Abstract

Chondrichthyans are a vulnerable group that has been overexploited for almost half a century in the Mediterranean. Since in this area most chondrichthyans are rarely incorporated into international statistics, the impact of fishing on their populations is difficult to assess. Here, we evaluate temporal trends in order to understand the recent history of chondrichthyans in the western Mediterranean. Fishery-independent data were obtained from scientific surveys carried out from 1994 to 2015 in three geographical sub-areas. Our results reflect fairly stable populations in terms of diversity, with some increase in density and standardized biomass of some species dwelling on the continental shelf, and even for some species dwelling on the slope. In contrast, decreasing trends were observed in some deep-water species. This can be explained by the reduction of the trawling effort on the continental shelf over the last few decades, and the shift of the fleet towards deep waters, along with the greater resilience displayed by some species. Furthermore, a decreasing trend in maturity of Scyliorhinus canicula was detected, suggesting an evolutionary response to overfishing. These results improve scientific knowledge for developing true adaptive management in the Mediterranean that will implement measures to strengthen or initiate the recovery of chondrichthyans.

Subject terms: Ocean sciences, Marine biology

Introduction

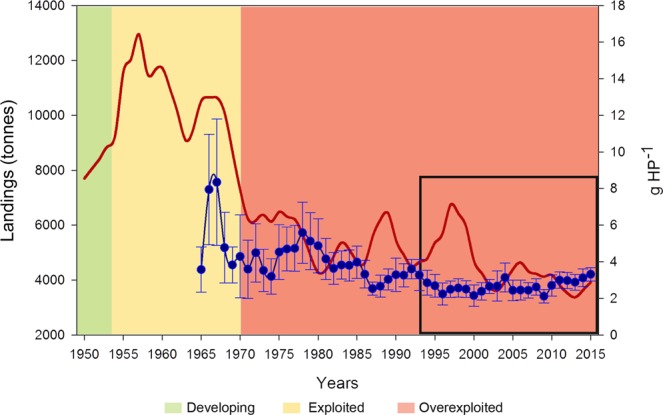

Marine ecosystems are under pressure from overfishing, habitat degradation and climate change which have altered the populations of most of their species1,2, especially chondrichthyans (sharks, rays and chimaeras), due to their low population resilience3–5. Global chondrichthyan landings, reported to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), increased over 200% from 1950 to the peak year in 2003 and subsequently dropped almost 15% by 20116. In the Mediterranean, the temporal evolution of chondrichthyan landings has gone through three stages: a development phase at the beginning of the 1950s; followed by intense fishing pressure from the mid 1950s to 1970, corresponding to the exploited phase; and a decreasing trend from 1970 to recent years, indicating an overexploited status (Fig. 1), such as has been reported for most demersal and pelagic bony fish and shellfish stocks a decade later during the eighties7–10. This earlier overexploitation in chondrichthyans is to be expected due to their low resilience. Studies of long time series of chondrichthyan catches conducted in several areas of the Mediterranean have also shown decreasing trends over the last few decades11–14. Furthermore, there is evidence that Mediterranean chondrichthyans have declined in diversity. At present, several species such as Dipturus batis (recently split into two cryptic species, D. cf. flossada and D. cf. intermedia15, Pristis spp. and Squatina spp.) are considered to be locally extinct16–18. In fact, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has recently revealed the Mediterranean as a key hotspot of extinction risk for chondrichthyans, where more than half of the species assessed (39 out of 73) are considered to be threatened: 20 critically endangered, 11 endangered and 8 vulnerable19.

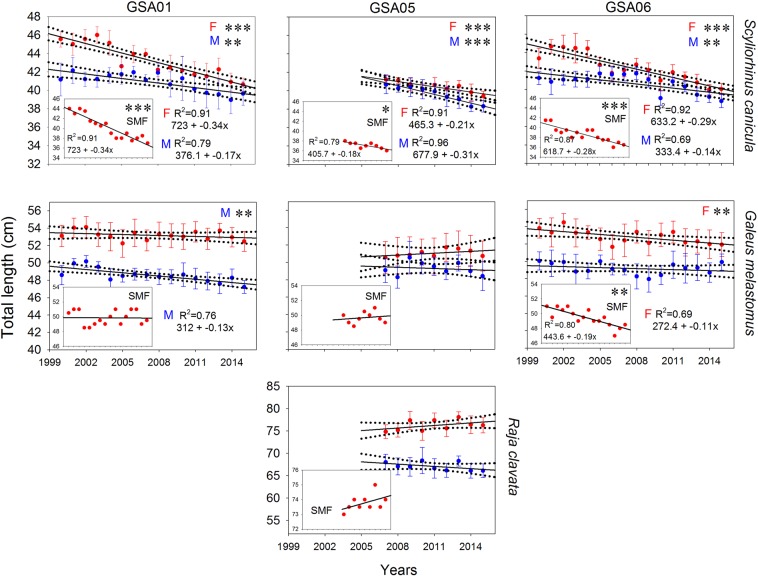

Figure 1.

Historical series of landings of chondrichthyans (red line) in the Mediterranean and Black Sea according to FAO statistics85, and mean annual landings per unit effort (blue line; with standard error bars) of elasmobranchs in the Balearic Islands24. Colours correspond to different stages of the catches identified according to the algorithm for catch-based stock status86: green is “developing”, yellow is “exploited” and red is “overexploited”. The black square indicates our study period.

In the western Mediterranean, most chondrichthyans are bottom dwelling species inhabiting demersal ecosystems on the continental shelf and slope, which makes them especially vulnerable to trawling18, the most important fishery in the western Mediterranean in terms of fishing capacity of both the fleet and catches20. This fishery operates over a wide bathymetric range (50–800 m), exploiting different communities21 and thus involving a large number of species in the catches, which include bony fishes, decapod crustaceans, cephalopods and other invertebrates, as well as chondrichthyans, which represent an important fraction of by-catch and discards22–24.

Ecosystem-based assessment and management of fisheries requires moving from the conventional single-species approach to entire exploited communities25. This is particularly important in the bottom trawling taking place along the western Mediterranean, with a marked multi-species character, and where by-catch species can show comparable or even higher levels of overexploitation than the target ones26, or are especially vulnerable to fishing exploitation, such as chondrichthyans27. However, a lack of accurate fishing landing data concerning chondrichthyans, and a paucity of biological information has been a drawback for the assessment of their populations28 and the Mediterranean is no exception. In this sense, fishery-independent data from scientific surveys can provide valuable information on by-catch species (e.g. abundance and biomass, sex and maturity, size composition) that is not commonly collected in fishery monitoring programs, which mainly focus on achieving data for assessing the most important target species.

Long-term trends of chondrichthyans have been studied in different areas of the Mediterranean, at either community8,13,16,24,29 or population level30–33. However, none of these studies have evaluated temporal changes over a broad area, combining community and species level. Our aim was to use fishery-indepent data from scientific surveys over the last few decades, to evaluate spatio-temporal patterns and trends in diversity, density standardized biomass, size and maturity of demersal chondricthyans in the western Mediterranean.

Results

A total of 34 chondrichthyan species belonging to 13 families were caught throughout the western Mediterranean over the last two decades, 27, 26 and 19 species of which were caught in GSA01, GSA05 and GSA06, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Chondrichthyans captured in each geographical sub-area (GSA) considered by the General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean throughout the study area (1: GSA01 or Northern Alboran Sea; 5: GSA05 or Balearic Islands; 6: GSA06 or Northern Spain) during the MEDITS surveys conducted along the western Mediterranean during the periods 1994–2015 for GSA01 and GSA06 and 2001–2015 for GSA05.

| Family | Species | D (m) | %Y | %D | N | B | IUCN | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 5 | 6 | 2007 | 2016 | ||

| Chimaeridae | Chimaera monstrosa | 325–831 | 440–654 | 440–856 | 95.4 | 53.3 | 50 | 55.3 | 5.6 | 4.2 | 1871 | 29 | 25 | 1407 | 2.25 | 1.95 | NT | NT |

| Scyliorhinidae | Galeus melastomus | 301–831 | 145–755 | 232–788 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 94.8 | 93.5 | 83.6 | 84127 | 45050 | 17340 | 17253 | 1539 | 1960 | LC | LC |

| Galeus atlanticus | 324–821 | — | — | 93.7 | — | — | 41.7 | — | — | 3238 | — | — | 1007 | — | — | NT | NT | |

| Scyliorhinus canicula | 40–664 | 38–626 | 42–661 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 73.4 | 95.5 | 51.7 | 9634 | 82441 | 27945 | 1876 | 5701 | 3853 | LC | LC | |

| Triakidae | Galeorhinus galeus | 238–593 | — | — | 59.1 | — | — | 8.4 | — | — | 38 | — | — | 528 | — | — | VU | VU |

| Mustelus mustelus | 60 | 54–141 | — | 9.1 | 80 | — | <0.1 | 11.2 | — | 4 | 207 | — | 4.4 | 80.4 | — | EN | VU | |

| Mustelus asterias | — | 107 | — | — | 13.3 | — | — | — | — | — | 2 | — | — | 1.2 | — | EN | VU | |

| Hexanchidae | Heptranchias perlo | 428–556 | — | — | 9.1 | — | — | <0.1 | — | — | 2 | — | — | 8.3 | — | — | VU | DD |

| Centrophoridae | Centrophorus granulosus | 377–796 | 594–753 | — | 81.8 | 33.3 | — | 10.7 | 3.2 | — | 52 | 9 | — | 184 | 36.35 | — | VU | CR |

| Dalatiidae | Dalatias licha | 325–831 | 590–743 | 411–748 | 100 | 86.6 | 63.6 | 15.8 | 4.4 | 5.2 | 124 | 8 | 23 | 500 | 19.24 | 8.7 | DD | VU |

| Etmopteridae | Etmopterus spinax | 314–831 | 362–755 | 236–856 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 88.7 | 58 | 41.2 | 8546 | 882 | 983 | 874 | 59.57 | 61.24 | LC | LC |

| Oxynotidae | Oxynotus centrina | 87–812 | 98 | — | 68.2 | 6.6 | — | 0.23 | — | — | 30 | 2 | — | 88.35 | 0.25 | — | CR | CR |

| Squalidae | Squalus acanthias | 77 | 104–654 | 124–582 | 4.5 | 46.6 | 9.1 | — | 4.6 | 2.1 | 1 | 53 | 56 | 1.5 | 65.6 | 13.46 | EN | EN |

| Squalus blainvillei | — | 47–667 | 124–130 | — | 73.3 | 13.6 | — | 12.1 | 3.5 | — | 185 | 134 | — | 778 | 118.55 | EN | DD | |

| Dasyatidae | Dasyatis centroura | — | 58 | — | — | 6.6 | — | — | — | — | — | 1 | — | — | 4.4 | — | NT | VU |

| Dasyatis pastinaca | — | 39–98 | 54–79 | — | 100 | 13.6 | — | 47.3 | <0.1 | — | 364 | 5 | — | 169.5 | 22.29 | NT | VU | |

| Pteroplatytrygon violacea | 43–317 | — | — | 18.2 | — | — | <0.1 | — | — | 5 | — | — | 52.9 | — | — | NT | LC | |

| Myliobatidae | Mylibatis aquila | 44 | 39–144 | 73–81 | 4.5 | 80 | 13.6 | — | 29.2 | <0.1 | 2 | 200 | 8 | 0.61 | 322 | 24.32 | NT | VU |

| Pteromylaeus bovinus | — | 44–60 | — | — | 6.6 | — | — | <0.1 | — | — | 2 | — | — | 7.57 | — | EN | CR | |

| Rajidae | Dipturus nidarosiensis | 765–813 | — | — | 9.1 | — | — | <0.1 | — | — | 2 | — | — | 0.62 | — | — | NE | NE |

| Dipturus oxyrinchus | 357–769 | 134–699 | — | 9.1 | 100 | — | <0.1 | 32.3 | — | 2 | 509 | — | 9.82 | 315 | — | NT | NT | |

| Leucoraja circularis | 354–710 | 131–499 | 245 | 36.4 | 46.6 | 4.5 | <0.1 | 4.7 | — | 13 | 139 | 1 | 269.5 | 29 | 0.043 | EN | CR | |

| Leucoraja naevus | 60–565 | 52–540 | 82–320 | 81.8 | 100 | 59 | 17.2 | 40.9 | 3.5 | 287 | 969 | 94 | 39.28 | 236 | 38.92 | NT | NT | |

| Raja asterias | 40–180 | — | 40–255 | 81.8 | — | 95.5 | 2.4 | — | 10.2 | 90 | — | 270 | 114.47 | — | 138 | NT | NT | |

| Raja brachyura | — | 48–162 | — | — | 33.3 | — | — | 23.2 | — | — | 417 | — | — | 95.87 | — | DD | NT | |

| Raja clavata | 47–420 | 57–590 | 52–582 | 18.2 | 100 | 84.4 | 0.16 | 64.7 | 4.3 | 16 | 4994 | 289 | 11.06 | 2369 | 20.9 | NT | NT | |

| Raja miraletus | 81–207 | 40–174 | 85–225 | 9.1 | 100 | 50 | <0.1 | 38.9 | 1.2 | 3 | 2044 | 49 | 0.53 | 115.1 | 13.02 | LC | LC | |

| Raja montagui | 44–160 | — | 57–406 | 22.7 | 72.7 | 0.24 | 5.7 | 11 | 114 | 6.33 | 32.96 | LC | LC | |||||

| Raja polystigma | 70 | 48–424 | 85–316 | 4.5 | 94.7 | 31.8 | — | 33.1 | <0.1 | 1 | 1826 | 39 | 0.79 | 266.7 | 12.53 | NT | LC | |

| Raja radula | 40–53 | 40–97 | 124–211 | 9.1 | 100 | 13.6 | <0.1 | 35.2 | <0.1 | 3 | 664 | 9 | 1.98 | 257 | 2.22 | DD | EN | |

| Rostroraja alba | — | 56–251 | — | — | 40 | — | — | <0.1 | — | — | 13 | — | — | 71.2 | — | CR | EN | |

| Torpedinidae | Torpedo marmorata | 40–290 | 51–258 | 45–297 | 100 | 86.6 | 100 | 26.4 | 5.2 | 21.2 | 187 | 71 | 253 | 116.8 | 9.5 | 71 | LC | LC |

| Torpedo nobiliana | 170–777 | 368 | 144–431 | 81.8 | 6.6 | 22.7 | — | <0.1 | 56 | 1 | 14 | 61.2 | 0.22 | 13.17 | DD | LC | ||

| Torpedo torpedo | 40 | — | — | 13.6 | — | — | — | — | — | 11 | — | — | 6.92 | — | — | LC | LC | |

D: depth range; %Y: average percentage of years in which the species were caught during the study period; %D: percentage of appearance within the depth range in which the species was caught for all years; N: total number of specimens caught; B: total weight of catches. IUCN indicates the regional status of species from the International Union for the Conservation of the Nature regional assessments performed in 2007 (Cavanagh and Gibson, 2017) and 2016 (Dulvy et al.19): DD (Data Deficient); LC (Least Concern); NT (Near Threatened); VU (Vulnerable); EN (Endangered); CR (Critically Endangered), not evaluated (NE).

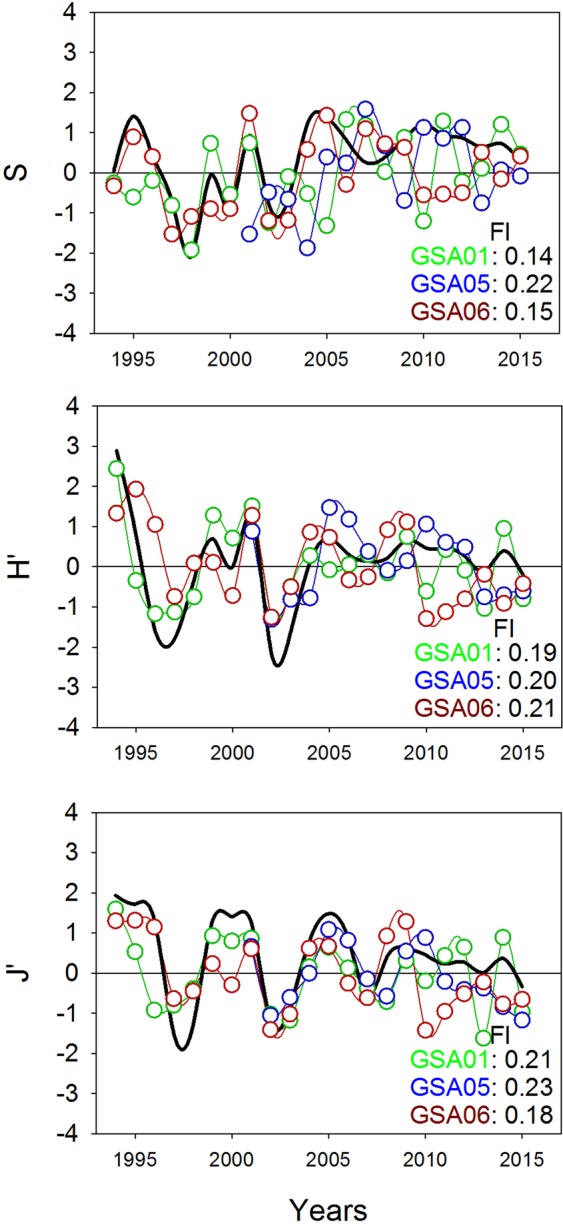

Diversity and species composition

Time series exhibited similar trends for each diversity index (S, H’ and J’), with important fluctuations during the first 15 years, followed by stability over the last five years (Fig. 2, Supplementary Figure S1). DFA results of diversity indices are given in Supplementary Table S2.

Figure 2.

Common temporal trends (black lines) from dynamic factor analysis (DFA) applied to species richness (S), Shannon diversity (H’) and evenness (J’) per geographical sub-area (GSA) considered by the General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean in the study area (GSA01: Northern Alboran Sea, as green lines; GSA05: Balearic Islands, as blue lines; GSA06: Northern Spain, as red lines) during the periods 1994-2015 in GSA01 and GSA06, and 2001–2015 in GSA05. Factor loading (Fl) results for each GSA are indicated in the bottom right corner of each graph.

Scyliorhinus canicula and Galeus melastomus were the most important sharks, and even chondrichthyans, in all GSAs. Scyliorhinus canicula represented >90% and >70% in terms of density and standardized biomass, respectively, in bathymetric strata B and C. In stratum D, G. melastomus corresponded to >50% in both density and standardized biomass in GSA01 and GSA05, while in GSA06, the most frequent was S. canicula (54% and 82% in density and standardized biomass, respectively). In stratum E, G. melastomus represented >85% in both density and standardized biomass (Supplementary Table S3).

The most important batoids in both density and standardized biomass showed differences not only by depth strata, but also by GSA (Supplementary Table S4). In GSA01, the most frequent species were Torpedo marmorata (>40% in both density and standardized biomass) and Raja asterias (14% and 55%, respectively) in stratum B, whilst Leucoraja naevus predominated in strata C and D (>70% in both density and standardized biomass). In GSA05, the most important species in stratum B were Raja miraletus (25% and 5% in density and standardized biomass, respectively), Raja radula (19% and 13%, respectively), and Raja clavata (19% and 34%, respectively); while R. clavata (56% and 78%, respectively), Raja polystigma (18% and 4%, respectively) and L. naevus (17% and 12%, respectively) predominated in stratum C; and R. clavata (59% and 62%, respectively) and Dipturus oxyrinchus (29% and 28%, respectively) predominated in stratum D. In GSA06, R. clavata predominated in all depth strata (≥28% and ≥40% in density and standardized biomass, respectively), while the second most important species was R. asterias, with ≥22% in both density and standardized biomass in stratum B, ≥9% in stratum C, and 33% and 15%, respectively, in stratum D.

Density and standardized biomass

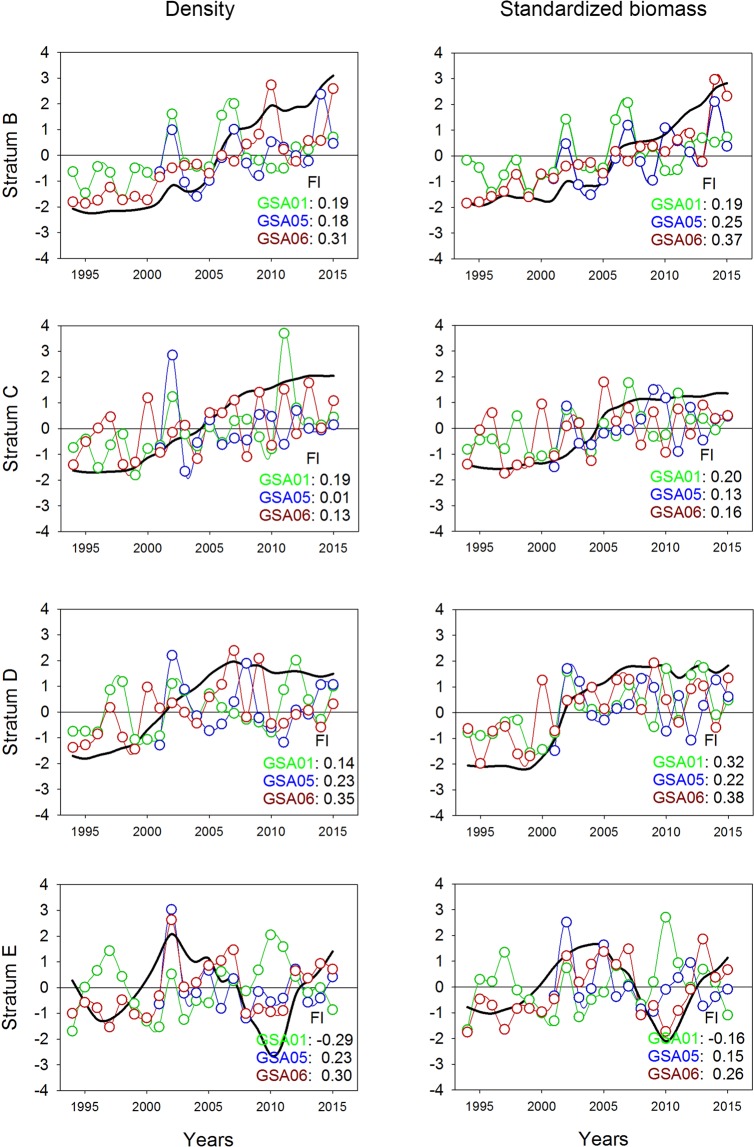

Time series of density and standardized biomass of sharks showed an increase over the study period in depth strata B, C, and D for the three GSAs. In stratum C, low factor loading values were observed in GSA05 and GSA06, suggesting stability over the study period. Stratum E exhibited cyclic changes throughout the study period. In this stratum, negative factor loadings were observed in the case of GSA01, indicating an inverse trend compared to the common trend (Fig. 3, Supplementary Figure S2).

Figure 3.

Common temporal trends (black lines) from dynamic factor analysis (DFA) applied to density and standardized biomass of sharks per geographical sub-area (GSA) considered by the General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean in the study area (GSA01: Northern Alboran Sea, as green lines; GSA05: Balearic Islands, as blue lines; GSA06: Northern Spain, as red lines) and depth stratum (B: 50–100 m; C: 101–200 m; D: 201–500 m; E: 501–800 m) during the periods 1994–2015 in GSA01 and GSA06, and 2001–2015 in GSA05. Factor loading (Fl) results for each GSA are indicated in the bottom right corner of each graph.

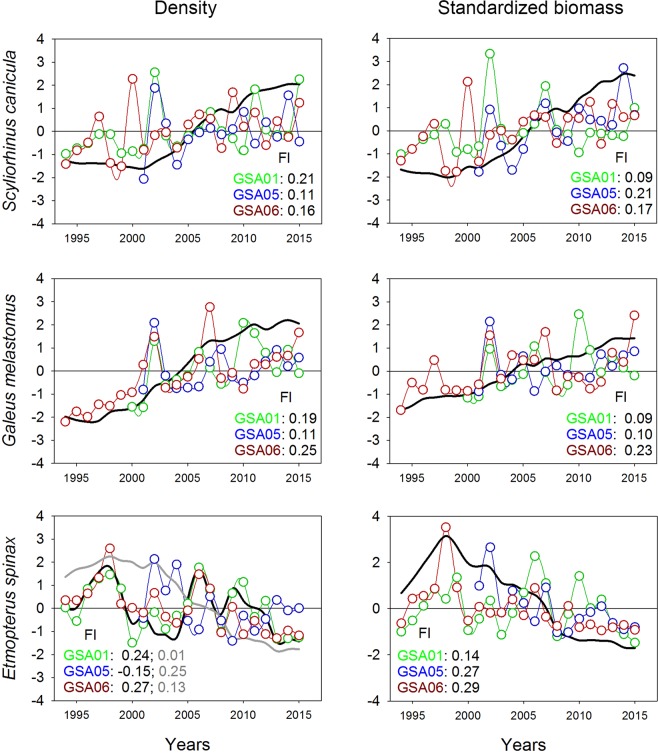

The two most frequent species of sharks, S. canicula and G. melastomus, also showed increasing common trends in both density and standardized biomass over the last 10 years for all GSAs. Nonetheless, low factor loadings observed in density and standardized biomass for GSA05 and GSA02 respectively, suggesting stability throughout the whole period analysed (Fig. 4, Supplementary Figure S3). In the case of Etmopterus spinax, DFAs revealed two possible common trends in density, and one in standardized biomass. The trend in standardized biomass and second trend in density (Fig. 4) showed a decrease over the last 10 years for GSA05. In GSA01 and GSA06, the first trend in density exhibited stability, with fluctuations throughout the study period. DFA results for sharks are given in Supplementary Tables S5–S6.

Figure 4.

Common temporal trends (black lines) from dynamic factor analysis (DFA; grey lines correspond to the second common trend identified) applied to density and standardized biomass for the most abundant sharks, Scyliorhinus canicula, Galeus melastomus and Etmopterus spinax, per geographical sub-area (GSA) considered by the General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean in the study area (GSA01: Northern Alboran Sea, as green lines; GSA05: Balearic Islands, as blue lines; GSA06: Northern Spain, as red lines) during the periods 1994–2015 in GSA01 and GSA06, and 2001–2015 in GSA05. Factor loading (Fl) results for each GSA are indicated in the bottom corner of each graph.

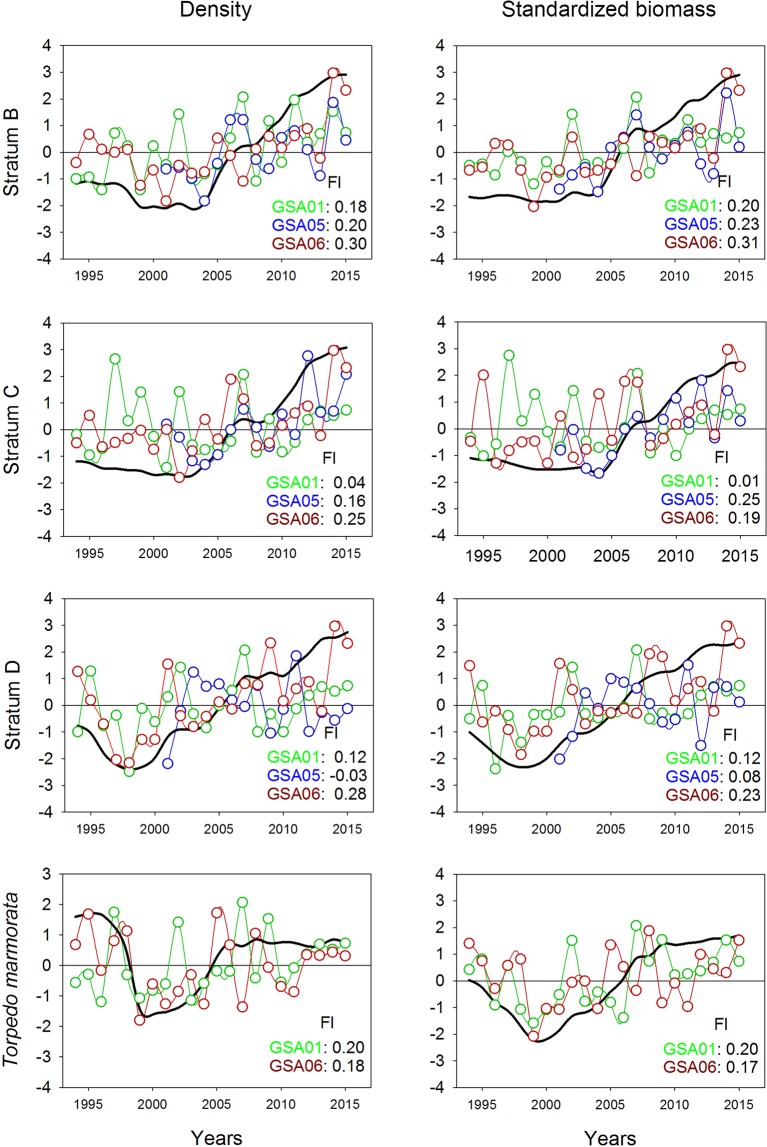

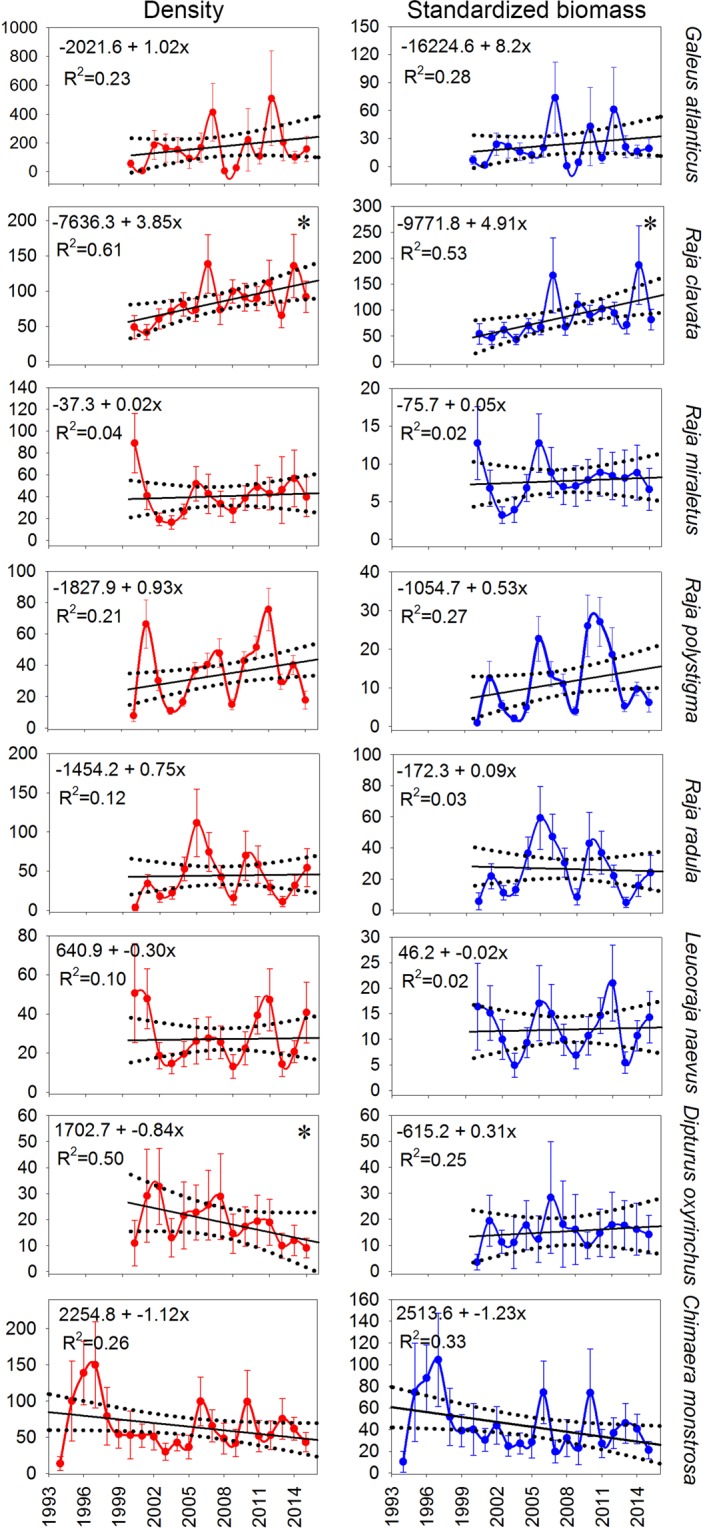

In general, batoids also showed a fairly common increasing temporal trend for the three GSAs, with a rise in density and standardized biomass over the last 10 years (Fig. 5, Supplementary Figure S4). GSA01 and GSA05 showed low factor loadings in strata C and D, respectively, exhibiting stability with fluctuations throughout the study period. Torpedo marmorata showed a decrease in both density and standardized biomass over the first five years, followed by an increase for the next eight years, and finally stability over the last five years (Fig. 5). DFA results for batoids are given in Supplementary Tables S7–S8. In GSA05, the most frequent batoid species, R. clavata, R. miraletus, R. polystigma, R. radula, L. naevus and D. oxyrinchus, exhibited different patterns (Fig. 6). Raja clavata showed an increase over the study period in both density and standardized biomass, while R. miraletus, R. polystigma, R. radula and L. naevus revealed stability and D. oxyrinchus showed a decrease in density, but stability for standardized biomass.

Figure 5.

Common temporal trends (black lines) from dynamic factor analysis (DFA) applied to density and standardized biomass for batoids and Torpedo marmorata. For batoids, the three geographical sub-areas (GSAs) considered by the General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean in the study area (GSA01: Northern Alboran Sea, as green lines; GSA05: Balearic Islands, as blue lines; GSA06: Northern Spain, as red lines) and depth stratum (B: 50–100 m; C: 101–200 m; D: 201–500 m; E: 501–800 m) were utilized during the periods 1994–2015 in GSA01 and GSA06 and 2001–2015 in GSA05. For Torpedo marmorata, the GSA01 and GSA02 were considered. Factor loading (Fl) results for each GSA are indicated in the bottom right corner of each graph.

Figure 6.

Linear regression models of density (in red) and standardized biomass (in blue) indices for the most important species within a particular GSA. Galeus atlanticus and Chimaera monstrosa in GSA01 (Northern Alboran Sea) during the periods 2000–2015 and 1994–2015, respectively. Raja clavata, Raja miraletus, Raja polystigma, Raja radula, Leucoraja naevus and Dipturus oxyrinchus in GSA05 (Balearic Islands) during the period 2001–2015. Dashed lines show 95% confidence intervals for regression lines, while asterisks indicate statistical significance: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Galeus atlanticus and Chimaera monstrosa showed stability in both density and standardized biomass (Fig. 6). The first species was only present in GSA01, while the second one was also caught regularly at this GSA.

Size

DFA models of size structure could be analysed for three species of sharks, S. canicula, G. melastomus and E. spinax. The results of DFA models of these species are given in Supplementary Tables S9–S11. In the case of batoids, the only species whose size structure could be analysed was R. clavata in GSA05.

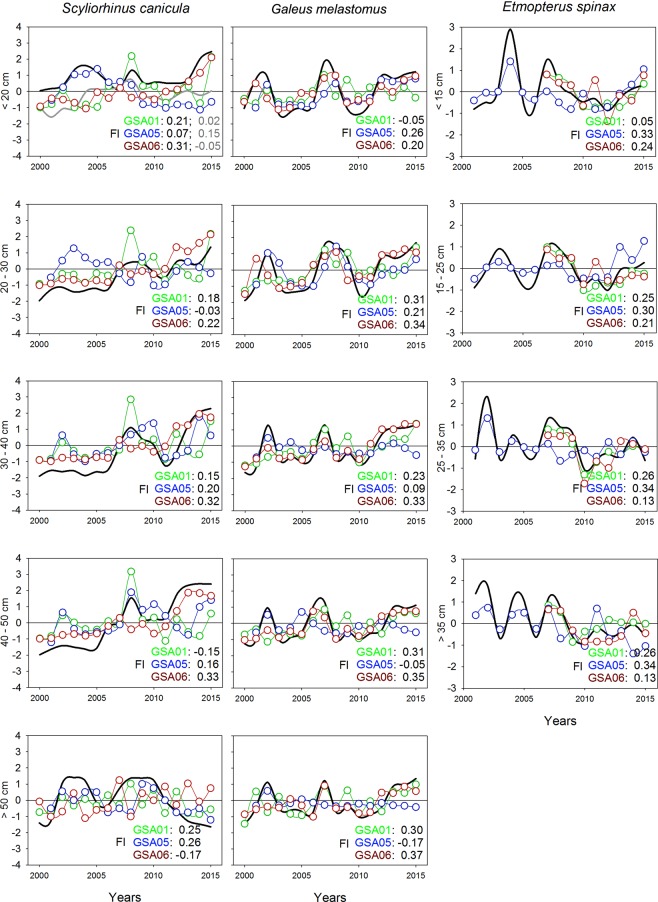

For S. canicula, five length categories were modelled. In the category <20 cm TL, two common trends were observed. The first one was observed in GSA01 and GSA06, showing fluctuations over the early years, followed by stability in the last five years. The second one was observed in GSA05, with stability throughout the study period. The other categories (20–30, 30–40, 40–50 and >50 cm TL) showed a common trend, which suggests stability, with a slight increase in the last four years in the categories 30–40 and 40–50 (Fig. 7, Supplementary Figure S5).

Figure 7.

Common temporal trends (black lines) from dynamic factor analysis (DFA; grey lines correspond to the second common trend identified) applied to density by length category of Scyliorhinus canicula, Galeus melastomus and Etmopterus spinax per geographical sub-area (GSA) considered by the General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean in the study area (GSA01: Northern Alboran Sea, as green lines; GSA05: Balearic Islands, as blue lines; GSA06: Northern Spain, as red lines). The length categories of S. canicula and G. melastomus were the same. Factor loading (Fl) results for each GSA are indicated at the bottom right corner of each graphic.

The same length categories were analysed for G. melastomus. The categories <20 and 20–30 cm TL showed similar trends, with fluctuations in density across the study period, and a slight increase over the last five years. The remaining categories (30–40, 40–50 and >50 cm TL), in general showed stability with slight fluctuations over the study period. In the last two categories, GSA05 had a low negative factor loading, indicating a stability over the study period (Fig. 7, Supplementary Figure S5).

In E. spinax, four length categories were analysed. The category <15 cm TL showed a common trend with a sharp drop followed by a slight increase until 2007 and then stability until the end of the series. The category 15–25 cm TL showed slight increases and decreases. The category 25–35 cm TL exhibited a sharp drop until 2003 followed by apparent stability, with slight fluctuations after 2004. The category >35 cm TL showed cyclic changes, apparently every two years until 2009, followed by stability over the last five years (Fig. 7, Supplementary Figure S5).

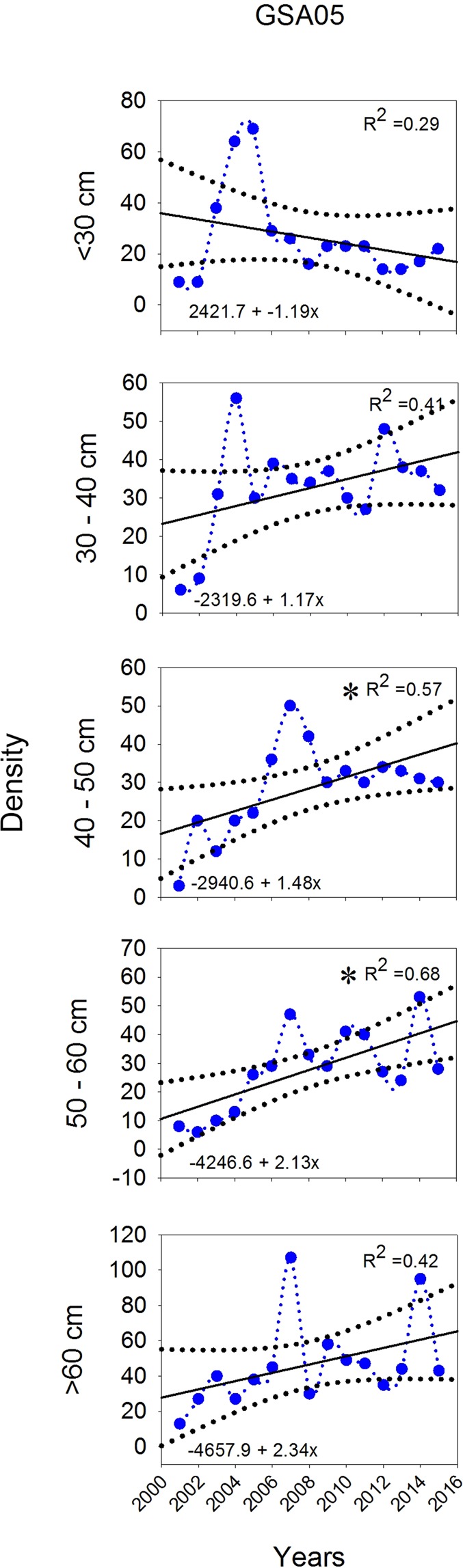

In the case of R. clavata, five length categories were analysed. The categories 40–50 and 50–60 cm TL showed increasing trends, while the remaining categories (<30, 30–40 and >60 cm TL) displayed stability over the study period (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Linear regression models applied to density by length category of Raja clavata in GSA05 (Balearic Islands) during the period 2001–2015. Dashed lines show 95% confidence intervals for regression lines, while asterisks indicate statistical significance: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Maturity

Length at first maturity (L50) could be estimated for two sharks S. canicula and G. melastomus, in all GSAs, and one batoid, R. clavata, in GSA05. Parameters of maturity ogives by year, species, and sex are given in Supplementary Tables S12–S14.

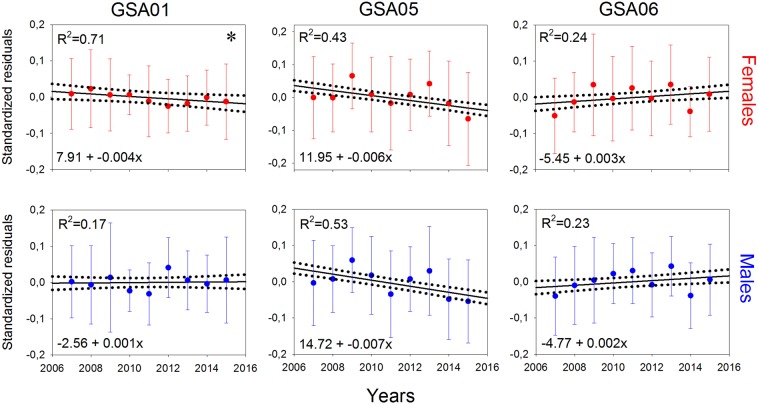

Linear regression models showed a decrease in L50 of S. canicula for both sexes and in all GSAs (Fig. 9). In females, this parameter decreased around 4 cm TL over 16 years in GSA01 and GSA06, and around 1.5 cm TL over 9 years in GSA05. For males this reduction was around 2 cm TL across the same periods. For G. melastomus, a decrease of L50 was also detected for females in GSA06 and males in GSA01, with a reduction of around 2 cm TL over 16 years in both sexes. By contrast, R. clavata did not show any trend in L50 over the study period. The size of the smallest mature female showed similar trends for the three species analysed (Fig. 9).

Figure 9.

Linear regression models of mean annual length at first maturity (L50; standard deviation values are shown) for females (in red) and males (in blue) of Scyliorhinus canicula and Galeus melastomus per geographical sub-area (GSA) considered by the General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean in the study area (GSA01: Northern Alboran Sea; GSA05: Balearic Islands; GSA06: Northern Spain), and for Raja clavata in GSA05, during the periods 2000–2015 in GSA01 and GSA06 and 2007–2015 in GSA05. The SMF plots show the linear regression models for the smallest mature female. Dashed lines show 95% confidence intervals for regression lines, while asterisks indicate statistical significance: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Since S. canicula was the only species with a significant reduction in L50 in both sexes and in the three GSAs, its somatic factor was estimated for small-sized individuals (<35 cm TL). With the only exception of females in GSA01, no significant trends were found across the study period (Fig. 10).

Figure 10.

Linear regression models of somatic condition (mean and standard values) for females (in red) and males (in blue) of Scyliorhinus canicula by geographical sub-area (GSA) considered by the General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean in the study area (GSA01: Northern Alboran Sea; GSA05: Balearic Islands; GSA06: Northern Spain) during the period 2007–2015. Dashed lines show 95% confidence intervals for regression lines, while asterisks indicate statistical significance: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Discussion

In the Mediterranean, there has been increasing international concern for severe declines in the abundance and diversity of chondrichthyans, calling for urgent assessment of fishery exploitation. Here we applied a novel approach, at community and population level, to evaluate the temporal trends of demersal chondrichthyans in three geographical sub-areas along the western Mediterranean over the last two decades, using diversity, density, standardized biomass and biological parameters.

While the diversity indices used in this study measure different aspects of diversity, all of them exhibited similar trends, with relevant changes the firsts years (1994–2004) and stability the last 15 years for the three geographical sub-areas, such as has been observed in the diversity of demersal fishes34 and cephalopods35 throughout the whole Mediterranean. This diversity stability could be explained by the fact that relevant changes in diversity of demersal chondrichthyan communities may have occurred long before the onset of scientific monitoring of fisheries as has been reported in demersal fish communities36. Considering the available scientific literature in the Mediterranean16,17,37–40, there are differences in the demersal chondrichthyan community composition between early fishing explotation (1950’s) and the period studied here (1994–2015). In early fishing exploitation, some of the most threatened chondrichthyans currently such as Galeorhinus galeus, Oxynotus centrina, Scyliorhinus stellaris, Squalus acanthias, Squatina spp. and Rhinobathos spp.18,19 were common in descriptions of fish communities in the trawl fishing grounds off the Balearic Islands37–40 and the Adriatic Sea17. However, these species are no longer detected in scientific surveys for the assessment of demersal resources and have almost disappeared from commercial landings16, in some cases being considered locally extinct41. This change in chondrichthyan community can also be reflected in the percentage of species occurrence, wherein in early fishing exploitation period Scyliorhinus canicula and Galeus melastomus represented around 40% and 10%16,17 of species occurrence and its percentage of occurrence has recently increased to around 90 and 60%, respectively.

In contrast with the decreasing population trends described for chondrichthyan species in different areas of the Mediterranean, such as the Gulf of Lion16, the Ligurian Sea13, the Adriatic Sea4,14 and the Aegean Sea12, our results of density and standardized biomass suggested generally stable trends. Signs of recovery were even observed for the assemblages and the most abundant species inhabiting the continental shelf (S. canicula, Torpedo mamorata and Raja clavata) and for the most abundant species dwelling on the slope (G. melastomus). By contrast, decreasing trends were only detected for the deep water species, Etmopterus spinax and Dipturus oxyrinchus.

Fishing pressure could be one of the main factors contributing to the observed trends. The temporal evolution of the bottom trawl fleet in the western Mediterranean has gone through three phases8,27: (i) from the mid 1960s to mid 1970s, the number of vessels increased by a factor of 2.5; (ii) from the mid 1970s to 2000, this number decreased gradually, although the fishing capacity of this fleet remained constant or even increased, due to its continued growth in terms of engine power; and (iii) since 2000, the number of vessels has continued to decrease, probably along with the fishing capacity of the fleet, as mean engine power has remained fairly constant, especially during recent years. In this sense, our study covers a period of time when the chondrichthyan communities had already been altered in their diversity, and the effort of bottom trawl fishery was fairly stable or, at least, not increasing as previously. However, it is also necessary to consider the technological improvement of fishing gears and vessels during recent decades, which has enabled the worldwide expansion of fisheries to new areas, such as the open ocean and deep sea bottoms42. This has occurred in the western Mediterranean, where trawl fishery has moved from the continental shelf to the slope to capture the decapod crustaceans red shrimp (Aristeus antennatus) and Norway lobster (Nephrops norvegicus) with higher economic value21,43. The no increase in fishing effort of the bottom trawl, jointly with its displacement to deep waters, must be the basis for the current stability and recovery shown by sharks and batoids on the continental shelf. This shift in trawl activity has also been suggested to explain the recent stability observed in demersal chondrichthyans off Sardinia44, in the central western Mediterranean. Similarly, in the north-east Atlantic the progressive reduction of fishing pressure has resulted in the recovery of certain stocks, including S. canicula45–47.

The two most abundant demersal chondrichthyans in the western Mediterranean, S. canicula and G. melastomus, showed increasing trends despite their different bathymetric distribution (continental shelf and shelf break, and upper and middle slope, respectively31,48). Contrary to large chondrichthyans, these two small-medium sharks show life history traits that are less susceptible to fishing pressure (e.g. early maturity, shorter generation time, fast growth, continuous reproductive cycles49–51), giving them greater resilience and capacity of recovery52, as has been recently documented in small coastal sharks in the north-western Atlantic53. In addition, S. canicula and G. melastomus are considered to be opportunistic scavengers that may modify their natural diet to benefit from the disturbed sediments and discards generated by bottom trawling54; moreover, the former species has shown a high survival rate as a discarded catch of this fishery55. A similar situation has been observed for some batoids captured on the continental shelf (R. brachyura, R. clavata, R. montagui and L. naevus56), whose populations showed stability and even recovery in the present study.

The only decreasing trends were observed in the deep-water chondrichthyans, D. oxyrinchus and E. spinax. The decrease in the latter had already been reported in the north western Mediterranean31,57. Deep water chondrichthyans, with longer turnover times than the species dwelling on the continental shelf, are considered to be especially vulnerable to fishing exploitation58,59. This is the case of E. spinax, with late maturation, long reproductive cycle, low fecundity, and considerable longevity60,61. In this sense, E. spinax is quite different from G. melastomus, both species showing distinct life strategies and opposite trends. The deeper bathymetric distribution of G. melastomus, which in the western Mediterranean is relatively abundant down to 1400 m depth62–64, could also contribute to the stability of populations of this species. In this area, bottom trawl fishery does not reach more than 800–900 m depth65 and, moreover, the GFCM decided in 2006 to ban this fishery beyond 1000 m depth.

Regarding biological descriptors of main species, no clear trends were observed in size composition, although a decreasing trend in length at first maturity (L50) and the size of the smallest mature female was detected for S. canicula in all GSAs. It is known that fishing overexploitation could alter size structure and population parameters (e.g. fecundity, maturity, growth rate) on chondrichthyan populations in response to changes in species abundance (density-dependence change)3,66–68. Early maturity detected in S. canicula could be an indicator that the populations of this species have been under stress, due to the high level of trawl fishing exploitation in the study area. In fact, general overfishing of the demersal population around the Balearic Islands during the 1980s included elasmobranchs8. This early maturation, an adaptive response that increases the likelihood of offspring reaching maturity69, could have promoted the present recovery of S. canicula. Two possible mechanisms could explain this adaptation: an evolutionary response to selection for smaller size at maturity and/or by reducing intra-specific competition, due to reduction in species abundance, with the consequent increase in available food66,70. Environment is another potential mechanism that is deemed to influence life history changes in chondrichtyans3,27. Favourable conditions (e.g. intensive upwelling, high productivity) produce higher quality offspring that grow at faster rates, resulting in early maturation67,68. However, since no significant trends were found in somatic condition, this is not the case of S. canicula populations. Thus, the most plausible hypothesis to explain the early maturation of this species is its evolutionary response to overfishing. In fact, before changing growth rate, fishes use their somatic energy reserves to meet the running costs of their basal metabolism (e.g., maintenance, immune defence, and cognition), digestion, or routine activities such as migration to breeding grounds, courting, competition for mates and breeding sites, copulation, and parental care71,72.

Detecting changes in population parameters of chondrichthyans is difficult since they are typical k strategists in comparison to teleosts3,73. Given that small size chondrichthyans have a higher intrinsic population growth rate than larger species52,73, these changes have been detected mainly in few small-medium sharks such as Rhizoprionodon terraenovae68 and Squalus acanthias74. These change in population parameters could provide a compensatory mechanism in small-medium chondrichthyans decreasing the natural and fishing mortality, and likely promoting the recovery of those exploited populations75.

In summary, this study shows the feasibility of fishery-independent scientific surveys, which are currently being developed in the Mediterranean, to evaluate the populations trends of by-catch vulnerable species such as demersal chondrichthyans. Our trend models reveal that most of the sharks and batoids currently making up these communities have resisted the impact of fishing on the western Mediterranean over the last two decades. However, this is not the case for two deep water species, which are not resisting fishing exploitation. These results can be explained by the evolution of the trawl fishery (reduction of effort and displacement to deeper waters) over the last few decades, jointly with the great resilience displayed by some of these species, like S. canicula, a small-medium shark which also showed a reduction of its length at first maturity, probably as an evolutionary response to the general overfishing of the demersal populations exploited by bottom trawl fishery since the 1980s in the study area. Our findings, which come from a long period of over-exploitation of these vulnerable species - some of which appeared to be fairly common and have currently almost disappeared or are even considered to be locally extinct - provide a current baseline scenario in order to implement management measures that will strengthen or initiate the recovery of chondrichthyans in the Mediterranean, whose populations play an important role in marine ecosystems, and to develop true adaptive management in the area, making the sustainability of trawl fishery compatible with the conservation of marine ecosystems.

Methods

Ethic statement

Data were obtained in the framework of the MEDITS project and refer to the Mediterranean Iberian Peninsula and the Balearic Islands. The sampling scheme followed a standartized protocol76 approved by international authorities (EU/DG Mare, FAO/GFCM). If a live specimen of a rare species or a species subject to conservation measures was caught, it was quickly sampled (4–5 minutes) and returned back to the sea unharmed, giving it a chance for survival, following the recommendation GFCM/36/2012/3 (http://www.gfcmonline.org/decisions/) on fisheries management measures for conservation of sharks and rays in the GFCM area. In the cases the animal was alive when it arrived on the vessel during the scientific survey (MEDITS – DCF, EU Reg. 199/2008), it was suppressed by administering an overdose of anaesthetic in compliance with the recommendation of Decree Law n. 26 of 4 March 2014. All efforts were made to minimize suffering.

Data source

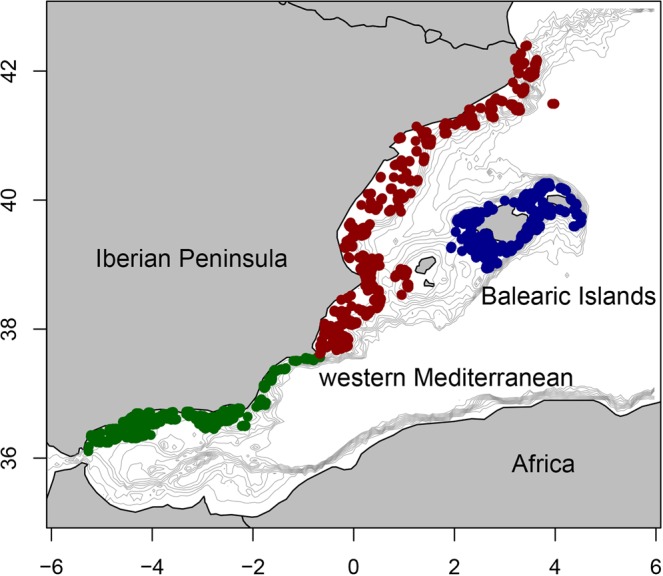

A total of 3158 stations were sampled during the MEDITS bottom trawl surveys, carried out annually during spring and early summer from 1994 along the Mediterranean Iberian Peninsula and the Balearic Islands (Fig. 11). The sampling method is described in MEDITS protocol76. A stratified random sampling scheme was applied, considering five bathymetric strata on the continental shelf and slope (A: 30–50 m; B: 51–100 m; C: 101–200 m; D: 201–500 m; E: 501–800 m) and the three geographical sub-areas (GSAs) recognised by the General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean (GFCM) off the Spanish coast (GSA01: Northern Alboran Sea; GSA05: Balearic Islands; GSA06: Northern Spain; Fig. 2). The number of stations per year, GSA and bathymetric stratum are given in Supplementary Table S1. The sampling gear was the experimental bottom trawl GOC-73, equipped with a 20 mm mesh size in the cod-end. Hauls were conducted during daylight hours at a towing speed of around 3 knots, with an effective duration of 30’ at depths shallower than 200 m and 60’ below this depth. The arrival and departure of the net to the bottom, in addition to its horizontal and vertical openings (2.4–3 and 16–22 m, respectively) were measured using a SCANMAR system (http://www.scanmar.no/en/) consisting in a set of sensors attached to the gear, which allow its depth and geometry during the haul to be measured simultaneously.

Figure 11.

Map of the western Mediterranean showing the MEDITS stations developed between 1994 and 2015 used in the present study. Colours correspond to the three geographical sub-areas (GSAs) considered by the General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean in the study area: green is GSA01 (Northern Alboran Sea); blue is GSA05 (Balearic Islands) and red is GSA06 (Northern Spain). Isobaths between 50 and 2000 m (every 200 m) are also shown.

The catch of each sample was sorted, identified to species level, counted and weighed, and length of individuals was measured. Data on abundance and biomass were standardized to number of individuals per km2 (referred to as “density”) and to kg per km2 (referred to as “standardized biomass”), respectively. To do so, the bottom surface sampled during the haul was considered, estimated from the horizontal opening of the net, and the distance covered, obtained from a GPS system. Sex and sexual maturity were determined from macroscopic examination of the gonads, following Holden and Raitt’s maturity scale77, which considers four stages for both females and males: immature, maturing, spawning and post-spawning.

The time series of data on density and standardized biomass spanned from 1994 to 2015 for GSA01 and GSA06, and from 2001 to 2015 for GSA05. Due to changes in the MEDITS sampling protocol over the years, data series on size and sexual maturity were shorter. In GSA01 and GSA06 it comprised the period 2000–2015, whereas available periods in GSA05 were 2001–2015 and 2007–2015 for size and sexual maturity, respectively.

Data analysis

Dynamic factor analysis (DFA), a multivariable method applied to relatively short and non stationary time series data to detect common trends77,78, was applied to identify common trends between GSAs for diversity, density, standardized biomass and size structure parameters. In DFA, time series data are modelled as a linear combination of underlying common trends and factor loading indicates the strength of the influence of each GSA time series on the corresponding common trend. In order to achieve a proper interpretation of our results, the time series were standardized by subtracting the mean and dividing by the standard deviation78. Factor loadings with values above 0.20 (in absolute value) signifies that the corresponding GSA has a high contribution to the common trend detected77. Negative factor loading values indicate that the particular GSA has an inverse trend to the one detected as a common trend. Correlation of observation errors was modelled using different covariance matrices: (i) same variance and no covariance (diagonal-equal); (ii) different variances and no covariance (diagonal-unequal); (iii) same variance and covariance (equalvarcov); and (iv) different variances and covariances (unconstrained). The corrected Akaike information criterion (AICc) was used as a measure of goodness of fit, with the best model having the lowest AICc78,79. Model implementation was performed using the Multivariate Autoregressive State-Space “MARSS” package80 in R 3.3.2.

DFAs were applied to diversity, density and standardized biomass time series in order to search for common trends between GSAs along the study period. In this study, we evaluated the following diversity indices to identify a set of indicators that could provide a good representation of changes in demersal chondrichthyan communities, taking account the different aspects of diversity: mean species richness index (S), the Shannon-Wiener diversity index (H’) and evenness (J’) that were estimated by year and GSA.

The mean density and standardized biomass of the chondrichthyan groups (sharks, batoids and chimaeras) were calculated by year, GSA and depth stratum, except in stratum A, which was excluded from the analysis due to the low number of sampling stations. These parameters were also estimated by GSA for the most abundant species within their bathymetric distribution range. These species were those representing ≥85% density or standardized biomass in at least two GSAs, or with a percentage occurrence greater than 20% within their depth range of distribution for all GSAs. Since the presence of batoids was practically zero below 500 m depth, stratum E was not considered for this group.

Temporal trends in size structure were also evaluated for the most important species in the three GSAs. To do this, sexes were pooled into different categories according to the total length (TL) of the species, and the mean density by year was calculated. DFAs were applied to identify common trends between GSAs in density values for each length category from 2000 to 2015.

Meanwhile, linear regression analyses were applied to detect temporal trends for the most important species within a particular GSA (i.e. those representing ≥85% density and standardized biomass and with a percentage occurrence within the depth range of distribution ≥20%), in both density and size structure. Dasyatis pastinaca was not included in this analysis because of the possible misidentification with Dasyatis cf. tortonesei in the Balearic Islands81.

Linear regression analysis was also used to detect temporal trends of size at first maturity of the most important species. Maturity was assessed for species with at least 50 individuals sampled per year and GSA. To do this, maturation stages were converted into binary data (stages i and ii as immature and stages iii and iv as mature), while length at first maturity (L50; length at which 50% of the individuals are mature) was obtained by fitting a logistic regression to the proportion of mature individuals by length class. This was done for females and males and by year and GSA. The smallest length of mature females per year for each GSA was also estimated. In addition, considering the fact that the condition of fishes has been reported as an important factor affecting growth rate82 and that an increase in growth rate before the onset of maturation can lead to a decrease age and therefore size and maturity83, we also analysed the temporal trend in somatic condition for species with a significant decreasing trend in L50. For these species, we calculated the somatic condition for immature individuals (below the length at first maturity reported for these species in the study area48) of both sexes. Individual total weight (TW) and total length (TL) were log-transformed and the linear relationship between logTW and logTL was established by year. Residuals of the differences between the observed and predicted logTW were calculated and standardized, dividing each one by the standard deviation of their predicted values84. Lastly, linear regression analysis was applied to detect temporal trends from 2007 to 2015 in each GSA.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all the participants in the MEDITS surveys, as well as the crew of R/V Cornide de Saavedra and R/V Miguel Oliver. This research was supported in part by the Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACyT) of Mexico, through the FPI Fellowship of SRA, the projects DEMBAGOL and DEMALBORAN funded by the European Commission and the Instituto Español de Oceanografía through the Data Collection Framework, and the projects ECLIPSAME (CTM2012-37701) and CLIFISH (CTM2015-66400-C3-1-R) funded by FEDER and the Spanish Ministry of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness.

Author contributions

S.R.A., F.O., B.T. and E.M. designed the study. S.R.A., A.E., C.G., B.G. and F.S. collected data. S.R.A., F.O. and E.M. performed data analysis. S.R.A., F.O. and E.M. wrote the main manuscript text. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-56818-9.

References

- 1.Lotze HK, et al. Depletion, degradation, and recovery potential of estuaries and coastal seas. Science. 2006;312:1806–1809. doi: 10.1126/science.1128035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coll M, et al. The biodiversity of the Mediterranean Sea: estimates, patterns and threats. PLoS ONE. 2010;5((8)):e11842. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stevens JD, Bonfil R, Dulvy NK, Walker PA. The effects of fishing on sharks, rays, and chimaeras (Chondrichthyans), and the implications for marine ecosystems. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2000;57:476–494. doi: 10.1006/jmsc.2000.0724. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferretti F, Worm B, Britten G, Heithaus MR, Lotze HK. Patterns and ecosystem consequences of shark declines in the ocean. Ecol. Lett. 2010;13:1055–1071. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2010.01489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferretti F, Osio GC, Jenkins CJ, Rosenberg AA, Lotze HK. Long-term change in a meso-predator community in response to prolonged and heterogeneous human impact. Sci. Rep. 2013;3:1057. doi: 10.1038/srep01057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davidson LNK, Krawchuk MA, Dulvy NK. Why have global shark and ray landings declined: Improved management or overfishing? Fish Fish. 2016;17:438–458. doi: 10.1111/faf.12119. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palomera I, et al. Small pelagic fish in the NW Mediterranean Sea: an ecological review. Prog. Oceanogr. 2007;74:377–396. doi: 10.1016/j.pocean.2007.04.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quetglas A, et al. Synchronous combined effects of fishing and climate within a demersal community. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2013;70:319–328. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fss181. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsikliras AC, Dinouli A, Tsiros VZ, Tsalkou E. The Mediterranean and Black Sea fisheries at risk from overexploitation. PLoS ONE. 2015;10((3)):e0121188. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Piroddi C, et al. Historical changes of the Mediterranean Sea ecosystem: modelling the role and impact of primary productivity and fisheries changes over time. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:44491. doi: 10.1038/srep44491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferretti F, Myers RA, Serena F, Lotze HK. Loss of large predatory sharks from the Mediterranean Sea. Conserv. Biol. 2008;22:952–964. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2008.00938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maravelias CD, Tserpes G, Pantazi M, Peristeraki P. Habitat selection and temporal abundance fluctuations of demersal cartilaginous species in the Aegean Sea (Eastern Mediterranean) PLoS ONE, 2012;7((4)):e35474. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ligas A, Osio G, Sartor P, Sbrana M, De Ranieri S. Long-term trajectory of some elasmobranch species off the Tuscany coasts (NW Mediterranean) from 50 years of catch data. Sci. Mar. 2013;77(1):119–127. doi: 10.3989/scimar.03654.21C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barausse A, et al. The role of fisheries and the environment in driving the decline of elasmobranchs in the northern Adriatic Sea. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2014;71(7):1593–1603. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fst222. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iglésias SP, Toulhoat L, Sellos DY. Taxonomic confusion and market mislabelling of threatened skates: important consequences for their conservation status. Aquat. Conserv. 2010;20:319–333. doi: 10.1002/aqc.1083. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aldebert Y. Demersal resources of the Gulf of Lions (Mediterranean). Impact on fish diversity. Vie et Milieu. 1997;47:275–284. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jukic-Peladic S, Vrgoc N, Krstulovic-Sifner S, Piccinetti C, Piccinetti-Manfrin G, Marano G, Ungaro N. Long-term changes in demersal resources of the Adriatic Sea: comparison between trawl surveys carried out in 1948 and 1998. Fisheries Research. 2001;53(1):95–104. doi: 10.1016/S0165-7836(00)00232-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cavanagh R.D. & Gibson C. Overview of the Conservation Status of Cartilaginous Fishes (Chondrichthyans) in the Mediterranean Sea. Switzerland & Málaga: IUCN: Gland (2007).

- 19.Dulvy N.K., Allen D.J., Ralph G.M. & Walls R.H.L. The conservation status of sharks, rays and chimaeras in the Mediterranean Sea [Brochure]. Malaga, Spain: IUCN (2016).

- 20.Lleonart J, Maynou F. Fish stock assessments in the Mediterranean: state of the art. Sci. Mar. 2003;67:37–49. doi: 10.3989/scimar.2003.67s137. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moranta J, et al. Spatio-temporal variations in deep-sea demersal communities off the Balearic Islands (western Mediterranean) J. Marine Syst. 2008;71:346–366. doi: 10.1016/j.jmarsys.2007.02.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moranta J, Massutí E, Morales-Nin B. Fish catch composition of the deep-sea decapod crustacean fisheries in the Balearic Islands (western Mediterranean) Fish. Res. 2000;45:253–264. doi: 10.1016/S0165-7836(99)00119-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carbonell A, Alemany F, Merella P, Quetglas A, Román E. The by-catch of sharks in the western Mediterranean (Balearic Islands) trawl fishery. Fish. Res. 2003;61:7–18. doi: 10.1016/S0165-7836(02)00242-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guijarro B, et al. Inter- and intra-annual trends and status indicators of nektobenthic elasmobranchs off the Balearic Islands (northwestern Mediterranean) Sci. Mar. 2012;76(1):87–96. doi: 10.3989/scimar.03432.22A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Browman HI, Stergiou KI. Introduction. Perspectives on ecosystem-based approaches to the management of marine resources. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2004;274:269–303. doi: 10.3354/meps274269. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ordines F, et al. Red algal beds increase the condition of nekton-benthic fish. J Sea Res. 2015;95:115–123. doi: 10.1016/j.seares.2014.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quetglas A, Rueda L, Alvarez-Berastegui D, Guijarro B, Massutí E. Contrasting reponses to harvesting and environmental drivers of fast and slow life history species. Plos ONE, 2016;11((2)):e0148770. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ellis JK, Dulvy NK, Jennings S, Parker-Humphreys M, Roger SI. Assessing the status of demersal elasmobranchs in UK waters: a review. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. U. K. 2005;85:1025–1047. doi: 10.1017/S0025315405012099. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Massutí E, Moranta J. Demersal assemblages and depth distribution of elasmobranchs from the continental shelf and slope trawling grounds off the Balearic Islands (western Mediterranean) ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2013;60:753–766. doi: 10.1016/S1054-3139(03)00089-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bertrand JA, Aldebert Y, Souplet A. Temporal variability of demersal species in the Gulf of Lions from trawl surveys (1983-1997) IFREMER Actes des Colloques. 1998;26:153–164. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ordines F, et al. Balearic Islands vs Algeria: two nearby western Mediterranean elasmobranch assemblages with different oceanographic scenarios and fishing histories. Sci. Mar. 2011;75:707–717. doi: 10.3989/scimar.2011.75n4707. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coll M, Navarro J, Palomera I. Ecological role, fishing impact, and management options for the recovery of a Mediterranean endemic skate by means of food web models. Biol. Cons. 2013;157:108–120. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2012.06.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Colloca F, Enea M, Ragonese S, Di Lorenzo M. A century of fishery data documenting the collapse of smooth-hounds (Mustelus spp.) in the Mediterranean Sea. Aquat. Conserv. 2017;27(6):1145–1155. doi: 10.1002/aqc.2789. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Granger V, et al. Large-scale spatio-temporal monitoring highlights hotspots of demersal fish diversity in the Mediterranean Sea. Prog. Oceanogr. 2015;130:65–74. doi: 10.1016/j.pocean.2014.10.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Keller S, et al. Large-scale spatio-temporal patterns of mediterranean cephalopod diversity. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:1–19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Farriols MT, et al. Bottom trawl impacts on Mediterranean demersal fish diversity: Not do obvious or are we too late? Cont. Shelf Res. 2017;137:84–102. doi: 10.1016/j.csr.2016.11.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ferrer, J. Catálogo de los peces de Menorca. (2nd ed.) Maó, Spain: Tipografía Mahonesa (1930).

- 38.De Buen F. Fauna ictiológica. Catálogo de los peces ibéricos: de la planicie continental, aguas dulces, pelágicos y de los abismos próximos. 1ª Parte: Notas y Resúmenes. Instituto Español de Oceanografía, Ser. II (1935).

- 39.Oliver, F. Catálogo de la Fauna Marítima de Mallorca. Spain: Publicaciones del Instituto Social de la Marina (1944).

- 40.Maurin C. Ecologie ichthyologique des fonds chalutables altantiques (de la baie ibéro-marocaine à la Mauritanie) et de la Méditerranée occidentale. Reuve des Travaux de I’Institut des Pêches Maritimes (1968).

- 41.Grau A.M., Mayol J., Oliver J., Riera F. & Riera M.A. Libre vermell dels peixos de les Illes Balears. Spain: Conselleria de Medi Ambient, Agricultura i Pesca (2015).

- 42.Worm B, et al. Global catches, exploitation rates, and rebuilding options for sharks. Mar. Policy. 2013;40:194–204. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2012.12.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hidalgo M, et al. Population effects and changes in life-history traits in relation to phase transitions induced by long-term fishery harvesting: European hake off the Balearic Islands. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2009;66:1355–1370. doi: 10.1139/F09-081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marongiu MF, et al. Temporal dynamics of demersal chondrichthyan species in the central western Mediterranean Sea: The case study in Sardinia Island. Fish. Res. 2017;193:81–94. doi: 10.1016/j.fishres.2017.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Collie J, Rochet MJ, Bell R. Rebuilding fish communities: the ghost of fisheries past and the virtue of patience. Ecol. Appl. 2013;23:374–391. doi: 10.1890/12-0877.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Modica L, Velasco F, Preciado I, Soto M, Greenstreet SPR. Development of the large fish indicator and associated target for a Northeast Atlantic fish community. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2014;71:2403–2415. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsu101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arroyo NL, Preciado I, López-López L, Muñoz I, Punzón A. Trophic mechanisms underlying bentho-demersal community recovery in the north-east Atlantic. J. Appl. Ecol. 2017;54:1957–1967. doi: 10.1111/1365-2664.12879. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ramírez-Amaro S, et al. Demersal chondrichthyans in the Western Mediterranean: assemblages and biological parameters of their main species. Mar Freshw Res. 2015;67:636–652. doi: 10.1071/MF15093. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Camhi M., Fowler S., Musick J., Bräutigam A. & Fordham, S. Sharks and their Relatives Ecology and Conservation. Cambridge, UK: IUCN/SSC Shark Specialist Group. UICN (1998).

- 50.Rey J, Massutí E, Gil de Sola L. Distribution and biology of the blackmouth catshark Galeus melastomus in the Alborán Sea (southwestern Mediterranean) J. Northwest Atl. Fish. Sci. 2005;35:215–223. doi: 10.2960/J.v35.m484. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Capapé C, Guélorget O, Siau Y, Vergne Y, Quignard JP. Reproductive biology of the thornback ray Raja clavata (Chondrichthyes: Rajidae) from the coast of Languedoc (southern France, northern Mediterranean) Vie et Milieu. 2007;57:83–90. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Au DW, Smith SE, Show C. New abbreviated calculation for measuring intrinsic rebound potential in exploited fish populations–example for sharks. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2015;72:1–7. doi: 10.1139/cjfas-2014-0360. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Peterson CD, et al. Preliminary recovery of coastal sharks in the south-east United States. Fish Fish. 2017;18(5):845–859. doi: 10.1111/faf.12210. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Olaso I, et al. Trophic relations of lesser-spotted catshark (Scyliorhinus canicula) and blackmouth catshark (Galeus melastomus) in the Cantabrian Sea. J. Northwest Atl. Fish. Sci. 2005;35:481–494. doi: 10.2960/J.v35.m494. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rodríguez-Cabello, C., Fernández, A., Olaso, I. & Sánchez, F. Survival of lesser spotted dogfish Scyliorhinus canicula discarded by trawlers in the Cantabrian Sea. ICESCM2001/N06 (2001).

- 56.Enever R, Catchpole TL, Ellis JR, Grant A. The survival of skates (Rajidae) caught by demersal trawlers fishing in UK waters. Fish. Res. 2009;97:72–76. doi: 10.1016/j.fishres.2009.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cartes JE, Fanelli E, Lloris D, Matallanas J. Effect of environmental variations on sharks and other top predators in the deep Mediterranean Sea over the last 60 years. Clim. Res. 2013;55:239–251. doi: 10.3354/cr01137. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.García VB, Lucifora LO, Myers RA. The importance of habitat and life history to extinction risk in sharks, skates, rays and chimaeras. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Biol. 2008;275:83–89. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2007.1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Simpfendorfer CA, Kyne PM. Limited potential to recover from overfishing raises concerns for deep-sea sharks, rays and chimaeras. Environ. Conserv. 2009;36:97–103. doi: 10.1017/S0376892909990191. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Coelho R, Erzini K. Length at first maturity of two species of lantern sharks (Etmopterus spinax and Etmopterus pusillus) off southern Portugal. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. U. K. 2005;85:1163–1165. doi: 10.1017/S0025315405012245. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Coelho R, Erzini K. Life history of a wide-ranging deepwater lantern shark in the north-east Atlantic, Etmopterus spinax (Chondrichthyes: Etmopteridae), with implications for conservation. J Fish Biol. 2008;73:1419–1443. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8649.2008.02021.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stefanescu C, Lloris D, Rucabado J. Deep-living demersal fishes in the Catalan Sea (western Mediterranean) below a depth of 1000 m. J. Nat. Hist. 1992;26:197–213. doi: 10.1080/00222939200770081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Moranta J, Stefanescu C, Massutí E, Morales-Nin B, Lloris D. Fish community structure and depth-related trends on the continental slope of the Balearic Islands (Algerian basin, western Mediterranean) Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1998;171:247–259. doi: 10.3354/meps171247. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Massutí E, et al. Mediterranean and Atlantic deep-sea fish assemblages: differences in biomass composition and size related structure. Sci. Mar. 2004;68:101–115. doi: 10.3989/scimar.2004.68s3101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sardà F, et al. Deep-sea distribution, biological and ecological aspects of Aristeus antenntus (Risso, 1816) in the western and central Mediterranean Sea. Sci. Mar. 2004;68:117–127. doi: 10.3989/scimar.2004.68s3117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Holden MJ. Are long-term sustainable fisheries for elasmobranchs possible? In: Fish stocks and recruitment. ICES Rapp. Proc.-Verb. 1973;164:360–367. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sosebee KA. Are density-dependent effects on elasmobranch maturity possible? J. Northw. Atl. Fish. Sci. 2005;35:115–124. doi: 10.2960/J.v35.m492. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Carlson JK, Baremore IE. Changes in biological parameters of Atlantic sharpnose shark Rhizoprionodon terraenovae in the Gulf of Mexico: Evidence for density-dependent growth and maturity? Mar. Freshw Res. 2003;54:227–234. doi: 10.1071/MF02153. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Smith SE, Au DW, Show C. Intrinsic rebound potential of 26 species of Pacific sharks. Mar Freshw Res. 1998;49:663–678. doi: 10.1071/MF97135. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Holden MJ. Are long-term sustainable fisheries for elasmobranch possible? Rapports et Procès-Verbaux des Réunions du Conseil International pour l’Exploration de la Mer. 1973;164:360–367. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Goldman, K. J. Age and growth of elasmobranch fishes In Elasmobranch fisheries management techniques. (eds. Bonfil, R. & Musick, J. A.) 97–132 (Singapore: Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation, 2004).

- 72.Enberg K, et al. Fishing-induced evolution growth: concepts, mechanism and the empirical evidence. Mar. Ecol. 2012;33:1–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0485.2011.00460.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cailliet, G. M., Yudin, K. G., Tanaka, S. & Tanisuchi, T. Growth characteristics of two populations of Mustelus manazo from Japan based on cross-reading vertebral bands. In: Pratt, H. L. Jr., Gruber, S. H. & Taniuchi, T. (Eds.), Elasmobranchs as living resources: Advances in biology, ecology, systematic and the status of the fisheries (pp. 167–176). NOAA Technical Report. NMFS. (1990).

- 74.Saunders MW, McFarlane GA. Age and length at maturity of female spiny dogfish, Squalus acanthias, in the Strait of Georgia, British Columbia, Canada. Environ. Biol. Fishes. 1993;38((1)):49–57. doi: 10.1007/BF00842903. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wood CC, Ketchen KS, Beamish RJ. Population dynamics of spiny dogfish (Squalus acanthias) in British Columbia waters. Journal of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada. 1979;36:647–655. doi: 10.1139/f79-094. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bertrand JA, Gil de Sola L, Papaconstantinou C, Relini G, Souplet A. The general specifications of the MEDITS surveys. Sci. Mar. 2002;66(2):9–17. doi: 10.3989/scimar.2002.66s29. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zuur AF, Tuck ID, Bailey N. Dynamics factor analysis to estimate common trends in fishery time series. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2003;60:542–552. doi: 10.1139/f03-030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zuur AF, Fryer RJ, Jolliffe IT, Dekker R, Beukema JJ. Estimating common trends in multivariate time series using dynamic factor analysis. Environmetrics. 2003;14:665–685. doi: 10.1002/env.611. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zuur AF, Pierce GJ. Common trends in northeast Atlantic squid time series. J Sea Res. 2004;52:57–72. doi: 10.1016/j.seares.2003.08.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Holmes EE, Ward EJ, Willis K. MARSS: Multivariate Autoregressive State-Space Modelling. R package version. 2013;3:9. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ramírez-Amaro S, et al. The evolutionary history of Mediterranean Batoidea (Chondrichthyes: Neoselachii) Zool. Scr. 2018;47:686–698. doi: 10.1111/zsc.12315. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lloret, J., Shulman, G. & Love, R. M. Condition and Health Indicators of Exploited Marine Fishes. John Wiley & Sons. 263 pp (2013).

- 83.Jonsson B, Jonsson N, Finstad AG. Effects of temperature and food quality on age and size at maturity in ectotherms: an experimental test with Atlantic salmon. J Anim Ecol. 2013;82:201–2010. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2012.02022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hayes, J. & Shonkwiler, J. Morphometric indicators of body condition: worth- while or wish thinking? In Body Composition Analysis of Animals: A Handbook of Non-destructive Methods. (ed. Speakman, J.) 8–38 (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2001).

- 85.FAO. FishStatJ software for fishery statistical time series. Rome, Italy Available at: www.fao.org/fishery/statistics/software/fishstat (2017).

- 86.Kleisner K, Froese D, Zeller D, Pauly D. Using global catch data for inferences on the world’s marine fisheries. Fish Fish. 2012;14:293–311. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2979.2012.00469.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.