Abstract

Stormwater green infrastructure (GI) has the potential to provide ecosystem services (ES) that are currently lacking in many urban environments. Nevertheless, while stormwater GI presents a major opportunity for cities to enhance urban ES, there is insufficient evidence to link the complex social and ecological benefits of ES to different GI types for holistic urban planning. This study used an expert opinion methodology to identify linkages between 22 ES and 14 GI types within a New York City context. An analysis of results from five interdisciplinary workshops engaging 46 academic experts reveals that expert judgement of ES benefits is highest for larger green spaces, which are not universally considered for stormwater management, and lowest for vacant land and non-vegetated GI types. Overall, cultural services were identified as those most universally provided by GI. The results of this study highlight potential significant variations in ES benefits between different GI types, and indicate the importance of considering cultural services in future GI research and planning efforts. In the current absence of robust quantitive measurements linking ES and stormwater GI, increased qualitative insight could be obtained by expanding the methodology used in this work to include non-academic experts and other urban stakeholders. We therefore offer recommendations and learnings based on our experience with the approach.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13280-019-01223-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Co-benefits, Ecosystem services, Expert opinion, Green infrastructure, Holistic planning, Matrix model

Introduction

The term green infrastructure (GI) was coined in 1994 as part of a planning report that advocated for land conservation through a system of greenways, or GI, that were as well-planned and financed as traditional built infrastructure (Florida Greenways Commission 1994). Since then, the term has been used by planners, designers, scientists, and engineers alike to describe networks of green spaces, including natural areas such as waterways and woodlands, and built areas such as parks and community gardens—all of which are widely considered to provide an array of services to humans and the environment (Benedict and McMahon 2002; Newell et al. 2013). More recently, the need to manage urban stormwater together with the development of GI systems that reduce stormwater runoff has driven large-scale GI investments in many US cities (NYC Mayor’s Office 2010; Philadelphia Water Department 2011; NEORSD 2012; City of Chicago 2014). Further, GI planning efforts are strongly encouraged by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA), which has provided policy recommendations, community support, and technical assistance for GI adoption as part of federal regulatory programs for managing stormwater at the community, state, and regional levels. Stormwater GI includes all systems that mimic natural hydrologic processes and/or reduce urban runoff, which has expanded the term green infrastructure to include engineered structures, such as bioswales, permeable paving, and rainwater cisterns (US EPA 2014).

Today, GI is used as an umbrella term referring to the diverse systems of natural, built, and engineered infrastructure. However, its recent widespread urban adoption is often associated with stormwater best management practices (BMPs).

Municipalities developing extensive GI programs for stormwater management in order to meet minimum federal and state water quality standards are required to quantify overall stormwater benefits. Because funding and compliance hinge on this quantification, a myriad of methods and models that focus on GI planning for stormwater management are available (e.g., EPA SWMM, MUSIC, SUSTAIN, iTree-Hydro, WinSLAMM) (Jayasooriya and Ng 2014). Nonetheless, many of these GI planning tools also include a range of services that GI can provide beyond stormwater management, such as air pollution reduction (Pugh et al. 2012), carbon sequestration (Getter et al. 2009), and aesthetic benefits (Chon and Shafer 2009), citing the importance of considering the co-benefits of GI, although performance metrics for many co-benefits have yet to be fully defined or assessed.

The increasing emphasis on GI strategies and their ability to provide a range of social and ecological services has led researchers, practitioners, and decision makers to explore linkages between GI and ecosystem services (ES), defined broadly as the benefits people obtain from ecosystems (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment 2005). Several frameworks are used to classify, define, and account for ecosystem services, including the United Nations Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA), the Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (TEEB), the UK National Ecosystem Assessment (UK NEA), and the Common International Classification of Ecosystem Services (CICES), which is specifically developed for the purpose of navigating between different ES frameworks (Haines-Young 2013).

While ES frameworks are useful for conceptualizing the integration of ES in planning and decision-making, there are many critiques and challenges associated with their operational ability (Daily et al. 2009). A common starting point is often the United Nation’s multi-year and multi-million dollar MEA Framework, which has been critiqued for its vague definition of “services” as the “benefits” people obtain from ecosystems (Simpson 2011; Schröter et al. 2014). While offering a valuable taxonomy for classification, this framework does not provide empirical estimates for ecosystem values, providing minimal guidance for application (Simpson 2011). Other frameworks, such as TEEB, attempt to address operational vagueness by providing economic valuation for ecosystem services and are thus critiqued for being too reliant on dominant political and economic trends (Gómez-Baggethun and Ruiz-Pérez 2011). While there is overlap and individual challenges associated with common ES frameworks, they share the goal of demonstrating ecosystem value but lack integrative best practices for land use planning and decision-making (Haines-Young 2013).

Urban areas face a unique challenge in that they primarily rely on areas outside their city limits but still need local provision for many ES that cannot be transported, notably regulating and cultural services (Gómez-Baggethun and Barton 2013). The importance of urban ES is further underlined by the global trend towards urbanization, with more than half of the world’s population already living in urban areas (UN 2012). Before TEEB and MEA frameworks were available, ES generated by ecosystems within urban areas (street trees, parks, etc.) were explored by synthesizing available empirical data (Bolund and Hunhammar 1999). Later work, building on TEEB, mapped different approaches for classifying the value of ES in urban settings (Gómez-Baggethun and Barton 2013). However, like ES application at large, urban ES have had limited impact in their practical planning implementation (Haase et al. 2014).

Numerous publications have demonstrated the value of ES for linking green space development and conservation to environmental health, human health, security, and well-being (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment 2005; Brauman et al. 2007; Müller et al. 2010; TEEB 2010; McPherson et al. 2011). The complexity of quantitatively assessing many specific ES has made it challenging to incorporate them into planning tools in ways that are credible and replicable (Daily et al. 2009; Hansen and Pauleit 2014). In the specific context of urban GI, planning frameworks often focus on a single ES across different GI types (Norton et al. 2015) or single GI type across various ES (Dobbs 2011). Additionally, studies link the provision of various ES to a broad definition of GI that is akin to vegetated green space (i.e., Meerow and Newell 2017). This broad definition is of particular concern because the GI types that are widely implemented in urban areas for stormwater regulation usually incorporate non-vegetated structures, such as permeable pavement, cisterns, and rain barrels, which might not provide the same services as vegetated structures. Beyond the issue of inclusivity, there is highly variable performance within vegetated GI. For example, the impact on air quality varies with GI type; while vine facades have been shown to dramatically improve air quality (Pugh et al. 2012), canopies of street trees have been shown to hold pollution in the areas where people breathe (Jin et al. 2014).

Despite ongoing empirical research, the magnitude and variety of data necessary to understand the relative ES supply across GI types is virtually unattainable within existing financial and organizational limits. In essence, data scarcity and complexity plague ES decision-making (Jacobs et al. 2013; Haase et al. 2014) and result in a pragmatic dilemma between the urgency of enacting ES-informed planning and uncertainty around the effectiveness of ecological systems (Jacobs et al. 2015). In the limitations imposed by the scanty and uneven empirical data, particularly when complex problems are exacerbated by the urgency-uncertainty dilemma, expert opinion is a potential first step towards actionable understanding. Expert opinion has provided the foundation for studies on complex problems across fields, including infrastructure system vulnerability (Robert 2004) and nuclear waste storage (Kerr 1996). Within integrative ES research, several studies also use expert elicitation (e.g., Vihervaara et al. 2010; Kaiser et al. 2013). Even when consensus among experts exists, expert opinion is not a guarantee of truth but provides a way to move forward in complex situations, offers a base for validation, and informs deeper research.

A common way that expert opinion is harnessed is through the use of a “matrix model,” where different ecological structures (rows) are evaluated for an array of ecosystem services (columns) (Burkhard et al. 2009). While the matrix model is often first populated using expert knowledge (Vihervaara et al. 2010, 2012; Stoll et al. 2015), it is open to validation from other sources (Burkhard et al. 2009). The major challenges associated with the use of expert opinion in matrix models are ensuring methodological transparency, producing reproducible data, incorporating participant confidence, and validating expert estimations (Jacobs et al. 2015).

Specific to green infrastructure within a regional watershed, Kopperoinen et al. (2014) used a matrix model and expert workshop approach with local and regional experts to quantitatively assess the ecosystem service potential of multiple green infrastructure land use types (e.g., old forests, peatlands, national hiking areas); however, stormwater BMP’s were not specifically included in the study and were likely aggregated as part of an “urban green areas” land use type. Respondents were asked to use a Likert scale to evaluate linkages between each GI type and each ES. Results were then used as a measure of relevance for determining ecosystem service potential of the different GI types, as well as a means of providing insight into the selection of datasets for future model development. Our study builds on this existing work by applying the expert elicitation method to land use classes relevant to urban stormwater management, which exist at a much finer spatial scale (e.g., green roofs, bioswales, green streets, parks, vacant lots, etc.) than that explored by Kopperoinen et al. (2014).

New York City’s (NYC) active and evolving green infrastructure program provides a timely and relevant context to explore how expert elicitation can be used to qualitatively assess the ES potential of the different GI types being considered within the City’s program as an initial step towards holistic GI planning. Led by the NYC Department of Environmental Protection (NYCDEP), the objectives of the $1.5 billion program are driven by a goal of reducing stormwater runoff in combined sewer watersheds, while also providing “substantial, quantifiable co-benefits” (NYC Mayor’s Office 2010). To identify potential opportunities for incorporating co-benefits into the NYC planning process, our study sought to engage disciplinary perspectives familiar with GI co-benefits beyond stormwater performance. While the GI-ES linkages of this study were evaluated within the NYC context, the results of the study provide a point of reference for conversations about GI-ES relationships in urban settings globally, while the methodological learnings of the study are broadly applicable.

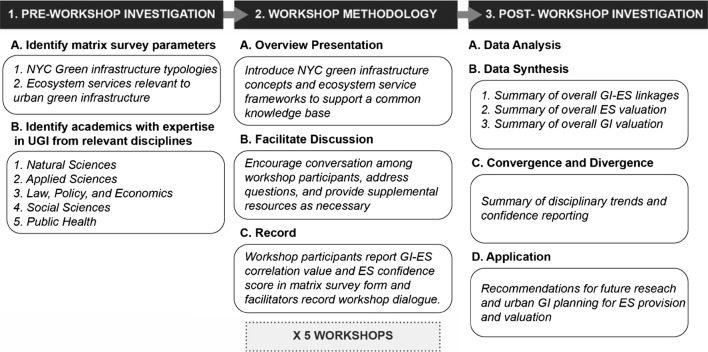

Tengö et al. (2014) recommend integrating diverse knowledge systems as part of a multiple evidence-based (MEB) approach, drawing from diverse “knowledge holders” in both the natural and social sciences to enhance policy and planning decisions for ecosystems and human well-being. Consistent with an MEB approach, our study used a workshop methodology to support a collaborative process that would emphasize and encourage communicative dialogue (Tengö et al. 2014). While GI practitioners and policy makers might be argued to have greater direct experience witnessing certain ES provisions and benefits, our study sought those in academia for their expert opinion as an initial starting point. This choice was motivated by a belief that those in a University setting were less likely to be advocates, or otherwise, for NYC’s GI program, so would be impartial, to the extent possible, in articulating judgement of linkages between ES benefits and GI. Furthermore, academia’s differentiation between disciplines provided the opportunity to compare and contrast expert judgement from diverse groups of knowledge holders. Figure 1 provides a flowchart of the methodology we used to reveal judgement linkages between the different categories of urban GI and ES within the NYC context.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart presenting phases of research methodology

Materials and methods

The data collection portion of our study consisted of five workshops that followed a protocol developed through Columbia University’s Institutional Review Board (IRB). Using the same matrix method deployed by Kopperoinen et al. (2014), the workshops surveyed individuals from various disciplinary backgrounds about their judgement of ecosystem service provision by different types of green infrastructure, along with their area of expertise, self-reported confidence in the ratings that they provided, and other comments.

Workshop participants: Set of academics

The workshop participants in this study are a cross disciplinary set of expert academics. The designation of expert assumes that an individual has sufficient knowledge within a subject area to provide a reliable opinion. Here, an expert is defined as an individual who has completed graduate-level coursework in environmental sustainability issues. Within this pool, we sought participants that had a high affinity for urban sustainability and from various segments, academic background in our case, as recommended by Jacobs et al. (2015). The participants represent a range of disciplines, including both individuals for whom urban sustainability or green infrastructure serves as the central focus of their work, and those for whom these form parts of a larger set of foci. Experts were recruited based on their regular participation and/or enrollment in established research network meetings, academic groups, and graduate courses that focus on issues relevant to urban sustainability at Columbia University (CU). In all, five separate workshops were held over a four-month time span in the spring of 2016, in which 49 participants provided through the matrix-based survey. This number greatly exceeds the recommended minimum panel size of 15 (Campagne et al. 2017). The CU participant groups included in the study are researchers engaged in a National Science Foundation funded Sustainability Research Network (SRN) focused on Integrated Urban Infrastructure Solutions for Environmentally Sustainable, Health, and Livable Cities (Sustainability Research Network 2017), researchers engaged in a National Science Foundation funded research group focused on Developing High-Performance Green Infrastructure Systems to Sustain Coastal Cities (Urban Design Lab 2016), scholars affiliated with the Center for Research on Environmental Decisions Lab (CRED 2017), scholars affiliated with the Urban Public Health Initiative Group (UPHI 2017), and graduate students from the School of International and Public Affairs (SIPA) participating in a course Adaptation to Climate Change (Orlove 2016). The range of disciplinary backgrounds represented across the five workshops included the social and behavioral sciences (psychology, anthropology, policy, and economics), applied sciences (engineering, urban design), natural sciences (biology, ecology, environmental science), and public health. Three participants are not included in the final data analysis due to incomplete matrix forms, resulting in a final analysis of 46 experts.

Workshop format

Each 90-min workshop was facilitated by the same set of lead investigators and took place during the 2016 spring academic semester. At the beginning of each workshop, the facilitators gave a 30-min presentation in which participants were introduced to the concepts of green infrastructure and ecosystem services. The full presentation is provided in Appendix S1 and our justification for the selection of the 22 ecosystem services and 14 green infrastructure types are given in “Ecosystem services” and “Green infrastructure types” sections, respectively. Following the 30-min presentation, workshop participants were given 1 h to fill out the matrix survey. During this time, participants were encouraged to discuss the rationale for their selections or other points of interest with each other (Kenter et al. 2015). Transcripts of each workshop are provided as Appendix S2.

Ecosystem services

Due to multiple appropriate ES Frameworks, we aggregate services outlined by both MEA and CICES under the 3 broad classifications recommended by CICES: Provisioning, Cultural, and Regulating, Supporting, and Maintenance. From the initial list of 66 services, ES were filtered for their potential applicability to urban green infrastructure at the investigators’ discretion. Services that were clearly non-applicable to green infrastructure (e.g., biochemical resources, genetic resources) were removed while services with relatively similar definitions were merged (e.g., Spiritual, Cultural and Aesthetic). Additionally, because much of the research and motivation behind green infrastructure implementation relates to stormwater management, specific services encompassed by Water Regulation and Wastewater Purification and Treatment were listed as separate categories. Ultimately, this resulted in the selection of 22 ES to be evaluated, as presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Ecosystem Services selected for evaluation and their encompassing categories of Cultural, Regulation and Maintenance, and Provisioning

Green infrastructure types

Green infrastructure is a broad and flexible term that has been very widely applied in green space planning initiatives (Tzoulas et al. 2007; Schilling and Logan 2008; Hoornbeek and Schwarz 2009; NYC Mayor’s Office 2010; US EPA 2014). The 14 types of green infrastructure types selected for our study encompass structures possible in the urban environment of New York City that mimic “natural hydrologic processes to reduce the quantity and/or rate of stormwater flows” across many scales (US EPA 2014). Thus, in addition to including both vegetated (e.g., green roofs) and non-vegetated (e.g., rain barrels) technologies that are considered stormwater GI, the categories included urban land cover that, while having similar hydrologic performance, is not always considered GI (e.g., vacant land). The 14 categories chosen are illustrated in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

The examined categories of green infrastructure and their placement in the urban environment including vacant land, extensive green roofs, community gardens, street trees, bioswales and stormwater green streets, green facades and living walls, cisterns and rain barrels, rain gardens, intensive green roofs, vine canopies, permeable paving, parks, detention and retention ponds, and wetlands

From a land use planning perspective, the GI types are then aggregated into categories. Vegetated Land includes natural softscapes that are constructed or preserved in the urban environment for their value aside from stormwater management. Here, vegetated land is comprised of wetlands, parks, and community gardens. Vegetated Stormwater GI consists of developed, smaller scale engineered systems including green roofs (intensive and extensive), rain gardens, detention and retention ponds, and bioswales and green streets that are constructed specifically for stormwater management. Non-vegetated Stormwater GI are engineered systems that manage stormwater through mechanical processes and include permeable paving and cisterns/rain barrels. GI types that do not fit into any of these three categories include vacant land, vine canopies, street trees, and green facades/living walls.

Recorded metrics and analysis

Confidence score

All participants were asked to rate their own confidence of understanding for ecosystem service on a scale from 1 to 4, where 1 indicated “not confident,” 2 indicated “slightly confident,” 3 indicated “confident,” and 4 indicated “very confident” in their understanding. The confidence scores are then used to filter only “confident” (3) and “very confident” (4) responses for analyzing the magnitude of GI-ES linkages. We note that evaluation research based on expert opinion has included self-assessed confidence scores from experts in some domains, particular risk assessment in areas such as threats to air traffic (Riveiro 2016) and levee failure (Hathout et al. 2016), where quantitative information is incomplete; to our knowledge, our study is the first to include such confidence scores in the assessment of ecosystem services for green infrastructure.

GI type and ES linkage

Survey participants were asked to record a correlation value for each GI-ES relationship using the matrix-based survey format. The GI-ES linkage value represented the capacity of a particular GI type to provide a particular ecosystem service. Participants were asked to think about the GI-ES linkage as representative of their discipline and within a New York City context. A scale ranging from + 3 to − 3 was used, where + 3 indicated a strong, positive linkage and − 3 indicates a strong, negative linkage, with 0 representing no correlation between the GI type and a particular ecosystem service. For example, if parks were the GI type, and pest control was the ES, a participant who thought that parks harbored pests might provide negative linkage value in this box of the matrix. The mean linkage value, termed the average GI-ES linkage (AGEL), was calculated for each matrix cell based on the linkage values given by participants who reported being “confident” or “very confident” in evaluating the respective ES. Variance was also calculated for each cell. The statistical differences in AGEL scores across GI categories and ES categories were determined using Mann–Whitney non-parametric U tests (p < 0.05).

Field of study

Participants were asked to report their primary area of expertise. Two of the workshop facilitators also independently categorized each participant’s expertise as applied science, natural science, social science, or other (intercoder correlation r = 0.91). The field of study information was used to determine whether there were differences in GI-ES linkages and confidence between disciplines.

Results

Green infrastructure and ecosystem service linkages

The average GI-ES linkages of various green infrastructure types were assessed using the correlation values associated with high confidence (“3” or “4”) from the 46 complete matrix surveys. Table 2 shows the average GI-ES linkage for each cell with the highest, positive values at the top left and the lowest or negative values at the bottom right. An annotated version of this chart with the number of highly confident responses used to determine the AGEL’s is available in Appendix S3.

Table 2.

The participant AGEL scores between 14 Green Infrastructure types and 22 Ecosystem Services. Green infrastructure typologies are presented in descending order (from top to bottom) of how positively expert judgement linked them to ecosystem services. Similarly, ecosystem services, and their overarching categories, are presented in descending order (right to left) of how well expert judgement linked them to GI. *Cultural ES, +RSM ES, ♢ Provisioning ES

In general, the experts evaluated GI positively through the lens of ecosystem services with 35 highly positively linked cells (AGEL of 2 to 3), 117 positively linked cells (AGEL of 1 to 2), 114 modestly positively linked cells (AGEL of 0 to 1), 39 modestly negatively linked cells (AGEL of 0 to − 1), 3 negatively linked cells (AGEL of − 1 to − 2), and no highly negative cells (AGEL of − 2 to − 3). The mean of all AGEL scores is 0.95.

Ecosystem services

The most positive ecosystem services are Water Quantity Mitigation (avg. AGEL of 1.70), Science and Education (avg. AGEL of 1.64), Habitat Supporting (avg. AGEL of 1.36), and Spiritual, Cultural, and Aesthetic (avg. AGEL of 1.33) while Pest Control is found to be the only consistently negative linkage, or disservice provided by GI.

Categorically, expert judgement of Cultural Services shows them to be most universally provided by GI (avg. AGEL of 1.29) followed by Regulating, Supporting, and Maintenance Services (avg. AGEL of 0.94) and finally Provisioning Services (avg. AGEL of 0.64). Table 3 reports individual AGEL scores for Cultural Services across all GI types.

Table 3.

Average Green Infrastructure Ecosystem Service Linkage (AGEL) of “confident” and “highly confident” participants along with the average variance within the same pool of participants for Cultural Ecosystem Services

| Cultural Ecosystem Services | Average AGEL across all GI | Average participant variance |

|---|---|---|

| Science and education | 1.64 | 0.30 |

| Spiritual, cultural, and aesthetic | 1.33 | 0.93 |

| Social interaction | 1.19 | 0.79 |

| Recreation and tourism | 1.08 | 0.89 |

Science and Education topped the Cultural Services with varying degrees of positive linkages across GI types and lowest average variance (0.30) among respondents. Social Interaction and Spiritual, Cultural, and Aesthetic services are found to be highly positively linked with Parks and Community Gardens and only negatively linked to Vacant Land. Recreation and Tourism services are the least positively linked to GI although still, on average, have a modest positive rating.

Regulating, Supporting, and Maintenance Services were also viewed as generally benefitted by GI (avg. AGEL of 0.94); however, this category exhibited large variation between GI-ES expert judgement, including both the most positive linkage, Water Quantity Mitigation, and the most negative linkage, Pest Control, reported in Table 4.

Table 4.

Average Green Infrastructure Ecosystem Service Linkage (AGEL) of “confident” and “highly confident” participants along with the average variance within the same pool of participants for Regulating, Supporting, and Maintenance Ecosystem Services

| Regulating, Supporting, and Maintenance Ecosystem Services | Average AGEL across all GI | Average participant variance |

|---|---|---|

| Water Quantity Mitigation | 1.70 | 0.41 |

| Habitat Supporting | 1.36 | 0.57 |

| Climate Regulation | 1.28 | 0.42 |

| Pollination | 1.27 | 0.72 |

| Air Purification | 1.15 | 0.51 |

| Nutrient Cycling | 1.11 | 0.46 |

| Water Quality Improvement | 1.00 | 0.32 |

| Erosion Control/Prevention | 0.98 | 0.39 |

| Mitigation of Natural Disaster | 0.98 | 0.25 |

| Soil Formation | 0.83 | 0.48 |

| Water Conservation | 0.74 | 0.45 |

| Noise Reduction | 0.66 | 0.37 |

| Pest Control | − 0.34 | 0.36 |

Provisioning Services are the least linked to GI (avg. AGEL of 0.64) with the exception of a few highly positively linked cells such as Ornamental Resources linked to Parks and Community Gardens and Food Production linked to Community Gardens and Rain Barrels, reported in Table 5.

Table 5.

Average Green Infrastructure Ecosystem Service Linkage (AGEL) of “confident” and “highly confident” participants along with the average variance within the same pool of participants for Provisioning Ecosystem Services

| Provisioning Ecosystem Service | Average AGEL across all GI | Average participant variance |

|---|---|---|

| Ornamental resources | 1.28 | 0.71 |

| Water supply | 0.76 | 0.51 |

| Food production/food supply | 0.56 | 0.29 |

| Raw material | 0.18 | 0.11 |

| Medicinal resources | 0.14 | 0.11 |

Green infrastructure

Ranking the GI types by expert judgement of their ability to provide ES reveals groupings similar to the general land use categories introduced in “Ecosystem services” section. For example, expert judgement of the three most beneficial GI types with respect to ES are Parks (avg. AGEL of 1.75), Wetlands (avg. AGEL of 1.55), and Community Gardens (avg. AGEL of 1.43), all within the Vegetated Land category. Conversely, two of the three lowest ranked GI types are Cisterns/Rain Barrels (avg. AGEL of 0.45) and Permeable Paving (avg. AGEL of 0.39) together, constituting Non-vegetated Stormwater GI. Vacant Land (avg. AGEL of 0.24) is the lowest ranked GI type which may be attributed to overall negative judgement about vacant land in the context of urban landscapes.

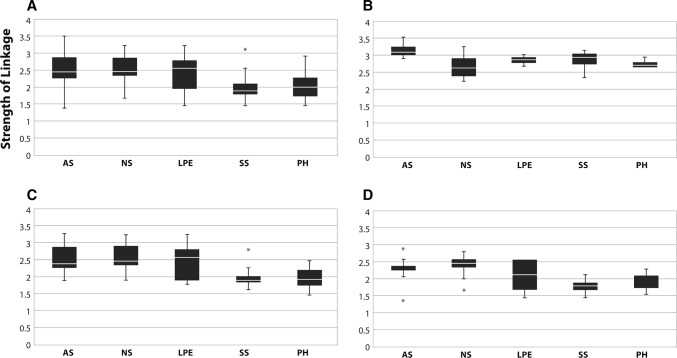

The difference between the expert judgement for the ability of Vegetated Land, Vegetated Stormwater GI, and Non-vegetated Stormwater GI to provide Provisioning, Regulating, Supporting, and Maintenance, and Cultural services is illustrated in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Box-plots of the AGEL scores for GI grouped into three functional categories: vegetated land (parks, wetlands, and community gardens), vegetated stormwater GI (intensive green roofs, extensive green roofs, bioswales and green streets, detention and retention ponds, and rain gardens), and non-vegetated stormwater GI (permeable paving, and cisterns and rain barrels). Within each type of ecosystem service (provisioning, regulating, supporting, and cultural), the statistical difference between GI categories, as determined using Mann–Whitney non-parametric U tests (p < 0.05), is annotated with letters (A, AB, B, C)

Across all three ES categories, Vegetated Land has the highest average linkage. Non-vegetated Stormwater GI has the lowest average linkage regarding Cultural and Regulating, Supporting, and Maintenance services, and a significantly lower linkage than Vegetated Land regarding Provisioning services. While statistically significant in all categories, the difference in service provision between the GI categories is most pronounced in the Cultural ES category.

Disciplinary confidence and variance

Table 6 reports the average confidence in ES assessment (range from 1 to 4) for the different disciplines represented in the workshops, while Fig. 3 illustrates results in a graphical format.

Table 6.

The average confidence in Ecosystem Service (ES) assessment and variance among their reported ES-GI linkages by the disciplines represented. Cells are shaded corresponding to their value (darker is higher). Ecosystem services and their corresponding categories of Cultural (C), Regulating, Supporting, and Maintenance (RSM), and Provisioning (P), are presented in descending order (from top to bottom) of the average participant pool confidence

In general, our pool of participants across all disciplines are most confident about Cultural ecosystem services, followed by Regulating, Supporting, and Maintenance, and Provisioning. Participants in the applied sciences reported the highest mean confidence (MC = 2.55) and lowest variance in responses (Var = 0.55). Natural science participants are slightly less confident (MC = 2.53, Var = 0.83) than applied science; however, a Mann–Whitney U failed to show a significant difference in their distributions (p = 0.40). Participants from the social sciences reported the lowest confidence scores (MC = 2.06) in addition to having the highest variance (Var = 1.09). Confidence scores from social science participants are significantly lower than those from participants with an applied science or natural science backgrounds (both p < 0.001).

In general, participants from social sciences and public health reported the lowest AGEL considering all services (Fig. 4, subplot A). The difference between disciplinary AGEL scores for Cultural Services (Fig. 4, subplot B) is the lowest and all disciplines scored them significantly higher than RSM (Fig. 4, subplot C) or Provisioning (Fig. 4, subplot D).

Fig. 4.

Average Green Infrastructure Ecosystem Service Linkage (AGEL) for all services (A) Cultural Services (B) Regulating, Supporting, and Maintenance Services (C) and Provisioning Services (D); AS: Applied Sciences; NS: Natural Sciences; LPE = Law, Policy, Economics, SS: Social Sciences; PH: Public Health

Discussion

The judgements presented here suggest that academic experts agree that GI types differ in their ability to provide specific ES. In particular, non-vegetated stormwater GI is ranked as particularly poor at providing co-benefits, while larger vegetated spaces, specifically those that are easy to interact with (e.g., Parks and Community Gardens), are ranked as providing the strongest co-benefits. The variation suggested here highlights the importance of distinguishing between GI types in planning frameworks that attempt to incorporate GI benefits beyond stormwater management.

In addition to finding significant variation in ES linkages between GI types, the experts’ judgement indicate the relative importance of Cultural Services as a GI co-benefit, which is contrasted with the under-representation of these benefits in planning, evaluation, and research. While the average benefit of Cultural Services is highest among the experts participating in our study, our literature review found them to be the least empirically and spatially investigated on a landscape scale (Crossman et al. 2013; Ziter 2015) and included in 15% of peer-reviewed papers on urban ecosystem services (Haase et al. 2014). This could, in part, be due to green space in urban areas providing disproportionately high amounts of Cultural Services when compared to rural areas (Chang et al. 2017). Cultural Services are also more easily detected by the average urban inhabitant, providing more opportunities for direct observation and experience, unlike other valuable services, which are often invisible without an advanced knowledge of ecological processes (Andersson et al. 2015). Regardless, the simultaneous under-representation of Cultural Services in ES research, their increasing relevance to urban green space planning (Wu 2014; Andersson et al. 2015; Bertram and Rehdanz 2015; Riechers et al. 2016; Dickinson 2017), and their importance as judged by experts related to Urban GI present a potential discrepancy, and further validate assertions (Andersson et al. 2015; Chang et al. 2017) for more advanced research on the integration of the Cultural Services provided by urban GI. Because it is the Cultural Services that are more likely to impact people’s experiences and engagement with the urban landscape, a better understanding of their linkages to the less visible ecological processes and services is necessary for long-term sustainability (Nassauer 2011). This point might be of particular relevance to the development of stewardship programs for urban GI, which can enhance individual knowledge and care of the environment and whose success might rely more on public perception of the Cultural Services provided by GI than other ES categories (Nassauer 2011; Andersson et al. 2014, 2015).

We suggest that our work supports the use of expert opinion to advance holistic GI planning for cities and offer some observations about methodological approaches to this question. The experience of running five workshops with various groups garnered several insights. First, the conversational workshop approach in which participants were encouraged to speak seemed to mitigate the respondent fatigue associated with large surveys (Kenter et al. 2015) and allowed for participants to deliberate and to gain new insights on the topics. For reference, a conversation map is available in Appendix S4 that highlights the topics discussed, general conversation flow, and participant feedback on simultaneous discussion and data entry. Second, we credit the strong attendance at our workshops to targeting pre-existing groups and holding workshops during their regularly scheduled meeting times, effectively addressing the difficulty of recruitment attendance reported by Kopperoinen et al. (2014).

Limitations

There are several general limitations inherent to using expert elicitation. Also, this study’s application is limited by its exclusive use of experts within academia, the NYC context of evaluation, and our workshop methodology.

First, expert elicitation requires individuals who, based on educational, professional, or personal experiences, can be trusted to evaluate a certain subject. The participants in our study are considered experts due to their formal education in environmental sustainability. While they represent many knowledge areas, the study lacks individuals who derived their expertise outside of an academic setting. For many of the ecosystem services, particularly cultural ones, people with direct experience with the benefits of services (e.g., residents, park managers, block association members) might be better suited to assess service value provision. As any model is only as good as the data it is based on, we urge caution in broadly applying the linkages reported here, and underscore that they are the aggregate judgement of 46 individuals in a university setting. Thus, the reported linkages should be viewed as one source in a multiple evidence-based approach, as recommended by Tengö et al. (2014).

The AGEL scores were determined for a NYC context and thus should be applied to the context of other cities with caution. Different urban areas might have distinct ecosystem service potential and needs, although, as other NYC case studies have demonstrated, NYC-based ecosystem service assessments can offer translatable tools, methods, and lessons along with local results that contribute to understanding ecosystem service management in cities more broadly (McPhearson et al. 2013; Connolly et al. 2014). In particular, repeating the workshop methodology described here with other expert groups, across other cities, and incorporating quantitative indicators would help further legitimize and determine the scope of our reported GI-ES linkages for their use in planning (Jacobs et al. 2015).

In addition to the recommended practices that were identified through workshop design and facilitation, we also recognize several areas where our methodology may have negatively impacted the quality of the output. At the beginning of each workshop, we introduced each type of GI and ES, and while we attempted to remain as factual as possible, we may have imparted some of our own subjective views onto the respondents’. We believe that a priming activity is valuable to ensure a common vocabulary; however, a video or written material would be less susceptible to unintentionally communicating biases.

Additionally, we received participant feedback that the size and resolution of the matrix and Likert scale were cumbersome. We believe our approach could be simplified on both counts without significant loss in data resolution. The matrix could be truncated by combining structures that are physically similar and do not have significantly different ES supply capacities (Jacobs et al. 2015), while the Likert scale could be reduced from 7 inputs (− 3 to + 3) to 5 inputs (− 2 to + 2). The scale as we presented it, additionally caused confusion in some participants. Some participants sought to create their own entry type of ± 0.1 to represent a “linked, but minor significance” category. We would recommend for that to occupy a + 1 or − 1 score on a 5-point scale. Additionally, participants sought a better understanding of a reference structure for a linkage of 0. We would recommend providing a familiar reference structured for each ES as opposed to the baseline of “typical urban fabric” that we offered.

The use of a large matrix to capture expert judgement created a notable participant burden that led us to run the workshop only one time with each expert. This limitation precluded the use of additional workshops to convene confident participants with varying viewpoints, to debate their stances and potentially lead to a stronger consensus or a more detailed understanding of differences in expert judgement. In particular, we would recommend using the reduced matrix and 5-point Likert scale in an iterative workshop approach, such as the Delphi Method, to help experts “converge” on structure–service correlations, as recommended by Jacobs et al. (2015).

Conclusion

As urban areas continue to grow, there is increased pressure to develop infrastructural solutions that are sustainable for humans and the environment. While urban green infrastructure planning is primarily motivated by stormwater management in compliance with federal regulations, its widespread implementation and public support are often part of a larger strategy that acknowledges an array of social and environmental co-benefits, many of which have been formalized as ecosystem services. To allow ES to serve as a framework to evaluate different types of GI and their co-benefits, it is important to value the services and translate the aggregate effect into a holistic strategy for location-specific GI planning, but this remains a major challenge.

This study presented an analysis of the linkages between ES and urban GI through the use of 5 interdisciplinary workshops. In the workshops, participants, who were researchers at Columbia University engaged in work relevant to urban sustainability, provided their expert opinions of linkages between ES and urban GI. The resultant matrix model that was generated provided a full suite of correlation values between GI and ES, with high correlation values indicating that a GI type is a very positive provider of an ES and a strong, negative value indicating that a GI type is a very negative detriment of that ES. The matrix model clearly demonstrated the experts’ judgment of hierarchy for urban green infrastructures and their associated services. Notably, expert judgement of the ability for different structures to provide co-benefits was highly varied. The highest performing structures, in terms of high, positive correlation values with ES, consisted of larger green spaces, which are not universally considered as a means for stormwater management (Parks, Community Gardens, and Wetlands), while the least beneficial structures included non-vegetated systems designed strictly for stormwater (Permeable Paving, Cisterns, and Rain Barrels) and Vacant Land. These findings highlight the challenges of using an inclusive definition of the term green infrastructure in the context of ES benefits, as ecosystem service provision across different GI types is not uniform.

Stormwater quantity mitigation, a Regulating, Supporting, and Maintenance Service, was found to be the most positively linked individual service to urban GI. However, when comparing aggregated ES categories, participants from all disciplinary backgrounds ranked Cultural Services highest. Cultural Services, defined by MEA as “the nonmaterial benefits people obtain from ecosystems” (MEA 2005), are often considered “intangible,” “subjective,” and dependent on varying non-mapped social constructs (Daniel et al. 2012). In turn, these qualities prevent their legitimate integration into formal infrastructure planning, which necessitates a quantitative, physical, and objective approach. However, if planners are to use ES as justification for siting GI, the consideration of Cultural Services cannot be ignored as all ES Frameworks include these services.

One recommended solution to the holistic application of ES to GI planning would be to consider the city-scale infrastructural goals and local-scale cultural impacts separately. First, GI as physical infrastructure could be cited on a sewershed scale based on stormwater management needs, along with other physically based RSM and Provisioning Services. Second, the local articulation of site-specific GI would require the consideration of physical features in the built environment that pose opportunities or constraints to design scenarios. As part of a finer-scale analysis, planners, designers, and decision makers would work with the locality to design and implement GI components that consider a community’s cultural service needs, stewardship ability, and social constructs. The “safe-to-fail” adaptive planning for urban GI, put forth by Ahern et al. (2014), provides a concrete framework for collaborative design at this scale.

The results of our study are intended to function as a set of preliminary reference materials that can be used in the development of holistic planning models or tools incorporating GI for its ES provision potential. It provides a starting point for validating the structure–service relationships that are often explicitly stated or implicitly assumed in planning and decision-making.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded, in part, by the National Science Foundation (NSF) Integrative Graduate Education and Research Training (IGERT) Fellowship #DGE-0903597, NSF Coastal SEES Award #1325676 and NSF Sustainability Research Networks Award #1444745: “Integrated Urban Infrastructure Solutions for Environmentally Sustainable, Healthy, and Livable Cities.” Furthermore, Robert Elliott gratefully acknowledges the support of The Earth Institute’s Postdoctoral Fellowship Program. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions expressed in this letter are those of the author and not meant to represent the views of any supporting institution.

Biographies

Robert M. Elliott

Ph.D., is adjunct faculty in the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences at Columbia University and Co-Founder of Urban Leaf. His research interests include next generation green infrastructure—exploring new types of vegetation systems, incorporated feedback loops, and determining ideal placement for stormwater mitigation, wildlife creation, air quality improvement, and temperature reduction.

Amy E. Motzny

is the Watershed Manager for the Gowanus Canal Conservancy, a Brooklyn-based community organization dedicated to facilitating the development of a resilient, vibrant, open space network centered on the Gowanus Canal. She holds a Master of Landscape Architecture from the University of Michigan as well as a B.S. in Environmental Science and Spatial Information Processing. As a research scientist and teaching fellow with Columbia University’s Earth Institute, she has conducted extensive research on urban green infrastructure planning and design strategies that provide ecosystem services and socio-cultural benefits to communities.

C. Sudy Majd

Ph.D., is a Customer Experience Research Lead at Candid Co. Her doctoral research in the Department of Psychology at Columbia University was on consumer behavior with a expertise in changing the behaviors of eating behaviors of individuals through the built environment and interventions. She was the first to apply specific behavioral economic models and cognitive behavioral theories to the issue of overconsumption and unhealthy food choices.

Filiberto J. Viteri Chavez

is a licensed architect in Ecuador and an Associate Professor at Universidad Católica de Santiago de Guayaquil. His research interests are in the public space aspects of community development, as well as education systems connected to architecture, design, and urbanism.

Daniel Laimer

is Landscape Designer at Capatti Staubach in Berlin. His research interests are in community involvement and participatory design practices for urban design projects.

Benjamin S. Orlove

Ph.D., is a Professor of International and Public Affairs at Columbia University. His research interests are in climate change adaptation, environmental anthropology, human response to glacier retreat in mountain regions, water management and governance, natural hazards and disaster risk reduction, and urban sustainability.

Patricia J. Culligan

Ph.D., is a Professor in the Department of Civil Engineering & Engineering Mechanics at Columbia University. Her work explores novel, interdisciplinary solutions to the challenges of urbanization, with a particular emphasis on the City of New York. Her research investigates the opportunities for green infrastructure, social networks, and advanced measurement and sensing technologies to improve urban water, energy, and environmental management.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Robert M. Elliott, Email: rme2123@columbia.edu, Email: rob.m.elliott@gmail.com

Amy E. Motzny, Email: am4502@columbia.edu, Email: amy@gowanuscanalconservancy.org

Sudy Majd, Email: cm2125@columbia.edu, Email: sudy.majd@gmail.com.

Filiberto J. Viteri Chavez, Email: fjv2111@columbia.edu.

Daniel Laimer, Email: dl2938@columbia.edu.

Benjamin S. Orlove, Email: bso5@columbia.edu

Patricia J. Culligan, Email: pjc2104@columbia.edu

References

- Ahern J, Cilliers S, Niemelä J. The concept of ecosystem services in adaptive urban planning and design: a framework for supporting innovation. Landscape and Urban Planning. 2014;125:254–259. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2014.01.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson E, Barthel S, Borgström S, Colding J, Elmqvist T, Folke C, Gren Å. Reconnecting cities to the biosphere: Stewardship of green infrastructure and urban ecosystem services. Ambio. 2014;43:445–453. doi: 10.1007/s13280-014-0506-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson E, Tengö M, McPhearson T, Kremer P. Cultural ecosystem services as a gateway for improving urban sustainability. Ecosystem Services. 2015;12:165–168. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoser.2014.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benedict MA, McMahon ET. Green infrastructure: Smart conservation for the 21st century. Renewable Resources Journal. 2002;20:12–19. doi: 10.4135/9781412973816.n70. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bertram C, Rehdanz K. Preferences for cultural urban ecosystem services: Comparing attitudes, perception, and use. Ecosystem Services. 2015;12:187–199. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoser.2014.12.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bolund P, Hunhammar S. Ecosystem services in urban areas. Ecological Economics. 1999;29:293–301. doi: 10.1016/S0921-8009(99)00013-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brauman K, Daily G, Duarte T, Mooney H. The nature and value of ecosystem services: An overview highlighting hydrologic services. Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 2007;32:67. doi: 10.1146/annurev.energy.32.031306.102758. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhard B, Kroll F, Müller F, Windhorst W. Landscapes’ capacities to provide ecosystem services—A concept for land-cover based assessments. Landscape Online. 2009;15:1–22. doi: 10.3097/LO.200915. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campagne CS, Roche P, Gosselin F, Tschanz L, Tatoni T. Expert-based ecosystem services capacity matrices: Dealing with scoring variability. Ecological Indicators. 2017;79:63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2017.03.043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chang J, Qu Z, Xu R, Pan K, Xu B, Min Y, Ren Y, Yang G, et al. Assessing the ecosystem services provided by urban green spaces along urban center-edge gradients. Scientific Reports. 2017;7:11226. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-11559-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chon J, Shafer CS. Aesthetic responses to urban greenway trail environments. Landscape Research. 2009;34:83–104. doi: 10.1080/01426390802591429. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- City of Chicago . 2014 budget overview. Chicago, IL: City of Chicago; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Connolly JJT, Svendsen ES, Fisher DR, Campbell LK. Networked governance and the management of ecosystem services: The case of urban environmental stewardship in New York City. Ecosystem Services. 2014;10:187–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoser.2014.08.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- CRED. 2017. Center for Research on Environmental Decisions. https://www.cred.columbia.edu.

- Crossman ND, Burkhard B, Nedkov S, Willemen L, Petz K, Palomo I, Drakou EG, Martin-Lopez B, et al. A blueprint for mapping and modelling ecosystem services. Ecosystem Services. 2013;4:4–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoser.2013.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Daily GC, Polasky S, Goldstein J, Kareiva PM, Mooney HA, Pejchar L, Ricketts TH, Salzman J, et al. Ecosystem services in decision making: Time to deliver. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. 2009;7:21–28. doi: 10.1890/080025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel TC, Muhar A, Arnberger A, Aznar O, Boyd JW, Chan KMA, Costanza R, Elmqvist T, et al. Contributions of cultural services to the ecosystem services agenda. PNAS. 2012;109:8812–8819. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114773109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson DC, Hobbs RJ. Cultural ecosystem services: Characteristics, challenges and lessons for urban green space research. Ecosystem Services. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.ecoser.2017.04.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbs C, Escobedo FJ, Zipperer WC. A framework for developing urban forest ecosystem services and goods indicators. Landscape and Urban Planning. 2011;99:196–206. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2010.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Florida Greenways Commission . Creating a statewide Greenways system, for people… for wildlife… for Florida. Tallahassee: Florida Greenways Commission; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Getter KL, Rowe DB, Robertson GP, Cregg BM, Andresen JA. Carbon sequestration potential of extensive green roofs. Environmental Science and Technology. 2009;43:7564–7570. doi: 10.1021/es901539x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Baggethun E, Ruiz-Pérez M. Economic valuation and the commodification of ecosystem services. Progress in Physical Geography. 2011;35:613–628. doi: 10.1177/0309133311421708. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Baggethun E, Barton DN. Classifying and valuing ecosystem services for urban planning. Ecological Economics. 2013;86:235–245. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2012.08.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haase D, Larondelle N, Andersson E, Artmann M, Borgström S, Breuste J, Gomez-Baggethun E, Gren Å, et al. A quantitative review of urban ecosystem service assessments: Concepts, models, and implementation. Ambio. 2014;43:413–433. doi: 10.1007/s13280-014-0504-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haines-Young, R. and M. Potschin. 2013. Common International Classification of Ecosystem Services (CICES). EEA Framework Contract No: EEA/IEA/09/003.

- Hansen R, Pauleit S. From multifunctionality to multiple ecosystem services? A conceptual framework for multifunctionality in green infrastructure planning for urban areas. Ambio. 2014;43:516–529. doi: 10.1007/s13280-014-0510-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hathout M, Vuillet M, Peyras L, Carvajal C, Diab Y. Uncertainty and expert assessment for supporting evaluation of levees safety. European Conference on Flood Risk Management. 2016;7:10. doi: 10.1051/e3sconf/20160703019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoornbeek J, Schwarz T. Sustainable infrastructure in shrinking cities: Options for the future. Progress in Planning. 2009;72:223–232. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs S, Keune H, Vrebos D, Beauchard O, Villa F, Meire P. Ecosystem service assessments: Science or pragmatism? In: Jacobs S, Dendoncker N, Keune H, editors. Ecosystem services. Boston: Elsevier; 2013. pp. 157–165. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs S, Burkhard B, Van Daele T, Staes J, Schneiders A. “The Matrix Reloaded”: A review of expert knowledge use for mapping ecosystem services. Ecological Modelling. 2015;295:21–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2014.08.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jayasooriya VM, Ng AWM. Tools for modeling of stormwater management and economics of green infrastructure practices: A review. Water, Air, and Soil pollution. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s11270-014-2055-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jin S, Guo J, Wheeler S, Kan L, Che S. Evaluation of impacts of trees on PM2.5 dispersion in urban streets. Atmospheric Environment. 2014;99:277–287. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2014.10.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser G, Burkhard B, Römer H, Sangkaew S, Graterol R, Haitook T, Sterr H, Sakuna-Schwartz D. Mapping tsunami impacts on land cover and related ecosystem service supply in Phang Nga, Thailand. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences. 2013;13:3095–3111. doi: 10.5194/nhess-13-3095-2013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kenter JO, O’Brien L, Hockley N, Ravenscroft N, Fazey I, Irvine KN, Reed MS, Christie M, et al. What are shared and social values of ecosystems? Ecological Economics. 2015;111:86–99. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.01.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr RA. Risk assessment—A new way to ask the experts: Rating radioactive waste risks. Science. 1996;274:913–914. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5289.913. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kopperoinen L, Itkonen P, Niemelä J. Using expert knowledge in combining green infrastructure and ecosystem services in land use planning: An insight into a new place-based methodology. Landscape Ecology. 2014;29:1361–1375. doi: 10.1007/s10980-014-0014-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McPhearson T, Kremer P, Hamstead ZA. Mapping ecosystem services in New York City: Applying a social-ecological approach in urban vacant land. Ecosystem Services. 2013;5:11–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoser.2013.06.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson GE, Simpson JR, Xiao Q, Wu C. Million trees Los Angeles canopy cover and benefit assessment. Landscape and Urban Planning. 2011;99:40–50. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2010.08.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meerow S, Newell JP. Spatial planning for multifunctional green infrastructure: Growing resilience in Detroit. Landscape and Urban Planning. 2017;159:62–75. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2016.10.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment . Ecosystems and human well-being: Synthesis. Washington, DC: Island Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Müller F, de Groot R, Willemen L. Ecosystem services at the landscape scale: The need for integrative approaches. Landscape Online. 2010;23:1–11. doi: 10.3097/LO.201023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nassauer JI. Care and stewardship: From home to planet. Landscape and Urban Planning. 2011;100:321–323. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2011.02.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- NEORSD (Northeast Ohio Regional Sewer District). Green infrastructure plan. Cleveland: NEORSD; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Newell JP, Seymour M, Yee T, Renteria J, Longcore T, Wolch JR, Shishkovsky A. Green alley programs: Planning for a sustainable urban infrastructure? Cities. 2013;31:144–155. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2012.07.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Norton BA, Coutts AM, Livesley SJ, Harris RJ, Hunter AM, Williams NSG. Planning for cooler cities: A framework to prioritise green infrastructure to mitigate high temperatures in urban landscapes. Landscape and Urban Planning. 2015;134:127–138. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2014.10.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- NYC Mayor’s Office. 2010. NYC Green Insfrastructure Plan: A sustainable strategy for clean waterways. New York: NYC Mayor’s Office. http://www.nyc.gov/html/dep/pdf/green_infrastructure/NYCGreenInfrastructurePlan_LowRes.pdf.

- Orlove, B. 2016. Columbia School of International and Public Affairs. https://sipa.columbia.edu/faculty-research/faculty-directory/ben-orlove.

- Philadelphia Water Department . Green City Clean Waters. Philadelphia, PA: Philadelphia Water Department; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pugh TAM, Mackenzie AR, Whyatt JD, Hewitt CN. Effectiveness of green infrastructure for improvement of air quality in urban street canyons. Environmental Science and Technology. 2012;46:7692–7699. doi: 10.1021/es300826w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riechers M, Barkmann J, Tscharntke T. Perceptions of cultural ecosystem services from urban green. Ecosystem Services. 2016;17:33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoser.2015.11.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Riveiro M. Visually supported reasoning under uncertain conditions: Effects of domain expertise on air traffic risk assessment. Spatial Cognition & Computation. 2016;16:133–153. doi: 10.1080/13875868.2015.1137576. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robert B. A method for the study of cascading effects within lifeline networks. International Journal of Critical Infrastructures. 2004;1:86–99. doi: 10.1504/IJCIS.2004.003798. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schilling J, Logan J. Greening the rust belt: A green infrastructure model for right sizing America’s shrinking cities. Journal of the American Planning Association. 2008;74:451–466. doi: 10.1080/01944360802354956. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schröter M, van der Zanden EH, van Oudenhoven APE, Remme RP, Serna-Chavez HM, de Groot RS, Opdam P. Ecosystem services as a contested concept: A synthesis of critique and counter-arguments. Conservation Letters. 2014 doi: 10.1111/conl.12091. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson RD. The “ecosystem service framework”: A critical assessment. Nairobi: The United Nations Environment Programme; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Stoll S, Frenzel M, Burkhard B, Adamescu M, Augustaitis A, Baeßler C, Bonet FJ, Laura Carranza M, et al. Assessment of ecosystem integrity and service gradients across Europe using the LTER Europe network. Ecological Modelling. 2015;295:75–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2014.06.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sustainability Research Network . Integrated urban infrastructure solutions for environmentally sustainable, health and livable cities. Champaign: Sustainability Research Network; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- TEEB . The economics of ecosystems and biodiversity ecological and economic foundations. London: Earthscan; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tengö M, Brondizio ES, Elmqvist T, Malmer P, Spierenburg M. Connecting diverse knowledge systems for enhanced ecosystem governance: The multiple evidence base approach. Ambio. 2014;43:579–591. doi: 10.1007/s13280-014-0501-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzoulas K, Korpela K, Venn S, Ylipelkonen V, Kazmierczak A, Niemela J, James P. Promoting ecosystem and human health in urban areas using Green Infrastructure: A literature review. Landscape and Urban Planning. 2007;81:167–178. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2007.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations . World urbanisation prospects the 2011 revision. New York: World Urbanisation Prospects, Department of Economic and Social Affairs; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- UPHI. 2017. Urban health initiative. https://www.mailman.columbia.edu/research/urbanhealth-initiative.

- Urban Design Lab. 2016. Developing high performance green infrastructure systems. www.urbandesignlab.columbia.edu/projects/coastal-cities-resiliency/developing-high-performance-green-infrastructure-systems/.

- US EPA . EPA greening CSO plans: Planning and modeling green infrastructure for combined sewer overflow (CSO) control. Washington, DC: US EPA; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Vihervaara P, Kumpula T, Tanskanen A, Burkhard B. Ecosystem services—A tool for sustainable management of human–environment systems. Case study Finnish Forest Lapland. Ecological Complexity. 2010;7:410–420. doi: 10.1016/j.ecocom.2009.12.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J. Urban ecology and sustainability: The state-of-the-science and future directions. Landscape and Urban Planning. 2014;125:209–221. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2014.01.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ziter C. The biodiversity–ecosystem service relationship in urban areas: A quantitative review. Oikos. 2015;125:761–768. doi: 10.1111/oik.02883. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.