Abstract

Vavilovia formosa is a relict leguminous plant growing in hard-to-reach habitats in the rocky highlands of the Caucasus and Middle East, and it is considered as the putative closest living relative of the last common ancestor (LCA) of the Fabeae tribe. Symbionts of Vavilovia belonging to Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae compose a discrete group that differs from the other strains, especially in the nucleotide sequences of the symbiotically specialised (sym) genes. Comparison of the genomes of Vavilovia strains with the reference group composed of R. leguminosarum bv. viciae strains isolated from Pisum and Vicia demonstrated that the vavilovia strains have a set of genomic features, probably indicating the important stages of microevolution of the symbiotic system. Specifically, symbionts of Vavilovia (considered as an ancestral group) demonstrated a scattered arrangement of sym genes (>90 kb cluster on pSym), with the location of nodT gene outside of the other nod operons, the presence of nodX and fixW, and the absence of chromosomal fixNOPQ copies. In contrast, the reference (derived) group harboured sym genes as a compact cluster (<60 kb) on a single pSym, lacking nodX and fixW, with nodT between nodN and nodO, and possessing chromosomal fixNOPQ copies. The TOM strain, obtained from nodules of the primitive “Afghan” peas, occupied an intermediate position because it has the chromosomal fixNOPQ copy, while the other features, the most important of which is presence of nodX and fixW, were similar to the Vavilovia strains. We suggest that genome evolution from the ancestral to the derived R. leguminosarum bv. viciae groups follows the “gain-and-loss of sym genes” and the “compaction of sym cluster” strategies, which are common for the macro-evolutionary and micro-evolutionary processes. The revealed genomic features are in concordance with a relict status of the vavilovia strains, indicating that V. formosa coexists with ancestral microsymbionts, which are presumably close to the LCA of R. leguminosarum bv. viciae.

Keywords: Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar viciae, genomic rearrangements, symbiotic and housekeeping genes, evolution of symbiosis, last common ancestor (LCA), Vavilovia formosa, horizontal gene transfer

1. Introduction

Root nodule bacteria (rhizobia), N2-fixing symbionts of leguminous plants (the Fabaceae), represent a highly developed model for the evolutionary genetics of symbiosis. These bacteria demonstrate a polyphyletic origin, including about a dozen families and over a hundred species, mostly α-proteobacteria (Rhizobiales) and some β-proteobacteria (e.g., Paraburkholderia) [1,2]. The following three major categories of symbiotically specialised (sym) genes having different origins were revealed in rhizobia: nod (synthesis of chito-oligosaccharide signalling Nod factors, inducing nodule development) [3,4,5], nif (synthesis of nitrogenase) [5], and fix (energy supply to nitrogenase and regulation of nif genes) [5,6]. Formation of sym gene systems is dependent on rearrangements (duplication, neo-functionalisation, horizontal transfer) of genes that encode for different signalling and metabolic functions in the rhizobia ancestors.

Evolutionarily, rhizobia species diversity may be classified into the following two categories: (i) primary (ancestral) species, originating directly from non-symbiotic diazotrophes via genomic rearrangements, resulting in the formation of the sym (nod + nif/fix) gene systems; and (ii) secondary (derived) species, originating via the transfer of sym genes into various free-living bacteria [7].

The primary rhizobia are presumably represented by slow-growing Bradyrhizobium species close to the free-living phototroph Rhodopseudomonas, which acquired the ability for in planta N2 fixation by allocating some photosynthesis-controlling genes into the nitrogenase-controlling fix network [8]. This reorganisation resulted in the photosynthetically active Bradyrhizobium spp. genotypes, nodulating the stems of some tropical legumes (Aeschynomene, Neptunia, and Sesbania) without use of the nod genes that encode for the lipo–chito–oligosaccharide Nod factors (NFs) typical of the majority of rhizobia. NF synthesis has been acquired by the root-nodulating species (e.g., Bradyrhizobium japonicum, B. elkanii), in which the phototrophy was functionally substituted by the ability to use the plant photosynthesis products. These heterotrophic rhizobia usually retain the ability to express nif genes ex planta, but they are not capable of diazotrophic growth due to low free-living nitrogenase activity [9].

The best studied secondary rhizobia are represented by the Rhizobiaceae species (e.g., Rhizobium, Sinorhizobium, and Neorhizobium) close to Agrobacterium, which is often considered as the same genus with Rhizobium. These bacteria are devoid of photosynthesis and of the ability to express nitrogenase genes ex planta, suggesting their origin via horizontal transfer of sym genes from primary rhizobia to various heterotrophic soil and plant-associated bacteria.

Two genetic strategies may be revealed for rhizobia macroevolution: gain-and-loss of sym genes and genomic compaction of sym gene arrangement.

Gain of new genes from non-symbiotic networks occurred via horizontal gene transfer (HGT) and duplication–divergence (DD) mechanisms. In addition to the abovementioned fix genes, many nod genes were recruited via the latter mechanism. For example, nodD was obviously derived from the lysM-araC family of transcriptional regulators by acquiring the ability to recognise the plant-released flavonoids responsible for activation of the nod regulon [10].

Gene loss may be illustrated by nifV, which was revealed in phototrophic Bradyrhizobium genotypes, but it is absent in heterotrophic ones. This gene encodes for homocitrate synthesis, which is the precursor of the MoFe-cofactor of nitrogenase. In the majority of legume–rhizobia symbioses, this synthesis is controlled by plant genes (e.g., by FEN1 in Lotus japonicus) since their inactivation results in the loss of symbiotic N2 fixation, which may be restored after introduction of nifV into the Lotus-nodulating rhizobia [11].

Compaction of sym genes arrangement has been indicated in primary rhizobia. While the majority of Bradyrhizobium strains harbour these genes in several non-linked chromosomal loci, in some strains these genes are concentrated on symbiotic plasmids (pSyms) [12]. A more compact arrangement was found in Mesorhizobium species, which presumably originated from sym gene transfer into Phyllobacteriaceae strains [7]. In meshorhizobia, sym genes are usually concentrated in the mobile chromosomal islands, which may be readily transferred in the bacterial populations as conjugative transposons [13]. An important factor that ensures increased mobility of sym genes is their extra-chromosomal (on large plasmids or on chromids) location typical for the Rhizobiaceae species [14].

In contrast to macroevolution that occurs at the super-species level, microevolution of the sym gene system that occurs at the intra-species level is poorly studied. To close this gap, we developed the model represented by the Fabeae tribe, which is a predominantly temperate-zone legume group (includes genera Lathyrus, Lens, Pisum, Vavilovia, and Vicia) infected by fast-growing rhizobia, R. leguminosarum bv. viciae [15,16]. V. formosa (vavilovia) is a relict plant that grows on rocks and steep screes (Figure 1) in the hard-to-reach habitats of the Caucasus mountains and in the Middle East at altitudes of 1500–3500 m. Based on morphological and genetic features, V. formosa is considered the putative closest living relative of the last common ancestor (LCA) of the Fabeae tribe [17]. Importantly, the vavilovia’s area of growth overlaps the Middle East Centre of Pisum origin, where the wild-growing pea genotypes are distributed. Specifically, primitive “Afghan” pea lines represent the evolutionary precursors for cultural (European) lines [18], which underwent the prolonged domestication and breeding histories and probably represent a “derived” P. sativum germplasm. The remarkable feature of vavilovia’s symbionts is the uniform presence of the gene nodX [19,20], which is essential for nodulation of “Afghan” pea lines, but it is not required for European pea nodulation [21]. The tube test showed that vavilovia belongs to the same cross-inoculation group as the pea, vetch, lentil, and vetchling [19].

Figure 1.

V. formosa in its natural habitat in Dagestan. Photo © Alexander Ivanov (North-Caucasus Federal University, Russia).

Previously, Kimeklis et al. [19,22] showed that at the gene level (especially in sym genes) rhizobia isolated from Vavilovia nodules represent a well-defined group within R. leguminosarum bv. viciae, which is genetically different from the strains isolated from Pisum and Vicia species. Considering the presumed ancestral status of vavilovia, its proximity to the LCA of the Fabeae tribe, and its long-term ecological isolation of vavilovia’s symbionts [19], we can expect that vavilovia could also support the ancestral symbionts closely related to the LCA of R. leguminosarum bv. viciae. We hypothesised that evolution from the ancient to derived R. leguminosarum bv. viciae groups follows the tendencies revealed earlier for rhizobia macroevolution, the “gain-and-loss of sym genes” and the “compaction of sym cluster”. Identification of ancestral features at the genomic level and revealing the tendencies in the micro-evolution of sym genes system in R. leguminosarum bv. viciae required to probe this hypothesis represented the priorities of our research.

2. Materials and Methods

R. leguminosarum bv. viciae strains were isolated from root nodules of V. formosa growing in the Caucasus mountains in the regions of North Ossetia (strains Vaf-10 and Vaf-12) and Dagestan (strain Vaf-108) [16,20]. Strains were isolated by the standard method [23]. The rhizobia strains were grown on 79 medium at 28 °C. DNA was extracted according to the standard procedure [24], with an additional treatment with proteinase K.

All isolates are deposited in the Russian Collection of Agricultural Microorganisms (RCAM) and stored at –80°C in the automated Tube Store (Liconic Instruments, Lichtenstein) [25]. Information about these strains is available in the online RCAM database [26].

Sequencing of the Vaf-12 strain was performed on a MiSeq genomic sequencer (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, United States), according to the manufacturer’s protocol, using the MiSeq Reagent Kit, 600 Cycles (Illumina, United States) at the Genomics Core Facility, Siberian Branch, Russian Academy of Sciences (Institute of Chemical Biology and Fundamental Medicine, Novosibirsk). Sequencing of strains Vaf-10 and Vaf-108 was performed on a Pacbio RSII instrument with P6 in two SMRT cells (Pacific Biosciences of California, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, United States). PacBio sequencing and subsequent error correction analysis and assembly were performed at the Arizona Genomics Institute (US).

Genomes, sequenced with Illumina, were assembled de novo using SPAdes 3.11.1 software [27]. Quality control was performed by QUAST 3.0 [28]. Genomes, sequenced with PacBio, were assembled using HGAP 3 software [29]. Genomes of all strains were annotated with the RAST online tool [30]. Extraction of gene sequences and other operations with them were performed using CLC Genomics Workbench 7.5.1 software. Functional classification (Clusters of Orthologous Groups, COG) was performed using WebMGA [31].

For all PacBio strains (Vaf-10, Vaf-108), we got the perfectly assembled big circular contigs or chromosomes (GenBank Accessions: CP016286, CP018228) and the smaller circular contigs, presumably conforming to plasmids (CP016287-CP01629, CP018229-CP018236). Strain Vaf-12, sequenced with Illumina technology, was analysed as individual contigs (LVYU01000001-LVYU01000166). The symbiotic region of strain Vaf-12 was assembled from individual contigs by polymerase chain reaction and Sanger sequencing gap filling (scaffold KT944070).

The full set of genes for nodulation and N2 fixation was found in the sequenced strains, which confirmed that R. leguminosarum is the main, but not only [16], symbiont of vavilovia. The symbiotic properties towards the Fabeae legumes of these strains was also confirmed by the tube test [19].

For the detailed genome comparison, we used a set of complete genomes available from GenBank, belonging to R. leguminosarum bv. viciae strains 3841, 248, WSM1481, and TOM, isolated from P. sativum and Vicia faba (Table 1). For the brief genome screening, we used all R. leguminosarum bv. viciae genomes available in GenBank, mostly draft genomes (64 genomes in total, including 4 previously mentioned strains).

Table 1.

Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae strains used in this study and genome statistics.

| Strain | Region | Host Plant | Accession No. (GenBank) | Genome Size, Mb | No. of Contigs/Replicons | No. of Annotated Genes | GC% | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaf-12 | North Ossetia, Russia | V. formosa |

LVYU01000001-LVYU01000166—whole genome KT944070—Sym region only |

7.666 | 166 | 7543 | 60.70 | [32] |

| Vaf-10 | North Ossetia, Russia | V. formosa | CP016286-CP016293 | 8.568 | 8 | 8559 | 60.53 | Current work |

| Vaf-108 | Dagestan, Russia | V. formosa | CP018228-CP018236 | 8.447 | 9 | 8320 | 60.50 | Current work |

| TOM | Turkey | P. sativum Afg | AQUC01000001-AQUC01000006 | 7.358 | 6 | 7192 | 60.80 | [33] |

| 3841 | UK | P. sativum | AM236080-AM236086 | 7.751 | 7 | 7599 | 60.87 | [34] |

| 248 | UK | V. faba | ARRT01000001-ARRT01000007 | 7.289 | 7 | 7148 | 60.90 | [33] |

| WSM1481 | Greece | V. faba | AQUM01000001-AQUM01000006 | 7.556 | 6 | 7452 | 61.00 | [33] |

Reconstruction of phylogeny was performed by the maximum likelihood method and checked via a bootstrap test (500 replicas) with MEGA6 [35], as well as estimation of evolutionary distances between sequences. 16S rRNA sequencing of the strains obtained from V. formosa nodules showed their similarity to the R. leguminosarum bv. viciae species [16].

For metatree construction the phylogenetic trees were built for each of the sym genes present in all strains (32 trees in total). Their topologies were compared pairwise via the Compare2Trees tool [36], and the numerical expression of similarities of topologies were obtained. The matrix of similarities was converted to the matrix of differences, then the metatree was built on a pairwise distance matrix using MEGA6.

Average nucleotide identity (ANI) and ANI-distance clustering were performed with an ANI/AAI-Matrix Calculator [37]. Genome alignment for comparison for genomes and inter-sym-gene region structures was performed by Mauve 2.4.0 [38].

The search for core and accessory components of genomes was performed by Roary [39,40]. According to the “Roary” author recommendations, all genomes for pan-genome analysis were annotated by Prokka [41].

3. Results

We analysed the micro-evolutionary variation of sym gene arrangement in R. leguminosarum bv. viciae strains isolated from ancestral (Vavilovia) and derived (Pisum and Vicia) species of the Fabeae tribe. The presented results are interesting in the context of the major tendencies previously revealed for rhizobia macroevolution: “gain-and-loss of sym genes” and “compaction of sym gene clusters”.

3.1. Vavilovia’s Isolates in Context of Core Genome of R. leguminosarum bv. viciae

We analysed vavilovia’s isolates in context of their position among R. leguminosarum strains. Phylogenies of concatenates of house-keeping genes (16S rRNA, dnaK, glnA, and gsII) showed no apparent differentiation of Vaf from the reference groups (Figure S1). In a parallel article, Kimeklis et al. discusses in detail the position of vavilovia’s strains in R. leguminosarum [19]. Whole genome ANI shows at least 94.2% genome identity (Table S1) and chromosomal ANI shows at least 94.5% identity (Table S2) to derived strains, which are the same as within derived strains. Phylogenetic tree based on whole genome and chromosomal ANI results also shows no differentiation of Vaf strains from the reference group (Figure S2).

The search for core and accessory genome fraction showed 9918 gene clusters among 7 strains. A total of 3817 of them are common for all genomes, and remaining 6101 genes are present in 6 or fewer genomes. More detailed statistics is presented in Table S3 and Figure S3.

3.2. Variability of the Sym Gene Arrangement

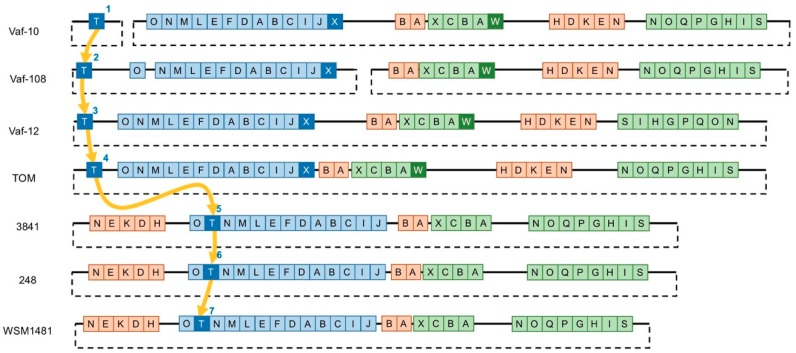

We compared the Sym regions of vavilovia’s strains Vaf-10, Vaf-12, and Vaf-108 and of the R. leguminosarum bv. viciae reference strains (Figure 2). PacBio data demonstrated that unlike the reference group, sym genes of Vaf-108 and Vaf-10 are assembled in two different circular contigs, likely plasmids. In Vaf-108, the Sym region is probably split between two replicons, one with nod genes and the other with nif/fix genes. In Vaf-10, the nodT gene is separated from the other sym genes into a plasmid lacking any other sym genes. In Vaf-12, the symbiotic region demonstrates an ordinary architecture, when all sym genes form the single extrachromosomal cluster. Since this split is only probable, we will not discuss this feature further.

Figure 2.

Schematic structure of R. leguminosarum Sym regions. Blue, nod genes; orange, nif genes; green, fix genes. The arrows demonstrate the probable pathway of nodT evolutionary migration into the sym cluster. Coordinates of regions are performed in Figure S4.

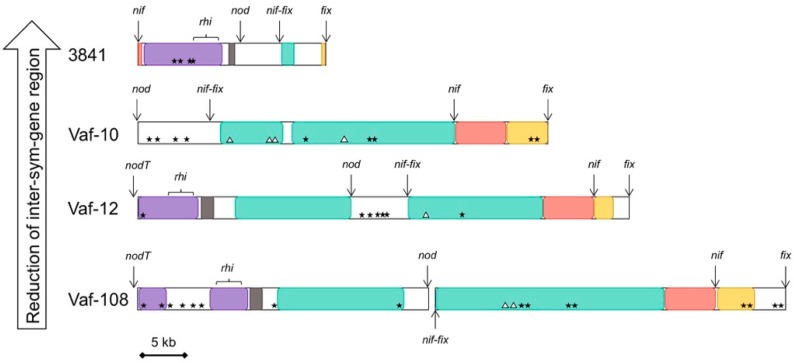

In addition to full-size sym genes, the small (150–200 bp) fragments of nifH (in strains Vaf-10 and Vaf-12), fixP (in Vaf-10 and Vaf-108), and fixG (in Vaf-10 and Vaf-108) were identified in the intergenic regions (Figure 3). Analysis of their similarity to the full-size homologs within the same genome revealed 5%–15% nucleotide substitutions.

Figure 3.

Structural and functional organisation of inter-sym-gene regions (Sym regions with excluded sym genes, concatenated). nod, nif, fix: location of removed sym genes. rhi: location of rhi genes. Triangles: location of sym gene fragments. Stars: location of mobile elements. Arrows mark the places of removed sym genes. Homologous regions are the same colour. White: unique regions. Coordinates of regions are in the correspondence with Figure S3.

3.3. Gain-and-Loss of Sym Genes

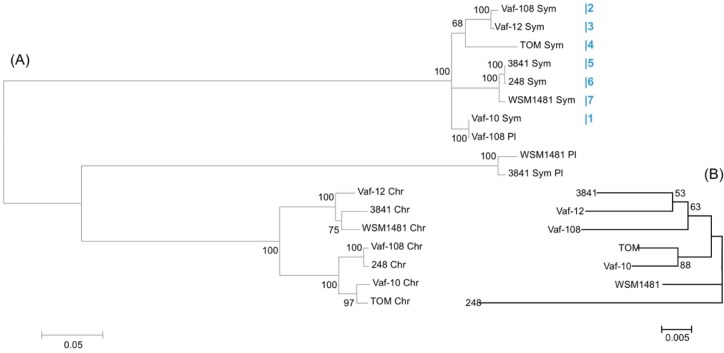

Gene gains, which may be due to the DD process, are represented by the multiple copies of the nodT gene used for the evolutionary reconstructions (Figure 4A). All seven analysed R. leguminosarum strains have two or three copies of nodT: one on a chromosome and the other(s) on plasmid(s). We found the extra chromosomal nodT copies in strains 3841 (on pSym), Vaf-10, and WSM1481 (on non-symbiotic plasmids). The mean p-distance within pSym-located nodT copies (excluding the third copies from 3841 and WSM1481) was 0.059, the mean p-distance within chromosomal nodT copies was 0.076, and the mean p-distance between these groups was 0.347. High bootstrap values (>80%) confirmed that Sym-plasmid copies of nodT are more similar to each other than to chromosomal copies, which suggests their deep evolutionary divergence.

Figure 4.

(A) Maximum likelihood tree of nodT copies from R. leguminosarum genomes. Chr, chromosomal copies; Sym, symbiotic copies; Pl, other plasmid copies of nodT. Blue figures are in the correspondence with numbered nodT copies from Figure 2. Values of bootstrap test exceeding 50 are shown next to the branches. (B) Neighbour joining tree for concatenation of core genes (16S rRNA, dnaK, glnA, and gsII). The evolutionary distances were computed using the maximum composite likelihood method, values of bootstrap test exceeding 50 are shown next to the branches [19].

Comparing vavilovia’s rhizobia genomes with reference genomes, we can “trace” a migration trajectory of the nodT gene into the nod cluster (Figure 2). In strain Vaf-10, nodT is completely separated from sym genes, and it is located on a separate plasmid. In Vaf-108, nodT is located in the same plasmid with other nod genes, but 30 kb apart from the closest gene (nodO). In Vaf-12, nodT is located a little bit closer (25 kb apart from nodO). In strain TOM, isolated from “Afghan” peas, nodT is significantly closer to other nod genes, just 10 kb apart. Finally, in strains 3841, WSM1481, and 248, isolated from the cultured peas and faba beans, nodT is a part of the nod cluster and is located between nodO and nodN. The comparison of phylogenies of nodT and house-keeping genes [19] demonstrates no correlation between them (Figure 4A,B). This applies both to symbiotic and chromosomal nodT copies.

Another example of a gene gain strategy is represented by the fixNOPQ operon encoding for a high-affinity terminal cytochrome oxidase of type cbb3. In vavilovia strains, single copies of these genes are revealed on pSyms, while in reference strains additional chromosomal copies were identified, which possibly originated via the DD mechanism. This difference may provide an extended adaptive potential of rhizobia for respiration under microaerophilic conditions, which rhizobia meet within the in planta and ex planta niches. It is important to note that the putative evolutionary predecessors of R. leguminosarum, probably Agrobacterium [8], do not have fix genes or their homologues. The latter finding suggests that chromosomal copies of fix genes represent the late acquisitions in the evolutionary history of the R. leguminosarum genome.

The gene losses in symbiotic clusters are illustrated by nodX and fixW, whose functions probably become non-sufficient during rhizobia microevolution. Specifically, nodX and fixW were identified in all three genomes of the vavilovia strains, whereas among the reference group these genes were detected only in strain TOM. Nucleotide BLAST at NCBI shows that fixW is found only in R. leguminosarum bv. viciae strains, while nodX can also be found in the majority of R. leguminosarum bv. trifolii strains. Since the split of R. leguminosarum into biovars viciae and trifolii occurred a long time ago, and the corresponding strains do not even form nodules upon cross-inoculation between the legumes from Trifolieae and Fabeae tribes, we can suggest that the presence of nodX (along with fixW) probably represents the ancestral features of the sym gene cluster in R. leguminosarum.

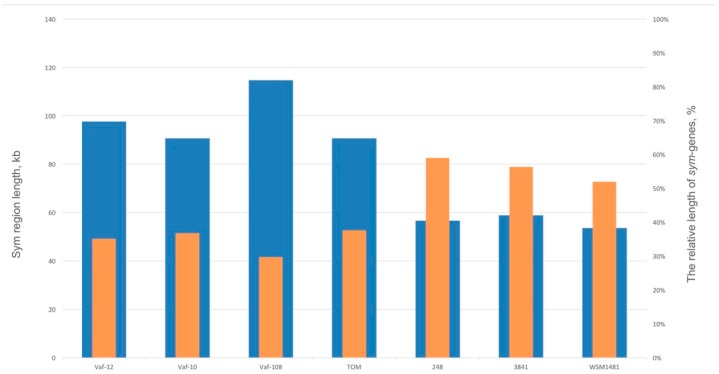

3.4. Compaction of the Sym Gene Cluster

Comparing the Vavilovia isolates with the reference group, we observed a significant Sym region size variation, ranging from more than 90 kb in the vavilovia strains and TOM to less than 60 kb in the reference group (Figure 5). This means that a putative transition from the vavilovia strains to the reference group is associated with the loss of up to half of the genetic material and sym cluster compaction, accordingly. As a result, the length of the sym cluster is gradually decreased from 114.7 kb (Vaf-108) to 53.8 kb (WSM1481). We expressed these differences in terms of the ratio of the summarised sym genes length to the total sym cluster length (Figure 5). The average share of “removed” regions in the genomes was up to 50%. The share of non-symbiotic genes is maximal in the genome of the Vaf-108 strain and is minimal in the 3841 genome. Therefore, as a result of sym region compaction, about 75% of non-sym genes may be removed.

Figure 5.

Sym region length and the relative length of sym genes in Sym regions. Blue, Sym region length; orange, the relative length of sym genes.

Functionally, these removed (and probably not essential for symbiosis) non-sym genes belong to several groups (Table 2). The most significant fraction is represented by genes controlling amino acid transport and metabolism (group E in the COG classification), transcription (group K), and mobile elements (group X). Localisation of the latter is shown in Figure 3.

Table 2.

Functional groups found in inter-sym-gene regions.

| COG Group | Function | Vaf-10 | Vaf-12 | Vaf-108 | 3841 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | Energy production and conversion | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 |

| E | Amino acid transport and metabolism | 8 | 14 | 14 | 0 |

| H | Coenzyme transport and metabolism | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| I | Lipid transport and metabolism | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| J | Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| K | Transcription | 1 | 6 | 5 | 1 |

| L | Replication, recombination and repair | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| M | Cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| O | Post-translational modification, protein turnover, and chaperones | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| P | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism | 4 | 3 | 2 | 0 |

| R | General function prediction only | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| S | Function unknown | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| T | Signal transduction mechanisms | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| V | Defense mechanisms | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| X | Mobile elements | 6 | 1 | 12 | 4 |

| Total | 31 | 41 | 48 | 9 |

We also searched for genes from E and K functional groups in the chromosomes of the vavilovia strains and of the 3841 strain. Tblastn showed that most of the genes have homologs in their own chromosomes, with about 80%–100% coverage and up to 40% identity, with an exception for rpoN, with 100% coverage and 95% identity.

The analysis of the genes that are retained in nearly all sym gene clusters, in spite of their compaction, was of special interest. They are represented by rhi genes, which are related to functional groups K (transcription, rhiR), M (cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis, rhiD), T (signal transduction mechanisms, rhiI), S (function unknown, rhiB), and other (rhiA, rhiC), and are retained in even the most compact versions of the Sym cluster (3841) and completely absent only in strain Vaf-10 (Table 3). rhi genes are expressed in the rhizosphere and are possibly involved in the pre-infection rhizobia–legume interactions [42], which are essential for nodulation competitiveness [43]. However, no symbiotic defects were previously revealed in the R. leguminosarum mutants for rhi genes [42]. These genes have homologs (over 90% identity) on the plasmids in most of the R. leguminosarum bv. viciae strains. These data suggest that the importance of rhi genes in symbiosis should be further clarified.

Table 3.

Functional groups found in inter-sym-gene regions. Empty cells mean the absence of such group.

| Group | Protein | Function | Sym plasmid | Chromosome | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaf-10 | Vaf-12 | Vaf-108 | 3841 | Vaf-10 | Vaf-12 | Vaf-108 | 3841 | ||||

| COG0136 | E | Asd | Aspartate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| COG0334 | E | GdhA | NADP-specific glutamate dehydrogenase | + | + | + | |||||

| COG0410 | E | LivF | ABC-type branched-chain amino acid transport systems, ATPase component | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| COG0411 | E | LivG | ABC-type branched-chain amino acid transport systems, ATPase component | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| COG0527 | E | LysC | Aspartokinase | + | + | + | |||||

| COG0559 | E | LivH | Branched-chain amino acid ABC-type transport system, permease components | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| COG0683 | E | LivK | ABC-type branched-chain amino acid transport systems, periplasmic component | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| COG0747 | E | OppA | ABC-type dipeptide transport system, periplasmic component | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| COG1982 | E | LdcC | arginine/lysine/ornithine decarboxylase | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| COG4177 | E | LivM | ABC-type branched-chain amino acid transport system, permease component | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| COG0601 | EP | DppB | ABC-type dipeptide/oligopeptide/nickel transport systems, permease components | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| COG1173 | EP | NikC | ABC-type dipeptide/oligopeptide/nickel transport systems, permease components | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| COG0583 | K | LysR | Transcriptional regulator, LysR family | + | + | + | + | + | |||

| COG1508 | K | RpoN | DNA-directed RNA polymerase specialized sigma subunit, sigma54 homolog | + | + | + | + | + | |||

| COG1522 | K | Lrp | putative AsnC family transcriptional regulatory protein | + | + | + | + | + | |||

| COG1737 | K | RpiR | Transcriptional regulator, nylB upstream ORF | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| COG4977 | K | AraC | Transcriptional regulator AraC family | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| COG1167 | KE | ARO8 | Transcriptional regulator, GntR family domain/Aspartate aminotransferase | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| COG2771 | K | RhiR | DNA-binding HTH domain-containing proteins | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| COG3637 | M | RhiD | Opacity protein and related surface antigens | + | + | ||||||

| COG3916 | T | RhiI | N-acyl-L-homoserine lactone synthetase | + | + | ||||||

| COG4675 | S | RhiB | Microcystin-dependent protein | + | + | + | |||||

| not in COG | RhiA | + | + | + | |||||||

| not in COG | RhiC | + | + | + | |||||||

Presence (+).

Summarised data on R. leguminosarum bv. viciae sym gene cluster organisation are given in Table 4.

Table 4.

Summary of genomic features studied.

| nodT-nodO Distance | nodT Location | nodX | fixW | Sym Region Length | fixNOQP Copies | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaf-10 | not linked | Separate | + | + | 93 kb | 1 |

| Vaf-108 | 30 kb | Separate | + | + | 115 kb | 1 |

| Vaf-12 | 25 kb | Separate | + | + | 98 kb | 1 |

| TOM | 10 kb | Separate | + | + | 91 kb | 3 |

| 3841 | < 1 kb | Between nodO and nodN | – | – | 59 kb | 3 |

| 248 | < 1 kb | Between nodO and nodN | – | – | 57 kb | 2 |

| WSM1481 | < 1 kb | Between nodO and nodN | – | – | 54 kb | 3 |

Presence (+) or absence (-) of nodX and fixW genes are shown.

3.5. Metatree Analysis

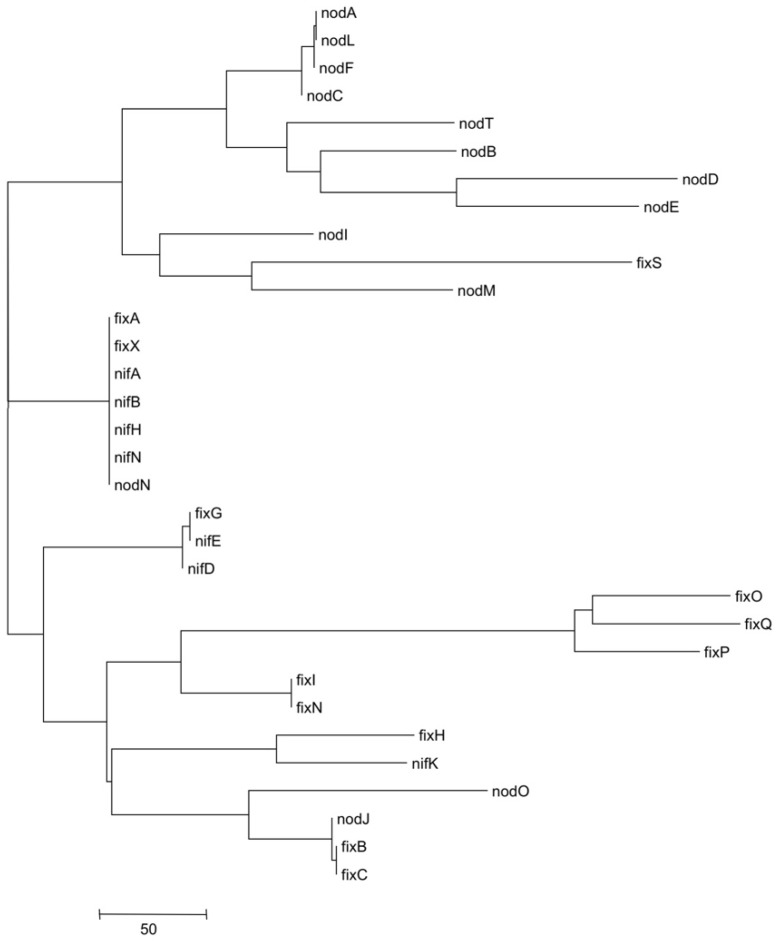

To compare the natural histories of different sym gene groups, we composed and analysed a metatree, which reflects the similarities in gene phylogenies. We made pairwise comparison of topologies of phylogenetic trees of sym genes, which are present in all seven R. leguminosarum strains, and constructed a metatree, which presumably shows the concordance of the HGT trajectory genes in particular clusters. Analysis of this metatree (Figure 6) suggests the clustering of genes located together in the plasmid are related to the same cluster, like most nod genes. Similarly, we observed the separated cluster of cbb3-encoding fixOQP genes. Other nif and fix genes were also grouped together, though this clustering was not uniform. We revealed some genes that fall into the “foreign metatree clusters”, such as fixS, nodO, and nodJ. Perhaps the same could be said about the fixN position, although its branch is very close to the fixOQP cluster. Remarkably, these genes from “foreign” clusters on metatree are located at the borders of their own clusters on pSyms, suggesting random capture of these genes via the recombination (HGT) events.

Figure 6.

Metatree of symbiotic genes.

Generally, the sym gene clustering observed on metatree probably reflects an independent combination of nod and nif/fix genes during the HGT-based symbiotic cluster assembly. It should be noted that this metatree approach could have methodological artefacts. On the other hand, the specific clustering observed in the metatree hardly could be accidental.

4. Discussion

This paper was aimed at analysing the microevolutionary variation of sym gene arrangement in R. leguminosarum bv. viciae, with a special emphasis on the strains isolated from the relict plant V. formosa, probably the closest living relative of the LCA of the legume tribe Fabeae, representing the hosts of this rhizobia species.

In a parallel publication, Kimeklis et al. [19] demonstrated that the Vavilovia isolates comprise a separate group within R. leguminosarum bv. viciae. Divergence of the rhizobia biovars is more pronounced for sym genes (nodA, nodC, nodD, and nifH) than for housekeeping genes (16S rRNA, glnII, gltA, and dnaK). This separation may be a result of vavilovia’s prolonged ecological isolation caused by its hard-to-reach habitat in the rocky highlands of the Caucasus and Middle East, which is known as the gene centre for P. sativum origin [44,45]. This is why we concentrated on the genomic arrangement of sym genes for dissecting the mechanisms of the rhizobia microevolution.

Nucleotide polymorphism analysis of individual chromosomal and symbiotic genes performed by Kimeklis et al. [19] in this paper is expanded with ANI actually representing the total genome polymorphism. These data clearly indicate that the vavilovia strains belong to the same group as other R. leguminosarum bv. viciae strains.

To summarise the presented data, we classified the analysed rhizobia strains into two genomic groups (Table 2). A presumable ancestral (A) group, which includes all three strains from V. formosa and strain TOM isolated from the primitive “Afghan” pea, was characterised by the scattered sym gene arrangement: extended Sym cluster (≥90 kb) and sometimes its separation between two Sym-plasmids, presence of nodX and fixW genes within the plasmid-borne sym gene clusters, absence of chromosomal copies of fixNOPQ, and location of nodT outside the other nod operons. In the derived (D) or evolutionary advanced group (the other three strains isolated from cultivated pea and faba bean), the Sym cluster is more compact (<60 kb), nodT is integrated into a nod cluster between nodN and nodO, and genes nodX and fixW are lost while the chromosomal copies of fixNOPQ are gained. Interestingly, the compaction trend can be also detected in the whole genome level: Genome sizes and the fraction of the dispensable genes is higher in the group of ancestral strains.

Importantly, the TOM strain occupies an “intermediate” position in this classification because its nodT gene is located close to other nod genes and the chromosomal fixNOPQ copy is present while the other features are similar to the vavilovia strains. In addition, the phylogenetic position of the TOM strain in nodA and nodD genes is intermediate between the Vavilovia and Pisum/Vicia isolates [19]. The intermediate position of TOM correlates with the phylogenetic status of “Afghan” peas, which represent the primitive forms of P. sativum, and probably were the precursors of cultured European varieties [19,46].

Since the Fabeae tribe is among the evolutionary young “galegoid” legume group [47], one can suggest that the major sym systems used in a hypothetical LCA of R. leguminosarum bv. viciae (represented tentatively by the vavilovia strains) were already formed. Therefore, the observed microevolutionary variation of sym gene arrangement within bv. viciae (difference between A and D groups) represents a “polishing” of the sym gene system for adaptation towards the specific “plant–soil” systems formed by the Fabeae legumes. A proposed transition from the A to D group is associated with the loss of ancestral features by rhizobia, which is probably correlated to intensive cultivation of legume hosts, which elicits evolutionary changes in favour of increased N2 fixation intensity.

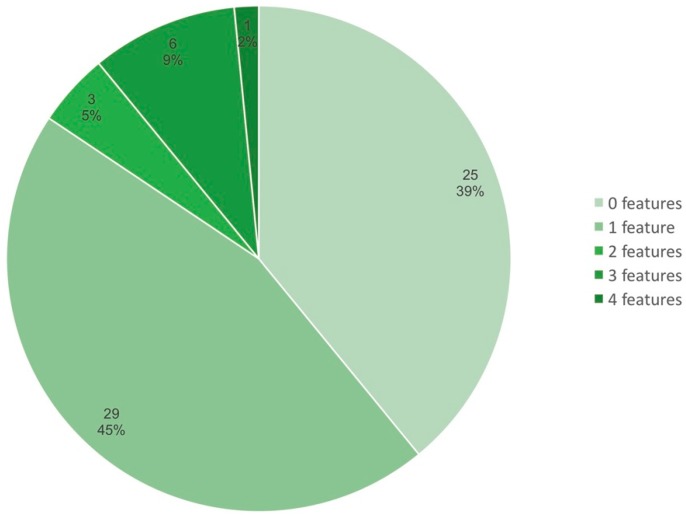

To understand how often the putative “ancestral” features may be detected in strains of R. leguminosarum bv. viciae isolated from different host plants and from different regions outside the Vavilovia growth area, we searched for these features in all 64 genomes of this species available in GenBank (mostly drafts), including previously analysed strains 3841, 248, TOM, and WSM1481, and summarised the findings (Figure 7). The five “ancestral” features included the following: The presence of nodX, the presence of fixW, separate location of nodT, a Sym cluster larger than 90 kb, and a lack of a second (chromosomal) copy of fixNOQP. The obtained results showed that putative ancestral features can be detected in the majority of strains, although in 80% of the genomes their amount does not exceed one feature. No strain from the analysed GenBank collection was found to have the full set of five putative “ancestral” features, which was found only in the Vavilovia isolates. The closest to the Vavilovia strain was TOM, isolated in Turkey from the primitive “Afghan” pea. In this strain, we detected four putative “ancestral” features, except for the absence of the fixNOQP chromosomal copy. These data show that as R. leguminosarum bv. viciae strains spread from the supposed centre of origin, they lost ancestral features due to adaptations to new host plants and soil conditions and with an increase in symbiotic efficiency.

Figure 7.

Frequencies (%) of R. leguminosarum bv. viciae strains possessing different numbers of putative ancestral genomic features (analysis of 64 genomes from GenBank data, including drafts; strains isolated from Vavilovia possessing all five ancestral features are not included). The “ancestral” features include the following: The presence of nodX, the presence of fixW, separate location or lack of nodT, a Sym cluster larger than 90 kb, and a lack of the chromosomal fixNOQP copy. Figures inside the sectors indicate the number of strains.

The presented analysis of intra-species variation of sym gene arrangement in R. leguminosarum bv. viciae suggests that its microevolution follows similar tendencies as the macroevolution of the Rhizobiales: “gain-and-loss of sym genes” and “sym gene cluster compaction”. We suggest that both tendencies are correlated with improved fitness of rhizobia in the “plant–soil” system.

For example, recruiting of nodT from the chromosome into pSym may result in a more effective NF efflux, providing an improved nodulation rate. The NodT protein belongs to the family of outer membrane proteins from the RND (resistance–nodulation–cell division) efflux system, which is involved in the diverse adaptive processes, including plant–microbe interactions [48]. Chromosomal copies of nodT are essential for bacteria viability outside the plants [49], but the use of a single nodT chromosomal copy for symbiotic purposes could not be effective enough. nodT demonstrates a DD-based evolutionary scenario, including duplication, neofunctionalization, and clustering into the nod regulon. We suppose that nodT was duplicated and recruited from the chromosome, migrated to the Sym plasmid, and finally inserted between nodO and nodN, forming a compact nod gene cluster. The absence of correlation between nodT and house-keeping gene phylogenies can be explained by the independence of evolutionary processes of symbiotic cluster formation.

The other example of the DD-based evolutionary scenario is represented by the duplication of fixNOQP into the chromosome revealed in the D group, which may result in improved adaptation to poorly aerated soil niches. fixNOQP genes and their homologues in Gram-negative non-N2-fixing bacteria ccoNOQP [50] encode for the high-affinity terminal cytochrome oxidase of the cbb3 type, which provides respiration under microaerophilic conditions [51]. Most likely, fixNOQP cluster duplication and its transfer to the chromosome occurs at the later stages of R. leguminosarum bv. viciae evolution [52], and it may reflect an adaptive process during the promotion of rhizobia to new microaerobic niches. This assumption is also supported by the absence of fixNOQP genes in Agrobacterium, which may represent a “chromosomal precursor” of R. leguminosarum [53].

The loss of fixW in the D group may be correlated to a deep differentiation of bacteroids typical from many legumes of the Fabeae tribe. The FixW protein belongs to the TlpA-like family, which possesses the thioredoxin function and serves for breaking the disulphide bonds between cysteine residues in Cu2+ binding sites of cytochrome c oxidase CoxB and in Cu2+ transfer chaperone ScoI [54]. The functions of fixW itself and its importance for symbiosis have not been studied in detail, although fixW unlikely affects the host range [55]. Perhaps, FixW can destroy the cysteine-rich bounds in the plant-born NCR (nodule-specific cysteine-rich) proteins involved in bacteroid differentiation, and loss of this gene can be correlated to improvement of this differentiation stimulated by NCR peptides [56]. Previously, Tsyganova et al. [57] demonstrated that in Vavilovia nodules, the bacteroids are poorly differentiated and often form multi-bacterial symbiosomes, while in P. sativum and other legumes from the Fabeae tribe, the highly differentiated singular bacteroids occur in symbiosomes.

The adaptive impact of nodX loss on rhizobia fitness is less clear. Previously, it was correlated to a narrowed specificity of R. leguminosarum bv. viciae towards the “Afghan” pea. However, Kimeklis et al. [19] did not confirm this specificity when analysing the interaction of the studied strains with nine different hosts; all R. leguminosarum strains obtained from Vavilovia have nodX in their genomes and form N2-fixing nodules both on Afghan and European pea lines in a tube test. Moreover, our preliminary data demonstrate that the majority of clover rhizobia (R. leguminosarum bv. trifolii) strains isolated from diverse geographic areas have this gene [58]. nodX encodes for an O-acetyltransferase protein that modifies the Nod factor, permitting rhizobia to form symbiosis both with the “Afghan” (carrying the specific Sym2A allele of the Nod-factor receptor) and European pea lines [59]. The loss of nodX in the European R. leguminosarum bv. viciae populations possibly reflects the narrowing of the rhizobia host range, which is within the mainstream of symbiosis evolution and presumably correlates to increased N2-fixing activity [60].

Previously, we suggested [61] that the adaptive impact of rhizobia–legume symbiosis is correlated not only with the intensity of N2 fixation but also with the rate of symbiosis evolution, providing the swift gain of novel adaptive valuable traits for both partners. Evolution of symbiotic traits in rhizobia is based on recombination events resulting from genomic rearrangements and from HGT, as indicated by the panmictic structures of rhizobia populations, yielding numerous polyphyletic rhizobia species (the Rhizobiales) sharing a range of “common” sym genes [62]. We demonstrated that in the A group, the sym cluster is less compact than in the D group, providing proof for an ancestral status of the vavilovia strains.

Interestingly, in addition to the full-size sym genes, 150–200 bp length fragments of these genes were identified in the inter-sym-gene regions. These small fragments are most likely the remnants of numerous “natural evolutionary experiments” involving different alleles of sym genes and HGT, during which multiple rearrangements of sym genes occurred. Alignment of these fragments with their full-size homologs showed a similarity of 85%–95%, indicating a random divergence of non-functional fragments that are not under the control of natural selection.

The natural histories of the sym genes may be reflected by the metatree (Figure 6), which demonstrates the separate clusterisation of nod and nif/fix gene topologies, reflecting an independent history of horizontal transfers of these groups of genes. We observe a clear metatree clustering of genes located together and related to the same (nodulation or N2 fixation) process. One can assume that the major groups of sym genes (nod, nif/fix) combined mostly independently, although genes that fall into “foreign” clusters revealed on the metatree may indicate their occasional capture during the HGT of the neighbouring cluster or kind of methodological artefacts [63].

An important role in HGT-based recombination was played by mobile elements. Their number in the A-group strains (e.g., Vaf-108) was almost four times more than in the D-group strains. Obviously, the evolutionary “polishing” of the symbiotic cluster induced its compaction due to the removal of genes that are not involved directly in symbiosis, e.g., encoding for the amino acid transport and metabolism, transcription, and mobile elements. However, rhi genes are retained in the majority of inter-sym-gene regions, which presumable play a role in the control of partners’ interactions [42]. Possibly in some “natural evolutionary experiments”, these genes were also removed (strain Vaf-10), but nevertheless, they were retained in the genomes of the advanced rhizobia (D group).

The revealed differentiation of A and D groups suggests that V. formosa being closely related to the LCA of the Fabeae tribe supports ancestral symbionts, which may be related to the LCA of R. leguminosarum bv. viciae. Interestingly, the A group is highly variable with respect to sym gene arrangement, suggesting that a relict host represents a reservoir of diversity for the relict symbionts. Our data suggest that radiation of ancestral R. leguminosarum bv. viciae strains from the putative centers of origin (area of Vavilovia growth) to the novel areas is correlated to the loss of ancestral genomic features (Figure 7). It may result in adaptation of the bacteria to novel hosts and soil environments possibly leading to an increased bacterial fitness in the “plant–soil” systems.

The pronounced genomic diversity of Vavilovia symbionts enables us to look for a parallel to Nikolai Vavilov’s [64] concept of the plant origins centers wherein the maximal crop diversity is concentrated. We can suggest that this concentration pertains not only to plants but also the associated microbial communities constituting the adaptively valuable plant–microbe hologenomes. The first report about isolation rhizobia from Vavilovia nodules [16] demonstrated a spectrum of microorganisms from Bosea, Tardiphaga, and Phyllobacterium genera. It was shown later that some rhizobia isolated from other relict legumes may harbor the incomplete sets of sym genes and can effectively infect their host only in the presence of other microsymbionts [65]. A similar type of complementation has been described firstly for different types of non-infective Sinorhizobium meliloti mutants [66]. These data suggest that the genetically diverse bacterial communities inhabiting the legume nodules may represent the reactors for intensive bacterial evolution, resulting in novel types of sym gene organization.

Acknowledgments

For the nodules supply, we thank A. Pukhaev (Gorsky State Agrarian University, Vladikavkaz, Russia) and A. Musaev (Mountain Botanical Garden, Makhachkala, Russia). Special acknowledgement is given to Alexander L’vovich Ivanov from the North-Caucasus Federal University for photographs of V. formosa in its natural habitat.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4425/10/12/990/s1, Figure S1: Neighbour joining tree for concatenation of core genes (16S rRNA, dnaK, glnA and gsII). The evolutionary distances were computed using the maximum composite likelihood method. Values of bootstrap tests (1000 replicates) exceeding 50 are shown next to the branches [19], Figure S2: ANI-distance clustering. (A) Whole genomes. (B) Chromosomes, Figure S3: The matrix with the presence and absence of core and accessory genes.in comparison with phylogram of ANI-distance clustering (Figure S1A), Figure S4: Schematic structure of R. leguminosarum Sym regions. Blue, nod genes; orange, nif genes; green, fix genes. Nucleotide positions are labeled with flags. Accession numbers of sequences are: Vaf-10, CP016287 (nodT), CP016290 (other sym genes); Vaf-108, CP018235 (nod genes), CP018229 (nif and fix genes); Vaf-12, KT944070; TOM, AQUC01000005; 3841, NC_008381; 248, ARRT01000005; WSM1481, AQUM01000002, Table S1: Average nucleotide identity of genomes of R. leguminosarum bv. viciae strains, Table S2: Average nucleotide identity of chromosomes of R. leguminosarum bv. viciae strains, Table S3: Core and accessory genome statistics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.E.A. and N.A.P.; methodology, E.E.A.; validation, E.R.C., E.E.A. and N.A.P.; formal analysis, E.R.C. and A.K.K.; investigation, E.R.C., A.K.K., V.V.K., E.S.K., T.S.A. and M.R.K.; resources, A.A.B. and V.I.S.; data curation, E.R.C. and A.K.K.; writing—original draft preparation, E.R.C.; writing—review and editing, E.E.A. and N.A.P.; visualization, E.R.C.; supervision, E.A.; project administration, E.E.A. and N.A.P.; funding acquisition, E.E.A. and N.A.P.

Funding

This research was funded by the Russian Science Foundation, grant numbers 16-16-00080 (maintenance and cultivation of strains), 19-16-00081 (sequencing and analysis) and 16-16-00080 (isolation of strains). The work was carried out using the equipment of the Genomic Technologies, Proteomics and Cell Biology Core Shared Facilities at ARRIAM and equipment of the SB RAS Genomics Core Facilities (ICBFM, SB RAS). Maintenance of isolates collection is carried out within the FASO Russia program on development and inventory of bioresource collections by scientific organizations.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- 1.Young J.P.W. Phylogeny and taxonomy of rhizobia. Plant Soil. 1996;186:45–52. doi: 10.1007/BF00035054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zakhia F., de Lajudie P. Taxonomy of rhizobia. Agronomie. 2001;21:569–576. doi: 10.1051/agro:2001146. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gottfert M. Regulation and function of rhizobial nodulation genes. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 1993;104:39–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1993.tb05863.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Debellé F., Moulin L., Mangin B., Dénarié J., Boivin C. Nod genes and Nod signals and the evolution of the Rhizobium legume symbiosis. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2001;48:359–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shamseldin A. The Role of Different Genes Involved in Symbiotic Nitrogen Fixation—Review. GJBB. 2013;8:84–94. doi: 10.5829/idosi.gjbb.2013.8.4.82103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fischer H.M. Genetic Regulation of Nitrogen Fixation in Rhizobia. Microbiol. Rev. 1994;58:352–386. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.3.352-386.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Provorov N.A., Andronov E.E. Evolution of root nodule bacteria: Reconstruction of the speciation processes resulting from genomic rearrangements in a symbiotic system. Microbiology. 2016;85:131–139. doi: 10.1134/S0026261716020156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rey F.E., Harwood C.S. FixK, a global regulator of microaerobic growth, controls photosynthesis in Rhodopseudomonas palustris. Mol. Microbiol. 2010;75:1007–1020. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.07037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wongdee J., Boonkerd N., Teaumroong N., Tittabutr P., Giraud E. Regulation of Nitrogen Fixation in Bradyrhizobium sp. Strain DOA9 Involves Two Distinct NifA Regulatory Proteins That Are Functionally Redundant During Symbiosis but Not During Free-Living Growth. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:1644. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hassan S., Mathesius U. The role of flavonoids in root-rhizosphere signalling: Opportunities and challenges for improving plant-microbe interactions. J. Exp. Bot. 2012;63:3429–3444. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Terpolilli J.J., Hood G.A., Poole P.S. What determines the efficiency of N(2)-fixing Rhizobium-legume symbioses? Adv. Microb. Physiol. 2012;60:325–389. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-398264-3.00005-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okazaki S., Noisangiam R., Okubo T., Kaneko T., Oshima K., Hattori M. Genome analysis of a novel Bradyrhizobium sp. DOA9 carrying a symbiotic plasmid. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0117392. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sullivan J.T., Trzebiatowski J.R., Cruickshank R.W., Gouzy J., Brown S.D., Elliot R.M. Comparative sequence analysis of the symbiosis island of Mesorhizobium loti strain R7A. J. Bacteriol. 2002;184:3086–3095. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.11.3086-3095.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poole P., Ramachandran V., Terpolilli J. Rhizobia: From saprophytes to endosymbionts. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018;16:291–303. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andrews M., Andrews M.E. Specificity in Legume-Rhizobia Symbioses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;18:705. doi: 10.3390/ijms18040705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Safronova V.I., Kimeklis A.K., Chizhevskaya E.P., Belimov A.A., Andronov E.E., Pinaev A.G., Pukhaev A.R., Popov K.P., Tikhonovich I.A. Genetic diversity of rhizobia isolated from nodules of the relic species Vavilovia formosa (Stev.) Fed. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 2014;105:389–399. doi: 10.1007/s10482-013-0089-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mikić A., Smýkal P., Kenicer G., Vishnyakova M., Sarukhanyan N., Akopian J.A., Vanyan A., Gabrielyan I., Smýkalová I., Sherbakova E., et al. Beauty will save the world, but will the world save beauty? The case of the highly endangered Vavilovia formosa (Stev.) Fed. Planta. 2014;240:1139–1146. doi: 10.1007/s00425-014-2136-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Govorov L.I. Peas. In: Vavilov N.I., Wulff E.V., editors. Flora of Cultivated Plants. Volume 4. Kolos; Leningrad, Russia: 1937. pp. 231–336. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kimeklis A.K., Chirak E.R., Kuznetsova I.G., Sazanova A.L., Safronova V.I., Belimov A.A., Onishchuk O.P., Kurchak O.N., Aksenova T.S., Pinaev A.G., et al. Rhizobia isolated from the relict legume Vavilovia formosa represent a genetically specific group within Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae. Genes. doi: 10.3390/genes10120991. under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kimeklis A.K., Safronova V.I., Kuznetsova I.G., Sazanova A.L., Belimov A.A., Pinaev A.G., Chizhevskaya E.P., Pukhaev A.R., Popov K.P., Andronov E.E., et al. Phylogenetic analysis of Rhizobium strains isolated from root nodules of Vavilovia formosa (Stev.) Fed. Sel’skokhozyaistvennaya Biol. [Agric. Biol.] 2015;50:655–664. doi: 10.15389/agrobiology.2015.5.655eng. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davis E.O., Evans I.J., Johnston A.W.B. Identification of nodX, a gene that allows Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar viciae strain TOM to nodulate Afghanistan peas. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1988;212:531–535. doi: 10.1007/BF00330860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kimeklis A.K., Kuznetsova I.G., Sazanova A.L., Safronova V.I., Belimov A.A., Onishchuk O.P., Kurchak O.N., Aksenova T.S., Pinaev A.G., Musaev A.M., et al. Divergent Evolution of Symbiotic Bacteria: Rhizobia of the Relic Legume Vavilovia formosa Form an Isolated Group within Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae. Russ. J. Genet. 2018;54:866–870. doi: 10.1134/S1022795418070062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Novikova N., Safronova V. Transconjugants of Agrobacterium radiobacter harbouring sym genes of Rhizobium galegae can form an effective symbiosis with Medicago sativa. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1992;93:261–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1992.tb05107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Somasegaran P., Hoben H.J. Handbook for Rhizobia: Methods in Legume-Rhizobium Technology. Springer; New York, NY, USA: 1994. Isolating and Purifying Genomic DNA of Rhizobia Using a Large-Scale Method; pp. 279–283. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Safronova V., Tikhonovich I. Automated cryobank of microorganisms: Unique possibilities for long-term authorized depositing of commercial microbial strains. In: Mendez-Vilas A., editor. Microbes in Applied Research: Current Advances and Challenges. World Scientific Publishing Co.; Singapore: 2012. pp. 331–334. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Russian Collection of Agricultural Microorganisms (RCAM) [(accessed on 1 October 2019)]; Available online: http://www.arriam.spb.ru/eng/lab10/

- 27.Bankevich A., Nurk S., Antipov D., Gurevich A., Dvorkin M., Kulikov A.S., Lesin V.M., Nikolenko S.I., Pham S., Prjibelski A.D., et al. SPAdes: A New Genome Assembly Algorithm and Its Applications to Single-Cell Sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 2012;19:455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gurevich A., Saveliev V., Vyahhi N., Tesler G. QUAST: Quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:1072–1075. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.HGAP: Hierarchical Genome Assembly Process. [(accessed on 30 May 2018)]; Available online: https://github.com/ben-lerch/HGAP-3.0.

- 30.Overbeek R., Olson R., Pusch G.D., Olsen G.J., Davis J.J., Disz T., Edwards R.A., Gerdes S., Parrello B., Shukla M., et al. The SEED and the Rapid Annotation of microbial genomes using Subsystems Technology (RAST) Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D206–D214. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu S., Zhu Z., Fu L., Niu B., Li W. WebMGA: A Customizable Web Server for Fast Metagenomic Sequence Analysis. BMC Genom. 2011;12:444. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chirak E.R., Kopat’ V.V., Kimeklis A.K., Safronova V.I., Belimov A.A., Chirak E.L., Tupikin A.E., Andronov E.E., Provorov N.A. Structural and Functional Organization of the Plasmid Regulons of Rhizobium leguminosarum Symbiotic Genes. Microbiology. 2016;85:708–716. doi: 10.1134/S0026261716060072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reeve W., Ardley J., Tian R., Eshragi L., Yoon J.W., Ngamwisetkun P., Seshadri R., Ivanova N.N., Kyrpides N.C. A Genomic Encyclopedia of the Root Nodule Bacteria: Assessing genetic diversity through a systematic biogeographic survey. Stand. Genomic. Sci. 2015;10:14. doi: 10.1186/1944-3277-10-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Young J.P.W., Crossman L.C., Johnston A.W.B., Thomson N.R., Ghazoui Z.F., Hull K.H., Wexler M., Curson A.R., Todd J.D., Poole P.S., et al. The genome of Rhizobium leguminosarum has recognizable core and accessory components. Genome Biol. 2006;7:R34. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-4-r34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tamura K., Stecher G., Peterson D., Filipski A., Kumar S. MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;30:2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nye T.M.W., Liò P., Gilks W.R. A novel algorithm and web-based tool for comparing two alternative phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:117–119. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rodriguez-R L.M., Konstantinidis K.T. The enveomics collection: A toolbox for specialized analyses of microbial genomes and metagenomes. PeerJ Prepr. 2016;4:e1900v1. doi: 10.7287/peerj.preprints.1900v1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Darling A.C.E., Mau B., Blattner F.R., Perna N.T. Mauve: Multiple alignment of conserved genomic sequence with rearrangements. Genome Res. 2004;14:1394–1403. doi: 10.1101/gr.2289704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Page A.J., Cummins C.A., Hunt M., Wong V.K., Reuter S., Holden M.T.G., Fookes M., Falush D., Keane J.A., Parkhill J. Roary: Rapid large-scale prokaryote pan genome analysis. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3691–3693. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.GNU Parallel 2018. [(accessed on 20 November 2019)]; Available online: https://zenodo.org/record/1146014#.XdULkxMzbVp.

- 41.Seemann T. Prokka: Rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2068–2069. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rodelas B., Lithgow J.K., Wisniewski-Dye F., Hardman A., Wilkinson A., Economou A., Williams P., Downie J.A. Analysis of quorum-sensing-dependent control of rhizosphere-expressed (rhi) genes in Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae. J. Bacteriol. 1999;181:3816–3823. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.12.3816-3823.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Onishchuk O.P., Vorobyov N.I., Provorov N.A. Nodulation competitiveness of nodule bacteria: Genetic control and adaptive significance: Review. Prikl. Biokhim. Mikrobiol. 2017;53:131–139. doi: 10.1134/S0003683817020132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vavilov N.I. Centers of origin of cultivated plants. Trends Pract. Bot. Genet. Sel. 1926;16:3–248. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhukovskii P.M. New origin and genetic centers of crops and highly endemic microcenters of related species. Bot. Z. 1968;53:430–460. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- 46.Makasheva R.H. Peas. Kolos; Leningrad, Russia: 1973. pp. 28–87. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sprent J.I., Ardley J., James E.K. Biogeography of nodulated legumes and their nitrogen-fixing symbionts. New Phytol. 2017;25:40–56. doi: 10.1111/nph.14474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alvarez-Ortega C., Olivares J., Martínez J.L. RND multidrug efflux pumps: What are they good for? Front. Microbiol. 2013;4:7. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hernández-Mendoza A., Nava N., Santana O., Abreu-Goodger C., Tovar A., Quinto C. Diminished Redundancy of Outer Membrane Factor Proteins in Rhizobiales: A nodT Homolog Is Essential for Free-Living Rhizobium etli. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007;13:22–34. doi: 10.1159/000103594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Myllykallio H., Liebl U. Dual role for cytochrome cbb3 oxidase in clinically relevant proteobacteria. Trends Microbiol. 2000;8:542–543. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(00)91831-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Talbi C., Sanchez C., Hidalgo-Garcia A., González E.M., Arrese-Igor C., Girard L., Bedmar E.J., Delgado M.J. Enhanced expression of Rhizobium etli cbb3 oxidase improves drought tolerance of common bean symbiotic nitrogen fixation. J. Exp. Bot. 2012;63:5035–5043. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ers101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kopat V.V., Chirak E.R., Kimeklis A.K., Safronova V.I., Belimov A.A., Kabilov M.R., Andronov E.E., Provorov N.A. Evolution of fixNOQP Genes Encoding Cytochrome Oxidase with High Affinity to Oxygen in Rhizobia and Related Bacteria. Russ. J. Genet. 2017;53:766–774. doi: 10.1134/S1022795417070067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Provorov N.A., Andronov E.E., Onishchuk O.P. Forms of natural selection controlling the genomic evolution in nodule bacteria. Russ. J. Genet. 2017;53:411–419. doi: 10.1134/S1022795417040123. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Abicht H.K., Schärer M.A., Quade N., Ledermann R., Mohorko E., Capitani G., Hennecke H., Glockshuber R. How Periplasmic Thioredoxin TlpA Reduces Bacterial Copper Chaperone ScoI and Cytochrome Oxidase Subunit II (CoxB) Prior to Metallation. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:32431–32444. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.607127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hontelez J.G., Lankhorst R.K., Katinakis P., van den Bos R.C., van Kammen A. Characterization and nucleotide sequence of a novel gene fixW upstream of the fixABC operon in Rhizobium leguminosarum. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1989;218:536–544. doi: 10.1007/BF00332421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang D., Griffitts J., Starker C., Fedorova E., Limpens E., Ivanov S., Bisseling T., Long S. A Nodule-Specific Protein Secretory Pathway Required for Nitrogen-Fixing Symbiosis. Science. 2010;327:1126–1129. doi: 10.1126/science.1184096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tsyganova A.V., Seliverstova E.V., Onischuk O.P., Kurchak O.N., Kimeklis A.K., Sazanova A.L., Kuznetsova I.G., Safronova V.I., Belimov A.A., Andronov E.E., et al. Diverse Ultrastructural Features of Symbiotic Nodules from Relict Legumes. 13th European Nitrogen Fixation Conference (ENFC) ENFC; Stockholm, Sweden: 2018. p. 204. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aksenova T.S., Onishchuk O.P., Kurchak O.N., Igolkina A.A., Andronov E.E., Provorov N.A. VII Congress of Vavilov Society of Genetics and Breeders on the 100th Anniversary of the Department of Genetics of Saint Petersburg State University, and Associate Symposia. Saint Petersburg. Saint Petersburg State University; Saint Petersburg, Russian: 2019. Positive selection in populations of nodule bacteria Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. Trifolii; p. 662. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ovtsyna A.O., Rademaker G.J., Esser E., Weinman J., Rolfe B.G., Tikhonovich I.A., Lugtenberg B.J., Thomas-Oates J.E., Spaink H.P. Comparison of characteristics of the nodX genes from various Rhizobium leguminosarum strains. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 1999;12:252–258. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.1999.12.3.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Provorov N.A., Tikhonovich I.A. Genetic resources for improving nitrogen fixation in legume-rhizobia symbiosis. Genet. Res. Crop Evol. 2003;50:89–99. doi: 10.1023/A:1022957429160. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Provorov N.A., Vorobyov N.I. Evolutionary Genetics of Plant-Microbe Symbioses (Agronomy Research and Developments) Nova Science Pub Inc.; New York, NY, USA: 2010. pp. 1–290. [Google Scholar]

- 62.del Carmen Orozco-Mosqueda M., Altamirano-Hernandez J., Farias-Rodriguez R., Valencia-Cantero E., Santoyo G. Homologous recombination and dynamics of rhizobial genomes. Res. Microbiol. 2009;160:733–741. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2009.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Karasev E.S., Chizhevskaya E.P., Simarov B.V., Provorov N.A., Andronov E.E. Comparative phylogenetic analysis of symbiotic genes of different nodule bacteria groups using the metatrees method. Agric. Biol. 2017;52:995–1003. doi: 10.15389/agrobiology.2017.5.995eng. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vavilov N.I. The origin, variation, immunity and breeding of cultivated plants. Chron. Bot. 1951;13:1–364. doi: 10.1097/00010694-195112000-00018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Safronova V.I., Belimov A.A., Sazanova A.L., Chirak E.R., Verkhozina A.V., Kuznetsova I.G., Andronov E.E., Puhalsky J.V., Tikhonovich I.A. Taxonomically Different Co-Microsymbionts of a Relict Legume, Oxytropis popoviana, Have Complementary Sets of Symbiotic Genes and Together Increase the Efficiency of Plant Nodulation. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2018;31:833–841. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-01-18-0011-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kapp D., Niehaus K., Quandt J., Muller P., Puhler A. Cooperative Action of Rhizobium meliloti Nodulation and Infection Mutants during the Process of Forming Mixed Infected Alfalfa Nodules. Plant Cell. 1990;2:139–151. doi: 10.2307/3868926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.