Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most common malignancies that results from genes regulation via different pathways. NME/NM23 nucleoside diphosphate kinase 1 (NME1) is generally regarded as a metastasis suppressor, but its function in HCC is largely unknown. In our study, we explored the role of NME1 in HCC. By analyzing the gene expression omnibus (GEO) database, we discovered that NME1 was more highly expressed in HCC tumor tissues than non-HCC liver tissues (P < 0.001), and NME1 was significantly up-regulated in HCC tumor tissues than in adjacent normal tissues (P < 0.001). Then, validated by the enrolled HCC patients and The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database, NME1 was upregulated in HCC tumor tissues compared with matched adjacent normal tissue (P < 0.05). Besides, NME1 was down-regulated in Stage III/IV HCC patients than Stage I/II HCC patients (P = 0.009). Moreover, Kaplan-Meier analysis showed that HCC patients with high NME1 expression had poor overall survival (P = 0.004) and higher recurrence rate (P < 0.001). Our data revealed that NME1 was a special oncogene, and its expression was significantly associated with the progression and prognosis of HCC. NME1 may be a novel molecular biomarker for the targeted therapy and prognosis of HCC.

Keywords: NME1, hepatocellular carcinoma, prognosis

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the fifth most common cancer in men and the ninth in women [1,2]. In 2012, there was more than 780000 incident cases diagnosed, and half of new cases were occurred in China. There was nearly 740000 deaths caused by liver cancer and HCC had become the second mortal cause in all cancers worldwide [3]. HCC occurrence depends on a complex interplay of genetic predisposition factors, environmental factors, exposure to carcinogens and virus [4]. Recent studies considered that several single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were associated with HCC [5]. These SNPs regulated many biologic pathways of carcinogenesis, including inflammation through TNFA and IL1B [6,7]; oxidative stress via SOD2 [8]; cell cycle via MDM2 and TP53 [9,10] and growth factor with EGF [11]. Genes modulate HCC developing via many pathways, for example, high levels VEGFA and CCND1 are observed in HCC patients [12], EGFR and Ras signaling is activated in more than 50% HCC [12]; meanwhile, tumor suppressor PTEN is inactivated and disrupted mTOR pathway in disease developing [13]. Besides, Wnt signaling was active in a third of hepatocellular carcinomas with transcription factor β catenin or inactivation of E-cadherin [14].

NME1, also known as NM23-H1 and NDPK-A, is generally regarded as a metastasis suppressor, and its expression is found associated with the metastatic potential of various neoplasms. Previous studies demonstrated that NME1 had significant metastasis suppressing function, and the expression of NME1 inversely related to metastatic behavior in experimental animals [15]. Besides, mice lacking NME1 protein were twice as prone to develop lung metastases compared with wild-type controls [16]. Tokunaga discovered that reduced expression of NME1 protein was concordant with the frequency of lymph-node metastasis in human breast cancer [17]. Whereas, in neuroblastoma the elevated NME1 protein expression is correlated to poor survival [18], which is different from its metastasis suppressing function in other cancers. In colorectal cancer, Lindmark demonstrated that NME1 is not useful as predictor of metastatic potential of colorectal cancer [19]; reversely, Martinez and his colleagues regard NME1 as a prognostic factor in human colorectal carcinoma, and NME1 was overexpressed in tumors compared with adjacent mucosa and NME1 overexpression lost in advanced tumor stages [20]. Previous studies demonstrated that elevated NME1 expression group had a higher incidence of distant metastasis and a lower 2-year disease-free survival rate than the non-elevated group in gastric cancer [21,22]. The result was not consistent with the previous assumption that NME1 is an anti-metastatic gene for gastric cancer [23]. Above all, NME1 function in different cancers did not draw a consistent conclusion and rarely study concentrated on NME1 function in HCC patients. In HCC, NME1 acts as a tumor promotor or a tumor suppressor is still obscure, which need to be further study. Here, we explored the correlation between NME1 expression, tumor pathology, and tumor prognosis to better understand the NME1 function in HCC progress.

Materials and methods

Patients

A total of 72 HCC patients [56 males and 16 females, mean (SD) age 55.3 (11.6) years] were enrolled in this study between December 2014 and August 2016 at the Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University. Informed consent was obtained from each participant, and the ethics committee of Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University, approved the study. All patients were confirmed as HCC by operation and pathology.

438 liver hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients with clinical data in the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA, http://cancergenome.nih.gov/) was download from the NCI Cancer Genomics Hub [24]. The gene expression, tumor pathology, overall survival, recurrence and other demographic characteristics of patients were obtained from database.

RNA extraction and real-time PCR

Total RNA of specimens was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Quantification of isolated RNA was performed by NanoDrop ND-2000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, USA). Then, the cDNA was synthesized from total RNA by ReverTra Ace qPCR RT Master Mix with gDNA Remover kit (Toyobo, Japan). The primer sequences used in this study was showed in follow: NME1 forward primer: 5’- AAGGAGATCGGCTTGTGGTTT-3’, reverse primer: 5’-CTGAGCACAGCTCGTGTAATC-3’; β-Actin forward primer: 5’-CCTGGCACCCAGCACAAT-3’, reverse primer: 5’-GGGCCGGACTCGT CATACT-3’; GAPDH forward primer: 5’-ATGACATCAAGAAGGTGGTG-3’, reverse primer: 5’-CATACCAGGAAATGA GCTTG-3’. β-Actin and GAPDH were used as internal controls.

Bioinformatics analysis

Gene expression profiling datasets were obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (accession numbers: GSE10143, GSE62232, GSE36376 and GSE45436).

Gene expression data and clinical data of 438 HCC patients in TCGA database was download from the NCI Cancer Genomics Hub (CGHub).

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed by SPSS version 19.0. Normally distributed data were presented as mean (SE) and analyzed by Student’s t test; abnormally distributed data were presented as median (interquartile range) and was analyzed by Mann-Whiney U test. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was performed. All statistical tests were 2-sided, and the level of statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Patients’ characteristics

Among the enrolled HCC patients in this study, the mean age of 72 HCC patients was 55.3 years, and the male: female ratio was 56:16. In enrolled HCC patients, 37 cases had stage I disease, 14 cases had stage II disease, 20 cases had stage III disease and 1 case had stage IV disease based on the tumor-nodes-metastasis (TNM) staging system. Of 72 HCC patients, 65 patients had Child-Pugh A liver function, 7 patients had Child-Pugh B liver function and no patients had Child-Pugh C liver function.

In TCGA database, the mean age of 438 HCC patients was 60.3 years, and the male: female ratio was 292:146. Of 438 HCC samples, 59 samples were derived from adjacent normal tissues, 377 samples were derived from primary tumor tissues and 2 samples were derived from recurrence tumor tissues. Among them, 198 cases were TNM I disease, 100 cases were TNM II disease, 100 cases were TNM III disease, 6 cases were TNM IV disease and TNM stage of rest 34 cases were not given. Of 438 HCC samples, 253 patients had Child-Pugh A liver function, 30 patients had Child-Pugh B liver function, 2 patients had Child-Pugh C liver function and the rest 153 patients were unknown. Patients demographic and clinicopathological information is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of studied HCC patients

| Baseline varaibles | Enrolled HCC patients (n = 72) | HCC patients in TCGA database (n = 438) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years (mean; SD) | 55.3±11.6 | 60.3±13.7** |

| Males/Females, n (%) | 56 (77.8)/16 (22.2) | 292 (66.7)/146 (33.3) |

| Sample type, n (%) | ||

| Adjacent normal tissues | 72 (50) | 59 (13.5)*** |

| Primary tumor tissues | 72 (50) | 377 (86.1)*** |

| Recurrent tumor tissues | 0 (0) | 2 (0.04) |

| TNM staging, n (%) | ||

| I | 37 (51.4) | 198 (45.2) |

| II | 14 (19.4) | 100 (22.8) |

| III | 20 (27.8) | 100 (22.8) |

| IV | 1 (1.4%) | 6 (1.4) |

| NA | 0 (0%) | 34 (7.8)* |

| Child-Pugh classification, n (%) | ||

| A | 65 (90.3) | 253 (57.8)*** |

| B | 7 (9.7) | 30 (6.8) |

| C | 0 (0) | 2 (0.5) |

| NA | 0 (0) | 153 (34.9)*** |

p values of normally distributed data were derived from unpaired Student’s t test. Difference between two groups were tested using the Chi-Square test for proportions and unpaired Student’s t test for continuous variables.

P < 0.05;

P < 0.01;

P < 0.001.

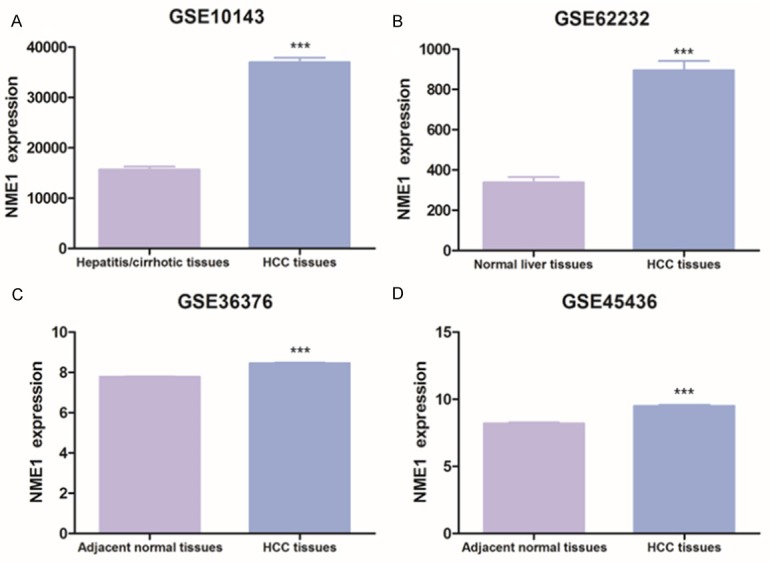

NME1 expression in human expression profiling array

To explore the NME1 function in liver cancer, we downloaded four human expression profiling databases (GSE10143, GSE62232, GSE36376 and GSE45436) and analyzed NME1 function in HCC patients. For GSE10143 database, NME1 expression of HCC patients tissues (n = 80) was 2.36 fold higher than NME1 expression of hepatitis/cirrhotic patients tissues (n = 307) (P < 0.001, Figure 1A). Besides, the si-milar phenomenon was observed in GSE62232, NME1 expression of HCC patients tissues (n = 81) was 2.65 fold higher than NME1 expression of normal liver tissues (n = 10) (P < 0.001, Figure 1B). What is more, we discovered that NME1 was up-regulated in HCC tumor tissues (n = 240) compared with adjacent normal tissues (n = 193) in GSE36376 database (P < 0.001, Figure 1C). Meanwhile, GSE45436 showed that NME1 was evaluated in HCC tumor tissues (n = 95) compared with adjacent normal tissue (n = 39) as well (P < 0.001, Figure 1D). These databases demonstrated that NME1 was up-regulated in tumor tissues compared with adjacent normal tissues or normal/hepatitis/cirrhotic liver tissues.

Figure 1.

The NME1 expression in human expression profiling array. A. GSE10143, hepatitis/cirrhotic liver tissues (n = 307) vs HCC tumor tissues (n = 80). B. GSE62232, normal liver tissues (n = 10) vs HCC tumor tissues (n = 81). C. GSE36376, adjacent normal tissues (n = 193) vs HCC tumor tissues (n = 240). D. GSE45436, adjacent normal tissues (n = 39) vs HCC tumor tissues (n = 95). Data are shown as mean (SE). ***P < 0.001.

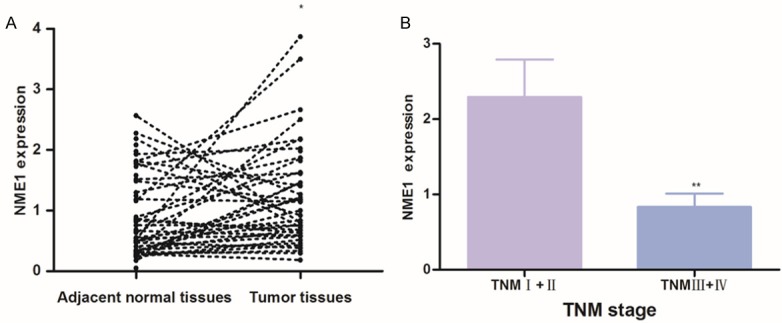

NME1 involved in HCC tumors progression

To verify the results of GEO databases, we detected NME1 expression in enrolled HCC tissues by qPCR and compared NME1 expression in tumor tissues and paired adjacent normal tissues. As expected, compared with matching adjacent normal tissues, NME1 was up-regulated in tumor tissues. As shown in Figure 2A, the NME1 was evaluated in tumor than adjacent normal tissues (P = 0.021, Figure 2A), which is in accordance with the results of GSE36376 and GSE45436, showed that NME1 was evaluated in tumor tissues. Then, we evaluated NME1 expression in HCC progression, and discovered that NME1 expression in Stage III/IV HCC patients was significantly lower than in Stage I/II HCC patients (P = 0.009, Figure 2B). However, no significant association was found between NME1 expression in HCC and other parameters, such as liver cirrhosis, size of tumor and Child-Pugh classification. Overall, our result demonstrated NME1 involve in HCC tumor oncogenesis progression.

Figure 2.

Expression of NME1 were verified by real-time qPCR in enrolled HCC patients. A. Paired adjacent normal tissues (n = 72) vs HCC tumor tissues (n = 72); B. NME1 expression in HCC tissues at I/II (n = 51) and III/IV (n = 21) clinical stages. Results are shown as mean (SE). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

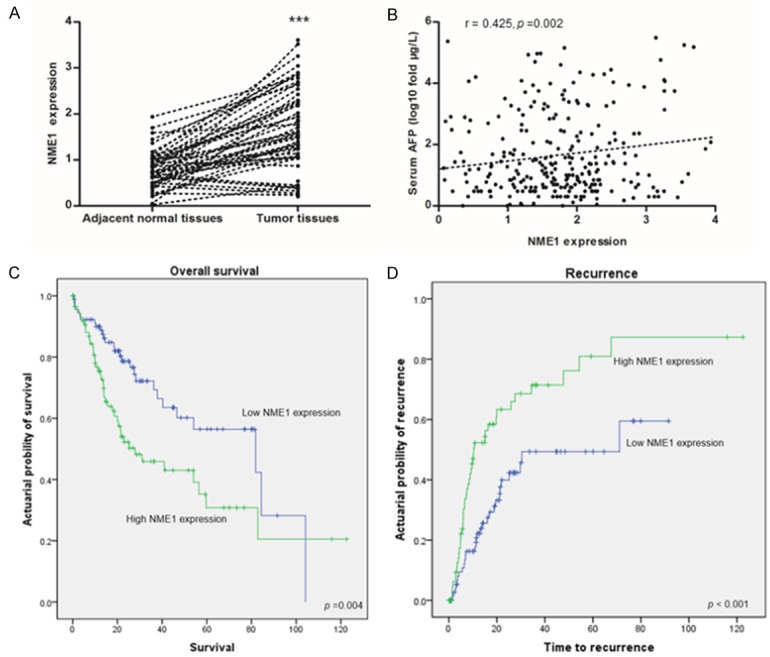

High NME1 expression was associated with poor prognosis in HCC patients

To confirm NME1 function in HCC, we download gene expression data and clinical data of 438 HCC patients from TCGA database. We explored mRNA expression of NME1 in 377 primary tumor tissues and 59 adjacent normal tissues, and discovered that NME1 was significant up-regulated in HCC compared with paired adjacent normal tissues (P < 0.001, Figure 3A), which is in consistent with previous results. Besides, Spearman’s correlation test also showed that NME1 expression was positively associated with serum AFP level (r = 0.425, P = 0.002) (Figure 3B). What is more, the Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was performed to estimate the prognosis function of NME1. The median NME1 concentration in HCC patients was 1.64, with the 25th and the 75th percentile values at 1.03 and 2.21, respectively. The top quartile of NME1 concentrations (> 2.21) was defined as high NME1 expression patients, and the lowest quartile of NME1 concentrations (< 1.03) was defined as low NME1 expression patients. Notably, the low NME1 expression patients showed a higher overall survival than the high NME1 expression patients (P = 0.004, Figure 3C). Besides, the recurrence rate of HCC patients with high NME1 expression group was significantly higher than that of patients with low NME1 expression group (P < 0.001, Figure 3D), which demonstrated high NME1 expression predicted worse outcome.

Figure 3.

The expression and prognostic value of NME1 were explored by RNA-seq in TCGA database. A. Matched adjacent normal tissues (n = 59) vs HCC tumor tissues (n = 59); B. The correlation between NME1 expression and serum AFP level (n = 377); C and D. Kaplan-Meier curves and estimates of overall survival and recurrence in patients with high or low NME1 expression, p values are calculated based on the log-rank test, ***P < 0.001.

Discussion

NME1 was a metastatic suppressor because of its down-regulated expression in highly metastatic murine melanoma cell lines [25]. Previous studies demonstrated that over-expression of NME1 could reduce cell motility in various tumors cell lines, such as melanoma, breast carcinoma, and prostate cell lines [26-28]. Meanwhile, researchers discovered that the NME1 function was coincident in different cancers, and rarely study concentrated on NME1 function in HCC. Our study focused on the expression of NME1 in HCC patients and NME1 function in tumor progress and prognosis.

Our results showed that NME1 was up-regulated in HCC tissues compared to hepatitis/cirrhotic tissues or normal livers tissues in GEO database (Figure 1A, 1B). Besides, NME1 was up-regulated in HCC tissues than adjacent normal tissues in GEO database as well (Figure 1C, 1D), and this phenomenon was also observed in our study (Figures 2A, 3A). The correlation of NME1 expression with metastasis of HCC is still inconclusive, because it is mentioned in a few studies [16,29]. Boissan et al [16] found that NME1 were overexpressed in the primary liver tumors compared with non-tumor liver tissues and more ASV/NME1(-/-) mice than ASV/NME1(+/+) mice developed lung metastases in mouse models; whereas, Shimada et al [29] demonstrated that NME1 expression did not decrease in metastatic HCC but instead tended to increase at both intrahepatic and extrahepatic metastatic sites. In our study, NME1 was down-regulated in Stage III/IV HCC patients HCC patients than that in Stage I/II HCC patients (Figure 2B), which was similar to Boissan’ study, NME1 was a metastasis suppressor in HCC progression.

A parallel correlation of NME1 expression with the overall survival was observed in various human malignancies, such as laryngeal squamous cell carcinomas, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and breast cancer [30-32]. However, an inverse relationship was reported in other tumors, such as peripheral T-cell lymphoma, gastric cancer, neuroblastoma and acute myeloid leukemia [18,21,22,33-35]. Our data showed a negative effect of NME1 on survival, that patients with tumors high expressing NME1 had worse prognoses than those with low NME1 tumors (P = 0.004, Figure 3C). Besides, the high NME1 expression tumors showed significant higher recurrence rates than the low NME1 expression tumors (P < 0.001, Figure 3D).

In summary, our results for GEO database, enrolled HCC patients and TCGA database showed that expression of NME1, as its function as a metastasis suppressor gene, is correlated with poorer prognosis and higher recurrence. NME1 is a reliable indicator of prognosis and recurrence in HCC and may be a novel molecular biomarker for the targeted therapy and prognosis of HCC.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Grant from The National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC No. 81572069).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Forner A, Llovet JM, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2012;379:1245–1255. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61347-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1118–1127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1001683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E359–386. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zucman-Rossi J, Villanueva A, Nault JC, Llovet JM. Genetic landscape and biomarkers of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:1226–1239. e1224. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.05.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nahon P, Zucman-Rossi J. Single nucleotidepolymorphisms and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2012;57:663–674. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Y, Kato N, Hoshida Y, Yoshida H, Taniguchi H, Goto T, Moriyama M, Otsuka M, Shiina S, Shiratori Y, Ito Y, Omata M. Interleukin-1beta gene polymorphisms associated with hepatocellular carcinoma in hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology. 2003;37:65–71. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tarhuni A, Guyot E, Rufat P, Sutton A, Bourcier V, Grando V, Ganne-Carrie N, Ziol M, Charnaux N, Beaugrand M, Moreau R, Trinchet JC, Mansouri A, Nahon P. Impact of cytokine gene variants on the prediction and prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2014;61:342–350. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nahon P, Sutton A, Rufat P, Ziol M, Akouche H, Laguillier C, Charnaux N, Ganne-Carrie N, Grando-Lemaire V, N’Kontchou G, Trinchet JC, Gattegno L, Pessayre D, Beaugrand M. Myeloperoxidase and superoxide dismutase 2 polymorphisms comodulate the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma and death in alcoholic cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2009;50:1484–1493. doi: 10.1002/hep.23187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoon YJ, Chang HY, Ahn SH, Kim JK, Park YK, Kang DR, Park JY, Myoung SM, Kim DY, Chon CY, Han KH. MDM2 and p53 polymorphisms are associated with the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:1192–1196. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dharel N, Kato N, Muroyama R, Moriyama M, Shao RX, Kawabe T, Omata M. MDM2 promoter SNP309 is associated with the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:4867–4871. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abu Dayyeh BK, Yang M, Fuchs BC, Karl DL, Yamada S, Sninsky JJ, O’Brien TR, Dienstag JL, Tanabe KK, Chung RT HALT-C Trial Group. A functional polymorphism in the epidermal growth factor gene is associated with risk for hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:141–149. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.03.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Villanueva A, Newell P, Chiang DY, Friedman SL, Llovet JM. Genomics and signaling pathways in hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2007;27:55–76. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-960171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Villanueva A, Chiang DY, Newell P, Peix J, Thung S, Alsinet C, Tovar V, Roayaie S, Minguez B, Sole M, Battiston C, Van Laarhoven S, Fiel MI, Di Feo A, Hoshida Y, Yea S, Toffanin S, Ramos A, Martignetti JA, Mazzaferro V, Bruix J, Waxman S, Schwartz M, Meyerson M, Friedman SL, Llovet JM. Pivotal role of mTOR signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1972–1983. 1983.e1–11. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farazi PA, DePinho RA. Hepatocellular carcinoma pathogenesis: from genes to environment. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:674–687. doi: 10.1038/nrc1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao QL, Ma D, Meng L, Wang SX, Wang CY, Lu YP, Zhang AL, Li J. Association between Nm23-H1 gene expression and metastasis of ovarian carcinoma. Ai Zheng. 2004;23:650–654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boissan M, Wendum D, Arnaud-Dabernat S, Munier A, Debray M, Lascu I, Daniel JY, Lacombe ML. Increased lung metastasis in transgenic NM23-Null/SV40 mice with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:836–845. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tokunaga Y, Urano T, Furukawa K, Kondo H, Kanematsu T, Shiku H. Reduced expression of nm23-H1, but not of nm23-H2, is concordant with the frequency of lymph-node metastasis of human breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 1993;55:66–71. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910550113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carotenuto M, Pedone E, Diana D, de Antonellis P, Dzeroski S, Marino N, Navas L, Di Dato V, Scoppettuolo MN, Cimmino F, Correale S, Pirone L, Monti SM, Bruder E, Zenko B, Slavkov I, Pastorino F, Ponzoni M, Schulte JH, Schramm A, Eggert A, Westermann F, Arrigoni G, Accordi B, Basso G, Saviano M, Fattorusso R, Zollo M. Neuroblastoma tumorigenesis is regulated through the Nm23-H1/h-Prune C-terminal interaction. Sci Rep. 2013;3:1351. doi: 10.1038/srep01351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lindmark G. NM-23 H1 immunohistochemistry is not useful as predictor of metastatic potential of colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 1996;74:1413–1418. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martinez JA, Prevot S, Nordlinger B, Nguyen TM, Lacarriere Y, Munier A, Lascu I, Vaillant JC, Capeau J, Lacombe ML. Overexpression of nm23-H1 and nm23-H2 genes in colorectal carcinomas and loss of nm23-H1 expression in advanced tumour stages. Gut. 1995;37:712–720. doi: 10.1136/gut.37.5.712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang CS, Lin KH, Hsu YC, Hsueh S. Distant metastasis of gastric cancer is associated with elevated expression of the antimetastatic nm23 gene. Cancer Lett. 1998;128:23–29. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(98)00043-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muller W, Schneiders A, Hommel G, Gabbert HE. Expression of nm23 in gastric carcinoma: association with tumor progression and poor prognosis. Cancer. 1998;83:2481–2487. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19981215)83:12<2481::aid-cncr11>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Terada R, Yasutake T, Nakamura S, Hisamatsu T, Sawai T, Yamaguchi H, Nakagoe T, Ayabe H, Tagawa Y. Clinical significance of nm23 expression and chromosome 17 numerical aberrations in primary gastric cancer. Med Oncol. 2002;19:239–248. doi: 10.1385/MO:19:4:239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilks C, Cline MS, Weiler E, Diehkans M, Craft B, Martin C, Murphy D, Pierce H, Black J, Nelson D, Litzinger B, Hatton T, Maltbie L, Ainsworth M, Allen P, Rosewood L, Mitchell E, Smith B, Warner J, Groboske J, Telc H, Wilson D, Sanford B, Schmidt H, Haussler D, Maltbie D. The cancer genomics hub (CGHub): overcoming cancer through the power of torrential data. Database (Oxford) 2014:2014. doi: 10.1093/database/bau093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steeg PS, Bevilacqua G, Kopper L, Thorgeirsson UP, Talmadge JE, Liotta LA, Sobel ME. Evidence for a novel gene associated with low tumor metastatic potential. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1988;80:200–204. doi: 10.1093/jnci/80.3.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steeg PS, Horak CE, Miller KD. Clinicaltranslational approaches to the Nm23-H1 metastasis suppressor. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:5006–5012. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Y, Zhou Q, Sun Z, Sun Z, Wang Y, Qin Y, Zhu W, Chen X. [Experimental study on molecular mechanism of nm23-H1 gene transfection reversing the malignant phenotype of human high-metastatic large cell lung cancer cell line] . Zhongguo Fei Ai Za Zhi. 2006;9:307–311. doi: 10.3779/j.issn.1009-3419.2006.04.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miyazaki H, Fukuda M, Ishijima Y, Takagi Y, Iimura T, Negishi A, Hirayama R, Ishikawa N, Amagasa T, Kimura N. Overexpression of nm23-H2/NDP kinase B in a human oral squamous cell carcinoma cell line results in reduced metastasis, differentiated phenotype in the metastatic site, and growth factor-independent proliferative activity in culture. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:4301–4307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shimada M, Taguchi K, Hasegawa H, Gion T, Shirabe K, Tsuneyoshi M, Sugimachi K. Nm23-H1 expression in intrahepatic or extrahepatic metastases of hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver. 1998;18:337–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0676.1998.tb00815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marioni G, Ottaviano G, Lionello M, Lora L, Lovato A, Staffieri C, Favaretto N, Giacomelli L, Stellini E, Staffieri A, Blandamura S. Nm23-H1 nuclear expression is associated with a more favourable prognosis in laryngeal carcinoma: univariate and multivariate analysis. Histopathology. 2012;61:1057–1064. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2012.04331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hirayama R, Sawai S, Takagi Y, Mishima Y, Kimura N, Shimada N, Esaki Y, Kurashima C, Utsuyama M, Hirokawa K. Positive relationship between expression of anti-metastatic factor (nm23 gene product or nucleoside diphosphate kinase) and good prognosis in human breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1991;83:1249–1250. doi: 10.1093/jnci/83.17.1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang YF, Chang CJ, Chiu JH, Lin CP, Li WY, Chang SY, Chu PY, Tai SK, Chen YJ. NM23-H1 expression of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in association with the response to cisplatin treatment. Oncotarget. 2014;5:7392–7405. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Niitsu N, Nakamine H, Okamoto M. Expression of nm23-H1 is associated with poor prognosis in peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:2893–2899. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Niitsu N. The association of nm23-H1 expression with a poor prognosis in patients with peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified. J Clin Exp Hematop. 2014;54:171–177. doi: 10.3960/jslrt.54.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lilly AJ, Khanim FL, Hayden RE, Luong QT, Drayson MT, Bunce CM. Nm23-h1 indirectly promotes the survival of acute myeloid leukemia blast cells by binding to more mature components of the leukemic clone. Cancer Res. 2011;71:1177–1186. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]