Abstract

Objective

Young adults living in single room occupancy (SRO) hotels, a form of low-income housing, are known to have complex health and substance problems compared to their peers in the general population. The objective of this study is to comprehensively describe the mental, physical, and social health profile of young adults living in SROs.

Methods

This study reports baseline data from young adults aged 18–29 years, as part of a prospective cohort study of adults living in SROs in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. Baseline and follow-up data were collected from 101 young adults (median follow-up period 1.9 years [IQR 1.0–3.1]). The comprehensive assessment included laboratory tests, neuroimaging, and clinician- and patient-reported measures of mental, physical, and social health and functioning.

Results

Three youth died during the preliminary follow-up period, translating into a higher than average mortality rate (18.6, 95% CI 6.0, 57.2) compared to age- and sex-matched Canadians. High prevalence of interactions with the health, social, and justice systems was reported. Participants were living with median two co-occurring illnesses, including mental, neurological, and infectious diseases. Greater number of multimorbid illnesses was associated with poorer real-world functioning (ρ = − 0.373, p < 0.001). All participants reported lifetime alcohol and cannabis use, with pervasive use of stimulants and opioids.

Conclusion

This study reports high mortality rates, multimorbid illnesses, poor functioning, poverty, and ongoing unmet mental health needs among young adults living in SROs. Frequent interactions with the health, social, and justice systems suggest important points of intervention to improve health and functional trajectories of this vulnerable population.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.17269/s41997-018-0087-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Young adult, Mental health, Social marginalization, Housing

Résumé

Objectif

Les jeunes adultes qui vivent dans des maisons de chambres (une forme d’habitation à loyer modique) sont connus pour avoir des problèmes de santé et de consommation complexes comparativement à leurs pairs dans la population générale. Nous avons cherché à décrire de façon exhaustive leur profil de santé mentale, physique et sociale.

Méthode

Nos données de référence sur les jeunes adultes de 18 à 29 ans proviennent d’une étude prospective de cohortes d’adultes vivant dans des maisons de chambres à Vancouver (Colombie-Britannique), au Canada. Les données de référence et de suivi ont été recueillies auprès de 101 jeunes adultes (période de suivi médiane de 1,9 an [écart interquartile 1,0–3,1]). L’évaluation exhaustive a reposé sur des tests de laboratoire, sur la neuroimagerie et sur des indicateurs de santé et de fonctionnement sur le plan mental, physique et social fournis par les cliniciens et les patients.

Résultats

Trois jeunes sont décédés durant la période de suivi préliminaire, ce qui représente un taux de mortalité supérieur à la moyenne (18,6, IC de 95 % : 6,0, 57,2) comparativement aux Canadiens de mêmes groupes d’âge et de sexe. Une forte prévalence d’interactions avec les systèmes sociosanitaire et judiciaire a été déclarée. Les participants vivaient avec un nombre médian de deux maladies concomitantes, notamment des maladies mentales, neurologiques et infectieuses. Le nombre élevé de multimorbidités était associé à des problèmes de fonctionnement dans le monde réel (ρ = −0,373, p < 0,001). Tous les participants ont indiqué avoir consommé de l’alcool et du cannabis au cours de leur vie, et la consommation de stimulants et d’opioïdes était omniprésente chez eux.

Conclusion

L’étude fait état de taux de mortalité élevés, de multimorbidités, de problèmes de fonctionnement, de pauvreté et de besoins de santé mentale non comblés chez les jeunes adultes vivant dans des maisons de chambres. Leurs interactions fréquentes avec les systèmes sociosanitaire et judiciaire pourraient être d’importants points d’intervention pour améliorer la santé et les trajectoires fonctionnelles de cette population vulnérable.

Mots-clés: Jeune adulte, Santé mentale, Marginalisation sociale, Logement

Introduction

An estimated 150 million young adults1 worldwide are homeless or marginally housed (United Nations Educational SaCOU 2015). “Marginal housing” is defined as housing that is below Canadian standards for adequacy, affordability, or suitability2(Chamberlain and Mackenzie 1992). With nearly 40,000 Canadian young adults spending time homeless annually, young adults are one of the fastest growing homeless populations in Canada, with half reporting to be from middle- or upper-income families (Gaetz et al. 2013). Yet, the mortality rate for this population is an astonishing 11–40 times that of housed youth (Roy et al. 2004), with primary causes of death being suicide and drug overdose (Roy et al. 2004). In addition, Canadian data suggests that 70% of homeless youth report experiencing trauma including physical, sexual, or emotional abuse prior to homelessness (Mar et al. 2014; Kidd et al. 2013, 2017). This group is also more likely to report early difficulties in school, family discord, mental and physical illness, and interactions with the criminal justice system (Kidd et al. 2017; Kozloff et al. 2016a). Groups experiencing increased risk include youth who identify as Indigenous and/or as members of sexual minority groups (Cochran et al. 2002).

Increasing evidence emphasizes income and housing as critical determinants of health (Poremski and Hwang 2016; Kumar et al. 2015; Jones et al. 2015; Manwell et al. 2015; McKenzie 2013; Shah et al. 2011). Much work in Canada focuses on community-based initiatives that can address housing instability, homeless prevention, income assistance, and supported employment for marginalized populations (Poremski and Hwang 2016; Poremski et al. 2015a, b; Kidd et al. 2013; Sadowski et al. 2009; Piat et al. 2009). The success of these programs has been well documented (Stergiopoulos et al. 2014; Corbiere et al. 2010). However, at the same time, increasing numbers of people who are homeless or marginally housed are presenting to emergency departments (Latimer et al. 2017). As well, in Vancouver, British Columbia, the number of people who are at risk of homelessness continues to escalate: the highest numbers to date were reported in 2017, with a 30% increase compared to 2014 (BC Non-Profit Housing Association and M. Thomson Consulting 2017).

Optimizing the social determinants of health for adults with mental health problems can significantly reduce costs to the health care system. The At-Home/Chez-Soi study demonstrated that for every two dollars spent on housing, three dollars are saved in health care services for people with mental illness (Stergiopoulos et al. 2014; Aubry et al. 2015; Kirst et al. 2014, 2015). Recent research suggests that the average annual costs (excluding medications) per homeless person in Vancouver is $53,144 (95% confidence interval [CI] $46,297–$60,095) (Latimer et al. 2017). Early interventions are needed to identify individuals who are at high risk of homelessness, and we hypothesize that young adults who are marginally housed meet this criteria (Kozloff et al. 2016b).

Addressing homelessness for youth and young adults is a priority for many Canadian communities (Kidd et al. 2017; Kozloff et al. 2016a, b). A common alternative to homelessness for many Canadian youth is single room occupancy hotels (SROs), a low-income housing option typically comprised of a room 8–12 m2 in size. Most SROs include a sink, hot plate, and shared washroom facilities. Many of these buildings have been critiqued for being substandard, unsanitary, unsafe, and lacking supports for tenants (Lazarus et al. 2011). Most Canadian SROs are located in urban centres, such as the impoverished Downtown Eastside (DTES) in Vancouver. Although located only a few blocks from the city’s core business district, it is distinguished by high levels of poverty, drug activity, and poor health outcomes (Somers et al. 2016). Although all SRO tenants are covered by the Residential Tenancy Act (Province of British Columbia 2017), most SROs in the DTES are notorious for overall poor living conditions. Despite mitigation efforts to steer youth and young adults away from the DTES, it is estimated that nearly 20% of Downtown Eastside residents are aged 30 years or younger (Latimer et al. 2017; BC Non-Profit Housing Association and M. Thomson Consulting 2017).

Two recent studies summarized the health characteristics of a cohort of marginally housed adults living in SROs in a large urban centre (Vila-Rodriguez et al. 2013; Honer et al. 2017). The main findings were that the cohort had high levels of multimorbidity and premature mortality compared to the general population. In this paper, we report health-related data for youth aged 18–29 years within this same cohort.3 The secondary aim was to estimate the mortality rate of this cohort compared to that of age- and sex-matched Canadian data. Information about the health of this subgroup of young adults will enable a preliminary understanding of the needs of youth living in SROs and ways to prioritize and address these needs.

Methods

Study enrolment and design

The Hotel Study methodology has been described in detail elsewhere (Vila-Rodriguez et al. 2013; Honer et al. 2017). In brief, the Hotel Study is an ongoing longitudinal prospective cohort study of adults living in marginal housing that aims to understand the interactions of addiction, mental health, and infection—and how these interactions contribute to health and functioning. Between November 1, 2008 and October 31, 2015, individuals living in marginal housing in Vancouver, Canada, were recruited from SROs and the local downtown community court if they had a court date within the next 6 months. Eligible individuals were age 18 years and older, were fluent in English, and provided written informed consent. Almost all participants recruited from the community court lived in an SRO. All other participants were experiencing marginal housing at the time of recruitment.

In the Hotel Study, participants are assessed monthly on selected outcomes and the follow-up period is 10 years. By consenting to the study, participants are enrolled for 5 years, at which point they are invited to continue participation for an additional 5 years (totaling 10 years of follow-up). Participants provided demographic information and completed a series of comprehensive assessments of their mental, physical, and social health and functioning. All clinically significant findings from laboratory or imaging investigations were reported to participants and their physicians. In accordance with Canada’s Tri-Council Policy, this study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Boards of the University of British Columbia and Simon Fraser University. As approved by the responsible Ethics Committees, participants were provided with an honorarium for the time involved completing assessments. In this report, we describe baseline characteristics of youth participants, aged 18–29 years at study recruitment.

Clinical examination outcomes

Baseline data were collected over multiple visits according to logistical constraints and participant preference. A psychiatrist (FV-R, OL) conducted clinical interviews, including mental status examinations and screening neurological examinations. Psychosocial functioning was assessed using the Role Functioning Scale (Goodman et al. 1993) and Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (Morosini et al. 2000). A psychiatrist (WGH, FV-R) determined psychiatric diagnoses and clinical cognitive impairment by reviewing all available clinical information in a Best Estimate Clinical Evaluation and Diagnosis according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders-TR Fourth Edition (DSM-IV TR) criteria. In addition, trained research assistants performed cognitive testing supervised by a neuropsychologist (AET). Medical history was elicited in structured interviews, including history of seizures and serious head trauma (including loss of consciousness, confusion, memory loss, dizziness, headache, blurred vision, and/or need for hospitalization). Coroner’s reports and hospital records were requested for all participants who died during follow-up to ascertain the timing and cause of death. Clinical assessments were performed in the research office located in the Downtown Eastside.

Participants also completed an MRI scan using a Philips 3.0-T Achieva scanner with an eight-channel head coil at the University of British Columbia (Philips Healthcare, Amsterdam). MRI acquisition for this study has been described previously (Kirst et al. 2014; Willi et al. 2016). Sequences included a T1-weighted high-resolution isotropic 3D IR-weighted fast-field echo sequence, time of flight magnetic resonance angiography, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery, and susceptibility-weighted imaging. A neuroradiologist and neuroimaging scientist (ATV, MKH, DJL) reviewed all scans and noted findings of possible clinical relevance. We excluded incomplete scans or those with significant motion artifact, as determined by neuroimaging scientist. We reported MRI evidence of infarction and traumatic brain injury. Additionally, participants provided blood samples to test for positive serology for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), and hepatitis C virus (HCV) analyzed by a local clinical laboratory. Finally, we used qualitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) of HCV viral DNA to detect active HCV infection.

Self-report outcomes

We administered standardized interview tools to understand factors that may affect health, including demographics, income, employment, and housing status. We asked participants to share their history of non-prescription substance use and confirmed the self-report by urine drug screens (n = 73, kappa = 0.68–0.77, p < 0.001 for methamphetamine, cannabis, cocaine, and opiates). We also asked participants to report any health care or social service utilization in the 30 days prior to assessment, including contact with mental health care providers, hospitalization, and whether they had been detained overnight in jail due to mental health or substance use issues.

Statistical analysis

We analyzed data using R (R Core Team, 2017). We conducted descriptive analyses for all socio-demographic and clinical characteristics using all available data, calculating median and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables and proportions (n/N, %) for categorical variables. The standardized mortality ratio (SMR) was calculated using the indirect method of standardization by comparing the observed number of deaths in the cohort to age- and sex-matched Canadian rates reported by Statistics Canada (Statistics Canada 2009). The confidence interval for SMR was estimated by the Boice-Monson method.

Finally, we calculated multimorbidity scores for participants to estimate the number of confirmed illnesses of a possible 12 (based on frequency and relevance in this population (Vila-Rodriguez et al. 2013)) using available data: stimulant dependence, alcohol dependence, opioid dependence, psychosis, movement disorder, clinically defined cognitive disorder, brain infarction, traumatic brain injury, seizure disorder, or active HCV, HIV, or HBV infection (BC Non-Profit Housing Association and M. Thomson Consulting 2017). The associations between the number of multimorbid illnesses and psychosocial functioning and demographic variables were assessed using Spearman correlation for ordinal variables and Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test for categorical variables. Sensitivity analyses to assess bias from missing data were performed. Due to cell size limitations, gender analyses are limited to participants who identified as male or female only. For all statistical tests, p values of 0.05 or lower were considered statistically significant.

Results

Participants

Of the 515 potentially eligible individuals, 140 declined participation or were unavailable. Of the remaining 375 individuals, 101 met the inclusion criterion of being 29 years of age or younger and were included in the current study. The demographic characteristics are described in Table 1. The median number of years of follow-up for this subcohort was 1.9 years (IQR 1.0, 3.1). Ten participants were recruited from the downtown community court and 91 were recruited from SROs. All participants were living in marginal housing: 96 (95%) in SROs, 4 (4%) in shelter or on the street, and 1 (< 1%) in supportive transitional housing.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Characteristic | Number | Value^ |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Age (years) | 101 | 25.1 (22.7–27.6) |

| Gender | 101 | |

| Male | 74 (73.3%) | |

| Female | 26 (25.7%) | |

| Other | 1 (1.0%) | |

| Ethnicity | 100 | |

| European descent | 66 (66.0%) | |

| Indigenous ancestry | 40 (40.0%) | |

| Other | 13 (13.0%) | |

| Completed high school | 101 | 26 (25.7%) |

| Completed General Education Development Test | 101 | 7 (6.9%) |

| Highest grade completed | 101 | 11.0 (9.0–12.0) |

| Any post-secondary training | 98 | 36 (36.7%) |

| Completed post-secondary diploma or certificate | 99 | 20 (20.2%) |

| Single, never married | 100 | 92 (92.0%) |

| Formal income and employment | ||

| Monthly income (Canadian dollars) | 95 | 720 (610–908) |

| Receiving income assistance* | 99 | 65 (65.7%) |

| Receiving long-term disability assistance* | 99 | 40 (40.4%) |

| Currently employed | 99 | 8 (8.1%) |

| Skill level of highest paying work | 98 | |

| Never employed | 9 (9.2%) | |

| Unskilled | 75 (76.5%) | |

| Semi-skilled | 11 (11.2%) | |

| Skilled/professional/managerial | 3 (3.1%) | |

| Housing history | ||

| Lived in foster care ever in the past | 100 | 25 (25.0%) |

| Lived with adopted family ever in the past | 100 | 11 (11.0%) |

| Lived in group home ever in the past | 100 | 12 (12.0%) |

| Experienced period of homelessness ever in the past | 100 | 88 (88.0%) |

| Jailed ever in the past | 100 | 20 (20.0%) |

| Hospitalized ever in the past | 99 | 65 (65.7%) |

| Age of first period of homelessness (years) | 88 | 19.2 (17.4–21.8) |

| Age moved to Downtown Eastside area (years) | 99 | 21.0 (19.2–23.4) |

| Age in first SRO (years) | 99 | 22.0 (20.0–24.5) |

^Median (interquartile range) reported for continuous variables. Proportion (n, %) reported for categorical variables

*There are some circumstances in British Columbia where individuals can receive both types of assistance

Table 1 summarizes demographic characteristics of the youth. In this group of young adults, 73.3% were identified as male. The majority (74.3%) had not completed high school and had a median monthly income of $720 CAD (interquartile range (IQR) $610–$908 CAD). Among those who reported sources of income, 65 (65.7%) were receiving income assistance and 40 (40.4%) were receiving long-term disability assistance. None had income from full-time employment. Only 8 (8.1%) people identified that they were employed part-time or marginally employed, where marginal employment is defined as the circumstance where earnings fail to achieve a minimal acceptable standard of living, either because they work too few hours (insufficient labour supply) or because their wages are too low.

Overall, this cohort also experienced frequent interactions with the health, social, and/or justice systems. The majority (65.7%) of participants had been previously hospitalized for a mental disorder. One quarter of the cohort reported living in foster care in the past and 20/101 (20%) reported previous incarceration.

Premature mortality

Over 229.8 person-years, three youth died. The coroner report for one youth identified multiple contributing illnesses, including mixed drug toxicity, psychosis not otherwise specified, and HCV. The coroner reports for the other two participants are pending. The standardized mortality ratio was calculated to be 18.6 (95% CI 6.0, 57.2) compared to age- and sex-matched Canadians.

Housing stability

The majority (87.0%) had a history of homelessness (see Table 1). The median age youth experienced first homelessness was 19.2 (IQR 17.4–21.8) years. We observed that most youth reported moving to the Downtown Eastside area between the ages of 19 and 23 years and gained residency in an SRO shortly after. In terms of housing stability during the follow-up period, 29 moved from SRO to homelessness. For 7 (24.1%) individuals, the first period of homelessness was preceded by time in jail, and for 6 (20.7%), by time in a treatment or recovery facility. Conversely, 14 youth moved from SROs to apartments; however, 4 (28.6%) returned to SRO (n = 2) or homelessness (n = 2) during the same follow-up period.

Substance use

All participants reported a history of non-prescription substance use (Table 2). All participants reported using alcohol and cannabis previously, with a median age of initiation of 13 and 14 years, respectively. Most participants reported using alcohol and cannabis regularly (at least 3 days per week) for several years. Although all youth reported past alcohol use, 18.8% were currently dependent.

Table 2.

Substance use characteristics prior to study entry

| Substance | Number | Ever used N (%) | Age of first drug use | Any period of regular use^ | Duration (years) of regular use^ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol | 99 | 99 (100) | 13.0 (12.0–16.0) | 69/94 (73.4%) | 4.0 (2.0–6.0) |

| Cannabis | 99 | 99 (100) | 14.0 (12.0–15.0) | 88/95 (92.6%) | 7.0 (4.8–12.0) |

| Inhalants | 99 | 36 (36.4) | 15.5 (13.0–19.0) | 9/34 (26.5%) | 1.0 (0.5–2.0) |

| Cocaine | 99 | 92 (92.9) | 17.0 (15.0–19.0) | 51/84 (60.7%) | 2.0 (2.0–5.0) |

| MDMA | 99 | 86 (86.9) | 17.0 (15.0–19.0) | 39/81 (48.1%) | 2.0 (1.0–3.0) |

| Opioids | 99 | 75 (77.3) | 17.0 (16.0–21.0) | 43/70 (61.4%) | 2.0 (1.0–5.0) |

| Methamphetamine | 99 | 82 (82.8) | 18.5 (15.0–21.0) | 56/78 (71.8%) | 4.0 (1.0–7.1) |

Median (interquartile range) reported for continuous variables. Proportion (n, %) reported for categorical variables

^Regular use defined as using three or more days per week

Almost every participant (92.9%) reported ever using cocaine, initiating use at age 17 (IQR 15–19). We also found high reported lifetime use of MDMA (86.9%), methamphetamine (82.8%), opioids (77.3%), and inhalants (36.4%). The median age of initiation for inhalants was lower (15.5 years) and methamphetamine was the highest at 18.5 years. Of the individuals who used methamphetamine, opioids, or cocaine, most (71.8%, 61.4%, and 60.7%, respectively) reported a history of regular use, often lasting for several years. Regarding current substance use and activity, participants had high rates of cannabis (59.4%), methamphetamine (43.6%), and heroin (31.0%) dependence at baseline assessment.

Clinical and functional profiles

Table 3 summarizes the participant clinical characteristics prior to and at study entry. We assessed lifetime mental disorder in all study participants, with all but one confirmed to have a mental disorder at the study entry date. Psychotic disorder was the most frequent diagnosis (60.4%). Mood disorders (27.7%), phobias (25.7%), post-traumatic stress disorder (15.8%), and generalized anxiety disorder (15.8%) were also common. Importantly, of the 93/101 who reported about mental health service utilization, nearly 30% reported that their mental health needs were not being met. Only 37.6% young adults reported seeing a psychiatrist and 25.8% reported seeing a family doctor for their mental health or substance use.

Table 3.

Participant clinical characteristics prior to and at study entry

| Clinical characteristic | Total N | Current n (%) | Lifetime n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mental disorders | |||

| Any mental disorder | 101 | 100 (99.0%) | 101 (100%) |

| Psychosis | 101 | 61 (60.4%) | 71 (70.3%) |

| Schizophrenia or schizoaffective | 28 (27.7%) | 28 (27.7%) | |

| Substance-induced psychosis | 21 (20.8%) | 31 (30.7%) | |

| Mood disorder | 101 | 28 (27.7%) | 55 (54.5%) |

| Major depressive disorder | 6 (5.9%) | 28 (27.7%) | |

| Bipolar disorder I | 9 (8.9%) | 12 (11.9%) | |

| Bipolar disorder II | 9 (8.9%) | 9 (8.9%) | |

| Anxiety disorder | 101 | 42 (41.6%) | 38 (37.6%) |

| Phobia (any) | 101 | 26 (25.7%) | 24 (23.8%) |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 101 | 16 (15.8%) | 16 (15.8%) |

| Panic disorder | 101 | 13 (12.9%) | 22 (21.8%) |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 101 | 16 (15.8%) | 16 (15.8%) |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | 101 | 3 (3.0%) | 3 (3.0%) |

| Eating disorder | 101 | 2 (2.0%) | 5 (5.0%) |

| Cognitive impairment disorder | 101 | 10 (9.9%) | 10 (9.9%) |

| Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder | 101 | 7 (6.9%) | 12 (11.9%) |

| Fetal alcohol syndrome | 101 | 1 (1.0%) | 1 (1.0%) |

| Any substance dependence* | 101 | 90 (89.1%) | 93 (92.1%) |

| Alcohol dependence | 101 | 19 (18.8%) | 39 (38.6%) |

| Stimulant dependence | 101 | 58 (57.4%) | 72 (71.2%) |

| Cocaine dependence | 19 (18.8%) | 47 (46.5%) | |

| Methamphetamine dependence | 44 (43.6%) | 52 (51.5%) | |

| Opioid dependence | 101 | 32 (31.7%) | 42 (41.6%) |

| Heroin dependence | 31 (31.0%) | 41 (40.6%) | |

| Other opioid dependence | 13 (13.0%) | 32 (32.0%) | |

| Cannabis dependence | 101 | 60 (59.4%) | 66 (65.3%) |

| Neurological illness | |||

| Movement disordera | 84 | 12 (14.3%) | |

| Parkinsonism, moderate or greater | 84 | 2 (2.4%) | – |

| Dyskinesia, moderate or greater | 84 | 6 (7.1%) | – |

| Dystonia, moderate or greater | 84 | 0 (0.0%) | – |

| Akathisia, moderate or greater | 85 | 9 (10.6%) | – |

| History of serious head injury | 98 | 54 (55.1%) | – |

| Traumatic brain injury (definite)b | 99 | 1 (1.0%) | – |

| Seizures in past year and/or current treatmentc | 99 | 11 (11.1%) | – |

| Brain infarction on MRI | 71 | 2 (2.8%) | – |

| Aneurysm on MR angiogram | 71 | 1 (1.4%) | – |

| Other neurological illnessd | 101 | 1 (1.0%) | – |

| Infectious disease | |||

| Anti-HIV antibody positive | 71 | 2 (2.8%) | – |

| Anti-HCV antibody positive | 73 | 23 (31.5%) | – |

| HCV viremia (qPCR) present | 17 | 10 (58.8%) | |

| Anti-HBV core antibody positive | 74 | 4 (5.4%) | – |

| HBV surface antigen positive | 74 | 1 (1.4%) | – |

| Mental health care utilization in 30 days prior to study entry | |||

| Unmet mental health care needs | 92 | 27 (29.3%) | – |

| Any mental health care | 93 | 66 (71.0%) | – |

| Professional seen | 93 | – | |

| Psychiatrist | 35 (37.6%) | – | |

| Family physician | 24 (25.8%) | – | |

| Other medical doctor | 1 (1.1%) | – | |

| Psychologist | 1 (1.1%) | – | |

| Nurse | 24 (25.8%) | – | |

| Social worker, counselor, or psychotherapist | 28 (30.1%) | – | |

| Other professional | 6 (6.5%) | – | |

| No professional care | 25 (26.9%) | – | |

| Number of professionals providing mental health support | 81 | 1 (0–2) | – |

| Hospitalized overnight for issues related to mental health and/or substance use | 93 | 10 (10.7%) | – |

| Detained overnight in jail for issues related to mental health and/or substance use | 92 | 9 (9.8%) | – |

| Functioning | |||

| RFS | 97 | 13.0 (11.0–14.0) | – |

| Work productivity | 2.0 (1.0–2.0) | – | |

| Independent living/self-care | 4.0 (3.0–4.0) | – | |

| Immediate social network relationships | 4.0 (4.0–5.0) | – | |

| Extended social network relationships | 3.0 (3.0–4.0) | – | |

| Marked limitation in at least 1 domain | 78 (80.4%) | – | |

| SOFAS | 97 | 40.0 (35.0–45.0) | – |

| Unemployment attributed to illness or disability | 100 | 58 (58.0%) | – |

| Multimorbidity | |||

| Number of multimorbid illnessese | 101 | 2 (1–3) | – |

*Excluding nicotine

aData indicate parkinsonism, dyskinesia, or akathisia symptoms representing a score of moderate or greater on the Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale or the Barnes Akathisia Scale

bData are for participants with evidence of previous traumatic brain injury (TBI) on MRI, or history of TBI (loss of consciousness ≥ 5 min or confusion ≥ 1 day) and persistent symptoms referable to TBI, including seizures or organic personality disorder

cMedical Review Questionnaire—either reported ever having seizures, fits or epilepsy, or ever being treated for epilepsy

dUnknown genetic syndrome with sensory-neural deafness

e12 illnesses, including stimulant dependence, alcohol dependence, opioid dependence, psychosis, movement disorder, cognitive disorder, brain infarction, traumatic brain injury, seizure disorder, HCV-positive qPCR, anti-HIV positive, anti-HBV positive

Neurological screening also revealed a history of serious head injury in 54/98 (55.1%) youth, including one participant with definite traumatic brain injury confirmed by persistent clinical sequelae. The prevalence of a history of seizure disorders in the last year and/or current seizure treatment was 11.1% of youth. Cerebral infarcts were identified by a qualified neuroradiologist on MRI in 2.8% of youth. Finally, baseline serology results indicated 2.9% participants confirmed HIV positive, 1.4% had active HBV infection, and 31.5% confirmed HCV positive, with the majority (58.8%) living with active HCV infection.

Psychosocial functioning was markedly impaired among these individuals as measured by both the RFS and SOFAS. Notably, 78/97 (80.4%) participants assessed had severe limitations (score of ≤ 2/7) in at least one of four RFS domains (work productivity, independent living/self-care, and immediate and extended social network relationships). Illness and/or disability was commonly (58.0%) reported as the primary reasons for current unemployment.

Multimorbidity and real-world functioning

Overall, these young adults living in SROs had a median of two morbidities (IQR 1–3) at study entry (Table 3). The most common pairs of co-occurring illnesses were stimulant dependence with psychosis (40.6%), with anxiety (23.8%), or with opioid dependence (22.8%). Psychosis, stimulant dependence, and opioid dependence occurred together in 17.8% of participants. Notably, nearly all participants with active HCV infection (9/10, 90.0%) or seizures (9/11, 81.8%) also had stimulant dependence.

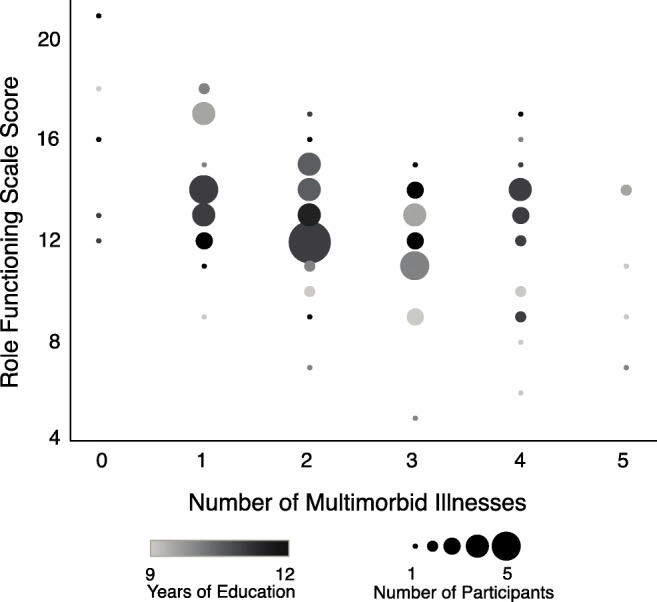

Within the cohort, the number of multimorbid illnesses did not differ by age (ρ(99) = 0.167, p = 0.094) or gender (χ2 (1,100) = 0.132, p = 0.716). The number of multimorbid illnesses was associated with poorer psychosocial functioning as measured by RFS (ρ(95) = − 0.373, p < 0.001) (Fig. 1). Multimorbidity was associated with worse scores in all four functional domains: work productivity (ρ(95) = − 0.309, p = 0.002), independent living/self-care (ρ(95) = − 0.282, p = 0.005), immediate social network relationships (ρ(95) = − 0.272, p = 0.007), and extended social network relationships (ρ(95) = − 0.291, p = 0.004). Likewise, multimorbidity was associated with poorer SOFAS score (ρ(95) = − 0.268, p = 0.008) and being unemployed (χ2 (1,99) = 4.211, p = 0.040). Participants with a greater number of co-morbidities were less likely to have completed high school (χ2 (1,101) = 6.146, p = 0.013) and had completed fewer grades (ρ(99) = − 0.221, p = 0.026). The level of completed education was also associated with work productivity (ρ(95) = 0.215, p = 0.035), but not independent living and social network relationships, or total psychosocial functioning ability (p > 0.05). Stimulant dependence (χ2 (1,95) = 8.088, p = 0.004), active HCV infection (χ2 (1,65) = 7.627, p = 0.006), psychosis (χ2 (1,95) = 5.644, p = 0.018), and opioid dependence (χ2 (1,95) = 4.601, p = 0.032) may be particularly important contributors to poor psychosocial functioning (RFS) in this sample. Sensitivity analyses found similar results whether analyses were limited to only participants living in SRO at baseline (n = 96) (data not shown), whether subjects with any missing scans, tests, or assessments (n = 48) were excluded from analyses, or whether mood and anxiety disorders were included in the multimorbidity count (Supplemental Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Association between Role Functioning Scale total score and number of multimorbid illnesses. Size of circle indicates the number of participants. Shade of colour indicates the highest grade completed

Discussion

Youth in this study show remarkably poor health, and social and functional disadvantages consistent with adult populations who are homeless or living in SROs (Kidd et al. 2017; Jones et al. 2015; Vila-Rodriguez et al. 2013; Honer et al. 2017). First, three mortality events were observed in the study follow-up period, translating to an age-specific mortality rate 18.6 times greater than the Canadian mortality rates reported for this age group (Statistics Canada 2009). We found a high prevalence of psychosis, mood disorders, phobias, post-traumatic stress disorder, and anxiety. Nearly 30% of participants reported that their mental health needs were not being met. Untreated mental illness in young adults—which is more likely to persist if a person is homeless or marginally housed (Kidd et al. 2017; Forchuk et al. 2016)—is strongly associated with mental illness in adulthood (McGorry et al. 2013; Wolitzky-Taylor et al. 2017). The age of first homeless episode had a clear association with experiencing greater risk and mental distress (Kidd et al. 2017). As many nations move towards a system of care that is patient oriented (Canadian Institutes of Health Research 2015), engagement with this population at an early age should be prioritized.

A second finding was the high rates of substance use and dependence, particularly cannabis, methamphetamine, and heroin. The rates were strikingly higher than Canadian youth not living in marginalized housing. For example, 100% of the sample reported having used cannabis at least once, when compared to 34% (95% CI 28.5–39.5%) of Canadian youth (Statistics Canada 2011). The age of initiation of cannabis use in the current group was 14.0 years, compared to the Canadian average of 15.6 years (95% CI 15.3–15.9) (Statistics Canada 2011). Every individual in the study also reported alcohol use, with the age of initiation at 13.0 years, compared to the Canadian reported age of 16.0 years (95% CI 15.7–16.2). Further, compared to the 4.8% and 0.4% of Canadian youth reporting cocaine and methamphetamine use, respectively (Statistics Canada 2011), the overwhelming majority of our sample reported having used these substances (92% and 82%, respectively). These trends have been observed elsewhere (Cheng et al. 2016a; DeBeck et al. 2016). Key factors contributing to increased and early substance dependence in this population include: multigenerational poverty; early substance exposure through family or close friends; inadequate access to health, addictions, and social programs; lack of focus of community programs on substance use prevention; and low levels of education (DeBeck et al. 2016; Corring et al. 2016; Cheng et al. 2016b).

Several other risk factors were identified, including low educational achievement, high levels of unemployment, risk-taking behaviours, crime, self-harm, and inadequate self-care. These data are compounded by significant health impairments, injuries, and infectious diseases. Specifically, the youth self-reported high levels of head injury (55.1%), in addition to high rates of recent seizures or current treatment for a seizure disorder (11.1%). This is approximately 18 times the Canadian prevalence rate of 0.6% (Statistics Canada 2011). Seizure activity and substance misuse may be inter-related in this cohort, similar to that in the literature (Brown et al. 2011; Alldredge et al. 1989). In regard to infectious disease, the proportion of youth with confirmed HCV infection (31.5%) was high compared to that in the Canadian population (0.6–0.7%) (Statistics Canada 2012). Despite dramatic reductions of HCV infection rates reported between 1996 and 2012 (Grebely et al. 2014), unstable housing continues to be an independent predictor associated with HCV infection (Grebely et al. 2014).

Young adulthood is a period marked by increased autonomy, independent decision-making, and the development of behaviours that can be carried forward. Understanding the competing priorities of young adults living in marginalized housing may inform a system of care that helps youth achieve developmentally appropriate milestones while learning to self-manage their health (McGorry et al. 2013). Youth living in SROs have a long history of interactions with health and social systems. With nearly two thirds of the sample having been hospitalized, 20% incarcerated, and 25% in foster care, it can be argued that opportunities may have been missed for supportive interventions—particularly enhanced financial, health, and psychosocial supports to forestall marginalization.

Canada has a long history of public health being involved in housing (Lang 1912; Labonte 1986). Opportunity exists for the coordination of efforts and policy to target healthy, sustainable, strength-focused, recovery-oriented outcomes for this population (Barbic et al. 2018). Global examples for coordinated youth-centred programs exist (Hetrick et al. 2017; Rickwood et al. 2014), including a new Canadian initiative called Foundry (www.foundrybc.ca). A recent review of these “one-stop shop” services revealed that young people with complex needs, such as those in this study, require early integration of services with rapid access to specialist social and health services (Hetrick et al. 2017).

This study has limitations. The primary purpose was to collect longitudinal data among adults living in SROs in Vancouver. As a result, we were limited to collecting data for young adults aged 18–29 years, which precluded access to important information from younger individuals in SROs. Another limitation is that the self-report measures used in this study were primarily designed and tested for adult populations not living in social housing. This may affect the precision of the results. Given the health and social consequences identified in the study, further studies of the trajectories and recovery needs of youth living in marginalized housing are required to address their unique needs in a timely fashion.

Conclusions

Young adults living in marginal housing in Vancouver, one of Canada’s most expensive housing markets, experience high levels of physical and mental illness, substance dependence, and social vulnerability. The young people in this study frequently reported a history of homelessness, incarceration, foster care, and hospitalization. Although ostensibly these factors may be viewed as risks for long-term vulnerability—specifically mortality and morbidity—they may also be viewed as opportunities to engage vulnerable youth in care and rehabilitation. In order to do so, immediate public health and whole-government strategies and action are needed to prioritize and address the needs of young vulnerable Canadians.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 15 kb)

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

Dr. Vila-Rodriguez has received Advisory Board fees from Janssen. Dr. Panenka is on the board of directors (Abbatis Bioceuticals) or scientific advisory boards (Medipure Pharmaceuticals and Vinergy Inc) of three local emerging biotechnology companies. Dr. Rauscher has received advisory board fees from Hofmann-La Roche. Dr. Barr has received consulting fees or sat on Advisory Boards for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, and Roche. Dr. Procyshyn has received speaking and Advisory Board fees from Janssen, Lundbeck, and Otsuka. He has also received Royalties as the Principal Editor of The Clinical Handbook of Psychotropic Drugs. Dr. MacEwan has received speaking or consulting fees or sat on advisory boards for Apotex, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Pfizer, and Sunovion and has received research grant support from Janssen. Dr. Honer has received consulting fees or sat on Advisory Boards for In Silico, Lundbeck, Otsuka, and Alphasights. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

For the purposes of this paper, we define “young adults” or “youth” as the developmental stage in late adolescence to early adulthood (15–29 years). See Mental Health Commission of Canada, “Making transitions a priority.”

Many terms exist to describe marginal housing. Of note, the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation describes “severe housing need” as “Housing below standards refers to housing that falls short of at least one of the adequacy, affordability, and suitability housing standards”.

This cohort excluded youth < 18 years of age.

Skye P. Barbic and Andrea A. Jones share co-first authorship.

References

- Alldredge BK, Lowenstein DH, Simon RP. Seizures associated with recreational drug abuse. Neurology. 1989;39(8):1037–1039. doi: 10.1212/WNL.39.8.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aubry T, Nelson G, Tsemberis S. Housing First for people with severe mental illness who are homeless: a review of the research and findings from the At Home—Chez soi demonstration project. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2015;60(11):467–474. doi: 10.1177/070674371506001102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbic, S., Kidd, S. A., Durisko, Z. T., Yachouch, S., Rathithran, G., McKenzie, K. (2018). What are the personal recovery needs of community-dwelling Canadians with mental illness? Preliminary findings from the Canadian Personal Recovery Outcome Measurement (C-PROM) study. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health. (in press).

- BC Non-Profit Housing Association and M. Thomson Consulting. (2017). Homeless Count in Metro Vancouver Final Report. 2017; http://www.metrovancouver.org/services/regional-planning/homelessness/HomelessnessPublications/2017MetroVancouverHomelessCount.pdf. Accessed October 31st, 2017.

- Brown JW, Dunne JW, Fatovich DM, Lee J, Lawn ND. Amphetamine-associated seizures: clinical features and prognosis. Epilepsia. 2011;52(2):401–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02924.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research (2015). Canada’s strategy for patient-oriented research—patient engagement. Framework. http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/48413.html. Accessed 28 Sept 2017.

- Chamberlain C, Mackenzie D. Understanding contemporary homelessness: issues of definition and meaning. The Australian Journal of Social Issues. 1992;27:274–297. doi: 10.1002/j.1839-4655.1992.tb00911.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng T, Johnston C, Kerr T, Nguyen P, Wood E, DeBeck K. Substance use patterns and unprotected sex among street-involved youth in a Canadian setting: a prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:4. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2627-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng T, Kerr T, Small W, Nguyen P, Wood E, DeBeck K. High prevalence of risky income generation among street-involved youth in a Canadian setting. The International Journal on Drug Policy. 2016;28:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran BN, Stewart AJ, Ginzler JA, Cauce AM. Challenges faced by homeless sexual minorities: comparison of gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender homeless adolescents with their heterosexual counterparts. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(5):773–777. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.92.5.773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbiere M, Lanctot N, Lecomte T, et al. A pan-Canadian evaluation of supported employment programs dedicated to people with severe mental disorders. Community Mental Health Journal. 2010;46(1):44–55. doi: 10.1007/s10597-009-9207-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corring DJ, Whittall S, MustinPowell J, Jarmain S, Chapman P, Sussman S. Mental health system transformation: drivers for change, organizational preparation, engaging partners and outcomes. Healthcare Quarterly. 2016;18(Suppl):6–11. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2016.24441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBeck, K., Kerr, T., Nolan, S., Dong, H., Montaner, J., & Wood, E. (2016). Inability to access addiction treatment predicts injection initiation among street-involved youth in a Canadian setting. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 11(1). 10.1186/s13011-015-0046-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Forchuk C, Dickins K, Corring DJ. Social determinants of health: housing and income. Healthcare Quarterly. 2016;18(Suppl):27–31. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2016.24479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaetz, S., Donaldson, J., Richter, T., Gulliver, T. (2013) The State of Homelessness in Canada. Toronto. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/health-concerns/drug-prevention-treatment/canadian-alcohol-drug-use-monitoring-survey.html. Accessed 18 July 2017.

- Goodman SH, Sewell DR, Cooley EL, Leavitt N. Assessing levels of adaptive functioning: the Role Functioning Scale. Community Mental Health Journal. 1993;29(2):119–131. doi: 10.1007/BF00756338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grebely J, Lima VD, Marshall BD, et al. Declining incidence of hepatitis C virus infection among people who inject drugs in a Canadian setting, 1996-2012. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e97726. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetrick SE, Bailey AP, Smith KE, et al. Integrated (one-stop shop) youth health care: best available evidence and future directions. The Medical Journal of Australia. 2017;207(10):S5–s18. doi: 10.5694/mja17.00694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honer, W. G., Cervantes-Larios, A., Jones, A. A., et al. (2017). The Hotel Study—clinical and health service effectiveness in a cohort of homeless or marginally housed persons. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 10.1177/0706743717693781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Jones AA, Vila-Rodriguez F, Leonova O, et al. Mortality from treatable illnesses in marginally housed adults: a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2015;5(8):e008876. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd SA, Karabanow J, Hughes J, Frederick T. Brief report: youth pathways out of homelessness—preliminary findings. Journal of Adolescence. 2013;36(6):1035–1037. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd, S. A., Gaetz, S., & O’Grady, B. (2017). The 2015 National Canadian Homeless Youth Survey: mental health and addiction findings. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 10.1177/0706743717702076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kirst M, Zerger S, Wise Harris D, Plenert E, Stergiopoulos V. The promise of recovery: narratives of hope among homeless individuals with mental illness participating in a Housing First randomised controlled trial in Toronto, Canada. BMJ Open. 2014;4(3):e004379. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirst M, Zerger S, Misir V, Hwang S, Stergiopoulos V. The impact of a Housing First randomized controlled trial on substance use problems among homeless individuals with mental illness. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2015;146:24–29. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozloff, N., Stergiopoulos, V., Adair, C. E., et al. (2016a). The unique needs of homeless youths with mental illness: baseline findings from a Housing First Trial. Psychiatric Services. 10.1176/appi.ps.201500461. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kozloff, N., Adair, C. E., Palma Lazgare, L. I., et al. (2016b). “Housing First” for homeless youth with mental illness. Pediatrics, 138(4), e20161514. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kumar MM, Nisenbaum R, Barozzino T, Sgro M, Bonifacio HJ, Maguire JL. Housing and sexual health among street-involved youth. The Journal of Primary Prevention. 2015;36(5):301–309. doi: 10.1007/s10935-015-0396-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labonte R. Social inequality and healthy public policy. Health Promotion (Oxford, England) 1986;1(3):341–351. doi: 10.1093/heapro/1.3.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang WR. Housing conditions in Canada. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 1912;2(6):487–493. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latimer EA, Rabouin D, Cao Z, et al. Costs of services for homeless people with mental illness in 5 Canadian cities: a large prospective follow-up study. CMAJ Open. 2017;5(3):E576–e585. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20170018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus L, Chettiar J, Deering K, Nabess R, Shannon K. Risky health environments: women sex workers’ struggles to find safe, secure and non-exploitative housing in Canada’s poorest postal code. Social Science & Medicine (1982) 2011;73(11):1600–1607. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manwell LA, Barbic SP, Roberts K, et al. What is mental health? Evidence towards a new definition from a mixed methods multidisciplinary international survey. BMJ Open. 2015;5(6):e007079. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mar MY, Linden IA, Torchalla I, Li K, Krausz M. Are childhood abuse and neglect related to age of first homelessness episode among currently homeless adults? Violence and Victims. 2014;29(6):999–1013. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.VV-D-13-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGorry P, Bates T, Birchwood M. Designing youth mental health services for the 21st century: examples from Australia, Ireland and the UK. The British Journal of Psychiatry. Supplement. 2013;54:s30–s35. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.119214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie K. How do social factors cause psychotic illnesses? Canadian Journal of Psychiatry / Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie. 2013;58(1):41–43. doi: 10.1177/070674371305800108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morosini PL, Magliano L, Brambilla L, Ugolini S, Pioli R. Development, reliability and acceptability of a new version of the DSM-IV Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS) to assess routine social functioning. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2000;101(4):323–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piat M, Barker J, Goering P, Piat M, Barker J, Goering P. A major Canadian initiative to address mental health and homelessness. The Canadian Journal of Nursing Research. 2009;41(2):79–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poremski, D., & Hwang, S. W. (2016). Willingness of Housing First participants to consider supported-employment services. Psychiatric Services. 10.1176/appi.ps.201500140. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Poremski, D., Rabouin, D., Latimer, E. (2015a). A randomised controlled trial of evidence based supported employment for people who have recently been homeless and have a mental illness. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 41(2), 217–224. 10.1007/s10488-015-0713-2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Poremski, D., Woodhall-Melnik, J., Lemieux, A. J., Stergiopoulos, V. (2015b). Persisting barriers to employment for recently housed adults with mental illness who were homeless. Journal of Urban Health, 93(1), 96–108. 10.1007/s11524-015-0012-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Province of British Columbia . Residential Tenancy Act [SBC 2002] CHAPTER 78. Victorial: Queen’s Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rickwood DJ, Telford NR, Parker AG, Tanti CJ, McGorry PD. headspace—Australia’s innovation in youth mental health: who are the clients and why are they presenting? The Medical Journal of Australia. 2014;200(2):108–111. doi: 10.5694/mja13.11235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team (2017). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. http://www.R-project.org/. Accessed February 1st, 2017.

- Roy E, Haley N, Leclerc P, Sochanski B, Boudreau JF, Boivin JF. Mortality in a cohort of street youth in Montreal. JAMA. 2004;292(5):569–574. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.5.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadowski LS, Kee RA, VanderWeele TJ, Buchanan D. Effect of a housing and case management program on emergency department visits and hospitalizations among chronically ill homeless adults: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2009;301(17):1771–1778. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah J, Mizrahi R, McKenzie K. The four dimensions: a model for the social aetiology of psychosis. The British Journal of Psychiatry : The Journal of Mental Science. 2011;199(1):11–14. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.090449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somers JM, Moniruzzaman A, Rezansoff SN. Migration to the Downtown Eastside neighbourhood of Vancouver and changes in service use in a cohort of mentally ill homeless adults: a 10-year retrospective study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(1):e009043. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. (2009). Age-specific mortality rates per 1,000 population by age group and sex, Canada, provinces and territories, 2009. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/91-209-x/2013001/article/11785/tbl/tbl02-eng.htm. Accessed July 18th, 2017.

- Statistics Canada (2011). Canadian Alcohol and Drug Use Monitoring Survey. In: Canada H, ed. Ottawa, Canada.

- Statistics Canada. (2012). The Canadian Community Health Survey: Mental Health 2012. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/daily-quotidien/130918/dq130918a-eng.htm. Accessed August 19th, 2016.

- Stergiopoulos V, Gozdzik A, O’Campo P, Holtby AR, Jeyaratnam J, Tsemberis S. Housing First: exploring participants’ early support needs. BMC Health Services Research. 2014;14:167. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Educational SaCOU. (2015). What do we mean by youth? http://www.unesco.org/new/en/social-and-humansciences/.

- Vila-Rodriguez F, Panenka WJ, Lang DJ, et al. The hotel study: multimorbidity in a community sample living in marginal housing. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2013;170(12):1413–1422. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12111439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willi TS, Lang DJ, Honer WG, et al. Subcortical grey matter alterations in cocaine dependent individuals with substance-induced psychosis compared to non-psychotic cocaine users. Schizophrenia Research. 2016;176(2–3):158–163. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolitzky-Taylor K, Sewart A, Vrshek-Schallhorn S, et al. The effects of childhood and adolescent adversity on substance use disorders and poor health in early adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2017;46(1):15–27. doi: 10.1007/s10964-016-0566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 15 kb)