Abstract

The development of research training opportunities for investigators from the untapped pool of traditionally underrepresented racial/ethnic groups has gained intense interest at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The significant and persistent disparity in the likelihood of R01 funding between African American and Whites was highlighted in the groundbreaking 2011 report, Race, Ethnicity, and NIH Research Awards. Disparities in funding success were also shown to exist at the institutional level, as 30 institutions receive a disproportionate share of federal research funding. Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) have a dual commitment to education and research; however, the teaching loads at HBCUs may present challenges for research-oriented faculty. Few research training and mentoring programs have been specifically designed for this group.

During 2015 and 2016, we held three conversation cafés with 77 participants in Jackson, Mississippi and Baltimore, Maryland. The purpose of this article is to describe findings from these conversation cafés regarding barriers and facilitators to building robust research careers at HBCUs, and to illustrate how these data were used to adapt the conceptual framework for the NHLBI-funded Obesity Health Disparities (OHD) PRIDE program. Identified barriers included teaching and advising loads, infrastructures, and lack of research mentors on campus. The benefit of incorporating research into classroom teaching was a noted facilitator.

Keywords: Research Training and Mentoring, Health Disparities, Obesity Research, Population Health

Introduction

Overweight and obesity are major risk factors for cardiometabolic multimorbidity (ie, type 2 diabetes, coronary heart disease, and stroke).1 Recent analyses of the 2015-2016 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) indicate that nearly 40% (39.8%) of adults in the United States are overweight and a similar percentage (39.6%) are obese, which represents a considerable increase from the prior decade.2 Racial and ethnic health disparities in obesity persist. Compared with Whites (37.9%), Hispanics (47.0%) and African Americans (46.8%) have significantly higher rates of obesity.2 Over the next 20 years, the prevalence of obesity and obesity-related diseases, as well as their associated health care costs, are projected to increase in every state in the nation. Estimates suggest that a staggering 42% of American adults will be obese by the year 2030,3 with a similar increase in heart disease morbidity and premature mortality. Numerous reports have called for new interventions to prevent obesity and mitigate the current high rates of obesity and their projected rise.4,5 Part of the response to these calls involves expansion of the overall biomedical workforce in the United States.

The need to improve biomedical workforce training has been outlined in numerous national reports, and evidence indicates that this issue is particularly salient for individuals from underrepresented groups.6, 7 In the 2016 report “Charting the Future Together: The NHLBI Strategic Vision,” the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) calls for developing and sustaining the diversity of a scientific workforce capable of accomplishing this mission.8 Research training and mentoring programs for faculty from underrepresented backgrounds are particularly valuable because of potential “ripple effects” that extend beyond individual faculty members’ careers to their students, peers, and institutional environments, thereby opening the “health profession and research workforce pipeline.” 8 Without a significant investment in faculty training and mentoring, the United States is unlikely to achieve the nation’s goals for diversity in the biomedical research workforce.9 Increasing the size and diversity of the biomedical research workforce in the field of obesity health disparities is a critical component of achieving NHLBI’s mission, and is essential to the national goal of reducing the proportion of adults who are obese to 33.9% by 2020.10

Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) are unique institutions of higher learning that have played a significant role in educating African Americans in the United States.11,12 These institutions emerged after the Civil War, when freed slaves were not permitted to attend “White” colleges and universities, a restriction that persisted with few exceptions until the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and success of the civil rights movement in the late 1960s. HBCUs were founded with the principal mission of educating African Americans, primarily in liberal arts, vocational and religious education, and manual trades.13-15 Currently, 101 institutions16 are classified as HBCUs, representing 3% of all colleges and universities in the United States.17

Approximately 9% of all African American college students attend HBCUs; however, graduates of these institutions represent 17%, 31%, and 31% of the bachelor degrees awarded to African Americans in the health professions, biological sciences, and mathematics, respectively.14,18 HBCUs educate more than 330,000 underrepresented minority (URM) students annually, encouraging many to consider and become prepared for careers in biomedicine.19,20 In this light, faculty at HBCUs are in an unparalleled position to serve as critical role models for minority students and represent a source of untapped talent to diversify the biomedical workforce and contribute to the production of high-quality research.

Obesity Health Disparities (OHD PRIDE) is one of nine Programs to Increase Diversity Among Individuals Engaged in Health-Related Research (PRIDE) funded by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) to develop and implement a comprehensive research training and mentoring program for early-career faculty members from groups that are underrepresented in the biomedical sciences. There is very little guidance in the scientific literature to direct the development of research training programs for early career faculty of color, and even less on training and mentoring for those employed in HBCUs. Faculty at HBCUs often have heavy teaching loads (typically 12 credit hours or more per semester) and demanding service obligations, particularly in terms of advising and committee service. Science faculty are often challenged by limited research laboratory space and access to core facilities, minimal funding for postdocs and graduate research assistants, lack of institutional support for developing grant proposals, and less than a critical mass of research peers and mentors.16,17,21

OHD PRIDE’s experience with this group has identified a range of barriers and facilitators that can be addressed and leveraged, respectively, through a tailored research training and mentoring program to promote their professional development as researchers. The objective of this article is to examine the research-related challenges faced by early career faculty employed in HBCUs and other teaching intensive institutions, and how they have motivated the emergence and evolution of the conceptual framework undergirding the OHD PRIDE program.

Methods

Sample

Individuals contributing to the formation of our conceptual framework were early-career faculty and research leaders from HBCUs in Mississippi and Baltimore, Maryland. Potential participants for the formative portion of OHD PRIDE were recruited through word-of-mouth, email blasts, direct invitation, and postings on university websites to participate in a focus group conducted via conversation cafés. Conversation cafés are creative organizational or social design processes and a user-friendly tool for catalyzing conversations that enhance collective thought and lead to momentum for innovation.22 A total of 77 individuals participated in one of three cafés held in 2015 and 2016. Two cafés were held in Jackson, Mississippi (n=65) and one in Baltimore, Maryland (n=12). This formative work was approved by the institutional review board at the University of Mississippi Medical Center as part of the OHD PRIDE protocol.

Procedure

Cafés were used to gather crucial information regarding factors that predispose, facilitate, reinforce, and impede productive research careers among early career faculty members from HBCUs. Cafés were held during lunchtime periods when faculty members were not typically scheduled to teach classes. Provocative, thought-provoking questions were placed on index cards at each table to stimulate robust discussion facilitated by table “hosts” trained as focus group moderators. During each 90-minute café, participants were asked to join three separate table discussions; this approach permitted in-depth conversations and served to facilitate a cross-pollination of ideas. As the iterative rounds of conversation occurred, each table host remained to welcome the new arrivals.

Topic guides used for each café included questions regarding barriers to developing robust research careers and suggestions to overcome those barriers, experiences with securing and working with research mentors, and factors likely to motivate faculty in teaching-intensive institutions to participate in intensive research mentoring programs (Table 1). Participants’ responses were captured on flip charts, combined into an official “transcript’ of each café session, and then analyzed to code themes. Monetary compensation for participants’ time was not provided, but lunch was served. Following the first two cafés, the investigative team noted a pattern of thematic repetition, therefore the cafés concluded with the third group.

Table 1. Conversation café topic guide.

| 1) Imagine a work environment in which early career faculty members are supported and encouraged to launch and maintain productive academic careers balancing research, teaching, and service. |

| 1a) How does this environment look? |

| 1b) What types of support and encouragement are needed? |

| 2) Describe any negative experiences you have had or comments you have heard, as a result of being educated by and/or being a faculty member at an HBCU? |

| 3) Describe and discuss barriers to the development of a robust research career that you have experienced, or of which you are aware. Consider barriers at the institutional and individual levels. What changes are needed to overcome these barriers? |

| 4) Numerous studies have reported that underrepresented minority and female faculty typically receive less mentoring than their nonminority peers. Finding senior mentors however, can be a significant challenge. Describe and discuss your experience with obtaining and working with research mentors. |

| 4a) Describe what mentoring means to you. |

| 5) Student education remains the principal mission of HBCUs. Consequently, many faculty members employed in HBCUs maintain high teaching loads, which require a significant amount of time. List up to three things that HBCU faculty can do to carve out sufficient time to also have a successful research career. |

| 6) Describe the importance of research to your career. |

| 7) Participation in well-structured 1- to 2-year mentoring programs have been highly correlated with successful research careers. What factors are likely to motivate early career faculty members at HBCUs to participate in intensive mentoring programs? |

| 7a) What resources could be utilized to retain early career faculty members in such programs? |

Analysis

A thematic analysis of the café data was conducted through content coding and construction of a conceptually clustered matrix.23 After development of a codebook, two members of the investigative team reviewed the notes from each café and coded the challenges and facilitators to conducting research on their campuses and suggestions for designing a training and mentoring program. Codes were used to develop a scheme in which larger thematic categories were identified. Groups rather than individuals were the unit of analysis.

Results

Findings from our conversation cafés highlighted considerable barriers to research productivity for early-career faculty at HBCUs. The thematic analysis yielded four categories, three significant barriers: 1) access; 2) bias; and 3) teaching and advising loads; and 4) one facilitator: the potential to introduce and engage undergraduate students in research, particularly those who are from groups underrepresented in biomedical science. Sub-categories were also identified within each thematic area (identified by single quote marks).

Access

Lack of access to research-related resources on campus (eg, mentors, robust journal collections, and assistance with research administration) was strongly affirmed in each cafe. One theme mentioned by participants in all three groups was the important, but daunting challenge of ‘identifying an experienced mentor with common research interests’ to assist with manuscript and grant writing. One participant commented, “I did not have a mentor, but was given a manual to work from.” Some participants noted that they looked outside their department and institution for mentoring: one participant remarked, “I came to do a job and I will figure out how to get it done. I will find a mentor, even in another area.”

Participants unanimously mentioned limitations with library facilities, including a lack of access to research journals, ‘infrastructure issues’ (internet speed, hours, etc.) and databases. Summarizing a general view regarding a lack of resources, one participant stated, “these barriers often require faculty to allocate additional time to find critically needed resources, thereby reducing overall research productivity.” Lack of personnel to assist with research administrative tasks (budget preparation and management, scientific editing, etc.) were additional infrastructure challenges mentioned in each café. Collectively, these issues were reported to “reduce the enthusiasm for conducting research due to lack of support.”

Bias

Race, Ethnicity, and NIH Research Awards,24 also known as the Ginther Report, was a groundbreaking report of an NIH-commissioned study documenting the significant disparity in the likelihood of R01 funding (FY 2000-2006) between African American (13.2 points less likely) and White applicants. The persistence of this funding disparity was demonstrated by recent analyses of the NIH award data from FY 2010-201525; African American scientists are funded at 50% of the rate of White scientists.25,26 Disparities in funding success were also found at the institutional level, as 30 institutions receive a disproportionate share of federal research funding.24 Collectively, results from these studies suggest that African American faculty at HBCUs are likely to be at a ‘triple disadvantage’ as these factors combine to undermine the probability of these faculty having a successful research career. Café participants were acutely aware of the Ginther report and indicated that “degrees from HBCUs are often devalued compared with predominately White institutions (PWIs), “students and faculty are often challenged about their knowledge base,” and that “faculty are incompetent in conducting research.” Participants expressed concern about the impossibility of separating individual biases from judgement in professional settings, and how these factors may shed a negative light during peer review of manuscripts and grants.

Teaching and Advising Loads

HBCUs were established with the principal mission of educating African Americans; however, today they are diverse institutions that enroll students of many races. Café participants acknowledged that “HBCUs are teaching-intensive environments that typically require faculty to maintain high teaching and advising loads.” This level of teaching was considered to be a “significant barrier to building a research career,” creating challenges for

‘scheduling protected time for research.’ One participant noted that “my heavy course loads, large advising portfolio, serving on several dissertation committees and participation in departmental and university committees leaves little time for trying to maintain a research agenda.” Consensus across the three cafés was that a reduction in course load and committee responsibilities would serve as a motivation to focus on research.

Engaging Students in Research

The opportunity to introduce and engage students of color in research during their undergraduate years was noted as a facilitator to participate in scientific investigations at HBCUs. For example, one participant indicated “my teaching is enhanced by bringing my research into the classroom, which allows students to benefit,” and another said, “merging teaching and research interests make courses more robust for students and allows me to leverage the teaching mission to encourage students to pursue advanced degrees.”

Discussion

Café Findings and Emergence of OHD PRIDE Conceptual Framework

The goal of OHD PRIDE is to develop independent investigators with the requisite skills to publish scientific articles and submit a competitive grant application in one of the NHLBI focus areas within two years of completing the program. OHD PRIDE provides training experiences and mentorship to enhance research careers by sharing advice on study design, skills and methodologies, strategies to prepare research grants, and tips for success in obtaining external funding in research related to obesity and related health outcomes. In addition, OHD PRIDE provides a forum to discuss unique issues faced by researchers from underrepresented backgrounds in the conduct of research and obtaining extramural funding.

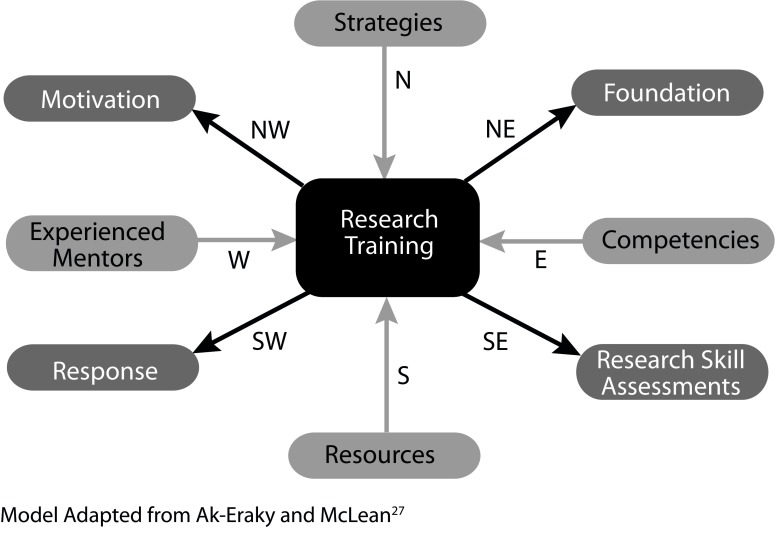

Comprehensive research training and mentoring programs designed for faculty from backgrounds underrepresented in biomedical research often lack social, economic, and behavioral considerations often provided by social science and education theories. Our approach and program activities are guided by a conceptual framework that draws on theories from multiple disciplines and is informed by the insights and experiences of conversation café participants. We have previously published a full description of the theoretical and conceptual underpinnings of OHD PRIDE.17 The OHD PRIDE curriculum is based on a modification of the Compass Model,27 (Figure 1) best practices in research training and mentoring, and grounded in the barriers identified in the conversation cafés to address the salient aspects of teaching-intensive institutions that can present challenges for building research careers.17 Table 2 illustrates examples of how findings were utilized to develop our research training and mentoring program.

Figure 1. Adapted Compass Model.

Table 2. Selected conversation café findings and application.

| Barriers to Developing Robust Research Careers | |

| Lack of access to research journals and databases | PRIDE mentees were given access to the library holdings at a research-intensive institution (UMMC) and access to mentor databases |

| Lack of mentors | Mentees assigned to primary and secondary OHD PRIDE mentors, and had direct access to any of the mentors and program faculty for support |

| Increased workload if involved in research; still responsible for full teaching load despite research commitments | Didactic and practical information regarding balancing and integrating research and teaching. Techniques for how to produce manuscripts leveraging the academic calendar.10 |

| Developing Successful Research Careers in Teaching-Intensive Environments | |

| The need for more protected writing time | Developed and incorporated a mid-year writing retreat and writing accountability groups during the academic year; included blocks of writing time during the summer institutes |

| Collaborate with a research accountability partner | Formed learning communities and encouraged the use of group apps (ie, Group Me and WhatsApp) to foster mentees’ interaction and peer support |

| Interest in research partnerships and support groups | Created opportunities for mentees to collaborate on manuscript development |

Conclusion

There is an urgent need to increase the quantity and quality of researchers from underrepresented groups working in areas of importance to minority health, such as obesity and obesity-related problems. Since scholars from underrepresented backgrounds conduct a significant amount of health disparities research in the United States, the lack of diversity of faculty in biomedical research is a major factor in the persistence of racial/ethnic health disparities. Scholars from underrepresented groups have unique insights into feasible approaches to studying and resolving health disparities, and are responsible for translating a substantial portion of research findings to the health care of communities of color.28 Expanding the pool of minority investigators is essential to reducing health disparities and accomplishing NIH’s goal of “translating and disseminating research findings into practice” in the area of obesity health disparities (NHLBI Strategic Plan; Goal 3).8

Acknowledgments

Human Subjects Statement. OHD PRIDE is a research training and mentoring program in which all participants provided informed consent. All procedures used in the evaluation component of this program were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the University of Mississippi Medical Center’s Institutional Review Board, consistent with US regulations and the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all participants in the study.

Funding. This research was supported by a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R25HL126145 – Beech and Norris) and a grant from National Institute on Aging (K02AG059140-Thorpe).

References

- 1. Kivimäki M, Kuosma E, Ferrie JE, et al. . Overweight, obesity, and risk of cardiometabolic multimorbidity: pooled analysis of individual-level data for 120 813 adults from 16 cohort studies from the USA and Europe. Lancet Public Health. 2017;2(6):e277-e285. 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30074-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hales CM, Fryar CD, Carroll MD, Freedman DS, Ogden CL. Trends in Obesity and Severe Obesity Prevalence in US Youth and Adults by Sex and Age, 2007-2008 to 2015-2016. JAMA. 2018;319(16):1723-1725. 10.1001/jama.2018.3060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Levi J, Segal LM, St Laurent R, Lang A, Rayburn J. F as in Fat: How Obesity Threatens America’s Future 2012. Washington, DC: Trust for America’s Health; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gregg EW, Shaw JE. Global health effects of overweight and obesity. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(1):80-81. 10.1056/NEJMe1706095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Afshin A, Forouzanfar MH, Reitsma MB, et al. ; GBD 2015 Obesity Collaborators . GBD 2015 Obesity Collaborators. Health effects of overweight and obesity in 195 countries over 25 years. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(1):13-27. 10.1056/NEJMoa1614362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Daniels R, Dzau V. Supporting the Next Generation of Biomedical Researchers. JAMA. 2018;320(1):29-30. 10.1001/jama.2018.7902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Valantine HA, Lund PK, Gammie AE. From the NIH: A systems approach to increasing the diversity of the biomedical research workforce. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2016;15(3):fe4. 10.1187/cbe.16-03-0138 10.1187/cbe.16-03-0138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. National Heart Lung and Blood Institute The NHLBI Stragegic Vision: Charting the Future Together. Vol 2017 Washington, DC: U. S. Department of Health and Human Service, National Institutes of Health; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mervis J. Mentoring’s moment. Science. 2016;353(6303):980-982. 10.1126/science.353.6303.980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tabak LA, Collins FS. Sociology. Weaving a richer tapestry in biomedical science. Science. 2011;333(6045):940-941. 10.1126/science.1211704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Baskerville L, Berger L, Smith L. The role of historically Black colleges and universities in faculty diversity. American Academic. 2011;4:11-31. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Brown MC, Ricard RB the honorable past and uncertain future of the nation’s HBCUs. NEA Higher Education Journal. 2007;Fall:117-130. Last accessed November 18, 2019 from http://beta.nsea-nv.org/assets/img/PubThoughtAndAction/TAA_07_12.pdf

- 13. Allen WR, Jewell JO. A backward glance forward: Past, present, and the future perspectives on HBCUs. The Review of Higher Education. 2002;25(3):241-261. 10.1353/rhe.2002.0007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee JM, Keys SW. Repositioning HBCUs for the future: Access, success, research and innovation. Washingon, DC: Association of Public and Land-grant Universities; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Roebuck JB, Murty KS. Historically Black Colleges and Universities: Their Place in American Higher Education. ERIC; 1993. Last accessed November 18, 2019 from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED363683

- 16. Waller LS, Shofoluwe MA. A qualitative case study of junior faculty mentoring practices at selected minority higher educational institutions. J Tech. Management & Applied Engineering. 2013;29(3):2-9. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Beech BM, Bruce MA, Thorpe RJ Jr, Heitman E, Griffith DM, Norris KC. Theory-informed research training and mentoring of underrepresented early-career faculty at teaching-intensive institutions: The Obesity Health Disparities PRIDE Program. Ethn Dis. 2018;28(2):115-122. 10.18865/ed.28.2.115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Clewell BC, deCohen CC, Tsui L. Capacity Building to Diversity STEM: Realized Potential among HBCUs. Washington, DC: National Science Foundation Urban Institute; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Anthony-Townsend N, Beech BM, Norris KC. Education and minority health professions in Historically Black Colleges and Universities. In: Boykin TF, Hilton AA, Palmer RT, eds. Professional education at historically Black colleges and universities: Past trends and future outcomes. New York: Routledge; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gasman M, Nguyen T-H Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs): leading our nation’s effort to improve the science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) pipeline. Texas Education Review. 2014;2(1):75-89. Last accessed November 18, 2019 from https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/handle/2152/45895

- 21. Bell JB. The need for effective research mentoring of early career STEM faculty at HBCUs. In: A Research Mentoring Guide for Early Career STEM faculty at HBCUs. Washington, DC: Quality Education for Minorities Network; 2016. Last accessed November 18, 2019 from https://static1.squarespace.com/static/57b5ee7d440243ac78571d0a/t/57bb27b35016e14742bafc25/1471883190911/PDM_MentoringGuide.pdf

- 22. Schiffer A, Isaacs D, Gyllenpalm B. The World Café: part One. Transformation (Durb). 2004;18(8):1-7. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Miles MB, Huberman AM. The qualitative researcher’s companion. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ginther DK, Schaffer WT, Schnell J, et al. . Race, ethnicity, and NIH research awards. Science. 2011;333(6045):1015-1019. 10.1126/science.1196783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Valantine HA, Serrano E; Advisory Committee to the Director . Working Group on Diversity in the Biomedical Research Workforce. Report on the Progress of Activities. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hoppe TA, Litovitz A, Willis KA, et al. . Topic choice contributes to the lower rate of NIH awards to African-American/black scientists. Sci Adv. 2019;5(10):eaaw7238. 10.1126/sciadv.aaw7238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Al-Eraky MM, McLean M. The Compass Model to plan faculty development programs. Medical Education Development. 2012;2(1):4 10.4081/med.2012.e4 10.4081/med.2012.e4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]