Abstract

Background

Immune-related genes (IRGs) were linked to the prognosis of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC). This study aimed to identify the effects of an immune-related gene signature (IRGS) that can predict the of HNSCC prognosis.

Methods

The expression data of 770 HNSCC patients from the TCGA database and the GEO database were used. To explore a predictive model, the Cox proportional hazards model was applied. The Kaplan–Meier survival analysis, as well as univariate and multivariate analyses were performed to evaluate the independent predictive value of IRGS. To explore biological functions of IRGS, enrichment analyses and pathway annotation for differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in different immune groups were applied, as well as the immune infiltration.

Results

A prognostic signature comprising 27 IRGs was generated. IRGS significantly stratified HNSCC patients into high and low immune risk groups in regard to overall survival in the training cohort (HR = 3.69, 95% CI 2.73–4.98, P < 0.001). Likewise, IRGS could be linked to the prognosis of HNSCC in patients of the validation cohort (HR = 1.84, 95% CI 1.21–2.81, P < 0.01). Even after adjusting for TNM stage, IRGS was maintained as an independent predictor in the multivariate analysis (HR = 3.62, 95% CI 2.58–5.09, P < 0.001), and in the validation cohort (HR = 1.73, 95% CI 1.12–2.67, P = 0.014). The IFN-α response, the IFN-γ response, IL-2/STAT5 signaling, and IL-6/JAK/STAT3 signaling were all negatively correlated with the immune risk (P < 0.01). Immune infiltration of the high-risk group was significantly lower than that of the low-risk group (P < 0.01). Most notably, the infiltration of CD8 T cells, memory-activated CD4 T cells, and regulatory T cells was strongly upregulated in the low immune risk groups, while memory resting CD4 T cell infiltration was downregulated (P < 0.01).

Conclusion

Our analysis provides a comprehensive prognosis of the immune microenvironments and outcomes for different individuals. Further studies are needed to evaluate the clinical application of this signature.

Keywords: Immune related gene signature (IRGS), Prognosis, Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC)

Background

Head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCCs) represent a group of malignancies in sites of the oral cavity as well as the nasopharynx, oropharynx, hypopharynx, and larynx. Worldwide, more than 600,000 patients are diagnosed with HNSCC every year. Thus, it ranks as the sixth most common form of cancer [1, 2]. Traditionally, the formation of HNSCC is linked to smoking and alcohol consumption. Recently, there is accumulating evidence suggesting that the human papillomavirus (HPV) presents a vital etiological factor in some patients [3]. The 5-year survival rate of HNSCC is approximately 60%, with 380,000 deaths annually [1, 4, 5]. A significant cause of mortality is loco-regional recurrence. For patients suffering recurrent metastatic diseases, the median overall survival (OS) is only 10 to 13 months in the first-line chemotherapy setting and 6 months in the setting of second-line [6]. Moreover, long-term toxicity and morbidity may be induced by the treatment [7]. As a consequence, exploring a novel and reliable signature for prognosis is critical.

Gene expression signatures for survival stratification in HNSCC patients have been proposed by various studies. Elements of the immune system, such as the tumor immune evading mechanism, are increasingly recognized crucial in HNSCC progression [7–9]. The programmed cell death protein 1/programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-1/PDL-1) complex is part of an important immune-checkpoint which is involved in antitumor activity [10]. Importantly, the anti-PD-1 antibodies pembrolizumab and nivolumab were approved for treating platinum-based chemotherapy refractory recurrent or metastatic HNSCC by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2016 [11, 12]. However, the objective response rates to checkpoint blockade immunotherapy only range from 16 to 25% [11, 12]. As recent studies indicated, immune-related biomarkers could define not only the patients’ immune state, but also the biological behavior of HNSCC [13–15]. For example, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in the tumor microenvironment could contribute to improved prognosis [14]. However, the molecular characteristics depicting tumor immune interaction remain largely unknown, specifically in regard to the prognostic potential for HNSCC. Indeed, it is generally believed that an individual’s immune state is too complex to be illustrated by a single immune marker.

Therefore, immune-related genes from a rich supply of HNSCC transcriptional data were analyzed in this study. In order to construct a new signature to facilitate prognosis, combinatorial immune biomarkers were explored and developed. Furthermore, the prognostic prediction significance of this immune-associated gene marker system was systematically validated. This presents a critical step towards developing personalized strategies to improve therapeutic outcomes for HNSCC patients.

Materials and methods

Patients

The gene expression profiles of fresh frozen HNSCC tumor tissue samples from 2 public cohorts involving 770 HNSCC patients were retrospectively analyzed. The largest individual data set training, namely, the Cancer Genome Atlas HNSCC (TCGA HNSCC data set, n = 500), was selected for training. The remaining microarray data set (GSE65858, n = 270) was chosen to serve as a validation cohort. GSE65858 was obtained in its processed form from Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) using Bioconductor package ‘GEOquery’. The level 3 RNA expression profile data of the TCGA HNSCC cohort was downloaded from Broad GDAC Firehose (http://gdac.broadinstitute.org/) and log2-transformed transcripts per million (TPM) were utilized. In all data sets, survival analyses were only performed for patients for whom survival information was accessible. Paper charts as well as electronic medical records was examined when necessary. Information on HPV status for the TCGA cohort were updated according to detection of viral transcripts in RNA sequencing data [16]. ‘Combat’ in R package ‘sva’ was used to remove batch effects. Data were collected from December 20, 2018 to March 20, 2019.

Construction and validation of an individualized prognostic signature based on IRGs

A predictive immune-related signature was constructed by concentrating on immune-related genes (IRGs) obtained from the Immunology Database and Analysis Portal (ImmPort) (https://immport.niaid.nih.gov). The IRGs measured by all platforms included in this study were selected. Prognostic IRGs were further screened by performing 1000 randomizations (each with 80% of all patients) and analyzed by the Cox proportional hazards model to estimate the correlation between each IRG and patients’ OS in the training data set. Since molecular signatures may be shared across stages, HNSCC in all stages were included.

The potential prognostic IRGs with P-values < 0.05 were used as candidates for the construction of the IRGS. To minimize the over-fitting risk and build a risk model for patients in all stages, we combined the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) with the Cox proportional hazards regression model to analyze all stage HNSCC samples. A tenfold cross-validation was used to estimate the penalty parameter in the training data set at the minimum partial likelihood deviance.

Validation of IRGS

To divide patients into low-risk and high-risk groups, the optimal IRGS cutoff was analyzed via a time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve at the 5-year timepoint in the training data set. The ROC curve was estimated through the Kaplan–Meier method. The cutoff value was defined as the IRGS corresponding to the minimum distance between the ROC curve and point standing for the 100% true positive rate and 0% false-positive rate.

The predictive value of the IRGS was evaluated by univariate analyses for HNSCC patients in all stages in the training and validation cohort. Subsequently, IRGS was combined with clinical and pathologic features in multivariate analyses.

Functional annotation and analysis

To explore biological functions of the IRGS, enrichment analyses and pathway annotations for differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in different immune groups were applied using the R package ‘gProfileR’ for the TCGA HNSCC data-set. High- risk and low-risk immune groups were predicted by the Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) by IRGS using the Bioconductor package ‘HTSanalyzeR’ [17]. We examined gene sets of cancer hallmarks from MSigDB [18]. According to the IRGS system, patients were divided into different groups based on the associated immune risk. In the TCCA HNSCC data set, RNA sequencing data as well as data on the infiltration percentages of specific immune cells, such as lymphocytes, monocytes and neutrophils, are available for HNSCC tumor samples. Estimation of Stromal and Immune cells in Malignant Tumor tissues using Expression data (ESTIMATE) [19] was applied to estimate the proportions of immune and stromal cells. CIBERSORT, an established algorithm, was used to perform immune cell type-specific analyses. One-tailed t tests were applied to compare these pathologic features of HNSCC patients within different immune risk groups.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 3.5.1; http://www.Rproject.org). We computed descriptive statistics for all variables. These comprised means and standard deviations (SD), or medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) for continuous factors, as well as frequencies for categorical factors. LASSO regression was enforced using the ‘glmnet’ R package (version 2.0-16). Log-rank tests were used to evaluate univariate analysis of the link between IRGS and clinical pathologic features with OS. The R package ‘survivalROC’ (version 1.0.3) was applied to perform a time-dependent ROC curve analysis. The multivariate analysis was implemented with the Cox proportional hazards regression model for characteristics that were significantly associated with OS in univariate analyses. A P-value of < 0.05 was identified as statistically significant.

Results

Construction and definition of the IRGS

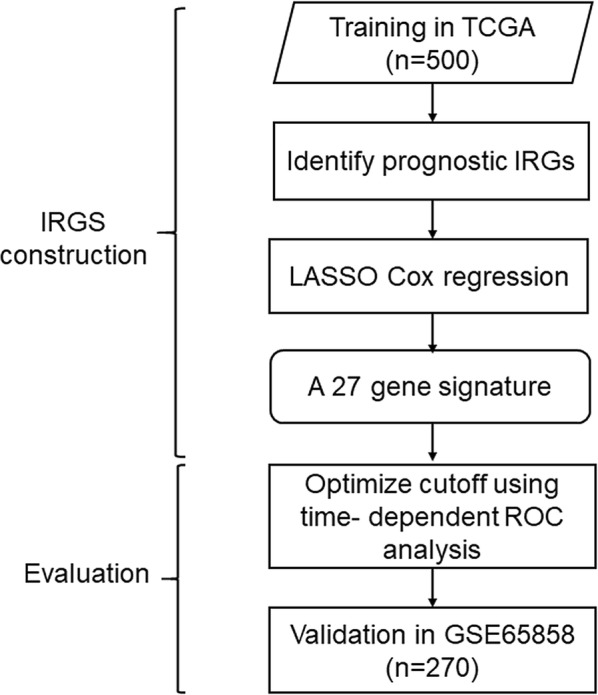

Based on the GEO dataset (GSE65858), a total of 270 eligible HNSCC patients in all stages were included in this study as part of the training cohort. Among 1073 immune genes measured on all platforms, 915 IRGs were selected after filtering median absolute deviation (MAD) > 0.5. By 1000 times resampling, 81 IRGs were robustly associated with individual patients’ OS. Employing LASSO Cox regression, 27 prognostic IRGs were chosen and combined to construct the IRGS (Fig. 1, Additional file 1: Figure S1). Subsequently, the prognosis correlation coefficient of each gene in IRGS was obtained (Table 1). With an optimal cutoff value of 0.106 to stratify low immune risk and high immune risk groups, prognostic significance was satisfactory at the 5-year timepoint, as suggested by the time-dependent ROC curve analysis (Additional file 2: Figure S2).

Fig. 1.

Establish and verification of IRGS. A schematic flow chart of study design and analysis steps

Table 1.

27-Gene immune signature

| Gene | Name | Frequency in resampling | Average P-value | Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RFXAP | Regulatory factor X-associated protein | 957 | 0.013 | 0.073 |

| ULBP1 | UL16 binding protein 1 | 927 | 0.016 | 0.007 |

| TMSB4Y | Thymosin beta 4 | 1000 | 0.002 | − 0.117 |

| RBP4 | Retinol binding protein 4 | 923 | 0.018 | 0.067 |

| LCNL1 | Lipocalin-like 1 | 1000 | 0.002 | − 0.056 |

| CCR6 | Chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 6 | 976 | 0.008 | − 0.009 |

| KLRK1 | Killer cell lectin-like receptor subfamily K | 1000 | 0.000 | − 0.093 |

| PTX3 | Pentraxin-related gene | 999 | 0.002 | 0.037 |

| MASP1 | Mannan-binding lectin serine peptidase 1 | 1000 | 7.447 | − 0.203 |

| HRG | Histidine-rich glycoprotein | 938 | 0.016 | 0.043 |

| CCL22 | Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 22 | 992 | 0.005 | − 0.061 |

| OLR1 | Oxidized low density lipoprotein (lectin-like) receptor 1 | 996 | 0.005 | 0.040 |

| ROBO1 | Roundabout | 923 | 0.017 | − 0.026 |

| BTC | Betacellulin | 902 | 0.020 | 0.146 |

| CHGB | Chromogranin B | 1000 | 0.001 | 0.113 |

| DKK1 | Dickkopf homolog 1 | 1000 | 9.203 | 0.088 |

| HBEGF | Heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor | 905 | 0.022 | 0.109 |

| INHBB | Inhibin beta B | 946 | 0.015 | 0.009 |

| PDGFA | Platelet-derived growth factor alpha polypeptide | 1000 | 0.001 | 0.037 |

| AVPR2 | Arginine vasopressin receptor 2 | 999 | 0.002 | − 0.043 |

| IL20RA | interleukin 20 receptor | 952 | 0.012 | − 0.067 |

| RORB | RAR-related orphan receptor B | 947 | 0.015 | − 0.010 |

| TNFRSF18 | Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 18 | 934 | 0.017 | − 0.071 |

| TNFRSF25 | Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 25 | 987 | 0.006 | − 0.051 |

| TNFRSF4 | Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 4 | 1000 | 0.002 | − 0.054 |

| SH3BP2 | SH3-domain binding protein 2 | 999 | 0.002 | − 0.004 |

| ICOS | Inducible T-cell co-stimulator | 984 | 0.008 | − 0.017 |

Validation of the IRGS as a prognostic factor for HNSCC patients

Two HNSCC transcriptional datasets including prognostic data were selected to evaluate prognosis. The TCGA dataset (n = 500, Additional file 3: Table S1) was selected as the training dataset, the GEO dataset was used as the validation cohort (n = 270, Additional file 3: Table S1). There was no significant difference between the two cohorts in regard to their clinicopathologic characteristics (Table 2, Additional file 4: Table S2).

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of IRGS, clinical and pathologic factors of patients in training cohort

| Characteristic | Univariate | Multivariate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | |

| IRGS | 3.69 (2.73–4.98) | < 0.001 | 3.62 (2.58–5.09) | < 0.001 |

| Age | 1.02 (1.00–1.03) | 0.01 | 1.02 (1.00–1.03) | < 0.01 |

| Gender | 0.71 (0.53-0.96) | 0.03 | 0.90 (0.65–1.26) | 0.55 |

| TNM stage | 1.38 (1.14–1.65) | < 0.001 | 1.24 (1.02–1.50) | 0.03 |

| Pathological grading | 1.14 (0.93–1.39) | > 0.05 | NA | NA |

| Smoking | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Alcohol abuse | 1.01 (0.74–1.37) | > 0.05 | NA | NA |

| HPV | 1.20 (0.88–1.63) | > 0.05 | NA | NA |

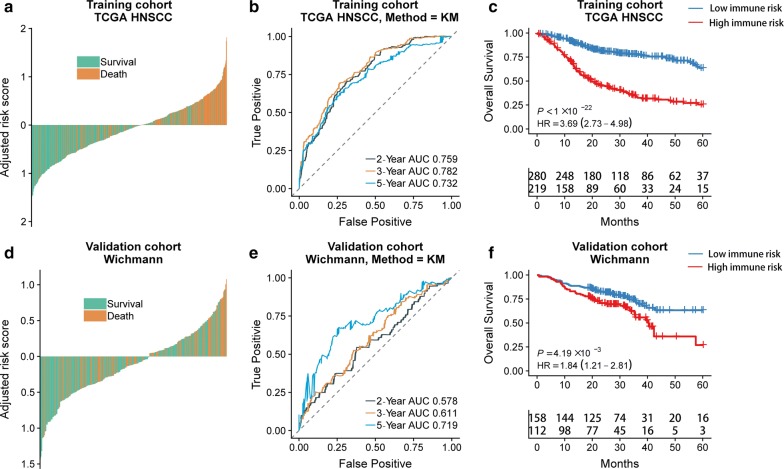

Among the HNSCC patients of training and validation cohorts, individuals of the immune high-risk group showed significantly higher adjusted risk scores for death than those in the immune low-risk group stratified by IRGS (Fig. 2a, d). In regards to 2-year, 3-year and 5-year follow-ups, a high prognostic value was also observed base on the time-dependent ROC curve method applied for the training cohort (AUC = 0.759 at 2 years; AUC = 0.782 at 3 years; AUC = 0.732 at 5 years) and validation cohort (AUC = 0.578 at 2 years; AUC = 0.611 at 3 years; AUC = 0.719 at 5 years) (Fig. 2b, e). IRGS significantly stratified HNSCC patients into low immune risk and high immune risk groups with respect to OS in the training cohort (HR = 3.69, 95% CI 2.73–4.98, P < 0.001), and in the validation cohort (HR = 1.84, 95% CI 1.21–2.81, P < 0.01) (Fig. 2c, f).

Fig. 2.

The outcomes of low and high immune risks in HNSCC patients. The overall survival rate of patients in the different immune risk groups of training cohort (a) and validation cohort (d). Kaplan–Meier curves comparing patients with low or high immune risk in training cohort (b) and validation cohort (e). IRGS significantly stratified HNSCC patients into low immune risk and high immune risk groups in regard to the overall survival in the training cohort (HR = 3.69, 95% CI 2.73–4.98, P < 0.001) (c), the validation cohort (HR = 1.84, 95% CI 1.21–2.81, P < 0.01) (f). P-values were calculated using log-rank tests and HR is short for hazard ratio

IRGS as an independent risk factor for HNSCC patients

As we expected, IRGS, age and tumor stage were associated with the outcomes for HNSCC patients. In the univariate analysis, IRGS were related to OS in the training cohort (HR = 3.69, 95% CI 2.73–4.98, P < 0.001, Table 2). Similarly, it was found that IRGS was linked to OS in the validation cohort (HR = 1.84, 95% CI 1.21–2.81, P < 0.01, Additional file 4: Table S2). Despite adjustment for the TNM stage in the multivariate analysis, IRGS was maintained as an independent predictor in the training cohort (HR = 3.62, 95% CI 2.58–5.09, P < 0.001, Table 2) and in the validation cohort (HR = 1.73, 95% CI 1.12–2.67, P = 0.014, Additional file 4: Table S2).

HPV as a risk factor for HNSCC patients

In the univariate analysis, HPV was not significantly associated with the prognosis for the training cohort (HR = 1.20, 95% CI 0.88–1.63, P > 0.05, Table 2). It was, however, associated with better survival outcome in the validation cohort (HR = 1.95, 95% CI 1.15–3.33, P < 0.05, Additional file 4: Table S2). In the same cohort, when incorporated with other clinicopathologic features, it showed to be significantly linked to the prognosis in multivariate analysis (HR = 2.15, 95% CI 1.24–3.72, P < 0.01, Additional file 4: Table S2).

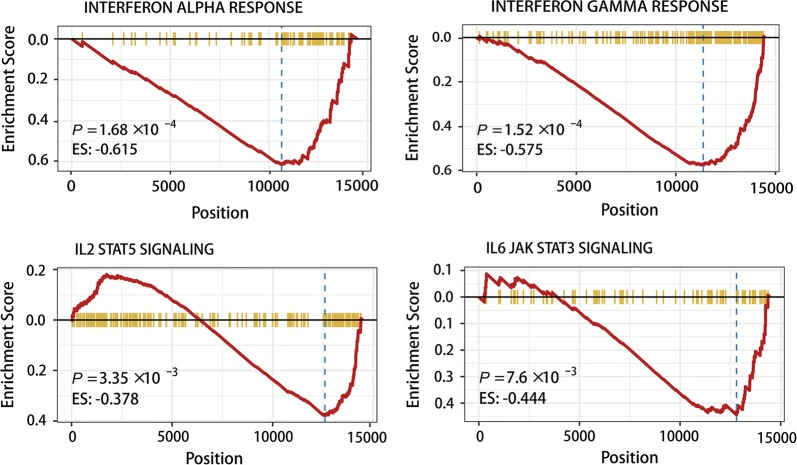

Functional annotation of the IRGS

27 IRGs were included in the IRGS, including UL16-binding protein 1 (ULBP1), chemokine receptors 6 (CCR6), C-C motif chemokine ligand 22 (CCL22), roundabout guidance receptor 1 (ROBO1), dickkopf WNT signaling pathway inhibitor 1 (DKK1) and platelet derived growth factor subunit A (PDGFA), all of which have previously been shown to be correlated to the pathogenesis and progression of HNSCC (Table 1). Moreover, GSEA has been implicated in multiple biological processes that show either a positive or negative correlation with the immune risk in hallmarks of HNSCC. The most beneficial biological functions, condition and signaling pathways included hypoxia, the interferon alpha (IFN-α) response, the interferon-γ (IFN-γ) response, IL-2/STAT5 signaling, IL-6/JAK/STAT3 signaling, epithelial mesenchymal transition, TGF-β signaling, and hedgehog signaling (Fig. 3, Additional file 5: Table S3). Interestingly, IFN-α, IFN-γ, IL-2 and IL-6 were downregulated in patients with a high immune risk (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Functional annotation of the IRGS. GSEA analysis showed the IFN-α response, the IFN-γ response, IL-2 STATS signaling and IL-6 JAK STAT3 signaling were depressed in high immune risk patients. ES is short for enrichment score

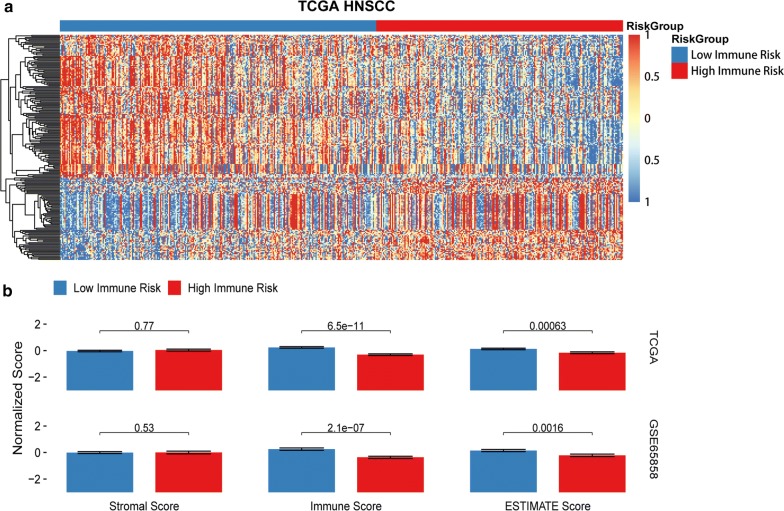

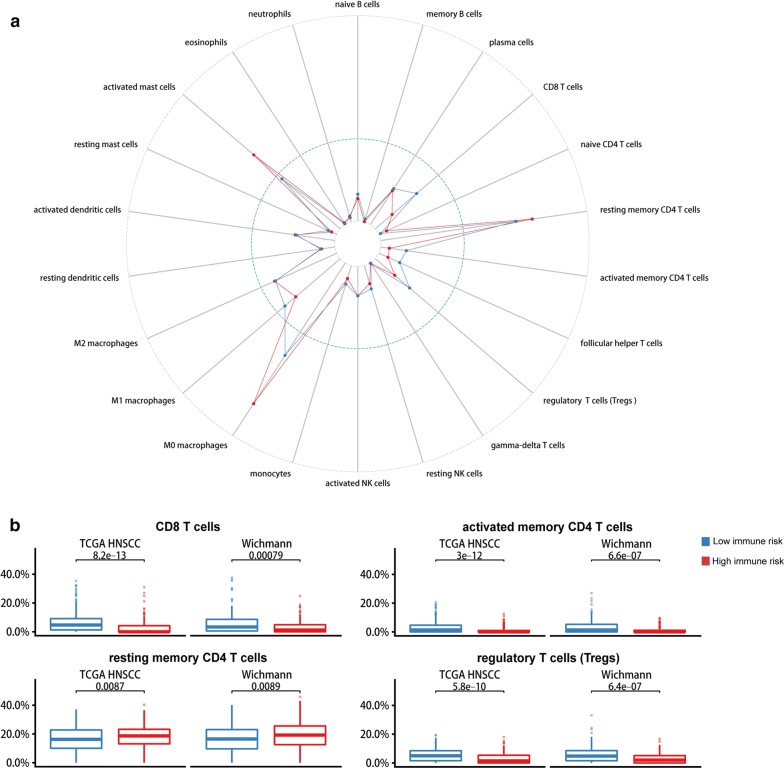

The contributions of stromal cells and immune signaling to HNSCC were estimated by the ESTIMATE algorithm. In accordance with the TCGA HNSCC data set, the IRGS showed that immune infiltration was significantly lower in the high-risk group compared to the low-risk group, with a significant difference seen for the immune score (P < 0.01) and no difference observed for the stromal score (P > 0.05) (Fig. 4b). Most notably, an immune cell type-specific analysis showed that CD8 T cells, CD4 memory activated T cells and regulatory T cells (Tregs) were highly expressed in low immune risk individuals, while CD4 memory resting T cells were enriched in the high immune risk group (P < 0.01, Fig. 5). In other immune-related cells, there was no statistically significant difference between the low- and high-risk groups (P > 0.05).

Fig. 4.

a Functional annotation of the IRGS. Heatmap of differentially expressed genes in two groups. b Analysis of ESTIMATE algorithm to the TCGA dataset

Fig. 5.

a Immune analysis. Immune cells are estimated based on data from TCGA. b The infiltration of CD8 T cells, memory-activated CD4 T cells and regulatory T cells were upregulated in the low immune group, while memory resting CD4 T cells were downregulated. P-values comparing immune high risk and low risk groups were calculated with t-tests

Discussion

Reliable prognostic biomarkers are needed to identify patients with the highest risk of unfavorable survival outcomes. Numerous studies have highlighted the biomarkers associated with the pathogenesis and biology of HNSCC [14, 20–25]. Unfortunately, the accuracy of their survival evaluations remains limited and they have not yet been applied in routine clinical practice. Thus, we developed a prognostic model which incorporates 27 IRGs selected according to the ranking of gene values.

Data of HNSCC patients with different disease states and with a follow-up duration of 5 years were can be stratified into subgroups by our immune-related signature, with a high under-curve area in both the training cohort and the validation cohort. A multivariate analysis showed that incorporation of the developed immune-related signature with clinicopathological characteristics can provide a more appropriate estimation of OS in HNSCC patients. Indeed, previous findings demonstrate the improved survival HPV-positive HNSCC patients compared to patients with HPV-negative HNSCC [26]. It was found that the host immune system was influenced by remarkable downstream consequences following integration of the HPV genome into the host’s genome [26]. Specifically, an increased infiltration of immune cells and inflammatory cytokines has been recognized in the HPV-positive tumor microenvironment. This may aid better cancer clearance after irradiation [7]. Thus, HPV infection could improve the outcome of HNSCC patients. Our study, however, showed that the HPV status may be associated with the OS of HNSCC patients in the validation cohort, but not with the OS in the TCGA cohort. The information on HPV status for the TCGA cohort had been updated according to detection of viral transcripts in RNA sequencing data. One possible explanation for this may be the sample size of the TCGA and GEO datasets was very distinct. These results display that the immune signature of our study may provide a better risk prediction model compared to the HPV status.

Among these 27 genes enrolled in IRGS, six genes (ULBP1, CCR6, CCL22, ROBO1, DKK1 and PDGFA) have previously shown to correlate with the tumorigenesis of HNSCC [20–25]. As reported, CCR6 controls immune cell trafficking in reaction to inflammatory stimuli, hence determining the metastasis of HNSCC cells in vivo [21]. CCL22, an immunosuppressive cytokine, facilitates Tregs infiltration in the HPV-related tongue squamous cell carcinoma [27]. The most significant biological processes that appear to negatively correlate with the immune risk are IFN-α responses, IFN-γ responses, IL-2/STAT5 signaling and IL-6/JAK/STAT3 signaling, all of which were associated with tumor immunity. IL-6, and IFN-α/γ are prominent mediators of intercellular crosstalk [28]. IFN-γ, a key cytokine that is produced by activated T cells, natural killer (NK) cells and NK T cells, coordinates tumor immune responses [29, 30]. In the tumor microenvironment, IFN-γ signaling enhances the activation of the PD-1 signaling axis [31]. Similarly, IL6 blockade upregulates the expression of PD-L1 in melanoma cells [32]. These represent potential immunosuppressive targets to expand the therapeutic window of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 treatment. Modulation of intercellular signaling in the tumor microenvironment could be an efficacious therapeutic modality, and a simultaneous focus on these multiple therapeutic targets may mitigate the risk of a compensatory bypass in a targeted pathway [28].

Our analysis of the IRGS revealed that a higher score of immune cell infiltration was present in the low-risk group. A previous study showed that host immunosuppression is an indispensable factor of carcinogenic progression in HNSCC [32]. The microenvironment of immunodepression is characterized by the infiltration of immune cells such as Tregs [9]. Strong infiltration of forkhead/winged-helix transcription factor box P3 (FoxP3) + Tregs in HNSCC is associated with improved OS [33, 34]. Likewise, our results also demonstrate that Tregs were enriched in low immune risk groups. CD8 T cells that directly target tumor cells are robust, however, CD4 T cells in the tumor microenvironment are ambiguous for a wide range of subsets with potentially different functions [14]. Our results also indicate that CD8 T cells and memory activated CD4 T cells were highly expressed in low immune risk groups, while memory resting CD4 T cells were downregulated. Furthermore, a favorable, prognostic role of CD8 T cell infiltration was associated with better OS in HNSCC patients [14, 15, 35]. Together, our results and the results from these studies suggest that the infiltration of specific immune cells could expedite tumor progression and predict patients’ future survival rates.

As we elucidate the role of the immune system in cancer development, we can provide improved treatment strategies. In this study, we constructed a novel signature that can effectively stratify HNSCC patients into high- and low-risk groups based on clinical outcomes. It, thereby, offers a significantly improved prognostic biomarker potential compared with clinicopathologic risk factors that are currently in use. Our IRGS include stratification methods such as novel markers, specific signaling pathways and immune infiltration. Similarly, an 11-IRGs for predicting the survival of cervical cancer patients and their response to immune checkpoint inhibitors was established [36].

We would like to mention that there are some limitations in this study. First, this is a retrospective study, which is considered inferior to prospective randomized controlled clinical trials. Second, intra-tumor genetic heterogeneity supported by epigenetic and phenomenological data could lead to sampling bias. Third, despite minimization of cross-study batch effects, it needs to be noted that not all batch effects can be eliminated based on their complex nature.

Conclusion

Taken together, our work provides a comprehensive and accurate prognosis of the immune microenvironment and survival outcomes of HNSCC patient. Our results show great promise for the identification of innovative molecular targets for immunotherapy and, hence, the improvement of treatment strategies for HNSCC patients. Further studies are needed to evaluate the clinical application of this signature for the prognosis of HNSCC.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Figure S1. 27 immune related genes selected in LASSO COX regression.

Additional file 2: Figure S2. Obtaining the optimal cutoff at 5 years in a time-dependent ROC curve analysis.

Additional file 3: Table S1. Characteristics of patients in training and validation cohorts.

Additional file 4: Table S2. Univariate and multivariate analyses of IRGs, clinical and pathologic factors of patients in the validation cohort.

Additional file 5: Table S3. GSEA analysis showing the overexpressed biological processes in hallmarks of HNSCC.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Dr. Moe Justine for critical review of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- DEGs

differentially expressed genes

- FoxP3

forkhead/winged-helix transcription factor box P3

- GEO

Gene Expression Omnibus

- GSEA

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis

- HNSCC

head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

- HPV

human papillomaviruses

- HR

hazard ratio

- ImmPort

Immunology Database and Analysis Portal

- IRGs

immune-related genes

- IRGS

immune-related gene signature

- LASSO

least absolute shrinkage and selection operator

- OS

overall survival

- ROC

receiver operating characteristic

- TILs

tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes

- TCGA

The Cancer Genome Atlas

- Tregs

regulatory T cells

Authors’ contributions

YYS, FG and SLF contributed to the study concept and design, the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data, and the drafting of the manuscript. XBK, YPG, PY, ZYL and JYC contributed to the data collections and manuscript reviews. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (No. 2015A030313064), and the Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong Province (No. 2017A010105027).

Availability of data and materials

TCGA cohort data was downloaded from Broad GDAC Firehose (http://gdac.broadinstitute.org/). The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available in the GSE35858 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE35858).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This is a retrospective trial from public datasets with minimal risk and we petition for waiver of ethics consent.

Consent for publication

We have obtained consents to publish this paper from all participants of this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yangyang She, Email: sheyangyang7@163.com.

Xiangbo Kong, Email: 13822183636@163.com.

Yaping Ge, Email: 723790137@qq.com.

Ping Yin, Email: yinping131139@163.com.

Zhiyong Liu, Email: 2646128742@qq.com.

Jieyu Chen, Email: 575817276@qq.com.

Feng Gao, Email: gaof57@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Silian Fang, Email: fangsilian@126.com.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12935-020-1104-7.

References

- 1.Global Burden of Disease Cancer C. Fitzmaurice C, Allen C, Barber RM, Barregard L, Bhutta ZA, et al. Global, regional, and national cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life-years for 32 cancer groups, 1990 to 2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(4):524–548. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.5688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(1):7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jou A, Hess J. Epidemiology and molecular biology of head and neck cancer. Oncol Res Treat. 2017;40(6):328–332. doi: 10.1159/000477127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pulte D, Brenner H. Changes in survival in head and neck cancers in the late 20th and early 21st century: a period analysis. Oncologist. 2010;15(9):994–1001. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Global Burden of Disease Cancer C. Fitzmaurice C, Akinyemiju TF, Al Lami FH, Alam T, Alizadeh-Navaei R, et al. Global, regional, and national cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life-years for 29 cancer groups, 1990 to 2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(11):1553–1568. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.2706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sim F, Leidner R, Bell RB. Immunotherapy for head and neck cancer. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2019;33(2):301–321. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2018.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miyauchi S, Kim SS, Pang J, Gold KA, Gutkind JS, Califano JA, et al. Immune modulation of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and the tumor microenvironment by conventional therapeutics. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(14):4211–4223. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-0871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mirza AH, Thomas G, Ottensmeier CH, King EV. Importance of the immune system in head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2019;41(8):2789–2800. doi: 10.1002/hed.25716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maggioni D, Pignataro L, Garavello W. T-helper and T-regulatory cells modulation in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6(7):e1325066. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1325066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, Gettinger SN, Smith DC, McDermott DF, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(26):2443–2454. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferris RL, Blumenschein G, Jr, Fayette J, Guigay J, Colevas AD, Licitra L, et al. Nivolumab for recurrent squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(19):1856–1867. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seiwert TY, Burtness B, Mehra R, Weiss J, Berger R, Eder JP, et al. Safety and clinical activity of pembrolizumab for treatment of recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (KEYNOTE-012): an open-label, multicentre, phase 1b trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(7):956–965. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30066-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caldeira PC, de Andrade Sousa A, de Aguiar MC. Differential infiltration of neutrophils in T1–T2 versus T3-T4 oral squamous cell carcinomas: a preliminary study. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8:569. doi: 10.1186/s13104-015-1541-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Ruiter EJ, Ooft ML, Devriese LA, Willems SM. The prognostic role of tumor infiltrating T-lymphocytes in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6(11):e1356148. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1356148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shimizu S, Hiratsuka H, Koike K, Tsuchihashi K, Sonoda T, Ogi K, et al. Tumor-infiltrating CD8(+) T-cell density is an independent prognostic marker for oral squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Med. 2019;8(1):80–93. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cao S, Wendl MC, Wyczalkowski MA, Wylie K, Ye K, Jayasinghe R, et al. Divergent viral presentation among human tumors and adjacent normal tissues. Sci Rep. 2016;6:28294. doi: 10.1038/srep28294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang X, Terfve C, Rose JC, Markowetz F. HTSanalyzeR: an R/Bioconductor package for integrated network analysis of high-throughput screens. Bioinformatics. 2011;27(6):879–880. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liberzon A, Birger C, Thorvaldsdottir H, Ghandi M, Mesirov JP, Tamayo P. The molecular signatures database (MSigDB) hallmark gene set collection. Cell Syst. 2015;1(6):417–425. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2015.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoshihara K, Shahmoradgoli M, Martinez E, Vegesna R, Kim H, Torres-Garcia W, et al. Inferring tumour purity and stromal and immune cell admixture from expression data. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2612. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Butler JE, Moore MB, Presnell SR, Chan HW, Chalupny NJ, Lutz CT. Proteasome regulation of ULBP1 transcription. J Immunol. 2009;182(10):6600–6609. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0801214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang J, Xi L, Hunt JL, Gooding W, Whiteside TL, Chen Z, et al. Expression pattern of chemokine receptor 6 (CCR6) and CCR7 in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck identifies a novel metastatic phenotype. Cancer Res. 2004;64(5):1861–1866. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-2968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsujikawa T, Yaguchi T, Ohmura G, Ohta S, Kobayashi A, Kawamura N, et al. Autocrine and paracrine loops between cancer cells and macrophages promote lymph node metastasis via CCR4/CCL22 in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2013;132(12):2755–2766. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maiti GP, Ghosh A, Mondal P, Ghosh S, Chakraborty J, Roy A, et al. Frequent inactivation of SLIT2 and ROBO1 signaling in head and neck lesions: clinical and prognostic implications. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2015;119(2):202–212. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2014.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gao H, Li L, Xiao M, Guo Y, Shen Y, Cheng L, et al. Elevated DKK1 expression is an independent unfavorable prognostic indicator of survival in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:5083–5089. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S177043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ong HS, Gokavarapu S, Tian Z, Li J, Xu Q, Cao W, et al. PDGFRA mRNA is overexpressed in oral cancer patients as compared to normal subjects with a significant trend of overexpression among tobacco users. J Oral Pathol Med. 2017;46(8):591–597. doi: 10.1111/jop.12571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koneva LA, Zhang YX, Virani S, Hall PB, McHugh JB, Chepeha DB, et al. HPV integration in HNSCC correlates with survival outcomes, immune response signatures, and candidate drivers. Mol Cancer Res. 2018;16(1):90–102. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-17-0153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liang D, Xiao-Feng H, Guan-Jun D, Er-Ling H, Sheng C, Ting-Ting W, et al. Activated STING enhances Tregs infiltration in the HPV-related carcinogenesis of tongue squamous cells via the c-jun/CCL22 signal. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1852(11):2494–2503. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2015.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Plzak J, Boucek J, Bandurova V, Kolar M, Hradilova M, Szabo P, et al. The head and neck squamous cell carcinoma microenvironment as a potential target for cancer therapy. Cancers. 2019;11(4):440. doi: 10.3390/cancers11040440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ikeda H, Old LJ, Schreiber RD. The roles of IFN gamma in protection against tumor development and cancer immunoediting. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2002;13(2):95–109. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6101(01)00038-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.El Jamal SM, Taylor EB, Abd Elmageed ZY, Alamodi AA, Selimovic D, Alkhateeb A, et al. Interferon gamma-induced apoptosis of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma is connected to indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase via mitochondrial and ER stress-associated pathways. Cell Div. 2016;11:11. doi: 10.1186/s13008-016-0023-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ritprajak P, Azuma M. Intrinsic and extrinsic control of expression of the immunoregulatory molecule PD-L1 in epithelial cells and squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2015;51(3):221–228. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2014.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsukamoto H, Fujieda K, Miyashita A, Fukushima S, Ikeda T, Kubo Y, et al. Combined blockade of IL6 and PD-1/PD-L1 signaling abrogates mutual regulation of their immunosuppressive effects in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Res. 2018;78(17):5011–5022. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-0118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seminerio I, Descamps G, Dupont S, de Marrez L, Laigle JA, Lechien JR, et al. Infiltration of FoxP3 + regulatory T Cells is a strong and independent prognostic factor in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancers. 2019;11(2):227. doi: 10.3390/cancers11020227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shang B, Liu Y, Jiang SJ, Liu Y. Prognostic value of tumor-infiltrating FoxP3 + regulatory T cells in cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2015;5:15179. doi: 10.1038/srep15179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang F, Zeng Z, Li J, Zheng Y, Wei F, Ren X. PD-1/PD-L1 axis, rather than high-mobility group alarmins or CD8 + tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, is associated with survival in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma patients who received surgical resection. Front Oncol. 2018;8:604. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang S, Wu Y, Deng YJ, Zhou LH, Yang PT, Zheng Y, et al. Identification of a prognostic immune signature for cervical cancer to predict survival and response to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Oncoimmunology. 2019;8(12):e1659094. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2019.1659094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Figure S1. 27 immune related genes selected in LASSO COX regression.

Additional file 2: Figure S2. Obtaining the optimal cutoff at 5 years in a time-dependent ROC curve analysis.

Additional file 3: Table S1. Characteristics of patients in training and validation cohorts.

Additional file 4: Table S2. Univariate and multivariate analyses of IRGs, clinical and pathologic factors of patients in the validation cohort.

Additional file 5: Table S3. GSEA analysis showing the overexpressed biological processes in hallmarks of HNSCC.

Data Availability Statement

TCGA cohort data was downloaded from Broad GDAC Firehose (http://gdac.broadinstitute.org/). The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available in the GSE35858 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE35858).