Abstract

Objective

In the province of Manitoba, Canada, given that latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) treatment is provided at no cost to the patient, treatment completion rates should be optimal. The objective of this study was to estimate LTBI treatment completion using prescription drug administrative data and identify patient characteristics associated with completion.

Methods

Prescription drug data (1999–2014) were used to identify individuals dispensed isoniazid (INH) or rifampin (RIF) monotherapy. Treatment completion was defined as being dispensed INH for ≥ 180 days (INH180) or ≥ 270 days (INH270) or RIF for ≥ 120 days (RIF120). Logistic regression models tested socio-demographic and comorbidity characteristics associated with treatment completion.

Results

The study cohort comprised 4985 (90.4%) persons dispensed INH and 529 (9.6%) RIF. Overall treatment completion was 60.2% and improved from 43.1% in 1999–2003 to 67.3% in 2009–2014. INH180 showed the highest completion (63.8%) versus INH270 (40.4%) and RIF120 (27.0%). INH180 completion was higher among those aged 0–18 years (68.5%) compared with those aged 19+ (61.0%). Sex, geography, First Nations status, income quintile, and comorbidities were not associated with completion.

Conclusions

Benchmark 80% treatment completion rates were not achieved in Manitoba. Factors associated with non-completion were older age, INH270, and RIF120. Access to shorter LTBI treatments, such as rifapentine/INH, may improve treatment completion.

Keywords: Humans, Canada, English, Cohort studies, Public health practice

Résumé

Objectifs

Au Manitoba, Canada, étant donné que le traitement de l’infection tuberculeuse latente (ITL) est gratuit, le taux d’achèvement du traitement devrait être optimal. L’objectif de cette étude était d’estimer l’achèvement du traitement de l’ITL à l’aide de données administratives sur les médicaments d’ordonnance et d’identifier les caractéristiques des patients associées à l’achèvement du traitement.

Méthodes

Les données sur les médicaments d’ordonnance (1999 à 2014) ont été utilisées pour identifier les personnes dispensées en monothérapie l’isoniazide (INH) ou la rifampicine (RIF). L’achèvement du traitement a été définie comme étant une délivrance d’INH supérieure ou égale à 180 jours (INH180) ou supérieure ou égale à 270 jours (INH270) ou une délivrance de la RIF supérieure ou égale à 120 jours (RIF120). Les modèles de régression logistique ont évalué les caractéristiques sociodémographiques et de comorbidité associées à l’achèvement du traitement.

Résultats

La cohorte à l’étude comprenait 4985 (90,4 %) individus dispensées d’INH et 529 (9,6 %) de la RIF. L’achèvement du traitement globale était de 60,2 % et est passé de 43,1 % en 1999–2003 jusqu’à 67,3 % en 2009–2014. L’INH180 a montré l’achèvement le plus élevé (63,8 %) par rapport à l’INH270 (40,4 %) et à la RIF120 (27,0 %). L’achèvement de l’INH180 était plus élevé chez les 0 à 18 ans (68,5 %) que chez les 19 ans et plus (61,0 %). Le sexe, la région de résidence, l’identification des Premières nations, le quintile de revenu et les comorbidités n’étaient pas associés à l’achèvement du traitement.

Conclusions

Le taux de référence du traitement de 80 % n’a pas été atteint au Manitoba. Les facteurs associés au non-achèvement étaient l’âge et l’utilisation d’INH270 ou de la RIF120. L’accès à des traitements plus courts de l’ITL, tels que la rifapentine/INH, pourrait améliorer l’achèvement du traitement.

Mots-clés: Humains, Canada, Anglais, Études de cohorte, Pratique de la santé publique

Introduction

In low-incidence countries, the elimination of tuberculosis (TB) will only be achieved when effective treatment of latent TB infection (LTBI) leads to significant reductions of large reservoirs of future TB cases (Stagg et al. 2014).

The province of Manitoba, Canada, has active TB disease rates above the national average, particularly in Indigenous and foreign-born populations (Gallant et al. 2017). LTBI medications are provided at no cost to the patient under the province’s universal healthcare program (Manitoba Health, Seniors and Active Living. Manitoba Tuberculosis Protocol 2014). Therefore, treatment completion rates, an important performance indicator, should be optimal.

Canadian prospective clinical cohort studies (Hirsch-Moverman et al. 2015; Malejczyk et al. 2014; Pettit et al. 2013) and retrospective observational studies based on population-based prescription drug administrative data (Rivest et al. 2013; Rubinowicz et al. 2014; Smith et al. 2011) have consistently reported low-to-moderate LTBI treatment completion rates (31–74%). Since LTBI is not a reportable communicable disease in Manitoba, information on LTBI treatment completion is not routinely collected.

The objective of this study was to estimate the percentage of individuals completing LTBI treatment and identify characteristics associated with treatment completion in Manitoba, Canada.

Study population and methods

Manitoba has a population of about 1.3 million. This population-based retrospective cohort study focused on extracted data from prescription drug dispensing records for provincial residents between April 1, 1999 and March 31, 2014.

Data sources

Data were from the Population Research Data Repository housed at the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy (MCHP). The Repository contains virtually all healthcare contacts for provincial residents eligible for healthcare coverage; these data can be linked using an anonymized personal health number to create longitudinal healthcare histories. Prescription records were extracted from the provincial Drug Program Information Network (DPIN) database. This community pharmacy system generates complete drug profiles for each client. Information on region of residence, First Nations status, and income quintile were from the provincial health insurance registry, First Nations registry of the federal government, and the national census, respectively. Charlson Comorbidity Index scores were calculated using diagnoses recorded in hospital discharge abstracts and physician billing claims in the year prior to the date of treatment initiation (Charlson et al. 1987).

Study cohort

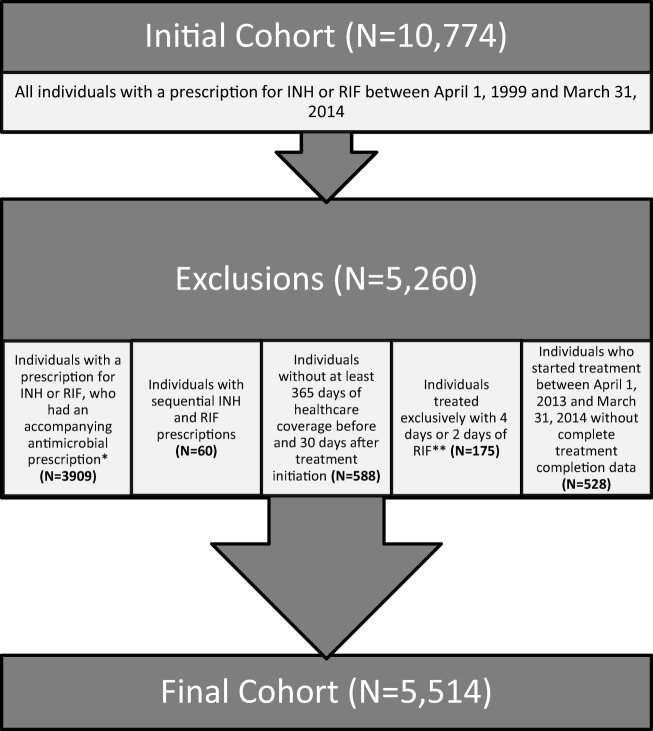

Isoniazid (INH) and rifampin (RIF) are most commonly used as monotherapy for LTBI treatment in Manitoba. The first INH or RIF drug dispensing date in the study period was the treatment initiation date. Individuals dispensed any concomitant antimicrobials were excluded (Fig. 1), as were individuals with sequential prescribing of INH and RIF. Individuals treated exclusively with 4 days or 2 days of RIF, the usual post-exposure prophylaxis for invasive Haemophilus influenza or meningococcal disease, respectively, were excluded. Persons who did not have at least 365 days of healthcare coverage before and 30 days of coverage after the INH or RIF treatment initiation date were excluded. Finally, individuals who started treatment between April 1, 2013 and March 31, 2014 were excluded, as there was insufficient follow-up time to ascertain treatment completion rates (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Study flow chart for treated LTBI cohort in Manitoba, 1999–2014. * Individuals dispensed INH who were prescribed, within 14 days, concomitant medications used to treat mycobacterial infections (i.e., RIF, rifabutin, ethambutol, pyrazinamide, amikacin, capreomycin, cycloserine, linezolid, moxifloxacin, para-aminosalicylic acid or streptomycin) (N = 561), and individuals dispensed RIF who were prescribed, within 14 days, concomitant medications used to treat mycobacterial infections (i.e., INH, amikacin, clofazimine, capreomycin, cycloserine, dapsone, ethambutol, para-aminosalicylic acid, pyrazinamide, or streptomycin), or methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (i.e., azithromycin, cefazolin, cefotaxime, cefoxitin, ceftriaxone, cefuroxime, ciprofloxacin, clarithromycin, clindamycin, cloxacillin, daptomycin, doxycycline, erythromycin, flucloxacillin, fusidic acid, gentamicin, imipenem, levofloxacin, linezolid, meropenem, minocycline, moxifloxacin, mupirocin, sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, or vancomycin) (N = 3348). ** 4 days or 2 days of RIF was deemed to be post-exposure chemoprophylaxis prescribed for the prevention of invasive Haemophilus influenza (N = 64) or meningococcal disease (N = 111), respectively

Nine months of daily self-administered INH or 4 months of daily self-administered RIF are currently recommended in Canada for the treatment of LTBI (Public Health Agency of Canada and the Canadian Thoracic Society and the Canadian Lung Association 2014). Persons dispensed INH for 270 days or more within a 365-day period were defined as having completed INH treatment (INH270), as were persons dispensed RIF for 120 days or more within a 180-day period (RIF120). Since completion of 6 months of INH is also considered a full course of treatment, albeit less efficacious than a 9-month treatment course (Public Health Agency of Canada and the Canadian Thoracic Society and the Canadian Lung Association 2014), individuals dispensed INH for 180 days or more within a 270-day period were defined as having completed a shorter course of INH treatment (INH180).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the cohort. Treatment completion was calculated as the percentage of individuals who completed treatment based on the defined criteria (i.e., INH270, INH180, and RIF120). Cohort characteristics of age group (0–18 years, 19–44 years, 45+ years), sex, population group (First Nations and all other Manitobans), place of residence (health region of residence, grouped into rural northern, rural southern, and urban/Winnipeg), income quintile (Q1 [lowest income] to Q5 [highest income]), Charlson Comorbidity Index scores (the weighted sum of 17 chronic or infectious disease diagnoses) (Charlson et al. 1987), and year of treatment initiation (5-year periods of 1999–2003, 2004–2008, 2009–2014) were assessed for their associations with treatment completion via multivariable logistic regression analysis. Model fit was evaluated using the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test. The C-statistic, which is the area under the receiver operating characteristics curve, was used to determine model discriminatory power. Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated. Analyses were conducted using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Ethics approval was provided by the University of Manitoba Health Research Ethics Board and the Manitoba First Nations Health Information Governance Committee, which oversees health research involving First Nations. Approval for data access was provided by the Manitoba Health Information Privacy Committee.

Results

Treated LTBI cohort

A total of 10,774 individuals received a prescription for INH or RIF in the 15-year study period; approximately one third were excluded from the cohort because of concurrent antimicrobial prescriptions (Fig. 1). The final cohort comprised 5514 individuals; 4985 (90.4%) received INH and 529 (9.6%) received RIF. Within this cohort, 89% of individuals maintained healthcare coverage from 365 days prior to the treatment initiation date to 720 days following treatment initiation.

Socio-demographic characteristics are provided in Table 1. Just over half of the cohort was female (51.9%). Slightly over half of cohort members were from the rural north (53.2%), with the remainder mostly from the largest urban centre (Winnipeg, 34.4%), and a smaller proportion from the rural south (12.4%). Over one third were under 19 years of age (34.9%). Among urban (i.e., Winnipeg) residents, one quarter (24.2%) were under 19 years, while 47.0% of rural residents were under 19 years. Two thirds of the cohort (65.8%) were registered First Nations (Indigenous) individuals. Almost half of the cohort was from the lowest income quintile (47.9%), whereas only 5.8% were from the highest quintile. Three quarters (76.0%) had a Charlson Comorbidity Index score of 0.

Table 1.

Treatment completion rates (%) by type of medication and cohort characteristics in Manitoba, 1999–2014

| INH180, N = 4985 | INH270, N = 4985 | RIF120, N = 529 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment, complete | Total | Rate (%) | Treatment, complete | Total | Rate (%) | Treatment, complete | Total | Rate (%) | |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Female | 1613 | 2586 | 62.4 | 1017 | 2586 | 39.3 | 73 | 275 | 26.5 |

| Male | 1566 | 2399 | 65.3 | 998 | 2399 | 41.6 | 70 | 254 | 27.6 |

| Age group (years) | |||||||||

| 0–18 | 1262 | 1842 | 68.5 | 854 | 1842 | 46.4 | 10 | 84 | 11.9 |

| 19–44 | 1273 | 2086 | 61.0 | 746 | 2086 | 35.8 | 67 | 180 | 37.2 |

| 45–64 | 574 | 936 | 61.3 | 364 | 936 | 38.9 | 55 | 169 | 32.5 |

| 65+ | 70 | 121 | 57.9 | 51 | 121 | 42.1 | 11 | 96 | 11.5 |

| Region of residence | |||||||||

| Rural north | 1840 | 2848 | 64.6 | 1155 | 2848 | 40.6 | 35 | 85 | 41.2 |

| Rural south | 311 | 499 | 62.3 | 206 | 499 | 41.3 | 45 | 184 | 24.5 |

| Urban | 1028 | 1638 | 62.8 | 654 | 1638 | 39.9 | 63 | 260 | 24.2 |

| Registered First Nations status | |||||||||

| First Nations | 2236 | 3506 | 63.8 | 1424 | 3506 | 40.6 | 47 | 121 | 38.8 |

| All other Manitobans | 943 | 1479 | 63.8 | 591 | 1479 | 40.0 | 96 | 408 | 23.5 |

| Income quintile | |||||||||

| Q1 (lowest) | 1554 | 2489 | 62.4 | 976 | 2489 | 39.2 | 42 | 153 | 27.5 |

| Q2 | 579 | 866 | 66.9 | 375 | 866 | 43.3 | 26 | 101 | 25.7 |

| Q3 | 218 | 348 | 62.6 | 134 | 348 | 38.5 | 30 | 95 | 31.6 |

| Q4 | 683 | 1042 | 65.5 | 448 | 1042 | 43.0 | 30 | 98 | 30.6 |

| Q5 (highest) | 145 | 240 | 60.4 | 82 | 240 | 34.2 | 15 | 82 | 18.3 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | |||||||||

| 0 (most healthy) | 2535 | 3887 | 65.2 | 1599 | 3887 | 41.1 | 90 | 303 | 29.7 |

| 1–2 | 520 | 899 | 57.8 | 328 | 899 | 36.5 | 41 | 153 | 26.8 |

| 3+ (less healthy) | 124 | 199 | 62.3 | 88 | 199 | 44.2 | 12 | 73 | 16.4 |

| Treatment initiation period | |||||||||

| 1999–2003 | 418 | 820 | 51.0 | 65 | 820 | 7.9 | 9 | 171 | 5.3 |

| 2004–2008 | 1439 | 2236 | 64.4 | 914 | 2236 | 40.9 | 15 | 147 | 10.2 |

| 2009–2014 | 1322 | 1929 | 68.5 | 1036 | 1929 | 53.7 | 119 | 211 | 56.4 |

| Overall total | |||||||||

| 3179 | 4985 | 63.8 | 2015 | 4985 | 40.4 | 143 | 529 | 27.0 | |

INH180, 180-day supply of isoniazid dispensed within 270 days of treatment initiation; INH270, 270-day supply of isoniazid dispensed within 365 days of treatment initiation; RIF120, 120-day supply of rifampin dispensed within 180 days of treatment initiation

The cohort was not equally distributed across the 15-year study period. Only 18.0% received LTBI treatment in the first 5-year period (1999–2003), whereas 38.8% received treatment in the last 5-year period (2009–2014), revealing a substantial growth in the number of individuals treated for LTBI over time.

LTBI treatment completion

Overall, 60.2% of the study cohort completed LTBI treatment, improving from 43.1% in 1999–2003 to 67.3% in 2009–2014. INH180 showed the highest treatment completion (63.8%), which remained stable from 2005 to 2014 (Fig. 2). INH270 treatment completion was lower (40.4%) but increased significantly over the 15-year period. After 2007, treatment completion stabilized at around 50–60% (Fig. 2). RIF120 treatment completion was the lowest overall (27.0%), but increased substantially after 2011, up to nearly 70% by 2014 (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Treatment completion rates (%) by type of medication in the treated LTBI cohort in Manitoba, 1999–2014. INH180, 180-day supply of isoniazid dispensed within 270 days of treatment initiation; INH270, 270-day supply of isoniazid dispensed within 365 days of treatment initiation; RIF120, 120-day supply of rifampin dispensed within 180 days of treatment initiation

Treatment completion significantly improved over time; it was highest for INH180 (68.5%) in the most recent 5-year period (2009–2014), versus 51.0% in 1999–2003 and 64.4% in 2004–2008 (Table 1). The increase in INH180 treatment completion in 2009–2014 compared with 1999–2003 was statistically significant (OR 2.1; 95% CI 1.7–2.4; p < 0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Logistic regression results for cohort characteristics associated with LTBI treatment completion in Manitoba, 1999–2014

| INH180, N = 4985 | INH270, N = 4985 | RIF120, N = 529 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adj OR | 95% CI | Adj OR | 95% CI | Adj OR | 95% CI | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Male | 1.1 | 1.0–1.2 | 1.1 | 0.9–1.2 | 1.0 | 0.6–1.6 |

| Age group (years) | ||||||

| 0–18 | 1.4 | 1.2–1.6 | 1.6 | 1.4–1.8 | 0.5 | 0.2–1.3 |

| 19–44 | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| 45–64 | 1.0 | 0.9–1.2 | 1.0 | 0.9–1.3 | 0.9 | 0.5–1.5 |

| 65+ | 0.9 | 0.6–1.3 | 1.1 | 0.7–1.7 | 0.4 | 0.2–0.9 |

| Region of residence | ||||||

| Rural north | 1.1 | 0.9–1.4 | 1.0 | 0.8–1.2 | 1.8 | 0.8–4.3 |

| Rural south | 1.0 | 0.8–1.3 | 1.1 | 0.8–1.3 | 0.9 | 0.5–1.5 |

| Urban | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Registered First Nations status | ||||||

| First Nations | 0.8 | 0.7–1.0 | 0.9 | 0.7–1.0 | 1.0 | 0.5–2.2 |

| All other Manitobans | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Income quintile | ||||||

| Q1 (lowest) | 1.0 | 0.8–1.4 | 1.1 | 0.8–1.5 | 1.2 | 0.5–2.7 |

| Q2 | 1.2 | 0.9–1.7 | 1.2 | 0.9–1.7 | 1.6 | 0.7–3.9 |

| Q3 | 1.0 | 0.7–1.5 | 1.0 | 0.7–1.5 | 1.8 | 0.8–4.2 |

| Q4 | 1.1 | 0.8–1.5 | 1.3 | 0.9–1.8 | 1.5 | 0.6–3.5 |

| Q5 (highest) | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Charlson Comorbidity Index score | ||||||

| 0 (most healthy) | 1.0 | 0.7–1.3 | 0.7 | 0.5–1.0 | 2.2 | 1.0–4.9 |

| 1–2 | 0.8 | 0.6–1.1 | 0.6 | 0.5–0.9 | 1.4 | 0.6–3.2 |

| 3+ (less healthy) | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Treatment initiation period | ||||||

| 1999–2003 | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| 2004–2008 | 1.7 | 1.4–2.0 | 7.9 | 6.1–10.5 | 2.0 | 0.8–4.8 |

| 2009–2014 | 2.1 | 1.7–2.4 | 13.5 | 10.3–17.6 | 21.3 | 9.9–45.9 |

INH180, 180-day supply of isoniazid dispensed within 270 days of treatment initiation; INH270, 270-day supply of isoniazid dispensed within 365 days of treatment initiation; RIF120, 120-day supply of rifampin dispensed within 180 days of treatment initiation; Adj OR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval

Cohort characteristics associated with treatment completion

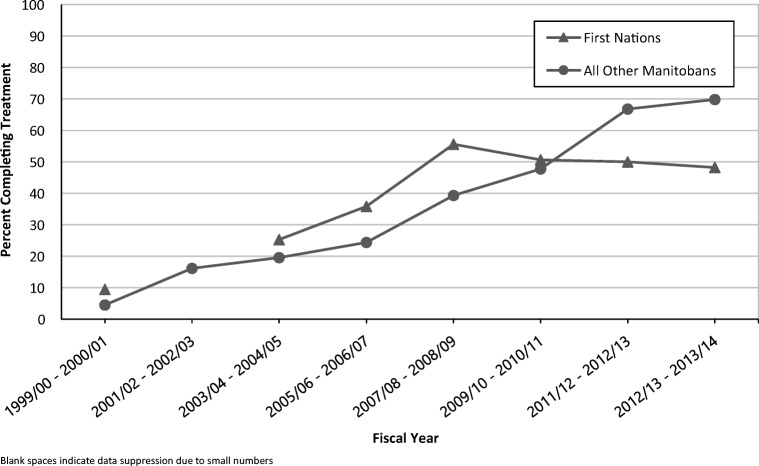

As Table 2 reveals, the odds of INH180 completion was higher in individuals under 19 years versus individuals 19–44 years (68.5% versus 61.0%; OR 1.4 (95% CI 1.2–1.6); p < 0.001). Sex, region of residence, First Nations status, income quintile, and Charlson Comorbidity Index scores were not significantly associated with treatment completion (Table 2). However, an analysis of treatment completion rates by First Nations status revealed a reversal in the difference in treatment completion rates between First Nations persons and all other Manitobans (Fig. 3). Prior to 2009, treatment completion rates were higher in First Nations persons, but after 2009, treatment completion rates in First Nations persons were lower than for all other Manitobans (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Treatment completion rates (%) for treated LTBI cohort for a 270-day supply of isoniazid, stratified by First Nations status. Blank spaces indicate data suppression due to small numbers

The C-statistic showed poor, modest, and good model discriminatory power for INH180 (C = 0.59), INH270 (C = 0.68), and RIF120 (C = 0.85) treatment completion, respectively. The Hosmer-Lemeshow test showed a significant lack of model fit to the data for INH270 (p < 0.05), while not showing evidence of lack of fit for INH180 (p = 0.06) or RIF120 (p = 0.11).

Discussion

A LTBI treatment completion rate of 64% over 15 years for a 6-month course of INH is comparable with that reported in Canadian retrospective observational studies using population-based prescription drug administrative data (Rivest et al. 2013; Rubinowicz et al. 2014; Smith et al. 2011). The stability of INH180 completion rates at 60–70% between 2005 and 2014 suggests a limited likelihood of improvement. It would appear that a plateau has also been reached for INH270 treatment completion, which remained at 50–60% between 2007 and 2014. The large increase in INH270 treatment completion rates between 1999 and 2008 likely reflects the increasing trend toward favouring and encouraging INH270 over INH180 due to higher efficacy with longer courses of INH (Public Health Agency of Canada and the Canadian Thoracic Society and the Canadian Lung Association 2014).

Although we did not have access to indications for LTBI treatment, the Manitoba provincial TB protocol (Manitoba Health, Seniors and Active Living. Manitoba Tuberculosis Protocol 2014) recommends that LTBI testing and treatment be considered in those who have had recent contact with a person who has been diagnosed with infectious respiratory TB, as well as those persons exposed to TB at any time with an increased risk of reactivation due to impaired immunity such as HIV infection and other immunocompromising conditions, diabetes, renal failure, immunosuppressant medication, or pulmonary silicosis. In addition, those with radiographic evidence of old healed inactive TB but no history of prior treatment may be offered LTBI treatment (Manitoba Health, Seniors and Active Living. Manitoba Tuberculosis Protocol 2014). Given that two thirds of our cohort were Indigenous persons and the vast majority of Indigenous persons treated for LTBI in Manitoba are recent contacts of a person diagnosed with respiratory TB, one can safely assume that the primary indication for LTBI treatment in our cohort was recent contact with TB.

Given modest INH treatment completion rates, a desire for shorter equally efficacious treatment courses has led to increasing use of a 4-month course of RIF in Manitoba since 2010. With a shorter duration of treatment, completion rates between 2012 and 2014 were close to 70%. Although the rapid rise in RIF120 treatment completion between 2010 and 2014 is encouraging, it may still be difficult to achieve the desired benchmark of 80% completion using either INH270 or RIF120, the regimens that were recommended and available in Canada during the study period (Public Health Agency of Canada and the Canadian Thoracic Society and the Canadian Lung Association 2014). Access to shorter more easily administered LTBI treatments such as once weekly rifapentine and INH for 12 weeks (Sterling et al. 2011) may improve LTBI treatment completion rates.

INH treatment completion was higher among individuals aged 0–18 years compared with individuals aged 19–44 years. This is not surprising given the longstanding policy in Manitoba to deliver directly observed pediatric LTBI treatment. Parental support likely also assisted in maximizing treatment completion in younger children.

That treatment completion was lowest among those dispensed RIF is at odds with previous studies (Rivest et al. 2013; Aspler et al. 2010). However, the wide use of RIF for the treatment of LTBI in Manitoba is relatively recent, with limited experience among prescribers. Until recently, RIF was predominantly used as second-line therapy for persons with INH intolerances or contraindications as recommended by the Canadian Tuberculosis Standards (CTS) (Public Health Agency of Canada and the Canadian Thoracic Society and the Canadian Lung Association 2014). The fact that 43% of persons treated with RIF had comorbidities (Charlson score of ≥ 1) versus 22% of persons treated with INH suggests that persons receiving RIF had greater clinical complexities, which may have contributed to lower treatment completion. That overall RIF treatment completion has significantly increased in recent years (2011–2014) is likely a reflection of RIF being more recently considered a first-line LTBI treatment option. RIF treatment completion rates will require monitoring over time to see if they will exceed INH treatment completion rates.

Region of residence, First Nations status, income quintile, and Charlson Comorbidity score did not demonstrate an association with LTBI treatment completion rates. Of concern, however, is that results for the most recent years suggest a plateauing of INH270 treatment completion rates at 50% within First Nations populations while all other Manitobans have seen increasing treatment completion rates to 70%. Determinants of health, including poverty, decreased access to healthcare, inadequate housing, historical injustices, and structural racism, could adversely affect treatment completion rates in First Nations populations.

The highest treatment completion rates were achieved in 2012–2014, with values of 71% for INH180, 68% for RIF120, and 58% for INH270. These rates are comparable with those reported elsewhere (Rivest et al. 2013; Rubinowicz et al. 2014; Smith et al. 2011; Aspler et al. 2010; Horsburgh Jr et al. 2010; Spicer et al. 2013), suggesting a low likelihood of achieving significantly better treatment completion rates with daily regimens taken over several months. Given that our study, like those of Rivest et al. (2013) and Rubinowicz et al. (2014), used cohorts from easily accessible administrative databases, it should be feasible to continue measuring and comparing LTBI treatment completion rates for Manitoba and other jurisdictions with low TB incidence rates.

This study had important limitations. First, prescription drug records do not allow determination of whether the dispensed medications were ingested. Further study will be required to develop a tool to understand the extent to which dispensed medications are in fact ingested medications. A tool for verifying that dispensed medications are ingested could be developed for validation of administrative pharmacy dispensing data for future LTBI treatment completion research.

We were not able to capture immigration or refugee status within our databases. Therefore, it was not possible to analyze LTBI treatment completion separately among persons born outside of Canada.

We did not perform sex-gender-based analyses on subpopulations such as First Nations children and adults. Hence, we were not able to comment on treatment completion rates by age and gender within First Nations populations to determine if more recent plateauing of INH270 treatment completion rates were correlated to age or gender. More investigation will be needed to fully explore treatment completion co-factors in subpopulations.

In addition, given that LTBI is not a reportable communicable disease in Manitoba, it is not possible to ascertain the number of persons diagnosed with LTBI. Thus, LTBI treatment initiation rates cannot be calculated. Successful management and containment of LTBI requires both high treatment initiation and completion rates (Alsdurf et al. 2016). A benchmark of 80% treatment initiation in addition to 80% treatment completion is recommended (Public Health Agency of Canada and the Canadian Thoracic Society and the Canadian Lung Association 2014). However, even well-funded and well-conducted community outreach LTBI screening initiatives in northern Canadian Indigenous communities have only achieved treatment initiation in 47–61% of those eligible for LTBI treatment (Alvarez et al. 2014). With such low treatment initiation rates in remote northern communities, treatment completion rates are rendered irrelevant in the LTBI treatment cascade (Alsdurf et al. 2016).

Our logistic regression models showed that for RIF120, the included covariates were able to predict LTBI treatment completion well, while models for INH180 and INH270 showed lower discriminatory power, suggesting unmeasured variables that may enable better prediction of LTBI treatment completion for INH180 and INH270. Moreover, the INH270 model showed a significant lack of model fit to the data, which means the predicted values and observed values for treatment completion were significantly different. There is therefore a need for further research to identify other factors potentially associated with LTBI treatment completion for INH270 and INH180.

LTBI treatment completion rates could have been affected by individuals whose healthcare coverage was not sustained after initiation of LTBI treatment up to the treatment completion dates of 365 days for INH270, 270 days for INH180, or 180 days for RIF120. However, 89% of the treated LTBI cohort maintained healthcare coverage for 720 days following treatment initiation, suggesting that treatment completion rates would not have been appreciably impacted by any loss of coverage.

This cohort only represented persons with treated LTBI. Our case definition for LTBI monotherapy excluded persons who were treated with sequential INH followed by RIF treatment or vice versa and may have excluded persons who could have been treated for LTBI with combined INH and RIF (an uncommon practice in Manitoba). We may have also excluded persons prescribed RIF for LTBI who were also prescribed an antibiotic on our exclusion list within 14 days for a concomitant unrelated infection. However, none of these limitations would have significantly affected our measurement of treatment completion rates. We used case definitions based on previous studies using similar administrative databases (Rivest et al. 2013; Rubinowicz et al. 2014; Smith et al. 2011) to achieve comparability between studies.

We did not measure prescriber or clinic attributes and therefore cannot determine whether LTBI treatment was prescribed by primary care clinicians or specialists. We assume that the majority of children treated for LTBI were managed by pediatric chest medicine specialists, as has been the routine in Manitoba for many years. In Rubinowicz et al.’s (2014) study, 26% of LTBI treatment was delivered by primary care practitioners. Historically, in Manitoba, most LTBI treatment was prescribed by chest medicine specialists, but since 2011, a growing number of primary care clinicians have been managing LTBI. Measuring LTBI treatment completion rates by medical specialist and primary care practitioners provides an opportunity for further research.

We also did not have access to clinical data such as symptoms or elevated liver enzymes indicative of adverse events that could have provided valuable information concerning reasons explaining treatment discontinuation.

Finally, a deeper analysis of reasons for treatment non-completion will require qualitative research among both First Nations communities and persons immigrating from high TB incidence countries, who are most likely to be prescribed LTBI treatment in Canada, to help us better understand issues that either facilitate adherence or create barriers to treatment completion.

Conclusion

LTBI treatment completion rates in Manitoba, although comparable with rates in other jurisdictions, are too low to achieve optimal reductions in large LTBI reservoirs. INH or RIF treatment completion rates appear to have plateaued at 70%, short of the 80% benchmark. It remains to be seen whether shorter courses of LTBI treatment, such as weekly high-dose rifapentine and INH, only recently accessible in Canada (Health Canada, Drugs and Health Products, Access to Drugs in Exceptional Circumstances 2018), will result in higher completion rates (Alvarez et al. 2014). Further investigation is needed into the impact of various interventions over the entire LTBI cascade of care, including LTBI screening and diagnosis, when and how to offer LTBI treatment, and how to improve LTBI treatment acceptance/initiation rates, in addition to improving treatment completion rates (Alsdurf et al. 2016).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy (MCHP) for the use of the data in the Manitoba Population Research Data Repository under HIPC project #2015/2016-64.

Financial support

This study was financially funded by the operational funds from the Province of Manitoba and the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy.

Compliance with ethical standards

Ethics approval was provided by the University of Manitoba Health Research Ethics Board and the Manitoba First Nations Health Information Governance Committee, which oversees health research involving First Nations. Approval for data access was provided by the Manitoba Health Information Privacy Committee.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Disclaimer

The results and conclusions are those of the authors and no official endorsement by the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy or Manitoba Health, Seniors and Active Living is intended or should be inferred.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Alsdurf H, Hill PC, Matteelli A, et al. The cascade of care in diagnosis and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2016;16(11):1269–1278. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30216-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez GG, VanDyk DD, Aaron SD, et al. TAIMA (stop) TB: the impact of a multifaceted TB awareness and door-to-door campaign in residential areas of high risk for TB in Iqualuit, Nunavut. PLoS One. 2014;9(7):e100975. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aspler A, Long R, Trajman A, et al. Impact of treatment completion, intolerance and adverse events on health system costs in a randomised trial of 4 months rifampin or 9 months isoniazid for latent TB. Thorax. 2010;65:582–587. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.125054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. Journal of Chronic Diseases. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallant V, Duvvuri V, McGuire M. Tuberculosis in Canada – summary 2015. Canada Communicable Disease Report. 2017;43(3):77–82. doi: 10.14745/ccdr.v43i34a04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Canada, Drugs and Health Products, Access to Drugs in Exceptional Circumstances. List of drugs for an urgent public health need. February 2018. (accessed May 2019 at https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/access-drugs-exceptional-circumstances/list-drugs-urgent-public-health-need.html).

- Hirsch-Moverman Y, Shrestha-Kuwahara R, Bethel J, et al. Latent tuberculous infection in the United States and Canada: who completes treatment and why? The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2015;19(1):31–38. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.14.0373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horsburgh CR, Jr, Goldberg S, Bethel J, et al. Latent TB infection treatment acceptance and completion in the United States and Canada. Chest. 2010;137(2):401–409. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-0394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malejczyk K, Gratrix J, Beckon A, et al. Factors associated with noncompletion of latent tuberculosis infection treatment in an inner-city population in Edmonton, Alberta. The Canadian Journal of Infectious Diseases & Medical Microbiology AMMI Canada. 2014;25(5):281–284. doi: 10.1155/2014/349138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manitoba Health, Seniors and Active Living. Manitoba Tuberculosis Protocol. February 2014. (accessed May 2019 at http://www.gov.mb.ca/health/publichealth/cdc/protocol/tb.pdf).

- Pettit AC, Bethel J, Hirsch-Moverman Y, Colson PW, Sterling TR. Female sex and discontinuation of isoniazid due to adverse effects during the treatment of latent tuberculosis. Journal of Information Security. 2013;67(5):424–432. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2013.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Agency of Canada and the Canadian Thoracic Society and the Canadian Lung Association. Canadian Tuberculosis Standards. 7th edition. February 2014. (accessed May 2019 at http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/tbpc-latb/pubs/tb-canada-7/index-eng.php).

- Rivest P, Street MC, Allard R. Completion rates of treatment for latent tuberculosis infection in Quebec, Canada from 2006 to 2010. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2013;104(3):e235–e239. doi: 10.17269/cjph.104.3643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinowicz A, Bartlett G, MacGibbon B, et al. Evaluating the role of primary care physicians in the treatment of latent tuberculosis: a population study. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2014;18(12):1449–1454. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.14.0166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith BM, Schwartzman K, Bartlett G, Menzies D. Adverse events associated with treatment of latent tuberculosis in the general population. CMAJ. 2011;183(3):E173–E179. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.091824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spicer KB, Perkins L, DeJesus B, et al. Completion of latent tuberculosis therapy in children: impact of country of origin and neighborhood clinics. Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society. 2013;2(4):312–319. doi: 10.1093/jpids/pit015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stagg HR, Zenner D, Harris RJ, et al. Treatment of latent tuberculosis infection: a network meta-analysis. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2014;161:419–428. doi: 10.7326/M14-1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterling TR, Villarino ME, Borisov AS, et al. TB Trials Consortium PREVENT TB Study Team. Three months of rifapentine and isoniazid for latent tuberculosis infection. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;365:2155–2166. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1104875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]