Abstract

Human impact on the environment is evident across the planet, including its most biodiverse areas. Of particular interest is the impact on the world’s last wilderness areas, in which the largest patches of land relatively free from human influence remain. Here, we use the human footprint index to measure the extent to which the world’s last wilderness areas have been impacted by human activities—between the years 1993 and 2009—and whether protected areas have been effective in reducing human impact. We found that overall the increase in human footprint was higher in tropical than temperate regions. Moreover, although on average the increase was lower inside protected areas than outside, in half of the fourteen biomes examined the differences were insignificant. Although reasons varied, protected areas alone are unlikely to be ubiquitously successful in protecting wilderness areas. To achieve protection, it is important to address loss and improve environmental governance.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13280-019-01213-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Biodiversity conservation, Human footprint, IUCN protected areas, Last of the wild, Terrestrial biomes

Introduction

Anthropogenic activities are altering the world’s ecosystems at a substantial rate, often resulting in habitat degradation and biodiversity loss (Jenkins 2003; Butchart et al. 2010; Newbold et al. 2016; Tilman et al. 2017). These changes have been most dramatic in the recent centuries, if not decades (Corlett 2015), and have been driven by remarkable advances in technological capacity as well as a rising demand for natural resources (Jenkins 2003; Butchart et al. 2010). Humans are now extracting more resources than ever before and, consequently, have an immense ecological footprint on the world’s natural environment (Butchart et al. 2010; Venter et al. 2016b; Watson et al. 2016b).

As the human population, and its demand for natural resources, continues to increase (Butchart et al. 2010; Rands et al. 2010), its impact on the planet will likely intensify (Jenkins 2003; Butchart et al. 2010). This prospect makes the conservation of the natural environment—on which humans depend for key ecosystem services (Cardinale et al. 2012), such clean air and water (Rands et al. 2010)—challenging (Butchart et al. 2010). To address this challenge, it is imperative to understand the spatial and the temporal patterns of human influences on biodiversity (Venter et al. 2016b).

Advances in geospatial technology and computing power have facilitated the generation of large volumes of data, which can be used to inform conservation decisions at the global level (Pettorelli et al. 2014). One of such large datasets is the human footprint index, made available by Venter et al. (2016a), which quantifies human impact across the planet at a resolution of 1 km2. The human footprint index is a composite measure of eight different human pressures, including human population density and extent of infrastructure and agricultural land (Venter et al. 2016a). Importantly, the index is available for two different time periods—1993 and 2009—enabling temporal comparisons. According to Venter et al. (2016a), during this time period, the human footprint had increased in most of the world’s ecoregions (Olson et al. 2001), especially those in the tropics (Venter et al. 2016b). As a result, by 2009, more than three-quarters of the planet were already affected by a “measurable degree of human impact,” including many of the world’s most biodiverse areas (Venter et al. 2016b).

Of particular interest are the world’s last wilderness areas (Sanderson et al. 2002), which hold much of the earth’s biodiversity and are imperative to the achievement of the global conservation goals (Watson et al. 2016a), as exemplified in the Aichi targets of the United Nation’s Convention on Biological Diversity (Butchart et al. 2010) and the Sustainable Development Goals (Sachs 2012). Wilderness areas represent the planet’s last large contiguous regions with little to no human influence (Sanderson et al. 2002). They are important not only for preserving biodiversity, but also for combating climate change—through carbon sequestration for example—and for supporting local indigenous communities (Watson et al. 2016a). A recent analysis by Watson et al. (2016a) has shown that many parts of these wilderness areas—across the world’s fourteen terrestrial biomes (Olson et al. 2001)—have already been degraded and are now heavily impacted by anthropogenic activities. Consequently, in response, Watson et al. (2016a) call for an increase in protected areas in wilderness regions in order to mitigate increases in human impact.

It is not clear, though, to what extent protected areas actually contribute to the conservation of these wilderness areas. Although, indeed, on average, protected areas tend to mitigate human impact (Jones et al. 2018), currently, about a third of the protected land, worldwide, shows signs of intense human pressure (Jones et al. 2018). A growing body of literature suggests that the effectiveness of protected areas is not globally homogeneous (Leverington et al. 2010; Heino et al. 2015; Jones et al. 2018). On the contrary, it appears to differ across regions (Joppa and Pfaff 2011; Pouzols et al. 2014). For example, the proportion of protected land under intense human pressure varies substantially across the world’s biomes (Jones et al. 2018). The same is true for the overall percentage of land under intense human pressure within each biome (Watson et al. 2016b; Jones et al. 2018), which is often unrelated to the biome’s total percentage of the land protected. Mangrove forests, for instance, have one of the highest percentages of protected land (Jones et al. 2018) and yet most of the biome is under intense human pressure (Watson et al. 2016b)—including half of its protected land (Jones et al. 2018). In contrast, boreal forests remain for the most part under relatively low human pressure (Watson et al. 2016b), despite the fact that most of the biome’s land is not protected (Watson et al. 2016b; Jones et al. 2018).

It is worth clarifying here that not all protected areas are the same. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) recognizes six different categories of protected areas (i.e., Ia, Ib, II, III, IV, V, and VI), mostly classified according to their management objectives, types of land uses permitted, and levels of legislative protection (Leroux et al. 2010). For instance, areas belonging to Category Ia, i.e., “strict nature reserves,” are designated primarily for biodiversity conservation and tend to require strict protection. In comparison, areas belonging to Category VI, i.e., “protected areas with sustainable use of natural resources,” are often less strict and permit multiple uses (Leroux et al. 2010). Moreover, many of the world’s protected areas are not assigned to any IUCN category (Jones et al. 2018). Currently, it is unclear to what extent these categories reflect the protected areas’ capacity to mitigate human impact within wilderness areas. This is an important question to answer because—for reasons that go beyond the scope of this study—newly established areas tend to disproportionately belong to multi-use categories (McDonald and Boucher 2011). It is essential, therefore, to assess whether the capacity of the protected areas to mitigate human impact varies according to their IUCN category. Considering that the categories are linked to the management strategy of the protected areas (Leroux et al. 2010), one would expect that areas in stricter categories (e.g., IUCN I and II; Jones et al. 2018) are affected less by anthropogenic disturbance. An increasing body of literature, however, suggests that the IUCN categories do not necessarily reflect the capacity of the protected areas to mitigate human impact (Leroux et al. 2010; Jones et al. 2018).

In summary, two questions remain unanswered with regard to the world’s last wilderness regions: (a) To what extent can protected areas reduce human impact within those regions? (b) Is this extent related to the IUCN category of the protected areas? To address these knowledge gaps, we first use the human footprint index from years 1993 and 2009 (Venter et al. 2016a, b) to measure the change in human impact in the world’s last wilderness areas during the 16-year period. Then, we use a quasi-experimental approach—called “matching” (Ho et al. 2011)—to compare the change within protected areas vs. the change outside, within each of earth’s terrestrial biomes (Olson et al. 2001). In this way, we assess whether or not protected areas have been indeed successful in mitigating human impact in the remaining wilderness regions. Then, we assess whether or not the effectiveness of protected areas depends on their IUCN category; in other words, we examine whether areas with more strict protection status (i.e., IUCN categories I to II) are more successful in reducing impact when compared to areas with a less strict status (III to VI) or no status at all.

Materials and Methods

Data collection and preparation

We downloaded the spatial data of wilderness areas (Sanderson et al. 2002) from the Socioeconomic Data and Applications Center (SEDAC) at http://sedac.ciesin.columbia.edu/data/set/wildareas-v1-last-of-the-wild-ighp. We chose to use the 1st version of the dataset, covering years 1992 to 1995, in order to match the first year for which the human footprint data are available (i.e., 1993). The wilderness data depict the last wild areas in each of the earth’s terrestrial biomes (Olson et al. 2001), at a resolution of 1 km2. Sanderson et al. (2002) defined as “wilderness areas” those areas with the lowest 10% of human influence score, based on an index ranging from 0 to 100. From these, they identified and mapped the ten largest contiguous wild areas in each terrestrial realm and biome (Sanderson et al. 2002). Following the methods of Watson et al. (2016a, b), we excluded from our analyses wild areas located within the “rock and ice” biome and areas not assigned a biome at all, leaving in total areas in 14 terrestrial biomes (Table 1).

Table 1.

Mean human footprint values (HFP), in 1993 and 2009, within the world’s last wilderness areas

| Biome | HFP 1993 | HFP 2009 | HFP change | HFP change (inside protected areas) | HFP change (outside protected areas) | Net change in intense human pressure (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests | 0.64 | 1.11 | 0.47 | 0.20 | 0.51 | 3.71 |

| Tropical and subtropical dry broadleaf forests | 1.49 | 2.34 | 0.86 | 0.59 | 0.89 | 10.11 |

| Tropical and subtropical coniferous forests | 2.82 | 2.96 | 0.14 | 0.99 | 0.13 | 0.41 |

| Temperate broadleaf and mixed forests | 0.83 | 0.84 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.93 |

| Temperate coniferous forests | 0.69 | 0.86 | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.18 | 1.14 |

| Boreal forests | 0.21 | 0.22 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.17 |

| Tropical and subtropical grasslands, savannas, and shrublands | 1.74 | 2.16 | 0.41 | 0.08 | 0.45 | 5.21 |

| Temperate grasslands, savannas, and shrublands | 2.92 | 3.23 | 0.31 | 0.18 | 0.31 | 6.19 |

| Flooded grasslands and savannas | 1.72 | 2.14 | 0.42 | 0.19 | 0.46 | 3.98 |

| Montane grasslands and shrublands | 0.92 | 1.20 | 0.28 | 0.17 | 0.29 | 2.23 |

| Tundra | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.20 |

| Mediterranean forests, woodlands, and scrub | 2.88 | 3.08 | 0.20 | 0.06 | 0.20 | 3.64 |

| Deserts and xeric shrublands | 0.74 | 0.82 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.38 |

| Mangrove forests | 1.37 | 2.09 | 0.72 | 0.21 | 0.90 | 10.59 |

The change during the 16-year period is also shown, along with the percentage of the total area experiencing a net increase in intense human pressure (i.e., human footprint ≥ 4)

Data on human footprint values were obtained from Venter et al. (2016b). We used the most updated version of the data, which show the human footprint across the globe for two different years—1993 and 2009—at a resolution of 1 km2 (pixel size). Venter et al. (2016b) calculated the human footprint by measuring eight different human pressures: (1) extent of built environments; (2) crop land; (3) pasture land; (4) human population density; (5) night-time lights; (6) railways; (7) roads; and (8) navigable waterways. Each human pressure was weighted according to its potential impact on biodiversity (Venter et al. 2016a). A cumulative score between 0 and 50 was assigned to each pixel, with zero having no human impact (Venter et al. 2016a).

To compare changes in human footprint inside and outside protected areas, we used the World Database on Protected Areas (October 2018 version), made available by the United Nations World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC) at https://www.protectedplanet.net/. In preparing these data, we followed the methods of Jones et al. (2018), as well as the best practices guidelines prepared by UNEP-WCMC and found at https://www.protectedplanet.net/c/calculating-protected-area-coverage. We first excluded protected areas stored as points and retained only the polygons with a protected area status of “designated,” “inscribed,” or “established.” We then removed all marine areas and clipped the remaining areas to a terrestrial coastline obtained from Brooks et al. (2016), to remove any remaining marine parcels. To avoid errors related to the resolution of the datasets—and in accordance with Jones et al. (2018)—we kept only areas ≥ 5 km2 (n = 52 281), after dissolving polygons belonging to the same protected area. In cases where protected areas had multiple polygons assigned to different IUCN categories, we assigned to the whole area the most stringent IUCN category, i.e., the lowest numeral from I to VI (Jones et al. 2018). To create a comparable dataset across the 16-year period examined, we excluded protected areas established after 1993 (Jones et al. 2018). In cases where there were multiple years of establishment for a protected area (i.e., when individual parcels were established in different years), the oldest year was retained for the whole area. For protected areas without a listed year of establishment, we followed the approach of Jones et al. (2018), and generated a random year based on the known years of establishment for the other protected areas of the specific country. We classified protected areas into three groups according to their IUCN category (Jones et al. 2018): (a) I–II; (b) III–VI; and (c) no assigned IUCN category.

Quasi-experimental matching analysis

Studies comparing protected areas to areas not protected must control for confounding variables that may influence the observed patterns, regardless of protection status (Andam et al. 2008; Andrew et al. 2011; Joppa and Pfaff 2011). For example, in studies like ours, it is advisable to correct for topographical differences, such as elevation and slope, because areas at higher elevations and on steeper slopes tend to be less accessible and less suitable for various human uses (e.g., agriculture). Therefore, they are less likely to be impacted by humans, regardless of their protected status. This can be achieved using the “matching” technique (Andam et al. 2008; Andrew et al. 2011; Joppa and Pfaff 2011), a quasi-experimental approach that allows researchers to generate a dataset that controls for confounding variables (Ho et al. 2011).

To build the matched dataset, we first used ArcMap to generate a series of random points across all wilderness areas. Specifically, we generated one random point for every 100 km2 of wilderness areas, in each of the 14 terrestrial biomes, producing a total of 334 203 random points. At each point we recorded (1) the human footprint in 1993 and 2009; (2) the elevation and slope; (3) the biome and country; and (4) whether the point was inside or outside a protected area. To calculate slope and elevation, we used the elevation files from US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), available at http://www.ngdc.noaa.gov/mgg/topo/gltiles.html. To create a mosaic file of elevation data, we followed the guidelines listed on NOAA’s site, available at http://www.ngdc.noaa.gov/mgg/topo/elev/esri/arcgis. We used the resulting raster to calculate elevation and slope in degrees.

We used the “matchit” package in R (Ho et al. 2011) to generate a matched dataset for each of the 14 biomes examined. In addition to controlling for differences in elevation and slope, we controlled for the different countries in which the points were found. This was necessary because areas in different countries are not directly comparable due to dissimilarities in socioeconomic factors as well as environmental governance. Additionally, we controlled for the human footprint value in 1993, because the increase in human footprint partially depends on the initial value (Watson et al. 2016b). We used the “nearest neighbor” approach to match each point within protected areas to two points located outside (Ho et al. 2011), separately for each biome. Using the resulting matched dataset, we tested for differences in increases of human footprint inside and outside protected areas, using the non-parametric Wilcoxon test. To test whether or not the increase in human footprint varied between the three groups of IUCN categories of protected areas, we used the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test.

Results

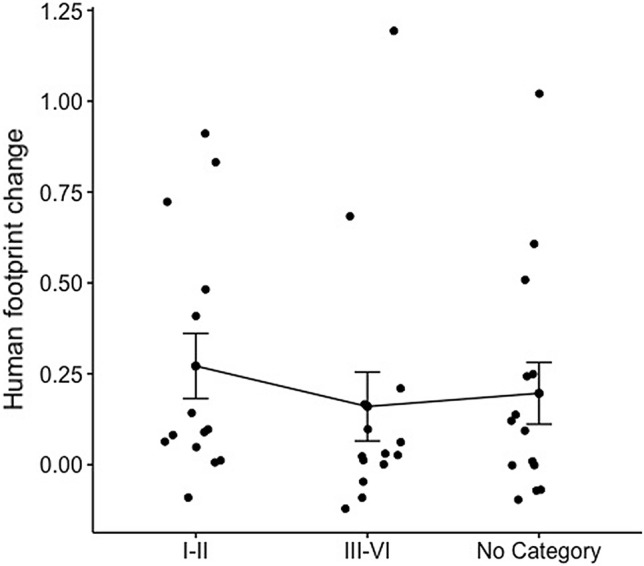

On average, during the 16-year period examined, human footprint in wilderness areas increased by 0.29 (sd = 0.26; Table 1). The average increase of human footprint inside protected areas was 0.20 (sd = 0.28), while that of those outside protected areas was 0.32 (sd = 0.30). In 1993, protected areas covered approximately 10% of the area of the wilderness regions in each biome (sd = 6.7%; Table S1). The corresponding percentage currently is approximately 23% (sd = 15.4%), with some biomes having more than one-third of their extent covered by protected areas (Table S2). There was no statistical difference between the increases in human footprint within the three types of protected areas, i.e., (a) strict; (b) non-strict; and (c) no IUCN category (Kruskal–Wallis Chi squared = 1.65, df = 2, p value = 0.4; Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Change in human footprint within each of the three groups of protected areas, classified according to their IUCN Category

On average, approximately 3.5% (sd = 3.5%) of the area of wilderness regions had experienced a net increase in intense human pressure, i.e., human footprint ≥ 4 (Jones et al. 2018). The results, though, varied according to the biome examined. Intense human pressure has increased most in mangrove forests and tropical and subtropical dry broadleaf forests, in which, by 2009, more than 10% of their area experienced a net increase in intense human pressure (10.6% and 10.1%, respectively; Table 1).

The highest overall average increase in human footprint occurred in tropical and subtropical dry broadleaf forests (0.86; Table 1), while the lowest occurred in boreal forests and temperate broadleaf and mixed forests (overall average increase of 0.01 in each). In all but two of the biomes, the increase in human footprint was lower inside than outside protected areas. Those two were: (1) boreal forests (in which the increase was relatively low both inside and outside protected areas, but slightly higher inside; 0.02 vs. 0.01), and (2) tropical and subtropical coniferous forests, which, when compared to other biomes, experienced the most change inside protected areas (0.99).

The results of our matching analysis reveal that after controlling for differences in elevation, slope, country, and human footprint in 1993, the differences in change of human footprint inside and outside protected areas were not statistically significant for 7 out of the 14 biomes (Table S3). In some of those biomes, such as the temperate coniferous forests, the lack of statistical significance can be attributed to the fact that change in human footprint was relatively small both inside and outside protected areas (i.e., − 0.01 vs. − 0.03, respectively). However, in other biomes, such as the tropical and subtropical dry broadleaf forests, change in human footprint was relatively high in both types of areas (0.61 vs. 1.29, respectively). In montane grasslands and shrublands, change was slightly higher within protected areas than outside (Table S3), but the difference was not statistically significant. Of the rest of the biomes for which differences in change were statistically significant, in all cases, the change was lower inside than outside protected areas (Table S3). An important point to be made here is that statistical significance is not only determined by the magnitude of the effect but also by the sample size (i.e., the number of matched points; Table S3), which influences the power of any statistical test (Wasserstein et al. 2019). Consequently, in our case, statistical tests involving larger biomes, which result in more matched points, have higher power; p values, therefore, must be interpreted in light of this fact (Krausman 2017; Dushoff et al. 2018; Wasserstein et al. 2019).

Discussion

Several important messages result from our analyses. While the average increase of human footprint in wild areas has been lower than the increase reported for other regions of the world (Venter et al. 2016b), human footprint has, nonetheless, intensified substantially in some of the remaining wild areas (Watson et al. 2016a). This was particularly true of tropical regions, such as mangrove forests, as well as tropical and subtropical dry broadleaf forests—of which an additional 10% of their area is now under intense human pressure (i.e., human footprint ≥ 4; Jones et al. 2018). In fact, with the exception of temperate grasslands, savannas, and shrublands—which have experienced the third largest net increase in intense human pressure (Table 1)—a major pattern emerges from our analyses: wild areas in temperate biomes (e.g., boreal forests and tundra) remain relatively free of substantial increases in intense human pressure (Table 1), while wild areas in tropical and subtropical biomes are increasingly impacted by human activities. This pattern is alarming because tropical and subtropical regions tend to host most of the world’s biodiversity (Olson et al. 2001; Venter et al. 2016b; Watson et al. 2016a). Wild areas within those regions are especially important because, by definition, they represent the last largest intact areas within those biomes (Sanderson et al. 2002). Large, intact areas are essential to conservation (Watson et al. 2016a) since they have the capacity to support habitats and species that smaller fragmented areas cannot (Mittermeier et al. 2003; Watson et al. 2016a, 2018). Moreover, their large size and intactness allow them to perform key ecosystem services—at a vast scale—that are vital to the humans and the environment (Watson et al. 2016a, 2018). Consequently, the ongoing degradation of those wild areas, especially in the tropical and subtropical regions, can result in significant cascading effects (Watson et al. 2016a).

On a more positive note, the percentage of protected land within the world’s last wild areas has increased substantially during the last few decades (Table S2). In nine of the fourteen biomes, the percentage of protected land has more than doubled. In fact, in some it is now higher than the overall percentage within the corresponding biome (Watson et al. 2016b). In addition, in seven biomes, the current percentage of protected land exceeds the 17% globally agreed target (Table S2), described in Aichi Target 11 of the Convention on Biological Diversity (Pouzols et al. 2014; Venter et al. 2014). However, the degree by which protected areas are able to mitigate human impact within wild areas varies across biomes. Although on average increases in human footprint in wild areas tend to be lower within protected areas (compared to areas outside)—a pattern also found for other parts of the world (Jones et al. 2018)—there were notable exceptions (Tables 1 and S3), likely driven by different processes.

For instance, in boreal forests, as well as in tundra, the differences in human impact within areas inside and outside protected areas were minimal. This pattern, though, was likely not because protected areas there were ineffective, but rather because the increase in mean human footprint in those two biomes was in general low. Therefore, additional protected areas within the wild areas in those biomes may not result in substantial benefits—assuming, of course, that the current trends in human impact, within those biomes, do not change drastically. Using long-term data, spanning 300 years, Ellis et al. (2010) showed that changes in land use within boreal forests and tundra—and generally within the colder and drier regions of the planet—have been traditionally lower.

At the other end of the spectrum, there are biomes, such the tropical and subtropical dry broadleaf forests, in which the increases in human footprint were considerable, both inside and outside protected areas (Ellis et al. 2010). In those biomes, the insubstantial differences between protected areas and areas not protected can be attributed mostly to the fact that the former were unable to mitigate effectively the increases in human impact, which were in general high. This suggests that the conservation of wild areas in those regions will depend on measures beyond establishing additional protected areas (Tilman et al. 2017). First, the socioeconomic factors that are driving the intensification of human impact within these areas must be addressed (Rands et al. 2010; Sloan and Sayer 2015). Growing human populations (United Nations 2017) are exerting an increasing pressure on natural environments and this pressure can be expected to impact further wild areas. According to the most recent projections of the human populations (United Nations 2017), most of the increases will occur in developing countries, many of which are located in biodiverse biomes experiencing the most change in human footprint. Agriculture, which is another known major driver of human impact within natural environments (Ramankutty et al. 2018)—and one of the metrics included in the human footprint index—is also projected to increase within many of these countries (Ramankutty et al. 2018). It is, therefore, important that the countries affected the most take the necessary steps to address this rising human impact (Tilman et al. 2017).

Second, it is necessary to have more effective governance of protected areas in wilderness regions experiencing large increases in human footprint values (Leverington et al. 2010; Watson et al. 2014). This is particularly true for those cases where the impact is higher or equally high in protected areas as in areas outside (Tables 1 and S3). Such cases show that protected areas within those regions are unable to mitigate human impact effectively. It must be clarified here, however, that even in those non-temperate regions in which the increases in human impact were lower within protected areas (compared to areas outside), often, the increases were still too large to be sustainable (Table 1). For example, in tropical and subtropical dry broadleaf forests, the increase in human footprint within protected areas was indeed lower than outside (i.e., 0.59 vs. 0.89), but still greater than what was observed in most temperate regions (both inside and outside protected areas; Table 1). To put these numbers into perspective, the current literature defines as “intense human pressure” any mean human footprint value ≥ 4 (Watson et al. 2016b; Jones et al. 2018). An increase in mean human footprint of 0.59—within a sixteen-year period only—suggests that the level of protection afforded to those wild areas is likely inadequate and unsustainable in the long-term. Moreover, this premise does not take into account the fact that much of the land within wild areas is found outside protected areas (Table S2), where the increases in human pressure are often even higher (Table 1). Interestingly, the IUCN category of protected areas is not an important determinant of the increase in human footprint (Jones et al. 2018). Other studies, too, have found that the IUCN categories do not necessarily reflect the levels of increase in human disturbance within protected areas (Leroux et al. 2010; Coetzee et al. 2014; Jones et al. 2018).

Note, our results are only based on the eight human pressures used to develop the human footprint index. We acknowledge that there are additional pressures influencing biodiversity, likely not reflected in our analyses (Rands et al. 2010; Hulme 2018). Some of those include pollution, invasive species, and overexploitation, e.g., from hunting (Rands et al. 2010; Hulme 2018). Although several of these pressures likely correlate with the pressures already included in the human footprint (Jones et al. 2018)—e.g., hunting and human population density and accessibility due to roads—since we did not explicitly incorporate them into our analysis, our results are likely to be an underestimate of the total threats to world’s wilderness areas.

In conclusion, we echo Watson et al. (2016a) in their call for more protected areas to address human impact in remaining wild areas, especially in those biomes where human activities are intensifying. Although additional protected areas in wild regions where increases in human impact remain low may not have a large effect, in other biomes—such as in tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests—protected areas do seem to play an important role in restricting threats to biodiversity. However, establishing protected areas alone will not be enough to successfully address the effects of human activities on the environment. It is important that the socioeconomic factors driving the increases in human footprint within the world’s last wilderness areas are addressed. In addition, effective management of the protected areas and successful governance is an imperative, since it is clear that in some biomes human pressure has intensified more within protected areas, or at least as much as outside. Finally, the concept of wilderness areas requires more attention at the international and national conservation fora in order to highlight the importance of these remaining large, intact wild areas (Watson et al. 2016a).

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to the researchers who have developed and made available the datasets we used in this study. We are also thankful to two anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback. E.A. is also thankful to the Freeman Foundation and Furman University, in the United States, for a Grant supporting her stay in China.

Biographies

Emily Anderson

is an ecologist interested in studying how human activities affect biodiversity. She is currently employed as a Forest Stewards Guild Forestry Intern for the US Fish and Wildlife Service at Carolina Sandhills National Wildlife Refuge in McBee, South Carolina—a longleaf pine habitat in the South Eastern US.

Christos Mammides

is a conservation biologist interested in using statistical and spatial tools to understand anthropogenic impact on biodiversity. He is currently employed as an Associate Professor at Guangxi University in China.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Emily Anderson, Email: ecanderson96@gmail.com.

Christos Mammides, Email: cmammides@outlook.com.

References

- Andam KS, Ferraro PJ, Pfaff A, Sanchez-Azofeifa GA, Robalino JA. Measuring the effectiveness of protected area networks in reducing deforestation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2008;105:16089–16094. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800437105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrew N, Nelson A, Chomitz KM. Effectiveness of strict vs. multiple use protected areas in reducing tropical forest fires: A global analysis using matching methods. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e22722–e22722. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks TM, Akçakaya HR, Burgess ND, Butchart SHM, Hilton-Taylor C, Hoffmann M, Juffe-Bignoli D, Kingston N, et al. Data from: Analysing biodiversity and conservation knowledge products to support regional environmental assessments. Scientific Data. 2016;3:160007. doi: 10.5061/dryad.6gb90.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butchart SHM, Walpole M, Collen B, Van Strien A, Scharlemann JPW, Almond REA, Baillie JEM, Bomhard B, et al. Global biodiversity: Indicators of recent declines. Science. 2010;328:1164–1168. doi: 10.1126/science.1187512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardinale BJ, Duffy JE, Gonzalez A, Hooper DU, Perrings C, Venail P, Narwani A, Mace GM, et al. Biodiversity loss and its impact on humanity. Nature. 2012;486:59–67. doi: 10.1038/nature11148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coetzee BWT, Gaston KJ, Chown SL. Local scale comparisons of biodiversity as a test for global protected area ecological performance: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e105824. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corlett RT. The anthropocene concept in ecology and conservation. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 2015;30:36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dushoff J, Kain MP, Bolker BM. I can see clearly now: Reinterpreting statistical significance. Methods in Ecology and Evolution. 2018;10:756–759. doi: 10.1111/2041-210X.13159. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis EC, Klein Goldewijk K, Siebert S, Lightman D, Ramankutty N. Anthropogenic transformation of the biomes, 1700 to 2000. Global Ecology and Biogeography. 2010;19:589–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-8238.2010.00540.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heino M, Kummu M, Makkonen M, Mulligan M, Verburg PH, Jalava M, Räsänen TA. Forest loss in protected areas and intact forest landscapes: A global analysis. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:1–21. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho DE, Imai K, King G, Stuart EA. MatchIt: Nonparametric preprocessing for parametric causal inference. Journal of Statistical Software. 2011;42:1–28. doi: 10.18637/jss.v042.i08. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hulme PE. Protected land: Threat of invasive species. Science. 2018;361:561–562. doi: 10.1126/science.aau3784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins M. Prospects for biodiversity. Science. 2003;302:1175–1177. doi: 10.1126/science.1088666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones KR, Venter O, Fuller RA, Allan JR, Maxwell SL, Negret PJ, Watson JEM. One-third of global protected land is under intense human pressure. Science. 2018;360:788–791. doi: 10.1126/science.aap9565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joppa LN, Pfaff A. Global protected area impacts. Proceedings of the Royal Society B Biological Sciences. 2011;278:1633–1638. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2010.1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krausman PR. P-values and reality. The Journal of Wildlife Management. 2017;81:562–563. doi: 10.1002/jwmg.21253. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leroux SJ, Krawchuk MA, Schmiegelow F, Cumming SG, Lisgo K, Anderson LG, Petkova M. Global protected areas and IUCN designations: Do the categories match the conditions? Biological Conservation. 2010;143:609–616. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2009.11.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leverington F, Costa KL, Pavese H, Lisle A, Hockings M. A global analysis of protected area management effectiveness. Environmental Management. 2010;46:685–698. doi: 10.1007/s00267-010-9564-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald RI, Boucher TM. Global development and the future of the protected area strategy. Biological Conservation. 2011;144:383–392. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2010.09.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mittermeier RA, Mittermeier CG, Brooks TM, Pilgrim JD, Konstant WR, da Fonseca GAB, Kormos C. Wilderness and biodiversity conservation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 2003;100:10309–10313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1732458100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newbold T, Hudson LN, Arnell AP, Contu S, De Palma A, Ferrier S, Hill SLL, Hoskins AJ, et al. Has land use pushed terrestrial biodiversity beyond the planetary boundary? A global assessment. Science. 2016;353:288–291. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson DM, Dinerstein E, Wikramanayake ED, Burgess ND, Powell GVN, Underwood EC, D’amico JA, Itoua I, et al. Terrestrial ecoregions of the world: A new map of life on earth. BioScience. 2001;51:933. doi: 10.1641/0006-3568(2001)051[0933:TEOTWA]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pettorelli N, Safi K, Turner W. Satellite remote sensing, biodiversity research and conservation of the future. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B Biological Sciences. 2014;369:20130190. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouzols FM, Toivonen T, Di Minin E, Kukkala AS, Kullberg P, Kuustera J, Lehtomaki J, Tenkanen H, et al. Global protected area expansion is compromised by projected land-use and parochialism. Nature. 2014;516:383–386. doi: 10.1038/nature14032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramankutty N, Mehrabi Z, Waha K, Jarvis L, Kremen C, Herrero M, Rieseberg LH. Trends in global agricultural land use: Implications for environmental health and food security. Annual Review of Plant Biology. 2018;69:789–815. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042817-040256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rands MRW, Adams WM, Bennun L, Butchart SHM, Clements A, Coomes D, Entwistle A, Hodge I, et al. Biodiversity conservation: Challenges beyond 2010. Science. 2010;329:1298–1303. doi: 10.1126/science.1189138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs JD. From millennium development goals to sustainable development goals. The Lancet. 2012;379:2206–2211. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60685-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson EW, Jaiteh M, Levy MA, Redford KH, Wannebo AV, Woolmer G. The human footprint and the last of the wild. BioScience. 2002;52:891. doi: 10.1641/0006-3568(2002)052[0891:THFATL]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan S, Sayer JA. Forest resources assessment of 2015 shows positive global trends but forest loss and degradation persist in poor tropical countries. Forest Ecology and Management. 2015;352:134–145. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2015.06.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tilman D, Clark M, Williams DR, Kimmel K, Polasky S, Packer C. Future threats to biodiversity and pathways to their prevention. Nature. 2017;546:73–81. doi: 10.1038/nature22900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. 2017. World population prospects: The 2017 revision, key findings and advance tables. Department of Economic and Social Affair, Population Division, ESA/P/WP/248.

- Venter O, Fuller RA, Segan DB, Carwardine J, Brooks T, Butchart SHM, Di Marco M, Iwamura T, et al. Targeting global protected area expansion for imperiled biodiversity. PLoS Biology. 2014;12:e1001891. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venter O, Sanderson EW, Magrach A, Allan JR, Beher J, Jones KR, Possingham HP, Laurance WF, et al. Global terrestrial human footprint maps for 1993 and 2009. Scientific Data. 2016;3:160067. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2016.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venter O, Sanderson EW, Magrach A, Allan JR, Beher J, Jones KR, Possingham HP, Laurance WF, et al. Sixteen years of change in the global terrestrial human footprint and implications for biodiversity conservation. Nature Communications. 2016;7:1–11. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserstein RL, Schirm AL, Lazar NA. Moving to a world beyond “ p < 0.05”. The American Statistician. 2019;73:1–19. doi: 10.1080/00031305.2019.1583913. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watson JEM, Dudley N, Segan DB, Hockings M. The performance and potential of protected areas. Nature. 2014;515:67–73. doi: 10.1038/nature13947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson JEM, Shanahan DF, Di Marco M, Allan J, Laurance WF, Sanderson EW, Mackey B, Venter O. Catastrophic declines in wilderness areas undermine global environment targets. Current Biology. 2016;26:2929–2934. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson JEM, Jones KR, Fuller RA, Di Marco M, Segan DB, Butchart SHM, Allan JR, McDonald-Madden E, et al. Persistent disparities between recent rates of habitat conversion and protection and implications for future global conservation targets. Conservation Letters. 2016;9:413–421. doi: 10.1111/conl.12295. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watson JEM, Evans T, Venter O, Williams B, Tulloch A, Stewart C, Thompson I, Ray JC, et al. The exceptional value of intact forest ecosystems. Nature Ecology & Evolution. 2018;2:599–610. doi: 10.1038/s41559-018-0490-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.