Abstract

Human-based modelling and simulations are becoming ubiquitous in biomedical science due to their ability to augment experimental and clinical investigations. Cardiac electrophysiology is one of the most advanced areas, with cardiac modelling and simulation being considered for virtual testing of pharmacological therapies and medical devices. Current models present inconsistencies with experimental data, which limit further progress. In this study, we present the design, development, calibration and independent validation of a human-based ventricular model (ToR-ORd) for simulations of electrophysiology and excitation-contraction coupling, from ionic to whole-organ dynamics, including the electrocardiogram. Validation based on substantial multiscale simulations supports the credibility of the ToR-ORd model under healthy and key disease conditions, as well as drug blockade. In addition, the process uncovers new theoretical insights into the biophysical properties of the L-type calcium current, which are critical for sodium and calcium dynamics. These insights enable the reformulation of L-type calcium current, as well as replacement of the hERG current model.

Research organism: Human

eLife digest

Decades of intensive experimental and clinical research have revealed much about how the human heart works. Though incomplete, this knowledge has been used to construct computer models that represent the activity of this organ as a whole, and of its individual chambers (the atria and ventricles), tissues and cells. Such models have been used to better understand life-threatening irregular heartbeats; they are also beginning to be used to guide decisions about the treatment of patients and the development of new drugs by the pharmaceutical industry.

Yet existing computer models of the electrical activity of the human heart are sometimes inconsistent with experimental data. This problem led Tomek et al. to try to create a new model that was consistent with established biophysical knowledge and experimental data for a wide range of conditions including disease and drug action.

Tomek et al. designed a strategy that explicitly separated the construction and validation of a model that could recreate the electrical activity of the ventricles in a human heart. This model was able to integrate and explain a wide range of properties of both healthy and diseased hearts, including their response to different drugs. The development of the model also uncovered and resolved theoretical inconsistencies that have been present in almost all models of the heart from the last 25 years. Tomek et al. hope that their new human heart model will enable more basic, translational and clinical research into a range of heart diseases and accelerate the development of new therapies.

Introduction

Human-based computer modelling and simulation are a fundamental asset of biomedical research. They augment experimental and clinical research through enabling detailed mechanistic and systematic investigations. Owing to a large body of research across biomedicine, their credibility has expanded beyond academia, with vigorous activity also in regulatory and industrial settings. Thus, human in silico clinical trials are now becoming a central paradigm, for example, in the development of medical therapies (Pappalardo et al., 2018). They exploit mature human-based modelling and simulation technology to perform virtual testing of pharmacological therapies or devices.

Human cardiac electrophysiology is one of the most advanced areas in physiological modelling and simulation. Current human models of cardiac electrophysiology include detailed information on the ionic processes underlying the action potential such as the sodium, potassium and calcium ionic currents, exchangers such as the Na/Ca exchanger and pumps such as the Na/K pump. They also include representation of the excitation-contraction coupling system in the sarcoplasmic reticulum, an important modulator of the calcium transient, through the calcium-induced calcium-release mechanisms and the SERCA pump. Several human models have been proposed for ventricular electrophysiology, and amongst them the ORd model (O'Hara et al., 2011). Its key strengths are the representation of CaMKII signalling, capability to manifest arrhythmia precursors such as alternans and early afterdepolarisation, and good response to simulated drug block and disease remodelling (Dutta et al., 2016; Dutta et al., 2017a; Passini et al., 2016; Tomek et al., 2017). Consequently, ORd was selected by a panel of experts as the model best suited for regulatory purposes (Dutta et al., 2017a).

Most of the ORd model development has focused on repolarisation properties such as its response to drug block, repolarisation abnormalities and its rate dependence. However, a more holistic comparison of ORd-based simulations with human ventricular experimental data reveals important inconsistencies. Firstly, the plateau of the action potential (AP) is significantly higher in the ORd model than in experimental data used for ORd model construction (O'Hara et al., 2011; Britton et al., 2017) and in data from additional studies using human cardiomyocytes (Coppini et al., 2013; Jost et al., 2013). Secondly, the dynamics of accommodation of the AP duration (APD) to heart rate acceleration, which are known to be modulated by sodium dynamics, show only limited agreement with a comparable experimental dataset (Franz et al., 1988; O'Hara et al., 2011). Thirdly, we identify that simulations of the sodium current block has an inotropic effect in the ORd model, increasing the amplitude of the calcium transient, in disagreement with its established negatively inotropic effect in experimental/clinical data (encainide, flecainide, and TTX) (Gottlieb et al., 1990; Tucker et al., 1982; Legrand et al., 1983; Bhattacharyya and Vassalle, 1982). All those properties, namely AP plateau potential, APD adaptation and response to sodium current block, have strong dependencies on sodium and calcium dynamics. We therefore hypothesise that ionic balances during repolarisation require further research. We specifically focus on an in-depth re-evaluation of the L-type calcium current (ICaL) formulation, given its fundamental role in determining the AP, the calcium transient and sodium homeostasis through the Na/Ca exchanger. The second main focus is the re-assessment of the rapid delayed rectifier current (IKr), the dominant repolarisation current in human ventricle, under conditions that reflect experimental data-driven plateau potentials.

Using a development strategy based on strictly separated model calibration and validation, we sought to design, develop, calibrate and validate a novel model of human ventricular electrophysiology and excitation contraction coupling, the ToR-ORd model (for Tomek, Rodriguez – following ORd). Our aim for simulations using the ToR-ORd model is to be able to reproduce all key depolarisation, repolarisation and calcium dynamics properties in healthy ventricular cardiomyocytes, under drug block, and in key diseased conditions such as hyperkalemia (central to acute myocardial ischemia), and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

Materials and methods

Strategy for construction, calibration and validation of the ToR-ORd model

Table 1 lists the properties (left column) and key references (right column) of experimental and clinical datasets considered for the calibration (top) and independent validation (bottom) of the ToR-ORd model. This represents a comprehensive list of properties, known to characterize human ventricular electrophysiology under multiple stimulation rates, and also drug action and disease. The recordings in were obtained in human ventricular preparations primarily using measurements with microelectrode recordings, unipolar electrograms, and monophasic APs, therefore avoiding photon scattering effects or potential dye artefacts present in optical mapping experiments. In addition, the ToR-ORd model was calibrated to manifest depolarisation of resting membrane potential in response to an IK1 block, based on evidence in a range of studies summarised in Dhamoon and Jalife (2005). The calibration criteria are chosen to be fundamental properties of ionic currents, action potential and single-cell pro-arrhythmic phenomena (described in more detail in Appendix 1-1). The validation criteria include response to rate changes, drug action and disease, to explore the predictive power of the model under clinically-relevant conditions.

Table 1. Criteria and human-based studies used in ToR-ORd calibration and validation.

| Calibration | |

|---|---|

| Action potential morphology | (Britton et al., 2017; Coppini et al., 2013; Jost et al., 2013) |

| Calcium transient time to peak, duration, and amplitude | (Coppini et al., 2013) |

| I-V relationship and steady-state inactivation of L-type calcium current | (Magyar et al., 2000) |

| Sodium blockade is negatively inotropic | (Gottlieb et al., 1990; Tucker et al., 1982; Legrand et al., 1983; Bhattacharyya and Vassalle, 1982). |

| L-type calcium current blockade shortens the action potential | (O'Hara et al., 2011) |

| Early depolarisation formation under hERG block | (Guo et al., 2011) |

| Alternans formation at rapid pacing | (Koller et al., 2005) |

| Conduction velocity of ca. 65 m/s | (Taggart et al., 2000) |

| Validation | |

| Action potential accommodation | (Franz et al., 1988) |

| S1-S2 restitution | (O'Hara et al., 2011) |

| Drug blocks and action potential duration | (Dutta et al., 2017a; O'Hara et al., 2011) |

| Hyperkalemia promotes postrepolarisation refractoriness | (Coronel et al., 2012) |

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy phenotype | (Coppini et al., 2013) |

| Drug safety prediction using populations of models | (Passini et al., 2017) |

| Physiological QRS and QT intervals in ECG | (Engblom et al., 2005; van Oosterom et al., 2000; Bousseljot et al., 1995; Goldberger et al., 2000) |

We initially performed the evaluation of the ORd model (O'Hara et al., 2011) by conducting simulations for each of the calibration criteria in Table 1. Further details are described throughout the Materials and methods section and Appendix 1-15.1. Simulations with the existing versions of the ORd model failed to fulfil key criteria such as AP morphology, calcium transient duration, several properties of the L-type calcium current, negative inotropic effect of sodium blockers, or the depolarising effect of IK1 block. The results are later demonstrated in Figures 2 and 3, and Methods: Calibration of IK1 block and resting membrane potential. Secondly, we attempted parameter optimisation using a multiobjective genetic algorithm (Torres et al., 2012). However, simulations with the ORd-based models were unable to fulfil key criteria such as AP and Ca morphology, and the effect of sodium and calcium block on calcium transient amplitude and APD, respectively.

We then proceeded to reevaluate the ionic current formulations based on experimental data and biophysical knowledge. Key currents included ICaL and specifically its driving force and activation, as well as the INa, IKr, IK1 and chloride currents. The multiobjective genetic algorithm optimisation was repeated several times, throughout the introduction of structural changes to the model. Once simulations with an optimised model fulfilled all calibration criteria, validation was conducted through evaluation against additional experimental recordings for drug block, disease, tissue and whole-ventricular simulations.

Details concerning the simulations are given in Appendix 1-15.1, namely the description of simulation protocols and ionic concentrations used (Appendix 1-15.1.1), representation of heart disease (Appendix 1-15.1.2), 1D fibre simulations (Appendix 1-15.1.3), population-of-models and drug safety assessment (Appendix 1-15.1.4), transmurality and whole-heart simulations with ECG extraction (Appendix 1-15.1.5), and a technical note on the update to the Matlab ODE solver which facilitates efficient simulation of the multiobjective GA (Appendix 1-15.1.6). Unless specified otherwise, the baseline ORd model (O'Hara et al., 2011) was used for comparison with the ToR-ORd model.

ToR-ORd model structure

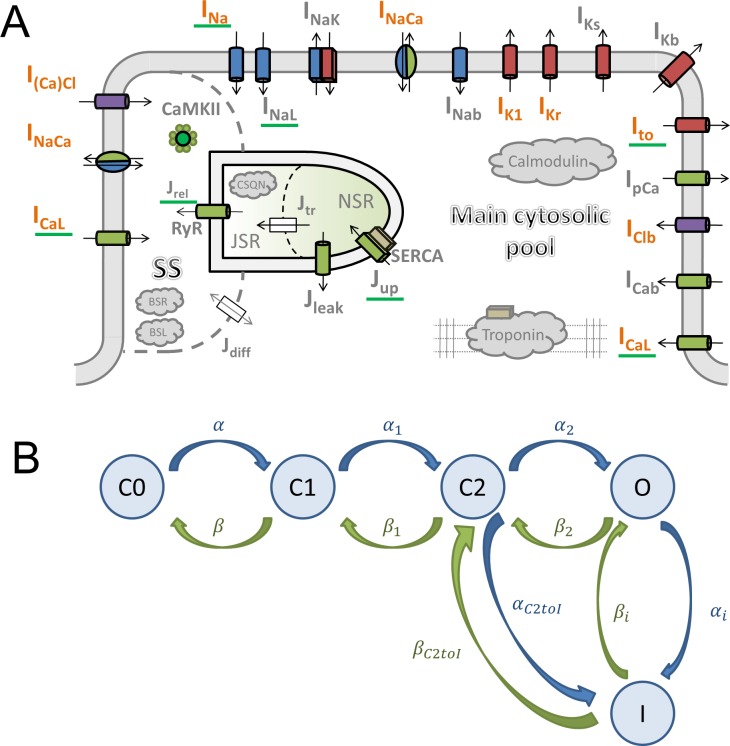

The ToR-ORd model follows the general ORd structure (Figure 1A). The cardiomyocyte is subdivided into several compartments: main cytosolic space, junctional subspace, and the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR, further subdivided into junctional and network SR). Within these compartments are placed ionic currents and fluxes described by Hodgkin-Huxley equations or Markov models. The main ionic current formulations altered compared to ORd are highlighted in orange in Figure 1A.

Figure 1. Model structure.

(A) A schematic of the novel human ventricular myocyte model for electrophysiology and calcium handling. Orange indicates components, substituted, or added, compared to the original ORd model. ‘SS’ indicates junctional subspace compartment, where calcium influx via L-type calcium current occurs and where calcium is released from the sarcoplasmic reticulum. ‘JSR’ and ‘NSR’ are junctional and network sarcoplasmic reticulum compartments, respectively. ‘Main cytosolic pool’ is the remaining intracellular space. Transmembrane currents are indicated with an ‘I’ in their name, with fluxes indicated as ‘J’. Components with a green underscore are modulated by CaMKII signalling. (B) The structure of the Lu-Vandenberg (Lu et al., 2001) Markov model used for the rapidly activating delayed rectifier repolarisation current (IKr). The transition rates are given in Appendix 1-15.3.5.

In-depth revision of the L-type calcium current

The ICaL current was deeply revisited, particularly with respect to its driving force, based on biophysical principles. This reformulation is of relevance to almost all models of cardiac electrophysiology.

The ICaL formulation in the ORd model is based on Hodgkin-Huxley equations, with the total current being a product of three components: 1) Open channel permeability, 2) A set of gating variables determining the fraction of channels being open, 3) The electrochemical driving force which acts on ions to move through the open channel based on the membrane potential and ionic concentrations on both sides of the membrane (more details in Appendix 1-5). In most Hodgkin-Huxley models of cardia currents, the driving force is computed as (V-Eion), that is, the membrane potential minus equilibrium potential, either computed from the Nernst equation, or measured experimentally. However, starting with the Luo-Rudy model (LRd) of 1994 (Luo and Rudy, 1994), the driving force of ions via ICaL in cardiac models is modelled based on the Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz (GHK) flux equation. The driving force based on the GHK equation is:

where z is the charge of the given ion, V is the membrane potential, F,R,T are conventional thermodynamic constants, and [S]i, [S]o are intracellular and extracellular activities of the given ionic specie. , where is the ionic activity coefficient and the concentration (in either the intracellular or extracellular space, yielding or ).

Determining ionic activity coefficients

In order to compute the ionic driving force via the GHK equation, it is necessary to know the ionic activity coefficients of the intracellular (γi) and extracellular (γo) space. The Luo-Rudy model and other Rudy-family models use γo = 0.341 for extracellular space and γi = 1 for the intracellular space. Models based on the Shannon model (Shannon et al., 2004) use 0.341 for both intracellular and extracellular space, but we were unable to find the motivation for this change.

The Debye-Hückel theory is commonly used to compute the activity coefficients. We used the Davies equation, which extends the basic Debye-Hückel equation to be accurate for ionic concentrations found in living cells (Mortimer, 2008):

where A is a constant (~0.5 for water at 25°C, ~0.5238 at 37°C), zi is the charge of the respective ion, and I is the ionic strength of the solution. The ionic strength is defined as:

where mi is the concentration of the i-th ionic specie present. For concentrations in a study measuring properties of ICaL (Magyar et al., 2000), I is ca. 0.15-0.17. This warrants the use of Davies equation, which was shown to be accurate for I up to 0.5, unlike the basic Debye-Hückel equation, which is accurate for I up to 0.01 only (Mortimer, 2008).

We implemented the computation of ionic coefficients based on the Davies equation dynamically, so that the activity coefficients are estimated at every simulation step. This allows accurate representation of the driving force when ionic concentrations are disturbed, such as at varying pacing rates, or during homeostatic imbalance. The dynamic computation is also used to estimate ionic activity coefficients for potassium and sodium flowing through the calcium channels, taking into account their different charge.

Throughout our simulations, both intracellular and extracellular activity coefficients generally lie between 0.61 and 0.66. Importantly, this estimate shows that the intracellular and extracellular activity coefficients are relatively similar (corresponding to the broadly similar total concentration of charged molecules), in contrast with the original values. Particularly, the origin of the intracellular activity coefficient γi = 1 in the Luo-Rudy model is unclear, as by the Davies (or by any Debye-Hückel variant) equation, I would have to be zero, which is possible only when there are no ions present.

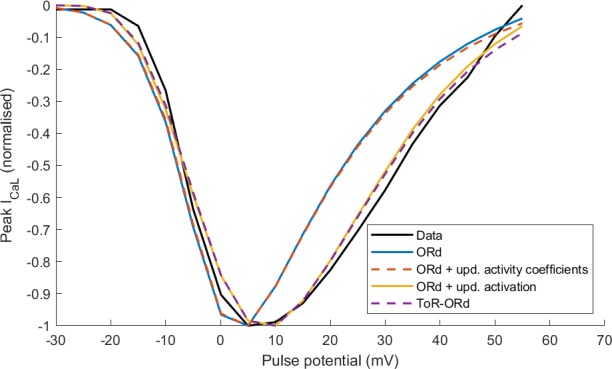

Activation curve extraction

An additional improvement in the ICaL formulation is the estimation of its activation curve. In brief, we implement a consistent use of the GHK equation for the extraction of the activation curve and for the ICaL formulation in the ToR-ORd model. The activation curve is obtained via dividing the experimentally measured I-V relationship of the current by the expected driving force for each pulse potential (see Appendix 1-3 for a graphical overview of the process). However, we identified a theoretical inconsistency in previous cardiac models across species (e.g. Luo and Rudy, 1994; Hund et al., 2008; O'Hara et al., 2011; Shannon et al., 2004; Grandi et al., 2010; Carro et al., 2011): whereas the Nernstian driving force of (V-ECa) is used to derive the activation curve, the GHK driving force is then used to calculate ICaL. Indeed, experimental studies reporting the activation curve of ICaL generally use the Nernstian driving force of (V-ECa) with ECa being the experimentally measured reversal potential of approximately 60 mV. This is explicitly stated in Linz and Meyer (2000), and also the activation curve by Magyar et al. (2000) used in the ORd model is consistent with dividing the IV relationship with (V-60).

In this study, we propose that, for consistency, the same equation needs to be applied both to obtain the activation curve from the I-V curve and to represent the driving force in the current formulation. Thus, in the ToR-ORd model, the activation curve for ICaL was obtained by dividing the I-V curve from Magyar et al. (2000) by the GHK-based driving force, computed using ionic activity coefficients based on the Davies equation (as explained in the previous Section) and intracellular and extracellular ionic concentrations as in Magyar et al. (2000). The following capped Gompertz function (a flexible sigmoid) was found to be the best fit to the resulting steady-state activation curve:

where V is the membrane potential.

Other ICaL changes

20% of ICaL was placed in the main cytosolic space, consistent with the literature (Scriven et al., 2010). This increases the plateau-supporting capability of ICaL, given that the myoplasmic ICaL is subject to a weaker calcium-dependent inactivation than ICaL in the junctional subspace. Other minor changes are given in Appendix 1-15.3.3.

IKr replacement

The calibration of the ToR-ORd model’s AP morphology to experimental data resulted in problematic response to calcium blockade during an early phase of the model development when the original IKr formulation was used (further details in Appendix 1-12). ICaL block is known to shorten APD experimentally (O'Hara et al., 2011) but resulted in a major APD prolongation in simulations instead. This discrepancy could not be resolved through parameter optimisation. A mechanistic analysis revealed that this follows from the lack of ORd IKr activation, which is however not consistent with relevant experimental data (Lu et al., 2001). We therefore considered alternative IKr formulations and specifically the Lu-Vandenberg (Lu et al., 2001) Markov model (Figure 1B). The Lu-Vandenberg IKr model is based on extensive experimental data allowing the dissection of activation and recovery from inactivation and provided the best agreement with experimental data, specifically when considering the AP plateau potentials reported experimentally. In Appendix 1-12, we: (1) provide a detailed explanation of origins of AP prolongation following ICaL block in a model which manifests experimental data-like plateau potentials and which contains the ORd IKr formulation; (2) explain why this phenomenon occurs only in a model with experimental data-like plateau potentials, but not in the original high-plateau ORd model; (3) compare the ORd and Lu-Vandenberg IKr formulations with experimental data, demonstrating the good agreement with experimental data of the Lu-Vandenberg formulation but not the ORd.

Following the inclusion of the Lu-Vandenberg IKr formulation, all models generated during model calibration exhibited APD shortening in response to ICaL block.

Changes in INa, I(Ca)Cl, IClb and IK1

The INa current formulation was replaced by an alternative human-based formulation (Grandi et al., 2010), given established limitations of the original model with regards to conduction velocity and excitability (O'Hara et al., 2011), comment on article from 05 Oct 2012). The Grandi INa model was updated to account for CaMKII phosphorylation (Appendix 1-15.3.1).

Also from the Grandi model, we added the calcium-sensitive chloride current I(Ca)Cl and background chloride current IClb formulation (Grandi et al., 2010). Neither model was changed compared to the original formulations, but the intracellular concentration of Cl- was slightly increased (Appendix 1-15.1.1). In accordance with recent observations, I(Ca)Cl was placed in the junctional subspace (Magyar et al., 2017). The motivation to add these currents was to facilitate the shaping of post-peak AP morphology (via I(Ca)Cl), with IClb playing a dual role stemming from its reversal potential of ca. −50 mV. It slightly reduces plateau potentials during the action potential, but during the diastole, it depolarises the cell slightly, improving the reaction to IK1 block as explained in the next subsection.

The IK1 model was replaced with the human-based formulation by Carro et al. (2011), as it was shown to be key for simulations of hyperkalemic conditions. The IK1 replacement was done before hyperkalemia simulation, not violating the classification of hyperkalemia criterion as a validation step. Extracellular potassium concentration in a healthy cell was reduced from 5.4 to 5 mM to fall within the physiological range (Zacchia et al., 2016).

Calibration of IK1 block and resting membrane potential

When evaluating the baseline ORd model against the selected criteria, we observed that a reduction in IK1 results in hyperpolarisation of the cell (from −88 to −88.16 mV at 1 Hz pacing). However, it is established that IK1 reduction depolarises cells experimentally (Dhamoon and Jalife, 2005). Changes made during ToR-ORd calibration (predominantly the altered balance of currents during diastole and the inclusion of background chloride current) result in ToR-ORd manifesting depolarization in response to IK1 block, consistent with experimental data.

Multiobjective genetic algorithm

We applied a multiobjective genetic algorithm (MGA, @gamultiobj function in Matlab, Deb, 2001) to automatically re-fit various model parameters. Based on preliminary experimentation, we used a two-dimensional fitness. We used MGA rather than an ordinary genetic algorithm or particle swarm optimisation, given that MGA optimises towards a Pareto front rather than a single optimum, implicitly maintaining population diversity. The Pareto front is the set of all creatures which are not dominated by any other creature in the population, that is creatures for which there is no other creature better in all fitness dimensions. Therefore, a subpopulation of diverse solutions is maintained, and the optimiser consequently has less of a tendency to converge to a single local optimum compared to single-number fitness approaches. In addition, the crossover operator of GA is well suited for a task where multiple criteria are optimised, given that creatures in the population may efficiently share partial solutions to various subcriteria. The fitness used in this study is described in greater detail in Appendix 1-1.

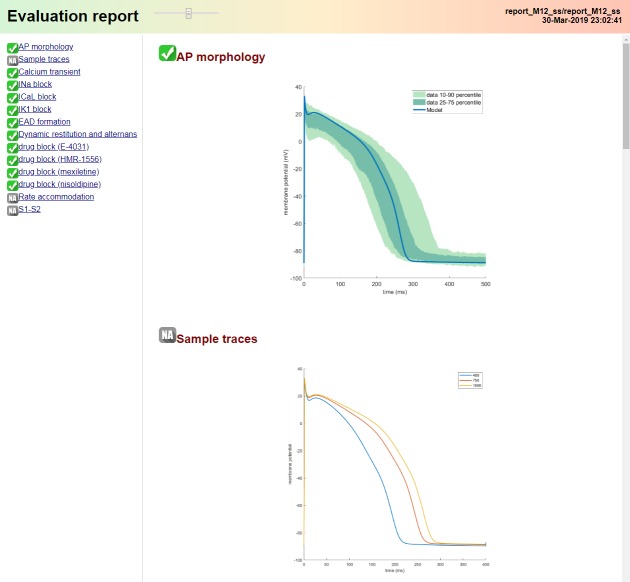

Evaluation pipeline and code

To facilitate the model validation and future work, we also provide an automated ‘single-click’ evaluation pipeline. It runs automatic simulations to extract and visualise single-cell biomarkers including those related to AP morphology, effect of key channel blockers, early afterdepolarisations (EAD), and alternans measurement. The pipeline generates a single HTML report containing all the results; see Appendix 1-15.2 for a visualisation. The code for our model (Matlab and CellML), the validation pipeline, and the experimental data on human AP morphology are available at https://github.com/jtmff/torord (Tomek, 2019; copy archived at https://github.com/elifesciences-publications/torord). An informal blog giving further insight into the choices we made, as well as general thoughts on the development of ToR-ORd and computer models in general, is available at https://underlid.blogspot.com/.

We designed the Matlab code used to simulate our model so that the simulation core is structured into functions computing currents, making the high-level organisation of code clear, and facilitating inclusion of alternative current formulations. In addition, a CellML file encoding our model is also provided. This makes the model readily runnable in several simulators in addition to Matlab (e.g. Chaste [Pitt-Francis et al., 2009] and OpenCOR [Garny and Hunter, 2015]). Furthermore, the Myokit library (Clerx et al., 2016) enables conversion of the CellML file to other languages (such as C or Python).

Results

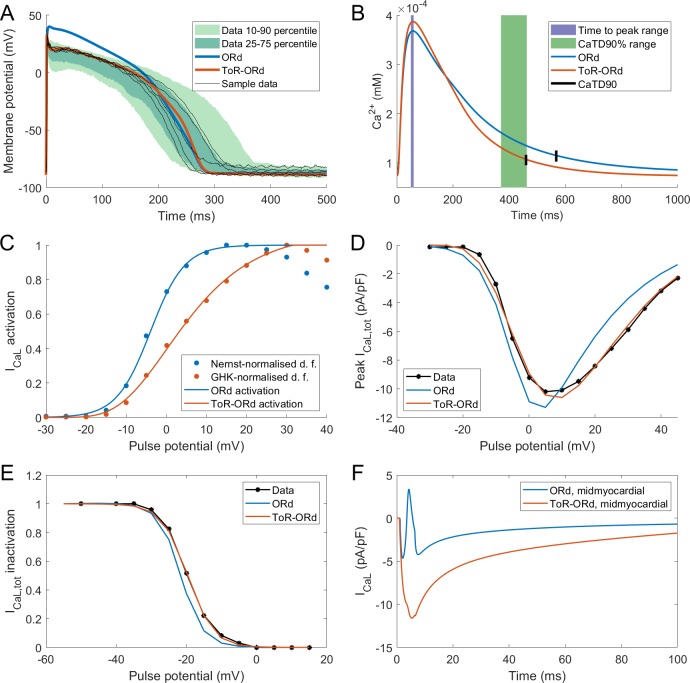

Calibration based on AP, calcium transient, and L-type calcium current properties

The AP morphology of the ToR-ORd is within or at the border of the interquartile range of the Szeged-ORd experimental data (Figure 2A). This is a major improvement compared to the original ORd morphology, which overestimates plateau potentials, particularly during early plateau (Figure 2A). The fact that the early plateau potential is around 20–23 mV is clearly apparent from experimental recordings and is further corroborated by additional studies in human tissue samples (Jost et al., 2013, Figure 6) and isolated human cardiomyocytes (Coppini et al., 2013). We note that compared to the Szeged-ORd dataset (Britton et al., 2017), our model manifests a slightly increased peak membrane potential in the single-cell form, similar to single-cell experimental data (Coppini et al., 2013). This is a design choice related to the fact that the Szeged-ORd dataset contains recordings of small tissue samples, which are expected to manifest a reduced peak potential compared to single-cell. When coupled in a fibre, ToR-ORd manifests conduction velocity of 65 cm/s, which is consistent with clinical data (Taggart et al., 2000).

Figure 2. Action potential, calcium transient, and ICaL in ToR-ORd.

Action potential (A) and calcium transient (B) at 1 Hz obtained with the ToR-ORd model following calibration, compared to those obtained with the ORd model and experimental data from O'Hara et al. (2011) and Coppini et al. (2013), respectively. The purple and green zones in (B) stand for mean ± standard deviation. The duration of calcium transient at 90% recovery was extracted from figures in Coppini et al. (2013), adding the time to peak and time from peak to 90% recovery. (C) Activation curves used in the ToR-ORd and ORd models (blue and red lines, respectively). The points correspond to the IV relationship measured in Magyar et al. (2000) normalised by the Nernstian driving force (d.f.) assuming reversal potential of +60 mV (blue points) and the GHK driving force (red points). (D, E) I-V relationship and steady-state inactivation as measured in ToR-ORd (red line) versus ORd model (blue line) versus experimental data from Magyar et al. (2000) (black points with line). ICaL,tot is the sum of currents corresponding to all ions (Ca2+, Na+, and K+) passing through the L-type calcium current channels. (F) L-type calcium current of a midmyocardial cell, showing current reversal in ORd, but not in ToR-ORd. Only the calcium component of ICaL,tot is shown to demonstrate that the current reversal is not due to other ions. We note that the difference in total amplitude of ICaLin Figure 2F follows predominantly from different action potential shape in ToR-ORd vs ORd, consistent with the I-V relationship.

Both time to peak calcium and duration of calcium transient at 90% recovery obtained with the ToR-ORd model are within the standard deviation of experimental data in isolated human myocytes (Coppini et al., 2013), whereas ORd slightly overestimated the calcium transient duration (Figure 2B). The calcium transient amplitude of ToR-ORd also matches the Coppini et al. data after accounting for the different APD (Appendix 1-8).

As described in Materials and methods, the ToR-ORd ICaL activation curve was extracted from experimental data, using the Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz formulation of ionic driving force, ensuring theoretical consistency, unlike the ORd ICaL formulation (Figure 2C). This considerably improves the results of simulated protocols to obtain IV relationship (Figure 2D), validating the theory-driven changes (see Appendix 1-4 for the demonstration of how the updated activation curve underlies the improvement). The simulation of the protocol measuring steady-state inactivation also reveals improved agreement of ToR-ORd with experimental data compared to ORd (Figure 2E). The difference between measured ORd steady state inactivation and the experimental data (ca. two times stronger inactivation at around −15 mV, which is relevant for EAD formation) is initially surprising, given that the equation of ORd ICaL steady-state inactivation curve provides a good fit to the same experimental data. This difference follows from the formulation of calcium-dependent inactivation of ICaL (see Appendix 1-5 for details).

We observed that in cases of elevated ICaL (e.g. in midmyocardial cells), ORd reverses current direction towards positive values, which is an unexpected behaviour given its reversal potential of 60 mV. Conversely, the ToR-ORd model yields negative ICaL values in such conditions, consistent with it being an inward current (Figure 2F). This is a direct consequence of the updates to the extracellular/intracellular calcium activity coefficients (as explained in Appendix 1-6), which supports their credibility and it is important for cases of elevated ICaL, such as under ß-adrenergic stimulation.

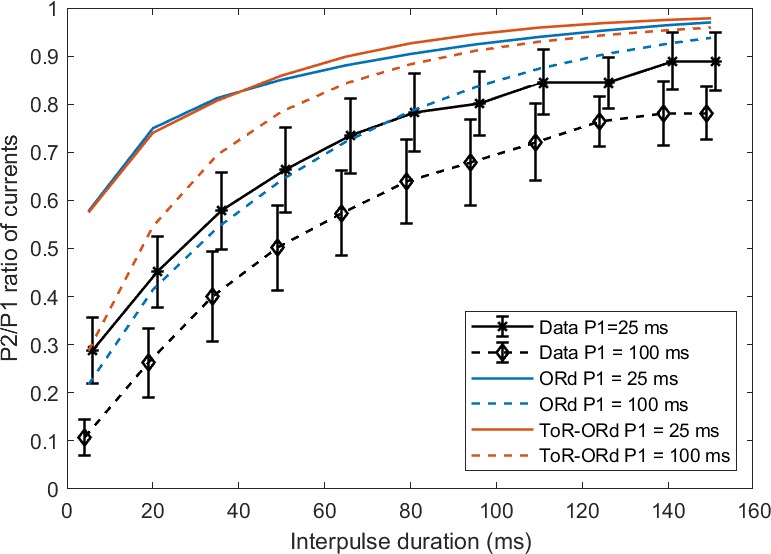

We have also simulated a P2/P1 protocol as measured experimentally by Fülöp et al. (2004), where two rectangular pulses are applied with varying interval between them. Both ORd and ToR-ORd qualitatively agree with the experimental data (Appendix 1-7).

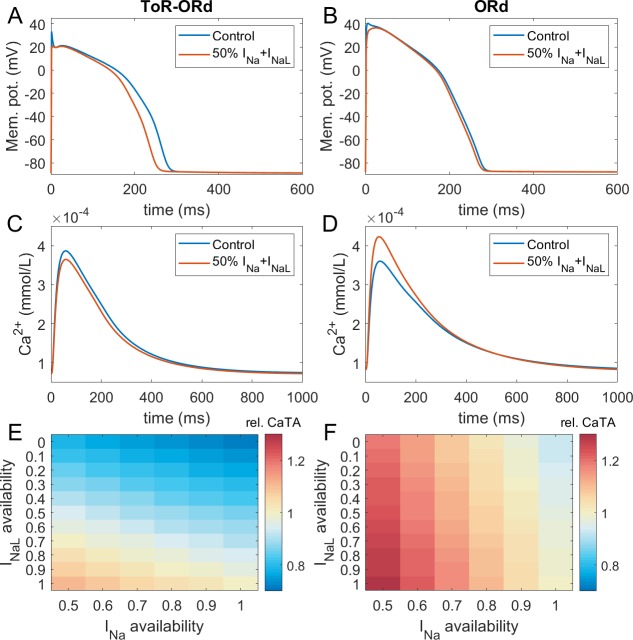

Calibration: inotropic effects of sodium blockers

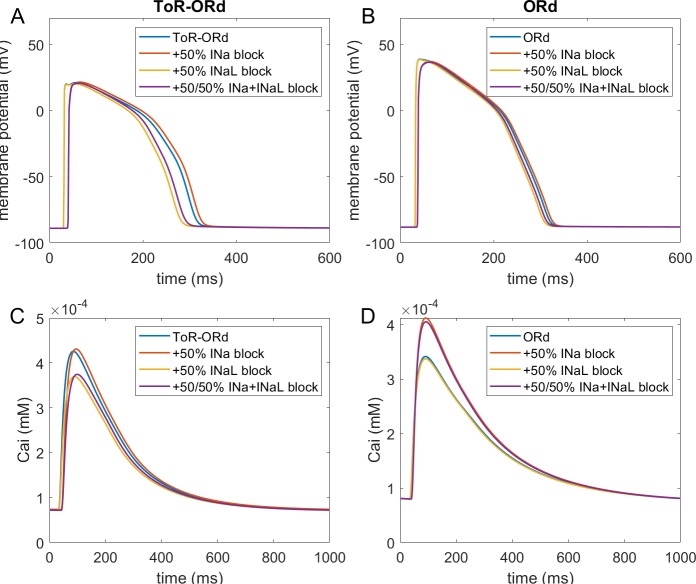

Figure 3A-D illustrates AP and calcium transient changes caused by block of sodium currents in ToR-ORd (left) and ORd (right). As sodium blockers act on channel Nav1.5 mediating both the fast (INa) and late (INaL) sodium current (Makielski, 2016), we simulate the effect of combined partial INa and INaL block. The ToR-ORd model manifests a small reduction in calcium transient amplitude (Figure 3C), unlike ORd, which gives a sizeable increase (Figure 3D); ToR-ORd is thus consistent with the observed negative inotropy of sodium blockers (Gottlieb et al., 1990; Tucker et al., 1982; Legrand et al., 1983; Bhattacharyya and Vassalle, 1982). This is a major improvement in the ToR-ORd model, as sodium current reduction is involved in a range of disease conditions in addition to pharmacological block.

Figure 3. Sodium blockade in ToR-ORd and ORd.

Simulated effect of sodium current block on the action potential (A, B) and calcium transient (C,D) using the ToR-ORd (left) and ORd (right) models. Control simulations are shown as blue traces, whereas results for 50% block of INa and INaL are shown as red traces. Panels (E,F) show values of changes in calcium transient amplitude with respect to control (‘rel. CaTA’) for varying degrees of INa/INaL block for ToR-ORd and ORd respectively (one is no change, values > 1 correspond to an increase the calcium transient amplitude).

Experimental evidence shows that the ratio of INa and INaL block is drug and dose-dependent, with INaL usually being blocked more than INa (Appendix 1-9). Figure 3E,F illustrates the change in calcium transient amplitude obtained with the ToR-ORd and ORd models, respectively, for several combinations of INa and INaL availability. Both models show a similar general trend where reduced INa availability increases calcium transient amplitude and reduced INaL availability diminishes it; however, the models differ strongly in relative contributions of these components. The ToR-ORd model shows negative inotropy for almost all combinations of blocks. A mild increase in inotropy may be achieved only under near-exclusive INa block. Conversely, ORd shows a general tendency for increased calcium transient amplitude; a reduction occurs only when the sodium current block targets near-exclusively INaL. ToR-ORd presents a greater calcium transient amplitude reduction than ORd in response to INaL block, as the current has a greater role in indirect modulation the cell’s calcium loading via APD change. At the same time, ToR-ORd shows a much smaller calcium transient amplitude increase in response to INa block than ORd because of the updated ICaL activation curve (Figure 2C), as well as closer-to experimental data AP morphology (Figure 2A) and its effect on ICaL. A detailed explanation is given in Appendix 1-10.

Fibre simulations carried out to assess the effect of cell coupling on the effect of sodium block are consistent with the single-cell simulations (Appendix 1-11). The difference in response to half-block of INa and INaL between ToR-ORd and ORd is even larger, as ToR-ORd in fibre predicts a greater reduction in calcium transient amplitude than in single cell (−14% vs −6% respectively), while ORd in fibre predicts a slightly greater increase in calcium transient amplitude than in single cell (+25% vs +24%).

With the ToR-ORd model, the 14% reduction in CaT amplitude in the electrically coupled fibre with 50% block of both INa and INaL is generally consistent with clinical data on sodium blockers: Encainide reduced stroke work index by 15% and cardiac index by 8% (Tucker et al., 1982). In another study using encainide, the cardiac index was reduced by 18% and the stroke volume index by 28% (Gottlieb et al., 1990). Flecainide reduced left ventricular stroke index by 12% and the left ventricular ejection fraction by 9% (Legrand et al., 1983). Simulations with the ToR-ORd model show overall agreement with the clinical data. However, a direct quantitative comparison is challenging given the different indices of contractility measured (CaT amplitude versus clinical indices) and that it is not possible to estimate the exact ratios of INa and INaL block in clinical data (Appendix 1-9).

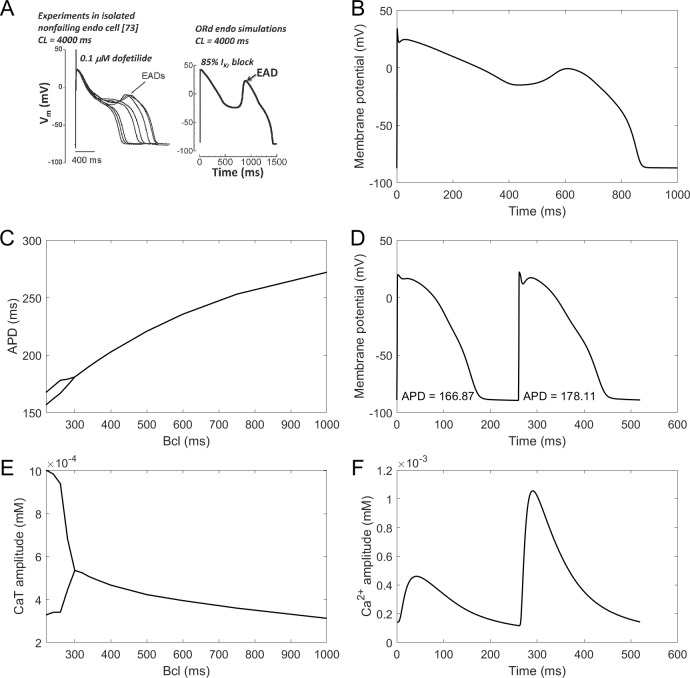

Calibration: proarrhythmic behaviours (alternans and early afterdepolarisations)

EADs are an important precursor to arrhythmia, manifesting as a membrane potential depolarisation during late plateau and/or early repolarisation. They are thought to arise mainly from ICaL current reactivation (Weiss et al., 2010). The ToR-ORd model manifests EADs at conditions used experimentally in nondiseased human endocardium (Guo et al., 2011; Figure 4A). The amplitude of simulated EADs is 14 mV (Figure 4B), which matches the maximum EAD amplitude shown by Guo et al. (2011). We also note that the experimental data by Guo et al. manifest early plateau potential of ca. 23 mV (which is matched by ToR-ORd), in line with other studies we referred to previously regarding this matter.

Figure 4. EADs and alternans.

(A) Experimentally observed EADs produced in nondiseased human myocytes exposed to 0.1 µM dofetilide (∼85% IKr block) paced at 0.25 Hz (Guo et al., 2011) and the corresponding simulation using the ORd model (O'Hara et al., 2011), figure reproduced as allowed by the CC-BY license). See Appendix 1-15.1.1 for ionic concentrations used. (B) An EAD produced by the ToR-ORd model at the same conditions. (C,E) APD and calcium transient amplitude versus pacing base cycle length (bcl); the bifurcation indicates alternans. (D,F) Example of APD and calcium transient alternans at the bcl of 260 ms.

Repolarisation alternans is another established precursor to arrhythmia, facilitating the formation of conduction block (Weiss et al., 2006). It is induced by rapid pacing and it is mostly thought to arise from calcium transient amplitude oscillations being translated to APD oscillations (Pruvot et al., 2004), although purely voltage-driven mechanism was also proposed (Nolasco and Dahlen, 1968). Alternans in the ToR-ORd model is calcium-driven and appears via the same mechanism as in the ORd: sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium cycling refractoriness (Tomek et al., 2018). It occurs at rapid pacing, in both calcium and APD (Figure 4C–F). The peak APD alternans amplitude (difference in APD between consecutive beats) is 12 ms, which is matches the value 11 ± 2 ms reported in human hearts without a structural disease (Koller et al., 2005). Direct quantitative comparison is however slightly limited by the fact that the data were recorded in RV septum, which may or may not differ from endocardial cells in alternans amplitude.

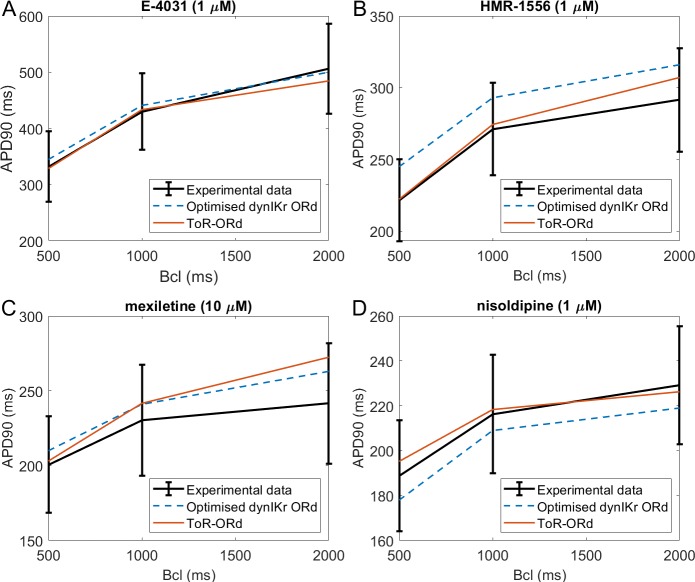

Validation: drug-induced effects on rate dependence of APD

Figure 5 illustrates simulations of drug action using the ToR-ORd model (red traces), compared to experimental data (black traces) and to simulations with the ORd model reparametrised by Dutta et al. (2017a) (blue dashed lines). APD is shown in the presence of IKr block (E-4031, Figure 5A), IKs block (HMR-1556 Figure 5B), multichannel block of INaL, ICaL, IKr (mexiletine, Figure 5C), and a ICaL block (nisoldipine, Figure 5D), at base cycle lengths of 500, 1000, and 2000 ms. We note that while the Dutta et al. model was specifically optimised for response of APD to these drug blocks, no such treatment was applied to the ToR-ORd model, making the results presented here an independent validation. Appendix 1-13 contains further details on the choice and use of the drug data.

Figure 5. Drug block and APD.

All four panels contain mean and standard deviation of experimental data (black) as measured in O'Hara et al. (2011) for three basic cycle lengths (bcl), predictions of the Dutta optimised dynamic-IKr ORd model (blue, Dutta et al., 2017a), and the predictions of the ToR-ORd model (red). (A) 1 µM E-4031 (70% IKr block). (B) 1 µM HMR-1556 (90% IKs block). (C) 10 µM mexiletine (54% INaL, 9% IKr, 20% ICaL block). (D) 1 µM nisoldipine (90% ICaL block). Drug concentrations and their effects on channel blocks are based on Dutta et al. (2017b).

The predictions produced by the ToR-ORd model are in good agreement with experimental data, particularly given the lack of optimisation towards this result. Simulating E-4031, ToR-ORd provides a prediction similar to the experimental data mean and the Dutta model (Figure 5A). This is crucial, given the key role of IKr in the repolarisation reserve of human cardiomyocytes. The response to IKs blockade via HMR-1556 is even better in ToR-ORd than in the Dutta model, which is also within standard deviation of the data, but carries a clear trend towards AP prolongation (Figure 5B). When simulating the multichannel blocker mexiletine, ToR-ORd prediction is within standard deviation of the experimental data, with the Dutta model giving similar or closer-to-mean predictions at 0.5 and 1 Hz (Figure 5C). The predicted effect of the calcium blocker nisoldipine in the ToR-ORd model matches well the experimental data mean (Figure 5D), even better than the Dutta model (also within standard deviation). We note that the good performance of the simulated nisoldipine effect critically relies on the IKr replacement (Materials and methods and Appendix 1-12).

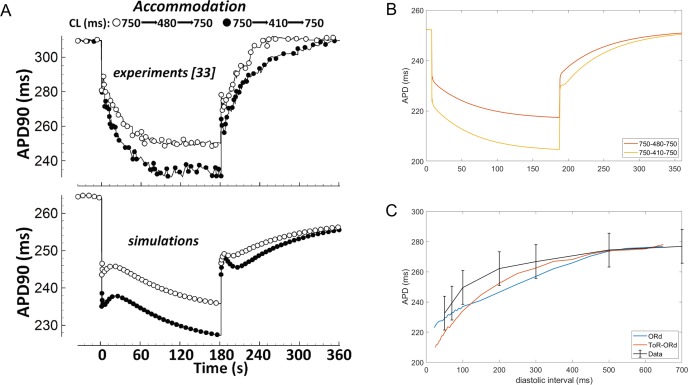

Validation: APD accommodation and S1-S2 restitution

Experimental measurements in human cardiomyocytes (Franz et al., 1988; Bueno-Orovio et al., 2012) show how the APD shortens upon increase in pacing frequency, and then prolongs again, as the pacing frequency returns to control (Figure 6A, top). APD adaptation dynamics with changes in heart rate are regulated by changes in sodium homeostasis (Pueyo et al., 2011), and their manifestation in QT adaptation have been shown to be useful for arrhythmia risk prediction (Pueyo et al., 2004). While simulations with the ORd model capture the general trend of APD accommodation, there are differences compared to the experimental data (Figure 6A). First, changes in pacing rate are followed by slow-dynamics (~30 s) APD prolongation not present in the experimental recordings. Second, the time constant of accommodation is generally slow. Conversely, the ToR-ORd model reproduces the pattern of accommodation well, where the change in APD soon after change in frequency is relatively fast, and then gradually slows down (Figure 6B). This suggests that the ionic balance in ToR-ORd is likely to have been improved compared to ORd.

Figure 6. APD accommodation and S1-S2 protocol.

(A) APD accommodation measured experimentally (Franz et al., 1988) and in simulation of the ORd model (reproduced as allowed by the CC-BY licence from O'Hara et al., 2011). (B) APD accommodation in ToR-ORd. (C) S1-S2 restitution curve (S1 = 1000 ms) in ToR-ORd fibre, ORd fibre (including INa modification to facilitate propagation Passini et al., 2016) and human tissue samples data (O'Hara et al., 2011).

A second indicator of how a model responds to a change in pacing frequency is the S1-S2 restitution protocol. The S1-S2 restitution curve obtained with the ToR-ORd model is given in Figure (Figure 6C), showing a good agreement with the experimental data (O'Hara et al., 2011).

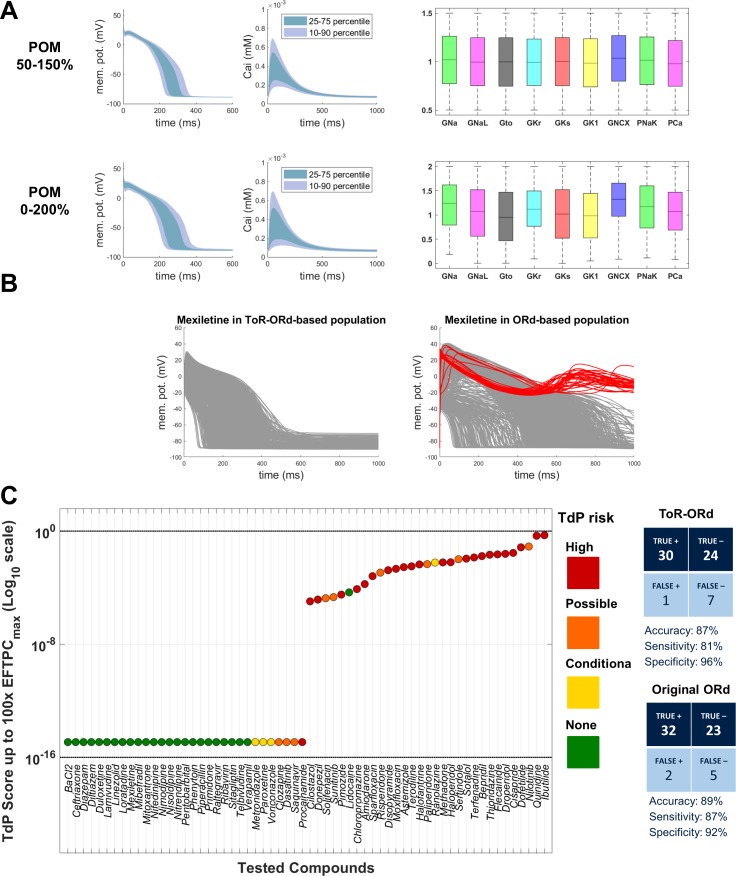

Validation: populations of models and drug safety prediction

Drug safety testing is one of the key applications of computer modelling which has yielded highly promising results (Passini et al., 2017). To assess the suitability of ToR-ORd for drug safety testing, we replicated the study by Passini et al. (2017), which was carried out using populations of models based on the ORd model. Two populations were created based on ToR-ORd similarly to the original study, altering conductances of important currents within the ranges of 50–150% and 0–200%. Models in both populations are stable under significant perturbation of ionic conductances, which supports the robustness of the model (Figure 7A).

Figure 7. Populations of models and drug safety prediction.

(A) Percentile-based summary of AP and calcium transient traces for the two populations of human ToR-ORd models (left side) and distribution of ionic current conductances among models in the population (right side), in the ranges [50-150]% (top row) and [0–200]% (bottom row) of the baseline values. (B) A comparison of 0–200% populations based on ToR-ORd (left) and ORd (right, based on Passini et al., 2017) in response to high-dose mexiletine (100-fold effective therapeutic dose). Traces classified as EADs are plotted in red (manifesting only in the ORd population). (C) TdP score obtained for simulations of the 62 reference compounds, based on the occurrence of drug-induced repolarisation abnormalities at all tested concentrations in the [0–200]% population of ToR-ORd models. The colours associated with drugs signify their established torsadogenicity as specified in Appendix 1-15.1.4. The logarithmic scale was considered to maximise the visual separation between safe and risky drugs. The classification based on the TdP score is summarised as a confusion matrix on the right, and also compared with the corresponding results obtained in a population of models based on the original ORd model (Passini et al., 2017).

Prediction of the risk of drug-induced Torsades de Pointes based on simulated drug-induced repolarisation abnormalities using ToR-ORd population yielded similar results to the original study, with predicted risk being correct for 54 out of 62 compounds (87% accuracy). Compared to Passini et al. (2017), the assessment of Mexiletine (a predominantly sodium blocker that is safe) was improved from false positive to true negative. High-dose Mexiletine led to formation of many EADs in ORd, but not in ToR-ORd (Figure 7B), highlighting the importance of the advances on sodium blockers presented in this work. At the same time, Procainamide and Metrodinazole were misclassified as false negatives compared to Passini et al. (2017). However, these drugs are controversial, as Metrodinazole is considered non-torsadogenic by Lancaster and Sobie (2016), and this study predicted both the drugs to be non-risky. Torsadogenic risk for all evaluated compounds and the confusion matrix of the classification are given in Figure 7C.

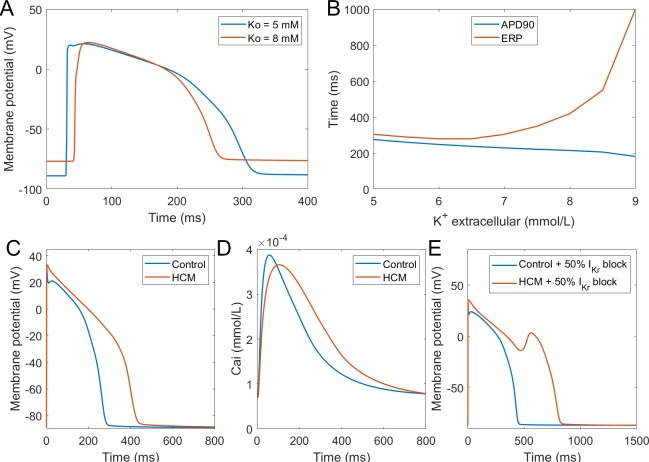

Validation: response to disease

Hyperkalemia

Hyperkalemia, the elevation of extracellular potassium, is a hallmark of acute myocardial ischemia caused by the occlusion of coronary artery. It was shown that hyperkalemia can significantly inhibit sodium channel excitability following repolarisation, leading to the prolongation of postrepolarisation refractoriness (Coronel et al., 2012). The dispersion of effective refractory periods (ERPs) between normal and ischemic zones forms a substrate for the initiation of re-entrant arrhythmia. In this new model, we tested the effect of hyperkalemia on tissue excitability using 1D fibres. As shown in Figure 8A, the elevation of extracellular potassium level led to an increase of the resting membrane potential (RMP) and the decrease of AP upstroke amplitude. As a result of weaker upstroke and more depolarised RMP, the APD shortened under hyperkalemia; however, the ERPs were prolonged due to the stronger sodium channel inactivation caused by the elevation of RMP (Figure 8B). Therefore, this new model successfully reproduced the longer post-repolarization refractoriness under hyperkalemia observed in experiments, and it can be used in the simulations of re-entrant arrhythmia under acute ischemia. In this regard, it presents an improvement over the original ORd model, which did not manifest postrepolarisation refractoriness without further modifications (Dutta et al., 2017b).

Figure 8. Simulation of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) and hyperkalemia.

(A) The effect of hyperkalemia on AP morphology; measured in the centre of a simulated fibre. (B) APD90 and effective refractory period (ERP) at varying extracellular potassium concentration. For extracellular potassium higher than 9 mM, full AP did not develop, but low-amplitude activation propagated through the fibre (Appendix 1-14). Membrane potential (C) and calcium transient (D) at 1 Hz pacing compared between a single healthy and HCM cell. (E) 50% IKr block induces EADs in HCM cell, but not in a healthy one.

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is among the most common cardiomyopathies, manifesting as abnormal thickening of the cardiac muscle without an obvious cause (Coppini et al., 2013). Beyond mechanical remodelling, the disease predisposes the hearts to arrhythmia formation, increasing the vulnerability to early afterdepolarisations. HCM induces complex multifactorial remodelling of cell electrophysiology and calcium handling, making it a challenging validation problem for a computer model. We applied the available human experimental data on HCM remodelling (based predominantly on Coppini et al., 2013) to our baseline model using an approach similar to Passini et al. (2016), observing that the dominant features of the remodelling observed by Coppini et al. are captured. The HCM variant of the computer model corresponds to experimental data in the AP morphology, manifesting a significantly higher plateau potential and an overall APD prolongation (Figure 8C). The calcium transient amplitude of the HCM model is slightly reduced, has longer time to peak, and a noticeably longer duration at 90% recovery (Figure 8D), also consistent with the data by Coppini et al. (2013). Ultimately, the HCM variant of our model is more prone to the formation of EADs (Figure 8E), as was shown experimentally (Coppini et al., 2013). This difference is in line with postulated key role of ICaL and NCX in EAD formation (Luo and Rudy, 1994; Weiss et al., 2010), both of which are markedly increased in HCM. Excessive prolongation of APD due to a strong increase in late sodium current in HCM also contributes to the EAD formation as well, as shown by Coppini et al. (2013).

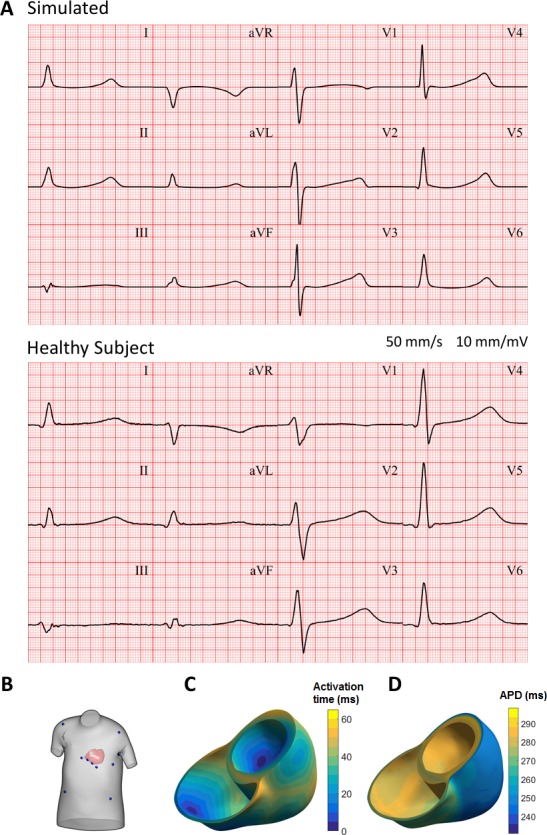

Validation: human whole-ventricular simulations - from ionic currents to ECG

We conducted 3D electrophysiological simulations using the ToR-ORd model, representing the membrane kinetics of endocardial, epicardial and mid-myocardial cells to investigate their ability to simulate the ECG (see Appendix 1-15.1.5). Transmural and apex-to-base spatial heterogeneities as well as fibre orientations based on the Streeter rule were incorporated into a human ventricular anatomical model derived from cardiac magnetic resonance (Lyon et al., 2018).

Figure 9A shows the resulting electrocardiogram computed based on virtual electrodes positioned on a torso model shown in Figure 9B. The ECG manifests a QRS duration of 80 ms (normal range 78 ± 8 ms), and a QT interval of 350 ms (healthy:<430 ms); all of these quantitative measurements are in the range of ECGs of healthy persons (Engblom et al., 2005; van Oosterom et al., 2000). ECG morphology also showed normal features, such as R wave progression in the precordial leads from V1 to V6, isoelectric ST segment, and upright T waves in leads V2 to V6, with inverted T wave in aVR. Figure 9C shows the activation sequence is in agreement with Durrer et al. (1970). The APD map shows longer APD in the endocardium and the base, and shorter APDs in the epicardium and the apex, respectively (Figure 9D).

Figure 9. Simulated and clinical 12-lead electrocardiogram.

(A) 12-lead ECGs at 1 Hz: simulation using the ToR-ORd model in an MRI-based human torso-ventricular model (top) and a healthy patient ECG record (bottom, https://physionet.org, PTB database, subject 122; Bousseljot et al., 1995; Goldberger et al., 2000). (B) Electrode positions on the simulated torso. (C) Activation time map. (D) APD map.

Discussion

In this study, we present a new model of human ventricular electrophysiology and excitation contraction coupling, which is able to replicate key features of human ventricular depolarisation, repolarisation and calcium transient dynamics. The ToR-ORd model was developed using a defined set of calibration criteria and subsequently validated on features not considered during calibration to demonstrate its predictive power. This article also unravels several important theoretical findings with implications for computational electrophysiology reaching beyond the ToR-ORd model and cardiac electrophysiology: firstly, the reformulation of the L-type calcium current, which is broadly relevant and generally applicable to human and other species, and secondly, the mechanistically guided replacement of IKr. Discovering the necessity to carry out these theoretical reformulations was enabled by the comprehensive set of calibration criteria and the use of a genetic algorithm to fulfil them. Finally, to enable reproducibility, we openly provide an automated model evaluation pipeline, which provides a rapid assessment of a comprehensive set of calibration or validation criteria.

The AP morphology of ToR-ORd is in agreement with the Szeged endocardial myocyte dataset used to construct the state-of-the art ORd model (O'Hara et al., 2011). The agreement is considerably better than that of ORd itself, which has important implications for multiple aspects studied in this work. The calcium transient also recapitulates key features of human myocyte measurements (Coppini et al., 2013). The validation of ToR-ORd shows that the model responds well to drug block with regards to APD (Dutta et al., 2017a). Good APD accommodation (reaction to abrupt, but persisting changes in pacing frequency) indicates a good balance between ionic currents (Franz et al., 1988; Pueyo et al., 2010). Replication of arrhythmia precursors such as early afterdepolarisations (Guo et al., 2011) and alternans (Koller et al., 2005) makes the model useful for simulations and understanding of arrhythmogenesis. This is particularly important in the context of heart disease, where ToR-ORd is shown to replicate key features of hyperkalemia (Coronel et al., 2012) and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (Coppini et al., 2013). The model is also shown to be promising in drug safety testing, and whole-heart simulations demonstrate physiological conduction velocity (Taggart et al., 2000) and produce a plausible ECG signal. Among the improved behaviours compared to the state-of-the-art ORd model (O'Hara et al., 2011), the good response of the ToR-ORd model to sodium blockade is particularly noteworthy. ToR-ORd predicts the negative inotropic effect of sodium blockade, consistent with data (Gottlieb et al., 1990; Tucker et al., 1982; Legrand et al., 1983; Bhattacharyya and Vassalle, 1982), unlike ORd, which suggests a strong pro-inotropic effect. The improvement in ToR-ORd follows from the relatively complex interplay of the theoretically driven reformulation of the L-type calcium current and data-driven changes to the AP morphology. This result is of great importance in the context of pharmacological sodium blockers, but it also plays a crucial role in disease modelling, where both fast (Pu and Boyden, 1997) and late (Coppini et al., 2013) sodium current are altered.

An important feature of a model is its predictive power, and validation of a model using data not employed in model calibration is a central aspect of model credibility (Pathmanathan and Gray, 2018; Carusi et al., 2012). With this in mind, we designed our study to first calibrate the developed model using a set of given criteria, with subsequent validation of the model using separate data that were not optimised for during development. The fact that ToR-ORd manifests a wide range of behaviours consistent with experimental studies, even though it was not optimised for these purposes, suggests its generality and a large degree of credibility. To facilitate future model development, we also created an automated ‘single-click’ pipeline, which evaluates a wide range of calibration and validation criteria and creates a comprehensive HTML report. New follow-up models can thus be immediately tested against criteria presented here, making it clear which features of the model are improved and/or deteriorated by any changes made.

The greatest theoretical contribution of this work is the theory-driven reformulation of the L-type calcium current, namely the ionic activity coefficients and activation curve extraction. Activation curve of the current in previous cardiac models was based on the use of Nernst driving force in experimental studies, but the models then used Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz driving force to compute the current. This yields a theoretical inconsistency present in existing influential models of guinea pig, rabbit, dog, or human, for example (Luo and Rudy, 1994; Hund et al., 2008; O'Hara et al., 2011; Shannon et al., 2004; Grandi et al., 2010; Carro et al., 2011). We propose and demonstrate that in order to obtain consistent behaviour, the experimental I-V relationship measurements are to be normalised using the Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz driving force instead. Updated ionic activity coefficients and activation of the L-type calcium current improve key features of the current observed in the study underlying the ORd L-type calcium current model (Magyar et al., 2000), and strongly contribute to the improved reaction of the model to sodium blockade. The changes made are relevant in development of future models which use the Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz equation for L-type calcium current or other currents.

A second major contribution of this work reaching beyond the model itself is the set of observations on modelling of IKr, the dominant repolarising current in human ventricle. We noticed limitations of the ORd IKr model, which may be a result of the single-pulse voltage clamp protocol to characterise the current behaviour. Approaches enabling the dissection of activation and recovery from inactivation based on more comprehensive experimental data, such as Lu et al. (2001) used in our work, may yield a more general and plausible model. In this study, this change was important predominantly for the response of the ventricular cell to calcium block, but our observations are highly relevant also for models of cells with naturally low plateau, such as Purkinje fibres or atrial myocytes.

We anticipate that the main future development of the presented model will focus on the ryanodine receptor and the respective release from sarcoplasmic reticulum. Similarly to most existing cardiac models, the equations governing the release depend directly on the L-type calcium current, rather than on the calcium concentration adjacent to the ryanodine receptors, which is the case in cardiomyocytes. Future development of the ryanodine receptor model and calcium handling will extend the applicability of the model to other calcium-driven modes of arrhythmogenesis, such as delayed afterdepolarisations. Also, while the model represents to a certain degree the locality of ICaL calcium influx and calcium release via the utilization of the junctional calcium subspace, a more direct representation of local control (Stern, 1992; Hinch et al., 2004), realistic spatially distributed calcium handling (Colman et al., 2017), or representation of stochasticity, may improve the insights the model can give into calcium-driven arrhythmogenesis. However, we note that such changes (particularly the detailed distributed calcium handling) will increase computational cost of the model's simulation. In addition, further research on the mechanisms regulating AP dependence on extracellular calcium concentration is needed to update this feature, not currently reproduced by most current human models (Passini and Severi, 2014).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Prof. Yoram Rudy, Prof. Derek Terrar, and Dr. Derek Leishman for very useful discussions.

Appendix 1

1. Calibration criteria

This section provides additional information to the criteria listed in Table 1.

The AP morphology was based primarily on the large experimental dataset of human undiseased endocardial recordings from the Varró lab, published in Britton et al. (2017). The ORd model (O'Hara et al., 2011) was based on a subset of these recordings. We aimed for similarity with the median of the AP data during the plateau and repolarization phase (from 15 ms after the AP peak). Two other datasets were used to confirm that early plateau potentials are ca. 20 mV, rather than the >30 mV as in ORd (Coppini et al., 2013; Jost et al., 2013).

The calcium transient morphology (CaT amplitude and duration at 90% recovery) was based on Coppini et al. (2013), particularly given it is clear that the AP morphology is similar in their experimental recordings and the simulations with the TOR-ORd model. The aim was for the two CaT properties to lie within standard deviation of mean. A correction for the difference in APD with regards to CaT amplitude was made in Appendix 1-8.

The properties of ICaL, the I-V relationship and steady-state inactivation were taken as reported in Magyar et al. (2000), as this is the primary dataset used in the ORd ICaL construction. Visual assessment of simulations versus data was used.

Negative inotropy of sodium blockers was based on Gottlieb et al. (1990); Tucker et al. (1982); Legrand et al. (1983); Bhattacharyya and Vassalle (1982), which report 8–28% reduction in whole-heart contractility, depending on drug, dose and index of contractility. Given the variability, throughout the calibration of a single-cell model, we aimed for any reduction in CaT amplitude following 50% reduction of INa and INaL.

The blockade of ICaL is known to shorten APD across species, including human (O'Hara et al., 2011). Within the process of calibration, we aimed for any APD shortening at 50% ICaL reduction.

EADs were shown to form under ca. 85% IKr block in human myocytes at 0.25 Hz pacing (Guo et al., 2011). Thus, we aimed for the new model to manifest EADs of similar amplitude as in the data (ca. 14 mV) in corresponding conditions.

APD alternans was observed in undiseased human cells at rapid pacing (Koller et al., 2005). We aimed for a model manifesting APD alternans, with the onset at basic cycle length shorter than 300 ms.

The reported conduction velocity in human heart is 65 m/s (Taggart et al., 2000), and we compared this value to the result of a fibre simulation using the developed ToR-ORd model.

2. Genetic algorithm fitness

The fitness function has 18 inputs, 16 of which are the multipliers of conductances for the following currents and fluxes: INa, ICaL, Ito, INaL, IKr, IKs, IK1, IKb, INaCa, INaK, INab, ICab, IpCa, ICaCl, Jrel, Jup. Also varied were ,Rel, a parameter of Jrel (constrained between 0.9 and 1.7) and the fraction of INaCa in the junctional subspace (constrained between 0.18 and 0.4).

If the genetic algorithm (GA) employed symmetric percentual variations of raw current multipliers (e.g., + /- 50%), it would not sample the input space evenly – for example, a symmetric Gaussian mutation is much more likely to halve a parameter than to double it (assuming the Gaussian curve being centred at 1, the density in 0.5 is the same as in 1.5, but not in 2), while the likelihood should be arguably the same. The initial population would also likely be highly skewed towards current reduction. In order to avoid these issues, we made the GA work internally with logarithms of multipliers, which makes the sampling symmetrical (-log(0.5)=log(2), etc.). The fitness function first exponentiates the log-multipliers to obtain the actual multipliers, and these are subsequently used in further simulation.

Within the fitness function, the evolved model is pre-paced for 130 beats at 1 Hz, with the final state X130. Subsequently, 20 more beats are simulated at the following conditions, with X130 as the starting state: a) no change to parameters, b) sodium blockade (50% INa block, 50% INaL block), c) calcium blockade (50% ICaL block), d) IK1 blockade (50% block). 150 beats in total for the control condition is a compromise between total runtime and similarity to the stable-state behaviour. The 20 beats at various conditions following 130 beats of prepacing are sufficient to manifest the effects of the respective blocks , while keeping the runtime low (When the model is evaluated in the manuscript, the outputs are based on 1000 beats of pre-pacing; the 150 or 130+20 beats are used only during model refitting to allow sufficiently fast runtime.).

Based on these simulations, a two-element fitness vector is obtained; the first element describes similarity of action potential (AP) morphology to the reference, with the second element aggregating other criteria (calcium transient duration and amplitude, calcium transient amplitude reduction with sodium blockade, action potential duration (APD) reduction with calcium blockade, and a depolarisation with IK1 block).

Not all calibration criteria (Table 1) were represented in the fitness function, as simulating all corresponding protocols would be prohibitively slow. Instead, the calibration criteria not optimized using the genetic algorithm were subsequently fulfilled by mechanistically informed manual changes, while making sure the already optimised criteria were not violated.

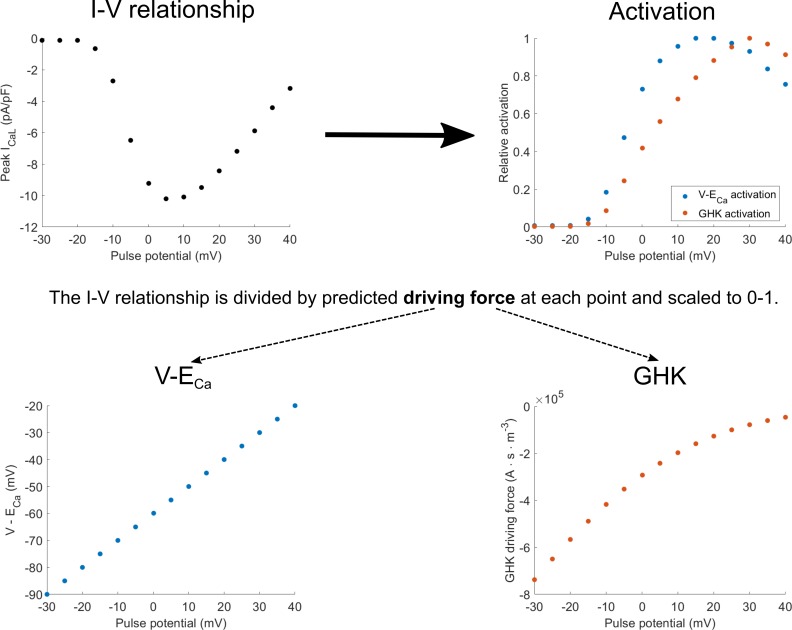

3. Extraction of ICaL activation from I-V relationship

The experimental protocol to measure I-V relationship of the ICaL uses square pulse stimuli to measure peak current for different pulse potentials (Appendix 1—figure 1, top left). The peak current can be seen as the product of two components: activation (how open the channels are) and driving force (the strength of the diffusion and electrical gradients that produce ionic flow through the open channels). To obtain the activation value for each pulse potential, the corresponding peak current is divided by the theoretical estimate of the driving force. The resulting curve can then be scaled to 0–1, producing estimated fractional activation (Appendix 1—figure 1, top right). The driving force may be computed based on the linear equation V-ECa, or the nonlinear Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz (GHK) flux equation (Appendix 1—figure 1, bottom left and bottom right, respectively). This yields the two corresponding activation curves in Appendix 1—figure 1, top right.

Appendix 1—figure 1. Diagram of how activation curves are extracted from the I-V relationship.

The activation curves (top right) are obtained by dividing values in the I-V curve (top left) at each pulse potential by the driving force considering either V-ECa-based driving force (bottom right) or the Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz (GHK) flux equation (bottom left).

Appendix 1—figure 1 can be also used to illustrate the theoretical inconsistency in the ORd model and many other models (e.g. Luo and Rudy, 1994; Hund et al., 2008; O'Hara et al., 2011; Shannon et al., 2004; Grandi et al., 2010; Carro et al., 2011): the V-ECa driving force is used to obtain the activation curve, but then the ICaL is computed using the GHK driving force, which does not yield the original data, as illustrated in the Results section. Returning to the notion of I-V relationship as a product of activation and driving force, the same shape of I-V relationship can be obtained by pointwise multiplication of the blue driving force (bottom, left) with blue activation (top, right), or the red driving force (bottom, right) with red activation (top, right). However, simulating the I-V relationship using the ORd model corresponds to the product of blue activation and the red driving force, which then naturally does not match greatly the original I-V relationship (Figure 2D, or Appendix 1—figure 2 in Appendix 1-4).

Appendix 1—figure 2. Effect of the proposed changes in the activation curve and activation coefficient on the I-V relationship of ICaL in ORd versus ToR-ORd.

4.ICaL updates and the I-V relationship

Appendix 1—figure 2 illustrates the effect that updates in activation curve and activation coefficients have on the simulated ICaL I-V relationship considering four models:

Control ORd

ORd with updated activity coefficients as in ToR-ORd (fixed to 0.6532/0.6117 for intracellular/extracellular calcium, 0.89/0.88 for intracellular/extracellular sodium; the same also for potassium)

ORd with updated activation curve as in ToR-ORd • ToR-ORd model.

The I-V curves were normalised to a minimum of −1, in order to focus on the shape of the I-V curve rather than its amplitude (which is modulated by maximal conductance). Considering the new activation curve extracted using the GHK equation in the ORd model yields a near-identical I-V curve to the ToR-ORd model (Appendix 1—figure 2). This demonstrates this is the key mechanism in the I-V curve improvement. The update of activity coefficients did not alter the shape of the I-V relationship noticeably compared to the ORd model (Appendix 1—figure 2), but played a key role in avoiding the reversal of ICaL illustrated in Figure 2F and a good response to sodium block, as explained in the next section.

5. Extraction of steady-state inactivation of ICaL

As shown in Figure 2E of the main manuscript, the steady-state inactivation curve of the ORd model differs from the experimental data. This is surprising, given that both the steady state voltage and calcium inactivation in the model are a direct fit to the experimental data. The explanation of this phenomenon lies in the construction of the ICaL equation in the ORd model, which is as follows (only the non-phosphorylated part is given; the phosphorylated is analogous):

where is the product of driving force and channel conductance, is activation, is voltage-driven inactivation, is a weight of calcium inactivation, is calcium-driven inactivation, and corresponds to recovery from inactivation. In the ORd model, stable-state values of are all fit to the steady-state inactivation in Magyar et al. (2000). During a long voltage clamp pulse used to inactivate ICaL, and can be assumed to be constant, leaving the remaining parentheses as the factor determining measured inactivation. If was equal to 1, then the equation would reduce to the experimentally observed inactivation in the steady state (however, this prevents formation of EADs). However, given that effectively acts as a second inactivation, the product corresponds to a square of the experimentally observed inactivation, making the inactivation stronger. Thus, for , this ICaL model manifests total steady-state inactivation stronger than the one from Magyar et al. (2000).

As shown in Figure 2E of the main manuscript, this problem is not present in the ToR-ORd model, which yields a better match with experimental data than ORd. Inspecting state variables at the inactivating pulse potentials where the models differ (approximately between -30 and -5 mV), we observed that the ORd model has a higher level of calcium in the subspace, increasing the value of the variable, making the contribution of the overestimated inactivation stronger. The higher calcium level in the subspace in the ORd model seems to arise from a combination of two factors: (1) Overestimated activation and thus enhanced calcium entry in ORd (evident from Figure 2 C, D in the main manuscript), accompanied by small differences in Jrel formulation translating into more SR release in ORd; (2) less total NCX in the subspace, corresponding to less calcium clearance.

It is worth noting that the exact shape of the simulation-based inactivation curve depends on how exactly the conditions in Magyar et al. (2000) are represented. As explained in Appendix 1-15.1.1, intracellular and potassium are fixed when the steady-state inactivation is measured, but calcium is not fixed. If the intracellular calcium in the model was also clamped to the zero concentration of the pipette, would be zero and both ORd and ToR-ORd would fit the inactivation curve well.

6. ICaL reversal and ionic activity coefficients

As illustrated in Figure 2F, the ToR-ORd model yields a consistently inward ICaL during the AP, whereas for the ORd, there is a reversal to outward ICaL following the peak of the AP. For the ORd midmyocardial cell, ICaL is highly positive (ICaL = 3.32 pA/pF) at t = 4.3 ms. This can be explained by the update in the ionic activity coefficients described in section Methods: Determining ionic activity coefficients. The sign of ICaL is determined by the sign of the driving force (other components of ICaL are the permeability constant, and gating variables, both of which are nonnegative). The GHK equation for driving force (with all elements explained in Materials and methods of the main manuscript) can be divided into four components for clarity (Appendix 1—figure 3). Components 1 and 4 are positive (V = 33 mV at this point of simulation) and thus do not affect the sign; therefore, the sign of the driving force in this case is determined by the relative size of components 2 and 3. In control ORd (with activity coefficients of 1 and 0.341 for intracellular/extracellular space), we have, for components C2 and C3:

where are intra/extracellular activity coefficients, is the calcium concentration in junctional subspace, and is extracellular calcium concentration. Therefore, C2 > C3 and the sign of driving force (and thus also ICaL) is positive.

Appendix 1—figure 3. Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz equation with colour coding of components.

However, if we use ionic activity coefficients based on ToR-ORd (0.6532 and 0.6117 for intracellular/extracellular), we get:

Therefore, in this case, C2 < C3, and the sign of driving force and ICaL is negative and thus consistently inward during the AP.

7. P2/P1 protocol for ICaL

We compared the results of the ToR-ORd and ORd models to experimental data in human myocytes for the P2/P1 protocol reported by Fülöp et al. (2004) as previously shown in the original ORd model study (O'Hara et al., 2011). In this protocol, two rectangular pulses (from −40 mV to 10 mV, lasting either 25 ms or 100 ms) are applied, and the ratio of peak ICaL during the second pulse versus the first one is computed. Simulated curves with both models are consistent with the data in that a) 25 ms pulse curve lies above the 100 ms pulse curve, b) shorter coupling interval is associated with less current availability (Appendix 1—figure 4). Both models show an offset to the experimental data. This could be due to a) Difference in ICaL behaviour/density and/or calcium loading (affecting inactivation) between the Fülöp (P2/P1 protocol) and Magyar (the main basis for the ICaL model) studies. It could be also linked to mechanisms of ICaL inactivation not represented in the model (e.g. the inactivation by the calcium flow through the channel, represented for example by Mahajan et al., 2008).

Appendix 1—figure 4. P2/P1 protocol for two pulse durations.

8. Calcium transient amplitude in ToR-ORd

The calcium transient amplitude of 312 nM in baseline ToR-ORd is slightly below the mean ± std range of 350 (330-370) nM in Coppini et al. (2013). However, we hypothesised that the difference might be due to the different APD, which affects the calcium loading of the cell by modulating ICaL duration. When the APD of the ToR-ORd was extended to 351.5 ms (close to ca. 350 ms reported by Coppini et al.) by reducing IKr by 45%, the calcium transient amplitude increased to 360 nM, which is close to the data mean. After such an AP prolongation, both time to peak (54 ms) and calcium transient duration at 90% recovery (459 ms) remained within standard deviation of the data.

9. Summary of literature on sodium blockers, INa, and INaL reduction

The exact ratio of pharmacological block of INa and INaL is drug and dose-dependent, with late sodium current generally being blocked somewhat more than the fast sodium current. For flecainide applied to wild-type Nav1.5, the IC50 value of INa and INaL were 127 ± 6 and 44 ± 2 μM, respectively; for example, for 50% INa block, a 75% INaL block would be expected (Nagatomo et al., 2000). In the case of TTX, the IC50 values appear to be more similar for the two currents: 1.2 μM for INa (Bradley et al., 2013) and 0.95 μM for INaL (Horvath et al., 2013). Lidocaine also appears to block INaL preferentially: the measured IC50 for INaL is 10.79 μM (Crumb et al., 2016), which is lower than 44 μM measured for INa (Janssen Pharmaceutical internal database, referred to in Passini et al., 2017). However, we note that comparing IC50 values between studies has limited quantitative relevance, given expected differences between conditions and protocols.

10. Role of ICaL properties and AP morphology in calcium transient changes by sodium blockade

The changes in AP morphology and ICaL introduced in the ToR-ORd model improved its response to Na currents block, particularly with respect to reduction of the Ca transient amplitude (illustrated in Figure 3). To further dissect the contribution of differences between ToR-ORd and ORd in AP morphology and ICaL properties, we simulated two AP clamp scenarios using the four different models considered previously in Appendix 1—figure 2 (i.e. ORd, ORd and ToR-ORd activity coefficients, ORd and ToR-ORd ICaL activation curve, and ToR-ORd). The first scenario applied an AP clamp based on ORd AP morphologies for control and for 50/50% INa/INaL block (as shown in Figure 3B). The second scenario considered AP clamps based on ToR-ORd AP morphologies in control and 50/50% INa/INaL block (as shown in Figure 3A). For each of the four models and the two AP clamp scenarios, the ratio of calcium transient amplitudes (sodium-block versus control) was computed (Appendix 1—table 1). This allowed quantifying the importance of differences in AP morphology and updates to the ICaL representation with regard to CaT amplitude changes under sodium block.

Appendix 1—table 1. Dissection of improvement in reaction to sodium blockade.

Ratios of calcium transient amplitudes for AP clamps corresponding to baseline and sodium-blocked models, arising from ORd and ToR-ORd. Row/column numbering used in the text does not include the header and the first column which describes the models (i.e. the text refers to four rows and two numerical columns).

| Model | ORd AP clamps | ToR-ORd AP clamps |

|---|---|---|

| M1 (ORd) | 1.366 | 1.061 |

| M2 (ORd with ToR-ORd activity coefficients) | 1.301 | 0.999 |

| M3 (ORd with ToR-ORd activation curve) | 1.326 | 1.015 |

| M4 (ToR-ORd) | 1.193 | 0.985 |