Graphical abstract

Keywords: Adsorption, Uranium, Flax fiber, Recovery, Yellow cake

Highlights

-

•

Removal and recovery of uranium were investigated in a batch process.

-

•

Adsorbent characteristics were scientifically analyzed.

-

•

The maximum obtained U(VI) removal was ≈94.50% at pH of 4 and adsorbent dose of 1.2 g.

-

•

Adsorption data were analyzed using kinetic, isotherm and thermodynamic models.

-

•

Full scale batch adsorber unit was recommended.

Abstract

Flax fiber (Linen fiber), a valuable and inexpensive material was used as sorbent material in the uptake of uranium ion for the safe disposal of liquid effluent. Flax fibers were characterized using BET, XRD, TGA, DTA and FTIR analyses, and the results confirmed the ability of flax fiber to adsorb uranium. The removal efficiency reached 94.50% at pH 4, 1.2 g adsorbent dose and 100 min in batch technique. Adsorption results were fitted well to the Langmuir isotherm. The recovery of U (VI) to form yellow cake was investigated by precipitation using NH4OH (33%). The results show that flax fibers are an acceptable sorbent for the removal and recovery of U (VI) from liquid effluents of low and high initial concentrations. The design of a full scale batch unit was also proposed and the necessary data was suggested.

Introduction

Environmental pollution is deemed one of most serious issues that should be taken care of due to its catastrophic influences on human health and environment [1]. Therefore, many countries have paid considerable attention to avert or treat environmental pollution [2], [3]. Pollutants of water and waste water industries such as heavy metals have been treated using different physical and chemical processes. Compared to all the different wastewater industries, water containing radioactive pollutants (uranium and thorium) is the most dangerous wastewater. Thus, researchers are still investigating different methods to remove radioactive elements from liquid wastes for safe disposal [4], [5], [6]. Uranium (U) is a very significant toxic and radioactive element that is utilized in many nuclear applications. However, it has negative effects on the environment and needs to be removed from radioactive waste water[7]. Uranium from nuclear industrial processes seeps into the environment, pollutes water or soil and enters plants and from comes in contact with human bodies, causing severe damage to the kidneys or liver that lead to death [8]. Various processes, such as precipitation, evaporation, ion exchange, liquid-liquid extraction, membrane separation [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], have been used to treat the radioactive liquid wastes. However, these methods are not successful or cost-effective, especially when dealing with the great volumes of liquid waste includes low concentrations of radioactive pollutants [14]. For that reason, many researchers considered adsorption to be one of the most efficient processes to treat this limits of pollutants. Adsorption process has been considered to be an advantageous technique (simple construction and operation) and it uses a variety of adsorbent materials such as modified rice stem [15], codoped graphene [16], nanogoethite powder [17], iron/magnetite carbon composites [18] and sporangiospores of mucor circinelloides [19], to adsorb pollutants from the liquid phase. Flax fibers are obtained from agriculture as a by-product. It is composed of fibers, cellulose, hemicelluloses, lignin containing functional groups in their chemical composition such as carboxyl, hydroxyl group which have a major role in facilitating adsorption processes. The current work, deals with the treatment of high concentrations of uranium ions discharged from nuclear processes (mining, nuclear fuel manufacture and application), which must be treated to the lowest concentration before being transferred to the relevant processing units such as the Hot Labs Center, Atomic Energy Authority, Cairo. In this research, the focus was on the use of natural degradation materials such as flax fibers to remove and recover the U element from the liquid wastes. The factors affecting the batch sorption(pH, sorbent dose, initial feed concentration, contact time, and temperature) were optimized and the results were evaluated using isotherm and kinetics models.

Materials & methods

Materials

Flax fiber was obtained from flax industry, Tanta, Egypt. Flax fiber was prepared as follows: they were cut into <3–5 mm pieces and washed by hot water many times to remove wax and foreign matters. Washing was continued until all contaminants were removed and clear water was obtained. After that, flax fibers were dried at 378 K to dry the fibers. Liquid samples of experiments were prepared from uranyl acetate (UO2(OCOCH3)2·6H2O). Feed and finial uranium concentrations (mg/l) were determined spectrophotometrically (Shimadzu UV–VIS-1601 spectrophotometer) using arsenazo (III) [20]. All chemicals and reagents used in this research were analytical grades.

Methods

To study the adsorption performance of the prepared flax fibers, sorption of U (VI) ions was investigated in a batch system. A known weight of adsorbent was agitated at 250 rpm with 60 mL uranium sample in a thermostatic shaker water bath of type (Julabo, Model SW −20 °C, Germany) at different conditions (Table 2). 0.1 M HNO3 or 0.1 M NH4OH solutions were utilized to adjust pH (Metrohm E-632, Heisau, Switzerland). The fiber was separated by filter paper and the sample was spectrophotometrically analyzed. Maximum uptake capacity qe (mg/g) and adsorption percent [R (%)] were determined by following equations.

| (1) |

| (2) |

Table 2.

Parameters of U (VI) uptake by flax fiber.

| Parameter | Removal percent (R %) | |

|---|---|---|

| pH: | 2.0 | 42.32 |

| (Conditions: 700 mg/l, 1.0 g, 100 min, 303 K) | 3.0 | 75.24 |

| 4.0 | 92.21 | |

| 5.0 | 89.31 | |

| 6.0 | 83.50 | |

| 7.0 | 65.11 | |

| 8.0 | 51.50 | |

| Initial concentration (mg/l): | 50–500 | 100 |

| Conditions: pH = 4, 1.0 g, 100 min, 303 K) | 600 | 100 |

| 700 | 92.2 | |

| 800 | 80.5 | |

| 900 | 71.6 | |

| 1000 | 64.4 | |

| Adsorbent dose (g) : | 0.2 | 56.45 |

| Conditions: 700 mg/l, 100 min, pH = 4, 303 K) | 0.4 | 65.34 |

| 0.8 | 73.40 | |

| 0.9 | 92.20 | |

| 1.0 | 94.50 | |

| 1.2 | 94.58 | |

| 1.4 | 94.32 | |

| Temperature (K) : | 301 | 94.50 |

| Conditions: 700 mg/l, 100 min, 1.0 g, pH = 4) | 313 | 95.33 |

| 323 | 97.41 | |

| 328 | 90.22 | |

| 333 | 80.90 | |

Sorption kinetics

Three kinetic models were used to explain and estimate the uptake of uranium ions on flax fiber by linear and nonlinear techniques [21]. Non-linear technique is a better system to acquire the parameters of kinetic models.

Pseudo-first-order model

This model [22], is explained by the following equations:

| (3) |

| (4) |

Pseudo-second-order model

The model is explained by equations [23]:

| (5) |

| (6) |

where, qe and qt are the sorption capacity at final and any time t (mg/g) and K1 (L/min) and K2 (g/mg.min) are the constants of the pseudo-first and second order models, respectively.

The Elovich kinetic model

The Elovich model is used to illustrate the chemisorption process assuming that the sorbent surfaces are vigorously heterogeneous, but the equation does not suggest any specific mechanism for sorbate–sorbent and is explained by equation [24]:

| (7) |

The parameters of α and β are the Elovich constants which refer to the sorption rate (mg/g. min), and the capacity of flax fiber (g/mg), respectively. The Elovich equation was given in linear form by the eq.:

| (8) |

Results & discussion

Characterization

Chemical composition

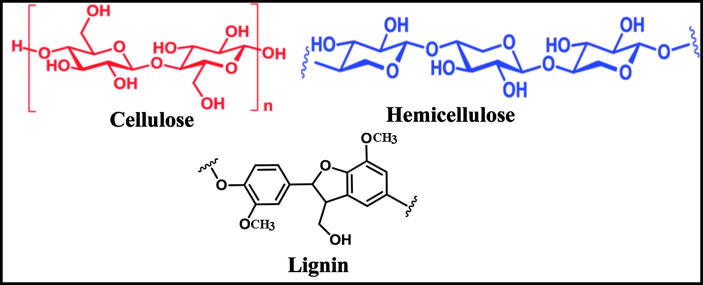

Cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin (Fig. 1) are the main components of flax fibers [26]. Lignin acts as a bonding material. The composition (cellulose, hemicelluloses, lignin and ash) of Fax fibers were analyzed using the process developed by Aravantinos-Zafiris et al. (1994) [25]. The chemical compositions of flax fiber are shown in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin.

Table 1.

Chemical composition (dry basis) of flax fiber.

| Component | Cellulose | Hemicelluloses | Lignin | Ashes | others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (%) | 85.3 | 8.3 | 3.5 | 1.03 | 1.67 |

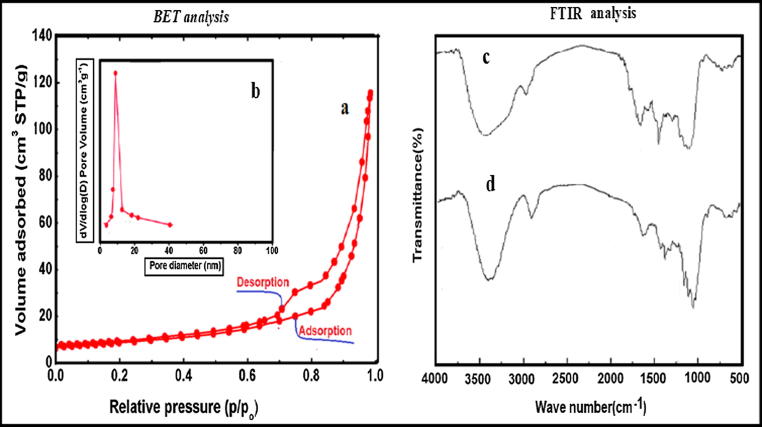

BET analysis

Fig. 2 shows N2 sorption–desorption isotherms (NOVA 2200E BET Surface Area Analyzer, Quantachrome Instruments) of flax fiber, which is described as IV- style with a hysteresis loop, which indicates a mesoporous nature of flax fiber. The hysteresis loop have a quick adsorption and desorption nature, representing a narrow mesopore size distribution. Flax fiber possesses a large surface area of 51.54 m2/g and a pore volume of 0.41 cm3/g. The active sites of flax fiber were provided by a high surface area. The active adsorptive sites result from the mesoporous nature of flax fiber leading to its the high adsorption capacity of uranium ions onto the fiber.

Fig. 2.

N2 adsorption–desorption isotherm (a) and pore-size distribution (b) of flax fiber and FTIR spectrum of flax fiber before (c) and after uptake (d).

Fourier transformed infrared spectroscopy analysis (FTIR)

The FTIR (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) of the flax fiber (Fig. 2) describes the properties of material components. The band at 3483 cm−1 refers to O—H group and C—H bonds in the alkyl groups at 2910 cm−1. The band at 1735 cm−1 and 1642 cm−1 explains that there is a C O group of hemicellulose and ketenes, respectively [15]. The bands at 1465 and 1433 cm−1 represent symmetric —CH, —CH2 vibrations and C—H group at 1387 cm−1 of methyl group. The band near 1165–1130 cm−1, refer to asymmetric C—O—C. The bands at 1032 cm−1 refer to the ether group of C—O ether [27]. After the process of adsorption, changes were made in O—H group, C—H bonds and C O group to 3490, 2923 and 1653 cm−1, respectively. These shifts indicate that there is a correlation between the uranium ions and the functional groups that make up the flax fibers by the ion exchange of H+ on the surface of fibers with UO22+ which changes the vibration strength and peak wavenumber[15]. The shifts in wavelength and the alteration in absorption intensity of O—H group, C—H bonds and C O groups can be correlated to the mechanism of adsorption. The presence of O—H stretching vibration may be attributed to the components of cellulose and lignin that may required in UO22+ binding during ion exchange and/or complexation mechanisms [28].

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis

Fig. 3 (a and b), shows the XRD pattern of flax fiber before and after adsorption was performed by X-ray diffractmeter (Philips instrument PW 1730). In the raw flax fiber four patterns of diffraction are presented at 2θ = 14.82°, 16.56°, 22.76°, and 33.99°, which refer to the planes of ( −1 1 0), (1 1 0), (2 0 0), and (0 0 4), respectively, indicating the crystalline structure of cellulose after adsorption[29]. Similar diffraction peaks were observed, and additionally new peaks at 2θ = 33.22°, and 74.55° referred to planes of (1 1 1) and (3 1 1), respectively. The appearance of new peaks and decreasing of the crystal structure after the uranium uptake may owe to the uptake of U(VI) by flax fibers, which causes part of the particle construction to modify from crystal to amorphous[11].

Fig. 3.

XRD spectra of flax fiber before (a) and after (b) adsorption (C) TGA and DTG curves of raw flax fiber (N2 atmosphere at 283 K).

Thermal analysis

Thermal analysis was performed by DTA-50 Differential Thermal Analyzer, Japan. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) shows a degradation percent of 3.3% within 304–501 K, of dehydration reactions of water content [30]. The degradation percent of flax fiber begin at 502 K and increase with increasing the temperature to 80% between 502 K and 683 K (Fig. 3C). The degradation percent within 684–798 K was 6.3%, of char degradation [31]. Differential thermal gravimetry analysis (DTG) shows two peaks at 565 and 648 K which corresponding to light and heavy materials, respectively. DTG curve indicates that the maximum degradation happened at the temperature 648 K with the rate of 0.68 mg/min.

Thermal analysis indicates that there are two steps are involved in the degradation of flax fiber. The first step is the hemicellulose degradation [31], between 565 K and 598 K of percent 18.6% (Fig. 3C). The second step of degradation begin at 598 K and is finished at 648 K.

Sorption studies

Sorption time, pH, initial U(VI) concentration, dose and temperature were optimized and expressed as removal percent (R%) of U (VI) ion on the adsorbent. The uptake of uranium increases with increasing time until it reaches a certain time (100 min), no noticeable change occurs with increase in time due to saturation of adsorption sites [32], [33]. The pH parameter is very important in the adsorption of U(VI) ions because of its ability to change the ionic forms of uranyl ions. Uranium uptake was raised with increasing the pH until reaching a maximum value at pH 4 and then decreased (Table 2). Lower adsorption of uranium ions at low pH values is due to the competition with H+ on the surface of flax fiber [34]. When pH values increase beyond pH 4 the percentage removal decreases due to the creation of other forms (UO2(OH)2) or precipitation. Also, the effect of ionic strength on U(VI) adsorption was studied and the result indicates that the uptake of U(VI) ions on flax fibers is feebly reliant on ionic strength along the pH range. Table 2, demonstrates that the removal percent of uranium ions remains at its maximum value; 100%, between 100 and 600 mg/l initial concentration and then it decreases as U (VI) concentration is raised, due to a decrease in the adsorption sites on the surface of flax fiber [35]. The effect of flax fiber dose on the U(VI) uptake was explained in the range 0.2 to 1.6 g. Table 2, shows that the removal percent increased with increasing the dose due to the increase in sorption sites. Until it reaches a certain limit (1.0 g) there will be no further increase in the uptake percentage [36], [37]. Keeping all other parameters constant, the uptake of uranium increased slightly with increasing the temperature up to 323 K and then it started decreasing at temperatures from 323 to 333 K as shown in Table 2. This refers to both endothermic from 301 to 323 K and exothermic in nature from 323 to 333 K.

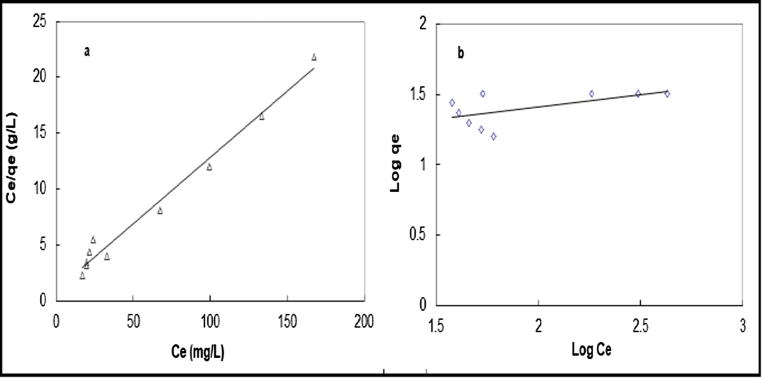

Isotherms studies

Five isotherm models (Langmuir, Freundlich, Temkin, Redlich-Peterson and Jovanovic model) were used to explain the equilibrium uptake of uranium ions on flax fiber and the isotherm parameters were estimated by linear and nonlinear systems. The achieved isotherm parameters determined by nonlinear methods are good fitting than those acquired by linear methods because the non linear methods overcome the inaccuracy of the results using the original isotherm equations [38], [39].

Langmuir model

This isotherm is used to determine the monolayer uptake of U (VI) onto flax fiber and is described by the following equations [35]:

| (9) |

| (10) |

where, Ce is the U(VI) concentration at equilibrium (mg/L). QL (mg/g) and KL (L/mg) are constants of Langmuir isotherm.

Freundlich model

This isotherm [40] explain the intensity of U (VI) adsorption on the adsorbent by eq.:

| (11) |

| (12) |

KF (mg(1−1/n)L1/ng−1) is Freundlich constant and n is a value that refers to the intensity of U(VI) adsorption onto flax fiber.

Temkin model

Temkin model supposes that adsorption heat reduces with the decline of adsorption capacity and described by the following eq. [15], [40]:

| (13) |

| (14) |

where KT (L/g), R, T and H (J/mol) are constants of Temkin model (L/g), universal gas constant (8.314 J/mol/K), temperature (K) and constant related to sorption heat (J/mol), respectively.

Redlich-Peterson model

This model describes adsorption equilibrium in excess of adsorbate concentration which is appropriate in either homogenous or heterogeneous processes and expressed by the following eq. [37]:

| (15) |

| (16) |

where KRP (L/g) and A (L./mg)β are the constant of Redlich-Peterson model. The item β is the exponent related to adsorption energy

Jovanovic model

Jovanovic model is predicated on the assumptions limited in the Langmuir model, but also the option of a little mechanical associates among the sorbate and sorbent and expressed by the following eq. [40]:

| (17) |

| (18) |

where qmax is maximum uptake of sorbate (mg/g), and KJ is the Jovanovic constant (L/mg).

The linear and nonlinear parameters of adsorption isotherms are listed in Table 3. The results of the linear analysis show that the Langmuir model appears to be the best fitting model for U(VI) uptake on flax fiber with higher correlation coefficient (R2) than other models indicating that U(VI) ions are adsorbed onto flax fiber as monolayer surface adsorption. Fig. 4 shows the plot of non-linear isotherms obtained at 323 K. The results obtained by the non-linear method confirmed that the Langmuir model is the most suitable model than other models for the adsorption process as the adsorption capacity results are consistent with the results of experiments and also the value of correlation coefficient (R2) and chi-square analysis (χ2) are greater than other isotherms.

Table 3.

Parameters of adsorption linear and nonlinear isotherm models at 323 K (pH4, 100 min, 1.2 g, 700 mg/l).

| Experimental qe (mg/g) | Isotherms | Linear | Non-linear |

|---|---|---|---|

| Langmuir isotherm | |||

| QL (mg/g) | 42.721 | 41.221 | |

| KL (L/mg) | 0.0511 | 0.0612 | |

| R2 | 0.949 | 0.984 | |

| χ2 | 3.210 | ||

| Freundlich isotherm | |||

| KF (mg(1−1/n)L1/ng−1) | 2.577 | 4.680 | |

| n | 3.481 | 3.410 | |

| 40.90 | R2 | 0.921 | 0.935 |

| χ2 | 17.75 | ||

| Temkin isotherm | |||

| KT (L/g) | 1.110 | 1.055 | |

| H (J/mol) | 334 | 338 | |

| R2 | 0.912 | 0.930 | |

| χ2 | 9.709 | ||

| Redlich-Peterson isotherm | |||

| KRP (L/g) | 8.541 | 11.23 | |

| A (L./mg)β | 0.622 | 0.891 | |

| β | 0.791 | 0.780 | |

| R2 | 0.885 | 0.901 | |

| χ2 | 6.231 | ||

| Jovanovic isotherm | |||

| KJ (L/mg) | 0.0002 | 0.0451 | |

| qmax | 35.760 | 37.430 | |

| R2 | 0.413 | 0.831 | |

| χ2 | 18.82 | ||

Fig. 4.

Non-linear isotherm models for U (VI) adsorption by flax fiber at 323 K.

Adsorption kinetics

The results of the linear and non linear kinetic studies (Table 4), show that the value of theoretical adsorption capacity (qe) of pseudo first order kinetics and Elovich model do not fit the experimental result. But, a good agreement was obtained with pseudo second order rate (Fig. 5). For pseudo second order model, the parameters are similar to those achieved by the linear technique. The These results explain that the process of uranium uptake on flax fibers corresponds or follows the pseudo second order model and the higher value of correlation coefficient confirm this result.

Table 4.

Results of linear and nonlinear kinetic models at 323 K.

| Experimental qe (mg/g) | Kinetic models | Linear | Non-linear |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudo-first-order kinetics | |||

| qe (mg/g) | 24.81 | 36.99 | |

| K1 (L/min) | 0.0051 | 0.088 | |

| R2 | 0.5985 | 0.913 | |

| χ2 | 2.750 | ||

| 40.90 | Pseudo-second-order kinetics | ||

| qe (mg/g) | 41.6 | 41.42 | |

| K2 (g/mg min) | 0.0023 | 0.003 | |

| R2 | 0.995 | 0.996 | |

| χ2 | 0.329 | ||

| Elovich model | |||

| α (mg/g min) | 0.398 | 0.455 | |

| β (g/mg) | 6.912 | 6.905 | |

| R2 | 0.9607 | 0.954 | |

| χ2 | 1.618 | ||

Fig. 5.

Non-linear kinetic models for U (VI) adsorption by flax fiber at 323 K.

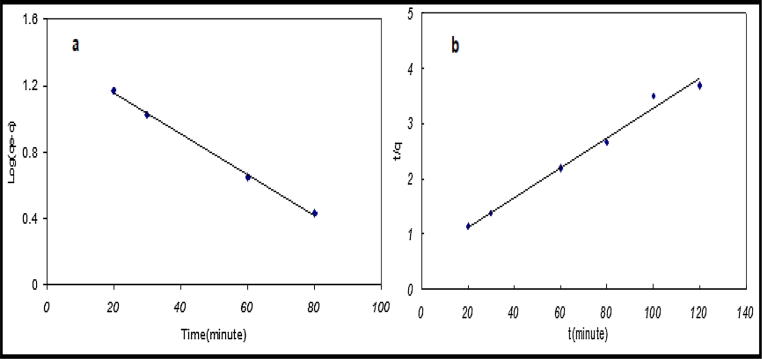

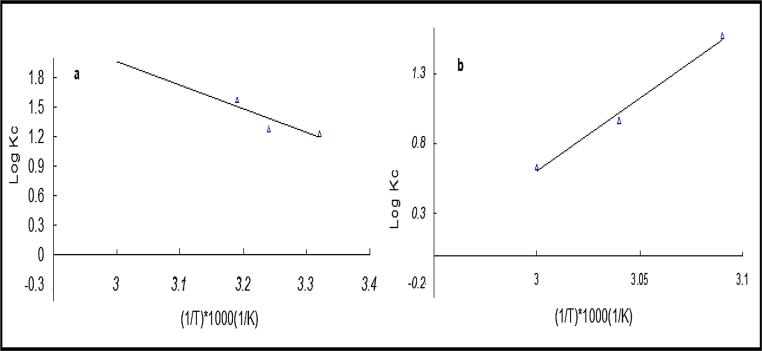

Thermodynamic studies

Enthalpy change (ΔHo), Free energy change (ΔGo) and entropy change (ΔSo) were calculated from the following eqs. [32], [35]:

| (19) |

| (20) |

| (21) |

where:

T: Temperature (K)

R: Gas constant (8.314 J /mol. K)

| (22) |

where CFe and CSe are uranium concentrations at flax fiber and in liquid sample (mg/l), respectively at equilibrium.

In this section ΔHo and ΔSo were determined from Van’t Hoff graph (Fig. 6). If ΔH0 > 0 (positive) the process is endothermic in nature and the U(VI) uptake increases with rise the temperature. On the other hand, if ΔH0 < 0 (negative) the process is exothermic in nature and the U(VI) uptake decreases with rise in the temperature as a result of breaking the bonds formed by high temperature[7]. Table 5, shows that ΔG° was negative and increases by increasing the temperature from 301 to 323 K (Fig. 6a), then decreased after 323 K (Fig. 6b), which indicate the favorability of uranium uptake at lower temperature. The reason for the endothermic nature (from 301 to 323 K) is the increase in the pores of the fiber by heating effect, which leads to the emergence of active sites on the surface of the fiber which increase the interaction of UO22+ with the functional groups (O—H group, C—H bonds and C O group) of the cell walls of flax fibers by the ion exchange of H+ on the surface with UO22+. Besides, spread free UO22+ into the pores of the fibers(electrostatic interaction) [41]. While the exothermic system (from 323 to 333 K) is due to the release of uranium ions from the active sites on the fiber surface due to weak or broken in the interaction between UO22+and the functional groups responsible for bonding. The positive ΔH° from 301 to 323 K, refers to an endothermic behavior, and negative ΔH° in the range 323 to 333 K, indicates an exothermic behavior. Positive ΔSo refers to random uptake of uranium ions onto flax fibers.

Fig. 6.

Van’t Hoff plot of U (VI) adsorption by flax fiber: (a) at (301–323 K) and (b) at (323–333 K).

Table 5.

Thermodynamic results for the adsorption of U (VI) by flax fiber.

| Temperature (K) | Kc | ΔGo (kJ·mol−1) | ΔHo (J·mol−1) | ΔSo (J·mol·K−1)−1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endothermic | 301 | 17.18 | −58.43 | 46.21 | 176.12 |

| 313 | 18.61 | −55.07 | |||

| 323 | 37.61 | −56.84 | |||

| Exothermic | 323 | 37.61 | −56.84 | −201 | 574.0 |

| 328 | 9.33 | −57.72 | |||

| 333 | 4.29 | −58.60 | |||

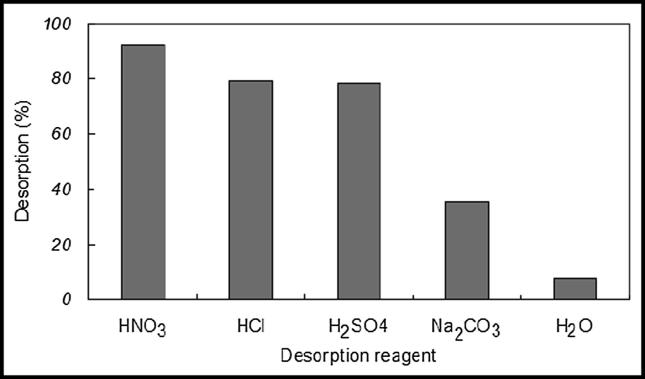

Desorption process

The recovery of U (VI) from loaded adsorbent material (flax fiber) was performed using five different desorption solutions (HNO3, HCl, H2SO4, Na2CO3 and H2O) at room temperature (Fig. 7). Firstly, loaded flax fiber was treated with 50 mL (1.5 M of HNO3, HCl, H2SO4, and Na2CO3) of each eluting solution in thermostatic shaker bath for 1 h at 301 K. Water has a weak effect as eluting agent in the desorption of uranium ions from fibers because it removes the uranium ions of very weak interaction with both pores and surface. Proton exchanging agent is the main mechanism of desorption process. The HNO3 is also able to dissolve uranium to form the soluble form. Desorption process occurs by the replacement of uranium ions on the surface and pores of flax fiber by H+ and U(VI) ions are released to the bulk solution. Fig. 7, shows higher desorption when HNO3 is used. Therefore, HNO3 was selected as the best desorbing agent for recovering U (VI) ions. Desorption (%) was calculated according to the following eq.:

| (22) |

Fig. 7.

Effect of different eluting agents on U (VI) desorption from loaded Flax fiber.

Recovering process

Uranium ion in desorption liquid was recovered by adding ammonium solution, NH4OH (35%) until reacheding to pH 8. The form product (ammonium diurinate) was then filtered and heated at 1073 K to obtain uranium oxide [34]. The residue after cooling is screened and examined by environmental scanning electron microscope (ESEM) (Fig. 8). This analysis indicates that the content of uranium as U3O8 in the sintered yellow cake reached 98.83%.

Fig. 8.

ESEM scanning of sintered precipitate of yellow cake.

The regeneration and reuse of the adsorbent material

The regenerated flax fibers were reused in the recycle process to study the change in its adsorption capacity. The results of adsorption – desorption cycles are given in Table 6. The results show a lowering in adsorption percent with increase in desorption cycles. Table 7, shows the U(VI) uptake by flax fiber and other adsorbents from liquid waste. The comparison of adsorption capacity values between flax fibers and other materials confirms that flax fibers exhibit an acceptable absorption capacity of U(VI) from aqueous solutions. The block diagram of U(VI) uptake using flax fiber in the batch technique was shown in Fig. 9.

Table 6.

Adsorption- desorption cycles of U (VI) ions by flax fiber.

| No. of cycle | Adsorption (%) | Adsorption capacity qe (mg/g) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 93.50 | 27.27 |

| 2 | 88.50 | 25.80 |

| 3 | 83.71 | 24.78 |

| 4 | 80.45 | 23.33 |

| 5 | 78.23 | 21.44 |

Table 7.

Adsorption U (VI) capacities of flax fiber and other sorbents.

| Adsorbents | Adsorption condition |

Adsorption capacity (mg/g) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | Time (min) | Dose (g) | Concentration Range (mg/l) | Temperature (K) | ||

| Graphene oxide-activated carbon [3] | 5.3 | 30 | 0.01 | 50 | 298 | 298.0 |

| Orange peels [7] | 4.0 | 60 | 0.30 | 25–200 | 303 | 15.91 |

| Silicon dioxide nanopowder [14] | 5.0 | 20 | 0.30 | 50–100 | 303 | 10.15 |

| Modified Rice Stem [15] | 4.0 | 180 | 0.20 | 5–60 | 298 | 11.36 |

| N, P, and S Codoped Graphene [16] | 5.0 | 25 | 0.01 | 5–100 | 298 | 294.1 |

| Nanogoethite powder [17] | 4.0 | 120 | 1.00 | 5–200 | 298 | 104.22 |

| Iron/magnetite carbon composites [18] | 5.4 | 50 | 0.15 | 20 | 298 | 203.94 |

| Aluminum oxide nanopowder [23] | 5.0 | 40 | 0.15 | 50–250 | 303 | 37.93 |

| Powdered corncob [36] | 5.0 | 60 | 0.30 | 25–100 | 303 | 14.21 |

| Natural clay [37] | 5.0 | 120 | 0.15 | 5–40 | 298 | 3.470 |

| Flax fiber (The present work) | 4.0 | 100 | 1.00 | 50–1000 | 323 | 40.90 |

Fig. 9.

Block diagram of removal and recovery of U (VI) by flax fibers.

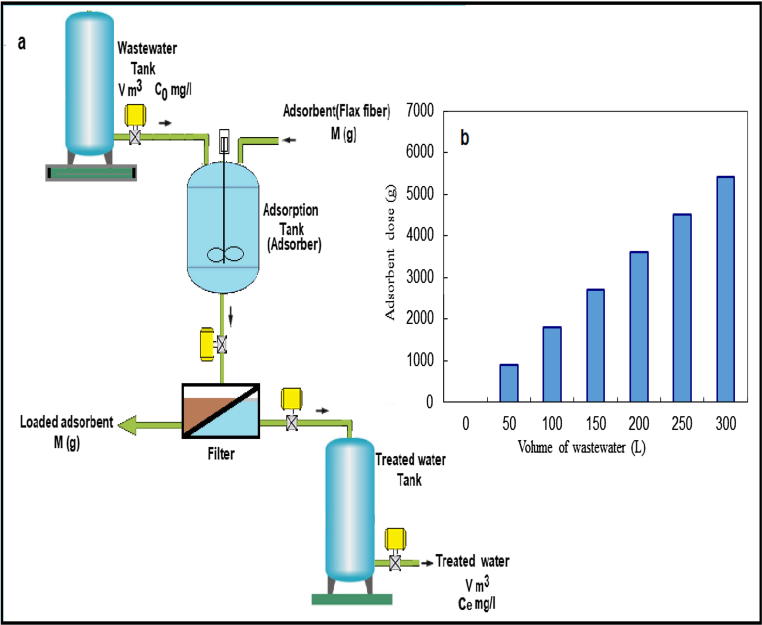

Design of batch adsorber

The data required to design a full scale of batch unit for removal of uranium ion from liquid wastes were determined from the results of the best adsorption isotherm model which [36]. In this work, a full-scale unit of batch technique was designed from data of Langmuir isotherm. Fig. 10a shows a technique of batch-unit for U (VI) adsorption using flax fiber.

Fig. 10.

Schematic diagram of a single-unit batch absorber.

If that a liquid volume V (m3) of U (VI) of initial concentration C0 (mg/l), was treated to a finial concentration Ce (mg/l) using adsorbent mass M (g). Adsorption capacity of flax fiber was increased from q0 at time 0 to qe at equilibrium. The balance equation of batch-unit, was determined as follows:

| (23) |

When, q0 = 0, Eq. (14) be in the form:

| (24) |

qe was determined from Langmuir equation (6) as follows:

| (25) |

| (26) |

By substituting qe in Eq. (15) the following equation is obtained:

| (27) |

Eq. (22) is used to determine both flax fiber doses and the volume of wastewater introduced in the full scale batch unit (Fig. 10b). Design data indicated that flax fiber has a good potential for adsorbing high concentrations of U (VI) ions from liquid wastes.

Conclusion

Flax fiber showed to be an acceptable adsorbent material for removal and recovery of U (VI) with higher liquid concentrations. Equilibrium uranium capacity of flax fiber was 40.9 mg/g at pH 4 and 323 K. Thermo studies showed that the uptake of U(VI) is an endothermic process between 301 K and 323 K and exothermic in nature from 323 K to 333 K. The adsorption data obtained by linear and nonlinear showed both the Langmuir and pseudo second order models are the best fitting models. Regeneration process of flax fibers have proved a lowering in adsorption percent with increase in desorption cycles. A full scale batch adsorber unit is designed using the best adsorption isotherm model.

Compliance with ethics requirements

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors have declared no conflict of interest

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank SABIC Company, KSA and Jazan University, KSA for financial support this research. The research was funded from financial support No. Sabic 3/2018/1.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Cairo University.

References

- 1.Shin D.C., Kim Y.S., Moon H.S., Park J.Y. International trends in risk management of groundwater radionuclides. J Environ Toxic. 2002;17:273–284. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abbasi W.A., Streat M. Adsorption of uranium from aqueous solutions using activated carbon. Sep Sci Technol. 1994;29:1217–1230. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen S., Hong J., Yang H., Yang J. Adsorption of uranium (VI) from aqueous solution using a novel graphene oxide-activated carbon felt composite. J Environ Radioact. 2013;126:253–258. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvrad.2013.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Naushad M.U., Ahamad T., Othman Z.A., Al-Muhtaseb A.H. Green and eco-friendly nanocomposite for the removal of toxic Hg(II) metal ion from aqueous environment: Adsorption kinetics & isotherm modelling. J Molecular Liq. 2019;279:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Denise A., Fungaro I., Yamaura M., Craesmeyer M.R.G. Uranium removal from aqueous solution by zeolite from fly ash-iron oxide magnetic nanocomposite. Intern Rev Chem Eng. 2012;4:353–358. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goswami D., Das A.K. Preconcentration and recovery of uranium and thorium from Indian monazite sand by using a modified fly ash bed. J Radio Nucl Chem. 2003;258:249–254. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mahmoud M.A. Removal of Uranium (VI) from Aqueous solution using low cost and eco-friendly adsorbents. J Chem Eng Process Techn. 2013;4:169–175. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Man J.K., Bo E.H., Pil S.H. Precipitation and adsorption of uranium (VI) under various aqueous conditions. Environ Eng Res. 2002;7:149–157. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baran V., Šourková L., Spalová J. Water-free precipitation uranate with maximum sodium content, Na/U=1.0. J Radioanalytical and Nuclear. Chem Lett. 1985;95:331–338. [Google Scholar]

- 10.El-Hazek N.T., El Sayed M.S. Direct uranium extraction from dihydrate and hemi-dihydrate wet process phosphoric acids by liquid emulsion membrane. J Radioanalyt Nucl Chem. 2003;257:347–352. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu W., Dai X., Bai Z., Wang Y., Yang Z., Zhang L., et al. Highly sensitive and selective uranium detection in natural water systems using a luminescent mesoporous metal-organic framework equipped with abundant lewis basic sites: a combined batch, X-ray absorption spectroscopy, and first principles simulation investigation. Environ Sci Technol. 2017;51:3911–3921. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.6b06305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yuan L.Y., Zhu L., Xiao C.L., Wu Q.Y., Zhang N., Yu J.P., et al. Large-pore 3D cubic mesoporous (KIT-6) hybrid bearing a hard-soft donor combined ligand for enhancing U(VI) capture: an experimental and theoretical investigation. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017;9:3774–3784. doi: 10.1021/acsami.6b15642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daxiang G., Tao Z., Lanhua C., Yanlong W., Yuxiang L., Daopeng S., et al. Hydrolytically stable nanoporous thorium mixed phosphite and pyrophosphate framework generated from redox-active ionothermal reactions. Inorg Chem. 2016;55:3721–3723. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.6b00293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mohamed M.A. Adsorption of U (VI) ions from aqueous solution using silicon dioxide nanopowder. J Saudi Chem Soci. 2018;22:229–238. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang X., Jiang D., Xiao Y., Chen J., Hao S., Xia L. Adsorption of Uranium(VI) from aqueous solution by modified rice stem. J Chemistry. 2019;2019:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhe C., Wanying C., Dashuang J., Yang L., Anrui Z., Tao W., et al. N, P, and S codoped graphene-like carbon nanosheets for ultrafast uranium (VI) capture with high capacity. Adv Sci. 2018;5:1–9. doi: 10.1002/advs.201800235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lijiang Z., Zhang X., Qian L., Xiaoyan W., Tianjiao J., Mi Li, et al. Adsorption of U(VI) ions from aqueous solution using nanogoethite powder. Adsorpt Sci Technol. 2019;37:113–126. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhimin L., Shimin Y., Lei C., Ahmed A., Tasawar H., Changlun C. Nanoscale zero-valent iron/magnetite carbon composites for highly efficient immobilization of U(VI) J Environ Sci. 2019;76:377–387. doi: 10.1016/j.jes.2018.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wencheng S., Xiangxue W., Yubing S., Tasawar H., Xiangke W. Bioaccumulation and transformation of U(VI) by sporangiospores of Mucor circinelloides. Chem Eng J. 2019;362:81–88. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toshev Z., Stoyanova K., Nikolchev L. Comparison of different methods for uranium determination in water. J Environ Radioact. 2004;72:47–55. doi: 10.1016/s0265-931x(03)00185-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu J., Wang J., Jiang Y. Removal of uranium from aqueous solution by alginate beads. Nucl Eng Technol. 2017;49(3):534–540. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lagergren S. About the theory of so-called adsorption of solution substances. Handling. 1898;24:147–156. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mohamed A.M. Kinetics and thermodynamics of U(VI) ions from aqueous solution using oxide nanopowder. Process Saf Environ Prot. 2016;1 0 2:44–53. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chun W.C., John F.P. Elovich equation and modified second-order equation for sorption of cadmium ions onto bone char. J Chem Technol Biotechnol. 2000;75:963–970. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aravantinos-Zafiris G., Oreopoulou V., Tzia C., Thomopoulos C.D. Fibre fraction from orange peel residues after pectin extraction. Lebensm-Wiss u-Technol. 1994;27:468–471. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kenji M., Xiaoyu D., Naoto M., Naoki K., Hiroshi I. Experimental and theoretical studies on the adsorption mechanisms of Uranium (VI) ions on chitosan. J Funct Biomater. 2018;9:49–60. doi: 10.3390/jfb9030049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ibrahim S.C., Hanafiah M.A., Yahya M.Z.A. Removal of cadmium from aqueous solutions by adsorption onto Sugarcane Bagasse. Am-Euras J Agric Environ Sci. 2006;1:179–184. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singha A.S., Guleria A. Use of low cost cellulosic biopolymer based adsorbent for the removal of toxic metal ions from the aqueous solution. Sep Sci Technol. 2014;49:2557–2567. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khan M.R., Gotoh Y., Morikawa H., Miura M. Graphitization behavior of iodine-treated Bombyx mori silk fibroin fiber. J Mater Sci. 2009;16:4235–4240. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martins M.A., Joekes I. Tire rubber–sisal composites: Effect of mercerization and acetylation on reinforcement. J Appl Polym Sci. 2003;89:2507–2515. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fairbridge C., Ross R.A.A. kinetic and surface study of the thermal decomposition of cellulose powder in inert and oxidizing atmospheres. J Appl Polym Sci. 1978;22:497–510. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kutahyal C., Eral M. Sorption studies of uranium and thorium on activated carbon prepared from olive stones: kinetic and thermodynamic aspects. J Nucl Mater. 2010;396:251–256. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mohamed M.A., El-Halwany M.M. Adsorption of cadmium onto orange peels: isotherms, kinetics, and thermodynamics. J Chromatograph Separat Techniq. 2014;5:238–243. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mahmoud M.A. Kinetics studies of uranium sorption by powdered corn cob in batch and fixed bed system. J Adv Res. 2016;7:79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2015.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mahmoud M.A., Abutaleb A., Maafa I.M.H., Qudsieh I.Y., Elshehy E.A. Synthesis of polyvinylpyrrolidone magnetic activated carbon for removal of Th (IV) from aqueous solution. Environ Nano Monit Manage. 2019;11:100191. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mahmoud M.A. Design of batch process for preconcentration and recovery of U (VI) from liquid waste by powdered corn cobs. Environ Chem Eng. 2015;3:2136–2144. [Google Scholar]

- 37.François E.B., Joseph N.N., Jean A.O., Paola A.E., Edouard N.E. Batch experiments on the removal of U(VI) ions in aqueous solutions by adsorption onto a natural clay surface. J Environ Earth Sci. 2013;3:11–23. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lima E.C., Bandegharaei A.H., Carlos Juan, Moreno-Piraján J.C., Anastopoulos I. A critical review of the estimation of the thermodynamic parameters onadsorption equilibria. Wrong use of equilibrium constant in the Van'tHoof equation for calculation of thermodynamic parametersof adsorption. J Mol Liquids. 2019;273:425–434. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fenti A., Iovino P., Salvestrini S. Some remarks on A critical review of the estimation of the thermodynamic parameters on adsorption equilibria. Wrong use of equilibrium constant in the Van't Hoof, equation for calculation of thermodynamic parameters of adsorption. J Mol Liquids. 2019;276:529–530. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nimibofa A., Augustus N.E., Donbebe W. Modelling and interpretation of adsorption isotherms. J Chemistry. 2017;2017:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yusan S., Erenturk S. Behaviors of uranium (VI) ions on α-FeOOH. Desalination. 2011;269:58–66. [Google Scholar]