Abstract

Trauma hemorrhagic shock is a common and critical disease, which induces multiple organ failure, especially of the liver, when combined with fracture. However, no effective trauma hemorrhagic liver injury model that mimics the real-life condition has been developed so far. This study aims to develop an effective trauma hemorrhagic liver injury model based on a fracture and hemorrhage approach. The levels of the following proteins were determined by the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) in our fracture and hemorrhage-based model system: serum alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1β, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor-α, chemokines such as C-C motif ligand 2, C-C motif ligand 5, C-C motif ligand 13, and C-X-C motif ligand 2. Pathological changes in the liver and the numbers of CD45+ cells and polymorphic nuclear neutrophils (PMNs) in the liver parenchyma were analyzed by hematoxylin-eosin staining, periodic acid-Schiff staining, and flow cytometry, respectively. As expected, the serum levels of ALT and AST increased significantly with trauma time and peaked at 16 hrs post-trauma. Similarly, the levels of the inflammatory cytokines also increased significantly with trauma time, and peaked after 8 hrs or 16 hrs of trauma. Analysis of hepatic morphology at the time-point when the trauma was inflicted and at later time-points post-trauma, revealed invasion of inflammatory cells, formation of hyperchromatic nuclei, and presence of loose and irregular acinus and vacuolus; the phenotype was most severe at 16 hrs post-trauma. The number of CD45+ cells and PMNs increased significantly with trauma time and peaked after 16 hrs of trauma. These observations indicated that the trauma hemorrhagic liver injury model was successfully established and that it could provide an effective system to study the mechanisms of trauma hemorrhagic liver injury.

Keywords: Trauma hemorrhagic shock, liver injury, model, inflammatory cytokine, CD45+, PMNs

Introduction

Trauma hemorrhagic shock (THS) is one of the most common and critical illnesses that is characterized by multiple organ failure (MOF) [1-3]. It is a shock complication caused by severe trauma and is accompanied by acute circulatory insufficiency, hypovolemia, hypoxemia, low-flow tissue perfusion, organ injuries, microcirculatory disturbances, and cellular hypoxia [4-6]. Traumatic hemorrhage causes oxygen deficiency that may perturb the microcirculation of the body and induce hypoxia in case of excessive bleeding, which may further lead to metabolic acidosis, coagulation dysfunction, and hypothermia [7-10]. In the absence of immediate medical intervention, the course of the illness could rapidly worsen and cause fatalities [11,12]. In the early stages of THS, the generation of certain cytokines triggers inflammatory reactions, which promotes wound healing; however, excessive amounts of cytokines may enhance local reaction and aggravate the cascade effect of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and precipitate the multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS), such as in the case of liver injury [13-16].

Trauma hemorrhage-induced liver injury is a severe illness that is characterized by immune cell aggregation and invasion, such as polymorphic nuclear neutrophils (PMNs), mononuclear cells, and dendritic cells [17,18], as well as by the production of several inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and chemokines such as C-C motif ligand 2 (CCL2), C-C motif ligand 5 (CCL5), C-C motif ligand 13 (CCL13), and C-X-C motif ligand 2 (CXCL2) [19-22]. If excess PMNs are not eliminated via apoptosis, numerous reactive oxygen species and free radicals are released that aggravate the inflammatory reaction, and finally lead to SIRS, MODS, and even MOF; however, the mechanism of this pathway is still unknown [23-25]. Based on this hypothesis, several animal models of THS were established; however, the fracture-based trauma hemorrhagic liver injury model has not yet been reported [26,27]. In the clinic, trauma hemorrhage is often combined with fracture, and the immunoreaction accompanying the fracture has similarity to that of hemorrhage. Therefore, the fracture injury model has been widely used for studying immunoreactions in trauma hemorrhagic animals [28]. As expected, levels of inflammatory cytokines and the numbers of CD45+ cells and PMNs increased significantly, which indicated that the trauma hemorrhagic liver injury model was successfully established and could be used for simulating liver injury. This model exhibits a significant application value for studying the mechanisms of liver injury.

Materials and methods

Animals

A total of 64 Wistar (male, 260-300 g) rats were purchased and raised in the Chinese PLA General Hospital Animal Center at the house temperature of 25 ± 2°C, humidity of 40-60%, and a 12 hrs light/dark cycle. The animals were randomly divided into 8 groups of 8 rats each, and animals in each group were inflicted with trauma for 0 hrs, 1 hrs, 2 hrs, 4 hrs, 8 hrs, 16 hrs, 24 hrs, and 48 hrs. All the animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Chinese PLA General Hospital and conformed to the current guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 85-23, revised 1996).

Establishment of rat traumatic hemorrhagic liver injury model

An acute mechanical injury method was used to establish the rat traumatic hemorrhagic liver injury model. Briefly, after one week of adaptive feeding, the rats were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital (80 mg/kg) and thereafter, the animals were fixed. Subsequently, a number 22 arteriovenous indwelling needle was used to perform catheterization of the cervical artery and vein and heparin sodium (25 U/mL) was administered for anticoagulation. Blood pressure was monitored by a two channel physiological recorder (type LMS2B) till a stable blood pressure of 80 mm-100 mmHg was observed for at least 10 min, after which the left leg was fixed on the chassis of a man-made bracket and 300 g iron was allowed to fall freely from a height of 25 cm to cause a comminuted fracture in the middle of the femur. During the 30 min of artery intubation and rapid bleeding, blood pressure was monitored; when the blood pressure dropped to 40-50 mmHg and was maintained at that value for 1 h, two times the volume of liquids was rapidly reinfused at a speed of 20 ml/hrs, including autologous anti-coagulated blood and ringer. Thereafter, the skin was sutured back after disinfection, and the animals were subjected to regulated feeding. Subsequently, the rats were killed by dislocation and the whole blood and liver were collected for further analysis.

Measurement of alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels in rat serum

The rat whole blood was incubated for 30 min at room temperature and centrifuged at 4°C, 4,000 rpm for 10 min to collect the serum sample. Subsequently, the levels of serum ALT and AST were detected by the rat serum enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (ALT ELISA kit, ZKP-160515011, ZEKEBIO, Jiangsu, China) and the rat serum AST ELISA kit (ZKP-160516034, ZEKEBIO, Jiangsu, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Data was recorded at 450 nm using a microplate reader during 15 min and analyzed by the SPSS software (version 21.0, http://spss.en.softonic.com/; Chicago, IL, USA). Histogram analysis was done by the Origin 9.5 software (http://www.originlab.com/).

Measurement of levels of inflammatory factors in rat liver

A total of 50 μg of the collected liver tissue was rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen, homogenized in a tissue grinder, and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm at 4°C for 15 min. The supernatant was collected and the amounts of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, CCL2, CCL5, CCL13, and CXCL2 were detected by rat IL-1β ELISA kit (ZKP-1604001, ZEKEBIO, Jiangsu, China), rat IL-6 ELISA kit (ZKP-1604001, ZEKEBIO, Jiangsu, China), rat TNF-α ELISA kit (ZKP-1604001, ZEKEBIO, Jiangsu, China), rat CCL2 ELISA kit (ZKP-1604003, ZEKEBIO, Jiangsu, China), rat CCL5 ELISA kit (ZKP-1604003, ZEKEBIO, Jiangsu, China), rat CCL13 ELISA kit (ZKP-1604003, ZEKEBIO, Jiangsu, China), and rat CXCL2 ELISA kit (ZKP-1604005, ZEKEBIO, Jiangsu, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Data was recorded at 450 nm using a microplate reader during 15 min, and analyzed by the SPSS software (version 21.0, http://spss.en.softonic.com/; Chicago, IL, USA). Histogram analysis was performed using the Origin 9.5 software (http://www.originlab.com/).

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining

The liver was fixed and sliced to perform H&E staining as described below. The slides were slightly over-stained with hematoxylin for approximately 3 to 5 min and the excess stain was removed with tap water. The slides were differentiated and destained for few seconds in acidic alcohol until they appeared red, after which they were briefly rinsed with tap water to remove the acid. Bicarbonate was applied for approximately 2 min, until the nuclei were visibly distinct in blue color. The hematoxylin-stained slides were rinsed with tap water for 3 min, then placed in 70% ethanol and finally in eosin for 2 min. Thereafter, the slides were washed thrice with hesin of 95% ethanol for 5 min and transferred to the first absolute ethanol wash of the clearing series. After staining, images were captured using a microscope connected to a CCD camera.

Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining

The liver was fixed and sliced to perform PAS staining as follows. The tissue samples on the slide were oxidized with periodic acid for approximately 15 min, excess stain was removed with tap water, and the samples were stained with Schiff reagent for 15 min. Thereafter, the slides were washed thrice with sulfinic acid, followed by three washes with distilled water, and restained with hematoxylin. After staining, images were captured using a microscope connected to a CCD camera.

Quantitation of CD45+ cell and PMN numbers in liver parenchymal cells by flow cytometry

The liver tissue (100 mg) was digested with trypsin and screened through a 200-mu cell sieve. The liver parenchymal cells were separated by density gradient centrifugation using Percoll reagent, and diluted to 2 × 106 cells/mL. 1 mL cells were aspirated and centrifuged at 2,000 rpm for 5 min followed by three washes with cold phosphate buffer saline (PBS). The cell pellet was resuspended in 200 μL PBS and labeled with anti-CD45-FITC antibody (for estimating the number of CD45+ cells) and anti-CD11b-FITC and anti-Gr-1-PE antibodies (to identify PMNs in the liver parenchymal cells) at 4°C for 30 min according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Labeled cells were centrifuged at 2,000 rpm for 5 min and were carefully resuspended in 200 μL PBS for detection by flow cytometry.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA using the SPSS software (version 21.0, http://spss.en.softonic.com/; Chicago, IL, USA), and Student’s t-tests were performed in a group of two samples. P < 0.05 and P < 0.01 were considered to indicate significant differences and highly significant differences, respectively.

Results

Serum ALT and AST levels were significantly increased by trauma, with a peak at 16 hrs post-trauma

On comparison with the levels at 0 hrs of trauma, the serum ALT levels increased with trauma time, with a peak at 16 hrs post-trauma, and a slight decrease after 48 hrs of trauma (*: P < 0.05; **: P < 0.01) (Table 1). Similarly, the serum AST level also increased with trauma time, peaked at 16 hrs post-trauma, and decreased slightly after 48 hrs of trauma (*: P < 0.05; **: P < 0.01).

Table 1.

Changes in serum levels of ALT and AST at different time-points of trauma

| Groups | ALT (U/L) | AST (U/L) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 hrs | 25.40 ± 3.40 | 45.80 ± 3.80 |

| 1 hrs | 27.00 ± 4.90* | 50.80 ± 8.70* |

| 2 hrs | 49.00 ± 18.60** | 73.60 ± 17.40** |

| 4 hrs | 430.00 ± 100.80** | 524.00 ± 121.80** |

| 8 hrs | 3439.00 ± 308.50** | 3620.00 ± 614.50** |

| 16 hrs | 6048.00 ± 346.40** | 6344.00 ± 582.00** |

| 24 hrs | 4942.00 ± 255.10** | 5051.00 ± 451.60** |

| 48 hrs | 3814.00 ± 448.10** | 4061.00 ± 587.70** |

P < 0.05;

P < 0.01.

Levels of liver inflammatory cytokines increased significantly after trauma, with a peak at 16 hrs post-trauma

On comparison with the levels at 0 hrs of trauma, the serum level of IL-1β increased significantly with trauma time, reached a peak at 8 hrs post-trauma, and decreased slightly decreased after 48 hrs of trauma (*: P < 0.05, **: P < 0.01) (Table 2). Similarly, on comparison with the levels at 0 hr of trauma, the serum levels of IL-6, TNF-α, CCL2, CCL5, CCL13, and CXCL2 increased significantly with trauma time, with peaks at 8 hrs or 16 hrs post-trauma, and decreased slightly after 48 hrs of trauma (*: P < 0.05, **: P < 0.01).

Table 2.

Assay levels of inflammatory cytokines in liver

| Parameters | Inflammatory cytokines (Mean ± SD, pg/ml) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| IL-1β | IL-6 | TNF-α | CCL2 | CCL5 | CCL13 | CXCL2 | |

| 0 hrs | 5.70 ± 0.56 | 0.96 ± 0.21 | 36.11 ± 3.02 | 1.94 ± 0.44 | 38.40 ± 5.94 | 19.20 ± 2.77 | 36.80 ± 3.27 |

| 1 hrs | 9.06 ± 0.42* | 1.22 ± 0.46* | 40.26 ± 3.57 | 4.28 ± 0.95* | 47.00 ± 2.12* | 24.00 ± 3.16* | 83.80 ± 11.50** |

| 2 hrs | 16.59 ± 1.81** | 1.82 ± 0.32** | 46.48 ± 7.65* | 12.28 ± 0.79** | 52.40 ± 2.88** | 26.20 ± 6.14** | 147.60 ± 5.98** |

| 4 hrs | 23.21 ± 2.94** | 7.32 ± 2.07** | 66.38 ± 7.72** | 38.54 ± 2.68** | 101.80 ± 5.59** | 63.60 ± 3.36** | 316.00 ± 13.02** |

| 8 hrs | 15.68 ± 0.97** | 22.58 ± 2.03** | 55.63 ± 5.06** | 41.36 ± 2.21** | 150.20 ± 11.30** | 71.60 ± 5.68** | 263.40 ± 16.47** |

| 16 hrs | 11.10 ± 1.08* | 30.14 ± 2.19** | 48.86 ± 2.21** | 32.28 ± 2.30** | 206.00 ± 9.62** | 151.00 ± 16.46** | 206.20 ± 12.19** |

| 24 hrs | 6.31 ± 1.71 | 10.90 ± 0.81** | 41.14 ± 4.67* | 23.86 ± 1.75** | 105.20 ± 9.88** | 105.80 ± 4.27** | 157.20 ± 9.26** |

| 48 hrs | 5.63 ± 0.83 | 6.48 ± 1.16** | 34.68 ± 7.96 | 15.76 ± 2.43** | 129.60 ± 8.26** | 83.20 ± 10.92** | 163.00 ± 12.17** |

P < 0.05;

P < 0.01.

Trauma triggered an inflammatory response in the liver and severely damaged hepatic morphology

Figure 1 shows that at 0 hrs of trauma, the liver cells were tightly distributed with regular acinus, no hyeprchromatic nuclei or invasion of inflammatory cells. However, with increase in trauma time, liver cells showed signs of severe damage as seen by increase in inflammatory cell invasion, formation of hyperchromatic nuclei, and the occurrence of loose and irregular acinus and vacuolus, especially after 16 hrs of trauma.

Figure 1.

Analysis of liver morphology and structure by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. The images indicate that the structure of the liver tissue was loose and severely damaged due to progression of trauma (*: P < 0.05, **: P < 0.01, when compared to 0 hr of trauma).

CD45+ cell number increased significantly with trauma, with peaks at 16 hrs and 24 hrs post-trauma

Compared to that at 0 hrs of trauma, the number of CD45+ cells in the liver parenchyma increased significantly after 4 hrs of trauma and reached maxima 16 hrs and 24 hrs post-trauma (*: P < 0.05, **: P < 0.01) (Figure 2A and 2B).

Figure 2.

Quantitation of the number of CD45+ cells in the liver parenchyma by flow cytometry and histogram analysis. A. The number of CD45+ cells in the liver parenchyma was assayed by flow cytometry; B. Histogram analysis of the number of CD45+ cells in the liver parenchyma. The image indicates that the number of CD45+ cells in the liver parenchyma increased with trauma time and peaked after 16 hrs of trauma (*: P < 0.05, **: P < 0.01, when compared to 0 hr of trauma).

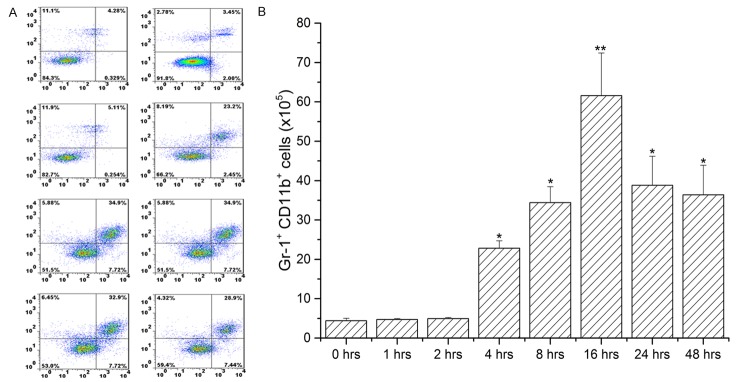

Number of PMNs in the liver increased with trauma

As shown in Figure 3, liver cells stained bright red at 16 hrs and 24 hrs post-trauma, which indicated that the number of PMNs in liver parenchyma had increased. Similarly, flow cytometry (Figure 4A and 4B) showed that compared to the number at 0 hrs of trauma, the number of PMNs increased significantly after 4 hrs of trauma, reached a maxima after 16 hrs of trauma, and decreased slightly at 48 hrs post-trauma (*: P < 0.05, **: P < 0.01).

Figure 3.

Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining to determine the number of PMNs in the liver parenchyma. The images indicate that the liver cells were stained bright red after 16 hrs and 24 hrs of trauma.

Figure 4.

Quantitation of the number of PMNs in liver parenchyma by flow cytometry and histogram analysis. A. The number of PMNs in the liver parenchyma was assayed by flow cytometry; B. Histogram analysis of the number of PMNs in the liver parenchyma. The image indicates that the number of PMNs in the liver parenchyma increased with trauma time and peaked after 16 hrs of trauma (*: P < 0.05, **: P < 0.01, when compared to 0 hr of trauma).

Discussion

In this study, rat trauma hemorrhagic liver injury model was successfully established, which was accompanied by an inflammatory reaction and immunoreaction; this was marked by significant increases in serum levels of ALT and AST, hepatic levels of inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, CCL2, CCL5, CCL13, and CXCL2), numbers of CD45+ cells and PMNs, inflammatory cell invasion, formation of hyperchromatic nuclei, and occurrence of loose and irregular acinus and vacuolus of the liver tissue. Overall, our results indicated that the rat trauma hemorrhagic liver injury model could be used for simulation and evaluation of clinical liver injury.

THS adversely affects the social life of the afflicted due to the high disability and lethality associated with it, and it has been become one of the leading causes of death globally [1,2,10]. After trauma, acute circulatory insufficiency occurs within the tissue, resulting in ischemia and hypoxia [1,9,29]. THS is generally accompanied by inflammation and immune disorder, which may cause serious systemic inflammation, including SIRS and MODS, and damage to distal vital organs [10,30,31]. Several groups have established trauma hemorrhagic animal models to study the mechanism of trauma hemorrhage and to seek a suitable treatment measures for controlling the illness and reducing mortality [1,32-34]. However, the fracture-based trauma hemorrhagic liver injury model is still not reported. Fracture, combined with hemorrhage to establish a trauma hemorrhagic liver injury model, has several advantages. For example, it is a stable system that does not require any expensive device, the bleeding volume is easy to monitor, and the conditions are similar to those of clinical cases of trauma hemorrhages.

Serum levels of ALT and AST are two important indexes for assessing liver function. Here, we evaluated the extent of liver injury by determining the levels of ALT and AST, which significantly increased with trauma time, peaked at 16 hrs post-trauma, and decreased slightly after 48 hrs of trauma, indicating that with prolonged trauma, liver injury first increased maximally, followed by a moderate decrease. We hypothesized that levels of inflammatory cytokines may be altered with liver injury. As expected, the levels of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, CCL2, CCL5, CCL13, and CXCL2 increased significantly with trauma time and reached a peak at 8 hrs or 16 hrs post-trauma, indicating that inflammatory reactions had occurred in the fraction-induced hemorrhage of liver.

The activity of the immune system is significantly altered with the aggravation of clinical THS. For example, levels of PMNs, mononuclear cells, and dendritic cell increase in THS [17,18]. In this study, the numbers of CD45+ cells and PMNs, quantitated by flow cytometry, increased significantly with trauma time and reached a peak at 16 hrs post-trauma. This indicates that after trauma infliction, the immune cell population increased locally to provide tolerance towards the injury-induced inflammation, which simulated the immune reaction of the body in response to trauma hemorrhage-induced liver injury. With longer duration of the trauma, the liver cells exhibited morphological changes such as invasion of inflammatory cells, formation of hyperchromatic nuclei, and occurrence of loose and irregular acinus and vacuolus, thereby indicating that after the fraction-induced hemorrhage, the morphology and structure of the hepatic tissue had changed significantly. Taken together, our results underscore the effectiveness of this model in mimicking clinical cases of liver injury. However, few points are critical for successfully utilizing our model system. First, the rat bleeding volume has to be accurately monitored to maintain the low blood pressure and second, the entire operation has to be performed under sterile conditions.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the “Twelfth Five-Year Plan” Key Scientific Research Foundation of PLA (BWS12J051).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Leung LY, Deng-Bryant Y, Shear D, Tortella F. Experimental models combining TBI, hemorrhagic shock, and hypoxemia. Methods Mol Biol. 2016;1462:445–458. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-3816-2_25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carrick MM, Leonard J, Slone DS, Mains CW, Bar-Or D. Hypotensive resuscitation among trauma patients. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:8901938. doi: 10.1155/2016/8901938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weber CD, Herren C, Dienstknecht T, Hildebrand F, Keil S, Pape HC, Kobbe P. Management of life-threatening arterial hemorrhage following a fragility fracture of the pelvis in the anticoagulated patient: case report and review of the literature. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil. 2016;7:163–167. doi: 10.1177/2151458516649642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Demling RH. Role of prostaglandins in acute pulmonary microvascular injury. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1982;384:517–534. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1982.tb21397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwartz P. [Respiratory distress due to traumatic lesions in newborn infants and in adults] . Fortschr Med. 1975;93:1133–1138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bigelow WG. The Microcirculation. Some physiological and philosophical observations concerning the peripheral vascular system. Can J Surg. 1964;7:237–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simon DW, Vagni VM, Kochanek PM, Clark RS. Combined neurotrauma models: experimental models combining traumatic brain injury and secondary insults. Methods Mol Biol. 2016;1462:393–411. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-3816-2_22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Slaughter AL, D’Alessandro A, Moore EE, Banerjee A, Silliman CC, Hansen KC, Reisz JA, Fragoso M, Wither MJ, Bacon A, Moore HB, Peltz ED. Glutamine metabolism drives succinate accumulation in plasma and the lung during hemorrhagic shock. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;81:1012–1019. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu FC, Zheng CW, Yu HP. Maravirocmediated lung protection following traumahemorrhagic shock. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:5302069. doi: 10.1155/2016/5302069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rossignol M. Trauma and pregnancy: what anesthesiologist should know. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2016;35(Suppl 1):S27–S34. doi: 10.1016/j.accpm.2016.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar M, Bhoi S, Subramanian A, Kamal VK, Mohanty S, Rao DN, Galwankar S. Evaluation of circulating haematopoietic progenitor cells in patients with Trauma Haemorrhagic shock and its correlation with outcomes. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2016;6:56–60. doi: 10.4103/2229-5151.183016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhoi S, Tiwari S, Kumar M. What’s new in critical illness and injury science? Estrogen: is it a new therapeutic paradigm for trauma-hemorrhagic shock? Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2016;6:53. doi: 10.4103/2229-5151.183021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Acker SN, Petrun B, Partrick DA, Roosevelt GE, Bensard DD. Lack of utility of repeat monitoring of hemoglobin and hematocrit following blunt solid organ injury in children. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;79:991–994. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000791. discussion 994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gonzalez-Lopez R, Garcia-Cano E, Espinosa-Gonzalez O, Cruz-Salgado A, Montiel-Jarquin AJ, Hernandez-Zamora V. [Surgical treatment for liver haematoma following endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; An unusual case] . Cir Cir. 2015;83:506–509. doi: 10.1016/j.circir.2015.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sordi R, Chiazza F, Johnson FL, Patel NS, Brohi K, Collino M, Thiemermann C. Inhibition of IkappaB kinase attenuates the organ injury and dysfunction associated with hemorrhagic shock. Mol Med. 2015;21:563–575. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2015.00049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Witowski NE, Lusczek ER, Determan CE, Lexcen DR, Mulier KE, Wolf A, Ostrowski BG, Beilman GJ. Metabolomic analysis of survival in carbohydrate pre-fed pigs subjected to shock and polytrauma. Mol Biosyst. 2016;12:1638–1652. doi: 10.1039/c5mb00637f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zingarelli B, Chima R, O’Connor M, Piraino G, Denenberg A, Hake PW. Liver apoptosis is age dependent and is reduced by activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptorgamma in hemorrhagic shock. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2010;298:G133–141. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00262.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ono M, Yu B, Hardison EG, Mastrangelo MA, Tweardy DJ. Increased susceptibility to liver injury after hemorrhagic shock in rats chronically fed ethanol: role of nuclear factor-kappa B, interleukin-6, and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Shock. 2004;21:519–525. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000126905.75237.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao H, Hao S, Xu H, Ma L, Zhang Z, Ni Y, Yu L. Protective role of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 in the hemorrhagic shockinduced inflammatory response. Int J Mol Med. 2016;37:1014–1022. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2016.2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ziraldo C, Vodovotz Y, Namas RA, Almahmoud K, Tapias V, Mi Q, Barclay D, Jefferson BS, Chen G, Billiar TR, Zamora R. Central role for MCP-1/CCL2 in injury-induced inflammation revealed by in vitro, in silico, and clinical studies. PLoS One. 2013;8:e79804. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hamilton GJ, Van PY, Differding JA, Kremenevskiy IV, Spoerke NJ, Sambasivan C, Watters JM, Schreiber MA. Lyophilized plasma with ascorbic acid decreases inflammation in hemorrhagic shock. J Trauma. 2011;71:292–297. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31821f4234. discussion 297-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kobbe P, Stoffels B, Schmidt J, Tsukamoto T, Gutkin DW, Bauer AJ, Pape HC. IL-10 deficiency augments acute lung but not liver injury in hemorrhagic shock. Cytokine. 2009;45:26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shang Y, Jiang YX, Ding ZJ, Shen AL, Xu SP, Yuan SY, Yao SL. Valproic acid attenuates the multiple-organ dysfunction in a rat model of septic shock. Chin Med J (Engl) 2010;123:2682–2687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Not LG, Brocks CA, Vamhidy L, Marchase RB, Chatham JC. Increased O-linked beta-Nacetylglucosamine levels on proteins improves survival, reduces inflammation and organ damage 24 hours after trauma-hemorrhage in rats. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:562–571. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181cb10b3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharma P, Mongan PD. Hypertonic sodium pyruvate solution is more effective than Ringer’s ethyl pyruvate in the treatment of hemorrhagic shock. Shock. 2010;33:532–540. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181cc02b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gentile LF, Nacionales DC, Cuenca AG, Armbruster M, Ungaro RF, Abouhamze AS, Lopez C, Baker HV, Moore FA, Ang DN, Efron PA. Identification and description of a novel murine model for polytrauma and shock. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:1075–1085. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318275d1f9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hsu JT, Kan WH, Hsieh CH, Choudhry MA, Bland KI, Chaudry IH. Role of extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase (ERK) in 17betaestradiol-mediated attenuation of lung injury after trauma-hemorrhage. Surgery. 2009;145:226–234. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feinman R, Deitch EA, Watkins AC, Abungu B, Colorado I, Kannan KB, Sheth SU, Caputo FJ, Lu Q, Ramanathan M, Attan S, Badami CD, Doucet D, Barlos D, Bosch-Marce M, Semenza GL, Xu DZ. HIF-1 mediates pathogenic inflammatory responses to intestinal ischemiareperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2010;299:G833–843. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00065.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu FC, Chaudry IH, Yu HP. Hepatoprotective effects of corilagin following hemorrhagic shock are through Akt-dependent pathway. Shock. 2017;47:346–351. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weber CD, Lefering R, Dienstknecht T, Kobbe P, Sellei RM, Hildebrand F, Pape HC TraumaRegister DGU. Classification of soft-tissue injuries in open femur fractures-relevant for systemic complications? J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;81:824–833. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stankovic B, Stojanovic G. Chemotherapy analysis in massive transfusion syndrome. Med Pregl. 2016;69:37–43. doi: 10.2298/mpns1602037s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Orfanos NF, Mylonas AI, Karmaniolou II, Stergiou IP, Lolis ED, Dimas C, Papalois AE, Kondi-Pafiti AI, Smyrniotis VE, Arkadopoulos NF. The effects of antioxidants on a porcine model of liver hemorrhage. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;80:964–971. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Song Z, Zhao X, Liu M, Jin H, Wang L, Hou M, Gao Y. Recombinant human brain natriuretic peptide attenuates trauma-/haemorrhagic shock-induced acute lung injury through inhibiting oxidative stress and the NF-kappaBdependent inflammatory/MMP-9 pathway. Int J Exp Pathol. 2015;96:406–413. doi: 10.1111/iep.12160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moore HB, Moore EE, Morton AP, Gonzalez E, Fragoso M, Chapman MP, Dzieciatkowska M, Hansen KC, Banerjee A, Sauaia A, Silliman CC. Shock-induced systemic hyperfibrinolysis is attenuated by plasma-first resuscitation. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;79:897–903. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000792. discussion 903-894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]