Abstract

Background:

Growing evidence points to the role of vitamin D in the pathobiology and treatment of depression. However, the evidence is inconsistent in many aspects. The objectives of this narrative review were to evaluate the state of the evidence, synthesize the knowledge gaps, and formulate recommendations for more enhanced research in this growing area.

Methods:

Electronic searches of MEDLINE via PubMed, Cochrane Library, and Google Scholar databases were carried out from inception till February 2019 to identify relevant English language peer-reviewed articles. Abstracts generated were systematically screened for eligibility. Included articles were grouped under three broad themes: The association between vitamin D and depression, its biological underpinnings, and trials evaluating the efficacy of vitamin D supplementation in depression. Relevant data were extracted as per a structured proforma.

Results:

A total of 61 articles were included in the present review. Overall findings were that there is a relationship between vitamin D and depression, though the directionality of this association remains unclear. The association appears to be driven by the homeostatic, trophic, and immunomodulatory effects of vitamin D. Evidence from supplementation trials suggest a more robust therapeutic effect on subjects with major depression and concurrent vitamin D deficiency.

Conclusion:

Serum vitamin D levels inversely correlate with clinical depression, but the evidence is not strong enough to recommend universal supplementation in depression. Enriching depression treatment trials with subjects having concurrent vitamin D deficiency appears to be a potential step forward in identifying subgroups who may maximally benefit from this approach.

Keywords: Depression, immune system, inflammation, psychiatry, vitamin D

Depression is a common and disabling mental illness, prevalent worldwide across all ages, genders, and races. In 2015, 4.4 per cent of the world's population was suffering from depression.[1] The condition is associated with increased morbidity and mortality, owing to increased risk for stroke, cardiovascular events, and suicide as well as lifestyle-related disorders such as diabetes and hypertension.[2,3,4] It also has significant economic and social consequences, such as decreased productivity and increased health care utilization costs.[5,6] Compounding the issue further, depression is associated with a high burden of nonresponse to conventional treatment options.[7,8]

Given the above scenario, clinicians and researchers are constantly looking to expand the therapeutic options to tackle depression. The last quarter of a century has seen research attention being increasingly centred on inflammation as a possible pathophysiological mechanism in depression. Several trials of anti-inflammatory agents have shown promise, but the evidence, so far, is not strong enough to guide clinical recommendations.[9,10]

Parallel to these developments, the role of vitamin D in depression has also received increasing research focus. Currently, there are at least three lines of evidence to support this association: first, an increased region-specific expression of vitamin D receptors (VDRs) in brain areas (such as prefrontal and cingulate cortices) known to play a key role in mood regulation;[11] second, the modulatory role proposed for vitamin D in the association between depression and inflammation (through a possible immune-modulatory mechanism)[12,13]; last, the emerging insights about the neuroprotective properties of vitamin D (by virtue of its anti-inflammatory effects).[14,15]

Against this background, we carried out the present narrative review to summarize the literature and clarify the evidence in three areas: association between vitamin D and depression, its underlying biological links, and therapeutic effects of vitamin D on depression. Accordingly, we had our objectives: - 1) to describe the evidence for association between vitamin D and depression and outline the underlying biological mechanisms, 2) to synthesize the evidence base for effect of vitamin D supplementation in depression, and 3) to highlight the knowledge gaps in these areas and formulate recommendations that seem most relevant for future research.

METHODS

Search strategy

We carried out an electronic search of MEDLINE through PubMed, Cochrane Library and Google Scholar databases (all up to February 2019) for articles on vitamin D and depression. For PubMed search, the following MeSH or free text terms were used: ‘vitamin D’, ‘vitamin d’, ‘25-hydroxyvitamin d 2’, ‘25-hydroxyvitamin d 3’, ‘calcifediol’, ‘depression’ or ‘depressive symptoms’ along with the Boolean operators AND and OR in a sequential MeSH and all fields search, as follows: ((((’vitamin d’[MeSH Terms] OR ‘ergocalciferols’[MeSH Terms]) OR (’vitamin d’[MeSH Terms] OR ‘vitamin d’[All Fields] OR ‘ergocalciferols’[MeSH Terms] OR ‘ergocalciferols’[All Fields])) OR (’25-hydroxyvitamin d 2’[MeSH Terms] OR (’25-hydroxyvitamin d 2’[MeSH Terms] OR ‘25-hydroxyvitamin d 2’[All Fields] OR ‘25 hydroxyvitamin d 2’[All Fields]))) OR (’calcifediol’[MeSH Terms] OR (’calcifediol’[MeSH Terms] OR ‘calcifediol’[All Fields] OR ‘25 hydroxyvitamin d 3’[All Fields]))) AND ((’depressive disorder’[MeSH Terms] OR ‘depression’[MeSH Terms]) OR (’depressive disorder’[MeSH Terms] OR (’depressive’[All Fields] AND ‘disorder’[All Fields]) OR ‘depressive disorder’[All Fields] OR ‘depression’[All Fields] OR ‘depression’[MeSH Terms])).

Search terms were adapted to suit the search needs of other databases as appropriate. Additionally, hand searches of the reference lists of the generated articles were done in order to ensure a comprehensive search. The searches were done by three independent reviewers, all of whom were qualified psychiatrists.

Study selection and data extraction

The initial search yielded 879 hits. We included only English language articles published in peer-reviewed journals. Editorials and commentaries were not included in the main review but only to support some recommendations, we make at the end. We also included systematic reviews and meta-analyses addressing focused research questions related to the focus areas, and the original articles included in these reviews were not examined separately. Based on these criteria and after eliminating duplicates, 148 articles were identified for potential inclusion, and after their full texts were examined, 61 papers were included in the present review after elimination of articles other than original research papers or those not relevant to the focus areas of the present review. All the three authors participated in study selection and reached a consensus regarding the papers to be included in the review. We neither performed a risk of bias assessment for individual studies nor computed effect estimates, as this was meant to be a narrative review.

Selected studies were categorized under three broad themes: studies that looked at the biological basis of the association between vitamin D and depression, studies that dealt with quantifying the association between vitamin D and depression, and trials that evaluated the effect of supplementing vitamin D in depression. Accordingly, in this review, we will discuss our search results under these three headings, and finally, we end with a discussion on knowledge gaps in these areas and recommendations to enrich and enhance future research.

RESULTS

Of a total of 148 full-text articles assessed, 116 (78.37 per cent) were published in the last ten years and 82 articles (55.41 per cent) were published in the last five years. These percentages clearly indicate the increasing research focus on the role of vitamin D in depression in the last decade. Totally, 61 articles were included in the present review. Of these, 46 were original articles, 13 were reviews/meta-analysis papers, and two were commentaries.

Vitamin D and depression: Biological underpinnings

The exact biological mechanisms linking vitamin D and depression are not fully understood. However, possible pathways include an imbalance in the calcium homeostasis of intracellular and extracellular compartments and a possible fallout of disequilibrium between glutamate, an excitatory neurotransmitter, and GABA, an inhibitory neurotransmitter. This, in turn, affects cellular signalling. Vitamin D may have a potential role in restoring this calcium and neurotransmitter imbalance by regulating intracellular calcium stores and cellular signalling and impacting the onset of depression favourably.[16]

Research has uncovered a possible neurotrophic and immunomodulatory role for vitamin D, leading many researchers to label it as a neurosteroid hormone.[17,18] Preclinical studies have shown that administration of vitamin D modulates the levels of inflammatory cytokines in the animal models of multiple sclerosis, a neurodegenerative condition with an inflammatory basis.[19] This is important because evidence suggests that depression is also a condition with elevated levels of systemic inflammation.[20,21] Increased region-specific expression of VDRs has been noted in the prefrontal and cingulate cortices, thalamus, amygdala, and hippocampus, all key brain areas implicated in the pathophysiology of depression.[22]

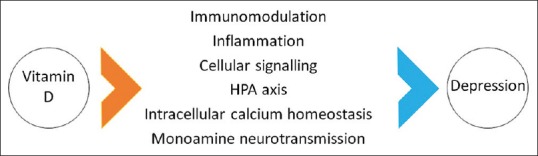

Furthermore, vitamin D modulates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, which regulates the production of the monoamine neurotransmitters epinephrine, norepinephrine, and dopamine in the adrenal cortex and also protects against the depletion of dopamine and serotonin.[23,24] Figure 1 summarizes the possible biological links between depression and vitamin D.

Figure 1.

Postulated biological links between vitamin D and depression. HPA: Hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical

The possibility of reverse causality too has been pointed out by prior investigators.[25,26] Certain factors related to depression can further increase the risk of vitamin D deficiency in an individual suffering from depression. Depressed individuals may avoid outdoor activity for prolonged periods of time (reducing sunlight exposure); poor appetite may lead to nutritional (and vitamin D) deficiency; metabolic derangements and increased demand for vitamin D (for restoring the calcium homeostasis) might further increase the risk of vitamin D deficiency in depression.

Evidence for the association between vitamin D and depression

Several cross-sectional studies,[27,28,29,30,31] few cohort studies,[32,33,34] and one case-control study[35] have examined the association. All the studies found that depressed subjects had lower levels of vitamin D compared to controls, and those with the lowest vitamin D levels had the greatest risk of depression (odds ratios 1.31, 95 per cent confidence interval [CI] 1.00–1.71). These values, though statistically significant, do not establish clinical relevance beyond doubt.

While both hospital-based[29,30,33,36] and community-based[27,37] trials show a link between low vitamin D levels and presence and severity of depressive symptoms, it is important to examine if these associations hold good after controlling for relevant demographic, lifestyle, and geographical factors. Encouragingly, community-based trials that controlled for age, gender, smoking, and body mass index have also found an inverse correlation between serum levels of 25(OH)D and levels of depression.[27,28]

These findings are partly tempered by the conclusions from two negative studies among the elderly; one a large Chinese epidemiologic study (n = 3,262) of men and women aged 50–70 years[38] that did not show any association between vitamin D and depression; and the other, a cohort study from Hong Kong (n = 939, all aged more than 65 years),[32] where no relationship was observed between baseline vitamin D level and depression status at four-year follow-up. Notably, both these studies showed that the odds ratios turned insignificant after adjusting for several key confounders.

Evidence for Vitamin D supplementation in depression

Vitamin D supplementation for depression in adults

Vitamin D metabolites are capable of crossing the blood–brain barrier,[39] and as mentioned before, VDRs are widespread in key brain areas implicated in depression, including the hippocampus.[17] Hence, it could be speculated that vitamin D supplementation may confer additional therapeutic benefits in depression.

Building on this premise, a number of trials with different methodologies have evaluated the efficacy of vitamin D supplementation in depression in the last decade. However, the findings have been somewhat inconsistent.[40,41,42] Partly, the reason may lie in the heterogeneity of trials with respect to sample size, study setting and design, the age range of participants, vitamin D dosing protocols, duration of the intervention, and the outcome measures used.

As studies using heterogeneous designs may be difficult to compare, it becomes important to examine results from randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Four RCTs[43,44,45,46] have evaluated the efficacy of supplemental vitamin D in patients with clinical depression. While three of them evaluated the efficacy of supplemental vitamin D, the fourth one studied the efficacy of vitamin D as an adjunct to standard anti-depressant therapy. All four trials demonstrated benefits for vitamin D, with effect sizes varying from moderate to large. On a discordant note, two recent RCTs[47,48] found no evidence of any beneficial effect of vitamin D3 supplementation on depressive symptoms or mood-related outcomes. Interestingly, both these negative studies were done on healthy population and not clinically depressed subjects.

Clinical improvement in depressive symptoms with vitamin D supplementation appears to vary depending on several methodological considerations. Spedding[49] noted that therapeutic benefits of vitamin D were more pronounced in studies with fewer ‘biological’ flaws (such as suboptimal dosing of vitamin D), and worsening in depressive symptoms with vitamin D supplementation was noted in studies with methodological flaws. These perspectives are supported by findings that higher dosages of vitamin D had a greater impact on mental health and wellbeing.[40,50,51]

Vitamin D supplementation in depression during pregnancy or peripartum period

Researchers have found a relationship between low serum vitamin D concentration during pregnancy and elevated postpartum[52,53] as well as antepartum depression.[54] On a conflicting note, a large nested case-control study (605 women with postpartum depression [PPD] and 875 controls) found a greater probability of postnatal depression with an increase in 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration.[55]

An Iranian RCT on pregnant women found that consuming 2,000 IU vitamin D3 daily during late pregnancy was effective in mitigating perinatal depressive symptoms.[56] In a cross-sectional study from Japan, higher dietary vitamin D intake was independently associated with a lower prevalence of depressive symptoms during pregnancy.[57]

One association study showed a significant inverse association between vitamin D levels and risk of antepartum (at 21 weeks, adjusted odds ratios [AOR] 0.54, 95 per cent CI 0.29–0.99) and PPD (at three days, AOR 2.72, 95 per cent CI 1.42–5.22).[58] Similarly, levels of vitamin D in early pregnancy were found to be a marker for elevated depression scores both in early and late pregnancy.[59] These results, though not conclusive, suggest a relationship between serum vitamin D levels and antepartum and PPD.

Vitamin D supplementation in depression in childhood and adolescence

Results from a review of 25 observational and eight longitudinal studies concluded a role for vitamin D in the pathogenesis of several child and adolescent psychiatric conditions, including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorders (ASD).[60] A case series of 54 adolescents with depression found a positive association between vitamin D levels and wellbeing and a greater improvement in depression with vitamin D supplementation.[61]

Only one completed RCT is available in this population. This six-month study, done on children with ASD aged 2–12 years, did not find significant benefits for daily oral supplementation of 2,000 IU of vitamin D on autism scores.[62] An RCT aimed at assessing the efficacy of vitamin D supplementation in children and adolescents with depressive disorder is currently underway.[63]

The salient features of supplementation trials described in this section are shown in Table 1. Overall, the available literature supports a relationship between vitamin D and depression in adults as well as children and adolescents. But, on a closer examination, there are several gaps in the evidence, which we outline below.

Table 1.

Salient features of vitamin D supplementation trials

| Author, year, place | Type of study/sampling | Sample size and characteristics | Intervention details | Main findings | Special remarks (if any) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jorde et al., 2008 Norway[40] | Randomized controlled trial | 441 subjects aged 21-70 years | Trial of 20,000 or 40,000 IU vitamin D per week versus placebo for 1 year | In the two groups given vitamin D, but not in the placebo group, there was a significant improvement in BDI scores after 1 year | Subjects with serum 25(OH)D levels <40 nmol/L scored significantly higher on the BDI total and the BDI subscale than those with levels >40 nmol/L |

| Kjærgaard et al., 2012 Norway[41] | Randomized controlled trial | 357 subjects aged 30-75 years with serum 25(OH)D levels below 55 nmol/l (n=243), those with serum 25(OH)D levels above 70 nmol/l (n=114) served as nested controls | Participants with low 25(OH)D levels were randomised to either placebo or 40 000 IU vitamin D(3) per week for 6 months | In the intervention study, no significant effect of high-dose vitamin D was found on depressive symptom scores when compared with placebo | Participants with low 25(OH)D levels at baseline were more depressed than participants with high 25(OH)D levels |

| Yalamanchili and Gallagher, 2012 United States[42] | Randomized controlled trial (secondary data) | 489 community dwelling elderly post-menopausal women aged 65-77 years | Three interventions: Hormonal therapy (conjugated equine estrogens with or without medroxyprogesterone acetate), calcitriol or combination therapy (HT plus calcitriol) and matching placebos for 3 years | There was no effect of hormone therapy, calcitriol or hormone therapy with calcitriol on depression | In post-menopausal women, there was no effect of hormone therapy and calcitriol either individually or in combination with depression. |

| Khoraminiya et al., 2013 Iran[43] | Randomized controlled trial | 42 outpatients aged 18-65 years with a diagnosis of MDD without psychotic features | Daily oral 1,500 IU of vitamin D3 plus 20 mg fluoxetine or placebo plus 20 mg fluoxetine for 8 weeks | Depression severity decreased significantly in the intervention group compared to controls. | Combination therapy was superior to fluoxetine alone in controlling mood symptoms from the fourth week of treatment |

| Mozaffari-Khosravi et al., 2013 Iran[44] | Randomized controlled trial | 120 subjects aged 20-60 years with depressive symptoms and vitamin D deficiency | Two single intramuscular injections equivalent to 300,000 IU (G300) and 150,000 IU (G150) of vitamin D were compared with a no treatment group (NTG) for 3 months | Significant improvement on Beck depression inventory scores was noted between G300 and NTG, but not between G150 and NTG groups | Correction of vitamin D deficiency also improved the depression state |

| Sepehrmanesh et al., 2016 Iran[45] | Randomized controlled trial | 40 patients aged 18-65 years with a diagnosis of MDD | Single capsule of 50,000 IU vitamin D per week (n=20) or placebo (n=20) for 8 weeks | A trend towards a greater decrease in the BDI was observed in the vitamin D group but not the placebo group | No statistically significant differences were observed |

| Wang et al., 2016 China[46] | Randomized controlled trial | 726 dialysis patients with depression | 52-week treatment of oral 50,000 IU per week of vitamin D3 versus a placebo control group | Depressive symptoms and BDI scores were not significantly improved in the test group versus the control group | Authors found a beneficial effect on the subtype of vascular depression |

| Choukri et al., 2018 New Zealand[47] | Randomized controlled trial | 152 healthy young adult women aged 18-40 years | 50, 000 IU of oral vitamin D3 or placebo once per month for 6 months | No benefits were noted in the intervention group with regard to depressive or anxiety outcomes over controls | |

| Jorde and Kubiak, 2018 Norway[48] | Randomized controlled trial | 408 healthy adult subjects aged 40 and above | Vitamin D 100,000 IU as a bolus dose (capsule) followed by 20,000 IU per week versus placebo for 4 months | BDI scores did not differ significantly between the vitamin D and placebo group | |

| Dumville et al., 2006 United Kingdom[50] | Randomized controlled trial | 2117 women aged 70 years or more | Daily oral supplementation of 800 IU if vitamin D plus information sheet on increasing calcium in diet versus only information sheet in controls | No significant differences were observed between the two groups on subjective psychological wellbeing scores | |

| Vieth et al., 2004 Canada[51] | Randomized controlled trial (two sequential partly overlapping studies) | Study 1: 64 outpatients with 25(OH)D <61 nmol/L) Study 2: 117 patients with serum 25(OH)D <51 nmol/L | Study 1: low dose supplementation (600 IU/day) versus high dose supplementation (4,000 IU/day) of vitamin D versus no supplementation for 2-6 months Study 2: Only supplementation arms were compared | In Study 1, wellbeing score improved more for the 100 mcg/day group than for the lower-dosed group. In Study 2, wellbeing scores improved with both doses of vitamin D |

High dose supplementation was superior to low dose supplementation in subjects with average higher levels of serum vitamin D |

| Vaziri et al., 2016 Iran[56] | Randomized controlled trial | 169 pregnant women aged 18 years or older with gestational age of 26-28 weeks and EPDS score of 0-13 | Intervention group received 2,000 IU vitamin D3 daily from 26 to 28 weeks of gestation until childbirth Control group received two placebo pills composed of starch daily for same period | Intervention group had greater reduction in depression scores than control group at 38-40 weeks of gestation and at 4 and 8 weeks after birth | Supplementation of vitamin D3 daily during late pregnancy was effective in decreasing perinatal depression levels |

| Föcker et al., 2018 Germany[63] | Randomized controlled trial (protocol only) | 200 inpatient children and adolescents (aged 11-18.9 years) with vitamin D deficiency and BDI score >13 | Intervention group will receive 2,640 I.E. vitamin D3 daily for 28 days along with TAU while placebo group will receive only TAU. After 28 days, both groups receive 1,000 I.E vitamin D daily for next 11 months | Awaited | Tests the hypothesis that delaying vitamin D supplementation in placebo group will impact improvement of depression scores |

| Azzam et al., 2015 Egypt[62] | Randomized controlled trial | 21 children with ASD aged 2-12 years | Intervention group received daily oral dose of 2,000 IU vitamin D3 versus no supplementation in placebo group (6-month study) | No significant differences between groups on ASD outcome scores | Limitation was that baseline 25(OH)D levels were lower in intervention group and levels did not rise following supplementation |

BDI: Beck depression inventory; MDD: Major depressive disorder; EPDS: Edinburg postnatal depression scale; TAU: Treatment as usual; ASD: Autism spectrum disorder

Gaps in understanding of the relationship between vitamin D and depression

Gaps in understanding of the association between vitamin D and depression

Much of the evidence linking vitamin D with depression in adults comes from cross-sectional studies.[64] Cohort or case-control studies are few and RCTs, considered superior for establishing causality, are even fewer.

As the bulk of the literature is from observational studies, several questions remain. Chief among them is the issue of small and unrepresentative samples, varying measures of depression (self-report vs. clinician-rated), and the potential problem of reverse causality. Given that two of the important negative studies came from China and Hong Kong, the issue of latitude moderating the association between vitamin D and depression needs further examination.

Owing to several sources of bias in existing studies and the danger of publication bias impacting the literature on vitamin D and depression, the possibility of a meta-analysis answering this question with finality remains bleak. More RCTs are therefore needed to examine the efficacy of supplemental vitamin D on prevention and treatment of depression.

Knowledge gaps in biological underpinnings between vitamin D and depression

Our understanding of the effect of vitamin D on neuronal brain function and behaviour is largely based on animal studies, and there are practically very few human studies. Studies examining the behavioural impact of VDR knock-out in mice have reported an increase in behaviours suggestive of heightened anxiety and psychosis, but not depression (such as greater immobility in tail suspension test).[65,66] Indeed, research attention on the effect of vitamin D on brain function has been more substantive in schizophrenia than depression.

The impact of vitamin D on monoamines involved in the pathobiology of depression is not well understood either. Vitamin D may upregulate genes involved in the synthesis of tyrosine hydroxylase, an enzyme involved in the synthesis of catecholamines.[18] A protective role for vitamin D in reducing the negative effects of dopaminergic toxins, possibly by increasing glial cell-line derived neurotrophic factor, has been proposed.[67,68] This may reciprocally affect serotonin transmission in the brain, given the links between dopaminergic and serotonergic systems. Preclinical models also point to a cross-talk between vitamin D and glucocorticoid receptors, and this may hold significance given the dysregulated hypothalamo-pituitary axis in depression.[69] Evidently, more human studies and animal models are required to further our understanding of biological links between vitamin D and depression. This will not only advance our understanding of the various pharmacological therapies but also, potentially, open up new therapeutic targets in depression.

Gaps in understanding the effect of vitamin D supplementation in depression

As summarized earlier, several trials that sought to evaluate the effect of supplemental vitamin D on depression have been published in the last five years. Two subtly different meta-analyses have attempted to summarize the existing data in this regard—one by Gowda et al.[70] that synthesized trials where the outcome of interest was subsyndromal depressive symptoms and the other by Vellekkatt and Menon[71] that only included trials on syndromal or clinical depression. The results were illuminating. The pooled effect size (standardized mean difference) in the first meta-analysis was 0.28 (95 per cent CI = –0.14 to 0.69) while in the second one, it was 0.58 (95 per cent CI = 0.45 to 0.72). This clearly indicates that adjunctive vitamin D may be more beneficial for subjects with clinical depression than subsyndromal depressive symptoms.

Interestingly, in the Gowda et al. paper, effects remained non-significant in subgroups stratified on serum 25(OH)D levels (cut-off of 50 nmol/l), vitamin D dosing used (cut-off of 4,000 IU/day), and whether vitamin D was used together with other supplements or anti-depressants, implying that these parameters may not be significant moderators in the relationship. Of note, there were limited trials in the Vellekkatt and Menon paper, with one trial contributing disproportionate weight in the meta-analysis. Several sources of bias, such as lack of allocation concealment and blinding, were also noted by the authors. As such, the garbage in, garbage out phenomenon cannot be ruled out.

From the above, it is clear that there are several unknowns in the literature. First, there is a need for larger and more rigorous trials to answer the question of whether the beneficial effects of vitamin D are different in subjects with subsyndromal depression versus syndromal major depression. Second, the biological plausibility that the beneficial effects of vitamin D may be higher in clinically depressed subjects with concurrent vitamin D deficiency emphatically merits further investigation.

And last, there is very little evidence among special populations like pregnant women or postpartum mothers. The available evidence is mostly cross-sectional, and we were able to find only one interventional study[56] in this group. Nevertheless, the positive results of this trial and another related trial that linked prenatal supplementation of vitamin D to a decrease in risk of schizophrenia in the offspring's life[72] are encouraging. Thus, whether supplemental vitamin D may exert benefits on primary prevention of depression is a question that needs to be systematically examined. Further, the directionality of the association between vitamin D and PPD is inconsistent because both high and low vitamin D levels have been shown to be associated with a risk of PPD.[73]

Other important gaps in evidence include a lack of clarity on whether a change in vitamin D levels parallels that of depressive symptoms following treatment. This would be expected if, indeed, vitamin D and depression share a cause–effect relationship. Studying the relationship between change in inflammatory marker status and vitamin D levels in major depression will throw more light on the three-way association and aid understanding of the mediating mechanisms involved in the purported benefits of vitamin D in depression.

Recommendations for future research

Based on the above, we propose the following recommendations that may be kept in mind by prospective researchers who intend to study the preventive and therapeutic roles of vitamin D in depression:

Use standard doses/duration/frequencies/route of administration of vitamin D: Preliminary evidence shows that oral and parenteral routes are comparable in efficacy, but compliance is likely to be of greater concern in oral supplementation. Parenteral supplementation may be more efficient in this regard, and there are supporting studies showing beneficial effects of a single adjunctive parenteral dose of vitamin D in depression[44]

Address key methodological issues: Based upon the findings from an interesting meta-analysis[49], which found a significantly higher effect size for vitamin D in depression when combining trials without methodological flaws, a few important recommendations can be made. First, researchers must avoid ineffective interventions, which in this context means those that do not change the vitamin D status of the patient. Second, researchers must strive to measure vitamin D levels of depressed subjects at baseline and target subjects with vitamin D deficiency (defined as levels less than 20 ng/ml) rather than vitamin D insufficiency (defined as 21–29 ng/ml) when the aim is to evaluate the therapeutic effects of supplemental vitamin D in depression.[74] Ethno-specific desirable reference ranges for vitamin D need to be computed, keeping in mind the effect of confounders such as age, sex, and ultraviolet B (UVB) radiation.[75] Whenever possible, the goal of supplementation must be to change the vitamin D status of the trial participant. As substantiated earlier, it also appears to be a sound idea to enrich vitamin D trials with depressed subjects also having concurrent vitamin D deficiency. Based on the available evidence, it appears that, for favourable benefits in depression, a supplemental dose of ≥800 IU daily for 4–6 weeks or a single parenteral dose of 3,00,000 IU of vitamin D should be given along with initiation of antidepressant treatment. The question of how long to continue supplementation is less clear, but it is probably beneficial to give until there is a change in vitamin D status of the patient (from deficient or insufficient to normal)

Use uniform assay procedures and outcome measures: This is necessary to facilitate inferences. Researchers must develop standard protocols for vitamin D assay and supplementation in clinical practice. The recommended assay to measure different types of vitamin D is the chromatographic procedure of liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS).[76] Uniform instruments must be used to assess depression outcomes of interest. Adhering to these steps would, undoubtedly, enhance cross-cultural comparability of findings

Identify depression subgroups that would benefit maximally from supplemental vitamin D: Just as there appears to exist an inflammatory biotype of depression,[77] it also seems plausible that there is a subset of patients with depression who may benefit maximally from vitamin D supplementation. The challenge for us is to find out that subpopulation, and enriched trials certainly appear to be a step forward to achieve this. From the available literature, it appears that patients who are obese, elderly, adolescent, or homebound and those with chronic illness may be more likely to benefit from vitamin D-based interventions, and this merits further study

Estimate concurrent changes in vitamin D, inflammatory markers, and depression: Researchers should try to evaluate whether changes in vitamin D levels and systemic inflammatory markers parallel that of depression scores. This will provide further evidence to support the links between vitamin D and depression and also give valuable insights into the biological mechanisms behind this association

Investigate the benefits of suprathreshold dosing of vitamin D: Thus far, the available trials have only looked at using supplementation to correct preexisting vitamin D deficiency. It may be worthwhile to check if additional supplementation helps with residual symptom management in depression and prevention of further episodes

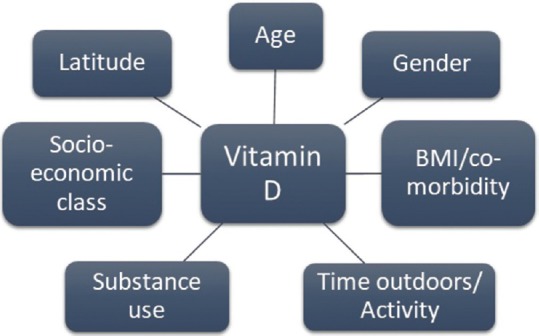

Adequate adjustment for confounding factors: This is important, to avoid the danger of spurious associations. There are many important confounders that researchers should be aware of, and these include both demographic and lifestyle factors. Additionally, in special populations such as postpartum mothers, controlling for variables including, but not limited to, social support, the gender of the baby, and the educational status of the mother assumes significance. Figure 2 depicts the key confounding factors in the relationship between vitamin D and depression.

Figure 2.

Key confounders in the relationship between vitamin D and depression

CONCLUSION

The evidence clearly supports a relationship between vitamin D and depression, though the directionality of the association can be contested. This is partly because most of the evidence comes from cross-sectional studies. The biological links between the two can be explained on the basis of the homeostatic, immunomodulatory, and neuroprotective roles of vitamin D. Pooled evidence from RCTs suggest superior therapeutic benefits of vitamin D supplementation in clinical, rather than subsyndromal, depression. Many gaps in evidence remain, and this must be addressed through future trials that employ uniform assays, dosing protocols, and outcome measures. Adequate control of confounders and enriching depression trials with subjects also having concurrent vitamin D deficiency appear to be key steps forward in delivering results that would be scientifically sound, valid, and translational.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders. Global Health Estimates [Internet] 2017. [Last cited on 2019 Feb 22]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/254610/WHO-MSD-MER-2017.2-eng.pdf?sequence=1 .

- 2.Barefoot JC, Schroll M. Symptoms of depression, acute myocardial infarction, and total mortality in a community sample. Circulation. 1996;93:1976–80. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.11.1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jonas BS, Mussolino ME. Symptoms of depression as a prospective risk factor for stroke. Psychosom Med. 2000;62:463–71. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200007000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kessler RC, Borges G, Walters EE. Prevalence of and risk factors for lifetime suicide attempts in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:617–26. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.7.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ford JD, Trestman RL, Steinberg K, Tennen H, Allen S. Prospective association of anxiety, depressive, and addictive disorders with high utilization of primary, specialty and emergency medical care. Soc Sci Med 1982. 2004;58:2145–8. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kessler RC, Akiskal HS, Ames M, Birnbaum H, Greenberg P, Hirschfeld RMA, et al. Prevalence and effects of mood disorders on work performance in a nationally representative sample of U.S. workers. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1561–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.9.1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnston KM, Powell LC, Anderson IM, Szabo S, Cline S. The burden of treatment-resistant depression: A systematic review of the economic and quality of life literature. J Affect Disord. 2019;242:195–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mauskopf JA, Simon GE, Kalsekar A, Nimsch C, Dunayevich E, Cameron A. Nonresponse, partial response, and failure to achieve remission: Humanistic and cost burden in major depressive disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26:83–97. doi: 10.1002/da.20505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Köhler O, Krogh J, Mors O, Benros ME. Inflammation in depression and the potential for anti-inflammatory treatment. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2016;14:732–42. doi: 10.2174/1570159X14666151208113700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Menon V, Ameen S. Immunoinflammatory therapies in psychiatry: Current evidence base. Indian J Psychol Med. 2017;39:721–6. doi: 10.4103/IJPSYM.IJPSYM_505_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prüfer K, Veenstra TD, Jirikowski GF, Kumar R. Distribution of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 receptor immunoreactivity in the rat brain and spinal cord. J Chem Neuroanat. 1999;16:135–45. doi: 10.1016/s0891-0618(99)00002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mora JR, Iwata M, von Andrian UH. Vitamin effects on the immune system: Vitamins A and D take centre stage. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:685–98. doi: 10.1038/nri2378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Etten E, Stoffels K, Gysemans C, Mathieu C, Overbergh L. Regulation of vitamin D homeostasis: Implications for the immune system. Nutr Rev. 2008;66(10 Suppl 2):S125–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buell JS, Dawson-Hughes B. Vitamin D and neurocognitive dysfunction: Preventing “D”ecline? Mol Aspects Med. 2008;29:415–22. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Song C, Wang H. Cytokines mediated inflammation and decreased neurogenesis in animal models of depression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2011;35:760–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berridge MJ. Vitamin D and depression: Cellular and regulatory mechanisms. Pharmacol Rev. 2017;69:80–92. doi: 10.1124/pr.116.013227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eyles DW, Smith S, Kinobe R, Hewison M, McGrath JJ. Distribution of the vitamin D receptor and one alpha-hydroxylase in human brain. J Chem Neuroanat. 2005;29:21–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garcion E, Wion-Barbot N, Montero-Menei CN, Berger F, Wion D. New clues about vitamin D functions in the nervous system. Trends Endocrinol Metab TEM. 2002;13:100–5. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(01)00547-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cantorna MT, Woodward WD, Hayes CE, DeLuca HF. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 is a positive regulator for the two anti-encephalitogenic cytokines TGF-beta 1 and IL-4. J Immunol Baltim Md 1950. 1998;160:5314–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller AH, Raison CL. The role of inflammation in depression: From evolutionary imperative to modern treatment target. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16:22–34. doi: 10.1038/nri.2015.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muthuramalingam A, Menon V, Rajkumar RP, Negi VS. Is depression an inflammatory disease? findings from a cross-sectional study at a tertiary care center. Indian J Psychol Med. 2016;38:114. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.178772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Drevets WC, Price JL, Furey ML. Brain structural and functional abnormalities in mood disorders: Implications for neurocircuitry models of depression. Brain Struct Funct. 2008;213:93–118. doi: 10.1007/s00429-008-0189-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muscogiuri G, Altieri B, Penna-Martinez M, Badenhoop K. Focus on vitamin D and the adrenal gland. Horm Metab Res Horm Stoffwechselforschung Horm Metab. 2015;47:239–46. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1396893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wierzbicka JM, Żmijewski MA, Piotrowska A, Nedoszytko B, Lange M, Tuckey RC, et al. Bioactive forms of vitamin D selectively stimulate the skin analog of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis in human epidermal keratinocytes. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2016;437:312–22. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2016.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bertone-Johnson ER. Vitamin D and the occurrence of depression: Causal association or circumstantial evidence? Nutr Rev. 2009;67:481–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2009.00220.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parker G, Brotchie H. “D” for depression: Any role for vitamin D.“Food for Thought” II? Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2011;124:243–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoogendijk WJ, Lips P, Dik MG, Deeg DJ, Beekman AT, Penninx BW. Depression is associated with decreased 25-hydroxyvitamin D and increased parathyroid hormone levels in older adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:508–12. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.5.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee DM, Tajar A, O’Neill TW, O’Connor DB, Bartfai G, Boonen S, et al. Lower vitamin D levels are associated with depression among community-dwelling European men. J Psychopharmacol Oxf Engl. 2011;25:1320–8. doi: 10.1177/0269881110379287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilkins CH, Birge SJ, Sheline YI, Morris JC. Vitamin D deficiency is associated with worse cognitive performance and lower bone density in older African Americans. J Natl Med Assoc. 2009;101:349–54. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30883-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilkins CH, Sheline YI, Roe CM, Birge SJ, Morris JC. Vitamin D deficiency is associated with low mood and worse cognitive performance in older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry Off J Am Assoc Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:1032–40. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000240986.74642.7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao G, Ford ES, Li C. Associations of serum concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D and parathyroid hormone with surrogate markers of insulin resistance among U.S. adults without physician-diagnosed diabetes: NHANES, 2003–2006. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:344–7. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chan R, Chan D, Woo J, Ohlsson C, Mellström D, Kwok T, et al. Association between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and psychological health in older Chinese men in a cohort study. J Affect Disord. 2011;130:251–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.May HT, Bair TL, Lappé DL, Anderson JL, Horne BD, Carlquist JF, et al. Association of vitamin D levels with incident depression among a general cardiovascular population. Am Heart J. 2010;159:1037–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Milaneschi Y, Hoogendijk W, Lips P, Heijboer AC, Schoevers R, van Hemert AM, et al. The association between low vitamin D and depressive disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19:444–51. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eskandari F, Martinez PE, Torvik S, Phillips TM, Sternberg EM, Mistry S, et al. Low bone mass in premenopausal women with depression. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:2329–36. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.21.2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou Q, Shao Y, Gan Z, Fang L. Lower vitamin D levels are associated with depression in patients with gout [Internet] Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:227–31. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S193114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ganji V, Milone C, Cody MM, McCarty F, Wang YT. Serum vitamin D concentrations are related to depression in young adult US population: The Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Int Arch Med. 2010;3:29. doi: 10.1186/1755-7682-3-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pan A, Lu L, Franco OH, Yu Z, Li H, Lin X. Association between depressive symptoms and 25-hydroxyvitamin D in middle-aged and elderly Chinese. J Affect Disord. 2009;118:240–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Diesel B, Radermacher J, Bureik M, Bernhardt R, Seifert M, Reichrath J, et al. Vitamin D(3) metabolism in human glioblastoma multiforme: Functionality of CYP27B1 splice variants, metabolism of calcidiol, and effect of calcitriol. Clin Cancer Res Off J Am Assoc Cancer Res. 2005;11:5370–80. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jorde R, Sneve M, Figenschau Y, Svartberg J, Waterloo K. Effects of vitamin D supplementation on symptoms of depression in overweight and obese subjects: Randomized double blind trial. J Intern Med. 2008;264:599–609. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2008.02008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kjærgaard M, Waterloo K, Wang CEA, Almås B, Figenschau Y, Hutchinson MS, et al. Effect of vitamin D supplement on depression scores in people with low levels of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D: Nested case-control study and randomised clinical trial. Br J Psychiatry J Ment Sci. 2012;201:360–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.104349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yalamanchili V, Gallagher JC. Treatment with hormone therapy and calcitriol did not affect depression in older postmenopausal women: No interaction with estrogen and vitamin D receptor genotype polymorphisms. Menopause N Y N. 2012;19:697–703. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31823bcec5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Khoraminya N, Tehrani-Doost M, Jazayeri S, Hosseini A, Djazayery A. Therapeutic effects of vitamin D as adjunctive therapy to fluoxetine in patients with major depressive disorder. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2013;47:271–5. doi: 10.1177/0004867412465022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mozaffari-Khosravi H, Nabizade L, Yassini-Ardakani SM, Hadinedoushan H, Barzegar K. The effect of 2 different single injections of high dose of vitamin D on improving the depression in depressed patients with vitamin D deficiency: A randomized clinical trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;33:378–85. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e31828f619a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sepehrmanesh Z, Kolahdooz F, Abedi F, Mazroii N, Assarian A, Asemi Z, et al. Vitamin D supplementation affects the beck depression inventory, insulin resistance, and biomarkers of oxidative stress in patients with major depressive disorder: A randomized, controlled clinical trial. J Nutr. 2016;146:243–8. doi: 10.3945/jn.115.218883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang Y, Liu Y, Lian Y, Li N, Liu H, Li G. Efficacy of high-dose supplementation with oral vitamin D3 on depressive symptoms in dialysis patients with vitamin D3 insufficiency: A prospective, randomized, double-blind study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2016;36:229–35. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0000000000000486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Choukri MA, Conner TS, Haszard JJ, Harper MJ, Houghton LA. Effect of vitamin D supplementation on depressive symptoms and psychological wellbeing in healthy adult women: A double-blind randomised controlled clinical trial. J Nutr Sci. 2018;7:e23. doi: 10.1017/jns.2018.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jorde R, Kubiak J. No improvement in depressive symptoms by vitamin D supplementation: Results from a randomised controlled trial. J Nutr Sci. 2018;7:e30. doi: 10.1017/jns.2018.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Spedding S. Vitamin D and depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis comparing studies with and without biological flaws. Nutrients. 2014;6:1501–18. doi: 10.3390/nu6041501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dumville JC, Miles JNV, Porthouse J, Cockayne S, Saxon L, King C. Can vitamin D supplementation prevent winter-time blues? A randomised trial among older women. J Nutr Health Aging. 2006;10:151–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vieth R, Kimball S, Hu A, Walfish PG. Randomized comparison of the effects of the vitamin D3 adequate intake versus 100 mcg (4000 IU) per day on biochemical responses and the wellbeing of patients. Nutr J. 2004;3:8. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-3-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Murphy PK, Mueller M, Hulsey TC, Ebeling MD, Wagner CL. An exploratory study of postpartum depression and vitamin D. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2010;16:170–7. doi: 10.1177/1078390310370476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Robinson M, Whitehouse AJO, Newnham JP, Gorman S, Jacoby P, Holt BJ, et al. Low maternal serum vitamin D during pregnancy and the risk for postpartum depression symptoms. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2014;17:213–9. doi: 10.1007/s00737-014-0422-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brandenbarg J, Vrijkotte TGM, Goedhart G, van Eijsden M. Maternal early-pregnancy vitamin D status is associated with maternal depressive symptoms in the Amsterdam born children and their development cohort. Psychosom Med. 2012;74:751–7. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3182639fdb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nielsen NO, Strøm M, Boyd HA, Andersen EW, Wohlfahrt J, Lundqvist M, et al. Vitamin D status during pregnancy and the risk of subsequent postpartum depression: A case-control study. PloS One. 2013;8:e80686. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vaziri F, Nasiri S, Tavana Z, Dabbaghmanesh MH, Sharif F, Jafari P. A randomized controlled trial of vitamin D supplementation on perinatal depression: In Iranian pregnant mothers. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16:239. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-1024-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Miyake Y, Tanaka K, Okubo H, Sasaki S, Arakawa M. Dietary vitamin D intake and prevalence of depressive symptoms during pregnancy in Japan. Nutr Burbank Los Angel Cty Calif. 2015;31:160–5. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2014.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aghajafari F, Letourneau N, Mahinpey N, Cosic N, Giesbrecht G. Vitamin D deficiency and antenatal and postpartum depression: A systematic review. Nutrients. 2018;10 doi: 10.3390/nu10040478. pii: E478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Williams JA, Romero VC, Clinton CM, Vazquez DM, Marcus SM, Chilimigras JL, et al. Vitamin D levels and perinatal depressive symptoms in women at risk: A secondary analysis of the mothers, omega-3, and mental health study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16:203. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-0988-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Föcker M, Antel J, Ring S, Hahn D, Kanal Ö, Öztürk D, et al. Vitamin D and mental health in children and adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;26:1043–66. doi: 10.1007/s00787-017-0949-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Högberg G, Gustafsson SA, Hällström T, Gustafsson T, Klawitter B, Petersson M. Depressed adolescents in a case-series were low in vitamin D and depression was ameliorated by vitamin D supplementation. Acta Paediatr Oslo Nor 1992. 2012;101:779–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2012.02655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Azzam HME, Sayyah H, Youssef S, Lotfy H, Abdelhamid IA, Abd Elhamed HA, et al. Autism and vitamin D: An intervention study. Middle East Curr Psychiatry. 2015;22:9–14. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Föcker M, Antel J, Grasemann C, Führer D, Timmesfeld N, Öztürk D, et al. Effect of an vitamin D deficiency on depressive symptoms in child and adolescent psychiatric patients-a randomized controlled trial: Study protocol. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18:57. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1637-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Anglin RES, Samaan Z, Walter SD, McDonald SD. Vitamin D deficiency and depression in adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202:100–7. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.106666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Harms LR, Eyles DW, McGrath JJ, Mackay-Sim A, Burne THJ. Developmental vitamin D deficiency alters adult behaviour in 129/SvJ and C57BL/6J mice. Behav Brain Res. 2008;187:343–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kalueff AV, Keisala T, Minasyan A, Kuuslahti M, Miettinen S, Tuohimaa P. Behavioural anomalies in mice evoked by “Tokyo” disruption of the Vitamin D receptor gene. Neurosci Res. 2006;54:254–60. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cass WA, Smith MP, Peters LE. Calcitriol protects against the dopamine- and serotonin-depleting effects of neurotoxic doses of methamphetamine. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1074:261–71. doi: 10.1196/annals.1369.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Smith MP, Fletcher-Turner A, Yurek DM, Cass WA. Calcitriol protection against dopamine loss induced by intracerebroventricular administration of 6-hydroxydopamine. Neurochem Res. 2006;31:533–9. doi: 10.1007/s11064-006-9048-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Obradovic D, Gronemeyer H, Lutz B, Rein T. Cross-talk of vitamin D and glucocorticoids in hippocampal cells. J Neurochem. 2006;96:500–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gowda U, Mutowo MP, Smith BJ, Wluka AE, Renzaho AM. Vitamin D supplementation to reduce depression in adults: Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutr Burbank Los Angel Cty Calif. 2015;31:421–9. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2014.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vellekkatt F, Menon V. Efficacy of vitamin D supplementation in major depression: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Postgrad Med. 2018;65:74–80. doi: 10.4103/jpgm.JPGM_571_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Freedman R, Hunter SK, Hoffman MC. Prenatal primary prevention of mental illness by micronutrient supplements in pregnancy. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175:607–19. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17070836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Amini S, Jafarirad S, Amani R. Postpartum depression and vitamin D: A systematic review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2019;59:1514–20. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2017.1423276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gallagher JC, Sai AJ. Vitamin D insufficiency, deficiency, and bone health. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:2630–3. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ferrari D, Lombardi G, Banfi G. Concerning the vitamin D reference range: Pre-analytical and analytical variability of vitamin D measurement. Biochem Medica. 2017;27:030501. doi: 10.11613/BM.2017.030501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jones G. Interpreting vitamin D assay results: Proceed with caution. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol CJASN. 2015;10:331–4. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05490614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Raison CL, Miller AH. Is depression an inflammatory disorder? Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2011;13:467–75. doi: 10.1007/s11920-011-0232-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]