Abstract

Amid the rise in conflict and war and their ensuing repercussions, traumatic injuries, psychological distress, and communicable diseases spread widely. Today, health-care providers in the Middle East are faced with new and unfamiliar cases resulting from the use of new and advanced types of weapons. In addition, there has not been enough emphasis on hands-on experiences in medical school, which can be imperative in times of war. Lack of academia is another inadequacy that limits the transmission of knowledge onto the newer generations. Here, we will shed light on the inadequacies in medical curricula in the Middle East when it comes to addressing patients of war. We also call for action to advance medical education in war-ridden areas by incorporating “conflict medicine” as an integral module in medical curricula.

Keywords: Conflict medicine, Medical education, Middle East, War

INTRODUCTION

War is a major contributor to traumatic injuries and psychological distress. The Middle East, being one of the most conflict-ridden regions in the world today, continues to be an unfortunate site for traumatic events. Across the region, outbreaks of infection have occurred as a direct result of recent wars, compounded by food and water shortages, displacement, and damage to infrastructure and health services.[3,7] In addition, psychological effects, such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and anxiety disorders,[5] are on the rise and will become more apparent in the years to come.

Several initiatives highlighted the importance of improving health care in times of conflict. Nevertheless, not much has been done to integrate “conflict” as part of the core of medical education. Here, we call for action to advance medical education in war-ridden areas by incorporating “conflict medicine” in medical curricula.

CONFLICT-RELATED INJURIES: A RISING CHALLENGE

Conflict-related injuries can be varied and complex; resulting pathologies can be classified into war related and nonwar related. War-related illnesses include victims of blasts and burns, who present acutely, or those with chronic conditions like PTSD. This category also includes those affected by communicable diseases as a result of conflict and migration. Nonwar-related diseases include patients with noncommunicable diseases who have lost access to adequate health care and those who suffer the deterioration of health systems and facilities.[3,13] The use of new weapons raises new challenges as well.[4,8-10,12,14] Health-care providers are faced with new and unfamiliar cases resulting from these types of weapons.[12] Often, specialized trauma surgeons and/or seasoned general surgeons are the ones who explore these cases. Unfortunately, the number of these experienced surgeons is small. As such, the need to train newer generations of conflict-adept physicians arises.

CONFLICT MEDICINE: DEFINITION AND CURRENT STATUS

Conflict medicine is an area that specializes in delivering health care to conflict and war survivors and providing medical preparation, planning, response, and recovery throughout the conflict’s life cycle. Its specialists provide insight, guidance, and expertise on the principles and practice of medicine in the acute settings of the conflict zone. Unlike all other areas of specialization, the conflict medicine specialist only practices the full scope of the specialty in conflict-related emergencies.[6]

The current medical education systems in the Middle East guarantee that medical graduates, at best, are competent in reaching a diagnosis and planning a treatment. Nevertheless, there has not been enough emphasis on hands-on experiences, which can be imperative in times of war. Basic invasive skills such as suturing and placing intravenous lines are not mastered by the end of medical school. In addition, the over-reliance on advanced diagnostic tools decreases the physician’s effectiveness in acute situations and unequipped zones. Furthermore, the rigidity in following set guidelines and the inability to adjust guidelines as per presenting cases present a limitation.

Comprehensive care of patients in conflict requires coordination of medical, social, and public health sectors. Therefore, the development and integration of modules on conflict/disaster medicine in medical education must become a priority for medical schools and health-care centers in the region to better equip the medical personnel in the Middle East with skills and knowledge that can benefit their communities in times of need.

Lack of academia is another inadequacy that limits the transmission of knowledge onto the newer generations. Often, physicians who are mostly exposed to conflict-related injuries work in primary care centers and hospitals that are close to zones of conflict and thus are not academic, meaning they do not work in academic medical centers.[11,13] Therefore, their knowledge is not transmitted to the next generation of physicians. In addition, academic physicians that have conducted research on conflict-related medicine are not instructed or expected to share their experiences.

EMBRACING CONFLICT MEDICINE

With the rising conflict-related challenges in the Middle East, embracing conflict medicine seems imminent to ensure the appropriate delivery of health care in acute settings and war zones. Medical schools in the Middle East by adopting or copying curricula present in developed countries lack the ingredients needed to address the new health challenges in such conflict-ridden societies. Although universal medicine ensures the learning of the basic principles of medicine, it does not target the needs of society. In addition, the lack of proper planning and governmental strategies to implement curricular changes and to address health needs exacerbates the problem.[11,13,15] Still, medical schools are the ones that should be leading the efforts to change the current status quo in coordination with policy-makers. Establishing a unified clear vision for medical education in the region is necessary for an appropriate response to societal needs. As such, integrating conflict medicine into medical education programs is essential. Furthermore, supporting research efforts to study conflict-related injuries and socioeconomic conditions will help in improving future delivery of care. Health professionals and trauma specialists, who are familiar with war injuries, should be supported to build the capacity of local health workers in directly affected countries such as Syria, Yemen, Iraq, and Palestine.

THE CONFLICT MEDICINE MODULE

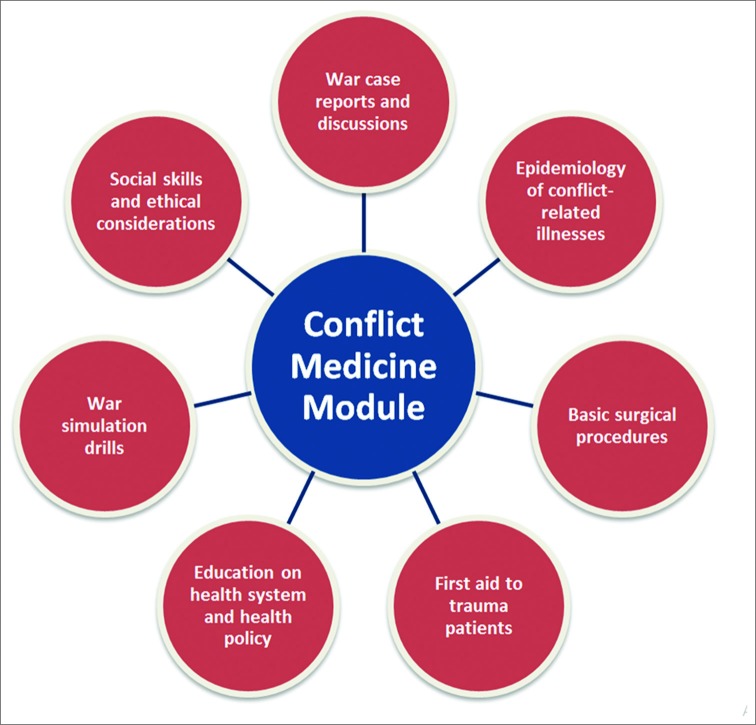

We propose that conflict medicine be included in the medical curricula of war-ridden countries as a module, which will emphasize the conceptualization of hands- on experiences [Figure 1]. Students would be properly educated on the organizational structure of their country’s health system and how it operates in case of conflict. They must also be encouraged to pitch in their ideas on how to address current inadequacies. In addition, getting acquainted with the epidemiology of conflict-related illnesses is vital to comprehend the significance of the module and the issue at hand. Epidemiological studies and efforts to count and stratify casualties should be led and supported by governmental agencies and policy-makers. Moreover, presenting and discussing reports of war cases of different etiologies are necessary to familiarize the students with war- related pathologies and transmit knowledge on how to deal and treat these cases from one generation of physicians to another. Learning basic surgical procedures such as suturing, inserting intravenous lines, and administering first aid to patients with trauma, burns, or injuries due to biochemical weaponry are of high importance. Drills that simulate war times in health-care settings and conflicted zones should be run frequently to keep the students attentive and their skills sharp. Furthermore, social and ethical skills that are needed to provide psychological support to susceptible populations must be introduced and emphasized.[1] Cases of PTSD victims, for example, should be presented and studied, and appropriate therapeutic interventions should be discussed. Moreover, evaluating the knowledge and adaptability of the students in the long run, prospectively, is necessary to ensure that learning objectives are being met.

Figure 1:

Components of the conflict medicine module.

IMPLEMENTATION AND EXPERIENCES OF MEDICAL SCHOOLS

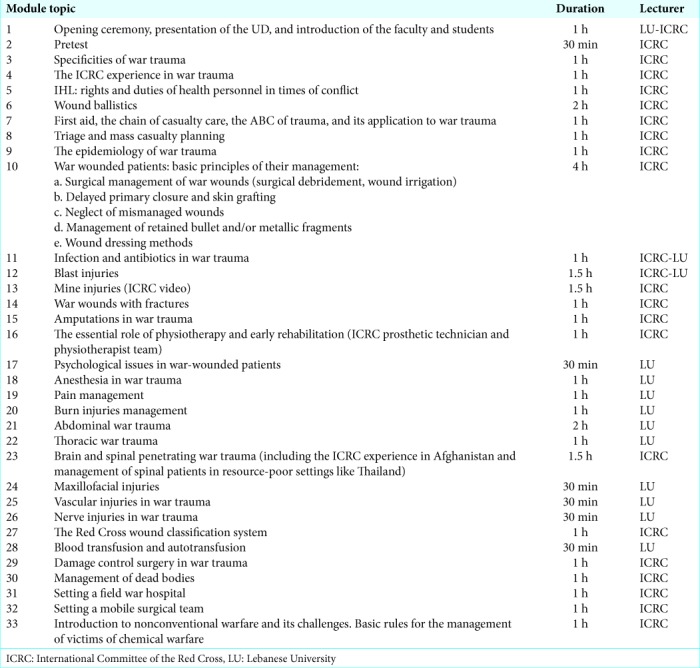

Implementing changes in medical curricula is not easy. This explains why few medical schools have adopted some form of disaster/conflict medicine training as part of their medical curriculum. In Lebanon, the Lebanese University (LU) Faculty of Medicine signed an agreement with the International Committee of the Red Cross to give a module on the clinical management of the war wounded [Table 1]. The intensive and voluntary module takes course over weekends and holidays and includes hands-on training as well as testimonials and lectures from experts in the field. Such an arrangement allowed the medical school rotations to continue to flow regularly without any disruptions to the instated medical program. Furthermore, as most of the patients with war injuries present to community hospitals and nonacademic medical centers close to areas of combat, the LU Faculty of Medicine signed affiliation agreements with a number of rural and community hospitals that are receiving first-hand the bulk of war injuries so that medical students can do parts of their rotations there and thus are exposed and familiarized to conflict-related medical cases. Such an arrangement would not alter the schedule of medical clerkship rotations as patients of war are usually admitted into the regular wards of hospitals with health-care professionals and physicians from different departments providing care as adequate. Therefore, rotating medical students would be encountering these patients normally in the hospitals. In Saudi Arabia, the need for implementation of similar programs has also been highlighted.[2] A course that consists of 2 weeks of classroom activities followed by 8 weeks of e-learning has been proposed to cover the different domains of disaster medicine. Simulations, experiential activities, case studies, and role-playing activities are all used to promote higher levels of cognitive engagement.

Table 1:

Topics covered by the University Diploma (UD) offered jointly by the LU and the ICRC on the clinical management of war-wounded patients.

CONCLUSION

Embracing conflict medicine seems imminent to ensure the appropriate delivery of health care in acute settings and war zones. We believe that investment in health care is crucial to provide cost-effective services to affected populations. Research is often forgotten in the rush to provide emergency care; nevertheless, publications from conflict settings provide better analyses of care provided to improve future care. Finally, intensifying diplomatic efforts to promote dialogue and avoid conflict and war remains the best method to prevent individual harm and societal damage.

Footnotes

How to cite this article: Fares J, Fares MY, Fares Y. Medical schools in times of war: Integrating conflict medicine in medical education. Surg Neurol Int 2020;11:5.

Contributor Information

Jawad Fares, Email: jawad.fares@northwestern.edu.

Mohamad Y. Fares, Email: myf04@mail.aub.edu.

Youssef Fares, Email: yfares@ul.edu.lb.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ayoub F, Fares Y, Fares J. The psychological attitude of patients toward health practitioners in Lebanon. N Am J Med Sci. 2015;7:452–8. doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.168663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bajow N, Djalali A, Ingrassia PL, Ageely H, Bani I, Della Corte F. Proposal for a community-based disaster management curriculum for medical school undergraduates in Saudi Arabia. Am J Disaster Med. 2015;10:145–52. doi: 10.5055/ajdm.2015.0197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bizri AR, Fares J, Musharrafieh U. Infectious diseases in the era of refugees: Hepatitis A outbreak in Lebanon. Avicenna J Med. 2018;8:147–52. doi: 10.4103/ajm.AJM_130_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fares J, Fares Y. Cluster munitions: Military use and civilian health hazards. Bull World Health Organ. 2018;96:584–5. doi: 10.2471/BLT.17.202481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fares J, Gebeily S, Saad M, Harati H, Nabha S, Said N, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder in adult victims of cluster munitions in Lebanon: A 10-year longitudinal study. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e017214. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fares J, Khachfe H, Fares M, Salhab H, Fares Y. Conflict medicine in the Arab world. In: Laher I, editor. Handbook of Healthcare in the Arab World. Cham: Springer; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fares J, Salhab H, Fares M, Khachfe H, Fares Y. Academic medicine and the development of future leaders in healthcare. In: Laher I, editor. Handbook of Healthcare in the Arab World. Cham: Springer; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fares Y, Ayoub F, Fares J, Khazim R, Khazim M, Gebeily S. Pain and neurological sequelae of cluster munitions on children and adolescents in South Lebanon. Neurol Sci. 2013;34:1971–6. doi: 10.1007/s10072-013-1427-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fares Y, El-Zaatari M, Fares J, Bedrosian N, Yared N. Trauma-related infections due to cluster munitions. J Infect Public Health. 2013;6:482–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2013.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fares Y, Fares J, Gebeily S. Head and facial injuries due to cluster munitions. Neurol Sci. 2014;35:905–10. doi: 10.1007/s10072-013-1623-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fares Y, Fares J, Kurdi MM, Bou Haidar MA. Physician leadership and hospital ranking: Expanding the role of neurosurgeons. Surg Neurol Int. 2018;9:199. doi: 10.4103/sni.sni_94_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fares Y, Fares J. Anatomical and neuropsychological effects of cluster munitions. Neurol Sci. 2013;34:2095–100. doi: 10.1007/s10072-013-1343-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fares Y, Fares J. Neurosurgery in Lebanon: History, development, and future challenges. World Neurosurg. 2017;99:524–32. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2016.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoteit A, Fares J. Psycho-environmental tribulations arising from cluster munitions in South Lebanon. Sci Afric J Sci Issues Res Essays. 2014;2:469–73. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mheidly N, Fares J. Health communication research in the Arab world: A bibliometric analysis. Integr Healthc J. 2019 doi: 10.1136/ihj-2019-000011. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]