Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Food insecurity affects 1 in 8 households in Canada, with serious health consequences. We investigated the association between household food insecurity and all-cause and cause-specific mortality.

METHODS:

We assessed the food insecurity status of Canadian adults using the Canadian Community Health Survey 2005–2017 and identified premature deaths among the survey respondents using the Canadian Vital Statistics Database 2005–2017. Applying Cox survival analyses to the linked data sets, we compared adults’ all-cause and cause-specific mortality hazard by their household food insecurity status.

RESULTS:

Of the 510 010 adults sampled (3 390 500 person-years), 25 460 died prematurely by 2017. Death rates of food-secure adults and their counterparts experiencing marginal, moderate and severe food insecurity were 736, 752, 834 and 1124 per 100 000 person-years, respectively. The adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) of all-cause premature mortality for marginal, moderate and severe food insecurity were 1.10 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.03–1.18), 1.11 (95% CI 1.05–1.18) and 1.37 (95% CI 1.27–1.47), respectively. Among adults who died prematurely, those experiencing severe food insecurity died on average 9 years earlier than their food-secure counterparts (age 59.5 v. 68.9 yr). Severe food insecurity was consistently associated with higher mortality across all causes of death except cancers; the association was particularly pronounced for infectious-parasitic diseases (adjusted HR 2.24, 95% CI 1.42–3.55), unintentional injuries (adjusted HR 2.69, 95% CI 2.04–3.56) and suicides (adjusted HR 2.21, 95% CI 1.50–3.24).

INTERPRETATION:

Canadian adults from food-insecure households were more likely to die prematurely than their food-secure counterparts. Efforts to reduce premature mortality should consider food insecurity as a relevant social determinant.

Food insecurity — inadequate access to food because of financial constraints — is a public health concern in Canada. 1,2 In 2007/08, 11.3% of households experienced food insecurity; the figure rose to 12.4% by 2011/12.1,2 Food insecurity is associated with negative health outcomes and higher health care spending in a graded fashion, with more severe food insecurity corresponding to worse health and greater health care utilization. 3–5 Food insecurity predicts higher incidence of chronic conditions and poorer management of them.6–14 Food insecurity is also associated with mental disorders,15–18 suicidal thoughts19,20 and suicide attempts.21 Despite much evidence linking food insecurity to poor health, less is known about the association between food insecurity and mortality.

A graded association between severity of food insecurity and all-cause mortality risk was found among working-age adults in Ontario, Canada.22 A study of the US adult population found very low food insecurity — equivalent to severe food insecurity in Canada — was associated with higher all-cause mortality.23 In addition, 2 small studies found food insecurity to be associated with higher mortality odds among HIV-infected adults.24,25 However, none of these studies examined causes of death. More comprehensive, population-based research is needed to advance our understanding of the health burden associated with food insecurity.

Linking vital statistics to multiple cycles of a national health survey, we conducted a population-based retrospective cohort study to assess the association between household food insecurity status and Canadian adults’ all-cause and cause-specific premature mortality.

Methods

Study sample

We linked the 2005–2017 Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) to the 2005–2017 Canadian Vital Statistics Database and 2003–2017 Discharge Abstract Database.

The Canadian Community Health Survey is a biennial cross-sectional survey, representing 98% of the Canadian noninstitutionalized population aged 12 years and older. The survey randomly samples households nationwide, comprising roughly 130 000 households per 2-year cycle. The household food security module is a regular CCHS component, but certain jurisdictions chose not to administer the module when it was optional (Appendix 1, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.190385/-/DC1). CCHS Sharelink is a CCHS sub-sample with about 85% of total respondents, who agreed to have their responses linked to administrative records.26 Statistics Canada created sample weights for CCHS Sharelink to retain population representativeness.26 CCHS Sharelink resembles CCHS in sociodemographic characteristics.26

The Canadian Vital Statistics Database is an administrative database containing the date and primary cause of all deaths registered by Canadian jurisdictions. The cause of death is coded using the Canadian version of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision (ICD-10-CA; Appendix 2, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.190385/-/DC1),27 which has been extensively applied in mortality research.28,29 Data on all individuals aged 12 years or older who died between 2000 and 2017 are linkable to CCHS data.26,30

The Discharge Abstract Database is an administrative database containing the clinical information of all patients admitted to hospital in Canada, excluding the province of Quebec. For each hospital admission from 1996 to 2018, the Discharge Abstract Database registers the admission and discharge dates and the most responsible diagnosis, coded into ICD-10-CA. To limit the focus to morbidity-related hospital admissions, we omitted admissions related to pregnancy, same-day surgery and prescheduled examinations.

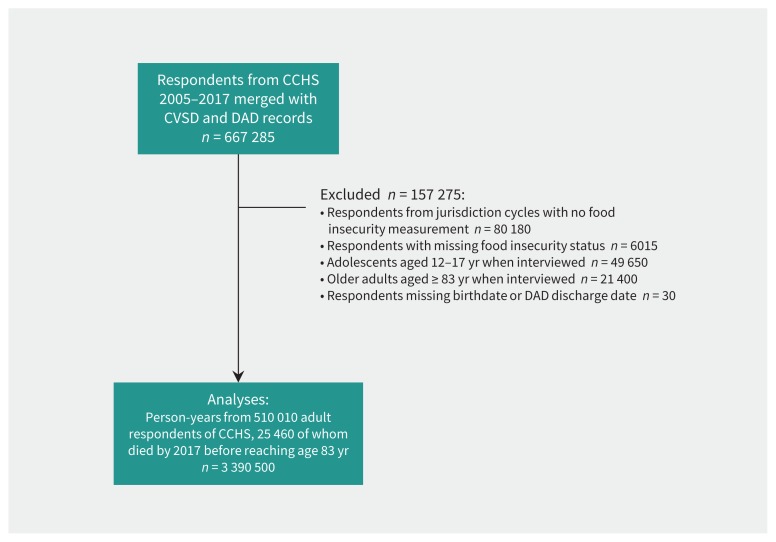

We linked CCHS respondents to Canadian Vital Statistics Database death records; those without a link were presumed alive on Dec. 31, 2017. We also performed one-to-many linkage between CCHS respondents and the Discharge Abstract Database hospital admission records. The linkages of CCHS with the Canadian Vital Statistics Database and the Discharge Abstract Database are of high quality, with few false links.30,31 After linking the 3 data sets, we excluded respondents from jurisdiction cycles that opted out of the food security module (Figure 1). We also excluded children younger than 18 years, seniors older than 82, and individuals with missing food insecurity status or miscoded hospital records. The 2017 CCHS data on territories were not available for analyses. By applying weights from CCHS Sharelink, our sample is representative of the noninstitutionalized adult population aged 18–82 years with valid food security status in the selected jurisdictions and years included in our analyses. To protect confidentiality, we rounded numbers of observations according to Statistics Canada’s rules on analysis of linked data.

Figure 1:

Sample selection process. Note: CCHS = Canadian Community Health Survey, CVSD = Canadian Vital Statistics Database, DAD = Discharge Abstract Database.

Outcome measures

The outcomes were all-cause and cause-specific premature mortality, defined as “death that occurs before the average age of death in a certain population.”32 Life expectancy for 18-year-old Canadians in 2008–2014 was approximately 82 years;33 thus, we regarded deaths as premature if they occurred before age 83 years between the CCHS interview date and Dec. 31, 2017.

Using ICD-10-CA, we separated deaths by “communicable diseases and injuries” from deaths by “noncommunicable diseases.” We categorized the former into “infectious-parasitic diseases,” “unintentional injuries,” “suicides” and “other miscellaneous communicable diseases and injuries.” We categorized the latter into “cancers,” “circulatory-respiratory diseases,” “metabolic-digestive diseases” and “other miscellaneous noncommunicable diseases.” To better gauge the effect of intervention, we identified causes of death considered to be potentially avoidable through adequate public health prevention and medical treatment (Appendix 3, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.190385/-/DC1).34 The concept of avoidable mortality was introduced in 1976 as “unnecessary untimely deaths” to measure quality of medical care, and since then has been widely used to assess health system performance.35,36

Food insecurity measure

The exposure was 12-month household food insecurity status. This was based on a validated 18-item scale of severity developed by the US Department of Agriculture to assess the adequacy of households’ access to food over the past 12 months (Appendix 4, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.190385/-/DC1).37 Based on the number of affirmative answers, households were classified as food-secure, marginally food-insecure, moderately food-insecure or severely food-insecure, following the classification scheme developed by Health Canada and applied in other studies (Appendix 5, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.190385/-/DC1).4,5,22,38

Control variables

We controlled for individual demographic characteristics, baseline health and household socioeconomic characteristics to isolate the association between food insecurity and mortality. Demographics included respondents’ sex and age at interview. Baseline health included any acute care admission to hospital in the past 2 years, smoker status, past-year alcohol consumption and number of self-reported chronic conditions among cancer, hypertension, effects of stroke, diabetes and heart diseases. We further controlled for socioeconomic characteristics including household income, housing tenure, highest education in household and household type.

Before-tax household income was unavailable for 20.6% of the respondents, including all from 2017. Quebec respondents, representing 24.3% of the sample, all had missing hospital admission records. A total of 5.2% of the sample had missing values for 1 or more other covariates. We kept all the jurisdictions (including Quebec) and cycles (including 2017) with valid food security status for analyses. We adjusted for missing hospital admission records from Quebec, missing income from 2017 and previous years, and other missing values as additional model covariates.

Statistical analyses

We first compared sample characteristics between those who died prematurely and those who did not. The statistics were generalizable to the noninstitutionalized Canadian adults aged 18–82 years with valid food insecurity status in the sampled jurisdiction cycles. We then computed death counts and crude mortality rates by cause of death as well as age at interview and age at death by food insecurity status. We fitted Cox proportional hazard models to estimate mortality hazard by food insecurity status while adjusting for potential confounders. Based on results from the Schoenfeld residuals test, we set respondents’ sex, age at interview, recent hospital admission and number of chronic conditions as strata in Cox models to cope with their violation of the proportional hazard assumption (Appendix 6, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.190385/-/DC1).

In the survival analyses, we first estimated all-cause mortality for the overall sample and then split the sample by sex and analyzed all-cause mortality for men and women separately. We finally examined the association of food insecurity with cause-specific mortality for the overall sample. We used Statistics Canada’s sample weights to compute sample characteristics by CCHS respondents’ vital status. We also applied weights to compute average age at interview and age at death by food insecurity status. We conducted sensitivity tests on all-cause mortality to ensure that findings were not driven by weights, outliers, missing values, sampling bias or choice of measurements; results resembled those from the main analyses. All analyses were done with 2-sided confidence intervals using Stata SE 15.1. Coefficients with p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Ethics approval

We obtained approval from the Health Sciences Research Ethics Board at the University of Toronto.

Results

The analytic sample consisted of 3 390 500 person-years from 510 010 adults. A total of 25 460 adults died before age 83 years between CCHS interview and Dec. 31, 2017 (Table 1). The 484 550 respondents who did not die prematurely by 2017 and the 25 460 who died prematurely by 2017 represented, respectively, 267 331 000 and 8 488 000 noninstitutionalized Canadian adults aged 18–82 years with valid food insecurity status. Compared with adults who did not die prematurely, those who did were less likely to be food secure and more likely to be male, older, smokers, chronically ill and with low income and education (p < 0.05 for all).

Table 1:

Weighted proportions and means of sample characteristics by premature death status*

| Characteristic | Died before age 83 yr by Dec. 31, 2017? | |

|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | |

| Unweighted number of respondents | 484 550 | 25 460 |

| Weighted population represented† | 267 331 000 | 8 488 000 |

| Household food insecurity status | ||

| Food-secure | 88.7 | 87.4 |

| Marginally food-insecure | 3.8 | 3.4 |

| Moderately food-insecure | 5.1 | 5.8 |

| Severely food-insecure | 2.3 | 3.4 |

| Demographics | ||

| Female | 50.9 | 42.1 |

| Age at interview, yr ± SD | 45.4 ± 16.6 | 63.2 ± 12.1 |

| Socioeconomics | ||

| Household income, $ | ||

| 0–20 000 | 5.4 | 13.9 |

| 20 001–40 000 | 12.3 | 24.2 |

| 40 001–60 000 | 13.3 | 15.5 |

| 60 001–80 000 | 12.5 | 10.1 |

| 80 001 and over | 33.8 | 14.6 |

| Missing from 2005 to 2016 | 12.3 | 20.8 |

| Missing from 2017 | 10.3 | 0.9 |

| Highest education in household | ||

| High school incomplete | 10.7 | 13.6 |

| High school graduate | 5.7 | 18.6 |

| Some college | 3.8 | 5.2 |

| College degree | 74.9 | 57.1 |

| Missing | 4.9 | 5.5 |

| Housing tenure | ||

| Renter | 26.2 | 30.1 |

| Homeowner | 73.7 | 69.8 |

| Missing | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Household type | ||

| Married with children | 42.2 | 16.1 |

| Married without children | 29.3 | 46.8 |

| Lone parents | 8.5 | 6.2 |

| Individuals and other types | 19.4 | 30.7 |

| Missing | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| Health | ||

| Admitted to hospital in last 2 years | ||

| No | 71.7 | 73.4 |

| Yes | 1.6 | 1.2 |

| Missing (Quebec) | 26.7 | 25.4 |

| Number of chronic conditions | ||

| None | 77.1 | 38.7 |

| 1 | 16.4 | 32.3 |

| 2 | 4.9 | 18.8 |

| 3+ | 1.1 | 8.8 |

| Missing | 0.5 | 1.4 |

| Smoker status | ||

| Never smoked | 38.7 | 20.8 |

| Former smoker | 40.3 | 47.9 |

| Current smoker | 20.8 | 31.1 |

| Missing | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| Alcohol consumption in last year | ||

| None | 49.4 | 38.7 |

| Up to once a week | 18.2 | 31.6 |

| Twice a week up to once a day | 32.2 | 29.3 |

| Missing | 0.2 | 0.4 |

Note: SD = standard deviation.

Proportions and mean values were weighted by sample weights. Unweighted number of respondents was rounded to nearest integer of 5. Weighted population represented was rounded to nearest integer of 1000.

Weighted population counts are for the whole study period 2005–2017 (i.e., multiple years of population appended together).

The crude mortality rate — number of deaths per 100 000 person-years — was higher for adults experiencing more severe food insecurity: 736 for food-secure adults compared with 752, 834 and 1124 for their marginally, moderately and severely food-insecure counterparts, respectively (Table 2). About 68% of premature deaths were potentially avoidable among food-secure adults; the comparable figures were 72%, 72% and 75% among their marginally, moderately and severely food-insecure counterparts, respectively. Noncommunicable diseases accounted for 90% (22 830/25 460) of total deaths, including 91% of deaths among food-secure adults and 84% of deaths among food-insecure adults. However, the share of food-insecure adults was proportionally higher among those who died from communicable diseases and injuries (19.5%) versus noncommunicable diseases (11.8%). Food-insecure adults also died earlier. The mean age at death was 68.9 years for food-secure adults compared with 64.4, 62.7 and 59.5 years for marginally, moderately and severely food-insecure adults, respectively (Table 3; p < 0.0001 for all, compared with food-secure adults).

Table 2:

Number of deaths and crude mortality rate by primary cause and food insecurity*

| Characteristic | Total | Food-secure | Marginally food-insecure | Moderately food-insecure | Severely food-insecure | Percent food-insecure, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sampled respondents | 510 010 | 452 890 | 18 370 | 25 600 | 13 150 | 11.2 |

| Person-years | 3 390 500 | 3 022 500 | 120 300 | 165 400 | 82 300 | 10.9 |

| All deaths | 25 460 (751) | 22 250 (736) | 905 (752) | 1380 (834) | 925 (1124) | 12.6 |

| Potentially avoidable deaths | 17 490 (516) | 15 145 (501) | 655 (544) | 1000 (605) | 690 (838) | 13.4 |

| Noncommunicable diseases | 22 830 (673) | 20 140 (666) | 780 (648) | 1185 (716) | 725 (881) | 11.8 |

| Cancers | 10 675 (315) | 9590 (317) | 320 (266) | 490 (296) | 275 (334) | 10.2 |

| Circulatory-respiratory diseases | 7775 (229) | 6770 (224) | 280 (233) | 460 (278) | 265 (322) | 12.9 |

| Metabolic-digestive diseases | 2140 (63) | 1790 (59) | 95 (79) | 135 (82) | 120 (146) | 16.4 |

| Other miscellaneous | 2250 (66) | 1990 (66) | 85 (71) | 105 (63) | 70 (85) | 11.6 |

| Communicable diseases and injuries | 2620 (77) | 2110 (70) | 120 (100) | 190 (115) | 200 (243) | 19.5 |

| Infectious-parasitic diseases | 410 (12) | 325 (11) | 25 (21) | 35 (21) | 25 (30) | 20.7 |

| Unintentional injuries | 945 (28) | 765 (25) | 40 (33) | 60 (36) | 80 (97) | 19.0 |

| Suicide | 470 (14) | 365 (12) | 30 (25) | 30 (18) | 45 (55) | 22.3 |

| Other miscellaneous | 800 (24) | 660 (22) | 25 (21) | 65 (39) | 50 (61) | 17.5 |

Crude mortality rate per 100 000 person-years is shown in parentheses. “Percent food-insecure” refers to the proportion of total deaths accounted for by marginally, moderately and severely food-insecure adults. Numbers of persons were rounded to the nearest integer of 5. Numbers of person-years were rounded to the nearest integer of 100. Numbers may not add up exactly due to rounding.

Table 3:

Mean age at interview and age at death by food insecurity

| Characteristic | Age at interview among individuals who did not die before age 83 by Dec 31, 2017 ± SE | Age at interview among individuals who died before age 83 ± SE | Age at death among individuals who died before age 83 ± SE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Mean age | 45.4 ± 0.08 | 63.2 ± 0.07 | 68.1 ± 0.02 |

| No. of persons | 484 550 | 25 460 | 25 460 | |

| Food-secure | Mean age | 46.0 ± 0.08 | 64.1 ± 0.08 | 68.9 ± 0.02 |

| No. of persons | 430 640 | 22 250 | 22 250 | |

| Marginally food-insecure | Mean age | 39.9 ± 0.43 | 59.7 ± 0.43 | 64.4 ± 0.09 |

| No. of persons | 17 465 | 905 | 905 | |

| Moderately food-insecure | Mean age | 40.4 ± 0.35 | 57.9 ± 0.35 | 62.7 ± 0.08 |

| No. of persons | 24 220 | 1380 | 1380 | |

| Severely food-insecure | Mean age | 41.0 ± 0.40 | 54.8 ± 0.41 | 59.5 ± 0.09 |

| No. of persons | 12 225 | 925 | 925 |

Note: SE = standard error.

Numbers of persons were rounded to the nearest integer of 5.

All-cause mortality

Marginal, moderate and severe food insecurity was associated with 1.62 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.51–1.73), 1.96 (95% CI 1.86–2.07) and 3.25 (95% CI 3.04–3.48) times higher mortality hazard after adjusting for respondents’ sex and age at interview (Table 4; Appendix 7, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.190385/-/DC1). The magnitude of the adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) decreased after further controlling for baseline health and socioeconomic status, but the associations remained significant at p < 0.05 for all levels of food insecurity, with adjusted HR being 1.10, 1.11 and 1.37 for marginal, moderate and severe food insecurity, respectively. Sensitivity tests confirmed that findings on all-cause mortality were not driven by outliers, missing records, sampling bias, weights or choice of measurements (Appendix 8, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.190385/-/DC1). The association between food insecurity and all-cause mortality hazard was similar for men and women (Appendix 9, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.190385/-/DC1).

Table 4:

Adjusted hazard ratios from Cox proportional hazard models on all-cause premature mortality among 510 010 adults aged 18–82 years at interview (3 390 500 person-years)*

| Household food insecurity status | Sex–age adjusted, HR (95% CI) | Fully adjusted, HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Food-secure | 1.00 (ref.) | 1.00 (ref.) |

| Marginally food-insecure | 1.62 (1.51–1.73) | 1.10 (1.03–1.18) |

| Moderately food-insecure | 1.96 (1.86–2.07) | 1.11 (1.05–1.18) |

| Severely food-insecure | 3.25 (3.04–3.48) | 1.37 (1.27–1.47) |

Note: CI = confidence interval, HR = hazard ratio, ref. = reference category.

Person-years were rounded to the nearest digit of 5. Hazard ratios (HRs) of food insecurity are displayed alongside 95% confidence interval (CI) in parentheses. The sex–age-adjusted model was adjusted for respondents’ sex and age at interview. The fully adjusted model, for the overall sample and by-sex subsamples, was further adjusted for household income, highest education in household, household type, housing tenure, acute care admission to hospital in the past 2 years, number of self-reported chronic conditions, smoker status and past-year alcohol consumption history.

Cause-specific mortality

Severe food insecurity was consistently associated with higher mortality hazard across all causes of death except cancers (Table 5; Appendix 10, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.190385/-/DC1). In comparison, marginal and moderate food insecurity was associated with fewer causes of death. Notable exceptions included infectious-parasitic diseases, which were associated with all levels of food insecurity; suicides, which were associated with marginal and severe food insecurity; and circulatoryrespiratory diseases, which were associated with moderate and severe food insecurity. In addition, higher mortality from potentially avoidable causes was observed across all levels of food insecurity.

Table 5:

Adjusted hazard ratios of cause-specific premature mortality by food insecurity status (n = 3 390 500 person-years)*

| Cause of death | Food-secure (reference) | Marginally food-insecure | Moderately food-insecure | Severely food-insecure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Noncommunicable diseases | ||||

| Cancers | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (0.89–1.12) | 1.06 (0.96–1.17) | 1.10 (0.96–1.26) |

| Circulatory-respiratory diseases | 1.00 (ref) | 1.09 (0.96–1.23) | 1.15 (1.04–1.27) | 1.24 (1.08–1.42) |

| Metabolic-digestive diseases | 1.00 (ref) | 1.18 (0.95–1.46) | 1.01 (0.84–1.23) | 1.44 (1.15–1.79) |

| Other miscellaneous | 1.00 (ref) | 1.26 (1.01–1.58) | 1.05 (0.85–1.31) | 1.55 (1.18–2.02) |

| Communicable diseases and injuries | ||||

| Infectious-parasitic diseases | 1.00 (ref) | 1.87 (1.20–2.90) | 1.60 (1.09–2.35) | 2.24 (1.42–3.55) |

| Unintentional injuries | 1.00 (ref) | 1.27 (0.91–1.77) | 1.18 (0.89–1.57) | 2.69 (2.04–3.56) |

| Suicide | 1.00 (ref) | 1.60 (1.06–2.40) | 1.08 (0.73–1.60) | 2.21 (1.50–3.24) |

| Other miscellaneous | 1.00 (ref) | 0.97 (0.65–1.43) | 1.46 (1.11–1.94) | 1.92 (1.35–2.71) |

| Avoidable causes | 1.00 (ref) | 1.12 (1.03–1.22) | 1.10 (1.03–1.18) | 1.33 (1.22–1.45) |

Hazard ratios estimated from fully adjusted Cox proportional hazard models on the overall sample of adults aged 18–82 years old at interview. N = 348 000 person-years. Models adjusted for household income, highest education in household, household type, housing tenure, acute care hospital admission in the past 2 years, number of self-reported chronic conditions, smoker status and past-year alcohol consumption history. Respondents’ sex, age at interview, history of hospital admission and self-reported chronic conditions were set as strata.

Interpretation

Drawing on a population-based sample of Canadian adults, we found a graded positive association between household food insecurity status and hazard of premature mortality. Severe food insecurity predicted higher mortality across all causes of death except cancers. Among adults who died prematurely, those experiencing severe food insecurity died at an age 9 years earlier than their food-secure counterparts. These findings are important for extending understanding of the health burden associated with food insecurity in Canada.

The graded association between food insecurity status and premature mortality — in particular, the strong association for severe food insecurity — is consistent with previous studies in the United States and Ontario.22,23 The significant correlations of all levels of food insecurity with potentially avoidable deaths imply that food-insecure adults benefit less from public health efforts to prevent and treat diseases and injuries than their food-secure counterparts. That severe food insecurity was associated with mortality hazard across circulatory-respiratory and metabolic-digestive diseases is in line with studies documenting greater incidence of these chronic conditions among food-insecure adults.6–10 The material deprivation and psychological distress typified by food insecurity can result in chronic inflammation, 39 nutritional vulnerability40 and medication nonadherence, 41 all of which hamper chronic disease management and increase the probability of adverse outcomes.

Our finding of higher risk of death from infectious-parasitic diseases across all levels of food insecurity is important for extending our understanding of the health risks associated with food insecurity in Canada. Although the underlying mechanisms still await elucidation, our finding is consistent with the existing evidence associating food insecurity with mortality among HIV-positive adults.24,25 Inadequate nutrition, depression, inability to follow therapeutic regimens and co-infection of hepatitis C are common factors inhibiting treatment of HIV/AIDS and precipitating death among food-insecure adults.11–13,42–48 More research is needed to understand the link between food insecurity and deaths by communicable diseases unrelated to HIV.

Although the link between food insecurity and mental health disorders is well documented in Canada,5,15,18–21 our finding that severe food insecurity was associated with unintentional injuries and suicides highlights the urgent need for more effective interventions. Given the prevalence of deaths related to drug poisoning in our sample (results not shown), our finding on unintentional injuries may partly reflect the link between food insecurity and substance use,49,50 which is often complicated by the co-existence of HIV infection and depression.51–53 The higher risk of death from suicides is consistent with Canadian studies documenting links between food insecurity and suicidal ideation and attempts.19–21 Suicide prevention needs to be prioritized for adults experiencing food insecurity.

Previous research has consistently documented an association between lower income and higher mortality in Canada,54,55 including greater mortality by unintentional injuries and suicides. 54,56 However, food insecurity and low income are inherently different measures of economic well-being, with the former capturing experience-based material hardship and the latter providing a relative measure of monetary resources. The markedly higher mortality hazard of severe food insecurity highlights the importance of policy interventions that protect households from extreme deprivation. In Canada, policies that improve the material resources of low-income households have been shown to strengthen food security and health.57–62 This body of evidence should inform future policy-making in Canada so that household food insecurity is more effectively addressed.

Limitations

We recognize the limitations of this study. First, multiple jurisdiction cycles were excluded from this study owing to missing food insecurity data, which limited the generalizability of our findings to adults with valid food security status. In addition, hospital admission records from Quebec and income data from 2017 were missing. However, sensitivity tests showed a limited effect from missing food insecurity, hospital admission and income. Second, our findings are correlational, not causal. The chronic conditions we controlled for were self-reported and limited in scope, with a reference period (previous 6 mo) that overlapped with the food insecurity measurement (previous 12 mo). Our adjustment for hospital admission provided a more objective indication of baseline health, but likely captured more severe health problems. Omitted variable bias remains possible: unobserved factors may have led to food insecurity and premature death simultaneously. Third, food insecurity was measured once per person in the CCHS, obscuring important information about change of food insecurity status over the follow-up period. Repeated measurement of food insecurity in a panel design would yield insight into hardship dynamics and help determine causality. Finally, the number of deaths by specific causes were relatively small, especially for communicable diseases and injuries. Replication studies using different population-based samples may help to validate our findings.

Conclusion

Our study marks an important step toward understanding the epidemiology of food insecurity and establishing this condition as an independent social determinant of health. Food insecurity status is linked to all-cause and cause-specific premature mortality among Canadian adults. Future studies need to clarify the mechanisms underlying the linkage between food insecurity and various causes of death. Adults from severely food-insecure households warrant greater attention from clinicians and policymakers due to their elevated risk of premature death.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the invaluable comments from the editor, the 2 anonymous referees, Judi Bartfeld and audience at the 2018 Canadian Research Data Centre Network conference. We thank analysts from the Statistics Canada Research Data Centre for the logistical support.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Valerie Tarasuk, Marcelo L. Urquia and Craig Gundersen contributed to the conception of the study. Valerie Tarasuk and Marcelo L. Urquia acquired the data. Fei Men and Valerie Tarasuk designed the study. Fei Men analyzed and interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. Valerie Tarasuk, Craig Gundersen and Marcelo L. Urquia contributed to data interpretation and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All of the authors gave final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: This study was supported by Canadian Institutes of Health Research grant PJT 153260, awarded to Valerie Tarasuk and Marcelo L. Urquia. The funder had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of data; or preparation, review, decision to submit for publication or approval of the manuscript.

Data sharing: Data for this study cannot be shared publicly because of the confidentiality agreement between Statistics Canada and respondents of the Canadian Community Health Survey. Data are available at the Statistics Canada Research Data Centre (contact via phone +1 905-525-9140 ext. 23661) for researchers who meet the criteria for access to confidential data.

References

- 1.Tarasuk V, Mitchell A, Dachner N. Household food insecurity in Canada, 2012. Toronto: Research to Identify Policy Options to Reduce Food Insecurity (PROOF); 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Household food insecurity in Canada. Toronto: PROOF, Department of Nutritional Sciences, University of Toronto; updated 2018 Feb. 22. Available: https://proof.utoronto.ca/food-insecurity/#2 (accessed 2019 June 25). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gundersen C, Ziliak JP. Food insecurity and health outcomes. Health Aff (Millwood) 2015;34:1830–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tarasuk V, Cheng J, de Oliveira C, et al. Association between household food insecurity and annual health care costs. CMAJ 2015;187:E429–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tarasuk V, Cheng J, Gundersen C, et al. The relation between food insecurity and mental health service utilization in Ontario. Can J Psychiatry 2018;63: 557–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gucciardi E, Vahabi M, Norris N, et al. The intersection between food insecurity and diabetes: a review. Curr Nutr Rep 2014;3:324–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gregory CA, Coleman-Jensen A. Food insecurity, chronic disease, and health among working-age adults, ERR-235. Washington (DC): U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berkowitz SA, Meigs JB, DeWalt D, et al. Material need insecurities, control of diabetes mellitus, and use of health care resources: results of the Measuring Economic Insecurity in Diabetes study. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:257–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seligman HK, Schillinger D. Hunger and socioeconomic disparities in chronic disease. N Engl J Med 2010;363:6–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laraia BA. Food insecurity and chronic disease. Adv Nutr 2013;4:203–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weiser SD, Young SL, Cohen CR, et al. Conceptual framework for understanding the bidirectional links between food insecurity and HIV/AIDS. Am J Clin Nutr 2011;94: 1729S–39S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anema A, Vogenthaler N, Frongillo EA, et al. Food insecurity and HIV/AIDS: current knowledge, gaps, and research priorities. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2009;6:224–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang EA, McGinnis KA, Fiellin DA, et al. VACS Project Team. Food insecurity is associated with poor virologic response among HIV-infected patients receiving antiretroviral medications. J Gen Intern Med 2011;26:1012–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palar K, Laraia B, Tsai AC, et al. Food insecurity is associated with HIV, sexually transmitted infections and drug use among men in the United States. AIDS 2016;30:1457–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tarasuk V, Mitchell A, McLaren L, et al. Chronic physical and mental health conditions among adults may increase vulnerability to household food insecurity. J Nutr 2013;143:1785–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Afulani PA, Coleman-Jensen A, Herman D. Food insecurity, mental health, and use of mental health services among nonelderly adults in the United States. J Hunger Environ Nutr 2018. October 29 [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1080/19320248.2018.1537868. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maynard M, Andrade L, Packull-McCormick S, et al. Food insecurity and mental health among females in high-income countries. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15:1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davison KM, Gondara L, Kaplan BJ. Food insecurity, poor diet quality, and suboptimal intakes of folate and iron are independently associated with perceived mental health in Canadian adults. Nutrients 2017;9:274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davison KM, Marshall-Fabien GL, Tecson A. Association of moderate and severe food insecurity with suicidal ideation in adults: national survey data from three Canadian provinces. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2015;50:963–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McIntyre L, Williams JV, Lavorato DH, et al. Depression and suicide ideation in late adolescence and early adulthood are an outcome of child hunger. J Affect Disord 2013;150:123–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hajizadeh M, Bombay A, Asada Y. Socioeconomic inequalities in psychological distress and suicidal behaviours among Indigenous peoples living off-reserve in Canada. CMAJ 2019;191:E325–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gundersen C, Tarasuk V, Cheng L, et al. Food insecurity status and mortality among adults in Ontario, Canada. PLoS One 2018;13:e0202642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walker RJ, Chawla A, Garacci E, et al. Assessing the relationship between food insecurity and mortality among US adults. Ann Epidemiol 2019;32:43–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anema A, Chan K, Chen Y, et al. Relationship between food insecurity and mortality among HIV-positive injection drug users receiving antiretroviral therapy in British Columbia, Canada. PLoS One 2013;8:e61277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weiser SD, Fernandes KA, Brandson EK, et al. The association between food insecurity and mortality among HIV-infected individuals on HAART. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2009;52:342–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Population health survey data linked to hospitalization, mortality, emergency department visit, cancers, and tax file: user guide. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2019. [Unpublished internal document. Available upon request.] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Canadian coding standards for version 2012 ICD-10-CA and CCI. Ottawa: Canadian Institute for Health Information; revised 2012. Available: https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/canadian_coding_standards_2012_e.pdf (accessed 2019 Mar. 18). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eyawo O, Franco-Villalobos C, Hull MW, et al. Comparative Outcomes And Service Utilization Trends (COAST) study. Changes in mortality rates and causes of death in a population-based cohort of persons living with and without HIV from 1996 to 2012. BMC Infect Dis 2017;17:174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gatov E, Rosella L, Chiu M, et al. Trends in standardized mortality among individuals with schizophrenia, 1993–2012: a population-based, repeated cross-sectional study. CMAJ 2017;189:E1177–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sanmartin C, Decady Y, Trudeau R, et al. Linking the Canadian Community Health Survey and the Canadian Mortality Database: an enhanced data source for the study of mortality. Health Rep 2016;27:10–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Summary report of the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) — Discharge Abstract Database (DAD) Record Linkage Study: user guide. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2012. [Unpublished internal document. Available upon request.] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Premature death. In: NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms. Bethesda (MD): Cancer Information Service; Available: www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/premature-death (accessed 2019 Dec. 19). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Table 39-10-0007-01: Life expectancy and other elements of the life table, Canada and provinces. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2018. Available: www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3910000701 (accessed 2019 Dec. 19). [Google Scholar]

- 34.List of conditions for potentially avoidable mortality and mortality from preventable and treatable causes indicators. Ottawa: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rutstein DD, Berenberg W, Chalmers TC, et al. Measuring the quality of medical care. A clinical method. N Engl J Med 1976;294:582–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.James PD, Wilkins R, Detsky AS, et al. Avoidable mortality by neighbourhood income in Canada: 25 years after the establishment of universal health insurance. J Epidemiol Community Health 2007;61:287–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bickel G, Nord M, Price C, et al. Guide to measuring household food security, revised 2000. Alexandria (VA): U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Canadian Community Health Survey, Cycle 2.2, Nutrition (2004): income-related household food security in Canada. Ottawa: Office of Nutrition Policy and Promotion, Health Products and Food Branch, Health Canada; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gowda C, Hadley C, Aiello AE. The association between food insecurity and inflammation in the US adult population. Am J Public Health 2012;102:1579–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kirkpatrick SI, Tarasuk V. Food insecurity is associated with nutrient inadequacies among Canadian adults and adolescents. J Nutr 2008;138:604–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Men F, Gundersen C, Urquia ML, et al. Prescription medication nonadherence associated with food insecurity: a population-based cross-sectional study. CMAJ Open 2019;7:E590–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Palar K, Frongillo EA, Escobar J, et al. Food insecurity, internalized stigma, and depressive symptoms among women living with HIV in the United States. AIDS Behav 2018;22:3869–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McKay FH, Lippi K, Dunn M. Investigating responses to food insecurity among HIV positive people in resource rich settings: a systematic review. J Community Health 2017;42:1062–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aibibula W, Cox J, Hamelin A-M, et al. Food insecurity and low CD4 count among HIV-infected people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Care 2016;28:1577–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aibibula W, Cox J, Hamelin A-M, et al. Association between food insecurity and HIV viral suppression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Behav 2017;21:754–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cox J, Hamelin A-M, McLinden T, et al. Canadian Co-infection Cohort Investigators. Food insecurity in HIV-hepatitis C virus co-infected individuals in Canada: the importance of co-morbidities. AIDS Behav 2017;21:792–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Young S, Wheeler AC, McCoy SI, et al. A review of the role of food insecurity in adherence to care and treatment among adult and pediatric populations living with HIV and AIDS. AIDS Behav 2014;18(Suppl 5):S505–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Singer AW, Weiser SD, McCoy SI. Does food insecurity undermine adherence to antiretroviral therapy? A systematic review. AIDS Behav 2015;19:1510–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Strike C, Rudzinski K, Patterson J, et al. Frequent food insecurity among injection drug users: correlates and concerns. BMC Public Health 2012;12:1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Whittle HJ, Sheira LA, Frongillo EA, et al. Longitudinal associations between food insecurity and substance use in a cohort of women with or at risk for HIV in the United States. Addiction 2019;114:127–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McLinden T, Moodie EEM, Hamelin A-M, et al. Injection drug use, unemployment, and severe food insecurity among HIV-HCV co-infected individuals: a mediation analysis. AIDS Behav 2017;21:3496–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McLinden T, Moodie EE, Harper S, et al. Injection drug use, food insecurity, and HIV-HCV co-infection: a longitudinal cohort analysis. AIDS Care 2018;30:1322–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Davey-Rothwell MA, Flamm LJ, Kassa HT, et al. Food insecurity and depressive symptoms: comparison of drug using and nondrug-using women at risk for HIV. J Community Psychol 2014;42:469–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tjepkema M, Wilkins R, Long A. Cause-specific mortality by income adequacy in Canada: a 16-year follow-up study. Health Rep 2013;24:14–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Khan AM, Urquia M, Kornas K, et al. Socioeconomic gradients in all-cause, premature and avoidable mortality among immigrants and long-term residents using linked death records in Ontario, Canada. J Epidemiol Community Health 2017;71:625–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zandy M, Zhang LR, Kao D, et al. Area-based socioeconomic disparities in mortality due to unintentional injury and youth suicide in British Columbia, 2009–2013. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can 2019;39:35–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McIntyre L, Dutton DJ, Kwok C, et al. Reduction of food insecurity in low-income Canadian seniors as a likely impact of a guaranteed annual income. Can Public Policy 2016;42:274–86. 10.3138/cpp.2015-069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li N, Dachner N, Tarasuk V. The impact of changes in social policies on household food insecurity in British Columbia, 2005–2012. Prev Med 2016;93:151–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Loopstra R, Dachner N, Tarasuk V. An exploration of the unprecedented decline in the prevalence of household food insecurity in Newfoundland and Labrador, 2007–2012. Can Public Policy 2015;41:191–206. 10.3138/cpp.2014-080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tarasuk V, Li N, Dachner N, et al. Household food insecurity in Ontario during a period of poverty reduction, 2005–2014. Can Public Policy 2019;45:93–104. 10.3138/cpp.2018-054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ionescu-Ittu R, Glymour MM, Kaufman JS. A difference-in-differences approach to estimate the effect of income-supplementation on food insecurity. Prev Med 2015;70:108–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.McIntyre L, Kwok C, Emery JC, et al. Impact of a guaranteed annual income program on Canadian seniors’ physical, mental and functional health. Can J Public Health 2016;107:e176–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]