We report an 11-month-old boy who presented with inconsolable crying, swelling, and decreased use of left lower limb since the age of 8 months. Child was apparently well until the age of 8 month when the parents noticed crying due to pain. Initially pain was intermittent and mild: however, it increased progressively in intensity and frequency. At the time of presentation pain was so severe that he had to be given analgesic at least twice to have a proper sleep. Apart from this problem his history was unremarkable since birth. Parent had sought treatment at nearby hospital where analgesics were given, but as the child did not improve radiographs followed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of affected extremity weredone [Figure 1a and b]. Despite extensive work-up the diagnosis was not clear and he was referred to our institute with differential diagnosis of osteomyelitis or Ewing tumor as per MRI report.

Figure 1.

(a) Plain radiograph showing nidus surrounded by sclerosis. (b) MRI showing areas of hyperechogenicity. (c) CT scan showing intramedullary nidus

On examination, the child was well nourished and alert. There was a diffuse ill-defined swelling of 5 × 4 cm on the anteromedial aspect of left tibia which was bony hard and tender. Local temperature and overlying skin were normal. Affected leg circumference was increased by 1 cm; there was no limb length discrepancy, no signs of neurovascular compromise and no restriction of range of motion of affected joint.

As there was no sign of malignant disease on examination and there was a radiolucent shadow in radiograph, we did computed tomography (CT) scan of affected extremity to confirm the diagnosis of osteoid osteoma. CT scan of tibia confirmed our diagnosis [Figure 1c]. An excision biopsy of suspected nidus using an anteromedial approach to tibia was done. A bone window was made, nidus and surrounding bone was curetted and sent for histopathological examination [Figure 2a]. Diagnosis of osteoid osteoma was confirmed histopathologically [Figure 2c]. On 1-year follow-up the child was asymptomatic and radiographs revealed a healed bony window [Figure 2b].

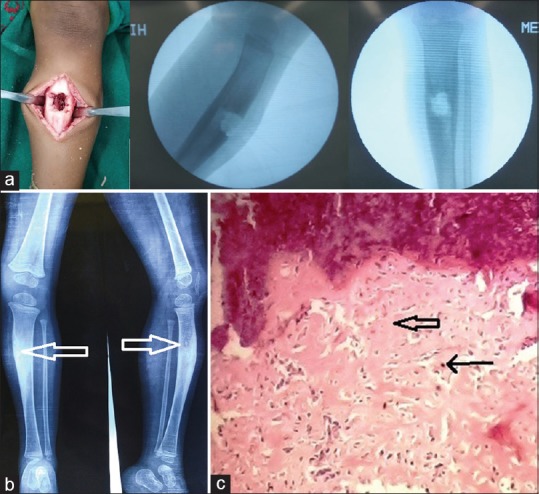

Figure 2.

(a) Intraoperative pictures showing bone window. (b) Plain radiograph showing healed bone window. (c) Photomicrograph showing anastomosing bony trabeculae (broad arrow) rimmed by osteoblasts (thin arrow) (H and E, ×400)

Osteoid osteoma very rarely presents in less than 1 year of age. Restlessness, inability to sleep at night, decreased use of affected limb, and absence of kicking are reported presentation of osteoid osteoma in children.[1,2,3] Limb length discrepancy, wasting, deformity, and swelling are also common findings in a child suspected to having osteoid osteoma.[1,4]

Three types of osteoid osteoma based on the radiographic localization of nidus have been described in literature: cortical (if nidus is within cortex), subperiosteal (if nidus is located outside the cortex, surrounded by periosteal reaction), and intramedullary (if nidus is located inside medullary cavity). Intramedullary (also known as cancellous) osteoid osteoma is relatively rare.

In our patient, nidus was located intramedullary, which was a diagnostic challenge because the typical radiographic finding of central lucent zone(nidus) and sclerosis of the surrounding bone tissue was minimal. CT scan is regarded as best investigation to locate nidus and confirm the diagnosis of osteoid osteoma. The tumor nidus may be difficult to identify on MRI. The presentation of intramedullary osteoid osteomas is often mistaken for Ewing's sarcoma.

CT-guided percutaneous radiofrequency thermal ablation is considered treatment of choice for osteoid osteoma. Its role for children and in intramedullary osteoid osteoma is still under evaluation.[5]

Complete surgical removal of nidus is preferred treatment in children to prevent bony deformity, limb length discrepancy, and recurrence.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that appropriate patient consent was obtained.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Habermann ET, Stern RE. Osteoid-osteoma of the tibia in an eight-month-old boy: A case report. JBJS. 1974;56:633–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laurence N, Epelman M, Markowitz RI, Jaimes C, Jaramillo D, Chauvin NA. Osteoid osteomas: A pain in the night diagnosis. Pediatr Radiol. 2012;42:1490–501. doi: 10.1007/s00247-012-2495-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Purcell HM, Mills SD, Lipscomb PR. Osteoid osteoma in childhood. Pediatrics. 1952;9:295–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sherman MS. Osteoid osteoma: Review of the literature and report of thirty cases. JBJS. 1947;29:918–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Virayavanich W, Singh R, O'Donnell RJ, Horvai AE, Goldsby RE, Link TM. Osteoid osteoma of the femur in a 7-month-old infant treated with radiofrequency ablation. Skeletal Radiol. 2010;39:1145–9. doi: 10.1007/s00256-010-1014-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]