Abstract

Background/Objective

Heart failure (HF) readmission rates have plateaued despite scrutiny of hospital discharge practices. Many HF patients are discharged to skilled nursing facility (SNF) after hospitalization before returning home. Home health care (HHC) services received during the additional transition from SNF to home may affect readmission risk. Here, we examined whether receipt of HHC affects readmission risk during the transition from SNF to home following HF hospitalization.

Design

Retrospective cohort study.

Setting

Fee-for-service Medicare data, 2012–2015.

Participants

Beneficiaries 65 and older hospitalized with HF who were subsequently discharged to SNF then discharged home.

Measurements

The primary outcome was unplanned readmission within 30 days of discharge to home from SNF. We compared time to readmission between those with and without HHC services using a Cox model.

Results

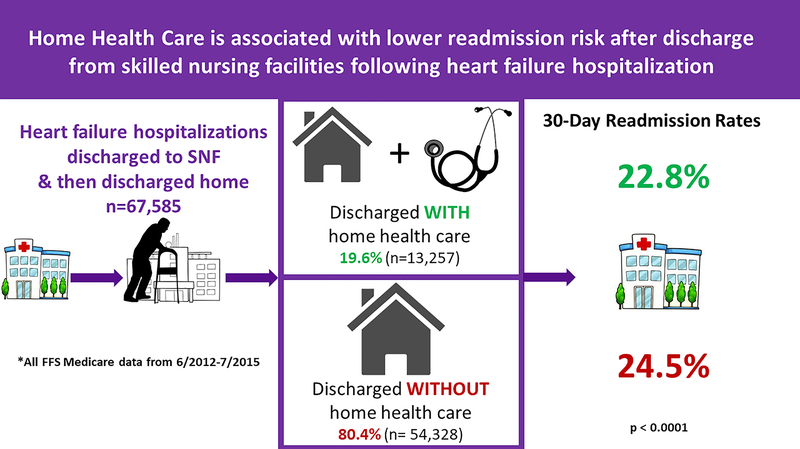

Of 67,585 HF hospitalizations discharged to SNF and subsequently discharged home; 13,257 (19.6%) were discharged with HHC, 54,328 (80.4%) without. Patients discharged home from SNF with HHC had lower 30-day readmission rates than patients discharged without HHC (22.8% vs 24.5%, p<0.0001) and a longer time to readmission. In adjusted model, hazard for readmission was 0.91 (0.86 – 0.95) with receipt of HHC.

Conclusions

Recipients of HHC were less likely to be readmitted within 30 days versus those discharged home without HHC. This is unexpected, as patients discharged with HHC likely have more functional impairments. Since patients requiring a SNF stay after hospital discharge may have additional needs, they may particularly benefit from restorative therapy through HHC; however only about 20% received such services.

Keywords: transitions, readmission, skilled nursing facility, rehabilitation, home health care, heart failure

Introduction

Interventions to improve post-hospital outcomes in patients with heart failure (HF) have traditionally focused on hospital discharge.1 Though skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) are often used to transition vulnerable patients from hospital to home, it is increasingly recognized that the additional transitions from hospital to SNF2 and then from SNF to home3–5 can affect readmission risk. As a result, in October 2018, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) rolled out the SNF Value-Based Purchasing (VBP) Program which offers incentive payments and penalties to SNFs paid under the SNF Prospective Payment System based on performance on 30-day readmission measures.6

Patients with HF may particularly benefit from increased attention to post-acute care transitions as HF readmission rates remain high7 despite many being discharged to SNF prior to returning home.8 Home health care (HHC) involves the provision of skilled services to patients for both acute and chronic care management and can be used as support both during the transition from hospital to home and from SNF to home. Early high intensity home care after HF hospitalization has previously been found to be associated with lower 30-day readmissions,9,10 while prior work has demonstrated that HHC is associated with reduced rates of readmission during the SNF to home transition in a safety net cohort.11

However, little is known about the utility of HHC in the transition from SNF to home after a HF hospitalization. Therefore, we examined the association between receipt of HHC after SNF discharge and readmission risk among a national cohort of Medicare patients discharged from SNF to home following HF hospitalization from 2012–2015.

Methods

Study sample and Data Sources

This was a retrospective cohort study of all Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries 65 and older discharged from July 2012 to June 2015 with a principal discharge diagnosis of HF, identified by methods adopted by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).12,13 Medicare Standard Analytic Files were used to identify admissions to acute care hospitals and skilled nursing facilities. These were merged with Medicare Denominator Files containing information on patient-level characteristics including date of birth, sex, and race.14 We excluded hospitalizations linked with SNF discharge dates more than 30 days after hospital discharge as the SNF VBP Program’s SNF 30-Day All-Cause Readmission Measure (SNFRM), measures the rate of all-cause, unplanned hospital readmissions for SNF residents within 30 days of discharge from a prior hospital stay.6 We also excluded admissions with less than one day in SNF and hospital admissions originating from SNF, as the latter represents long-term care patients.

Discharge with HHC may be confounded by quality of SNF care. To address this, we incorporated SNF-level characteristics via CMS’s SNF Quality Reporting Program from Nursing Home Compare. Nursing Home Compare is a website administered by CMS that allows comparison of quality of care at every Medicare-certified nursing home. The inaugural release of this data was published in October 2018 and consists of data from 2016–2018.

Primary Independent Variable of Interest:

The primary independent variable of interest was discharge from SNF to home with or without HHC.

Main Outcome Measure:

The primary outcome was days until any unplanned readmission following SNF to home discharge, censoring at 30 days; unplanned readmissions were defined using CMS’s HF readmission measure methodology.15

Covariates:

We used the SNFRM risk adjustment,16 including age, sex, whether the index hospitalization included intensive care unit (ICU) days, index hospital length of stay, and the number of acute care hospitalization days in the year prior to the index hospitalization. However, we did not use the SNFRM comorbidity variables as they are not condition specific; instead we used the 35 co-morbidities included in the Medicare HF readmission measure. Our model also accounted for additional patient-level variables: length of stay in SNF, Medicaid dual eligibility, race, and whether the patient had a SNF stay in the year prior to the index hospitalization.

We also accounted for SNF-level variables in our model: SNF ownership type, bed size of SNF, SNF overall rating, SNF quality measure rating, SNF staffing rating, physical therapist staffing hours per resident per day, adjusted total nurse staffing hours per resident per day, urban vs. rural setting, and geographic region. The SNF overall star rating incorporates health inspections, quality of resident care measures, and staffing data.17 The SNF quality measure rating incorporates information on physical and clinical measures for nursing home residents. The SNF staffing rating is based on registered nurse (RN) hours per resident per day and total staffing hours (RN, licensed practical nurse, nurse aide) per resident per day.18 Ratings range from 1–5, with 5 representing highest quality.

Statistical Analysis

We first compared those discharged home from SNF with and without HHC with descriptive statistics, testing for differences using χ2 and t-tests. Table 1 also includes a comparison of Elixhauser co-morbidity scores between these groups. Next, we plotted time to unplanned readmission with Kaplan-Meier curves and compared these groups with a log-rank test. Finally, we compared time to unplanned readmission using a multivariable Cox proportional hazards model that adjusted for all covariates. Variance inflation factor (VIF) was calculated to estimate multicollinearity for each predictor. A predictor of VIF > 2.5 was considered as an indicative of serious collinearity. This was observed with the “SNF RN staffing rating” and the “adjusted total nurse staffing hours per resident per day” variables; thus “SNF RN staffing rating” was excluded from the model. Planned readmissions as defined by Horwitz et al.12,19 and death were considered competing risks in this model and thus were censored. Patients were also censored at 30 days. This model included a random effect to account for correlation of patient outcome by SNF.20 We found that the variance of this effect for outcome by hospital was very small (0.01) and therefore we did not account for hospital effects in our model. A sensitivity analysis in which indicator for missing data in the Cox proportional hazards model was also conducted. Analyses were conducted using SAS (SAS Institute), version 9.4. The need to obtain informed consent was waived by the Yale Human Investigation Committee and the NYU School of Medicine Institutional Review Board; both provided approval for the overall study.

Table 1:

Characteristics of Those Discharged Home from SNF with and without Home Health Care

| Characteristic | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQRa) or Mean ± SDb; or N (%) | |||

| Age | 83.3 ± 7.9 | 83.3 ± 7.7 | 0.29 |

| Male | 21374 (39.3%) | 5012 (37.8%) | 0.001 |

| Race | |||

| Other | 1697 (3.1%) | 337 (2.5%) | <.0001 |

| White | 48358 (89.0%) | 11726 (88.5%) | |

| Black | 4273 (7.9%) | 1194 (9.0%) | |

| Length of stay in SNFc | 18.0 (11.0 – 23.0) | 15.0 (10.0 – 21.0) | <.0001 |

| Elixhauser comorbidity score | 22.0 (12.0 – 32.0) | 22.0 (12.0 – 32.0) | 0.32 |

| Dual eligible | 7497 (13.8%) | 1854 (14.0%) | 0.58 |

| Hospitalization in the past year | 36863 (67.9%) | 8814 (66.5%) | 0.002 |

| SNF utilization in the past year | 21530 (39.6%) | 4857 (36.6%) | <.0001 |

| ICUd stay during index hospitalization | 20360 (37.5%) | 4883 (36.8%) | 0.17 |

| Length of stay of index hospitalization | 7.50 (3.76) | 7.61 (4.46) | 0.01 |

| SNF ownership | |||

| Missing | 1413 (2.6%) | 1562 (11.8%) | <.0001 |

| For profit | 36474 (67.1%) | 6439 (48.6%) | |

| Government | 1621 (3.0%) | 517 (3.9%) | |

| Non profit | 14820 (27.3%) | 4739 (35.7%) | |

| SNF beds | |||

| Missing | 1413 (2.6%) | 1562 (11.8%) | <.0001 |

| 1–99 | 18221 (33.5%) | 5797 (43.7%) | |

| 100–199 | 29265 (53.9%) | 5010 (37.8%) | |

| 200–299 | 3988 (7.3%) | 646 (4.9%) | |

| 300–399 | 959 (1.8%) | 206 (1.6%) | |

| 400–499 | 217 (0.4%) | 18 (0.1%) | |

| 500+ | 265 (0.5%) | 18 (0.1%) | |

| SNF Overall rating | |||

| Missing | 1413 (2.6%) | 1562 (11.8%) | <.0001 |

| 1 | 3770 (6.9%) | 591 (4.5%) | |

| 2 | 9594 (17.7%) | 1420 (10.7%) | |

| 3 | 7971 (14.7%) | 1600 (12.1%) | |

| 4 | 12809 (23.6%) | 2698 (20.4%) | |

| 5 | 18771 (34.6%) | 5386 (40.6%) | |

| Location | |||

| Missing | 1509 (2.8%) | 1628 (12.3%) | <.0001 |

| Urban | 47214 (86.9%) | 10311 (77.8%) | |

| Rural | 5605 (10.3%) | 1318 (9.9%) | |

| Region | |||

| Missing | 1416 (2.6%) | 1562 (11.8%) | <.0001 |

| New england | 6085 (11.2%) | 1045 (7.9%) | |

| Middle atlantic | 9492 (17.5%) | 1482 (11.2%) | |

| East north central | 10693 (19.7%) | 1844 (13.9%) | |

| West north central | 3549 (6.5%) | 734 (5.5%) | |

| South atlantic | 10155 (18.7%) | 2687 (20.3%) | |

| East south central | 2746 (5.1%) | 1403 (10.6%) | |

| West south central | 3184 (5.9%) | 1056 (8.0%) | |

| Mountain | 1937 (3.6%) | 541 (4.1%) | |

| Pacific | 5071 (9.3%) | 903 (6.8%) | |

IQR =Interquartile Range

Standard Deviation

SNF: Skilled Nursing Facility

Additional patient- and SNF-level characteristics listed in Supplementary Table S1

Results

Of 155,440 hospitalizations associated with SNF discharge dates documented in Medicare Part A, 67,585 HF hospitalizations were discharged to SNF and subsequently discharged home; 13,257 (19.6%) were discharged with HHC, 54,328 (80.4%) without. Figure 1 delineates the cohort selection. Patients discharged with HHC were more likely to be female, black and have a shorter SNF length of stay compared to those discharged without HHC. Several co-morbidities were different between groups as well, including vascular/circulatory disease, renal failure, acute coronary syndrome, major psychiatric disorders, liver/biliary disease, stroke, dementia, other psychiatric disorders, fibrosis of lung, and depression (Supplementary Table S1). Bivariate analysis also demonstrated that those discharged with HHC were more likely to be discharged from a SNF that was a non-profit, with a higher overall rating (Table 1), higher SNF staffing rating, higher SNF nurse staffing rating, but lower SNF quality measure rating. Patients discharged with HHC were also more likely to be discharged from a SNF with more physical therapist staffing hours per resident per day and higher adjusted total nurse staffing hours per resident per day (Supplementary Table S1).

Figure 1:

Flow chart for cohort selection

Among the overall study cohort, 16,333 (24.2%) were readmitted within 30 days of SNF discharge. Patients discharged home from SNF with HHC had lower crude 30-day readmission rates than patients discharged without HHC (22.8% [95% CI; 22.1–23.5%;] vs 24.5% [95% CI; 24.1–24.9%;], p<0.0001, Figure 2). Supplementary Figure S3 illustrates unadjusted time to readmission between these groups, and shows that patients discharged home from SNF with HHC have a longer time to readmission (p<0.0001). Median time to readmission for those readmitted within 30 days after discharge home from SNF with HHC was 11 days (IQR; 5–19) and 9 days (IQR; 3–18) for those discharged home without HHC (p<0.0001). Mortality without readmission within 30 days was also lower in those discharged with HHC compared to those discharged without HHC (3.1% [95% CI; 2.83–3.43] vs 4.1% [95% CI; 3.93–4.27], p<0.0001).

Figure 2:

Patients discharged home from SNF with HHC had lower crude 30-day readmission rates than patients discharged without HHC. FFS, fee-for-Service; SNF, skilled nursing facility.

After risk-adjustment, patients discharged home with HHC still had a lower hazard of 30-day readmission (HR 0.91 [95% CI; 0.86–0.95]. Table 2 outlines the hazard ratios for the SNF-level variables in the model. Supplementary Table S2 lists the hazard ratios for all the variables in the model. This finding that patients discharged home with HHC had a lower hazard of 30-day readmission was consistent in our sensitivity analysis, which included an indicator for missing data in the Cox proportional hazards model (HR 0.90 [95% CI; 0.87–0.94]).

Table 2:

Multivariable analysis examining effect of home care on readmission after discharge from SNF to home following HF hospitalization: selected SNF-level predictors

| Characteristic | p-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Home Health Care | 0.91 (0.86 – 0.95) | <.0001 |

| SNFb ownership | ||

| For profit | reference | |

| Government | 0.95 (0.86 – 1.05) | 0.003 |

| Non profit | 0.93 (0.89 – 0.97) | |

| SNF beds | ||

| 1–99 | reference | |

| 100–199 | 0.98 (0.94 – 1.02) | 0.48 |

| 200–299 | 0.999 (0.93 – 1.08) | |

| 300–399 | 1.02 (0.89 – 1.17) | |

| 400–499 | 1.13 (0.86 – 1.50) | |

| 500+ | 1.22 (0.95 – 1.56) | |

| SNF Overall Rating | ||

| 1 | reference | |

| 2 | 0.95 (0.87 – 1.03) | 0.08 |

| 3 | 0.92 (0.84 – 0.99) | |

| 4 | 0.91 (0.84 – 0.99) | |

| 5 | 0.89 (0.82 – 0.98) | |

| Location | ||

| Urban | reference | |

| Rural | 0.97 (0.92 – 1.03) | 0.31 |

| Region | ||

| New England | reference | |

| Middle Atlantic | 1.02 (0.95 – 1.10) | <.0001 |

| East North Central | 1.10 (1.03 – 1.18) | |

| West North Central | 1.06 (0.97 – 1.16) | |

| South Atlantic | 1.15 (1.07 – 1.23) | |

| East South Central | 1.12 (1.02 – 1.22) | |

| West South Central | 1.05 (0.96 – 1.15) | |

| Mountain | 0.90 (0.81 – 1.01) | |

| Pacific | 1.03 (0.95 – 1.12) |

CI: Confidence Interval

SNF: Skilled Nursing Facility

Model also controlled for age, sex, race, length of stay in SNF, Medicaid dual-eligibility, number of acute care hospitalization days in year prior to index hospitalization, SNF utilization in the year prior to index hospitalization, whether the index hospitalization included intensive care unit days, index hospital length of stay, the 35 comorbidities included in the Medicare HF readmission measure, SNF size (number of beds), SNF Quality Measure rating, SNF Staffing rating, physical therapist staffing hours per resident per day, andadjusted total nurse staffing hours per resident per day. See Supplementary Table S2 for full model.

Discussion

Our study of all Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries hospitalized for HF discharged to SNF and subsequently discharged home found that patients who received HHC on discharge were less likely to be readmitted within 30 days than those discharged home without HHC. This is unexpected, as patients discharged with HHC are likely to have more functional impairments21 and had shorter SNF stays. The latter is a particularly salient finding as patients with shorter SNF stays theoretically may be at higher risk for readmission22 because they are fewer days out from hospital discharge and consequently may be less recovered from their acute illness than those with longer SNF stays.

Under the Medicare SNF VBP program, nearly 11,000 SNFs will be penalized in Fiscal Year 2019 based on performance on 30-day readmission measures.23,24 Despite our finding that patients discharged with HHC experienced decreased risk of readmission, only 20% were discharged with these services. This may represent “low hanging fruit” for SNFs searching for strategies to reduce readmissions and improve their performance in this program.

It is unclear why so few patients were discharged from SNF with HHC. Our bivariate analysis demonstrated that SNF-level characteristics appeared to be different in those discharged with HHC versus without (Table 1). However, given the disparate level of missing data (11.8–12.6% in the with HHC group compared to 2.6%−3.2% in the without HHC group), we are cautious in drawing generalizations. We speculate that SNFs in integrated health systems or with financial relationships with local HHC agencies may be more likely to discharge their patients with HHC. SNFs location in areas of high HHC agency density, such as those in urban settings, may also play a role.

In Medicare data, HHC classification includes skilled services from nurses, physical therapists, occupational therapists and/or speech-language pathologists. Regardless, we find benefit of HHC services in general after SNF discharge for HF patients which appears consistent with aforementioned work examining HHC during the SNF-to-home transition in other patient populations11 and other research evaluating the utility of home based transitional care after HF hospital discharge,25 such as home nursing visits within randomized controlled trial settings,9 and early intensive HHC combined with physician follow up within 7 days.10 On the other hand, another study demonstrated that patients discharged from HF hospitalization with HHC referral had a higher risk of 30-day readmission; however the authors acknowledge that this finding is likely explained by selection bias in that those receiving HHC are more likely to have more advanced illness.26 Patients discharged to SNF after hospitalization not only have functional impairments but are likely to be medically complex8 and have social complexity requiring additional caregiver support--- all of which may benefit from HHC.

Prior work has indicated that SNF stays may also be protective against readmission.27 Avoiding “post-hospital syndrome”28 in patients with HF may require SNF care and then HHC after discharge home as they are vulnerable to swift decline if recommended treatment is not followed. The additional skilled support afforded by HHC could, for instance, increase adherence to medications,29 dietary recommendations30 and other discharge instructions. However, given the broad range of what HHC can entail, the specific mechanisms through which HHC may lower readmission risk need to be elucidated.25 Further work should prospectively evaluate patients enrolled in HHC to examine patient level-factors such as disease acuity, cognitive impairment, physical functioning, and symptomology measured through structured assessments such as those found in MDS and OASIS data,31 in order to help providers identify which patients may most benefit from HHC and tailor the type of HHC required.

Strengths and Limitations

Our study is the first to characterize use of HHC in the transition from SNF to home after HF hospitalization using a national dataset. Most HF patients are over 65,32 making this group a high priority for Medicare. However, our study is limited by its observational design, which precludes causal inferences. Additionally, we did not have MDS or OASIS assessments and thus could not account for disease severity or patient function. As a result patients who select for HHC may differ systematically from those who do not. However, this is likely to be a conservative bias since HHC referral should be more common for those with greater functional needs and readmission risk. We also did not include Medicare Advantage patients in this study; however while the SNF VBP program applies to all Medicare fee-for-service patients, this is optional for other payors, including Medicare Advantage. Finally, while we accounted for SNF quality of care in our study, this data is from 2016–2018 (the only data available), and thus may not exactly reflect SNF quality of care from 2012–2015.

Conclusion

Use of SNF care has been increasing for the past decade,33 placing an increased number of patients at risk of readmission after discharge to home from SNF. Although we found that following a HF hospitalization, patients discharged from SNF to home with HHC are at decreased risk of readmission, only about 20% of discharges received such services. Increasing use of HHC services after SNF discharge may help reduce readmission risk. Since patients requiring a SNF stay after hospital discharge are likely to be functionally impaired with caregiving needs, this patient population overall may especially need restorative therapy through HHC.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure S3: Kaplan-Meier curve depicting time to readmission after discharge from SNF to home following HF hospitalization.

Acknolwedgements

Financial Disclosure: This work was supported by research grants R01HS022882 (Dr. Horwitz, Dr. Li, Dr. Bao, Dr. Herrin, Dr. Ross) from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; the NYU CTSA grant KL2TR001446 (Dr. Weerahandi) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, and K23 HL145110 (Dr. Weerahandi) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health.

Sponsor’s Role: The sponsors had no role in design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or preparation, review or approval of the manuscript.

Abbreviations used:

- HF

heart failure

- SNF

skilled nursing facility

- VBP

Value-Based Purchasing

- SNFRM

Skilled Nursing Facility Readmission Measure

- HHC

home health care

- RN

registered nurse

- CMS

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

- VIF

Variance inflation factor

Footnotes

Prior Presentations: We presented an earlier version of the manuscript as a poster at the Translational Science 2019 conference in Washington, D.C and as an oral presentation at the Society of General Internal Medicine 2019 conference in Washington D.C.

Conflict of Interest: To the best of our knowledge, no conflict of interest, financial or other, exists.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures:

In the past 36 months, Dr. Ross has received support through Yale University from the Food and Drug Administration as part of the Centers for Excellence in Regulatory Science and Innovation (CERSI) program, from Medtronic, Inc. and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to develop methods for postmarket surveillance of medical devices, from Johnson and Johnson to develop methods of clinical trial data sharing, from the Centers of Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to develop and maintain performance measures that are used for public reporting, from the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association to better understand medical technology evaluation, from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), and from the Laura and John Arnold Foundation to support the Collaboration on Research Integrity and Transparency (CRIT) at Yale. At the time this research was conducted, Dr. Horwitz, Dr. Dharmarajan, Dr. Bao, Dr. Herrin, and Dr. Ross worked under contract with CMS to develop and maintain performance measures. Dr. Dharmarajan was also a consultant and scientific advisory board member of Clover Health.

References

- 1.Ziaeian B, Fonarow GC. The prevention of hospital readmissions in heart failure. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2016;58(4):379–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mor V, Intrator O, Feng Z, Grabowski DC. The revolving door of rehospitalization from skilled nursing facilities. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(1):57–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carnahan JL, Unroe KT, Torke AM. Hospital readmission penalties: Coming soon to a nursing home near you! J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(3):614–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Toles M, Anderson RA, Massing M, et al. Restarting the cycle: Incidence and predictors of first acute care use after nursing home discharge. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(1):79–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weerahandi H, Li L, Bao H, et al. Risk of readmission after discharge from skilled nursing facilities following heart failure hospitalization: A retrospective cohort study. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2019;20(4):432–437. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.01.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid. The skilled nursing facility value-based purchasing program (SNFVBP). https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/Other-VBPs/SNF-VBP.html. Updated 2017.

- 7.Data.Medicare.Gov. Unplanned hospital visits - national. https://data.medicare.gov/Hospital-Compare/Unplanned-Hospital-Visits-National/cvcs-xecj. Updated 2019. Accessed 07/17, 2019.

- 8.Allen LA, Hernandez AF, Peterson ED, et al. Discharge to a skilled nursing facility and subsequent clinical outcomes among older patients hospitalized for heart failure. Circulation.Heart failure. 2011;4(3):293–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feltner C, Jones CD, Cene CW, et al. Transitional care interventions to prevent readmissions for persons with heart failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(11):774–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murtaugh CM, Deb P, Zhu C, et al. Reducing readmissions among heart failure patients discharged to home health care: Effectiveness of early and intensive nursing services and early physician follow-up. Health Serv Res. 2017;52(4):1445–1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carnahan JL, Slaven JE, Callahan CM, Tu W, Torke AM. Transitions from skilled nursing facility to home: The relationship of early outpatient care to hospital readmission. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2017;18(10):853–859. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2017.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horwitz LI, Grady JN, Cohen D, et al. Development and validation of an algorithm to identify planned readmissions from claims data. Journal of hospital medicine. 2015;10(10):670–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keenan PS, Normand ST, Lin Z, et al. An administrative claims measure suitable for profiling hospital performance on the basis of 30-day all-cause readmission rates among patients with heart FailureCLINICAL PERSPECTIVE. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2008;1(1):29–37. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.802686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Virnig B, Parsons H. Strengths and limitations of CMS administrative data in research.. Updated 20182019.

- 15.Keenan PS, Normand SL, Lin Z, et al. An administrative claims measure suitable for profiling hospital performance on the basis of 30-day all-cause readmission rates among patients with heart failure. Circulation.Cardiovascular quality and outcomes. 2008;1(1):29–37. Accessed 16 November 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.RTI International. Skilled nursing facility readmission measure (SNFRM) NQF #2510: All-cause risk-standardized readmission measure.. 2017;RTI Project Number 0214077.001.002.002.001.

- 17.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Design for nursing home compare five-star quality rating system: July 2018.. 2018.

- 18.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Five-star quality rating system. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/provider-enrollment-and-certification/certificationandcomplianc/fsqrs.html. Updated 2019.

- 19.Dorsey K, Grady JN, Desai N, et al. 2016. condition-specific measures updates and specifications report: Hospital-level 30-day risk-standardized readmission measures; acute myocardial infarction – version 9.0, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease – version 5.0, heart failure – version 9.0, pneumonia – version 9.0, and stroke – version 5.0. 2016.. 2016.

- 20.Hougaard P. Frailty models for survival data. Lifetime Data Anal. 1995;1(3):255–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones CD, Wald HL, Boxer RS, et al. Characteristics associated with home health care referrals at hospital discharge: Results from the 2012 national inpatient sample. Health Serv Res. 2017;52(2):879–894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dharmarajan K, Hsieh AF, Kulkarni VT, et al. Trajectories of risk after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia: Retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2015;350. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.SNF VBP facility-level dataset. https://data.medicare.gov/Nursing-Home-Compare/SNF-VBP-Facility-Level-Dataset/284v-j9fz. Updated 2019.

- 24.Rau J. Medicare cuts payments to nursing homes whose patients keep ending up in hospital. Kaiser Health News. December 3, 2018. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones CD, Bowles KH, Richard A, Boxer RS, Masoudi FA. High-value home health care for patients with heart failure. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2017;10(5). doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.117.003676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arundel C, Sheriff H, Bearden DM, et al. Discharge home health services referral and 30-day all-cause readmission in older adults with heart failure. Archives of medical science : AMS. 2018;14(5):995–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Werner RM, Coe NB, Qi M, Konetzka RT. Patient outcomes after hospital discharge to home with home health care vs to a skilled nursing facility.. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krumholz HM. Post-hospital syndrome — an acquired, transient condition of generalized risk. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(2):100–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwartz JK, Smith RO. Integration of medication management into occupational therapy practice. AJOT. 2017;71(4):7104360010p1–7104360010p7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suter PM, Gorski LA, Hennessey B, Suter WN. Best practices for heart failure: A focused review. Home Healthcare Now. 2012;30(7). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burke RE, Hess E, Barón AE, Levy C, Donzé JD. Predicting potential adverse events during a skilled nursing facility stay: A skilled nursing facility prognosis score. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(5):930–936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dariush M, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al. Heart disease and stroke Statistics–2016 update. Circulation. 2016;133(4):e38–e360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tyler DA, Feng Z, Leland NE, Gozalo P, Intrator O, Mor V. Trends in postacute care and staffing in US nursing homes, 2001–2010. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2013;14(11): 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure S3: Kaplan-Meier curve depicting time to readmission after discharge from SNF to home following HF hospitalization.