Abstract

Introduction

Identifying target oncogenic alterations in lung cancer represents a major development in disease management. We examined the association of fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1) gene amplification with pathological characteristics and geographic region.

Material and methods

We conducted a meta-analysis of studies published between January 2010 and October 2016. Relative risks (RR) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated regarding the rate of FGFR1 amplification in different lung cancer types and geographic region.

Results

Twenty-three studies (5252 patients) were included. There was heterogeneity between studies. However, in subgroup analyses for squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), small cell lung cancer (SCLC), studies using the same definition of FGFR1 amplification, and those from Australia, no significant heterogeneity was detected. The prevalence of FGFR1 amplification in these studies ranged from 4.9% to 49.2% in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), 5.1% to 41.5% in SCC, 0% to 14.7% in adenocarcinoma, and 0% to 7.8% in SCLC. The prevalence of FGFR1 amplification was significantly higher in SCC than in adenocarcinoma (RR = 5.2) and SCLC (RR = 4.2). The prevalence of FGFR1 amplification ranged from 5.6% to 22.2% in Europe, 4.1% to 18.2% in the United States, 7.8% to 49.2% in Asia, and 14.2% to 18.6% in Australia. The rate of FGFR1 amplification was higher in Asians than in non-Asians (RR = 1.9) in NSCLC.

Conclusions

These results suggest that FGFR1 amplification occurs more frequently in SCC and in Asians. FGFR1 amplification may be a potential new therapeutic target for specific patients and lung cancer subtypes.

Keywords: fibroblast growth factor receptor 1, gene amplification, lung cancer

Introduction

Lung cancer is the most common cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide [1]. Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for 75% of all lung cancers and has two predominant subtypes, adenocarcinoma (ADC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), which constitute 40% and 25% of NSCLC cases, respectively [2, 3]. Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) is a well-recognized histologic variant of lung cancer with a distinct histologic appearance and unique biology. SCLC accounts for approximately 16–18% of all newly diagnosed lung cancers in the United States, which translates into approximately 30,000 new cases annually [4–6]. Because of the lack of specific symptoms, most cases of lung cancer are diagnosed in the middle or late stages. Methods that may improve earlier detection include positron emission tomography, autofluorescence bronchoscopy, and molecular biomarkers [7]. Although diagnostic strategies, treatment techniques, and surgical approaches for lung cancer management have improved significantly in recent years, most patients with lung cancer still have a poor prognosis, with a 5-year survival rate of approximately 15% [8]. In comparison with NSCLC, SCLC features a shorter doubling time, higher growth fraction, and earlier development of widespread metastases [4–6]. The ability to identify target oncogenic alterations in lung cancer has been a major improvement in disease management. To translate knowledge of these molecular alterations into clinical practice, it is important to develop assays that can quickly and reliably identify specific aberrations in clinical specimens. Thus, identifying factors that contribute to lung cancer prognosis is highly relevant for optimizing treatments and improving the prognosis of patients.

Fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1) is an emerging molecular target for the treatment of SCC of the lung [9–11], and several clinical trials of FGFR inhibitors in NSCLC are currently underway [12–14]. Amplification of the FGFR gene has been found in epithelial malignancies, such as gastric, breast, oral squamous cell, ovarian, and bladder carcinomas [15, 16], and more recently, in lung SCC. The FGFR1 gene is amplified in lung cancer at varying frequencies and has been shown to be a driving oncogenic factor in lung cancer [17–20]. Thus, FGFR is a promising and novel therapeutic target for the treatment of these tumors.

Previous studies of FGFR1 amplification in lung cancer have focused on SCC [21, 22], several of which have investigated the relationship between FGFR1 amplification and clinical characteristics such as smoking status, disease stage, and sex; however, findings have been inconsistent across studies and meta-analyses [19, 22]. Additionally, published reviews lack data for Chinese patients. To perform an updated comprehensive quantitative evaluation of the relationship between FGFR1 amplification and the clinical characteristics of lung cancer, we conducted an updated meta-analysis of the published literature in this area. This study summarizes the current knowledge on FGFR1 amplification in the main subtypes of lung cancer and comprehensively reports the relationship between FGFR1 gene amplification and the clinicopathological characteristics of lung cancer.

Material and methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, Web of Science, and CNKI for articles published in English or Chinese between January 1991 and October 2016. The following search terms were used alone or in combination: Lung Neoplasms OR Pulmonary Neoplasms OR Lung Cancer OR Cancer, Lung OR Pulmonary Cancer OR Cancer, Pulmonary OR Cancer of Lung AND Receptor, Fibroblast Growth Factor, Type 1 OR Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor 1 OR FGFR1 Protein.

The eligibility of all studies was evaluated and determined by two authors (JM and RL), who scored each study independently. Inclusion criteria were (1) FGFR1 amplification was measured in lung cancer; (2) when the same group of patients was included in more than one article, the most recent or the most informative report was utilized; (3) only articles published as full-text papers in English or Chinese were included; and (4) test methods included reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH), or silver in situ hybridization (SISH). Exclusion criteria were (1) reviews or case-only studies, (2) studies lacking sufficient data for pooling analysis, and (3) duplication of previous publications or replicated samples.

Data extraction and methodological assessment

The following clinical characteristics for patients and other study data were extracted from each study: surname of the first author, year of publication, patient geographic region, histology, FGFR1 gene copy number, test method, the definition of FGFR1 amplification, and number of cases and controls. The two reviewers assessed study quality independently using the following factors: (1) a clear definition of the study population and the type of carcinoma, (2) a clear definition of the measurement method and the cut-off value of FGFR1 gene amplification, (3) sample size larger than 10, and (4) a clear definition of the outcome assessment (if applicable). Studies lacking any of these elements were excluded from the final analysis.

The two reviewers independently read and scored each study according to the NEWCASTLE-OTTAWA scale [23]. The quality score was assessed according to three main categories: (1) patient selection, (2) comparability between the case and control groups, and (3) exposure assessment method. The maximum score was 9 points, and a high-quality study in our analysis was defined as a study with ≥ 7 points (7.42 ±0.98). Any disagreement was resolved by consensus.

Statistical analysis

The statistical heterogeneity was estimated with Cochran’s Q (reported as χ2 and p-values) and the I 2 statistic, which indicates the percentage of variation between studies that is due to heterogeneity rather than chance. Unlike Q, I 2 does not inherently depend on the number of studies included; values of 25%, 50%, and 75% indicate low, moderate, and high degrees of heterogeneity, respectively. If the heterogeneity was high (p < 0.1) [24], a random-effects model was used; otherwise, a fixed-effects model was used [25]. Subgroup analyses were performed to explore heterogeneity. Sensitivity analyses were performed to assess the stability of the results, and Begg’s funnel plots were used to assess publication bias [26]. All p-values were two-sided, with p < 0.05 considered statistically significant, except in the Q-test. Results are reported in a forest plot, with 95% CI. Statistical analyses were conducted using STATA version 11.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). In addition, relative risks (RRs) were estimated for the rate of FGFR1 amplification in different types of lung cancer and different geographic regions using χ2 tests. The mean and 95% CI were estimated using SPSS Statistics 17.0.

Results

Selection of studies and trial flow

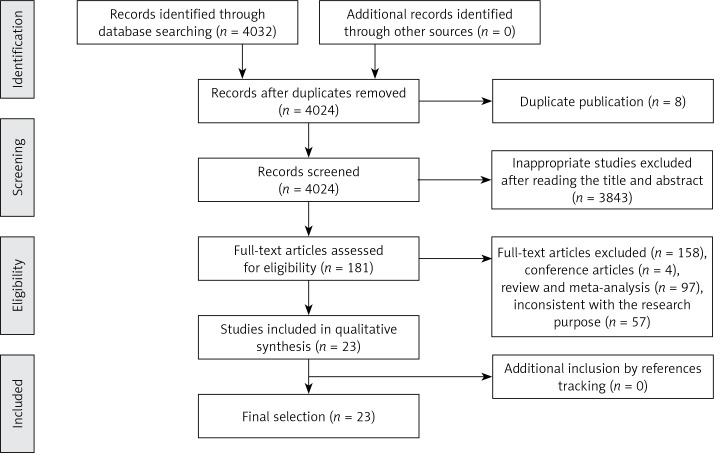

Figure 1 shows the results of the literature search. A total of 4032 potentially relevant abstracts were identified, and 3940 inappropriate studies were removed after reading the title and abstract. Eight were found to be duplicates and were excluded. Another four conference articles were excluded. Fifty-seven studies were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria, including 55 reviews and two meta-analyses. Twenty-three studies met the eligibility criteria and were included in this systematic review.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of search results

Study characteristics

In total, 5252 patients participated in the 23 studies included in this analysis. Six studies were conducted in Asia, eight in Europe, seven in the United States, and two in Australia. The gene copy number for FGFR1 was evaluated using FISH in 16 studies [10, 11, 18, 21, 27–38], RT-PCR in three studies [39–41], SISH in two studies [42, 43], single-nucleotide polymorphism in one study [9], and DNA in one study [44]. Based on data shown in Tables I and II, we concluded that the prevalence of FGFR1 amplification in these studies ranged from 4.9% to 49.2% in NSCLC, 5.1% to 41.5% in SCC (mean = 19.8%, 95% CI: 15.8–23.8), 0% to 14.7% in ADC (mean = 5.4%, 95% CI: 1.7–9.1), and 0% (0/9) [42] to 7.8% in SCLC (mean = 6.1%, 95% CI: 4.3–8.0). The prevalence of FGFR1 amplification in lung cancer ranged from 5.6% to 22.2% in Europe [10, 18, 21, 27, 31, 34, 35, 37] (mean = 12.4%, 95% CI: 8.5–16.3), 4.1% to 18.2% in the United States [9, 11, 29, 30, 36, 39, 44] (mean = 12.5%, 95% CI: 5.6–19.4), 7.8% to 49.2% in Asia [28, 32, 38, 40, 41, 43] (mean = 21.1%, 95% CI: 8.7–33.5), and 14.2% to 18.6% in Australia [33, 42] (mean = 12.5%, 95% CI: 6.7–18.4). The main characteristics of the included studies are shown in Tables I and II.

Table I.

Clinical characteristics of the studies

| Author | Year | Race | NP | FGFR1+, n (%) | Histology | Method | Cut-off |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sousa [10] | 2016 | Portugal | 76 | 15 (19.7) | NSCLC | FISH | FGFR1/CEN8 ratio ≥ 2.0 |

| Cihoric [31] | 2014 | Switzerland | 329 | 41 (12.5) | NSCLC | FISH | FGFR1/CEP8 ratio ≥ 2.0 |

| Toschi [11] | 2014 | United States | 445 | 74 (16.6) | NSCLC | FISH | ≥ 4 gene copies/cell |

| Seo [32] | 2014 | Korea | 369 | 32 (8.7) | NSCLC | FISH | Gene copy number ≥ 6.2 |

| Russell [33] | 2014 | Australia | 352 | 50 (14.2) | LC | FISH | FGFR1/CEN8 ratio ≥ 2.0; tumor cell percentage with ≥ 15 signals ≥ 10%; or average number of signals/tumor cell nucleus ≥ 6 |

| Tran [42] | 2013 | Australia | 264 | 49 (18.6) | NSCLC | SISH | FGFR1/CEP8 ratio ≥ 2.0; mean FGFR1 signals per tumor cell ≥ 6.0; or percentage of tumor cells containing FGFR1 clusters ≥ 10% |

| Kim [28] | 2013 | Korean | 262 | 34 (15.3) | SCC | FISH | Gene copy number ≥ 9 |

| Craddock [29] | 2013 | Canada | 121 | 22 (18.2) | SCC | FISH | Mean FGFR1 copy number per cell > 5.0 |

| Gadgeel [39] | 2013 | United States | 345 | 17 (4.9) | NSCLC | RT-PCR | Copy number variations > 3.5 |

| Ren [41] | 2013 | China | 59 | 29 (49.2) | NSCLC | RT-PCR | > 2-fold compared with their adjacent normal counterparts |

| Schildhaus [27] | 2012 | Germany | 400 | 60 (15.0) | NSCLC | FISH | (1) FGFR1/CEN8 ratio ≥ 2.0; (2) average number of FGFR1 signals per tumor cell nucleus ≥ 6; (3) percentage of tumor cells containing ≥ 15 FGFR1 signals or large clusters ≥ 10% |

| Heist [30] | 2012 | United States | 226 | 37 (16.4) | SCC | FISH | FGFR1/CEP8 ratio ≥ 2.2 |

| Goke [21] | 2012 | Germany | 72 | 12 (16.7) | SCC | FISH | Gene copy number ≥ 9 |

| Kohler [35] | 2012 | Germany | 260 | 20 (7.7) | LC | FISH | Gene copies ≥ 4 |

| Sasaki [40] | 2012 | Japan | 100 | 32 (32.0) | NSCLC | RT-PCR | > 4 copies |

| Dutt [9] | 2011 | United States | 732 | 44 (6.0) | NSCLC | SNP | > 3.25 copies |

| D Wang [38] | 2014 | China | 142 | 24 (16.9) | SCC | FISH | FGFR1/CEP8 ratio ≥ 2.0 or FGFR1 signals per tumor cell nucleus ≥ 6 |

| Weiss [34] | 2010 | Germany | 153 | 34 (22.2) | SCC | FISH | Gene copy number > 9 |

| LP Zhang [43] | 2015 | China | 77 | 6 (7.8) | SCLC | SISH | FGFR1 copies of ≥ 6 or FGFR1/CEN8 ratio ≥ 2 |

| Thomas [36] | 2014 | United States | 68 | 5 (7.4) | SCLC | FISH | FGFR1/CEN8 ratio > 2 |

| Schultheis [18] | 2014 | Germany | 251 | 14 (5.6) | SCLC | FISH | (1) FGFR1/CEN8 ratio ≥ 2.0; (2) FGFR1 gene count per tumor cell ≥ 6.0; (3)percentage of tumor cells containing ≥ 15 FGFR1 gene copies ≥ 10%; (4) percentage of tumor cells containing ≥ 5 FGFR1 gene copies ≥ 50% |

| Peifer [37] | 2012 | Germany | 51 | 3 (5.9) | SCLC | FISH | Copy number ≥ 3.5 |

| Ross [44] | 2014 | United States | 98 | 4 (4.1) | SCLC | DNA | N/A |

FISH – fish in situ hybridization, FGFR1+ – fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 amplification, CEN8 – centromere 8, SNP – single-nucleotide polymorphism, LC – lung cancer, N/A – not available.

Table II.

FGFR1 amplification in different pathological subtypes

| Author | Country | FGFR1 amplification, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SCC | ADC | ||

| Sousa | Portugal | 5 (20.8) | 5 (14.7) |

| Cihoric | Switzerland | 35 (20.7) | 3 (2.2) |

| Toschi | United States | 39 (28.3) | 28 (11.5) |

| Seo | Korea | 25 (18.0) | 7 (3.0) |

| Russell | Australia | 40 (22.5) | 0 (0) |

| Tran | Australia | 25 (24.8) | 13 (11.3) |

| Gadgeel | United States | 7 (5.1) | 7 (4.1) |

| Schildhaus | Germany | 58 (20.0) | 0 (0) |

| Kohler | Germany | 14 (10.5) | 3 (4.7) |

| Sasaki | Japan | 27 (41.5) | N/A |

| Dutt | United States | 12 (21.0) | 20 (3.4) |

Test of heterogeneity

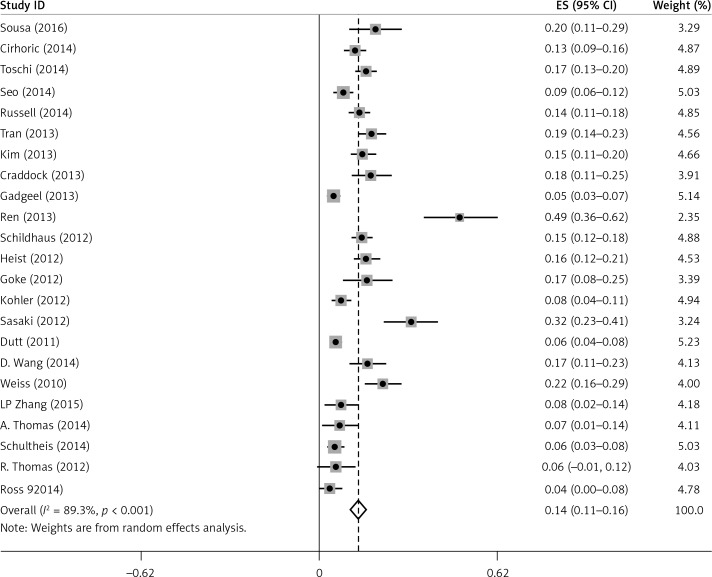

There was some heterogeneity among studies regarding the prevalence of FGFR1 amplification (I 2 = 89.3%, p < 0.001) (Figure 2).

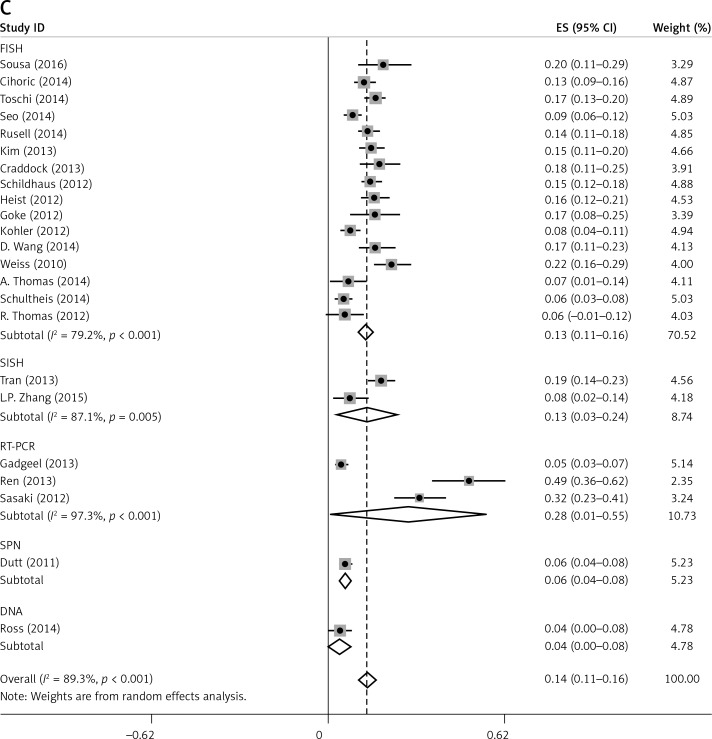

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis of FGFR1 amplification rate in all studies

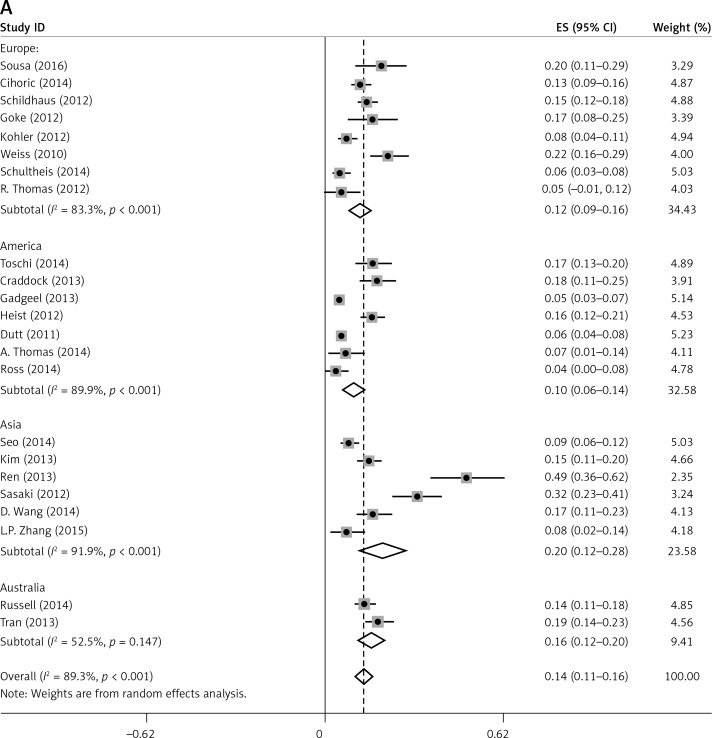

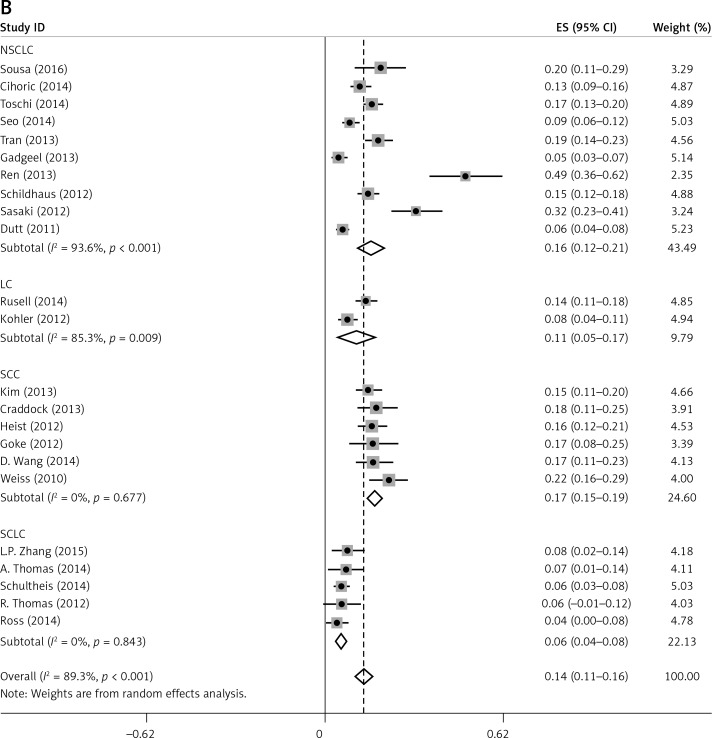

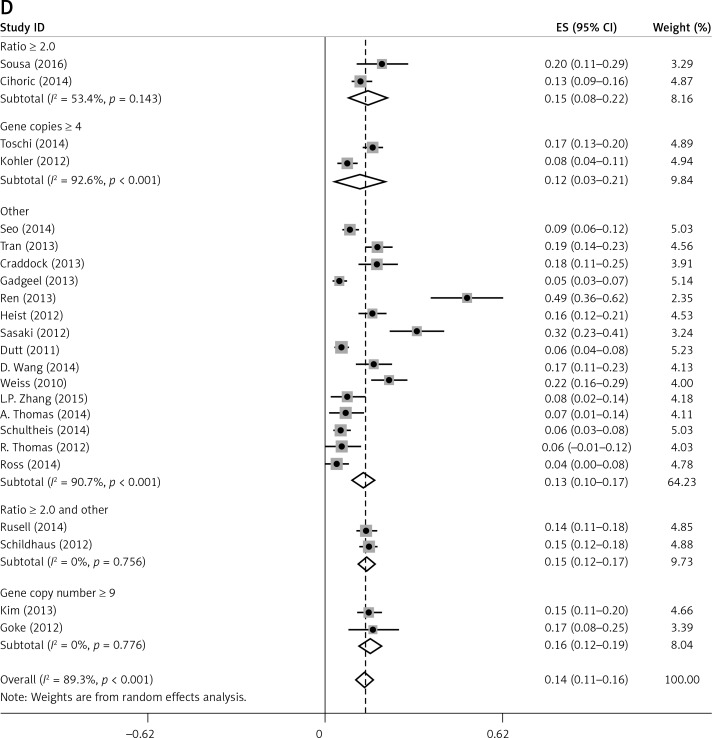

Subgroup analyses according to geographic region, pathologic type, test method, and definition of FGFR1 amplification revealed the following findings regarding heterogeneity from the same geographic region (Europe: I2 = 83.3%, p < 0.001; United States: I2 = 89.9%, p < 0.001; Asia: I2 = 91.9%, p < 0.001; Australia: I2 = 52.5%, p = 0.147; Figure 3 A), the same pathologic type (SCC: I2 = 0.0%, p = 0.677; SCLC: I2 = 0.0%, p = 0.843; NSCLC: I2 = 93.6%, p < 0.001; Figure 3 B), the same test method (FISH: I2 = 79.2%, p < 0.001; SISH: I2 = 87.1%, p = 0.005; Figure 3 C); the same definition of FGFR1 amplification (ratio ≥ 2.0: I2 = 53.4%, p = 0.143; gene copy number > 9: I2 = 0.0%, p = 0.776; Figure 3 D). Thus, these results show no significant heterogeneity among studies for SCC, SCLC, the same definition of FGFR1 amplification, and Australia (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Subgroup Analysis of FGFR1 Amplification Rate. Meta-analysis of FGFR1 amplification rate in studies using the same geographic region (A). Same pathologic type (B) Same test method (C) Same definition of FGFR1 amplification (D)

Prevalence of FGFR1 gene amplification

RRs were estimated for the rate of FGFR1 amplification in different types of lung cancer. There were 2285 SCC, 1860 ADC, and 545 SCLC patients who participated in the 23 studies included in this analysis; of these, there were 450, 87, and 32 patients, respectively, who exhibited FGFR1 amplification. The prevalence of FGFR1 amplification was significantly higher in SCC than that in ADC (RR = 5.2, 95% CI: 4.1–6.7) and SCLC (RR = 4.2, 95% CI: 2.9–6.1); it was also significantly higher in ADC than that in SCLC (RR = 0.8, 95% CI: 0.6–1.3). Of 3731 NSCLC patients who participated in the 12 studies, 463 exhibited FGFR1 amplification (93 in Asia and 370 in other geographic regions). The mean FGFR1 amplification rate was 30.0% (95% CI: –0.2 to 0.84) in Asia, 13.7% (95% CI: 0.1–0.2) in Europe, 10.8% (95% CI: –0.6 to 0.9) in the United States, and 12.9% (95% CI: –0.6 to 0.9) in Australia. The rate of FGFR1 amplification was higher in Asians than that in non-Asians (RR = 1.9, 95% CI: 1.5–2.4).

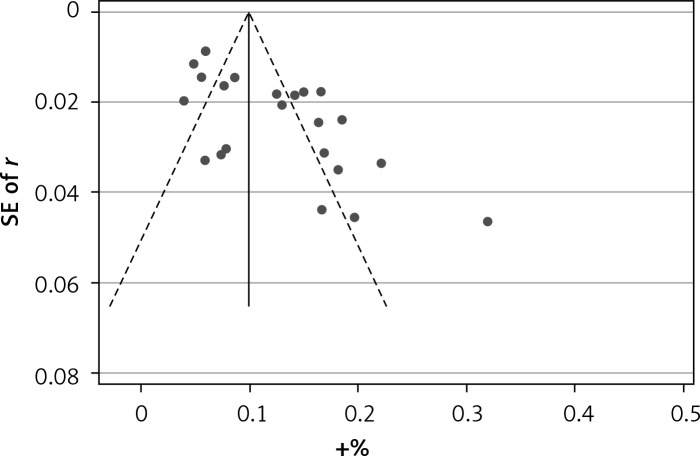

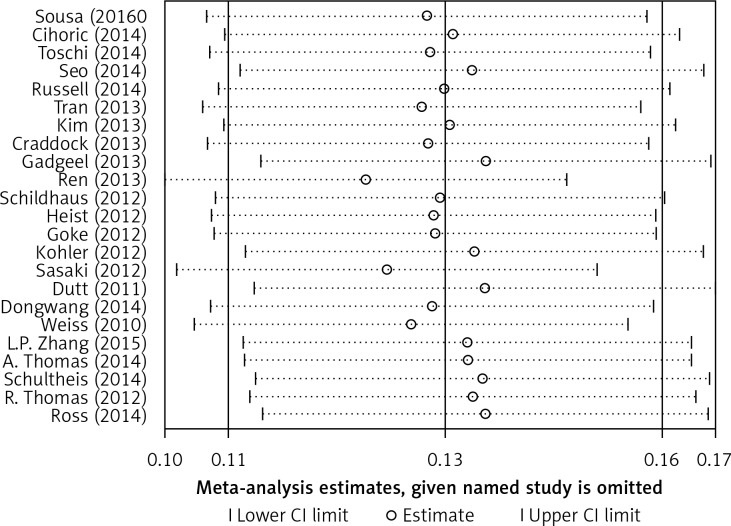

Publication bias and sensitivity analyses

Begg’s funnel plot and Egger’s regression test were applied to detect publication bias in the meta-analysis. In all included studies, funnel plot asymmetry was found (p = 0.006), with a 95% CI of –0.03 to 6.96 in Egger’s test. Therefore, publication bias was evident from the analysis (Figure 4). Sensitivity analyses were performed to assess the impact of individual studies on the results. As shown in Figure 5, we found no significant difference among the 23 studies.

Figure 4.

Begg’s funnel plot with pseudo 95% confidence limits

Figure 5.

Sensitivity analyses

Discussion

This meta-analysis indicated that the prevalence of FGFR1 amplification ranged from 4.9% to 49.2% in NSCLC, 5.1% to 41.5% in SCC, 0% to 14.7% in ADC, and 0% to 7.8% in SCLC. In addition, we found that FGFR1 amplification occurs more frequently in SCC than in ADC and SCLC. In the subgroup analyses, no significant heterogeneity was detected for SCC, SCLC, and Australia. We also found that the prevalence of FGFR1 amplification was higher in Asians than in non-Asians.

Wang et al. [22] reviewed a total of 12 studies involving 3178 lung SCC patients and suggested that FGFR1 amplification occurs more frequently in male patients, SCC, and smokers and that FGFR1 amplification is a risk factor for poor prognosis among Asian patients with SCC. In contrast, Jiang et al. [19] reviewed a total of 13 studies involving 1798 lung SCC patients and suggested that sex, stage, ethnicity, and test methods have no influence on FGFR1 amplification. The conclusions were therefore inconsistent; however, these reviews involved only patients with SCC.

We sought to examine the association between FGFR1 gene amplification, pathological characteristics, and ethnicity in lung cancer. This meta-analysis was performed with a total of 23 studies involving 5252 lung cancer patients and included data on Chinese patients. However, our systematic review with meta-analysis has some limitations that should be acknowledged. Firstly, the number of included studies was relatively small; thus more data with patients from different ethnicities are needed to conduct a thorough analysis. Secondly, it is possible that there is some degree of publication bias in this area of research.

To identify the source of heterogeneity, we performed subgroup analyses for lung cancer type and ethnicity and found that heterogeneity was non-existent for studies using the same ethnicity and lung cancer type. Subgroup analysis for the FGFR1 amplification rate evaluated using the same method showed that studies performed using FISH were approximately heterogeneous. However, after pooling the data from studies using the same definition of FGFR1 amplification, there was no heterogeneity. To encourage the widespread evaluation of FGFR1 amplification in clinical diagnostics and research laboratories, the definition and test methods should be standardized.

To determine the association between FGFR1 gene amplification and pathological characteristics, as well as ethnicity in lung cancer, RRs and the corresponding 95% CIs were calculated for the rate of FGFR1 amplification. The prevalence of FGFR1 amplification was significantly higher in SCC than in ADC and SCLC, and it was higher in Asians than in non-Asians. More studies are needed to determine whether there is a significant difference between the rates of FGFR1 amplification in different ethnicities.

For the treatment of NSCLC, the late provision of palliative care to patients limits improvements in the quality of life [45]. Furthermore, targeted therapy is also important. The current study is an updated comprehensive meta-analysis of FGFR1 amplification in lung cancer and indicates that FGFR1 amplification may become a potential new therapeutic target for specific patient populations and cancer subtypes. Because patients with SCC of the lung have limited options in terms of systemic therapies, they might benefit from targeted therapy. Currently, treatment with dovitinib, which inhibits FGFR, has demonstrated modest efficacy in patients with advanced SCC and FGFR1 amplification [46]. However, in contrast to targeted therapy in ADC, the results of trials targeting FGFR1 in squamous cell lung cancers have generally been disappointing. Gene amplification or overexpression of FGFR1 may not be a sufficiently robust predictor of the efficacy of FGFR1 inhibitors [14]. Therefore, the value of FGFR1 amplification in lung cancer treatment needs to be further investigated.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:9–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Minna JD, Roth JA, Gazdar AF. Focus on lung cancer. Cancer Cell. 2002;1:49–52. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wistuba II. Genetics of preneoplasia: lessons from lung cancer. Curr Mol Med. 2007;7:3–14. doi: 10.2174/156652407779940468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sørensen M, Pijls-Johannesma M, Felip E, ESMO Guidelines Working Group Small-cell lung cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(Suppl 5):v120–5. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Meerbeeck JP, Fennell DA, De Ruysscher DK. Small-cell lung cancer. Lancet. 2011;378:1741–55. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60165-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanna N, Bunn PA, Jr, Langer C, et al. Randomized phase III trial comparing irinotecan/cisplatin with etoposide/cisplatin in patients with previously untreated extensive-stage disease small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2038–43. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.8595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharma D, Newman TG, Aronow WS. Lung cancer screening: history, current perspectives, and future directions. Arch Med Sci. 2015;11:1033–43. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2015.54859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wistuba II, Gelovani JG, Jacoby JJ, Davis SE, Herbst RS. Methodological and practical challenges for personalized cancer therapies. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8:135–41. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dutt A, Ramos AH, Hammerman PS, et al. Inhibitor-sensitive FGFR1 amplification in human non-small cell lung cancer. PLoS One. 2011;6:20351. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sousa V, Reis D, Silva M, et al. Amplification of FGFR1 gene and expression of FGFR1 protein is found in different histological types of lung carcinoma. Virchows Arch. 2016;469:173–82. doi: 10.1007/s00428-016-1954-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Toschi L, Finocchiaro G, Nguyen TT, et al. Increased SOX2 gene copy number is associated with FGFR1 and PIK3CA gene gain in non-small cell lung cancer and predicts improved survival in early stage disease. PLoS One. 2014;9:e95303. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rooney C, Geh C, Williams V, et al. Characterization of FGFR1 locus in sqNSCLC reveals a broad and heterogeneous amplicon. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0149628. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reck M, Kaiser R, Eschbach C, et al. A phase II double-blind study to investigate efficacy and safety of two doses of the triple angiokinase inhibitor BIBF 1120 in patients with relapsed advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:1374–81. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lim SH, Sun JM, Choi YL, et al. Efficacy and safety of dovitinib in pretreated patients with advanced squamous non-small cell lung cancer with FGFR1 amplification: a single-arm, phase 2 study. Cancer. 2016;122:3024–31. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Turner N, Grose R. Fibroblast growth factor signalling: from development to cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:116–29. doi: 10.1038/nrc2780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wesche J, Haglund K, Haugsten EM. Fibroblast growth factors and their receptors in cancer. Biochem J. 2011;437:199–213. doi: 10.1042/BJ20101603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wynes MW, Hinz TK, Gao D, et al. FGFR1 mRNA and protein expression, not gene copy number, predict FGFR TKI sensitivity across all lung cancer histologies. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:3299–309. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schultheis AM, Bos M, Schmitz K, et al. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1) amplification is a potential therapeutic target in small-cell lung cancer. Modern Pathol. 2014;27:214–21. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2013.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang T, Gao G, Fan G, Li M, Zhou C. FGFR1 amplification in lung squamous cell carcinoma: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Lung Cancer. 2015;87:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2014.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berger W, Setinek U, Mohr T, et al. Evidence for a role of FGF-2 and FGF receptors in the proliferation of non-small cell lung cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 1999;83:415–23. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19991029)83:3<415::aid-ijc19>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Göke F, Franzen A, Menon R, et al. Rationale for treatment of metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the lung using FGFR inhibitors. Chest. 2012;142:1020–6. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Y, Gao W, Xu J, et al. The role of FGFR1 gene amplification as a poor prognostic factor in squamous cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis of published data. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:763080. doi: 10.1155/2015/763080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wells G, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. 2013. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp.

- 24.Mantel N, Haenszel W. Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1959;22:719–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–88. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–34. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schildhaus HU, Heukamp LC, Merkelbach-Bruse S, et al. Definition of a fluorescence in-situ hybridization score identifies high- and low-level FGFR1 amplification types in squamous cell lung cancer. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:1473–80. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim HR, Kim DJ, Kang DR, et al. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 gene amplification is associated with poor survival and cigarette smoking dosage in patients with resected squamous cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:731–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.8622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Craddock KJ, Ludkovski O, Sykes J, Shepherd FA, Tsao MS. Prognostic value of fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 gene locus amplification in resected lung squamous cell carcinoma. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8:1371–7. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182a46fe9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heist RS, Mino-Kenudson M, Sequist LV, et al. FGFR1 amplification in squamous cell carcinoma of the lung. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7:1775–80. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31826aed28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cihoric N, Savic S, Schneider S, et al. Prognostic role of FGFR1 amplification in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:2914–22. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seo AN, Jin Y, Lee HJ, et al. FGFR1 amplification is associated with poor prognosis and smoking in non-small-cell lung cancer. Virchows Arch. 2014;465:547–58. doi: 10.1007/s00428-014-1634-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Russell PA, Yu Y, Young RJ, et al. Prevalence, morphology, and natural history of FGFR1-amplified lung cancer, including squamous cell carcinoma, detected by FISH and SISH. Mod Pathol. 2014;27:1621–31. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2014.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weiss J, Sos ML, Seidel D, et al. Frequent and focal FGFR1 amplification associates with therapeutically tractable FGFR1 dependency in squamous cell lung cancer. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:62ra93. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kohler LH, Mireskandari M, Knosel T, et al. FGFR1 expression and gene copy numbers in human lung cancer. Virchows Arch. 2012;461:49–57. doi: 10.1007/s00428-012-1250-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thomas A, Lee JH, Abdullaev Z, et al. Characterization of fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 in small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2014;9:567–71. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peifer M, Fernández-Cuesta L, Sos ML, et al. Integrative genome analysis identify key somatic driver mutations of small cell lung cancer. Nat Genet. 2012;44:1104–10. doi: 10.1038/ng.2396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang D, Wang Z. The study of biological significance of fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 amplification in lung and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. 2014. pp. 1–132. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gadgeel SM, Chen W, Cote ML, et al. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 amplification in non-small cell lung cancer by quantitative real-time PCR. PLoS One. 2013;8:e79820. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sasaki H, Shitara M, Yokota K, et al. Increased FGFR1 copy number in lung squamous cell carcinomas. Mol Med Rep. 2012;5:725–8. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2011.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ren M, Hong M, Liu G, et al. Novel FGFR inhibitor ponatinib suppresses the growth of non-small cell lung cancer cells over-expressing FGFR1. Oncol Rep. 2013;29:2181–90. doi: 10.3892/or.2013.2386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tran TN, Selinger CI, Kohonen-Corish MR, et al. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1) copy number is an independent prognostic factor in non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2013;81:462–7. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2013.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang L, Yu H, Badzio A, et al. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 and related ligands in small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2015;10:1083–90. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ross JS, Wang K, Elkadi OR, et al. Next-generation sequencing reveals frequent consistent genomic alterations in small cell undifferentiated lung cancer. J Clin Pathol. 2014;67:772–6. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2014-202447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nowicki A, Farbicka P, Krajnik M. Late palliative care of patients with lung cancer may have a limited effect on quality of life – a pilot observational study. Arch Med Sci Civil Dis. 2016;1:e1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schoenborn CA, Adams PF, Peregoy JA. Health behaviors of adults. United States, 2008–2010. Vital Health Stat. 2013;257:1–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]