ABSTRACT

Microvesicles (MVs), a plasma membrane-derived subclass of extracellular vesicles, are produced and released into the circulation during systemic inflammation, yet little is known of cell/tissue-specific uptake of MVs under these conditions. We hypothesized that monocytes contribute to uptake of circulating MVs and that their increased margination to the pulmonary circulation and functional priming during systemic inflammation produces substantive changes to the systemic MV homing profile. Cellular uptake of i.v.-injected, fluorescently labelled MVs (J774.1 macrophage-derived) in vivo was quantified by flow cytometry in vascular cell populations of the lungs, liver and spleen of C57BL6 mice. Under normal conditions, both Ly6Chigh and Ly6Clow monocytes contributed to MV uptake but liver Kupffer cells were the dominant target cell population. Following induction of sub-clinical endotoxemia with low-dose i.v. LPS, MV uptake by lung-marginated Ly6Chigh monocytes increased markedly, both at the individual cell level (~2.5-fold) and through substantive expansion of their numbers (~8-fold), whereas uptake by splenic macrophages was unchanged and uptake by Kupffer cells actually decreased (~50%). Further analysis of MV uptake within the pulmonary vasculature using a combined model approach of in vivo macrophage depletion, ex vivo isolated perfused lungs and in vitro lung perfusate cell-based assays, indicated that Ly6Chigh monocytes possess a high MV uptake capacity (equivalent to Kupffer cells), that is enhanced directly by endotoxemia and ablated in the presence of phosphatidylserine (PS)-enriched liposomes and β3 integrin receptor blocking peptide. Accordingly, i.v.-injected PS-enriched liposomes underwent a redistribution of cellular uptake during endotoxemia similar to MVs, with enhanced uptake by Ly6Chigh monocytes and reduced uptake by Kupffer cells. These findings indicate that monocytes, particularly lung-marginated Ly6Chigh subset monocytes, become a dominant target cell population for MVs during systemic inflammation, with significant implications for the function and targeting of endogenous and therapeutically administered MVs, lending novel insights into the pathophysiology of pulmonary vascular inflammation.

KEYWORDS: Extracellular vesicles, microvesicles, monocytes, systemic inflammation, pulmonary vasculature

Introduction

Microvesicles (MVs), also termed microparticles or ectosomes and defined as extracellular vesicles (EVs) produced by blebbing of the plasma membrane [1–3], are produced as a direct response to cell stimulation or stress [4]. Within the circulation, MVs from different vascular cell populations are elevated under systemic inflammatory conditions including chronic low-grade responses implicated in cardiovascular diseases (e.g. hypertension, atherosclerosis) [5,6], and more acute systemic inflammation (e.g. sepsis, major trauma) [7], with diagnostic and prognostic associations found depending on MV subtype/cell source. The pathogenic potential of MVs relates primarily to their pro-coagulant activity derived from surface phosphatidylserine (PS) and tissue factor expression [8], as well as their pro-inflammatory activity derived from their cargo mediators [9]. MVs have been proposed to function within the vasculature as potent “long-range” signalling vehicles in organ-to-organ intercellular communication due to the protection of their membrane-encapsulated cargo from dilution, neutralization or degradation within the circulation [5]. Conversely, intravascular administration of EVs (MVs and exosomes) derived from mesenchymal stem cells has been shown to have tissue-specific therapeutic potential, for example, producing anti-inflammatory and homoeostatic effects in acute [10] and chronic lung injury [11]. The biological and therapeutic actions of MVs will depend upon the nature and vascular location of their interactions with target cells and, crucially, potential modifications/alterations of these interactions during inflamed or diseased states [5,12]. In vivo tracking of systemically administered MVs under normal resting conditions has demonstrated rapid removal from the circulating blood [13,14] due to uptake mainly by fixed resident macrophages of the liver and spleen [14–16], yet little is known of circulating MV uptake during systemic inflammation, in particular, MV subtypes produced acutely (e.g. myeloid cell neutrophil- and macrophage/monocyte-derived) under such conditions [17–19].

As an early response to systemic or local inflammation, monocytes and neutrophils are mobilized from bone marrow into the circulation, expanding their vascular pools several-fold. In mice, a large proportion of these cells, particularly monocytes of the Ly6Chigh “inflammatory” subset, become “marginated” away from circulating blood to the microvascular beds, including those of the lungs and liver, where they are functionally primed and contribute to local inflammation as well as innate defences [20–22]. In vitro, human monocytes are capable of binding to and internalizing MVs with multiple functional consequences, [23–27] indicating they could play a role as a “mobile”, non-fixed target cell population for circulating MVs in vivo. However, in vivo studies on MV trafficking appear to have neglected this possibility, with most focus placed just on whole organ MV accumulation or MV uptake by “fixed” intravascular cell populations (i.e. resident intravascular macrophages such as Kupffer cells and vascular endothelial cells).

We hypothesized that during systemic inflammation, the expanded and primed population of lung-marginated monocytes becomes a major target for circulating MVs. To assess this possibility, we quantified in vivo uptake of systemically administered MVs by flow cytometry at the individual cell/tissue levels with further investigations ex vivo by isolated lung perfusion and in vitro using pulmonary perfusate cells. We used a model of subclinical endotoxaemia with iv injection of low-dose LPS [21], which produces significant lung margination and priming of leukocytes, while at the same time minimizing various confounding effects of acute systemic inflammation (e.g. cardiorespiratory depression, shock, substantive release of endogenous MVs). A macrophage cell line (J774.1) stimulated with extracellular ATP was chosen as an in vitro source of MVs for injection based on the elevation of circulating mononuclear phagocyte-derived MVs during acute systemic inflammation [17–19], and the well-defined ATP-P2X7 receptor pathway of inflammatory MV release from mononuclear phagocytes [9,26,28–30].

Materials and methods

Animal husbandry

All protocols were reviewed and approved by the UK Home Office in accordance with the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986, UK. Male C57BL/6 mice (Charles River Laboratories, Margate, UK) ages 10–12 weeks (22–26 g) were used (n = 132 in total) for all protocols.

In vitro production and labelling of MVs

To provide a defined, inflammation-relevant and abundant source of MVs for in vivo tracking studies in mice, we used the semi-adherent J774A.1 macrophage cell line (ECACC, UK: ECACC-91051511) which produces EVs rapidly in response to extracellular ATP stimulation via the P2X7 receptor signalling pathway [26]. Activation of the P2X7 receptor by a typical danger signal ATP is a potent stimulus for MV release and is central to the development of sterile and infectious inflammation and tissue injury [31]. Confluent cells in 60 mm tissue culture dishes were rinsed multiple times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, with calcium and magnesium) to remove any cellular debris and EVs, and then stimulated for 30 min, with 3 mM ATP (Bio-Techne, UK) in PBS at 37°C. Although more prolonged exposure (>2 h) to ATP at this concentration can produce non-apoptotic cytotoxicity in J774 cells [32], and other cell types [33], viability was high (>90%) in cells harvested from plates after this brief ATP stimulation, in agreement with the previous study [32]. Released EVs were isolated by differential centrifugation in an Eppendorf angle rotor (FA45-30-11) microfuge at 300 × g at 4°C for 10 min to pellet cells, followed by medium speed centrifugation of the supernatant at 20,800 × g at 4°C for 15 min to enrich MVs in pellets. EV preparations were labelled with 1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindodicarbocyanine (DiD, Thermo Fisher Scientific, UK), a lipophilic, far-red fluorescent dye previously used in in vivo and in vitro EV uptake studies [34–36] The pellet was resuspended with PBS, 0.5% clinical-grade human albumin solution (HAS) and incubated at room temperature with DiD, prediluted (30 µM) in Diluent C (Sigma), at a final concentration 5 µM for 7 min. The mixture was then further diluted with PBS-HAS and washed twice by centrifugation (20,800 × g, 15 min) with careful removal of supernatant to remove unbound DiD. MV-specific DiD staining was assessed by flow cytometry in combination with plasma membrane markers and comparison to typical exosome markers. To assess levels of MV incorporated DiD versus unbound DiD, labelled and washed preparations were incubated with anti-CD11b immunomagnetic microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec) at 1 × 108 DiD/CD45/CD11b-positive events per 50 µl of microbeads for 30 min at 4°C. Application to magnetized LS columns (Miltenyi Biotec) was followed by collection of unbound flow-through and column-bound fractions. DiD fluorescence was measured in PBS, Triton X-100 (0.5%) at 635 nm/680 nm excitation/emission in a Biotek FLx800 plate reader.

Liposomes

Liposomes were supplied by Encapsula NanoSciences (Brentwood, TN, USA) as phosphatidylcholine only (PC-liposomes) and phosphatidylcholine and PS at a 1:1 molar ratio (“PS-liposomes”) sized to 100 nm using high-pressure argon extrusion. DiD labelling of PS-liposomes for in vivo experiments was performed as for MVs.

In vivo model of subclinical endotoxemia and MV challenge

Sub-clinical endotoxemia was induced by single, low-dose LPS (20 ng, Ultrapure Escherichia coli O111:B4; InvivoGen, Toulouse, France) i.v. injection [21]. For determination of MV uptake, a standardized dose of DiD-labelled MVs (2.4 × 105 fluorescence units/200 µl, equivalent to a count of ~1.0 × 108 MVs) suspended in PBS was injected i.v. via the tail vein to either untreated or LPS-pretreated mice. After 1 h, mice were anesthetized, heparinized and exsanguinated, before rapid excision and processing of total lung and spleen, and a weighed portion of the liver, for flow cytometric analysis.

Macrophage depletion in vivo

Intravascular-resident macrophages and monocytes were depleted by i.v. injection of 0.2 ml of clodronate-encapsulated liposomes (FormuMax Scientific, Palo Alto, CA, USA). MV challenge experiments were performed after 72 h when vascular Ly6Chigh monocytes were repopulated from the bone marrow reservoir but before significant restoration of blood Ly6Clow monocytes [21,37,38], or liver and splenic macrophages (Supplementary Figure S1) [39,40].

Isolated perfused lung (IPL)

For assessing pulmonary intravascular uptake of MVs in isolation from the systemic circulation, mouse IPL was performed as described by us in recent publications [41,42]. In brief, untreated or low-dose LPS pretreated (i.v., 20 ng, 2 h) mice were injected i.p. with xylaxine (13 mg/kg)/ketamine (130 mg/kg) to induce general anaesthesia, injected i.v. via a tail vein with 20 IU of heparin, and the trachea intubated and connected to the ventilator on continuous positive airway pressure of 5 cm H2O. After exsanguination via the inferior vena cava, the pulmonary artery and left atrium were cannulated and perfusion performed with RPMI-1640 supplemented with 4% clinical-grade human albumin solution at a slow rate of 0.1 ml/min increasing gradually to a constant flow rate of 25 ml/kg/min with an open, non-recirculating circuit to remove blood and loosely marginated cells in a total perfusate volume of 3 ml. Perfusion was then switched to the closed, recirculating circuit (volume 2.5 ml) and the same fluorescence-standardized dose of MVs as used in vivo was infused via the perfusion circuit reservoir and recirculated for 1 h.

In vitro MV uptake assay

Mechanisms of MV uptake were investigated in vitro using leukocytes from the pulmonary circulation as the most anatomically relevant and abundant source, contrasting with blood where monocytopenia severely limits cell recovery during endotoxemia. Following terminal anaesthesia and heparinization, inflated lungs were perfused with HBSS (without Ca2+/Mg2+)-albumin (4%) via the pulmonary artery at a high constant flow of 50 ml/h for 12 min for maximal recovery of blood and marginated cells from the left atrium. Based on preliminary evaluations of MV uptake (Supplementary Figure S2), in vitro incubations of MVs with washed perfusate cells were performed at standardized density of 5 × 104 Ly6Chigh monocytes/ml in HBBS-HAS (with Ca2+/Mg2+) in Eppendorfs with continuous mixing for 1 h.

Flow cytometry

Single-cell suspensions were prepared from excised tissue as described previously [43] with minor modifications. Tissues were disaggregated in formaldehyde fixative in MACS C tubes (Miltenyi Biotec) with a gentleMACS™ Dissociator (Miltenyi Biotec Ltd., Bisley, UK) for 1 min. For cell counts, ice-cold flow cytometry wash buffer (PBS, 2% FCS, 0.1 mM sodium azide, 2 mM EDTA) was added directly to suspensions, or for DiD detection, after a further 5 min fixation at room temperature. This method of combining rapid tissue disaggregation and cell dispersal with simultaneous fixation aimed to minimize any MV binding and internalization at the point of tissue harvest, contrasting with standard enzyme-based tissue disaggregation methods that require relatively prolonged incubations at 37°C. For quantification of cell surface receptor expression, single-cell suspensions were prepared by enzyme digestion with collagenase A (1 mg/ml, Sigma) and DNAse1 (0.1 mg/ml, Roche) at 37°C for 20 min. Cell suspensions were sieved through a 40 µm cell strainer (Greiner Bio-One, UK) and washed prior to antibody staining. The following specificity fluorophore-conjugated rat anti-mouse (unless stated otherwise) mAbs were used: CD45 (30-F11), CD11b (M1/70), F4/80 (BM8), Ly-6G (1A8), Ly-6C (HK1.4), NK-1.1 (PK136), MHCII (M5/114.15.2), CD31 (MEC13.3), CD41 (MWReg30), MerTK (2B10C42), TIM4 (RMT4-54), CD51 (RMV-7), CD9 (MZ3), CD63 (NVG-2), LAMP2 (M3/84), hamster anti-CD61 (HMβ3-1), CD68 (FA-11), CD36 (HM36), CD81 (Eat-2) all from Biolegend (London, UK); human anti-CD204 (REA148) from Miltenyi Biotec Ltd.; and anti-MARCO (ED31) from Bio-Rad (Watford, UK). Gating strategies for intravascular monocyte subsets and neutrophils were based on CD11b, Ly6G, Ly6C, F4/80, MHCII, NK1.1 staining as previously described [41,43,44]. Kupffer cells and splenic macrophages were identified as CD45+, CD11b-low/med and F4/80+ [45] (Supplementary Figure S1) and endothelial cells as CD31-positive and CD41/CD45-negative [22]. Cell counts were determined using Accucheck counting beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Samples were acquired using a Cyan ADP flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, High Wycombe, UK), with EV events acquired using a side scatter trigger threshold. Analysis of data was performed using Flowjo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR, USA). MV uptake for each cell population was quantified as cell-associated DiD mean (geometric) fluorescence intensity (MFI). Total MV uptake per organ was calculated as: [cell-associated DiD MFI for each mouse – group mean background fluorescence (untreated mice) MFI] × group mean cell count/organ.

Confocal microscopy

Cell suspensions were treated with Red Blood Cell Lysis Solution (Miltenyi Biotech Ltd.) and leukocytes fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Washed cells were stained with biotinylated anti-Ly6C biotin-conjugated mAb (clone HK1.4, BioLegend) at 4°C overnight, followed by Alexa Fluor-488 streptavidin (BioLegend) for 1 h at room temperature. Cells were cytospin-centrifuged onto polylysine-coated slides (Sigma) and mounted with ProLong™ Gold Antifade Mountant with DAPI (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Images were obtained using a Zeiss LSM-510 inverted confocal microscope, with Zeiss KS-300 software and analysed using FIJI software.

Data analysis

Normality was determined using QQ plots and Shapiro–Wilk tests using IBM SPSS 25 software. Group comparisons were made by Student’s t-tests, by ANOVA with Bonferroni tests, or by Friedman with Dunn’s tests, using GraphPad Prism 6.0. Data are presented as mean ± SD or median with interquartile ranges (median ± IQR). Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Results

Production and characterization of fluorescently labelled J774-derived EVs

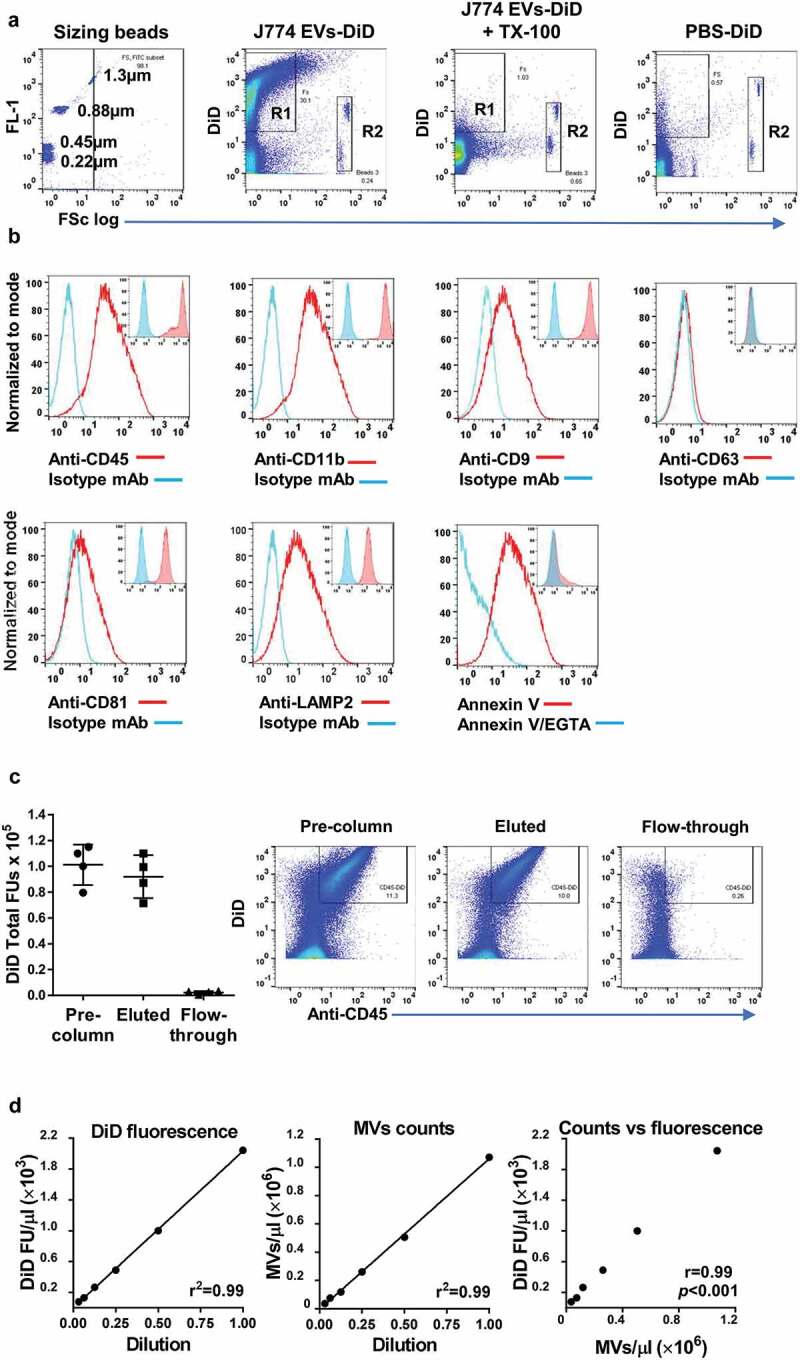

EVs were generated in vitro from the mouse macrophage J774 cell line via ATP stimulation of the P2X7 receptor inflammatory signalling pathway [26]. Cell-depleted supernatants were centrifuged at medium speed (20,800 × g) for MV enrichment and labelled with DiD. Flow cytometric analysis indicated the majority of DiD-positive events were <1 µm (Figure 1(a)) and therefore unlikely to be apoptotic bodies [46]. Expression of plasma membrane surface markers, CD11b and CD45 (Figure 1(b)) on EVs was consistent with the “right-side-out” membrane orientation of MVs from myeloid cells [1]. Staining of the DiD-labelled EVs for previously described exosome markers, the tetraspanins CD9, CD63 and CD81 [47], and the lysosome-associated membrane protein, LAMP2 [48] indicated that although CD9, CD81 and LAMP2 were clearly detectable on EVs they were also expressed at high levels on the plasma membrane of untreated parent J774 cells. By contrast, surface CD63 was absent from both EVs and cells. Similarities between expression profiles of tetraspanins on EVs and the parental cell membrane have been described previously in other cell lines [49]. Finally, staining with annexin V indicated exposure of the membrane phospholipid, PS, a more generic marker of MVs [50] than of exosomes [51]. Similar marker profiles were observed on EVs released from LPS-stimulated J774s (Supplementary Figure S3), but this method of production required longer incubation times (≥4 h) for significant EV yield, increasing the likelihood of apoptotic body formation.

Figure 1.

DiD-labelling and analysis of ATP-induced J774 EVs. J774 cells were stimulated with ATP (3 mM, 30 min), and the released EVs labelled with DiD and analysed by flow cytometry. (a): Comparison with fluorescent sizing calibration beads (Sperotech) indicated that the forward scatter (FSc) of most DiD-positive events (R1) was lower than that of the 1.3 µm beads and all lower than the ~6 µm diameter Accucheck counting beads (R2). Incubation of samples with non-ionic detergent (Triton X-100, 0.1%) resulted in the disappearance all DiD-positive events consistent with their vesicular nature [78], while incubation and centrifugation of DiD in buffer without EVs (PBS-DiD) produced relatively few fluorescence-positive events (b): The subcellular origin of DiD-positive J774 EVs was assessed by staining with phycoerythrin-conjugated monoclonal antibodies (mAb) against typical myeloid cell membrane (CD45, CD11b) and exosome (CD9, CD63, CD81, LAMP2) markers. Positive staining of EVs (main histogram overlays) corresponded well to the staining pattern of viable untreated J774s (inset histogram overlays), suggesting DiD-positive EVs were derived mainly from the plasma membrane. Note that J774 cells do express CD9, CD81 and LAMP2, but not CD63 on their surface. Surface exposure of phosphatidylserine (PS) on DiD-labelled EVs was evident from their staining with FITC-conjugated annexin V and its reversal by incubation with the calcium cation chelator EGTA (5 mM). (c): The majority of DiD fluorescence in labelled samples was present in CD45+ EVs bound to and eluted from anti-CD11b conjugated immunomagnetic microbeads, with very low levels of fluorescence in the unbound column flow-through. (d): Serial 2-fold dilutions of DID-labelled EV preparations indicated linearity and correlation (Pearson correlation coefficient) in the detectable range of DiD fluorescence units (FU) measurement and the flow cytometric MV counts (DiD/CD11b double-positive events).

To further characterize the preparation, we quantified the amount of DiD fluorescence associated with the CD11b-positive EV fraction by binding to anti-CD11b immunomagnetic microbeads. The majority of DiD fluorescence was associated with the column-bound and eluted CD11b microbead fraction (Figure 1(c)), with only a minor fraction remaining unbound in the column flow-through. Based on these analyses and the steps taken to reduce apoptotic body formation (brief stimulation period) and exosome recovery (medium centrifugation speed), we concluded that the DiD-labelled material prepared for uptake experiments was enriched with “MVs” as defined as plasma membrane-derived EVs [46,52].

In vivo uptake of circulating MVs during low-grade systemic inflammation

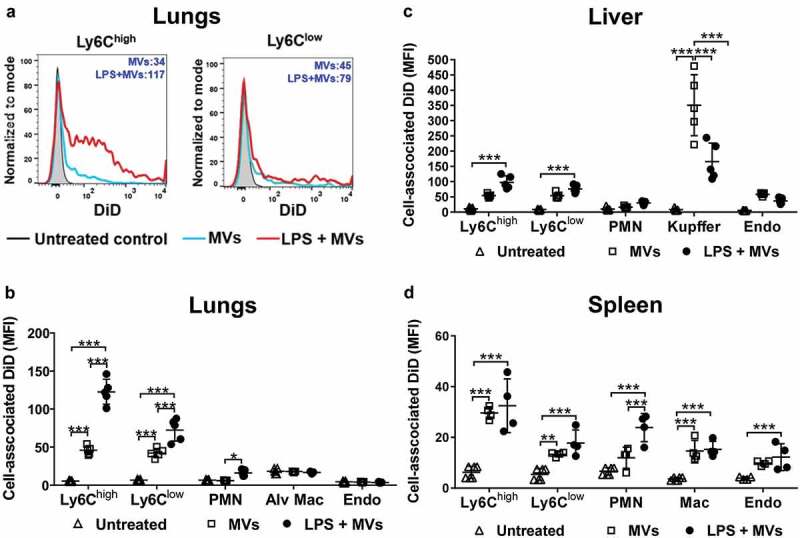

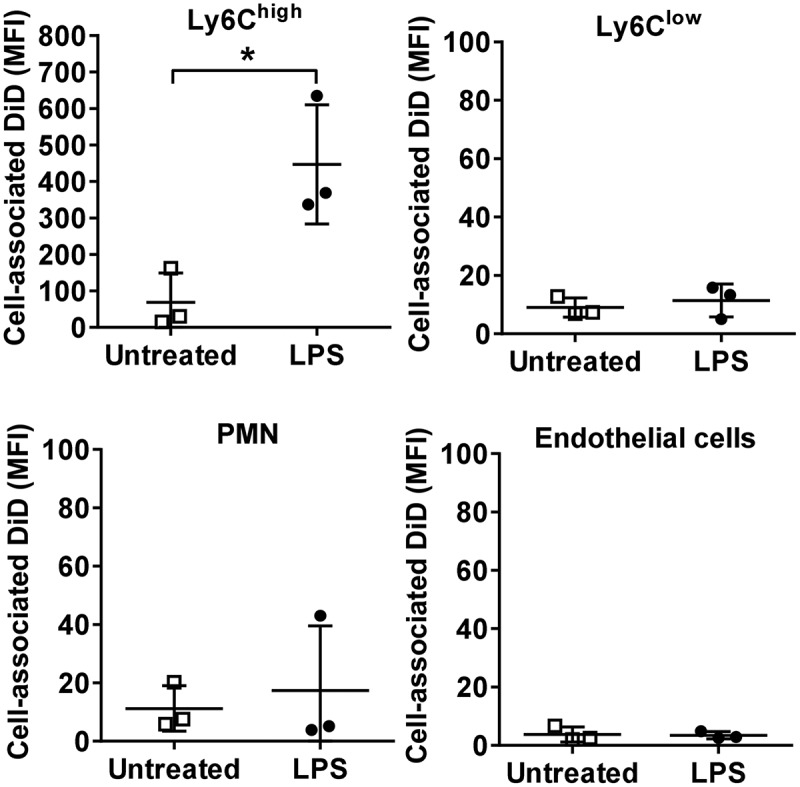

To assess in vivo cell- and organ-specific uptake of exogenously administered MVs in mice under inflamed or diseased states, we used low-dose LPS i.v. injection to induce a sub-acute, systemic intravascular inflammation. We have previously shown that such subclinical endotoxemia produces a marked expansion of the marginated pool of monocytes within the pulmonary microvasculature that were functionally primed towards secondary stimuli [21]. Freshly generated J774 MVs were DiD fluorescence-labelled and injected i.v. into untreated or LPS-pretreated (2 h) mice, and cell-associated DiD fluorescence in the lungs, liver and spleen quantified by flow cytometry (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Uptake of circulating MVs during low-grade systemic inflammation. DiD-labelled MVs (240,000 FU) were injected i.v. into untreated or low-dose LPS-treated (20 ng, i.v. 2 h) mice. At 1 h post-MV injection, lungs, liver and spleen were harvested for preparation of fixed single-cell suspensions and analysis by flow cytometry. Histograms overlay plots are shown from individual mice for cell-associated DiD fluorescence in lung monocyte Ly6Chigh and Ly6Clow subsets (a). DiD MFI values for MV- and LPS+MV-treated mice are displayed in each plot. Cell-associated DiD fluorescence is indicated (mean fluorescence intensity: MFI) as a measure of MV uptake per cell in each of the cell populations (b–d). Data are displayed as mean ± SD and analysed by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction tests. n = 4–5, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

In normal mice, MV uptake was highest in the liver Kupffer cells (Figure 2(c)), consistent with a previous study assessing uptake of i.v.-injected erythrocyte-derived MVs [14]. Significant, but lower-level MV uptake was also observed in other resident intravascular cell populations: hepatic endothelial cells and splenic macrophages. In the lungs, where significant numbers of marginated monocytes and neutrophils are already present under baseline conditions [41,44], MV uptake was evident in both monocyte subsets (Ly6Chigh and Ly6Clow), but not in neutrophils, pulmonary endothelial cells, or alveolar macrophages (Figure 2(a,b)). Alveolar macrophages were analysed as an extravascular phagocytic population not exposed directly to circulating MVs in vivo, and therefore their complete lack of DiD staining ruled out the possibility of any artefactual uptake of MVs/DiD by all cells with the rapid, non-enzymatic method of tissue disaggregation and fixation used here. Following low-dose LPS injection, MV uptake increased in both monocyte subsets in all organs, but this was most pronounced in lung-marginated Ly6Chigh monocytes. Low-level MV uptake by neutrophils was also detectable in the lungs and spleen. Unexpectedly, MV uptake by liver Kupffer cells was decreased by ~50% (p < 0.001) during endotoxemia (Figure 2(c)).

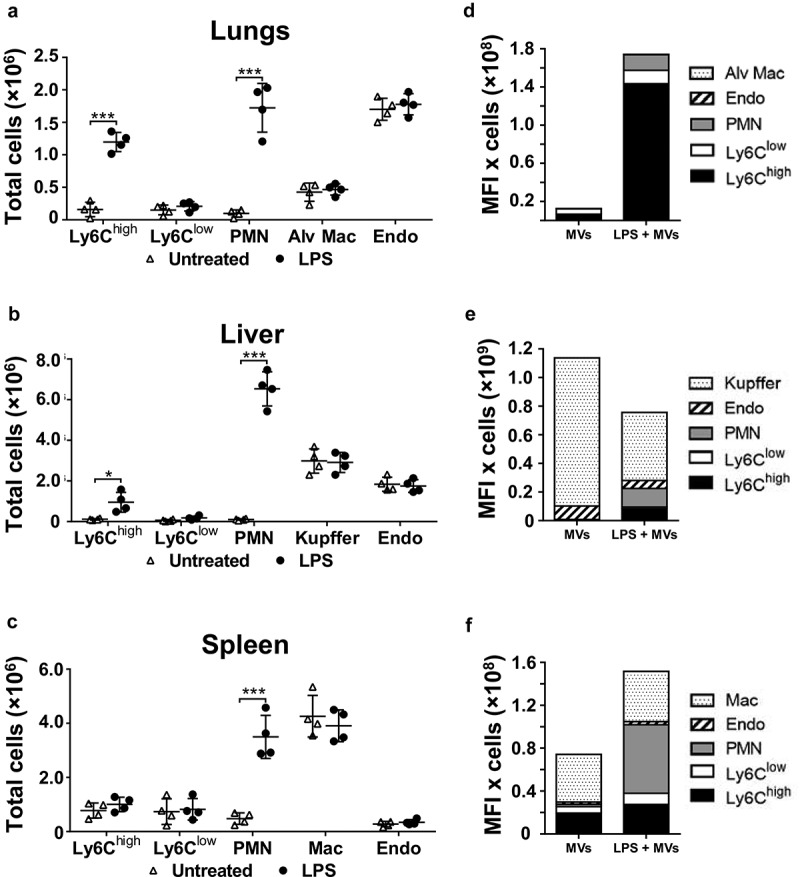

Cell numbers in tissue single-cell suspensions were determined in a separate group of mice to assess the net contribution of each cell population within each organ to MV uptake under normal and LPS-treated conditions (Figure 3). At 2 h post-LPS, prior to injection of MVs, substantial increases in Ly6Chigh monocyte numbers occurred in the lungs and liver but not in the spleen (Figure 3(a–c)). In the exsanguinated blood (Supplementary Figure S4), only a fraction of the monocytes found in organs were present, whereas neutrophil numbers increased in all organs and blood. Estimation of cellular MV uptake per organ (cell-associated DiD MFI in Figure 1(a–c) × cell count/organ in Figure 3(a–c); see methods) indicated a clear and dramatic increase (>20-fold) in the pulmonary vasculature (Figure 3(d)), attributable almost solely to the marginated Ly6Chigh monocyte pool. Reduced MV uptake by Kupffer cells during endotoxemia translated into reduced liver uptake overall, despite an increased contribution from Ly6Chigh monocytes and neutrophils (Figure 3(e)). In the spleen, total MV uptake increased moderately during systemic inflammation due to increased monocyte and neutrophil uptake (Figure 3(f)), but with no change in resident macrophage uptake.

Figure 3.

Organ cell counts and redistribution of MV uptake. Total cell counts for fixed (macrophages and endothelial cells) and non-fixed (monocytes and neutrophils) populations were determined for lungs, liver and spleen at 2 h after low-dose LPS injection (20 ng, i.v.)(a–c). Total uptake of MVs and per each organ type (d–f) was estimated (see Methods) by calculating the individual mouse cell-associated DiD MFI values (data in Figure 2) × group mean cell counts/organ (a–c). Cell count data are displayed as mean ± SD and analysed by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction tests. n = 4, *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001. Total MV uptake per organ is shown as cell population means in stacked bar plots.

MV uptake by lung-marginated monocytes vs. intravascular macrophages

The inverse effects of endotoxemia on MV uptake by Ly6Chigh monocytes and Kupffer cells suggested a dynamic and reciprocal relationship, with the potential for competition between the two cell populations. To elucidate this relationship, we performed MV challenge experiments in mice pretreated with clodronate-liposomes. This treatment initially depletes all intravascular mononuclear phagocytes including monocytes, but after 72 h intravascular Ly6Chigh monocytes are re-populated by a newly differentiated population from the bone marrow reserve whereas Ly6Clow monocytes and intravascular macrophages (Kupffer cells and splenic macrophages) remain depleted (Figure 4(a), Supplementary Figure S1) [21,37–40]. In clodronate-pretreated mice, in which higher levels of MVs remained present in plasma 1 h after injection (Figure 4(b); Supplementary Figure S5), there was a substantial increase in MV uptake by lung-marginated Ly6Chigh monocytes compared to normal mice (Figure 4(c)). These data suggest that marginated monocytes can uptake more MVs when they are exposed to higher circulating MV levels. Subclinical endotoxemia in these macrophage-depleted mice induced a further increase in MV uptake by lung-marginated Ly6Chigh monocytes (MFI: 476 ± 116), even exceeding the level observed in Kupffer cells in both normal and LPS-challenged mice (MFI: 350 ± 100 and 166 ± 60, Figure 1(a)), indicating that MV uptake capacity of these monocytes per se is substantively enhanced in response to inflammatory stimuli. The combination of macrophage depletion with endotoxemia also produced significant increases in MV uptake by endothelial cells within the lungs, higher than in normal mice (Figure 1(a)), further demonstrating the importance of “MV availability” in the regulation of MV uptake by intravascular cells.

Figure 4.

MV uptake by pulmonary vascular cells in macrophage-depleted mice. Mice were injected with clodronate-liposomes (“clod-lipo”) (i.v., 0.2 ml) and at 72 h, when Ly6Chigh monocytes, but not macrophages or Ly6Clow monocytes, were fully repopulated from bone marrow, mice were injected i.v. with low-dose LPS (20 ng) followed by DiD-labelled MVs after 2 h. Repopulation of Ly6Chigh monocytes in clodronate-treated mice was confirmed in lungs with their numbers similar to normal mice and substantially increased at 2 h post-LPS injection (a). Counts of circulating DiD-labelled MVs were determined in plasma at 1 h post-i.v. injection in normal and clodronate-liposome pre-treated mice (−72 h) (b). Cell-associated DiD levels (MFI) were determined in intravascular populations, including the remaining Ly-6Clow monocytes, at 1 h after MV injection, (c). Data are displayed as mean±SD and analysed by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction tests. n = 4, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

MV uptake in isolated perfused lungs ex vivo

Next, we performed pulmonary vascular MV uptake experiments using our established isolated perfused lung (IPL) system [41,42], as a novel approach to analyse organ-specific MV uptake by which all systemic variables are eliminated, including potential non-specific effects of the intravascular macrophage depletion procedure. Lungs from normal untreated or low-dose LPS-challenged mice were flushed briefly at low flow rates to remove only the residual blood and loosely marginated blood cells [41], followed by infusion of DiD-labelled J774-derived MVs and recirculating lung perfusion (using serum-free buffer, under mechanical ventilation for 1 h). Cell-associated DiD fluorescence analysed in lung cell suspensions (Figure 5) indicated that MV uptake was almost exclusive to Ly6Chigh monocytes and clearly higher in lungs from endotoxemic mice, confirming the direct effects of inflammation on the MV uptake capacity of these monocytes. With sustained availability of MVs in the IPL closed system (MVs were detectable in perfusate at the end of experiments), DiD fluorescence in Ly6Chigh monocytes reached levels (MFI: 447 ± 164) comparable to those observed in vivo in macrophage-depleted mice (MFI: 476 ± 116, Figure 4).

Figure 5.

MV uptake in isolated perfused lungs (IPL). Lungs from normal or low-dose LPS-treated (20 ng i.v., 2 h) mice were perfused and mechanically ventilated using the IPL system. After a brief, slow flow-rate flush (5 min) to remove non-marginated cells, DiD-labelled MVs (240,000 FU) were infused into the perfusion circuit and recirculated for 1 h followed by determination of cell-associated DiD levels (MFI). Data are displayed as mean ± SD and analysed by t-tests. n = 3, *p < 0.05.

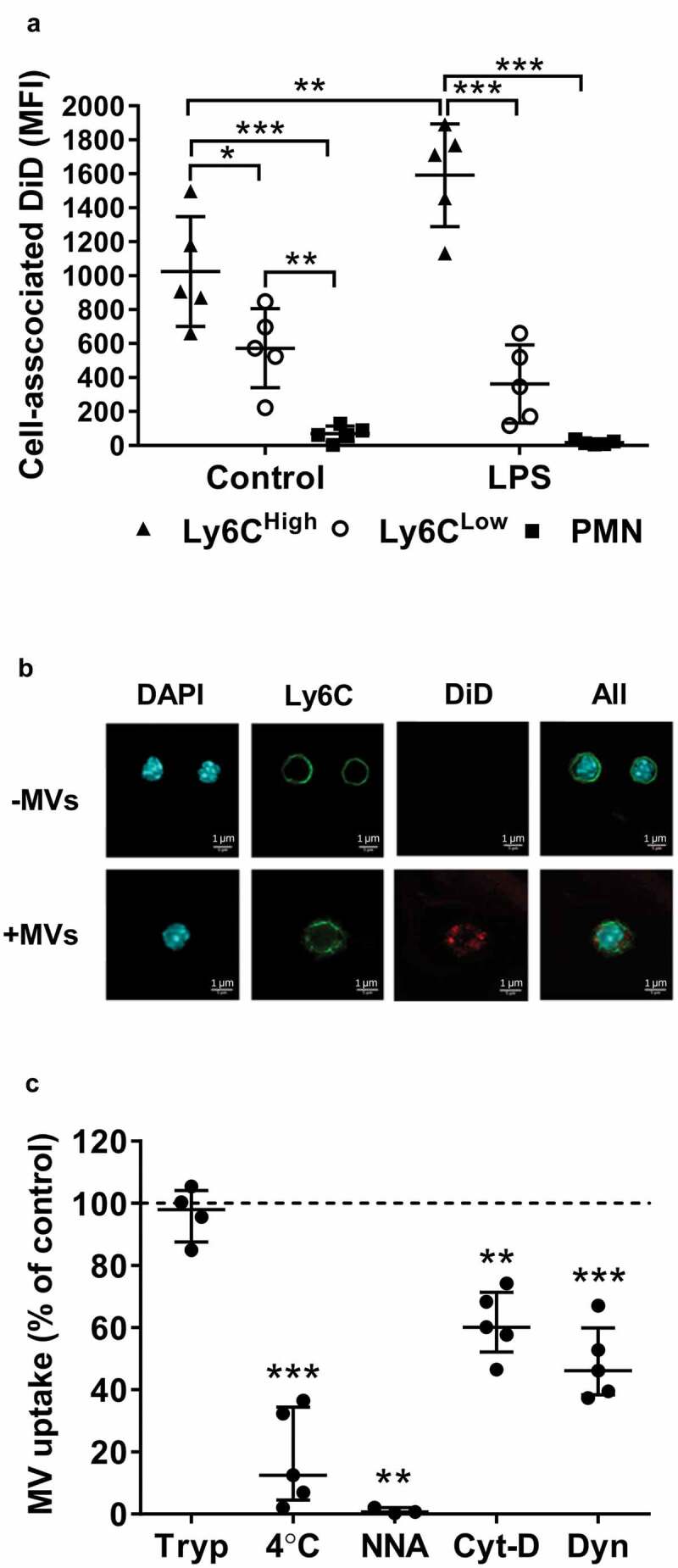

In vitro assessment of MV uptake by lung-marginated Ly6Chigh monocytes

To further address the mechanisms of MV uptake by lung Ly6Chigh monocytes, we developed a novel in vitro assay using cells obtained by pulmonary vascular perfusion as an anatomically relevant (as well as abundant) source of monocytes. Lung-marginated leukocytes were harvested from untreated and low-dose LPS-challenged mice by ex vivo pulmonary perfusion and incubated in vitro with DiD-labelled J774-derived MVs. Under these conditions, the relative differences in uptake between subsets and increases due to endotoxemia were similar to those in vivo (Figure 6(a)). Internalization of MVs by Ly6Chigh monocytes was observed by confocal microscopy as punctate marks separated from plasma membrane anti-Ly6C antibody staining (Figure 6(c)), as well as by the robust resistance of cell-associated DiD signal when cells were treated with trypsin post-MV incubation (Figure 6(d)). Significant inhibition of MV uptake by low temperature, energy depletion treatments (incubation with NaF, NaN3 and antimycin A), and cytochalasin D and dynasore treatments to inhibit active endocytic processes [53], provided further evidence that internalization of MVs was unlikely to involve passive processes (such as MV-cell membrane fusion) or an artefact related to binding of any free DiD to the monocyte membrane. This latter possibility was also excluded by the lack of any significant cell-associated fluorescence following incubation of perfusate cells with DiD dye-only preparations, produced by the same incubation and centrifugation steps used for MV staining (Supplementary Figure S2: C&D).

Figure 6.

Lung-marginated Ly6Chigh monocytes internalize MVs. (a): Intravascular cells harvested from mice by high flow rate pulmonary artery perfusion (non-enzymatic) were incubated in suspension with DiD-labelled MVs (100,000 FU/ml) for 1 h. Cell-associated DiD levels (MFI) were compared in monocyte subsets and neutrophils in lung perfusates from normal and low-dose LPS-treated (20 ng, i.v. 2 h) mice. (b): MV uptake by Ly6Chigh monocytes from LPS-treated mice was assessed by confocal imaging (1000×) of membrane-localized anti-Ly6C antibody (Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated) and nuclear staining with DAPI. In MV-treated cells (lower row), the DiD signal (red) was intracellular and not co-localized with Ly6C. (c): MV internalization was assessed quantitatively by: (1) trypsin treatment of cells post-MV-DiD incubation to remove any surface-bound MVs; (2) MV-cell co-incubation at 4°C or energy depletion (NNA: NaF, NaN3 and antimycin A) to differentiate between active and passive uptake; or (3) inhibitors of cytoskeleton rearrangement (Cyt-D: cytochalasin D) and dynein (Dyn: dynasore) to inhibit endocytic processes. All numerical data are displayed as mean ± SD and analysed by t-tests ((c): MV only vs. NNA treatment); one-way ANOVA ((c), except NNA); two-way ANOVA (a) with Bonferroni correction tests. n = 3–5.

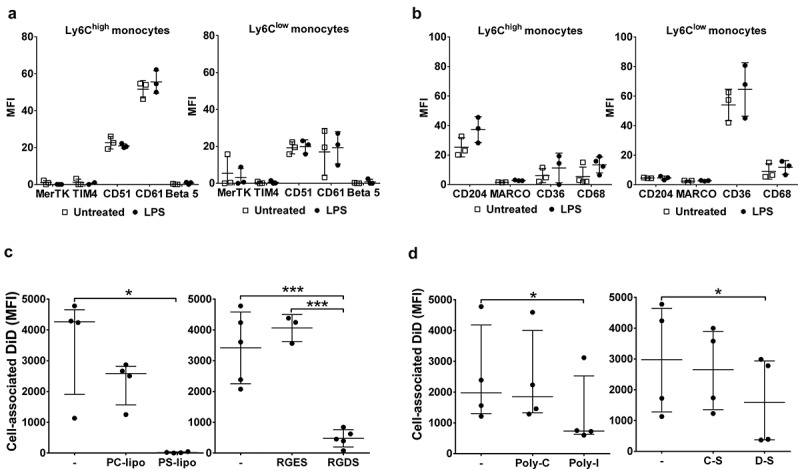

Using this in vitro assay system, we investigated the receptor-based mechanisms involved in MV uptake by Ly6Chigh monocytes. First, we measured expression of several known PS and scavenger receptors on lung monocytes and, for comparison, Kupffer cells, both harvested from untreated or LPS-treated mice. Of the receptors expressed on monocytes (Figure 7(a,b)) and Kupffer cells (Supplementary Figure S6), there was no substantial change in their levels during endotoxemia. There was, however, a clear heterogeneity of expression between monocyte subsets: Ly6Chigh monocytes expressed higher levels of integrin subunit β3 (CD61) involved in PS recognition [54] (p < 0.01) and scavenger receptor class A type I/II (CD204) (p < 0.01); while scavenger receptor class B (CD36) was almost exclusively expressed by the Ly6Clow subset (p < 0.01). We then assessed the effects of various inhibitors for these receptors on MV uptake by perfusate Ly6Chigh monocytes. Pre-incubation of perfusate cells with PC:PS-liposomes, but not PC-only liposomes, entirely abolished MV uptake by Ly6Chigh monocytes, and pre-incubation with the integrin-binding RGD motif peptide (RGDS) [54] resulted in nearly complete ablation of the uptake (Figure 7(c)), together strongly indicating an essential role for PS-αVβ3 integrin-dependent mechanisms. Pre-incubation with scavenger receptor A blockers, i.e. polyinosinic acid and dextran sulphate, partially inhibited MV uptake, by ~50%, compared to the respective negative control polymers (polycytidylic acid and chondroitin sulphate) (Figure 7(d)), also suggesting a contribution of CD204 in this MV uptake process.

Figure 7.

Receptor-dependent mechanisms of MV uptake by lung-marginated Ly6Chigh monocytes. (a) & (b): In vivo expression of PS and scavenger receptors on monocyte subsets were determined in lung single cell suspensions from normal and LPS-treated mice (20 ng, i.v. 2 h) by flow cytometry. (c): MV uptake by lung Ly6Chigh monocytes isolated by perfusion of individual LPS-treated mice was assessed in the presence of PS liposomes (PS-lipo) or RGDS peptide, in comparison to the respective controls, PC liposomes (PC-lipo) and RGES peptide. (d): MV uptake by lung Ly6Chigh monocytes from individual LPS-treated mice was similarly assessed in the presence of scavenger receptor A blockers: polyinosinic acid (Poly-I) and dextran sulphate (D-S), in comparison to the respective controls, polycytidylic acid (Poly-C) and chondroitin sulphate (C-S). Data are displayed as mean ± SD and analysed by multiple t-tests (a,b), one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction tests ((c), peptide blocking), or as median ± IQR and analysed by Friedman with Dunn’s correction tests ((c), liposome blocking; (d)). n = 3 for receptor expression and n = 3–5 for blocking experiments.

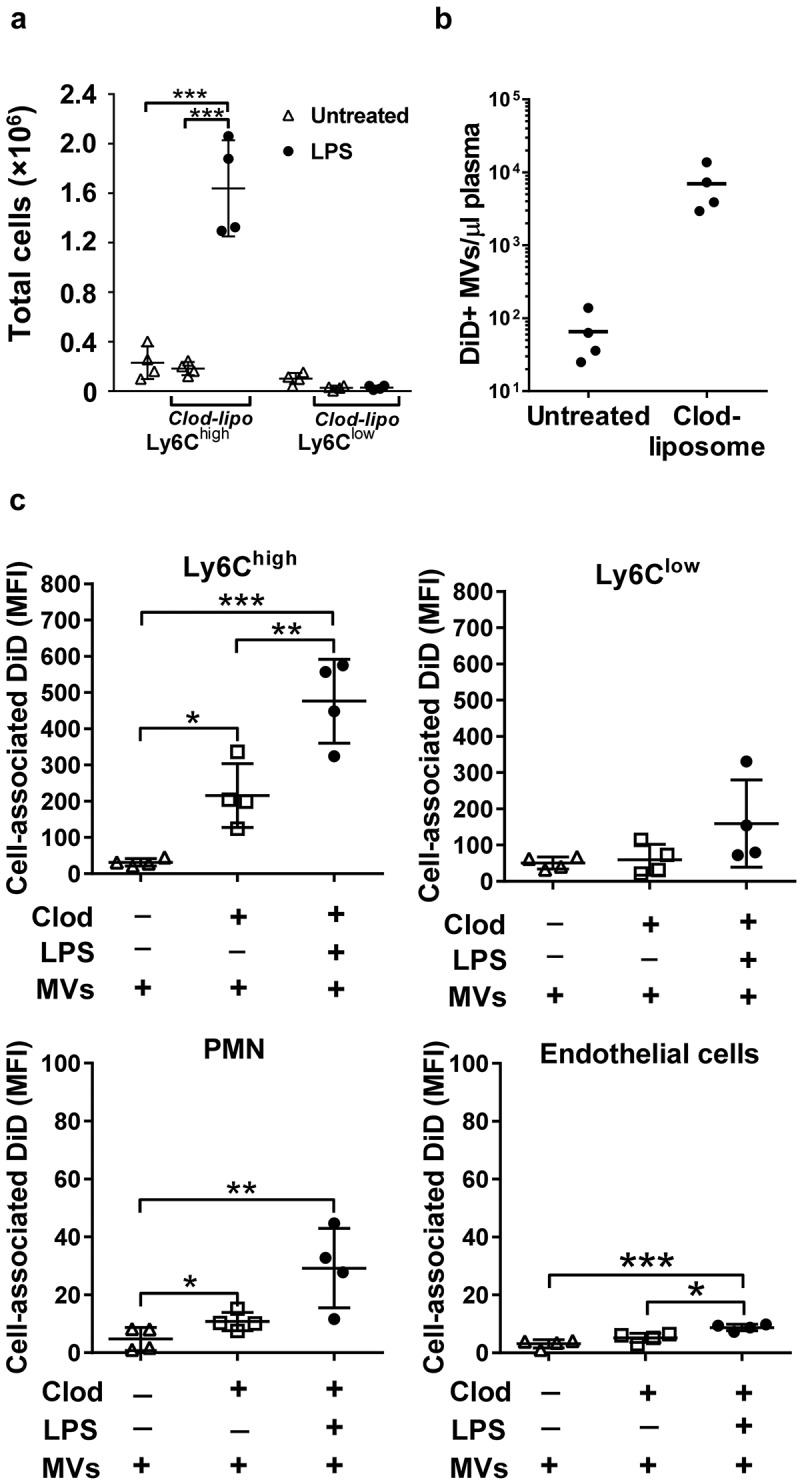

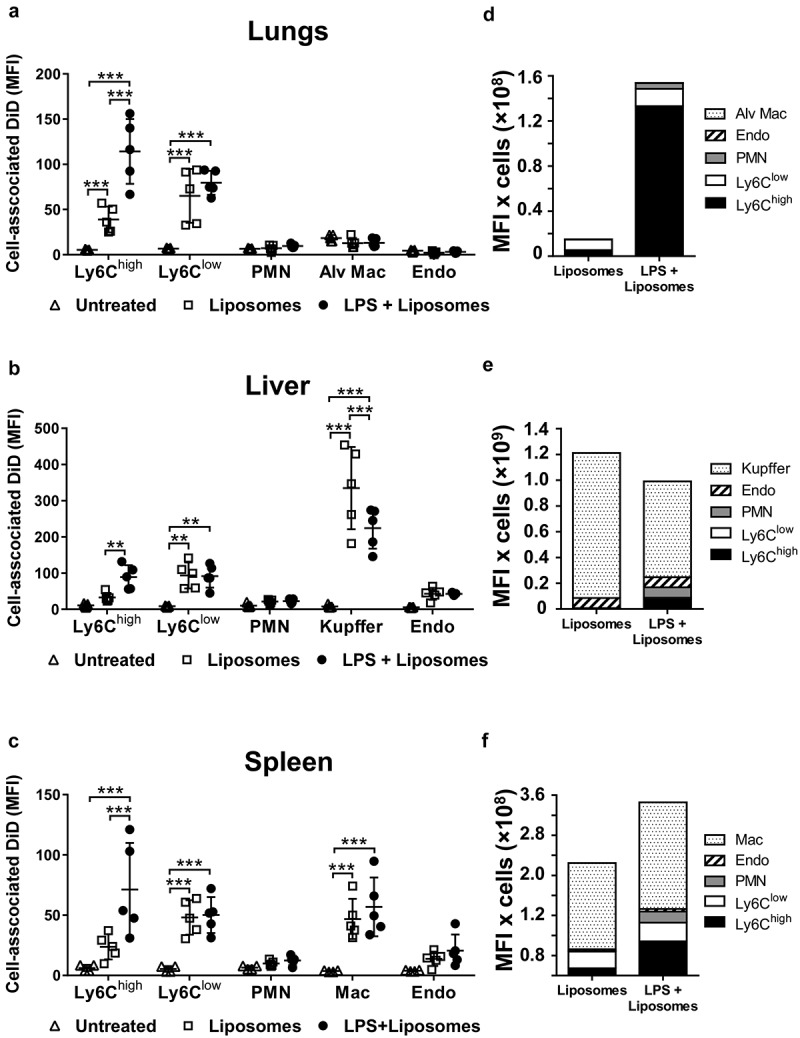

Uptake of PS-liposomes in vivo

PS is present on the surface of most MVs, including the J774-derived MVs used here Figure 1(b)) and is a critical determinant of MV uptake by various target cell types in vivo and in vitro [14,15,55,56]. To assess the importance of PS recognition on redistribution of MV uptake during endotoxemia, we investigated in vivo uptake of PS-enriched liposomes labelled with DiD. As with J774-derived MVs, endotoxemia resulted in enhanced uptake of PS-liposomes by lung-marginated Ly6Chigh monocytes (Figure 8(a,d); Supplementary Figure S7) and their diminished uptake by Kupffer cells (Figure 8(b)). There were some qualitative differences from J774-derived MVs, most notably that PS-liposome uptake was not significantly increased in Ly6Clow monocytes or neutrophils during endotoxemia.

Figure 8.

Uptake of circulating PS liposomes during low-grade systemic inflammation. DiD-labelled liposomes were injected i.v. into untreated or low-dose LPS-treated (20 ng, i.v. 2 h) mice. At 1 h post-MV injection, lungs (a), liver (b) and spleen (c) were harvested for preparation of fixed single-cell suspensions and analysis by flow cytometry. Cell-associated DiD fluorescence is indicated (MFI) as a measure of liposome uptake per cell in each of the cell populations. Total uptake of PS-liposomes and per each organ type (d–f) was estimated (see Methods) by calculating the individual mouse cell-associated DiD MFI values (a–c) × group mean cell counts/organ (data in Figure 3). Data are displayed as mean ± SD and analysed by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction tests. n = 5, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Discussion

Elevated production and levels of MVs within the circulating blood, particularly MVs of myeloid cell origin, is a common response to systemic inflammation [17,18,57,58], yet remarkably little is known of MV trafficking and cellular uptake under these conditions. We demonstrated here that even with a low-grade subclinical intravascular inflammation, profiles of cell- and tissue-specific MV uptake can change rapidly and dramatically. An early and substantive increase of MV uptake by Ly6Chigh monocytes during subclinical endotoxemia was accompanied by no change in uptake by splenic macrophages and a decrease in liver Kupffer cells. Concurrently, expansion of the monocyte “marginated” pool led to a further intravascular redistribution of MV uptake, most strikingly to the pulmonary vasculature. Considering the multitude of functions attributed to MVs in vitro, these in vivo findings point to a critical and dynamic relationship between MVs and monocytes during systemic inflammation.

We used systemic administration of fluorescently labelled MVs from extracellular ATP-stimulated macrophages [26] and quantitative flow cytometric analysis of rapidly disaggregated and fixed, single-cell suspensions, to compare cellular uptake of circulating MVs within and between different organs. Under control conditions, we found a similar profile of MV uptake by cells within the liver to the study by Willekens et al [14] in which radiolabeled erythrocyte-derived MVs accumulated predominantly in Kupffer cells (>90%), with the remainder in the endothelial cells. Liver and splenic macrophages have also been shown to play a dominant role in clearance of i.v.-injected exosomes (fluorescence-labelled) in normal mice [59]. However, despite evidence of monocyte–MV interactions taking place under in vitro conditions [24–26,55], in vivo studies assessing MV uptake [14–16] have not clearly demonstrated MV uptake by monocytes marginated to the peripheral microvasculature. The comprehensive cell subpopulation analysis performed here, including of mononuclear phagocyte subtypes, not only demonstrated that significant MV uptake by monocytes occurs in vivo for the first time, but also suggested that monocytes have the potential to substantively redirect MV uptake away from fixed, tissue-resident macrophages during systemic inflammation. As this involvement of monocytes in MV uptake occurs with only a mild subclinical inflammatory insult, it is likely to be a common occurrence and potentially prevalent across a wide range of chronic cardiovascular and metabolic disorders where persistent low-grade inflammation plays a role [60]. For example, pro-inflammatory Ly6Chigh monocytes have recently been implicated in atherosclerosis aggravated by subclinical endotoxemia [61], suggesting that enhanced monocyte uptake of circulating MVs, as observed here following low-dose LPS treatment, could potentially have a role in the atherogenic process.

Reduced MV uptake by Kupffer cells during endotoxemia may reflect a generalized phenomenon, as depression of liver phagocytic clearance has been reported with bacterial and particulate challenges [62,63]. As the dominant target cell of MVs, reduced Kupffer cell uptake capacity may delay circulating MV clearance and increase their availability to other intravascular populations, including monocytes. However, our findings, in particular, the results of IPL experiments, demonstrated that LPS enhanced MV uptake by lung-marginated Ly6Chigh monocytes “per se” and that they have a substantial reserve uptake capacity equivalent to that of Kupffer cells. Thus, an expanded pool of functionally activated monocytes marginated within the pulmonary vasculature may, conversely, exert some measurable impact on Kupffer cell uptake in the liver. However, the similar levels of MV uptake by individual monocytes in the lungs and liver suggests that vascular bed location per se is not a primary determinant of the reduced uptake by Kupffer cells following LPS treatment. Irrespective of the dynamic relationship between monocyte- and macrophage-mediated MV clearance, the observed outcome of increased “net” MV uptake by Ly6Chigh monocytes (>20-fold, in Figure 3(d)) within the pulmonary vasculature represents a physiologically significant re-routing of systemically released MVs during inflammation. This monocyte-mediated preferential homing of circulating MVs to the lungs should therefore be considered carefully when evaluating organ-specific effects of any exogenously injected “therapeutic” MVs (e.g. i.v. injection of mesenchymal stem cell-derived MVs).

Systemic release of MVs can produce “off-target” pathophysiological effects, best exemplified by the potential for dissemination of their pro-coagulant activity [64–66]. MV capture and internalization by marginated pools of monocytes within the pulmonary circulation may serve as an additional protective physiological mechanism augmenting hepatic clearance, in step with increased MV release into the circulation. However, when MV production is excessive or hepatic clearance mechanism is impaired (e.g. liver dysfunction) following local or systemic insults, this MV uptake by the lungs could become pathogenic producing significant “off-target” effects and leading to pulmonary intravascular inflammation, as suggested by studies of systemic and lung inflammation induced by injection of erythrocyte-derived MVs [67,68].

Direct effects of EV preparations on monocytes have been demonstrated previously under in vitro conditions, including acute induction of cytokine expression and effects on their differentiation patterns and phenotypic polarization [23–27]. There is evidence that EV RNA transfer to target cells plays a role in the delayed phenotypic effects [25], whereas acute pro-inflammatory responses have been ascribed to EV phospholipids and TLR4 signalling [26]. In mice, lung-marginated monocytes, in particular, the Ly6Chigh “inflammatory” subset, play a central role in orchestrating the development of pulmonary vascular inflammation and acute lung injury [21,22,41,43,69]. Thus, monocyte-mediated homing of circulating MVs under inflammatory states could potentially have implications in the pathophysiology of acute and chronic lung diseases, e.g. acute respiratory distress syndrome following sepsis or major trauma, or development of pulmonary hypertension. Our findings also suggest that caution is required when attempting to directly extrapolate results on MV uptake and functions under “in vitro” closed system conditions to the more dynamic and diverse microenvironments in vivo. For instance, uptake of MVs by pulmonary endothelial cells was not detectable in vivo under both normal conditions and endotoxemia but became apparent with the more sustained elevation of circulating MVs in macrophage-depleted mice. Thus, further exploration of MV uptake and function within the pulmonary vasculature is warranted, employing model systems that incorporate intact organ physiology and vascular dynamics (e.g. ex vivo IPL).

Our results of in vitro receptor-blocking experiments on lung perfusate cells suggest an essential role for recognition of the anionic phospholipid, PS, in MV uptake by the Ly6Chigh monocytes. PS translocation to the outer plasma membrane is fundamental to MV blebbing process and is likely to be a key determinant of MV uptake by macrophages [15], endothelial cells [56] and human monocytes [55]. The similar uptake pattern of PS-liposomes to MVs observed in vivo broadens the relevance of the findings to other MV subtypes/sources and potentially to synthetic vesicles with similar physical properties. Uptake of synthetic, negatively charged microparticles by Ly6Chigh monocytes was recently demonstrated in vivo and proposed to have therapeutic potential in reducing their pro-inflammatory functions through premature removal and apoptotic death within the spleen [70]. Interestingly, the class A scavenger receptor, MARCO, was implicated as the primary uptake receptor in that study, which, although detected at only very low levels on monocytes here and elsewhere [71], could be the target of polylinosinic acid- and dextran sulphate-mediated inhibition of MV uptake, alongside CD204. Thus, it appears that there is likely to be significant overlap in monocyte uptake mechanisms between MVs and exogenously administered immunomodulatory microparticles (e.g. i.v.-injected mesenchymal stem cell-derived MVs or synthetic microparticles), which would be an important consideration for such therapeutic interventions.

In contrast to PS-dependent uptake as a relatively “generic” determinant of MV homing, the right-side-out plasma membrane orientation of MVs has the potential to confer additional, more specific cell/tissue adhesive properties, reflecting those of the parent cell phenotype and subject to change during inflammation. Inflammation-enhanced targeting of anti-adhesion molecule antibody-coated nanoparticles to the vascular endothelium [72,73] indicates the potential for this phenomenon to occur with MVs. Although tissue-specific homing of EVs in vivo has been reported [36,74,75], these studies used high-speed differential centrifugation protocols, potentially limiting MV content. Investigation of exogenously administered MV uptake within the circulation during acute systemic inflammation is likely to be confounded by several factors, including endogenous MV release. Therefore, as a next step towards the identification of novel MV-cell/tissue-specific interactions during system inflammation, combined ex vivo/in vitro modelling approaches will be essential.

We used extracellular ATP stimulation of macrophages as a physiologically relevant method for acute, non-apoptotic release of EVs in vitro [30]. MVs were enriched by a differential centrifugation protocol that included an initial low-speed centrifugation step (300 × g, 10 min) to remove cells, whilst ensuring maximum recovery of larger MVs within the whole population. Although higher speeds (e.g. 1500–2000 × g) are often used for removal of cell debris, larger EVs (e.g. apoptotic bodies) and platelets, they have been shown to reduce MV recovery substantially (~75%) [17,76] presumably due to overlapping sedimentation rates. To exclude cell debris as well as constitutively released EVs from preparations, we performed multiple rinses of the adherent cultures prior to stimulation. Nonetheless, as differential centrifugation does not produce pure EV subtype preparations [48,77], some “contamination” of MVs with exosomes and apoptotic bodies is likely and, as such, studies using isolated MVs should be considered with this caveat.

In summary, intravascular uptake of circulating MVs during subclinical endotoxemia was modified through rapid expansion of the vascular pool of marginated and primed monocytes and reduced uptake by liver-resident macrophages. Based on the tissues examined, the impact of increased monocyte uptake was most pronounced in the pulmonary vasculature and therefore relevant to the development and evolution of diseases such as acute respiratory distress syndrome and pulmonary hypertension, as well as in the therapeutic intravascular targeting of any exogenously injected MVs or other subcellular particles.

Supplementary Material

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

References

- [1].Stein JM, Luzio JP.. Ectocytosis caused by sublytic autologous complement attack on human neutrophils. The sorting of endogenous plasma-membrane proteins and lipids into shed vesicles. Biochem J. 1991;274(Pt 2):381–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Thery C, Ostrowski M, Segura E.. Membrane vesicles as conveyors of immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:581–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Cocucci E, Meldolesi J. Ectosomes and exosomes: shedding the confusion between extracellular vesicles. Trends Cell Biol. 2015;25:364–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Yanez-Mo M, Siljander PR, Andreu Z, et al. Biological properties of extracellular vesicles and their physiological functions. J Extracell Vesicles. 2015;4:27066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Loyer X, Vion AC, Tedgui A, et al. Microvesicles as cell-cell messengers in cardiovascular diseases. Circ Res. 2014;114:345–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Amabile N, Guignabert C, Montani D, et al. Cellular microparticles in the pathogenesis of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2013;42:272–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Raeven P, Zipperle J, Drechsler S. Extracellular vesicles as markers and mediators in sepsis. Theranostics. 2018;8:3348–3365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Morel O, Toti F, Hugel B, et al. Procoagulant microparticles: disrupting the vascular homeostasis equation? Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:2594–2604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Soni S, O’Dea KP, Tan YY, et al. ATP redirects cytokine trafficking and promotes novel membrane tnf signaling via microvesicles. Faseb J. 2019;33:6442–6455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Gennai S, Monsel A, Hao Q, et al. Microvesicles derived from human mesenchymal stem cells restore alveolar fluid clearance in human lungs rejected for transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2015;15:2404–2412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Willis GR, Fernandez-Gonzalez A, Anastas J, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cell exosomes ameliorate experimental bronchopulmonary dysplasia and restore lung function through macrophage immunomodulation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197:104–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Rautou PE, Mackman N. Del-etion of microvesicles from the circulation. Circulation. 2012;125:1601–1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Rand ML, Wang H, Bang KW, et al. Rapid clearance of procoagulant platelet-derived microparticles from the circulation of rabbits. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:1621–1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Willekens FL, Werre JM, Kruijt JK, et al. Liver kupffer cells rapidly remove red blood cell-derived vesicles from the circulation by scavenger receptors. Blood. 2005;105:2141–2145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Dasgupta SK, Abdel-Monem H, Niravath P, et al. Lactadherin and clearance of platelet-derived microvesicles. Blood. 2009;113:1332–1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Al Faraj A, Gazeau F, Wilhelm C, et al. Endothelial cell-derived microparticles loaded with iron oxide nanoparticles: feasibility of mr imaging monitoring in mice. Radiology. 2012;263:169–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].O’Dea KP, Porter JR, Tirlapur N, et al. Circulating microvesicles are elevated acutely following major burns injury and associated with clinical severity. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0167801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Nieuwland R, Berckmans RJ, McGregor S, et al. Cellular origin and procoagulant properties of microparticles in meningococcal sepsis. Blood. 2000;95:930–935. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Aras O, Shet A, Bach RR, et al. Induction of microparticle- and cell-associated intravascular tissue factor in human endotoxemia. Blood. 2004;103:4545–4553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Doerschuk CM. Mechanisms of leukocyte sequestration in inflamed lungs. Microcirculation. 2001;8:71–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].O’Dea KP, Wilson MR, Dokpesi JO, et al. Mobilization and margination of bone marrow Gr-1high monocytes during subclinical endotoxemia predisposes the lungs toward acute injury. J Immunol. 2009;182:1155–1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].O’Dea KP, Young AJ, Yamamoto H, et al. Lung-marginated monocytes modulate pulmonary microvascular injury during early endotoxemia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:1119–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Danesh A, Inglis HC, Jackman RP, et al. Exosomes from red blood cell units bind to monocytes and induce proinflammatory cytokines, boosting T-cell responses in vitro. Blood. 2014;123:687–696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Danesh A, Inglis HC, Abdel-Mohsen M, et al. Granulocyte-derived extracellular vesicles activate monocytes and are associated with mortality in intensive care unit patients. Front Immunol. 2018;9:956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ismail N, Wang Y, Dakhlallah D, et al. Macrophage microvesicles induce macrophage differentiation and mir-223 transfer. Blood. 2013;121:984–995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Thomas LM, Salter RD. Activation of macrophages by P2X7-induced microvesicles from myeloid cells is mediated by phospholipids and is partially dependent on tlr4. J Immunol. 2010;185:3740–3749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Bardelli C, Amoruso A, Federici Canova D, et al. Autocrine activation of human monocyte/macrophages by monocyte-derived microparticles and modulation by ppar-gamma ligands. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;165:716–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Pizzirani C, Ferrari D, Chiozzi P, et al. Stimulation of P2 receptors causes release of IL-1beta-loaded microvesicles from human dendritic cells. Blood. 2007;109:3856–3864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Bianco F, Pravettoni E, Colombo A, et al. Astrocyte-derived atp induces vesicle shedding and IL-1 beta release from microglia. J Immunol. 2005;174:7268–7277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].MacKenzie A, Wilson HL, Kiss-Toth E, et al. Rapid secretion of interleukin-1beta by microvesicle shedding. Immunity. 2001;15:825–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Adinolfi E, Giuliani AL, De Marchi E, et al. The P2X7 receptor: a main player in inflammation. Biochem Pharmacol. 2018;151:234–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Murgia M, Pizzo P, Steinberg TH, et al. Characterization of the cytotoxic effect of extracellular ATP in J774 mouse macrophages. Biochem J. 1992;288:897–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Mackenzie AB, Young MT, Adinolfi E, et al. Pseudoapoptosis induced by brief activation of ATP-gated P2X7 receptors. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:33968–33976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Tian T, Wang Y, Wang H, et al. Visualizing of the cellular uptake and intracellular trafficking of exosomes by live-cell microscopy. J Cell Biochem. 2010;111:488–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Wen SW, Sceneay J, Lima LG, et al. The biodistribution and immune suppressive effects of breast cancer–derived exosomes. Cancer Res. 2016;76:6816–6827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Grange C, Tapparo M, Bruno S, et al. Biodistribution of mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles in a model of acute kidney injury monitored by optical imaging. Int J Mol Med. 2014;33:1055–1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Tacke F, Ginhoux F, Jakubzick C, et al. Immature monocytes acquire antigens from other cells in the bone marrow and present them to T cells after maturing in the periphery. J Exp Med. 2006;203:583–597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Sunderkotter C, Nikolic T, Dillon MJ, et al. Subpopulations of mouse blood monocytes differ in maturation stage and inflammatory response. J Immunol. 2004;172:4410–4417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].van Rooijen N, Kors N, Kraal G. Macrophage subset repopulation in the spleen: differential kinetics after liposome-mediated elimination. J Leukoc Biol. 1989;45:97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Yamaguchi K, Yu Z, Kumamoto H, et al. Involvement of Kupffer cells in lipopolysaccharide-induced rapid accumulation of platelets in the liver and the ensuing anaphylaxis-like shock in mice. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1762:269–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Tatham KC, O’Dea KP, Romano R, et al. Intravascular donor monocytes play a central role in lung transplant ischaemia-reperfusion injury. Thorax. 2018;73:350–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Wakabayashi K, Wilson MR, Tatham KC, et al. Volutrauma, but not atelectrauma, induces systemic cytokine production by lung-marginated monocytes. Crit Care Med. 2014;42:e49–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].O’Dea KP, Dokpesi JO, Tatham KC, et al. Regulation of monocyte subset proinflammatory responses within the lung microvasculature by the p38 MAPK/MK2 pathway. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011;301:L812–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Patel BV, Tatham KC, Wilson MR, et al. In vivo compartmental analysis of leukocytes in mouse lungs. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2015;309:L639–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Borges da Silva H, Fonseca R, Pereira RM, et al. Splenic macrophage subsets and their function during blood-borne infections. Front Immunol. 2015;6:480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Thery C, Witwer KW, Aikawa E, et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): a position statement of the international society for extracellular vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. J Extracell Vesicles. 2018;7:1535750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Raposo G, Stoorvogel W. Extracellular vesicles: exosomes, microvesicles, and friends. J Cell Biol. 2013;200:373–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Bobrie A, Colombo M, Krumeich S, et al. Diverse subpopulations of vesicles secreted by different intracellular mechanisms are present in exosome preparations obtained by differential ultracentrifugation. J Extracell Vesicles. 2012;1:10.3402/jev.v1i0.18397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Crescitelli R, Lasser C, Szabo TG, et al. Distinct rna profiles in subpopulations of extracellular vesicles: apoptotic bodies, microvesicles and exosomes. J Extracell Vesicles. 2013;2:20677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Morel O, Jesel L, Freyssinet JM, et al. Cellular mechanisms underlying the formation of circulating microparticles. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:15–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Skotland T, Sandvig K, Llorente A. Lipids in exosomes: current knowledge and the way forward. Prog Lipid Res. 2017;66:30–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Gould SJ, Raposo G. As we wait: coping with an imperfect nomenclature for extracellular vesicles. J Extracell Vesicles. 2013;2:20389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Lee KD, Nir S, Papahadjopoulos D. Quantitative analysis of liposome-cell interactions in vitro: rate constants of binding and endocytosis with suspension and adherent J774 cells and human monocytes. Biochemistry. 1993;32:889–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Hanayama R, Tanaka M, Miwa K, et al. Identification of a factor that links apoptotic cells to phagocytes. Nature. 2002;417:182–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Koppler B, Cohen C, Schlondorff D, et al. Differential mechanisms of microparticle transfer to B cells and monocytes: anti-inflammatory properties of microparticles. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:648–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Dasgupta SK, Le A, Chavakis T, et al. Developmental endothelial locus-1 (del-1) mediates clearance of platelet microparticles by the endothelium. Circulation. 2012;125:1664–1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Ayers L, Nieuwland R, Kohler M, et al. Dynamic microvesicle release and clearance within the cardiovascular system: triggers and mechanisms. Clin Sci (Lond). 2015;129:915–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Herrmann IK, Bertazzo S, O’Callaghan DJ, et al. Differentiating sepsis from non-infectious systemic inflammation based on microvesicle-bacteria aggregation. Nanoscale. 2015;7:13511–13520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Imai T, Takahashi Y, Nishikawa M, et al. Macrophage-dependent clearance of systemically administered B16BL6-derived exosomes from the blood circulation in mice. J Extracell Vesicles. 2015;4:26238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Glaros TG, Chang S, Gilliam EA, et al. Causes and consequences of low grade endotoxemia and inflammatory diseases. Front Biosci (Schol Ed). 2013;5:754–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Geng S, Chen K, Yuan R, et al. The persistence of low-grade inflammatory monocytes contributes to aggravated atherosclerosis. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Benacerraf B, Sebestyen MM. Effect of bacterial endotoxins on the reticuloendothelial system. Federation Proc. 1957;16:860–867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Gospos C, Freudenberg N, Bank A, et al. Effect of endotoxin-induced shock on the reticuloendothelial system. Phagocytic activity and DNA-synthesis of reticuloendothelial cells following endotoxin treatment. Beitr Pathol. 1977;161:100–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Rahman S, Cichon M, Hoppensteadt D, et al. Upregulation of microparticles in DIC and its impact on inflammatory processes. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2011;17:E202–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Shet AS, Aras O, Gupta K, et al. Sickle blood contains tissue factor-positive microparticles derived from endothelial cells and monocytes. Blood. 2003;102:2678–2683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Rautou PE, Mackman N. Microvesicles as risk markers for venous thrombosis. Expert Rev Hematol. 2013;6:91–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Zecher D, Cumpelik A, Schifferli JA. Erythrocyte-derived microvesicles amplify systemic inflammation by thrombin-dependent activation of complement. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34:313–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Buesing KL, Densmore JC, Kaul S, et al. Endothelial microparticles induce inflammation in acute lung injury. J Surg Res. 2011;166:32–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Wilson MR, O’Dea KP, Zhang D, et al. Role of lung-marginated monocytes in an in vivo mouse model of ventilator-induced lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:914–922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Getts DR, Terry RL, Getts MT, et al. Therapeutic inflammatory monocyte modulation using immune-modifying microparticles. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:219ra217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Kobzik L, Swirski FK. Marcoing monocytes for elimination. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:219fs214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Murciano JC, Muro S, Koniaris L, et al. ICAM-directed vascular immunotargeting of antithrombotic agents to the endothelial luminal surface. Blood. 2003;101:3977–3984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Papademetriou I, Tsinas Z, Hsu J, et al. Combination-targeting to multiple endothelial cell adhesion molecules modulates binding, endocytosis, and in vivo biodistribution of drug nanocarriers and their therapeutic cargoes. J Control Release. 2014;188:87–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Falati S, Liu Q, Gross P, et al. Accumulation of tissue factor into developing thrombi in vivo is dependent upon microparticle P-selectin glycoprotein ligand 1 and platelet P-selectin. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1585–1598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Wiklander OP, Nordin JZ, O’Loughlin A, et al. Extracellular vesicle in vivo biodistribution is determined by cell source, route of administration and targeting. J Extracell Vesicles. 2015;4:26316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Chandler WL. Microparticle counts in platelet-rich and platelet-free plasma, effect of centrifugation and sample-processing protocols. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2013;24:125–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Kowal J, Arras G, Colombo M, et al. Proteomic comparison defines novel markers to characterize heterogeneous populations of extracellular vesicle subtypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:E968–977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Gyorgy B, Paloczi K, Kovacs A, et al. Improved circulating microparticle analysis in acid-citrate dextrose (ACD) anticoagulant tube. Thromb Res. 2014;133:285–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.