KEY POINTS

“Health in All Policies” (HiAP) is an approach that systematically considers the health and social implications of policies contemplated by all sectors of government — aiming for synergistic benefits and to minimize social and health-related harms.

Health in All Policies is a critical policy lever, because many of the drivers for health outcomes are beyond the reach of the health sector — and because initiatives that increase health and health equity often pay for themselves through better productivity and higher tax revenues.

Noncommunicable chronic diseases, mental health issues and the health inequities faced by Indigenous Peoples in Canada exemplify key challenges for Canadians that could be successfully addressed by the HiAP approach.

Although there are substantial challenges to be overcome, including political will and data inadequacies, a pan-Canadian action plan on HiAP would help to promote health and health equity for Canadians.

Canadians benefit from a well-established set of social rights to education, social services, old-age security and health care — among others. Although provinces and territories may decide how a particular benefit is distributed or a service is provided, all Canadians can expect to be protected, to an extent, against the adverse effects of sickness, injury, unemployment, disability or old age.

Canadian social programs have changed relatively little over the decades since their establishment, despite substantial transformations in the social and economic fabric of the country. Some have argued that Canadian medicare1 suffers a relative inertia in the face of broader social trends, making it difficult to change or build on.2 Since medicare was established, Canadians have experienced increased migration and cultural diversity,3 the transformation of family structures and gender roles,4 globalization, substantial changes to the economy5 and, in recent years, the growing threats of climate change. Each of these factors should have prompted program adjustments and shifts in policy. Yet, medicare today is fundamentally similar to the program that was implemented in 1968. Despite a massive increase in public funding for health care over decades, Canada’s health system performance compared with other wealthy nations has steadily declined6 and the health of Canadians has improved more slowly than that of residents of other wealthy countries, with evidence emerging that health equity is now decreasing.7

Improving health and health equity is a complex endeavour, and it is unrealistic to think that any single change could achieve this objective. However, introduction of the single intervention that is a “Health in All Policies” (HiAP) action plan in Canada would strongly boost progress toward a socially equitable and healthy future for Canadians. Although Canada has a long history of using progressive policy to promote health and equity (e.g., the 1974 Lalonde report,8 the 1986 Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion9 and, indeed, the ambitious vision for medicare), in recent years, Canadian leadership in broad health policy has stalled. The sustainability of our health systems and the health of Canadians have both suffered as a result. Despite our commitments at the Pan American Health Organization Directing Council, which in 2014 outlined its Plan of Action on Health in All Policies,10 Canada does not currently have a meaningful HiAP program at the federal level — or in most provinces. Implementing such a program at the federal level would be a major step toward health promotion and equity for Canadians.

What is HiAP?

Health in All Policies is an approach that systematically considers the health and social implications of policies contemplated by all sectors of government — aiming for synergistic benefits and to minimize social and health-related harms.11 Health in All Policies is a critical policy lever because many of the drivers for health outcomes — including risk factors for disease, inequitable access to care, and the socioeconomic and environmental determinants of health and wellness — are beyond the reach of the health sector.12

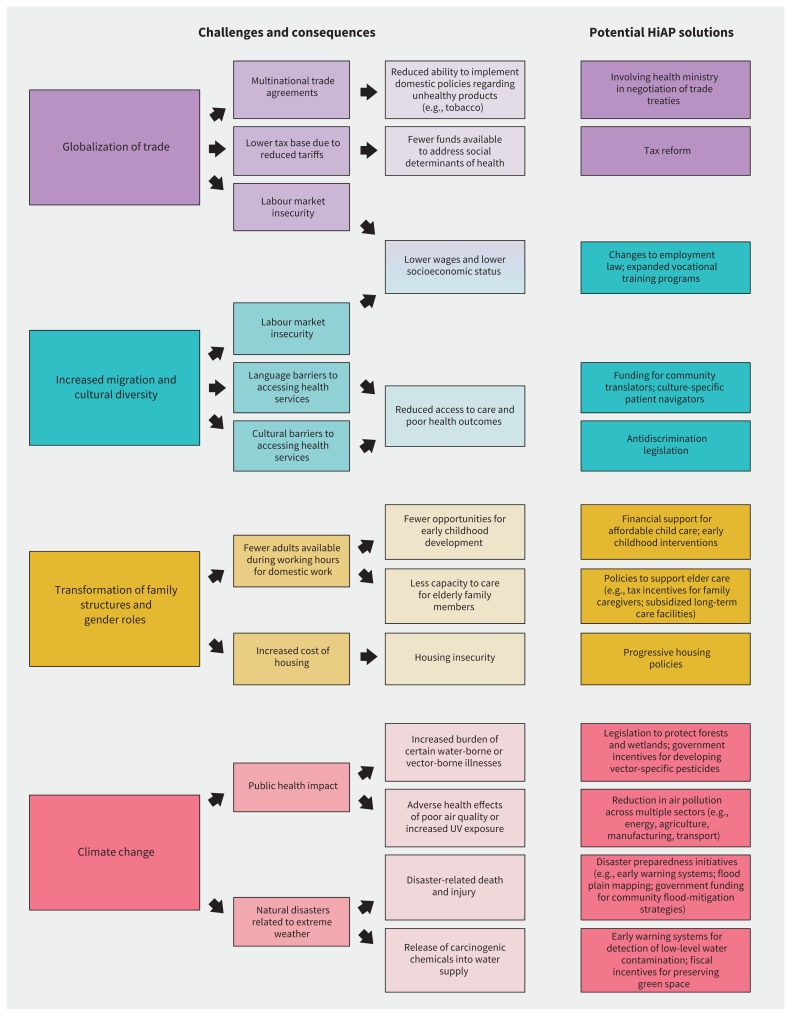

Thoughtful application of HiAP focuses on improving population health and health equity by ensuring that all government departments and agencies assess how their policies will affect the upstream drivers of health and social conditions — through direct consequences (e.g., changes to tax policy that promote affordable housing) but also through unintended but potentially foreseeable consequences of policies that are not obviously health related13 (e.g., zoning regulations that promote urban sprawl and thus increase consumption of fossil fuels and pollution). A fundamental aspect of HiAP is careful attention to root causes of poor health, such as weak physical infrastructure, lack of or inadequate supply of clean water and waste management, lack of social protection, and poor accessibility to services and support, including health care. Figure 114,15 shows 4 broad issues that affect population health, the specific challenges they create and examples of how cross-ministerial policy-making could help to improve health and health equity in response to these issues.

Figure 1:

Four broad issues that affect population health, the challenges they create and potential HiAP solutions. The suggested policy responses to climate change are adapted from Watts and colleagues14 and the National Institute of Environmental Health Science.15 Note: HiAP = Health in All Policies, UV = ultraviolet.

What HiAP initiatives have other countries tried or committed to?

There are many examples of how HiAP and intersectoral action have been used to boost the health of populations, as has been described comprehensively elsewhere.16–18 Noteworthy examples range from programs to address illness among migrants in Australia and internal migrants in China, workplace injuries in the United Kingdom and in Cambodia, malnutrition among children in India and mental health in Finland.19–26 The Finnish government espoused this approach during its presidency of the Council of the European Union in 2006, given its extensive experience with the HiAP approach. The World Health Assembly adopted a resolution in June 2015 that committed all member states (including Canada) to using an HiAP approach to improve health and health equity. Boxes 1 and 2 describe successful HiAP programs in Australia and China, respectively.

Box 1:

Case study 1 — South Australia27–29

Beginning in 2007, South Australia designed and systematically implemented an HiAP initiative based on the use of health-lens analysis to identify co-benefits of action on the social determinants of health for participating sectors (i.e., a win–win approach). Key areas of focus for the initiative included water security, urban planning, determinants of obesity, education and transport regulation. The overarching goal was to improve population health despite the twin challenges of rising chronic disease and an aging population.

Attempts to build relationships and mutual understanding between actors in different sectors were an essential part of the initiative — including formal intersectoral partnerships, training to foster understanding of the social determinants of health, and cross-ministerial briefings on key policy initiatives. These efforts were supported by high-level political commitment and investment of adequate financial and human resources. The initiative also included an embedded evaluation strategy that sought feedback from public servants within and beyond the health sectors.

In a 5-year study from 2012 to 2016, data were collected from 144 key informant interviews and surveys of more than 400 public servants. These data were used to inform a program-theory–based evaluation of the HiAP initiative. Although direct markers of population health were not assessed, the evaluation suggested that the initiative led to actions and processes across sectors that should lead to improved population health. For example, actions aimed at increasing the proportion of residents at healthy weight included the following: multisectoral action to increase opportunities for active modes of transportation, creation of community vegetable gardens in public housing areas, renewal efforts to make public parks more appealing, and work to provide healthier food to prisoners. Public servants who participated in the evaluation generally reported a positive experience with HiAP, reported a better appreciation of how their ministry’s actions could favourably influence health, and indicated that attempts to prioritize action on the social determinants of health across sectors had been moderately successful.

The overall cost of the HiAP initiative was less than 0.01% of the annual health budget for South Australia.

Note: HiAP = Health in All Policies.

Box 2:

Case study 2 — HiAP implementation and building healthy counties and districts in China30,31

After a 2014 commitment for China to host the World Health Organization 9th Global Conference on Health Promotion, HiAP implementation was scaled up by the government. President Xi Jinping emphasized the importance of health for prosperous growth and sustainable development, and of the inclusion of health in all policy-making. Key activities were as follows: including HiAP in the Healthy China 2030 Plan, publicizing the importance of health for growth and development, creating an organizational structure at all levels of government to facilitate HiAP, building technical capacity for cross-sectoral initiatives, and establishing a health-impact assessment system.

These actions were supplemented by initiatives that communicated the value of HiAP to party members, government leaders and senior officials as well as training courses on HiAP at the provincial level, especially in rural counties and urban districts. Local government was identified as the key player for HiAP implementation, with technical support from the health authority.

Building healthy counties and districts was chosen as a critical pathway for achieving Healthy China 2030 and as one of the best platforms for HiAP implementation. Pilot projects were initiated in 2014, with clear indicators and assessment criteria in 6 areas, including a set of maximum scores for each of the 6 areas. The areas comprise healthy public policies, healthy settings, healthy environments, healthy people, and healthy culture, as well as HiAP management practices. Key priorities for action for HiAP were to prevent and control communicable and noncommunicable diseases, and to promote healthy living, maternal and child health, healthy aging and environmental health.

By mid-2019, activities had extended to 692 national and provincial bodies, comprising 495 counties and districts in 12 provinces and 197 national pilot projects. Pilot projects addressed a range of topics including noncommunicable disease and environmental health, and are highly valued by party and government leaders and officials. Cooperation between sectors during the pilot projects was generally evaluated as good, and progress was reported in all 6 assessment areas. Activities had extended to 24.3% of the counties in the country by mid-2019, including a total population of more than 34 million people, which exceeded the initial goal of 20% by 2020. Health impact assessments were also widely conducted (more than 700 from 2015 to 2017).

Although no data on definitive health outcomes are yet available, HiAP implementation has become widespread, comprehensive and systematic in China, driven by strong political commitment, stable funding, and considerable support from the national health commission and local government.

Note: HiAP = Health in All Policies.

How could HiAP benefit Canadians?

Two examples of how targeted intersectoral action has yielded health benefits for Canadians are declining death and disability from traffic accidents32 (driven by better road design, effective prevention of impaired driving and tougher transport regulation), and a lower prevalence of smoking33 (from excise duties and other tobacco-control measures). These measures are also considered to have saved money while reducing morbidity and mortality. But there are many more opportunities for coordinated intersectoral action to improve health and health equity in Canada, which a purposive national action plan on HiAP could tackle effectively.

Tackling the rise in noncommunicable diseases

Noncommunicable diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes and kidney disease, are the leading causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide,34 and are placing economic pressure on governments everywhere. However, most public expenditures on noncommunicable diseases in Canada relate to medical treatment of acute and chronic complications rather than prevention of root causes.35,36 A preventive approach would require coordinated action outside the health sector to address risk factors as diverse as climate change, sedentary lifestyle and hazardous working environments, as well as to promote reduced consumption of alcohol, tobacco and excess sodium.37 An effective HiAP plan would also address risk factors related to noncommunicable diseases that affect multiple generations, such as low literacy or unhealthy diet.

Promoting mental health

Mental health conditions are a subset of noncommunicable diseases that have been particularly neglected worldwide despite posing a high health burden. Gaps are especially pronounced for prevention,38 but are also reflected by lack of access to early intervention and a failure to ensure adequate treatment for established disease.39 A large body of observational evidence links low socioeconomic status, poor social capital, and lack of individual resilience to increased risk of mental illness, and there is some evidence that certain interventions aimed at mitigating these risks may improve outcomes.18,40–43 Accordingly, enthusiasm for broader action on the social determinants of mental health has grown,44,45 but there is no plan to make the requisite cross-ministerial and cross-agency investments on behalf of Canadians.46

Addressing health inequities for Indigenous Peoples

Correcting the unconscionable health inequities observed among Indigenous Peoples in Canada will require comprehensively redressing harms and promoting Indigenous rights, in parallel with purposive action to address social determinants that undermine the health of Indigenous Peoples.47 A blueprint already exists to improve health inequities among Indigenous Peoples — the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s 94 Calls to Action include 7 recommendations aimed specifically at the health sector, but also multiple recommendations targeting child welfare, education, the justice system, equitable access to government services, and opportunities for healthy lifestyles. 48 Delivering on these calls will require coordinated investments across sectors — exemplifying the opportunities that an effective national HiAP plan would offer to Canadians — but, if Indigenous-led, could effect substantial health gains for Indigenous Peoples.

How can barriers to implementing HiAP in Canada be overcome?

Skeptics may argue that HiAP is unrealistic: that the legal structures, governance frameworks, and underlying processes for supporting collaboration across sectors generally do not exist, that few governments have the political will to implement such an approach, and that too many barriers exist to implementation even were the political will to exist.18 It is undeniable that more has been written about the potential benefits of HiAP than about how to implement HiAP in practice.49 In addition, there is some evidence that successful implementation strategies may be at least partially context dependent,50 meaning that strategies which worked elsewhere would likely require thoughtful adaptation before their implementation in Canada. Below we present 4 potential barriers, as well as some possible solutions.

Balancing policy objectives across sectors is challenging

When politicians perceive that policies aimed at promoting health and equity may stifle economic growth or divert resources from another sector, there may be little appetite for HiAP. However, most, if not all, initiatives aimed at shaping the governance of economic and social life — from the very first programs of social assistance in the early 1920s to the sophisticated tools used today to smooth out the business cycle51 — have required cross-sectoral compromise and understanding. Health in All Policies is arguably an approach that is similar in spirit and scope to other instruments of social assistance and economic governance used by the Canadian welfare state since its inception (e.g., federal social and health transfers or even equalization payments).

Furthermore, comprehensive toolkits are available to support policy-makers in implementing and sustaining HiAP programs, such as the 2015 World Health Organization (WHO) training manual. 52 Toolkits help to foster understanding that HiAP can drive both health and prosperity rather than forcing a trade-off between the two,53 for example, by improving productivity, increasing tax revenues, and decreasing the number of people receiving means-tested social benefits. In England, a 2012 analysis by scholars at University College London’s Institute of Health Equity estimated that continued inaction on existing health inequalities would result in productivity losses of £31–33 billion, reduced tax revenue and higher welfare payments of £20–32 billion and additional health care costs in excess of £5.5 billion per year.54 Similarly, a 2012 analysis by the National Centre for Social and Economic Modelling in Australia that estimated the costs of not addressing social determinants of health found that if relevant recommendations from WHO were adopted, $8 billion extra earnings could be generated, $4 billion in welfare support payments could be saved annually, and $2.3 billion could be saved from fewer hospital admissions per year.55

It is also worth noting that, since HiAP encourages a “big picture” view, it offers an opportunity to facilitate redistribution of resources that are currently concentrated in the delivery of acute health care toward more economically efficient investments in the social determinants of health.36 The idea that addressing root causes could reduce net expenditures on health may also provide an incentive for nonhealth sectors to engage on HiAP.

Health care is not always at the top of the list of governments’ competing priorities

Governments must balance multiple objectives, and health and equity are not always at the top of the list. However, many issues that deeply concern politicians, such as employment levels, the safety of our communities, or the national distribution of wealth, have a direct impact on health and vice versa. Routinely requiring a health impact assessment for new policies contemplated by nonhealth ministries may help to emphasize the links between apparently disconnected public policies from disparate ministries56 — and clarify that competition between sectors is less of a problem than it might seem. There is some evidence that routine health impact assessments may be better accepted initially by sectors in which environmental impact assessments are frequently required.49

Data are not available to support the implementation of HiAP

Canadian health data are among the best in the world, but the absence of a broader national data strategy hampers the implementation of HiAP. Not only is it still often difficult to access the key national indicators generated by Canada’s health systems, it is nearly impossible to connect these data to the data generated in other sectors of social and economic relevance (including growing private sector data holdings) to inform policy action, according to a 2018 external review of the Pan-Canadian Health Organizations.57 One of the first steps toward HiAP is to address the obstacles that preclude harnessing this rich trove of data for the public good — from antiquated privacy legislation to a relative lack of data literacy within governments and public administrations. The availability of good, accessible, linked data could catalyze the development and collection of metrics to measure progress on HiAP (e.g., process-based metrics that capture the extent of cooperation between sectors) as well as on the ultimate goals of better health and health equity.58 Health services researchers would need to work with policy-makers to develop critical methods, metrics and surveillance systems that can be used to track progress on HiAP through health impact assessments.

Health in All Policies requires a different kind of politics

Once initiated, an HiAP approach would need to be sustained by changes in government and associated changes to the structure and leadership of government ministries. The short-term nature of the electoral cycle makes this difficult, even if the challenges above are overcome. Sustained action on HiAP would require achieving a culture change within government that helps leaders to “rise above their own interests, consider shared goals, and commit to steps for reaching them.”56 This is perhaps the greatest obstacle to successfully implementing a national Canadian HiAP initiative.

Why now?

In Canada and other wealthy nations, trust in political institutions is waning, with citizens increasingly skeptical about the intentions of the political and wealthy business “elite.”59 Accordingly, an integrated and comprehensive approach to social policy, adapted to the economic reality arising from globalization and the digital revolution might help to renew the social contract as did the welfare state created as part of the post–World War II reconstruction. The Canadian government has not carried out a systematic and comprehensive review of its social programs for decades. Federal commissions and committees traditionally look at issues on a sector-by-sector basis and so health-focused reviews routinely ignore relevant programs, such as old-age pensions or employment insurance, while environmental reviews pay limited attention to outcomes that are not easily measurable, such as mental health. An HiAP lens would support our federal authorities to take a system-wide approach, conducive to a radical update and modernization of Canadian health and social policy.

Furthermore, an effective response to climate change will require intersectional policy intervention on an unprecedented scale60,61 (Figure 1), which in turn will have an impact on health. Failure to act quickly on climate change will harm the credibility of political leaders. A strong HiAP approach would enable effective coordination of policies from different sectors, including environmental and health policies.

Who should be responsible for implementing HiAP?

It is possible to imagine a pan-Canadian approach to implementation, based on our long and positive experience with federalism and intersectoral cooperation. Implementation could begin in a circumscribed way, for example, by being used to address 1 of the 3 health challenges described above; the recommendations of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission are an especially attractive starting point. This would require leadership from the federal government49 in collaboration with Indigenous Peoples, an explicit focus on the so-called win–win approach (as opposed to simply raising awareness about HiAP or unilaterally imposing health targets on nonhealth sectors),62 and consideration of how to link provincial initiatives with relevant actors at the regional or local level.50 A pan-Canadian agreement to routinely conduct health impact assessments for relevant large federal and provincial policy initiatives might be a concrete first step toward a national HiAP strategy.

Conclusion

Health in All Policies is a concept that fits well with Canadian values. Moreover, implementation of HiAP in diverse settings around the world has shown that the approach has great potential to improve population health and health equity. A commitment to a national HiAP action plan in Canada, designed and executed in partnership with the provinces and territories, could boost health care improvement, promote continuity in successive governments’ decisions and adapt Canadians’ social rights to the needs of this century. Clinicians, in their roles as community leaders, can advocate for the importance of HiAP in addressing the social determinants of health while delivering wide-ranging benefits beyond the health sector, and teach the potential value of HiAP to undergraduate and graduate physicians in training.

Footnotes

Competing interests: Marcello Tonelli received grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (paid to institution). Pierre-Gerlier Forest provides advice to Norton Rose Fulbright LLP on health policy issues as part of a retainer agreement and has received consulting fees from Innovative Medicines Canada in that context. No other competing interests were declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Marcello Tonelli was responsible for conceptualization and writing the original draft. Kwok-Cho Tang contributed to reviewing and editing. Pierre-Gerlier Forest was responsible for conceptualization, and reviewing and editing. All of the authors gave final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

References

- 1.Canada’s health care system. Ottawa: Health Canada; 2018. Available: www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/health-care-system/reports-publications/health-care-system/canada.html (accessed 2019 Sept. 17). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lazar H, Lavis J, Forest PG, et al. Paradigm freeze: why it is so hard to reform health care in Canada. Montréal, Kingston (ON): McGill–Queen’s University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Immigration and ethnocultural diversity highlight tables, 2016 Census. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2018. Available: www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/hlt-fst/imm/index-eng.cfm (accessed 2019 Sept. 17). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luxton M. Changing families, new understandings. Ottawa: The Vanier Institute of the Family; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donaghy G, Roussel S. Canada and the challenges of globalization: A glass half empty, or half full? Can Foreign Policy J 2018;24:253–9. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Najafizada SAM, Sivanandan T, Hogan K, et al. Ranked performance of Canada’s health system on the international stage: a scoping review. Healthc Policy 2017;13:59–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin D, Miller AP, Quesnel-Vallee A, et al. Canada’s universal health-care system: achieving its potential. Lancet 2018;391:1718–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lalonde M. A new perspective on the health of Canadians. Ottawa: Minister of Supply and Services Canada;1974. [Google Scholar]

- 9.The Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. First International Conference on Health Promotion Ottawa; 1986 Nov. 21 Geneva: World Health Organization; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pan American Health Organization, World Health Organization. Plan of action on Health in all Policies. Paper presented at the 53rd Directing Council, 66th Session of the Regional Committee of WHO for the Americas; 2014 Sept. 29–Oct. 3; Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Health in All Policies (HiAP) framework for country action. Health Promot Int 2014;29(Suppl 1): i19–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marmot M. Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet 2005;365: 1099–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kershaw P. The need for health in all policies in Canada. CMAJ 2018;190:E64–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Watts N, Adger WN, Agnolucci P, et al. Health and climate change: policy responses to protect public health. Lancet 2015;386:1861–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Climate and human health. Rockville (MD): National Institute of Environmental Health Science; 2018. Available: www.niehs.nih.gov/research/programs/geh/climatechange/index.cfm (accessed 2019 Apr. 30). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moving towards health in all policies: a compilation of experience from Africa, South-East Asia and the Western Pacific.Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/105528 (accessed 2019 Oct. 8). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rechel B, McKee M, editors. Facets of public health in Europe. Geneva: World Health Organization on behalf of the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies; 2014. Available: www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/271074/Facets-of-Public-Health-in-Europe.pdf?ua=1 (accessed 2019 Oct. 8). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leppo K, Ollila E, Peña S, et al., editors. Health in All Policies: seizing opportunities, implementing policies. Helsinki: Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, Finland; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leppo K, Ollila E, Peña S, et al., editors. Health in All Policies: seizing opportunities, implementing policies. Helsinki: Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, Finland;2013:52. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Workplace fatalities and injuries statistics in the EU: European comparisons — summary of UK performance. Bootle (UK): Health and Safety Executive; 2018. Available: www.hse.gov.uk/statistics/european (accessed 2019 Sept. 25). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Multicultural NSW Legislation Amendment Act 2014. Government of New South Wales, Australia: 2014. Available: https://multicultural.nsw.gov.au/about_us/about_mnsw (accessed 2019 Sept. 20). [Google Scholar]

- 22.The government response to the triennial review of the Health and Safety Executive. London (UK): Department for Work and Pensions; 2014. Available: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/323221/govt-resp-triennial-review-hse.pdf (accessed 2019 Sept. 25). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Terms of reference: independent mid-term evaluation of Better Factories Cambodia Programme Phase III. International Labour Organization and the International Finance Corporation Better Work Programme; 2018. Available: www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_mas/---eval/documents/publication/wcms_616058.pdf (accessed 2019 Sept. 25).

- 24.Leppo K, Ollila E, Peña S, et al., editors. Health in All Policies: seizing opportunities, implementing policies. Helsinki: Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, Finland;2013:136. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leppo K, Ollila E, Peña S, et al., editors. Health in All Policies: seizing opportunities, implementing policies. Helsinki: Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, Finland;2013:189. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leppo K, Ollila E, Peña S, et al., editors. Health in All Policies: seizing opportunities, implementing policies. Helsinki: Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, Finland; 2013:172. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baum F, Delany-Crowe T, MacDougall C, et al. To what extent can the activities of the South Australian Health in All Policies initiative be linked to population health outcomes using a program theory-based evaluation? BMC Public Health 2019;19:88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.South Australian Health in All Policies initiative: case study. Adelaide: Government of South Australia; 2013. Available: www.sahealth.sa.gov.au/wps/wcm/connect/f31235004fe12f72b7def7f2d1e85ff8/SA%2BHiAP%2BInitiative%2BCase%2BStudy-PH%2526CS-HiAP-20130604.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CACHE=NONE&CONTENTCACHE=NONE (accessed 2019 Sept. 18). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Delany T, Lawless A, Baum F, et al. Health in All Policies in South Australia: What has supported early implementation? Health Promot Int 2016;31:888–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang C, Gong P. Healthy China: from words to actions. Lancet Public Health 2019;4:e438–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lu Y. Seminar on Healthy China 2030 and building healthy counties and districts [in Chinese]. Beijing: Health Promotion Office, Chinese Centre for Health Education; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Canada’s road safety strategy 2025. Ottawa: Canadian Council of Motor Transportation Administrators; 2016. Available: http://roadsafetystrategy.ca/files/RSS-2025-Report-January-2016-with%20cover.pdf (accessed 2019 Dec. 23). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dobrescu A, Bhandari A, Sutherland G, et al. The costs of tobacco use in Canada, 2012. Ottawa: The Conference Board of Canada; 2017. Available: www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/documents/services/publications/healthy-living/costs-tobacco-use-canada-2012/Costs-of-Tobacco-Use-in-Canada-2012-eng.pdf (accessed 2019 Dec. 23). [Google Scholar]

- 34.GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017 [published erratum in Lancet 2019;393:e44]. Lancet 2018;392:1789–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.National health expenditure trends, 1975 to 2019. Ottawa: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dutton DJ, Forest PG, Kneebone RD, et al. Effect of provincial spending on social services and health care on health outcomes in Canada: an observational longitudinal study. CMAJ 2018;190:E66–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Global action plan for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases 2013–2020. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ngo VK, Rubinstein A, Ganju V, et al. Grand challenges: integrating mental health care into the non-communicable disease agenda. PLoS Med 2013;10: e1001443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sunderland A, Findlay LC. Perceived need for mental health care in Canada: results from the 2012 Canadian Community Health Survey-Mental Health. Health Rep 2013;24:3–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mantoura P, Roberge MC, Fournier L. A framework to support action in population mental health [article in French]. Sante Ment Que 2017;42:105–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lund C, Brooke-Sumner C, Baingana F, et al. Social determinants of mental disorders and the Sustainable Development Goals: a systematic review of reviews. Lancet Psychiatry 2018;5:357–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Public Health England, UCL Institute of Health Equity. Psychosocial pathways and health outcomes: informing action on health inequalities. London (UK): Public Health England;2017. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Keleher H, Armstrong R. Evidence-based mental health promotion resource. Melbourne (AU): Department of Human Services and VicHealth; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Advancing the mental health strategy for Canada: a framework for action (2017–2022). Ottawa: Mental Health Commission of Canada; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Comprehensive mental health action plan 2013–2020. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. Available: http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA66/A66_R8-en.pdf (accessed 2019 Nov. 26). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mental Health Commission of Canada. Strengthening the case for investing in canada’s mental health system: economic considerations. Ottawa: Mental Health Commission of Canada;2017. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Greenwood M, de Leeuw S, Lindsay N. Challenges in health equity for Indigenous peoples in Canada. Lancet 2018;391:1645–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: calls to action. Winnipeg: Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada; 2015. Available: http://trc.ca/assets/pdf/Calls_to_Action_English2.pdf (accessed 2019 Apr. 30). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shankardass K, Renahy E, Muntaner C, et al. Strengthening the implementation of Health in All Policies: a methodology for realist explanatory case studies. Health Policy Plan 2015;30:462–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guglielmin M, Muntaner C, O’Campo P, et al. A scoping review of the implementation of health in all policies at the local level. Health Policy 2018;122: 284–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Garland D. The welfare state: a very short introduction. Oxford (UK): Oxford University Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Health in all policies: training manual.Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 53.de Leeuw E. Engagement of sectors other than health in integrated health governance, policy, and action. Annu Rev Public Health 2017;38:329–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.The impact of the economic downturn and policy changes on health inequalities in London. London (UK): UCL Institute of Health Equity; 2012. Available: www.instituteofhealthequity.org/resources-reports/the-impact-of-the-economic-downturn-and-policy-changes-on-health-inequalities-in-london/the-impact-of-economic-downturn.pdf (accessed 2019 Sept. 25). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brown L, Thurecht L, Nepal B. The cost of inaction on the social determinants of health. Canberra (AU): Catholic Health Australia; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Greaves LJ, Bialystok LR. Health in All Policies — All talk and little action? Can J Public Health 2011;102:407–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Forest P, Martin D. Fit for purpose: findings and recommendations of the external review of the pan-Canadian health organizations. Ottawa: Health Canada; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bauman AE, King L, Nutbeam D. Rethinking the evaluation and measurement of health in all policies. Health Promot Int 2014;29(Suppl 1):i143–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Midweek podcast: Canadians’ trust in political institutions is dwindling, says survey. CBC Radio 2019. May 1 Available: www.cbc.ca/radio/thehouse/midweek-podcast-canadians-trust-in-political-institutions-is-dwindling-says-survey-1.5118356 (accessed 2019 Oct. 8).

- 60.Haines A, Ebi K. The imperative for climate action to protect health. N Engl J Med 2019;380:263–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Patz JA, Thomson MC. Climate change and health: moving from theory to practice. PLoS Med 2018;15:e1002628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Molnar A, Renahy E, O’Campo P, et al. Using win–win strategies to implement Health in All Policies: a cross-case analysis. PLoS One 2016;11:e0147003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]