Abstract

MET exon 14 (METex14) skipping mutations are an emerging potentially targetable oncogenic driver mutation in non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). The imaging features and patterns of metastasis of NSCLC with primary METex14 skipping mutations (METex14-mutated NSCLC) are not well described. Our goal was to determine the clinicopathologic and imaging features that may suggest the presence of METex14 skipping mutations in NSCLC. This IRB-approved retrospective study included NSCLC patients with primary METex14 skipping mutations and pre-treatment imaging data between January 2013 and December 2018. The clinicopathologic characteristics were extracted from electronic medical records. The imaging features of the primary tumor and metastases were analyzed by two thoracic radiologists. In total, 84 patients with METex14-mutated NSCLC (mean age = 71.4 ± 10 years; F = 52, 61.9%, M = 32, 38.1%; smokers = 47, 56.0%, nonsmokers = 37, 44.0%) were included in the study. Most tumors were adenocarcinoma (72; 85.7%) and presented as masses (53/84; 63.1%) that were peripheral in location (62/84; 73.8%). More than one in five cancers were multifocal (19/84; 22.6%). Most patients with metastatic disease had only extrathoracic metastases (23/34; 67.6%). Fewer patients had both extrathoracic and intrathoracic metastases (10/34; 29.4%), and one patient had only intrathoracic metastases (1/34, 2.9%). The most common metastatic sites were the bones (14/34; 41.2%), the brain (7/34; 20.6%), and the adrenal glands (7/34; 20.6%). Four of the 34 patients (11.8%) had metastases only at a single site. METex14-mutated NSCLC has distinct clinicopathologic and radiologic features.

Keywords: lung cancer, MET exon 14 skipping, mutation, radiology

1. Introduction

Targeted therapy using small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) has become the standard of treatment in non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) harboring specific driver alterations in the epidermal growth factor (EGFR), anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK), rearrangement of the receptor tyrosine kinase 1 (ROS1), and V-raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B (BRAF) genes [1,2], demonstrating improved survival and quality-of-life benefits [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. However, the driver alterations of a majority of lung adenocarcinomas are unknown [14,15,16,17], highlighting the importance of identifying new targetable mutations. Mesenchymal–epithelial transition (MET) gene exon 14 skipping has emerged as a promising oncogenic target in lung cancer.

The MET proto-oncogene is located on chromosome 7q21-q31 and encodes a receptor tyrosine kinase implicated in RAS/MAPK, Rac/Rho, and PI3K/Akt signaling pathways, mediating cellular growth, development, anti-apoptosis, and metastasis [18,19,20]. First described in the 1980s [21,22], MET amplification and overexpression have been found in a wide variety of malignancies, including colon, breast, liver, gastric cancers, and sarcomas [23,24]. Overexpression of MET has also been implicated in 25–70% of all NSCLC [14] and as an acquired resistance mechanism in EGFR-mutated NSCLC [25].

MET exon 14 (METex14) skipping is found in approximately 3–4% of NSCLC [14,26] and represents a unique subset of all MET mutations, whereby DNA mutations affect RNA splicing sites and result in the loss of the CBL-E3 ligase binding site and sustained activation of the MET receptor [27]. Importantly, METex14 skipping and other NSCLC driver alterations, including EGFR, ALK, and ROS1 mutations, are mutually exclusive [26,28]. Furthermore, METex14 skipping has also demonstrated responsiveness to targeted MET therapies, making it currently the most predictive biomarker of the sensitivity to MET TKIs [29,30,31]. Small-molecule TKIs, such as crizotinib and cabozantinib, have shown promise in the treatment of NSCLC harboring METex14 mutations, in various case reports [29,30,32]. In addition, multiple clinical trials currently underway, investigating novel MET TKIs such as tepotinib and capmatinib, have demonstrated promising preliminary results [33,34,35,36,37,38].

Several studies have investigated the imaging features that may predict the presence of EGFR, ALK, ROS1, and other potentially targetable mutations in NSCLC [39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48]. To our knowledge, however, no study has systematically assessed the radiologic features of NSCLC harboring primary METex14 skipping (METex14-mutated NSCLC). The goal of this study was to determine the clinicopathologic and radiologic features that may suggest the presence of METex14 skipping in NSCLC.

2. Results

2.1. Clinicopathologic Characteristics

The clinicopathologic characteristics for patients with METex14-mutated NSCLC are summarized in Table 1. Most patients were female (52/84; 61.9%), and more than half were either previous or current smokers (47/84; 56%). In our cohort, there was equal distribution of stage 1 (34/84; 40.5%) and stage 4 (34/84; 40.5%) disease. A vast majority of the tumors were adenocarcinoma (72/84; 85.7%), followed by squamous (6/84; 7.1%) and sarcomatoid (3/84; 3.6%) carcinomas.

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic characteristics of patients with METex14- NSCLC (n = 84).

| Clinical Characteristics | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| Mean, SD (in years) | 71.4 | 10 |

| Median, range (in years) | 72.5 | 43–89 |

| Sex | n | % |

| F (%) | 52 | 61.9 |

| M (%) | 32 | 38.1 |

| Smoking status | ||

| Never | 37 | 44.0 |

| Current/Previous | 47 | 56.0 |

| Stage | ||

| I | 34 | 40.5 |

| II | 9 | 10.7 |

| IIIA | 5 | 6.0 |

| IIIB | 2 | 2.4 |

| IV | 34 | 40.5 |

| Histology | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 72 | 85.7 |

| Squamous | 6 | 7.1 |

| Sarcomatoid carcinoma | 3 | 3.6 |

| Others | 3 | 3.6 |

2.2. Imaging Features of the Primary Tumor

The imaging features of the primary tumor in METex14-mutated NSCLC are summarized in Table 2. Most tumors presented as masses measuring 3 cm or more (53/84; 63.1%) and were predominantly located in the upper lobes (59/84; 70.2%) at the periphery (62/84; 73.8%). Approximately one-third of the tumors were either part-solid (21/84; 25.0%) or pure ground-glass (6/84; 7.1%), while the rest were solid (57/84; 67.9%). Approximately one in five of the patients had multifocal tumors (19/84; 22.6%).

Table 2.

Imaging features of the primary tumor in METex14-mutated NSCLC (n = 84).

| Tumor Imaging Features | ||

|---|---|---|

| Size | ||

| Mean, SD (in mm) | 40.8 | 21.4 |

| Median, range (in mm) | 34.5 | 10–109 |

| Size | n | % |

| Mass (>3 cm) | 53 | 63.1 |

| Nodule (≤3 cm) | 31 | 36.9 |

| Lobar location | ||

| RUL | 38 | 45.2 |

| RML | 4 | 4.8 |

| RLL | 10 | 11.9 |

| LUL | 17 | 20.2 |

| LLL | 15 | 17.9 |

| Lobar location | ||

| Upper/Middle | 59 | 70.2 |

| Lower | 25 | 29.8 |

| Axial location | ||

| Peripheral | 62 | 73.8 |

| Central | 22 | 26.2 |

| Density | ||

| Solid | 57 | 67.9 |

| Part-solid | 21 | 25.0 |

| Pure ground-glass | 6 | 7.1 |

| Margin | ||

| Smooth | 9 | 10.7 |

| Lobulated | 53 | 63.1 |

| Spiculated | 22 | 26.2 |

| Other Tumor features | ||

| Air bronchograms | 3 | 3.6 |

| Cavitation | 4 | 4.8 |

| Cystic component | 4 | 4.8 |

| Calcification | 0 | 0.0 |

| Multifocal | 19 | 22.6 |

RUL: right upper lobe; RML: right middle lobe; RLL: right lower lobe; LUL: left upper lobe; LLL: left lower lobe.

2.3. Metastatic Patterns

In patients with metastatic METex14-mutated NSCLC, there was a higher propensity for extrathoracic metastases (28/34; 82.4%) compared to intrathoracic metastases (13/34; 38.2%). Most patients only had extrathoracic metastases (23/34; 67.6%), while only one (2.9%) had only intrathoracic metastases, and the rest had both intrathoracic and extrathoracic metastases (10/34; 29.4%). The most common metastatic sites were the bones (14/34; 41.2%), the brain (7/34; 20.6%), and the adrenal glands (7/34; 20.6%). Four of the 34 patients (11.8%) with metastatic disease had a single site of metastasis. Patterns of lymphadenopathy and metastases are presented on Table 3.

Table 3.

Patterns of lymphadenopathy and metastases in patients with stage IV METex14-mutated NSCLC (n = 34)。

| Metastatic Site | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Nodal metastasis | ||

| Ipsilateral hilar | 29 | 85.3 |

| Ipsilateral mediastinal | 19 | 55.9 |

| Contralateral hilar/mediastinal | 12 | 35.3 |

| Supraclavicular | 7 | 20.6 |

| Intrathoracic metastasis | 13 | 38.2 |

| Lung | 5 | 14.7 |

| Lymphangitic carcinomatosis | 4 | 11.8 |

| Pleural | 10 | 29.4 |

| Pericardial | 2 | 5.9 |

| Extrathoracic Metastasis | 28 | 82.4 |

| Adrenal | 7 | 20.6 |

| Liver | 3 | 8.8 |

| Gastric | 2 | 5.9 |

| Splenic | 0 | 0.0 |

| Bone (Lytic) | 14 | 41.2 |

| Brain | 7 | 20.6 |

| Soft tissue | 1 | 2.9 |

| Distant lymph node | 4 | 11.8 |

| Metastatic Distribution | ||

| Intrathoracic only | 1 | 2.9 |

| Extrathoracic only | 23 | 67.6 |

| Intra- and extrathoracic | 10 | 29.4 |

| Number of sites | ||

| One | 4 | 11.8 |

| Two or more | 30 | 88.2 |

3. Discussion

We present the first systematic assessment of the imaging features and patterns of metastasis in NSCLC with METex14 skipping mutations. We found that METex14-mutated NSCLC tumors commonly present as peripheral masses and that a considerable proportion of patients had multifocal lung cancer at presentation. In addition, among patients with metastatic disease, extrathoracic metastases were common, with the most common sites being the bones, brain, and adrenal glands.

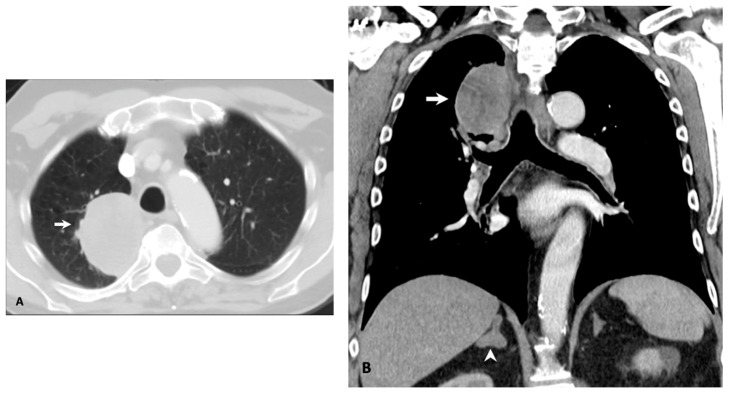

In our cohort, the average age of 71.4 years was higher than those previously reported for other targetable driver mutations [46,48,49]. This advanced age was reported in another study, which found a similar median age of 72.5 years [26]. In our cohort, the mutation did not appear to have a gender predilection and affected smokers and nonsmokers nearly evenly, in contrast to EGFR and ALK mutations that are more common in never and light smokers. From a pathological standpoint, a vast majority of the tumors were adenocarcinoma. Although still rare, there was a relatively increased frequency of sarcomatoid carcinoma (3.6%; Figure 1). While METex14 alterations have been described in up to 4% of lung cancers, they can be seen in approximately one-third of sarcomatoid carcinoma, which has generally been associated with a poorer prognosis [50].

Figure 1.

Oligometastatic NSCLC with sarcomatoid histology in a 70-year-old male former smoker. (A) Axial computed tomography (CT) image shows a large solid mass in the right upper lobe (A, arrow). (B) Coronal CT image shows the right upper lobe mass (B, arrow) and a right adrenal nodule (B, arrowhead). Biopsies and molecular testing of the right upper lobe mass and adrenal metastasis confirmed the presence of a METex14 skipping mutation.

With respect to imaging features, in our cohort, most of the primary METex14-mutated tumors were solid masses that were typically located in the periphery of the upper lobes. Air bronchograms, cavitation, and cystic changes were seen in less than 5% of the tumors. These features are not unique to METex14-mutated NSCLC and have been described in other mutated NSCLC, including those with ALK or ROS1 rearrangements [42,45,48,51]. This, however, is in contrast to EGFR-mutated NSCLC, reported to have increased incidence of subsolid and pure ground-glass lesions and increased frequency air bronchogram in the tumor [41]. For instance, our group has previously reported the presence of air bronchograms in up to 28% of EGFR-mutated NSCLC tumors [46], in contrast to their presence in less than 4% of METex14-mutated tumors in our current cohort.

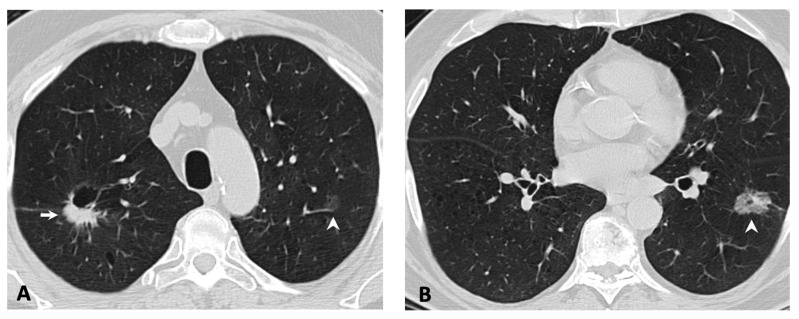

While there was no primary tumor imaging feature unique to METex14-mutated NSCLC in our cohort, there was an increased frequency of multifocality, with more than one in five patients having multifocal adenocarcinoma at the time of initial presentation (Figure 2). This incidence was higher than the prevalence of ALK and concomitant ALK and EGFR alterations in multifocal lung adenocarcinomas [52]. It is possible that the multifocality reflects multiple synchronous adenocarcinomas with distinct splice site mutations, a finding which has been previously described in the literature for METex14-mutated primary lung adenocarcinomas [53]. Multifocal adenocarcinomas at presentation may help indicate the possibility of METex14-mutated NSCLC and lead to more rapid triaging for molecular screening. These synchronous lung adenocarcinomas are increasingly being recognized and can be a diagnostic and management challenge [52]. Detection of these potentially targetable mutations in multifocal NSCLC may prove to be beneficial when these malignancies progress and metastasize.

Figure 2.

Multifocal lung adenocarcinomas in an 80-year-old female former smoker. (A) Axial CT through the upper lobes shows a part-cystic, part-solid nodule in the right upper lobe (A, arrow) and a faint ground-glass nodule in the left upper lobe (A, arrowhead). (B) Axial CT slice through the lower lobes shows an additional ground-glass nodule in the left lower lobe (B, arrowhead). Findings are consistent with multifocal adenocarcinomas. The patient went on to have a right upper lobectomy. Pathology and molecular testing revealed an adenocarcinoma with METex14 skipping mutation.

With respect to metastatic patterns, in our cohort, there were twice as many patients who had extrathoracic metastases compared to those with intrathoracic metastases. Most patients also had only extrathoracic metastases without intrathoracic metastases, while only one patient had only intrathoracic metastases without extrathoracic metastases. The most common sites were the bones, brain, and adrenal glands. This pattern of metastasis is in contrast to that of EGFR-mutated and ALK-rearranged NSCLC, which have been associated with an increased propensity for intrathoracic metastases. For example, in our group’s previous work, we reported a frequency of 69% for lung metastases in patients with EGFR-mutated NSCLC, which tended to be diffuse and miliary-like when present [46]. In comparison, the frequency of lung metastases in our cohort of patients with METex14-mutated NSCLC was less than 15%. Similarly, we reported frequencies of lymphangitic carcinomatosis of 37% in patients with ALK-rearranged NSCLC [45] and of 42% in those with ROS1-rearranged NSCLC [48], in comparison to less than 12% in our current cohort.

The high propensity for brain metastases is a feature that has also been reported for tumors with other potentially targetable mutations, including EGFR, ALK, ROS1, and RET [54,55,56,57]. An increased frequency of brain metastases has also been reported for METex14-mutated NSCLC [58]. In our cohort, 20% of patients with metastatic disease had brain metastases at the time of initial diagnosis. In our group’s previous works, we reported frequencies of brain metastases of 40% in patients with EGFR mutations [46], 24% in those with ALK rearrangements [45], 10% in those with BRAF mutations [44], and 9% in those with ROS1 rearrangements [48]. The high incidence of brain metastases in these mutational subgroups highlights the need for agents that can reliably penetrate the blood–brain barrier.

Notably, there were four patients (11.8%) who only had one site of metastasis (i.e., oligometastatic disease). Three of the patients had only adrenal metastases (Figure 1), while one patient only had a soft tissue metastasis. Although a standardized, unified definition for oligometastatic NSCLC has yet to be agreed on, several studies have reported improved outcomes in this subset of patients with limited metastatic burden when subjected to radical treatment with curative intent [59,60]. The true incidence of oligometastatic NSCLC is unknown, which is largely due to the lack of a precise definition. The relatively high incidence of oligometastatic disease in our cohort may partly be a result of referral bias, although further study as to the possible association with METex14 skipping mutations should be considered. To date, no specific molecular genotype has been associated with oligometastatic NSCLC.

Our study has several limitations. Although this is the largest study to date to assess the imaging features and metastatic patterns in METex14-mutated NSCLC, our cohort was still relatively small due to the rarity of METex14 skipping mutations in NSCLC overall. The data were collected retrospectively from a single institution, predisposing to selection and referral bias and potentially limiting its generalizability to larger populations. Despite these limitations, our findings add to the growing understanding of the clinical and radiologic features of METex14-mutated NSCLC.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Patient Identification and Selection

Under an institutional review board-approved protocol (Partners Human Research protocol number 2019P000198), we identified patients who presented to our thoracic medical oncology clinic between January 2013 and December 2018, who met the following criteria: (1) confirmed non-small-cell lung cancer by histology; (2) confirmed METex14 skipping found in the primary tumor or a metastatic lesion; and (3) availability of pre-treatment imaging data for review, obtained either at our institution or at another institution, with the images uploaded into our picture-archiving and communication system (AGFA Impax 6, Mortsel, Belgium). We collected clinicopathologic data, including age, sex, smoking history, tumor histology, and stage of disease at the time of diagnosis.

4.2. Molecular Testing

Molecular testing was performed on tissue samples obtained from either the primary lung tumor or a metastatic lesion. METex14-skipping status was determined using anchored multiplex PCR (AMP) based on next-generation sequencing.

The laboratory-developed test was performed in a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA)-certified laboratory, and its performance was validated for samples showing tumor purity of 5% or higher.

4.3. Imaging Protocol and Image Analysis

All patients had imaging studies performed prior to the initiation of cancer-specific treatment. All computed tomography (CT) examinations were performed on multidetector CTs utilizing helical acquisition with automatic exposure control or fixed mA and tube potentials of up to 120 kV. Unless contraindicated, iodinated intravenous contrast was routinely administered. Positon emission tomography (PET) images when available (n = 53/84) was also reviewed.

CT images closest to diagnosis and prior to any anti-cancer treatment were selected for review. An experienced thoracic radiologist and a fellow in thoracic imaging (SRD and DM) reviewed the images concurrently, and imaging findings were determined and recorded by consensus.

CT features of the primary lung tumor, when identifiable, and patterns of metastases were assessed. The features of the primary tumor that were assessed were: size, density (solid, mixed, ground-glass), location (lobar location and central versus peripheral), and the presence of cavitation, cystic changes, air bronchograms, or calcifications. The tumors involving or at the lobar bronchus were considered central tumors.

The lymph nodes that measured greater than 10 mm in the short axis and/or with increased fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in PET imaging were considered malignant. The presence of metastases in the lungs, pleura, bones, brain, liver, adrenal glands, and other visceral organs was also documented following a review of other imaging studies, including a CT of the abdomen and pelvis, a CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain, and a whole-body PET. Note was also made of pulmonary lymphangitic carcinomatosis. When available, imaging findings were also correlated with surgical pathology to verify nodal and distant metastases.

5. Conclusions

NSCLC with primary METex14 skipping mutations more commonly affected older individuals, without preponderance with respect to sex or smoking status. The primary tumors in NSCLC with primary METex14 skipping mutations tended to present as solid, peripheral masses. While the tumors harboring these mutations mostly have adenocarcinoma histology, there was an increased frequency of tumors with sarcomatoid features. There was also a high frequency of multifocality and extrathoracic metastases, commonly affecting bones, brain, and adrenal glands. A combination of these clinicopathologic and imaging features may suggest the presence of METex14-mutated NSCLC and help identify the subset of patients who may benefit from further molecular genotyping.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.R.D. and R.S.H.; Data curation, S.R.D., D.P.M., E.W.Z., J.K.L., and R.S.H.; Formal analysis, S.R.D. and D.P.M.; Funding acquisition, J.K.L. and R.S.H.; Investigation, S.R. D., D.P.M., E.W.Z., J.K.L., and R.S.H.; Methodology, S.R.D. and R.S.H.; Supervision, S.R.D. and R.S.H.; Validation, S.R.D. and R.S.H.; Visualization, D.P.M.; Writing–original draft, D.P.M.; Writing–review & editing, S.R.D., D.P.M., E.W.Z., J.K.L., and R.S.H.

Funding

This work was funded in part by NIH Grant No. R01 CA225655 (J.K.L.), NIH Grant No. U54 CA224068 (R.S.H.) and Dana Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Lung Cancer SPORE Developmental Project Award.

Conflicts of Interest

D.P.M., E.W.Z., and J.K.L.—none. S.R.D.—Provided independent image analysis through the hospital for clinical research trials programs sponsored by Merck, Pfizer, Bristol Mayer Squibb, Novartis, Roche, Polaris, Cascadian, Abbvie, Gradalis, Clinical Bay, Zai laboratories. Received honorarium from Siemens. R.S.H.—Consulting honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, Apollomics, Tarveda. Research funding (to institution, not to self): Abbvie, Daichii Sankyo, Agios, Novartis, Corvus, Genentech/Roche, Mirati, Millenium, Exelixis, Celgene.

References

- 1.Ettinger D.S., Aisner D.L., Wood D.E., Akerley W., Bauman J., Chang J.Y., Chirieac L.R., D’Amico T.A., Dilling T.J., Dobelbower M., et al. NCCN Guidelines Insights: Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, Version 5.2018. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2018;16:807–821. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2018.0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Planchard D., Popat S., Kerr K., Novello S., Smit E.F., Faivre-Finn C., Mok T.S., Reck M., Van Schil P.E., Hellmann M.D., et al. Metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2019;30:863–870. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mok T.S., Wu Y.-L., Thongprasert S., Yang C.-H., Chu D.-T., Saijo N., Sunpaweravong P., Han B., Margono B., Ichinose Y., et al. Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361:947–957. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maemondo M., Inoue A., Kobayashi K., Sugawara S., Oizumi S., Isobe H., Gemma A., Harada M., Yoshizawa H., Kinoshita I., et al. Gefitinib or chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer with mutated EGFR. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;362:2380–2388. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou C., Wu Y.-L., Chen G., Feng J., Liu X.-Q., Wang C., Zhang S., Wang J., Zhou S., Ren S., et al. Erlotinib versus chemotherapy as first-line treatment for patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (OPTIMAL, CTONG-0802): A multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:735–742. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70184-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soria J.-C., Ohe Y., Vansteenkiste J., Reungwetwattana T., Chewaskulyong B., Lee K.H., Dechaphunkul A., Imamura F., Nogami N., Kurata T., et al. Osimertinib in Untreated EGFR-Mutated Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018;378:113–125. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1713137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaw A.T., Kim D.-W., Nakagawa K., Seto T., Crinó L., Ahn M.-J., De Pas T., Besse B., Solomon B.J., Blackhall F., et al. Crizotinib versus chemotherapy in advanced ALK-positive lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;368:2385–2394. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peters S., Camidge D.R., Shaw A.T., Gadgeel S., Ahn J.S., Kim D.-W., Ou S.-H.I., Pérol M., Dziadziuszko R., Rosell R., et al. Alectinib versus Crizotinib in Untreated ALK-Positive Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017;377:829–838. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1704795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solomon B.J., Besse B., Bauer T.M., Felip E., Soo R.A., Camidge D.R., Chiari R., Bearz A., Lin C.-C., Gadgeel S.M., et al. Lorlatinib in patients with ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer: Results from a global phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:1654–1667. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30649-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shaw A.T., Ou S.-H.I., Bang Y.-J., Camidge D.R., Solomon B.J., Salgia R., Riely G.J., Varella-Garcia M., Shapiro G.I., Costa D.B., et al. Crizotinib in ROS1-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;371:1963–1971. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1406766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siena S., Doebele R.C., Shaw A.T., Karapetis C.S., Tan D.S.-W., Cho B.C., Kim D.-W., Ahn M.-J., Krebs M., Goto K., et al. Efficacy of entrectinib in patients (pts) with solid tumors and central nervous system (CNS) metastases: Integrated analysis from three clinical trials. JCO. 2019;37:3017. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2019.37.15_suppl.3017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Planchard D., Kim T.M., Mazieres J., Quoix E., Riely G., Barlesi F., Souquet P.-J., Smit E.F., Groen H.J.M., Kelly R.J., et al. Dabrafenib in patients with BRAF(V600E)-positive advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: A single-arm, multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:642–650. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)00077-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Planchard D., Smit E.F., Groen H.J.M., Mazieres J., Besse B., Helland Å., Giannone V., D’Amelio A.M., Zhang P., Mookerjee B., et al. Dabrafenib plus trametinib in patients with previously untreated BRAFV600E-mutant metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: An open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:1307–1316. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30679-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network Comprehensive molecular profiling of lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2014;511:543–550. doi: 10.1038/nature13385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Charest A., Wilker E.W., McLaughlin M.E., Lane K., Gowda R., Coven S., McMahon K., Kovach S., Feng Y., Yaffe M.B., et al. ROS fusion tyrosine kinase activates a SH2 domain-containing phosphatase-2/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/mammalian target of rapamycin signaling axis to form glioblastoma in mice. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7473–7481. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yeung S.F., Tong J.H.M., Law P.P.W., Chung L.Y., Lung R.W.M., Tong C.Y.K., Chow C., Chan A.W.H., Wan I.Y.P., Mok T.S.K., et al. Profiling of Oncogenic Driver Events in Lung Adenocarcinoma Revealed MET Mutation as Independent Prognostic Factor. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2015;10:1292–1300. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aisner D.L., Sholl L.M., Berry L.D., Rossi M.R., Chen H., Fujimoto J., Moreira A.L., Ramalingam S.S., Villaruz L.C., Otterson G.A., et al. The Impact of Smoking and TP53 Mutations in Lung Adenocarcinoma Patients with Targetable Mutations-The Lung Cancer Mutation Consortium (LCMC2) Clin. Cancer Res. 2018;24:1038–1047. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-2289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Organ S.L., Tsao M.-S. An overview of the c-MET signaling pathway. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2011;3:S7–S19. doi: 10.1177/1758834011422556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peruzzi B., Bottaro D.P. Targeting the c-Met signaling pathway in cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006;12:3657–3660. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sierra J.R., Tsao M.-S. c-MET as a potential therapeutic target and biomarker in cancer. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2011;3:S21–S35. doi: 10.1177/1758834011422557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cooper C.S., Park M., Blair D.G., Tainsky M.A., Huebner K., Croce C.M., Vande Woude G.F. Molecular cloning of a new transforming gene from a chemically transformed human cell line. Nature. 1984;311:29–33. doi: 10.1038/311029a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park M., Dean M., Cooper C.S., Schmidt M., O’Brien S.J., Blair D.G., Vande Woude G.F. Mechanism of met oncogene activation. Cell. 1986;45:895–904. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90564-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Birchmeier C., Birchmeier W., Gherardi E., Vande Woude G.F. Met, metastasis, motility and more. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003;4:915–925. doi: 10.1038/nrm1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Christensen J.G., Burrows J., Salgia R. c-Met as a target for human cancer and characterization of inhibitors for therapeutic intervention. Cancer Lett. 2005;225:1–26. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Engelman J.A., Zejnullahu K., Mitsudomi T., Song Y., Hyland C., Park J.O., Lindeman N., Gale C.-M., Zhao X., Christensen J., et al. MET amplification leads to gefitinib resistance in lung cancer by activating ERBB3 signaling. Science. 2007;316:1039–1043. doi: 10.1126/science.1141478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Awad M.M., Oxnard G.R., Jackman D.M., Savukoski D.O., Hall D., Shivdasani P., Heng J.C., Dahlberg S.E., Jänne P.A., Verma S., et al. MET Exon 14 Mutations in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Are Associated With Advanced Age and Stage-Dependent MET Genomic Amplification and c-Met Overexpression. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016;34:721–730. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.4600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kong-Beltran M., Seshagiri S., Zha J., Zhu W., Bhawe K., Mendoza N., Holcomb T., Pujara K., Stinson J., Fu L., et al. Somatic mutations lead to an oncogenic deletion of met in lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:283–289. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heist R.S., Shim H.S., Gingipally S., Mino-Kenudson M., Le L., Gainor J.F., Zheng Z., Aryee M., Xia J., Jia P., et al. MET Exon 14 Skipping in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Oncologist. 2016;21:481–486. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paik P.K., Drilon A., Fan P.-D., Yu H., Rekhtman N., Ginsberg M.S., Borsu L., Schultz N., Berger M.F., Rudin C.M., et al. Response to MET inhibitors in patients with stage IV lung adenocarcinomas harboring MET mutations causing exon 14 skipping. Cancer Discov. 2015;5:842–849. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frampton G.M., Ali S.M., Rosenzweig M., Chmielecki J., Lu X., Bauer T.M., Akimov M., Bufill J.A., Lee C., Jentz D., et al. Activation of MET via diverse exon 14 splicing alterations occurs in multiple tumor types and confers clinical sensitivity to MET inhibitors. Cancer Discov. 2015;5:850–859. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jenkins R.W., Oxnard G.R., Elkin S., Sullivan E.K., Carter J.L., Barbie D.A. Response to Crizotinib in a Patient With Lung Adenocarcinoma Harboring a MET Splice Site Mutation. Clin. Lung Cancer. 2015;16:e101–e104. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2015.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim J.H., Kim H.S., Kim B.J. MET inhibitors in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: A meta-analysis and review. Oncotarget. 2017;8:75500–75508. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.20824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.A Study of Capmatinib (INC280) in NSCLC Patients with MET Exon 14 Alterations Who Have Received Prior MET Inhibitor. [(accessed on 26 November 2019)]; Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02750215.

- 34.Felip E., Horn L., Patel J.D., Sakai H., Scheele J., Bruns R., Paik P.K. Tepotinib in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) harboring MET exon 14-skipping mutations: Phase II trial. JCO. 2018;36:9016. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.36.15_suppl.9016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tepotinib Phase II in Non-small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) Harboring MET Alteration. [(accessed on 26 November 2019)]; Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02864992.

- 36.Capmatinib in Patients with Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Harboring cMET Exon 14 Skipping Mutation. [(accessed on 26 November 2019)]; Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03693339.

- 37.CABozantinib in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) Patients with MET Deregulation. [(accessed on 26 November 2019)]; Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03911193.

- 38.Wolf J., Seto T., Han J.-Y., Reguart N., Garon E.B., Groen H.J.M., Tan D.S.-W., Hida T., De Jonge M.J., Orlov S.V., et al. Capmatinib (INC280) in METΔex14-mutated advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): Efficacy data from the phase II GEOMETRY mono-1 study. JCO. 2019;37:9004. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakada T., Okumura S., Kuroda H., Uehara H., Mun M., Takeuchi K., Nakagawa K. Imaging Characteristics in ALK Fusion-Positive Lung Adenocarcinomas by Using HRCT. Ann. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2015;21:102–108. doi: 10.5761/atcs.oa.14-00093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang H., Schabath M.B., Liu Y., Han Y., Li Q., Gillies R.J., Ye Z. Clinical and CT characteristics of surgically resected lung adenocarcinomas harboring ALK rearrangements or EGFR mutations. Eur. J. Radiol. 2016;85:1934–1940. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2016.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cheng Z., Shan F., Yang Y., Shi Y., Zhang Z. CT characteristics of non-small cell lung cancer with epidermal growth factor receptor mutation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. Imaging. 2017;17:5. doi: 10.1186/s12880-016-0175-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yoon H.J., Sohn I., Cho J.H., Lee H.Y., Kim J.-H., Choi Y.-L., Kim H., Lee G., Lee K.S., Kim J. Decoding Tumor Phenotypes for ALK, ROS1, and RET Fusions in Lung Adenocarcinoma Using a Radiomics Approach. Medicine. 2015;94:e1753. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rizzo S., Petrella F., Buscarino V., Maria F.D., Raimondi S., Barberis M., Fumagalli C., Spitaleri G., Rampinelli C., Marinis F.D., et al. CT Radiogenomic Characterization of EGFR, K-RAS, and ALK Mutations in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Eur. Radiol. 2016;26:32–42. doi: 10.1007/s00330-015-3814-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mendoza D.P., Dagogo-Jack I., Chen T., Padole A., Shepard J.-A.O., Shaw A.T., Digumarthy S.R. Imaging characteristics of BRAF-mutant non-small cell lung cancer by functional class. Lung Cancer. 2019;129:80–84. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2019.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mendoza D.P., Lin J.J., Rooney M.M., Chen T., Sequist A., Shaw A.T., Digumarthy S.R. Imaging features and metastatic patterns of advanced ALK-positive non-small cell lung cancer. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2019. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Digumarthy S.R., Mendoza D.P., Padole A., Chen T., Peterson P.G., Piotrowska Z., Sequist L.V. Diffuse Lung Metastases in EGFR-Mutant Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Cancers. 2019;11:1360. doi: 10.3390/cancers11091360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Digumarthy S.R., Padole A.M., Gullo R.L., Sequist L.V., Kalra M.K. Can CT radiomic analysis in NSCLC predict histology and EGFR mutation status? Medicine. 2019;98:e13963. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000013963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Digumarthy S.R., Mendoza D.P., Lin J.J., Chen T., Rooney M.M., Chin E., Sequist L.V., Lennerz J.K., Gainor J.F., Shaw A.T. Computed Tomography Imaging Features and Distribution of Metastases in ROS1-rearranged Non-Small-cell Lung Cancer. Clin. Lung Cancer. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2019.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mendoza D.P., Stowell J., Muzikansky A., Shepard J.-A.O., Shaw A.T., Digumarthy S.R. Computed Tomography Imaging Characteristics of Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer With Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase Rearrangements: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Lung Cancer. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2019.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zheng Z., Liebers M., Zhelyazkova B., Cao Y., Panditi D., Lynch K.D., Chen J., Robinson H.E., Shim H.S., Chmielecki J., et al. Anchored multiplex PCR for targeted next-generation sequencing. Nat. Med. 2014;20:1479–1484. doi: 10.1038/nm.3729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Midha A., Dearden S., McCormack R. EGFR mutation incidence in non-small-cell lung cancer of adenocarcinoma histology: A systematic review and global map by ethnicity (mutMapII) Am. J. Cancer Res. 2015;5:2892–2911. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fan J., Dai X., Wang Z., Huang B., Shi H., Luo D., Zhang J., Cai W., Nie X., Hirsch F.R. Concomitant EGFR Mutation and EML4-ALK Rearrangement in Lung Adenocarcinoma Is More Frequent in Multifocal Lesions. Clin. Lung Cancer. 2019;20:e517–e530. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2019.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang S.X.Y., Lei L., Guo H.H., Shrager J., Kunder C.A., Neal J.W. Synchronous primary lung adenocarcinomas harboring distinct MET Exon 14 splice site mutations. Lung Cancer. 2018;122:187–191. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2018.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Baek M.Y., Ahn H.K., Park K.R., Park H.-S., Kang S.M., Park I., Kim Y.S., Hong J., Sym S.J., Park J., et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor mutation and pattern of brain metastasis in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2018;33:168–175. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2015.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Drilon A., Lin J.J., Filleron T., Ni A., Milia J., Bergagnini I., Hatzoglou V., Velcheti V., Offin M., Li B., et al. Frequency of Brain Metastases and Multikinase Inhibitor Outcomes in Patients With RET-Rearranged Lung Cancers. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2018;13:1595–1601. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Patil T., Smith D.E., Bunn P.A., Aisner D.L., Le A.T., Hancock M., Purcell W.T., Bowles D.W., Camidge D.R., Doebele R.C. The Incidence of Brain Metastases in Stage IV ROS1-Rearranged Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer and Rate of Central Nervous System Progression on Crizotinib. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2018;13:1717–1726. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gadgeel S., Gandhi L., Riely G., Chiappori A., West H., Azada M., Morcos P., Lee R., Garcia L., Yu L., et al. Safety and activity of alectinib against systemic disease and brain metastases in patients with crizotinib-resistant ALK-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer (AF-002JG): Results from the dose-finding portion of a phase 1/2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:1119–1128. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70362-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Song Z., Wang H., Yu Z., Lu P., Xu C., Chen G., Zhang Y. De Novo MET Amplification in Chinese Patients With Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer and Treatment Efficacy With Crizotinib: A Multicenter Retrospective Study. Clin. Lung Cancer. 2019;20:e171–e176. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2018.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Luketich J.D., Martini N., Ginsberg R.J., Rigberg D., Burt M.E. Successful treatment of solitary extracranial metastases from non-small cell lung cancer. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1995;60:1609–1611. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(95)00760-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schanne D.H., Heitmann J., Guckenberger M., Andratschke N.H.J. Evolution of treatment strategies for oligometastatic NSCLC patients - A systematic review of the literature. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2019;80:101892. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2019.101892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]