Abstract

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are nano-sized membrane-limited organelles that are liberated from their producer cells, traverse the intercellular space, and may interact with other cells resulting in the uptake of the EV molecular payload by the recipient cells which may become functionally reprogramed as a result. Previous in vitro studies showed that EVs purified from normal mouse AML12 hepatocytes (“EVNorm”) attenuate the pro-fibrogenic activities of activated hepatic stellate cells (HSCs), a principal fibrosis-producing cell type in the liver. In a 10-day CCl4 injury model, liver fibrogenesis, expression of hepatic cellular communication network factor 2 [CCN2, also known as connective tissue growth factor (CTGF)] or alpha smooth muscle actin (αSMA) was dose-dependently blocked during concurrent administration of EVNorm. Hepatic inflammation and expression of inflammatory cytokines were also reduced by EVNorm. In a 5-week CCl4 fibrosis model in mice, interstitial collagen deposition and mRNA and/or protein for collagen 1a1, αSMA or CCN2 were suppressed following administration of EVNorm over the last 2 weeks. RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) revealed that EVNorm therapy of mice receiving CCl4 for 5 weeks resulted in significant differences [false discovery rate (FDR) <0.05] in expression of 233 CCl4-regulated hepatic genes and these were principally associated with fibrosis, cell cycle, cell division, signal transduction, extracellular matrix (ECM), heat shock, cytochromes, drug detoxification, adaptive immunity, and membrane trafficking. Selected gene candidates from these groups were verified by qRT-PCR as targets of EVNorm in CCl4-injured livers. Additionally, EVNorm administration resulted in reduced activation of p53, a predicted upstream regulator of 40% of the genes for which expression was altered by EVNorm following CCl4 liver injury. In vitro, EVs from human HepG2 hepatocytes suppressed fibrogenic gene expression in activated mouse HSC and reversed the reduced viability or proliferation of HepG2 cells or AML12 cells exposed to CCl4. Similarly, EVs produced by primary human hepatocytes (PHH) protected PHH or human LX2 HSC from CCl4-mediated changes in cell number or gene expression in vitro. These findings show that EVs from human or mouse hepatocytes regulate toxin-associated gene expression leading to therapeutic outcomes including suppression of fibrogenesis, hepatocyte damage, and/or inflammation.

Keywords: extracellular vesicle, hepatocyte, hepatic stellate cell, hepatic fibrosis, inflammation, cell cycle, extracellular matrix, exosome

Introduction

A common pathophysiological feature of chronic liver injury is the excessive production of collagen and extracellular matrix (ECM) components that become deposited as insoluble fibrotic scar material, resulting in physical and biochemical changes which can compromise essential cellular functions. Hepatic stellate cells (HSC) are the major fibrosis-producing cell type in the liver and their fibrogenic actions result from their participation in an orchestrated molecular response to sustained injury that also involves injured hepatocytes, activated resident macrophages, sinusoidal endothelial cells, and infiltrating immune cells. Many studies have documented that numerous soluble or ECM-associated signaling molecules comprise a complex regulatory network that drives and fine-tunes the fibrogenic response via autocrine, paracrine, or matricellular pathways among these various cell types. HSC function is also regulated by juxtacrine pathways that are triggered by direct cell-cell contact. In turn, these studies have highlighted the potential value of targeting components of these pathways in the development of new-generation anti-fibrotics (Ghiassi-Nejad and Friedman, 2008; Cohen-Naftaly and Friedman, 2011). However, in many cases the optimal targets, type of therapeutic agent and mode of administration have yet to be elucidated and there remain few viable options for direct anti-fibrotic therapy in patients whose liver fibrosis does not resolve upon treatment of their primary liver disease.

A newly recognized component of cell-cell communication in the liver is intercellular trafficking of molecules that are contained within nano-sized extracellular vesicles (EVs) such as exosomes or microvesicles. Whereas microvesicles are generally 200–1000 nm in diameter and are formed by budding of the plasma membrane, exosomes are typically 50–200 nm in diameter and arise by inward budding of multivesicular bodies which then fuse with the plasma membrane and cause exosomes to be released from the cell. Despite their distinct pathways of biogenesis, both exosomes and microvesicles mediate cell-cell transfer of their respective molecular payloads that can potentially cause reprograming events in recipient cells. EV cargo molecules include a broad spectrum of microRNAs, mRNAs and proteins that originate from their cells of origin and which are protected from extracellular degradation by the presence of the outer vesicular membrane which also functions to present docking proteins and receptors to recipient cells, allowing for EV uptake either by fusion with the plasma membrane or by endocytosis (Kowal et al., 2016). A role for liver-derived exosomes in fibrosis is suggested by an increase in activation or fibrogenesis in HSC after their exposure to exosomes from lipid-laden hepatocytes (Povero et al., 2015), sinusoidal endothelial cells (Wang et al., 2015), or from activated HSC themselves, the latter of which involved EV-mediated delivery of pro-fibrogenic cellular communication network factor 2 (CCN2), also known as connective tissue growth factor (CTGF; Charrier et al., 2014a; Perbal et al., 2018). However, the molecular composition of the EV molecular payload and the phenotypic status of the recipient cells are critical determinants of how EV action is manifested in the context of liver fibrosis. For example, we have shown that quiescent HSC produce exosomes that attenuate pathways of activation or fibrogenesis in activated HSC due to exosomal transfer into the recipient cells of miR-214 or miR-199a-5p which directly inhibit transcription of CCN2, thus suppressing downstream alpha smooth muscle actin (αSMA) or collagen production and reverting the cells to a more quiescent phenotype (Chen et al., 2014, 2015, 2016b). Hence the molecular cargo in exosomes from HSC may be pro- or anti-fibrogenic depending on the differential activation status of producer versus recipient cell. Similarly, EVs produced by fat-laden hepatocytes drive pro-fibrogenic pathways in HSC (Povero et al., 2015) whereas we recently showed that EVs from normal hepatocytes bind to HSC in vivo and have suppressive actions on activated HSC in vitro (Chen et al., 2018a). In pursuing the latter findings, we now report that EVs from hepatocytes have anti-fibrotic actions in vivo that are associated with attenuated HSC activation and fibrogenesis, hepatocyte recovery, reduced levels of hepatic monocytes and macrophages, and attenuated expression of inflammatory mediators, ECM components, detoxifying cytochromes, and regulators of cell division. These findings reveal that EVs from hepatocytes have previously unrecognized therapeutic actions in the liver.

Materials and Methods

CCl4-Induced Hepatic Fibrogenesis in Mice

Animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Nationwide Children’s Hospital (Columbus, OH, United States). Male Swiss Webster wild type mice or transgenic (TG) Swiss Webster mice expressing enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) under the control of the promoter for CCN2 (TG CCN2-EGFP (Charrier et al., 2014b); (4–5 weeks old; n = 5 per group) were injected i.p. with carbon tetrachloride (CCl4; 4 μl in 26 μl corn oil/25 g body weight; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States) on Days 1, 3, 5, and 8. Control mice received i.p. corn oil (30 μl/25 g) on the same days. Some mice received i.p. mouse hepatocyte EVs (prepared as described below; 0–80 μg EV protein per 25 g body weight) on Days 2, 4, 6, and 9. Mice were sacrificed 2 days after the last injection and liver lobes were either perfused with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and processed for histological analysis or immediately harvested for EGFP imaging using a Xenogen IVIS 200 (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, United States) or snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen for later RNA or protein extraction.

CCl4-Induced Hepatic Fibrosis in Mice

Wild-type male Swiss Webster mice (4–5 weeks old; n = 5 per group) were injected i.p. with CCl4 (4 μl in 26 μl corn oil/25 g) or corn oil (30 μl/25 g) three times per week for 5 weeks. On alternative days to those used for CCl4 or oil administration, some mice received i.p. EV (0–80 μg/25 g) three times per week over the last 2 weeks of the experiment. Mice were sacrificed 36 h after the last CCl4 or oil injection, or in non-treated littermates. Individual liver lobes were harvested and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen for subsequent RNA extraction or perfused using PBS followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich) for histological analysis of fixed tissue.

Histology

Perfused mouse livers were fixed and embedded in paraffin. Sections of 5 μm thickness were cut and stained with H and E. Sections were stained with 0.1% Sirius Red (Sigma-Aldrich) for detection of collagen or subjected to immunohistochemistry (IHC) (see below). Positive signals were quantified by image analysis.

Hepatocyte Cultures

AML12 mouse hepatocytes [American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), Manassas, VA, United States] were maintained in vitro in DMEM/F12/10% FBS containing insulin, transferrin, selenium and dexamethasone (Chen et al., 2015). HepG2 cells (ATCC) were maintained in DMEM/10% FBS. Primary human hepatocytes (PHH; IVAL LLC, Columbia, MA, United States) were cultured in Universal Primary Cell Plating Medium (IVAL) according to the vendors’ directions.

Hepatic Stellate Cell Cultures

Primary mouse HSC were isolated from male wild-type Swiss Webster mice (6–8 week) by perfusion and digestion of livers with pronase/collagenase, followed by buoyant-density centrifugation (Ghosh and Sil, 2006; Chen et al., 2011, 2016b). The cells were maintained in Gibco DMEM/F12/10% FBS medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States) and split every 5 days for use up to passage 4 (P4). Freshly isolated quiescent HSC contained lipid droplets that we previously showed to express desmin or Twist1 but not CCN2, αSMA or collagen 1a1 (Col1a1) whereas cells that autonomously activated over the first week of culture expressed desmin, CCN2, αSMA or Col1a1, but not Twist1 (Chen et al., 2011, 2015). LX-2 human HSC (courtesy of Dr. Scott Friedman, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, United States) were cultured in DMEM/10% FBS as described (Chen et al., 2011, 2015).

Hepatocyte EV Purification

Prior to collecting EVs from the conditioned medium of mouse or human hepatocytes, spent medium was removed, and the cells were rinsed twice with Hanks Balanced Salt Solution prior to incubation overnight in their respective serum-free medium which was then replaced with fresh serum-free medium for up to 48 h. The supernatant obtained from sequential centrifugation of conditioned medium (300 × g for 15 min, 2,000 × g for 20 min, 10,000 × g for 30 min) underwent ultracentrifugation (100,000 × g for 70 min at 4°C) in a T-70i fixed-angle rotor (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, United States), the pellet from which was resuspended in PBS and subjected to the same ultracentrifugation conditions again. The resulting pellet was dispersed in PBS and the constituent EVs were characterized as described below. AML12 cell-derived EVs are hereafter termed “EVNorm” since they were produced under essentially normal culture conditions as opposed to other EV studies involving hepatocyte injury or stress (Povero et al., 2013, 2015; Momen-Heravi et al., 2015; Hirsova et al., 2016a; Ibrahim et al., 2016; Verma et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2017).

Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA)

EVs in PBS (107–108 particles/ml) were subjected to nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) using a Nanosight 300 (Malvern Instruments, Westborough, MA, United States) that had been calibrated with 100 nm polystyrene latex microspheres (Magsphere Inc., Pasadena, CA, United States) diluted in PBS to a fixed concentration. EV samples were each analyzed twice and v3.2.16 analytical software (Malvern Instruments) was used to estimate mean particle concentration and size. Recordings were performed at room temperature with a camera gain of 15 and a shutter speed of 4.13 ms. The detection threshold was set to 6.

Transmission Electron Microscopy

EVNorm were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 30 min and pelleted by ultracentrifugation. They were then placed on 200-mesh copper grids that had been coated with Formvar/Carbon support film (Ted Pella, Redding, CA, United States) and glow-discharged with a PELCO easiGlow discharge cleaning system (Ted Pella). EVs were negatively stained with 1% aqueous uranyl acetate and examined by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) using a FEI Tecnai G2 Biotwin instrument (Atlanta, GA, United States) operating at 80 kV. Digital micrographs were captured using an AMT camera with FEI imaging software.

EV Cell Binding Assays

Primary human hepatocytes-derived EVs were labeled with the fluorescent lipophilic membrane dye PKH26 (Sigma-Aldrich) essentially as previously described (Chen et al., 2018a) and incubated in a 96-well culture plate at 2 × 109 particles/ml for 24 h with PHHs (on collagen-coated wells) or LX-2 cells that had been exposed to 20 mM CCl4 for the preceding 24 h. Cells were stained with DAPI, rinsed in PBS, and EV binding was assessed using a LSM 800 fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss Inc., Thornwood, NY, United States) and quantified using ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, United States).

Effect of Hepatocyte EVs on Hepatocyte or HSC Function in vitro

HepG2 cells, PHHs, or human LX2 HSC were incubated for 24 h in their respective normal growth media prior to being placed under fresh serum-free conditions in the presence or absence of 20 mM CCl4 for 48 h, the last 24 h of which included incubation with or without EVs from HepG2 cells or PHHs (8–16 μg/ml or 2–4 × 108 particles/ml, respectively). Cells were assessed for cell proliferation using a CyQUANT® assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific) or for viability using an AlamarBlue assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific). For gene expression studies, PHHs, LX2 cells, or mouse P3-4 HSC were placed in fresh serum-free medium overnight prior to treatment with EVs from HepG2 cells (8 μg/ml) or PHHs (4 × 108 particles/ml) for 36–48 h in the presence or absence of 20 mM CCl4 prior to analysis by RT-PCR.

Iodixanol Gradient Ultracentrifugation

PKH26-labeled EVs in 200 μl PBS were loaded on to a 5 ml stepwise gradient of 8, 16, 24, 32, and 40% iodixanol followed by ultracentrifugation at 37,500 rpm (SW55 Ti rotor, Beckman) for 17 h at 4°C. The tube contents were collected from top to bottom into 20 fractions which were assessed for iodixanol concentration using an Abbe refractometer (Bausch and Lomb, Rochester, NY, United States) and PKH26 fluorescence (Ex/Em = 540/585 nm, cut-off = 570 nm) using a Spectra Max M2 spectrophotometer (VWR, Atlanta, GA, United States). The fraction containing the peak PKH26 signal was then assessed for its ability to modulate gene expression in activated mouse HSC.

Protein Assay

A Pierce bicinchoninic acid assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used to quantify protein concentrations of EVs in PBS or of liver tissue proteins that had been extracted using Pierce radioimmunoprecipitation buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Immunohistochemistry

Mouse liver sections were incubated with primary antibodies to F4/80 (1:100, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, United States), Ly6c (1:400, Abcam), collagen 1 (1:250, Abcam), αSMA (1:500; Thermo Fisher Scientific), or CCN2 [in-house; 5 μg/ml (Charrier and Brigstock, 2010; Charrier et al., 2014b)] followed by Alexa Fluor 488 goat-anti rabbit IgG and Alexa Fluor 568 goat-anti mouse IgG, or Alexa Fluor 647 goat-anti mouse IgG, or Alexa Fluor 568 goat-anti-chicken IgG (all at 1:500; Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 1 h at room temperature. The slides were mounted with Vectashield Mounting Medium containing 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole nuclear stain (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, United States), and examined by confocal microscopy. Activated HSC were identified by positive immunostaining for CCN2, αSMA and/or Col1a1.

Mouse Cytokine Microarray

A mouse cytokine proteome profilerTM array (Panel A kit; R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, United States) was incubated with detergent lysates (320 μg/ml) of pooled liver tissue from acute CCl4 injury in male Swiss Webster mice (short-term fibrogenesis model) with or without EVNorm treatment, as described above (n = 3 or 4 mice per group). Arrays were developed using chemiluminescence and the mean pixel intensity of duplicate component spots was quantified using ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD, United States). Targets showing significant changes in intensity in response to CCl4 and EVNorm were tested for their corresponding RNA expression by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR).

Western Blot

Proteins in liver tissue extracts or hepatocyte EVs were subjected to sodium dodecyl polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE; 10–25 μg protein/lane). Depending on the sample in question, Western blots were performed to detect proteins associated with EVs, cytosol, or liver fibrosis. Blots were incubated with primary antibodies to CD9 (1:500; Abcam), Alix (1:500; Thermo Fisher Scientific), TSG101 (1:500; Thermo Fisher Scientific), flotillin-1 (1:200; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, United States), CD63 (1:100; Millipore Sigma, Burlington, MA, United States), calnexin (1:500; Novus Biologicals, Centennial, CO, United States), calreticulin (1:500; Novus Biologicals, United States), p53 (1:1,000; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, United States), phopho-p53 at Ser15 (1:1,000; Cell Signaling) or β-actin (1:1,000; Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, United States). Blots were developed using an Odyssey Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE) and signals were normalized relative to β-actin for quantification using ImageJ (NIH).

RNA Sequencing

RNA-seq libraries from mouse livers (long-term fibrosis model with n = 3 per group for control, oil, oil + EVNorm, CCl4, or CCl4 + EVNorm) were prepared using the TruSeq Stranded protocol (Illumina, San Diego, CA, United States). Following assessment of the quality of total RNA using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer and RNA Nano chip (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, United States), 100 ng mouse liver total RNA was treated with a Ribo-zero Human/Mouse/Rat Gold kit (Illumina) to deplete the levels of cytoplasmic and mitochondrial ribosomal RNA (rRNA) using biotinylated, target-specific oligos combined with rRNA removal beads. Following rRNA removal, mRNA was fragmented using divalent cations under elevated temperature and converted into double stranded cDNA. Incorporation of dUTP in place of dTTP during second strand synthesis inhibited the amplification of the second strand. The subsequent addition of a single “A” base allowed for ligation of unique, dual-indexed adapters with unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA, United States). Adaptor-ligated cDNA was amplified by limit-cycle PCR. Quality of libraries were determined via Agilent 4200 Tapestation using a High Sensitivity D1000 ScreenTape Assay kit (Agilent Technologies), and quantified by KAPA qPCR (KAPA Biosystems, Woburn, MA, United States). Approximately 60–80 million paired-end 150 bp sequence reads were generated for each library on the Illumina HiSeq 4000 platform. For data analysis, each sample was aligned to the GRCm38.p3 assembly of the Mus musculus reference from NCBI using version 2.6.0c of the RNA-seq aligner STAR (Dobin et al., 2013). Features were identified from the GFF file that came with the assembly from Gencode (Release M19). Feature coverage counts were calculated using featureCounts (Liao et al., 2014). Differentially expressed features were calculated using DESeq2 (Love et al., 2014) and significant differential expressions were those with an adjusted P-value [i.e., false discovery rate (FDR)] of <0.05.

Gene Ontology and Pathway Enrichment Analyses

Grouping of target genes into molecular functions, biological processes, or cellular components was achieved by gene ontology (GO) analysis1 based on the DAVID database2. The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)3 was used to understand high-level biological functions and utilities. Genes were also functionally grouped using Reactome4. Upstream factor analysis of the gene lists was carried out using the Ingenuity Pathway System (Qiagen, Redwood City, CA, United States). These analyses were each performed with a criterion FDR <0.05.

Protein–Protein Interaction (PPI) Network Construction

To analyze the physical and/or functional interactions among the proteins encoded by identified differentially expressed genes (DEGs), DEGs were uploaded to the online program Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes (STRING)5, and results with a minimum interaction score of 0.4 were collated. Clustering was done using the Markov Cluster Algorithm method with an inflation parameter of 2.

RNA Extraction and RT-qPCR

Total RNA from liver tissues or cultured hepatocytes was extracted using a miRNeasy mini kit (Qiagen) and reverse transcribed using a miScript II RT kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Transcripts were evaluated by qRT-PCR using an Eppendorf Mastercycler System and SYBR Green Master Mix (Eppendorf, Hauppauge, NY, United States). Primers are shown in Table 1. Each reaction was run in duplicate, and samples were normalized to GAPDH mRNA or 18S rRNA. Negative controls were a non-reverse transcriptase reaction and a non-sample reaction.

TABLE 1.

Primers used for qRT-PCR.

| Gene ID | Accession no. |

Primer |

Length (bp) | |

| Fwd Seq (5′–3′) | Rev Seq (5′–3′) | |||

| Col3a1 (mouse) | NM_009930 | GCCCACAGCCTTCTACACCT | GCCAGGGTCACCATTTCTC | 110 |

| LTBP1 (mouse) | NM_019919 | TCAGAACAGCTGCCAGAAGG | GGCCACCATTCATACACGGA | 125 |

| MMP2 (mouse) | NM_008610 | GCAGCTGTACAGACACTGGT | ACAGCTGTTGTAGGAGGTGC | 182 |

| Serpinh1 (mouse) | NM_009825 | GCCGAGGTGAAGAAACCCC | CATCGCCTGATATAGGCTGAAG | 120 |

| Serpinhb8 (mouse) | NM_011459 | GTGAAGCCAATGGGTCTTTTGC | CAGAAGAACAGGTTTCGTGACT | 79 |

| Reln (mouse) | MMU24703 | TTACTCGCACCTTGCTGAAAT | CAGTTGCTGGTAGGAGTCAAAG | 73 |

| Lum (mouse) | NM_008524 | CTCTTGCCTTGGCATTAGTCG | GGGGGCAGTTACATTCTGGTG | 114 |

| CCN2 (mouse) | NM_010217 | CACTCTGCCAGTGGAGTTCA | AAGATGTCATTGTCCCCAGG | 111 |

| Col1a1 (mouse) | NM_007742 | GCCCGAACCCCAAGGAAAAGAAGC | CTGGGAGGCCTCGGTGGACATTAG | 148 |

| αSMA (mouse) | NM_007392 | GGCTCTGGGCTCTGTAAGG | CTCTTGCTCTGGGCTTCATC | 148 |

| CCNB1 (mouse) | NM_172301 | AAGGTGCCTGTGTGTGAACC | GTCAGCCCCATCATCTGCG | 228 |

| ccnb2 (mouse) | NM_007630 | GCCAAGAGCCATGTGACTATC | CAGAGCTGGTACTTTGGTGTTC | 114 |

| cdc25c (mouse) | NM_009860 | ATGTCTACAGGACCTATCCCAC | ACCTAAAACTGGGTGCTGAAAC | 67 |

| cdk1 (mouse) | NM_007659 | AGAAGGTACTTACGGTGTGGT | GAGAGATTTCCCGAATTGCAGT | 128 |

| KIF2C (mouse) | NM_134471 | ATGGAGTCGCTTCACGCAC | CCACCGAAACACAGGATTTCTC | 121 |

| CYP20A1 (mouse) | NM_030013 | TGCAAGGTTGTGTACCTGGAC | TGATAGGACCCTCCCCTAAAAC | 104 |

| CYP2C55 (mouse) | NM_028089 | AATGATCTGGGGGTGATTTTCAG | GCGATCCTCGATGCTCCTC | 111 |

| CYP4A31 (mouse) | NM_201640 | AGCAGTTCCCATCACCGCC | TGCTGGAACCATGACTGTCCGTT | 276 |

| CCL12 (mouse) | NM_011331 | GTCCTCAGGTATTGGCTGGA | GGGTCAGCACAGATCTCCTT | 181 |

| CCL3 (mouse) | NM_011337 | TGAAACCAGCAGCCTTTGCTC | AGGCATTCAGTTCCAGGTCAGTG | 125 |

| CCL5 (mouse) | NM_013653 | AGATCTCTGCAGCTGCCCTCA | GGAGCACTTGCTGCTGGTGTAG | 170 |

| TIMP-1 (mouse) | NM_001044384 | CCTATAGTGCTGGCTGTGGG | GCAAAGTGACGGCTCTGGTA | 136 |

| TREM-1 (mouse) | AF241219 | CCCTAGTGAGGCCATGCTAC | GGAAGAGCACAACAGGGTCA | 110 |

| CCN2 (human) | NM_001901 | AATGCTGCGAGGAGTGGGT | GGCTCTAATCATAGTTGGGTCT | 115 |

| Col1a1 (human) | NM_000088 | GAACGCGTGTCATCCCTTGT | GAACGAGGTAGTCTTTCAGCAACA | 91 |

| HNF4α (human) | NM_178849 | ACAGCAGCCTGCCCTCCAT | GCTCCTTCATGGACTCACACAC | 143 |

| Albumin (human) | A06977 | TGCTATGCCAAAGTGTTCGATG | TTGGAGTTGACACTTGGGGT | 159 |

| CYP7A1 (human) | NM_000780 | GCTACTTCTGCGAAGGCATTT | CATCATGCTTTCCGTGAGGG | 131 |

| 18S (mouse, human) | X03205 | GGTGAAATTCTTGGACCGGC | GACTTTGGTTTCCCGGAAGC | 196 |

| GAPDH (mouse, human) | NM_002046 | TGCACCACCAACTGCTTAGC | GGCATGGACTGTGGTCATGAG | 87 |

Statistical Analysis

Experiments were performed at least twice in duplicate or triplicate, with data expressed as mean ± SEM. Fluorescence images were scanned and quantified using ImageJ software (NIH). Data from qRT-PCR, NTA, and imaging were analyzed by student’s t-test using Sigma plot 11.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). Statistics for RNA-seq analysis are described above. P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Characterization of EVs From Mouse AML12 Hepatocytes

AML12 hepatocyte EVs (“EVNorm”) isolated from 36 to 48-h conditioned medium under serum-free conditions had a mean diameter of 110 ± 2.5 nm with a size range of approximately 50–300 nm as assessed by NTA (Figure 1A). Western blot confirmed the presence of EV-associated proteins such as CD9, CD63, Alix, flotillin, and TSG101 (Figure 1B and Supplementary Figure 1) and we have previously reported that these EVs are also positive for asialoglycoprotein receptor (Chen et al., 2018a) which is expressed exclusively in hepatocytes and has been used by others to characterize or identify hepatocyte-derived EVs (Rega-Kaun et al., 2019). Moreover, whereas calreticulin or calnexin were readily detected in AML-12 cell lysates, they were not detected in EVNorm demonstrating that the EV preparations were not overtly contaminated with cytoplasmic or cytosolic components (Figure 1B). A very similar size range to that determined by NTA was obtained by TEM which also confirmed the vesicular nature of the purified nanoparticles (Figure 1C). As assessed by NTA of conditioned medium from AML12 cells that was removed and replenished at fixed time points during cell culture, there was a consistent output of EVNorm when the cells were maintained in serum-free conditions for up to 48 h (Figure 1D). This demonstrated that the cell culture conditions did not compromise EVNorm production and hence for the experiments described below, EVNorm were collected from AML12 cells that had been maintained in serum-free conditions for up to 48 h in culture.

FIGURE 1.

Characterization of mouse hepatocyte-derived EVs. Mouse AML12 hepatocytes were grown under serum-free conditions for 36 h after which EVNorm were isolated by ultra-centrifugation of conditioned medium and characterized by (A) NTA [mean ± SEM for particle diameter (nm) is indicated]; (B) comparative Western blot with AML12 cell lysates for common EV- or cell-associated proteins (25 μg EV or cellular protein per lane; uncropped data are shown in Supplementary Figure 1); or (C) TEM (×56,000; scale bar = 100 nm). (D) EV concentration in conditioned medium from AML12 cells that were maintained under serum-free conditions for 16 h, 24 h (with a medium exchange at 16 h), 40 h (with medium exchanges at 16 and 24 h), or 48 h (with medium exchanges at 16, 24, and 40 h). The mean EV output per cell per hour over 0–16, 16–24, 24–40, or 40–48 h was computed by expressing particle number at each collection (from NTA analysis) as a function of the cell number (from cell count at each collection time) and the duration of the incubation for EV collection (8 or 16 h).

Therapeutic Effects of EVNorm in vivo

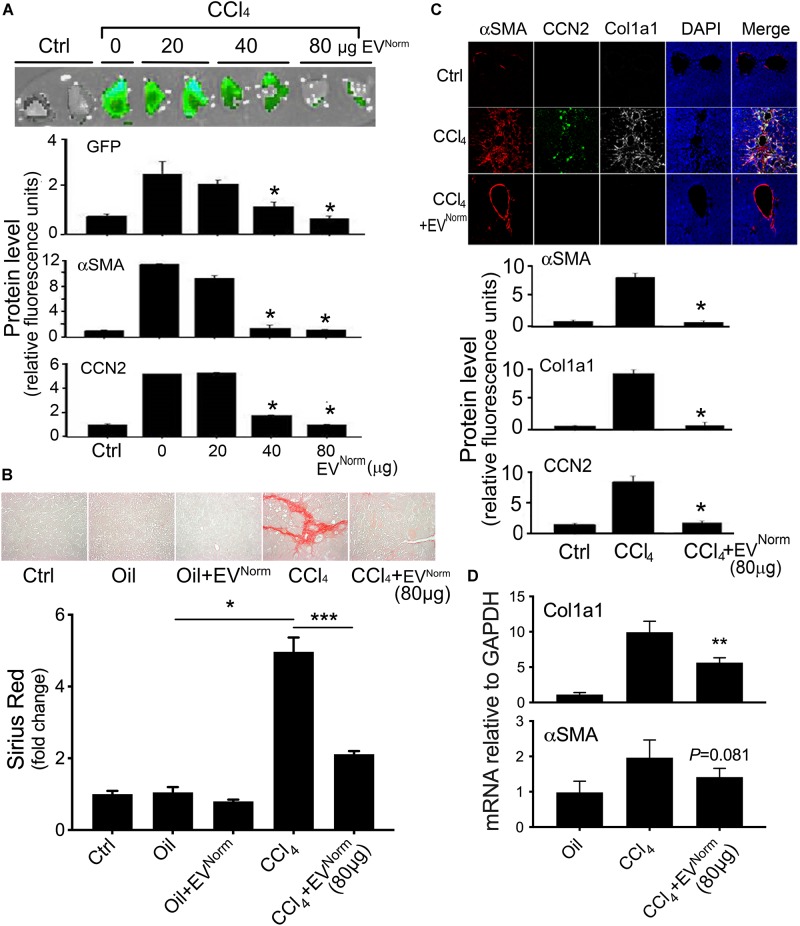

The effects of EVNorm on fibrosing liver injury were analyzed in mice exposed to CCl4 which is a widely used means of inducing fibrotic responses in the rodent liver (Constandinou et al., 2005). First, as assessed by direct Xenogen imaging of GFP fluorescence in whole liver pieces, the induction of pro-fibrotic CCN2 in male TG CCN2-EGFP mice that were exposed to acute CCl4 injury over 8 days was dose-dependently reduced by administration of EVNorm (Figure 2A). Dose-dependent suppression by EVNorm on CCl4-induced EGFP, CCN2, or αSMA levels was also evident by immunohistochemical analysis of liver tissue sections (Figure 2A). The most effective EVNorm dose (80 μg/25 g) was next tested for its effect in male wild-type Swiss Webster mice receiving CCl4 for 5 weeks, a chronic injury model which elevates serum levels of alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase (Chen et al., 2018b). Hepatic fibrosis assessed by Sirius Red staining of interstitial collagen (Figure 2B) was attenuated to near-baseline levels by i.p. administration of EVNorm over the last 2 weeks of the experiment and this was associated with reduced levels of CCl4-induced protein levels of αSMA, CCN2, or Col1a1 assessed by immunostaining (Figure 2C). CCl4 also caused a significant increase in hepatic Col1a1 mRNA expression that was attenuated in the presence of EVNorm and a similar but non-significant trend was also seen for αSMA (Figure 2D). We further found that inflammatory responses to CCl4 as evidenced by increased hepatic monocyte (lyc6+) or macrophage (F4/80+) frequency was suppressed by EVNorm (Figure 3A). Protein microarray analysis (not shown) indicated that EVNorm dampened the CCl4-induced levels of tissue inhibitor of metalloprotease-1 (TIMP-1) and of the pro-inflammatory factors C-C motif chemokine ligand (CCL)3, CCL5, and CCL12, all except the latter of which have been previously shown to be associated with inflammation and fibrosis of the liver (Berres et al., 2010; Heinrichs et al., 2013; Thiele et al., 2017). Accordingly, the same targets were analyzed by RT-PCR with the result that expression of their respective CCl4-induced mRNAs was found to be suppressed by EVNorm (Figure 3B). A similar trend but one that did not reach statistical significance occurred for triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 1 (TREM-1) (Figure 3B), which was recently reported to drive Kupffer cell activation, inflammation and fibrosis (Nguyen-Lefebvre et al., 2018).

FIGURE 2.

Therapeutic effects of EVNorm in CCl4-mediated liver fibrogenesis or fibrosis. (A) TG CCN2-GFP mice received oil (Ctrl) or CCl4 over 8 days and EVNorm (0–80 μg i.p. q.o.d.) on the “off days” until Day 9. Animals were sacrificed two days after the last injection. Pieces of fresh liver lobe were imaged for GFP (upper) while liver sections were stained for GFP, αSMA or CCN2 by IHC with fluorescence for each protein quantified by imaging (lower) (∗P < 0.05 vs. CCl4 + 0 μg EV). (B) Wild type Swiss Webster mice received 5 weeks of oil or CCl4, with or without EVNorm (80 μg/25 g i.p. q.o.d.) over the last 2 weeks. The figure shows Sirius red staining of representative liver sections (upper) and quantification of the staining (lower; ∗P < 0.05; ∗∗∗P < 0.005). (C) Immunohistochemical detection of Col1a1, αSMA or CCN2 in liver sections (upper) and the quantified fluorescent signal assessed by scanning (lower) (∗P < 0.05 vs. CCl4). The residual staining for αSMA in the CCl4 + EVNorm group reflects constitutive production of αSMA by vascular smooth muscle rather induced production in activated HSC. (D) qRT-PCR for Col1a1 or αSMA of total liver RNA (∗∗P < 0.01 vs. CCl4).

FIGURE 3.

Anti-inflammatory effects of EVNorm in CCl4-mediated liver injury. Wild type male Swiss Webster mice (n = 5) received oil or CCl4 i.p. for 9 days, with or without i.p. administration of 80 μg EVNorm/25 g. The figure shows (A) typical immunofluorescent detection of Ly6c (monocytes) or F4/80 (macrophages) (left; scale bar 50 μm), with data quantified using ImageJ software (right; each data point represents one liver section); and (B) mRNA expression assessed by qRT-PCR of inflammation- or fibrosis-related molecules in the liver extracts. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.005.

RNA-Seq Analysis of EVNorm-Mediated Effects on Gene Expression During CCl4 Liver Injury

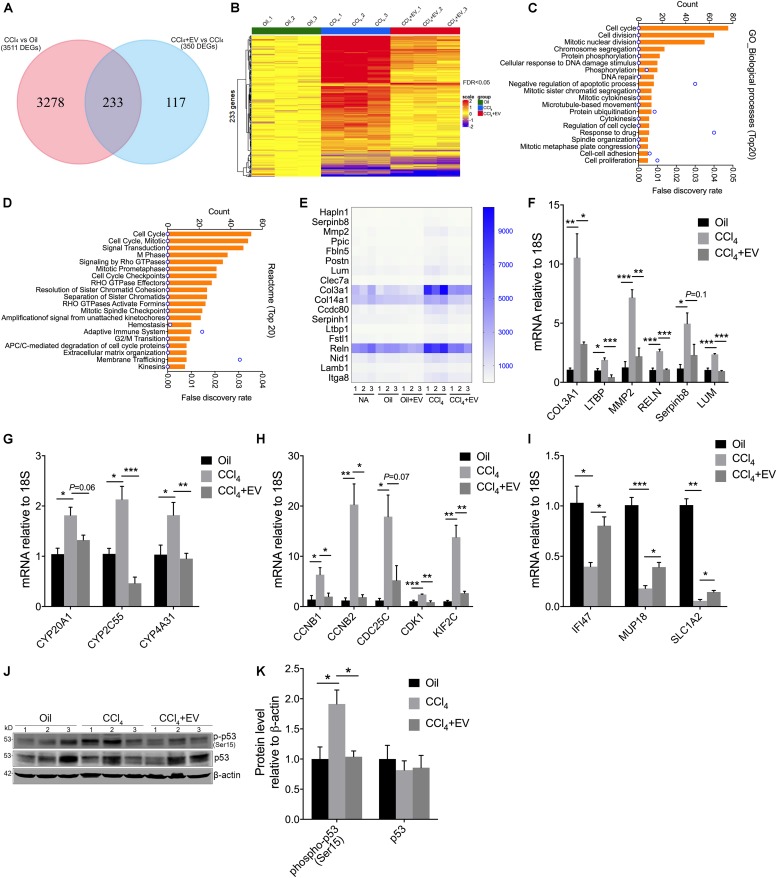

Although our primary analysis was focused on the ability of EVNorm to exert anti-fibrogenic, anti-fibrotic, and anti-inflammatory activities during liver injury in vivo, we next performed RNA-seq of liver tissue RNA to investigate potential broader effects of EVNorm on CCl4-modulated hepatic gene expression. Significant (FDR < 0.05) up- or down-regulated expression of 3511 genes occurred in response to CCl4, 233 of which were significantly altered by EVNorm (Supplementary Table 1 and Figure 4A). The differential expression of these 233 genes is represented in the heatmap shown in Figure 4B and comprised 191 genes and 42 genes that were, respectively, induced or suppressed by CCl4. GO (Figure 4C) and Reactome pathway (Figure 4D) analyses both indicated a significant enrichment in functions involving cell cycle or cell division, drug metabolism/detoxification, cell-cell adhesion/ECM, signal transduction, adaptive immunity, and membrane trafficking. These enrichments were consistent with the outcome of STRING analysis which revealed four major interactive clusters comprising 128 cell cycle/division-related genes, 18 ECM-related genes, 6 heat shock genes, 7 cytochrome genes, and 8 other detoxifying genes (Supplementary Figure 2). Since six genes in the ECM-related group (Figure 4E) (Col3a1, LTBP, MMP2, RELN, Serpinb8, LUM) have been reported to be involved in fibrogenesis (Preaux et al., 1999; Breitkopf et al., 2001; Krishnan et al., 2012; Alvarez Rojas et al., 2015; Carotti et al., 2017; Zhan et al., 2019), we used qRT-PCR to independently validate the ability of EVNorm to dampen CCl4-induced expression of each of these transcripts (Figure 4F). All targets were significantly suppressed by EVNorm (except Serpinb8 which nonetheless trended downward) thus confirming and extending the anti-fibrogenic properties reported above. qRT-PCR was also used to confirm the ability of EVNorm to suppress CCl4-induced expression of cytochromes (CYP2C55, CYP4A31; Figure 4G) and of several randomly selected members of the cell cycle/cell division-related group (CCNB1, CCNB2, CDK1, KIF2C; Figure 4H), and with some targets (CYP20A1, CDC25C) showing downward but non-significant trends in expression by EVNorm. We also selected three CCl4-suppressed genes (IFI47, MUP18, SLC1A2) for qRT-PCR validation and confirmed the ability of EVNorm to partially but significantly reverse their inhibited expression by CCl4. (Figure 4I). Finally, p53 – a CCl4-indicible tumor suppressor gene that regulates cell cycle, apoptosis, and genomic stability (Guo et al., 2013; Elgawish et al., 2015) – was ranked in first position by Ingenuity pathway analysis as a predicted upstream regulator of 40% of the EVNorm DEGs (i.e., 91 of 233 genes) in CCl4 liver injury (Supplementary Figure 3). Consistent with this prediction, Western blot analysis of liver tissue extracts revealed that the level of CCl4-enhanced phospho-p53 was attenuated by EVNorm (Figures 4J,K).

FIGURE 4.

Transcriptomic changes by EVNorm in long-term CCl4-mediated liver injury. Liver tissues from wild type Swiss Webster mice that were control or received 5 weeks of oil or CCl4, with or without EVNorm (80 μg/25 g i.p. qod) over the last 2 weeks, were subjected to transcriptome analysis by RNA-seq as described in Methods. (A) Venn diagram showing DEGs between CCl4 vs. oil and CCl4 + EVNorm vs. CCl4. (B) Heatmap showing pattern of expression of 233 DEGs identified in each animal of each experimental group. (C) Gene ontology (biological processes) analysis of the 233 DEGs showing the top 20 enriched biological processes. (D) Top 20 Reactome pathways of the 233 DEGs. (E) Heat map showing differential expression of interacting ECM-related genes identified by STRING analysis (see Supplementary Figure 2). qRT-PCR showing the effect of EVNorm on either hepatic expression of CCl4-induced (F) fibrosis-related ECM genes, (G) cytochromes, (H) cell cycle-related genes, or on (I) CCl4-suppressed genes. (J) Liver tissue levels of total p53 or phopho-p53 detected by Western blot in light of identification of p53 by Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (Supplementary Figure 3). (K) Quantification of data in panel (J) using ImageJ. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.005.

Characterization and Biological Effects of EVs From Human Hepatocytes

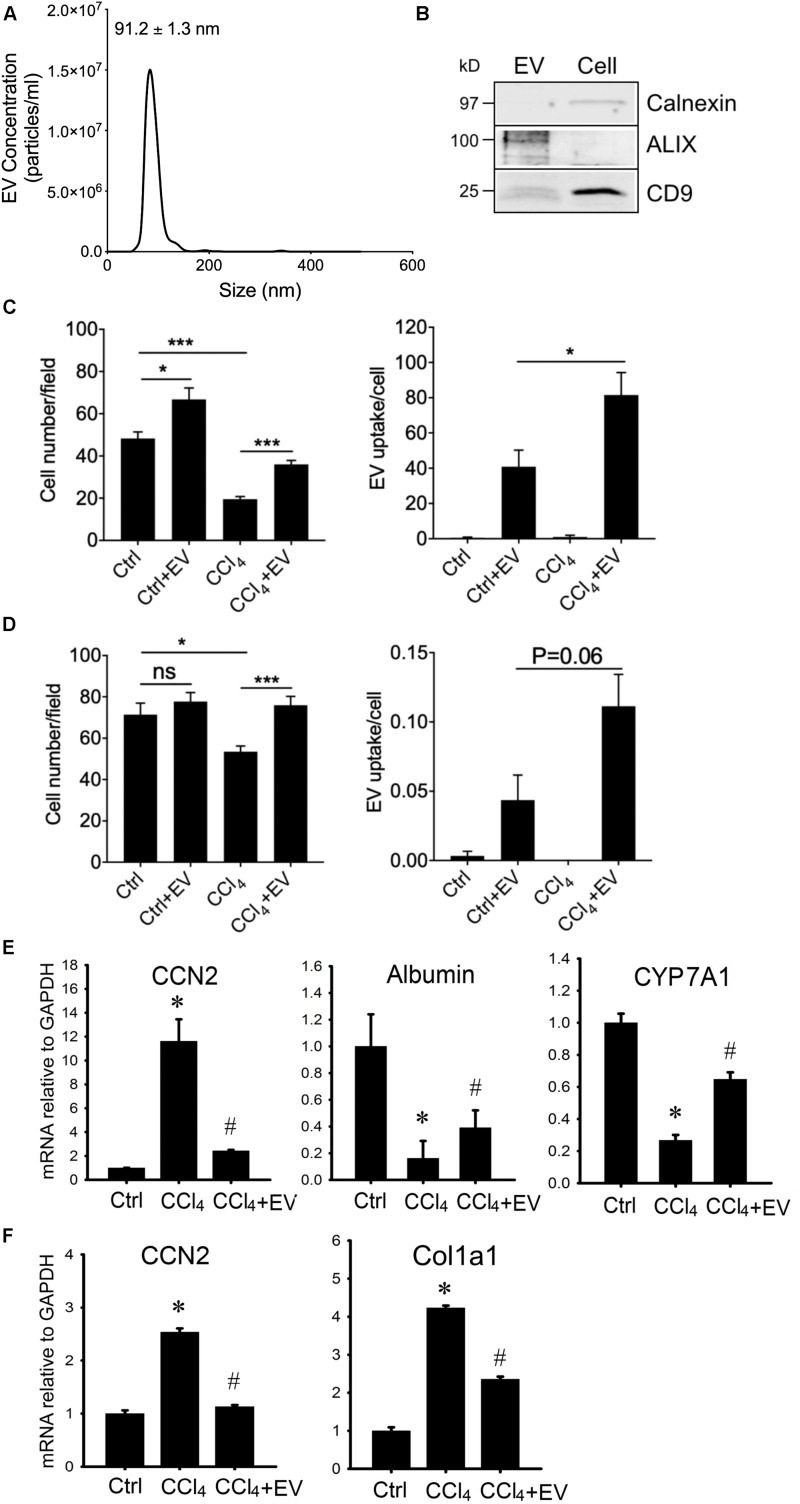

To substantiate that human hepatocyte EVs exert similar effects in vitro as their mouse counterparts, we first characterized EVs from the immortalized non-tumorigenic human HepG2 hepatocyte cell line. HepG2 cell-derived EVs purified from serum-free conditioned medium had a mean diameter of 91.2 ± 1.3 nm, with the majority of particles falling in the 50–150 nm range (Figure 5A). The EVs were positive by Western blot analysis for a variety of EV-associated proteins but the cytosol-associated protein calnexin was absent from EVs and restricted to cell lysates (Figure 5A). When incubated with activated mouse HSC in vitro, the HepG2 cell-derived EVs caused the transcript levels of αSMA, Col1a1 or CCN2 to be significantly suppressed (Figure 5B). To confirm that these responses were most likely attributable to the purified EVs themselves rather than a contaminant, the HepG2 cell-derived EVs were further enriched using an iodixanol gradient (Figure 5C) after which their ability to inhibit gene expression in HSC was shown to be essentially maintained (Figure 5D).

FIGURE 5.

Characterization and actions of EVs from HepG2 cells. (A) EVs from 48-hr HepG2 cell conditioned medium (serum-free) were analyzed by NTA or Western blotting (inset, with comparison to HepG2 cell lysate; 10 μg EV or cellular protein per lane). (B) P3-4 mouse HSC were incubated for 42 h in the absence or presence of HepG2 cell-derived EVs (8 μg/ml) and then analyzed by RT-PCR for expression of CCN2, αSMA, or Col1a1. (C) PKH26-labeled EVs underwent iodixanol gradient centrifugation and (D) the peak fluorescent fraction was tested on mouse HSC as in panel (B). (E) AlamarBlue viability assay or (F) CyQuant proliferation assay of HepG2 cells that were treated with 20 mM CCl4 (or 0.02% DMSO carrier) for 24 h followed by 8 or 16 μg/ml HepG2 cell-derived EVs for the following 24 h. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.005.

In vivo administration of fluorescently labeled EVNorm in mice results in their localization to various hepatic target cells including HSC and hepatocytes (Chen et al., 2018a). Since we have shown that EVNorm reverses ethanol/TNFα-mediated suppression of cell proliferation in hepatocytes (Chen et al., 2018a), we evaluated viability and proliferation of HepG2 cells that had been exposed in vitro to CCl4 (or DMSO carrier) in the presence or absence of HepG2 cell-derived EVs. The reduced viability caused by CCl4 was significantly and dose-dependently reversed by HepG2 cell-derived EVs (Figure 5E). Whereas DMSO caused a reduction in HepG2 cell proliferation, this was exacerbated even further by CCl4 but the deleterious effects of both agents was dose-dependently reversed by HepG2 cell-derived EVs (Figure 5F). HepG2 cell-derived EVs also promoted a slight but significant increase in the viability of HepG2 cells maintained under control non-injurious conditions (Figure 5E). Similar data were observed for CCl4-treated AML12 cells exposed to EVNorm or HepG2 cell-derived EVs (data not shown).

Since HepG2 cells are an immortalized cell line, we next use PHHs as an alternative source for human hepatocyte EVs. PHH-derived EVs purified from serum-free medium were 99 ± 5.9 nm in diameter (approx. range 50–150 nm) as assessed by NTA (Figure 6A) and when analyzed by Western blot they were positive for common EV proteins but not calnexin which was present exclusively in PHH lysates (Figure 6B and Supplementary Figure 4). PHH-derived EVs were then labeled with PKH26 and incubated in vitro with PHHs or human LX-2 HSC in the presence or absence of CCl4. The number of PHHs was significantly greater in the presence of EVs under both basal conditions and after exposure of the cells to CCl4, the latter of which otherwise caused a ∼60% decrease in overall cell number during the 48-h experiment (Figure 6C). This outcome generally resembled the effect of EVNorm or HepG2 cell-derived EVs on AML12 cells or HepG2 cells (see above). The number of LX2 cells was not significantly altered by PHH-derived EVs under normal conditions but exposure of the cells to CCl4 resulted in a 20% decrease in cell number that was reversed in the presence of PHH-derived EVs (Figure 6D). As compared to control cultures of each cell type, there was enhanced EV binding to the cells after their exposure to CCl4 (Figures 6B,C), consistent with our previously reported increased binding of EVNorm to (i) ethanol-treated mouse hepatocytes in vitro, (ii) mouse hepatocytes recovered from fibrotic livers in vivo, or (iii) activated mouse HSC in vitro or in vivo (Chen et al., 2018a). PHH EVs partially or completely reversed CCl4-mediated alterations of CCN2, albumin or CYP7A1 expression in PHHs (Figure 6E) or of CCN2 or Col1a1 expression in LX-2 HSC (Figure 6F).

FIGURE 6.

Characterization and actions of EVs from PHH. EVs present in 24-h serum-free conditioned medium from PHHs were analyzed by (A) NTA or (B) Western blotting (the latter compared to PHH lysate; 10 μg EV or cellular protein per lane; uncropped data are shown in Supplementary Figure 4). Purified PHH-derived EVs were labeled with PKH26 and incubated for 24 h with (C) PHHs or (D) LX-2 HSC that had been exposed to 20 mM CCl4 for the preceding 24 h. Cells were stained with DAPI and viewed using fluorescence microscopy with data quantified for total cell number (left) or the frequency of PKH26-positive cells (right). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗∗P < 0.005. (E) PHHs or (F) LX-2 HSC were serum-starved for 12 h and then treated for 36 h with 20 mM CCl4 in the presence or absence of PHH-derived EVs (4 × 108 particles/ml) after which mRNA was assessed by qRT-PCR. ∗P < 0.05 vs. Ctrl; #P < 0.05 vs. CCl4.

Thus, EVs from human hepatocytes restored alterations in gene expression associated with injury in human hepatocytes or fibrogenesis in human or mouse HSC.

Discussion

The emerging field of EV biology has provided a new impetus for research of liver physiology and pathology, and virtually every hepatic cell type has now been identified as an EV producer and/or recipient cell (Lemoinne et al., 2014; Hirsova et al., 2016b; Cai et al., 2017; Maji et al., 2017; Szabo and Momen-Heravi, 2017). Unfortunately, as in other organ systems, there is a dearth of information regarding the true nature of EV signaling in the liver and between the various hepatic cell types because few models have yet to be developed that would allow their various EV populations to be either tracked from the time of their initial biogenesis in donor cells to their uptake and action in recipient cells or functionally compromised in vivo. Despite these limitations, accumulating evidence supports a role for liver-derived EVs in regulating hepatic function. For example mouse hepatocyte exosomes promote hepatocyte proliferation in vitro or after acute liver injury in vivo caused by ischemia reperfusion (Nojima et al., 2016). Our previous (Chen et al., 2018a) and current findings for mouse or human hepatocyte EVs show that, in vitro, they are anti-fibrogenic for activated HSC, and reverse ethanol- or CCl4-suppressed proliferation or viability or alterations in gene expression in hepatocytes. Indeed, the data presented here show that hepatocyte EVs possess therapeutic properties that are quite consistent across three hepatocyte producer cell types (AML12, HepG2, PHH) from two species of origin of EV producer cell (human, mouse) and across two target cell types (HSC, hepatocytes) from two species of origin (human, mouse).

By performing a focused analysis of fibrosis-related molecular targets and cellular processes in toxic injury in vivo or in vitro, we showed that in the liver, mouse hepatocyte EVs are anti-fibrogenic, anti-fibrotic, suppress monocyte/macrophage infiltration, dampen expression of inflammatory mediators, and restore toxin-induced changes in hepatocyte function and HSC activation. The latter two properties were also elaborated by human hepatocyte EVs in in vitro models suggesting that the therapeutic properties are evolutionary conserved. It is currently unclear why, in CCl4-treated mouse liver, EVNorm appears to target the αSMA protein more efficaciously than its corresponding mRNA but this may point to the targeting of αSMA post-transcriptional regulation by the EVNorm molecular payload. With respect to mRNA targets, RNA-seq analysis enabled us to undertake a comprehensive analysis of liver genes that were targeted by EVNorm in mice with CCl4-induced hepatic fibrosis. In addition to identifying a further slate of pro-fibrogenic targets, we found that EVNorm action was also associated with the altered expression of genes associated with ECM, detoxification, cell cycle/cell division, signal transduction, adaptive immunity, and membrane trafficking. Thus, the transcriptomic landscape of genes targeted by EVNorm was diverse, notwithstanding the fact many were associated with p53, consistent with its level of activation being a target of EVNorm.

Most previous studies on hepatocyte EVs have addressed their pathogenic properties when produced by cells that are stressed, injured, infected, or tumorigenic. For example, (i) exosomes are used by HCV or HEV as a mean of egress and transmission from and between hepatocytes (Tamai et al., 2012; Ramakrishnaiah et al., 2013; Nagashima et al., 2014), (ii) HCV-infected hepatocytes produce EVs that promote T follicular regulatory cell expansion (Cobb et al., 2017) and which contain miR19a which drives HSC activation via the STAT3-TGF-β pathway (Devhare et al., 2017), (iii) EVs from HBV-infected or alcohol-treated hepatocytes stimulate macrophage activation and immune function (Momen-Heravi et al., 2015; Kouwaki et al., 2016; Verma et al., 2016), (iv) exosomes derived from CCl4-treated hepatocytes increase toll-like receptor three expression in HSC, leading to increased IL-17A production by γδ T cells and an exacerbation of liver fibrosis (Seo et al., 2016), (v) palmitate- or lysophosphatidylcholine-treated hepatocytes produce ceramide-enriched EVs (Kakazu et al., 2016), containing C-X-C motif ligand 10 (Ibrahim et al., 2016), are released from the cell by mixed lineage kinase 3 (Ibrahim et al., 2016) and have a broad effect on target cells including stimulation of chemotaxis and production of inflammatory mediators in macrophages (Hirsova et al., 2016a; Kakazu et al., 2016), induction of migration and tube formation in endothelial cells in vitro and angiogenesis in mice (Povero et al., 2013), and activation of HSC via delivery of miR-192 or miR-128-3p (Povero et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2017), and (vi) exosomes from hepatocellular carcinoma cells can either deliver receptor tyrosine kinases to monocytes which show improved survival due to activation of mitogen activated protein kinases (Song et al., 2016) or elicit heat shock protein-specific NK anti-tumor responses when the donor cells are treated with anti-cancer drugs (Lv et al., 2012). In contrast, our studies show that EVs from normal hepatocytes have distinct biological properties resulting in therapeutic outcomes for liver cell damage and fibrosis. Future studies will need to provide clarity on how fibrosis and more severe forms of liver pathology are regulated by the balance between different populations of EVs from the various intact and injured hepatic cell types. It will also be interesting to determine if endogenously released EVNorm, along with EVs from other hepatic cells, play a more nuanced role by intrinsically limiting hepatocellular damage and pathogenesis after injury. Along these lines, the ability of hepatocyte EVs to enhance hepatocyte function (e.g., HepG2 cell viability, PHH cell number) even under basal conditions may be attributable to the collection of EVs from cells under culture conditions that are not absolutely identical to those used for subsequent biological assays, thereby manifesting a modest therapeutic benefit.

We have recently shown that serum EVs are anti-fibrogenic and anti-fibrotic in the same in vitro or in vivo models (Chen et al., 2018b). Although high fidelity animal models to monitor hepatocyte EV release and distribution are currently lacking, emerging evidence suggests that EVs harboring hepatocyte markers are detectable in the circulation, at least in certain liver diseases (Povero et al., 2014; Rega-Kaun et al., 2019). Hence in the future it will be of interest to determine if EVNorm are present in the circulation and thereby contribute to the pool of therapeutic EVs in serum. We previously identified miR-34c, -151, -483, or -532 as potential therapeutic cargo molecules in serum EVs (Chen et al., 2018b) and, while detailed studies are needed in the future, our preliminary studies have implicated some of the same miRs in EVNorm (Chen et al., 2016a). That said, it is likely that additional cargo molecules in EVNorm contribute to the therapeutic actions of EVNorm on parenchymal and non-parenchymal liver cells, as well as on the various infiltrating cell types. Indeed, as recently emphasized (Gho and Lee, 2017), a reductionist approach to addressing this question may have a somewhat limited outcome because EVs are highly heterogeneous at both the single vesicle and systems level (cargo, EV sub-types etc.). Furthermore, we documented a broad response in cellular functions and gene expression in response to EVNorm, and it is likely that multiple interacting molecules in the EV molecular payload (miRs, mRNAs, proteins) are collectively involved, both directly and indirectly. For these many reasons, a holistic approach (Gho and Lee, 2017) will need to be undertaken to comprehensively determine the molecular basis for EVNorm actions. Proteomic analysis of exosomes derived from rat or mouse hepatocytes previously revealed the presence of approximately 250 proteins with enrichment for functional activities including oxidoreductase, GTPase, iron-binding, lipid binding, intracellular transport, protein folding, stress response, cellular homeostasis and lipid metabolism (Conde-Vancells et al., 2008). We speculate that the combinatorial delivery by EVNorm of a similar repertoire of proteins, together with EV-derived miRs and mRNAs, underlies the net therapeutic properties of EVNorm.

Finally, many studies have started to emerge showing that toxic liver injury, inflammation, hepatic fibrosis and HSC activation are ameliorated by EVs produced by various stem cells (SC) including umbilical cord mesenchymal SC (Li et al., 2013; Jiang et al., 2018), adipose-derived mesenchymal SC (Qu et al., 2017), embryonic SC-derived mesenchymal stromal cells (Mardpour et al., 2018), amnion-derived mesenchymal SC (Ohara et al., 2018), pluripotent SC (Povero et al., 2019), bone marrow mesenchymal SC (Rong et al., 2019), and liver SC (Bruno et al., 2019). As this research area expands, it will be important to determine if common mechanisms in these EV populations account for their shared therapeutic effects in the liver and the extent to which there is mechanistic overlap with anti-fibrogenic EVs from differentiated cells such as either hepatocytes as reported here or quiescent HSC as reported previously (Chen et al., 2014, 2015, 2016b).

In summary, hepatocyte EVs have anti-fibrotic actions in vivo that are associated with attenuated HSC activation and fibrogenesis, hepatocyte recovery, reduced levels of hepatic monocytes and macrophages, and attenuated expression of inflammatory mediators, as well as regulation of genes associated with ECM, detoxification, cell cycle/cell division, signal transduction, adaptive immunity, and membrane trafficking. These novel findings show that hepatocyte EVs hold promise as an innovative therapy for acute or chronic liver injury.

Data Availability Statement

The RNA-seq datasets generated for this study can be found in the GEO accession GSE136152.

Ethics Statement

The animal study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Nationwide Children’s Hospital (Columbus, OH, United States).

Author Contributions

XL performed the study design, acquisition and analysis of the data, figure preparation, and drafting and editing the manuscript. RC and SK performed the experiment planning, data acquisition, and manuscript editing. DB was responsible for the study concept and design, interpretation of the data, drafting and revising the manuscript, funding, and study supervision.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Cindy McAllister (Biomorphology Core) for help with histology and electron microscopy, and David Dunaway and Victoria Valquerez (Flow Cytometry Core) for help with NTA. We also thank Amy Wetzel and Zhaohui Xu (Biomedical Genomics Core) for next generation sequencing and bioinformatics analysis.

Funding. This study was supported by NIH grants R01AA021276 and R21AA023626 (DB, Principal Investigator) and pilot funding to DB from NIH grant P50AA024333 in support of the Northern Ohio Alcohol Center (Laura Nagy, Principal Investigator, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH, United States).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcell.2019.00368/full#supplementary-material

References

- Alvarez Rojas C. A., Ansell B. R., Hall R. S., Gasser R. B., Young N. D., Jex A. R., et al. (2015). Transcriptional analysis identifies key genes involved in metabolism, fibrosis/tissue repair and the immune response against Fasciola hepatica in sheep liver. Parasit. Vectors 8:124. 10.1186/s13071-015-0715-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berres M. L., Koenen R. R., Rueland A., Zaldivar M. M., Heinrichs D., Sahin H., et al. (2010). Antagonism of the chemokine Ccl5 ameliorates experimental liver fibrosis in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 120 4129–4140. 10.1172/JCI41732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitkopf K., Lahme B., Tag C. G., Gressner A. M. (2001). Expression and matrix deposition of latent transforming growth factor beta binding proteins in normal and fibrotic rat liver and transdifferentiating hepatic stellate cells in culture. Hepatology 33 387–396. 10.1053/jhep.2001.21996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruno S., Pasquino C., Herrera Sanchez M. B., Tapparo M., Figliolini F., Grange C., et al. (2019). HLSC-derived extracellular vesicles attenuate liver fibrosis and inflammation in a murine model of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Mol. Ther. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai S., Cheng X., Pan X., Li J. (2017). Emerging role of exosomes in liver physiology and pathology. Hepatol. Res. 47 194–203. 10.1111/hepr.12794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carotti S., Perrone G., Amato M., Vespasiani Gentilucci U., Righi D., Francesconi M., et al. (2017). Reelin expression in human liver of patients with chronic hepatitis C infection. Eur. J. Histochem. 61:2745. 10.4081/ejh.2017.2745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charrier A., Chen R., Chen L., Kemper S., Hattori T., Takigawa M., et al. (2014a). Exosomes mediate intercellular transfer of pro-fibrogenic connective tissue growth factor (CCN2) between hepatic stellate cells, the principal fibrotic cells in the liver. Surgery 156 548–555. 10.1016/j.surg.2014.04.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charrier A., Chen R., Kemper S., Brigstock D. R. (2014b). Regulation of pancreatic inflammation by connective tissue growth factor (CTGF/CCN2). Immunology 141 564–576. 10.1111/imm.12215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charrier A. L., Brigstock D. R. (2010). Connective tissue growth factor production by activated pancreatic stellate cells in mouse alcoholic chronic pancreatitis. Lab. Invest. 90 1179–1188. 10.1038/labinvest.2010.82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Charrier A., Zhou Y., Chen R., Yu B., Agarwal K., et al. (2014). Epigenetic regulation of connective tissue growth factor by MicroRNA-214 delivery in exosomes from mouse or human hepatic stellate cells. Hepatology 59 1118–1129. 10.1002/hep.26768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Charrier A. L., Leask A., French S. W., Brigstock D. R. (2011). Ethanol-stimulated differentiated functions of human or mouse hepatic stellate cells are mediated by connective tissue growth factor. J. Hepatol. 55 399–406. 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.11.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Chen R., Kemper S., Brigstock D. R. (2016a). Hepatocyte exosomes attenuate hepatic stellate cell activation in vitro and are anti-fibrotic in vivo. Hepatology 64 1–136. 10.1002/hep.28796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Chen R., Velazquez V. M., Brigstock D. R. (2016b). Fibrogenic signaling is suppressed in hepatic stellate cells through targeting of connective tissue growth factor (CCN2) by cellular or exosomal MicroRNA-199a-5p. Am. J. Pathol. 186 2921–2933. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2016.07.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Chen R., Kemper S., Brigstock D. R. (2018a). Pathways of production and delivery of hepatocyte exosomes. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 12 343–357. 10.1007/s12079-017-0421-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Chen R., Kemper S., Cong M., You H., Brigstock D. R. (2018b). Therapeutic effects of serum extracellular vesicles in liver fibrosis. J. Extracell. Vesicles 7:1461505. 10.1080/20013078.2018.1461505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Chen R., Kemper S., Charrier A., Brigstock D. R. (2015). Suppression of fibrogenic signaling in hepatic stellate cells by Twist1-dependent microRNA-214 expression: role of exosomes in horizontal transfer of Twist1. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 309 G491–G499. 10.1152/ajpgi.00140.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb D. A., Golden-Mason L., Rosen H. R., Hahn Y. S. (2017). Hepatocyte-derived exosomes promote T follicular regulatory cell expansion during HCV infection. Hepatology 67 71–85. 10.1002/hep.29409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Naftaly M., Friedman S. L. (2011). Current status of novel antifibrotic therapies in patients with chronic liver disease. Therap. Adv. Gastroenterol. 4 391–417. 10.1177/1756283X11413002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conde-Vancells J., Rodriguez-Suarez E., Embade N., Gil D., Matthiesen R., Valle M., et al. (2008). Characterization and comprehensive proteome profiling of exosomes secreted by hepatocytes. J. Proteome Res. 7 5157–5166. 10.1021/pr8004887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constandinou C., Henderson N., Iredale J. P. (2005). Modeling liver fibrosis in rodents. Methods Mol. Med. 117 237–250. 10.1385/1-59259-940-0:237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devhare P. B., Sasaki R., Shrivastava S., Di Bisceglie A. M., Ray R., Ray R. B. (2017). Exosome-mediated intercellular communication between hepatitis C virus-infected hepatocytes and hepatic stellate cells. J. Virol. 91:e02225-16. 10.1128/JVI.02225-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobin A., Davis C. A., Schlesinger F., Drenkow J., Zaleski C., Jha S., et al. (2013). STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29 15–21. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgawish R. A. R., Rahman H. G. A., Abdelrazek H. M. A. (2015). Green tea extract attenuates CCl4-induced hepatic injury in male hamsters via inhibition of lipid peroxidation and p53-mediated apoptosis. Toxicol. Rep. 2 1149–1156. 10.1016/j.toxrep.2015.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghiassi-Nejad Z., Friedman S. L. (2008). Advances in antifibrotic therapy. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2 803–816. 10.1586/17474124.2.6.803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gho Y. S., Lee C. (2017). Emergent properties of extracellular vesicles: a holistic approach to decode the complexity of intercellular communication networks. Mol. Biosyst. 13 1291–1296. 10.1039/c7mb00146k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A., Sil P. C. (2006). A 43-kDa protein from the leaves of the herb Cajanus indicus L. modulates chloroform induced hepatotoxicity in vitro. Drug Chem. Toxicol. 29 397–413. 10.1080/01480540600837944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X. L., Liang B., Wang X. W., Fan F. G., Jin J., Lan R., et al. (2013). Glycyrrhizic acid attenuates CCl(4)-induced hepatocyte apoptosis in rats via a p53-mediated pathway. World J. Gastroenterol. 19 3781–3791. 10.3748/wjg.v19.i24.3781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrichs D., Berres M. L., Nellen A., Fischer P., Scholten D., Trautwein C., et al. (2013). The chemokine CCL3 promotes experimental liver fibrosis in mice. PLoS One 8:e66106. 10.1371/journal.pone.0066106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsova P., Ibrahim S. H., Krishnan A., Verma V. K., Bronk S. F., Werneburg N. W., et al. (2016a). Lipid-induced signaling causes release of inflammatory extracellular vesicles from hepatocytes. Gastroenterology 150 956–967. 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.12.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsova P., Ibrahim S. H., Verma V. K., Morton L. A., Shah V. H., LaRusso N. F., et al. (2016b). Extracellular vesicles in liver pathobiology: small particles with big impact. Hepatology 64 2219–2233. 10.1002/hep.28814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim S. H., Hirsova P., Tomita K., Bronk S. F., Werneburg N. W., Harrison S. A., et al. (2016). Mixed lineage kinase 3 mediates release of C-X-C motif ligand 10-bearing chemotactic extracellular vesicles from lipotoxic hepatocytes. Hepatology 63 731–744. 10.1002/hep.28252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W., Tan Y., Cai M., Zhao T., Mao F., Zhang X., et al. (2018). Human umbilical cord MSC-derived exosomes suppress the development of CCl4-induced liver injury through antioxidant effect. Stem Cells Int. 2018:6079642. 10.1155/2018/6079642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakazu E., Mauer A. S., Yin M., Malhi H. (2016). Hepatocytes release ceramide-enriched pro-inflammatory extracellular vesicles in an IRE1alpha-dependent manner. J. Lipid Res. 57 233–245. 10.1194/jlr.M063412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouwaki T., Fukushima Y., Daito T., Sanada T., Yamamoto N., Mifsud E. J., et al. (2016). Extracellular vesicles including exosomes regulate innate immune responses to hepatitis B virus infection. Front. Immunol. 7:335. 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowal J., Arras G., Colombo M., Jouve M., Morath J. P., Primdal-Bengtson B., et al. (2016). Proteomic comparison defines novel markers to characterize heterogeneous populations of extracellular vesicle subtypes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113 E968–E977. 10.1073/pnas.1521230113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan A., Li X., Kao W. Y., Viker K., Butters K., Masuoka H., et al. (2012). Lumican, an extracellular matrix proteoglycan, is a novel requisite for hepatic fibrosis. Lab. Invest. 92 1712–1725. 10.1038/labinvest.2012.121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y. S., Kim S. Y., Ko E., Lee J. H., Yi H. S., Yoo Y. J., et al. (2017). Exosomes derived from palmitic acid-treated hepatocytes induce fibrotic activation of hepatic stellate cells. Sci. Rep. 7:3710. 10.1038/s41598-017-03389-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemoinne S., Thabut D., Housset C., Moreau R., Valla D., Boulanger C. M., et al. (2014). The emerging roles of microvesicles in liver diseases. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 11 350–361. 10.1038/nrgastro.2014.7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T., Yan Y., Wang B., Qian H., Zhang X., Shen L., et al. (2013). Exosomes derived from human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells alleviate liver fibrosis. Stem Cells Dev. 22 845–854. 10.1089/scd.2012.0395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao Y., Smyth G. K., Shi W. (2014). featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 30 923–930. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love M. I., Huber W., Anders S. (2014). Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15:550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv L. H., Wan Y. L., Lin Y., Zhang W., Yang M., Li G. L., et al. (2012). Anticancer drugs cause release of exosomes with heat shock proteins from human hepatocellular carcinoma cells that elicit effective natural killer cell antitumor responses in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 287 15874–15885. 10.1074/jbc.M112.340588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maji S., Matsuda A., Yan I. K., Parasramka M., Patel T. (2017). Extracellular vesicles in liver diseases. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 312 G194–G200. 10.1152/ajpgi.00216.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mardpour S., Hassani S. N., Mardpour S., Sayahpour F., Vosough M., Ai J., et al. (2018). Extracellular vesicles derived from human embryonic stem cell-MSCs ameliorate cirrhosis in thioacetamide-induced chronic liver injury. J. Cell. Physiol. 233 9330–9344. 10.1002/jcp.26413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momen-Heravi F., Bala S., Kodys K., Szabo G. (2015). Exosomes derived from alcohol-treated hepatocytes horizontally transfer liver specific miRNA-122 and sensitize monocytes to LPS. Sci. Rep. 5:9991. 10.1038/srep09991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagashima S., Jirintai S., Takahashi M., Kobayashi T., Tanggis, Nishizawa T., et al. (2014). Hepatitis E virus egress depends on the exosomal pathway, with secretory exosomes derived from multivesicular bodies. J. Gen. Virol. 95(Pt 10), 2166–2175. 10.1099/vir.0.066910-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen-Lefebvre A. T., Ajith A., Portik-Dobos V., Horuzsko D. D., Arbab A. S., Dzutsev A., et al. (2018). The innate immune receptor TREM-1 promotes liver injury and fibrosis. J. Clin. Invest. 128 4870–4883. 10.1172/JCI98156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nojima H., Freeman C. M., Schuster R. M., Japtok L., Kleuser B., Edwards M. J., et al. (2016). Hepatocyte exosomes mediate liver repair and regeneration via sphingosine-1-phosphate. J. Hepatol. 64 60–68. 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.07.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohara M., Ohnishi S., Hosono H., Yamamoto K., Yuyama K., Nakamura H., et al. (2018). Extracellular vesicles from amnion-derived mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate hepatic inflammation and fibrosis in rats. Stem Cells Int. 2018:3212643. 10.1155/2018/3212643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perbal B., Tweedie S., Bruford E. (2018). The official unified nomenclature adopted by the HGNC calls for the use of the acronyms, CCN1-6, and discontinuation in the use of CYR61, CTGF, NOV and WISP 1-3 respectively. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 12 625–629. 10.1007/s12079-018-0491-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Povero D., Eguchi A., Li H., Johnson C. D., Papouchado B. G., Wree A., et al. (2014). Circulating extracellular vesicles with specific proteome and liver microRNAs are potential biomarkers for liver injury in experimental fatty liver disease. PLoS One 9:e113651. 10.1371/journal.pone.0113651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Povero D., Eguchi A., Niesman I. R., Andronikou N., de Mollerat du Jeu X., Mulya A., et al. (2013). Lipid-induced toxicity stimulates hepatocytes to release angiogenic microparticles that require Vanin-1 for uptake by endothelial cells. Sci. Signal. 6:ra88. 10.1126/scisignal.2004512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Povero D., Panera N., Eguchi A., Johnson C. D., Papouchado B. G., de Araujo Horcel L., et al. (2015). Lipid-induced hepatocyte-derived extracellular vesicles regulate hepatic stellate cell via microRNAs targeting PPAR-gamma. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 1:646–663.e4. 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2015.07.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Povero D., Pinatel E. M., Leszczynska A., Goyal N. P., Nishio T., Kim J., et al. (2019). Human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles reduce hepatic stellate cell activation and liver fibrosis. JCI Insight 5:125652. 10.1172/jci.insight.125652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preaux A. M., Mallat A., Nhieu J. T., D’Ortho M. P., Hembry R. M., Mavier P. (1999). Matrix metalloproteinase-2 activation in human hepatic fibrosis regulation by cell-matrix interactions. Hepatology 30 944–950. 10.1002/hep.510300432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Y., Zhang Q., Cai X., Li F., Ma Z., Xu M., et al. (2017). Exosomes derived from miR-181-5p-modified adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells prevent liver fibrosis via autophagy activation. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 21 2491–2502. 10.1111/jcmm.13170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishnaiah V., Thumann C., Fofana I., Habersetzer F., Pan Q., de Ruiter P. E., et al. (2013). Exosome-mediated transmission of hepatitis C virus between human hepatoma Huh7.5 cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110 13109–13113. 10.1073/pnas.1221899110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rega-Kaun G., Ritzel D., Kaun C., Ebenbauer B., Thaler B., Prager M., et al. (2019). Changes of circulating extracellular vesicles from the liver after roux-en-Y bariatric surgery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20:2153. 10.3390/ijms20092153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rong X., Liu J., Yao X., Jiang T., Wang Y., Xie F. (2019). Human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells-derived exosomes alleviate liver fibrosis through the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 10:98. 10.1186/s13287-019-1204-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo W., Eun H. S., Kim S. Y., Yi H. S., Lee Y. S., Park S. H., et al. (2016). Exosome-mediated activation of toll-like receptor 3 in stellate cells stimulates interleukin-17 production by gammadelta T cells in liver fibrosis. Hepatology 64 616–631. 10.1002/hep.28644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song X., Ding Y., Liu G., Yang X., Zhao R., Zhang Y., et al. (2016). Cancer cell-derived exosomes induce mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent monocyte survival by transport of functional receptor tyrosine kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 291 8453–8464. 10.1074/jbc.M116.716316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo G., Momen-Heravi F. (2017). Extracellular vesicles in liver disease and potential as biomarkers and therapeutic targets. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 14 455–466. 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamai K., Shiina M., Tanaka N., Nakano T., Yamamoto A., Kondo Y., et al. (2012). Regulation of hepatitis C virus secretion by the Hrs-dependent exosomal pathway. Virology 422 377–385. 10.1016/j.virol.2011.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiele N. D., Wirth J. W., Steins D., Koop A. C., Ittrich H., Lohse A. W., et al. (2017). TIMP-1 is upregulated, but not essential in hepatic fibrogenesis and carcinogenesis in mice. Sci. Rep. 7:714. 10.1038/s41598-017-00671-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma V. K., Li H., Wang R., Hirsova P., Mushref M., Liu Y., et al. (2016). Alcohol stimulates macrophage activation through caspase-dependent hepatocyte derived release of CD40L containing extracellular vesicles. J. Hepatol. 64 651–660. 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.11.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R., Ding Q., Yaqoob U., de Assuncao T. M., Verma V. K., Hirsova P., et al. (2015). Exosome adherence and internalization by hepatic stellate cells triggers sphingosine 1-phosphate-dependent migration. J. Biol. Chem. 290 30684–30696. 10.1074/jbc.M115.671735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan Z., Chen Y., Duan Y., Li L., Mew K., Hu P., et al. (2019). Identification of key genes, pathways and potential therapeutic agents for liver fibrosis using an integrated bioinformatics analysis. PeerJ 7:e6645. 10.7717/peerj.6645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The RNA-seq datasets generated for this study can be found in the GEO accession GSE136152.