Abstract

Recent evidence has indicated that miRNAs play important roles in carcinogenesis. The identification of dysregulated miRNAs and the target genes they regulate might enhance our understanding of the molecular mechanisms of nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC). microRNA-140 (miR-140) has been found to be down-regulated in cancer. However its role in nasopharyngeal carcinoma remains unclear. CXCR4 was predicted to be the target gene of miR-140. The current research was designed to delineate the mechanism of miR-140 in regulating NPC via targeting CXCR4. In this study, miR-140 was underexpressed in NPC tissues and cell lines compared with their normal controls and the biological function and direct target genes of miR-140 in NPC cells were investigated. Importantly, we demonstrate that the over expression of miR-140 significantly inhibits NPC cell proliferation and induces apoptosis. Additionally, CXCR4 was predicted the target gene of miR-140 and the luciferase reporter assay revealed that miR-140 was directly bound to the 3’-UTR of CXCR4. Furthermore, CXCR4 was inversely correlated with the expression of miR-140 in NPC cells. Taken together, our results suggest miR-140 suppresses tumor proliferation and induces apoptosis by inhibiting CXCR4, which might provide a new insight into the molecular mechanisms that regulate the development and progression of NPC, and it provides novel therapeutic targets for NPC.

Keywords: Nasopharyngeal carcinoma, miR-140, CXCR4, proliferation, apoptosis

Introduction

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is a malignant squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck that is highly prevalent in Southeast Asia, Middle East and North Africa [1,2]. Although the incidence of NPC responds well when treated with radiation therapy and adjuvant chemotherapy and the 5-year overall survival rate is approximately 70 [3]. However, NPC can invade local tissues easily and within 4 years, 30-40% of patients will develop distant metastases with poor prognosis [4]. It remains one of the major causes of cancer-related deaths and the prognosis of patients with NPC remains very poor due to recurrence and distant metastasis [5]. Therefore, a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis and progression of NPC using currently available genomic approaches might improve therapies for NPC patients.

The discovery of noncoding RNAs in the human genome was an important scientific break through that promoted further investigation of the potential roles of these molecules in human biology and pathology. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a class of small, endogenous, single-stranded, noncoding RNAs, that play a key role in cellular process, such as proliferation, apoptosis, differentiation, invasion and metabolism and gene expression by targeting the 3’ untranslated region (3’ UTR) of specific mRNAs [6] in a sequence-specific manner. Several reports have shown that miRNAs can regulate the expression of a variety of genes which associated with many cancers, including blood system [7], brain [8], breast [9], and nose and pharynx cancers [10]. Recently, several miRNAs have been found play critical roles in the regulation of cancer initiation and progression [11], such as miR-663, miR-144, miR-26a, miR-451 and miR-9 [12]. Human miR-140 has been reported to be involved in progression of several cancers [13,14], miR-140 plays a tumor suppressor in non-small cell lung cancer [15], tongue squamous cell carcinoma [16], hepatocellular carcinoma [17]. In lung cancer, miR-140 targeting MMD inhibits cell proliferation via suppressing MAPK signal pathway. In tongue squamous cell carcinoma, miR-140 attenuates tumor progression and metastasis including migration and invasion via ADAM10 by down-regulation of LAMC1, HDAC7 and PAX6 expression. In hepatocellular carcinoma, miR-140 suppressed HCC cell proliferation and HCC metastasis by inhibiting MAPK signaling pathway, but its specific roles and mechanisms in NPC have not been well established. In the present study, the expression levels of miR-140 were found to be significantly down-regulated in NPC cell lines. NPC cell proliferation, migration, invasion and tumor growth in the xenograft mouse model were all strongly suppressed when miR-140 was overexpressed. However, no study has elucidated the functional roles or molecular mechanisms of miR-140 in the development and progression of NPC.

In this study, we clearly demonstrate that miR-140 is downregulated in NPC cells. We provide evidence that miR-140 may supress cell growth, colony formation, migration and invasion, indicating that miR-140 is involved in the initiation and progression of NPC. Furthermore, CXCR4 was found to be a direct target gene of miR-140 and overexpression of CXCR4 could rescue miR-140-induced biological functions. In addition, a negative correlation between the expression of miR-140 and CXCR4 was found in NPC specimens. Collectively, our data indicate that miR-140 plays a tumor suppressor role in the development and progression of NPC and the miR-140/CXCR4 pathway helped clarify the roles of miRNAs in the development of NPC, it may provide novel therapeutic targets for NPC.

Materials and methods

Tissue samples and cells

Human clinical samples were collected from surgical specimens from patients in Jiangsu Cancer Hospital according to a standard protocol, before any therapeutic intervention. The corresponding adjacent non-neoplastic tissues from the macroscopic tumor margin were isolated at the same time and used as controls. Informed consent was obtained from all patients and the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Jiangsu Cancer Hospital. The human NPC cell lines CNE-1, CNE-2 and HONE-1 were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco, Life Technolo-gies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovineserum (FBS; Gibco). The human immortalized nasopharyngeal epithelial cell line NP69 was grown in keratinocyte/serum-free medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with growth factors bovine pituitary extract. (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA). All cells were incubated in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator at 37°C.

Cells transfection

CNE-1 and HONE-1 cells (4×104) were seeded in six-well plates and transiently transfected with miR-155 lentivirus and miR-155 NC using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Life Technologies Corporation, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for 24 h as the manufacturer’s instructions. Then the cells were harvested 48 h after transfection for the specified assays. NPC were The transfected efficacy was evaluated by qRT-PCR.

RNA extraction and quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and total RNA was reverse transcribed using M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) to detect the expression of miR-140 according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using the Quanti-TectSYBR Green PCR mixture on an ABI PRISM 7900 Sequence DetectionSystem (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The expression level of GAPDH was used as an internal control for mRNAs, and U6 level was regarded as the internal miRNA control using the 2-ΔΔCT method, respectively. All of the reactions were performed in triplicate.

Western blot analysis

Cells were washed with cold PBS and lysed in radio immunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer plus protease inhibitors (Roche, IN, USA). Protein concentrations were determined using a Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific, Logan, UT, USA). Total proteins were separated on 10% SDS-PAGE gels and then transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, Boston, MA, USA). The membranes were blocked with 5% milk in TBST buffer for 2 h at 4°C, and incubated with primary antibodies against CXCR4 at 4°C overnight. Unbound antibody was removed by washing in TBST buffer three times (10 min/wash). The membranes were incubated with secondary antibody at room temperature for 2 h and followed by washing with TBST buffer three times. The bands were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) and GAPDH was used as a loading control. All data analyses were repeated three times independently.

Cell viability assay and colony formation assay

Cell viability was assayed by MTT assay. After transfection for 48 h, CNE-1 and HONE-1 cells were collected and seeded in 96-well plates. Briefly, the cells were stained with 20 ml of MTT dye (0.5 mg/ml; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) and cells were incubated at 37°C for 4 h. Then 100 ml dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO, Sigma) was added to dissolve the formazan crystals at 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 days. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm with a Thermo Varioskan Flash reader, the experiment was repeated three times and the results were averaged.

For the colony formation assay, transfected CNE-1 and HONE-1 cells were seeded into six-well plates and cultured for 10 days. Colonies were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde solution, stained with 0.5% crystal violet for 20 min and visualized colonies under an inverted microscope. The experiments were performed three times.

In vitro migration and invasion assays

The wound healing assay and transwell assay was performed to assess cell migration ability. Transfected CNE-1 and HONE-1 cells were collected and seeded in six-well plates. After serum starvation in serum-free media for 24 h, a single wound was created in the center of the cell monolayer using a standard 200 μL plastic pipette tip. Cells migrate into the scratch area as single cells from the confluent sides, the wound areas were viewed under an optical microscope with a magnification of 100. Cell migration capability was expressed by gap closure.

In addition, cell invasion was conducted using Transwell chambers (Corning, Steuben County, New York, USA). In brief, 5×104 CNE-1 or HONE-1 transfected cells were harvested and then suspended in 200 μl of serum-freemedia and plated into the upper chamber. The lower chamber was filled with 500 μl of RPMI-1640 and 10% FBS as a chemoattractant. After incubation for 24 h, the cells invaded through the membrane to the lower surface were fixed and stained with 0.5% crystal violet. Six random fields of cells were counted under a microscope (Olympus Corp., Tokyo, Japan). The results were averaged over three independent experiments.

Cell apoptotic assay

We performed apoptosis assay to determine the effects of miR-140 on apoptosis of CNE-1 and HONE-1 cells. Briefly, after 48 h of transfection with lentivirus, the cells were harvested, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and fixed with cold methanol overnight. Then the cells were incubated with 1× binding buffer supple-mented with Annexin V-FITC (10 μl) and propidium iodide (PI) (5 μl) for 30 min in the dark at room temperature. Early apoptotic cells were positive for Annexin V and negative for PI, and while late apoptotic cells were both Annexin V- and PI-positive. Apoptotic cells were subjected to FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA) and the data were analyzed using CELL Quest 3.0 software (BD, NJ, USA). Each condition was repeated 3 times.

Luciferase assays

The luciferase reporter assay was performed as described previously [18]. The wild-type (Wt) KRAS 3’ untranslated region (UTR) was cloned downstream of the firefly luciferase gene in the psiCHECK-2 vector (Promega) and a mutant (Mt) 3’ UTR plasmid was then created using site-directed mutagenesis. The cells were cultured in 24-well plates and transfected with 100 ng luciferase reporter plasmid and 5 ng pRL-TK vector expressing the Renilla luciferase (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen; Grand Island, NY, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Cells were harvested 48 h after transfection and luciferase activities were determined with the Dual-Luciferase Reporter System (Promega; Madison, AL, USA). All assays were conducted in triplicate and repeated three times independently.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as the means ± standard deviation from at least three independent experiments. Differences between the groups were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) by GraphPad Prism version 4.0 for Windows software. The relationship between miR-140 expression and CXCR4 mRNA expression level was analyzed using Spearman’s correlation and Data were tested for normality using SPSS 20.0 software (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). A value of P<0.05 was considered as statistical significant.

Results

miR-140 is down regulated and CXCR4 is upregulated in nasopharyngeal carcinoma tissues and cell lines

In order to explore the expression and significance of miR-140 in in nasopharyngeal carcinoma carcinogenesis, we firstly examined the expression level of miR-140 using quantitative RT-PCR analysis and the expression level of CXCR4 by western blotting in nasopharyngeal carcinoma tissues and paired non-cancerous tissues. The results indicated that miR-140 was markedly down-regulated in nasopharyngeal carcinoma tissues compared with adjacent non-cancerous tissues (Figure 1A, 1B), which suggested that the expression of miR-140 may be associated with nasopharyngeal carcinoma carcinogenesis.

Figure 1.

Expression levels of miR-140 and CXCR4 in NPC tissues and cell lines. (A) miR-140 expression in NPC tissues and the normal tissues was examined by qRT-PCR. (B) CXCR4 expression in NPC tissues and the normal tissues was examined by western blotting. (C) Expression levels of miR-140 in three NPC cell lines and NP69 cells through quantitative RT-PCR. (D) Western blotting analysis of CXCR4 expression levels in the NP69 and NPC cell lines. GAPDH antibody was used as the loading control. (E) The migratory ability of cells was determined by transwell. Cells migrated through the memberane were viewed at ×400 magnifications under light microscope, counted in 4 independent visual fileds SEMper transwell membrane. Cell numbers were presented as values of means ± SD of triplicate experiments. *P<0.05. (F) The in invasive ability of four cells was further determined by same assay, as described in (E).

To identify whether this under-expression only exit in nasopharyngeal carcinoma tissues, we further analyzed miR-140 expression in three NPC cells lines (CNE-1, CNE-2 and HONE-1) and normal nasopharyngeal epithelial cell line (NP69). The expression of miR-140 was universally decreased in these three NPC cell lines then cell line NP69 (Figure 1C) and the amount of CXCR4 protein expressed in NP69 is lowest about four cell lines (Figure 1D). These results are suggest that miR-140 was significantly downregulated and observed the CXCR4 expression was increased in NPC cell lines. Finally, CNE-1 and HONE-1 cells were picked out for further experiments. Thus, our results indicated a inverse correlation between CXCR4 expression and miR-140 expression in human NPC.

miR-140 suppresses NPC cell proliferation in vitro

As miR-140 expression significantly decreases in NPC and to determine whether miR-140 silencing affected cell viability and proliferation, we performed loss-of-function studies by transfecting siRNAs into CNE-1 and HONE-1 cells. The transfection efficiency was verified by using RT-PCR analysis (Figure 2A). The viability of the cells transfected with simiR-140 was markedly inhibited, according to the MTT assay. The results revealed that the cell viability of CNE-1 and HONE-1 cells which transfected with lentivirus were significantly induced when compared with those of lenti-NC infected cells (Figure 2B). The colony formation demonstrated that miR-140 silencing formed significantly more and larger colonies compared to those of lenti-NC cells (Figure 2C). These results suggest that miR-140 plays a proliferation-inhibiting role in NPC cells.

Figure 2.

miR-140 suppresses NPC cell proliferation in vitro. A. Relative miR-140 expression was examined by RT-PCR. B. Cell viability was examined by MTT assay. C. miR-140 suppressed CNE-1 and HONE-1 cell colony formation (left). Quantitative analysis of CNE-1 and HONE-1 colony numbers (right).

miR-140 inhibits cell invasion and migration in NPC cell lines

To verify whether miR-140 regulates the cell migration and invasion in NPC cell lines, wound-healing assay and transwell assay were conducted. As shown in Figure 3A, we performed wound healing assays on CNE-1 and HONE-1 cells transfected with lentivirus and found that this treatment significantly increased migration speeds in both cell lines in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 3A). Similarly, transwell assay showed that the number of migrated cells in the control group was significantly less than that in Lv-miR-140 cells group (Figure 3B). Moreover, we sought to evaluate the effects of miR-140 on cell invasion using Transwell assays. In addition, the transwell invasion assay showed that the capacity for invasion of NPC cells transfected with lentivirus was also obviously higher than those infected with lenti-NC (Figure 3C). Taken together, the data mentioned above suggest that miR-140 performed important roles in regulating cells migration and invasion in NPC and up-regulation of miR-140 might contribute to tumor metastasis in NPC carcinogenesis.

Figure 3.

Downregradulation the expression of miR-140 promotes NPC cell migration and invasion. A. Wound healing assay. Photomicrographs were taken at 0, 24, and 48 h after cell wounding. B. Transwell migration assay for NPC cells which transfected with lentivirus. Representative images (left) and quantification (right). C. Cell invasion capability was determined by transwell assay.

miR-140 induced the apoptosis of NPC cells

To investigate the biology functions of miR-140 on NPC cells apoptosis, CNE-1 and HONE-1 cells were used and transfected with lentivirus. As demonstrated in Figure 4A, 4B, the apoptotic cells were significantly lower in the suppression of miR-140 group than the cells in the control group (P<0.05). These results indicate that miR-140 induced apoptosis in NPC cells.

Figure 4.

miR-140 induced NPC cells apoptosis. A, B. Cell apoptosis was analyzed by flow cytometry in two different groups: Lenti-miR153 and Lenti-NC. C, D. Apoptosis-related molecules were detected by western blot. P<0.001.

To further investigate the potential mechanism by which miR-140 inhibits cell growth, the expression patterns of cell apoptotic molecules Bcl-2, caspase-3, and PARP were analyzed by western blot assay. As shown in Figure 4C, 4D, we found that the expression levels of Bcl-2 and caspase-3 were obviously increased in the cells which transfected with lentivirus compared with lenti-NC group. Correspondingly, the protein levels of cleaved caspase-3 and PARP were significantly decreased in the Lenti-miR153 group. The above results suggest that knockdown of miR153 affects NPC cell growth via the regulation of Bcl-2, caspase-3, and PARP expression.

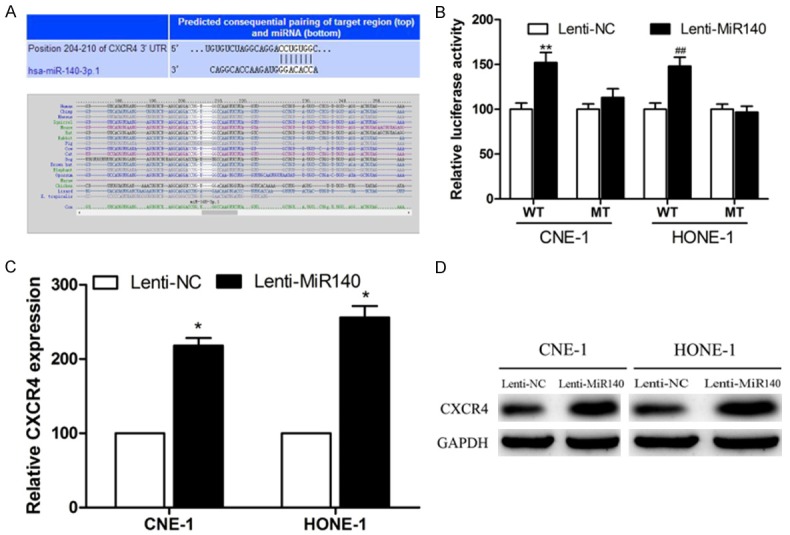

CXCR4 is a direct target of miR-140

To explore the underlying molecular mechanism of miR-140 regulative role in NPC, we used several bioinformatics methods, including TargetScan, miRWalk and miRanda to analyze target gene of miR-140 (24). Software analysis revealed that CXCR4 might be a potential target of miR-140 based on putative target sequences of the CXCR4 3’ UTR (Figure 5A). We further performed luciferase assay to determine whether miR-140 could directly target 3’-UTR of CXCR4, we constructed both a wide type and a mutant of firefly luciferase reporters containing the 3’-UTR of CXCR4. As shown in Figure 5B, miR-140 significantly decreased the luciferase activity of the CXCR4 3’-UTR but not mutant sequence. In addition, to clarify their regulatory relationship, we performed qRT-PCR and western blot analysis to detect the CXCR4 expression level (Figure 4C, 4D), which results revealed that the inhibition of miR-140 enhanced the expression of CXCR4. Consistently, these results suggested that CXCR4 was a direct target of miR-140 in NPC.

Figure 5.

miR-140 negatively regulates the expression of CXCR4 by directly targeting the CXCR4 3’ UTR. A. Sequence alignment of a putative miR-140 binding site in the 3’-UTR of CXCR4 mRNA. B. Luciferase activity of the wild-type (WT) and the mutant (MUT). Data are expressed as mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments (P<0.05). C. Quantification of CXCR4 mRNA expression by quantitative RT-PCR. D. CXCR4 protein expression by western blotting in CNE-1 and HONE-1 cells transfected with lentivirus. Values are mean ± SD; P<0.01.

Discussion

The prognosis of patients with NPC remains poor because of the recurrence and high rate of distant metastasis [19]. Studies have revealed that miRNAs have a significant role in human cancers. MiRNAs are key regulators of numerous cellular processes, and abnormal expression of miRNAs has been closely related to the initiation and progression of malignant tumors. Previous studies have suggested that microRNAs played critical roles as oncogenes or tumor suppressors factors via controlling different target genes in human cancers. Moreover, specific miRNA expression profiles have been identified in NPC.

We studied the expression profile of miR-140, which is downregulated in several malignancies, including HCC [20], non-small cell lung cancer [21] and triple negative breast cancer [22]. It would be potentially interesting to evaluate if replenishment of miR-140 levels will lead to better sensitivity to in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. In this study, quantitative real-time PCR was conducted to analysis miR-140 expression in NPC samples and normal tissue samples. We have evaluated the biological effects of miR-140 on endometrial cancer cell growth in vitro. We observed that the expression level of miR-140 was significantly reduced in NPC tissues and cell lines compared with adjacent non-neoplastic tissues and NP69. These data prompted us to investigate the regulation of miR-140 in NPC cells. Cell migration and invasion is one of the essential events in cancer metastasis. Our data revealed that downregulation of miR-140 significantly promoted cell proliferation, migration, invasion and apoptosis in both CNE-1 and HONE-1 cell lines transfected with lentixirus. Cell viability and colony formation assays verified that the ectopic expression of miR-140 in the NPC cell lines increased cell proliferation. Flow cytometry indicated that miR-140 silencing inhibited cell apoptosis through upregulation of caspase 3 and Bcl-2 and downregulation of cleaved caspase 3 and PARP. Western blots revealed that the reduced migration and invasion by miR-140 were probably associated with the inhibited expression of CXCR4.

To further understand the mechanisms underlying the ability of miR-140 to promote cell growth, migration and invasion in NPC, public bioinformatic algorithms predicted CXCR4 to be a theoretical target gene of miR-140. As miRNAs exert their function through direct binding to the 3’-UTRs of their target genes, miR-140 significantly suppressed the luciferase activity of CXCR4-3’ UTR by targeting the 3’ UTR of CXCR4 mRNA. Restoring the expression of CXCR4 can reverse the suppressive effects of miR-140. Hence, we examined the expression levels of CXCR4 in NPC tissues and CXCR4 was remarkably up-regulated in NPC. Furthermore, we found a negative correlation between the expression of miR-140 and CXCR4.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that miR-140 might play an carcinostasis role, by regulating CXCR4 expression in NPC cells. miR-140 is also believed to modulate the malignant behavior by inhibiting nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell proliferation, migration and invasion by directly targeting the potent tumor suppressor CXCR4. This finding might provide us new insights into a potential diagnostic and therapeutic strategy for blocking metastasis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grants from the JiangSu Clinical medicine Science and Technology Special Fund (No:BL2014091, http://www.jstd.gov.cn/). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Chou J, Lin YC, Kim J, You L, Xu Z, He B, Jablons DM. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma & mdash; review of the molecular mechanisms of tumorigenesis. Head Neck. 2008;30:946–63. doi: 10.1002/hed.20833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang ET, Adami HO. The enigmatic epidemiology of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:1765–1777. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee AW, Yau TK, Wong DH, Chan EW, Yeung RM, Ng WT, Tong M, Soong IS, Sze WM. Treatment of stage IV(A-B) nasopharyngeal carcinoma by induction-concurrent chemoradiotherapy and accelerated fractionation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;66:1004–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lai SZ, Li WF, Chen L, Luo W, Chen YY, Liu LZ, Sun Y, Lin AH, Liu MZ, Ma J. How does intensity-modulated radiotherapy versus conventional two-dimensional radiotherapy influence the treatment results in nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;80:661–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.He L, Hannon GJ. MicroRNAs: small RNAs with a big role in gene regulation. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5:522–31. doi: 10.1038/nrg1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaur P, Armugam A, Jeyaseelan K. MicroRNAs in neurotoxicity. J Toxicol. 2012;2012:870150. doi: 10.1155/2012/870150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garzon R, Calin GA, Croce CM. MicroRNAs in cancer. Annu Rev Med. 2009;60:167–179. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.59.053006.104707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dixon-Mciver A, East P, Mein CA, Cazier JB, Molloy G, Chaplin T, Andrew LT, Young BD, Debernardi S. Distinctive patterns of microRNA expression associated with karyotype in acute myeloid leukaemia. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2141. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kefas B, Godlewski J, Comeau L, Li Y, Abounader R, Hawkinson M, Lee J, Fine H, Chiocca EA, Lawler S. microRNA-7 inhibits the epidermal growth factor receptor and the Akt pathway and is down-regulated in glioblastoma. Cancer Res. 2008;68:3566. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang Z, He M, Wang K, Sun G, Tang L, Xu Z. Tumor suppressive microRNA-193b promotes breast cancer progression via targeting DNAJC13 and RAB22A. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:7563–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li F, Jiang W, Yang X, Yin Z, Feng X, Liu W, Wang L, Zhou W, Yao K. Cloning and identification of NAP1: a novel human gene down--regulated in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Progress in Biochemistry & Biophysics. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Y, Zhou Y, Feng X, An P, Quan X, Wang H, Ye S, Yu C, He Y, Luo H. MicroRNA-126 functions as a tumor suppressor in colorectal cancer cells by targeting CXCR4 via the AKT and ERK1/2 signaling pathways. Int J Oncol. 2014;44:203–210. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2013.2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yi C, Wang Q, Wang L, Huang Y, Li L, Liu L, Zhou X, Xie G, Kang T, Wang H. MiR-663, a microRNA targeting p21(WAF1/CIP1), promotes the proliferation and tumorigenesis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Oncogene. 2012;31:4421–4433. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li W, He F. Monocyte to macrophage differentiation-associated (MMD) targeted by miR-140-5p regulates tumor growth in non-small cell lung cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;450:844–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.06.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kai Y, Peng W, Ling W, Jiebing H, Zhuan B. Reciprocal effects between microRNA-140-5p and ADAM10 suppress migration and invasion of human tongue cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;448:308–314. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hwang S, Park SK, Lee HY, Kim SW, Lee JS, Choi EK, You D, Kim CS, Suh N. miR-140-5p suppresses BMP2-mediated osteogenesis in undifferentiated human mesenchymal stem cells. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:2957–2963. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shen K, Liang Q, Xu K, Cui D, Jiang L, Yin P, Lu Y, Li Q, Liu J. MiR-139 inhibits invasion and metastasis of colorectal cancer by targeting the type I insulin-like growth factor receptor. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;84:320. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell. 2005;120:15. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xia W, Ma X, Li X, Dong H, Yi J, Zeng W, Yang Z. miR-153 inhibits epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in hepatocellular carcinoma by targeting snail. Oncol Rep. 2015;34:655. doi: 10.3892/or.2015.4008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen WJ, Zhang EN, Zhong ZK, Jiang MZ, Yang XF, Zhou DM, Wang XW. MicroRNA-153 expression and prognosis in non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;8:8671–8675. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fkih MhI, Privat M, Ponelle F, Penault-Llorca F, Kenani A, Bignon YJ. Identification of miR-10b, miR-26a, miR-146a and miR-153 as potential triple-negative breast cancer biomarkers. Cell Oncol. 2015;38:433–42. doi: 10.1007/s13402-015-0239-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Q, Yao Y, Eades G, Liu Z, Zhang Y, Zhou Q. Downregulation of miR-140 promotes cancer stem cell formation in basal-like early stage breast cancer. Oncogene. 2014;33:2589–600. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]