Abstract

Objective

To understand doctors’ attitude to and awareness of AYUSH therapies for the treatment of diabetes mellitus (DM).

Methods

This qualitative study, using a usage-and-attitude survey, was conducted in secondary centers across Mumbai, India. The study surveyed 77 physicians, including those specializing in diabetes.

Results

The majority of doctors were aware of Ayurveda (69%) and Homeopathy (52%). Some doctors were aware of Unani (34%) and Siddha (32%). Most doctors (60%) thought that Ayurveda was effective in some way. Almost all doctors (97%) thought that allopathic medicine was effective for DM. The majority of doctors (68%) had not recommended AYUSH therapies as an adjunct to modern medicines. Approximately half of the doctors (52%) believed that AYUSH therapies posed a safety concern for patients and 46% thought that AYUSH therapies could not be used to manage any form of DM. A large group of doctors thought that the main barrier preventing AYUSH therapies from being integrated into current allopathic management of DM was the lack of strong scientific evidence and clinical trials.

Conclusion

The majority of doctors are aware to some degree of Ayurveda and homeopathic forms of treatment. The majority believe that AYUSH therapies pose a safety concern for patients and have no role in treatment for any form of DM. The most common barrier preventing AYUSH therapies from becoming a mainstream treatment option for DM is the lack of scientific evidence. From this sample, it seems that greater efforts are required to conduct research into the efficacy and safety of AYUSH therapies to ensure that doctors are able to provide holistic care for patients with DM.

Keywords: diabetes mellitus, complementary medicine, public health, governmental policy, patient care

Background

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a disorder characterized by insulin deficiency, increased glycemic levels and insulin resistance. DM has reached pandemic proportions and has become a major health concern in India. Epidemiological studies have shown an increase in the prevalence of DM in both city and rural populations. The diabetes prevalence increased from 5% in 1985 to 18.6% in 2006 in cities, and from 2.2% in 1989 to 9.2% in 2006 in rural areas.1 It is estimated that currently more than 30 million individuals are living with either undiagnosed or untreated DM, thus increasing the risk of developing complications and premature mortality. The mainstay of treatment for type 1 DM involves insulin therapy, whereas a combination of pharmacological therapies and changes to lifestyle and diet are advocated for managing type 2 DM. The economic burden of diabetic care on families in developing countries, including India, is rising rapidly. Treatment costs for patients in India are increased with the duration of diabetes, presence of complications, hospitalization, surgery, insulin therapy and urban setting.

India has a population of more than a billion people and is home to some of the most diverse cultural and religious groups in the world. Owing to wide disparities in wealth, education and access to healthcare, some of these cultural groups still utilize alternate forms of medicine. The Ayurveda, Unani, Siddha, Homeopathy (AYUSH) therapies are one of the oldest forms of alternate medicines in India, originating approximately 2000 years ago. The Indian system of medicine still recognizes AYUSH as a form of medical treatment.2 The Government of India has a dedicated Ministry, established in 2014, to ensure the optimal development and propagation of the AYUSH system of healthcare.

Ayurveda (the science of life) incorporates all aspects of life, whether physical, psychological, spiritual or social. In Ayurveda, DM is termed Madhumeha (honey urine), and advocates the use of a variety of herbal preparations, such as decoctions, juices and powders, for treatment. All of these are of plant origin and have not yet seen reports of any adverse effects in therapeutic doses. However, they may contain animal and inorganic products.3 The foundation of the Unani system in India stems from the Perso-Arabic system of health. Unani bases its theory of illness on the imbalances between certain fluids (e.g. bile and blood) in the human body. Siddha is currently practiced mainly in the southern regions of India and focuses on maintaining equilibrium between the environment, climatic conditions, physical activities and stress, to ensure good health. Finally, Homeopathy is an increasingly used system that is known to be practiced globally. It is estimated that about 10% of the Indian population depend solely on Homoeopathy for their healthcare needs, and it is considered the second most popular system of medicine in the country.4 Its strength lies in its evident effectiveness, as it takes a holistic approach towards the sick individual through the promotion of inner balance at the mental, emotional, spiritual and physical levels.

As the incidence of DM is rapidly increasing throughout India, might the AYUSH therapies play a role in controlling this epidemic? Could AYUSH therapies be used as an adjunct alongside modern medicine to provide psychological support to patients and increase adherence to modern medicine? In this study, we aim to explore how doctors in India’s largest city, Mumbai, perceive the use of AYUSH therapies for treating DM, and whether they advocate them to their patients and believe that this form of treatment has any place alongside modern medicine.

Methods

Patient and Public Involvement

This research was inspired by the large use of AYUSH therapies among the Indian population. No patients were involved in any phases of this study since we wanted solely to attempt to understand the perception of allopathic doctors. The results of this study will be emailed to the doctors who kindly participated in the research.

Participants

A total of 77 doctors were surveyed, which included those with only a degree in Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS) (n=31), those with a further postgraduate degree in Doctor of Medicine (MD) (n=37) and those with further training and specializing in diabetes (n=9). These physicians worked across 18 different centers in suburban and greater Mumbai.

Procedure

A snowball sampling method was used and participants were approached personally at their clinic. No prior relationship was established between the doctors and research group, and the participants had no knowledge of the interviewers’ background. All participants were made aware that the purpose of this survey was to understand their awareness and perception of the topic, and that at no point any data would be collected or presented that would reveal any of their identities. Surveys were therefore only conducted if the participants gave their consent.

A pilot questionnaire was tested to assess its coherence and guidance was provided to the doctors to allow them to complete the questionnaire without confusion. Students based in India conducted the interview at the doctors’ clinics for 30 min. No other individuals except for the interviewer and the doctor were present during the process. The survey was not recorded in either audio or visual format. Moreover, repeat interviews were not carried out.

Each doctor was asked a fixed set of questions and a questionnaire was filled in. All doctors were asked to validate their response by providing their signature at the end of the physical questionnaire.

The questionnaire used a Likert scale to record the following elements:

Awareness of the different systems of AYUSH therapies

Perception of the effectiveness of the different systems of AYUSH therapies

Attitudes towards using AYUSH therapies as an adjunct to modern medicine

Attitudes towards the existing evidence for AYUSH therapies

Opinion on the main factor preventing AYUSH therapies from becoming a primary treatment option for DM.

For further analysis and comparison, each statement on the Likert scale was assigned a numerical value ranging from 1 to 5.

Results

Awareness of the Different Systems of AYUSH Therapies

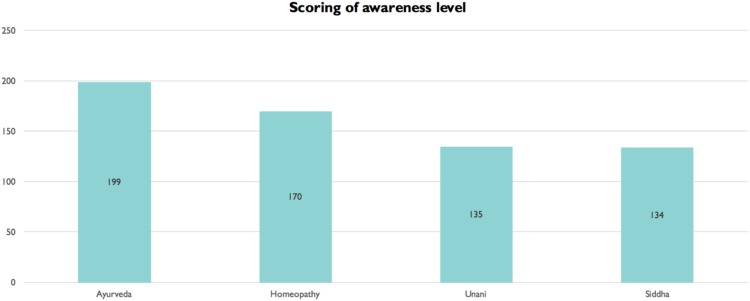

In total, 53 doctors (69%) were slightly to extremely aware of Ayurveda, with the remainder being not at all aware; 25 doctors were slightly to extremely aware of Siddha (32%), with the rest (68%) being not at all aware; 26 doctors (34%) were slightly to extremely aware of Unani, with the others (66%) being not at all aware; and finally, 40 doctors (52%) were slightly to extremely aware of Homeopathy, with the remainder (48%) being not at all aware. Table 1 shows the full breakdown of awareness for each system. Each of the options, “Not at all aware”, “Slightly aware”, “Somewhat aware”, “Moderately aware” and “Extremely aware”, was assigned a numerical score of 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5, respectively, and scores were subsequently tallied and compared. Out of a maximum score of 385, the scores for each component were: Ayurveda199, Siddha 130, Unani 135 and Homeopathy 170 (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Results for Awareness of Different Systems

| Absolute Frequency (Total %) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ayurveda | Siddha | Unani | Homeopathy | |

| Not at all aware | 24 (31.2) | 52 (67.5) | 51 (66.2) | 37 (48.0) |

| Slightly aware | 14 (18.2) | 7 (9.1) | 7 (9.1) | 10 (13.0) |

| Somewhat aware | 13 (16.9) | 6 (7.8) | 8 (10.4) | 11 (14.3) |

| Moderately aware | 22 (28.6) | 10 (13) | 9 (11.7) | 15 (19.5) |

| Extremely aware | 4 (5.2) | 2 (2.6) | 2 (2.6) | 4 (5.2) |

| Total | 77 (100) | 77 (100) | 77 (100) | 77 (100) |

Figure 1.

Doctors’ awareness levels regarding AYUSH therapies for DM.

Perception of the Effectiveness of the Different Systems of AYUSH Therapies

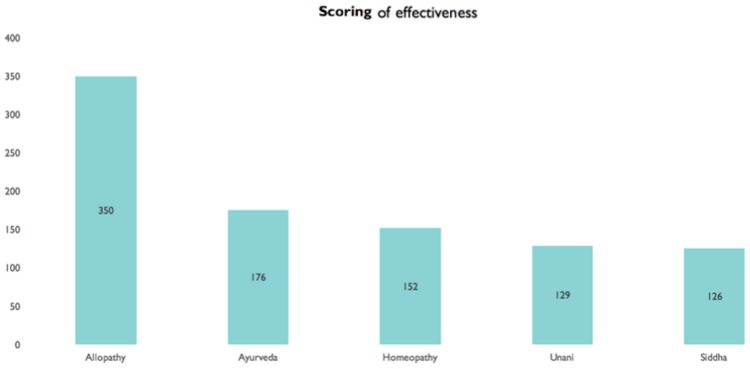

In total, 46 doctors (60%) perceived Ayurveda to be slightly to extremely effective, with the remainder (44%) believing it to be not at all effective; 22 doctors (29%) thought Siddha was slightly to extremely effective, with the rest (71%) thinking that it was not at all effective; 23 doctors (30%) believed Unani to be slightly to extremely effective, with the others (70%) believing it to be not at all effective; 38 doctors (41%) perceived Homeopathy to be slightly to extremely effective, with the rest (51%) believing it to be not at all effective. Finally, an additional option of “allopathic medicine” was given to compare against AYUSH therapies, and 75 doctors (97%) thought that allopathic medicine was slightly to extremely effective and two (3%) thought that it was not at all effective. Table 2 shows the breakdown of doctors’ perceptions for each component. Each of the options, “Not at all effective”, “Slightly effective”, “Somewhat effective”, “Moderately effective” and “Extremely effective”, was assigned a numerical scores of 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5, respectively, and scores were subsequently tallied and compared. Out of a maximum score of 385, the score for each component were: Ayurveda 176, Siddha 126, Unani 120, Homeopathy 152 and allopathic medicine 350 (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Results for Doctors’ Perception Regarding the Effectiveness of Different Systems

| Absolute Frequency (Total %) | Allopathic Medicine | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ayurveda | Siddha | Unani | Homeopathy | ||

| Not at all effective | 31 (40.3) | 55 (71.4) | 54 (70.1) | 39 (50.6) | 2 (2.6) |

| Slightly effective | 13 (16.9) | 5 (6.5) | 5 (6.5) | 13 (16.9) | 1 (1.3) |

| Somewhat effective | 16 (20.8) | 9 (11.7) | 9 (11.7) | 14 (18.2) | 4 (5.2) |

| Moderately effective | 14 (18.2) | 6 (7.8) | 7 (9.1) | 10 (13) | 16 (20.8) |

| Extremely effective | 3 (3.9) | 2 (2.6) | 2 (2.6) | 1 (1.3) | 54 (70.1) |

| Total | 77 (100) | 77 (100) | 77 (100) | 77 (100) | 77 (100) |

Figure 2.

Doctors’ perception of effectiveness of the different AYUSH therapies and allopathic medicine for DM.

Attitudes Towards Using AYUSH Therapies as an Adjunct to Modern Medicine

In total, 52 doctors had never recommended AYUSH therapies as an adjunct to allopathic medication. Of these doctors, 27 claimed to base their choice on scientific decisions and 25 did not claim that their decision was evidence based. Table 3 shows the breakdown of doctors’ recommendations of AYUSH therapies.

Table 3.

Results Demonstrating the Number of Doctors Who Have Used AYUSH Therapies as an Adjunct to Modern Medicine and Whether Their Decision Was Evidence Based

| Recommended AYUSH Therapies as an Adjuvant to Allopathic Medicine | Decision Based on Scientific Evidence | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||

| Never | 27 | 25 | 52 |

| Almost never | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Occasionally | 17 | 2 | 19 |

| Always | 3 | 0 | 3 |

Attitudes Towards the Existing Evidence for AYUSH Therapies

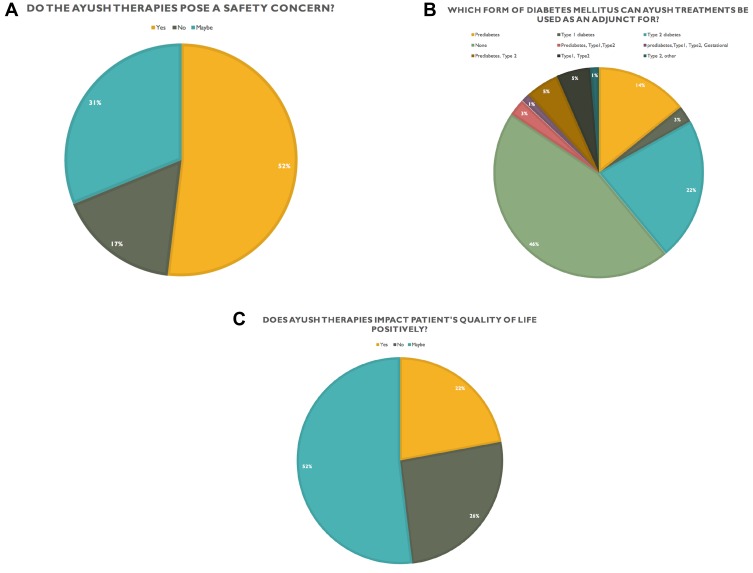

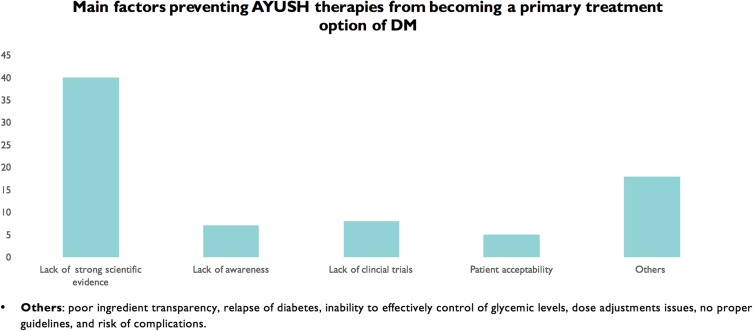

When doctors were asked whether AYUSH therapies posed a safety concern, 52% answered “yes”, 17% answered “no”, and 31% were unsure and opted for “maybe” (Figure 3A). When doctors were asked which form of DM AYUSH therapies could be used for, the majority (46%) opted for “none”, and the next largest group (22%) chose type 2 DM. Figure 3B shows the full breakdown of doctors’ thoughts on AYUSH therapy for each form of DM. Doctors were further asked whether AYUSH therapies positively impacted a patient’s quality of life: 22% answered “yes“, 26% said “no“ and the remaining 52% were unsure and opted for “maybe” (Figure 3C). Finally, doctors were asked what, in their opinion, was the main factor preventing AYUSH therapies from becoming the main treatment option for DM. The majority cited a lack of strong scientific evidence. Other popular responses included lack of awareness, lack of clinical trials and patient acceptability (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

(A) Attitudes towards AYUSH therapies and safety. (B) Attitudes towards use of AYUSH therapies for different forms of diabetes mellitus. (C) Attitudes towards use of AYUSH therapies and their impact on quality of life.

Figure 4.

Attitudes towards main factors preventing AYUSH therapies from becoming mainstream treatment options.

Discussion

India is home to a diverse population with differing cultural and religious beliefs. These cultures often have their own ideologies with regard to managing diseases. In this study, we aimed to explore whether allopathic doctors are aware of these alternate forms of medicine, primarily AYUSH therapies, and whether they believe that this form of treatment has any place in current practice for the treatment of DM. Our study found that doctors are aware of the different systems of AYUSH therapies, with the majority being more aware of Ayurveda and Homeopathy. However, doctors still believe that allopathic medication is far more effective than AYUSH therapies. More than 50% of doctors had never used AYUSH therapies alongside allopathic treatment for DM and 46% thought that AYUSH therapies cannot be used for any form of DM. The main factor that doctors believed is preventing AYUSH therapies from becoming a mainstream management option is a lack of scientific evidence. However, 22% of doctors thought that AYUSH therapies could have a positive impact on patients’ quality of life, with a further 52% unsure of their value in patient care.

One strength of our study was the inclusion of doctors with varying degrees of experience in clinical practice. This allowed us to obtain results from different generations of doctors, with varying knowledge of DM. Moreover, the doctors worked across 18 different centers in suburban and greater Mumbai and therefore represented all income groups. Conversely, India has over 4000 cities, and our study was focused on one city and interviewed 77 doctors. Larger scale studies in the other major cities in India could provide further details on whether AYUSH therapies could be effectively incorporated into current allopathic practice and for the management of DM. A study in New Delhi by Singhal and Roy5 investigated the awareness of and views on integrating AYUSH therapies into modern medicine from 500 allopathic doctors and 150 interns. The authors reported that 63% of participants thought that AYUSH therapies were effective and 44% had recommended Homeopathy to their patients. These results are in contrast to our study, where the majority had never recommended any form of AYUSH systems, although it must be noted that the previous study did not specifically look into incorporating AYUSH in the management of DM. Moreover, our study may have been biased based on the fact that we only included allopathic doctors. Further analysis of other healthcare professionals and those practicing non-allopathic medicine could yield more diverse results and allow us to factor in other aspects of AYUSH therapies that may not have been raised during this study. Indeed, Ahmad et al6 analyzed the perception of AYUSH therapies in 428 pharmacy students. The group reported that pharmacy students held a favorable attitude and beliefs about AYUSH use. Moreover, interviewing patients in India regarding the effectiveness of AYUSH therapies could provide a more patient-centered form of research into these systems of medicine. In our study, 26% of doctors thought that AYUSH therapies did not positively impact patients’ quality of life. A study to understand the perception of AYUSH therapies in 259 patients with DM by Ojha et al7 found that 43.6% of patients thought that AYUSH therapies were effective in treating DM. Further analysis of perceptions in different healthcare professionals and patients could open new avenues to incorporate AYUSH therapies into current practice and provide holistic care to patients in India.

Our study showed that 30 doctors (39%) had either “Never” or “Almost never” prescribed AYUSH therapies based on scientific evidence. Furthermore, the most popular reason preventing AYUSH therapies being incorporated into modern practice was “lack of strong scientific evidence”, with some doctors also giving “lack of clinical trials” as a reason. These results are most surprising to us because there is emerging evidence to suggest that AYUSH therapies may help to control glycemic parameters. Studies carried out on streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats showed that an aqueous extract of Aegle marmelos (considered “holy fruit trees” by Hindus) had antiglycemic properties. Oral administration of this compound was shown to decrease fasting blood glucose levels by 61%.8 Moreover, in a double-blinded controlled trial it was found that Coccinia indica (advocated by Ayurveda) improved glucose tolerance in patients with type 2 DM, as 10 out of 16 patients showed significantly (p<0.001) improved blood glucose levels following its administration.9 Animal studies have also suggested that this product may act in a similar manner to insulin.10 The plant Tinospora cordifolia (heart-leaved moonseed, used in the tropical regions of India) has been shown to increase insulin secretion, thus bringing down blood glucose levels. It has been demonstrated that aqueous and alcoholic extracts of this plant seemed to increase glucose tolerance in albino rats.11 Furthermore, in Ayurveda, Curcuma longa (ivy gourd) is advocated extensively for treatment of DM, and it was reported that C. longa had hypoglycemic properties in diabetic rats.12

Together, these studies show that there have been several evidence-backed studies into AYUSH therapies for managing DM. Perhaps the lack of “strong” scientific evidence stated by doctors refers to the relatively few human trials into these compounds. Moreover, the fact that the exact side effects in these studies remain unknown may make doctors more apprehensive about recommending them to their patients.

Our study has several implications for stakeholders, including the government, doctors, research institutions and patients. First, the fact that doctors in our study believed that there was a lack of strong scientific evidence for the use of AYUSH therapies implies that more effort is required to conduct studies and publicize their results. This would require increased funding and greater motivation by research institutions to conduct larger scale trials on human volunteers to test the efficacy and safety of the current AYUSH products. Second, 67% of doctors in our study were completely unware of the Siddha form of treatment and a further 62% were oblivious to Unani. This implies that the ministry responsible for propagation of AYUSH systems of healthcare needs to work in conjunction with researchers to provide transparent and up-to-date results of recent breakthroughs in the field. They must further ensure that their strategy to increase the awareness of all components of AYUSH therapies reaches doctors nationwide. Third, our study showed several disparities compared to other trials in other major cities in India regarding the awareness and effectiveness of AYUSH therapies. We would therefore suggest the establishment of a society for doctors based on each specialty, including diabetologists, to ensure that everyone is receiving the same information regarding research into AYUSH therapies in their field. Finally, it must also be remembered that good health is not merely the absence of disease but a “state of complete physical, mental, and social well being.”13 Consequently, even if the AYUSH therapies are not found to be effective in reducing blood glucose levels in humans, studies must continue to investigate their potential side effects. Indeed, it may be possible that AYUSH therapies provide a form of psychological and mental support for patients, and with effective communication by doctors, adherence to allopathic medication can be maintained. Several studies have reported that compliance with antidiabetic medication in patients in India is poor.14,15

AYUSH systems of medicine have been used in India for over 2000 years and several cultural groups still utilize them today. However, research into these systems largely remains in the preclinical phase. From the physicians surveyed in this study, it seems that most are unaware of what these systems advocate for the treatment of different forms of diabetes. From this study, we may conclude that greater efforts are required to conduct research into the efficacy and safety of AYUSH therapies to ensure that doctors are able to provide holistic care and correct information for patients with DM.

Funding Statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics and Data Sharing

Shobhaben Pratapbhai Patel School Of Pharmacy & Technology Management has reviewed the study, and since the research was based on a questionnaire and survey and no human subjects or patients were involved, the study does not require approval from the ethics committee.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to data analysis, drafting or revising the article, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Ramachandran A, Snehalatha C, Latha E, Vijay V, Viswanathan M. Rising prevalence of NIDDM in an urban population in India. Diabetologia. 1997;40(2):232–237. doi: 10.1007/s001250050668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Department of Ayurveda, Yoga and Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha and Homeopathy (AYUSH). Ministry of health and family welfare government of India. Available from: http://www.indianmedicine.nic.in/. Accessed December30, 2019.

- 3.Ahmad F, Khalid P, Khan MM, Rastogi AK, Kidwai JR. Insulin like activity in (−) epicatechin. Acta Diabetol Lat. 1989;26(4):291–300. doi: 10.1007/BF02624640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prasad R. Homoeopathy booming in India. Lancet. 2007;370(9600):1679–1680. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61709-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singhal S, Roy V. Awareness, practice and views about integrating AYUSH in allopathic curriculum of allopathic doctors and interns in a tertiary care teaching hospital in New Delhi, India. J Integr Med. 2018;16(2):113–119. doi: 10.1016/j.joim.2018.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahmad A, Khan MU, Kumar BD, Kumar GS, Rodriguez SP, Patel I. Beliefs, attitudes and self-use of Ayurveda, Yoga and Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha, and Homeopathy medicines among senior pharmacy students: an exploratory insight from Andhra Pradesh, India. Pharmacognosy Res. 2015;7(4):302–308. doi: 10.4103/0974-8490.158438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ojha A, Trivedi R, Ugaonkar S, Desai M, Ramesh S, Sahu P. Awareness and attitude of patients towards AYUSH therapies for diabetes SVKM’S NMIMS. Int J Inf Res Rev. 2019;6(3):6180–6184. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahmad F, Khalid P, Khan MM, Chaubey M, Rastogi AK, Kidwai JR. Hypoglycemic activity of Pterocarpus marsupium wood. J Ethnopharmacol. 1991;35(1):71–75. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(91)90134-Y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khan AKA, Akhtar S, Mahtab H. Coccinia indica in the treatment of patients with diabetes mellitus. Bangladesh Med Res Counc Bull. 1979;5(2):60–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahmed I, Adeghate E, Sharma AK, Pallot DJ, Singh J. Effects of Momordica charantia fruit juice on islet morphology in the pancreas of the streptozotocin-diabetic rat. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1998;40(3):145–151. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8227(98)00022-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ajabnoor MA, Tilmisany AK. Effect of Trigonella foenum graceum on blood glucose levels in normal and alloxan-diabetic mice. J Ethnopharmacol. 1988;22(1):45–49. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(88)90229-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bever BO. Oral hypoglycaemic plants in West Africa. J Ethnopharmacol. 1980;2(2):119–127. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(80)90005-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organisation. WHO definition of health. Available from: http://www.who.int/about/definition/en/. Accessed December30, 2019.

- 14.Mukherjee S, Sharmasarkar B, Das KK, Bhattacharyya A, Deb A. Compliance to anti-diabetic drugs: observations from the diabetic clinic of a medical college in kolkata, India. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7(4):661–665. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2013/5352.2876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar KMP, Chawla M, Sanghvi A, et al. Adherence, satisfaction, and experience with metformin 500 mg prolonged release formulation in Indian patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a postmarketing observational study. Int J Gen Med. 2019;12:147–159. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S179622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Department of Ayurveda, Yoga and Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha and Homeopathy (AYUSH). Ministry of health and family welfare government of India. Available from: http://www.indianmedicine.nic.in/. Accessed December30, 2019.