Abstract

Statins are widely used drugs for lowering low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and can prevent cardiovascular events. This study aimed to evaluate the influence of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and their cumulative effects on the prognosis of coronary artery disease (CAD) patients treated with statins. Sixteen SNPs were genotyped in 785 CAD patients receiving statin therapy, and their associations with clinical features and prognosis of patients were investigated. Four SNPs (rs2296651, rs11206510, rs8192870, and rs1801133) were significantly associated with complications of CAD (P<0.05). Four SNPs (rs8192870, rs4149056, rs12916, and rs2231142) affected blood lipid levels (P<0.05). Furthermore, rs1801133 showed a weak but significant association with fasting plasma glucose (P = 0.033). Survival analyses showed that rs11206510 (adjusted HR = 1.891, 95% CI: 1.188-3.010, P = 0.007) and rs1801133 (adjusted HR = 1.499, 95% CI: 1.141-1.971, P = 0.004) were independently associated with an increased risk of major cardiovascular events, and exhibited cumulative effect on even-free survival (adjusted HR = 1.810, 95% CI: 1.179-2.802, P = 0.007). In conclusion, rs11206510 and rs1801133 were independent risk factors for clinical outcome in CAD patients treated with statins.

Keywords: Statin, coronary artery disease, prognosis, major cardiovascular event

Introduction

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is the leading cause of death worldwide [1]. Elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) is the most common cause of CAD. Effective reduction of LDL-C can prevent the progress of atherosclerosis, and thereby reduce the incidence of mortality caused by CAD. Statins, inhibitors of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase (HMGCR), are the most efficient drugs used to reduce LDL-C and cardiovascular events. However, individual differences existin the effects of statins on the prognosis of CAD, and the underlying mechanism remains unclear.

The lipid-regulating mechanisms of statins is mainly through competitively inhibiting HMG-CoA reductase, a key enzyme in the cholesterol synthesis, to reduce the intracellular free cholesterol, which stimulate upregulation of low density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) on the surface of hepatocytes, accelerate plasma LDL-C uptake, and thus reduce plasma LDL-C level [2]. The reduction of LDL-C by each mmol/L can reduce major cardiovascular events by approximately 20% [3]. Furthermore, statins mitigate inflammation by modulating the expression of genes involved in inflammatory and immune responses [4-6], which further reduce the risk of major cardiovascular events. Although statins are the most widely used lipid-lowering drugs, apparent individual differences exist in the lipid-lowering effects of these drugs. It has been demonstrated that such individual differences in drug response are associated with genetic variants in enzymes and transport proteins involved in drug metabolism and transport, and drug targets. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) affect the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of statins and thus influences the clinical efficacy and safety of statins. In this regard, numerous studies have been conducted to clarify the pharmacogenetics of statins [7-10], but there are no report concerning the effects of SNPs on the prognosis of CAD patients administered with statins.

In the present study, we evaluated the effects of 16 SNPs related to the efficacy and toxicity of statins on the prognosis of CAD patients receiving statins. SNPs, which are found to be related to the prognosis of CAD patients treated with statins, may be served as biomarkers to guide personalized therapy to more effectively manage CAD complicated with hyperlipemia.

Materials and methods

Patients

A total of 785 CAD patients, consisting of 530 males and 255 females and with mean age of 63.7 ± 10.8 years, were enrolled from Taizhou People’s Hospital between October 2009 and July 2013. All patients exhibited narrowing (≥50%) in at least one of three major coronary arteries (left anterior descending branch, left circumflex artery, and right coronary artery). Patients with a history of myocardial infarction (MI), coronary revascularization or stroke were not included for analysis in this study. All the patients were administered with statins for lipid-lowering effects based on conventional therapy. The primary endpoint was the first occurrence of major cardiovascular events (MI, stroke, heart failure, hospitalization for unstable angina, arterial revascularization, and all-cause death) after enrollment. All study subjects were unrelated ethnic Han Chinese and gave written informed content. The study was approved by the Ethnic Committee of Taizhou People’s Hospital. Three ml of venous blood was drawn for DNA extraction.

Genotyping

A total of 16 SNPs that have been reported to be associated with statin response were selected (Table S1). All SNPs are common genetic variants with minor allele frequency (MAF) ≥0.05 in the Chinese populations in dbSNP. Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood leukocytes using DNA Extraction Kit (Promega, USA) according to the manufacture’s protocol. Genotyping was performed using the ligase detection reaction-polymerase chain reaction (LDR-PCR) method. To evaluate the accuracy of genotyping, 20 samples were randomly selected from the whole study population and re-genotyped using direct sequencing. The LDR-PCR results were 100% concordant with sequencing.

Statistical analyses

All continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation, and categorical data as percentages or absolute numbers unless otherwise indicated. Chi-square test was used to determine whether genotype distribution was in agreement with Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE). Unpaired Student’s T-test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) were performed to compare differences of means between genotypes. The association of SNPs and complications of CAD was examined by odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) estimated using unconditional logistic regression model. Cox proportional hazard regression model was used to calculate hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). The cumulative effect of risk SNPs on EFS was determined by counting the number of unfavorable genotypes each patient carried and using those without any unfavorable genotypes as the reference group. A level of P<0.05 was considered as statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 19.0 (SPSS, IL, USA).

Results

Association of SNPs with complications of CAD

The patient characteristics were summarized in Table 1. During the follow-up, MI occurred in 79 of 785 (10.1%) patients. Two SNPs (rs328 and rs3798220) deviated from HWE and thus were excluded from further analysis. Table 2 showed the results of the association analysis for 14 SNPs and complications of CAD. Both rs2296651 and rs11206510 were significantly related to MI (P<0.05). The A allele of rs2296651 (adjusted OR = 1.753, 95% CI: 1.006-3.055, P = 0.047) and the C allele of rs11206510 (adjusted OR = 2.273, 95% CI: 1.280-4.038, P = 0.005) were associated with an increased risk of MI. Both rs11206510 and rs8192870 showed a weak but statistically significant association with DM (P<0.05). The C allele of rs11206510 (adjusted OR = 1.887, 95% CI: 1.025-3.474, P = 0.042) and the A allele of rs8192870 (adjusted OR = 1.323, 95% CI: 1.004-1.742, P = 0.047) were related to an increased risk of DM. Furthermore, rs1801133 was significantly associated with HP. Patients with the CT and TT genotypes of rs1801133 have a higher risk of HP than those with GG genotype (adjusted OR = 1.898, 95% CI: 1.170-3.078, P = 0.014).

Table 1.

Baseline clinical characteristics of the study patients

| General characteristics | All (n = 785) |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 63.7 ± 10.8 |

| Male, % | 67.4 |

| Non-smokers, % | 51.6 |

| HP, % | 64.3 |

| DM, % | 21.0 |

| SBP, mmHg | 132.9 ± 19.2 |

| DBP, mmHg | 80.2 ± 11.0 |

| TC, mmol/L | 4.7 ± 1.0 |

| TG, mmol/L | 1.8 ± 1.0 |

| HDL-C, mmol/L | 1.2 ± 0.3 |

| LDL-C, mmol/L | 2.8 ± 0.8 |

| ApoA, mg/L | 1.4 ± 0.2 |

| ApoB, mg/L | 0.9 ± 0.2 |

| Lp(a), mg/L | 0.3 ± 0.2 |

| FG, mmol/L | 5.7 ± 2.2 |

SBP, systolic blood pressure. DBP, diastolic blood pressure. TG, triglycerides. TC, total cholesterol. HDL-C, high density lipoprotein cholesterol. MI, myocardial infarction. HP, hypertension. DM, diabetes mellitus. FPG, fasting plasma glucose.

Table 2.

Significant associations between polymorphisms and MI, DM, and HP

| SNP | MI | DM | HP | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| rs13279522 | 0.968 (0.692-1.355) | 0.850 | 1.077 (0.841-1.381) | 0.557 | 0.933 (0.755-1.154) | 0.522 |

| rs708272 | 1.062 (0.756-1.490) | 0.730 | 1.038 (0.810-1.331) | 0.768 | 0.880 (0.711-1.089) | 0.241 |

| rs5882 | 1.089 (0.789-1.503) | 0.604 | 1.093 (0.860-1.389) | 0.467 | 1.091 (0.890-1.337) | 0.401 |

| rs2231142 | 0.816 (0561-1.187) | 0.288 | 1.111 (0.848-1.455) | 0.445 | 0.965 (0.770-1.209) | 0.755 |

| rs4149056 | 1.137 (0.687-1.880) | 0.618 | 0.941 (0.655-1.350) | 0.740 | 1.025 (0.757-1.386) | 0.875 |

| rs2306283 | 1.277 (0.826-1.974) | 0.272 | 0.923 (0.680-1.252) | 0.605 | 1.001 (0.775-1.293) | 0.993 |

| rs2296651 | 1.753 (1.006-3.055) | 0.047 | 0.930 (0.587-1.472) | 0.756 | 0.896 (0.605-1.327) | 0.585 |

| rs693 | 0.978 (0.452-2.116) | 0.956 | 0.523 (0.263-1.039) | 0.064 | 1.073 (0.661-1.741) | 0.776 |

| rs1801133 | 1.374 (0.981-1.926) | 0.065 | 0.980 (0.761-1.262) | 0.875 | 1.318 (1.059-1.640) | 0.014 |

| rs12916 | 0.981 (0.704-1.368) | 0.981 | 0.843 (0.658-1.080) | 0.176 | 1.136 (0.922-1.399) | 0.232 |

| rs688 | 0.866 (0.562-1.335) | 0.515 | 1.170 (0.847-1.615) | 0.341 | 1.103 (0.835-1.457) | 0.492 |

| rs11206510 | 2.273 (1.280-4.038) | 0.005 | 1.887 (1.025-3.474) | 0.042 | 1.319 (0.858-2.027) | 0.206 |

| rs8192870 | 0.998 (0.679-1.466) | 0.991 | 1.323 (1.004-1.742) | 0.047 | 0.993 (0.779-1.265) | 0.954 |

| rs20455 | 0.988 (0.718-1.360) | 0.942 | 0.920 (0.726-1.157) | 0.492 | 1.137 (0.930-1.391) | 0.212 |

Effects of SNPs on HP, FPG, and plasma lipid levels

We also evaluated whether SNPs influenced HP, FPG, and plasma lipid levels. LDL-C lowering by statins was influenced by rs2231142 (Table 3). The C allele of rs2231142 was related to significantly less LDL-C lowering response to statins (P = 0.001). The CC genotype of rs2231142 and the AC genotype of rs8192870 were associated with higher HDL level (P = 0.018 and 0.025, respectively). Patients carrying the AC genotype of rs4149056 and the CT genotype of rs12916 displayed high level of ApoA (P = 0.017) and low level of plasma TG (P = 0.012), respectively. Furthermore, it is interesting that rs1801133 influenced FPG level in CAD patients (P = 0.033).

Table 3.

Significant associations between polymorphisms and HP, FPG, and plasma lipid levels

| SNP | Variable measured | Effect | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| rs8192870 | HDL | AA: 1.1 ± 0.3; AC: 1.2 ± 0.4; CC: 1.1 ± 0.3 | 0.025 |

| rs4149056 | ApoA | CC: 1.2 ± 0.2; AC: 1.4 ± 0.2; TT: 1.3 ± 0.2 | 0.017 |

| rs12916 | TG | CC: 1.9 ± 0.9; CT: 1.7 ± 0.9; TT: 1.9 ± 1.2 | 0.012 |

| rs1801133 | FPG | CC: 1.2 ± 0.2; AC: 1.4 ± 0.2; TT: 1.3 ± 0.6 | 0.033 |

| rs2231142 | HDL | AA: 1.1 ± 0.3; AC: 1.1 ± 0.3; CC: 1.2 ± 0.4 | 0.018 |

| LDL | AA: 2.4 ± 0.7; AC: 2.8 ± 0.9; CC: 2.8 ± 0.8 | 0.001 |

Effects of SNPs on event-free survival (EFS)

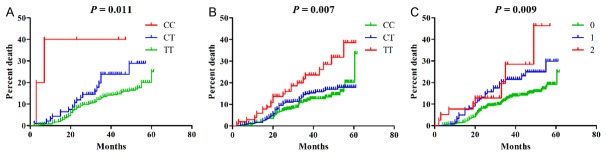

We then assessed whether any of 14 SNPs were associated with EFS. Both rs11206510 (HR = 1.792, 95% CI: 1.146-2.802, P = 0.010) and rs1801133 (HR = 1.402, 95% CI: 1.083-1.815, P = 0.010) were associated with an increased risk of major cardiovascular events in CAD patients treated with statins (Figure 1). These effects remained significant even after adjusted for age, sex, DM, MI, SBP, DBP, TC, TG, HDL-C, LDL-C and FPG (rs11206510, HR = 1.891, 95% CI: 1.188-3.010, P = 0.007; rs1801133, HR = 1.499, 95% CI: 1.141-1.971, P = 0.004) (Table 4).

Figure 1.

Cumulative hazard curves for EFS by genotypes. A. rs11206510. B. rs1801133. C. Cumulative effect of unfavorable genotypes of rs11206510 and rs1801133 on OS.

Table 4.

Associations between SNPs and event-free survival of CAD patients

| SNP | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | |

| rs13279522 | 0.958 (0.741-1.238) | 0.742 | 0.873 (0.662-1.152) | 0.336 |

| rs708272 | 0.877 (0.679-1.133) | 0.316 | 0.806 (0.621-1.047) | 0.106 |

| rs5882 | 1.075 (0.839-1.376) | 0.568 | 1.019 (0.784-1.325) | 0.887 |

| rs2231142 | 0.829 (0.622-1.105) | 0.201 | 0.895 (0.656-1.220) | 0.482 |

| rs4149056 | 1.064 (0.730-1.552) | 0.746 | 1.052 (0.711-1.554) | 0.804 |

| rs2306283 | 1.106 (0.800-1.530 | 0.541 | 1.124 (0.794-1.590) | 0.510 |

| rs2296651 | 1.359 (0.875-2.110) | 0.172 | 1.5189 (0.948-2.431) | 0.082 |

| rs693 | 1.123 (0.604-2.087) | 0.714 | 1.140 (0.607-2.143) | 0.684 |

| rs1801133 | 1.402 (1.083-1.815) | 0.010 | 1.499 (1.141-1.971) | 0.004 |

| rs12916 | 1.012 (0.784-1.306) | 0.928 | 1.060 (0.812-1.383) | 0.667 |

| rs688 | 0.890 (0.639-1.240) | 0.491 | 0.844 (0.596-1.197) | 0.342 |

| rs11206510 | 1.792 (1.146-2.802) | 0.010 | 1.891 (1.188-3.010) | 0.007 |

| rs8192870 | 0.941 (0.702-1.261) | 0.683 | 0.952 (0.695-1.304) | 0.759 |

| rs20455 | 1.044 (0.817-1.334) | 0.733 | 1.056 (0.818-1.363) | 0.678 |

We further investigated the cumulative effects of rs11206510 and rs1801133 on EFS. The unfavorable genotypes were defined as CC and CT genotypes for rs11206510 and TT genotype for rs1801133. Cox regression analysis revealed a multivariable-adjusted HR of 1.810 (95% CI: 1.179-2.802, P = 0.007) for major cardiovascular events in patients carried with 1 risk genotype. Although patients with 2 risk genotypes had the highest risk of major cardiovascular events, the different disappeared after adjusted for age, sex, DM, MI, SBP, DBP, TC, TG, HDL, LDL and FPG (adjusted HR = 3.172, 95% CI: 0.963-10.448, P = 0.058).

Discussion

Recent studies have revealed that the individual difference in statins response is a result of both genetic and environmental factors [7-13]. Genetic variants in genes encoding enzymes and proteins involved in drug metabolism and transport, and drug target proteins were the primary genetic determinants influencing the lipid-lowering effects of statins on individual patients [14,15]. In this study, we examined whether 16 established genetic variants for statins response predispose to major cardiovascular events in CAD patients receiving statins. We found that both rs11206510 and rs1801133 showed an increased risk of developing major cardiovascular events, and exhibited cumulative effect on EFS.

Dyslipidemia involves multiple regulatory pathways. HMGCR catalyzes the conversion of HMG-CoA to mevalonate, a key intermediate for catalyzing cholesterol biosynthesis, which affects cholesterol level in the body [16]. Statins, extensively used agents for lipid-lowering in clinical practice, are also known as HMGCR inhibitors. HMGCR inhibitors are clinically proven to reduce plasma levels of TC, TG, LDL, and VLDL and increase plasma HDL. The rs12916 is located at the 3’UTR of HMGCR, and its T allele is associated with low HMGCR expression in the liver [17]. The lipid-lowering effects of statins on patients carrying CC genotype are poorer than those carrying CT and TT genotypes [18], indicated that HMGCR expression mediate LDL-C signals. In the present study, rs12916 was not related to LDL-C level, but affected TG level. rs8192870, located in the first intron of the cytochrome P450, family 7, subfamily A, polypeptide 1 (CYP7A1) gene, is associated with the progression of primary biliary cirrhosis [19]. Our study also showed that the risk for DM dramatically increased in CAD patients carrying the AA genotype of rs8192870. CYP7A1 is a rate-limiting enzyme for bile acid synthesis from cholesterol, which can influence the cholesterol content in hepatocytes, as well as the efficacy of statins. Jiang et al. [20] found that rs8192870 was associated with LDL-C response to atorvastatin treatment. The lipid-lowering effects on individuals carrying the AA genotype of rs8192870 are the most apparent following atorvastatin treatment. However, in this study, we found that rs8192870 was not related to LDL-C level but associated with HDL level. This phenomenon occurred probably because LDL-C levels in this study were measured after the administration of statins in an inconsistent duration.

Although drug metabolic enzymes are considered important determinants for statins disposition, the effects of drug transporters on the disposition and efficacy of statins are more crucial [21,22]. Solute carrier organic anion transporter family, member 1B1 (SLCO1B1) is predominantly expressed on the basolateral membrane of human hepatocytes, by which hepatocytes uptake various endogenous substances and drugs such as statins and methotrexate from the portal system, and then metabolize and eliminate them [8,23,24]. Therefore, SLCO1B1 significantly influenced the distribution of drugs in the body, and changes in its activity will increase the toxicity and side effects of various drugs, including statins and methotrexate [25,26]. The rs4149056 leads to a change of valine to alanine at codon 174 and a reduced transport function of SLCO1B1 [27,28], and is associated with side effects of statins and methotrexate [29,30]. In the present study, we found that rs4149056 was associated with plasma ApoA level. Given that statins can elevate the level of ApoA [31], SLCO1B1 variants may influence the regulatory effects of statins on ApoA. Further study is warranted to validate this results. ATP-binding cassette sub-family G member 2 (ABCG2) is a P-glycoprotein that transports exogenous substances out of the cells. rs2231142, causing a reduced transport function of ABCG2, is not only associated with the susceptibility of complex diseases, but also markedly affects the pharmacokinetics of drugs such as statins and methotrexate [21,22,26,32,33]. The AA genotype of rs2231142 elevates the systemic exposure of statins and increases the lipid-lowering effects [7,34]. Our findings confirmed that rs2231142 is significantly correlated with the levels of HDL and LDL, and indirectly proved that rs2231142 affects the metabolism of statins.

Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) regulates LDLR level in the liver through post-transcriptional mechanism [35]. Overexpression of PCSK9 leads to reduced LDLR level in the liver, which further decreases the LDLR-mediated LDL-C intake and thereby affects cholesterol level, as well as increases plasma LDL-C level [35-37]. Evolocumab, a monoclonal antibody to PCSK9, can effectively lower plasma LDL-C in patients with statin intolerance [38]. In 2008, Cristen et al. [39] first reported that rs11206510, located 20 kb upstream of PCSK9, was associated with blood lipid levels and CAD. Recent study has shown that rs11206510 is related to increased MI risk in patients with vascular diseases following additional administration with statins, but not in those who have never been administrated with statins [40]. In the present study, rs11206510 was associated with not only DM risk but also an increased risk of major cardiovascular events of CAD patients receiving statins. These findings indicate that rs11206510 is an independent prognostic factor for CAD patients after long-term statin administration.

Elevated homocysteine level contributes to oxidative stress and thus causes endothelial dysfunction, and is considered to be a risk factor for cardiovascular disease [41]. The T allele of rs1801133 may reduce the enzyme activity of methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) and increase plasma homocysteine level [42,43], and thus is closely associated with increased risks of many diseases, including cardiovascular diseases [44,45]. However, differences exist in the relationship between rs1801133 and CAD [42,44], which require further verification. Furthermore, the CC genotype of rs1801133 has been reported to reduce the risk for CAD in individuals receiving lipid-lowering treatment [41]. In this study, we found that the TT genotype of rs1801133 was an independent factor for CAD patients treated with statins, which may be caused by high homocysteine because TT genotype carriers have higher homocysteine levels in patients on statin treatment [46].

In conclusion, our findings provide evidence that genetic variants are not only associated with complications of CAD, but also influence the prognosis in CAD patients treated with statins. Given that genetic heterogeneity, there is also a need to confirm our findings by further large-scale studies. In the future, genetic variants may exert their potential as a biomarker to guide the administration of statins to CAD patients, which will provide an enhanced scientific basis for CAD treatment.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Taizhou Society Development Project, Jiangsu, China (grant No. TS201532). The 333 project of scientific research project Foundation, Jiangsu, China (grant No. BRA2015224). The peak of Six Talents Project Foundation, Jiangsu, China (grant No. WSW-148).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet. 2015;385:117–171. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whayne TF Jr. Problems and possible solutions for therapy with statins. Int J Angiol. 2013;22:75–82. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1343358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Catapano AL, Farnier M, Foody JM, Toth PP, Tomassini JE, Brudi P, Tershakovec AM. Combination therapy in dyslipidemia: where are we now? Atherosclerosis. 2014;237:319–335. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen W, Zheng R, Zeng H, Zhang S, He J. Annual report on status of cancer in China, 2011. Chin J Cancer Res. 2015;27:2–12. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.1000-9604.2015.01.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van der Valk FM, Bernelot Moens SJ, Verweij SL, Strang AC, Nederveen AJ, Verberne HJ, Nurmohamed MT, Baeten DL, Stroes ES. Increased arterial wall inflammation in patients with ankylosing spondylitis is reduced by statin therapy. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:1848–51. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma W, Shen D, Liu J, Pan J, Yu L, Shi W, Deng L, Zhu L, Yang F, Liu J, Cai W, Yang J, Luo Y, Cui H, Liu S. Statin function as an anti-inflammation therapy for depression in patients with coronary artery disease by downregulating interleukin-1beta. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2016;67:129–135. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0000000000000323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee HK, Hu M, Lui S, Ho CS, Wong CK, Tomlinson B. Effects of polymorphisms in ABCG2, SLCO1B1, SLC10A1 and CYP2C9/19 on plasma concentrations of rosuvastatin and lipid response in Chinese patients. Pharmacogenomics. 2013;14:1283–1294. doi: 10.2217/pgs.13.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meyer zu Schwabedissen HE, Albers M, Baumeister SE, Rimmbach C, Nauck M, Wallaschofski H, Siegmund W, Volzke H, Kroemer HK. Function-impairing polymorphisms of the hepatic uptake transporter SLCO1B1 modify the therapeutic efficacy of statins in a population-based cohort. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2015;25:8–18. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0000000000000098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li Q, Hong J, Wu J, Huang ZX, Li QJ, Yin RX, Lin QZ, Wang F. The role of common variants of ABCB1 and CYP7A1 genes in serum lipid levels and lipid-lowering efficacy of statin treatment: a meta-analysis. J Clin Lipidol. 2014;8:618–629. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2014.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Birmingham BK, Bujac SR, Elsby R, Azumaya CT, Wei C, Chen Y, Mosqueda-Garcia R, Ambrose HJ. Impact of ABCG2 and SLCO1B1 polymorphisms on pharmacokinetics of rosuvastatin, atorvastatin and simvastatin acid in Caucasian and Asian subjects: a class effect? Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;71:341–355. doi: 10.1007/s00228-014-1801-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miltiadous G, Xenophontos S, Bairaktari E, Ganotakis M, Cariolou M, Elisaf M. Genetic and environmental factors affecting the response to statin therapy in patients with molecularly defined familial hypercholesterolaemia. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2005;15:219–225. doi: 10.1097/01213011-200504000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ma Q, Lu AY. Pharmacogenetics, pharmacogenomics, and individualized medicine. Pharmacol Rev. 2011;63:437–459. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.003533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodrigues AC, Sobrino B, Genvigir FD, Willrich MA, Arazi SS, Dorea EL, Bernik MM, Bertolami M, Faludi AA, Brion MJ, Carracedo A, Hirata MH, Hirata RD. Genetic variants in genes related to lipid metabolism and atherosclerosis, dyslipidemia and atorvastatin response. Clin Chim Acta. 2013;417:8–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2012.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmitz G, Schmitz-Madry A, Ugocsai P. Pharmacogenetics and pharmacogenomics of cholesterol-lowering therapy. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2007;18:164–173. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e3280555083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rodrigues AC, Hirata MH, Hirata RD. The genetic determinants of atorvastatin response. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2007;9:545–553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Endo A. The discovery and development of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors. 1992. Atheroscler Suppl. 2004;5:67–80. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosissup.2004.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Swerdlow DI, Preiss D, Kuchenbaecker KB, Holmes MV, Engmann JE, Shah T, Sofat R, Stender S, Johnson PC, Scott RA, Leusink M, Verweij N, Sharp SJ, Guo Y, Giambartolomei C, Chung C, Peasey A, Amuzu A, Li K, Palmen J, Howard P, Cooper JA, Drenos F, Li YR, Lowe G, Gallacher J, Stewart MC, Tzoulaki I, Buxbaum SG, van der AD, Forouhi NG, Onland-Moret NC, van der Schouw YT, Schnabel RB, Hubacek JA, Kubinova R, Baceviciene M, Tamosiunas A, Pajak A, Topor-Madry R, Stepaniak U, Malyutina S, Baldassarre D, Sennblad B, Tremoli E, de Faire U, Veglia F, Ford I, Jukema JW, Westendorp RG, de Borst GJ, de Jong PA, Algra A, Spiering W, Maitland-van der Zee AH, Klungel OH, de Boer A, Doevendans PA, Eaton CB, Robinson JG, Duggan D, Consortium D, Consortium M, InterAct C, Kjekshus J, Downs JR, Gotto AM, Keech AC, Marchioli R, Tognoni G, Sever PS, Poulter NR, Waters DD, Pedersen TR, Amarenco P, Nakamura H, McMurray JJ, Lewsey JD, Chasman DI, Ridker PM, Maggioni AP, Tavazzi L, Ray KK, Seshasai SR, Manson JE, Price JF, Whincup PH, Morris RW, Lawlor DA, Smith GD, Ben-Shlomo Y, Schreiner PJ, Fornage M, Siscovick DS, Cushman M, Kumari M, Wareham NJ, Verschuren WM, Redline S, Patel SR, Whittaker JC, Hamsten A, Delaney JA, Dale C, Gaunt TR, Wong A, Kuh D, Hardy R, Kathiresan S, Castillo BA, van der Harst P, Brunner EJ, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Marmot MG, Krauss RM, Tsai M, Coresh J, Hoogeveen RC, Psaty BM, Lange LA, Hakonarson H, Dudbridge F, Humphries SE, Talmud PJ, Kivimaki M, Timpson NJ, Langenberg C, Asselbergs FW, Voevoda M, Bobak M, Pikhart H, Wilson JG, Reiner AP, Keating BJ, Hingorani AD, Sattar N. HMG-coenzyme A reductase inhibition, type 2 diabetes, and bodyweight: evidence from genetic analysis and randomised trials. Lancet. 2015;385:351–361. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61183-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chien KL, Wang KC, Chen YC, Chao CL, Hsu HC, Chen MF, Chen WJ. Common sequence variants in pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic pathway-related genes conferring LDL cholesterol response to statins. Pharmacogenomics. 2010;11:309–317. doi: 10.2217/pgs.09.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inamine T, Higa S, Noguchi F, Kondo S, Omagari K, Yatsuhashi H, Tsukamoto K, Nakamura M. Association of genes involved in bile acid synthesis with the progression of primary biliary cirrhosis in Japanese patients. J Gastroenterol. 2013;48:1160–1170. doi: 10.1007/s00535-012-0730-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang XY, Zhang Q, Chen P, Li SY, Zhang NN, Chen XD, Wang GC, Wang HB, Zhuang MQ, Lu M. CYP7A1 polymorphism influences the LDL cholesterol-lowering response to atorvastatin. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2012;37:719–723. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2012.01372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Niemi M. Transporter pharmacogenetics and statin toxicity. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;87:130–133. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2009.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DeGorter MK, Xia CQ, Yang JJ, Kim RB. Drug transporters in drug efficacy and toxicity. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2012;52:249–273. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010611-134529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Konig J, Cui Y, Nies AT, Keppler D. A novel human organic anion transporting polypeptide localized to the basolateral hepatocyte membrane. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2000;278:G156–164. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2000.278.1.G156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pasanen MK, Miettinen TA, Gylling H, Neuvonen PJ, Niemi M. Polymorphism of the hepatic influx transporter organic anion transporting polypeptide 1B1 is associated with increased cholesterol synthesis rate. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2008;18:921–926. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e32830c1b5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilke RA, Ramsey LB, Johnson SG, Maxwell WD, McLeod HL, Voora D, Krauss RM, Roden DM, Feng Q, Cooper-Dehoff RM, Gong L, Klein TE, Wadelius M, Niemi M Clinical Pharmacogenomics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) The clinical pharmacogenomics implementation consortium: CPIC guideline for SLCO1B1 and simvastatin-induced myopathy. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;92:112–117. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2012.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lima A, Bernardes M, Azevedo R, Monteiro J, Sousa H, Medeiros R, Seabra V. SLC19A1, SLC46A1 and SLCO1B1 polymorphisms as predictors of methotrexate-related toxicity in Portuguese rheumatoid arthritis patients. Toxicol Sci. 2014;142:196–209. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfu162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choi JH, Lee MG, Cho JY, Lee JE, Kim KH, Park K. Influence of OATP1B1 genotype on the pharmacokinetics of rosuvastatin in Koreans. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;83:251–257. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pasanen MK, Fredrikson H, Neuvonen PJ, Niemi M. Different effects of SLCO1B1 polymorphism on the pharmacokinetics of atorvastatin and rosuvastatin. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2007;82:726–733. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Group SC, Link E, Parish S, Armitage J, Bowman L, Heath S, Matsuda F, Gut I, Lathrop M, Collins R. SLCO1B1 variants and statin-induced myopathy--a genomewide study. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:789–799. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trevino LR, Shimasaki N, Yang W, Panetta JC, Cheng C, Pei D, Chan D, Sparreboom A, Giacomini KM, Pui CH, Evans WE, Relling MV. Germline genetic variation in an organic anion transporter polypeptide associated with methotrexate pharmacokinetics and clinical effects. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009;27:5972–5978. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.4156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mora S, Glynn RJ, Ridker PM. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol, size, particle number, and residual vascular risk after potent statin therapy. Circulation. 2013;128:1189–1197. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.002671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feher A, Juhasz A, Laszlo A, Pakaski M, Kalman J, Janka Z. Association between the ABCG2 C421A polymorphism and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci Lett. 2013;550:51–54. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2013.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang L, Spencer KL, Voruganti VS, Jorgensen NW, Fornage M, Best LG, Brown-Gentry KD, Cole SA, Crawford DC, Deelman E, Franceschini N, Gaffo AL, Glenn KR, Heiss G, Jenny NS, Kottgen A, Li Q, Liu K, Matise TC, North KE, Umans JG, Kao WH. Association of functional polymorphism rs2231142 (Q141K) in the ABCG2 gene with serum uric acid and gout in 4 US populations: the PAGE study. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177:923–932. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tomlinson B, Hu M, Lee VW, Lui SS, Chu TT, Poon EW, Ko GT, Baum L, Tam LS, Li EK. ABCG2 polymorphism is associated with the low-density lipoprotein cholesterol response to rosuvastatin. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;87:558–562. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2009.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park SW, Moon YA, Horton JD. Post-transcriptional regulation of low density lipoprotein receptor protein by proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9a in mouse liver. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:50630–50638. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410077200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Filardi PP, Paolillo S, Trimarco B. Lipid control in high-risk patients: focus on PCSK9 inhibitors. G Ital Cardiol (Rome) 2015;16:44–51. doi: 10.1714/1776.19250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jelassi A, Slimani A, Jguirim I, Najah M, Maatouk F, Varret M, Slimane MN. Effect of a splice site mutation in LDLR gene and two variations in PCSK9 gene in Tunisian families with familial hypercholesterolaemia. Ann Clin Biochem. 2011;48:83–86. doi: 10.1258/acb.2010.010087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stroes E, Colquhoun D, Sullivan D, Civeira F, Rosenson RS, Watts GF, Bruckert E, Cho L, Dent R, Knusel B, Xue A, Scott R, Wasserman SM, Rocco M GAUSS-2 Investigators. Anti-PCSK9 antibody effectively lowers cholesterol in patients with statin intolerance: the GAUSS-2 randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 clinical trial of evolocumab. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:2541–2548. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Willer CJ, Sanna S, Jackson AU, Scuteri A, Bonnycastle LL, Clarke R, Heath SC, Timpson NJ, Najjar SS, Stringham HM, Strait J, Duren WL, Maschio A, Busonero F, Mulas A, Albai G, Swift AJ, Morken MA, Narisu N, Bennett D, Parish S, Shen H, Galan P, Meneton P, Hercberg S, Zelenika D, Chen WM, Li Y, Scott LJ, Scheet PA, Sundvall J, Watanabe RM, Nagaraja R, Ebrahim S, Lawlor DA, Ben-Shlomo Y, Davey-Smith G, Shuldiner AR, Collins R, Bergman RN, Uda M, Tuomilehto J, Cao A, Collins FS, Lakatta E, Lathrop GM, Boehnke M, Schlessinger D, Mohlke KL, Abecasis GR. Newly identified loci that influence lipid concentrations and risk of coronary artery disease. Nat Genet. 2008;40:161–169. doi: 10.1038/ng.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van de Woestijne AP, van der Graaf Y, de Bakker PI, Asselbergs FW, de Borst GJ, Algra A, Spiering W, Visseren FL SMART Study Group. LDL-c-linked SNPs are associated with LDL-c and myocardial infarction despite lipid-lowering therapy in patients with established vascular disease. Eur J Clin Invest. 2014;44:184–191. doi: 10.1111/eci.12206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maitland-van der Zee AH, Lynch A, Boerwinkle E, Arnett DK, Davis BR, Leiendecker-Foster C, Ford CE, Eckfeldt JH. Interactions between the single nucleotide polymorphisms in the homocysteine pathway (MTHFR 677C>T, MTHFR 1298A>C, and CBSins) and the efficacy of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors in preventing cardiovascular disease in high-risk patients of hypertension: the GenHAT study. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2008;18:651–656. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e3282fe1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van Meurs JB, Pare G, Schwartz SM, Hazra A, Tanaka T, Vermeulen SH, Cotlarciuc I, Yuan X, Malarstig A, Bandinelli S, Bis JC, Blom H, Brown MJ, Chen C, Chen YD, Clarke RJ, Dehghan A, Erdmann J, Ferrucci L, Hamsten A, Hofman A, Hunter DJ, Goel A, Johnson AD, Kathiresan S, Kampman E, Kiel DP, Kiemeney LA, Chambers JC, Kraft P, Lindemans J, McKnight B, Nelson CP, O’Donnell CJ, Psaty BM, Ridker PM, Rivadeneira F, Rose LM, Seedorf U, Siscovick DS, Schunkert H, Selhub J, Ueland PM, Vollenweider P, Waeber G, Waterworth DM, Watkins H, Witteman JC, den Heijer M, Jacques P, Uitterlinden AG, Kooner JS, Rader DJ, Reilly MP, Mooser V, Chasman DI, Samani NJ, Ahmadi KR. Common genetic loci influencing plasma homocysteine concentrations and their effect on risk of coronary artery disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98:668–676. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.044545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pare G, Chasman DI, Parker AN, Zee RR, Malarstig A, Seedorf U, Collins R, Watkins H, Hamsten A, Miletich JP, Ridker PM. Novel associations of CPS1, MUT, NOX4, and DPEP1 with plasma homocysteine in a healthy population: a genome-wide evaluation of 13 974 participants in the women’s genome health study. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2009;2:142–150. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.108.829804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen W, Hua K, Gu H, Zhang J, Wang L. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase C667T polymorphism is associated with increased risk of coronary artery disease in a Chinese population. Scand J Immunol. 2014;80:346–353. doi: 10.1111/sji.12215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li P, Qin C. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) gene polymorphisms and susceptibility to ischemic stroke: a meta-analysis. Gene. 2014;535:359–364. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.09.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jiang S, Chen Q, Venners SA, Zhong G, Hsu YH, Xing H, Wang X, Xu X. Effect of simvastatin on plasma homocysteine levels and its modification by MTHFR C677T polymorphism in Chinese patients with primary hyperlipidemia. Cardiovasc Ther. 2013;31:e27–33. doi: 10.1111/1755-5922.12002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.