Abstract

Objectives

Canadians have reason to care about indoor air quality as they spend over 90% of the time indoors. Although indoor radon causes more deaths than any other environmental hazard, only 55% of Canadians have heard of it, and of these, 6% have taken action. The gap between residents’ risk awareness and adoption of actual protective behaviour presents a challenge to public health practitioners. Residents’ perception of the risk should inform health communication that targets motivation for action. In Canada, research about the public perception of radon health risk is lacking. The aim of this study was to describe residents’ perceptions of radon health risks and, applying a theoretical lens, evaluate how perceptions correlate with protection behaviours.

Methods

We conducted a mixed online and face-to-face survey (N = 557) with both homeowners and tenants in Ottawa-Gatineau census metropolitan area. Descriptive, correlation, and regression analyses addressed the research questions.

Results

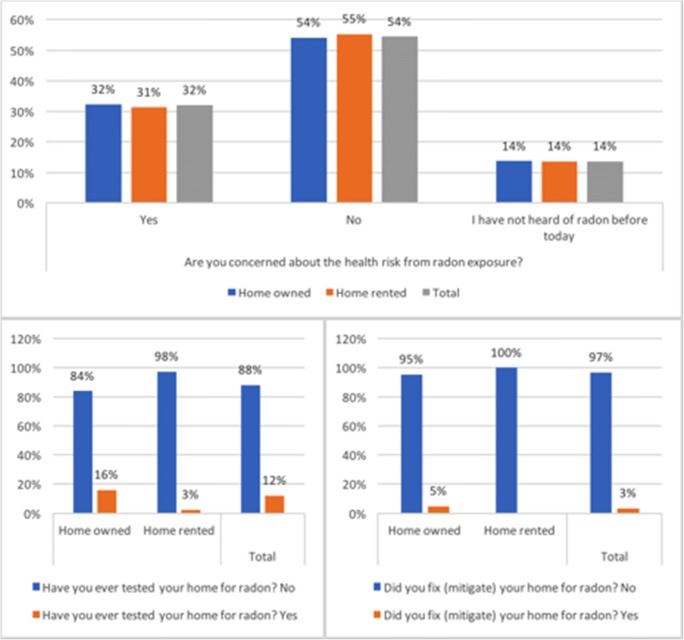

Compared to the gravity of the risk, public perception remained low. While 32% of residents expressed some concern about radon health risk, 12% of them tested and only 3% mitigated their homes for radon. Residents’ perceptions of the probability and severity of the risk, social influence, care for children, and smoking in home correlated significantly with their intention to test; these factors also predicted their behaviours for testing and mitigation.

Conclusion

Health risk communication programs need to consider the affective aspects of risk perception in addition to rational cognition to improve protection behaviours. A qualitative study can explore the reasons behind the gap between testing and mitigation.

Keywords: Air pollution, Indoor, Radon, Risk, Perception, Canada

Résumé

Objectifs

Les Canadiens ont de bonnes raisons de se préoccuper de la qualité de l’air intérieur, car ils passent plus de 90 % de leur temps à l’intérieur. Bien que le radon domiciliaire (RD) cause plus de décès que tout autre risques environnementaux, seulement 55 % des Canadiens en ont déjà entendu parler, et d’entre eux seulement 6 % ont pris des mesures concrètes pour l’éradiquer. L’écart entre la sensibilisation aux risques et la prise de mesures de protection réelles par les résidents constitue un défi pour les professionnels de la santé publique. La perception des résidents face aux risques associés au RD devrait guider la communication en matière de santé pour cibler la motivation. Au Canada, très peu d’études portant sur les perceptions de la population face aux risques associés au RD ont été réalisées. Le but de cette étude est de décrire les perceptions qu’entretiennent les occupants de bâtiments résidentiels face aux risques pour la santé associée au RD et évaluer comment ces perceptions sont corrélées aux comportements de protection, notamment en appliquant la théorie de la motivation et de la protection.

Méthodes

Nous avons réalisé une enquête mixte en ligne et en personne (n = 557) auprès de propriétaires et de locataires de la région d’Ottawa-Gatineau. Des analyses descriptives, corrélationnelles et des analyses de régressions ont été effectuées en fonction de nos questions de recherche.

Résultats

En comparaison à la gravité des risques, les perceptions du public demeurent faibles. Bien que 32 % des résidents ont exprimé des préoccupations au sujet du danger que représente le radon pour la santé, seulement 12 % d’entre eux ont réalisé des tests à domicile et seulement 3 % ont pris des actions concrètes pour réduire les risques. Les perceptions des résidents quant à la probabilité et à la gravité des risques du RD sur leur santé, l’influence sociale, les soins prodigués aux enfants, ainsi que le tabagisme à la maison étaient significativement corrélées avec leur intention de réaliser un test. Ces facteurs ont également prédit leurs comportements en lien avec l’utilisation du test et les actions entreprises pour diminuer les risques.

Conclusion

Les programmes de communication sur les risques du RD sur la santé doivent tenir compte des aspects affectifs associés à la perception des risques, en plus de tenir compte du niveau de connaissances pour améliorer les comportements de protection. Une recherche de nature qualitative serait nécessaire pour explorer les raisons qui expliquent l’écart entre le taux d’utilisation des tests de détection et les actions concrètes pour diminuer les risques.

Mots-clés: Pollution de l’air, Radon domiciliaire, Perceptions du risque, Canada

Introduction

Canadians have reason to care about indoor air quality as they spend over 90% of the time indoors (Leech et al. 2002). Having the world’s most abundant reserves of high-grade uranium (U238), Canadian land emits higher levels of soil gas radon (Rn222) than any other country (Natural Resources of Canada 2014). In urban areas, people of lower income levels are most likely to rent poorly ventilated basements or houses that are in contact with the ground (Briggs et al. 2008). Airtight energy–efficient homes have pressure gradients between the heated indoors and chilly outdoors, which create conditions for harmful gases in the soil to enter the house (Henderson et al. 2012). Inside such dwellings, the radioactive gas builds up during the long winter months when doors and windows remain closed. Radon further degrades by emitting alpha particles which upon inhalation prompt mutations of lungs’ DNA leading to cancer (Noh et al. 2016).

In Canada, about 7% of homes have radon gas above the federal reference level of 200 Bq/m3 (Health Canada 2014). Contingent on the long winter, construction design, urban location, and radiological anomaly in Gatineau Park, Ottawa-Gatineau residents face an elevated risk of exposure to radon. There is no threshold for the carcinogenic effect of radon, and most lung cancers occur from exposure to concentrations below this set level (Peterson et al. 2013), and such exposures are reported to increase the incidence of lung cancer (Henderson et al. 2012). Annually, at least 3200 Canadians die from radon-induced lung cancer, accounting for 16% of all (smokers, ex-smokers, and non-smokers) lung cancer deaths and making radon the leading cause of lung cancer deaths among non-smokers and the second highest among smokers (Statistics Canada 2016). Compared to the general population, children (increased breathing rate), women (passing prolonged time indoor), and men smokers (synergistic effect of radon) with lower socio-economic status are disproportionately affected by exposure to radon (Hill et al. 2006). Lung cancer risk from radon exposure is up to ten times higher among smokers compared to non-smokers due to a synergistic effect (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency 2012). Children in households with less-educated parents are more likely to be exposed to second-hand smoking (Klepeis et al. 2013).

Due to the public perception of low risk, radon has the highest impact on the health of the population among all environmental pollutants (Signorelli and Limina 2002). Despite multiple efforts, the National Radon Program (NRP) lags behind with regard to the desired public uptake (Statistics Canada 2016). In 2015, at least 55% of all Canadian households indicated hearing about radon, but only 6% of them tested their homes for it (Statistics Canada 2016). The gap between risk awareness and actual testing rates presents a challenge to public health practitioners. So far, practitioners assumed that better-communicated information, enforced guidelines, and tax rebates would be among the best solutions for radon health risk (hereafter “the risk”) management (Spiegel and Krewski 2002). However, studies in the United States (Hahn 2014), the United Kingdom (Poortinga et al. 2011), and Ireland (Dowdall et al. 2016) showed that taking regulatory actions, offering rebates, and even providing free test kits and services could not significantly improve the program uptake. Thus, the key question—how to motivate the target population individually and collectively—remains unanswered (Hevey 2017). Even after informing (cognitive awareness) residents that their houses might have a high level of radon and it might pose a serious health threat, protective actions remained low (Field et al. 1993). Social science research has argued that the success of a population-level health promotion program is contingent upon the motivation of key decision makers at the household level (Lorang 2001). We believe that residents’ perception of the risk should inform health communication programs targeting motivation. In Canada, research about the public perception of radon health risk is lacking. Therefore, in this study, we employed theory-based tools to understand the determinants related to residents’ perceptions of the risk. We sought to determine whether they were motivated to change their behaviour due to cognitive awareness alone, or whether there was an effect of emotional influence related to the limbic part of the brain controlling affective behaviours (Lorang 2001). Such understanding can guide strategies to enhance uptake of the program. This article reports the quantitative findings of a mixed methods study conducted in winter 2018.

Theoretical framework

Exposure to a health risk communication creates a dual appraisal process: (a) threat appraisal and (b) coping appraisal (Witte 1992). Threat appraisal is the assessment of the chance (susceptibility) of contracting a disease and evaluating its seriousness (severity). A coping appraisal comprises response efficacy and self-efficacy. Response efficacy is the expectation that carrying out recommendations will eliminate the threat. Self-efficacy denotes the belief in an individual’s ability to accomplish suggested actions without failure (Witte 1992). Thus, the stronger a threat appraisal, the more an individual engages with the coping behaviour.

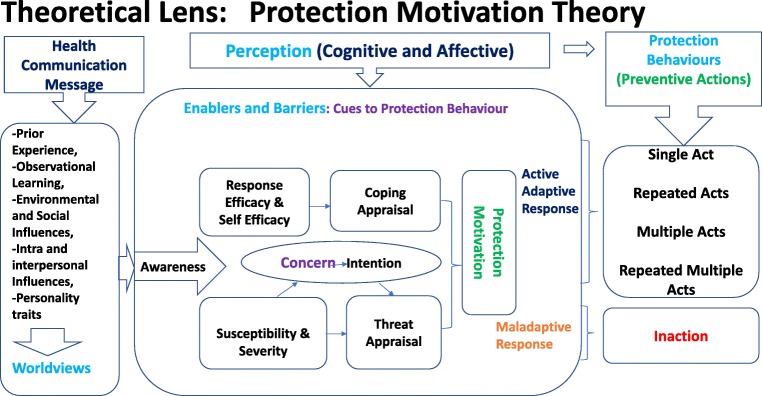

The Protection Motivation Theory (PMT) specifies how these two perception processes lead an individual to adopt either an active adaptive or maladaptive coping mechanism in response to a health risk (Rogers 1983). These, in turn, were fortified by observational learning (someone died from radon-induced lung cancer), internal persuasions (lifestyle, smoking), intrapersonal traits (“caring for family”), and external environment (“social influence”) leading to fear arousal and developing the intention to take action. These dual perceptions combined with multiple influences generate a broader perception (“worldview”) about the risk that shapes the protection motivation and ultimately leads an individual to the actual adoption of coping behaviours (Boer and Seydel 1996). Alternatively, the maladaptive responses place people at additional risk as they miss the opportunity to take preventive actions. Therefore, the PMT has four dynamics: (a) perceived probability (exposure to radon), (b) perceived severity of a threatening event (lung cancer), (c) response efficacy of the recommended intervention (testing and mitigation can eliminate the threat), and (d) self-efficacy (confidently taking action). Thus, protection motivation is the result of informed threat and coping appraisal, which facilitates the adoption of protective health behaviours (Boer and Seydel 1996) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Theoretical lens: Protection Motivation Theory (Rogers 1983)

Appraising homeowners’ perceptions within the above fundamental logics of PMT might help to enhance understanding of the motivation dynamics, and identify strategies to influence protection behaviours. Therefore, this study examined the PMT components in a Canadian context to provide insight into homeowners’ perceptions of radon health risk. The PMT has been previously applied in health research to influence and predict various health-related behaviours related to reducing alcohol consumption, enhancing healthy lifestyles, improving diagnostic health behaviours, and preventing diseases (Boer and Seydel 1996). A thorough understanding of homeowners’ perception of the risk through this theoretical lens can advance the PMT research agenda to promote awareness of health risks and encourage innovative approaches by policymakers and professionals to address the issue.

Research questions and hypothesis

The primary research question was as follows: How do Ottawa-Gatineau residents perceive and act in response to the health risk of radon? In addition to inquiring about the risk perception phenomena and related worldviews, we sought to answer the following subquestions:

-

i)

What are the associations of residents’ intention to test for radon, with the following variables: Perceived radon health risk susceptibility, severity, synergistic risk of radon with smoking, smoking in home, care for children, and social influence?

-

ii)

How do these variables (mentioned in “i”) predict residents’ efficacy in adopting protection behaviours (testing and mitigation of homes for radon)?

We hypothesized that there would be significant associations between perceived radon health risk susceptibility, severity, synergistic risk perception, smoking in home, care for children, and social influence, with residents’ intention to test for radon. Likewise, these variables will predict residents’ adoption of protective behaviours.

Methods

Sampling and data collection protocol

We surveyed homeowners and tenants (included for the first time in such a study as a control group) of Ottawa and Gatineau census metropolitan area (CMA) who met the following criteria: resident in a house with a basement or a house in contact with the ground for over one year. Participants were randomly selected from the residents’ panel with Qualtrics, a platform frequently used in standard research studies (Farris et al. 2018; Glodstein et al. 2018). Participants received email invitations, along with a link to the online survey in both French and English. We conducted an equivalent, face-to-face version of the survey using iPads. Some participants filled out the survey and returned it by email, and others completed the face-to-face version in the community settings to cover up respondents who could not take the interview online. The University of Ottawa’s Institutional Review Board approved the study and data collection protocols (file number: H10-17-03). Participation was voluntary and anonymous. All participants went through the informed consent form and checked option in affirmative to be able to go ahead with the survey. We estimated the sample size to be 560.

Instrument and measures

The 41-item survey instrument included a mix of closed- and open-ended questions. We measured the independent variables such as residents’ “perception of probability” (do you think radon may be present in your home?) and “perception of severity” (how seriously does radon affect our health?) of the risk across homeowners and tenants. We also measured internal factors such as “smoking in home” (does anybody smoke cigarettes in your home?) and “synergistic risk perception” (does smoking enhance the risk of radon for lung cancer?). The intrapersonal factor included “care for children” (does at least one child live or spend over four hours in the basement or ground floor?) and external persuasion like “social influence” (how many people do you know who have tested their homes for radon?). Although the last three variables were measured in previous research in different settings (Butler et al. 2017; Huntington-Moskos et al. 2016), our pilot qualitative study conducted in winter 2017 helped to shape the questionnaire in a Canadian context. We employed an anchored relative scale rather than Likert scales as previous research has identified the former as being more sensitive than the latter (Hampson et al. 2003). The anchored relative scale quantified grading points with specific narratives rather than the inexplicit ranges. The open-ended questions explored residents’ depth of knowledge and points of view regarding various aspects of radon health risk. The outcome (dependent) variables included “intention to test” (have you the intention to test your home for radon?), “tested home for radon” (have you ever tested your home for radon?), and “mitigated home for radon” (did you fix or mitigate your home after testing?). The efficacy was enquired by asking about repeated action (did you test after mitigation?). The open-ended questions explored residents’ general awareness (what do you know about radon?) and points of view regarding risk management (is it an individual or overall societal problem? Then, who should be responsible for fixing it?).

We collected socio-demographic (control) variables such as age, gender, race/ethnicity, education level, total household income, and home ownership or tenancy to compare how the risk perceptions vary with these features. We followed the criteria used in the National Households and the Environment Survey (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency 2012) to classify gender, age group, race/ethnicity, education, and income groups. Participants voluntarily identified themselves and chose their groups. We conducted a reliability analysis of our perception scales (susceptibility and severity of the risk) and obtained an internal consistency score of 0.74 (Cronbach’s alpha) with a 2-item adapted scale.

Analysis

Respondents completing < 80% of the survey accounted for less than 10% of the total sample and were excluded from further analysis. Because our focus was on Ottawa-Gatineau residents, we eliminated all participants who completed the survey from outside this area. With an over 85% response rate, our final sample (N = 557) consisted of 394 (71%) homeowners and 163 (29%) tenants.

We conducted descriptive and inferential analyses using IBM SPSS 24, setting the confidence intervals at 95% and alpha at 0.05 (two-tailed) overall. Descriptive statistics included frequency distributions to summarize the data. We conducted univariate analyses for the entire sample, subgroup (homeowners and tenants), and outcome variables. Initially, we did post hoc analyses to test the sensitivity of the methods used. We used Pearson’s chi-square test of associations and likelihood ratios to determine whether the risk-related perception variables were associated with residents’ intention and actual performance of protection behaviours (testing and mitigating). We arranged the data to meet all relevant assumptions related to multicollinearity, outliers, normality, homoscedasticity, and independence of residuals (Tabachnick and Fidell 2013). We conducted ordinal and binary logistic regressions to identify predictors of intention to test and actual testing and mitigating behaviours (both dichotomized into “yes” and “no”). We examined the fit of our proposed model, controlled for age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, total household income, and home ownership. In the regression analysis, variables were entered simultaneously and forward conditional method was used in each of the models.

Results

Sample characteristics

Our sample proportionately represented socio-demographic features of Ottawa-Gatineau CMA residents.

Table 1 presents these characteristics and their associations with residents’ intention to test their homes for radon. We found significant associations (p < 0.001) of residents’ homeownership, gender, and age groups with their intention to test for radon. However, homeowners, females, and older adults had greater intention to test than tenants, males, and young adults. Although European Canadians, university-educated, and lower-middle-income residents showed a higher level of intention to test their houses for radon, these associations were not statistically significant. However, when it comes to taking actual protective actions, males and young adults exceeded their counterparts in testing, though the university-educated and the upper-middle-income group of people took the lead in mitigating their homes for radon (Table 2).

Table 1.

Associations of socio-demographic characteristics with residents’ intention to test homes for radon

| Residents’ intention to test homes for radon | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-demographic characteristics | Total sample (N = 557) | Yes | No | Associations (significance) | |||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | χ2 (p)‡ | |

| Homeownership | |||||||

| Owners | 394 | 71 | 179 | 80 | 215 | 65 | 14.18* (0.000§) |

| Tenants | 163 | 29 | 46 | 20 | 117 | 35 | |

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 291 | 52 | 88 | 39 | 203 | 61 | 29.82* (0.000§) |

| Female | 224 | 40 | 121 | 54 | 103 | 31 | |

| Not willing to identify | 42 | 8 | 16 | 7 | 26 | 8 | |

| Age groups (years) | |||||||

| 18–24 | 83 | 15 | 46 | 20 | 37 | 11 | |

| 25–34 | 58 | 10 | 35 | 16 | 23 | 7 | |

| 35–44 | 59 | 11 | 33 | 15 | 26 | 8 | 85.76* (0.000§) |

| 45–54 | 85 | 15 | 50 | 22 | 35 | 11 | |

| 55–64 | 106 | 19 | 9 | 4 | 97 | 29 | |

| 65 and above | 166 | 30 | 52 | 23 | 114 | 34 | |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||

| European Canadian | 375 | 67 | 146 | 65 | 229 | 69 | |

| First Nations | 14 | 2.5 | 5 | 2 | 9 | 3 | 1.95* (0.583) |

| Visible minorities | 120 | 21 | 55 | 24 | 65 | 20 | |

| Prefer not to answer | 48 | 9 | 19 | 8 | 29 | 9 | |

| Education | |||||||

| High school or less | 70 | 13 | 25 | 11 | 45 | 14 | |

| College | 135 | 24 | 54 | 24 | 81 | 24 | 7.32† (0.062) |

| University | 346 | 62 | 146 | 65 | 200 | 60 | |

| Prefer not to answer | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 2 | |

| Income groups | |||||||

| Lowest subsistence | 60 | 11 | 28 | 12 | 32 | 10 | |

| Lower middle, non-skilled | 147 | 26 | 60 | 27 | 87 | 26 | |

| Skilled working class | 94 | 17 | 36 | 16 | 58 | 17 | 2.09* (0.836) |

| Middle class | 106 | 19 | 44 | 20 | 62 | 19 | |

| Upper middle | 68 | 12 | 28 | 12 | 40 | 12 | |

| Prefer not to answer | 82 | 15 | 29 | 13 | 53 | 16 | |

*Pearson’s chi-square (χ2)

†Likelihood ratio

‡Asymptotic significance (two-sided)

§Significant association

Table 2.

Associations of socio-demographic characteristics with residents’ actual testing and mitigation of homes for radon

| Residents ever tested homes for radon | Mitigated homes for radon | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-demographic characteristics | Total sample (N = 557) | Yes | No | Associations (significance) | Total sample (N = 557) | Yes | No | Associations (significance) | ||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | χ2 (p‡) | N | % | N | % | N | % | χ2 (p‡) | |

| Homeownership | ||||||||||||||

| Owners | 394 | 71 | 63 | 94 | 331 | 68 | 19.96* (0.000§) | 394 | 71 | 17 | 100 | 377 | 70 | 7.69* (0.006§) |

| Tenants | 163 | 29 | 4 | 6 | 159 | 32 | 163 | 29 | 0 | 0 | 163 | 30 | ||

| Gender | ||||||||||||||

| Male | 291 | 52 | 34 | 51 | 257 | 52 | 2.82* (0.244) | 291 | 52 | 10 | 56 | 281 | 52 | 1.52* (0.467) |

| Female | 224 | 40 | 31 | 46 | 193 | 40 | 224 | 40 | 8 | 44 | 216 | 40 | ||

| Not willing to identify | 42 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 40 | 8 | 42 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 42 | 8 | ||

| Age groups (years) | ||||||||||||||

| 18–24 | 83 | 15 | 19 | 28 | 64 | 13 | 18.59† (0.000§) | 83 | 15 | 6 | 35 | 77 | 14 | 17.43† (0.004§) |

| 25–34 | 58 | 10 | 11 | 16 | 47 | 10 | 58 | 10 | 3 | 18 | 55 | 10 | ||

| 35–44 | 59 | 11 | 10 | 15 | 49 | 10 | 59 | 11 | 5 | 29 | 54 | 10 | ||

| 45–54 | 85 | 15 | 9 | 13 | 76 | 15 | 85 | 15 | 2 | 12 | 83 | 15 | ||

| 55–64 | 106 | 19 | 5 | 8 | 101 | 21 | 106 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 106 | 20 | ||

| 65 and above | 166 | 30 | 13 | 19 | 153 | 31 | 166 | 30 | 2 | 6 | 164 | 31 | ||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||||||

| European Canadian | 375 | 67 | 36 | 54 | 339 | 69 | 6.65* (0.08) | 375 | 67 | 10 | 56 | 365 | 68 | 2.48† (0.479) |

| First Nations | 14 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 12 | 3 | 14 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 3 | ||

| Visible minorities | 120 | 21 | 20 | 30 | 100 | 20 | 120 | 21 | 6 | 33 | 114 | 21 | ||

| Prefer not to answer | 48 | 9 | 9 | 3 | 39 | 8 | 48 | 9 | 2 | 11 | 46 | 8 | ||

| Education | ||||||||||||||

| High school or less | 70 | 13 | 7 | 10 | 63 | 13 | 0.439* (0.932) | 70 | 13 | 1 | 6 | 69 | 13 | 1.63† (0.652) |

| College | 135 | 24 | 17 | 25 | 118 | 24 | 135 | 24 | 4 | 22 | 131 | 24 | ||

| University | 346 | 62 | 42 | 63 | 304 | 62 | 346 | 62 | 13 | 72 | 333 | 62 | ||

| Prefer not to answer | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 1 | ||

| Income groups | ||||||||||||||

| Lowest subsistence | 60 | 11 | 11 | 16 | 49 | 10 | 5.73* (0.333) | 60 | 11 | 3 | 18 | 57 | 11 | 5.24† (0.387) |

| Lower middle, non-skilled | 147 | 26 | 19 | 28 | 128 | 26 | 147 | 26 | 4 | 23 | 143 | 26 | ||

| Skilled working class | 94 | 17 | 10 | 15 | 84 | 17 | 94 | 17 | 1 | 6 | 93 | 17 | ||

| Middle class | 106 | 19 | 9 | 13 | 97 | 20 | 106 | 19 | 3 | 18 | 103 | 19 | ||

| Upper middle | 68 | 12 | 12 | 18 | 56 | 12 | 68 | 12 | 5 | 29 | 63 | 12 | ||

| Prefer not to answer | 82 | 15 | 7 | 10 | 75 | 15 | 82 | 15 | 1 | 6 | 81 | 15 | ||

*Pearson’s chi-square (χ2)

†Likelihood ratio

‡Asymptotic significance (two-sided)

§Significant association

Regarding indoor air quality, more people expressed concern about dust/dust mites (29%) and mould (27%) than radon (20%). Among the residents concerned about radon, 39% described it as a radioactive gas. Their primary sources of information were media (46%), Health Canada (13%), and Internet browsing (8.5%).

Figure 2 shows that overall only 32% of residents had concern about exposure to radon health risk, 12% tested for radon, and just 3% mitigated their homes for the risk. Among those who mitigated, 94% retested after mitigation (p < 0.001), showing the efficacy of adopting protection behaviours. Although 3% of tenants also tested, none of them mitigated their houses for radon. Our analysis showed that 93% of homeowners and 85% of tenants spent more than four hours either in the basement or on the ground floor. This variable had a significant correlation with testing for homeowners (p = 0.01) but not for tenants (p = 0.904). Both smoking in home and synergistic risk perception were significantly associated with the intention to test by homeowners (χ2 = 107.12, 172.42; p < 0.001, < 0.001) and tenants (χ2 = 42.17, 88.22; p < 0.001, < 0.001). Our data showed that 21.8% of homeowners and 5% of tenants had at least one child living in the basement or on the ground floor, a situation that had strong associations with the intention to test for both homeowners (χ2 = 81.82, p < 0.001) and tenants (χ2 = 13.08, p < 0.001). Similar strong associations were found between social influence and intention to test for both homeowners (χ2 = 41.66; p < 0.001) and tenants (χ2 = 4.54, p = 0.03).

Fig. 2.

Residents’ concern about radon health risk, actual testing, and mitigation behaviours

When asked about their worldview about radon, the majority (28%) of respondents said that they are concerned about their health since radon exposure affects everybody. Over 26% said that radon affects individual persons, so they (homeowners) are responsible for fixing it. About 25% said that property owners and tenants should get a tax rebate according to their income level for mitigating their homes. Nearly 21% said that as this is a population health problem, the government is responsible for fixing it. These opinions did vary significantly by residents’ gender (χ2 = 35.20, p < 0.001), age (χ2 = 29.24, p < 0.01), education (χ2 = 32.36, p < 0.001), and income levels (χ2 = 27.49, p < 0.02) but not with homeownership and race/ethnicity.

Results to answer the research questions

We assumed that there would be significant associations between perceived radon health risk susceptibility, severity, synergistic risk perception, smoking in home, care for children, and social influence, with residents’ intention to test for radon. Likewise, these variables will predict residents’ adoption of protection behaviours that are to take actual actions such as testing and mitigation of homes for radon.

Table 3 presents the outcomes of ordinal and binary logistic regressions that show the perception variables were significantly associated with residents’ intention to test for radon as well as predicted residents’ efficacy in actually adopting the protection behaviours.

Table 3.

Ordinal and binary regression modeling: residents’ perception of radon health risk predicting their intention to test, actual testing, and mitigating homes for radon

| Variables | Intention to test | Tested home for radon | Mitigated home for radon | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate/β | SE | Wald/ Std. β | p | Estimate/β | SE | Wald/ Std. β | p | Estimate/β | SE | Wald/ Std. β | p | |

| Perceived susceptibility of radon risk* | 2.09 | 0.65 | 10.32 | 0.001§ | 18.83 | 0.36 | 2762.37 | 0.000§ | 18.55 | 0.66 | 787.52 | 0.000§ |

| Perceived severity of radon risk† | 2.56 | 0.42 | 36.85 | 0.000§ | 2.46 | 0.62 | 15.56 | 0.000§ | 20.31 | 0.66 | 936.99 | 0.000§ |

| Synergistic risk perception‡ | − 3.68 | 0.37 | 97.79 | 0.000§ | − 3.4 | 0.41 | 67.91 | 0.000§ | − 2.53 | 0.64 | 15.7 | 0.000§ |

| Smoke in home‡ | − 2.08 | 0.35 | 35.73 | 0.000§ | − 3.57 | 0.39 | 81.7 | 0.000§ | − 4.02 | 1.03 | 15.12 | 0.000§ |

| Care for children‡ | − 2.07 | 0.49 | 17.75 | 0.000§ | − 5.45 | 0.55 | 98.97 | 0.000§ | − 4.62 | 1.04 | 19.92 | 0.000§ |

| Social influencec | 2.32 | 0.60 | 14.73 | 0.000§ | − 6.5 | 0.60 | 118.84 | 0.000§ | − 4.97 | 1.04 | 22.89 | 0.000§ |

SE standard error of β, Std. β standardized beta, χ2 chi-square statistic, df degree of freedom

*Ordinal regression model fit statistics for intention to test are likelihood = 21.47, p < 0.001, and χ2 = 100.43, df = 4

†Ordinal regression model fit statistics for intention to test are likelihood = 20.09, p < 0.001, and χ2 = 75.04, df = 3

‡Binary regression model, Hosmer and Lemeshow test’s χ2 = 47.42, p < 0.001, df = 4

§Values refer to the predictors that are significant in the model

Discussion

Our purpose in this study was to describe residents’ perceptions of radon health risks and to evaluate how perceptions correlated with protection behaviours, applying the protection motivation theoretical lens. We examined the perception of radon health risk of an illustrative sample of Ottawa-Gatineau residents. In doing so, we compared the obtained measures on the perception variables of interest with residents’ socio-demographic features and identified mixed associations with their intention to test and actual protection behaviours. Our analyses showed significant associations of perception variables with residents’ intention to test for radon. The same variables meaningfully predicted residents’ actual protection behaviours and, thus, confirmed the hypotheses. These findings correspond with the results of studies conducted by Hahn et al. (Hahn et al. 2014) in the US and Butler et al. (Butler et al. 2017) in the UK.

A few quantitative studies in Canada have assessed public perception of environmental health risks in general. Krewski et al. (2006) conducted a national survey on health risk perception and looked into 30 common health hazards. A more focused study by Spiegel and Krewski (2002) evaluated health risk perception of radon along with three other health hazards affecting residents of high-radon areas in Canada. They examined residents’ compliance with the radon guideline and concluded that the Canadian Radon Guideline is not effectively prompting homeowners to reduce radon exposure (Spiegel and Krewski 2002). Our findings support this conclusion that compared to the gravity of the risk, residents’ perception level remains low. Although those studies credibly supported the federal government initiative to develop a guideline, no follow-up study purposefully focused on radon health risk perception to support the National Radon Program of Health Canada. This study successfully fills that scholarly gap in the literature.

As stated before, we included tenants for the first time in a study and this led to some notable findings. Although few (29%) in number, like homeowners, tenants also tested their houses for radon due to having concern for their children living in the basement. However, none of them mitigated their homes. An apparent reason for this is the lack of authority to do so; nonetheless, there exists no law that gives tenants the right to hold property owners responsible for such mitigation. Homeowners who mitigated their homes similarly tended to have children sleeping in the basement; additionally, they had observed others taking such mitigation action or had heard of people who had radon-induced lung cancer. Application of these perception points may, however, create fears and apprehensions among tenants and occupants of public buildings who, for the time being, are not required to measure and mitigate radon. These can also dissipate the ambiguity in the program on radon health communication and help to deliver the health communication messages to the right audience in the right manner and, thus, can open up a new path for the public health preventive interventions.

Again, the significant correlation between having children living in the basement or on the ground floor and taking actual protective behaviours might have biological plausibility. Here, the targeted health communication message that can stir the affection part relating to the inner cortex or limbic brain would yield a better outcome compared to those emphasizing only the rational cognitive part pertaining to the neocortex. These findings warrant further exploration of social influence through an in-depth qualitative study to test whether motivation works under the affective familial or social influence that can open the way to make protective behaviours a norm in our society.

Although our study targeted one metropolitan area, the Ottawa-Gatineau CMA spans two provinces in the capital region and covers both English- and French-speaking populations and, thus, filled a critical gap in measuring residents’ perception of radon health risk across two official linguistic groups in Canada. Thereby, a systematic understanding of homeowners’ perceptions through the protection motivation theoretical lens advances the PMT research agenda and puts forward evidence for innovative approaches to be considered by policymakers and professionals in addressing the critical public health issue of radon.

Limitations

Our study is limited in demographic scope. We may have overlooked demographic diversities and cultural subtleties in selecting the sample online that could have skewed our results. Our sample did include tenants, but the lack of variability in the scores may have affected the relationship between them. Furthermore, residents who took the survey did so voluntarily and included those who have access to the Internet; therefore, we collected proportional responses offline using iPad to include the remaining 10% of residents with no access to the Internet. Our study included only residents in Ottawa-Gatineau and should be understood in the context of this population. Though the sample was in proportion to the demographic features of the Canadian population, we cannot claim it to be representative of the whole Canadian demography. A future study with a national representative sample would provide stronger evidence base to support the design of national health communication programs focusing on residential radon risk mitigation.

Conclusion

In this study, we tested the hypothesis that those with higher levels of perceived susceptibility, severity, synergistic risk perception, smoking in home, care for children, and social influence would be more likely to have the intention to test as well as to demonstrate protection behaviours regarding testing and mitigating their homes. Statistical analyses of our survey data confirmed this hypothesis in a Canadian context. Variables reflecting public perception of radon health risk did not always convert into the protection behaviours that could be explained by biological plausibility. Nonetheless, through the protection motivation theoretical lens, we have now understood that residents’ perceptions of the health risks of radon are a marker of intention to test their house for radon and are a clear predictor of actual risk mitigation behaviours.

Acknowledgements

Our thanks to all study participants for taking part. Thank you from Khan (first author) to his co-supervisor, Dr. Samia Chreim, for her valuable feedback; to Drs. Tracey O’Sullivan and Louise Bouchard for their generous guidance; and to colleague Nicole Bergen for pre-review. We thank David Buetti and Émilie Lessar for revising the French abstract. Grateful thanks to Kelley Bush and Deepti Bijlani from Health Canada for reviewing the survey questionnaire and kindly supporting the first author’s community health campaigns.

This article reports the quantitative part of a mixed methods research project conducted for a doctoral dissertation during winter 2018 at the University of Ottawa.

Compliance with ethical standards

The University of Ottawa’s Institutional Review Board approved the study and data collection protocols (file number: H10-17-03).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Selim M. Khan, Phone: +1 819-271-7561, Email: skhan196@uottawa.ca

Daniel Krewski, Phone: 613-562-5381, Email: dkrewski@uottawa.ca.

James Gomes, Phone: (613) 562-5800, Email: james.gomes@uottawa.ca.

Raywat Deonandan, Phone: 613-562-5800, Email: raywat.Deonandan@uOttawa.ca.

References

- Boer H, Seydel ER. Protection motivation theory. In: Connor M, Norman P, editors. Predicting health behavior. Buckingham: Open University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Briggs D, Abellan JJ, Fecht D. Environmental inequity in England: small area associations between socio-economic status and environmental pollution. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67(10):1612–1629. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler, K.M., Rayens, M.K., Wiggins, A.T., Rademacher, K.B., Hahn, E.J. (2017). Association of smoking in the home with lung cancer worry, perceived risk, and synergistic risk. In: Oncology nursing forum. NIH Public Access. p. E55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dowdall A, Fenton D, Rafferty B. The rate of radon remediation in Ireland 2011-2015: establishing a baseline rate for Ireland’s National Radon Control Strategy. Journal of Environmental Radioactivity. 2016;16(2–163):107–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvrad.2016.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farris, S. G., DiBello, A. M., Bloom, E. L., & Abrantes, A. M. (2018). A confirmatory factor analysis of the smoking and weight eating episodes test (SWEET). International Journal of Behavioral Medicine [Internet]. 10.1007/s12529-018-9717-0 (Accessed April 23, 2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Field RW, Kross BC, Vust LVJ. Radon testing behavior in a sample of individuals with high home radon screening measurements. Risk Analysis. 1993;13:441–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.1993.tb00744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glodstein, S. L., DiMarco, M., Painter, S., & Ramos-Marcuse, F. (2018). Advanced practice registered nurses attitudes toward suicide in the 15- to 24-year-old population. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care [Internet]. 10.1111/ppc.1227 (Accessed April 23, 2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hahn EJ. Residential radon testing intentions, perceived radon severity, and tobacco use. Journal of Environmental Health. 2014;76(6):42–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn EJ, Adkins SM, Wright AP, et al. Dual home screening and tailored environmental feedback to reduce radon and second-hand smoke: an exploratory study. Journal of Environmental Health. 2014;76(6):156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampson SE, Andrews JA, Barckley M, Lee ME, Lichtenstein E. Assessing perceptions of synergistic health risk: a comparison of two scales. Risk Analysis. 2003;23(5):1021–1029. doi: 10.1111/1539-6924.00378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Canada. (2014). Radon: reduction guide for Canadians. Available at: www.hc-sc.gc.ca/ewh-semt/alt_formats/pdf/pubs/radiation/radon_canadians-canadiens/radon_canadians-canadien-eng.pdf (Accessed November 11, 2017).

- Henderson SB, Kosatski T, Barn P. How to ensure that national radon survey results are useful for public health practice. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2012;103(3):231–234. doi: 10.1007/BF03403819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hevey, D. (2017). Radon risk and remediation: a psychological perspective. Frontiers in Public Health, 5. 10.3389/fpubh.2017.00063 (Accessed March 15, 2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hill WG, Butterfield P, Larsson LS. Rural parents’ perceptions of risks associated with their children’s exposure to radon. Public Health Nursing. 2006;23(5):392–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2006.00578.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huntington-Moskos L, Rayens MK, Wiggins A, Hahn EJ. Radon, secondhand smoke, and children in the home: creating a teachable moment for lung cancer prevention. Public Health Nursing. 2016;33(6):529–538. doi: 10.1111/phn.12283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klepeis NE, Hughes SC, Edwards RD, Allen T, Johnson M, Chowdhury Z, et al. Promoting smoke-free homes: a novel behavioral intervention using real-time audiovisual feedback on airborne particle levels. PLoS One. 2013;8:e73251. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krewski D, Lemyre L, Turner MC, Lee JEC, Dallaire C, Bouchard L, et al. Public perception of population health risks in Canada: health hazards and sources of information. Human and Ecological Risk Assessment. 2006;12(4):626–644. doi: 10.1080/10807030600561832. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leech JA, Nelson WC, Burnett RT, et al. It’s about time: a comparison of Canadian and American time-activity patterns. Journal of Exposure Analysis and Environmental Epidemiology. 2002;12:427–432. doi: 10.1038/sj.jea.7500244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorang, P.S. (2001). A conceptualization and empirical assessment of the consumer testing decision process. Dissertation Abstracts. International Journal Humanities Social Science; 61(7-A).

- Natural Resources of Canada. (2014). About uranium. Available at: http://www.nrcan.gc.ca/energy/uranium-nuclear/7695 (Accessed January 15, 2018).

- Noh, J., Sohn, J., Cho, J., Kang, D. R., Joo, S., Kim, C., & Shin, D. C. (2016). Residential radon and environmental burden of disease among non-smokers. Annals of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 28(1). 10.1186/s40557-016-0092-5 (Accessed March 20, 2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Peterson E, Aker A, Kim JH, Li Y, Brand K, Copes R. Lung cancer risk from radon in Ontario, Canada: how many lung cancers can we prevent? Cancer Causes & Control. 2013;24(11):2013–2020. doi: 10.1007/s10552-013-0278-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poortinga W, Bronstering K, Lannon S. Awareness and perceptions of the risks of exposure to indoor radon: a population-based approach to evaluate a radon awareness and testing campaign in England and Wales: awareness and perceptions of the risks of exposure to indoor radon. Risk Analysis. 2011;31(11):1800–1812. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2011.01613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers RW. Cognitive and physiological processes in fear appeals and attitude change: a revised theory of protection motivation. In: Cacioppo J, Petty R, editors. Social Psychophysiology. New York: Guilford Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Signorelli C, Limina RM. Environmental risk factors and epidemiologic study. [article in Italian] Annali di Igiene. 2002;14(3):253–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel JM, Krewski D. Using willingness to pay to evaluate the implementation of Canada’s residential radon exposure guideline. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2002;93(3):223–228. doi: 10.1007/BF03405005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. (2016). Environment fact sheets: radon awareness in Canada. Available at: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/16-508-x/16-508-x2016002-eng.htm (Accessed February 20, 2018).

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. 6. Boston: Pearson; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2012). A citizen’s guide to radon: a guide to protecting yourself and your family from radon. Available at: http://bit.ly/2fBt15k (Accessed December 26, 2017).

- Witte, K. (1992). Putting the fear back into fear appeals: the extended parallel process model. Communication Monographs, 59, 329–349. 10.1080/03637759209376276 (Accessed May 18, 2017).