Abstract

Objective

The benefit of organized breast assessment on wait times to treatment among asymptomatic women is unknown. The Ontario Breast Screening Program (OBSP) offers screening and organized assessment through Breast Assessment Centres (BAC). This study compares wait times across the treatment pathway among screened women diagnosed with breast cancer through BAC and usual care (UC).

Methods

A retrospective design identified two concurrent cohorts of postmenopausal women aged 50–69 within the OBSP diagnosed with screen-detected invasive breast cancer and assessed in BAC (n = 2010) and UC (n = 1844) between 2002 and 2010. Demographic characteristics were obtained from the OBSP. Medical chart abstraction provided prognostic and treatment data. Multinomial logistic regression examined associations of assessment type with wait times from abnormal mammogram to surgery, chemotherapy or radiotherapy.

Results

Compared with through UC, postmenopausal women diagnosed through BAC were significantly less likely to have longer wait times (days) from an abnormal mammogram to definitive surgery (> 89 vs. ≤ 47; OR = 0.63; 95% CI = 0.52–0.77), from final surgery to radiotherapy (> 88 vs. ≤ 55; OR = 0.71; 95% CI = 0.54–0.93) and from final chemotherapy to radiotherapy (> 41 vs. ≤ 28; OR = 0.52; 95% CI = 0.36–0.76). Conversely, women assessed through BAC compared with through UC were more likely to experience longer wait times from final surgery to chemotherapy (> 64 vs. ≤ 40; OR = 1.49; 95% CI = 1.04–2.14).

Conclusion

Shorter wait times to most treatments for postmenopausal women diagnosed in BAC further supports that women with an abnormal mammogram should be managed through organized assessment. Continued evaluation of factors influencing wait times to treatment is essential for quality improvement and patient outcomes.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Organized breast assessment, Treatment wait times, Surgery, Chemotherapy, Radiotherapy

Résumé

Objectif

On ignore si l’évaluation organisée de la santé du sein réduit les délais d’attente de traitement des femmes asymptomatiques. Le Programme ontarien de dépistage du cancer du sein (PODCS) offre le dépistage et l’évaluation organisée dans des centres d’évaluation de la santé du sein (CÉSS). Notre étude compare les délais d’attente selon la voie de traitement pour les femmes ayant subi un dépistage et reçu un diagnostic de cancer du sein dans des CÉSS ou par les soins habituels (SH).

Méthode

Un protocole rétrospectif a permis de définir au sein du PODCS deux cohortes parallèles de femmes postménopausées âgées de 50 à 69 ans atteintes d’un cancer invasif du sein détecté par dépistage et évaluées dans des CÉSS (n = 2 010) et par les SH (n = 1 844) entre 2002 et 2010. Leurs caractéristiques démographiques ont été extraites du PODCS. Un résumé analytique des dossiers médicaux a fourni les données de pronostic et de traitement. Par régression logistique multinomiale, nous avons examiné les associations entre le type d’évaluation et les délais d’attente entre une mammographie anormale et la chirurgie, la chimiothérapie ou la radiothérapie.

Résultats

Comparativement à celles ayant reçu un diagnostic par les soins habituels, les femmes postménopausées ayant reçu un diagnostic dans un centre d’évaluation de la santé du sein étaient significativement moins susceptibles d’avoir enduré des délais d’attente plus longs (en jours) entre une mammographie anormale et la chirurgie définitive (> 89 c. ≤ 47; RC = 0,63; IC de 95 % = 0,52-0,77), entre la dernière chirurgie et la radiothérapie (> 88 c. ≤ 55; RC = 0,71; IC de 95 % = 0,54-0,93) et entre la dernière chimiothérapie et la radiothérapie (> 41 c. ≤ 28; RC = 0,52; IC de 95 % = 0,36-0,76). À l’inverse, les femmes évaluées dans les CÉSS étaient plus susceptibles que celles évaluées par les soins habituels d’avoir enduré des délais d’attente plus longs entre la dernière chirurgie et la chimiothérapie (> 64 c. ≤ 40; RC = 1,49; IC de 95 % = 1,04-2,14).

Conclusion

Les délais d’attente plus courts avant la plupart des traitements chez les femmes postménopausées ayant reçu un diagnostic dans un centre d’évaluation de la santé du sein constituent une preuve supplémentaire que les femmes ayant subi une mammographie anormale devraient être prises en charge par un programme d’évaluation organisé. Il est essentiel de poursuivre l’analyse des facteurs qui influent sur les délais d’attente de traitement pour améliorer la qualité des soins et l’issue pour les patientes.

Mots-clés: Cancer du sein, Évaluation organisée de la santé du sein, Délais d’attente de traitement, Chirurgie, Chimiothérapie, Radiothérapie

Introduction

The improved survival for women diagnosed with breast cancer has been attributed to a combination of early detection through mammography screening and advances in evidence-based treatment protocols (Canadian Cancer Society’s Steering Committee. Canadian Cancer Statistics 2011). Despite improved survival outcomes, wait times across the breast cancer treatment pathway remain a concern. Studies have found that wait times greater than 12 weeks from an abnormal mammogram to definitive surgery are associated with decreased disease-free and cause-specific survival among women with early stage breast cancer (Vujovic et al. 2009). Delays of longer than 8 weeks (Huang et al. 2003) or delays of each additional month (Chen et al. 2008) to initiation of postoperative radiotherapy were associated with higher local recurrence rates, but not survival. However, a large Canadian study found that women waiting longer than 20 weeks for postoperative radiotherapy had higher recurrence rates and inferior breast-specific survival, compared with those who began within 4–8 weeks (Olivotto et al. 2009). Early initiation of postoperative chemotherapy improves overall survival for early stage breast cancer (Balduzzi et al. 2010). Similarly, a Canadian study found that women who received adjuvant chemotherapy earlier than 12 weeks after surgery had improved survival (Lohrisch et al. 2006). For radiotherapy postchemotherapy, risk of mortality was reduced when radiotherapy was given within 6 months of starting chemotherapy (Whelan et al. 2000).

Few studies have examined factors associated with variation in treatment wait times among asymptomatic women diagnosed with breast cancer. In Nova Scotia, Canada, women with stage I breast cancer experienced longer wait times from clinical or mammographic detection to initiation of adjuvant therapy compared with those with more advanced disease (Rayson et al. 2004). Our previous study found that stage did not influence wait times to postoperative adjuvant therapy in either symptomatic or asymptomatic women (Plotogea et al. 2013). However, earlier stage was associated with shorter wait times from chemotherapy to radiotherapy among symptomatic women in another Ontario study (Benk et al. 2006). In two Canadian studies, including ours, wait times to postoperative adjuvant therapy were substantially longer for symptomatic women diagnosed more recently compared with those diagnosed earlier (Plotogea et al. 2013; Rayson et al. 2007). Similar delays for women diagnosed more recently were also observed in the United States among symptomatic women 65 or older for initiation of postoperative radiotherapy (Punglia et al. 2010).

The Ontario Breast Assessment Collaborative Group was established in 1998 to guide development of coordinated multidisciplinary approaches for facilities to provide organized breast assessment, resulting in the establishment of Breast Assessment Centres (BAC) (Ontario Breast Screening Program 2001). Our recent studies found that women assessed through BAC have shorter wait times to breast cancer diagnosis, and fewer, timelier, more appropriate assessment procedures compared with women seen through usual care (UC) (Chiarelli et al. 2017). Women with stage I screen-detected breast cancer assessed through BAC also have a reduced risk of all-cause mortality compared with those assessed through UC (Smith et al. 2018). Given these earlier findings and that BAC provide a more streamlined work-up and referral process for diagnosis, assessing the impact on subsequent breast cancer treatment wait times is important. To our knowledge, no studies to date have examined how organized breast assessment may influence treatment wait times among asymptomatic women.

This study compared wait times across phases of the breast cancer treatment pathway (from abnormal screen to definitive surgery, final surgery to chemotherapy or radiotherapy, final chemotherapy to radiotherapy) between concurrent cohorts of postmenopausal women aged 50–69 screened in the Ontario Breast Screening Program (OBSP) undergoing assessment through BAC and UC and diagnosed with invasive breast cancer. Comparisons in treatment wait times were also examined by stage and diagnosis period.

Methods

Study population

The study population has been previously described (Chiarelli et al. 2017; Smith et al. 2018). Briefly, the OBSP has been established since 1990 to provide a population-based breast screening program to eligible women (Chiarelli et al. 2013). Women are ineligible if they have a history of breast cancer, acute breast symptoms or current breast implants. Women aged 50–69 screened through the OBSP with an abnormal mammogram from January 1, 2002 to December 31, 2009 and diagnosed with breast cancer were identified. Although all women in the study were screened at an OBSP centre, assessment referral was dependent on whether the screening centre was affiliated with BAC. Women were followed prospectively to a definitive diagnosis. During the study period, women were screened at 150 OBSP centres and evaluated at 35 BAC.

Women with an abnormal mammogram underwent diagnostic assessment either through BAC or UC. Ontario facilities that provide organized assessment must meet established criteria to qualify as BAC. Criteria include: providing all abnormal mammographic work-up, including special mammographic views, ultrasound and image-guided core biopsy; providing radiological, surgical and pathologic consultation with experts in breast evaluation; and providing a navigator for patient support and referral coordination. BAC may either perform all the required services for abnormal mammographic work-up or establish networks with facilities to provide services (Quan et al. 2012). For women seen through UC, further diagnostic imaging after an abnormal mammogram is arranged directly from the screening centre and/or through their physician; results must be communicated to the physician, who is then responsible for arranging any further imaging or necessary biopsies and/or surgical consultation. Breast cancer treatment location is unrelated to where a woman had her breast assessment. The study was approved by the University of Toronto Research Ethics Board, and informed consent was not required.

Selection of breast cancer cases

To allow for learning curves for new BAC, only women with an abnormal mammogram assessed after 6 months of operation were selected (Jaro 1995). All postmenopausal women diagnosed with invasive breast cancers of any histological type detected within 12 months of an abnormal rescreen and classified as screen-detected by the program during follow-up were included. Women were excluded if they were premenopausal, a non-Ontario resident, treatment location was unknown, received treatment at a hospital with less than 15 eligible cases, or had bilateral or non-primary breast cancers that were detected on initial screens, diagnosed > 1 year after an abnormal screen or stage IV.

Data sources

Demographic and risk factor information were obtained from the Integrated Client Management System (ICMS) of the OBSP. Additional risk factor data, prognostic and treatment information were obtained from chart abstraction at regional cancer centres, which are specialized centres in Ontario that deliver all cancer radiotherapy; patients may also be referred for diagnostic work-up, systemic therapy and/or treatment planning. These centres maintain detailed patient charts about diagnostic and treatment information for care received at other institutions. A local collaborator was identified for each centre (n = 13) to facilitate chart abstraction and to obtain Research Ethics Board approval. Trained abstractors reviewed paper and electronic medical charts and used a standardized abstraction form to abstract relevant data.

Demographics and risk factors

Diagnosis age and year were recorded. Women’s postal code of residence at screening was linked to the 2006 Canadian Census to obtain income quintiles (Q1 (low)–Q5 (high)) and community status (Statistics Canada 2014). Community status was dichotomized into urban (population 10,000+) and non-urban, which included rural (< 10,000 and a strong metropolitan-influenced zone (MIZ)), rural remote (< 10,000 and a moderate MIZ) and rural very remote (< 10,000 and a weak/no MIZ) (Statistics Canada 2014).

Prognostic characteristics

Stage was coded using the TNM classification scheme (6th ed.) (American Joint Committee on Cancer 2002). Estrogen, progesterone and HER2 protein receptors were coded as positive or negative; women who were negative for all three receptors were categorized as triple negative (Hammond et al. 2010; Wolff et al. 2007).

Wait times and treatment characteristics

Date of abnormal screening mammogram prior to diagnosis for each woman was obtained through the ICMS. Treatment dates were abstracted from medical charts. Wait times (in days) were examined across four phases in the treatment pathway: abnormal screening mammogram to definitive surgery (phase 1), final surgery to first chemotherapy (phase 2), final surgery to first radiotherapy without chemotherapy (phase 3) and final chemotherapy to first radiotherapy (phase 4). A definitive surgery was defined as the date of either partial mastectomy, modified radical mastectomy or total mastectomy and included surgeries occurring within 4 months of a tissue diagnosis. For women who underwent multiple surgeries (n = 204; 5.3% of cohort), the later surgery date was chosen as the date of definitive surgery. Final surgery was defined as the date of the last procedure before adjuvant treatment categorized as either partial mastectomy, modified radical mastectomy, total mastectomy, axillary node dissection or sentinel lymph node biopsy. Wait time to postoperative adjuvant treatment was calculated from the date of final surgery following diagnosis to the date of first adjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy. Adjuvant treatment included those occurring within 1 year of diagnosis. Receipt of adjuvant therapy for the primary diagnosis was dichotomized as ‘yes’ or ‘no’. Hospital type where the woman had surgery was categorized as either ‘academic’ or ‘community hospital’. Treatment centre region was grouped according to the regional cancer centre a woman first attended (South-Central, South-Eastern, South-Western and Northern) (Plotogea et al. 2013).

Statistical analysis

Demographic, prognostic and treatment characteristics were compared between BAC and UC using multivariable logistic regression to estimate adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For each treatment phase, wait times were summarized by the median, interquartile range (IQR) and ninetieth (90th) percentile. Comparisons of wait times between BAC and UC were performed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum tests (Haynes 2013). Wait times were categorized by quartiles calculated for all women for each treatment phase, with the first quartile as the referent group. Multinomial logistic regression examined associations between assessment type, stage and diagnosis period and wait times. Adjusted ORs and corresponding 95% CIs were estimated to quantify associations. Statistical tests were two-sided and evaluated at a 5% significance level. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc 2013).

Results

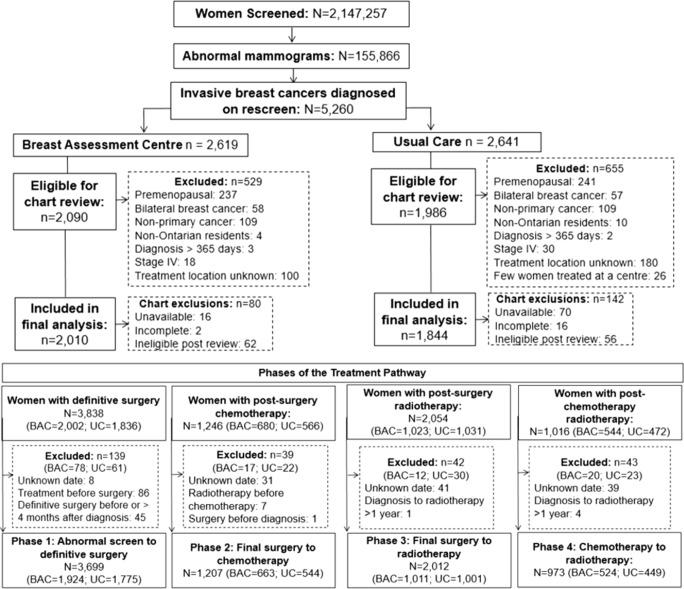

Of the 155,866 women with an abnormal mammogram, 5260 (3.4%) were diagnosed with an invasive breast cancer on a rescreen (Fig. 1). After excluding n = 1184 women who did not meet our inclusion criteria, 4076 women were eligible for chart review. Among these women, 86 medical charts were unavailable, 18 were incomplete and 118 were ineligible after chart review. The final sample consisted of 2010 postmenopausal women (52.2%) assessed through BAC and 1844 (47.8%) through UC. For treatment phases, 3699 women were included in the abnormal mammogram to definitive surgery phase 1 analysis, 1207 women in the final surgery to chemotherapy phase 2 analysis, 2012 women in the final surgery to radiotherapy phase 3 analysis, and 973 women in the final chemotherapy to radiotherapy phase 4 analysis.

Fig. 1.

Cohort of women aged 50–69 diagnosed with invasive breast cancer within the Ontario Breast Screening Program (OBSP) between January 1, 2002 and December 31, 2010 and included in the treatment pathway analysis according to Breast Assessment Centre (BAC) and usual care (UC)

Women assessed in BAC compared with UC were more likely to be diagnosed after 2006 than before (OR = 1.32; 95% CI 1.15–1.50), more likely to live in non-urban regions (OR = 1.23; 95% CI 1.04–1.46), more likely to have been seen at an academic centre for surgery (OR = 7.73; 95% CI 6.64–9.01), and more likely to have a total mastectomy as their definitive (OR = 1.78; 95% CI 1.33–2.40) and final surgery (OR = 1.46; 95% CI 1.15–1.86) (Table 1). Women assessed in BAC compared with UC were less likely to receive radiotherapy (OR = 0.79; 95% CI 0.67–0.93) and to receive treatment outside the South-Central region.

Table 1.

Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for demographic characteristics, risk factors and prognostic characteristics among postmenopausal women diagnosed with screen-detected breast cancers through a Breast Assessment Centre versus through usual care

| Breast assessment type | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Usual care N = 1844 n (%) |

Breast Assessment Centre N = 2010 n (%) |

Overall N = 3854 n (%) |

Adjusted ORa (95% CI) |

| Demographic and risk factors | ||||

| Age at diagnosis (years) | ||||

| 50–59 | 656 (35.6) | 707 (35.2) | 1363 (35.4) | 1.00 (Ref.) |

| 60–69 | 1188 (64.4) | 1303 (64.8) | 2491 (64.6) | 1.01 (0.89–1.16) |

| Period of diagnosis | ||||

| 2002–2005 | 692 (37.5) | 630 (31.3) | 1322 (34.3) | 1.00 (Ref.) |

| 2006–2010 | 1152 (62.5) | 1380 (68.7) | 2532 (65.7) | 1.32 (1.15–1.50) |

| Community status | ||||

| Urban | 1548 (84.0) | 1630 (81.1) | 3178 (82.5) | 1.00 (Ref.) |

| Non-urban | 294 (16.0) | 380 (18.9) | 674 (17.6) | 1.23 (1.04–1.46) |

| Missing | 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| Income quintile | ||||

| 1—Lowest | 305 (16.7) | 361 (18.1) | 666 (17.4) | 1.00 (Ref.) |

| 2 | 347 (19.0) | 396 (19.8) | 743 (19.4) | 0.96 (0.78–1.18) |

| 3 | 360 (19.7) | 403 (20.2) | 763 (19.9) | 0.94 (0.77–1.16) |

| 4 | 365 (19.9) | 385 (19.3) | 750 (19.6) | 0.89 (0.73–1.10) |

| 5—Highest | 454 (24.8) | 455 (22.8) | 909 (23.7) | 0.85 (0.69–1.04) |

| Missing | 13 | 10 | 23 | |

| Prognostic factors | ||||

| Stage at diagnosis | ||||

| Stage I | 1177 (65.4) | 1299 (65.8) | 2476 (65.6) | 1.00 (Ref.) |

| Stage II/III | 624 (34.6) | 674 (34.2) | 1298 (34.4) | 0.97 (0.85–1.11) |

| Missing | 43 | 37 | 80 | |

| Triple negative | ||||

| No | 1623 (91.5) | 1761 (91.5) | 3384 (91.5) | 1.00 (Ref.) |

| Yes | 150 (8.5) | 164 (8.5) | 314 (8.5) | 0.99 (0.78–1.25) |

| Missing | 71 | 85 | 156 | |

| Treatment characteristics | ||||

| Hospital type | ||||

| Community hospital | 1498 (81.8) | 756 (38.0) | 2254 (59.0) | 1.00 (Ref.) |

| Academic centre | 334 (18.2) | 1231 (62.0) | 1565 (41.0) | 7.73 (6.64–9.01) |

| Missing | 12 | 23 | 35 | |

| Definitive surgery typeb | ||||

| Partial mastectomy | 1526 (83.1) | 1590 (79.3) | 3116 (81.2) | 1.00 (Ref.) |

| Modified radical mastectomy | 239 (13.0) | 276 (13.8) | 515 (13.4) | 1.13 (0.94–1.36) |

| Total mastectomy | 71 (3.9) | 136 (6.8) | 207 (5.4) | 1.78 (1.33–2.40) |

| None | 4 | 3 | 7 | – |

| Missing | 4 | 5 | 9 | |

| Final surgery typeb,c | ||||

| Partial mastectomy | 1224 (66.7) | 1283 (64.0) | 2507 (65.3) | 1.00 (Ref.) |

| Modified radical mastectomy | 236 (12.8) | 270 (13.4) | 506 (13.1) | 1.11 (0.92–1.35) |

| Total mastectomy | 121 (6.6) | 188 (9.4) | 309 (8.0) | 1.46 (1.15–1.86) |

| ALND/SLNB | 255 (13.9) | 265 (13.2) | 520 (13.5) | 1.00 (0.86–1.12) |

| Other | 1 | 2 | 3 | – |

| None | 3 | 2 | 5 | – |

| Missing | 4 | 0 | 4 | |

| Chemotherapy | ||||

| No | 1125 (61.8) | 1231 (61.8) | 2356 (61.8) | 1.00 (Ref.) |

| Yes | 696 (38.2) | 761 (38.2) | 1457 (38.2) | 0.99 (0.87–1.13) |

| Missing | 23 | 18 | 41 | |

| Radiotherapy | ||||

| No | 299 (16.3) | 394 (19.7) | 693 (18.1) | 1.00 (Ref.) |

| Yes | 1533 (83.7) | 1610 (80.3) | 3143 (81.9) | 0.79 (0.67–0.93) |

| Missing | 12 | 6 | 18 | |

| Radiotherapyb | ||||

| No | ||||

| Partial mastectomy | 92 (30.8) | 100 (25.6) | 192 (27.8) | 1.00 (Ref.) |

| Modified radical mastectomy | 151 (50.5) | 180 (46.0) | 331 (47.8) | 1.12 (0.78–1.61) |

| Total mastectomy | 53 (17.7) | 109 (27.9) | 162 (23.5) | 1.85 (1.20–2.86) |

| Yes | ||||

| Partial mastectomy | 1424 (93.1) | 1487 (92.5) | 2911 (92.8) | 1.00 (Ref.) |

| Modified radical mastectomy | 87 (5.7) | 94 (5.9) | 181 (5.8) | 1.03 (0.76–1.39) |

| Total mastectomy | 17 (1.1) | 26 (1.6) | 43 (1.4) | 1.37 (0.74–2.54) |

| Treatment centre region | ||||

| South-Central | 1131 (61.3) | 727 (36.2) | 1858 (48.2) | 1.00 (Ref.) |

| South-Eastern | 170 (9.2) | 548 (27.3) | 718 (18.6) | 5.32 (4.36–6.49) |

| South-Western | 289 (15.7) | 457 (22.7) | 746 (19.4) | 2.52 (2.11–3.00) |

| Northern | 254 (13.8) | 278 (13.8) | 532 (13.8) | 1.78 (1.47–2.17) |

aAdjusted by age at diagnosis and/or period of diagnosis

bPartial mastectomy = partial mastectomy with or without axillary node dissection or sentinel lymph node biopsy on the same day; modified radical mastectomy = modified radical mastectomy with or without sentinel lymph node biopsy on the same day or total mastectomy with axillary node dissection on the same day; total mastectomy = total mastectomy with sentinel lymph node biopsy on the same day

cAxillary lymph node dissection (ALND)/sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) performed on separate day from other procedures

Among all women, the median wait time was 65 days (IQR = 47–89 days) from an abnormal mammogram to definitive surgery, 51 days (IQR = 40–64 days) from surgery to chemotherapy, 70 days (IQR = 55–88 days) from surgery to radiotherapy, and 33 days (IQR = 28–41 days) from chemotherapy to radiotherapy (Table 2). Median wait times were significantly shorter in BAC versus UC, except from final surgery to chemotherapy (54 vs. 49 days).

Table 2.

Median wait times (in days), interquartile range and 90th percentile to definitive surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy overall, and among postmenopausal women diagnosed with screen-detected breast cancers through a Breast Assessment Centre versus through usual care

| Overall | Usual care | Breast Assessment Centre | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 3854 | N = 1844 | N = 2010 | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Treatments receiveda | |||

| Surgery + chemotherapy | 242 (6.4) | 102 (5.6) | 140 (7.0) |

| Surgery + radiotherapy | 1907 (50.3) | 931 (51.6) | 976 (49.1) |

| Surgery + chemotherapy + radiotherapy | 1203 (31.7) | 583 (32.3) | 620 (31.2) |

| Surgery only | 441 (11.6) | 190 (10.5) | 251 (12.6) |

| Missing | 61 | 38 | 23 |

| Abnormal screen to definitive surgeryb | |||

| Number in analysis | 3699 | 1775 | 1924 |

| Median wait time to definitive surgery | 65 | 67 | 63 |

| Interquartile range | 47–89 | 47–91 | 47–85 |

| > 90th Percentile | 117 | 123 | 112 |

| Final surgery to chemotherapyc | |||

| Number in analysis | 1207 | 544 | 663 |

| Median wait time to chemotherapy | 51 | 49 | 54 |

| Interquartile range | 40–64 | 37–62 | 42–65 |

| > 90th percentile | 76 | 74 | 77 |

| Final surgery to radiotherapyd | |||

| Number in analysis | 2012 | 1001 | 1011 |

| Median wait time to radiotherapy | 70 | 71 | 69 |

| Interquartile range | 55–88 | 55–91 | 55–84 |

| > 90th percentile | 114 | 125 | 107 |

| Final chemotherapy to radiotherapye | |||

| Number in analysis | 973 | 449 | 524 |

| Median wait time to radiotherapy | 33 | 33 | 32 |

| Interquartile range | 28–41 | 28–41 | 27–40 |

| > 90th percentile | 55 | 56 | 53 |

aPearson chi-squared test; difference in treatments received for BAC compared with UC (p = 0.0463)

bWilcoxon rank sum test; difference in wait times for BAC compared with UC (p = 0.0289)

cWilcoxon rank sum test; difference in wait times for BAC compared with UC (p < 0.0001)

dWilcoxon rank sum test; difference in wait times for BAC compared with UC (p = 0.0028)

eWilcoxon rank sum test; difference in wait times for BAC compared with UC (p = 0.0068)

Women assessed through BAC compared with UC were less likely to experience longer wait times in the fourth compared with first quartile from an abnormal mammogram to definitive surgery (> 89 vs. ≤ 47 days; OR = 0.63) and from surgery to radiotherapy (> 88 vs. ≤ 55 days; OR = 0.71) (Table 3). Women evaluated in BAC were also less likely to experience longer wait times in the second (29–33 days; OR = 0.63), third (34–41 days; OR = 0.68) and fourth quartiles (> 41 days; OR = 0.52) compared with first (≤ 28 days) from chemotherapy to radiotherapy. Conversely, compared with UC, women assessed through BAC were more likely to experience longer wait times in the fourth compared with first quartile from surgery to chemotherapy (> 64 vs. ≤ 40 days; OR = 1.49).

Table 3.

Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) describing factors associated with wait times (in days) from abnormal screen to definitive surgery, from final surgery to postoperative chemotherapy or postoperative radiotherapy and from final chemotherapy to radiotherapy

| Breast assessment type | Period of diagnosis | Stage | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usual care N (%) |

BAC N (%) |

Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

2002–2005 N (%) |

2006–2010 N (%) |

Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

I N (%) |

II/III N (%) |

Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

|

| Abnormal screen to definitive surgerya (n = 3699) | |||||||||

| ≤ 47 days | 456 (25.7) | 498 (25.9) | 1.00 (Ref.) | 395 (31.1) | 559 (23.0) | 1.00 (Ref.) | 568 (23.4) | 372 (30.7) | 1.00 (Ref.) |

| 48 to 65 days | 405 (22.8) | 525 (27.3) | 1.05 (0.86–1.27) | 337 (26.6) | 593 (24.4) | 1.26 (1.04–1.53) | 600 (24.7) | 316 (26.1) | 0.80 (0.66–0.97) |

| 66 to 89 days | 436 (24.6) | 472 (24.5) | 0.85 (0.70–1.03) | 275 (21.7) | 633 (26.1) | 1.67 (1.37–2.04) | 598 (24.7) | 293 (24.2) | 0.74 (0.60–0.89) |

| > 89 days | 478 (26.9) | 429 (22.3) | 0.63 (0.52–0.77) | 262 (20.7) | 645 (26.5) | 1.96 (1.60–2.39) | 660 (27.2) | 231 (19.1) | 0.52 (0.42–0.64) |

| Final surgery to first chemotherapyb (n = 1207) | |||||||||

| ≤ 40 days | 165 (30.3) | 140 (21.1) | 1.00 (Ref.) | 97 (25.4) | 208 (25.2) | 1.00 (Ref.) | 82 (20.6) | 222 (27.5) | 1.00 (Ref.) |

| 41 to 51 days | 145 (26.7) | 165 (24.9) | 1.26 (0.90–1.78) | 101 (26.4) | 209 (25.3) | 0.88 (0.61–1.27) | 101 (25.4) | 209 (25.9) | 0.84 (0.57–1.23) |

| 52 to 64 days | 125 (23.0) | 186 (28.1) | 1.39 (0.98–1.96) | 93 (24.4) | 218 (26.4) | 1.12 (0.77–1.62) | 100 (25.1) | 210 (26.0) | 0.82 (0.55–1.21) |

| > 64 days | 109 (20.0) | 172 (25.9) | 1.49 (1.04–2.14) | 91 (23.8) | 190 (23.0) | 0.92 (0.63–1.34) | 115 (28.9) | 166 (20.6) | 0.55 (0.37–0.81) |

| Final surgery to first radiotherapyc (n = 2012) | |||||||||

| ≤ 55 days | 261 (26.1) | 279 (27.6) | 1.00 (Ref.) | 147 (21.0) | 393 (30.0) | 1.00 (Ref.) | 467 (28.0) | 63 (21.0) | 1.00 (Ref.) |

| 56 to 70 days | 225 (22.5) | 276 (27.3) | 1.12 (0.86–1.46) | 148 (21.1) | 353 (26.9) | 0.92 (0.69–1.22) | 437 (26.2) | 54 (18.0) | 0.92 (0.62–1.36) |

| 71 to 88 days | 233 (23.3) | 239 (23.6) | 0.89 (0.68–1.16) | 184 (26.3) | 288 (22.0) | 0.60 (0.45–0.80) | 409 (24.5) | 56 (18.7) | 1.02 (0.69–1.52) |

| > 88 days | 282 (28.2) | 217 (21.5) | 0.71 (0.54–0.93) | 222 (31.7) | 277 (21.1) | 0.48 (0.36–0.63) | 354 (21.2) | 127 (42.3) | 2.48 (1.74–3.53) |

| Final chemotherapy to first radiotherapyd (n = 973) | |||||||||

| ≤ 28 days | 127 (28.3) | 198 (37.8) | 1.00 (Ref.) | 94 (30.8) | 231 (34.6) | 1.00 (Ref.) | 102 (32.9) | 223 (33.7) | 1.00 (Ref.) |

| 29 to 33 days | 110 (24.5) | 106 (20.2) | 0.63 (0.44–0.92) | 58 (19.0) | 158 (23.7) | 1.19 (0.80–1.76) | 69 (22.3) | 147 (22.2) | 0.99 (0.68–1.44) |

| 34 to 41 days | 101 (22.5) | 105 (20.0) | 0.68 (0.47–0.98) | 69 (22.6) | 137 (20.5) | 0.86 (0.58–1.26) | 63 (20.3) | 143 (21.6) | 1.03 (0.71–1.51) |

| > 41 days | 111 (24.7) | 115 (22.0) | 0.52 (0.36–0.76) | 84 (27.5) | 142 (21.3) | 0.79 (0.53–1.15) | 76 (24.5) | 149 (22.5) | 0.90 (0.62–1.31) |

BAC Breast Assessment Centre

aAdjusted for assessment pathway, age, period of diagnosis, treatment centre region, stage and definitive surgery type

bAdjusted for assessment pathway, age, period of diagnosis, treatment centre region, stage, final surgery type and triple negative status

cAdjusted for assessment pathway, age, period of diagnosis, treatment centre region, stage and final surgery type

dAdjusted for assessment pathway, age, period of diagnosis, treatment centre region and stage

Women diagnosed from 2006 to 2010 compared with from 2002 to 2005 were more likely to experience longer wait times in the second (48–65 days; OR = 1.26), third (66–89 days; OR = 1.67) and fourth quartiles (> 89 days; OR = 1.96) compared with first (≤ 47 days) from an abnormal mammogram to definitive surgery. However, they were less likely to experience longer wait times in the third (71–88 days; OR = 0.60) and fourth quartiles (> 88 days; OR = 0.48) compared with first from surgery to radiotherapy (Table 3).

Women with stage II/III compared with stage I breast cancers were less likely to have longer wait times in the second (48–65 days; OR = 0.80), third (66–89 days; OR = 0.74) and fourth quartiles (> 89 days; OR = 0.52) compared with first (≤ 47 days) from an abnormal mammogram to definitive surgery (Table 3). They were also less likely to have longer wait times in the fourth compared with first quartile from surgery to chemotherapy (> 64 vs. ≤ 40 days; OR = 0.55). Conversely, women with stage II/III breast cancer were more likely to experience longer wait times in the fourth compared with first quartile from final surgery to radiotherapy (> 88 vs. ≤ 55 days; OR = 2.48).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to examine how organized breast assessment impacts treatment wait times in a population-based cohort of asymptomatic women with screen-detected invasive breast cancer. In Ontario, postmenopausal women with an abnormal screening mammogram assessed through BAC experience reduced wait times to definitive surgery, from final surgery to radiotherapy, and from final chemotherapy to radiotherapy, but longer wait times from final surgery to chemotherapy.

An earlier study in Ontario found that delays longer than 12 weeks from an abnormal mammogram to definitive surgery were associated with decreased survival (Vujovic et al. 2009). In our cohort, 75% of women had their definitive surgery within 89 days (12.7 weeks) of their abnormal mammogram, and women evaluated in BAC compared with UC were significantly less likely to experience wait times longer than this. The reduced wait times to definitive surgery for women assessed through BAC might be explained by the multidisciplinary expertise, including surgical support, offered through these centres (Quan et al. 2012).

Our median wait time of 70 days (10.0 weeks) from surgery to radiotherapy is within those recommended by the Canadian Steering Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Care and Treatment of Breast Cancer (Whelan et al. 2003) and falls within the range of median wait times (63–84 days) reported in earlier Canadian studies (Olivotto et al. 2009; Benk et al. 2006). Women assessed in BAC were also significantly less likely to experience wait times longer than 88 days (12.6 weeks) to postoperative radiotherapy compared with women assessed through UC. An earlier Canadian study found that 23% of patients had intervals greater than 12 weeks from surgery to radiotherapy (Olivotto et al. 2009), compared with 22% in BAC and 28% in UC. In Canada, delays of longer than 20 weeks to postoperative radiotherapy, compared with 4–8 weeks, have been associated with higher recurrence rates and inferior breast-specific survival (Olivotto et al. 2009).

Median wait time from final surgery to chemotherapy was 51 days in our cohort, longer than the 43 days reported in our earlier study of Ontario women with screen-detected breast cancer (Plotogea et al. 2013). Longer wait times to chemotherapy in the current study may represent a temporal effect due to increased use of chemotherapy for node-negative breast cancer in recent years (Plotogea et al. 2013). Contrary to our findings for definitive surgery and postoperative radiotherapy, women assessed in BAC were significantly more likely to experience longer wait times to postoperative chemotherapy compared with women assessed in UC. This may be explained by our finding that more women assessed in BAC had total mastectomy as their final surgery and longer postoperative recovery could have delayed treatment initiation (Saint-Jacques et al. 2007). In addition, women assessed in BAC were more likely to have surgery at an academic centre and possibly more likely to be referred for further testing prior to chemotherapy initiation. An earlier Canadian study found that delays longer than 12 weeks to postoperative chemotherapy were associated with inferior survival (Lohrisch et al. 2006).

Another Canadian study has examined wait times from final chemotherapy to radiotherapy in symptomatic women and found a median wait time of 5.3 weeks, slightly longer than ours of 33 days (4.7 weeks) (Benk et al. 2006). Organized breast assessment had the greatest impact on wait times along this phase of the treatment pathway, with women evaluated in BAC significantly less likely to experience wait times longer than 28 days (4 weeks) compared with those evaluated in UC. This finding is unexpected since this treatment phase occurs furthest temporally from diagnostic assessment and completely within the cancer system and should be least impacted by diagnosis through BAC.

In our cohort, diagnosis period was associated with wait times from an abnormal mammogram to definitive surgery and to postoperative radiotherapy. More than half of women (53%) diagnosed with breast cancer from 2006 to 2010 waited longer than 65 days from an abnormal mammogram to surgery, compared with 42% of women diagnosed from 2002 to 2005. Longer wait times to definitive surgery may be due to the increase in breast cancer incidence (Canadian Cancer Society’s Steering Committee. Canadian Cancer Statistics 2011) and more complex imaging work-up and surgeries over time. Contrary to earlier studies (Rayson et al. 2007; Punglia et al. 2010), we found that wait times to postoperative radiotherapy were shorter for our more recent time period compared with the earlier one. A possible explanation for this discrepancy might be that earlier studies included mostly symptomatic women, and the US study only considered women aged 65 or older (Punglia et al. 2010). Since 2004, Cancer Care Ontario has been publicly reporting wait times to radiotherapy (Cancer Care Ontario 2010), and improved wait times from 2006 to 2010 might be attributable to better planning and new investments in regional cancer centres, radiation equipment and personnel initiated in the early 2000s. The shorter wait times to postoperative radiotherapy in BAC may be explained by our finding that women assessed in BAC were more likely to be diagnosed from 2006 to 2010, when wait times to radiotherapy were shorter.

The effect of stage on wait time from abnormal mammogram to definitive surgery has not been previously examined. In our cohort, women with stage II/III compared with stage I breast cancers were significantly less likely to wait longer than 47 days (6.7 weeks) for their definitive surgery. Contrary to our earlier Ontario study (Plotogea et al. 2013), stage also impacted wait times to postoperative chemotherapy, with significantly fewer women with stage II/III breast cancers having longer wait times (> 64 days or 9.1 weeks). Our observation of shorter wait times to definitive surgery and chemotherapy for higher stage cancers is consistent with the expedition of treatment of more severe cases observed in other Canadian provinces (Caplan et al. 2000). Unexpectedly, we found that women diagnosed with stage II/III breast cancer were more likely to experience wait times longer than 88 days (12.6 weeks) from surgery to radiotherapy. Although these women did not receive chemotherapy, they likely would have been referred for consideration of systemic therapy; the increased wait time to postoperative radiotherapy likely includes time for medical oncology consultation and further testing.

Strengths of this study include its use of data from a large population-based cohort of screened women with invasive breast cancer. Selection bias was limited, as women were assessed through BAC or UC by the affiliation of their OBSP screening site. We were also able to obtain detailed information on treatment dates and types through chart abstraction. There were also some limitations. Our results may not be generalizable to symptomatic or opportunistically screened women; however in Ontario, the majority of women aged 50–69 undergo breast cancer screening within the OBSP (Cancer Care Ontario 2016). The inclusion of premenopausal women and those with bilateral breast cancer may have also provided more generalizable results; however, there were very few in our cohort. As only rescreens (incident breast cancers) were included, treatment wait times may not apply to prevalent cancers. Although we measured and adjusted for differences in patient populations (i.e., period of diagnosis, treatment centre region), cohort designs are limited by non-randomization of exposure and adjustment may not have fully addressed these potential confounders. Additionally, patient and system-level factors that can influence wait times, such as patient beliefs and attitudes, logistical barriers to accessing treatment, delays in treatment seeking, appointment scheduling or availability of physicians, were not captured by our data.

Conclusion

Delays to breast cancer treatment are associated with increased risk of recurrence and reduced survival. Assessing factors influencing wait times along the breast cancer treatment pathway is important to identify areas for quality improvement, with the ultimate goal of improving patient outcomes. This study examined the impact of organized breast assessment on treatment wait times in a large cohort of asymptomatic postmenopausal women. With the exception of time to postoperative chemotherapy, women in BAC experienced shorter wait times to definitive surgery, postoperative radiotherapy and from chemotherapy to radiotherapy compared with women in UC. These results and those of our earlier studies (Chiarelli et al. 2017; Smith et al. 2018) further support that women with an abnormal mammogram should be managed through organized assessment.

Acknowledgements

We thank the study staff, Brittany Speller, Leanne Lindsay, Lucy Leon and Anjali Pandya. We also thank Jessie Cunningham for assisting in the literature search. We acknowledge Cancer Care Ontario for use of its data.

Funding information

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (grant number 130400). This agency had no involvement in the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, manuscript preparation or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Compliance with ethical standards

We can confirm that we have observed appropriate ethical guidelines and legislation in conducting the study. The study was approved by the University of Toronto Research Ethics Board (Protocol #29342), and informed consent was not required as there was no direct contact with women and the study falls within the ethical domain of non-consensual research. In addition, Research Ethics Board approval was obtained for each regional cancer centre for medical chart abstraction.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- American Joint Committee on Cancer . Cancer staging manual. 6. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Balduzzi A, Leonardi MC, Cardillo A, Orecchia R, Dellapasqua S, Iorfida M, et al. Timing of adjuvant systemic therapy and radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery and mastectomy. Cancer Treatment Reviews. 2010;36(6):443–450. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2010.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benk V, Przybysz R, McGowan T, Paszat L. Waiting times for radiation therapy in Ontario. Canadian Journal of Surgery. 2006;49(1):16–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Cancer Society’s Steering Committee. Canadian Cancer Statistics . Toronto. ON: Canadian Cancer Society; 2011. p. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cancer Care Ontario. (2010).Wait Times. from: http://www.cancercare.on.ca/cms/One.aspx?portalId=1377&pageId=8836. Accessed 04/29/2013, 2013.

- Cancer Care Ontario. (2016). Ontario Cancer Screening Performance Report 2016. Toronto.

- Caplan LS, May DS, Richardson LC. Time to diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer: Results from the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program, 1991-1995. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90(1):130–134. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.90.1.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, King W, Pearcey R, Kerba M, Mackillop WJ. The relationship between waiting time for radiotherapy and clinical outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. Radiotherapy and Oncology. 2008;87(1):3–16. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2007.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiarelli AM, Edwards SA, Prummel MV, Muradali D, Majpruz V, Done SJ, et al. Digital compared with screen-film mammography: performance measures in concurrent cohorts within an organized breast screening program. Radiology. 2013;268(3):684–693. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13122567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiarelli, A. M., Muradali, D., Blackmore, K. M., Smith, C. R., Mirea, L., Majpruz, V., et al. (2017). Evaluating wait times from screening to breast cancer diagnosis among women undergoing organised assessment vs usual care. British Journal of Cancer, 116(10), 1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hammond ME, Hayes DF, Dowsett M, Allred DC, Hagerty KL, Badve S, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists guideline recommendations for immunohistochemical testing of estrogen and progesterone receptors in breast cancer (unabridged version) Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine. 2010;134(7):e48–e72. doi: 10.5858/134.7.e48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes W. Encyclopedia of Systems Biology. Berlin: Springer; 2013. Wilcoxon rank sum test; pp. 2354–2355. [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Barbera L, Brouwers M, Browman G, Mackillop WJ. Does delay in starting treatment affect the outcomes of radiotherapy? A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2003;21(3):555–563. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaro MA. Probabilistic linkage of large public health data files. Statistics in Medicine. 1995;14(5–7):491–498. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780140510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohrisch C, Paltiel C, Gelmon K, Speers C, Taylor S, Barnett J, et al. Impact on survival of time from definitive surgery to initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy for early-stage breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24(30):4888–4894. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.6089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivotto IA, Lesperance ML, Truong PT, Nichol A, Berrang T, Tyldesley S, et al. Intervals longer than 20 weeks from breast-conserving surgery to radiation therapy are associated with inferior outcome for women with early-stage breast cancer who are not receiving chemotherapy. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27(1):16–23. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.1891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ontario Breast Screening Program . Multidisciplinary Roles and Expectations for Breast Assessment in Ontario. Toronto: The Breast Assessment Collaborative Group; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Plotogea, A., Chiarelli, A. M., Mirea, L., Prummel, M. V., Chong, N., Shumak, R. S., et al. (2013). Factors associated with wait times across the breast cancer treatment pathway in Ontario. SpringerPlus, 2(1), 388. 10.1186/2193-1801-2-388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Punglia RS, Saito AM, Neville BA, Earle CC, Weeks JC. Impact of interval from breast conserving surgery to radiotherapy on local recurrence in older women with breast cancer: retrospective cohort analysis. Bmj. 2010;340:c845. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quan ML, Shumak RS, Majpruz V, Holloway CM, O’Malley FP, Chiarelli AM. Improving work-up of the abnormal mammogram through organized assessment: results from the ontario breast screening program. Journal of Oncology Practice/ American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2012;8(2):107–112. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayson D, Chiasson D, Dewar R. Elapsed time from breast cancer detection to first adjuvant therapy in a Canadian province, 1999-2000. CMAJ. 2004;170(6):957–961. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1020972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayson D, Saint-Jacques N, Younis T, Meadows J, Dewar R. Comparison of elapsed times from breast cancer detection to first adjuvant therapy in Nova Scotia in 1999/2000 and 2003/04. CMAJ. 2007;176(3):327–332. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.060825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saint-Jacques, N., Younis, T., Dewar, R., & Rayson, D. (2007 12/1906/30/received11/10/revised11/13/accepted). Wait times for breast cancer care. British Journal of Cancer, 96(1), 162–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- SAS Institute Inc . Statistical Analysis Software, 9.4 ed. Cary: SAS Institute; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, C. R., Chiarelli, A. M., Holloway, C. M., Mirea, L., O'Malley, F. P., Blackmore, K. M., et al. (2018). The impact of organized breast assessment on survival by stage for screened women diagnosed with invasive breast cancer. The Breast, 41, 25–33. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Statistics Canada. Postal code conversion file plus (PCCF+), reference guide, 2014.

- Vujovic O, Yu E, Cherian A, Perera F, Dar AR, Stitt L, et al. Effect of interval to definitive breast surgery on clinical presentation and survival in early-stage invasive breast cancer. International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics. 2009;75(3):771–774. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.11.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whelan TJ, Julian J, Wright J, Jadad AR, Levine ML. Does locoregional radiation therapy improve survival in breast cancer? A meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2000;18(6):1220–1229. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.6.1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whelan T, Olivotto I, Levine M. Health Canada’s Steering Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines for the C, Treatment of Breast C. Clinical practice guidelines for the care and treatment of breast cancer: breast radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery (summary of the 2003 update) CMAJ. 2003;168(4):437–439. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff AC, Hammond ME, Schwartz JN, Hagerty KL, Allred DC, Cote RJ, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists guideline recommendations for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer. Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine. 2007;131(1):18–43. doi: 10.5858/2007-131-18-ASOCCO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]