Abstract

Circular RNA (circRNA) is endogenous non-coding RNA (ncRNA) with a covalently closed circular structure. It is mainly generated through RNA alternative splicing or back-splicing. CircRNA is known in the majority of eukaryotes and very stable. However, knowledge of the circRNA involved in regulating cashmere fineness is limited. Skin samples were collected from Liaoning cashmere goats (LCG) and Inner Mongolia cashmere goats (MCG) during the anagen period. For differentially expressed circRNAs, RNA sequencing was performed, and the analysis led to an identification of 17 up-regulated circRNAs and 15 down-regulated circRNAs in LCG compared with MCG skin samples. In order to find the differentially expressed circRNAs in LCG, we carried out qPCRs on 10 candidate circRNAs in coarse type skin of LCG (CT-LCG) and fine type skin of LCG (FT-LCG). Four circRNAs: ciRNA128, circRNA6854, circRNA4154 and circRNA3620 were confirmed to be significantly differential expression in LCG. Also, a regulatory network of circRNAs-miRNAs was bioinformatically deduced and may help to understand molecular mechanisms of potential circRNA involvement in regulating cashmere fineness.

Subject terms: Genetics, Zoology

Introduction

The goat (Capra hircus), is economically important livestock, used in the production of cashmere, meat, and milk. The Liaoning cashmere goat breed (LCG) is famous for high fiber production1, whereas Inner Mongolia cashmere goats (MCG) produce high-quality cashmere fiber compared with other cashmere goat breeds2. In recent years, the characteristics of cashmere fiber have received special attention in that they play an obvious role in cashmere quality. Several studies indicated that coding and noncoding genes were associated with the regulation of cashmere growth3–5. In addition, several important pathways have been demonstrated to be related to the formation of cashmere fiber6–8, for instance, Wnt, NF-κB, Shh, Notch and other signaling pathways9–13. However, there are no systematic studies on the molecular regulation of cashmere fineness in the skin.

Circular RNAs (CircRNAs), a new class in the eukaryotic transcriptome, are characterized by the 3′ and 5′ ends of which are covalently linked in a covalently closed loop without free ends14,15. CircRNAs, with the unique circular structure, are more stable and have longer half-lives than mRNAs16,17. More recently, many studies have demonstrated that circRNAs contribute to the generation of cancer18,19, regulate gene expression in many biological processes, and participate in the occurrence and development of various diseases20. In a study by Li et al. identified 6,113 circRNAs from muscles of sheep by RNA-seq21, and a total of 10,226 circRNAs were detected from pituitary glands of sheep by RNA-seq22. Zheng et al. revealed that circRNAs can act as a microRNA sponge to isolate microRNA by competing with targeted mRNA23. Another investigation determined that 151 circRNAs were differently expressed in ORFV-infected goat skin fibroblast cells and uninfected cells24. The mechanism of potential involvement of circRNAs in cashmere formation remains unclear.

In the present study, we aim to find differentially expressed circRNAs in cashmere goat skin. We used RNA-seq to identify the circRNAs in LCG and MCG skin samples, and hundreds of circRNAs were obtained in goat skins. To further explore the relationship between circRNAs with cashmere fineness and its potential role, we also generated a regulatory network that took into account interactions between these circRNAs and miRNAs. Our findings may offer a new insight into cashmere goat circRNAs and their potential involvement in regulation of cashmere fineness.

Results

Identification of circRNAs in cashmere goat skin

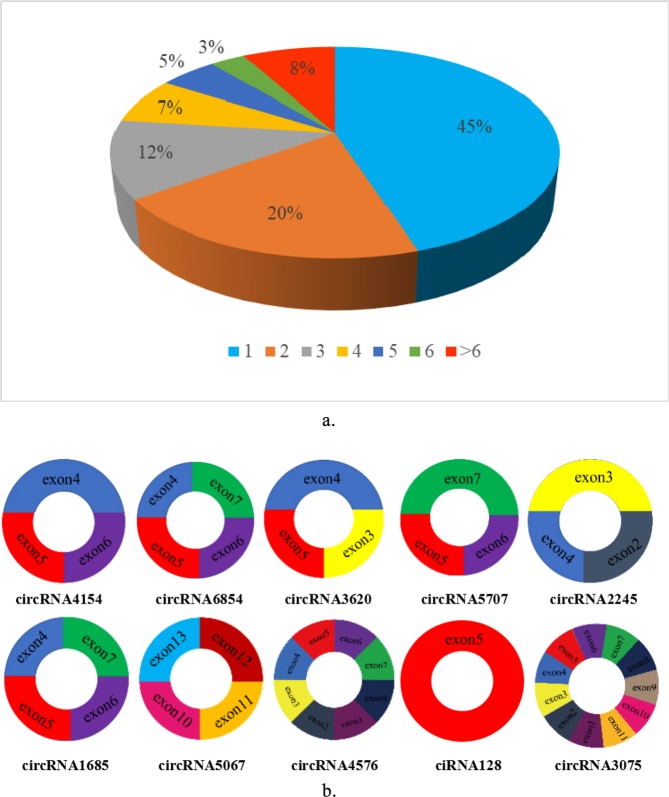

In order to understand the differentially expressed circular RNAs in goat skin, we performed RNA-seq analysis processes in LCG and MCG skin. Total clean reads were obtained after deleting the low-quality raw reads, the mapping ratios of clean reads were 91.27% and 84.93% in LCG and MCG. A total of 13,320 circRNAs were identified from the RNA-seq data, including 610 circular intronic RNAs (ciRNAs) (Fig. 1a). There are 7,531 and 8,943 circRNAs detected in LCG and MCG libraries, respectively. The MCG samples (49.43%) were compared with the LCG samples (58.31%), and the percentage of mapped sequence reads that could be aligned with the exon region were significantly lower (Fig. 1b). The lengths of circRNAs ranged from 200 to 400 bp in LCG and MCG (Fig. 1c), and the majority of circRNAs contained 2–7 exons (Fig. 1d). We found that the genomic loci, from which the circRNAs were derived, were over 29 autosomes and X chromosomes in the two types of samples.

Figure 1.

Information on circRNAs from RNA-seq in Liaoning cashmere goats (LCG) and Inner Mongolia cashmere goats (MCG) skin tissue. (a) The types of circRNAs. (b) Distribution of exons, introns, and intergenic circRNAs. (c) The number of exons in circRNAs. (d) The lengths of circRNAs.

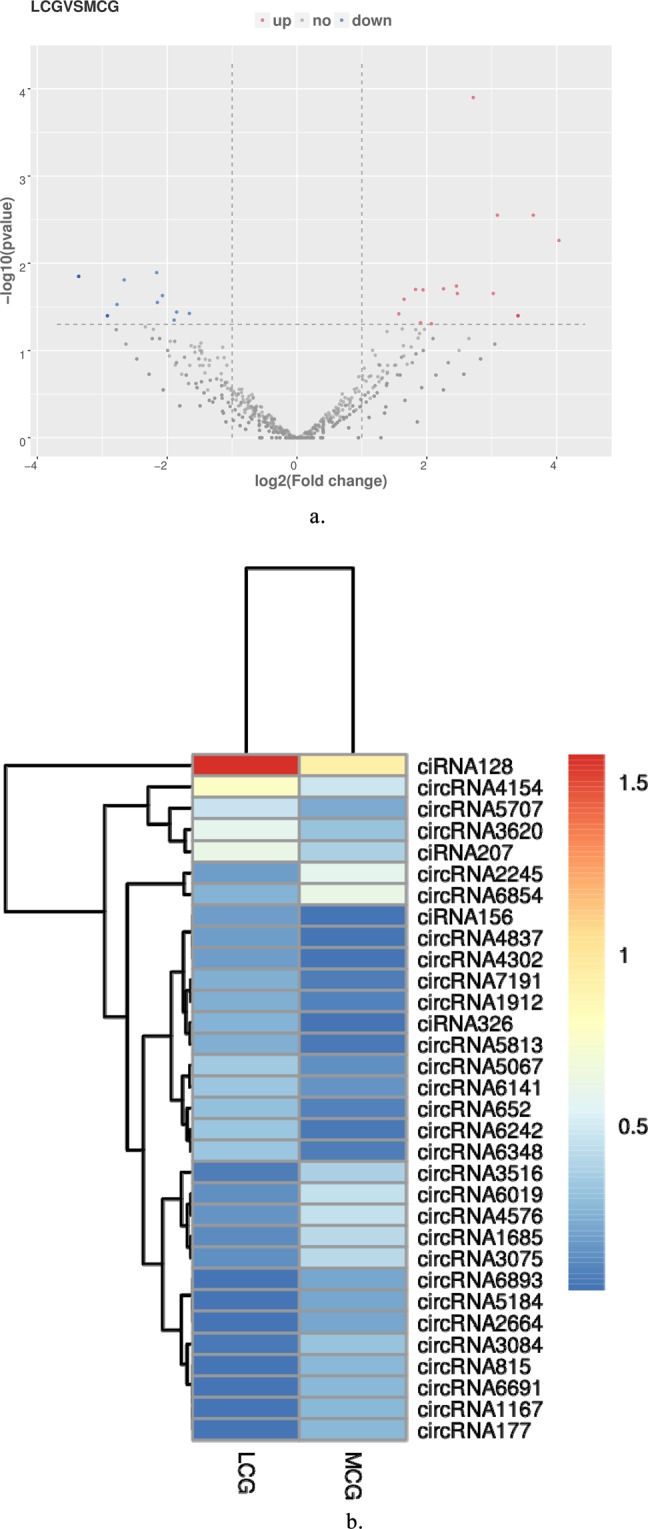

Differentially expressed circRNAs in LCG and MCG

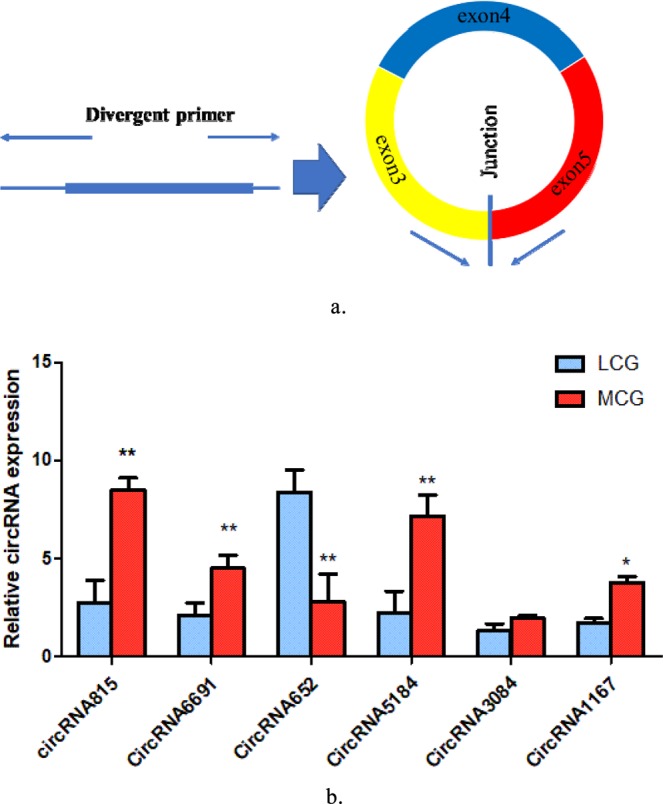

A total of 32 circRNAs were identified as differentially expressed when we compared the data between LCG and MCG skin tissues (Fig. 2a), of which 17 circRNAs were significantly up-regulated and 15 circRNAs were significantly down-regulated in the LCG (Tables 1 and 2). Then, we used a cluster heat-map analysis of differentially expressed circRNAs to better understand their potential relationship (Fig. 2b). To assure the accuracy of RNA-seq strategy, six differentially expressed circRNAs were randomly selected and specific qPCR primers were designed within the circRNAs’ junction regions (Fig. 3a). The expression levels of circRNAs determined by qPCR and RNA-seq are highly consistent (Fig. 3b). This meaning the significant reliability of RNA-seq data acquisition and subsequent analysis procedures in this study.

Figure 2.

Differentially expressed circRNAs in LCG and MCG. (a) Volcano map of differentially expressed circRNAs. Red dots indicate up-regulation and blue dots indicate down-regulation. (b) Cluster heatmap of differentially expressed circRNAs. The sample is represented by the abscissa and the log value of circRNA expression is regarded by the ordinate, which means that the heatmap is drawn from log10 of circRNA expression. The highly expressed circRNA is indicated by red, meanwhile, the lowly expressed circRNA is presented by blue.

Table 1.

Up-regulated circRNAs in LCG and MCG.

| circRNA ID | host gene | LCG (FPKM) | MCG (FPKM) | log2FC | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ciRNA128 | TCHH | 36.95 | 7.14 | 2.72 | 0.00012611 |

| circRNA4154 | HOMER3 | 5.05 | 2.04 | 1.65 | 0.02588325 |

| ciRNA207 | HCFC1R1 | 3.14 | 1.34 | 1.57 | 0.03802090 |

| circRNA3620 | CAMSAP1 | 2.86 | 1.02 | 1.83 | 0.01997006 |

| circRNA5707 | CREB5 | 1.97 | 0.64 | 1.94 | 0.02020643 |

| circRNA5067 | TMEM62 | 1.24 | 0.32 | 2.26 | 0.01961495 |

| circRNA6242 | SPTBN4 | 1.12 | 0.11 | 3.64 | 0.00281198 |

| circRNA6348 | ARID1A | 1.12 | 0.16 | 3.09 | 0.00281198 |

| circRNA6141 | GSE1 | 1.12 | 0.38 | 1.90 | 0.04803681 |

| circRNA652 | CDC6 | 0.95 | 0.21 | 2.46 | 0.01825840 |

| ciRNA326 | PDLIM2 | 0.79 | 0.05 | 4.04 | 0.00547933 |

| circRNA7191 | PHLPP1 | 0.73 | 0.16 | 2.47 | 0.02220809 |

| circRNA5813 | ISPD | 0.73 | 0.11 | 3.02 | 0.02220809 |

| circRNA1912 | RYK | 0.73 | 0.21 | 2.07 | 0.04933581 |

| circRNA4837 | CASC4 | 0.51 | 0.05 | 3.40 | 0.03997049 |

| circRNA4302 | GFM2 | 0.51 | 0.05 | 3.40 | 0.03997049 |

| ciRNA156 | GRHL1 | 0.51 | 0.05 | 3.40 | 0.03997049 |

Table 2.

Down-regulated circRNAs in LCG and MCG.

| circRNA ID | host gene | LCG (FPKM) | MCG (FPKM) | log2FC | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| circRNA6854 | KCTD9 | 0.79 | 3.17 | -1.66 | 0.03757668 |

| circRNA2245 | HEBP1 | 0.51 | 2.90 | -2.16 | 0.01279541 |

| circRNA4576 | MED17 | 0.39 | 1.82 | -1.85 | 0.03625281 |

| circRNA6019 | AXDND1 | 0.34 | 1.82 | -2.07 | 0.02348295 |

| circRNA3075 | PRPF18 | 0.34 | 1.61 | -1.89 | 0.04479169 |

| circRNA1685 | PHLDB2 | 0.28 | 1.61 | -2.15 | 0.02812314 |

| circRNA3516 | UBXN2A | 0.17 | 1.39 | -2.66 | 0.01551409 |

| circRNA3084 | FAM188A | 0.11 | 1.02 | -2.77 | 0.02972176 |

| circRNA1167 | REV3L | 0.06 | 0.80 | -3.36 | 0.01414588 |

| circRNA177 | BMS1 | 0.06 | 0.80 | −3.36 | 0.01414588 |

| circRNA6691 | PHLDB2 | 0.06 | 0.80 | −3.36 | 0.01414588 |

| circRNA815 | ARL8B | 0.06 | 0.80 | −3.36 | 0.01414588 |

| circRNA5184 | AP3B1 | 0.06 | 0.59 | −2.92 | 0.03997049 |

| circRNA2664 | VPS72 | 0.06 | 0.59 | −2.92 | 0.03997049 |

| circRNA6893 | AGTPBP1 | 0.06 | 0.59 | −2.92 | 0.03997049 |

Figure 3.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) result of circRNAs expression. (a) Divergent primers used in the amplification of circular junctions. (b) Validation of putative circRNAs by qPCR. Blue: LCG; Red: MCG. Error bars indicate mean ± SE for three individuals, “*”p < 0.05, “**”p < 0.01.

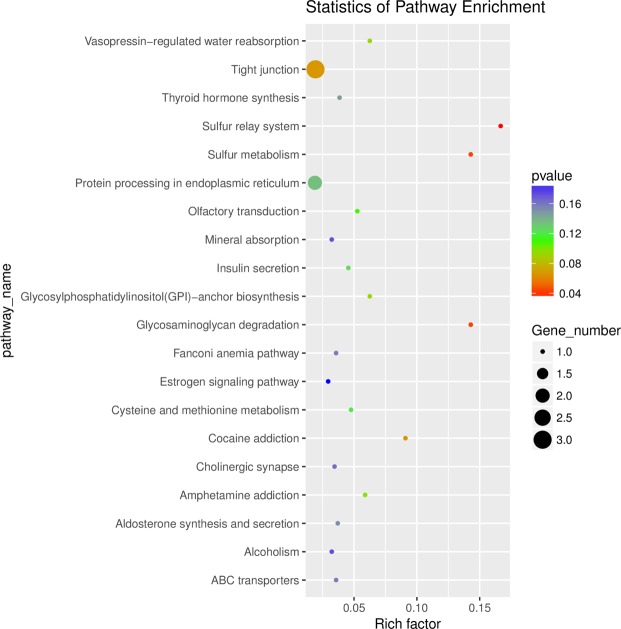

In our data, total 13,320 circRNAs detected in our study were derived from 4826 host genes. 45% of these host genes generated only one circRNA, and 20% of these host genes generated two circRNAs, whereas 8% of these host genes generated more than six circRNAs (Fig. 4a). We screened 10 candidate circRNAs and found these circRNAs consisted of three or four exons on average (Fig. 4b).

Figure 4.

(a) Numbers of circRNAs produced by the same gene. (b) Exon distribution of candidate circRNAs. Different colors represent different exons.

Enrichment analysis of differentially expressed circRNA host genes

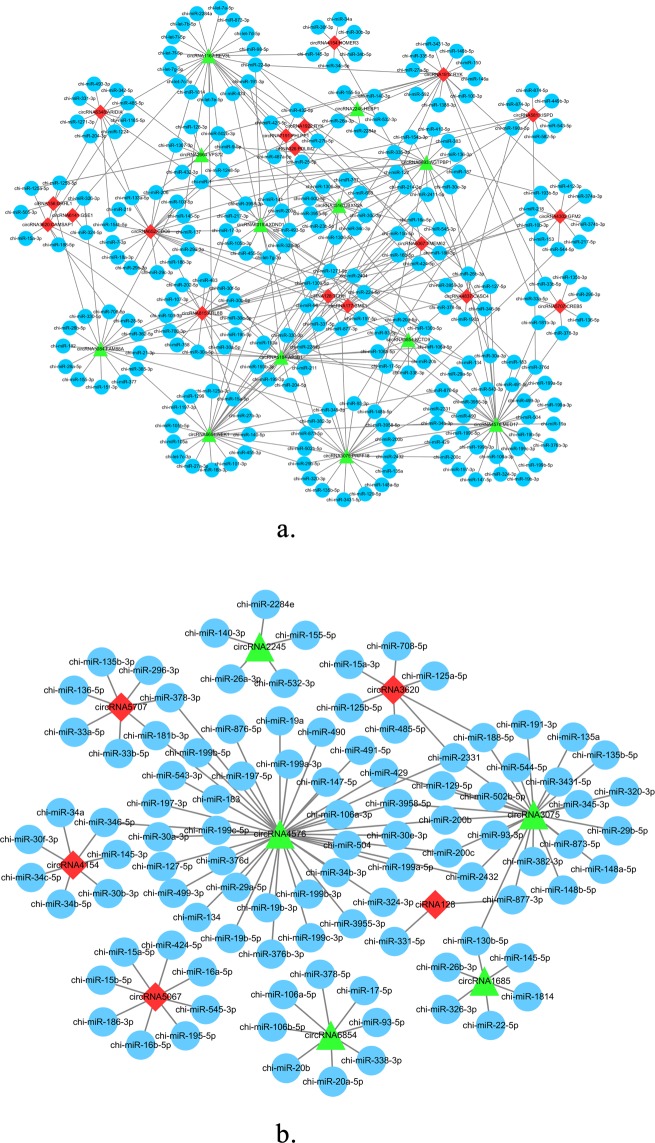

We performed GO and KEGG enrichment analysis for the host genes of differentially expressed circRNAs. A total of 22 host genes were enriched in 106 GO terms, and the top 25, top 15 and top 10 in biological processes, cellular components and molecular functions, respectively (Fig. 5a). In Fig. 5b, the top 20 significant GO terms were exhibited, and it can be seen that keratinization and intermediate filament organization were closely related to cashmere fiber growth. A total of 43 pathways were enriched using KEGG analysis, and the top 20 pathways were shown in Fig. 6. These include the sulfur relay system, sulfur metabolism, and glycosaminoglycan degradation pathways, suggesting that these pathways could also be involved in the regulation of cashmere fineness.

Figure 5.

Gene ontology (GO) analysis of differentially expressed circRNAs. (a) Top 25 biological processes, top 15 cell components, and top 10 molecular functions. (b) The top 20 GO terms. The color of the dot corresponds to different p-value ranges, and the size of the dot indicates the number of genes in the pathway. Rich factor denotes the number of differentially expressed circRNAs in the GO/ the total number of circRNAs in the GO.

Figure 6.

Top 20 Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways of host genes of differentially expressed circRNAs. The color of the dot corresponds to different p-value ranges, and the size of the dot indicates the number of genes in the pathway. Rich factor denotes the number of differentially expressed circRNAs in the KEGG/the total number of circRNAs in the KEGG.

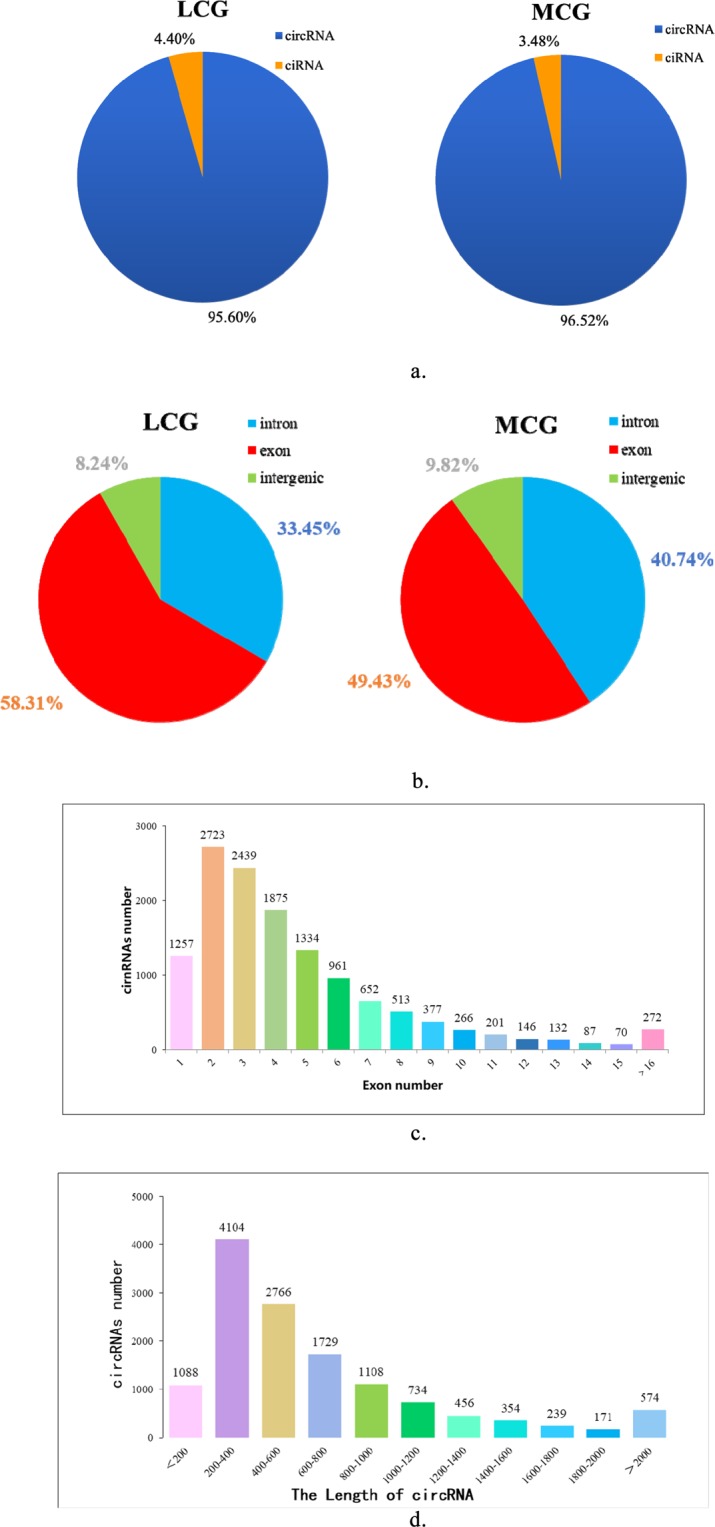

Analysis of interactions between circRNAs and miRNAs

It is generally accepted that circRNA is an adsorbed miRNA sponge and interacts with miRNA. We predicted the potential circRNAs-miRNAs interactions for these differential circRNAs, and the results indicated that the co-expression networks included 32 differentially expressed circRNAs, their host genes and 244 miRNAs (Fig. 7a). The results suggested that circRNA6854 may function as a sponge for these miRNAs, such as chi-miR-106a-5p, chi-miR-106b-5p, chi-miR-17-5p, chi-miR-20a-5p, chi-miR-20b, chi-miR-338-3p, chi-miR-378-5p, and chi-miR-93-5p. CiRNA128 has an interaction with chi-miR-331-5p and chi-miR-877-3p. Moreover, the interactions between 10 identified differentially expressed candidate circRNAs and their target miRNAs are presented in Fig. 7b.

Figure 7.

The circRNAs-miRNAs network. (a) Network of 32 differentially expressed circRNAs. Red and green represent up- and down-regulation, and blue represents target-miRNA. (b) The circRNAs-miRNAs network of 10 candidate circRNAs.

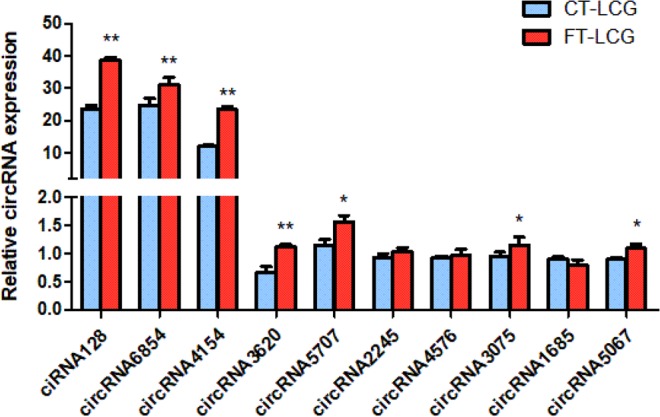

Validation of differentially expressed circRNAs by qPCR

To investigate the expression of circRNAs and determine circRNAs may be vital for regulating cashmere fineness in LCG skin tissue, we used qPCR to confirm the differential expression of certain circRNAs in coarse type and fine type LCG skins. Ten differentially expressed circRNAs were selected and specific qPCR primers were designed within the circRNAs’ junction regions. RNA-seq results showed that ciRNA128 had the highest expression level among the up-regulated circRNAs, while circRNA6854 had the highest expression level among the down-regulated circRNAs. The qPCR experiment results of CT-LCG and FT-LCG were shown in Fig. 8. It was proven that these circRNAs really existed and showed similar expression patterns in LCG skin, with the majority exhibiting a higher expression level in FT-LCG. The results of ciRNA128, circRNA6854, circRNA3620 and circRNA4154 are significantly differential expressed in RNA-seq and qPCR, which suggests that they might play a positive role in cashmere goats with different fiber diameters.

Figure 8.

Quantitative real-time PCR results of circRNAs expression. Blue: CT-LCG; Red: FT-LCG. Error bars represents standard deviations within the group, the “*”indicates the significant difference p < 0.05, “**”indicates p < 0.01.

Discussion

The cashmere goat is a great breed that produces large amounts of high-grade cashmere fiber. As one of the largest producers of cashmere in the world, China has made tremendous contributions to the world animal fiber industry and plays an indispensable role in global cashmere production25. CircRNAs can be classified into four categories: ecRNA, EIciRNA, ciRNA, and tricRNA26. CircRNAs located in the nucleus are mainly involved in transcriptional regulation. During the past few years, through high-throughput RNA sequencing and bioinformatics analysis, a great number of circRNAs have been discovered in different species and tissues. For example, 13,950 circRNAs were detected in pre-ovulatory ovarian follicles of goats, and 37 circRNAs were found to be differentially expressed27. Empirical Bayes sequencing analysis identified 11 down-regulated and 32 up-regulated circRNAs in embryos with black fur skin and white fur skin of mice, and these circRNAs may play a role in skin pigmentation28. The effects of mRNA and lncRNA have been reported on the skin and hair follicles29,30, but there are few studies on the effect of circRNAs on the fineness of cashmere and cashmere growth.

In recent years, numerous studies have found that circRNAs located in cytoplasm can compete with mRNAs for target binding sites of miRNAs to regulate the expression of mRNAs. The interaction between circRNA and miRNA has attracted more and more attention. In fact, a number of non-coding RNAs have been identified and reported in cashmere goat skin31–33. In the current study, we identified a total of 13,320 circRNAs in goat skins using RNA-seq analysis. Among these circRNAs, 32 circRNAs were differentially expressed between LCG and MCG skin, and then we randomly selected 6 circRNAs to verify the expression levels by qRT-PCR. The results of RNA-seq and qPCR were almost identical, thereby indicated the reliability of RNA-seq. Additionally we carried out validation on 10 circRNAs in CT- LCG and FT- LCG, interestingly, these circRNAs also had a high expression level in FT-LCG, which may play potential positive role in regulating fiber fineness formation.

We obtained 106 terms from GO enrichment analysis, including 69 biological processes, 17 molecular functions, and 20 cellular components. Keratinization, intermediate filament organization, spindle midzone, Wnt-protein binding, and Wnt-activated receptor activity negative regulation of stress fiber assembly were significant enriched, these pathways may participate in the regulation of cashmere fineness formation. Although there were only three pathways in which the sulfur relay system, sulfur metabolism, and glycosaminoglycan degradation were found to be significantly enriched, the host genes of circRNA6854 and circRNA815 were involved in all pathways. Studies have shown that intermediate filaments are probably the key factors involved in cashmere growth34. In addition, several important pathways that play a role in dominating hair follicle development were reported, such as the PPAR pathway35, Wnt signaling pathway5,36,37, MAPK signaling pathway38, and NF-kappa B signaling pathway39. Our data also enriched these pathways, it further illustrates the importance of these circRNAs in goat skin.

Previous studies have shown that circRNA can further influence the expression of target miRNA by acting as a miRNA sponge40–42, and the interactions between circRNA and miRNA have been investigated16,43. It is noteworthy that some known miRNAs have been reported to be closely related to cashmere growth and development, while some miRNAs may play multiple roles in cashmere goat skin in the growth period. The expressions of mir-103-3p, miR-15b-5p, miR-17-5p, mir-30c-5p, mir-200b, mir-199a-3p, mir-199a-5p, mir-30a-5p, and mir-29a-3p were significantly different between anagen and telogen skin in Liaoning Cashmere goats44, and these were found as the target miRNAs of circRNAs in our data. We hypothesized that a lot of circRNAs interact with many cashmere-related miRNAs (chi-miR-106a-5p, chi-miR-106b-5p, chi-miR-17-5p, let-7b-5p, chi-miR-20b, chi-miR-143). Previous research proved that oar-miR-103-3P, oar-miR-148b-3P, oar-miR-320-3P, oar-miR-31-5P, oar-novel-1-5P, and oar-novel-2-3P may play an important role in follicle growth of Tibetan Sheep45. Mir-200b as a target was involved in the regulation of hair follicle development46, while miR-1839, miR-374b, and miR-2284n have been reported as showing the highest relative expression levels at the anagen in Inner Mongolia cashmere goat skin tissue33. It was reported that let-7b-5p, mir-10a-5p, and mir-21-5p exhibited differences at various hair cycle stages in mouse skin47. Research showed that the gene families let-7, mir-17, mir-30, mir-15, and mir-8 were highly expressed in goat skin31. In Hu sheep lambskin hair follicles, 14 miRNAs including miR-143, miR-10a, and let-7 were screened as important candidate miRNAs48. MiR-143, miR-203, and let-7, let-7b, let-7b-5p, let-7f, and let-7c were found to be expressed in Liaoning Cashmere Goats and Fine-Wool Sheep skin49, and the let-7 family was reported to be involved in the regulation of cell differentiation50. It suggests that let-7b-5p may affect cashmere development as the target of circRNA1167. MiR-378, miR-378e, and miR-378d were only detected in Liaoning Cashmere Goats and promoted angiogenesis50,51. Five novel miRNAs (chi-miR-2284n, chi-miR-421*, chi-miR-421, chi-miR-1839, and chi-miR-374) play roles in the production of cashmere in Inner Mongolia cashmere goat skin33. Taken together, it can be inferred that ciRNA128-chi-miR-331-5p and circRNA6854-chi-miR-17-5p may have certain roles in cashmere fineness and cashmere fiber morphogenesis.

The expression of circRNAs has been appropriately correlated with an abundance of host genes in different animal tissues52–55, such as oar_circ_0003451 and TTN, and oar_circ_0005250 and MYH7 may play important roles in muscle development and growth22; circRNA8077 and CRIM1, as well as circRNA3314 and TMEM159 play vital roles in the development of the receptive endometrium56. The host genes of circRNAs are involved in regulating hair traits, and these circRNAs may be considered as a possible factor regulating cashmere fineness. The host gene TCHH of ciRNA128 has been confirmed to be involved in hair formation57. Studies based on GWAs found TCHH in Latin Americans of mixed European and Native American origin58. Among Europeans, the strongest link between straight hair and TCHH was found59, and DSC2, DSG3, CALML5, TCHH are related to hair growth using iTRAQ-labeling in sheep and goats60. KCTD9 has been reported to be associated with cancer61, promoting cell growth and inhibiting cell activation62,63. Thus, it proved potential reference value for cashmere fiber fineness and the expression analysis of circRNAs in LCG.

In conclusion, we performed RNA-seq analysis that identified 13,320 circRNAs in cashmere goat skins, of which 32 circRNAs were found to be differential expression. The result of qRT-PCR confirmed that four circRNAs (ciRNA128, circRNA6854, circRNA4154 and circRNA3620) were differentially expressed in CT-LCG and FT-LCG. Host genes of differentially expressed circRNAs were mainly enriched in keratinization and intermediate filament organization. An integrated regulatory network of circRNAs and miRNAs was executed in anagen cashmere goat skin. This study may contribute to better understanding of circRNAs in goat skin.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

All experiments in this study were approved and conducted according to the Animal Experimental Committee of Shenyang Agricultural University, Shenyang, China (201606005).

Sample preparation

Skin samples from three adult female Liaoning cashmere goats (d = 19.4 µm, 19.5 µm and 19.8 µm) and three adult female Inner Mongolia cashmere goats (d = 13.8 µm, 14.0 µm and 14.1 µm) were carefully collected. The animals we collected were based on all the same conditions, including sex, age, feeding and physiological status and other factors. To reduce pain to experimental animals, we used local anesthesia with procaine. In the upper one-third of the right scapula along the mid-dorsal and mid-abdominal lines, about 1 cm2 lateral skin from the six cashmere goats were taken and disinfected with 75% ethanol. And then, the skin samples were washed three times with PBS and immediately stored in liquid nitrogen until RNA isolation. In addition, three coarse type (CT) skin (d = 19.5 µm, 19.7 µm and 20.2 µm) and three fine type (FT) skin (d = 15.3 µm, 15.4 µm and 15.6 µm) samples from Liaoning cashmere goats were obtained with the same method for qRT-PCR analysis.

Total RNA isolation, library construction and sequencing

The total RNA amount and purity of each sample was quantified by Nano Drop ND-1000 (Nano Drop, Wilmington, DE, USA). Approximately 5 ug of total RNA was used to deplete ribosomal RNA according to the manufacturer’s instructions for the Ribo-Zero rRNA Removal Kit (Illumina, San Diego, USA). In order to construct the cDNA library of circRNAs, we used Rnase R to remove linear RNA. The average insert size for the final cDNA library was 300 bp (±50 bp), the library was purified and qualified by Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system.

Identification of circRNAs and analysis of differentially expressed circRNAs

The cDNA libraries were performed the paired-end sequencing on an Illumina Hiseq. 4000 (LC Bio, China) following the vendor’s recommended protocol. Firstly, low-quality reads and adapters were removed by Cutadapt v1.10, quality controlled by FastQC v0.10.1, and then obtained the high-quality clean reads. TopHat v2.0.4 was utilized to map the clean reads to the reference genome from National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/?term = Capra + hircus)64,65. Also, StringTie v1.3.0 was used to assemble and quantify expressed genes and transcripts (https://ccb.jhu.edu/software/stringtie/index.shtml)66. CIRCExplorer2 v2.2.6 software and the following criteria were used to identify candidate circRNAs: mismatch ≤2, back-spliced junction reads ≥1, and distances of two splice sites of less than 100 kb in the genome67. Then, the back-spliced reads with at least two supporting reads were annotated as circRNAs. The differential expression of circRNAs between the two groups was assessed using the Ballgown package. A p-value < 0.05 and |log2 (fc)| > 1 were set as the threshold for differential expression68,69.

Gene ontology (GO) analysis and KEGG analysis of host genes

GO analysis (http://www.geneontology.org) was applied to differentially expressed circRNA-hosting genes. Similarly, pathway analysis uncovered the significant pathways related to differentially expressed circRNAs according to the annotation of the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) (http://www.kegg.jp/kegg)70. A threshold of p < 0.05 was used as a criterion for the determination of whether the enrichment analysis was significant71.

Network construction of the circRNAs-miRNAs interaction

The interaction of circRNAs-miRNAs was predicted with miRNA target prediction software miRanda (http://www.microrna.org/microrna/home.do) and TargetScan (http://www.targetscan.org/)72, where the max free energy values of miRanda is <−10 and the score percentiles of TargetScan is ≥50. The differential expression circRNAs-miRNAs interaction and the network of circRNAs along with their target miRNAs were performed using cytoscape v3.5.1 software (https://cytoscape.org/, USA)73.

Quantitative real-time PCR validation

We randomly detected 6 differentially expressed circRNAs for qRT-PCR. To prove the resistance of circRNAs to RNase R digestion, we treated total RNAs with RNase R before cDNA synthesis. In order to validate the differentially expressed circRNAs, total RNAs were synthesized directly to cDNA synthesis by an RT-PCR kit. According to the manufacturer’s instructions, Real-time PCR was performed using SYBR Green (TaKaRa Biotech, Dalian). The glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) gene was used as an internal control to normalize the expression level of circRNAs74. Three independent experiments were carried out on LCG and MCG skin samples. Six pair primers were designed by primer 5 software (www.premierbiosoft.com) and listed in Supplemental Table S1, and all primers were spanning the distal ends of circRNAs. The relative expression levels of different circRNAs were analyzed by the 2−ΔΔCt method in qPCR data75. The data were indicated as the means ± SE (n = 3). All statistical analyses in the two groups were calculated using a t-test in SPSS statistical software (Version 22.0, Chicago, IL, USA), the difference was significant at p < 0.05. In addition, three CT-LCG and FT-LCG skin samples were verified by qPCR under the same experimental conditions to find the differential circRNAs in LCG.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The work was supported financially by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31802038, 31872325, 31672388), Natural Science Foundation of Liaoning Province, China (No. 2015020758), Key Project Foundation of Education Department of Liaoning Province, China (No. LSNZD201606), Breeding project of new Liaoning cashmere goat “meat and meat dual-use” (No. 2017202005), Science and Technology Innovation Talent Support Foundation for Young and Middle-aged People of Shenyang City, China (RC170447).

Author contributions

Data curation, Yuanyuan Zheng; Formal analysis, Yuanyuan Zheng and Chang Yue; Funding acquisition, Zeying Wang and Wenlin Bai; Methodology, Suping Guo, Zeying Wang and Wenlin Bai; Project administration, Wenlin Bai; Resources, Dan Guo and Suling Guo; Software, Yuanyuan Zheng and Taiyu Hui; Supervision, Zeying Wang; Validation, Yuanyuan Zheng and Jiaming Sun; Writing-original draft, Yuanyuan Zheng; Writing-review & editing, Yuanyuan Zheng, Bojiang Li, Zeying Wang and Wenlin Bai.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Zeying Wang, Email: wangzeying2012@syau.edu.cn.

Wenlin Bai, Email: baiwenlin@syau.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-57404-9.

References

- 1.Hu PF, et al. Study on characteristics of in vitro culture and intracellular transduction of exogenous proteins in fibroblast cell line of Liaoning cashmere goat. Molecular Biology Reports. 2013;40:327–336. doi: 10.1007/s11033-012-2064-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang WG, Wu JH, Li JQ, Midori Y. A Subset of Skin-Expressed microRNAs with Possible Roles in Goat and Sheep Hair Growth Based on Expression Profiling of Mammalian microRNAs. OMICS: A. Journal of Integrative Biology. 2007;11:385–396. doi: 10.1089/omi.2006.0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jin M, et al. Construction of a cDNA library and identification of genes from Liaoning cashmere goat. Livest Sci. 2014;164:26–34. doi: 10.1016/j.livsci.2014.02.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu H, et al. Characterization of Liaoning cashmere goat transcriptome: sequencing, de novo assembly, functional annotation and comparative analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e77062. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stenn KS, Paus R. Controls of hair follicle cycling. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:449–494. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.1.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leirós GJ, Attorresi AI, Balañá ME. Hair follicle stem cell differentiation is inhibited through cross-talk between Wnt/β-catenin and androgen signalling in dermal papilla cells from patients with androgenetic alopecia. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:1035–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.10856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Samuelov L, et al. P-cadherin regulates human hair growth and cycling via canonical Wnt signaling and transforming growth factor-β2. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:2332–1241. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jahoda CA, Christiano AM. Niche crosstalk: intercellular signals at the hair follicle. Cell. 2011;146:678–681. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee J, Tumbar T. Hairy tale of signaling in hair follicle development and cycling. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2012;23:906–916. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsai SY, et al. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in dermal condensates is required for hair follicle formation. Dev Biol. 2014;385:179–188. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tripurani SK, et al. Suppression of Wnt/β-catenin signaling by EGF receptor is required for hair follicle development. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2018;29:2784–2799. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E18-08-0488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mukhopadhyay A, et al. Negative regulation of Shh levels by Kras and Fgfr2 during hair follicle development. Dev Biol. 2013;373:373–382. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rishikaysh P, et al. Signaling involved in hair follicle morphogenesis and development. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:1647–1670. doi: 10.3390/ijms15011647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liang D, Wilusz JE. Short intronic repeat sequences facilitate circular RNA production. Genes Dev. 2014;28:2233–2247. doi: 10.1101/gad.251926.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salzman J, Gawad C, Wang PL, Lacayo N, Brown PO. Circular RNAs are the predominant transcript isoform from hundreds of human genes in diverse cell types. Plos One. 2012;7:e30733. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jeck WR, Sharpless NE. Detecting and characterizing circular RNAs. Nature Biotechnology. 2014;32:453–461. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jeck WR, et al. Circular RNAs are abundant, conserved, and associated with ALU repeats. Rna-a Publication of the Rna Society. 2013;19:141–157. doi: 10.1261/rna.035667.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang HD, Jiang LH, Sun DW, Hou JC, Ji ZL. CircRNA: a novel type of biomarker for cancer. Breast Cancer. 2018;25:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s12282-017-0793-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang R, et al. The circRNA circAGFG1 acts as a sponge of miR-195-5p to promote triple-negative breast cancer progression through regulating CCNE1 expression. Molecular Cancer. 2019;18:4. doi: 10.1186/s12943-018-0933-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 20.Li P, et al. Using circular RNA as a novel type of biomarker in the screening of gastric cancer. Clin Chim Acta. 2015;444:132–136. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2015.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li GY, et al. Genome-wide analysis of circular RNAs in prenatal and postnatal muscle of sheep. Sci Rep. 2017;8:97165–97177. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.21835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li GY, et al. Genome-wide analysis of circular RNAs in prenatal and postnatal pituitary glands of sheep. Scientific Reports. 2017;7:16143. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-16344-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zheng QP, et al. Circular RNA profiling reveals an abundant circHIPK3 that regulates cell growth by sponging multiple miRNAs. Nature communications. 2016;7:11215. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pang F, et al. Genome-wide analysis of circular RNAs in goat skin fibroblast cells in response to Orf virus infection. PeerJ. 2019;7:e6267. doi: 10.7717/peerj.6267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Su R, et al. Comparative genomic approach reveals novel conserved microRNAs in Inner Mongolia cashmere goat skin and longissimus dorsi. Mol Biol Rep. 2015;42:989–995. doi: 10.1007/s11033-014-3835-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang XO, et al. Complementary Sequence-Mediated Exon Circularization. Cell. 2014;159:134–147. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tao H, et al. Circular RNA profiling reveals chi_circ_0008219 function as microRNA sponges in pre-ovulatory ovarian follicles of goats (Capra hircus) Genomics. 2017;110:257–266. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2017.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhu Z, et al. Comprehensive circRNA expression profile and construction of circRNA‐associated ceRNA network in fur skin. Experimental Dermatology. 2018;27:3. doi: 10.1111/exd.13502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zheng YY, et al. An Integrated Analysis of Cashmere Fineness lncRNAs in Cashmere Goats. Genes. 2019;10:4. doi: 10.3390/genes10040266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sen M, et al. Synchronous profiling and analysis of mRNAs and ncRNAs in the dermal papilla cells from cashmere goats. BMC Genomics. 2019;20:512. doi: 10.1186/s12864-019-5861-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schmitt MJ, et al. Interferon-g-induced activation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1) up-regulates the tumor suppressing microRNA-29 family in melanoma cells. Cell Commun Signal. 2012;10:41. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-10-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu Z, et al. Identification of conserved and novel microRNAs in cashmere goat skin by deep sequencing. Plos One. 2012;7:e50001. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yuan C, et al. Discovery of cashmere goat (Capra hircus) microRNAs in skin and hair follicles by Solexa sequencing. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:511. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou GX, et al. Integrative analysis reveals ncRNA-mediated molecular regulatory network driving secondary hair follicle regression in cashmere goats. BMC Genomics. 2018;19:222. doi: 10.1186/s12864-018-4603-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yue YJ, et al. Integrated Analysis of the Roles of Long Noncoding RNA and Coding RNA Expression in Sheep (Ovis aries) Skin during Initiation of Secondary Hair Follicle. Plos One. 2016;11:e0156890. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bai WL, et al. LncRNAs in Secondary Hair Follicle of Cashmere Goat: Identification, Expression, and Their Regulatory Network in Wnt Signaling Pathway. Animal Biotechnology. 2016;29:1. doi: 10.1080/10495398.2017.1356731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Andl T, Reddy ST, Gaddapara T, Millar SE. WNT signals are required for the initiation of hair follicle development. Dev Cell. 2002;2:643–653. doi: 10.1016/S1534-5807(02)00167-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dickinson SE, et al. p38 MAP kinase plays a functional role in UVB-induced mouse skin carcinogenesis. Mol Carcinog. 2011;50:469–478. doi: 10.1002/mc.20734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jin M, et al. Long noncoding RNA and gene expression analysis of melatonin-exposed Liaoning cashmere goat fibroblasts indicating cashmere growth. Naturwissenschaften (The Science of Nature). 2018;105:9–10. doi: 10.1007/s00114-017-1537-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang K, et al. A circular RNA protects the heart from pathological hypertrophy and heart failure by targeting miR-223. European Heart Journal. 2016;37:2602–2611. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hansen TB, et al. Natural RNA circles function as efficient microRNA sponges. Nature. 2013;495:384–388. doi: 10.1038/nature11993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li F, et al. Circular RNA ITCH has inhibitory effect on ESCC by suppressing the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Oncotarget. 2015;6:8. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang W, et al. Foxo3 activity promoted by non-coding effects of circular RNA and Foxo3 pseudogene in the inhibition of tumor growth and angiogenesis. Oncogene. 2015;35:3919. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bai WL, et al. Differential Expression of microRNAs and their Regulatory Networks in Skin Tissue of Liaoning Cashmere Goat during Hair Follicle Cycles. Animal Biotechnology. 2016;27:104–112. doi: 10.1080/10495398.2015.1105240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu GB, et al. Identification of microRNAs in Wool Follicles during Anagen, Catagen, and Telogen Phases in Tibetan Sheep. Plos One. 2013;8:e77801. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Andl T, et al. The miRNA-processing enzyme dicer is essential for the morphogenesis and maintenance of hair follicles. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1041–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mardaryev AN, et al. Micro-RNA-31 controls hair cycle-associated changes in gene expression programs of the skin and hair follicle. FASEB J. 2010;24:3869–3881. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-160663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gao W, et al. Screening candidate microRNAs (miRNAs) in different lambskin hair follicles in Hu sheep. Plos One. 2017;12:e0176532. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li JP, et al. Transcriptome-Wide Comparative Analysis of microRNA Profiles in the Telogen Skins of Liaoning Cashmere Goats (Capra hircus) and Fine-Wool Sheep (Ovis aries) by Solexa Deep Sequencing. DNA and Cell Biology. 2016;35:696–705. doi: 10.1089/dna.2015.3161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Deppe J, et al. Upregulation of miR-203 and miR-210 affect growth and differentiation of keratinocytes after exposure to sulfur mustard in normoxia and hypoxia. Toxicol Lett. 2016;244:81–87. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2015.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Joyce CE, et al. Deep sequencing of small RNAs from human skin reveals major alterations in the psoriasis miRNAome. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:4025–4040. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Venø MT, et al. Spatio-temporal regulation of circular RNA expression during porcine embryonic brain development. Genome Biol. 2015;16:245. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0801-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Salzman J, Chen RE, Olsen MN, Wang PL, Brown PO. Cell-type specific features of circular RNA expression. Plos Genet. 2013;9:e1003777. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Siede D, et al. Identification of circular RNAs with host gene-independent expression in human model systems for cardiac differentiation and disease. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 2017;109:48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2017.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rybak-Wolf A, et al. Circular RNAs in the mammalian brain are highly abundant, conserved, and dynamically expressed. Mol Cell. 2015;58:870–885. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Song YX, et al. Analyses of circRNA profiling during the development from pre-receptive to receptive phases in the goat endometrium. J Anim Sci Biotechnol. 2019;10:34. doi: 10.1186/s40104-019-0339-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu F, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies identifies 8 novel loci involved in shape variation of human head hair. Human Molecular Genetics. 2017;27:559–575. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddx416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Adhikari K, et al. A genome-wide association scan in admixed Latin Americans identifies loci influencing facial and scalp hair features. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10815. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Medland SE, et al. Common variants in the trichohyalin gene are associated with straight hair in Europeans. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;85:750–755. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Li Y, et al. Comparative proteomic analyses using iTRAQ-labeling provides insights into fiber diversity in sheep and goats. Journal of Proteomics. 2017;172:82–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2017.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhou YY, et al. Increased expression of KCTD9, a novel potassium channel related gene, correlates with disease severity in patients with viral hepatitis B. Chinese journal of hepatology. 2008;16:835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen T, et al. KCTD9 contributes to liver injury through NK cell activation during hepatitis B virus-induced acute-on-chronic liver failure. Clinical Immunology. 2013;146:207–216. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2012.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang X, et al. Interference with KCTD9 inhibits NK cell activation and ameliorates fulminant liver failure in mice. BMC Immunology. 2018;19:20. doi: 10.1186/s12865-018-0256-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dong Y, et al. Sequencing and automated whole-genome optical mapping of the genome of a domestic goat (Capra hircus) Nature Biotechnology. 2012;31:135–141. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Trapnell C, et al. Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nature Protocols. 2012;7:562–578. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pertea M, Kim D, Pertea GM, Leek JT, Salzberg SL. Transcript-level expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with HISAT, StringTie and Ballgown. Nature Protocols. 2016;11:1650–1667. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2016.095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang XO, et al. Diverse alternative back-splicing and alternative splicing landscape of circular RNAs. Genome Res. 2016;26:1277–1287. doi: 10.1101/gr.202895.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Robinson MD, Mccarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2014;26:139–140. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Frazee AC, et al. Ballgown bridges the gap between transcriptome assembly and expression analysis. Nature Biotechnology. 2015;33:243–246. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Xie C, et al. Kobas 2.0: a web server for annotation and identification of enriched pathways and diseases. Nucleic Acids Research. 2011;39:W316–W322. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kanehisa M, Furumichi M, Tanabe M, Sato Y, Morishima K. KEGG: new perspectives on genomes, pathways, diseases and drugs. Nucleic Acids Research. 2017;45:D353–D361. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Agarwal V, Subtelny AO, Thiru P, Ulitsky I, Bartel DP. Predicting microRNA targeting efficacy in Drosophila. Genome Biol. 2018;19:152. doi: 10.1186/s13059-018-1504-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Saito R, et al. Atravel guide to Cytoscape plugins. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:1069–1076. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Li J, Li Q, Chen L, Gao Y, Li J. Expression profile of circular RNAs in infantile hemangioma detected by RNA-Seq. Medicine. 2018;97:e10882. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000010882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2− ΔΔCT Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.