Introduction

On October 17, 2018, the Cannabis Act came into Canadian law, making access and use of marijuana legal for both recreational and medicinal purposes.1 The transition from a largely illicit substance to a publicly available product presents new responsibilities for pharmacists. As the most accessible health care provider, community pharmacists are uniquely positioned to advise patients on the safety and effectiveness of cannabis use. From a health care delivery systems perspective, pharmacists must continue to participate in debate regarding the appropriate clinical oversight of medical cannabis dispensing.2-4 Pharmacists also need to contribute to the development of policies and procedures for cannabis prescribing and dispensing or product identification for patients’ own use in hospitals and other inpatient settings.5 Fortunately, a number of provincial regulatory bodies and professional associations have taken steps to equip pharmacist members with resources related to known evidence and emerging literature about marijuana’s potential benefits and risks, as well as updates on local and national legislation. The Ontario College of Pharmacists has devised a particularly comprehensive Cannabis Strategy for Pharmacy organized according to relevant areas of practice for pharmacist development and maintenance of competencies.6 The Canadian Pharmacists Association has been similarly proactive in the development of several important information resources for practitioners, including strategies for patient engagement.7 Yet in addition to the organized support to meet skill and knowledge needs for pharmacists in practice, consideration of the curriculum for current and future pharmacy students in training is necessary.

Efforts to harness the pharmacologic properties of cannabinoids to effectively manage disorders such as glaucoma, dementia, mental health and neurological conditions are inconsistent, but limited evidence is associated with the treatment of chronic pain, spasticity and nausea and vomiting.8,9 Although approved for medical indications in Canada and certain American states for some time, anecdotal and research findings indicate pharmacist knowledge of cannabis is generally poor. Hospital and community pharmacists in Minnesota and New Jersey (states where medical marijuana became legal for specific indications in 2014 and 2010, respectively) reported lack of training and confidence in their knowledge of medical cannabis pharmacotherapy.10,11 In a Canadian study of nearly 800 hospital pharmacists, two-thirds (64.5%) disagreed with the statement, “I consider myself knowledgeable about marijuana for medical purposes,” and half were uncomfortable with the prospect of providing advice to patients or other health professionals.12 Further data about marijuana knowledge and attitudes arise from a handful of studies of American pharmacy students. A 2011 survey of students at the University of Kansas (in a state that first legalized marijuana for medical purposes in November 2018) demonstrated varied ability of respondents to correctly name appropriate indications for medical marijuana or adverse effects of its use.13 Few (<15%) recalled marijuana instruction during their pharmacy program, and most (90%) believed more should be incorporated. Marijuana knowledge of Iowa pharmacy students (a state where restricted access to medical marijuana—only as cannabidiol oil and for limited medical indications—was first legislated in 2014) was similarly low, with 80% of respondents supporting addition of content to existing curricula.14 The majority of students in all these studies felt they lacked the ability to comfortably answer patient questions regarding the safety, effectiveness or potential drug interactions of cannabis therapy.

Deficits in pharmacist knowledge and corresponding confidence to dialogue with patients or fellow health care providers regarding cannabis are concerning given our mandate to provide quality medication management and serve as front-line advocates for health.15 With widespread legalization, individuals using or wishing to use cannabis for medical purposes may now choose to access it more readily through recreational routes and will need reliable sources of information.16,17 Similarly, recreational users may be more forthright talking to pharmacists about the impact of cannabis on their medications and overall health. Canadian prescribers also identified information needs, like dosing, comparisons between cannabis and existing prescription cannabinoids and the development of patient treatment plans, that pharmacists can provide.18 Given cannabis’s ongoing rise in regulatory and public health discourse, pharmacist understanding of cannabis, like that of other substances, such as alcohol and tobacco, should begin in undergraduate training. To inform how cannabis-oriented topics might be best incorporated into pharmacy education, we must first determine the existing status within our programs.

Methods

We conducted a national survey of pharmacy programs to inventory curricular content in any way related to marijuana. Senior administrator key informants at each of the 10 faculties were identified and emailed a questionnaire. The items were informed by a literature search of relevant published work and included questions pertaining to the types of courses where content might be delivered, the focus of the topic coverage and devoted time. The instructional methods were characterized according to the standardized curriculum nomenclature of the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC).19 Respondents were also asked to offer their own views of perceived barriers to the incorporation of marijuana in their curriculum. Consenting participants gathered pertinent information as necessary from their faculty colleagues in order to submit a unique program response through a web-based platform. Questionnaire data were anonymized and the findings aggregated with continuous and categorical variables represented as means and proportions, respectively. The limited text data associated with open responses were subjectively grouped but not formally analyzed for themes. Ethics approval was obtained from the University of British Columbia Institutional Review Board.

Results

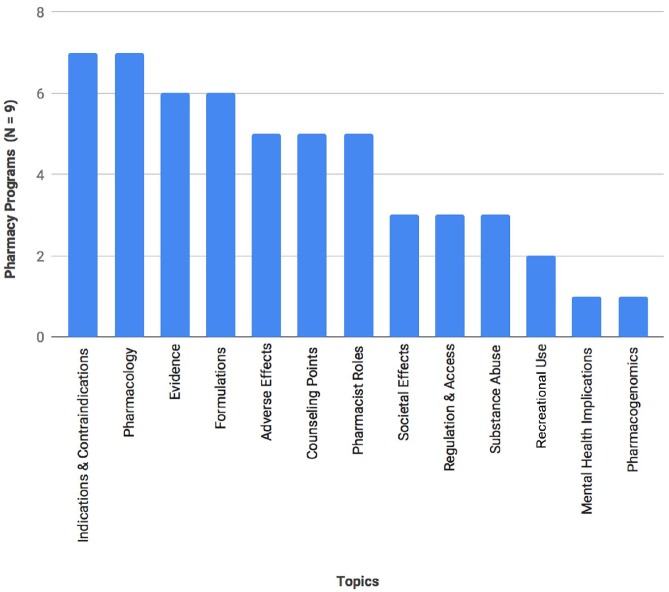

We received responses from all 10 faculties of pharmacy. Nine programs identified presence of content related to marijuana topics in their current curriculum. Topics included pharmacology and associated therapeutic and adverse effects, evidence for current indications, dosage formulations, patient counselling, societal implications and regulation and access (Figure 1). Marijuana content typically appeared in 1 course as a portion of a broader lecture (e.g., as an alternative when discussing chemotherapy-associated nausea). On average, approximately 4 hours were devoted to marijuana-related material among the 9 faculties, ranging from 0.5 hours to 12.5 hours in any given program across 1 to 7 courses. Most of this instructional time was lecture based (52%), followed by seminars (27%), tutorials (11%) and case-based learning (9%) in required courses. Elective courses broadly related to pain or addiction where marijuana was integrated were identified by 3 schools. One program described marijuana instruction for students in the context of a clinical experience providing patient care in a chronic pain practice rotation. Marijuana topics were usually located in second and third years (26% and 42%, respectively).

Figure 1.

Cannabis content in Canadian undergraduate pharmacy programs

Many key informants indicated the addition or increase of marijuana content in their pharmacy curriculum in the current academic year (2018-2019) or plans to do so in the near future. Only 1 program (2 hours of content over 1 course) was reportedly satisfied with existing content. The program without marijuana content was intending to incorporate topics for third-year students in the next academic year. Reported barriers to the expansion of marijuana content in pharmacy programs included inadequate time available in the curriculum (60%), followed by perceived lack of strong therapeutic evidence (40%), absence of local content expert (20%) and uncertainty regarding evolving legislation and policy (20%).

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate the heterogeneous status of marijuana content currently taught in pharmacy programs across Canada. Coverage of cannabis-related topics ranges from none or short instruction within relevant required therapeutic courses to significant representation within entire elective courses devoted to drugs of abuse. One program formally addressed aspects of patients’ marijuana use in an elective practice-based learning opportunity. These results are not dissimilar from the recent major survey of American schools and colleges of pharmacy where 42 (62%) of the 68 responding programs characterized marijuana content—pharmacotherapy, regulation/legal, ethics and medicinal chemistry, in rank order of prevalence—mostly as part of lectures in required courses.20 When these key informants were asked to rate which marijuana topics were important to incorporate in their curriculum, no priority content could be distinguished. In Canada, however, program determination of marijuana content necessary for student knowledge and skills may be guided in part by the strategic priorities set forth by the Ontario College of Pharmacists.6 Subject matter and instructional modalities may thus be purposefully integrated according to broad competencies necessary to provide patient care, health information and advice; document, develop and track data; and prevent harm.

Current emphasis on the physical and therapeutic properties of product derived from cannabis is undoubtedly requisite foundation for understanding potential benefits and risks for medicinal or recreational use over short- and long-term periods. However, apparent gaps exist in practical training opportunities (simulated or otherwise) to apply this knowledge in patient encounters. Given that essentially all existing studies of students and pharmacists highlight uncertainty or discomfort with marijuana-related conversations, we contend that opportunities for students to practise eliciting complete medication histories (which should now routinely include questions about marijuana use) and discussing evidence and communicating advice with patients and care providers are necessary (Table 1). Our survey revealed that program content related to government regulations and business ramifications of medical marijuana dispensing was also largely overlooked. This is unsurprising, given the new and evolving landscape of statutes for cannabis control and access, but this subject matter is rapidly gaining salience, particularly for students training for and ultimately pursuing careers in community pharmacy.

Table 1.

Broadening nature and scope of marijuana curricular content and potential instructional approaches

| Curricular content | Instructional approaches |

|---|---|

|

Communication and collaboration

Patient history taking Patient education/counseling Provider consultation |

Simulated encounters (standardized patients, providers) in

laboratory or demonstration settings Preceptor role modeling and student observation during practice experiences |

|

Care provider and scholar

Understand benefits and risks of use and rationale for the medical indications Identification of new knowledge Interpretation and application of research |

Comprehensive pharmacologic and therapeutic lecture/tutorial

content Journal club and case-based practice to review and apply available evidence |

|

Leader/manager

Apply principles of effective management and supervision of medication use systems Confirm quality, safety and integrity of products |

Lecture/tutorial content Structured activities during practice experiences involving inventory, formulary and dispensing approaches |

|

Professional

Exploring ethical and legal responsibilities |

Small/large group discussions/debate to consider issues such as patient access, pharmacy inventory and dispensing, relationships with cannabis industry |

As pharmacists continue to assume expanded scopes of practice, educators face difficult decisions determining what topics should find a place in their programs. New or augmented formal instruction devoted to cannabis, for example, competes with time assigned to interprofessional education activities, advanced evidence-appraisal skill development, physical assessment and injections training in entry-to-practice Doctor of Pharmacy curricula. Time allotted to campus-based instruction in our national programs has been additionally contracted to allow for increased experiential learning requirements.21 Lack of content expertise was also considered by some respondents to be a barrier to marijuana instruction in the curriculum. Instead, programs may consider the shift of certain student marijuana knowledge and skills’ acquisition to the authentic care settings of the practice-based curriculum under supervision of supportive practice educators developing their own knowledge and approaches to patient encounters.7 While there are inevitably nuances to how marijuana can be best incorporated into undergraduate education, we can be sure there are negative implications of a present and future pharmacist workforce inadequately prepared to provide accurate cannabis-related information or participate in the national dialogue surrounding safe and effective cannabis use.22

While all national pharmacy programs are represented in our survey, our results may be limited by reliance upon information provided by the local key informant. Although carefully selected, it is possible these individuals were unable to access all relevant information. We did not pursue our own independent review of each faculty’s curriculum study plan and so cannabis content may be underrepresented in our aggregate findings. Similarly, the reported barriers may be those perceived by the principal respondent. Unlike other studies, we did not seek to address educator or student attitudes towards the inclusion of marijuana into the health professional curriculum or determine how specific content would be prioritized. Ultimately, we recommend future inquiry into the learning outcomes and practical utility of any cannabis-oriented instruction for Canadian students and pharmacists alike to ensure pharmacy professionals are meeting patient and public expectations of care.

Conclusion

Our survey of cannabis content in Canadian undergraduate pharmacy education found disparity across current program curricula. Despite challenges associated with an unfolding regulatory framework and perceived lack of instructor expertise, we argue for greater integration of communication and commercial topics to complement existing emphasis on cannabis pharmacologic properties and effects.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note:In this article, we have used the terms marijuana and cannabis interchangeably, but we acknowledge that marijuana is just one of the different forms derived from the plant, Cannabis sativa.

Roles:KW conceived and supervised the project; all authors contributed to the questionnaire development; GT, JS and KL collected the data and synthesized the results and wrote the first manuscript draft; KW finalized the manuscript with all author approvals.

Financial Acknowledgments:This project was unfunded.

Conflict of Interest Statement:The authors have no conflict of interest to report.

ORCID iD:Kerry Wilbur  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5936-4429

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5936-4429

References

- 1. Canada Government, Ottawa. The Standing Committee on Health—Bill C-45, Cannabis Act. Available: www.parl.ca/DocumentViewer/en/42-1/bill/C-45/royal-assent (accessed Nov. 30, 2018).

- 2. KPMG. Improving medical marijuana management in Canada. 2016. Available: https://www.pharmacists.ca/cpha-ca/assets/File/cpha-on-the-issues/March2016_Improving_Medical_Marijuana_Management_in_Canada_vf.pdf Canadian Pharmacists Association; (accessed Oct. 31, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 3. Grootendorst P, Ranjithan R. Pharmacists should counsel users of medical cannabis, but should they be dispensing it? Can Pharm J (Ott) 2019;152(1):10-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dattani S, Mohr H. Pharmacists’ role in cannabis dispensing and counselling. Can Pharm J (Ott) 2019;152(1):14-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Borgelt LM, Franson KL. Considerations for hospital policies regarding medical cannabis use. Hosp Pharm 2017;52:89-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ontario College of Pharmacists. A cannabis strategy for pharmacy: enhancing knowledge, protecting patients. 2018. Available: http://www.ocpinfo.com/library/practice-related/download/cannabis-strategy-for-pharmacy.pdf (accessed Jul. 2, 2018).

- 7. Canadian Pharmacists Association. Cannabis for medical purposes: how to start the conversation. 2018. Available: https://www.pharmacists.ca/cpha-ca/assets/File/cpha-on-the-issues/CannabisTool_StartConversation.pdf (accessed Jul. 2, 2018).

- 8. Allan GM, Ramji J, Perry D, et al. Simplified guideline for prescribing medical cannabinoids in primary care. Can Fam Physician 2018;64:111-20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The health effects of cannabis and cannabinoids: The current state of evidence and recommendations for research. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2017. Available: 10.17226/24625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hwang J, Arneson T, Peter WS. Minnesota pharmacists and medical cannabis: a survey of knowledge, concerns and interest prior to program launch. Pharm Ther 2016;41:716. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Abazia DT, Bridgeman PJ, Bridgeman MB, Sturgill MG. Medicinal cannabis in pharmacy education: time for a curricular change or just reefer madness. Paper presented at the 118th Annual Meeting of the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy; July 15-19, 2017; Nashville, Tennessee. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mitchell F, Gould O, LeBlanc M, Manuel L. Opinions of hospital pharmacists in Canada regarding marijuana for medical purposes. Can J Hosp Pharm 2016;69:122-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Moeller KE, Woods B. Pharmacy students’ knowledge and attitudes regarding medical marijuana. Am J Pharm Educ 2015;79:85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Caligiuri FJ, Ulrich EE, Welter KJ. Pharmacy student knowledge, confidence and attitudes towards medical cannabis and curricular coverage. Am J Pharm Educ 2018;82(5):6296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Blueprint for Pharmacy Steering Committee. Blueprint for pharmacy: our way forward. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Pharmacists Association; 2013. Available: https://www.pharmacists.ca/cpha-ca/assets/File/pharmacy-in-canada/blueprint/Blueprint%20Priorities%20-%20Our%20way%20forward%202013%20-%20June%202013.pdf (accessed Dec. 2, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 16. Capler R, Walsh Z, Crosby K, et al. Are dispensaries indispensable? Patient experiences of access to cannabis from medical cannabis dispensaries in Canada. Int J Drug Policy 2017;47:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Belle-Isle L, Walsh Z, Callaway R, et al. Barriers to access for Canadians who use cannabis for therapeutic purposes. Int J Drug Policy 2014;25: 691-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ziemianski D, Capler R, Tekanoff R, Lacasse A, Luconi F, Ware MA. Cannabis in medicine: a national educational needs assessment among Canadian physicians. BMC Med Educ 2015;15:52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. MedBiquitous Curriculum Inventory Working Group Standardized Vocabulary Subcommittee. Curriculum inventory standardized instructional and assessment methods and resource types. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2016. Available: https://medbiq.org/curriculum/vocabularies.pdf (accessed July 2, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 20. Smithburger PL, Zemaitis MA, Meyer SM. Evaluation of medical marijuana topics in the PharmD curriculum: a national survey of schools and colleges of pharmacy. Curr Pharm Teach Learn 2019;11(1):1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Association of Faculties of Pharmacy in Canada (AFPC). Educational outcomes for first professional degree programs in pharmacy in Canada. 2017. Available: https://www.afpc.info/system/files/public/AFPC-Educational%20Outcomes%202017_final%20Jun2017.pdf (accessed Jul. 2, 2018).

- 22. Abazia DT, Bridgeman MB. Reefer madness or real medicine? A plea for incorporating medicinal cannabis in pharmacy curricula. Curr Pharm Teach Learn 2018;10(9):1165-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]