Abstract

Maternal smoking causes lower birth weight, birth defects, and other adverse pregnancy outcomes. Epidemiological evidence over the past four decades has grown stronger and the adverse outcomes attributed to maternal smoking and secondhand smoke exposure have expanded. This review presents findings of latent and persistent metabolic effects in offspring of smoking mothers like those observed in studies of maternal undernutrition during pregnancy. The phenotype of offspring of smoking mothers is like that associated with maternal undernutrition. Born smaller than offspring of nonsmokers, these children have increased risk of being overweight or obese later. Plausible mechanisms include in utero hypoxia, nicotine-induced reductions in uteroplacental blood flow, placental toxicity, or toxic growth restriction from the many toxicants in tobacco smoke. Studies have reported increased risk of insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes and hypertension although the evidence here is weaker than for overweight/obesity. Altered DNA methylation has been consistently documented in smoking mothers’ offspring, and these epigenetic alterations are extensive and postnatally durable. A causal link between altered DNA methylation and the phenotypic changes observed in offspring remains to be firmly established, yet the association is strong, and mediation analyses suggest a causal link. Studies examining expression patterns of affected genes during childhood development and associated health outcomes should be instructive in this regard. The adverse effects of exposure to tobacco smoke during pregnancy now clearly include permanent metabolic derangements in offspring that can adversely affect life-long health.

Keywords: diabetes, embryo, fetus, hypertension, obesity, tobacco

INTRODUCTION

Tobacco smoke contains thousands of known toxic components including known human carcinogens in addition to nicotine and carbon monoxide. Maternal smoking causes lower birth weight, birth defects, and other adverse pregnancy outcomes. Multiple reviews of the extant epidemiological evidence have been published and updated over the past four decades as the evidence has grown stronger and the adverse outcomes attributed to maternal smoking and secondhand smoke exposure have expanded (Abel, 1980; Abel, 1984; Abraham et al., 2017; Cnattingius, 2004; Koren, 1995; McEvoy & Spindel, 2017; Rogers, 2008; Stillman, Rosenberg, & Sachs, 1986; Walsh, 1994). Effects of maternal smoking on birth weight were recognized in the first U.S. Surgeon General’s Report in 1964, which cited an increased risk of being born weighing less than 2,500 g (USDHEW, 1964). Subsequent Surgeon General’s reports on Smoking and Health (USDHEW, 1979), The Health Consequences of Smoking for Women (USDHHS, 1980), Women and Smoking (USDHHS, 2001), The Health Consequences of Smoking (USDHHS, 2004), and The Health Consequences of Smoking—50-Years of Progress (USDHHS, 2014) clearly articulate the increasing realization of impacts of smoking during pregnancy. Notably, the 2014 Surgeon General’s Report finds that evidence is sufficient to infer a causal link between maternal smoking and orofacial clefts and suggestive to infer causal relationships between maternal smoking in early pregnancy and clubfoot, gastroschisis, and atrial septal defects. Evidence for causal relationships is also suggestive for maternal smoking and ectopic pregnancy, spontaneous abortion, and disruptive behavioral disorders in children. In a comprehensive systematic review of associations between maternal smoking and congenital malformations in observational studies with a total of 173,687 malformed cases and 11,674,332 unaffected controls, Hackshaw, Rodeck, and Boniface (2011) found significant positive relationships between maternal smoking and cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, craniofacial, ocular, limb/digit, gastrointestinal, and urogenital defects. An interesting finding was a reduced risk of hypospadias and skin defects in offspring of smoking mothers.

About 58 million nonsmokers in the United States are exposed to second-hand smoke (SHS, smoke exhaled by smokers or from burning tobacco products) (CDC, https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/tobacco/). Effects of prenatal and postnatal SHS exposure on children’s health were recognized over 20 years ago (Charlton, 1994), have been reviewed more recently (DiFranza, Aligne, & Weitzman, 2004), and were discussed in the 2006 Surgeon General’s Report on The Health Consequences of Involuntary Exposure to Tobacco Smoke (USDHHS, 2006). Recent reviews and meta-analyses demonstrate that exposure of pregnant women to SHS causes 40–60 g lower birth weight of offspring (Leonardi-Bee, Smyth, Britton, & Coleman, 2008; Salmasi et al., 2010), and a 1.5-fold increase in nonsyndromic orofacial clefts (Sabbagh et al., 2015). Using data from the National Birth Defects Prevention Study, Hoyt et al. (2016) found adjusted odds ratios (OR) for any versus no maternal SHS exposure and isolated birth defects that were significantly higher for neural tube defects, orofacial clefts, bilateral renal agenesis, amniotic band syndrome and atrial septal defects. This list is strikingly like that reported for maternal smoking, mentioned above (Hackshaw et al., 2011).

It is timely to briefly introduce the concept of thirdhand smoke, which is the residue left on surfaces in areas where smoking has occurred, and that may react, re-emit or become resuspended after active smoking has stopped (Matt et al., 2011). The health impacts of thirdhand smoke in humans remain to be elucidated, but recent research indicates that it is genotoxic to cells in culture and can be developmentally toxic in mice (Hang et al., 2017).

The literature discussed above primarily concerns adverse outcomes of maternal smoking and tobacco smoke exposure that are evident at birth. There is also a rich literature on adverse neurobehavioral (see Bublitz & Stroud, 2012 for review) and respiratory (see McEvoy & Spindel, 2017 for review) outcomes in children of mothers exposed to tobacco smoke that will not be discussed here. This review will present findings that address latent and persistent metabolic effects in offspring of smoking mothers that are similar to those observed in studies of the effects of maternal undernutrition during pregnancy. This latter body of work has led to the theory of the developmental origins of health and disease (DOHaD), which links childhood and adult health and disease outcomes to the intrauterine and early postnatal environment.

2 |. THE BARKER HYPOTHESIS, THE THRIFTY PHENOTYPE, AND DOHAD

David Barker and colleagues demonstrated in the early 1990s and later an inverse relationship between birth weight and risk of adult coronary heart disease, stroke, hypertension, and type 2 diabetes (Barker, 2006). These findings were attributed to variations in fetal nutrient delivery during a period of developmental plasticity in which the fetus responds to its environment with adaptive changes in organ structure and metabolism, and this idea became known as the Barker Hypothesis. Such changes are adaptive to the developmental environment but may become maladaptive and lead to increased risk of disease later in life. In the face of limiting nutrient supply the fetus adopts a “thrifty” phenotype to increase energy efficiency including decreased lipid metabolism, lower muscle mass, decreased insulin secretion, and decreased nephron number. These permanent alterations become maladaptive if the postnatal environment is one of ample or excess nutrient availability and can elevate risks of metabolic syndrome including obesity, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia. As the field of research comprising long-term effects of the developmental environment evolved, it became known as the DOHaD theory. There is now an abundant epidemiological, clinical, and animal research literature in support of the DOHaD theory. The idea has recently emerged that environmental chemical exposure during development could produce metabolic alterations that increase risk of latent health effects in a manner like maternal malnutrition (Heindel, 2018, 2019).

Evidence is mounting that one mechanism of adapting to the developmental environment and DOHaD is through changes to the epigenome. The epigenome includes the chemical modifications to chromatin, including DNA methylation and histone modifications as well as noncoding RNAs that can transiently or permanently alter patterns of gene expression. Gametogenesis and early development include periods of extensive revision of the epigenome that are likely to be sensitive to perturbation by environmental toxicants. Research in animal models demonstrates that early life exposures can result in changes to the epigenome and transcriptome that may underlie later-life increased risk of disease (BiancoMiotto, Craig, Gasser, van Dijk, & Ozanne, 2017).

Recent findings on effects of maternal smoking on the epigenome and long-term health effects in offspring, including obesity and type 2 diabetes, strongly suggest a DOHaD etiology. In the next sections, evidence from multiple studies will be presented in terms of both the latent health effects and the epigenetic alterations observed in offspring of smoking mothers.

3 |. MATERNAL SMOKING AND OFFSPRING METABOLIC SYNDROME

Components of the metabolic syndrome include abdominal obesity, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and insulin resistance, and these conditions increase risk of heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and stroke. A nutritionally impoverished intrauterine environment may contribute to the development of these conditions through inducing a thrifty phenotype that becomes maladaptive as offspring age. Environmental chemical exposure during development may cause a similar sequence of events through plausible mechanisms including interfering with intrauterine nutrient supply, placental toxicity, reduced uteroplacental blood flow, hypoxia, or endocrine disruption. Research in animal models has demonstrated that maternal exposures to endocrine disrupting chemicals during pregnancy can result in obesity in offspring, and such chemicals have been called “obesogens” (Janesick & Blumberg, 2016). While evidence for similar effects of diverse chemicals in humans is limited, maternal smoking presents a strong case as an obesogen operating through a DOHaD/thrifty phenotype mode of action.

4 |. MATERNAL SMOKING AND OFFSPRING OVERWEIGHT AND OBESITY

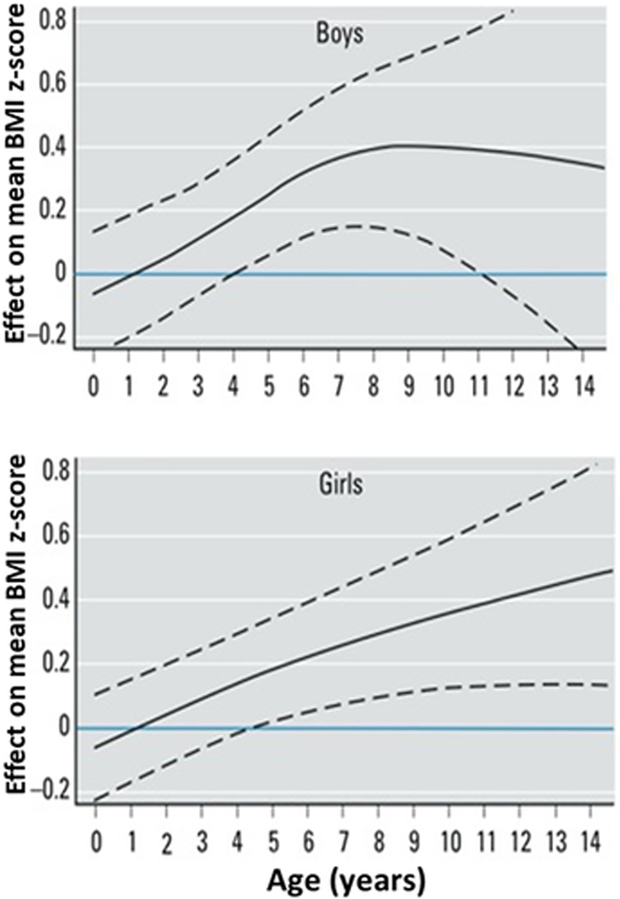

Offspring of smoking mothers are born smaller than those of nonsmoking mothers, indicating restricted intrauterine growth, and have a greater risk of being overweight or developing obesity or type 2 diabetes in adolescence or later in life. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of the relationship between maternal smoking and offspring overweight or obesity show a clear increased risk in children of smoking mothers. Studies through 2011 of maternal smoking and offspring obesity have been compiled and reviewed in a workshop report (Behl et al., 2013). Oken, Levitan, and Gillman (2008) conducted a metaanalysis of observational studies of maternal cigarette smoking during pregnancy and child overweight (BMI ≥85th percentile or BMI ≥90th percentile for age and sex). The analysis included 84,563 children from 14 studies, with ages ranging from 3 to 33 years at time of assessment. An OR is a ratio of the odds of having a condition in the exposed to the odds of the condition in the unexposed and can be adjusted for significant covariates or unadjusted. Offspring of smoking mothers were at increased risk of overweight compared to offspring of nonsmoking mothers, with a pooled adjusted OR of 1.50 (95% CI 1.36, 1.65). Riedel et al. (2014) analyzed 12 observational studies including 109,838 mother/child pairs. Pooled OR for overweight were 1.33 (95% CI 1.23, 1.44), and for obesity 1.60 (95% CI 1.37, 1.88). A systematic review and metaanalysis of studies through 2014 included 39 studies and 236,687 children up to age 18 from Europe, Australia, North and South America, and Asia (Rayfield & Plugge, 2017). Prevalence of maternal smoking ranged from 5.5 to 38.7%, prevalence of overweight ranged from 6.3 to 32.1%, and prevalence of obesity ranged from 2.6 to 17%. Children had higher odds of maternal smoking in pregnancy for overweight (OR 1.37, 95%CI 1.28, 1.46) and obesity (OR 1.55, 95% CI 1.40, 1.73). Using data from two German cohort studies with repeated anthropomorphic measures, children were followed longitudinally to chart their weights from birth to age 14 (Riedel et al., 2014). Mean and median BMI z-scores were lower at birth in children of mothers who smoked during pregnancy compared to those of nonsmoking mothers, but children of smoking mothers showed significantly higher BMI z-scores beginning at 4–5 years of age, and differences increased with age (Figure 1). In the KOALA Birth Cohort Study, children of mothers who smoked during pregnancy had lower birth weight and higher weight gain over the first postnatal year along with increasing overweight thereafter. Maternal smoking in pregnancy was associated with increased risk of the child exceeding the 85th percentile for BMI, waist circumference and skinfold thickness at 6–7 years of age (Timmermans et al., 2014). A similar pattern of increasing BMI differences between children exposed to secondhand smoke and unexposed children was observed between ages 10 and 18 (McConnell et al., 2015). Using data from the 35,370 participants in the Nurses’ Health Study II, Harris, Willett, and Michels (2013) demonstrated a dose response relationship between maternal smoking during pregnancy and daughters’ adiposity at ages 5–10, age 8 and adulthood, after adjustment for socioeconomic and other variables. Adjusted OR for daughters’ obesity at age 18 for maternal smoking of 1–14, 15–24 and 25+ cigarettes/day were 1.41 (1.14–1.75), 1.69 (1.31–2.18), and 2.36 (1.44–3.86), and ORs for obesity in adulthood were similar. No effect on adiposity was observed in daughters of mothers who quit smoking in the first trimester of pregnancy.

FIGURE 1.

Estimates of effect of maternal smoking during pregnancy on BMI z-scores for boys (above) and girls (below) compared with no smoking during pregnancy (horizontal line at zero). Dashed lines are 95% confidence intervals. Offspring of smokers are born with BMI lower than offspring of nonsmokers, have significantly higher BMIs by around 5 years of age, and differences in BMI continue to increase thereafter. Modified from Riedel, Fenske, et al., 2014, EHP 122:761–767

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis found associations between fathers’ smoking and offspring incidence of small for gestational age, birth defects, and childhood cancers (Oldereid et al., 2018). Interestingly, and perhaps providing evidence for an epigenetic mode of action, several studies have found a positive relationship between fathers’ preconception smoking and BMI of male offspring. Studies of the ALSPAC cohort showed a pattern of higher BMI, waist circumference and total fat mass in sons, but not daughters, of fathers that started smoking before 11 years of age (Northstone et al., 2014; Golding et al., 2019). Differences from controls increased with age and were statistically significant at 13 years of age and older. Children of smoking fathers were more likely to be overweight or obese at 5 years of age but not at 9 years in the Lifeways Cross-generation Cohort study (MejiaLancheros et al., 2018), and daughters whose fathers smoked during pregnancy were at higher risk of overweight and obesity in the study by Harris et al. (2013), presumably due to secondhand smoke exposure of the mother. In contrast, a study specifically addressing the link between paternal early-onset smoking and offspring BMI in the Nord-Trøndelag Health (HUNT) cohort (Carslake, Pinger, Romundstad, and Davey Smith, 2016) did not find an association between paternal preadolescent smoking and sons’ BMI yet reported a marginal relationship with daughters’ BMI.

5 |. MATERNAL SMOKING AND OFFSPRING INSULIN RESISTANCE AND DIABETES

The relationship between maternal smoking and insulin resistance, type 1 and type 2 diabetes in offspring has been less explored than relationships with overweight and obesity. A workshop (Behl et al., 2013) reviewed 18 studies on maternal exposure to smoking during pregnancy and offspring type 1 diabetes (T1D) and found that those studies did not support an association between maternal or paternal smoking during pregnancy and offspring T1D. However, it should be mentioned that the reviewers also listed two studies of childhood secondhand smoke exposure that both found a positive relationship with T1D (Hathout, Beeson, Ischander, Rao, & Mace, 2006; Skrodeniene et al., 2008). Studies examined by Behl et al. (2013) of maternal smoking and offspring type 2 diabetes (T2D), insulin resistance, hyperglycemia or metabolic syndrome found 12 studies and determined that it was not possible to reach a clear conclusion because of the diversity of endpoints assessed among these studies. Since that review, a study of 1,801 44 to 54-year-old women born in the Child Health and Development pregnancy cohort between 1959 and 1967 found that maternal smoking during pregnancy increased the risk (adjusted Relative Risk 2.4, 95% CI 1.4–4.1) of diabetes mellitus (did not discriminate between T1D and T2D) (La Merrill, Cirillo, Krigbaum, & Cohn, 2015). A study of 344 cases of T1D and three times as many controls matched for HLA haplotype and birth year among children born between 1999 and 2005 in a Swedish county found that maternal smoking during pregnancy was associated with higher risk of offspring T1D, OR 2.83, 95% CI 1.67–4.80 for 1–9 cigarettes per day and OR 3.91, 95% CI 1.22–12.51 for >9 cigarettes per day (Mattsson, Jönsson, Malmqvist, Larsson, & Rylander, 2015). The authors concluded that accounting for HLA haplotypes helped discern the elevated risk from maternal smoking. Jaddoe et al. (2014) evaluated associations of maternal and paternal smoking during pregnancy with T2D in daughters using data from 34,453 participants in the Nurses’ Health Study II. Maternal smoking only in the first trimester was associated with risk of T2D in daughters (adjusted hazard ratio 1.34, 95% CI 1.01,1.76). However, adjustment for current BMI attenuated the effect estimates and largely explained the results. In a study of 10-year old children, maternal smoking in the third trimester increased children’s insulin levels, and this effect was exacerbated if the child was exclusively breastfed (Thiering et al., 2011). Overall, the results of the studies discussed above raise a concern over a potential positive relationship between tobacco smoke exposure during pregnancy and offspring diabetes, but further studies are needed to better understand the potential role of confounders including obesity and postnatal smoke exposure. In a prospective pregnancy cohort, metabolic biomarkers in newborns of smokers and nonsmokers were compared. Outcomes were cord blood insulin, proinsulin, IGF-I, IGF-II, leptin, adiponectin, glucose-to-insulin ratio, and proinsulin-to-insulin ratio. Maternal smoking during pregnancy was associated with lower IGF-I (6.7 vs. 8.4 nmol/L, p = .006), and borderline higher proinsulin-to-insulin ratios. The authors concluded that these metabolic alterations may in part underlie increased future risk of metabolic disease. Other metabolic endpoints were not significantly affected by maternal smoking (Fang, Luo, Dejemli, Delvin, & Zhang, 2015).

6 |. MATERNAL SMOKING AND OFFSPRING BLOOD PRESSURE

While some studies on the effects of maternal smoking on offspring blood pressure have found a positive association, effect sizes tend to be small. In a study of 618 7.5 to 8-year-old children born preterm, systolic blood pressure was lower in smokers’ children compared to nonsmokers’ children born before 33 weeks gestation, but higher in children born at 33 or more weeks. There was a dose–response in both cases, with each 10 cigarettes per day being associated with a 1.5 mmHg fall or a 2.9 mmHg rise in systolic blood pressure, respectively (Morley, Leeson Payne, Lister, & Lucas, 1995). Infants born preterm or very low birth weight generally have higher systolic blood pressure (by about 3.8 mmHg) than term infants (de Jonge et al., 2013), so interpreting these contrasting results is difficult. Blake et al. (2000) found positive associations between maternal smoking during pregnancy and offspring systolic blood pressure, and a negative relationship between birth weight and blood pressure. The authors concluded that maternal smoking increased children’s blood pressure at ages one to six after correcting for birth weight and current weight. In a study of newborns, of 456 mothers of infants tested, 79.6% had no smoke exposure, 13.8% were exposed to secondhand smoke and 6.6% smoked during pregnancy (Geerts et al., 2007). Infants of smoking mothers had systolic blood pressure 5.4 mmHg higher than offspring of mothers not exposed to smoke during pregnancy, after considering birth weight, infant age, gender, nutrition, and maternal age. In findings supportive of effects of maternal smoking during pregnancy on offspring blood pressure, children of mothers who smoked while pregnant had thicker carotid artery intima-media thickness and lower vascular distensibility than children of nonsmokers, effects not seen in offspring of mothers who smoked only after pregnancy (Geerts, Bots, van der Ent, Grobbee, & Uiterwaal, 2012). Brion, Leary, Smith, and Ness (2007) used a broader set of potential confounders including breastfeeding, maternal education, and family social class, and concluded that effects of maternal smoking on offspring blood pressure are likely due to inadequate consideration of confounders.

The relationship between maternal smoking during pregnancy and offspring overweight and obesity is consistent, while the relationships of gestational tobacco smoke exposure to other facets of the metabolic syndrome raise concern but are inconclusive. Insulin resistance, diabetes, and blood pressure are related to birth weight, preterm birth, body composition, and other factors, and this confounding may in part underlie the inconsistency of relationships with parental smoking.

7 |. EFFECTS OF MATERNAL SMOKING ON OFFSPRING’S EPIGENOME

Epigenetic modifications include DNA methylation or hydroxymethylation on cytosine bases, histone modifications and noncoding RNAs, and these modifications in part determine chromatin structure and patterns of gene expression. DNA methylation during gametogenesis and early development follows a distinct and striking pattern including demethylation of primordial germ cell DNA during proliferation and migration from the yolk sac to the germinal ridge and de novo methylation during development of spermatogonia and oocytes; another rapid demethylation of DNA occurs in the zygote after fertilization (except for imprinted genes) that lasts until formation of the blastocyst (Smallwood & Kelsey, 2012). There have been numerous studies of the effects of maternal smoking on methylation of DNA in offspring, including consortia comprising different cohorts. In contrast, there is a relative paucity of studies on the effects of maternal smoking on histone modifications or noncoding RNAs.

Methylation of DNA occurs at the five-position of cytosines in cytosine-guanine dinucleotide (CpG) sites in promoters, enhancers, introns, exons and intergenic regions. Some regions of DNA, termed differentially methylated regions (DMRs) show regional patterns of methylation. Effects of methylation in these different contexts vary and are not well understood, although increased CpG methylation in promotors is generally associated with decreased gene expression. As noted above, there are sweeping changes in DNA methylation during specific stages of gametogenesis and embryogenesis, so it is plausible that environmental insults during these stages may disrupt normal patterns of DNA methylation. The degree to which such methylation changes during development persist or are associated with subsequent health outcomes is the subject of ongoing research. Cigarette smoke, arsenic, bisphenol A cadmium, lead, gestational diabetes, and folate supplementation are among the environmental exposures associated with altered fetal DNA methylation (see Green & Marsit, 2015, for review).

Methylation of DNA can be assessed at the global level, usually by immunological approaches and genomic DNA digestion with methylation-specific DNAses, yielding estimates of total genomic DNA methylation without identification of the sites of methylation. Global DNA methylation assessments largely represent CpG methylation in repetitive interspersed elements like LINEs and SINEs. In contrast, site-specific CpG methylation can be mapped using pyrosequencing, in which the DNA is treated with sodium bisulfite, which converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils while not altering unmethylated cytosines. Sites of methylation can then be identified by comparing the sequence of the bisulfite-treated DNA to that of untreated DNA from the same sample. While pyrosequencing can provide a comprehensive assessment of genomic CpG methylation, cost and technical difficulties have limited application of this technique at the whole-genome level. Less expensive and faster array-based methods have been developed and used for assessing specific CpG methylation, including the Illumina Infinium Human Methylation bead chip arrays that assess the methylation status of 27,000 (27 K) or 450,000 (450 K) CpG sites in bisulfite-treated DNA. Yet, even the 450 K BeadChip array covers only about 5% of the genome, and the sites covered are highly enriched for promoter regions. Most studies to date on effects of maternal smoking on offspring DNA methylation have employed the 27 K or 450 K BeadChip arrays, while one recent study reported whole genome pyrosequencing (Bauer et al., 2016).

An important variable to keep in mind is the type of tissue in which DNA methylation is assessed, as epigenetic modifications are highly cell-type specific. In newborns, this is usually cord blood, buccal cells or placenta, and these tissues contain multiple cell types. One study used tissues from elective first trimester (6–12 weeks) abortions to examine DNA methylation in samples of placenta and liver (Fa et al., 2018).

An early study of the effects of maternal smoking during pregnancy on global and gene-specific DNA methylation in newborn buccal cells identified decreased methylation in the repetitive element AluYb8 (the most abundant repetitive element in the human genome) and smoking-associated changes in methylation of eight genes including the proliferation-related genes tyrosine-protein kinase receptor UFO (AXL) and protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTPRO) (Breton et al., 2009). Another early study also found global DNA hypomethylation in cell-free serum DNA from cord blood of newborns of smoking mothers (Guerrero-Preston et al., 2010).

The placenta is sensitive to maternal smoking and several studies have examined the effects of maternal smoking on placental DNA methylation. Though a variety of methods (bisulfite pyrosequencing, 27 K and 450 K BeadChip arrays), differential methylation was observed in CpGs within genes including RUNX3, CYP1A1, HTRA2, HSD11B2, GTF2H2C, GTF2H2D, GPR135, HKR1, PURA, and NR3C1 (see Maccani & Maccani, 2015 for review). Suter and colleagues found placental hypomethylation of the promoter for CYP1A1, a gene known to be upregulated in smokers (Suter et al., 2010) and went on to assess correlative changes in placental DNA methylation and gene expression using the 27 K BeadChip array (Suter et al., 2011). They reported that expression of 623 genes was significantly altered in smokers, while 38 CpGs showed significant differential methylation (>10% change). The expression of only 10 genes was correlated with CpG methylation in non-smokers, while the expression of 438 genes was correlated with CpG methylation in smokers, the latter highly enriched for genes in oxidative stress pathways.

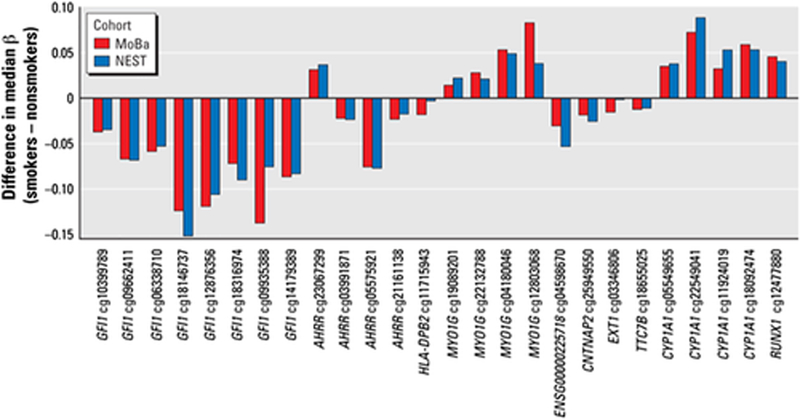

The relationship between maternal plasma cotinine (nicotine metabolite and biomarker of smoking) during pregnancy and CpG methylation was investigated using the 450 K BeadChip array for 1,062 cord blood samples from the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study (MoBa) (Joubert et al., 2012). Differential methylation at the genome-wide statistical level was detected for 26 CpGs in 10 genes. Findings were replicated for CpGs in the genes AHRR and CYP1A1 (detoxification pathways) and GFI1 (developmental processes) in samples from the unrelated Newborn Epigenetics Study (NEST) cohort from Durham, NC (Figure 2). To determine whether observed changes in CpG methylation at birth were related to prenatal smoke exposure or alternatively to inherited smoking-related epigenetic changes, Joubert et al. (2014) examined the timing of maternal smoke exposure as well as father’s smoking before conception and maternal grandmother’s smoking during pregnancy. No statistically significant effect was found for paternal or grandmaternal smoking or for maternal smoking before pregnancy or that stopped before 18 weeks gestation. These findings provide evidence that the effects were due to sustained maternal smoking during pregnancy. In a subsequent large meta-analysis of results from 13 cohorts (n = 6,685) in the Pregnancy and Childhood Epigenetics (PACE) consortium, Joubert et al. (2016) used the 450 K BeadChip to compare newborn blood DNA methylation in offspring of smokers and nonsmokers. The statistical power afforded by the large number of samples in this meta-analysis allowed detection of statistically significant differential methylation of over 6,000 CpGs, about half of which corresponded to 2,017 genes not previously identified as differentially methylated by smoking. Affected genes were enriched for pathways known to be involved in prenatal development and some genes known to be associated with maternal smoking and birth defects.

FIGURE 2.

Similar CpG methylation changes in relation to maternal smoking status in the Norwegian mother and child cohort study (MoBa) and the newborn epigenetics study (NEST) replication study. CpGs are grouped by gene, and all 26 CpGs affected in the MoBa cohort were changed in the same direction and similar magnitude in the NEST replicate. From Joubert et al., 2012, EHP 120:1425–1431. Many more CpGs significantly altered by maternal smoking have been discovered in subsequent studies (e.g., Bauer et al., 2016; Joubert et al., 2016)

An important question that remains concerns the durability of alterations in DNA methylation during development. In cord blood and blood taken at 7 and 17 years of age from children in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC), alterations in DNA methylation at CpG sites in some genes (GFI1, KLF13, ATP9A) were reversible, while CpG sites in other genes were not (AHRR, MYO1G, CYP1A1, CNTNAP2). The major contribution to altered methylation was attributed to a critical window of prenatal exposure (Richmond et al., 2015). In a discovery cohort of 132 adolescents, prenatal smoke exposure was associated with differential methylation of five CpGs in the MYO1G and CNTNAP2 genes (Lee et al., 2015), and in a replication cohort (n = 447), these investigators found that the same CpGs were differentially methylated at birth, during childhood and during adolescence through 17 years of age. The direction of change (higher methylation for MYO1G, lower methylation for CNTNAP2) was consistent at all ages, as was the magnitude of the effect. This study also replicated previous findings of differential methylation of CpGs in CYP1A1, AHRR, and GFI1. Findings from the PACE study discussed above (Joubert et al., 2016) also found evidence that changes in CpG methylation persisted in older children. Using samples from twins in the Peri/Postnatal Epigenetics Twin Study, Novakovic et al. (2014) found that hypomethylation of the CpGs in the AHRR gene in cord blood mononuclear cells in offspring of smokers versus nonsmokers persisted through 18 months of age, even in the absence of postnatal smoke exposure. The evidence to date indicates that at least some changes in DNA methylation during development are durable, lasting for years.

Studying the relationships between maternal smoking, altered DNA methylation and birth weight, Murphy et al. (2012) assessed the effect of maternal smoking on methylation of two imprinted genes critical for normal growth, IGF2 (expressed only on the paternal allele) and H19 (expressed only on the maternal allele), the expression of which are regulated by two DMRs, in umbilical cord blood. When pregnant smokers were categorized into those who quit vs. those that smoked throughout pregnancy, offspring of continued smokers had significantly higher levels of methylation at each of the three IGF2 DMR CpGs evaluated than did offspring of mothers who quit or nonsmoking mothers. The effect was significant in male offspring but not females. No difference in methylation was found at the H19 DMR. Computed OR for the association between low birth weight and continued cigarette smoking were OR = 4.16 (95%CI 1.44–11.99) and estimation of the proportion of smoking-related low birth weight contributed by IGF2 DMR differential methylation was 21% in male infants and 2.2% in female infants. Using the 450 K BeadChip array in an epigenome-wide association study, Küpers et al. (2015) found 35 differentially methylated CpGs, 23 of which remained after Bonferroni correction (p < 1 × 10−7). The 23 CpGs mapped to eight genes including AHRR, GFI1, MYO1G, CYP1A1, NEUROG1, CNTNAP2, FRMD4A, and LRP5. Mediation analysis showed that the CpG sites in the GFI1 (growth factor independent one transcription repressor) gene showed the strongest mediation of birth weight, followed by those in NEUROG1 (neurogenin 1). Three of the eight CpGs in GFI1 for which mediation was replicated explained 12–19% of the 202 g lower birth weight in offspring of smoking mothers. Using the 450 K BeadChip array to analyze infant whole blood samples from the Norway Facial Clefts Study, Markunas et al. (2014) identified 185 CpGs with significant methylation changes, and these CpGs represented 110 gene regions. Affected genes included those known to be related to nicotine dependence, smoking cessation, and placental and embryonic development.

Using samples from the LINA mother–child birth cohort (Herberth et al., 2006), Bauer et al. (2016) conducted an extensive epigenetic characterization of changes related to maternal smoking. They analyzed the complete DNA methylome at single base pair resolution by whole genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) in mothers and children around birth and through 4 years of age. They performed ChIP-seq of histone modification marks to evaluate chromatin conformation and linked changes in DNA methylation to transcriptional changes measured by RNA sequencing. Whole maternal blood and cord blood WGBS was done at 36 weeks gestation for maternal blood and at up to three time points (birth, 1 year, 4 years) for offspring. The WGBS analysis identified 1404 DMRs in children at the time of birth and 1953 DMRs in mothers related to maternal smoking. By comparing methylation of all CpGs in the genome at different ages in the same children, it was determined that 82% of the DMRs differentially methylated at birth by maternal smoking remained so at 1 year of age and was methylated at the same level at 4 years of age. To explore the relationship between differential DNA methylation and regions of active or repressed chromatin, two histone modifications delineating active chromatin (H3K4me1 and H3K27ac) and two repressive marks (H3K9me3 and H3K27me3) were mapped, identifying about 4.0 and 3.8% active chromatin in children and mothers, respectively, and about 1.8 and 2.2% chromatin in a repressed state. When smoking-associated transitions between active and repressed states were assessed, more transitions were from active to repressive in mothers, while the opposite was true for children. Significance levels for transitions were stronger near smoking-related DMRs, indicating that chromatin dynamics were linked to differential methylation associated with maternal smoking. Analysis of the locations of smoking-related DMRs indicated that about twice as many were in enhancers (outside the transcription start site) compared to promotors (near the transcription start site). Most of the enhancers were intragenic and acted on distal genes. Gene expression analysis (RNA-seq) in mothers and children identified pathways preferentially affected by smoking, including the WNT signaling pathway in both mothers and children. Changes in this pathway had the highest significance in children. Differential methylation of enhancers was a better predictor of target gene expression than was differential methylation of promotors. Interestingly, correlations between DNA methylation and gene expression in children were stronger at 1 year of age than at birth, suggesting that DNA methylation patterns present at birth increasingly affect target genes later in life.

Compared to DNA methylation, much less work has been conducted to examine the effects of prenatal tobacco smoke exposure on expression of microRNA (miRNA), which are ~22 nucleotide noncoding RNA molecules that can control gene expression by binding to target mRNAs that are then degraded. Key developmental processes including proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis are known to be regulated in part by miRNAs.

Maccani et al. (2010) tested the effect of cigarette smoke and smoke components on the expression of four miRNA in 25 placentas and three placental cell lines. The miRNAs, previously implicated in growth and development, were miR-16, miR-21, miR-146a, and miR-182. miR-16, miR-21, miR-146a were significantly downregulated in smoke-exposed placentas, and nicotine and benzo(a)pyrene elicited downregulation of miR-146a in TCL-1 cells.

The extant literature on altered DNA methylation in response to maternal smoking is consistent in demonstrating changes in offspring of mothers smoking during pregnancy. The genes that contain the affected CpGs include those that are known to be critical for xenobiotic metabolism as well as for normal prenatal development. DNA methylation patterns altered in utero can maintain the altered pattern for years, potentially changing the risk of disease later in life. The extent to which the DNA methylome is altered by maternal smoking remains to be fully elucidated, as the number of significantly altered CpGs has increased with the advancing technology used and the CpG coverage of the various approaches, from the 27 K BeadChip to the 450 K BeadChip to WGBS. Finally, while still scarce, there is some evidence of epigenetic changes related to paternal smoking. Using the 450KBeadChip to compare sperm DNA methylation between 78 smoking and 78 nonsmoking men, Jenkins et al. (2017) identified 141 differentially methylated CpGs along with an increased variance in the methylation patterns in smoking versus nonsmoking men.

8 |. CONCLUSIONS

The early-life phenotype of offspring of smoking mothers is reminiscent of the thrifty phenotype associated with under- or malnutrition. Born smaller on average than offspring of nonsmokers, these children have an increased risk of being overweight or obese by adolescence. Plausible prenatal mechanisms include developmental hypoxia due to carbon monoxide, nicotine-induced reductions in uteroplacental blood flow, placental toxicity, or effects on growth from the thousands of chemicals in cigarette smoke. Studies have also reported increased risk of insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, and hypertension in offspring of smoking mothers, although the evidence here is weaker than for overweight/obesity. Altered DNA methylation has been consistently documented in smoking mothers’ offspring, and the extent of these alterations are extensive and postnatally durable. A causal link between altered DNA methylation and the phenotypic changes observed in offspring remains to be firmly established, yet the association is strong and limited efforts to assess mediation suggest a causal link. Studies examining expression patterns of affected genes during childhood development and associated health outcomes are needed.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

All views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not represent views or policies of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, which wholly funded this work

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST The author has no conflict of interest in publishing this work.

REFERENCES

- Abel EL (1980). Smoking during pregnancy: A review of effects on growth and development of offspring. Human Biology, 52, 593–625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abel EL (1984). Smoking and pregnancy. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 16, 327–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham M, Alramadhan S, Iniguez C, Duijts L, Jaddoe VW, Den Dekker HT, … Turner S (2017). A systematic review of maternal smoking during pregnancy and fetal measurements with meta-analysis. PLoS ONE, 12, e0170946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker DJ (2006). Adult consequences of fetal growth restriction. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology, 49, 270–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer T, Trump S, Ishaque N, Thürmann L, Gu L, Bauer M, … Lehmann I (2016). Environment-induced epigenetic reprogramming in genomic regulatory elements in smoking mothers and their children. Molecular Systems Biology, 12, 861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behl M, Rao D, Aagaard K, Davidson TL, Levin ED, Slotkin TA, … Holloway AC (2013). Evaluation of the association between maternal smoking, childhood obesity, and metabolic disorders: A national toxicology program workshop review. Environmental Health Perspectives, 121, 170–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianco-Miotto T, Craig JM, Gasser YP, van Dijk SJ, & Ozanne SE (2017). Epigenetics and DOHaD: From basics to birth and beyond. Journal of Developmental Origins of Health and Disease, 8, 513–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake KV, Gurrin LC, Evans SF, Beilin LJ, Landau LI, Stanley FJ, & Newnham JP (2000). Maternal cigarette smoking during pregnancy, low birth weight and subsequent blood pressure in early childhood. Early Human Development, 57, 137–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breton CV, Byun HM, Wenten M, Pan F, Yang A, & Gilliland FD (2009). Prenatal tobacco smoke exposure affects global and gene-specific DNA methylation. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 180, 462–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brion MJ, Leary SD, Smith GD, & Ness AR (2007). Similar associations of parental prenatal smoking suggest child blood pressure is not influenced by intrauterine effects. Hypertension, 49, 1422–1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bublitz MH, & Stroud LR (2012). Maternal smoking during pregnancy and offspring brain structure and function: Review and agenda for future research. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 14, 388–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carslake D, Pinger PR, Romundstad P, & Davey Smith G (2016). Early-onset paternal smoking and offspring adiposity: Further investigation of a potential intergenerational effect using the HUNT study. PLoS ONE, 11, e0166952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlton A (1994). Children and passive smoking. The Journal of Family Practice, 38, 267–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cnattingius S (2004). The epidemiology of smoking during pregnancy: Smoking prevalence, maternal characteristics, and pregnancy outcomes. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 6(Suppl 2), S125–S140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jonge LL, Harris HR, Rich-Edwards JW, Willett WC, Forman MR, Jaddoe VW, & Michels KB (2013). Parental smoking in pregnancy and the risks of adult-onset hypertension. Hypertension, 61, 494–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFranza JR, Aligne CA, & Weitzman M (2004). Prenatal and postnatal environmental tobacco smoke exposure and children’s health. Pediatrics, 113(4 Suppl), 1007–1015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fa S, Larsen TV, Bilde K, Daugaard TF, Ernst EH, LykkeHartmann K, … Nielsen AL (2018). Changes in first trimester fetal CYP1A1 and AHRR DNA methylation and mRNA expression in response to exposure to maternal cigarette smoking. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology, 57, 19–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang F, Luo ZC, Dejemli A, Delvin E, & Zhang J (2015). Maternal smoking and metabolic health biomarkers in newborns. PLoS ONE, 10, e0143660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geerts CC, Bots ML, van der Ent CK, Grobbee DE, & Uiterwaal CS (2012). Parental smoking and vascular damage in their 5-year-old children. Pediatrics, 129, 45–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geerts CC, Grobbee DE, van der Ent CK, de Jong BM, van der Zalm MM, van Putte-Katier N, … Uiterwaal CS (2007). Tobacco smoke exposure of pregnant mothers and blood pressure in their newborns: Results from the wheezing illnesses study Leidsche Rijn birth cohort. Hypertension, 50, 572–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golding J, Gregory S, Northstone K, Iles-Caven Y, Ellis G, & Pembrey M (2019). Investigating possible trans/intergenerational associations with obesity in young adults using an exposome approach. Frontiers in Genetics, 10, 314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green BB, & Marsit CJ (2015). Select prenatal environmental exposures and subsequent alterations of gene-specific and repetitive element DNA methylation in fetal tissues. Current Environmental Health Reports, 2, 126–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero-Preston R, Goldman LR, Brebi-Mieville P, Ili-Gangas C, Lebron C, Witter FR, … Sidransky D (2010). Global DNA hypomethylation is associated with in utero exposure to cotinine and perfluorinated alkyl compounds. Epigenetics, 5, 539–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackshaw A, Rodeck C, & Boniface S (2011). Maternal smoking in pregnancy and birth defects: A systematic review based on 173 687 malformed cases and 11.7 million controls. Human Reproduction Update, 17, 589–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hang B, Wang P, Zhao Y, Sarker A, Chenna A, Xia Y, Snijders AM, Mao JH. 2017. Adverse health effects of thirdhand smoke: From cell to animal models. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 18 pii: E932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris HR, Willett WC, & Michels KB (2013). Parental smoking during pregnancy and risk of overweight and obesity in the daughter. International Journal of Obesity, 37, 1356–1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hathout EH, Beeson WL, Ischander M, Rao R, & Mace JW (2006). Air pollution and type 1 diabetes in children. Pediatric Diabetes, 7(2), 81–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heindel JJ (2018). The developmental basis of disease: Update on environmental exposures and animal models. Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology. 10.1111/bcpt.13118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heindel JJ (2019). History of the obesogen field: Looking back to look forward. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 10, 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herberth G, Daegelmann C, Weber A, Röder S, Giese T, Krämer U, … LISAplus Study Group. (2006). Association of neuropeptides with Th1/Th2 balance and allergic sensitization in children. Clinical and Experimental Allergy, 36, 1408–1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyt AT, Canfield MA, Romitti PA, Botto LD, Anderka MT, Krikov SV, … Feldkamp ML (2016). Associations between maternal periconceptional exposure to secondhand tobacco smoke and major birth defects. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 215, 613.e1–613.e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaddoe VW, de Jonge LL, van Dam RM, Willett WC, Harris H, Stampfer MJ, … Michels KB (2014). Fetal exposure to parental smoking and the risk of type 2 diabetes in adult women. Diabetes Care, 37, 2966–2973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janesick AS, & Blumberg B (2016). Obesogens: An emerging threat to public health. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 214, 559–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins TG, James ER, Alonso DF, Hoidal JR, Murphy PJ, Hotaling JM, … Aston KI (2017). Cigarette smoking significantly alters sperm DNA methylation patterns. Andrology, 5, 1089–1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joubert BR, Felix JF, Yousefi P, Bakulski KM, Just AC, Breton C, … London SJ (2016). DNA methylation in newborns and maternal smoking in pregnancy: Genome-wide consortium meta-analysis. American Journal of Human Genetics, 98, 680–696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joubert BR, Håberg SE, Bell DA, Nilsen RM, Vollset SE, Midttun O, … London SJ (2014). Maternal smoking and DNA methylation in newborns: In utero effect or epigenetic inheritance? Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 23, 1007–1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joubert BR, Håberg SE, Nilsen RM, Wang X, Vollset SE, Murphy SK, … London SJ (2012). 450K epigenome-wide scan identifies differential DNA methylation in newborns related to maternal smoking during pregnancy. Environmental Health Perspectives, 120, 1425–1431 Erratum in: Environ Health Perspect 2012, 120:A455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koren G (1995). Fetal toxicology of environmental tobacco smoke. Current Opinion in Pediatrics, 7, 128–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Küpers LK, Xu X, Jankipersadsing SA, Vaez A, la Bastide-van Gemert S, Scholtens S, … Snieder H (2015). DNA methylation mediates the effect of maternal smoking during pregnancy on birthweight of the offspring. International Journal of Epidemiology, 44, 1224–1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Merrill MA, Cirillo PM, Krigbaum NY, & Cohn BA (2015). The impact of prenatal parental tobacco smoking on risk of diabetes mellitus in middle-aged women. Journal of Developmental Origins of Health and Disease, 6, 242–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KW, Richmond R, Hu P, French L, Shin J, Bourdon C, … Pausova Z (2015). Prenatal exposure to maternal cigarette smoking and DNA methylation: Epigenome-wide association in a discovery sample of adolescents and replication in an independent cohort at birth through 17 years of age. Environmental Health Perspectives, 123, 193–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonardi-Bee J, Smyth A, Britton J, & Coleman T (2008). Environmental tobacco smoke and fetal health: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of Disease in Childhood. Fetal and Neonatal Edition, 93, F351–F361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccani JZ, & Maccani MA (2015). Altered placental DNA methylation patterns associated with maternal smoking: Current perspectives. Advances in Genomics and Genetics, 2015, 205–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccani MA, Avissar-Whiting M, Banister CE, McGonnigal B, Padbury JF, & Marsit CJ (2010). Maternal cigarette smoking during pregnancy is associated with downregulation of miR-16, miR-21, and miR-146a in the placenta. Epigenetics, 5, 583–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markunas CA, Xu Z, Harlid S, Wade PA, Lie RT, Taylor JA, & Wilcox AJ (2014). Identification of DNA methylation changes in newborns related to maternal smoking during pregnancy. Environmental Health Perspectives, 122, 1147–1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matt GE, Quintana PJ, Zakarian JM, Fortmann AL, Chatfield DA, Hoh E, … Hovell MF (2011). When smokers move out and non-smokers move in: Residential thirdhand smoke pollution and exposure. Tobacco Control, 20, e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattsson K1, Jönsson I, Malmqvist E, Larsson HE, & Rylander L (2015). Maternal smoking during pregnancy and offspring type 1 diabetes mellitus risk: Accounting for HLA haplotype. European Journal of Epidemiology, 30, 231–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell R, Shen E, Gilliland FD, Jerrett M, Wolch J, Chang CC, … Berhane K (2015). A longitudinal cohort study of body mass index and childhood exposure to secondhand tobacco smoke and air pollution: The Southern California Children’s health study. Environmental Health Perspectives, 123, 360–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy CT, & Spindel ER (2017). Pulmonary effects of maternal smoking on the fetus and child: Effects on lung development, respiratory morbidities, and life long lung health. Paediatric Respiratory Reviews, 21, 27–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mejia-Lancheros C, Mehegan J, Murrin CM, Kelleher CC, & Lifeways Cross-Generation Cohort Study Group. (2018). Smoking habit from the paternal line and grand-child’s overweight or obesity status in early childhood: Prospective findings from the lifeways cross-generation cohort study. International Journal of Obesity, 42, 1853–1870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morley R, Leeson Payne C, Lister G, & Lucas A (1995). Maternal smoking and blood pressure in 7.5 to 8 year old offspring. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 72, 120–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy SK, Adigun A, Huang Z, Overcash F, Wang F, Jirtle RL, … Hoyo C (2012). Gender-specific methylation differences in relation to prenatal exposure to cigarette smoke. Gene, 494, 36–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northstone K, Golding J, Davey Smith G, Miller LL, & Pembrey M (2014). Prepubertal start of father’s smoking and increased body fat in his sons: further characterisation of paternal transgenerational responses. Eur J Hum Genet, 22, 1382–1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novakovic B, Ryan J, Pereira N, Boughton B, Craig JM, & Saffery R (2014). Postnatal stability, tissue, and time specific effects of AHRR methylation change in response to maternal smoking in pregnancy. Epigenetics, 9, 377–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oken E, Levitan EB, & Gillman MW (2008). Maternal smoking during pregnancy and child overweight: Systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Obesity, 32, 201–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldereid NB, Wennerholm UB, Pinborg A, Loft A, Laivuori H, Petzold M, … Bergh C (2018). The effect of paternal factors on perinatal and paediatric outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Human Reproduction Update, 24, 320–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayfield S, & Plugge E (2017). Systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between maternal smoking in pregnancy and childhood overweight and obesity. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 71, 162–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richmond RC, Simpkin AJ, Woodward G, Gaunt TR, Lyttleton O, McArdle WL, … Relton CL (2015). Prenatal exposure to maternal smoking and offspring DNA methylation across the lifecourse: Findings from the Avon longitudinal study of parents and children (ALSPAC). Human Molecular Genetics, 24, 2201–2217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedel C, Fenske N, Müller MJ, Plachta-Danielzik S, Keil T, Grabenhenrich L, & von Kries R (2014). Differences in BMI zscores between offspring of smoking and nonsmoking mothers: A longitudinal study of German children from birth through 14 years of age. Environmental Health Perspectives, 122, 761–767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedel C, Schönberger K, Yang S, Koshy G, Chen YC, Gopinath B, … von Kries R (2014). Parental smoking and childhood obesity: Higher effect estimates for maternal smoking in pregnancy compared with paternal smoking--a meta-analysis. International Journal of Epidemiology, 43, 1593–1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers JM (2008). Tobacco and pregnancy: Overview of exposures and effects. Birth Defects Research. Part C, Embryo Today, 84, 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabbagh HJ, Hassan MH, Innes NP, Elkodary HM, Little J, & Mossey PA (2015). Passive smoking in the etiology of non-syndromic orofacial clefts: A systematic review and metaanalysis. PLoS ONE, 10, e0116963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmasi G, Grady R, Jones J, SD MD, & Knowledge Synthesis Group. (2010). Environmental tobacco smoke exposure and perinatal outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analyses. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 89, 423–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skrodeniene E, Marciulionyte D, Padaiga Z, Jasinskiene E, Sadauskaite-Kuehne V, & Ludvigsson J (2008). Environmental risk factors in prediction of childhood prediabetes. Medicina (Kaunas, Lithuania), 44, 56–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smallwood SA, & Kelsey G (2012). De novo DNA methylation: A germ cell perspective. Trends in Genetics, 28, 33–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stillman RJ, Rosenberg MJ, & Sachs BP (1986). Smoking and reproduction. Fertility and Sterility, 46, 545–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suter M, Abramovici A, Showalter L, Hu M, Shope CD, Varner M, & Aagaard-Tillery K (2010). In utero tobacco exposure epigenetically modifies placental CYP1A1 expression. Metabolism, 59, 1481–1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suter M, Ma J, Harris A, Patterson L, Brown KA, Shope C, … Aagaard-Tillery KM (2011). Maternal tobacco use modestly alters correlated epigenome-wide placental DNA methylation and gene expression. Epigenetics, 6, 1284–1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiering E, Brüske I, Kratzsch J, Thiery J, Sausenthaler S, Meisinger C, … GINIplus and LISAplus Study Groups. (2011). Prenatal and postnatal tobacco smoke exposure and development of insulin resistance in 10 year old children. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, 214, 361–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmermans SH, Mommers M, Gubbels JS, Kremers SP, Stafleu A, Stehouwer CD, … Thijs C (2014). Maternal smoking during pregnancy and childhood overweight and fat distribution: The KOALA birth cohort study. Pediatric Obesity, 9, e14–e25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Women and smoking A report of the surgeon General. Rockville (MD): U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service: Office of the Surgeon General, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking for Women. A Report of the Surgeon General. Washington: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health, Office on Smoking and Health, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Involuntary Exposure to Tobacco Smoke: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Coordinating Center for Health Promotion, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking: 50 Years of Progress. A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. Smoking and Health: Report of the Advisory Committee to the Surgeon General of the Public Health Service. Washington: U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Public Health Service, Center for Disease Control, 1964. PHS Publication No. 1103. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. Smoking and Health. A Report of the Surgeon General. Washington: U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health, Office on Smoking and Health, 1979. DHEW Publication No. (PHS) 79–50066. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh RA (1994). Effects of maternal smoking on adverse pregnancy outcomes: Examination of the criteria of causation. Human Biology, 66, 1059–1092. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]