Abstract

Objective

To understand the oral healthcare experiences of humanitarian migrants in Montreal and their perceptions of ways to improve access to oral healthcare.

Methods

We used focused ethnography informed by a public health model of the dental care process. The adapted McGill Illness Narrative Interview (MINI) guided interviews of a purposeful sample of humanitarian migrants who received or needed dental care in Montreal. Each interview (50–60 min) was audio-recorded for verbatim transcription. Observation of dental care episodes occurred during mobile dental clinics in underserved communities over the same period (2015–2016). Data analysis combined deductive codes from the theoretical frameworks and inductive codes from interview transcripts and field notes to inform themes.

Results

We interviewed 25 participants (13 refugees and 12 asylum seekers) from 10 countries, who had been in Canada for a range of 1 month to 5 years. The dental care experiences of participants included delayed consultation, proximity to dental clinics, quality care, limited treatment choices, high cost, and long waiting times. A more inclusive healthcare policy, lower fees, integration of dental care into public insurance, and creation of community dental clinics were proposed strategies to improve access to dental care.

Conclusion

Humanitarian migrants in this study experienced inadequate oral healthcare. Their lived experiences help us to identify gaps in the provision of oral healthcare services, and suggestions of participants have great potential to improve access to oral healthcare.

Keywords: Oral healthcare experience, Humanitarian migrants, Canada

Résumé

Objectif

Comprendre les expériences de soins buccodentaires de migrants pour raison humanitaire à Montréal et leurs perceptions des moyens d’améliorer l’accès aux soins buccodentaires.

Méthode

Nous avons utilisé l’ethnographie ciblée éclairée par un modèle de santé publique du processus des soins dentaires. La version adaptée de l’outil McGill Illness Narrative Interview (MINI) a guidé les entrevues auprès d’un échantillon intentionnel de migrants pour raison humanitaire ayant reçu ou ayant eu besoin de soins dentaires à Montréal. Chaque entrevue (50 à 60 min) a été enregistrée, puis transcrite mot pour mot. Une observation d’épisodes de soins dentaires a eu lieu sur la même période (2015–2016) lors de cliniques dentaires mobiles dans des collectivités mal desservies. L’analyse des données a combiné les codes déductifs des cadres théoriques et les codes inductifs des transcriptions d’entrevues et des notes de terrain pour éclairer les thèmes.

Résultats

Nous avons interviewé 25 participants (13 réfugiés et 12 demandeurs d’asile) de 10 pays qui étaient au Canada depuis 1 mois à 5 ans. Le report de consultations, la proximité des cliniques dentaires, la qualité des soins, les options de traitement limitées, les coûts élevés et les longs délais d’attente ont été mentionnés parmi les expériences de soins dentaires vécues par les participants. Pour améliorer l’accès aux soins dentaires, il a été proposé d’élargir la population visée par les politiques de soins de santé, de réduire les frais, d’intégrer les soins dentaires dans le régime d’assurance publique et de créer des cliniques dentaires de proximité.

Conclusion

Les migrants pour raison humanitaire ayant participé à l’étude ont reçu des soins buccodentaires inadéquats. Leurs expériences nous ont aidés à cerner les lacunes dans la prestation des services de soins buccodentaires, et leurs suggestions pourraient grandement améliorer l’accès aux soins buccodentaires.

Mots-clés: Expérience de soins buccodentaires, Migrants pour raison humanitaire, Canada

Introduction

Canada receives approximately 25,000 refugees and asylum seekers each year (Government of Canada 2017). For this study, the term humanitarian migrants refers to refugees and asylum seekers. Humanitarian migrants often arrive in Canada with limited finances and precarious health that requires medical care upon their arrival (Redditt et al. 2015). Global evidence indicates high burden of oral diseases in this population (Keboa et al. 2016). The limited Canadian data also suggest significant levels of oral disease in this population (Ghiabi et al. 2014; Reza et al. 2016). Poor oral health can lead to pain, difficulty in chewing, low self-esteem, and social ostracism (Moeller et al. 2015). Furthermore, the increasing association between poor oral health and general health suggests higher risk of systemic diseases for individuals with poor oral health and vice versa (Linden et al. 2013). Such an association is of greater concern for humanitarian migrants who are already vulnerable to fragile health.

Access to oral healthcare is a determinant of individual and population oral health status. For humanitarian migrants, the healthcare policy of the host country or administrative region defines the range of insured services. Oral health policies can vary between host countries and within different regions of the same country (Keboa et al. 2016). Difficulty in finding relevant oral health information, the high cost of dental care, and inability to speak the local language are some of the barriers to accessing oral healthcare for this population. The precarious access to oral healthcare contributes to the high burden of oral disease experienced by this population compared even to groups of low socio-economic status (SES) in the host countries (Keboa et al. 2016).

In Canada, oral healthcare is provided mainly by the private sector and many Canadians experience costs of dental services as prohibitive (Ramraj et al. 2013). Such costs may be even more unaffordable for humanitarian migrants in Canada who depend on social assistance, or work part-time jobs that pay the minimum wage (Pitt et al. 2016). Calvasina and colleagues described irregular access to the dentist as a major predictor of the deteriorating oral health of immigrants during their first 4 years in Canada (Calvasina 2014). We can anticipate a similar or even worse trend for humanitarian migrants who often have oral diseases upon arrival, and limited resources (Keboa et al. 2016).

Humanitarian migrants in Canada can benefit from healthcare services funded through the federal government’s Interim Federal Health Program (IFHP) (Government of Canada 2018a). The IFHP policy establishes the healthcare benefits for the various categories of humanitarian migrants: Government-Assisted Refugees (GARs), Private Sponsored Refugees (PSR), refugee claimants (asylum seekers), and in-Canada refugees (Government of Canada 2018b). Insured services include outpatient consultation, hospitalization, laboratory investigations, and emergency dental care during the first 12 months in Canada. Emergency dental care comprises tooth extractions, incisions and drainage of dental abscesses, and treatment of life-threatening complications of dental origin. However, it excludes root canal treatment, cleaning of the teeth, and fabrication of crowns (Government of Canada 2018a). The IFHP policy is subject to amendment. A major reform in 2012 significantly reduced the IFHP budget and terminated dental care, vision care, and medication benefits to all humanitarian migrants except for GARs. While this 2012 reform was revised in 2016, at the time of this study, only GARs could receive free emergency dental care. Therefore, other categories of humanitarian migrants, who make up 75% of this population, had to access even emergency dental care through private means.

An optimal state of oral health can facilitate the integration and economic productivity of humanitarian migrants (Khoo 2010) and contribute to the positive mental health of this population. Since 2011, about 400,000 humanitarian migrants have arrived in Canada; this increase far exceeds the prior annual average of 25,000 entries (Government of Canada 2017).

Although this population is vulnerable to poor oral health and has limited access to dental care (Ghiabi et al. 2014; Canadian Academy of Health Sciences 2014), we lack evidence on their dental care process. The purpose of our study was to explore and understand the dental care experiences of humanitarian migrants and dentists in order to inform policy and services for the population. The specific objectives of this paper are (i) to report our findings regarding the oral healthcare process as experienced by humanitarian migrants in Montreal and (ii) to explore the perceptions of Montreal’s humanitarian migrants on how to improve access to oral healthcare.

Methods

We chose a qualitative design using focused ethnography (Knoblauch 2005) due to its pragmatic approach and applicability of the findings in healthcare. This methodology combines individual interviews and participant observation and allows researchers to explore and understand a health phenomenon among service users and/or providers within a socio-cultural context (Higginbottom et al. 2013). Focused ethnography is also sensitive to cultural and social diversities which are common characteristics of humanitarian migrant populations (Higginbottom et al. 2013).

Theoretical framework

The public health model of the dental care process proposed by Grembowski and colleagues (Grembowski et al. 1989) and an adapted McGill Illness Narrative Interview (MINI) (Groleau et al. 2006) served as our theoretical frameworks. The Grembowski and colleagues’ model conceptualizes the dental care process into two broad stages: the phase preceding the episode of care and the actual care episode. It further provides possible explanations for decisions during the dental care trajectory. According to the model, the dental care process is influenced by several factors: structural (SES of the individual within a given social context); illness history (presence or absence of illness features and their severity); cognitive factors (beliefs, oral health literacy, lay referral system); and expectations (perceived advantages and costs of a treatment). The MINI is a theoretically-based semi-structured interview guide designed to capture narratives of illness experience, including the shared cultural aspects and behaviours of an individual or a group (Groleau et al. 2006). The semi-structured questions of the tool make it appropriate for use in focus ethnography (Higginbottom et al. 2013). These questions are divided into four sections: initial illness narrative; explanatory model; services and response to treatment; and impact on life. Using this tool therefore enables researchers to obtain in-depth understanding of the participants’ illness experience.

Data collection

The primary researcher (MK), a foreign-trained dentist with 14-years of experience, collected the data. In collaboration with two non-profit community organizations, the study was introduced to potential participants using word-of-mouth, phone calls, and informational flyers. For eligibility, an individual had to be a refugee or asylum seeker, aged 18 years and above, and must have used or desired to use dental services in Canada. The purposeful sample varied in age, gender, and country of origin. Individual in-depth interviews were conducted in English, French, or Spanish, the languages spoken by most of the study’s population (Government of Canada 2017), using an adapted McGill Illness Narrative Interview (MINI) guide (Groleau et al. 2006). The primary researcher (MK), who is bilingual in English and French, conducted, audio-recorded, and transcribed the interviews, except for two Spanish interviews that were conducted and then transcribed into English with the help of a translator. Each interview took place in a negotiated venue, lasted 50–60 min and was audio-recorded after obtaining signed informed consent.

Participant observation (January 2015–February 2016) occurred during mobile dental clinics that provided free basic care to underserved communities in Montreal. Different community organizations hosted the monthly dental clinics, each lasting approximately 5 h. During the visits, the primary researcher (MK) observed the interactions between the patients and staff of the community centre, non-clinical members of the dental team, dentists, and dental students during consultation and treatment. In addition, reasons for attendance, cultural background, personal histories, knowledge about the service, and treatment expectations were discussed with the migrants and field notes were documented.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed for themes using an iterative process that included coding of the text, sorting for patterns, identifying outliers, and making reflective notes guided by the field memos (Higginbottom et al. 2013). After each interview, the first author completed an Interview Report Form designed to facilitate reflexivity (Higginbottom et al. 2013). The completed form included a summary of the interview, reflexive notes, and concepts to be explored in subsequent interviews. We stopped further interviews when data from the completed Interview Report Forms, field notes, and interviews suggested the adequacy and richness of data collected to answer the research question. Three authors shared the verbatim transcripts of interviews and completed Interview Report Forms. The R package for Qualitative Data Analysis software (Huang 2014) facilitated data coding and synthesis. Deductive codes drew upon the Grembowski and colleagues’ model (Grembowski et al. 1989), and MINI (Groleau et al. 2006) and inductive codes were emergent from the text. The core research team met every 2 weeks, over a 2-month period, to discuss emergent themes.

Ethical approval

The McGill Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Results

Description of sample

Participants (n = 25) included 13 refugees and 12 asylum seekers from 10 countries, reflecting the diverse origin of the population in Canada. They had lived in Canada between 1 month and 5 years, and the majority depended on financial support from the government (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of participants

| Variable | N(25) |

|---|---|

| Age (in years) | |

| 18–35 | 13 |

| ≥ 36 | 12 |

| Gender | |

| Men | 9 |

| Women | 16 |

| Region and countries of origin | |

| Latin America | 5 |

| North Africa and Middle East | 5 |

| Russia and South East Asia | 3 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 12 |

| Duration in Canada | |

| ≤ 1 year | 14 |

| 2–4 years | 6 |

| > 4 years | 5 |

| Immigration status | |

| Government-Assisted Refugees (GARs) | 2 |

| Privately Sponsored Refugees (PSRs) | 3 |

| Inland (in-Canada) refugees | 8 |

| Asylum seekers (refugee claimants) | 12 |

| Employment status | |

| Employed (part-time) | 3 |

| Unemployed | 22 |

| Monthly income/allowance | |

| < $700 | 23 |

| $700–$1000 | 2 |

Description of a dental care episode

By 5:30 pm, the spacious basement of the community centre had been transformed into a temporary dental clinic with 10 mobile dental units. This community centre is a non-governmental organization, working to better the lives of newly arrived immigrants. After assisting the dentists, dental technician, and volunteers with setting up the equipment, I joined the registration desk at the entrance to the clinic. Patients, ranging in age from approximately 8 to 60 years, had occupied the 24 seats and took turns completing registration formalities. Some patients received help with translation from a lady I later learned was a volunteer interpreter who spoke English, French, Arabic, Spanish, and Urdu. During the clinic, I moved between the waiting area and treatment hall, holding informal discussions with the patients, dental team, and staff of the community centre. Our discussions touched on the personal histories of the patients, their cultural background, reasons for consultation, how they came to know about the mobile dental clinic, and expected treatment. I was able to move around the dental units as well, where I observed interactions of the patients with the care team at the beginning of the consultations to the end of the care episode. While some patients were all smiling after their dental visit, others were clearly worried when their treatment was postponed. Specifically, individuals who needed further investigation and treatment were referred to the Faculty of Dentistry clinic. Analgesics and/or antibiotics were prescribed when needed, and follow-up care was free.

In the following section, we describe the dental care experiences of our participants under two broad categories drawn for the Grembowski and colleagues’ model: experiences prior to dental consultation and experiences during care episode.

Pre-dental consultation experiences

When asked if participants knew where to go for dental care, the responses were affirmative. They suggested that finding a dental clinic was easy, as clinics were often located in shopping malls that were a walking distance or easily accessible by public transport. For example, one participant resided in a building that accommodated a dental clinic, and another rented an apartment owned by a dentist.

Initial measures in seeking dental care

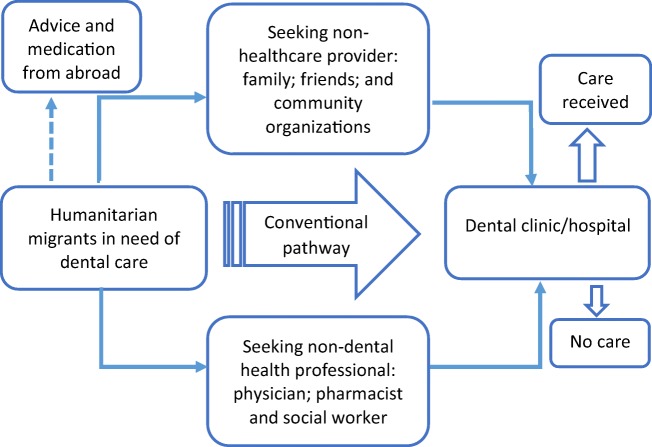

The responses to the question “what did you do when you needed to consult a dentist?” demonstrate that the participants sought help from at least one intermediary source before consulting a dentist (Fig. 1). The resource person was either a non-dental health professional (pharmacist, family physician, or social worker), or a non-healthcare provider (family, friends in Canada or abroad, or staff of non-profit community organizations). The outcomes of these requests varied and influenced the next stage of the dental care process. Some participants did not know how to obtain desired dental care in Canada and decided to seek advice from relatives abroad. Two participants obtained antibiotics from abroad, and another shared the antibiotic of a friend in Canada. On the issue of antibiotics, a participant from Latin America stated:

“I used penicillin to treat the infection. But, how do you say it, I medicated myself because there was no other option. Well [hesitates], the black market or, from someone who would bring some from my country [Mexico]. Because it is not possible any other way….no one will give you anything without a prescription.”

Fig. 1.

Dental care pathways of humanitarian migrants

Participants with prior teeth extractions were eager to consult a dentist for fear of losing another tooth. Individuals who consulted a family doctor were sometimes prescribed medication to control oral infection and/or acute pain. Participants indicated that the intermediary sources they initially contacted (pharmacist; family physician; social worker; and friends) usually advised them to consult a dentist for a definitive solution. However, there were also accounts of friends who advised against going to the dentist because it was too expensive.

Participants who were referred to a facility with the possibility of free dental care remarked on the long waiting time. One participant from sub-Saharan Africa summed up this experience: “I was at (a clinic) where I was placed on a waiting list. Even after six months, I did not hear from them. It was as if I was given false hope and I had been forgotten.”

Experiences from dental care episodes

Cost of treatment

The high cost of dental care in Canada was present in all narratives. Participants heard about the dental fees from a third party prior to contacting a dental clinic. This information was validated during dental consultations in regular clinics. Participants compared the cost of dental treatment to that in their countries of origin where it was much cheaper. In their view, the cost was too expensive given that their financial support could only pay their basic bills. One participant from Congo expressed disbelief that the dentist could not attend to his mother who was in acute pain because he did not have the required money. Affordability was a key factor when considering possible treatment options. This point is illustrated by the response of a participant to a proposed treatment plan: “The dentist told me: if you wanted, with $1000, I can do all treatment for you (referring to root canal treatment). I told him, I do not have $1000, please take away the tooth today, I am not leaving this place until you remove the tooth.”

Despite the relatively high cost of dental treatment, two participants described how they were determined to have their teeth treated and not extracted. To this end, they negotiated a flexible payment schedule with the dental clinic. Discussions with non-dental staff of the mobile clinics also suggested that cost was an important factor in the dental care process of humanitarian migrants.

IFHP coverage

The experiences and views of participants regarding the IFHP ranged from gratitude to serious concerns. For example, GARs and participants who obtained free care from community dental clinics were thankful of the opportunity, as expressed by this participant from Cuba: “I think refugees like me will never be able to pay for dental treatment if not for the government insurance.”

In contrast, some participants expressed concerns over the policy that limited dental benefits to GARs. They argued that the financial benefits and social support of humanitarian migrants compared less favourably to that of permanent residents and Canadians on social welfare. In their view, government should therefore provide humanitarian migrants with similar dental coverage as it does for individuals using social assistance. The decision of the federal government to limit dental care benefits to GARs was experienced as exclusionary: “Yes, I do not understand, some have access while others do not have. At least if they accept people, everyone who is physically present here should be given equal chances to get care.”

The range and extent of dental procedures insured by the IFHP came under questioning by participants. To these participants, the government policy on dental care was designed to promote extraction of teeth. Concerns over the IFHP dental coverage are summarized in this narrative from an asylum seeker:

“It means you actually need to be in a situation where you are helpless and at the point of dying before you are considered for treatment. Besides, dental care in its true sense should include examination, radiology, and proper treatment etcetera. I have not had the luxury of this type of care. I have only gotten a piece of dental care (referring to tooth extraction).”

Kindness and expertise

Consultation with the dentist resulted in one of the following outcomes: initiation of an episode of care; patient placed on antibiotics to control infection prior to the planned dental procedure; referral of patient to a centre equipped to carry out the planned procedure; and treatment not administered due to lack of money. Eleven participants described the quality of treatment in Canada as being superior to that obtainable in their countries of origin. In addition to the technical procedures, they appreciated the collaboration among members of the dental team. A participant from Mexico summed the dental treatment experience: “The treatment was perfect. You know that here, they have all the equipment. Further, you have two assistants to the dentist. Back at home, you are lucky to have one person assisting the dentist. In short, there is no comparison.”

When asked about their interaction with the dentist, most participants were keen to highlight the kindness of their dentist. Acts of kindness varied from one dentist to another and ranged from measures to improve the well-being of the individual to cancelation of treatment cost. For example, a participant from Iraq recounted how the dentist canceled part of her bill:

“Then the dentist said to me: I understand how difficult things are for you at this time, so I will make this gift to you. You no longer owe me for the cleaning. I thanked him and said, finally I am saved.”

According to some participants, dentists took into consideration their specific daily challenges and treated them with dignity and compassion. Discussing the patient’s oral health status and providing advice on personal oral hygiene and treatment possibilities were issues highly valued by these humanitarian migrants. To some, the friendly interaction with the dental team helped to allay their fears and boosted their confidence in the treatment procedure and outcome.

Communication

Not all interactions between participants and the dental team had positive outcomes. Four participants narrated incidents where they felt misunderstood, humiliated, or not provided with appropriate care. Misinterpretation or misunderstanding of the IFHP policy was at the core of these unfortunate situations, as expressed by this 50-year-old refugee claimant from Congo: “My worst experience is with the dentist I met in 2011. In the beginning, he told me that I had coverage by the government. One month later, while I was installed in the dental chair…he announced that I owed the clinic. I asked, how much? I was told I owed $600. This is what has remained in my brain...”

The field notes included details of humanitarian migrants who needed assistance with communication at various stages of the dental care episode. Interpreters assisted the individuals in filling patient records and facilitated communication between the patient and the dental team. An accompanying family member, friend, member of the dental team, or professional interpreter, provided interpretation. Data from interviews did not suggest language was a barrier during the episode of care. However, some participants expressed their preference to consult a dentist who spoke their mother tongue. Breakdown in communication and collaboration between healthcare professionals working in different health facilities had negative effects on the dental care process of some participants. An example is the case of this Congolese woman who explained that she was embarrassed and humiliated with the outcome of a referral:

“As a matter of fact, this lady sent me away! She said to me: ‘Who asked you to come here?’ I was surprised because I had a letter from my social worker where she had appealed that I should be provided emergency dental care.”

Missed appointments

Participants were specifically asked if and why humanitarian migrants were more likely to miss a dental appointment. In responding, the participants first absolved themselves from such practice and insisted that they would call up the dental clinic if they would miss an appointment.

They then suggested possible reasons for missed appointments that were related to “cultural perceptions of time” and “setting priorities amidst daily challenges.” According to two participants, 30 min of lateness for an appointment was acceptable in certain cultures and frowned at in others. They added that it was the responsibility of the dental assistant to educate their clients on the importance of respecting appointments. A participant from Tchad related the possibility of a missed appointment to the mental state of the individual:

“You know, people in our situation also think a lot due to our worries. For example, when you go to bed at 11:00 p.m. to sleep and you start to think, you only fall asleep after about two hours. The result is that you get up late and tired the following morning. And if your brain is not at ease or relaxed, then your whole body is affected.”

From the notes, it emerged that the non-mastery of the public transport system in Montreal and difficulties in adapting to winter conditions were additional reasons why new humanitarian immigrants arrived late or missed their dental appointments.

Improving access to dental care

We specifically asked for suggestions to improve oral health and facilitate access to oral care. Participants were unanimous that government had a major role to play. The proposed strategies included:

-

i)

Change in oral health policy: Participants expressed the desire for the federal government to return to the pre-2012 IFHP policy. Some suggested harmonizing dental care benefits of humanitarian migrants with that offered to social welfare beneficiaries. In Quebec, people on social assistance benefit from publicly-funded dental care that covers emergency care, cleaning of their teeth, and repair of prostheses. Government should consider legislation on pre-travel dental treatment for humanitarian migrants where possible. Alternatively, humanitarian migrants should undergo mandatory dental examination upon arrival in Canada, on condition that treatment is provided for diagnosed disease. The importance of providing treatment is captured in this quote from an Indian participant:

“I will be very angry if I am consulted and not treated. It will be like killing the person. Although, I will like to know if my teeth are in good health or not, I will be at ease if I do not know of the situation…But to disclose my problems and do nothing about it is not correct.”

-

ii)

Lower fees: Participants expressed the need for a reduction in the cost of dental treatment. This would make it affordable for people like themselves who cannot afford the current fees.

-

iii)

Mobile services and community clinics: Three participants from Syria, Iraq, and Mexico suggested the use of specially equipped vans to provide basic dental care in disadvantaged neighbourhoods. In addition, they felt the government should open dental clinics that provide services at reduced rates to humanitarian migrants and other poor populations.

-

iv)

Research and development: Three participants from Burkina Faso, Cuba, and Iraq suggested that Faculties of Dentistry should collaborate with dental companies to develop less expensive dental materials and equipment. It was expected that such innovations could drive down the cost of dental care.

Discussion

This article describes the dental care pathways and experiences of humanitarian migrants and highlights perceived strategies to improve access to dental care. The complex dental care pathways of participants fit the “lay referral system” described in the Grembowski and colleagues’ framework (Grembowski et al. 1989). The framework posits that people of low income will initially try personal coping mechanisms when experiencing dental symptoms. Furthermore, the dental care process is determined by a combination of structural and cognitive factors (Grembowski et al. 1989). In this study, factors beyond the control of participants most strongly shaped their dental care experiences. Half of the participants had lived in Canada for less than 1 year and did not fully understand how the dental care system functions. The inability of newcomers to navigate the healthcare system in Canada contributes to delays in obtaining needed care (Ruiz-Casares et al. 2016).

In the current study, availability and physical accessibility of dental services did not appear to influence the dental care process. This experience is different from that of humanitarian migrants in low-income countries who need to travel hundreds of kilometres to find a dentist (Ogunbodede et al. 2000). Financial constraint emerged as the major barrier to prompt access to dental care. The limited access facilitated self-management using analgesics and, in some instances, antibiotics from non-secured sources. Self-medication is a common reason for the development of resistance to drugs (Michael et al. 2014). Antibiotic resistance can pose challenges with treatment outcome and high cost of alternative drugs for treatment of infectious diseases. In addition to self-medication, financial constraints caused participants to opt for extraction of an offending tooth. Tooth loss impairs oral-health-related quality of life. The care trajectories of humanitarian migrants were congruent with the coping mechanisms proposed in the theoretical framework (Grembowski et al. 1989). However, their actions could inadvertently lead to significant health sequelae as well as increased healthcare costs for treating systemic infections of affected individuals.

The Canada Health Act (CHA) ensures universal access to medical services, however excludes dental care except for urgent oral care provided in hospitals (Canadian Academy of Health Sciences 2014). An estimated 94% of dental expenditure in Canada is from the private sector; the dental treatment costs for humanitarian migrants is part of the 6% public expenditure on dental care (Canadian Academy of Health Sciences 2014). The private model of the dental care system has led to criticism of dentists as being insensitive to the daily realities of the poor. They are perceived to focus on making money and find it difficult to tailor dental services for individuals who cannot afford private dental insurance (Loignon et al. 2010). The experience of high dental fees as a barrier to oral healthcare is thus not a surprise and is supported by the extensive Canadian literature on the topic (Ramraj et al. 2013; Calvasina 2014; Canadian Academy of Health Sciences 2014). Most participants in this study were living in poverty and were not even eligible for publicly-funded dental care because of the IFHP policy that offered limited dental benefits only to GARs. Poverty and high dental fees contributed to delays in initiating care and restricted treatment options for our participants. Indeed, out-of-pocket payment for dental care is a luxury for many working Canadians who do not have dental insurance (Ramraj et al. 2013). Irrespective of the host country, the high price of dental procedures is a common concern for humanitarian migrants who have to pay for these services (Keboa et al. 2016).

Participants had mixed experiences with the IFHP. For GARs, the dental care coverage was a source of relief as beneficiaries did not have to pay for their treatment. In contrast, misinterpretation of the IFHP policy led to unfavourable consequences, such as unexpected dental bills for the patient. The frequent modification of the IFHP policy increases the chances of misinterpretation and refusal of healthcare to eligible humanitarian migrants (Ruiz-Casares et al. 2016). Many participants were not eligible for dental care benefits under the IFHP. For these individuals, the lived experiences negatively affected their oral health quality of life. Healthcare reforms that limit or exclude benefits previously available to humanitarian migrants evoke the feeling of exclusionism (Manjikian 2013). This feeling is similar to perceived discrimination expressed by humanitarian migrants who were refused or asked to pay for services already covered under the IFHP (Merry et al. 2011). Such experiences are likely to increase the stress level of this population. Our findings support the anticipated negative consequences of the 2012-IFHP healthcare reform (Harris and Zuberi 2015).

Despite the delay in accessing care, those participants who did receive care (n = 14) had positive overall experience during treatment episodes. This assessment considered the clinical and non-clinical skills and competences of the dentists. Macdonald and colleagues found a similar high approval rating of dentists and dental services in the province of Quebec generally (Macdonald et al. 2015). Participants appreciated the shared decision in treatment planning and a holistic approach to dental care, attributes that can foster the dentist-humanitarian migrant relationship (Lévesque and Bedos 2012). Empathy during care is especially important for humanitarian migrants who are often stigmatized, misinterpreted, or misunderstood (Moeller et al. 2015). We can expect better treatment compliance and outcomes when service providers pay attention to the socio-cultural background of vulnerable populations. Conversely, underserved populations may avoid using free dental services when they perceive unfair treatment from dentists (Loignon et al. 2010).

Our participants proposed suggestions to improve access to dental care that ranged from basic research to policy change. All participants in our study were unanimous on the need to reverse the 2012 IFHP as a major step. In fact, the federal government announced a more inclusive IFHP policy that went into effect on April 1, 2016 (Antonipillai et al. 2016). According to the new legislation, all humanitarian migrants have dental care benefits that cover the costs for basic and urgent dental treatment. As seen in previous government responses, however, this policy remains open to continual amendment. Other proposals to improve access to oral healthcare are similar to strategies currently discussed to address inequality in dental care access in Canada (Canadian Academy of Health Sciences 2014; Ruiz-Casares et al. 2016; Wallace et al. 2013).

Strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to provide insights into the dental care experiences of humanitarian migrants in Canada. The results are not intended to be generalizable as this is not the purpose of qualitative inquiry. The results are transferrable to similar urban settings within Canada given the IFHP funding policy on dental care is the same for all provinces and territories. The fact that the primary researcher was a dentist and an immigrant may have facilitated the establishment of trust with the participants, who reasoned that he was well placed to understand their challenges. Despite this advantage, however, we perceived frustration on the part of some participants who wished that he could directly provide dental care, which was beyond his abilities as a researcher.

Contribution

This study contributes to our understanding of access to the oral healthcare of humanitarian migrants. Participants included all categories of humanitarian migrants from a variety of source countries covering four geographical regions of the world. The qualitative design enabled participants to provide in-depth information based on lived experiences. These experiences derive from the use of a variety of dental service providers in Canada: private clinics, hospitals, and philanthropic organizations. Therefore, the diversity of participants, sources of experience, and methods of data collection enhance the potential for transferability of our results to other settings in Canada and abroad.

Conclusion

Our findings provide insights into the oral health consequences of the 2012 IFHP policy reform. The exclusion of dental care benefits for most humanitarian migrants exacerbated the vulnerability of the population to poor oral health. Humanitarian migrants in this study experienced inadequate oral healthcare, and their lived experiences help us to identify gaps in provision of oral care services. There is great potential to improve oral health for humanitarian migrants. For this to happen, stakeholders and policy makers must listen to the voices of this population.

Compliance with ethical standards

The McGill Institutional Review Board approved the study. IRB Study Number A01-B07-15A

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Antonipillai, V., Baumann, A., Hunter, A., et al. (2016; [Epub ahead of print]). Health inequity and “restoring fairness” through the Canadian refugee health policy reforms: A literature review. J Immigr Minor Health. 10.1007/s10903-016-0486-z. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Calvasina, P. (2014). Examining the oral health, access to dental care and transnational dental care utilization of adult immigrants: Analysis of the longitudinal survey of immigrants to Canada (2001–2005). (thesis): Graduate Department of Dentistry, University of Toronto.

- Canadian Academy of Health Sciences . Improving access to oral health care for vulnerable people living in Canada. Ottawa, Canada: Canadian Academy of Health Sciences; 2014. p. 91. [Google Scholar]

- Ghiabi E, Matthews DC, Brillant MS. The oral health status of recent immigrants and refugees in Nova Scotia, Canada. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2014;16(1):95–101. doi: 10.1007/s10903-013-9785-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Government of Canada. (2017). Statistics and Open Data. available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/corporate/reports-statistics/statistics-open-data.html. Accessed 30 April 2018.

- Government of Canada. (2018a). Interim Federal Health Program: Summary of coverage. Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/services/refugees/help-within-canada/health-care/interim-federal-health-program/coverage-summary.html. Accessed 8 March 2018.

- Government of Canada. (2018b). Glossary. Available at: http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/helpcentre/glossary.asp. Accessed 15 Nov 2018. 2018.

- Grembowski D, Andersen RM, Chen M. A public health model of the dental care process. Medical Care Review. 1989;46(4):439–496. doi: 10.1177/107755878904600405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groleau D, Young A, Kirmayer LJ. The McGill Illness Narrative Interview (MINI): An interview schedule to elicit meanings and modes of reasoning related to illness experience. Transcult Psychiatry. 2006;43(4):671–691. doi: 10.1177/1363461506070796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris HP, Zuberi D. Harming refugee and Canadian health: The negative consequences of recent reforms to Canada’s Interim Federal Health Program. Int Migration & Integration. 2015;16(4):1041–1055. doi: 10.1007/s12134-014-0385-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Higginbottom GM, Pillay JJ, Boadu NY. Guidance on performing focused ethnographies with an emphasis on healthcare research. Qual Rep. 2013;18(17):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, R. (2014). RQDA: R-based Qualitative Data Analysis. Available at: http://rqda.r-forge.r-project.org/. Accessed 15 March 2015. [program]. 0.2–7. version.

- Keboa, M. T., Hiles, N., & Macdonald, M. E. (2016). The oral health of refugees and asylum seekers: a scoping review. Globalization and Health, 12, 59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Khoo SE. Health and humanitarian migrants’ economic participation. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2010;12(3):327–339. doi: 10.1007/s10903-007-9098-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoblauch H. Focused ethnography. Qualitative Health Research. 2005;6:44. [Google Scholar]

- Lévesque, M., & Bedos, C. (2012). “Listening to each other”: a project to improve relationships with underserved members of our society. Journal of the Canadian Dental Association, 77(c20). [PubMed]

- Linden GJ, Lyons A, Scannapieco FA. Periodontal systemic associations: review of the evidence. Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 2013;84(4):S8–s19. doi: 10.1902/jop.2013.1340010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loignon C, Allison P, Landry A, et al. Providing humanistic care: dentists’ experiences in deprived areas. Journal of Dental Research. 2010;89(9):991–995. doi: 10.1177/0022034510370822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald, M. E., Beaudin, A., & Pineda, C. (2015). What do patients think about dental services in Quebec? Analysis of a dentist rating website. Journal of the Canadian Dental Association, 81(f3) [published Online First: 2015/06/02]. [PubMed]

- Manjikian L. Refugee narratives in Montreal: Negotiating everyday social exclusion and inclusion, Montreal: Department of Art History and Communication Studies, McGill University,Montreal. Montreal: McGill University; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Merry LA, Gagnon AJ, Kalim N, et al. Refugee claimant women and barriers to health and social services post-birth. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2011;102(4):286–290. doi: 10.1007/BF03404050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael CA, Dominey-Howes D, Labbate M. The antimicrobial resistance crisis: causes, consequences, and management. Frontiers in Public Health. 2014;2:145. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2014.00145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller J, Singhal S, Al-Dajani M, et al. Assessing the relationship between dental appearance and the potential for discrimination in Ontario, Canada. SSM -Population Health. 2015;1:26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2015.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogunbodede EO, Mickenautsch S, Rudolph MJ. Oral health care in refugee situations: Liberian refugees in Ghana. Journal of Refugee Studies. 2000;13(3):328–335. doi: 10.1093/jrs/13.3.328. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pitt RS, Sherman J, Macdonald ME. Low-income working immigrant families in Quebec: Exploring their challenges to well-being. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2016;106(8):e539–e545. doi: 10.17269/CJPH.106.5028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramraj C, Sadeghi L, Lawrence HP, et al. Is accessing dental care becoming more difficult? Evidence from Canada’s middle-income population. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(2):e57377. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redditt VJ, Janakiram P, Graziano D, et al. Health status of newly arrived refugees in Toronto, Ont: Part 1: infectious diseases. Canadian Family Physician. 2015;61(7):e303–e309. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reza M, Amin M, Sgro A, et al. Oral health status of immigrant and refugee children in North America: A scoping review. J Can Dent Assoc. 2016;82:g3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Casares, M., Cleveland, J., Oulhote, Y., et al. (2016). Knowledge of healthcare coverage for refugee claimants: Results from a survey of health service providers in Montreal. PLoS One. 10.1371/journal.pone.0146798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wallace B, MacEntee M, Harrison R, et al. Community dental clinics: providers’ perspectives. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2013;41(3):193–203. doi: 10.1111/cdoe.12012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]