Abstract

Objective

Consistent with a national and global trend, prevalence estimates of autism have risen steadily in Quebec, causing concerns regarding quality and availability of diagnostic and intervention services as well as policies guiding service delivery and their efficacy. We conducted an analysis of Quebec’s autism policies to determine recent advances, challenges and gaps in the planning and delivery of provincial autism services.

Methods

We identify autism policy priorities in Quebec through a comprehensive review and a thematic analysis of past and present policies, consider their compliance with national and international human rights and health frameworks and identify policy gaps.

Results

Autism policies articulated at a provincial level in Quebec are comprehensive, well grounded in international and national frameworks and considerate of existing barriers in the systems. Quebec policies reflect long-standing recognition of many barriers affecting service utilization and quality. Root cause of challenges currently confronting the policy environment in Quebec includes limitations in: specific measures to enhance a person-centred approach across the lifespan, evaluation of economic costs associated with autism, utilization of research evidence, and enactment of policies.

Conclusion

Early intervention services, building capacity in existing resources through training programs, and integrating research through research translation initiatives can help the Québec government improve the quality and efficacy of services while reducing long-term costs to the systems and promoting quality of life for individuals with autism and their families.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.17269/s41997-019-00202-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Autism, Policy, Services, Québec

Résumé

Objectif

En accord avec la tendance nationale et internationale, le taux de prévalence de l’autisme a augmenté de façon continue au Québec, suscitant des inquiétudes concernant la qualité et la disponibilité des services de diagnostic et d’intervention, ainsi que l’efficacité des politiques de prestation. On propose une analyse des politiques en matière d’autisme afin de déterminer les récentes avancées, défis, et failles dans la planification et la prestation des services et soins en autisme au Québec.

Méthode

Nous identifions les priorités des politiques en autisme au Québec à partir d’une revue exhaustive et une analyse de contenu thématique des politiques passées et présentes, tout en examinant leur conformité aux normes nationales et internationales en matière de santé et de droits de l’homme ainsi que leurs failles.

Résultats

Les politiques en autisme au Québec sont exhaustives, bien ancrées dans les cadres internationaux et nationaux, et reflètent une reconnaissance accrue des difficultés affectant l’utilisation des services en matière d’autisme et leur qualité. Notre analyse révèle cependant plusieurs limites liées spécifiquement à l’absence d’une approche centrée sur la personne et d’une analyse des coûts. Les politiques actuelles nécessitent également une base fondée sur les données probantes et une mise en application plus efficace.

Conclusion

L’amélioration des services en autisme au Québec nécessite des actions concrètes de la part du gouvernement, y compris la multiplication des services d’intervention précoce, le renforcement des institutions existantes en assurant le développement de la capacité par la formation, et l’intégration de la recherche à travers les initiatives de transfert des connaissances. Ces actions permettent une meilleure efficacité des services, tout en réduisant les coûts à long terme pour le système et améliorant la qualité de vie pour les individus atteints et leurs familles.

Mots-clés: Autisme, Politiques, Services, Québec

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (henceforth autism) affects around 1 to 2% of children worldwide (Elsabbagh et al. 2012). In 2013, epidemiological data estimated the global prevalence to be 1 person in every 160 individuals, accounting for more than 7.6 million disability-adjusted life years and 0.3% of the global burden of disease (World Health Organization 2013). Increasing prevalence rates have brought attention to the condition from policy makers across the globe. A comprehensive action plan was therefore developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2013, highlighting the need to expand access to treatments for autism and related developmental conditions (World Health Organization 2013).

In Canada, public debates about autism policy have been particularly acrimonious, with parents resorting to legal action against provincial governments to secure services for their children under intense media scrutiny (Greschner and Lewis 2003; Shepherd and Waddell 2015; Manfredi and Maioni 2005). Consistent with Canadian federalism, each provincial health authority has responded by developing its own approach to funding and expanding autism services. These approaches were marked by interprovincial differences and continuing service shortfalls, further to which parents started calling for a national autism strategy supported by the Senate of Canada (Eggleton and Keon 2007). As a result, the federal government has appointed a group of experts to develop a business plan for a ‘Canadian Autism Partnership’ model that will address autism research, early detection, diagnosis and intervention, among other issues (CASDA 2016). However, a cohesive national strategy has not yet been developed.

Consistent with a national and global trend, prevalence estimates have risen steadily in Quebec from 15/10,000 in 2001 to 122/10,000 in 2015 (Diallo et al. 2017). Reasons for apparent rise include, among others, a greater awareness of the condition and improved access to services (Elsabbagh et al. 2012). The increased number of those affected has also rapidly increased the number of referrals to diagnostic and intervention services for autism in Quebec, causing concerns regarding availability and quality of these services and the policies governing them.

In response, a new action plan was recently announced by the Quebec Government, based on the following guiding principles: primacy of needs, proximity of services, a network of integrated services, and the collective responsibility of promoting social participation of persons with autism (MSSS 2017a). The 2017 Action Plan is, to date, the most comprehensive with regard to the objectives and the measures to be developed in Quebec. The plan proposes concrete actions in eight key areas (see Appendix A) where the Ministry of Health and Social Services and its local institutions plan to take action in order to improve the outcome for persons with autism and their families.

A main focus of the plan is reducing long wait times to access services that have persistently led to questions about the efficacy of previous policies. This challenge arises at different levels spanning intensive behaviour intervention programs for children under the age of 5, to specialized housing for autistic adults, and respite care for families. Relative to previous policies, the Action Plan promises to address the full spectrum of needs for people of all ages by introducing a wide range of services for adults to help them lead a more fulfilling life.

Going forward, implementation of policies proposed in the plan is dependent on several factors, including willingness of service providers to act, availability of infrastructure supports, and accountability mechanisms. Moreover, there is uncertainty in the extent to which implementation of the plan will utilize the significant amount of evidence to inform decisions about structures, systems and interventions for this population (McDonald and Machalicek 2013; Howlin et al. 2009; Warren et al. 2011). The uncertainty stems from the currently limited communication between research and policymaking, where research evidence that could inform policymaking and implementation is often kept within academia (Elsabbagh et al. 2014). Similarly, policies and action plans that guide implementation are often unknown to academia, and therefore, a bidirectional gap exists between research knowledge and policy (Contandriopoulos et al. 2017).

A critical understanding of the policy process is crucial to contemporary public health practice. Indeed, policies can shape the conditions in which people live and thus may have an impact on health and health equity. This is valid for policies, programs and regulations implemented within and outside the health sector. The concept of building ‘Healthy Public Policy’ (Hancock 1985) reflects the considerable power of economic and environmental policies, to act on the broader structural and social determinants of health. As related to autism, early intervention programs have the potential to positively affect critical development period, which leads to long life impacts. Moreover, policies offering family supports across the lifespan of an affected person impact the family mental health and their ability to contribute to society (e.g., employment, productivity, etc.).

Against this background, the aim of the current manuscript is to identify policy priorities in Quebec through a comprehensive review and a thematic analysis of past and present policies. For this aim, we undertook a qualitative evidence synthesis informed by Thomas and Harden’s (2008) synthesis methodology (MSSS 2012a). This method allows us to compare descriptive themes across reviewers and discuss them to develop ‘analytical themes’, with the aim to ‘go beyond’ the original data and provide new insights related to the review question (Thomas and Harden 2008). The selection of this framework is justified by the fact that our research team has multiple backgrounds, perspectives and critical views to provide into the analytical themes and the review question.

Our proposed policy analysis framework also includes consideration of research evidence use in these policies, as well as their compliance with national and international human rights and health frameworks. In identifying and analyzing provincial policy priorities, we will also pinpoint facilitators and barriers to the implementation of the most recent Quebec autism plan, as well as propose strategies to enhance bidirectional communication between research and policy, with the long-term goal of improving quality of life for people with autism and their families.

Methods

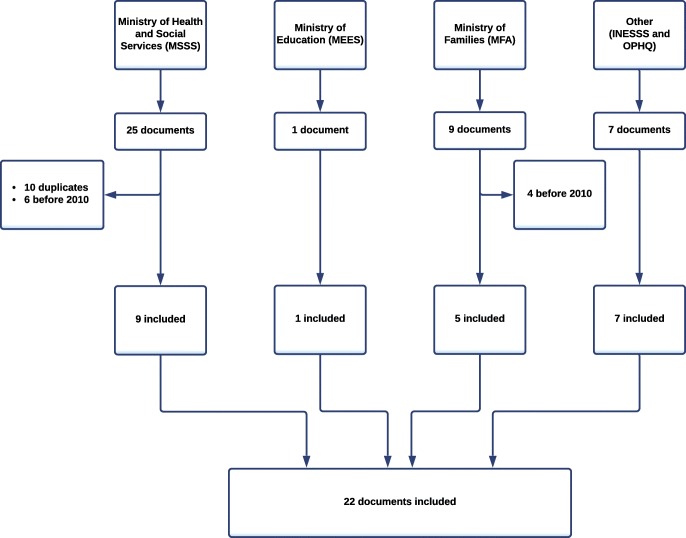

We conducted a comprehensive review of autism-related policies and guidelines issued by the government of Quebec between 2010 and 2018. The following inclusion criteria were used: policy documents or reports with any information on autism spectrum disorder or pervasive developmental disorder; reports created by provincial government in Quebec; documents published from January 2010 to January 2018; documents that are freely available to the general public. A variety of policy documents such as action plans, reports and program evaluation studies were identified, demonstrating the multi-faceted nature of autism-related policies. A flowchart describing the selection process is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of document selection

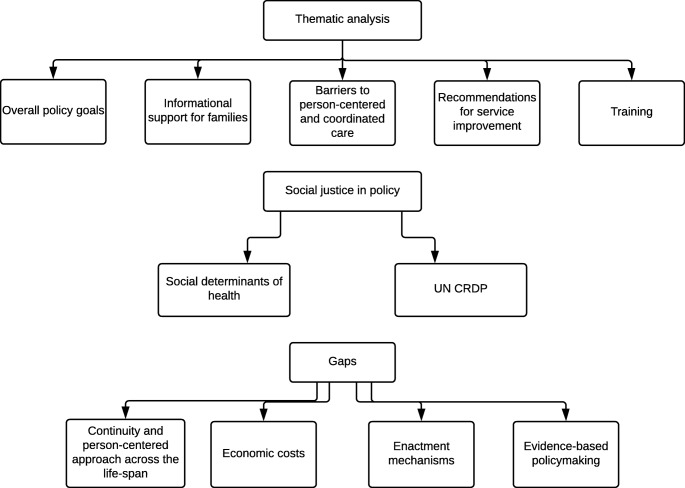

We extracted from the policy documents key information including, among others, the title, the provincial government body, the date of publication and implementation mechanisms associated with each policy. We then conducted a thematic analysis (Reviews, U.o.Y.C.f. and Dissemination 2009; Oliver et al. 2005) of these documents, following an initial structured analytical framework informed by Thomas and Harden (2008) (Thomas and Harden 2008) and the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre (EPPI-centre) approach for analysis of mixed-methods evidence (EPPI-Centre 2007). This approach allows for analyzing a variety of policy documents in relation to national and international frameworks, namely the United Nations Convention of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UN CRPD) (Rasmussen and Lewis 2007), and the social determinants of health specific to Canada (Mikkonen and Raphael 2010).

A flowchart describing the thematic analysis framework is provided in Fig. 2. Through this policy framework analysis, our aim was to identify policy processes supporting services for children with autism and possible gaps across existing policies, especially in view of the most recent plan.

Fig. 2.

Thematic analysis and analytical framework analysis

Results

Thematic analysis

Twenty-two documents were identified and included in the framework analysis based on the selection criteria outlined above. These documents are listed in Table 1. A summary description of the primary objectives identified across all policy documents is presented in Appendix Exhibit B1.

Table 1.

Policy documents identified in the review

| Policy document | Year |

|---|---|

| Guide of aid programmes for persons with disability: financial, equipment and supply aid (OPHQ 2011a). | 2011 |

| Guide for the support needs of families: for parents of a child or adult with a disability (OPHQ 2011c). | 2011 |

| Guide for the support needs of families: for parents of a child or adult with a disability—second part—practical information (OPHQ 2011b). | 2011 |

| 2008–2011 Report and Perspectives: Hope for the future: the services for persons with pervasive developmental disorder, their families and those close to them (MSSS 2012b). | 2012 |

| Evaluation of implementation of the access plan of services for persons with a disability 2008–2011 (MSSS 2012a). | 2012 |

| Autonomy for all: white paper on the creation of autonomy insurance (Quebec, G.o. 2013). | 2013 |

| National guide: financial assistance program for persons with disabilities (MELS 2014). | 2014 |

| Effectiveness of interventions for rehabilitation and pharmaceutical treatment for children 2–12 with autism spectrum disorder (Mercier 2014). | 2014 |

| Action Plan 2012–2015 from the Ministry of Families for persons with disabilities (MFA 2014). | 2014 |

| Together against bullying, a shared responsibility: concerted action plan to prevent and counter bullying 2015–2018 (MFA 2015). | 2015 |

| Annual report 2014–2015: Action Plan 2011–2014 from the Ministry of Health and Social Services for persons with disabilities (MSSS 2015a). | 2015 |

| Action plan from the Ministry of Health and Social Services. Service access, continuity and complementarity for young people (0–18 years old) with an intellectual disability or an autism spectrum disorder (MSSS 2015b). | 2015 |

| Main support measures in favour of families and children. Appendix to the 2010–2015 report on the achievements in favour of children and families (MFA 2016a). | 2016 |

| Report on the ministry’s directions regarding intellectual disabilities and structural actions for the ‘programmes-services’ in intellectual disabilities and autism spectrum disorders (MSSS 2016). | 2016 |

| Annual report 2015–2016: Action Plan 2015–2018 from the Ministry of Families for persons with disabilities (MFA 2016b). | 2016 |

| Annual report 2016–2017: Action Plan 2015–2018 from the Ministry of Families for persons with disabilities (MFA 2017). | 2017 |

| 2017–2022 Action Plan: structural actions for persons with autism spectrum disorder and their families (MSSS 2017a). | 2017 |

| Towards a better integration of treatments and services for persons with disabilities: framework for service organisation for physical and intellectual disabilities and autism spectrum disorders (MSSS 2017b). | 2017 |

| Evaluation of the integration of services for persons with physical or intellectual disabilities or autism spectrum disorder (PD, ID-ASD) (MSSS 2017c). | 2017 |

| Program guide for persons with disabilities, their families and their relatives (OPHQ 2017b). | 2017 |

| Federal and provincial fiscal measures guide for persons with disabilities and their families (OPHQ 2017a). | 2017 |

| Educational pathways guide for parents of a child with disabilities (OPHQ 2017c). | 2017 |

Informational support for families and caregivers

Several existing services related to early identification and intervention of autism in Quebec were described across documents. The information on these services was generally targeted to care providers or to the families of children with autism. For the service providers, information included recommendations for care provisions, description of specialized training for professionals, and discussion of barriers to early identification and intervention for autism. Analysis of policy documents also revealed an intent to increase family awareness of resources and financial supports available to them, e.g., financial assistance programs for families living with a disabled person (MELS 2014; OPHQ 2011a, 2017a; MFA 2016a). Other policy documents provide parents with information about clinical services and resources (OPHQ 2011b) and educational and support programs available to them (OPHQ 2017b, c).

Some policies aim to improve safety and well-being of children with autism by providing information about their rights and relevant support services and programs, e.g., dealing with bullying (MFA 2015). Other specific guidelines are intended to inform families about fair sharing of responsibilities in order to promote gender equality (MFA 2016a).

Barriers to person-centred and coordinated care

To ensure comprehensive services for all, the documents discussed some of the barriers to person-centred and coordinated care, hallmarks of service quality in Quebec. Examples of these barriers include:

inadequacy of existing services in meeting diverse needs of children with autism and their families (MSSS 2012b; Mercier 2014);

lack of services tailored for specific subgroups, e.g., people with Asperger’s syndrome or those with autism and a co-morbid intellectual disability (MSSS 2012b);

limitations of some standardized measures widely used in practice in accurately evaluating strengths and needs of affected persons;

limited access to family doctors and medical and rehabilitation specialists (speech therapists, occupational therapists and psychologists) (MSSS 2016);

absence of mechanisms to ensure continuity and complementarity of services (MSSS 2012b, 2015b), e.g., physical vs intellectual disability services (MSSS 2015b, 2016).

The 2017 action plan reiterates and further highlights barriers in access to and coordination of services spanning physical, mental health and dependence services for all age groups when they need it. The plan underlines the concern that absence of these services means that health issues in some individuals with autism are not addressed, contributing to the deterioration of their condition. While the plan attributes access problems to both personal and environmental factors, it suggests that a programmatic approach (‘programs-services’) may address this challenge. This indicates a set of services and activities organized to meet the needs of people in terms of health and social services, or those of a group of persons who share a common issue.

In addition, the 2017 action plan indicates that community organizations that offer complementary services, e.g., respite, lack necessary resources. Hiring, training and retention of staff are understood as important obstacles for optimization of existing resources.

Recommendations for service improvement

Some of the recommendations for healthcare providers suggest that parent involvement in treatment services should be a priority. Further, knowledge transfer between different organizations is necessary to ensure quality of interventions (Mercier 2014). Other recommendations are aimed at supporting the integration of health and social services to guarantee service access, continuity and complementarity for persons with autism and their families, or improve service integration outcomes in the wake of recent restructuring initiatives in the Quebec health network (MSSS 2015b, 2017c).

Recommendations also underscored the importance of interdisciplinary approaches and the need to tailor assessment tools and the intervention approaches to the needs of the child, rather than just the diagnosis (MSSS 2012b; Mercier 2014). Finally, the Ministry of Health and Social Services suggests setting up norms and standards for offering specialized rehabilitation services tailored to a large profile of users (MSSS 2015a).

Most of these recommendations are repeated in the 2017 action plan reflecting long-standing recognition of the same service improvement goals. In addition, the new plan highlights the need to elaborate and implement local agreements of collaboration between the provincial network of health and social services and the education network to better support youth with autism, in a spirit of complementarity of services.

The plan also introduces knowledge transfer across multiple services and from service providers to parents, as a mechanism to address the discontinuity problem and ensure complementarity between services. For instance, parents opt for family medicine practices for their consultation, and deployment of professionals in these practices would enhance cross-professional collaborations and guarantee rapid access to primary care services (MSSS 2017a).

Finally, a key objective of the 2017 plan is to allow better access to services from different networks for persons having behavioural disorders, specifically by ensuring access to both general and specific services of the integrated health and social services centres, spanning physical, mental health and dependency services.

In fact, autistic persons are at risk of developing mental and physical health issues, such as anxiety, which is known to increase their vulnerability and interfere with their ability to navigate different systems and defend their fundamental rights. The new governance of the Quebec network of health and social services would help by facilitating access to the different programs and services. In addition, other networks such as public security and justice may be involved to support autistic adults in their social integration (whereby challenges such as crisis interventions, issues with police, legal procedures, etc. may increase the risk of stigma and isolation). Cross-sector consultations were held in this direction, but greater efforts are still needed to adapt the Quebec justice system to the special behavioural concerns of persons with mental and developmental disorders (MSSS 2017a).

Training

Production and utilization of informational tools and training programs is a major theme across policy documents. These include training plans specially designed for professionals working with those developmental disorders (MSSS 2015a). They also include increasing awareness among general practitioners and paediatricians about the importance of early recognition and management of autism (MSSS 2012b).

The 2017 plan also adds the need for training in the education sector, by providing school staff both in regular classes and complementary services (e.g., psychologist, special educators) with continuing education and in-service training. This training would promote a better response to the diverse needs of students with autism and contribute to their educational success and integration (MSSS 2017a).

Taken together, our review revealed many provincial policy documents dating back to 2011. Consistent themes emerged across these documents, reflecting recognition of the importance of offering family-centred and coordinated care across the lifespan, and with emphasis on the early years. The policies also consistently acknowledge a range of barriers preventing the province from achieving these objectives. In the next section, we examine the consistency between these provincial policies and national and international policy frameworks.

Social justice in policy

We investigate whether the identified provincial policies reflect social justice principles as defined in relevant national and international frameworks. Nationally, we considered the Canadian model of Social Determinants of Health, introduced by Mikkonen and Raphael in 2010 (Mikkonen and Raphael 2010; Raphael 2009) as an evidence-based representation of the health-shaping conditions in which Canadians live and grow. By accounting for the spectrum of existing inequities of health in the Canadian society, this model is embedded in social justice principles with a special focus on policy implications, which makes it the perfect guideline for our analysis. The 14 social determinants of health introduced in this model are Aboriginal status, gender, disability, housing, early life, income and income distribution, education, race, employment and working conditions, social exclusion, food insecurity, social safety network, health services, as well as unemployment and job security.

Many autism policies identified were strongly aligned with the Social Determinants framework. This includes policies that aim at stimulating social inclusion by an increased access to services and participation in leisure activities. Likewise, policies intended to provide financial assistance for autistic persons are consistent with improving income as basic perquisite of health, etc. Appendix Exhibit C1 illustrates in further detail how Quebec’s policies reflect social determinants. While some social determinants are extensively reflected in public policies in Quebec, others like Aboriginal status, race, education and unemployment are especially underrepresented, signalling some gaps.

Discussion

Several provincial policies and guidelines related to autism are also congruent with the international framework protecting the rights of persons with disabilities. The policies overall promote social justice for persons with disabilities as a group, decrease marginalization, reaffirm access to services as a human right, and acknowledge that disability is a social construct. Specific policies also promote social justice either by addressing specific barriers, e.g., financial (MELS 2014; OPHQ 2011a; MFA 2016a), and/or promoting access to services without discrimination (MSSS 2012b; MFA 2015). Appendix Exhibit C1 further details the linkages between the provincial policies and international human rights framework as represented by the UNCRDP.

Provincial autism policies align basic principles of human rights and health promotion and promote principles that are proposed by international agencies—which are often the result of extensive stakeholder and expert consultations. Nevertheless, some gaps remain, which may explain the consistent reaffirmations of certain policies since 2011 with limited progress in achieving their objectives. These gaps are person-centredness, coordination and continuity of services, evaluation of economic costs, enactment mechanisms and evidence-based policymaking.

Person-centredness

Quebec health and social services overall adopt principles of person-centredness and continuity. However, most of the policies reviewed are instead centred around specific life periods, mainly childhood (e.g., promoting community participation of affected children and their integration in school settings), and less emphasis on other key transition points across the lifespan (e.g., employment and housing opportunities).

Our review of policies suggests that many services are also still characterized by a ‘one size fits all’ approach, instead of being tailored on individual and unique needs and preferences of each person/family. Further, relevant social determinants such as race, Aboriginal status, education and unemployment were relatively underrepresented in Quebec policies.

The 2017 Quebec action plan has begun to address specific components of this challenge, mainly those focused on adults. First, the plan calls for intervention programs that are more specialized and adapted to the various needs of persons with autism, with a special emphasis on supporting service navigation to improve its continuity and person-centredness.

Further, the plan calls for implementation of a wide range of services to meet the needs of adults with autism more specifically, including (a) coordinated and concerted offer of services to youth at the end of their school, (b) more socio-professional and community services for adults who completed schooling, (c) promoting educational success for youth by implementing transition mechanisms for students from secondary level to college, and (d) specific and specialized offer of services to adults with autism. In this regard, the new Quebec plan is consistent with federal initiatives aimed at filling the void of employment options, especially those resulting in a living wage.

The latter is especially important given the recognition that the majority of adults with autism live with their ageing parents and rely on income derived from combinations of partial work, family support and public support (Dudley et al. 2014). Apart from specific measures introduced by the Government of Quebec, such as the autonomy insurance model (MSSS 2013), other gaps remain affecting youth and adults, including income support, housing and support for care giving.

Coordination and continuity of services

Another related recurring challenge outlined by policies is the continuity of services within specific transition periods and across the lifespan (MSSS 2015b). The way the service is organized in Quebec creates distinct administrative categories within health and social services by age groups (children, youth and adults), type of disability (physical vs. intellectual vs. mental health), geographic region (reflected by the different health networks), as well as across sectors (health and social services, education, family). To date, Quebec has not directly addressed how the distinct administrative umbrellas can result in services coordinated coherently around the needs of a single person/family and continuously across the life.

The recent shift in focus from childhood to adult services appears to address the challenge of continuity and person-centred care by increasing adult services. However, the proposed measures still do not account for the fact that autism is a complex lifelong condition and a person with autism is unlikely to neatly fit within these simplistic categories. In fact, a concerning trend is the suggestion that resources currently directed towards children and adolescents would be redirected to other age periods (Dudley et al. 2014), rather than support programs being intentionally designed as lifelong and person-centred.

Challenges related to service discontinuity are partly addressed by the act to reorganize the health and social services network adopted by the Ministry of Health in 2015. This reorganization was considered an opportunity to harmonize practices and improve the flow of services through the abolition of regional agencies and the merger of various institutions to establish new integrated health and social services centres to the benefit of users. In this perspective, programs for physical disabilities were merged with those for intellectual disabilities (including ASD) under the same clinical board (MSSS 2017b).

A recent evaluation of the integration of services as a part of the reorganization of the health network was recently conducted by the MSSS. From an organizational perspective, overall results point towards minor changes and are, for the most part, unsatisfying (MSSS 2017c). Shortcomings were identified across various dimensions, several of which are consistent with the barriers identified in autism policies presented above. For example, the evaluation document reported a lack of coordination between local community health centres and rehabilitation centres and even between educators and professionals working in these institutions (MSSS 2017c). As such, coordination and continuity challenges in autism appear to be instances of more general challenges at the forefront of the reorganization of services.

Economic analysis of costs associated with autism

Autism is one of society’s most costly neurodevelopmental conditions (Dudley et al. 2014; Buescher et al. 2014).

Besides the psychological and emotional burden, three categories of costs may arise for autistic persons. First, there are direct costs related to healthcare, social services and education. Other indirect costs include reduction in income or productivity losses as well as the cost of informal care. Intangible costs are defined as the impacts on quality of life, also known as ‘the burden of disease’ (Ganz 2007).

While the first category of costs mostly occurs during childhood and adolescence, the remaining ones extend to adult life. Indeed, a 2006 study from the United States clearly suggests that costs arising from adult care and loss of employment opportunities of both the individual with autism and his/her parent account for the most substantial amounts among the variety of costs included. In particular, adult care has the largest lifetime cost of all direct costs, which is more than five times larger than the next three largest costs which include care incurred during childhood (child and respite care, behavioural therapies and special education) (Ganz 2007).

While the policies identified in this review aim at reducing the burden of some direct and tangible costs related to healthcare, very little efforts are made to tackle long-term and more indirect costs. The poor link made between the needs and opportunities for the same person as a child and an adult contributes to this challenge. Specifically, limited recognition that early intervention is in principle intended to reduce lifetime costs has not been clearly acknowledged in the recent Quebec plan.

Public policies focusing on healthcare often underestimate the overall economic burden of lifelong conditions (Lavelle et al. 2014; Dudley and Emery 2014). Other measures are needed to mitigate the financial burden incurred by families outside the healthcare system, such as respite and community services (Lavelle et al. 2014), and also within the education systems where costs to additional supports needed for children and youth with autism are a major component of economic burden on families.

Action and enactment of policy

Even though the majority of policies discussed action plans or described services, these plans rarely articulated specific enactment mechanisms or benchmarks. Few examples of action or enactment within the documents were mechanisms such as the establishment of cooperative agreements between service centres improving access to supra-regional services developed to systematize service offerings (MSSS 2012b).

One possible reason for the absence of enactment mechanisms at the provincial level is that services are locally administered by individual municipalities. Yet, the inconsistency in enactment mechanisms may lead to exclusion and discrimination of vulnerable regions and/or individuals (MSSS 2012b). For instance, a recent evaluation of service integration for persons with disabilities indicates that local institutions have little knowledge of the 2008 access plan. The evaluation also reports partial implementation of mechanisms in relation to the network of integrated services, the majority of which should have been implemented since 2008 (MSSS 2017c).

Available data suggest that nearly 40% of families affected by autism do not have access to any services around the time of diagnosis (Volden et al. 2015). The lack of enactment mechanisms may explain why the same barriers to access to services have been reaffirmed over the past 6 years, including long wait times for diagnostic and intervention services, poor care coordination across different levels of service, and inadequate support for caregivers. Further, the limited attention to social determinants, including income and race, suggests that potential disparities in access to and utilization of autism services likely exist but are currently unreported (OPHQ 2011a).

Evidence-informed policymaking

Evidence-based practice is a major principle in health and social services as well as in educational services. Our analysis determined whether the policies identified rely on original academic research, systematic reviews or robust consensus-building methods.

Generally, there is a very small evidence base for the information presented in the policies. It is unclear whether the recommendations to providers and parents are evidence-based. Some of the reviewed documents contain no bibliography (MELS 2014; MFA 2016a, 2014; MSSS 2015a) while others are based on ministry reports and stakeholder consultations without mentioning any scientific literature (MSSS 2012a, b). Most documents are mainly based on government and professional reports.

Only five policy documents specifically included academic research. This is the case for documents introducing and evaluating the integration of services from the Ministry of Health and Social Services (MSSS 2017b, c). The white paper on the creation of autonomy insurance is also clearly based on scientific and demographic well-documented and published data (Quebec, G.o. 2013). Likewise, the plan to prevent and counter bullying (MFA 2015) is based on research articles on peer victimization during childhood and adolescence, and their psychological effects. Finally, only two documents use systematic reviews (Mercier 2014; MSSS 2017c). As such, there is a limited use of research evidence in provincial policy.

Finally, one should note that this knowledge gap is bidirectional since policies are often unknown to academia, and a number of research priorities have been reported to be disconnected from the needs of the public health practice. Many factors contribute to this gap, including the nature of many Canadian public health academic settings and university faculties that are unlinked to policy and practice (McAteer et al. 2018).

Future directions

We propose that root cause of challenges currently confronting the policy environment in Quebec includes limitations in: specific measures to address long-standing and well-understood barriers, adoption of a person-centred approach across the lifespan, recognition of economic costs associated with autism, and utilization of research evidence.

Particularly important in a public health system, a thorough economic evaluation would also be crucial to assess the costs of new services proposed by policy restructuring as well as the costs of not providing certain services to children as they grow, and to families as they support their child development. More specifically, governments should consider early intervention as a positively compounding investment. Indeed, the per capita lifetime cost of untreated autism is estimated at between $2 and $4 million (Ganz 2007; Newschaffer et al. 2007).

Training programs are a good first step towards sustainable solutions for current challenges in diagnosis and interventions for autism. However, this should be extended to a broader transformative framework of capacity building in existing resources. This approach is consistent with the WHO recommendations (World Health Organization 2013) and the UN’s Millennium Development Goals (United Nations 2015) calling for strategies that focus on process rather than targets and in which success would come from the building on community strengths. More specifically, we propose that public practices should thoughtfully consider the best way to identify at-risk children in different communities, building on strong existing community-based child health programs (Dudley et al. 2014).

In addition to training, research has always been a key element of these transformative strategies for autism services worldwide. However, Quebec has never recognized its significant knowledge and innovation advances or the knowledge gaps that remain, nor, most importantly, identified how existing knowledge could be used to transform services. The Quebec government could capitalize on its centralized health systems to advance discovery while improving the services offered to patients. For instance, integrating research being conducted in academic health centres through knowledge translation initiatives could bring about innovations directly to the benefit of the system, such as new tests and therapies, in their care pathways to offer high-quality services. Knowledge about existing policies can educate families and service providers about their rights and empower them to advocate for better services (Shikako-Thomas and Law 2015; Forsyth et al. 2007).

At the same time, research can inform policymaking through the development of benchmarking for policy to practice and providing information about families’ needs and service usage. Future research could inform this process through comparative analysis of autism policies with other Canadian provinces to inform governments about equity in service provision for families across the country, and to combine efforts and replicate best practices to improve the quality and efficacy of services while reducing long-term costs to the systems and promoting quality of life for individuals with autism and their families.

Limitations

We aimed to limit our scope to a local yet comprehensive search, which limits the generalizability of the results to the federal level. The scan was limited to provincial ministry websites and government reports to identify relevant local legislation, policies and approved guideline documents that exist to varying degrees across Canada. Recommendations produced by a non-governmental body within and outside Quebec were beyond the scope of our scan. Also, documents that were not freely available to the public were not included. A second limitation is related to the search period, subject to the date restrictions defined in the initial search. Thus, our search does not capture reports published after this date and provides a snapshot of information retrieved during that time period.

Conclusion

In principle, autism policies articulated at the provincial level in Québec are comprehensive, well grounded in international and national framework, and consistent with international human rights principles. The 2017 Action Plan marks an advance towards improving services for persons with autism. Policy documents also recognize existing barriers in the systems and propose some key directions to overcome them. However, major questions remain unresolved with regard to the enactment of measures identified and turning them into concrete reality.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 156 kb)

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Buescher AV, et al. Costs of autism spectrum disorders in the United Kingdom and the United States. JAMA Pediatrics. 2014;168(8):721–728. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CASDA. (2016). Better together: The case for a Canadian autism partnership. Canadian Autism Spectrum Disorders Alliance. https://capproject.ca/en/images/pdf/CAPP_Business_Plan_EN.pdf

- Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (2009) Systematic Reviews: CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. https://www.york.ac.uk/media/crd/Systematic_Reviews.pdf

- Contandriopoulos D, et al. Structural analysis of health-relevant policy-making information exchange networks in Canada. Implementation Science. 2017;12(1):116. doi: 10.1186/s13012-017-0642-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diallo, F. B., et al. (2017). Prevalence and correlates of autism spectrum disorders in Quebec. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 0706743717737031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dudley, C., & Emery, J. (2014). The value of caregiver time: Costs of support and care for individuals living with autism spectrum disorder. .

- Dudley, C., et al. (2014). The autism opportunity. Needs and solutions for Canadians with disabilities, in The Policy Magazine.

- Eggleton A, Keon W. Final report on the enquiry on the funding for the treatment of autism. Pay now or pay later. Autism families in crisis [Internet] Ottawa: The Standing Senate Committee on Social Affairs. Science and Technology; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Elsabbagh M, et al. Global prevalence of autism and other pervasive developmental disorders. Autism Research. 2012;5(3):160–179. doi: 10.1002/aur.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsabbagh M, et al. Community engagement and knowledge translation: Progress and challenge in autism research. Autism. 2014;18(7):771–781. doi: 10.1177/1362361314546561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EPPI-Centre . EPPI-Centre methods for conducting systematic reviews. London: EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth R, et al. Participation of young severely disabled children is influenced by their intrinsic impairments and environment. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2007;49(5):345–349. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.00345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganz ML. The lifetime distribution of the incremental societal costs of autism. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2007;161(4):343–349. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.4.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greschner D, Lewis S. Auton and evidence-based decision-making: Medicare in the courts. Canadian Bar Review. 2003;82(1):501–533. [Google Scholar]

- Hancock, T. (1985). Beyond health care: From public health policy to healthy public policy. Canadian Public Health Association. [PubMed]

- Howlin P, Magiati I, Charman T. Systematic review of early intensive behavioral interventions for children with autism. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. 2009;114(1):23–41. doi: 10.1352/2009.114:23-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavelle TA, et al. Economic burden of childhood autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2014;133(3):e520–e529. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manfredi, C. P., & Maioni, A. (2005). Reversal of fortune: Litigating health care reform in Auton v. British Columbia. In: The Supreme Court Law Review: Osgoode’s Annual Constitutional Cases Conference.

- McAteer, J., et al. (2018). Bridging the academic and practice/policy gap in public health: Perspectives from Scotland and Canada. Journal of Public Health (Oxford, England). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- McDonald T, Machalicek W. Systematic review of intervention research with adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2013;7(11):1439–1460. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2013.07.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MELS. (2014). Guide des Normes Nationales: Programme d’assistance financière au loisir des personnes handicapées, d.L.e.d.S. Ministère de l'Éducation, Editor. Gouvernement du Québec.

- Mercier, C. (2014). L’efficacité des interventions de réadaptation et des traitements pharmacologiques pour les enfants de 2 à 12 ans ayant un trouble du spectre de l’autisme (TSA), l.I.n.d.e.e.s.e.e.s.s. (INESSS), Editor. Gouvernement du Québec.

- MFA. (2014). Plan d'action 2012–2015 du ministère de la Famille à l'égard des personnes handicapées, M.d.l.F.e.d. Aînés, Editor. Gouvernment de Québec.

- MFA. (2015). Ensemble contre l’intimidation, une reponsabilité partagée - Plan d'action concerté pour prévenir et contrer l’intimidation 2015–2018. Gouvernement du Québec.

- MFA. (2016a). Principales mesures de soutien destinées aux familles et aux enfants. Annexe au bilan 2010–2015 des réalisations en faveur des familles et des enfants., M.d.l. famille, Editor. Gouvernement du Québec.

- MFA. (2016b). Bilan 2015–2016 du Plan d’action 2015–2018 du ministère de la Famille à l’égard des personnes handicapées, M.d.l. famille, Editor. Gouvernement du Québec.

- MFA. (2017). Bilan 2016–2017 du Plan d’action 2015–2018 du ministère de la Famille à l’égard des personnes handicapées, M.d.l. Famille, Editor. Gouvernement du Québec.

- Mikkonen J, Raphael D. Social determinants of health: The Canadian facts. Toronto: York University, School of Health Policy and Management; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- MSSS. (2012a). Évaluation de l’implantation du plan d’accès aux services pour les personnes ayant une déficience 2008–2011, M.d.l.S.e.d.S. sociaux, Editor. Gouvernement du Québec.

- MSSS. (2012b). Bilan 2008–2011 et perspectives: UN GESTE PORTEUR D’AVENIR: Des services aux personnes présentant un trouble envahissant du développement, à leurs familles et à leurs proches, M.d.l.S.e.d.S. sociaux, Editor. Gouvernement du Québec.

- MSSS. (2013). L’autonomie pour tous. Livre blanc sur la création d'une assurance autonomie, M.d.l.S.e.d.S. sociaux, Editor. Gouvernement du Québec.

- MSSS. (2015a). Bilan annuel 2014–2015 du plan d'action à l'égard des personnes handicapées 2011–2014. Gouvernement du Québec.

- MSSS. (2015b) Plan d'action ministériel- Rapport spécial du Protecteur du citoyen: L'accès, la continuité et la complémentarité des services pour les jeunes (0–18 ans) présentant une déficience intelletuelle ou un trouble du spectre de lautisme, M.d.l.s.e.d.s. sociaux, Editor. Gouvernement du Québec.

- MSSS. (2016). Bilan des orientations ministérielles en déficience intellectuelle et actions structurantes pour le programme-services en déficience intellectuelle et en trouble du spectre de l’autisme, D.d.l.o.d.s.e.d.e.e.r. physique, Editor. Gouvernement du Québec.

- MSSS. (2017a). Des actions structurantes pour les personnes et leur famille. Plan d'action sur le trouble du spectre de l'autisme 2017–2022., M.d.l.S.e.d.S. Sociaux, Editor. Gouvernement du Québec.

- MSSS. (2017b). Vers une meilleure intégration des soins et des services pour les personnes ayant une déficience. Cadre de référence pour l’organisation des services en déficience physique, déficience intellectuelle et trouble du spectre de l’autisme, M.d.l.S.e.d.S. Sociaux, Editor. Gouvernement du Québec.

- MSSS. (2017c). Évaluation de l’intégration des services pour les personnes ayant une déficience physique, intellectuelle ou un trouble du spectre de l’autisme (DP, DI-TSA), M.d.l.S.e.d.S. Socaux, Editor. Gouvernement du Québec.

- Newschaffer CJ, et al. The epidemiology of autism spectrum disorders. Annu Rev Public Health. 2007;28:235–258. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver S, et al. An emerging framework for including different types of evidence in systematic reviews for public policy. Evaluation. 2005;11(4):428–446. doi: 10.1177/1356389005059383. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- OPHQ. (2011a). Guide des programmes d'aide pour les personnes handicapées et leur famille: Aide financière, équipements et fournitures, O.d.p.h.d. Québec, Editor. Gouvernement du Québec.

- OPHQ. (2011b). Guide des besoins en soutien à la famille pour les parents d'un enfant un d'un adulte handicapé: Deuxième partie- renseigmenents pratiques, O.d.p.h.d. Québec, Editor. Gouvernement du Québec.

- OPHQ. (2011c). Guide des besoins en soutien à la famille pour les parents d'un enfant un d'un adulte handicapé, O.d.p.h.d. Québec, Editor. Gouvernement du Québec.

- OPHQ. (2017a). Guide des mesures fiscales provinciales et fédérales à l'intention des personnes handicapées, de leur famille et de leurs proches O.d.p.h.d. Québec, Editor. Gouvernement du Québec.

- OPHQ. (2017b). Guide des programmes destnés aux personnes handicapées, à leur famille et à leurs proches, O.d.p.h.d. Québec, Editor. Gouvernement du Québec.

- OPHQ. (2017c). Guide sur le parcours scolaire pour les parents d'un enfant handicapé, O.d.p.h.d. Québec, Editor. Gouvernement du Québec.

- Raphael D. Social determinants of health: Canadian perspectives. Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen M, Lewis O. United Nations Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. International Legal Materials. 2007;46(3):441–466. doi: 10.1017/S0020782900005039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd CA, Waddell C. A qualitative study of autism policy in Canada: Seeking consensus on children’s services. J Autism Dev Disord. 2015;45(11):3550–3564. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2502-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shikako-Thomas K, Law M. Policies supporting participation in leisure activities for children and youth with disabilities in Canada: From policy to play. Disability & Society. 2015;30(3):381–400. doi: 10.1080/09687599.2015.1009001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC medical research methodology. 2008;8(1):45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations . The Millennium Development Goals Report 2015. New York: United Nations; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Volden J, et al. Service utilization in a sample of preschool children with autism spectrum disorder: A Canadian snapshot. Paediatrics & child health. 2015;20(8):e43. doi: 10.1093/pch/20.8.e43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren Z, et al. A systematic review of early intensive intervention for autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2011;127(5):e1303–e1311. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . Meeting report: Autism spectrum disorders and other developmental disorders: From raising awareness to building capacity. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 156 kb)