Abstract

Major depressive disorder (MDD) often emerges during adolescence with detrimental effects on development as well as lifetime consequences. Identifying neurobiological markers that are associated with the onset or course of this disorder in childhood and adolescence is important for early recognition and intervention and, potentially, for the prevention of illness onset. In this systematic review, 68 longitudinal neuroimaging studies, from 34 unique samples, that examined the association of neuroimaging markers with onset or changes in paediatric depression published up to 1 February 2019 were examined. These studies employed different imaging modalities at baseline; structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), functional MRI (fMRI) or electroencephalography (EEG). Most consistent evidence across studies was found for blunted reward-related (striatal) activity (fMRI and EEG) as a potential biological marker for both MDD onset and course. With regard to structural brain measures, the results were highly inconsistent, likely caused by insufficient power to detect complex mediating effects of genetic and environmental factors in small sample sizes. Overall, there were a limited number of samples, and confounding factors such as sex and pubertal development were often not considered, whereas these factors are likely to be relevant especially in this age range.

Keywords: Depression, Adolescence, Childhood, Neuroimaging, Prediction

1. Introduction

Depression is one of the main causes of disability worldwide and a major contributor to the overall global disease burden (Murray et al., 2012). Approximately 300 million people were affected by this disorder in 2015 (World Health Organization, 2017). Adolescence and young adulthood are the lifetime peak periods for onset of major depressive disorder (MDD) (Kessler et al., 2007, 2005; Weissman et al., 1996). Early onset of depression has deleterious consequences on overall physical and mental development, and is related to poorer academic, occupational and social outcomes (Zisook et al., 2007). Furthermore, adolescent-onset depression has been associated with suicidality, psychiatric and medical comorbidities as well as an elevated risk of MDD episodes and anxiety disorders later in life (Fergusson and Woodward, 2002; Jaycox et al., 2009; Sun and Wang, 2015; Zisook et al., 2007, 2004). Clearly, identifying measures that represent vulnerability factors for developing depression or for poor outcomes early in the course of MDD is of critical importance, as they may inform the development of targeted prevention and early intervention strategies.

Despite the recognition of the detrimental outcomes associated with early onset depression, a detailed understanding of the factors that contribute to the onset and early course of MDD in this phase of life is limited. Several studies have suggested that factors such as childhood abuse or neglect, loss of a parent or another loved one, a family history of depression, hormonal changes, anxiety and insomnia are associated with early onset depression (Angold et al., 1999; Brown et al., 1999; Franzen and Buysse, 2008; Hariri et al., 2002; Lovato and Gradisar, 2014; Pine et al., 2001; Warner et al., 1999). In addition, in recent years there has been a growing body of literature on neuroimaging research examining early markers for depression. Several studies have reported associations between depression in young people and structural brain abnormalities, including volumetric abnormalities in the hippocampus (Caetano et al., 2007; MacMaster et al., 2008), amygdala (Rosso et al., 2005), frontal lobe, lateral ventricles (Steingard et al., 1996), pituitary (MacMaster et al., 2006) and deficits in cortical thickness and surface area of frontal and parietal cortices (Hao et al., 2017; Peterson et al., 2009; Schmaal et al., 2017a). Other studies have shown functional brain abnormalities in young MDD subjects in brain systems associated with reward and emotion processing, and cognitive control (Hulvershorn et al., 2011). A meta-analysis on functional neuroimaging of MDD in young people confirmed these difficulties with emotion regulation by showing differences in activation in the subgenual anterior cingulate cortex and thalamus during emotional tasks (Miller et al., 2015). However, most of these neuroimaging studies have employed cross-sectional study designs, limiting the ability to draw conclusions about the cause and effect relationship between these contributing factors and depression. Even when focusing on risk factors of MDD onset, most studies were cross-sectional by comparing low risk versus high risk groups based on e.g. family history (Hao et al., 2017; Luking et al., 2016). In order to elucidate whether structural and functional brain alterations are pre-existing, as vulnerability factors for developing depression, or are the result of stress associated with depressive episodes, longitudinal study designs are required. In addition, investigating the association between longitudinal changes in depressive symptoms and changes in brain function and structure can provide insight into whether brain abnormalities fluctuate with progression and remission of depressive symptoms or remain static.

A number of longitudinal studies have examined associations between neuroimaging measures and onset of or changes in depressive symptoms in childhood or adolescence, which have, to some extent, been summarised in review papers and meta-analyses (Jones et al., 2017; Keren et al., 2018; Luking et al., 2016). However, these previous reviews or meta-analyses mainly focused on specific neuroimaging modalities or processes (e.g. reward processing). In this review, we adopt a multimodal approach and synthesise the evidence across structural and functional neuroimaging studies in youth, thereby providing a more holistic understanding of alterations in brain circuitries that may represent vulnerability factors for the onset of or a poorer course of depression.

2. Methods

2.1. Data sources

This systematic review was performed according to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines (Liberati et al., 2009). A systematic review was chosen over a meta-analysis, since the studies included were too dissimilar in methods (e.g. follow-up time, regions of interest, developmental stages as covariates) and the number of studies were limited. The systematic literature search using PubMed/MEDLINE databases was conducted for studies published up to 1 February 2019. The following key search terms were used: (depression OR depressive OR MDD) AND (follow* OR longitudinal* OR prospective OR baseline OR outcome*) AND (SPECT OR [single photon emission computed tomography] OR spectroscopy OR PET OR [positron emission tomography] OR MRI OR [magnetic resonance imaging] OR DTI OR [diffusion tensor imaging] OR [diffusion weighted imaging] OR fMRI OR [functional magnetic resonance imaging] OR EEG OR electroencephalogram OR neuroimaging) AND (adolescen* OR pediatric* OR paediatric* OR child* OR youth* OR young). Only peer-reviewed studies written in English were included. The protocol was not pre-registered.

2.2. Study selection

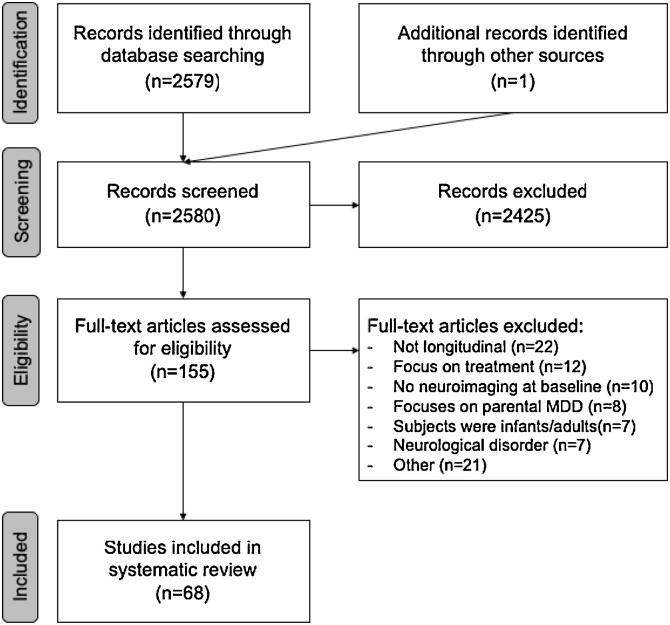

Potentially relevant studies were determined through screening of the title and abstract by YT, as well as LS and LvV, after which the article contents were examined in detail. When LS, LvV and YT disagreed, the articles were discussed and a final decision was made. Studies were included if they had a longitudinal study design with at least two clinical assessments of depression (one at baseline and at least one follow-up assessment) and with at least a neuroimaging assessment at baseline. With regard to the study population, studies were included if the sample included children and/or adolescents (age 5–25) that either developed a first episode of depression or showed changes in (subclinical) depressive symptoms over the follow-up period. Therefore, studies in which a depression diagnosis was present at baseline were also included. Studies were excluded when they involved a clinical trial examining changes in depression in response to treatment as well as studies that included participants with a neurological disorder (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of study selection.

3. Results

3.1. Study characteristics

Sixty-eight studies met our inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). The age of the participants at baseline in the studies ranged from 5 to 25 years. Of note, the majority of these samples were subsamples of 8 larger studies (Supplemental Table 1). As a result of multiple publications from these 8 larger studies and an additional 26 studies with unique samples, a total of 34 distinct samples were included in this review. In total, 26 studies examined structural brain measures (Table 1), 6 studies included DTI (Table 2) and 39 studies focused on functional brain measures (including fMRI and EEG; Table 3). Outcome measures in the studies were defined as either a comparison between a group of participants who remained well (no depression) and a group of participants who developed MDD at follow-up (30 studies), or as a change in depressive symptoms between baseline and follow-up (31 studies), while some studies focused on both outcome measures. The majority of studies examined the association between baseline imaging measures and subsequent onset of MDD or longitudinal changes in depressive symptoms. However, twelve studies also had longitudinal imaging data and examined whether changes in the brain were associated with changes in depressive symptoms. Twenty-four studies included community samples, and the other 44 studies included risk-enriched samples based on a family history of mental disorder, temperament, childhood maltreatment, early psychiatric symptoms or low socioeconomic status (Supplemental Table 1).

Table 1.

Overview of structural brain studies and accompanying characteristics, measures and findings.

| Authors and publication year | Sample name (if available) | N | Baseline age (±SD / range) | Sex (% F) | N MDD at FU | N FU | Last FU (in months) | Neuroimaging measure | Segmentation method: automated or manual tracing | Depression measure | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structural | |||||||||||

| Albaugh et al. (2017) | BDCG | 371 | 12.0 (0.1) (4.8-18.4) |

53 | 0 | 2 | 24 | Hippocampus and Amygdala volume | Automated ANIMAL | CBCL A/D | Higher amygdala volume over time was associated with higher depressive and anxiety symptoms at FU |

| Auerbach et al. (2017) | 50 | 13.0 (0.8) (12-14) |

100 | 0 | 1 | 3 | Striatal volume | FreeSurfer Automated | MFQ | No significant findings and no significant moderation effect of peer feedback | |

| Barch et al. (2019) | PDS | 164 | 10.3 (6.1-12.1) |

51 | 21 | 9 | 86 | Hippocampal volume | FreeSurfer Automated with manual inspection | PAPA, CAPA & KSADS | Lower hippocampal volume (intercept) in past-depressed group compared to HC. No cumulative effect of depression |

| Belden et al. (2015) | PDS | 129 | 9.9 (1.2) (6.1-12.1) |

48 | 24 | 9 | 36 | Anterior insula volume | FreeSurfer Automated with manual inspection | PAPA & CAPA | Smaller right anterior insula volume at baseline was associated with MDD onset |

| Bos et al. (2018) | Braintime | 205 | 13.6 (2.5) (8-20) |

53 | 61 | 2 | 48 | Cortical thickness, surface area, amygdala & hippocampal volume | FreeSurfer Automated | BDI | Higher cortical thinning over time in precentral, paracentral frontal lobe, pars orbitalis and lateral orbitofrontal cortex was associated with increase in depressive symptoms. No significant findings in surface area, hippocampal and amygdala volume |

| Deane et al. (2019) | ADS | 118 | 11.5 (0.4) | 48 | N/A | 3 | 96 | Development of cortical thickness of ACC, OFC, medial FG, pars opercularis, pars orbitalis, pars triangularis, superior FG, frontal pole and volume of hippocampus, amygdala, NAcc, caudate, putamen and pallidum | FreeSurfer Automated with manual inspection | CES-D | No significant findings in interaction with parenting |

| Ducharme et al. (2014) | BDCG | 341 | 11.9 (0.1) (4.9-22.3) |

57 | N/A | 2 | 48 | Cortical thickness of ACC, subgenual ACC & OFC | CIVET pipeline Automated | CBCL | Thinner right ventromedial PFC was negatively associated with depressive symptoms early in life (5-9 years), but positively later (15–22 years) |

| Foland-Ross et al. (2015) | 33 | 13.0 (1.8) (10-15) | 100 | 18 | 3 | 60 | Whole brain cortical thickness | FreeSurfer Automated with manual inspection | K-SADS-PL | SVM 70% accuracy: thinner right medial OFC, thicker left insula at baseline was associated with depression onset at FU | |

| Ganella et al. (2015) | ADS | 91 | 16.5 (0.5) (15-17) |

46 | 9 | 1 | 36 | Pituitary volume | Manual tracing | CES-D | No significant findings |

| Little et al. (2014) | ADS | 125 | 12.7 (0.5) (11.4-13.7) |

52 | 36 | 3 | 72 | Hippocampus, Amygdala, ACC & OFC | Manual tracing ANALYZE | K-SADS-PL | Larger left rostral limbic ACC, smaller left hippocampus, and larger right hippocampus at baseline was associated with depression onset at FU. Smaller left hippocampus at baseline also mediated the association between 5-HTTLPR genotype and depression onset |

| Little et al. (2015) | ADS | 123 | 12.7 (0.5) (11.4-13.7) |

52 | 36 | 3 | 72 | Hippocampal volume | Manual tracing | K-SADS-PL | In those with high-level parental aggression or low-level positive parenting: smaller left and right hippocampal volume at baseline mediated association between S-allele 5-HTTLPR and depression onset |

| Luby et al. (2017) | PDS | 119 | 9.7 (1.3) (6.1-12.9) |

48 | N/A | 2 | 36 | PFC subregion volumes | FreeSurfer Automated with manual inspection | PAPA | Smaller IFG volume at baseline mediated association between higher adverse childhood experiences and increased depressive symptoms at FU |

| Luby et al. (2018) | PDS | 175 | 9.7 (1.3) (6.1-12.9) |

48 | 16 | 3 | 36 | Striatal volume, OFC volume & thickness | FreeSurfer Automated | CIDI | No significant findings |

| Nickson et al. (2016) | BFS | 83 HR 48 HC |

20.8 (2.8) (16–25) |

54 | 30 | 2 | 58 | Whole brain volume and ROI: amygdala, hippocampus & ACC | VBM (FSL) Automated | SCID, HAM-D & K-SADS-PL | Larger amygdala volume at baseline and less amygdala growth was associated with depression onset at FU |

| Pagliaccio et al. (2014) | PDS | 60 | 9.8 (8–12) |

45 | N/A | 1 | 18 | Hippocampus, amygdala & insula volume | FreeSurfer Automated with Automated inspection | CDI-C & interview | No significant findings |

| Papmeyer et al. (2015) | BFS | 114 HR 93 HC |

21.1 (2.8) (16–25) |

54 | 19 | 1 | 24 | Cortical thickness | FreeSurfer Automated with Automated inspection | SCID, HAM-D | Thinner right para-hippocampal gyrus, increases in thickness over time of left precentral gyrus and left IFG over time was associated with depression onset |

| Papmeyer et al. (2016) | BFS | 114 HR 93 HC |

21.1 (2.8) (16–25) |

54 | 19 | 1 | 24 | Ventricles, striatum, hippocampus, thalamus & amygdala volume | FreeSurfer Automated with manual inspection | SCID, HAM-D | No significant findings |

| Rao et al. (2010) | SUD | 21 HR 31 HC | 15.1 (1.7) (12–20) |

34 | 8 | 10 | 60 | Hippocampal volume | Manual tracing AFNI | K-SADS-PL & LIFE | Smaller hippocampal volumes at baseline mediated the association between early life adversity and having a depressive episode at FU |

| Schmaal et al. (2017b) | ADS | 149 | 12.5 (12-19) |

49 | 25 | 3 | 72 | Amygdala and hippocampus volume and OFC, ACC, IFG, dPFC thickness & surface area | FreeSurfer Automated with manual inspection | CES-D | Lower ACC surface area at baseline associated with an early-decreasing symptom course trajectory in females. Right OFC surface area increased over time in males with low-stable and late-increasing symptom trajectories. Lower bilateral OFC surface area in group with early-decreasing symptoms. |

| Shapero et al. (2019) | 44 | 11.0 (1.7) (8-14) |

45 | 12 | 1 | 47 | Amygdala volume | FreeSurfer Automated | KSADS-E, CBCL & CDI | No significant findings | |

| Vijayakumar et al. (2014) | ADS | 92 | 12.7 (0.4) (11.4-14.1) | 51 | 16 | 1 | 45 | Thickness ACC, dlPFC & vlPFC | FreeSurfer Automated | CES-D | Interaction between change in effortful control during FU and less left ACC thinning over time on reduction depressive symptoms at FU |

| Vijayakumar et al. (2017) | ADS | 166 | (11-20) | 49 | 19 | 2 | 72 | Amygdala volume & cortico-amygdala maturational coupling | FreeSurfer and SurfStat Automated with manual inspection | CES-D | Similar developmental trajectory in the amygdala and left anterior PFC was associated with reduction in depressive symptoms at FU. Development trajectory of the amygdala only was not associated with changes in depressive symptoms. |

| Vulser et al. (2015) | IMAGEN | 351 | 14 (0.4) (12.9-15.7) |

70 | 0 | 1 | 24 | Whole brain volume | VBM Automated | DAWBA, ADRS | Smaller mPFC volume at baseline mediated transition from subthreshold depression to clinical MDD in females |

| Whittle et al. (2011) | ADS | 114 | 12.6 (0.5) (11.4-13.7) |

49 | 7 | 1 | 30 | Hippocampal volume | Manual tracing ANALYZE | K-SADS-E & CES-D | Interaction larger bilateral hippocampus at baseline and maternal aggressive behaviour on increase in depressive symptoms in females |

| Whittle et al. (2012) | ADS | 141 | 12.7 (0.5) (11.4-13.7) | 46 | N/A | 1 | 31 | Pituitary volume | Manual tracing ANALYZE | CES-D | Larger pituitary gland volume at baseline mediated the association between early pubertal timing and increase in depressive symptoms |

| Whittle et al. (2014) | ADS | 86 | 12.6 (11.4-13.7) |

48 | 30 | 3 | 72 | Volume of hippocampus, amygdala & striatum. Thickness of prefrontal regions | FreeSurfer Automated with manual inspection | K-SADS-PL | Less hippocampal growth over time and less putamen reduction was associated with depression onset. Smaller baseline NAcc volumes and greater amygdala growth over time in females was associated with depression onset |

Abbreviations: ACC: anterior cingulate cortex, ADRS: adolescent depression rating scale, ADS: orygen adolescent depression study, BDCG: brain development cooperative group, BDI: beck depression inventory, BFS: bipolar family study, CAPA: childhood and adolescent psychiatric assessment, CBCL: child behavior checklist, CDI: children’s depression inventory, CES-D: center for epidemiological studies – depression scale, CIDI: composite international diagnostic interview, F: female, FG: frontal gyrus, FU: follow-up, HAM-D: hamilton depression rating scale, HC: healthy controls, HR: high risk, IFG: inferior frontal gyrus, IMAGEN: European cohort on development, KSADS-E: schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-aged children (epidemiologic version), KSADS-PL: schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-aged children (present and lifetime version), LIFE: longitudinal interval follow-up evaluation, MDD: major depressive disorder, MFQ: mood and feelings questionnaire, mPFC: medial PFC, N: number of, NAcc: nucleus accumbens, OFC: orbitofrontal cortex, PAPA: preschool-age psychiatric assessment, PDS: pre-school depression study, PFC: prefrontal cortex, ROI: region of interest, SCID: structured clinical interview for DSM-IV, SD: standard deviation, SUD: substance use and depression study, SVM: support vector machine learning model, VBM: voxel-based morphometry, vlPFC: ventrolateral PF, 5-HTTLPR: serotonin transporter linked polymorphic region.

Table 2.

Overview of DTI studies and accompanying characteristics, measures and findings.

| Authors and publication year | Sample name | N | Baseline age (±SD / range) | Sex (% F) | N MDD at FU | N FU | Last FU (in months) | Neuroimaging measure | Depression measure | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DTI | ||||||||||

| Bick et al. (2017) | BEIP | 69 | 8.6 (0.4) (8-10) |

46 | N/A | 1 | 48 | TBSS | HBQ | Teacher reported depression at FU was positively associated with RD in the external capsule and negatively with FA in the body of the CC at baseline |

| Ganzola et al. (2017) | BFS | 69 HR 43 HC | 21.6 (2.9) (16-25) |

57 | 16 | 2 | 24 | TBSS | SCID & HAM-D | No significant findings |

| Ganzola et al. (2018) | BFS | 106 HR 61 HC | 21.4 (2.7) (16-25) |

53 | 28 | 2 | 24 | TBSS | SCID & HAM-D | No significant findings |

| Huang et al. (2012) | SUD | 19 HR 13 HC |

15.9 (2.8) | 66 | 6 | 10 | 42 | VBM and TBSS | K-SADS-PL & LIFE | Lower FA values in left and right superior longitudinal fasciculus and right cingulum hippocampus at baseline were associated with depression onset at FU |

| Jalbrzikowski et al. (2017) | 246 | (10-25) | 49 | N/A | 3 | 45 | Tractography vmPFC-amygdala | YSR | Higher centromedial amygdala to anterior vmPFC quantitative anisotropy during late childhood were associated with depressive symptoms over time | |

| Vulser et al. (2018) | IMAGEN | 81 | 14.5 (0.4) | 64 | 8 | 1 | 24 | TBSS and tractography | DAWBA | 21% of the transition from subthreshold to MDD was explained by lower FA in the anterior corpus callosum to ACC at baseline |

Abbreviations: ACC: anterior cingulate cortex, BEIP: bucharest early intervention project, BFS: bipolar family study, CC: corpus callosum, DAWBA: developmental and well-being assessment interview, DTI: diffusion tensor imaging, F: female, FA: fractional anisotropy, FU: follow-up, HAM-D: hamilton depression rating scale, HBQ: health behavior questionnaire, HC: healthy controls, HR: high risk, K-SADS-PL: schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-aged children (present and lifetime version), MDD: major depressive disorder, MFQ: mood and feelings questionnaire, N: number of, RD: radial diffusion, SCID: structured clinical interview for DSM-IV, SD: standard deviation, TBSS: tract-based spatial statistics, VBM: voxel-based morphometry, vmPFC: ventromedial PFC, YSR: youth self-report.

Table 3.

Overview of functional imaging studies and accompanying characteristics, measures and findings.

| Authors and publication year | Sample name | N | Baseline age (±SD / range) | Sex (% F) | N MDD at FU | N FU | Last FU (in months) | Neuro imaging measure | Depression measure | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Function | ||||||||||

| Bertocci et al. (2016) | LAMS | 41 | 13.3 (1.9) | 44 | 9 | 1 | 21 | fMRI Emotional N-back task, ROIs: amygdala, dorsolateral PFC, dorsal ACC & vlPFC | KSADS, CBCL | Elastic net regression: Increased amygdala and left vlPFC activity over time was associated with depressive symptoms over time |

| Blackhart et al. (2005) | 28 | 18.8 (1.0) (18-25) |

82 | N/A | 1 | 12 | Resting state EEG, ROIs: anterior & parietotemporal alpha asymmetry | BDI | No significant findings | |

| Bress et al. (2013) | 68 | 16.0 (15-17) |

100 | 16 | 1 | 21 | EEG Reward processing, ROIs: Fz and FCz | DISC | Blunted feedback negativity ERP (loss minus gain) at baseline was associated with depression onset | |

| Bress et al. (2015) | 45 | 10.7 (8-13) |

43 | N/A | 2 | 24 | EEG Reward processing, ROI: FCz | CDI-SR | Blunted feedback negativity ERP (loss minus gain) at baseline was associated with depressive symptoms | |

| Callaghan et al. (2017) | ADS | 101 | 16.5 | 51 | 14 | 2 | 36 | rsfMRI FC amygdala, VS & NAcc | K-SADS-PL | Higher amygdala – temporal and insula FC at baseline mediated the association between maternal aggression and depression onset |

| Casement et al. (2016) | 123 | 16 | 100 | 2 | 1 | 12 | fMRI Reward processing, ROIs: striatum, amygdala, mPFC & OFC | K-SADS | Higher activity in subregion dorsomedial PFC at baseline modulated effect of early life sleep disturbances on increases in depressive symptoms at FU | |

| Chan et al. (2016) | BFS | 54 HC 73 HR | 23.0 (2.4) (16-25) |

56 | 30 | 1 | 24 | fMRI Emotion processing, ROIs: amygdala, hippocampus & ACC | SCID & HAM-D | Lower subgenual ACC response to angry faces at baseline was associated with depression onset |

| Connolly et al. (2017) | 24 | 16.1 (1.3) | 40 | 24 | 1 | 3 | rsfMRI FC of amygdala | CDRS-R | Higher right amygdala - orbital middle FG connectivity and lower right amygdala - bilateral insula connectivity at baseline were associated with increased depressive symptoms at FU | |

| Davey et al. (2015) | ADS | 56 | 16.5 (0.5) | 45 | 8 | 1 | 24 | rsfMRI FC of amygdala | K-SADS-PL & CES-D | Increase amygdala – subgenual ACC connectivity over time was associated with depression onset |

| Dennison et al. (2016) | 51 | 17.0 (1.4) (13-20) |

61 | N/A | 1 | 23 | fMRI Emotion regulation, ROI: striatum | DISC-IV | Lower putamen activity to reward outcome at baseline moderated association of childhood maltreatment with increases of depressive symptoms | |

| Gollier-Briant et al. (2016) | IMAGEN | 685 | 14.5 (0.5) (13-15) |

54 | N/A | 1 | 24 | fMRI Emotion regulation, whole brain and ROIs: cingulate gyrus, hippocampal gyrus, frontal gyri, temporal gyri | DAWBA | No significant findings |

| Hanson et al. (2015) | SUD | 106 | 13.7 (11.9-15.5) |

48 | 9 | 1 | 25 | fMRI Reward processing, ROI: VS | Child-report version of the MFQ |

Less change in reward-related VS activity over time mediated the effect of emotional neglect on increase in depressive symptoms |

| Jalbrzikowski et al. (2017) | 246 | (10-25) | 49 | N/A | 3 | 45 | rsfMRI FC between vmPFC & amygdala | YSR | Higher right CM amygdala to rostral ACC connectivity in early adulthood was associated with an increase in depressive symptoms | |

| Jin et al. (2017) | ADEPT | 229 | 15.3 (0.6) | 100 | N/A | 2 | 9 | fMRI Reward processing, FC of OFC | IDAS-II | Higher OFC-insula FC and reduced OFC during loss at baseline was associated with an increase in depressive symptoms, especially when the parents had a history of depression |

| Langenecker et al. (2018) | 109 | 21.0 (1.5) (18-23) |

63 | 21 | 2 | 12 | fMRI Cognitive control (parametric go/no-go task) whole brain | DIGS | Lower activation in middle FG during unsuccessful cognitive control in the group with subsequent recurrence of depression. Higher activation after rejection in left subgenual ACC and amygdala. Lower connectivity within and outside cognitive control network, and to the salience network, in recurrence group | |

| Levinson et al. (2018) | 143 | 12.9 (1.6) (8-14) |

100 | N/A | 1 | 12 | EEG Emotional stimuli | CDI | Blunted LPP at baseline mediated the effect of negative life events on increase in depressive symptoms | |

| Lichenstein et al. (2017) | PMCP | 158 | 20 | 0 | N/A | 1 | 24 | fMRI Reward processing, FC between NAcc and mPFC | BDI | Lower NAcc - mPFC connectivity at baseline was associated with higher depressive symptoms |

| Lopez et al. (2018) | PDS | 143 | 11.3 (1.2) (9-14) |

66 | N/A | 2 | 54 | rsfMRI, FC of dlPFC, amygdala, insula, vmPFC, dorsal ACC & vlPFC | CDI-C | Higher right dlPFC-dACC connectivity was associated with an increase in depressive symptoms, which was not significant after correction for baseline depression |

| Maciejewski et al. (2018) | 138 | 13.5 (0.5) (13-14) |

48 | N/A | 2 | 24 | fMRI Cognitive control task, ROIs: left posterior medial frontal cortex, IFG, inferior parietal lobes, right insula, right superior frontal gyrus & left middle frontal gyrus | CBCL, YSR | Lower neural control (activation in ROIs) at baseline was associated with higher depressive symptoms at FU when more negative life events were experienced | |

| Masten et al. (2011) | 20 | 12.9 ( 12.4-13.6) |

65 | N/A | 1 | 14 | fMRI Peer rejection task, whole brain and ROI: subgenual ACC | CBCL (parent) | Higher subgenual ACC activation during peer rejection at baseline was associated with an increase in depressive symptoms | |

| Mattson et al. (2016) | PMCP | 156 | 20 | 0 | 20 | 1 | 24 | fMRI Emotion processing, ROI: amygdala | BDI-II | Higher amygdala activity to neutral faces than non-faces at baseline was associated with depressive symptoms at FU |

| Meyer et al. (2018) | ADEPT | 457 | 14.4 (0.6) (13.5-15.5) | 100 | 49 | 1 | 18 | EEG Error related Flanker task | KSADS-PL, IDAS-II | No significant findings |

| Mitchell et al. (2011) | 41 | 13.9 (0.6) | 0 | N/A | 1 | 12 | Resting state EEG | DSQ, SBB-DES | Higher right medial-frontal region activity at baseline was associated with higher depressive symptoms at FU | |

| Morgan et al. (2013) | 72 | F: 11.5 (0.6) M: 12.4 (0.6) (11-13) | 56 | N/A | 1 | 24 | fMRI Reward processing, ROIs: striatum & mPFC |

MFQ | Lower caudate response during reward anticipation in those in mid/late puberty (n = 40) at baseline was associated with an increase in depressive symptoms. Higher ACC and OFC response to reward outcome in males was associated with an increase in depressive symptoms | |

| Nelson et al. (2016) | ADEPT | 444 | 14.4 (0.6) (13.5-15.5) | 100 | 40 | 1 | 18 | EEG Reward processing task, ROI: FCz electrode | K-SADS-PL & SCID & IDAS | Blunted reward positivity ERP at baseline was associated with depression onset |

| Nelson et al. (2018) | ADEPT | 444 | 14.4 (0.6) (13.5-15.5) | 100 | 40 | 1 | 18 | EEG Reward processing task, ROI: FCz electrode | K-SADS-PL & SCID & IDAS | Blunted reward related ERP during delta waves at baseline was associated with depression onset |

| Nusslock et al. (2011) | LIBS | 40 | 20.3 (1.3) | 43 | 13 | 9 | 36 | Resting state EEG asymmetry | BDI, SADS-C | Lower relative left-frontal activity at baseline was associated with depression onset |

| Pagliaccio et al. (2014) | PDS | 60 | 9.8 (8-12) |

45 | N/A | 1 | 18 | fMRI Emotion processing, FC of amygdala & dorsal frontal and parietal regions | CDI-C & interview | No significant findings |

| Pan et al. (2017) | HRC | 585 | 10.6 (1.9) (6-12) |

48 | 56 | 1 | 36 | rsfMRI FC in reward network | DAWBA | Higher left VS (connected to ACC, PFC, thalamus, VTA) node strength in reward network at baseline was associated with depression onset |

| Possel et al. (2008) | 80 | 13.9 (0.6) | 44 | 6 | 1 | 12 | Resting state EEG | DSQ, SBB-DES | Medial-frontal and medial-parietal alpha asymmetry at baseline was associated with depression onset | |

| Scheuer et al. (2017) | 37 | 13.5 (1.5) (12-16) |

57 | N/A | 1+ | 54 | rsfMRI FC of amygdala | CDI | Lower right amygdala - left IFG connectivity and supramarginal gyri - mid-cingulate cortex and higher left amygdala - left cerebellar vermis connectivity at baseline were associated with increase in depressive symptoms over time | |

| Shapero et al. (2019) | 44 | 11.0 (1.7) (8-14) |

45 | 12 | 1 | 47 | rsfMRI, FC of the 5 connections that explains most variance of the total resting state networks (i.e. default mode network - supramarginal, right dlPFC - brodmann area 46, left dlPFC - middle FG, left dlPFC - inferior temporal gyrus, right dlPFC - ba40) fMRI Emotion processing, whole brain |

KSADS-E, CBCL, CDI | Resting state variables at baseline predicted MDD outcome (55% sensitivity, 86% selectivity) Emotion: total voxels in response to fear or happy vs neutral was associated with reduction depressive symptoms |

|

| Stewart et al. (2018) | 54 | 18.8 (0.8) | 70 | N/A | 1 | 12 | Resting state EEG asymmetry | SCID, BDI-II | Lower left than right frontal EEG activity at baseline in females was associated with depressive symptoms at FU | |

| Strikwerda-Brown et al. (2015) | ADS | 56 | 16.5 (0.6) | 46 | 11 | 1 | 24 | rsfMRI, FC of subgenual ACC | CES-D | Lower subgenual ACC connectivity to dorsomedial PFC, posterior cingulate cortex, left middle temporal gyrus and right angular gyrus over time was associated with depressive symptoms at FU |

| Stringaris et al. (2015) | IMAGEN | 999 | 14.4 (0.4) | 51 | 29 | 1 | 24 | rsfMRI Reward processing, ROIs: caudate, putamen, rectus, insula, olfactory, amygdala, hippocampus, cingulum, cingulate cortex & OFC | DAWBA & ADRS | Transition HC to subthreshold depression: lower VS activity at baseline. Transition HC to clinical depression: lower VS and left middle superior frontal gyrus activity at baseline |

| Telzer et al. (2014) | 39 | 16.3 (15-17) |

59 | N/A | 1 | 12 | fMRI Reward processing, ROI: VS | CBCL | Higher VS activation during donation at baseline was associated with reductions in depressive symptoms over time, but during risk taking it was associated with increases in depressive symptoms over time. | |

| Vilgis et al. (2018) | PGS | 78 | 16 | 100 | N/A | 1 | 12 | fMRI Emotion processing, ROIs: vmPFC & dmPFC | ASI-4 | Higher dmPFC activity at baseline was associated with a decrease in depressive symptoms |

| Whalley et al. (2013) | BFS | 98 HR 58 HC | 20.8 (2.9) (16-25) |

51 | 20 | 1 | 24 | fMRI Executive functioning, whole brain | SCID | Higher activation bilateral insula at baseline was associated with depression onset |

| Whalley et al. (2015) | BFS | 50 HR | 23.5 (2.6) (16-25) |

46 | 11 | 2 | 48 | fMRI Emotion processing, ROIs: thalamus, insula, ACC, amygdala & hippocampus |

SCID, HAM-D | Higher activity in thalamus, insula & ACC in response to positive emotion and lower thalamus and ACC activity in response to neutral condition at baseline were associated with depression onset |

Abbreviations: ACC: anterior cingulate cortex, ADEPT: adolescent development of emotions and personality traits, ADRS: adolescent depression rating scale, ADS: orygen adolescent depression study, BDI-II: beck depression inventory, BFS: bipolar family study, CBCL: child behavior checklist, CDI: children’s depression inventory, CES-D: center for epidemiological studies – depression scale, CDRS-R: children's depression rating scale - revised, DAWBA: developmental and well-being assessment interview, DIGS: diagnostic interview for genetic studies, DISC: diagnostic interview schedule for children, dlPFC: dorsolateral PFC, DSQ: depression screening questionnaire, EEG: electroencephalogram, F: female,] FC: functional connectivity, FCz: mid-frontal electrode EEG, FG: frontal gyrus, fMRI: functional magnetic resonance imaging, FU: follow-up, Fz: midline electrode EEG, HAM-D: hamilton depression rating scale, HC: healthy controls, HR: high risk, HRC; high risk cohort, IDAS: inventory of depressive and anxiety symptoms, IFG: inferior frontal gyrus, IMAGEN: European cohort studying development, K-SADS-E: schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-aged children (epidemiologic version), K-SADS-PL: schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-aged children (present and lifetime version), LAMS: longitudinal assessment of mania symptoms study, LIBS: longitudinal investigation of bipolar spectrum, LPP: late positive potential, MDD: major depressive disorder, MFQ: mood and feelings questionnaire, mPFC: medial PFC, N: number of, NAcc: nucleus accumbens, OFC: orbitofrontal cortex, PAPA: preschool-age psychiatric assessment, PDS: pre-school depression study, PFC: prefrontal cortex, PMCP: pittsburgh mother & child project, ROI: region of interest, RS: resting state, SADS-C: schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia – change, SBB-DES: self-rating questionnaire for depressive disorders, SCID: structured clinical interview for DSM-IV, SD: standard deviation, SUD: substance use and depression study, vlPFC: ventrolateral PFC, vmPFC: ventromedial PFC, VS: ventral striatum, VTA: ventral tegmental area, YSR: youth self-report.

3.2. Brain structure

3.2.1. Hippocampal volume

3.2.1.1. Association between baseline imaging and MDD onset or changes in depressive symptoms

Two studies (from the bipolar family study (BFS) a risk-enriched sample; age 16–25) reported no effect of hippocampus volume on subsequent onset of MDD (Nickson et al., 2016; Papmeyer et al., 2016). However, baseline hippocampal volume was found to mediate the effect of childhood trauma, genotype, and parental aggressive behaviour on MDD onset (Little et al., 2015, 2014; Rao et al., 2010), suggesting hippocampal volume may play a role in onset of adolescent MDD in specific subgroups. Studies including the risk-enriched Orygen Adolescent Depression Study (ADS) sample (Table 1), showed an association between smaller left, but larger right hippocampal volume at age 11–13 (Little et al., 2014), as well as reduced hippocampal growth between age 12 and 16 (Whittle et al., 2014), and onset of MDD within 6 years of follow-up. Baseline hippocampal volume was also not associated with changes in depressive symptoms in children (age 8–12) (Pagliaccio et al., 2014). In females, an interaction effect between larger baseline bilateral hippocampus and maternal aggressive behaviour on increases in depressive symptom severity were found (Whittle et al., 2011).

3.2.1.2. Association between longitudinal changes in imaging and changes in depressive symptoms

In four different samples a change in hippocampal volume over time was not associated with changes in depressive symptoms (age range 5–18, 6–12, 8–20 and 12–19) (Albaugh et al., 2017; Barch et al., 2019; Bos et al., 2018; Schmaal et al., 2017b) and there was no interaction effect between hippocampal volume change and maternal parenting behaviour on changes in depressive symptoms over time (Deane et al., 2019). However, depression prior to baseline was associated with lower hippocampal volume at baseline (Barch et al., 2019).

3.2.2. Amygdala volume

3.2.2.1. Association between baseline imaging and MDD onset and changes in depressive symptoms

In three studies of samples aged 8–14, 11–14 and 16–25 years, no association between baseline amygdala volume and subsequent onset of MDD was reported (Little et al., 2014; Papmeyer et al., 2016; Shapero et al., 2019). However, two other studies found that larger amygdala volumes at baseline (age 16–25) (Nickson et al., 2016) and greater amygdala volume growth between age 12 and 16 in females only (Whittle et al., 2014) were associated with onset of depression. No significant associations were found in the only study that examined the association between baseline amygdala volume and subsequent changes in depressive symptoms in children (age 8–12) (Pagliaccio et al., 2014).

3.2.2.2. Association between longitudinal changes in imaging and changes in depressive symptoms

Three studies showed that longitudinal changes in amygdala volume were not associated with changes in depressive symptoms over time and it did not mediate the effect of maternal behaviour on depressive symptoms (Bos et al., 2018; Deane et al., 2019; Schmaal et al., 2017b). Only one study did find a positive association between amygdala volume change and changes in anxiety and depressive symptoms over a two-year follow-up period (Albaugh et al., 2017).

3.2.3. Pituitary gland volume

3.2.3.1. Association between baseline imaging and changes in depressive symptoms

Two studies in the same sample found diverging results for different developmental stages. In adolescents aged 11–14 years, larger pituitary gland volume at baseline was associated with higher self-reported depressive symptomatology at 2.5-year follow-up, and mediated the relationship between early pubertal timing at baseline and depressive symptoms at follow-up (Whittle et al., 2012). In contrast, pituitary gland development from age 16 to 19 was not associated with depressive symptoms at age 19 (Ganella et al., 2015).

3.2.4. Striatal volume

3.2.4.1. Association between baseline imaging and MDD onset or changes in depressive symptoms

In a prospective study in the ADS sample, smaller volume of the nucleus accumbens across age 12 to 16 was reported to have an association with MDD diagnosed at age 18 in females (Whittle et al., 2014). Putamen and caudate volumes at baseline were not associated with the onset of a first depressive episode during follow-up in sample with a risk enriched sample because of family history of bipolar disorder (Papmeyer et al., 2016). Transition from subthreshold to full-blown depression was also not mediated by baseline caudate volume in a largecommunity sample (IMAGEN) (Vulser et al., 2015). Moreover, baseline striatal volume at age 6–12 was not associated with changes in depressive symptoms at 3-year follow-up (Luby et al., 2018) and not associated with depressive symptoms at 3-month follow-up in 12-14-year-old girls (Auerbach et al., 2017).

3.2.4.2. Association between longitudinal changes in imaging and changes in depressive symptoms

Developmental changes in striatal volume between age 12 and 18 in interaction with baseline maternal behaviour was not associated with depressive symptoms at age 18 (Deane et al., 2019).

3.2.5. Cortical volumes and thickness

3.2.5.1. Association between baseline imaging and MDD onset or changes in depressive symptoms

Larger rostral anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) volume at age 11–14 was associated with onset of MDD within a 6-year follow-up period (Little et al., 2014), while thickness or volume in the same region at age 16–25 was not associated with the subsequent onset of MDD in risk-enriched samples (Papmeyer et al., 2015; Nickson et al., 2016). In risk-enriched samples an association was shown between thinner baseline parahippocampal gyrus and onset of MDD within two-year follow-up (Papmeyer et al., 2015), between smaller right anterior insula volume at age 6–12 and subsequent MDD onset (Belden et al., 2015), and between smaller inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) at baseline (age 6–12) and increased severity of depression symptoms at 3-year follow-up, which was partly mediated by adverse childhood experiences (Luby et al., 2017). In a large community sample from the IMAGEN study, transition from subthreshold to a full clinical depression was predicted by lower baseline medial prefrontal cortex volume (PFC), including the left ventromedial PFC (vmPFC) and right rostral ACC, in females only (Vulser et al., 2015). The role of alterations in these lateral and medial prefrontal regions and temporal regions in predicting subsequent onset of MDD was further confirmed in a study in females (baseline age 10–15), in which a machine learning model could discriminated between females that did or did not develop a depressive disorder within 5 years of follow-up with 70% accuracy based on cortical thickness alterations (Foland-Ross et al., 2015), with the medial orbitofrontal gyrus (OFC), lateral OFC, precentral gyrus, insula, rostral ACC, and inferior and superior temporal gyri contributing most strongly to this classification. Nonetheless, three other studies did not find evidence for significant associations between baseline medial and lateral OFC volumes and thickness and subsequent onset of MDD or changes in depressive symptoms in two risk-enriched samples (baseline age ranges 6–12 and 11–13) (Little et al., 2014; Luby et al., 2018; Pagliaccio et al., 2014).

3.2.5.2. Association between longitudinal changes in imaging and changes in depressive symptoms

In a community sample, greater cortical thinning in precentral, paracentral frontal lobe, IFG and lateral OFC was associated with greater increases in depressive symptoms across ages 8–20 (Bos et al., 2018). However, in a risk-enriched sample (family history of BD; baseline age 16–25) greater increases in thickness of precentral gyrus and IFG over time, were associated with the onset of MDD within two-year follow-up (Papmeyer et al., 2015). In another risk-enriched sample based on temperament, in females, consistently lower ACC and OFC surface area across 3 neuroimaging assessments during adolescence (age 12–19) was associated with having high depressive symptom severity in early adolescence (Schmaal et al., 2017b). In contrast, in males, a lack of OFC surface area expansion was observed in those with high depressive symptom severity in early adolescence compared to those with no depressive symptoms and those that developed depressive symptoms later in adolescence. In the same sample, a smaller decrease of effortful control -the ability to manage attention- between baseline (age 11–14) and 4-year follow-up mediated the relationship between reduced ACC thinning and a decrease in depressive symptoms (Vijayakumar et al., 2014). Thinner right ventromedial PFC, including the subgenual ACC, OFC and gyrus rectus, was negatively associated with depressive and anxiety symptoms in early life (<9 years), but positively later in adolescence (15–22 years), which was driven by reduced cortical thinning associated with depressive symptom increases over time (Ducharme et al., 2014).

3.2.6. White matter integrity

3.2.6.1. Association between baseline imaging and MDD onset or changes in depressive symptoms

Four studies employed diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) to study baseline fractional anisotropy (FA), a metric of white matter microstructure sensitive to white matter disruptions, in relation to the onset of MDD or increases in depressive symptoms. Among adolescents exposed to childhood maltreatment, those who subsequently developed MDD had lower baseline (age 16) FA values in the superior longitudinal fasciculus, connecting cortical areas, and the right cingulum-hippocampus projection, connecting the cingulate cortex, hippocampus and prefrontal areas, compared to those who did not develop MDD (Huang et al., 2012). However, these findings could not be replicated in a larger sample of adolescents (aged 16–25) with a family history of bipolar disorder (Ganzola et al., 2018) and no association between FA in the cingulum tract and transition to MDD in young people with subclinical depression at baseline was observed (Vulser et al., 2018). Lower baseline (age 14) FA in the anterior corpus callosum were predictive of transition to MDD in young people with subclinical depression at baseline (Vulser et al., 2018) and MD and FA in the body of the corpus callosum at age 8–10 was negatively associated with increases in depressive symptoms during 4-year follow-up (Bick et al., 2017). Depressive symptoms at follow-up were also positively associated with baseline higher mean diffusion (MD), a measure for the total diffusion per voxel, in the external capsule (Bick et al., 2017).

3.2.6.2. Association between longitudinal changes in imaging and changes in depressive symptom

In adolescents and young adults (aged 16–25) with a family history of bipolar disorder, changes in whole brain FA were not associated with subsequent onset of MDD over a two-year period (Ganzola et al., 2017). Interestingly, in a large community sample (N = 246), greater white matter integrity in a tract connecting the amygdala with anterior vmPFC was associated with depressive and anxiety symptoms in late childhood (aged 10–12), whereas this association was no longer present in adulthood (Jalbrzikowski et al., 2017).

3.2.7. Summary structural studies

Findings from structural MRI studies were mostly inconsistent. The hippocampus has been one of the most studied regions, but across studies no consistent evidence was found for a role of baseline hippocampal volumes or longitudinal changes in hippocampal volumes and the onset of MDD or changes in depressive symptoms. A few studies showed interaction effects between hippocampal volumes and childhood trauma, genotype, and parental behaviour, suggesting that the hippocampus may play a role in onset of MDD in specific subgroups, however, caution is warranted since sample sizes were generally small. For other subcortical regions including the amygdala, caudate nucleus and putamen, results were also inconsistent, with again the majority of studies showing no associations. Preliminary evidence exists for a role of the nucleus accumbens and pituitary gland in the onset of MDD, with the latter depending on pubertal timing. With regard to cortical regions, lateral and medial prefrontal regions (lateral and medial OFC, IFG, rostral ACC, insula) and temporal regions (parahippocampal gyrus, inferior and superior temporal gyri) have been implicated in future onset of MDD or increase in depressive symptoms, with some conflicting findings for the OFC. Moreover, developmental changes in OFC and ACC (reduced thinning or reduced surface area expansion) were also associated with an increase in depressive symptoms in risk enriched and community samples. It is important to note that there was considerable between-study variation in processing methods (e.g., FreeSurfer, VBM or manual tracing). Nonetheless, results were consistent across manual tracing and automated segmentation. Very few studies have investigated white matter microstructure and only an association between lower baseline FA in the corpus callosum and subsequent onset of MDD or increases in depressive symptoms was replicated in two studies.

3.3. Brain function

3.3.1. Task-related: reward processing

3.3.1.1. Association between baseline imaging and MDD onset or changes in depressive symptoms

An association between blunted activity in the ventral striatum (VS), as well as increased functional connectivity between the VS and medial PFC, during reward processing in adolescence or early adulthood and subsequent onset of subthreshold or clinical depression, or increases in depressive symptoms, has been reported in multiple studies, including in a well-powered community samples (N = 158–1000) (Stringaris et al., 2015; Lichenstein et al., 2017) and a high-risk sample (Hanson et al., 2015). These findings are further consistent with electroencephalography (EEG) studies, which showed that in females aged 8–17, blunted response to reward in a fronto-central event-related potential (ERP) was a significant predictor of depression onset or increased symptoms at 1.5 to 2-year follow-up (Bress et al., 2013, 2015; Nelson et al., 2016), which may be specific to the delta frequency (<3 Hz) (Nelson et al., 2018). Nonetheless, using a different fMRI paradigm, one study found that greater instead of blunted VS activation during uncertain risky rewards was related to longitudinal increases in depressive symptoms, whereas greater VS activation during reward was associated with reduced depressive symptoms (Telzer et al., 2014). Reduced dorsal striatal activity when anticipating rewards predicted greater increases in depressive symptoms over two years, but only for adolescents in mid to late pubertal stages but not those in pre to early puberty (Morgan et al., 2013). In addition, higher ACC, dorsomedial PFC (dmPFC) and vmPFC activity, as well OFC-insula connectivity, during reward processing at ages 15–16 were associated with increases in depressive symptoms during follow-up (Casement et al., 2016; Jin et al., 2017; Morgan et al., 2013; Stringaris et al., 2015), with baseline dmPFC activation mediating the association between early life sleep disturbances and higher self-reported depressive symptoms at 1-year follow-up (Casement et al., 2016) and higher vmPFC activity only observed in men (Morgan et al., 2013). In contrast, decreased OFC activity in response to monetary loss in 15-year-olds was reported to predict depressive symptoms 9 months later, especially if one of their parents had a history of depression (Jin et al., 2017).

3.3.2. Task-related: emotion processing

3.3.2.1. Association between baseline imaging and MDD onset or changes in depressive symptoms

Various studies implicate a role of ACC activity in response to emotional facial expressions in onset of or increases in depressive symptoms at follow-up. For example, in a risk-enriched sample, reduced activation of the subgenual ACC in response to angry faces (Chan et al., 2016) and dorsal ACC in response to neutral faces (Whalley et al., 2015) was observed in adolescents that subsequently developed MDD. In contrast, in 13-15-year-olds, increased subgenual ACC activation during social rejection was associated with depressive symptoms reported by the parent one year later (Masten et al., 2011). Furthermore, putamen activity in response to positive images mediated the relationship between childhood maltreatment and increases in depressive symptoms in adolescents from a community sample, with this association only present in adolescents with low putamen activity in response to reward (Dennison et al., 2016). Moreover, dmPFC activity in response to sad faces showed a negative association with depressive symptoms at 1-year follow-up in 16-year-old females from a community sample (Vilgis et al., 2018) and the extent of activation within an amygdala-posterior cingulate-insula circuitry in response to fearful faces was negatively associated with self-reported depressive symptoms, but not MDD onset, at 2-year follow-up (Shapero et al., 2019). These blunted responses in association with onset or increases in depressive symptoms are consistent with an EEG study, in which a blunted late positive event-related potential, thought to reflect reduced emotional engagement, mediated the effect of negative life events on increases in depressive symptoms at 1-year follow-up in 8-14-year-old girls (Levinson et al., 2018). In contrast to these blunted responses, greater thalamus and insula activity in response to positive emotional faces predicted subsequent onset of MDD (Whalley et al., 2015) and heightened amygdala reactivity to neutral faces was related to depressive symptoms at 2-year follow-up (Mattson et al., 2016) in risk-enriched samples. Only one study with a small sample of healthy school-age children with or without a family history of MDD (N = 44, aged 8–12) found no association between brain activity in response to emotion processing and sub-threshold depressive symptoms at 18-months follow-up (Pagliaccio et al., 2014).

3.3.2.2. Association between longitudinal changes in imaging and changes in depressive symptoms

Only one study examined longitudinal changes in brain activity in relation to changes in depressive symptoms and reported an association between increases in amygdala and left ventrolateral PFC activity from baseline (age 13) to two-year follow-up during an emotional n-back task, with happy and fearful faces, and an increase in depressive symptoms (Bertocci et al., 2017).

3.3.3. Task-related: executive functioning

At-risk adolescents (family history of bipolar disorder, aged 16–25), who developed MDD within 2 years of follow-up, showed greater activity in the bilateral insula at baseline while performing an executive functioning task, compared to those who remained free of depression (Whalley et al., 2013), whereas in young adults with a history of MDD (age 18–23) lower activation in the middle frontal gyrus during cognitive control as well as lower connectivity within the cognitive control network were associated with depression recurrence one year later (Langenecker et al., 2018). One study suggested that these brain alterations are modulated by negative life events, as activation in the frontal cortex and insula during cognitive control was only associated with higher depressive symptoms at follow-up in the presence of negative life events (Maciejewski et al., 2018). In contrast, an EEG study did not find any associations between neural response to error processing in the Flankers task and depression onset 1.5 year later in girls (Meyer et al., 2018).

3.3.4. Resting state functional MRI

3.3.4.1. Association between baseline imaging and MDD onset or changes in depressive symptoms

One of the largest studies to date that examined the reward network during rest (in absence of a task) found that increased connectivity of the left ventral striatum with other regions in the reward network predicted depressive disorder, and no other psychopathology such as anxiety, substance use or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, 2 years later in a high-risk sample (N = 637; aged 6–12) (Pan et al., 2017). In addition, amygdala connectivity to the temporal and insula cortices was positively associated with onset of MDD at 3-year follow-up and also mediated the association between maternal aggression at age 12 and MDD onset (Callaghan et al., 2017). However, in a small sample of adolescents who already had an MDD diagnosis at baseline, greater baseline connectivity between amygdala and bilateral insula was associated with lower depressive symptoms at 3 months follow-up, whereas greater baseline connectivity between the amygdala and OFC was associated with an increase in depressive symptoms (Connolly et al., 2017). Further, in healthy adolescents, greater left amygdala with left cerebellar vermis, but lower connectivity between amygdala and IFG, supramarginal gyri and mid-cingulate cortex, was associated with escalation of depressive symptoms during follow-up (ages 12–16 years) (Scheuer et al., 2017). Increased right dorsolateral PFC (dlPFC) to dorsal ACC connectivity was also associated with higher depression scores at one-year follow-up, but not when corrected for baseline depression (Lopez et al., 2018). Furthermore, five variables that predicted most of the variance of total resting state connectivity (including default mode network and dlPFC connections) predicted MDD onset two years later (55% sensitivity, 86% specificity) (Shapero et al., 2019). Four EEG studies found that lower resting medial frontal activity was associated with subsequent depression onset or increases in depressive symptoms during follow-up (Nusslock et al., 2011; Pössel et al., 2008; Mitchell and Pössel, 2012; Stewart and Allen, 2018), while one EEG study did not find any significant associations (Blackhart et al., 2006).

3.3.4.2. Association between longitudinal changes in imaging and changes in depressive symptoms

Increasing resting state right amygdala to rostral ACC connectivity across adolescence was associated with depressive symptoms in adulthood in a large community sample (N = 246; Jalbrzikowski et al., 2017). In addition, decreases in subgenual ACC to dmPFC, posterior cingulate cortex, middle temporal gyrus and angular gyrus connectivity over 2 years was associated with increases of depressive symptoms at 2-year follow-up (Strikwerda-Brown et al., 2015), while developmental increases in amygdala to subgenual ACC connectivity was associated with depression onset within a 2-year follow-up period (Davey et al., 2015).

3.3.5. Summary fMRI and EEG studies

EEG and fMRI studies consistently showed that blunted neural response in the VS during reward anticipation or outcome preceded increases in depressive symptoms and onset of MDD during follow-up. Moreover, higher VS activity to reward was associated with a reduction in symptoms in a small sample. These results were found across multiple studies, including studies with large samples (Hanson et al., 2015; Nelson et al., 2016; Stringaris et al., 2015). Nonetheless, only one study corrected for baseline anxiety symptoms (Hanson et al., 2015). Hypoactivity in the caudate, hyperactivity in the prefrontal cortices (e.g. medial PFC, OFC and ACC) and alterations in connectivity (between the OFC and insula, and between the VS and mPFC) during reward processing have been associated with an increase in MDD symptoms, but only in few isolated studies, thus requiring further replication. Convergence is emerging for a role of blunted neural responses within affective neural circuitries including dorsomedial prefrontal regions, amygdala, insula, posterior cingulate cortex and putamen to emotional facial expressions in future depression onset or increases in depressive symptoms. However, heightened activity in these regions were also reported and most studies focused only on a few specific regions of interests (ROIs) and, as a result, some ROIs were only examined in one or two studies. Other fMRI studies focussed on executive functioning and preliminary evidence in very few studies suggests that greater insula activity may precede the onset of MDD, potentially mediated by negative life events. Resting state fMRI studies show highly inconsistent results and isolated findings, whereas resting state EEG studies consistently showed that lower medial frontal activity was associated with higher depressive symptoms and depression onset during follow-up.

4. Discussion

In this systematic review we examined the association between neuroimaging markers and depression onset and course in childhood and adolescence. While the number of studies on this topic is still limited and sample sizes are often small, there is emerging convergence for a role of some brain regions and functions implicated in depression onset.

Functional imaging studies produced some consistent results, especially in relation to altered reward processing, with EEG and fMRI studies consistently showing blunted activity in the ventral striatum in response to reward anticipation and outcome, as well as functional connectivity alterations in a reward circuitry including the ventral striatum both during reward processes and during rest, to precede depression onset or increases in depressive symptoms. These findings are in line with recent review and meta-analyses examining the evidence for an association between reward processing and depression (Keren et al., 2018; Kujawa and Burkhouse, 2017; Luking et al., 2016). In line with this functional dysfunction, one structural study reported a smaller nucleus accumbens to be associated with subsequent depression onset (Whittle et al., 2014). However, this has not been replicated in other structural studies, as many studies have not focussed on the nucleus accumbens specifically. The ventral striatum is a core hub of the reward network, projecting to cortical regions, the ventral pallidum, thalamus, amygdala and hippocampus and has been associated with anhedonia (Gorwood, 2008). Dysfunction in reward processing has also been implicated in other psychiatric disorders, as anhedonia, which reflects an absence of a drive to engage in rewarding activities, is a central characteristic of multiple psychiatric disorders (Der-Avakian and Markou, 2012; Heinz et al., 1994). Indeed, a transdiagnostic study in adults with schizophrenia, addiction or MDD showed blunted ventral striatum activity during reward anticipation across all psychiatric disorders (Hägele et al., 2015). However, the blunted activation was associated with depressive symptoms independent of diagnosis. In addition, in bipolar depression reduced ventral striatum activity to reward also correlated with depression severity (Satterthwaite et al., 2015). Therefore, blunted ventral striatum response to reward could specifically be associated with changes in depressive symptoms and the literature reviewed here suggests that altered reward processing may precede the onset of depression, and may thus represent a vulnerability factor for developing MDD, rather than a state characteristic of MDD.

Prospective (f)MRI studies mainly consisted of risk enriched samples, whereas the EEG and studies with longitudinal imaging data were more often community samples. Community samples are characterized by a wider range of non-specific risk factors, whereas the risk enriched samples are selected based on one prevalent risk factor. Regarding reward processing, the results of the studies that included risk-enriched samples were in line with community samples in that lower ventral striatum activity to reward was associated with depression onset. Other cognitive domains have been studied less extensively, which will be important to address in future studies as cross-sectional studies have implicated a role for executive processing and self-referential cognition in depression aetiology (Austin et al., 2001; Clark et al., 2009; Kerestes et al., 2014).

The literature is inconsistent regarding the association of depression onset and brain structure. Most studies focussed on hippocampal volumes, however, no convincing evidence across studies was found for a role of abnormal baseline volumes or developmental changes within this region in onset or changes in depressive symptoms. Chronic stress induces elevated glucocorticoid levels due to chronic hyperactivity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and the hippocampus has a particularly high expression of glucocorticoid receptors (Sapolsky et al., 1984). Chronic elevated levels of glucocorticoids may promote atrophy of the hippocampus via remodelling and downregulation of growth factors including brain-derived neurotrophic factor (Campbell and MacQueen, 2004). Therefore, it has been suggested that lower hippocampal volume may be the result of chronic stress associated with depression rather than a pre-existing vulnerability factor, which is in line with some evidence of hippocampal volume reductions observed only in those with multiple episodes of depression and not in first episode depression (Schmaal et al., 2016; McKinnon et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2017). Nonetheless, findings from few studies reviewed here suggest that the hippocampus may play a role in the onset of MDD, but specifically in interaction with genetic and environmental factors such as childhood trauma, specific genotypes, and parental behaviour, which impact on hippocampal volumes through similar stress-related mechanisms (Frodl and O’Keane, 2013). However, these potential modulating effects of genetic and environmental factors on the association between hippocampal volume and onset of MDD need to be replicated in larger samples.

Preliminary evidence suggests that alterations in lateral and medial prefrontal regions (lateral and medial OFC, IFG, rostral ACC, insula) and temporal regions (parahippocampal gyrus, inferior and superior temporal gyri) may precede the onset of depressive symptoms, and reduced thinning or surface area expansion of the OFC and ACC across adolescence was also found to be associated with increases in depressive symptoms. The OFC and ACC play an important role in social and emotional behaviour, emotion regulation and anhedonia (Allman et al., 2001; Bremner et al., 2002; Drevets, 2007) and alterations in these cognitive and behavioural processes are thought to contribute to risk for MDD (Kovacs et al., 2008; Loas, 1996). Of note, most structural studies focussed either on volume or cortical thickness, whereas cortical surface area is understudied in association with depression onset or course. This is important because cortical volume, thickness and surface area show different developmental pathways, which is especially relevant in childhood and adolescence (Amlien et al., 2016; Ducharme et al., 2016; Tamnes et al., 2017; Wierenga et al., 2014; Zhou et al., 2015).

Structural as well as functional (connectivity) alterations in the insula were found to be associated with future depression onset (Belden et al., 2015; Callaghan et al., 2017; Connolly et al., 2017; Foland-Ross et al., 2015; Lichenstein et al., 2017; Whalley et al., 2013), and the insula was reported to be one of the regions contributing most to the prediction of onset of MDD in the study by Foland-Ross et al. (2015) that used a machine-learning algorithm. The insula is involved in multiple processes such as emotion regulation and decision making in reward processing (Craig, 2009; Pavuluri and May, 2015; Simmons et al., 2013; Uddin et al., 2014) through its connection with the anterior cingulate cortex, orbitofrontal cortex and ventral striatum (Augustine, 1996; Chikama et al., 1997; Mesulam and Mufson, 1982). In addition, it is part of an extended salience network, which is involved in bottom-up detection of salient stimuli, interoceptive awareness for positive and negative internal states and switching between emotional brain areas and more central executive regions (Menon and Uddin, 2010; Sridharan et al., 2008). Insula abnormalities may reflect a disproportionate allocation of resources to the internal experience of negative self-focus thinking and emotional experience and a failure to switch to higher order cognitive processes involved in the reappraisal of negative emotions and in allocating toward the external environment, which may in turn contribute to the development of MDD. The value of structural and functional insula alterations as a vulnerability factor for depression onset seems promising and requires further study.

4.1. Future directions

There is still a paucity of unique samples in longitudinal studies investigating the relationship between brain alterations and onset or changes in depressive symptoms in children and adolescents, especially in (f)MRI research. Many of the 68 studies that examined associations of neuroimaging and subsequent depressive symptoms in young people were conducted in overlapping samples, which led to a limited number of 34 unique samples included in this review. The literature reviewed also underscores the need for careful consideration of age, pubertal timing and developmental stage, as preliminary evidence suggests that associations between brain alterations and subsequent onset of MDD are different for different age groups or for individuals within different stages of development. Hormone levels change drastically during puberty, and these hormones affect brain development and associated maturation in cognitive and behavioural processes (Juraska and Willing, 2017; Sisk and Zehr, 2005). For example, associations between smaller hippocampus or less hippocampal growth and onset of depression was found in adolescents aged on average between 11–16 at baseline (Little et al., 2015, 2014; Rao et al., 2010; Whittle et al., 2014, 2011), while this association was absent in pre-adolescents and young adults (Nickson et al., 2016; Pagliaccio et al., 2014; Papmeyer et al., 2016). In addition, earlier pubertal timing mediated the association between larger baseline pituitary gland volumes and greater depressive symptoms at follow-up (Whittle et al., 2012).

The examination of sex differences has received insufficient attention in the longitudinal neuroimaging literature related to depression onset and is a critical area for future study. A few studies found different effects in females compared to males (Morgan et al., 2013; Schmaal et al., 2017b; Vulser et al., 2015; Whittle et al., 2011, 2014), emphasises the need of taking sex into account, while the majority of studies did not consider or were underpowered to examine sex differences. There are well-established sex-dependent differences in the prevalence of and etiological pathways to MDD (Kendler and Gardner, 2014), with higher rate of MDD in females, as well as differences in the timing of brain maturation between males and females, with for example adolescent males reaching peak brain volumes later than females (Lenroot and Giedd, 2010). Future studies of brain alterations associated with onset of or changes in depressive symptoms should be designed to investigate sex effects.

Some studies examined mediating effects of environmental (e.g. early life adversity, parental aggressive behaviour, pubertal timing) and genetic (such as serotonin transporter genes, family history) risk factors for depression. These factors could mediate the relationship between brain alterations and risk for depression, since, for example, childhood trauma is known to be associated with brain alterations and increases the risk for developing depression (Heim et al., 2008; Teicher et al., 2016). However, the observed results regarding these interaction effects were inconsistent, likely due to small sample sizes with insufficient statistical power to detect such complex, but relevant, interactions between genetic and environmental factors, structural and functional brain alterations and risk for developing depression. Large longitudinal studies in the general population (e.g., the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study) or enriched high-risk populations (e.g., the Healthy Brain Network) could substantially increase statistical power to provide more robust and reliable findings and have the ability to study complex interactions with age, developmental stage (age, pubertal timing), sex effects and genetic and environmental modulators (Alexander et al., 2017; Casey et al., 2018).

Furthermore, outcome variables used in the different studies, were heterogeneous, with studies looking at changes in symptoms including subthreshold symptoms, while other studies focussed on onset of clinical depression. Studies focussing on onset of MDD did not always take pre-existing subthreshold depressive symptoms into account. Depression exists on a continuum and subthreshold depression affects functioning and increases the risk of developing depression (Fergusson et al., 2005; Lewinsohn et al., 2000). Moreover, subthreshold depression might also alter brain structure or functioning (Allan et al., 2016; Besteher et al., 2017). Therefore, not considering or correcting for subthreshold depressive symptoms (i.e., depressive symptoms not meeting the criteria for an MDD diagnosis) limits potential interpretations with regard to whether brain alterations are pre-existing risk factors for the development of depression or are the result of stress associated with subthreshold depressive symptoms. Such inferences are further limited by the presence of other pre-existing or comorbid conditions (e.g., childhood trauma, anxiety disorders) often not reported in the studies reviewed, but that may affect brain structure and function, which could in turn increase the risk for depression. Therefore, future studies would benefit from more inclusive samples, thereby increasing generalizability, while also collecting more information on sociodemographic (e.g. socioeconomic status) and developmental (e.g. pubertal status) characteristics, as well as information on clinical history (e.g., prior psychiatric diagnoses, childhood trauma, or other negative life events) and co-morbidities to correct for confounding factors or to be able to examine subgroups (LeWinn et al., 2017).

Future studies in larger samples may also benefit from using a whole brain approach instead of a region-of-interest approach, which will increase the opportunity to examine reproducibility of findings across studies. In addition, since reproducibility would increase clinical utility of the findings in the studies, inclusion of independent replication samples is needed. For example, Jalbrzikowski et al. (2017) repeated and replicated part of their analyses in an independent cohort (the Philadelphia Neurodevelopmental Cohort). Finally, for a biomarker to become clinically relevant, it should be able to predict onset of depression at an individual level. Only one study included in this review examined the predictive value of neuroimaging markers on subsequent onset of depression at an individual level. That is, Foland-Ross et al. (2015) applied a machine learning method to evaluate whether a predictive model based on cortical thickness measures can reliably predict onset of depression in new (unseen) individuals, showing an accuracy of 70%. By quantifying the prediction success in new individuals, machine learning approaches are better suited to identify neuroimaging markers that are clinically relevant.

5. Conclusion

Adolescence and young adulthood are the lifetime peak periods for onset of MDD (Kessler et al., 2007, 2005; Weissman et al., 1996) and onset of depression during this period of life disrupts critical aspects of development and functioning, including social, academic, employment and health outcomes (Hetrick et al., 2008), and are related to an elevated risk of mental illness later in life (Patton et al., 2014). Studies investigating the association between neuroimaging and subsequent onset or increases in depressive symptoms can provide critical information about vulnerability factors for the onset of depression, which may in turn provide targets for early intervention or prevention strategies. In this literature review, we found consistent evidence for reduced neural response to reward in the ventral striatum and prefrontal cortex to be associated with onset of or increases in depressive symptoms later in adolescence. Associations with other functional brain alterations have been less explored and structural findings were highly inconsistent with preliminary evidence suggesting that they may be dependent on environmental and genetic factors, and perhaps critical sensitive periods. Future studies should include larger, more representative samples, while also consider potentially confounding factors. In addition, analytic methods such as machine learning techniques should be utilized to allow imaging risk markers to be identified at the level of the individual instead of at a group level, which is crucial for clinically viable biomarkers.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the MQ Brighter Futures Award MQBFC/2 and the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health [R01MH117601]. LS is supported by a NHMRC Career Development Fellowship [1140764]. BJH is supported by a NHMRC Career Development Fellowship [1124472]. CGD is supported by a NHMRC Career Development Fellowship [1141738].

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcn.2019.100700.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Albaugh M.D., Nguyen T.V., Ducharme S., Collins D.L., Botteron K.N., D’Alberto N., Evans A.C., Karama S., Hudziak J.J., The Brain Development Cooperative Group Age-related volumetric change of limbic structures and subclinical anxious/depressed symptomatology in typically developing children and adolescents. Biol. Psychol. 2017;124:133–140. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2017.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander L., Escalera J., Ai L., Andreotti C., Febre K., Mangone A., Vega-Potler N., Langer N., Alexander A., Kovacs M., Litke S., O’Hagan B., Andersen J., Bronstein B., Bui A., Bushey M., Butler H., Castagna V., Camacho N., Chan E., Citera D., Clucas J., Cohen S., Dufek S., Eaves M., Fradera B., Gardner J., Grant-Villegas N., Green G., Gregory C., Hart E., Harris S., Horton M., Kah D., Kabotyanski K., Karmel B., Kelly S., Koo B., Kramer E., Lennon E., Lord C., Mantello G., Margolis A., Merikangas K., Milham J., Minniti G., Neuhaus R., Levine A., Osman Y., Parra L., Pugh K., Racanello A., Restrepo A., Saltzman T., Septimus B., Tobe R., Waltz R., Williams A., Yeo A., Castellanos F.X., Klein A., Paus T., Leventhal B., Craddock R., Koplewicz H., Milham M. An open resource for transdiagnostic research in pediatric mental health and learning disorders. Sci. Data. 2017;4:170181. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2017.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]