Abstract

Background

Molecular analysis has revealed four subtypes of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC). One subtype identified for the presence of DNA damage repair deficiency can be targeted therapeutically with the poly (ADP‐ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor olaparib. We performed a single institution retrospective analysis of treatment response in patients with PDAC treated with olaparib who have DNA damage repair deficiency mutations.

Subjects, Materials, and Methods

Patients with germline or somatic mutations involving the DNA repair pathway were identified and treated with olaparib. The primary objective was to examine the objective response rate (ORR). The secondary objectives were assessing tolerability, overall survival, and change in cancer antigen 19‐9. Quantitative texture analysis (QTA) was evaluated from CT scans to explore imaging biomarkers.

Results

Thirteen individuals with metastatic PDAC were treated with Olaparib. The ORR to Olaparib was 23%. Median overall survival (OS) was 16.47 months. Four of seven patients with BRCA mutations had an effect on RAD51 binding, with a median OS of 24.60 months. Exploratory analysis of index lesions using QTA revealed correlations between lesion texture and OS (hepatic lesion tumor texture correlation coefficient [CC], 0.683, p = .042) and time on olaparib (primary pancreatic lesion tumor texture CC, 0.778, p = .023).

Conclusion

In individuals with metastatic PDAC who have mutations involved in DNA repair, Olaparib may provide clinical benefit. BRCA mutations affecting RAD51 binding domains translated to improved median OS. QTA of individual tumors may allow for additional information that predicts outcomes to treatment with PARP inhibitors.

Implications for Practice

Pursuing germline and somatic DNA sequencing in individuals with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma may yield abnormalities in DNA repair pathways. These individuals may receive benefit with poly (ADP‐ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibition. Radiomics and deep sequencing analysis may yet uncover additional information that may predict outcome to treatment with PARP inhibitors.

Keywords: Pancreatic cancer, PARP inhibitor, DNA repair

Short abstract

The use of radiomic techniques shows great potential to profile genomic associations between imaging features and tumor biology, as well as for prognostic and predictive features for candidates for targeted therapy. This retrospective analysis of pancreas ductal adenocarcinoma patients with DNA repair pathway mutations treated with olaparib at a single institution evaluated survival outcomes, safety, and exploratory analyses through radiomics.

Introduction

Recent progress has been made in the treatment of patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), but much work remains 1. As this is a leading cause of cancer death in Western societies, there is an urgent need to better select patients for current therapies and develop novel therapeutic strategies.

Poly (ADP‐ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors have recently been developed as cancer therapies for ovarian and breast cancers, and three—olaparib, niraparib, and rucaparib—have been U.S. Food and Drug Administration‐approved for women with ovarian cancer 2. Olaparib has recently been approved for metastatic BRCA mutated breast cancer 3. In a recent report, veliparib, another PARP inhibitor, was used to treat patients with PDAC having germline BRCA1/2 mutations, and although it was well tolerated, it was ineffective in these patients. This study indicates differences in the ways PARP inhibitors act as well as the importance of patient selection based on prior therapies, which affect responsiveness to PARP inhibitor‐based treatments 4. PARP inhibitors have several documented mechanisms of action, including the inhibition of base excision repair, capturing or “trapping” of PARP, and defective DNA repair by blocking PARP‐mediated repair of single‐strand breaks leading to double‐stranded breaks 4, 5. Tumors that have defective homologous DNA repair pathways are susceptible to PARP inhibitor therapy 6 and are associated with mutations in genes involved in the double‐stranded DNA repair pathway such as BRCA1, BRCA2, PALB2, and ATM 7. The targeted cancer cells are unable to maintain genomic integrity, resulting in cell death via a synthetic lethal effect.

Recently, molecular analysis has revealed four subtypes of PDAC, giving clinicians further insight into treating this deadly disease 8, 9. One subtype identified for the presence of DNA damage repair deficiency can be targeted by several old and emerging therapies. One such therapy that may be considered is PARP inhibitors that causes targeted genomic instability and cell death 10. The PARP inhibitor olaparib has shown clinical efficacy in those with advanced cancer and a germline BRCA1/2 mutation in a phase II study that enrolled 298 patients 6. Olaparib was administered at 400 mg twice a day with a primary endpoint of tumor response rate. In 23 individuals with refractory metastatic PDAC, a response rate of 22% (95% confidence interval [CI], 7.5–43.7) was seen 6. Olaparib has also been shown to be effective in other malignancies with mutations in the DNA repair pathway, such as in individuals with DNA damage response (DDR)‐defective metastatic castrate‐resistant prostate cancer who had mutations in the DNA repair genes BRCA2, ATM, FANCA, CHEK2, BRCA1, PALB2, HDAC2, RAD51, MLH3, ERCC3, MRE11, and NBN 11. There have been reports of responses seen to PARP inhibitors in individuals with pancreatic cancer with a germline mutation in either BRCA1 or BRCA2 6, 12, 13, and clinical trials are currently in development (NCT03140670, NCT02184195, NCT01585805).

Because of the relatively common DNA repair pathway mutations in PDAC as noted above, PARP inhibition may be a potential therapeutic option in individuals with advanced PDAC with DNA repair mutations. A recent phase III study by Golan et al. 14 focused on determining the efficacy of olaparib on patients with PDAC who had exclusively BRCA1/2 germline mutations. The study did not include patients with PDAC who progressed during the first 4 months of platinum‐based treatment. The median progression‐free survival (PFS) was significantly longer in the olaparib group than in the placebo group (7.4 months vs. 3.8 months; p = .004). Our study aimed to evaluate olaparib targeted therapy on patients with PDAC with germline and somatic DDR mutations, variant of unknown significance (VUS) mutations, and patients who progressed on platinum‐based therapy. We performed a retrospective analysis of patients with PDAC with DNA repair pathway mutations treated with olaparib at a single institution.

Radiomics has emerged as a novel approach to identify imaging features or phenotypes in solid tumors that might serve as noninvasive biomarkers of tumor biology, microenvironmental changes, and early measures of treatment response. Using a radiomic approach, conventional imaging techniques of computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging, and positron emission tomography scans can be interrogated using qualitative and quantitative methodologies to uncover unique imaging biomarkers associated with hallmarks of cancer and predictive, prognostic, and early treatment responses 15. We have recently demonstrated the potential of using radiomic techniques in a variety of tumor types 16, 17, 18, 19 as well as in immunotherapy settings not only to profile genomic associations between imaging features and tumor biology but also for prognostic and predictive features who might be candidates for targeted therapy.

This retrospective analysis of patients with PDAC with DNA repair pathway mutations treated with olaparib at a single institution evaluated outcomes (objective response rate [ORR], overall survival [OS], and cancer antigen [CA]19‐9 changes), assessed safety, and performed exploratory analyses through radiomics.

Subjects, Materials, and Methods

Study Population

A retrospective chart review identified patients with PDAC who had either a germline or somatic mutation in the DNA repair pathway, had received olaparib, and were treated from January 2013 until July 2018 at HonorHealth.

Data Collection

Data on individuals’ demographics, clinical history, laboratory values, germline and somatic sequencing results, personal and family history of cancer, treatment history, and imaging results were obtained after HonorHealth institutional review board approval.

Genetic Information

Germline testing was performed through Ambry Genetics (Aliso Viejo, CA), Myriad Genetics (Salt Lake City, UT), or Invitae (San Francisco, CA). All germline testing was performed through Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA)‐certified clinical diagnostic laboratories. Somatic testing was performed DNA from extracted cancer tissue through either Caris Life Sciences (Phoenix, AZ) or Foundation Medicine (Cambridge, MA) through CLIA‐certified clinical diagnostic laboratories.

Quantitative Texture Analysis

The quantitative texture analysis (QTA) measurements were obtained as previously described 20. Scans were typically obtained every 2 months, or earlier in cases with clinical concerns over disease progression. A single radiologist with 9 years of radiomic and QTA experience (R.K.) performed image analysis by placing regions of interest around the entire tumor volume of the most dominant liver metastasis and/or pancreatic lesion on baseline contrast enhanced CT scans of the abdomen obtained during portal venous phase using a biphasic pancreatic acquisition protocol. QTA is an analytic tool (TexRad, Essex, U.K.) that evaluates the texture appearance of tumors and tissue on conventional radiologic images. The tool provides a quantitative representation of signal intensities contained within individual pixels outlined by regions (or volumes) of interest based upon the tumor density (Hounsfield units; HU) for CT. A histogram frequency curve of the signal intensity is generated, followed by first‐order statistical results (mean, SD, mean positive pixel, entropy, skewness, and kurtosis). Statistical correlations of QTA with outcomes was evaluated using Spearman's correlation coefficient (CC), linear regression, receiver operating characteristic (ROC), and Kaplan‐Meier (K‐M) survival data. Statistical significance was considered when p ≤ .05.

Statistical Analysis

The primary endpoint was response rate according to RECIST 1.1. Tumor assessments according to RECIST 1.1 were performed at baseline and at subsequent visit(s) when available. Response rate is defined as those with partial response (PR) plus those with complete response (CR) while receiving olaparib as defined by RECIST 1.1. Disease control rate is defined as those with stable disease plus PR plus CR as defined by RECIST 1.1 criteria. Secondary end points included tolerability, length of OS, change in CA19‐9, and change in textural analysis through existing imaging. PFS was defined as event‐free survival of a patient on olaparib. OS was defined as the time of initiation of olaparib therapy until the time of death from any cause.

The full analysis set comprised all patients who received at least one dose of olaparib. Follow‐up time was measured from time of treatment initiation, and the median survival was calculated for all patients. Tolerability was assessed using descriptive statistics.

Results

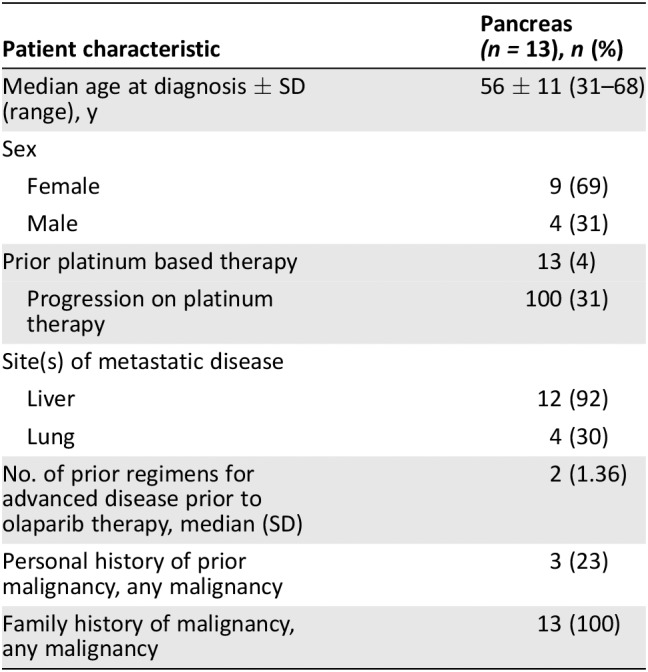

A total of 13 individuals with metastatic pancreatic cancer who were treated with olaparib were identified, and their demographics are summarized in Table 1. The median age at diagnosis of pancreatic cancer was 56 years, with a range of 31–68. Nine of the patients were women and three of the patients had a prior malignancy, with two subjects having a DNA repair‐associated malignancy (i.e. breast, ovarian cancer). Prior therapies prior to olaparib are presented in supplemental online Table 1. The median number of prior therapies prior to olaparib was 2.0, and all individuals had received platinum‐based (either oxaliplatin or cisplatin) chemotherapy. Four of the patients (patients 2, 8, 9, and 11) progressed on platinum therapy.

Table 1.

Patient demographic and clinical characterstics

| Patient characteristic | Pancreas (n = 13), n (%) |

|---|---|

| Median age at diagnosis ± SD (range), y | 56 ± 11 (31–68) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 9 (69) |

| Male | 4 (31) |

| Prior platinum based therapy | 13 (4) |

| Progression on platinum therapy | 100 (31) |

| Site(s) of metastatic disease | |

| Liver | 12 (92) |

| Lung | 4 (30) |

| No. of prior regimens for advanced disease prior to olaparib therapy, median (SD) | 2 (1.36) |

| Personal history of prior malignancy, any malignancy | 3 (23) |

| Family history of malignancy, any malignancy | 13 (100) |

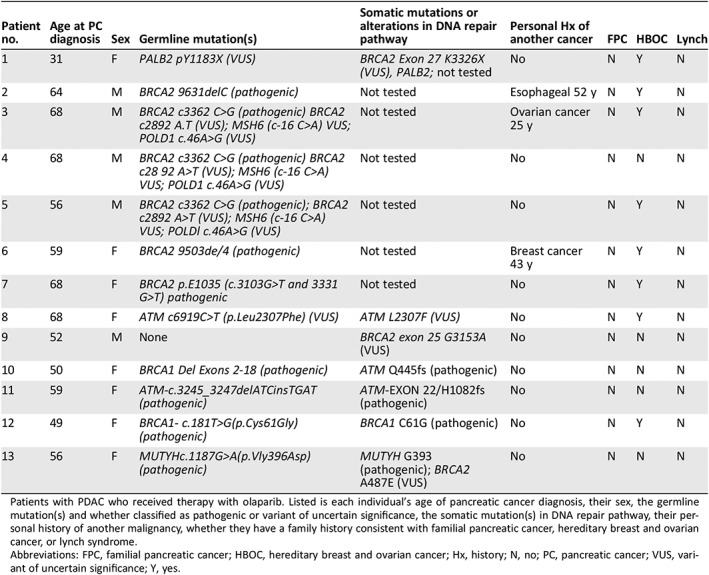

Table 2 lists the germline and somatic mutations, and their specific mutation is listed along with the classification: pathogenic or VUS of each individual with PDAC who received olaparib. Olaparib would not be typically offered to individuals with VUS mutations; however, these individuals with advanced pancreatic cancer have limited options. A discussion between the treating physician and the patient was had, with both agreeing to proceed forward with olaparib therapy. Table 2 shows the family history of malignancy present in all individuals, and eight of these would be classified under those malignancies that are associated with hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome 21. Three of the individuals had a prior history of cancer: one with ovarian cancer at the age of 25, another with breast cancer at the age of 43, and another with esophageal cancer at the age of 52. Of note is that no individual's family history met criteria for familial pancreatic cancer, which is defined as having a family history of at least two individuals diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, one of which is a first degree relative. Family histories consistent with Lynch syndrome 22 were also not seen in any of the 13 individuals.

Table 2.

Patient's genetic characteristics

| Patient no. | Age at PC diagnosis | Sex | Germline mutation(s) | Somatic mutations or alterations in DNA repair pathway | Personal Hx of another cancer | FPC | HBOC | Lynch |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 31 | F | PALB2 pY1183X (VUS) | BRCA2 Exon 27 K3326X (VUS), PALB2; not tested | No | N | Y | N |

| 2 | 64 | M | BRCA2 9631delC (pathogenic) | Not tested | Esophageal 52 y | N | Y | N |

| 3 | 68 | M | BRCA2 c3362 C>G (pathogenic) BRCA2 c2892 A.T (VUS); MSH6 (c‐16 C>A) VUS; POLD1 c.46A>G (VUS) | Not tested | Ovarian cancer 25 y | N | Y | N |

| 4 | 68 | M | BRCA2 c3362 C>G (pathogenic) BRCA2 c28 92 A>T (VUS); MSH6 (c‐16 C>A) VUS; POLD1 c.46A>G (VUS) | Not tested | No | N | N | N |

| 5 | 56 | M | BRCA2 c3362 C>G (pathogenic); BRCA2 c2892 A>T (VUS); MSH6 (c‐16 C>A) VUS; POLDl c.46A>G (VUS) | Not tested | No | N | Y | N |

| 6 | 59 | F | BRCA2 9503de/4 (pathogenic) | Not tested | Breast cancer 43 y | N | Y | N |

| 7 | 68 | F | BRCA2 p.E1035 (c.3103G>T and 3331 G>T) pathogenic | Not tested | No | N | Y | N |

| 8 | 68 | F | ATM c6919C>T (p.Leu2307Phe) (VUS) | ATM L2307F (VUS) | No | N | Y | N |

| 9 | 52 | M | None | BRCA2 exon 25 G3153A (VUS) | No | N | N | N |

| 10 | 50 | F | BRCA1 Del Exons 2‐18 (pathogenic) | ATM Q445fs (pathogenic) | No | N | N | N |

| 11 | 59 | F | ATM‐c.3245_3247delATCinsTGAT (pathogenic) | ATM‐EXON 22/H1082fs (pathogenic) | No | N | N | N |

| 12 | 49 | F | BRCA1‐ c.181T>G(p.Cys61Gly) (pathogenic) | BRCA1 C61G (pathogenic) | No | N | Y | N |

| 13 | 56 | F | MUTYHc.1187G>A(p.Vly396Asp) (pathogenic) | MUTYH G393 (pathogenic); BRCA2 A487E (VUS) | No | N | N | N |

Patients with PDAC who received therapy with olaparib. Listed is each individual's age of pancreatic cancer diagnosis, their sex, the germline mutation(s) and whether classified as pathogenic or variant of uncertain significance, the somatic mutation(s) in DNA repair pathway, their personal history of another malignancy, whether they have a family history consistent with familial pancreatic cancer, hereditary breast and ovarian cancer, or lynch syndrome.

Abbreviations: FPC, familial pancreatic cancer; HBOC, hereditary breast and ovarian cancer; Hx, history; N, no; PC, pancreatic cancer; VUS, variant of uncertain significance; Y, yes.

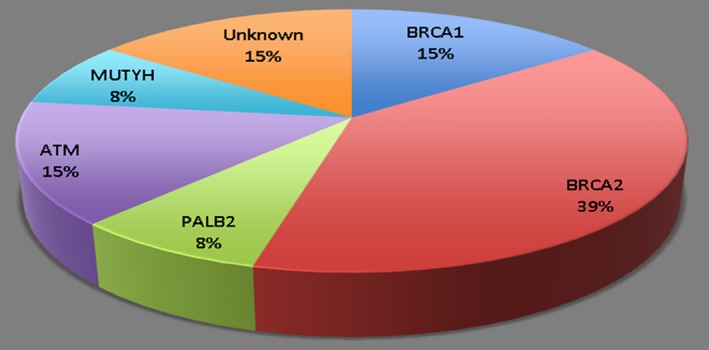

As shown in Figure 1 and Table 2, the most common germline mutation seen were those of BRCA2, with five individuals having pathogenic mutations. Out of the five, none had somatic testing in their tumor. The other indivicuals with mutations seen were one with PALB2, which was classified as a VUS (Y1183X), two individuals with a BRCA1 pathogenic mutation (Del exons 2–18 and c181T>G), and one individual with a pathogenic ATM mutation (c.3245_3247delATCinsTGAT). Two of the individuals did not have germline mutations present. One of the individuals had multiple germline mutations present, a pathogenic BRCA2 (c3362C>G) mutation, and an additional BRCA2 mutation that was classified as a VUS (c2892 A>T), MSH6 that was classified as a VUS (c‐16 C>A), and a POLD1 mutation that was classified as a VUS (c46A>G). One of the individuals that did not have a germline mutation did have a BRCA2 VUS in their tumor (exon 25 G1353A). Another individual had no mutations identified through either germline or somatic testing that would be considered pathogenic. However, this individual was diagnosed with ovarian cancer at the age of 25 and developed pancreatic cancer at the age of 46. This individual did have a somatic VUS mutation in C11orf30, which interacts with BRCA2 and has been associated with familial breast and ovarian cancers 23.

Figure 1.

Patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma germline mutations undergoing treatment with olaparib.

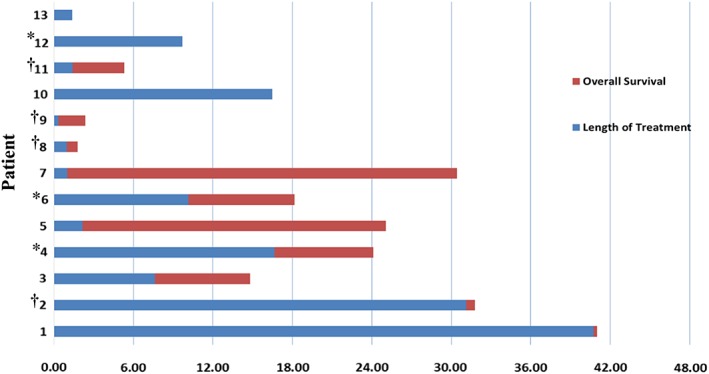

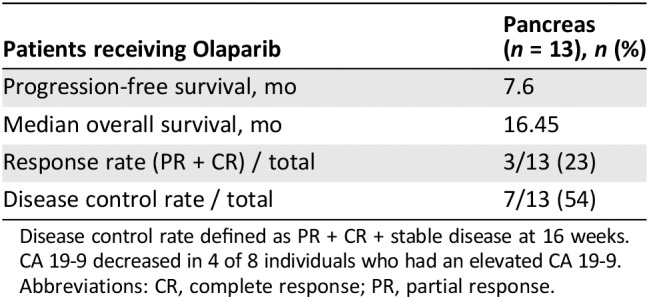

Figure 2, a swimlane, displaying each individual's time on treatment and subsequent OS after initiating olaparib therapy. Olaparib was well tolerated in most patients; treatment was discontinued in two patients because of pneumonitis. At the time of data cutoff, two of the individuals were still on olaparib. Seven of the individuals have passed away. Eight of the individuals were alive 12 months after initiating olaparib therapy, with five alive 2 years after olaparib initiation. Patient 2, who had progressed on platinum therapy, survived beyond 30 months after olaparib initiation. This individual was classified as having stable disease and considered to have clinical benefit but not a response to olaparib treatment. Table 3 depicts PFS, which was 7.6 months, the median OS, which was 16.47 months, and the response rate, which was 23%. The disease control rate, defined as CR plus PR plus stable disease, was 54%. Of the eight individuals with elevated CA19‐9 levels, the levels were decreased in four of them.

Figure 2.

Time (in months) on therapy and survival of individuals with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma receiving olaparib. *Patients who responded to olaparib treatment. †Patients who progressed on prior platinum therapy.

Table 3.

Patient length of treatment, survival, and response rates

| Patients receiving Olaparib | Pancreas (n = 13), n (%) |

|---|---|

| Progression‐free survival, mo | 7.6 |

| Median overall survival, mo | 16.45 |

| Response rate (PR + CR) / total | 3/13 (23) |

| Disease control rate / total | 7/13 (54) |

Disease control rate defined as PR + CR + stable disease at 16 weeks. CA 19‐9 decreased in 4 of 8 individuals who had an elevated CA 19‐9.

Abbreviations: CR, complete response; PR, partial response.

QTA was performed in subjects with hepatic metastasis (most common site of metastatic disease in this population) and/or primary pancreatic lesions. Additional analysis of uninvolved liver and pancreas parenchymal tissues was included, as was analysis of spinal muscles as a measure of sarcopenia. Of the 13 subjects, 9 had lesions suitable for analysis on their baseline contrast enhanced CT scans of the abdomen and pelvis acquired during the portal venous phase of enhancement. Eight subjects had their primary pancreatic lesions visible. Of the four subjects excluded, three subjects did not have visible hepatic metastasis on portal venous phase imaging and one subject received radiation therapy prior to treatment. Five subjects had surgical absence of the pancreas and/or no suitable target lesion for pancreatic lesion analysis.

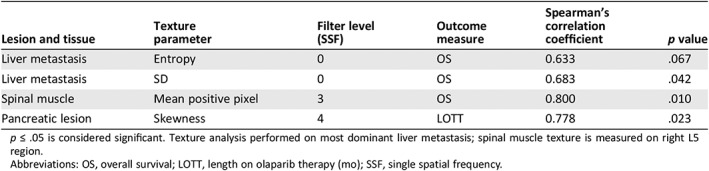

Table 4 lists the texture features of interest that were associated with outcomes. Three texture features—SD (liver metastasis: CC, 0.683; p = .042), entropy (liver metastasis: CC, 0.633; p = .067), and mean positive pixel (MPP; spinal muscle: CC, 0.800; p = .010) were found to be correlated with OS, with entropy trending toward significance. In addition, pancreatic lesion skewness (CC, 0.778; p = .023) was associated with length of time on treatment.

Table 4.

Quantitative texture analysis of subjects treated with olaparib

| Lesion and tissue | Texture parameter | Filter level (SSF) | Outcome measure | Spearman's correlation coefficient | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liver metastasis | Entropy | 0 | OS | 0.633 | .067 |

| Liver metastasis | SD | 0 | OS | 0.683 | .042 |

| Spinal muscle | Mean positive pixel | 3 | OS | 0.800 | .010 |

| Pancreatic lesion | Skewness | 4 | LOTT | 0.778 | .023 |

p ≤ .05 is considered significant. Texture analysis performed on most dominant liver metastasis; spinal muscle texture is measured on right L5 region.

Abbreviations: OS, overall survival; LOTT, length on olaparib therapy (mo); SSF, single spatial frequency.

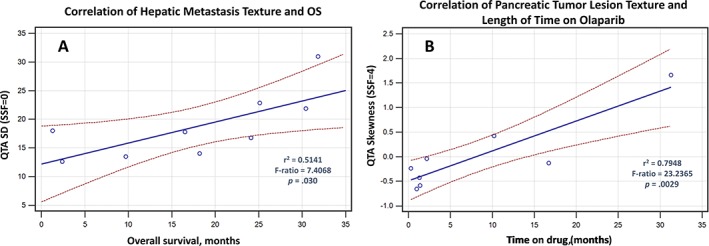

Figure 3 demonstrates the linear regression relationship between the lesion‐based texture features and outcomes. The median SD value for hepatic metastasis was 18.03, and median skewness value for pancreatic lesions was –0.185. Using these values as thresholds for determining the overall performance of predicting median OS of 10.8 months and median 8.6 months for length of time on treatment, a sensitivity analysis using ROC methodologies demonstrated excellent performance characteristics (supplemental online Fig. 1). Finally, K‐M analysis further demonstrated a significant separation of outcome results using these texture‐based threshold values (supplemental online Fig. 2).

Figure 3.

Correlation of quantitative texture analysis features with outcome. Least square regression analysis plots are shown that demonstrate (left graph) a linear correlation between hepatic metastatic variation in single texel (spatial scaling factor [SSF] = 0) signal intensities (Hounsfield units) on portal venous phase computed tomography scan to overall survival, suggesting that patients with greater heterogeneity of hepatic metastatic disease burden (i.e., larger SD) tend to have better overall survival outcomes. The right graph shows a linear correlation between primary pancreatic lesion and length of time on treatment based on the skewness of clustered signal texels (SSF = 4) within the tumor lesion. A higher skewness (positive) value implies that tumors with lower (more necrosis and/or less enhancing pixels) density texels remain on treatment longer. r2 = coefficient of determination; F‐ratio is coefficient from ANOVA, and a p value ≤ .05 is considered to be significant. Dotted lines refer to the 95% confidence intervals.

Abbreviation: QTA, quantitative texture analysis.

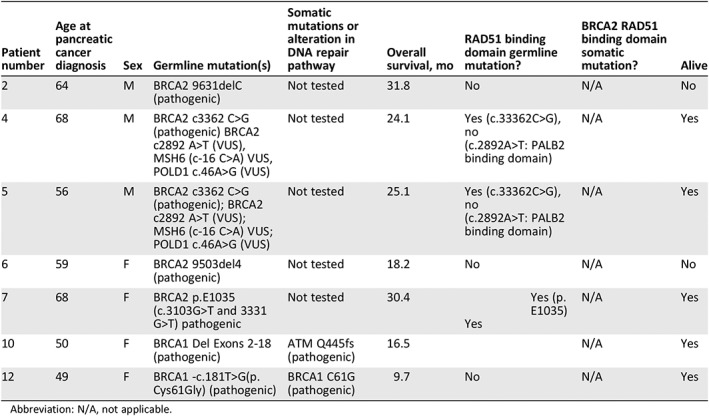

Additional genomic analysis was also carried out in each of the individuals with either a germline or somatic BRCA mutation. Table 5 lists each of these mutations in relation to whether the given mutation affected the RAD51 binding domain. RAD51 plays an important role in homologous strand exchange in DNA repair and binds to the PALB2 and BRCA2 scaffolding complex 24. Individuals with either a BRCA1 or BRCA2 germline mutation involving the RAD51 binding domain mutations had a mean survival of 24.03 months, and all four individuals are alive. Patient 12, an individual with a pathogenic BRCA1 mutation but not one that affects RAD51 binding, does have a mutation that falls in the RING domain, which is involved with ubiquitin ligase activity for BRCA1 and where BARD1 binds to BRCA1 25. This individual remains alive and is still undergoing therapy with olaparib.

Table 5.

BRCA1/2 mutations and their relationship in regards to RAD51 binding

| Patient number | Age at pancreatic cancer diagnosis | Sex | Germline mutation(s) | Somatic mutations or alteration in DNA repair pathway | Overall survival, mo | RAD51 binding domain germline mutation? | BRCA2 RAD51 binding domain somatic mutation? | Alive |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 64 | M | BRCA2 9631delC (pathogenic) | Not tested | 31.8 | No | N/A | No |

| 4 | 68 | M | BRCA2 c3362 C>G (pathogenic) BRCA2 c2892 A>T (VUS), MSH6 (c‐16 C>A) VUS, POLD1 c.46A>G (VUS) | Not tested | 24.1 |

Yes (c.33362C>G), no (c.2892A>T: PALB2 binding domain) |

N/A | Yes |

| 5 | 56 | M | BRCA2 c3362 C>G (pathogenic); BRCA2 c2892 A>T (VUS); MSH6 (c‐16 C>A) VUS; POLD1 c.46A>G (VUS) | Not tested | 25.1 |

Yes (c.33362C>G), no (c.2892A>T: PALB2 binding domain) |

N/A | Yes |

| 6 | 59 | F | BRCA2 9503del4 (pathogenic) | Not tested | 18.2 | No | N/A | No |

| 7 | 68 | F | BRCA2 p.E1035 (c.3103G>T and 3331 G>T) pathogenic | Not tested | 30.4 |

Yes (p.E1035) Yes |

N/A | Yes |

| 10 | 50 | F | BRCA1 Del Exons 2‐18 (pathogenic) | ATM Q445fs (pathogenic) | 16.5 | N/A | Yes | |

| 12 | 49 | F | BRCA1 ‐c.181T>G(p.Cys61Gly) (pathogenic) | BRCA1 C61G (pathogenic) | 9.7 | No | N/A | Yes |

Abbreviation: N/A, not applicable.

Discussion

In this study, we report the clinical outcome of the PARP inhibitor olaparib on individuals with metastatic, advanced PDAC. The response rate seen in this study of 23% approximates previous results reported in olaparib in germline BRCA1/2 patients with PDAC 6. The disease control rate of 54% at 16 weeks, along with the median OS of more than 16 months, in individuals with PDAC with DNA repair abnormalities is also encouraging, as this patient population usually has few treatment options available. PDAC remains a difficult disease to treat, but further molecular insights through germline and somatic testing have yielded possible avenues for therapeutic effects.

Of note in this study is the observation building upon prior reported data on the effect of certain mutations on the functional relationship of the given gene. In the example of the BRCA/PALB2 mutated genes, the effect of mutation of the RAD51 binding domain yielded a much higher OS, which was seen in another study of olaparib in patients with ovarian cancer 25. In that study, individuals with ovarian cancer who have BRCA2 mutations affecting the RAD51 binding domain had a significantly improved 5‐year survival compared with those that did not. Conversely, in our analysis, we did not see any benefit in either patient with PDAC with ATM mutations, one of which was pathogenic and one of which was VUS. ATM, which functions as a cell cycle checkpoint kinase and closely functions in conjunction with BRCA1, p53, and NBS1, among others, would theoretically yield a sensitivity to PARP inhibition. This has been seen preclinically in PDAC models 26 along with refractory ATM‐mutated prostate cancer 11. Of note is patient 12, who had a BRCA1 mutation in the RING domain, which drives E3 ubiquitin ligase activity for BRCA1, and is still alive 9.7+ months after initiating Olaparib. Because of our small sample size, it is unclear whether any observation is truly a clinical finding or a sampling error.

Our study also used available imaging and applied radiomics using QTA to look for correlative clinical outcomes. Previous radiomic efforts have demonstrated interesting relationships between the quantitative features extracted from imaging studies and tumor biology, genomics, and outcomes. In this study, we were interested to uncover any potentially useful imaging biomarkers that could correlate with patient outcomes. Given the noninvasive nature of radiomics compared with tissue sampling techniques, the discovery of imaging biomarkers are attractive because they could be used to provide both predictive and prognostic features that could be leveraged to optimize treatment outcomes with this class of drugs as well as to help risk stratify subjects in future trials. When QTA was applied to our patient population, several texture parameters emerged that were of interest. SD (spatial scaling factor = 0) of hepatic metastasis was found to be associated with overall survival. A greater SD value (more variation from the mean in signal intensities) of the hepatic metastasis is associated with longer OS. Lesions with higher pretreatment SD tend to demonstrate greater signal heterogeneity, which in turn may be a marker of intrachromosomally heterogeneity. Because liver metastasis is a poor prognostic feature in PDAC survival, it is not surprising to find a link between hepatic metastatic texture profiles and better OS. Furthermore, pancreatic lesions with higher (positive) skewness of their signal intensities tended to also remain on therapy longer than those subjects with lower (negative skewness) profiles. We hypothesize that positive skewness lesions have more pixel elements that are lower in HU than negative skewness lesions because of more areas of regional necrosis and less viable tumor. Finally, it is interesting to note that subjects with higher MPP texture features in their skeletal muscles are associated with longer OS times. Because MPP reflects the mean value of positive pixels within a region of interest, this finding may suggest that patients with higher MPP have sarcopenia. Such associations between sarcopenia measured on CT and outcomes has been noted before. We will be exploring this association further in the future.

This study does have limitations. The retrospective nature of the study is an issue. Furthermore, the absence of liquid biopsies including peripheral blood and prospectively collected tissue limits more insight to the responses (and lack thereof) seen. A recently published study examining cell‐free DNA in individuals with prostate cancer with a BRCA2 mutation showed a reversion of BRCA2 tumors to restore their BRCA function that led to the resistance of these patients to PARP inhibition 27. This type of analysis involving liquid biopsies is essential to future studies in understanding resistance mechanisms. Radiomics and liquid biopsy have advantages of being noninvasive and quantifiable and can be repeated to evaluate tumor progression. Radiomics help in correlating quantitative features with tissue pathology, whereas using liquid biopsies allow detecting molecular changes at low concentrations, sometimes even before clinical evidence of tumor progression. Absence of either complementary data reduces efficiency of detecting and treating cancer 20, 28, 29. Study limitations from lack of prospectively collected tissue also include inability to perform somatic testing or declare if the tumor had loss of heterozygosity or a second hit.

Finally, the QTA data are limited because of the small sample size. Unfortunately, not all subjects had pancreatic lesions remaining or had suitable metastatic lesions for analysis. Furthermore, the descriptive statistical analysis performed here was a first step to identify potentially useful radiomic biomarkers for further investigation. It was not meant to provide a comprehensive bioinformatic approach to validating these features as clinically useful imaging biomarkers at this time. Nevertheless, these results suggest that evaluation of our QTA imaging biomarkers would be warranted in future trials.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study shows that in individuals with advanced PDAC that harbors mutations in the DNA repair pathway, PARP inhibition should be considered as treatment. The clinical benefit seen even in those with prior platinum exposure warrants further clinical trial evaluations. Additional insights into resistance mechanisms should lead to considerations in modifications of PARP inhibition in addition to combination based approaches.

Author Contributions

Conception/design: Erkut Borazanci, Carol Guarnieri, Susan Haag, Courtney Snyder

Provision of study material or patients: Erkut Borazanci, Carol Guarnieri, Susan Haag, Courtney Snyder

Collection and/or assembly of data: Erkut Borazanci, Ronald Korn, Winnie S. Liang, Carol Guarnieri, Susan Haag, Courtney Snyder, Kristin Hendrickson, Lana Caldwell, Gayle Jameson

Data analysis and interpretation: Erkut Borazanci, Ronald Korn, Winnie S. Liang, Susan Haag

Manuscript writing: Erkut Borazanci, Ronald Korn, Winnie S. Liang, Carol Guarnieri, Susan Haag, Courtney Snyder, Kristin Hendrickson, Lana Caldwell, Dan Von Hoff

Final approval of manuscript: Erkut Borazanci, Ronald Korn, Winnie S. Liang, Carol Guarnieri, Susan Haag, Courtney Snyder, Kristin Hendrickson, Lana Caldwell, Dan Von Hoff

Disclosures

Erkut Borazanci: Fujifilm, Ipsen, Corcept (C/A), Teva, Biogen, Genzyme, Novartis (C/A‐spouse), Ipsen (speakers bureau), Teva, Biogen, Genzyme, Novartis, Genentech (Speaker's bureau‐spouse), Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Pharmacyclics, Idera, Daiichi Sankyo, Minneamrita Therapeutics, Ambry Genetics, Mabvax, Eli Lilly & Co, Samumed (RF); Ronald Korn: Imaging Endpoints (E); Dan Von Hoff: McKesson (E), McKesson, Medtronic, CerRx, SynDevRx, UnitedHealthcare, Anthem Inc, Capella Therapeutics, Stromatis Pharma, Systems Oncology, Cell Therapeutics (OI), DNAtrix, Esperance Pharmaceuticals, Five Prime Therapeutics, Imaging Endpoints, Immodulon Therapeutics, Insys Therapeutics, Medical Prognosis Institute, miRNA Therapeutics, Senhwa Biosciences, Tolero Pharmaceuticals, Trovagene, Alethia Biotherapeutics, Alpha Cancer technologies, Arvinas, Bellicum Pharmaceuticals, CanBas, Horizon Discovery, Innate Pharma, Lixte Biotechnology, Oncolyze, RenovoRx, TD2, AADi, Aptose Biosciences, BiolineRX, CV6 Therapeutics, EMD Serono, Evelo Therapeutics, Fujifilm, Histogen, Intezyne Technologies, Kalos Therapeutics, Kura, Pharmamab, Phosplatin Therapeutics, SOTIO, Strategia Therapeutics, SunBiopharma, Synergene, Systems Imagination, 7 Hills Pharma, Actininium Pharmaceuticals, Aduro Biotech, ARMO Biosciences, Cancer Prevention Pharmaceuticals, Defined Health, Geistlich Pharama, HUYA Bioscience International, Immunophotonics, Novocure, Vertex, ARIAD, Boston Biomedical, CORRONA, FORMA Therapeutics, Genzada Pharmaceuticals, L.E.A.F. Pharmaceuticals, Oncology Venture, Reflexion Medical, TP therapeutics, Verily, Athenex, Fate Therapeutics, Fibforgen, Jounce Therapeutics, Samus Therapeutics, Sumitomo Dainippon, Aeglea Biotherapeutics, 2X Oncology, Innokeys, Novita Pharmaceuticals, NuCana Biomed, Araxes Pharma, Ipsen, SciClone, TargaGenix, Trans Med, Veana Therapeutics, Biospecifics Technologies, Riptide Bioscience, Vicus Therapeutics, Codiak Biosciences, Decoy Biosystems, OSI Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly & Co, Agenus, Globe Life Science, Kelun‐ Klus Pharma, RadImmune, Samumed, SOBI, Adicet Bio, BioXCel therapeutics, Bryologyx, Celgen, Helix BioPharma, Sirnaomics (C/A), Eli Lilly & Co, Genentech, Celgene, Agios, Incyte, Merrimack, Plexxikon, Minneamrita Therapeutics, 3‐V Biosciences, Abbvie, Aduro Biotech, ArQule, Baxalta, Cleave Biosciences, CytRx Corporation, Daiichi Sankyo, Deciphera, Endocyte, Exelixis, Essa, Five Prime therapeutics, Gilead Sciences, Merck, miRNA therapeutics, Pfizer, Pharmacyclics, Phoenix Biotech, Proderm IQ, Samumed, Strategia, Trovagene, Verastem, Halozyme (RF); Gayle Jameson: Celgene (RF), Celgene, Ipsen (H). The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

Supporting information

See http://www.TheOncologist.com for supplemental material available online.

Supplemental Figures

Supplemental Tables

Disclosures of potential conflicts of interest may be found at the end of this article.

References

- 1. Borazanci E, Dang CV, Robey RW et al. Pancreatic cancer: “A riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma”. Clin Cancer Res 2017;23:1629–1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Domchek SM, Aghajanian C, Shapira‐Frommer R et al. Efficacy and safety of olaparib monotherapy in germline BRCA1/2 mutation carriers with advanced ovarian cancer and three or more lines of prior therapy. Gynecol Oncol 2016;140:199–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Robson M, Im SA, Senkus E et al. Olaparib for metastatic breast cancer in patients with a germline BRCA mutation. N Engl J Med 2017;377:523–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lowery MA, Kelsen DP, Capanu M et al. Phase II trial of veliparib in patients with previously treated BRCA‐mutated pancreas ductal adenocarcinoma. Eur J Cancer 2018;89:19–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Murai J, Huang SY, Das BB et al. Trapping of PARP1 and PARP2 by clinical PARP inhibitors. Cancer Res 2012;72:5588–5599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kaufman B, Shapira‐Frommer R, Schmutzler RK et al. Olaparib monotherapy in patients with advanced cancer and a germline BRCA1/2 mutation. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:244–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Economopoulou P, Mountzios G, Pavlidis N et al. Cancer of unknown primary origin in the genomic era: Elucidating the dark box of cancer. Cancer Treat Rev 2015;41:598–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Waddell N, Pajic M, Patch AM et al. Whole genomes redefine the mutational landscape of pancreatic cancer. Nature 2015;518:495–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Connor AA, Denroche RE, Jang GH et al. Association of distinct mutational signatures with correlates of increased immune activity in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. JAMA Oncol 2017;3:774–783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nik‐Zainal S, Davies H, Staaf J et al. Landscape of somatic mutations in 560 breast cancer whole genome sequences. Nature 2016;534:47–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mateo J, Carreira S, Sandhu S et al. DNA‐repair defects and olaparib in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2015;373:1697–1708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fong PC, Boss DS, Yap TA et al. Inhibition of poly(ADP‐ribose) polymerase in tumors from BRCA mutation carriers. N Engl J Med 2009;361:123–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lowery MA, Kelsen DP, Stadler ZK et al. An emerging entity: Pancreatic adenocarcinoma associated with a known BRCA mutation: Clinical descriptors, treatment implications, and future directions. The Oncologist 2011;16:1397–1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Golan T, Hammel P, Reni M et al. Maintenance olaparib for germline BRCA‐mutated metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med 2019. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Limkin EJ, Sun R, Dercle L et al. Promises and challenges for the implementation of computational medical imaging (radiomics) in oncology. Ann Oncol 2017;28:1191–1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yamamoto S, Maki DD, Korn RL et al. Radiogenomic analysis of breast cancer using MRI: A preliminary study to define the landscape. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2012;199:654–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jamshidi N, Jonasch E, Zapala M et al. The radiogenomic risk score: Construction of a prognostic quantitative, noninvasive image‐based molecular assay for renal cell carcinoma. Radiology 2015;277:114–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Weiss GJ, Ganeshan B, Miles KA et al. Noninvasive image texture analysis differentiates K‐ras mutation from pan‐wildtype NSCLC and is prognostic. PLoS One 2014;9:e100244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yamamoto S, Korn RL, Oklu R et al. ALK molecular phenotype in non‐small cell lung cancer: CT radiogenomic characterization. Radiology 2014;272:568–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Miles KA, Ganeshan B, Hayball MP. CT texture analysis using the filtration‐histogram method: What do the measurements mean? Cancer Imaging 2013;13:400–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Daly MB, Pilarski R, Berry M et al. NCCN Guidelines Insights: Genetic/Familial High‐Risk Assessment: Breast and ovarian. Version 2.2017. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2017;15:9–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Syngal S, Brand RE, Church JM et al. ACG clinical guideline: Genetic testing and management of hereditary gastrointestinal cancer syndromes. Am J Gastroenterol 2015;110:223–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Määttä KM, Nurminen R, Kankuri‐Tammilehto M et al. Germline EMSY sequence alterations in hereditary breast cancer and ovarian cancer families. BMC Cancer 2017;17:496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Inano S, Sato K, Katsuki Y et al. RFWD3‐mediated ubiquitination promotes timely removal of both RPA and RAD51 from DNA damage sites to facilitate homologous recombination. Mol Cell 2017;66:622–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Labidi‐Galy SI, Olivier T, Rodrigues M et al. Location of mutation in BRCA2 gene and survival in patients with ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2018;24:326–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Perkhofer L, Schmitt A, Romero‐Carrasco MC et al. ATM deficiency generating genomic instability sensitizes pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cells to therapy‐induced DNA damage. Cancer Res 2017;77:5576–5590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Quigley D, Alumkal JJ, Wyatt AW et al. Analysis of circulating cell‐free DNA identifies multiclonal heterogeneity of BRCA2 reversion mutations associated with resistance to PARP inhibitors. Cancer Discov 2017;7:999–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cohen JD, Li L, Wang Y et al. Detection and localization of surgically resectable cancers with a multi‐analyte blood test. Science 2018;359:926–930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Neri E, Del Re M, Paiar F et al. Radiomics and liquid biopsy in oncology: The holons of systems medicine. Insights Imaging 2018;9:915–924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

See http://www.TheOncologist.com for supplemental material available online.

Supplemental Figures

Supplemental Tables