Abstract

From December 2006 to December 2016, 1093 human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) individuals < 70 years enrolled in Korea human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) cohort were analyzed to investigate the prevalence of HIV/HBV co-infection rate and hepatitis B virus surface antibody (HBsAb) positive rate based on birth year. The HBV co-infection prevalence rate was the highest (8.8%) in patients born between 1960 and 1964 and the lowest (0%) among those born between 1995 and 1999. A decreasing linear trend of HBV co-infection rate was observed according to the 5-year interval changes. HBsAb-positive rate was only 58.1% in our study. The national HBV vaccination programs have effectively lowered the HBV co-infection rate in HIV population. However, it is identified that the HIV population has low HBsAb positive rate. Further evidences supporting efficacy of booster immunization for HBsAb negative HIV patients are required and efforts should be made to increase HBsAb positive rates among HIV patients to prevent horizontal transmission.

Keywords: Hepatitis B Virus, HIV Infection, Co-Infection, Vaccination, National Cohort

Graphical Abstract

Approximately 10% of the population infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) has concurrent chronic hepatitis B, with co-infection rates more common in areas of high prevalence for both viruses.1,2 Korea was classified as a high hepatitis B virus (HBV) endemic area before implementing universal vaccination; in the 1980s, around 11% of neonates in Korea were infected with HBV through vertical transmission.3 Efforts to maintain the HBV vaccination rate above 95% has resulted in the average prevalence rate of hepatitis B decreasing to 3% since 2010. The hepatitis B virus surface antigen (HBsAg) positive rates of younger age groups markedly declined to 0.3% in 2016.4 However, there has been no further decline ever since and hepatitis B continues to remain a high prevalence disease in Korea. The fact that hepatitis B is still identified with low probability does not preclude the possibility of a horizontal transmission. While the prevalence rate of hepatitis B is an estimated 5%, as per the Korea HIV/AIDS (acquired immune deficiency syndrome) cohort in 2017,5 seroprevalence of HBV among HIV patients has been rarely reported in Korea after introduction of HBV vaccination as supplementary immunization activity in 1985 and the national vaccination program (NIP) for newborns in 1995.6 Therefore, we aimed to evaluate the HBsAg, HBsAb status and the effect of HBV vaccination programs in HIV patients.

The Korea HIV/AIDS cohort is a multicenter, prospective study consisting of 15 university hospitals nationwide and funded by the Korean Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC). This cohort has an ongoing enrollment of HIV-infected adult patients older than 18 years. We analyzed HIV individuals enrolled between December 2006 and December 2016. To evaluate the prevalence of HBV co-infection rate and HBsAb status among HIV-infected persons, we investigated the presence of HBsAg and HBsAb based on the year of birth.

According to the HIV/AIDS management guidelines of KCDC, HIV infection was screened for using enzyme immunoassays (EIA) and confirmed with western blotting. HBV infection was defined based on HBsAg positivity with or without protective antibodies. HBsAb positivity was confirmed by a positive enzyme linked immunosorbent assay test. The seropositivity of HBsAg was determined by cut-off index of HBsAg > 1.0 and HBsAb > 10 mIU/mL.

The statistical analyses are performed with descriptive statistics and linear regression. The statistical analyses were performed using R statistics ver. 3.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

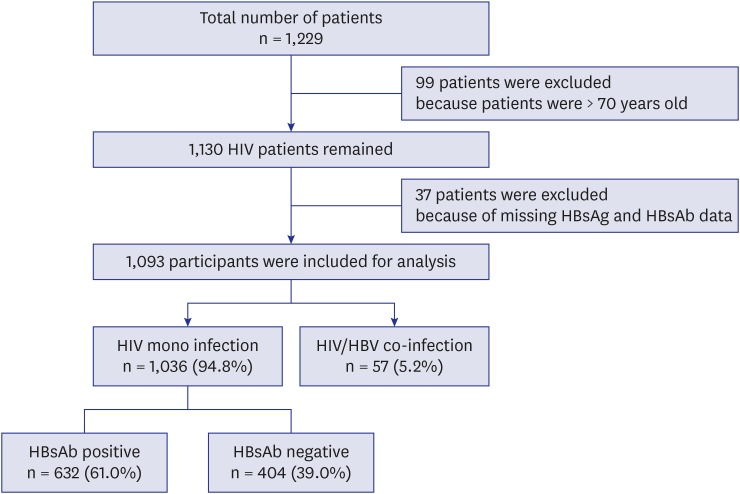

A total of 1,093 individuals (mean age, 47 years; interquartile range [IQR], 39–56) were included for analysis (Fig. 1). Most participating patients were men (1,028/1,093; 94.15%) and Korean ethnicity (1,079/1,093; 98.7%). The main route of transmission was sexual contact accounting for 1058 (96.8%) patients. Further, 127 (11.6%) patients experienced disease transmission from foreign countries (Table 1).

Fig. 1. Profile of enrolled patients.

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus, HBV = hepatitis B virus, HBsAb = hepatitis B virus surface antibody.

Table 1. Patients' baseline characteristics according to birth year.

| Variables | Birth year | Total (n = 1,093) | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before 1985 (n = 935) | 1985–1995 (n = 151) | After 1995 (n = 7) | ||||

| Gender | 0.140 | |||||

| Women | 61 (6.5) | 4 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | 65 (5.9) | ||

| Men | 874 (93.5) | 147 (97.4) | 7 (100.0) | 1,028 (94.1) | ||

| Age, yr | 50.0 (43.0–57.0) | 30.0 (29.0–32.0) | 24.0 (23.0–24.0) | 47.0 (39.0–56.0) | < 0.001 | |

| Ethnicity | 0.009 | |||||

| Korean | 924 (98.8) | 149 (98.7) | 6 (85.7) | 1,079 (98.7) | ||

| Othersa | 11 (1.2) | 2 (1.3) | 1 (14.3) | 14 (1.3) | ||

| Transmission route of HIV | 0.723 | |||||

| Sexual contact | 905 (96.8) | 146 (96.7) | 7 (100.0) | 1,058 (96.8) | ||

| Others | 3b (0.3) | 2c (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (0.5) | ||

| Reception of blood/product | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.2) | ||

| Unknown | 25 (2.7) | 3 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 28 (2.6) | ||

| Transmitted area | 0.107 | |||||

| In Korea | 605 (64.7) | 95 (62.9) | 6 (85.7) | 706 (64.6) | ||

| Foreign country | 115 (12.3) | 11 (7.3) | 1 (14.3) | 127 (11.6) | ||

| Unknown | 215 (23.0) | 45 (29.8) | 0 (0.0) | 260 (23.8) | ||

| Fatty liver | 0.528 | |||||

| Yes | 18 (1.9) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 19 (1.7) | ||

| No | 872 (93.3) | 146 (96.7) | 7 (100.0) | 1,025 (93.8) | ||

| Unknown | 45 (4.8) | 4 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | 49 (4.5) | ||

| Liver cirrhosis | 0.539 | |||||

| Yes | 7 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (0.6) | ||

| No | 882 (94.3) | 147 (97.4) | 7 (100.0) | 1,036 (94.8) | ||

| Unknown | 46 (4.9) | 4 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | 50 (4.6) | ||

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 0.416 | |||||

| No | 890 (95.2) | 147 (97.4) | 7 (100.0) | 1,044 (95.5) | ||

| Unknown | 45 (4.8) | 4 (2.60) | 0 (0.0) | 49 (4.5) | ||

| Hepatitis B vaccination history | 0.033 | |||||

| Yes | 283 (30.3) | 63 (41.7) | 3 (42.9) | 349 (31.9) | ||

| No | 389 (41.6) | 53 (35.1) | 4 (57.1) | 446 (40.8) | ||

| Unknown | 263 (28.1) | 35 (23.2) | 0 (0.0) | 298 (27.3) | ||

| HBsAg | 0.125 | |||||

| Positive | 54 (5.8) | 3 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 57 (5.2) | ||

| Negative | 881 (94.2) | 148 (98.0) | 7 (100.0) | 1,036 (94.8) | ||

| HBsAb | 0.161 | |||||

| Positive | 539 (57.6) | 94 (62.3) | 2 (28.6) | 635 (58.1) | ||

| Negative | 396 (42.4) | 57 (37.7) | 5 (71.4) | 458 (41.9) | ||

| HCV | 0.905 | |||||

| Positive | 21 (2.2) | 3 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 24 (2.2) | ||

| Negative | 914 (97.8) | 148 (98.0) | 7 (100.0) | 1,069 (97.8) | ||

Values are presented as medians (interquartile range) or number (%).

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus, HBsAg = hepatitis B virus surface antibody, HCV = hepatitis C virus.

aOthers denote non-Korean Asian patients; b1 acupuncture, 1 needle stick injury, 1 intravenous drug injection; c1 tattoo, 1 intravenous drug injection.

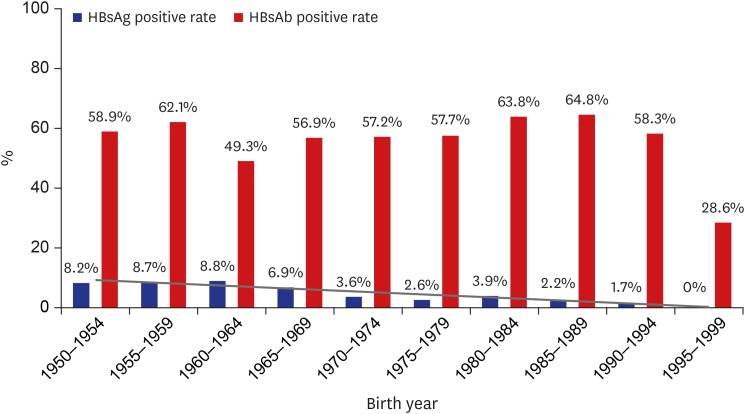

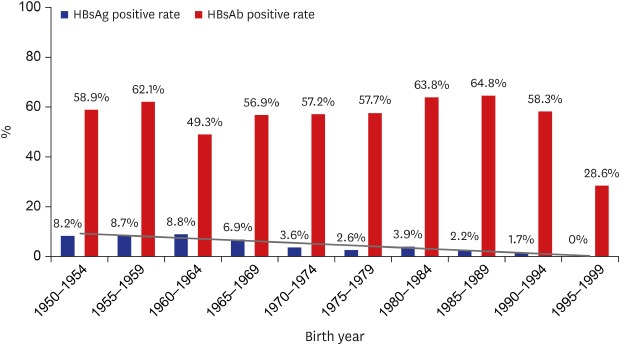

The HIV/HBV co-infection rate was identified in 5.2% (57/1,093) and HBV/HCV/HIV co-infection was only found in one patient born between 1960 and 1964. The HIV/HBV co-infection incidence was highest (8.8%; 12/174) among patients in the birth years between 1960 and 1964 and lowest (0%; 0/7) among those born between 1995 and 1999. A decreasing linear trend was observed with 5-year intervals (Fig. 2). Before year 1985, the proportion of HBsAg positivity was 54 (5.8%), but after 1985, between 1985 and 1995, the HBsAg positivity reduced to 3 (2.0%), and no hepatitis B co-infection was identified since 1995.

Fig. 2. Decreasing human immunodeficiency virus/hepatitis B virus co-infection incidence rate according to the birth year in 5-year intervals.

HBsAg = hepatitis B virus surface antigen, HBsAb = hepatitis B virus surface antibody.

The HBsAb positive rate was 58.1% (635/1,093) in the total HIV population (Table 1). The HBsAb positive rate was highest 64.8% (59/91) among patients born between 1985 and 1989. However, HBsAb positive rate was the lowest 28.6% (2/7) among patients born between 1995 and 1999 despite the rate of hepatitis B vaccination history being 42.9% (3/7) (Fig. 2).

The HBsAb positive rate was found in 198 (56.7%) out of a total of 349 patients with HBV vaccination history. Furthermore, the HBsAb positive rate ranged from 33.3% to 66.7% in patients born between 1950 and 1999. HBsAg was found to be positive in four patients born before 1985 (1.1%) out of 349 who said they had a history of vaccination.

Next, HBsAb positivity confirmed in 635 patients were analyzed, and 198 (31.2%) of these patients had an HBV vaccination history. Of the remaining patients, 185 (29.1%) could not remember their HBV vaccination history and 252 (39.7%) stated that they had never been vaccinated. The result did not differ from the results of the whole cohort, regardless of the patients' memory and status of HBsAb.

After introduction of hepatitis B vaccination, a significant decline in the prevalence of HBsAg positivity among HIV-positive patients was observed in our study. This result was similar to Taiwan HIV study which showed declined prevalence of HBsAg positivity from 16% to 4% after introduction of universal HBV vaccination in 1986.7 However, Korea still has a higher HBV prevalence rate than some other countries. Until now, the estimated prevalence was approximately 3% in 2016.4 The prevalence of HIV-HBV co-infection was 5.2% in our study, which showed a higher prevalence of HBV infection in HIV patients than in the general population. This is consistent with other previous studies.5,8,9 This may be caused by similarities in routes of transmission and risk factors between HBV and HIV,10,11,12 or lower incidences of spontaneous loss of HBsAg because of HIV-induced impairment of host innate and adaptive immunity.13 Given that most HIV infections in Korea are caused by sexual contact (96.8%) and that the vaccination rate for hepatitis B in Korean children is high, it is estimated that the chance of infection through sexual contact has increased, while the chance of infection by vertical infection has decreased.14 Currently, more than 1,000 new HIV infected patients are identified in Korea every year. HBV transmission may still occur in unvaccinated or uninfected adults and can lead to chronicity. A retrospective study conducted in a west China hospital showed that the prevalence of HIV/HBV co-infection was 14.4% among 894 HIV-infected patients. A high prevalence of HIV/HBV co-infection was observed and the rate for HIV-infected patients who were effectively vaccinated against HBV was fewer than 10%.15 Hepatitis B vaccination is consider with priority for people living with HIV.

However, despite the NIPs, adult HBsAb positive rate was reported to be 70.2% in Korean general population.16 Our study identified that the HIV population has lower HBsAb positive rates compared with general population. The HBsAb positive rate was only 56.7% among those known to have been vaccinated against HBV. It is assumed that there are more possibilities for transmission and infection by hepatitis B in the HIV population.

In our study, HBsAb positive rate of young HIV patients under 30 years old was identified 55.2% (37/67). A previous study conducted in Korea showed that HBsAb did not persist as protective titer despite complete HBV vaccination.6 The efficacy of vaccines may have a waning effect in Korea not only in general population but also in HIV patients. This would be a serious cause for concern among young HIV patients. A study conducted in Hong Kong indicated that decreased HBsAg carriage could be associated simultaneously with decreased seroprotection; thus, the former neonatal vaccination should not be considered as evidence of adequate seroprotection.17 Several studies showed that the HBsAb titer below the protective level after HBV vaccination could have protective effect against HBV infection because of anamnestic effect of HBsAb. However, it was not verified in HIV patients so called hyporesponders, eliciting the necessity of booster vaccination after adulthood.18,19 Vaccine-induced immunity should not be taken for granted from the period of adolescence onwards especially in HIV patients. Appropriate immunization of hepatitis B may be needed to prevent new HBV infections.20

For HIV patients, the effect of vaccination may differ according to immunity. Factors associated with impaired HBV vaccine response include older age, uncontrolled HIV replication, and low nadir CD4+ cell counts.21 We believe that appropriate vaccination policies are needed especially in HIV patients with these characteristics. National health plans should provide specific planning for HIV patients.

Our study has some limitations. First, because of the unfilled and missing data, we could not identify patients who have recovered from past HBV infections. Second, we could not distinguish between patients being infected with HBV prior to HIV infection, and whether they were infected by horizontal transmission sharing a same path with HIV. Third, since 1995, only seven patients were identified with HIV/HBV co-infection. This very small number of patients could have introduced a bias in our results.

In conclusion, our findings showed that the national HBV vaccination programs were effective in decreasing the HBV co-infection rate in HIV population. However, the HIV-HBV co-infection rate is still high and the HBsAb positive rate is low in Korea. Further evidences supporting efficacy of booster immunization for HBsAb negative HIV patients are required and as hepatitis B vaccine does not always provide life-long protection, efforts should be made to increase HBsAb positive rates among HIV patients to prevent horizontal transmission.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Kyungpook National University College of Medicine (approval No. 2011-01-048). All participants provided written informed consent, and ethics approval was obtained from the IRB of each participating institute.

Footnotes

Funding: This study was supported by a grant for research on deriving the major clinical and epidemiological indicators of HIV infected people (Korea HIV/AIDS Cohort Study) from the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (4800-4859-304, 2016-E51003-02, 2019-ER5101-00).

Disclosure: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

- Conceptualization: Kim YJ, Kim SW.

- Data curation: Kim YJ, Kim SW.

- Investigation: Kim SW, Jun YH, Sohn JW, Park DW, Song JY, Choi JY, Kim HY, Kim JM, Choi BY, Choi YS, Kee MK, Yoo MS, Lee JG.

- Supervision: Kim SW.

- Writing - original draft: Kim YJ, Kim SW.

- Writing - review & editing: Kwon K, Chang HH, Kim SW.

References

- 1.Phung BC, Sogni P, Launay O. Hepatitis B and human immunodeficiency virus co-infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(46):17360–17367. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i46.17360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thio CL. Hepatitis B and human immunodeficiency virus coinfection. Hepatology. 2009;49(5) Suppl:S138–S145. doi: 10.1002/hep.22883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park NH, Chung YH, Lee HS. Impacts of vaccination on hepatitis B viral infections in Korea over a 25-year period. Intervirology. 2010;53(1):20–28. doi: 10.1159/000252780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yim SY, Kim JH. The epidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection in Korea. Korean J Intern Med. 2019;34(5):945–953. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2019.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim YC, Ahn JY, Kim JM, Kim YJ, Park DW, Yoon YK, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis virus coinfection among HIV-infected Korean patients: the Korea HIV/AIDS cohort study. Infect Chemother. 2017;49(4):268–274. doi: 10.3947/ic.2017.49.4.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim YJ, Li P, Hong JM, Ryu KH, Nam E, Chang MS. A single center analysis of the positivity of hepatitis B antibody after neonatal vaccination program in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2017;32(5):810–816. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2017.32.5.810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang YC, Hsieh SM, Sheng WH, Huang YS, Lin KY, Chen GJ, et al. Serological responses to revaccination against HBV in HIV-positive patients born in the era of nationwide neonatal HBV vaccination. Liver Int. 2018;38(11):1920–1929. doi: 10.1111/liv.13721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adekunle AE, Oladimeji AA, Temi AP, Adeseye AI, Akinyeye OA, Taiwo RH. Baseline CD4+ T lymphocyte cell counts, hepatitis B and C viruses seropositivity in adults with human immunodeficiency virus infection at a tertiary hospital in Nigeria. Pan Afr Med J. 2011;9:6. doi: 10.4314/pamj.v9i1.71178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim JH, Psevdos G, Jr, Sharp V. Five-year review of HIV-hepatitis B virus (HBV) co-infected patients in a New York City AIDS center. J Korean Med Sci. 2012;27(7):830–833. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2012.27.7.830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rendina D, Mossetti G, De Filippo G. Viral hepatitis in HIV infection. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(1):90–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kellerman SE, Hanson DL, McNaghten AD, Fleming PL. Prevalence of chronic hepatitis B and incidence of acute hepatitis B infection in human immunodeficiency virus-infected subjects. J Infect Dis. 2003;188(4):571–577. doi: 10.1086/377135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun HY, Cheng CY, Lee NY, Yang CJ, Liang SH, Tsai MS, et al. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B virus among adults at high risk for HIV transmission two decades after implementation of nationwide hepatitis B virus vaccination program in Taiwan. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e90194. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Puoti M, Torti C, Bruno R, Filice G, Carosi G. Natural history of chronic hepatitis B in co-infected patients. J Hepatol. 2006;44(1) Suppl:S65–S70. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee HH, Hong HG, Son JS, Kwon SM, Lim BG, Lee KB, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis B virus and HIV co-infection in Korea. J Bacteriol Virol. 2016;46(4):283–287. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang T, Chen Q, Li D, Wang T, Gou Y, Wei B, et al. High prevalence of syphilis, HBV, and HCV co-infection, and low rate of effective vaccination against hepatitis B in HIV-infected patients in West China hospital. J Med Virol. 2018;90(1):101–108. doi: 10.1002/jmv.24912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee BS, Cho YK, Jeong SH, Lee JH, Lee D, Park NH, et al. Nationwide seroepidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection in South Korea in 2009 emphasizes the coexistence of HBsAg and anti-HBs. J Med Virol. 2013;85(8):1327–1333. doi: 10.1002/jmv.23594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lao TT. Immune persistence after hepatitis B vaccination in infancy - Fact or fancy? Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12(5):1172–1176. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2015.1130195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Su TH, Chen PJ. Emerging hepatitis B virus infection in vaccinated populations: a rising concern? Emerg Microbes Infect. 2012;1(9):e27. doi: 10.1038/emi.2012.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neukam K, Gutiérrez-Valencia A, Llaves-Flores S, Espinosa N, Viciana P, López-Cortés LF. Response to a reinforced hepatitis B vaccination scheme in HIV-infected patients under real-life conditions. Vaccine. 2019;37(20):2758–2763. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cho EJ, Kim SE, Suk KT, An J, Jeong SW, Chung WJ, et al. Current status and strategies for hepatitis B control in Korea. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2017;23(3):205–211. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2017.0104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim HN, Harrington RD, Crane HM, Dhanireddy S, Dellit TH, Spach DH. Hepatitis B vaccination in HIV-infected adults: current evidence, recommendations and practical considerations. Int J STD AIDS. 2009;20(9):595–600. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2009.009126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]