Significance

Glacier lake outburst floods (GLOFs) have become emblematic of a changing mountain cryosphere. The Himalayas suffered the highest losses from these sudden pulses of meltwater but lack a quantitative appraisal of GLOF hazard. We express the hazard from Himalayan glacier lakes by the peak discharge for a given return period. The 100-y GLOF has a mean discharge of ∼15,600 m3⋅s−1, comparable to monsoonal river discharges hundreds of kilometers downstream. The Eastern Himalayas are a hotspot of GLOF hazard that is 3 times higher than in any other Himalayan region. The size of growing glacier lakes and the frequency of lake outbursts determine GLOF hazard, which needs to be acknowledged better in flood hazard studies.

Keywords: atmospheric warming, meltwater lakes, GLOF, extreme-value statistics, Bayesian modeling

Abstract

Sustained glacier melt in the Himalayas has gradually spawned more than 5,000 glacier lakes that are dammed by potentially unstable moraines. When such dams break, glacier lake outburst floods (GLOFs) can cause catastrophic societal and geomorphic impacts. We present a robust probabilistic estimate of average GLOFs return periods in the Himalayan region, drawing on 5.4 billion simulations. We find that the 100-y outburst flood has an average volume of 33.5+3.7/−3.7 × 106 m3 (posterior mean and 95% highest density interval [HDI]) with a peak discharge of 15,600+2,000/−1,800 m3⋅s−1. Our estimated GLOF hazard is tied to the rate of historic lake outbursts and the number of present lakes, which both are highest in the Eastern Himalayas. There, the estimated 100-y GLOF discharge (∼14,500 m3⋅s−1) is more than 3 times that of the adjacent Nyainqentanglha Mountains, and at least an order of magnitude higher than in the Hindu Kush, Karakoram, and Western Himalayas. The GLOF hazard may increase in these regions that currently have large glaciers, but few lakes, if future projected ice loss generates more unstable moraine-dammed lakes than we recognize today. Flood peaks from GLOFs mostly attenuate within Himalayan headwaters, but can rival monsoon-fed discharges in major rivers hundreds to thousands of kilometers downstream. Projections of future hazard from meteorological floods need to account for the extreme runoffs during lake outbursts, given the increasing trends in population, infrastructure, and hydropower projects in Himalayan headwaters.

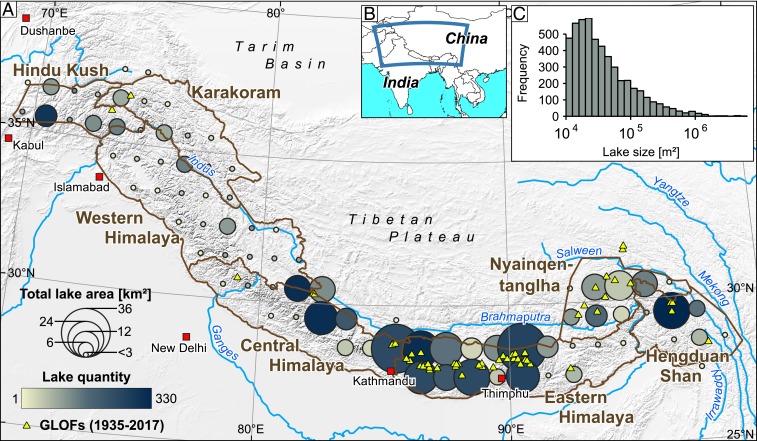

Monsoonal floods are among the most destructive natural hazards in the greater Himalayan region and the adjacent mountain ranges of the Hindu Kush, Karakoram, Nyainqentanglha, and Hengduan Shan (Fig. 1). Regional projections for the lower Indus, Ganges, and Brahmaputra rivers hold that flood frequencies will rise noticeably in the 21st century (1, 2), putting the livelihoods of 220 million people at risk (3). In Himalayan headwaters, such prognoses have disregarded episodic, but potentially destructive, floods from the sudden emptying of moraine-dammed lakes. Such glacier lake outburst floods (GLOFs) occur largely independently of hydrometeorological floods, but can surpass their peak discharges by orders of magnitude in the upper river reaches (4–6). Glacier lakes dammed by abandoned moraines are susceptible to outburst, triggered by ice or debris falls, strong earthquake shaking, internal piping, or overtopping waves that exceed the shear resistance of the dam (7–9). These triggers mostly happen unrecorded in remote terrain, eroding the impounding barriers within minutes to hours, and releasing sediment-laden floods that may travel >100 km downstream (7). With little to no warning, communities and infrastructure downstream have often been caught unprepared, suffering loss of human lives and livestock, and damage to roads, buildings, and hydropower facilities (10–12). An objective and reproducible hazard assessment of such dam-break floods is key to human safety and sustainable development, and is repeatedly emphasized in research and media coverage of atmospheric warming, dwindling glaciers, and growing meltwater lakes (3, 13, 14).

Fig. 1.

Moraine-dammed glacier lakes in the Himalayas. (A) Distribution of moraine-dammed lakes in our study region in 1° × 1° bins. Bubbles are scaled to the total lake area, and color-coded to abundance. Reported GLOFs (yellow triangles) have occurred most frequently in the past 8 decades in regions where glacier lakes are largest (23). (B) Location of the Himalayas between the Indian subcontinent and the Tibetan Plateau. (C) Histogram of glacier lake areas.

GLOFs have gained growing attention in the Himalayas (15, 16), where these disasters have had the highest death toll worldwide (17). While the distribution and dynamics of moraine-dammed lakes have been mapped extensively in recent years (12, 18–21), objectively appraising the current Himalayan GLOF hazard has remained challenging. The high-alpine conditions limit detailed fieldwork, leading researchers to extract proxies of hazard from increasingly detailed digital topographic data and satellite imagery. These data allow for readily measuring or estimating the geometry of ice and moraine dams, the possibility of avalanches or landslides entering a lake, or the water volumes released by outbursts (9, 18, 20). Ranking these diagnostics in GLOF hazard appraisals has mostly relied on expert judgment (18, 22), because triggers and conditioning factors are largely unknown for most historic GLOFs (23).

Guided by studies on earthquakes, landslides, wildfires, and floods, we use the magnitude and frequency of GLOFs in a given area and period as an objective metric of hazard. GLOFs have occurred at an average rate of ∼1.3 y−1 in the Himalayas in the past 3 decades (23), although of differing size, which is conventionally described by the released flood volume V0 or the associated peak discharge Qp. These parameters are difficult to measure during dam failure but can be estimated eventually from the surface areas of glacier lakes. We thus scaled the manually mapped areas of all 5,184 Himalayan moraine-dammed lakes (>0.01 km2) to volumes using a Bayesian robust regression of maximum lake depth versus area from 24 bathymetrically surveyed lakes (Materials and Methods and SI Appendix, Fig. S2 and Table S1). Our approach assumes that all lakes are equally susceptible to outburst and that any incision depth is possible, which is consistent with data from Himalayan dam breaks (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). We used a Bayesian variant of a physical dam-break model (24, 25) to predict peak discharge Qp from the product of V0 and the breach erosion rate k (Materials and Methods and SI Appendix, Figs. S4 and S5). In summary, we obtained 4.6 × 108 and 4.9 × 109 scenarios of V0 and Qp, respectively, for all moraine-dammed lakes in the Himalayas. These numbers ensure that we have sufficiently explored the physically plausible space for fitting an extreme-value distribution to these key flood diagnostics. We further stacked our simulations, accounting for contemporary mean annual GLOF rates between 0.03 and 0.71 y−1 in 7 subregions of the Himalayas, and estimated GLOF return periods in terms of the 100-y flood volume V100 and discharge Qp100 (Materials and Methods) (26, 27).

Results

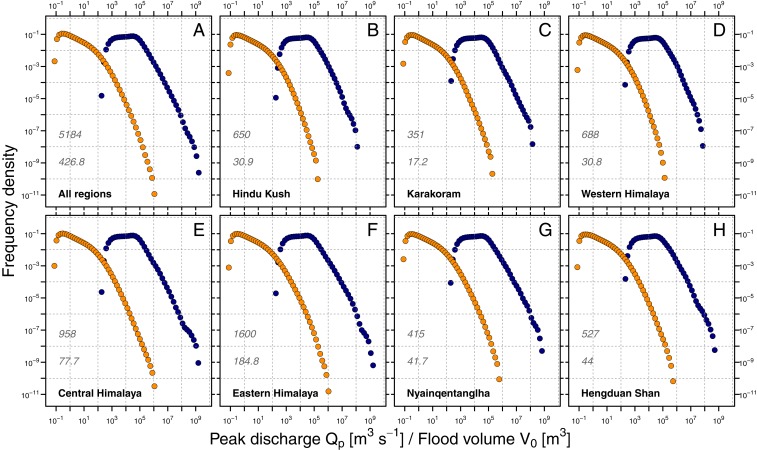

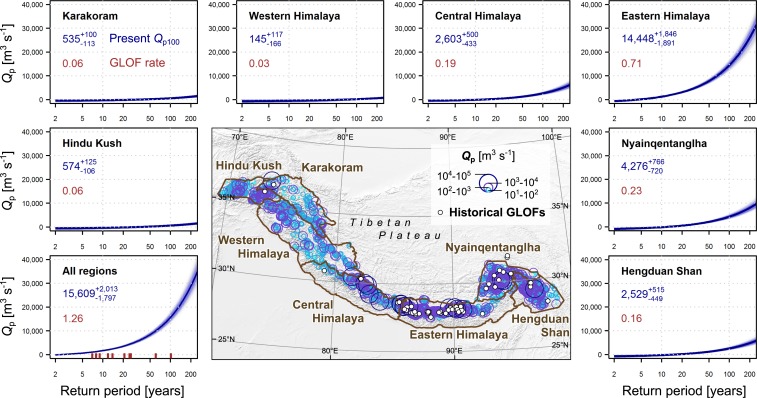

The predicted flood volumes and peak discharges span more than 7 orders of magnitude (Fig. 2). Based on a mean posterior rate of 1.26 GLOFs y−1 over the past 3 decades (23), we estimate a contemporary V100 of 33.5+3.7/−3.7 × 106 m3⋅s−1 and Qp100 of 15,600+2,000/−1,800 m3⋅s−1 in the entire study area (Fig. 3). Regionally differing GLOF rates cause variation in V100 and Qp100. For example, GLOF hazard in the Eastern Himalayas is 350% (V100) and 338% (Qp100) higher than in the next highest region (Fig. 3 and SI Appendix, Fig. S6).

Fig. 2.

Frequency densities of simulated GLOF flood volumes V0 and peak discharge Qp for present Himalayan glacier lakes. Bubbles are log-binned densities of all simulations of flood volumes V0 (blue) and peak discharge Qp (orange) in (A) the entire study area and (B–H) 7 subregions. Gray numbers are the number of lakes (top) and their surface areas (square kilometers) (bottom) for a given region.

Fig. 3.

Estimated 100-y peak discharges from GLOFs in the greater Himalayan region. Circles on the map are present moraine-dammed lakes with colors coded and radii scaled to the modes of the predicted distributions of Qp for each lake. Plots show return periods of GLOF peak discharge for the entire study area (Lower Left) and its 7 subregions. Blue curves are estimated GLOF return periods, and numbers are the posterior mean 100-y flood discharge and 95% HDIs from 1,000 simulations for all 5,184 moraine-dammed lakes, calculated from the mean regional GLOF rate per region in the past 3 decades (brown). Thick dark blue lines are the means from 1,000 simulations (shades) drawing on sampled time series of 10,000 y each (Materials and Methods). Red ticks in Lower Left are average return periods of Qp estimated for a sample of historic GLOFs since 1935 (SI Appendix, Table S2).

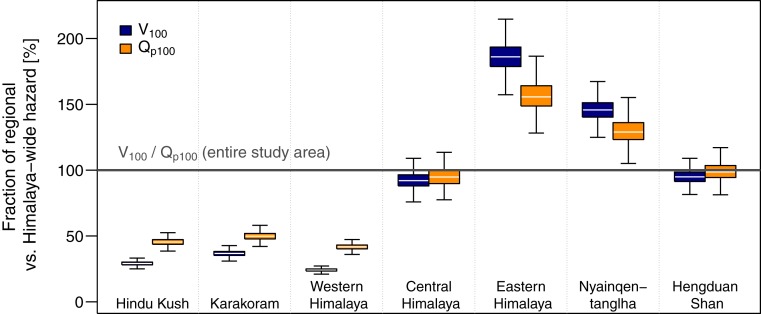

Correcting for regionally varying GLOF rates, we can explore how—for a fixed rate of one GLOF y−1—hazard changes as function of the lake size distribution (Fig. 4). We find that GLOF hazard in the Eastern Himalayas, which currently have the largest lakes and have had the highest GLOF activity in the past 3 decades (23), is on average more than 87% (V100) and 57% (Qp100) higher than the estimate from the entire Himalayas. In contrast, the Western Himalayas had no known outburst from moraine-dammed lakes in the past 30 y, while the rate-adjusted V100 and Qp100 there are still about 76% and 58% below that of the overall study area. In summary, these figures robustly support a contemporary hotspot of GLOF hazard in the southern Himalayas, mainly due to the larger abundance of glacier lakes and GLOFs in that part of the mountain belt.

Fig. 4.

Regional estimates of GLOF hazard as fractions of V100 and Qp100 in the entire study area. We used a fixed mean rate of one GLOF per year in the entire study and all 7 subregions to account for differences in historically recorded GLOF frequencies. Regional estimates are from 1,000 simulations of V100 and Qp100 per region, divided by the corresponding means from the entire study region. Boxes span interquartile range; medians are white horizontal lines; whiskers encompass 1.5 times the interquartile range. This correction method highlights the effects of varying lake size distributions in each region: Glacier lakes in the Hindu Kush, Karakoram, and the Western Himalayas are, on average, too small to generate flood volumes or peak discharges that could compete with those from the entire study region. GLOF hazard in the Eastern Himalayas and Nyainqentanglha is clearly above average, which is due to larger glacier lakes there (Fig. 1 and SI Appendix, Fig. S8).

Discussion

We offer a consistent and reproducible estimate of present GLOF hazard in the Himalayas. Our Bayesian estimates explore the parameter space of plausible flood volumes and associated peak discharges with roughly a million outburst scenarios for any given lake. Our approach expands previous hazard appraisals by explicitly accounting for regionally varying GLOF rates. The estimated GLOF return periods are consistent with the frequency of reported flood volumes and discharges since 1935 (Fig. 3 and SI Appendix, Fig. S6 and Table S2). The 3 largest reported flood volumes of 71.6, 19.5, and 17.2 × 106 m3 from the lakes Sangwang Tsho (1954), Sabai Tsho (1998), and Lugge Tsho (1994), respectively, had return periods of 237, 56, and 49 y, respectively, according to our predictions. The highest reported peak discharge (15,920 m3⋅s−1) drained from Lake Zhangzangbo in 1981; we estimate this as a 100-y event in the greater Himalayan region. The lakes Sangwang Tsho and Sabai Tsho had similar high peak discharges of ∼10,000 m3⋅s−1, corresponding to a return period of 60 y. Yet reported values of V0 and Qp rely chiefly on point estimates from empirical rating curves, eyewitness accounts, flood marks, and transported clasts in river channels, or measurements several kilometers downstream of the failing dams (28), thus compromising detailed, site-specific validation of our regional predictions. These uncertainties cause some of the scatter in the data that we based our models on (SI Appendix, Figs. S4 and S5). However, our approach explicitly propagates these uncertainties and robustly estimates V0 and Qp from the distribution of meltwater lake areas in the entire Himalayan region. The size of glacier lakes will remain the key determinant of GLOF magnitude, regardless of whether we use alternative discharge rating curves (SI Appendix, Fig. S7), more elaborate numerical dam breach simulations (29), or any other metric of flood potential (20).

Our study objectively enriches previous qualitative appraisals, which contrasted in the degree and number of “potentially dangerous” Himalayan lakes (22). The tails of the frequency−size distributions (Fig. 2) contain valuable information for practitioners regarding the physically possible margins of V0 and Qp in the Himalayas. We note that half of the total Himalayan lake volume (20.1+2.4/−2.1 km3) is in the largest 1% of glacier lakes (SI Appendix, Fig. S8). For example, Sangwang Tsho—the largest Himalayan moraine-dammed lake today—accounts for 5% of the total glacier lake volume (∼1 km3) and could release a flood with a return period of 5,000+1,400/−1,000 y, should this volume drain entirely (SI Appendix, Fig. S9). Such flood magnitudes and associated return periods are consistent with reports on Holocene flood volumes up to 3 orders of magnitude larger in the eastern Himalayas (30).

Himalayan glacier lakes are currently limited in their storage capacity to produce floods of these dimensions, particularly in the Hindu Kush, Karakoram, and Western Himalayas, where lakes are smallest today (Figs. 1 and 2 and SI Appendix, Fig. S8). Why glacier lakes occur in clusters and have become largest in the Central and Eastern Himalayas since 1990 (+7.7 to +23% in area) remains debated (19). Glaciers have had negative mass balances in all regions except the Karakoram since the 1970s at least (31), while the highest ice losses in the 21st century were in the Western Himalaya and the Nyainqentanglha (32). The Central and Eastern Himalayas have a high proportion of lakes in direct contact with debris-covered parent glaciers, possibly accelerating glacier mass loss and lake growth (33). The increasing trend of air temperature is consistent over the entire Himalayas, whereas changes in precipitation were mostly insignificant (34), so that the clustering of lakes today may be tied to local, less well-known, controls such as glacier bed topography or valley geometry (35).

Yet the distribution of glacier lakes will likely change in the future, given that a global temperature rise of 1.5 °C could melt half of the Himalayan glacier mass by the end of the 21st century (36). Models of subglacial topography suggest that a complete melting of all glaciers might provide accommodation space for another 16,000 meltwater lakes (>104 m2) with a maximum total volume of 120 km3 (37), hence possibly increasing the current lake volume 6-fold. According to these projections, most of these futures lakes could form in the Karakoram and Western Himalayas, where contemporary glacier cover is highest (13). Yet the errors of the inferred bathymetries can involve tens of meters, and many lakes might fill bedrock depressions that are less prone to catastrophic outbursts. Future flood volumes may increase nevertheless, especially in regions with large ice volumes and few lakes, even if only a fraction of the total meltwater will be trapped by moraines. Regional GLOF hazard could thus change commensurately, should annual GLOF frequencies rise with a growing lake abundance in the future (16). Whether lake outbursts will become more frequent with atmospheric warming remains an open question, however. The average rate of GLOFs in the greater Himalayan region has remained unchanged in the past 3 decades (23), showing that rapid growth of glacier lakes alone is an unsuitable predictor for GLOF activity, let alone GLOF hazard (38, 39).

Both the magnitude and frequency of outburst floods are straightforward to change in our model, motivating a more dynamic assessment with regular updates of outburst frequency and lake size distribution. We also encourage future work to learn more about the triggers and drivers of historic GLOFs. With more of this information becoming available, we can improve our Bayesian framework by assigning more informed (and appropriately weighted) prior probabilities of outburst to each glacier lake. In this spirit, we offer a practical tool that is extensible and compatible with flood routing models, design codes, and hazard mitigation. Our appraisal of GLOF hazard complements projections of meteorological flood hazards in a warming climate for the sparsely instrumented Himalayan drainage network. Atmospheric warming is projected to increase mean daily and annual discharges in the Indus, Ganges, and Brahmaputra rivers only by a few percent in this century (40, 41), although the return periods for a given flood stage might drop by 50 to 90% in these rivers in the 21st century. Extreme runoff in headwaters (1), and GLOFs in particular (12), has eluded such projections. We show that flood hazard due to glacier melt requires urgent attention in light of the rapidly growing population, infrastructure, and hydropower projects in the Himalayas (3, 12). Our appraisal adds to recent calls toward identifying regions that are most prone to GLOF impacts, and complements integrative concepts for climate risk adaptation on local, national, or regional levels (42).

Materials and Methods

Inventory of Moraine-Dammed Glacier Lakes.

We use glacier lake and meltwater lake synonymously for water bodies fed by glacier meltwater, snow, and ice as defined in ref. 21. This database is the only consistent, highly accurate glacier lake inventory for our study region, containing a total of 25,614 manually mapped lakes from Landsat images between 2003 and 2007. We extracted all (n = 5,184) moraine-dammed glacier lakes >0.01 km2 for our 7 subregions, which follow the glacier regions in the Randolph Glacier Inventory. We slightly modified the outlines of the Central and Eastern Himalayas to include glaciers and associated glacier lakes facing toward the Tibetan Plateau.

Estimating Depths, Volumes, and Flood Volumes of Glacier Lakes.

Global samples from glacier lakes have suggested that glacier depths can vary by one order of magnitude for a given lake area (43). To estimate glacier lake volumes in our study region, we compiled data from bathymetric surveys of 24 Himalayan glacier lakes with reported lake areas and maximum depths (SI Appendix, Table S1). We used a Bayesian robust linear regression with a normally distributed target variable (lake depth) to account for possible effects of the small sample size and outliers in our data (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A): , where the mean is a linear combination of input (lake area) with intercept and slope ; the precision (the inverse of variance) is gamma-distributed , here with equal shape and rate parameters. We numerically approximated all posterior distributions with a Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling scheme implemented in the JAGS language (implemented in the package rjags (44) in the statistical programming software R) with 3 parallel chains of 100,000 iterations and a burn-in of 2,000 steps with no thinning. We sampled 1,000 pairs of and from the posterior distributions to generate predictive posteriors of lake depth for each lake, curtailed at the 95% highest density interval (HDI) (SI Appendix, Fig. S2).

We assumed that the manually mapped glacier lake areas are circular, so that the radius of any lake is described as a function of the lake area : . We obtained 1,000 estimates of total volume for each glacier lake assuming an ellipsoidal bathymetry: , where values of are 1,000 samples from the predicted posterior distribution of lake depth. Hence, the volume that remains in a lake after an outburst can be described by a capped ellipsoid , where is the depth of the capped ellipsoid (i.e., the depth of the remaining lake after the GLOF). We finally calculated the flood volume as by increasing in 1% steps from 0.01 up to the total lake depth , so that we obtained 100,000 samples of for any given lake.

Estimating Peak Discharge.

Walder and O’Connor (24) proposed a physically motivated model that predicts peak discharge Qp during natural dam failure, based on the breach rate, breach depth, and volume of water released. They compiled data from 63 observed natural dam breaks in diverse settings, and found that the largest values of Qp arise from dam breaches that fully develop before the lake level drops substantially. Such large impoundments involve either large lake volumes relative to the breach depth or very rapid dam failure. In contrast, mountain valleys mostly store smaller volumes even behind high dams, so that peak discharge often occurs prior to complete dam incision (24). These 2 end members make up a constant response of dimensionless peak discharge Qp* when plotted against the dimensionless product η of lake volume and breach rate (24) (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). From equations for critical flow, Walder and O’Connor inferred a model with the 2 key components dimensionless peak discharge

| [1] |

and

| [2] |

where is the dimensionless flood volume, is the dimensionless breach rate, is the acceleration by gravity (meters per square second), is the breach depth (meters), and is the released water volume (cubic meters). The breach rate (meters per second) subsumes lithologic conditions, the erodibility of the outflow channel, and the breach and downstream valley geometry, and has a reported range of 2.5 orders of magnitude (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). The capped values of Qp* express the model’s idea that breach conditions primarily control peak discharge, so that outflow deceleration or downstream ponding limit any further increase in discharge for a given breach geometry.

The empirical data support a piecewise regression model of the form (where and are the regression parameters) for < , and is constant for > . However, the transition between the segments of the models is ill-defined (∼−1 < < ∼0.5) and located where the data density is highest (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). To better constrain this transition and to explicitly treat all other uncertainties, we learned a Bayesian piecewise robust model from these empirical data (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B). We assumed a Student’s distributed noise to make our regression robust against outliers, and specified the likelihood of observing the data from the piecewise model as

| [3] |

with , where is the conditional mean of the -distributed data at input location , σ is the scale parameter, specifies the degrees of freedom, is the regression intercept, is the regression slope, is the indicator function, is the breakpoint linking the 2 piecewise segments of the regression model, and is the number of data points. Following Bayes’ Rule, we obtained the joint posterior distribution by multiplying this likelihood with the joint prior distribution that we modeled as the product of independent distributions,

| [4] |

where we encoded our prior assumptions about the regression parameters as and . The parameters of these Gaussian priors refer to standardized data pairs of and (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). We further specified a half-Cauchy prior on the scale parameter where ≥ 0, and a truncated Gaussian on the breakpoint where ; this range is largely informed by the location of the suspected break point at ∼0.6 < < ∼1 for the empirical, nonstandardized values of (24). We fixed the degrees of freedom in the t-distributed piecewise model at a low value of = 10 to impose taller tails on the regression coefficients, hence making it more robust against outliers. We used a numerical sampling scheme implemented in the Stan programming language that relies on MCMC to approximate the marginal posterior distributions of , , , and in 5 parallel chains of 12,500 samples each.

We integrated out these parameters to simulate draws from the predictive posterior distribution for unobserved inputs, so that we can predict for any given value of of each of the 5,184 moraine-dammed lakes in our study area. Values of from individual lakes encompass the estimated flood volumes V0 and 100 physically plausible values of the breach rate based on a log-normal fit to reported breach rates (24) (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). We allowed for twice the range of documented breach rates to account for the effects of failure mechanisms that may have remained unobserved. Multiplying 105 samples of V0 with 100 samples of finally resulted in a total of 107 scenarios of per lake. Given the variance in the data that we learned our model from, distributions of peak discharge commonly embrace 4 to 6 orders of magnitude for a given lake; we report the 95% HDI for these distributions.

Estimating GLOF Return Periods.

We used the posterior estimates of to model their average return periods using extreme-value theory (SI Appendix, Fig. S1C). The Generalized Pareto (GP) distribution has been widely used to characterize the distribution of quantities recorded above a high threshold (also known as the peak-over-threshold or partial duration series method), and has the probability density

| [5] |

where is a location parameter, ≥ 0 is a scale parameter, and is a shape parameter for . For ≥ 0, the distribution is heavy-tailed, but collapses to an exponential distribution for the limiting case of = 0. For negative , the distribution has a thin upper bounded tail. The quantiles of the GP distribution can be interpreted as exceedance probabilities, or, inversely, return periods of return levels of at least size .

We further assumed that GLOFs occur in time according to a Poisson process with rate , so that the time intervals between any 2 subsequent, independent GLOFs are exponentially distributed. Here is a scaling constant to adjust to the period of interest for recording peak-over-threshold values. Assuming a 2-dimensional process in and , we can write the log-likelihood for observing data exceeding the threshold as

| [6] |

where the terms on the right-hand side containing denote the time component, and . Hence, we obtained the log joint posterior distribution by adding the log joint prior distribution of the parameters. Again, we treated these priors as independent of each other,

| [7] |

We obtained the mean annual GLOF rate in a given region from remote sensing-based analyses covering the past 3 decades (23, 45). These studies detected 38 GLOFs in 30 y (1988–2017), and demonstrated that the mean annual rate of GLOFs remained unchanged over this period, both in the entire Himalayas and in its 7 subregions. We thus assumed constant posterior annual GLOF rates (brown numbers in Fig. 3 and SI Appendix, Fig. S6) in any region, motivating a Poisson-distributed occurrence of GLOFs in time. To estimate GLOF return periods, we created a mixture distribution and from the posterior distributions, and , respectively, from all lakes in a given region. We assigned equal weights to each realization from the posterior distributions, so that for and . We thus assumed that each lake is equally likely to experience a sudden outburst in our predictive model. Given more data about trigger and dam failure mechanisms, our mixture model is flexible enough to assign weights of outburst susceptibility to the lakes.

We used the mean regional GLOF rate (i.e., adjusted by the historic GLOF count from each region in 30 y) to simulate 10,000 y of data from the mixed posterior predictive distribution of and (SI Appendix, Fig. S1C). We fitted a GP model to these time series with an MCMC sampler implemented in the package extRemes (46) in the statistical programming language R. We found predictions to be robust for upper quartile thresholds and used the 80th percentiles of the data as thresholds eventually, adjusting regional estimates by the appropriate regional values of . We repeated this sampling scheme 1,000 times for all Himalayan regions and report the mean from all average return periods and their 95% HDI. By design of our extreme-value model, changes in annual GLOF rates directly change return periods (SI Appendix, Figs. S10 and S11): For example, a doubling of GLOF frequency in a given period shortens the return period of this flood volumes or discharge level by one-half.

Data and Code Availability.

All input data are available at Zenodo (http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3523213), and model codes are available at GitHub (https://github.com/geveh/GLOFhazard).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft within the graduate research training group NatRiskChange (Grant GRK 2043/1) at the University of Potsdam (https://www.uni-potsdam.de/natriskchange). We performed our spatial analysis using the System for Automated Geoscientific Analyses (SAGA V. 2.2.0 and 7.3.0) and ArcGIS (V. 10.5), and performed the statistical analyses with R (http://www.r-project.org/) and the probabilistic programming language Stan (https://mc-stan.org/). We thank Kristin Vogel for comments on an early version of this manuscript.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: All input data are available at Zenodo (http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3523213), and model codes are available at GitHub (https://github.com/geveh/GLOFhazard).

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1914898117/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Wijngaard R. R., et al. , Future changes in hydro-climatic extremes in the Upper Indus, Ganges, and Brahmaputra River basins. PLoS One 12, e0190224 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirabayashi Y., et al. , Global flood risk under climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 3, 816–821 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wester P., Mishra A., Mukherji A., Shrestha A. B., Eds., The Hindu Kush Himalaya Assessment: Mountains, Climate Change, Sustainability and People (Springer International, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cook K. L., Andermann C., Gimbert F., Adhikari B. R., Hovius N., Glacial lake outburst floods as drivers of fluvial erosion in the Himalaya. Science 362, 53–57 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cenderelli D. A., Wohl E. E., Peak discharge estimates of glacial-lake outburst floods and “normal” climatic floods in the Mount Everest region, Nepal. Geomorphology 40, 57–90 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Osti R., Egashira S., Hydrodynamic characteristics of the Tam Pokhari glacial lake outburst flood in the Mt. Everest region, Nepal. Hydrol. Processes 23, 2943–2955 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richardson S. D., Reynolds J. M., An overview of glacial hazards in the Himalayas. Quat. Int. 65, 31–47 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Westoby M. J., et al. , Modelling outburst floods from moraine-dammed glacial lakes. Earth Sci. Rev. 134, 137–159 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Emmer A., Vilímek V., Review article: Lake and breach hazard assessment for moraine-dammed lakes: An example from the Cordillera Blanca (Peru). Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 13, 1551–1565 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allen S. K., Rastner P., Arora M., Huggel C., Stoffel M., Lake outburst and debris flow disaster at Kedarnath, June 2013: Hydrometeorological triggering and topographic predisposition. Landslides 13, 1479–1491 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watanbe T., Rothacher D., The 1994 Lugge Tsho Glacial Lake Outburst flood, Bhutan Himalaya. Mt. Res. Dev. 16, 77–81 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwanghart W., Worni R., Huggel C., Stoffel M., Korup O., Uncertainty in the Himalayan energy–water nexus: Estimating regional exposure to glacial lake outburst floods. Environ. Res. Lett. 11, 074005 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bolch T., et al. , The state and fate of Himalayan glaciers. Science 336, 310–314 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bajracharya S. R., Mool P., Glaciers, glacial lakes and glacial lake outburst floods in the Mount Everest region, Nepal. Ann. Glaciol. 50, 81–86 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nie Y., et al. , An inventory of historical glacial lake outburst floods in the Himalayas based on remote sensing observations and geomorphological analysis. Geomorphology 308, 91–106 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harrison S., et al. , Climate change and the global pattern of moraine-dammed glacial lake outburst floods. Cryosphere 12, 1195–1209 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carrivick J. L., Tweed F. S., A global assessment of the societal impacts of glacier outburst floods. Global Planet. Change 144, 1–16 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang X., et al. , An approach for estimating the breach probabilities of moraine-dammed lakes in the Chinese Himalayas using remote-sensing data. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 12, 3109–3122 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nie Y., A regional-scale assessment of Himalayan glacial lake changes using satellite observations from 1990 to 2015. Remote Sens. Environ. 189, 1–13 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fujita K., et al. , Potential flood volume of Himalayan glacial lakes. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 13, 1827–1839 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maharjan S. B., et al. , “The status of Glacial Lakes in the Hindu Kush Himalaya” (ICIMOD Res. Rep. 2018/1, International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development, 2018).

- 22.Rounce D. R., McKinney D. C., Lala J. M., Byers A. C., Watson C. S., A new remote hazard and risk assessment framework for glacial lakes in the Nepal Himalaya. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 20, 3455–3475 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Veh G., Korup O., von Specht S., Roessner S., Walz A., Unchanged frequency of moraine-dammed glacial lake outburst floods in the Himalaya. Nat. Clim. Chang. 9, 379–383 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walder J. S., O’Connor J. E., Methods for predicting peak discharge of floods caused by failure of natural and constructed earthen dams. Water Resour. Res. 33, 2337–2348 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Connor J. E., Beebee R. A., “Floods from natural rock-material dams” in Megaflooding on Earth and Mars, Burr D. M., Carling P. A., Baker V. R., Eds. (Cambridge University Press, 2009), pp. 128–171. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Veh G., Korup O., Walz A., “Supplementary data: Hazard from Himalayan glacier lake outburst floods.” Zenodo. 10.5281/zenodo.3523213. Deposited 30 October 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Veh G., Korup O., Walz A., “Code repository: GLOFhazard.” GitHub. https://github.com/geveh/GLOFhazard. Deposited 30 October 2019.

- 28.Korup O., Tweed F., Ice, moraine, and landslide dams in mountainous terrain. Quat. Sci. Rev. 26, 3406–3422 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Westoby M. J., et al. , Numerical modelling of glacial lake outburst floods using physically based dam-breach models. Earth Surf. Dyn. 3, 171–199 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Montgomery D. R., et al. , Evidence for Holocene megafloods down the Tsangpo River gorge, southeastern Tibet. Quat. Res. 62, 201–207 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bolch T., et al. , “Status and change of the cryosphere in the Extended Hindu Kush Himalaya Region” in The Hindu Kush Himalaya Assessment, (Springer, 2019), pp. 209–255. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brun F., Berthier E., Wagnon P., Kääb A., Treichler D., A spatially resolved estimate of High Mountain Asia glacier mass balances, 2000-2016. Nat. Geosci. 10, 668–673 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Song C., et al. , Heterogeneous glacial lake changes and links of lake expansions to the rapid thinning of adjacent glacier termini in the Himalayas. Geomorphology 280, 30–38 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maurer J. M., Schaefer J. M., Rupper S., Corley A., Acceleration of ice loss across the Himalayas over the past 40 years. Sci. Adv. 5, eaav7266 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.King O., Dehecq A., Quincey D., Carrivick J., Contrasting geometric and dynamic evolution of lake and land-terminating glaciers in the central Himalaya. Global Planet. Change 167, 46–60 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kraaijenbrink P. D. A., Bierkens M. F. P., Lutz A. F., Immerzeel W. W., Impact of a global temperature rise of 1.5 degrees Celsius on Asia’s glaciers. Nature 549, 257–260 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Linsbauer A., et al. , Modelling glacier-bed overdeepenings and possible future lakes for the glaciers in the Himalaya−Karakoram region. Ann. Glaciol. 57, 119–130 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fujita K., Sakai A., Nuimura T., Yamaguchi S., Sharma R. R., Recent changes in Imja Glacial Lake and its damming moraine in the Nepal Himalaya revealed by in situ surveys and multi-temporal ASTER imagery. Environ. Res. Lett. 4, 045205 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Benn D. I., et al. , Response of debris-covered glaciers in the Mount Everest region to recent warming, and implications for outburst flood hazards. Earth Sci. Rev. 114, 156–174 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nepal S., Shrestha A. B., Impact of climate change on the hydrological regime of the Indus, Ganges and Brahmaputra river basins: A review of the literature. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 31, 201–218 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lutz A. F., Immerzeel W. W., Shrestha A. B., Bierkens M. F. P., Consistent increase in High Asia’s runoff due to increasing glacier melt and precipitation. Nat. Clim. Chang. 4, 587–592 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Allen S. K., et al. , Translating the concept of climate risk into an assessment framework to inform adaptation planning: Insights from a pilot study of flood risk in Himachal Pradesh, Northern India. Environ. Sci. Policy 87, 1–10 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cook S. J., Quincey D. J., Estimating the volume of Alpine glacial lakes. Earth Surf. Dyn. 3, 559–575 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Plummer M., Package ‘rjags’- Bayesian Graphical Models using MCMC (Version 4-8, 2018).

- 45.Veh G., Korup O., Roessner S., Walz A., Detecting Himalayan glacial lake outburst floods from Landsat time series. Remote Sens. Environ. 207, 84–97 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gilleland E., Katz R. W., extRemes 2.0: An extreme value analysis package in R. J. Stat. Softw. 72, 1–39 (2016). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All input data are available at Zenodo (http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3523213), and model codes are available at GitHub (https://github.com/geveh/GLOFhazard).