Abstract

DNA damage-induced apoptosis suppressor (DDIAS), also called hNoxin or C11 or f82, is an anti-apoptotic protein in response to stress. The clinicopathological significance of DDIAS in non-small cell lung cancer patients is largely unknown until now. The purpose of our study is to analyze the clinicopathological association of DDIAS in NSCLC patients. We found that the positive ratio of DDIAS was significantly higher than that in the corresponding non-cancerous lung tissues (P<0.001). Positive DDIAS expression correlated with larger tumor size and positive regional lymph node metastasis (P=0.048 and P=0.018, respectively). Online Kaplan-Meier Plotter tool analysis results and survival analysis results of our cohort revealed that both DDIAS gene level (P=0.0048) and protein level (P<0.001) were associated with adverse outcome in NSCLC patients for overall survival, as well as in multiple subgroups divided by different clinicopathological features. Subsequent univariate and multivariate analysis suggested that only positive DDIAS was an independent prognostic factor for overall survival (P=0.018). In NSCLC cell lines, overexpression of DDIAS enhanced the ability of invasion and proliferation, whereas depleting DDIAS depressed the ability of invasion and proliferation. In conclusion, our results suggest that positive DDIAS expression may be a potent prognostic factor in NSCLC patients. DDIAS promotes proliferation and invasion in NSCLC cells and correlates with progression of NSCLC patients.

Keywords: DDIAS, NSCLC, prognosis, invasion, proliferation

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death worldwide because of the poor prognosis and limited treatment options [1-3]. To identify useful factors for risk stratification and treatment decisions is of great importance [4,5].

DNA damage-induced apoptosis suppressor (DDIAS), also called hNoxin or C11 or f82, is an anti-apoptotic protein in response to a wide range of stress signals, such as γ- and UV irradiation, hydrogen peroxide, adriamycin and cytokines [6-9]. In NIH 3T3 cells, endogenous DDIAS was localized predominantly in the cytoplasm and translocated into nucleus in response to stress [6]. In the previous reports, DDIAS was found overexpressed in colorectal and lung cancer cells [7]. Moreover, the levels of DDIAS expression were correlated with clinical progression in human hepatocellular carcinoma [10]. However, the clinicopathological significance of DDIAS, especially in lung cancer patients with no exposure to any stresses, is largely unknown to date.

The purpose of our study was to analyze the clinicopathological association of DDIAS in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients. To do this, we first assessed the prognostic value of DDIAS using free online survival analysis software (KM Plotter Online Tool; http://www.kmplot.com). We second used immunohistochemistry (IHC) to evaluate the expression of DDIAS in clinical tissue samples of 109 NSCLC patients and 38 corresponding non-cancerous lung tissues. We next analyzed the protein level and subcellular distribution of DDIAS in multiple common NSCLC cell lines using western blot (WB) and immunofluorescence (IF). Finally, we identified the impact of DDIAS on invasion and proliferation after DDIAS plasmid/siRNA transfection using matrigel invasion assay, MTT assay, and colony formation assay.

Materials and methods

Patients and specimens

This study was conducted with the approval of the local institutional review board at the China Medical University. Written consent was given by the participants for their information to be stored in the hospital database for their specimens to be used in this study. All clinical investigation has been conducted according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki. Tissue samples were obtained from 109 patients (68 males and 41 females) who underwent complete surgical excision at the First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University between 2010 and 2012 with a diagnosis of lung squamous cell carcinoma or lung adenocarcinoma, 38 of 109 cases had corresponding non-cancerous lung tissues. No neoadjuvant radiotherapy or chemotherapy was done before surgery. Of the 109 patients, 33 (30.3%) were treated with platinum-based adjuvant chemotherapy, 8 (7.3%) underwent platinum-based adjuvant chemoradiotherapy, and the other 68 patients were treated outside, we did not have information about treatment. The survival of each patient was defined as the time from the day of surgery to the end of follow-up or the day of death. Histological diagnosis and grading were evaluated according to the 2015 World Health Organization (WHO) classification of tumors of the lung [11]. All 109 specimens were for histological subtype, differentiation, and tumor stage. Tumor staging was performed according to the seventh edition of the Union of International Cancer Control (UICC) TNM Staging System for Lung Cancer [12]. The median age in 109 patients was 60 years old (range from 29 years old to 79 years old). Of the 109 patients, 49 patients were equal to or older than 60 years old, 60 patients were younger than 60 years old. The tumor sizes were larger than 3 cm in 64 patients and 45 were equal to or smaller than 3 cm. The tumors included 83 stages I-II cases and 26 stage III cases. Lymph node metastases were presented in 48 of the 109 cases. A total of 38 tumors were well differentiated, while 71 were classified as moderately or poorly differentiated. The samples included 47 squamous cell lung carcinomas and 62 lung adenocarcinomas, respectively. Seventy-seven patients have history of smoking and 33 patients have no history of smoking.

Online analysis of overall survival in NSCLC patients

To evaluate the relationship between the presence of DDIAS and patient clinical outcome, we used the KM Plotter Online Tool (http://www.kmplot.com) in NSCLC patients. This is a public database containing information on gene expression from 1926 patients that permit to investigate the association of genes with overall survival (OS). The clinical features of all specimens were described in a previous report [13].

Immunohistochemistry

Samples were fixed in 10% neutral formalin, embedded in paraffin, and sliced into 4-μm thick sections. Immunostaining was performed by the streptavidin-peroxidase method. The sections were incubated with a polyclonal rabbit anti-DDIAS antibody (1:100; Sigma; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) at 4°C overnight, followed by biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody. After washing, the sections were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin-biotin (Ultrasensitive; MaiXin, Fuzhou, China) and developed using 3, 3-diaminobenzidine tetra-hydrochloride (MaiXin). Finally, samples were lightly counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated in alcohol, and mounted. Two investigators blinded to the clinical data semi-quantitatively scored the slides by evaluating the staining intensity and percentage of stained cells in representative areas. The staining intensity was scored as 0 (no signal), 1 (weak), 2 (moderate), or 3 (high). The percentage of cells stained was scored as 1 (1-25%), 2 (26-50%), 3 (51-75%), or 4 (76-100%). A final score of 0-12 was obtained by multiplying the intensity and percentage scores. Tumors were seen as positive DDIAS expression with a score >4. Tumor samples with scores between 1 and 4 were categorized as showing weak expression, whereas those with scores of 0 were considered to have no expression; both weak expression and no expression were defined as negative DDIAS expression.

Cell culture

The HBE cell line was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA, USA). The A549, H1299, H460, H292, H661, SK-MES-1, Calu-1 and LH7 cell lines were obtained from the Shanghai Cell Bank (Shanghai, China). The LK2 cell line was a gift from Dr. Hiroshi Kijima (Department of Pathology and Bioscience, Hirosaki University Graduate School of Medicine, Hirosaki, Japan). All cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen), 100 IU/ml penicillin (Sigma), and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Sigma), and passaged every other day using 0.25% trypsin (Invitrogen).

Western blot

Total protein was extracted by using a lysis buffer (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) and quantified with the Bradford method. Fifty μg of the total protein samples were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (PVDF; Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). Membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with the following primary antibodies: DDIAS (1:100, HPA038541, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), GAPDH (1:5000, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), Myc-tag (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA). Membranes were washed and subsequently incubated with peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at 37°C for 2 hours. Bound proteins were visualized using electrochemiluminescence (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) and detected with a bio-imaging system (DNR Bio-Imaging Systems, Jerusalem, Israel).

Immunofluorescent staining

The cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, blocked with 1% BSA (bovine serum albumin) and then incubated with the DDIAS (1:100, HPA038541, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) overnight at 4°C, followed by incubation with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) conjugated secondary antibodies (1:200, Zhongshan Golden Bridge, Beijing, China) at 37°C. The nuclei were counterstained with 4, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Fluorescent microscopy was performed using an inverted Nikon TE300 microscope (Melville, NY, USA) and confocal microscopy was performed using a Radiance 2000 laser scanning confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY, USA).

Plasmid transfection and small interfering RNA treatment

Plasmids pCMV6-ddk-myc and pCMV6-ddk-myc-DDIAS were purchased from Origene (Rockville, MD, USA). DDIAS-siRNA (sc-96450) and NC-siRNA (sc-37007) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Transfection was carried out using the Lipofectamine 3000 reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Matrigel invasion assay

Cell invasion assays were performed using a 24-well Transwell chamber with a pore size of 8 μm (Corning Costar Transwell, Cambridge, MA, USA), and the inserts were coated with 20 μl Matrigel (1:3 dilution, BD Biosciences). Then, 48 hours after transfection, cells were trypsinized and transferred to the upper Matrigel chamber in 100 μl of serum-free medium containing 3×105 cells and incubated for 16 hours. Medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Invitrogen) was added to the lower chamber as a chemoattractant. The numbers of invading cells were counted in 10 randomly selected high-power microscope fields. The experiments were performed in triplicate.

MTT

Cells were plated in 96-well plates in medium containing 10% FBS at about 3000 cells per well 24 hours after transfection. For quantitation of cell viability, cultures were stained after 4 days by using the MTT assay. Briefly, 20 μl of 5 mg/ml MTT (Thiazolyl blue) solution was added to each well and incubated for 4 hours at 37°C, then the media was removed from each well, and the resultant MTT formazan was solubilized in 150 μl of DMSO. The results were quantitated spectrophotometrically by using a test wavelength of 490 nm.

Colony formation assay

The A549 and H460 cells were transfected with pCMV or pCMV-DDIAS plasmids, negative control or DDIAS-siRNA for 48 hours. Thereafter, cells were planted into three 6-cm cell culture dishes (1000 per dish for A549 and H460 cell lines) and incubated for 12 days. Plates were washed with PBS and stained with Giemsa. A cluster of blue-staining cells is considered as a colony if it comprises at least 50 cells. The colonies were manually counted by microscope.

Statistical analysis

SPSS version 22.0 for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all analyses. The Pearson’s Chi-square test was used to assess possible correlations between DDIAS and clinicopathological factors. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was carried out in 109 cases specimens and compared using the log-rank test. Cox regression model was used to perform univariate and multivariate analysis. Distiller SR Forest Plot Generator from Evidence Partners (www.evidencepartners.com) was selected to draw the forest plot of the subgroup analysis based on the Cox regression results. Mann-Whitney U test was used for the image analysis of invasive assay results, MTT and colony formation test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate statistically significant differences.

Results

Correlation between DDIAS and clinicopathological features

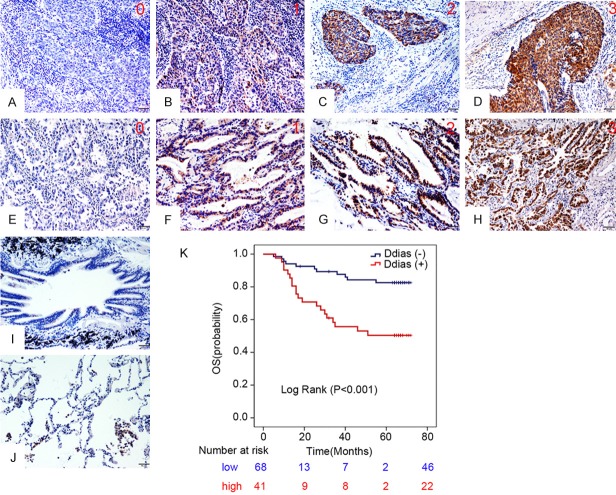

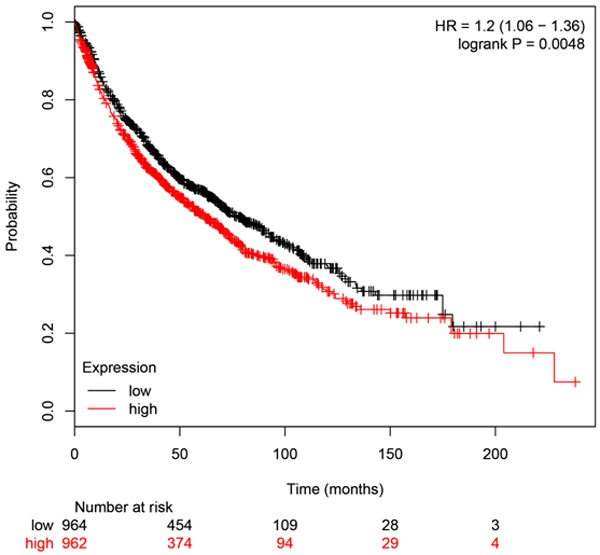

We used the KM-plotter tool, as described in material and methods that contain information from datasets grouping more than 1926 patients, to predict the impaction of DDIAS gene expression on OS. As can be seen in Figure 1, we identified DDIAS genes associated with worse outcome in NSCLC patients for OS (P=0.0048). In our cohort of 109 NSCLC patients, IHC results showed that DDIAS was positively expressed in the cytoplasm. Of the 109 NSCLC tissues, 41 cases presented positive DDIAS expression (37.6%, 41/109), whereas of the 38 corresponding non-cancerous lung tissues, only 6 cases showed positive DDIAS expression (15.8%, 6/38; Figure 2A-J). The positive ratio in NSCLC samples was significantly higher than that in the corresponding non-cancerous lung tissues (P<0.001). Statistical analysis results showed that positive DDIAS expression correlated with larger tumor size (>3 cm) and positive regional lymph node metastasis (P=0.048 and P=0.018, respectively). There was no significant association between the DDIAS expression and age, gender, TNM staging, histological differentiation, histological type and smoking history (Table 1). Kaplan-Meier analysis results revealed that the median survival time of patients with DDIAS expression (47.278 ± 8.134 months) was significantly shorter than those with negative DDIAS expression (63.935 ± 4.562 months; P<0.001; Figure 2K). Univariate and multivariate analysis were performed to identify prognostic factors in 109 NSCLC patients (Table 2). Univariate analysis showed that larger tumor size (P=0.004), advanced TNM stage (P<0.001), positive regional lymph node metastasis (P<0.001) and positive DDIAS expression (P=0.001) was associated with shorter OS. Subsequent multivariate Cox regression analysis revealed that only positive DDIAS was an independent prognostic factor for OS (P=0.018).

Figure 1.

DDIAS genes associated with worse outcome in NSCLC patients for OS. Results of online software survival prediction (KM Plotter). The survival time of patients with positive DDIAS mRNA expression was significantly shorter than those with negative DDIAS mRNA expression.

Figure 2.

DDIAS expression in NSCLC specimens. Representative figures of DDIAS staining intensity from 0 to 3 in lung squamous cell carcinomas (A-D) and lung adenocarcinomas (E-H). Representative figures of DDIAS expression in normal bronchial (I) and alveolar epithelial (J). Kaplan-Meier survival analysis revealed that the overall survival for patients with positive DDIAS expression was significantly shorter than those with negative DDIAS expression (K).

Table 1.

The association between DDIAS expression and the clinicopathological characteristics in 109 cases of NSCLC patients

| DDIAS+ (n=41) | DDIAS- (n=68) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| <60 | 21 | 39 | 0.533 |

| ≥60 | 20 | 29 | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 27 | 41 | 0.562 |

| Female | 14 | 27 | |

| Tumor size | |||

| ≤3 cm | 12 | 33 | 0.048 |

| >3 cm | 29 | 35 | |

| TNM staging | |||

| I-II | 28 | 55 | 0.135 |

| IIIA | 13 | 13 | |

| LN | |||

| No | 17 | 44 | 0.018 |

| Yes | 24 | 24 | |

| HD | |||

| Well | 14 | 24 | 0.903 |

| M & P | 27 | 44 | |

| Histological type | |||

| SCC | 18 | 29 | 0.898 |

| Ade | 23 | 39 | |

| Smoking history | |||

| Never | 11 | 21 | 0.653 |

| Ever | 30 | 47 |

Abbreviations: LN, Regional lymph node metastasis; HD, Histological differentiation; M & P, Moderate & Poor; SCC, Squamous cell cancer; Ade, Adenocarcinoma.

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of OS in 109 cases of NSCLC patients

| OS | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| HR | 95% CI | P | |

| Univariate | |||

| Age: ≥60 | 0.615 | 0.294-1.283 | 0.195 |

| Gender: Male | 1.003 | 0.487-2.067 | 0.994 |

| Tumor size: >3 cm | 3.69 | 1.511-9.009 | 0.004 |

| TNM staging: Advanced | 4.326 | 2.132-8.779 | <0.001 |

| Regional lymph node metastasis: Positive | 5.081 | 2.267-11.388 | <0.001 |

| Histological differentiation: Moderate & Poor | 2.028 | 0.874-4.709 | 0.1 |

| Histological type: Adenocarcinoma | 1.178 | 0.572-2.428 | 0.656 |

| Smoking history: Yes | 1.638 | 0.672-3.995 | 0.278 |

| DDIAS expression: Positive | 3.573 | 1.709-7.472 | 0.001 |

| Multivariate | |||

| Tumor size: >3 cm | 2.272 | 0.905-5.705 | 0.081 |

| TNM staging: Advanced | 2.155 | 0.953-4.870 | 0.065 |

| Regional lymph node metastasis: Positive | 2.322 | 0.904-5.963 | 0.08 |

| DDIAS expression: Positive | 2.494 | 1.173-5.304 | 0.018 |

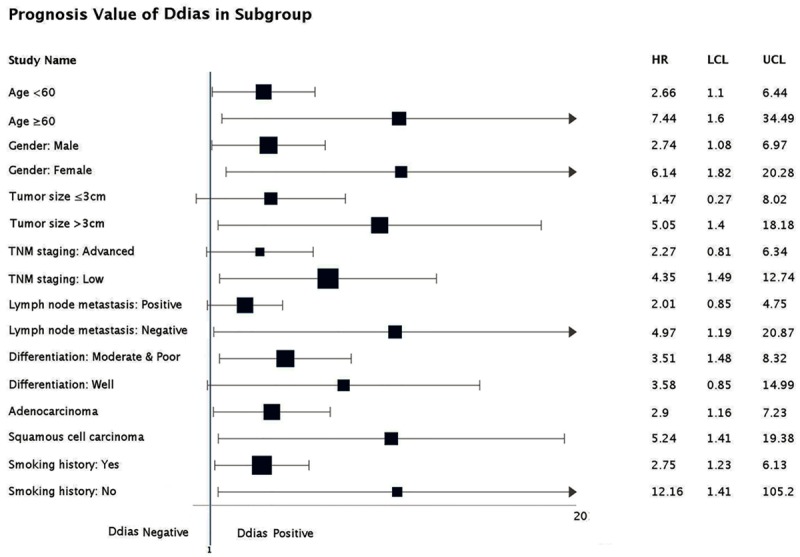

Prognostic value of DDIAS expression in subgroup

Overall survival was further analyzed within subsets of NSCLC patients with features generally considered to impact outcome (Figure 3). Positive DDIAS expression predicted a poor OS in 12 subsets of NSCLC patients defined by clinical or pathologic parameters. These groups included patients with age <60 (HR: 2.66; 95% CI: 1.10-6.44), age ≥60 (HR: 7.44; 95% CI: 1.60-34.49), male patients (HR: 2.74; 95% CI: 1.08-6.97), female patients (HR: 6.14; 95% CI: 1.82-20.28), tumor size >3 cm (HR: 5.05; 95% CI: 1.40-18.18), low TNM staging (HR: 4.35; 95% CI: 1.49-12.74), negative lymph node metastasis (HR: 4.97; 95% CI: 1.19-20.87), moderate and poor histological differentiation (HR: 3.51; 95% CI: 1.48-8.32), adenocarcinoma (HR: 2.90; 95% CI: 1.16-7.23), squamous cell carcinoma (HR: 5.24; 95% CI: 1.41-19.38), with smoking history (HR: 2.75; 95% CI: 1.23-6.13) and without smoking history (HR: 12.16; 95% CI: 1.41-105.2). DDIAS expression status did not affect OS in NSCLC patients with smaller tumor size, advanced TNM staging, positive lymph node metastasis and well histological differentiation.

Figure 3.

DDIAS positive was associated with poor OS. Positive DDIAS expression predicted a poor OS in 12 subsets of NSCLC patients defined by clinical or pathologic parameters (age <60, age ≥60, male patients, female patients, tumor size >3 cm, low TNM staging, negative lymph node metastasis, moderate and poor histological differentiation, adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, with smoking history and without smoking history).

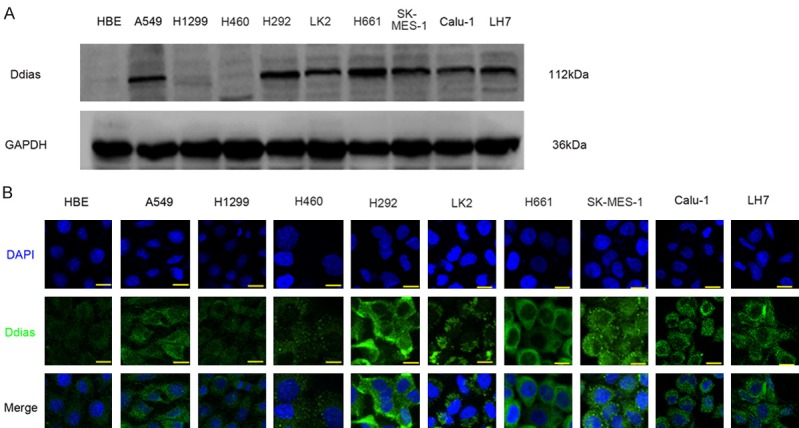

The expression and subcellular distribution of DDIAS in NSCLC cell lines

We evaluated the expression of DDIAS in 9 NSCLC cell lines and normal bronchial epithelial cell line (HBE) using western blot. The results showed that the protein level of DDIAS was higher in (7/9) NSCLC cells than that in HBE cells (Figure 4A). IF analysis revealed that DDIAS expression was detected in the cytoplasm in all the cell lines tested. The fluorescence signal was weak in HBE, H1299 and H460 cells than that in the other cells (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

DDIAS expression in NSCLC cell lines. Western blotting results (A) and immunofluorescent staining results (B) of DDIAS protein in NSCLC cell lines.

DDIAS enhanced invasion and proliferation in NSCLC cells

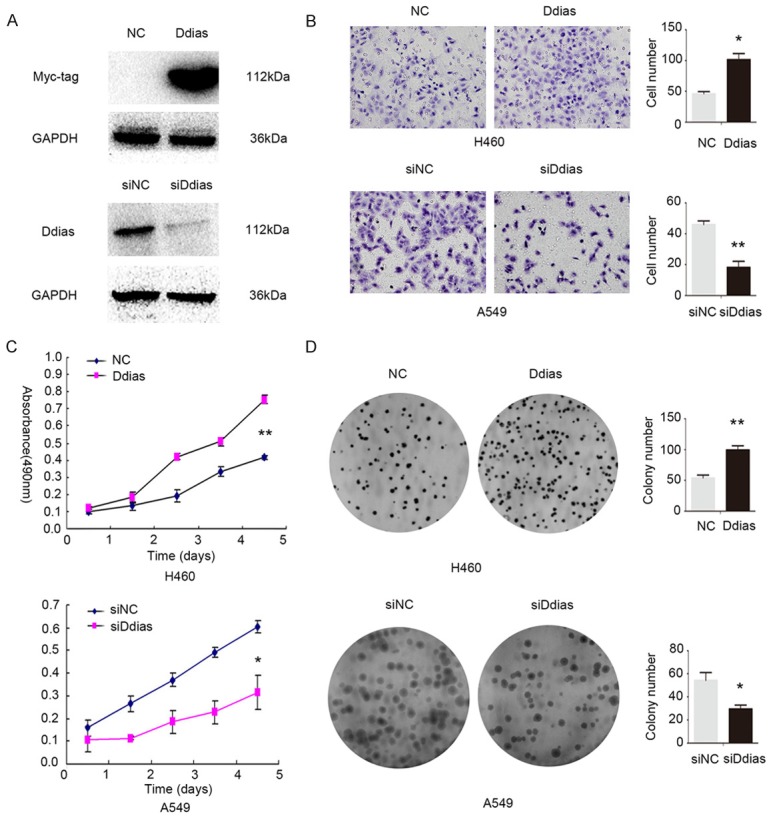

We modulated DDIAS expression by transfecting pCMV6-myc-DDIAS and DDIAS-siRNA into H460 cells and A549 cells, respectively. Empty vector and scrambled siRNA were used as controls (Figure 5A). The invasiveness of H460 cells was enhanced by transfecting pCMV6-myc-DDIAS plasmid, while the invasiveness of A549 cells was depressed after knockdown DDIAS (Figure 5B). MTT assay results showed that overexpressing DDIAS significantly upregulated the proliferative ability of H460 (P<0.001), while depleting DDIAS significantly downregulated the proliferative ability of A549 (P<0.05; Figure 5C). Colony formation assay observed similar results with MTT assay (Figure 5D).

Figure 5.

DDIAS enhance NSCLC cells invasion and proliferation. A: Western blot analysis of DDIAS protein levels after overexpression or silencing of DDIAS in H460 and A549 cells, respectively. B: After overexpressing DDIAS in H460, the invasion was significantly enhanced, after knockdown DDIAS in A549 cells, the invasion was obviously depressed. C: As measured by MTT assay, the proliferation rate was increased after DDIAS overexpression in H460 cells, and reduced after DDIAS knockdown in A549 cells. D: Colony formation assay showed that DDIAS overexpression in H460 cells significantly increased the number and the size of foci; correspondingly, depletion of DDIAS in A549 cells significantly reduced the number and the size of foci. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01.

Discussion

In our study, the identification of the association between DDIAS expression and clinicopathological features, especially clinical outcome, indicates the clinicopathological significance of DDIAS. Further analysis of the functional role of DDIAS confirms that DDIAS is not only response to stress signals but also play a role in regulating the progression and development of NSCLC.

Our results showed that DDIAS was positively expressed in the cytoplasm of NSCLC samples and cell lines. Previous studies showed that endogenous DDIAS protein was localized both in the cytoplasm (predominantly) and in the nucleus, while exogenous DDIAS localized in the nucleus of NIH3T3 cells [6]. As NIH3T3 derived from mouse embryonic fibroblast, the reason why they presented different subcellular localization may attribute to the different kinds of cell lines from different species. In our study, the positive ratio in NSCLC samples was significantly higher than that in the corresponding non-cancerous lung tissues, the protein level of DDIAS in cell lines showed a similar tendency. The results of the present study were consistent with the previous reports. DDIAS mRNA was found strongly expressed in colorectal and lung cancer tissues and DDIAS mRNA levels were higher in colorectal cancer tissues compared with normal tissues [7]. Zhang et al. also found that DDIAS mRNA levels were significantly upregulated in hepatocellular carcinoma specimens as compared with nontumor livers [10]. The previous study revealed that DDIAS expression was significantly correlated with Edmonson histology grades and portal vein tumor thrombus in hepatocellular carcinoma [10]. Our data also found that DDIAS was correlated with larger tumor size and positive regional lymph node metastasis. These collective results implied that DDIAS plays an oncogenic role and increased DDIAS expression may be involved in the progression of human cancers.

There are no studies analyzing the prognostic value of DDIAS in human cancers to date. To investigate the clinical significance of DDIAS expression in NSCLCs, we first used an online KM-plotter tool to predict the impaction of DDIAS gene expression on OS and found that DDIAS genes associated with worse OS in NSCLC patients. IHC results also showed that DDIAS expression correlated with poor survival in our cohort. We further evaluated the prognostic value of DDIAS expression using Cox regression analysis. Univariate and multivariate analysis revealed that DDIAS expression was an independent prognostic factor for OS of NSCLC patients. Moreover, positive DDIAS expression predicted a poor OS in twelve subsets of NSCLC patients defined by clinical or pathologic parameters. Therefore, DDIAS might be a useful factor for risk stratification and treatment decisions. Due to the limit of the information of treatment after surgery, our study cannot perform an analysis of progression-free survival. Further studied are required to elucidate the prognosis value of DDIAS.

DDIAS was defined as a stress-induced anti-apoptosis gene in previous studies which was the downstream molecule of p53 and NFATs (nuclear factors of activated T cells) [6-9]. Besides the anti-apoptotic effect under stress signals, we found that overexpressing DDIAS enhanced the ability of invasion and proliferation in NSCLC cells, whereas depleting DDIAS depressed the ability of invasion and proliferation in NSCLC. Our results were consistent with the previous studies. Won et al. revealed that knockdown of DDIAS inhibited the growth of colorectal and lung cancer cell lines [7]. Zhang et al. showed that overexpressing DDIAS promoted cellular proliferation, colony formation and migration of hepatocellular carcinoma cells [10]. Although the underlying mechanisms need further experiments to elucidate, our data indicate that DDIAS may be a potential oncogene for NSCLC.

In conclusion, our results suggest that positive DDIAS expression may be a potent prognostic factor in NSCLC patients. DDIAS promotes proliferation and invasion in NSCLC cells and correlated with progression of NSCLC patients. DDIAS may be a useful factor for risk stratification in NSCLC patients.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Hiroshi Kijima (Department of Pathology and Bioscience, Hirosaki University Graduate School of Medicine, Hirosaki, Japan) for providing cell lines. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81602012 to Xiupeng Zhang, No. 81472805 to Yuan Miao and No. 81402520 to Ailin Li)) and the Natural Science Foundation of Liaoning province to Yuan Miao (No. 201421044) and the Research Foundation for the Doctoral Program to Ailin Li (No. 20141040).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soon YY, Stockler MR, Askie LM, Boyer MJ. Duration of chemotherapy for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009;27:3277–3283. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.4522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams MD, Sandler AB. The epidemiology of lung cancer. Cancer Treat Res. 2001;105:31–52. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-1589-0_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hirsch FR, Suda K, Wiens J, Bunn PA Jr. New and emerging targeted treatments in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Lancet. 2016;388:1012–1024. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31473-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zappa C, Mousa SA. Non-small cell lung cancer: current treatment and future advances. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2016;5:288–300. doi: 10.21037/tlcr.2016.06.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakaya N, Hemish J, Krasnov P, Kim SY, Stasiv Y, Michurina T, Herman D, Davidoff MS, Middendorff R, Enikolopov G. Noxin, a novel stress-induced gene involved in cell cycle and apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:5430–5444. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00551-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Won KJ, Im JY, Yun CO, Chung KS, Kim YJ, Lee JS, Jung YJ, Kim BK, Song KB, Kim YH, Chun HK, Jung KE, Kim MH, Won M. Human Noxin is an anti-apoptotic protein in response to DNA damage of A549 non-small cell lung carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2014;134:2595–2604. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Im JY, Lee KW, Won KJ, Kim BK, Ban HS, Yoon SH, Lee YJ, Kim YJ, Song KB, Won M. DNA damage-induced apoptosis suppressor (DDIAS), a novel target of NFATc1, is associated with cisplatin resistance in lung cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1863:40–49. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2015.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Im JY, Lee KW, Won KJ, Kim BK, Ban HS, Yoon SH, Lee YJ, Kim YJ, Song KB, Won M. NFATc1 regulates the transcription of DNA damage-induced apoptosis suppressor. Data Brief. 2015;5:975–980. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2015.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang ZZ, Huang J, Wang YP, Cai B, Han ZG. NOXIN as a cofactor of DNA polymeraseprimase complex could promote hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2015;137:765–775. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Travis WD, Brambilla E, Burke A, Marx A, Nicholson AG. WHO classification of tumours of the lung, pleura, thymus and heart. International Agency for Research on Cancer. 2015 doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edge SB, Compton CC. The American joint committee on cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1471–1474. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0985-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gyorffy B, Surowiak P, Budczies J, Lanczky A. Online survival analysis software to assess the prognostic value of biomarkers using transcriptomic data in non-small-cell lung cancer. PLoS One. 2013;8:e82241. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]