

Methods

In this clinical trial, 110 patients were randomly divided into treatment arm and control group. After surgery, control group underwent classic wound dressing and the treatment arm experienced PRP gel therapy. Before achieving complete healing, wound incisional biopsy was performed in order to evaluate angiogenesis. During the study, other data such as pain and antibiotic consumption duration were also collected. Wound healing time of pilonidal sinus disease was analyzed using Extended and Stratify Cox model. Data were analyzed using R and STATA software. p<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

The average wound volume was calculated 41.9 ± 8.01 cc in the controls and 42.35 ± 10.81 in the treatment arm group. The mean of healing time was 8.7 ± 1.18, 4.8 ± 0.87 weeks for control and treatment arm, respectively. There was a significant and strong negative association between healing time and wound volume (p<0.01). Moreover, a significant negative association was found between pain duration and angiogenesis (p<0.001), a strong positive significant association was found between healing time of the treatment arms (p<0.01), and the rate of wound healing for participants treated with PRP gel was 37.2 times more than that of controls.

Conclusion

Authors hope for these finding to help the future researches to more thoroughly focus on the mentioned factors in order to find a suitable strategy for wound healing using PRP.

Keywords: Pilonidal sinus, Wound healing, Extended cox regression, Platelet-rich plasma

At a glance of commentary

Scientific background on the subject

The main treatment for the pilonidal sinus disease is surgery. In patients undergoing surgery with the secondary intention plane wound healing is an important issue that strongly affects the patients' quality of life as well as wound-related complications such as infection

What this study adds to the field

Previously, we have shown platelet-rich plasma (PRP) is an effective method to accelerate the healing in the mentioned patients. Herein, with more complex statistical analyses on the results, we showed that PRP therapy could increase the healing process 37.2 times. Also, the results showed angiogenesis as the key mechanism of treatment.

Pilonidal sinus disease (PSD), is a sinus or abscess locating in the midline natal cleft of the sacrococcygeal area with a 5–8 cm distance from anus [1]. This disease mostly occurs in an age range of 15–30 years with incidence of 26/100000. PSD has caused an average hospitalization duration of 4.3 days in 2000 and 2001 (in England). It develops 4 times more in men compared to women, however, people are rarely diagnosed with this disease after the age of 40 years old [2]. PSD was bolded in World War II since it caused hospitalization of about 78000 individuals for an average of five days in United State's army [3]. Although the exact etiology of PSD is still unknown, certain factors such as sedentary occupations, positive family history of PSD, local trauma, excessive hair growth in the region and white race have been proposed as potential risk factors [1]. The disease presentations could vary from asymptomatic to acute, chronic and recurrent. PSD could strongly affect patient's quality of life by causing discomfort, pain, and discharge. After surgery, some conditions such as pain and discomfort would hinder or trouble physical activity; all lead to lessened work hours [4], [5]. For the treatment of this disease, surgery has been introduced and performed through three main strategies as follow: 1) surgical excision 2) healing of overlying skin 3) prevention of recurrence [3]. Although all surgeons agree on these strategies, an issue will remain unsolved to whether leave the wound open or to close it after the surgery. According to the data, despite the faster healing time in primary closure, the recurrence risk is increased up to 58% in comparison to an open wound until complete healing which is also known as secondary intention [6], [7]. In a meta-analysis, it was shown that wounds with primary closure usually heal in week 2 whilst this period of time in secondary intention method is about 2 months [3].

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP), as it is perceived, consists of high amounts of platelets and also growth factors [8]. This autologous product is used in different fields of medicine as a common healing accelerator such as diabetic foot [9], [10], pilonidal sinus [11], maxillofacial surgeries [12], plastic surgeries [13], discogenic low back pain [14] and skin and soft tissue lesions [15]. Wound healing using PRP usually starts with α-granules degradation which leads to the production of different types of growth factors [15]. PRP is mostly composed of platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) [16], vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) and insulin-like growth factor (IGF) [8], [15]. Angiogenesis is the formation new micro-vessels from pre-existing ones and bolded in pathological conditions [17], [18], since wound healing [19] and female reproductive cycle [17] are the only processes in adulthood that depend on angiogenesis. VEGF is considered as one of the most critical angiogenic factors that is responsible for the production of other angiogenic factors such as matrix metalloproteinases [20], highly found in PRP [15].

The aim of this study was to evaluate the correlation between different factors in wound healing activity of PRP gel in patients suffering from pilonidal sinus and have undergone surgery.

Materials and methods

Ethical issues

All the methods of this trial were approved by Medical Ethics Committees of Hospital and University. Authors declare their adherence to 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and its next revisions. At the beginning of the trial, all the patients were asked to sign a written informed consent form containing all the aim and plan of study freely after being explained the aims of this trial. This trial was registered in Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (under the supervision of Ministry of Health and Medical Education) with the license number of IRCT2016020418842N11.

Study design and patient selection

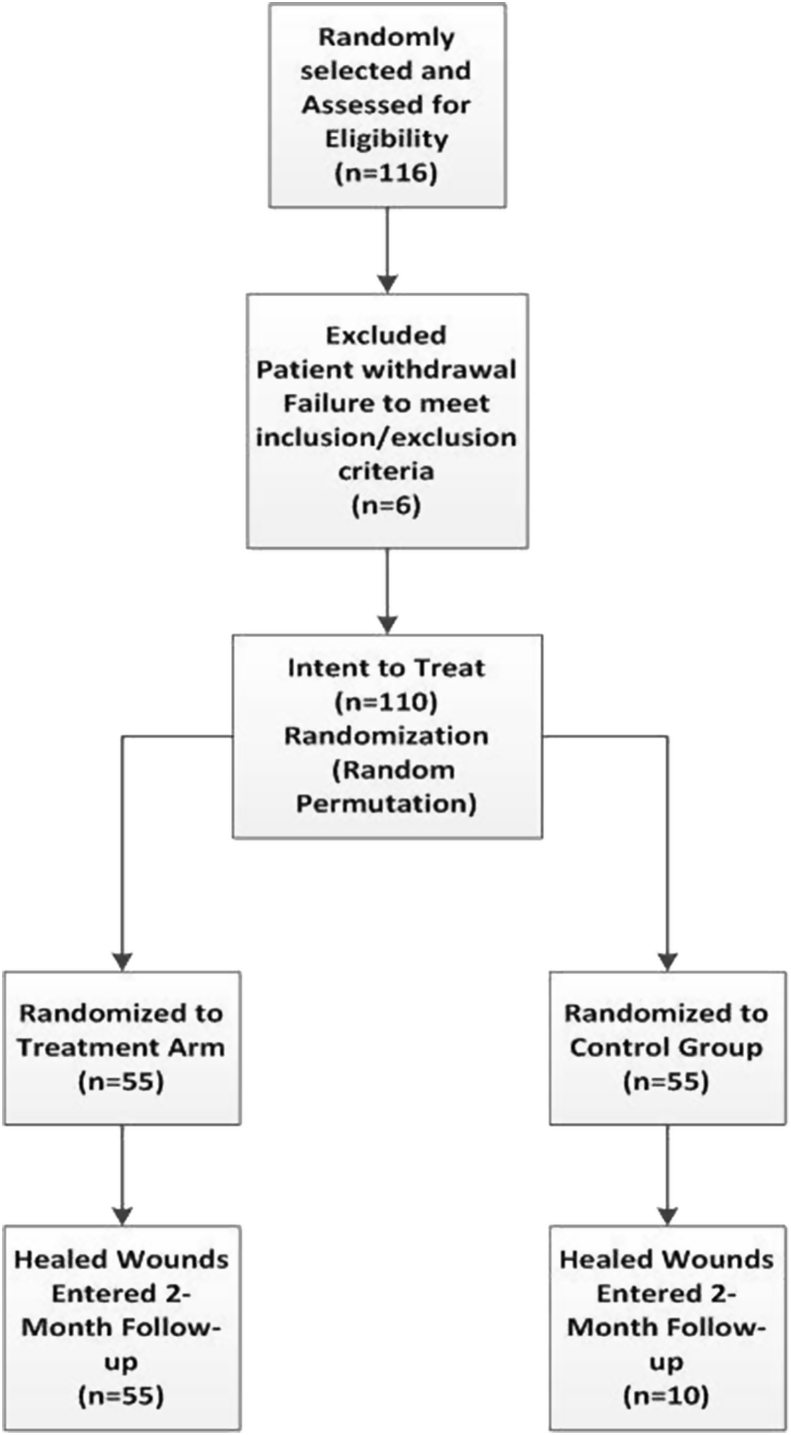

This randomized, controlled, parallel group clinical trial (Phase IV) was conducted between June 2012 and September 2015 in Shariati Hospital (Tehran, Iran). For inclusion criteria, diagnosed patients with PSD (patients with a history of abscess or discharge in the presacral area) were enrolled at the first step. Then, the following exclusion criteria were met: serum Hb < 10 mg/dL, platelet count<106/mL, history of radiation or anti-proliferative medication for past 3 months, any contra-indication for peripheral venous access, history of growth factor therapy within last 2 weeks, and history of diabetes. More details on trial profile were shown in [Fig. 1]. Among 116 potential patients selected and enrolled, 110 participants met the study's inclusion and exclusion criteria. The participants were then randomly (by randomly permuted blocks approach) divided into the two parallel groups of control and treatment arm, each including 55 patients. Participants were followed up until the healing was complete. However, the endpoint to our study was 9 weeks after beginning of the treatment.

Fig. 1.

The trial profile.

Surgery

Before surgery, the patients were explained the surgery and all the procedures. Then, they were asked to sign the consent form. Any individual with possible risk factor was referred to a cardiologist and/or anesthesiologist for pre-operation consultation. Before the surgery, a single dose of cefazolin was prescribed as prophylaxis and after prep and drape prone position was applied before general anesthesia. Using an elliptical incision (involving the sinus orifice) the sinus was resected until the presacral fascia borderline was achieved. All the surgeries in this trial were performed by an experienced surgeon (10 years of professional experience). After the surgery, the wounds were gently filled by normal saline using a 500 cc syringe and then wounds' volume was calculated with the scale of cc by redrainage.

Platelet-rich plasma gel

PRP preparation was performed using Rooyagen™ PRP-Gel kit (Arya Mabna Tashkhis Co, Iran). First, with a peripheral venous access, 27 mL blood was drawn by a syringe containing 3 mL sodium citrate as an anticoagulant agent. Then, the harvested blood was shaken gently 4 times. After that, the blood was transferred into three 10 mL tubes using the transfusion Kit adapter connected to the syringe. Each tube centrifuged at 2000×g for 10 min at 24 °C. After first centrifugation, the 2-fold rich platelet in the supernatant plasma was achieved. This PRP was then transferred to a second tube containing 2 mL 25 mM CaCl2 leading to gel formation after 20 min. In this method, the average count of platelets in PRP was 107/ml.

Wound dressing

Using an absorbent sterile cotton gauze, classic wound dressing was performed for the control group. In the treatment group, right after surgery, 0.1 cc/cm2 PRP was injected into the wound and repeated each week. In the next step, derived PRP was mixed with 0.9% CaCl2 in a ratio of 4/1 in order to make a gel before the dressing was carried out. Then using sterile non-allergenic latex, the surface was covered to prevent any leakage. After 24 h, the latex cover was removed and the classic dressing was performed. This process was repeated weekly at each visit.

Pain and antibiotic therapy duration

Regarding the patients' files, the duration of antibiotic consumption was recorded in the time intervals of 3 days, 6 days, 1 week and 2 weeks. Also, the patients were asked to declare the time of their ability to go back to daily routine activity. Moreover, the pain duration was inquired from participants as well.

Wound biopsy

In order to evaluate angiogenesis in both groups, wound biopsy was performed a few days (3–5 days) before complete healing by an incision. Angiogenesis was evaluated by immunohistochemistry assay of CD34+ (BD Pharmingen™, purified rat anti-CD34). All the steps performed by a well-experienced pathologist in a sterile situation.

Statistical methods

All data were summarized and demonstrated as frequency distribution (N (%)) for categorical variables or mean ± standard deviation (SD) for the continuous variables. The healing time of participants undergone sinus surgery was considered as the main outcome. We applied Extended and Stratify Cox regression since there was little censored data. The Log rank test was used for comparing wound healing time in two treatment groups. Data were analyzed using R software version 3.2.3 and STATA software versions 11.2 and with serial number of 71606281563. For deriving robust and accurate estimates of coefficients in the model, simple bootstrap resampling approach (suppress weighted regression) with 1000 Bootstrap samples was used. In all statistical analyses, power is more than 0.85 and any p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

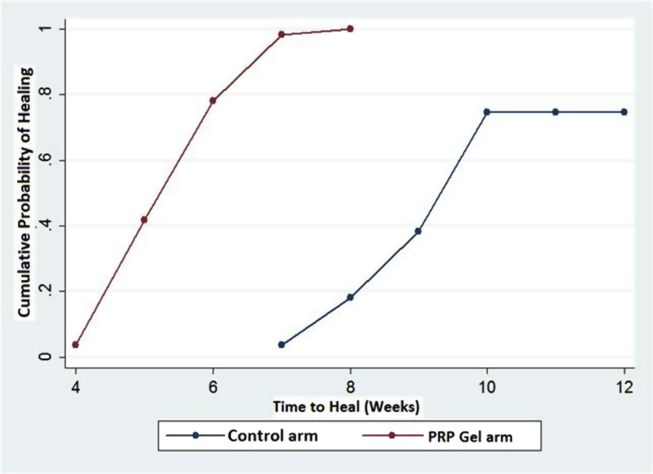

As previously described, the participants included 106 (96%) men with a mean (SD) age of 28.7 (6.14) years, ranging from 18 to 47 years. Participants were followed up until complete healing was achieved. No participant of either group left the trial during the study. The average age of the participants in the treatment arm group was calculated 29.8 ± 7.04 years, while this quantity for the control group was 27.5 ± 4.81 years. In the control group, 94.5% (N = 52) and 5.5% (N = 3) were male and female, respectively. Among the PRP gel treated group, these percentages were 98.2% (N = 54) and 2% (N = 1), respectively. The mean (SD) body mass index (BMI) was 24.9 (2.17) and 24.6 (2.19) for control and treatment group, respectively. The average volume of wounds was calculated 41.9 ± 8.01 cc in the control and 42.3 ± 10.81 in the treatment arm group. The mean (SD) of healing time was 8.7 (1.18), 4.8 (0.87) weeks for control and treatment arm, respectively [Fig. 2]. From 110 participants, 14 (12.7%) patient's healing times were right censored, since these subjects had a healing time of more than 9 weeks (9 weeks after the beginning of follow-ups which was considered the endpoint to healing time analysis). The mean (SD) of pain duration was 3.4 (0.59) and 1.3 (0.57) weeks for control and treatment arm, respectively. The mean (SD) of antibiotic consumption duration was 1.74 (0.44) and 0.57 (0.47) weeks for control and treatment arm, respectively. The mean (SD) of micro-vessels formation (angiogenesis) was 53 (12.35) and 68.3 (15.47) numbers for the control and treatment arm, respectively (more details are shown in [Table 1]) [21].

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier plot comparing wounds healing time between the control and treatment arms.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and comparison of general characteristics of study participants (Mean ± SD for continues variables and Number (%) for the categorical variable).

| Characteristics | Control Group (N = 55) | Treatment Group (N = 55) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agea | 27.5 ± 4.81 | 29.8 ± 7.04 | 0.051, t-test |

| 0.453, K–S test | |||

| Gender (male)+ | 94.5% (N = 52) | 98.2% (N = 54) | 0.313 |

| BMIa | 24.9 ± 2.17 | 24.6 ± 2.19 | 0.511 |

| Wound Volumea | 41.9 ± 8.01 | 42.3 ± 10.81 | 0.841 |

| Healing time (week)a | 8.7 ± 1.18 | 4.8 ± 0.87 | <0.001 |

| Pain duration(week)a | 3.4 ± 0.59 | 1.3 ± 0.57 | <0.001 |

| Antibiotic consumption Duration (week)a | 1.74 ± 0.44 | 0.57 ± 0.45 | <0.001 |

| Angiogenesis (Count)a | 53 ± 12.35 | 68.3 ± 15.47 | <0.001 |

Indicated as Mean ± SD, + indicated as N (%).

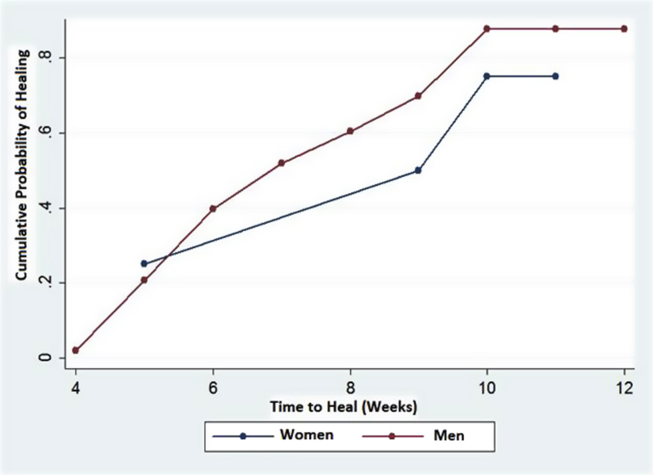

Survival distributions (time passed to achieve healing) between the control and treatment arm were significantly different until the end of the 9th week after beginning the follow ups (Log rank test = 113.53, p < 0.001). So, treatment by PRP gel exerted better effects on time of wound healing compared to control group [Fig. 3]. The Log rank test for comparing survival distributions between the women and men participants showed a significant difference until the end of the 9th week after beginning of follow ups (LR statistic = 77.5, p<0.001). According to [Fig. 4] male participants in each point of study were more prone to healing compared to female participants. The correlations between age and BMI with wound healing time were not statistically significant (ρ = −0.16, p = 0.09 for age) (ρ = 0.08, p = 0.38 for BMI) [Fig. 5].

Fig. 3.

Kaplan–Meier plot comparing wounds healing time between the women and men participants.

Fig. 4.

Observed versus Expected (under the model fitted) values of (1- healing probability).

Fig. 5.

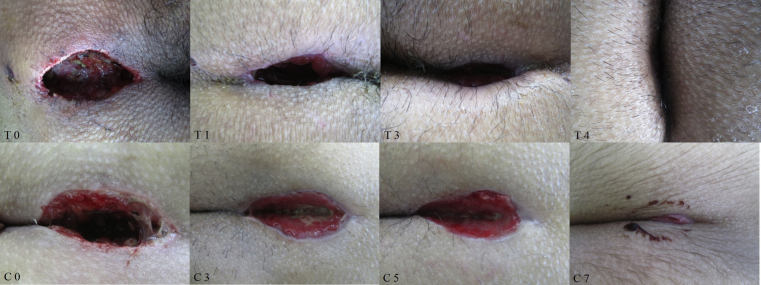

The process of wound healing in each group (time to heal). T is the patient in treatment arm and C is for the patient in control group. Each number indicates as the week(s) passed after the surgery and 0 is for post-surgery.

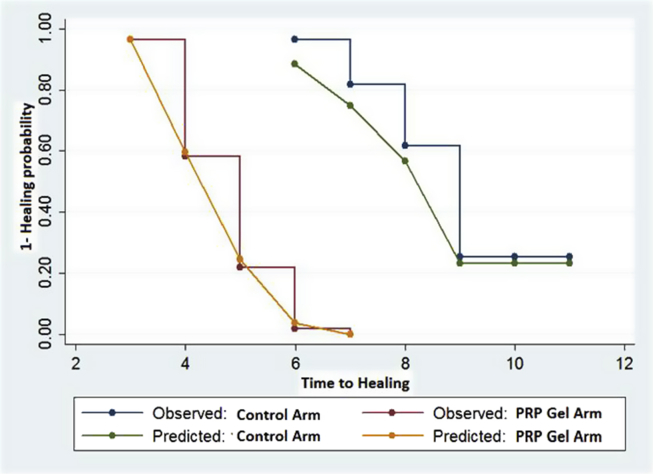

The proportional hazard assumption, as a critical assumption for Cox regression model, was checked for each covariate on the model by graphical approaches and time-dependent variable. Finally, this assumption for pain duration, duration of antibiotic consumption, angiogenesis and sex cannot be met. So, pain duration, duration of antibiotic consumption, and angiogenesis included in the model as time-dependent variables and sex were adjusted [Fig. 6].

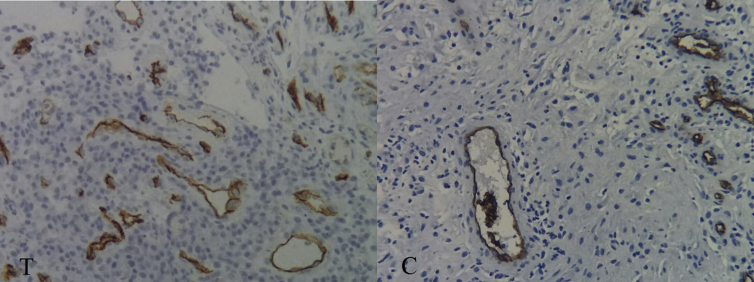

Fig. 6.

The results of CD 34 evaluation in biopsy samples in each group. T is the patient in treatment arm and C is for the patient in control group. The lumens were considered as vessels/micro-vessels.

According to the results of extended and stratify cox model, estimates of regression coefficients (β), SEs of the estimates and 95% confidence intervals were obtained and shown in the [Table 2, Table 3]. According to these tables, the sign and magnitude of regression coefficients, there was a significant and strong negative association between healing time and wound volume when comparing participants with wound volumes>42 cc to participants with wound volume<42 cc as the risk of wound healing ( [was decreased in the former group (Moreover, a significant negative association was found between pain duration and angiogenesis (p < 0.001)]. Although the association of healing time and pain duration was strongly negative, it wasn't significant. Furthermore, a strong positive significant association was found between wound healing time and treatment groups (PRP gel vs. control) (). In addition, the associations between wound healing time and the duration of antibiotic consumption, angiogenesis and age were positive but not significant. More details are shown in [Table 2].

Table 2.

Results of participants' characteristics on wound healing time based on 11-week follow up using Extended and Stratify Cox model for fixed time Characteristics.

| Fixed time Characteristics | Category | Coefficient (β) | p-value | SE | [95%CI] | Hazard Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain duration (week) | – | −1.04 | 0.42 | 1.29 | [−3.58; 1.50] | 0.353 |

| Duration of antibiotic consumption (week) | – | 7.39 | 0.097 | 4.45 | [−1.33; 16.11] | >100 |

| Angiogenesis | – | 0.078 | 0.094 | 0.04 | [−0.14; 0.17] | 1.081 |

| Treatment | Control | Reference | ||||

| PRP Gel | 3.611 | <0.001 | 0.81 | [2.01; 5.20] | 37.02 | |

| Age | <29 | Reference | ||||

| >29 | 0.059 | 0.83 | 0.27 | [−0.48; 0.59] | 1.06 | |

| Wound Volume | <42 cc | Reference | ||||

| >42 cc | −0.86 | 0.017 | 0.36 | [−1.55; −0.15] | 0.423 |

Table 3.

Results of participants' characteristics on wound healing time based on 11-week follow up using Extended and Stratify (on Gender) Cox model for Time Dependent Characteristics.

| Time Dependent Characteristics | Coefficient (β) | SE | p-value | [95%CI] | Hazard Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain duration (week) | 0.22 | 0.23 | 0.34 | [−0.24; 0.68] | 1.246 |

| Duration of antibiotic consumption (week) | −1.11 | 0.71 | 0.12 | [−2.51; 0.29] | 0.329 |

| Angiogenesis | 0.015 | 0.009 | 0.097 | [−0.003; 0.033] | 1.015 |

According to [Table 3], sign and magnitude of regression coefficients, over time of the study, weak negative associations were found between healing time and duration of antibiotic consumption. Furthermore, there was a positive association found between healing time and pain duration and angiogenesis.

Ultimately, Goodness-of-Fit (GOF) Statistic for this model was 119.64 (Log likelihood = −221.84, DF = 9, p<0.001). So, the model has enough goodness of fit. Also, Graphical approach supports the goodness of fit of the model for each treatment arms [Fig. 4].

Discussion

PSD associates with pain and discomfort which may even last after the surgery for a noticeable period of time. As mentioned before, the age interval of 15–30 years is most associated with the occurrence of PSD [2]. Considering this range and also the clinical features, this condition causes the waste of working days in active young population as well as being a burden to health care system's resources. In a study conducted between 2000 and 2001 in United Kingdome, 11000 patients were evaluated to find out that they have been hospitalized for the average of 3–4 days with a mean cost of 2400 £ [6].

In this trial, it was showed that PRP gel therapy was more successful in acceleration of wound healing in comparison to classic dressing [Fig. 5]. As presented in results, the associations between healing time and the duration of antibiotic consumption and age were positive. Also, a strong positive relation was found between the healing time and angiogenesis (by total vessels count [Fig 6 and Table 2]). Blood vessels are essential for supporting the oxygen and nutritional needs and also for removal of waste materials [22], [23], [24]. When a tissue is in a proliferating state (wound healing), nutritional needs will be increased [25], thus the tissue induces angiogenesis of new blood vessels to meet its required needs [26]. It seems that as time passes, total vessel counts (angiogenesis) are increased in order to support the wound healing process (as our data supported). As mentioned before, VEGF level is fairly high in PRP and this growth factor is suggested to be a main triggering and leading factor in angiogenesis [20] and wound healing [27]. Considering the already discussed positive correlation and also the significant difference of angiogenesis observed between control and treatment arm groups [Table 1], angiogenesis could be considered as one of the pathways of wound healing by PRP therapy. Also as declared, age and healing time have a positive correlation which means upon increasing the age, the wound healing time interval increases. This means a negative correlation exists between acceleration of wound healing and age. Although most data declare that in the age of more than 65 years [28] wound healing is impaired. The present study with the cutoff point of years, showed that getting older could negatively affect wound healing.

As it was mentioned, the correlation between different variables with wound volume was evaluated. In our calculations, the cutoff of 42 cc was considered as the mean volume of both control and treatment groups for further assessments. It was showed that there was a significant correlation between healing time and wound volume. According to the results, due to the <1 of calculated HR (0.423) and negative coefficient (β) of −0.86 in the group of ≥42 cc of wound volume it was showed that wounds with higher volume of 42 cc have a slower time of healing in comparison to the <42 cc wound volume. It is important to keep in mind that hazard ratio in this study means as the healing. According to the data, it was shown that wound healing was faster in patients with less pain duration. It could also be concluded that patients with faster wound healing suffered less due to the accelerated healing process. It has been proved that skin damage, blood vessel injury, infection, and ischemia are mainly responsible for pain in the wound site. All these factors also negatively influence wound healing [29]. Interestingly, ischemia which is a cause of pain could be decreased in a good perfusion state as a result of proper vascular culture caused by angiogenesis [30]. Considering the negative correlation between pain duration and angiogenesis it could be hypothesized that by inducing angiogenesis (that leads to an improved tissue perfusion) the ischemic state could be suppressed and eventually the pain would vanish. Also, as it is shown in [Table 1], duration of pain is significantly lower in treatment arm compared to the control group, affirming the capability of PRP gel therapy to also decrease the pain duration. In these cases, antibiotics are mostly prescribed as prophylaxis and when the wound reaches an acceptable ratio of healing, antibiotics are discontinued. As it was expected, antibiotic had a positive correlation with wound healing time and in some cases, antibiotic consumption duration was shortened as healing was accelerated. Also, as mentioned in the results, compared to controls the treatment arm had a significantly shorter antibiotic consumption period in comparison to controls, probably due to the accelerated healing time.

So far, several trials have been conducted on the effect of PRP therapy on PSD among which none has performed such statistical analysis carried out in this study [11], [31], [32], [33]. Moreover, among these studies, only the present trial evaluated the angiogenesis in PRP treated patients for the first time. Although other correlations such as age, pain and antibiotic consumption duration (which their data was presented herein) with time of healing were not evaluated in their studies. Therefore, it seems that the current study is the most inclusive among the mentioned studies since we evaluated all the preceding factors through different statistical analysis methods to investigate all the possible affecting/influencing factors. However, further complementary studies on the molecular aspects may provide us with more information on how to improve treatment method.

Conclusion

In this study, except for evaluating the efficacy of PRP on acceleration of wound healing, correlation of other factors with this issue was assessed. According to the results, it was shown that patients underwent PRP therapy experienced faster healing process as well as less pain and antibiotic consumption period. Moreover, it was hypothesized that angiogenesis is an important role player in both healing process and pain duration. Taken to gather, it seems that for those patients underwent pilonidal sinus surgery with secondary intention healing, PRP therapy seems to be a proper treatment option for reducing healing time, antibiotic consumption, and pain duration. However, complementary studies are necessary.

Conflicts of interest

Authors deny any actual or potential conflicts of interest related to this study.

Funding

This study was funded by Tehran University of Medical Sciences with grand number of 2820-91. No other financial disclosure to declare.

Acknowledgment

Authors deeply acknowledge all patients contribution who contributed in this trial.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chang Gung University.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bj.2019.05.002.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Farrell D., Murphy S. Negative pressure wound therapy for recurrent pilonidal disease: a review of the literature. J Wound, Ostomy Cont Nurs. 2011;38:373–378. doi: 10.1097/WON.0b013e31821e5117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harris C.L., Laforet K., Sibbald R.G., Bishop R. Twelve common mistakes in pilonidal sinus care. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2012;25:324–332. doi: 10.1097/01.ASW.0000416004.70465.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loganathan A., Zadeh R.A., Hartley J. Pilonidal disease: time to reevaluate a common pain in the rear. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:491–493. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31823fe06c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hull T.L., Wu J. Pilonidal disease. Surg Clin. 2002;82:1169–1185. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(02)00062-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Humphries A.E., Duncan J.E. Evaluation and management of pilonidal disease. Surg Clin. 2010;90:113–124. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCallum I.J., King P.M., Bruce J. Healing by primary closure versus open healing after surgery for pilonidal sinus: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2008;336:868–871. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39517.808160.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Khamis A., McCallum I., King P.M., Bruce J. Healing by primary versus secondary intention after surgical treatment for pilonidal sinus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;1:CD006213. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006213.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kabiri A., Esfandiari E., Esmaeili A., Hashemibeni B., Pourazar A., Mardani M. Platelet-rich plasma application in chondrogenesis. Adv Biomed Res. 2014;3:138. doi: 10.4103/2277-9175.135156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sakata J., Sasaki S., Handa K., Uchino T., Sasaki T., Higashita R. A retrospective, longitudinal study to evaluate healing lower extremity wounds in patients with diabetes mellitus and ischemia using standard protocols of care and platelet-rich plasma gel in a Japanese wound care program. Ostomy/Wound Manag. 2012;58:36–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mohammadi M.H., Molavi B., Mohammadi S., Nikbakht M., Mohammadi A.M., Mostafaei S. Evaluation of wound healing in diabetic foot ulcer using platelet-rich plasma gel: a single-arm clinical trial. Transfus Apher Sci. 2017;56:160–164. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2016.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spyridakis M., Christodoulidis G., Chatzitheofilou C., Symeonidis D., Tepetes K. The role of the platelet-rich plasma in accelerating the wound-healing process and recovery in patients being operated for pilonidal sinus disease: preliminary results. World J Surg. 2009;33:1764–1769. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0046-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Albanese A., Licata M.E., Polizzi B., Campisi G. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) in dental and oral surgery: from the wound healing to bone regeneration. Immun Ageing. 2013;10:23. doi: 10.1186/1742-4933-10-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sommeling C., Heyneman A., Hoeksema H., Verbelen J., Stillaert F.B., Monstrey S. The use of platelet-rich plasma in plastic surgery: a systematic review. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2013;66:301–311. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2012.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Monfett M., Harrison J., Boachie-Adjei K., Lutz G. Intradiscal platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injections for discogenic low back pain: an update. Int Orthop. 2016;40:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s00264-016-3178-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lacci K.M., Dardik A. Platelet-rich plasma: support for its use in wound healing. Yale J Biol Med. 2010;83:1–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Casati L., Celotti F., Negri-Cesi P., Sacchi M.C., Castano P., Colciago A. Platelet derived growth factor (PDGF) contained in Platelet Rich Plasma (PRP) stimulates migration of osteoblasts by reorganizing actin cytoskeleton. Cell Adhes Migrat. 2014;8:595–602. doi: 10.4161/19336918.2014.972785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Norooznezhad A.H., Norooznezhad F., Ahmadi K. Next target of tranilast: inhibition of corneal neovascularization. Med Hypotheses. 2014;82:700–702. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2014.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keshavarz M., Norooznezhad A.H., Mansouri K., Mostafaie A. Cannabinoid (JWH-133) therapy could be effective for treatment of corneal neovascularization. J Med Hypotheses Ideas. 2010;4:3. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson K.E., Wilgus T.A. Vascular endothelial growth factor and angiogenesis in the regulation of cutaneous wound repair. Adv Wound Care. 2014;3:647–661. doi: 10.1089/wound.2013.0517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Norooznezhad A.H., Norooznezhad F. How could cannabinoids be effective in multiple evanescent white dot syndrome? A hypothesis. J Res Pharm Sci. 2016;5:49–52. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mohammadi S., Nasiri S., Mohammadi M.H., Malek Mohammadi A., Nikbakht M., Zahed Panah M. Evaluation of platelet-rich plasma gel potential in acceleration of wound healing duration in patients underwent pilonidal sinus surgery: a randomized controlled parallel clinical trial. Transfus Apher Sci. 2017;56:226–232. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2016.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vermolen F., Javierre E. A finite-element model for healing of cutaneous wounds combining contraction, angiogenesis and closure. J Math Biol. 2012;65:967–996. doi: 10.1007/s00285-011-0487-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mostafaie A., Mansouri K., Norooznezhad A.H., Mohammadi Motlagh H.R. Anti-angiogenic activity of Ficus carica latex extract on human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Cell J. 2011;12:525–528. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Norooznezhad A.H., Norooznezhad F. Cannabinoids: possible agents for treatment of psoriasis via suppression of angiogenesis and inflammation. Med Hypotheses. 2017;99:15–18. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2016.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Valero C., Javierre E., García-Aznar J., Gómez-Benito M.J. Numerical modelling of the angiogenesis process in wound contraction. Biomechanics Model Mechanobiol. 2013;12:349–360. doi: 10.1007/s10237-012-0403-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Janis J.E., Harrison B. Wound healing: part I. Basic science. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;133:199e–207e. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000437224.02985.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilgus T.A., DiPietro L.A. Complex roles for VEGF in dermal wound healing. J Investig Dermatol. 2012;132:493–494. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sgonc R., Gruber J. Age-related aspects of cutaneous wound healing: a mini-review. Gerontology. 2012;59:159–164. doi: 10.1159/000342344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guo S., DiPietro L.A. Factors affecting wound healing. J Dent Res. 2010;89:219–229. doi: 10.1177/0022034509359125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ouma G.O., Zafrir B., Mohler E.R., Flugelman M.Y. Therapeutic angiogenesis in critical limb ischemia. Angiology. 2013;64:466–480. doi: 10.1177/0003319712464514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bahar M.M., Akbarian M.A., Azadmand A. Investigating the effect of autologous platelet-rich plasma on pain in patients with pilonidal abscess treated with surgical removal of extensive tissue. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2013;15:e6301. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.6301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karahan Ö., Sevinç B., Şimşek G., Demirgül Recep. Minimally invasive treatment of pilonidal sinus disease using platelet-rich plasma. Transl Surg. 2016;1:14–17. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mostafaei S., Norooznezhad F., Mohammadi S., Norooznezhad A.H. Effectiveness of platelet-rich plasma therapy in wound healing of pilonidal sinus surgery: a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. Wound Repair Regen. 2017;25:1002–1007. doi: 10.1111/wrr.12597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.