Abstract

Relatively little is known about the role of sponge microbiomes in the Antarctic marine environment, where sponges may dominate the benthic landscape. Specifically, we understand little about how taxonomic and functional diversity contributes to the symbiotic lifestyle and aids in nutrient cycling. Here we use functional metagenomics to investigate the community composition and metabolic potential of microbiomes from two abundant Antarctic sponges, Leucetta antarctica and Myxilla sp. Genomic and taxonomic analyses show that both sponges harbor a distinct microbial community with high fungal abundance, which differs from the surrounding seawater. Functional analyses reveal both sponge-associated microbial communities are enriched in functions related to the symbiotic lifestyle (e.g., CRISPR system, Eukaryotic-like proteins, and transposases), and in functions important for nutrient cycling. Both sponge microbiomes possessed genes necessary to perform processes important to nitrogen cycling (i.e., ammonia oxidation, nitrite oxidation, and denitrification), and carbon fixation. The latter indicates that Antarctic sponge microorganisms prefer light-independent pathways for CO2 fixation mediated by chemoautotrophic microorganisms. Together, these results show how the unique metabolic potential of two Antarctic sponge microbiomes help these sponge holobionts survive in these inhospitable environments, and contribute to major nutrient cycles of these ecosystems.

Subject terms: Water microbiology, Metagenomics, Microbial ecology, Microbiome

Introduction

The sponge holobiont— or marine sponge-microorganisms assemblage–represents a complex symbiotic relationship that has emerged as a key model for microbe-host interactions1. This is due, in part, to the ancient origin of the sponge in the metazoan phylogeny2. Recently, metagenomic, metatranscriptomic and metaproteomic studies have provided new insights into the functional genes of sponge microorganisms, and a new understanding of the intricate metabolic connections between sponges and their microbial assemblages. From temperate and tropical systems, we have learned that bacteria in sponges are abundant and highly diverse3. Bacterial densities may exceed 109 microbial cells per cm3 of sponge tissue4, and a single sponge species may harbor as many different taxonomic units as seawater5. While the species-specific assemblages found in sponges differ from the surrounding seawater3, like in other microbiomes, they are described by distribution curves with a few, dominant taxonomic units followed by a long tail of rare species6,7.

Among distantly related sponges from temperate and tropical environments, different assemblages of associated microorganisms perform similar functions8,9. Thus, as in other symbiosis models, the microbiomes of sponges may share a set of core functional genes rather than a common set of taxa10–12. These microbial assemblages display a series of molecular adaptations to the symbiotic lifestyle, establishing a functional relationship with the host. Specific molecular determinants of the host-symbiont interaction may include Eukaryotic-like protein domains (ELPs) in the form of proteins with repeated domains (e.g., ankyrin (ARP), tetratricopeptide (TPR), leucine-rich repeats (LRR)), mobile genetic elements (MGEs), and genes related to protection and the stress response (e.g., stress proteins, restriction modification (R-M), toxin-antitoxin (T-A) systems, and clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPRs))9,13. Together, these molecular determinants provide a suite of molecular and physiological adaptations that link the microorganisms to their sponge hosts. They may also facilitate microbial survival within the sponge, and/or mediate direct metabolic interactions13,14.

Further elucidating the nature of sponge holobionts is fundamental because they provide habitat for a wide range of animals, and modify the major nutrient cycles of marine ecosystems (i.e., carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus)15–21. Sponge holobionts couple the benthic and pelagic zones through filter feeding22, and as observed in coral reef ecosystems, may canalize the transfer of DOM to higher trophic levels via the existence of a “sponge-loop”23,24. Understanding the nature of sponge holobionts in the extreme environment of Antarctica is particularly important since they occupy up to 80% of the benthos and are considered key ecosystem-engineers25,26.

The first study about Antarctic sponge bacterial communities using molecular approaches by Webster et al. (2004) found that a significant portion of the retrieved diversity was sponge-specific, similar to other marine environments27. But a more recent high-throughput sequencing approach targeting Bacteria, Archaea and Eukarya, in eight Antarctic sponge holobionts (Myxilla sp., Clathria sp., Kirkpatrickia variolosa, Hymeniacidon sp., Leucetta antarctica, Haliclona, sp., Megaciella annectens and an undetermined Demospongiae), found the microbiomes of Antarctic sponges to be quite different from those of tropical and temperate sponges28. However, little is known about the functional gene repertoires of sponge microbiomes from Antarctica, their roles in the survival of the sponge holobiont, and their contributions to the cycling of major elements in Antarctic marine ecosystems. So, here we characterize the community composition and metabolic potential of microbiomes from two of the more abundant Antarctic sponges, Myxilla sp. and Leucetta antarctica, using metagenomic analyses. We aim to describe the genomic composition of these microbial assemblages and understand how this composition relates to the establishment of symbiosis, nutrient exchange, and ultimately sponge holobiont survival. To the best of our knowledge, this study represents the first functional insights of Antarctic sponge microbiomes.

Methods

Sample collection

Sponge samples were collected on January 2013 at two sites in Fildes Bay, King George Island, Antarctica. Myxilla sp. (class Demospongiae, N = 1) was sampled from site 1 (62°11′59.1″S, 58°56′35.1″W) at 5 m depth, and L. antarctica (class Calcarea, N = 1) was sampled from site 2 (62°11′17.7″S, 58°52′22.8″W), at 27 m depth. Sponge samples were then kept individually in plastic bags containing natural seawater at 4 °C until processing. In addition, two seawater (SW) samples were collected approximately 5 m away from the L. antarctica sampling location using a 5 L Niskin bottle. These samples were prefiltered on board through a 150 μm pore mesh to remove large particles, stored in an acid-washed carboy and kept in the dark until processing in the lab. Sponge and SW samples were processed within 1 hour after collection.

Sponge and seawater treatment

Each sponge specimen was rinsed 3 times with sterilized SW, cleaned under a stereomicroscope to remove dirt and ectoparasites and stored at −80 °C until processing. From each sponge, triplicate tissue samples of ~1 cm3 were cut with a sterile scalpel blade. Separation of the microbial community intimately associated with the sponge, from that loosely attached, was conducted following the protocol described in Rodríguez-Marconi et al.28. Briefly, sponge tissue was disrupted, filtered and serially centrifuged before DNA extraction of the resulting pellet. For analyses of the surrounding planktonic community, SW samples were filtered through 20 (NY20), 3 (GSWP) and 0.2 μm (GPWP) pore size filter 47 mm in diameter (Millipore), using a Swinnex holder system and a Cole Parmer 1–600 rpm peristaltic pump. Filters were stored in 2 mL cryovials at −20 °C until DNA extraction.

DNA extraction

Genomic DNA from the pellets obtained after sponge treatment was extracted with the PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit (MOBIO), following the manufacturer’s instructions. For SW, 0.2 μm filters were thawed and half of them were cut into small pieces. Samples were incubated in lysis buffer (TE 1×/NaCl 0.15 M), with 10% SDS and 20 mg mL−1 proteinase K and incubated at 37 °C for 1 hour. DNA was extracted using 5 M NaCl and N-cetyl N, N, N trimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) extraction buffer (10% CTAB, 0.7% NaCl), incubated at 65 °C for 10 min. Protein removal was performed using a conventional phenol-chloroform method. DNA was precipitated using isopropanol at –20 °C for 1 h and resuspended in 50 μL Milli-Q water after two ethanol 70% wash steps. DNA integrity was evaluated by 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis, quantified using a Quantifluor (Promega) with Quant-iT Picogreen (Invitrogen), and stored at −20 °C until further analysis.

Library preparation and sequencing

Shotgun libraries were constructed using NEBNext dsDNA Fragmentase (New England Biolabs) and sequenced on the Illumina Miseq platform using a 300 cycles Miseq kit v.2 for sponge-associated microbial samples and a 500 cycles Miseq kit v.2 for the SW samples (paired-end), at the Center for Genomics and Bioinformatics, Universidad Mayor, Chile.

Shotgun metagenomic analyses

For all metagenomes obtained, Illumina sequences were filtered based on Q > 30 quality threshold using Prinseq.29. Illumina adapter sequences were removed using Cutadapt30. Sequences containing ribosomal genes were filtered with SortmeRNA version 2.031, using Silva v.119 as reference database32. Non-ribosomal reads were assembled using Spades assembler version 3.1033 with a K-mer size of 55 for Myxilla sp., 85 for L. antarctica and 33 for SW, after an evaluation of different k-mer sizes. Contigs generated from the assemblies were used to predict Open Reading Frames (ORFs) with MetaGeneMark34, using the default settings.

To assess the community composition of sponge microbiomes and SW communities, we performed a taxonomic annotation at read level using the Kaiju software35, with default settings and using the NCBI nr + euk database. This software uses protein-level classification of short high-quality reads avoiding the bias of ORF prediction. In order to compare the taxonomic composition between metagenomes, we normalized the metagenomic reads using the lowest number of reads across samples, i.e. Myxilla sp. (6,423,175, see Table 1 for details). For this, we randomly subsampled all other metagenomes according to this number. Confirmation of the taxonomic composition was carried out using the ribosomal reads (filtered with SortmeRNA), aligning them against the NCBI GenBank database release 209 (August 15, 2015) with DIAMOND36, and using the LCA algorithm implemented in MEGAN V537, with the default settings.

Table 1.

Summary of the sequencing data of the Antarctic sponge-associated microbial community and SW metagenomes.

| Myxilla sp. | Leucetta antarctica | SW | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of high-quality reads | 6,423,175 | 9,056,920 | 5,706,551 |

| Number of contigs ≥200 bp | 203,539 | 104,666 | 541,337 |

| Estimated average coverage (%) | 87 | 86 | 74 |

| Average genome size (Mb) | 6.7 | 6.6 | 2.2 |

| N50 (>200 bp) | 641 | 937 | 639 |

| GC (%) | 44.8 | 45.9 | 38.3 |

| Number of predicted ORFs | 137,177 | 89,044 | 252,171 |

| ORFs annotated using Eggnog | 24,214 (17.7%) | 39,586 (44.5%) | 144,564 (57.3%) |

| ORFs annotated using Seed | 19,133 (13.9%) | 33,299 (37.4%) | 115,888 (45.9%) |

| ORFs annotated using Pfam | 20,982 (15.3%) | 36,579 (41.1%) | 118,245 (46.9%) |

To describe the metabolic potential of sponge-associated and SW communities, first, ORFs assigned as Metazoan, based on MEGAN analysis, were removed. Remaining ORFs (≥180 bp) were aligned using DIAMOND against Eggnog database v4.538. Gene annotation was also computed based on the Subsystems approach with the SUPER-FOCUS tool, which uses a reduced SEED/Subsystems database39. In all cases, the cutoff used was E-value < 10−5. ORFs annotation was confirmed using Geneious version R10.2 with BLASTx against NCBI-nr database with BLOSUM62 matrix, using a Word size 3.

To evaluate the potential role of Thaumarchaeota members in nitrogen and carbon cycles, a synteny analysis of key genes for theses cycles was performed using Nitrosopumilus sp. close related genomes. For this, contigs containing ORFs related to ammonia oxidation and 3-Hydroxypropionate/4-Hydroxybutyrate (3HP/4HB) pathways were analyzed using Geneious version R10.2 and Trebol software (http://bioinf.udec.cl). Contigs were compared against the complete genome of “Candidatus Nitrosopumilus adriaticus” (accession NZ_CP011070), and “Candidatus Nitrosopumilus sp. AR2” (accession NC_108656) and genomic scaffolds of “Candidatus Nitrosopumilus Nsub” (accession NZ_LQMW00000000), “Candidatus Nitrosopumilus NM25” (accession NZ_BGKI00000000), “Candidatus Nitrosopumilus salaria” (NZ_AEXLNZ_BGKI00000000), “Candidatus Nitrosopumilus SJ” (accession NZ_AJVI00000000).

Coverage and GC content

To estimate the coverage and complexity of microbial communities we use a redundancy-based approach implemented by Nonpareil40. Nonpareil uses the redundancy of the reads in a metagenomic dataset to estimate the average coverage and predicts the number of sequences that will be required to achieve a nearly complete coverage, which in this case was defined as ≥95%. Parameters used were a similarity threshold = 95%, minimum overlapping percentage = 50% and a maximum number of query sequences = 1000. GC content (in %) was calculated using the raw high-quality reads, filtered by >Q30, with an in-house Perl script.

Abundance estimation, normalization and multivariate analyses

To avoid differences of gene abundance due to variation in genome size among metagenomes, a normalization by the average genome size (AGS) was performed using MicrobeCensus41. AGS is estimated based on the abundance of single-copy universal genes to obtain the genome equivalent across the dataset. The abundance of each annotated gene in the metagenomes was estimated based on the number of reads mapped on to predicted ORFs using Bowtie2 and SAMtools42,43. The abundance of each gene was normalized by its length and genome equivalent. Gene abundances are expressed in reads per kilobase per genome equivalent (RPKG). In the case of the two SW samples, RPKG values were summed, accounting for the total SW metagenome.

Exclusive and shared genes between sponge microbiomes and the SW community were computed creating a list of unique COGs using the above ORFs predicted and annotated by Eggnog database. To do so, the abundance values of each COG with the same ID were summed. Differentially abundant COG genes were calculated dividing the abundance of each gene in the sponge-associated metagenomes by the abundance of the same gene in the SW metagenome, and considering only those COG genes with a Fold Change (FC) ≥4. Additionally, analysis of orthologous groups of proteins (OGs) was performed to identify specific/unique OGs in each sponge microbiome and SW sample. To do this, all predicted proteins of the three metagenomes were merged together and proteins >50 amino acids were clustered using reciprocal BLASTp with DIAMOND and Markov Cluster algorithm (MCL) with an inflammation parameter of 1.4. OGs were annotated using Eggnog database and classified as sponge-specific only if proteins of sponge metagenomes compose the cluster. If clusters were composed only of proteins belonging to SW, they were classified as planktonic-specific proteins. Finally, shared OGs were those composed of both sponge-specific and SW proteins.

Hierarchical clustering was performed based on the abundance of each gene (RPKG values) using the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity coefficient in PRIMER v6 for Windows (PRIMER-E Ltd). Heatmap and scatterplot were generated using ggplot2 version 3.3.2 (http://ggplot2.org)44 under R environment version 3.3.0.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) estimation of gene copy numbers

The abundance of key genes related to Calvin–Benson–Bassham (CBB), Reductive Krebs (rTCA) and 3-Hydroxypropionate/4-Hydroxybutyrate (3HP/4HB) cycles, ammonia oxidation and denitrification was evaluated through qPCR. For this, degenerated primers were designed using consensus sequences obtained from the comparison of the key genes identified in Mxyilla sp. and L. antarctica metagenomes against the NCBI nr/nt database (release versions 223, 228 and 229) using BLASTn. Ten to fifty best hits retrieved were aligned using MUSCLE in the software Geneious version R10.2 using default parameters. Primers specificities, self complementary, and Tm were tested using primer-BLAST. Standards were prepared using the metagenomic DNA and cloning the products using TOPO TA Cloning Kit (Invitrogen, Life technologies). Quantitation of the standards was performed using Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Invitrogen). The qPCR was performed using KAPA SYBR FAST qPCR Kit (Kapa Biosystems, Roche) according to manufacturer’s recommendations and on a StepOne Real-Time PCR System according to conditions indicated in Supplementary Table S1. Standards were used in triplicate in a serial dilution of 1 × 104 to 1 × 108. Samples were run in triplicate using 1 ng μL−1 of DNA for Myxilla sp. and 0.5 ng μL−1 for L. antarctica. The data obtained were corrected according to the dilution factor of the sample and standardized according to the copy number of the housekeeping genes (rpoD and efl1).

Sequence accession number

Metagenome datasets have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under the BioProject accession no. PRJNA528189. The Whole Genome Shotgun projects have been deposited at DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under the accessions WASW00000000 for L. antarctica microbiome, WASV00000000 for Myxilla sp. microbiome and WASX00000000 for seawater community. The versions described in this paper are versions WASW01000000 for L. antarctica microbiome, WASV01000000 for Myxilla sp. microbiome and WASX01000000 for seawater coomunity. The scritps used in the study can be accessed at 10.6084/m9.figshare.9851240.

Results

Antarctic sponge microbiomes differ in genomic and community composition from seawater communities

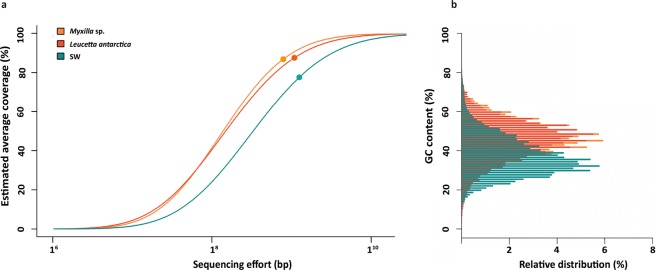

We obtained metagenomic data from two common Antarctic sponge species, Myxilla sp. and L. antarctica, and from the surrounding SW, to compare their microbial community composition and genetic potential. Metagenomes accounted for a total of 21 Mb of sequencing data, with 15,480,095 reads for the sponge-associated metagenomes and 5,706,551 for the SW metagenomes (Table 1). Overall, microbial complexity was similar between the sponge microbiomes but both differed markedly from SW communities (Fig. 1a). This difference in complexity between the sponge and SW microbiomes was further evidenced by GC content differences of individual reads in the metagenomic datasets of sponge-associated and SW communities (Fig. 1b, Table 1).

Figure 1.

Coverage and complexity of microbiomes from the Antarctic sponges and SW communities (a), and their GC content (b). In panel a, the circles show the coverage obtained in each metagenome and the lines following the circles represent projections. In panel b, the distribution of GC content (%) for each contig assembled from the sponge microbiomes and SW metagenomes is shown.

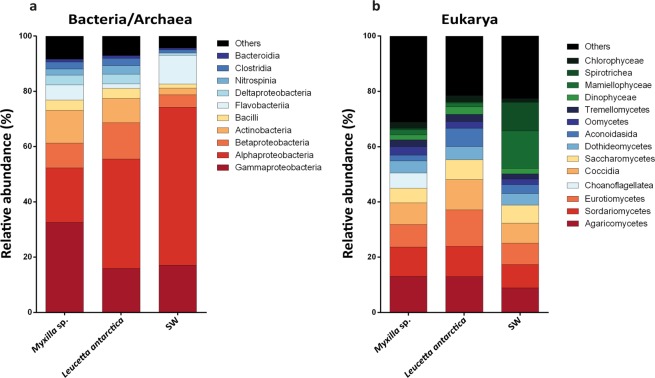

The community composition of the sponge-associated and SW microbial communities differed notably in the Bacteria-Archaea and the Eukarya domains (Fig. 2). In the sponge-associated Bacteria-Archaea communities, the phylum Proteobacteria was the most abundant, followed by Bacteroidetes and Actinobacteria (Supplementary Table S2). At the class level, Myxilla sp. was mainly composed of Gammaproteobacteria (32% of total reads), Alphaproteobacteria (19%) and Actinobacteria (12%), while L. antarctica harbor a high abundance of Alphaproteobacteria (33%), followed by Thaumarchaeota (14%), Betaproteobacteria (13%), and Actinobacteria (3%). In contrast, SW communities were dominated mainly by Alphaproteobacteria (57%), Gammaproteobacteria (17%) and Flavobacteria (10%) (Fig. 2a). Similar taxonomic profiles were found based on ribosomal genes (Supplementary Fig. S1). The most abundant bacterial-archaeal genus associated with Myxilla sp. was Cycloclasticus (Gammaproteobacteria; Order Thiotrichales) (6% of total reads annotated at genus level), and Nitrosopumilus (Thaumarchaeota; Nitrosopumilales) (15%) for the L. antarctica microbiome. In contrast, the SW community was dominated mainly by “Candidatus Pelagibacter” (Alphaproteobacteria; Pelagibacterales) (34%) (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Figure 2.

Microbial community composition of Antarctic sponges and SW based on metagenomic reads. Taxonomic composition was assigned to class level using the Lowest Common Ancestor algorithm (LCA). (a) Taxonomic classification for Bacteria/Archaea. (b) Taxonomic classification for Eukarya. All sequences assigned to Fungi were filtered.

In the case of Eukarya, Fungi (Ascomycota, Basidiomycota and Fungi incertae sedis) was the most abundant group in the three metagenomes analyzed but were still significantly more abundant in the sponges (Supplementary Fig. S1). This group represented 77% and 80% of reads annotated for Myxilla sp. and L. antarctica, respectively, but only 55% for SW. Of the different fungal classes, Agaricomycetes was the most abundant, comprising on average 20% of reads among the three metagenomes (Supplementary Fig. S3a). At lower taxonomic levels, a total of 410 genera of Fungi were detected of which 307 genera (75%) were shared between the three metagenomes (Supplementary Fig. S3b). Of these, the most abundant fungal genus was Aspergillus (3%), followed by Exophiala (3%) (Supplementary Table S3). After Fungi, the most abundant eukaryotic groups detected, consisted of Oomycetes (18%), Chlorophyceae (13%), Dinophyceae (11%), and Mamiellophyceae (11%) for Myxilla sp., and Dinophyceae (17%), Oomycetes (15%), Chlorophyceae (14%) and Coscinodiscophyceae (12%) for L. antarctica (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Table S4). The most abundant eukaryotic genus associated with Myxilla sp. after accounting for Fungi was Symbiodinium (Class Dinophyceae; Order Suessiales) (6% of total reads annotated), whereas it was Trypanosoma (8%) in the L. antarctica microbiome. But for SW, eukaryotic members were dominated by Mamiellophyceae (16%) mainly composed by Bathycoccus (20%) (Supplementary Fig. S1). Taxonomic profiles based on ribosomal genes for the Eukarya domain were different to those based on total reads, as opposite to the Bacteria-Archaea domains (Supplementary Fig. S1).

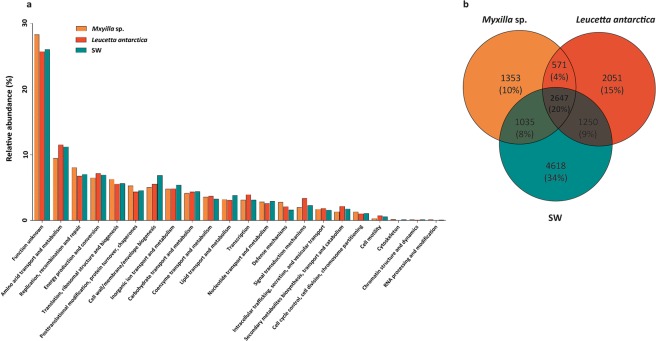

Antarctic sponge microbiomes display genomic adaptations to symbiotic lifestyle

We annotated between 14 and 57% of the predicted ORFs (Table 1). Whereas both sponge microbiomes were composed of different assemblages of microorganisms, the relative abundance of functional genes was similar in general categories based both on EggNOG (Fig. 3a), and SEED annotation (Supplementary Fig. 4). We observed 57% functional similarity between the sponges, and 54% similarity between the sponges and the SW, based on the ORF relative abundance annotated using Eggnog. These categories include amino acid transport and metabolism, replication, recombination and repair, energy production and conversion, between others similarly abundant functions in all metagenomes.

Figure 3.

Relative abundance of Eggnog categories, and unique and share COGs between the Antarctic sponge-associated and SW communities. (a) Classification of proteins annotated for Myxilla sp., Leucetta antarctica microbiomes and in SW metagenome. (b) Uniques and shared COGs between the three metagenomes.

Comparisons between sponge and SW metagenomes indicated that 29% of the total number of COGs assigned among the three metagenomes was exclusive to the sponge microbiomes. There were 1,353; 2,051 and 4,618 exclusive COGs in Myxilla sp., L. antarctica and SW, respectively, which accounted for 10%, 15% and 34% of total assigned COG’s respectively for each metagenome (Fig. 3b). Exclusive COGs represented a broad spectrum of functions, but the low RPKG values indicated that many genes occur in low abundance (Supplementary Table S5).

The most abundant sponge-specific COGs were related to symbiotic lifestyle and were functionally annotated as transposases (ENOG4110TSY, ENOG4111K9G, ENOG4111Z47), Type IV restriction endonuclease (COG2810), Type II restriction enzyme SfiI (ENOG410YF7N), and Zeta toxin from the T-A system (ENOG4111XAS) (Supplementary Table S6). Further analysis of sponge-specific functions using a clustering of orthologous groups of proteins (OGs) also showed a prevalence of genomic adaptations related to a symbiotic lifestyle. The most abundant sponge-specific OGs were TPR repeat (COG0457), DNA modification methylase (COG0863), large exoprotein involved in adhesion (COG3210), and Chitinase (COG3979) -all of which represent functions related to persistence within the sponge tissue (Supplementary Table S6).

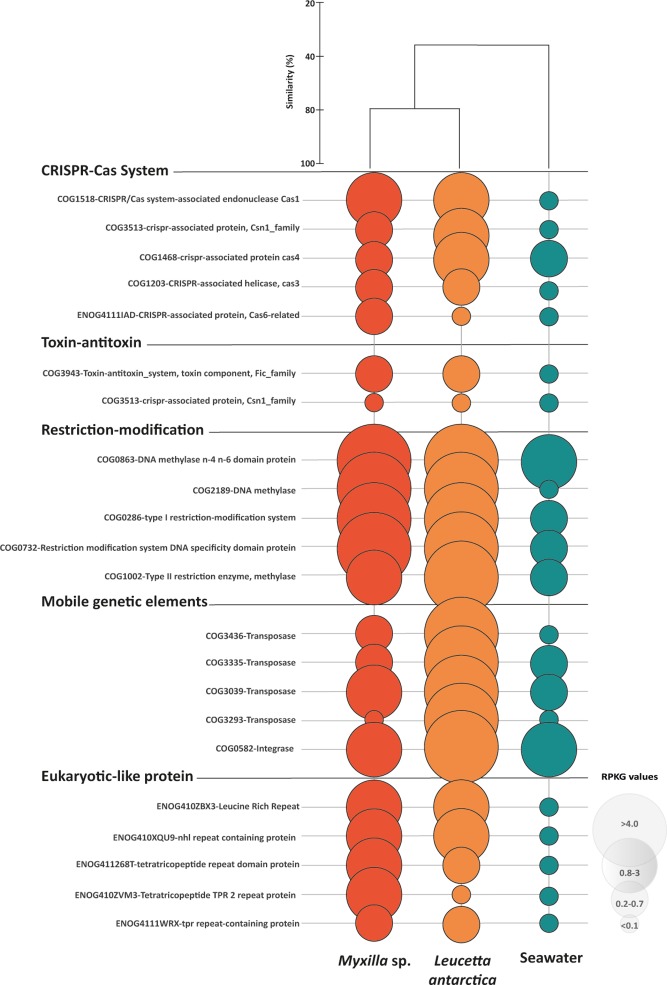

On the other hand, 20% of total annotated functions were COGs shared between sponge microbiomes and the SW community (Fig. 3b). Among these, 28% (751 annotated COG) and 35% (932 annotated COG) were overrepresented in Myxilla sp. and L. antarctica, respectively. This differentially abundant fraction of COGs (FC ≥ 4), were often related to the symbiotic lifestyle (Fig. 4, Supplementary Table S7). Specifically, CRISPR-associated protein, T-A and R-M systems were 73, 114 and 238 times more abundant in the sponge microbiomes than in SW. The MGEs and the ELPs (annotated as ARP, LRR and TPR repeats) were similarly over-represented in the sponge microbiomes, with up to 437 and 389 FC. In contrast, exclusive COGs in the SW community correspond to general functions, annotated as chain length determinant protein (ENOG410Y1H4); DNA-dependent RNA polymerase (COG5108); CAAX amino terminal protease family protein (COG1266); DNA polymerase (ENOG411267Q); and tryptophanase (COG3033). Accordingly, SW-specific OGs were represented by Dehydrogenase (COG1012), Dehydrogenase reductase (COG1028), Amp-dependent synthetase and ligase (COG0318), Histidine kinase (ENOG410XNMH), and Sulfatase (COG3119) (Supplementary Table S7).

Figure 4.

Specific functions in sponge microbiomes and SW community. Bubbles reflect abundance (RPKG) of each COG in the different functional categories. Orange bubbles represent microbiome associated with Myxilla sp., red bubbles Leucetta antarctica and green bubbles, SW. The cluster represents the percent similarity according to Bray-Curtis dissimilarity coefficient.

Antarctic sponge metagenomes have a broad repertoire of genes related to nutrient cycling

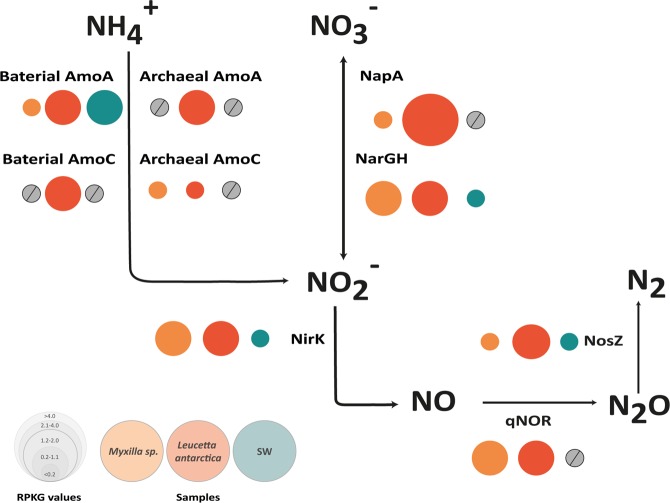

Similar to sponge microbiomes from other environments, Antarctic sponge metagenomes display a broad repertoire of genes related to nutrient cycling. In the case of the nitrogen cycle, all genes identified were more highly represented in the sponge microbiomes than in SW, i.e., ammonia oxidation, nitrite oxidation, and denitrification (Supplementary Table S8, Fig. 5). Coding genes for archaeal and bacterial ammonia monooxygenase (amoA and amoC) were enriched in the L. antarctica microbiome compared to Myxilla sp. (Fig. 5). Consistent with these results, taxonomic analysis shows that amo genes in L. antarctica were mainly associated with Nitrosopumilaceae and Rhodospirillales members (Supplementary Table S9), and that amo gene clusters in this microbiome were in synteny with the available genomes of “Candidatus Nitrosopumilus sp.” (Supplementary Fig. S8). Together, these results strongly suggest that Nitrosopumilus spp. are involved in the genomic potential for ammonia oxidation found in the L. antarctica microbiome.

Figure 5.

Nitrogen pathways present in Antarctic sponge symbionts and SW communities. Bubbles reflect abundance (RPKG) of each enzyme involved in nitrogen cycle normalized by the average genome size (AGS). Orange bubbles represent microbiome associated with Myxilla sp., red bubbles, Leucetta antarctica and green bubbles, SW. Grey circles represent functions that are absent in the metagenomes.

Genes related to denitrification and nitrate oxidation were more abundant in the L. antarctica microbiome compared to Myxilla sp. and SW (Fig. 5). While the periplasmic nitrate reductase-encoding gene (napA) and nitrous-oxide reductase-encoding gene (nosZ) were more abundant in L. antarctica, the membrane-bound respiratory nitrate reductase gene (narGH), nitrate reductase (nirK) and nitric oxide reductase (qnor) were similarly abundant in both sponges. Overall, these results indicate the presence of a complete denitrification pathway in both sponge microbiomes (Fig. 5). Moreover, genes codifying for proteins involved in creatinine, creatine, and urea metabolization were also detected in both sponges. For the urea degradation, while L. antarctica microbiome seems to use the ATP-independent pathway, the Myxilla sp. microbiome apparently performs urea degradation by the ATP-dependent pathway (Supplementary Fig. 7), at least at the sampling time. qPCR results showed a similar profile compared to the metagenomic results (Supplementary Table S10).

For the sulfur cycle, oxidation pathways were detected in both sponge metagenomes (Supplementary Fig. 8), including the sulfite (reverse dissimilatory sulfate reduction dsrABJKMOP, aprAB and sat genes) and sulfur oxidation (soxABXYZ genes) pathways. Taxonomic analysis of sox genes obtained from Myxilla sp. microbiome reveal a high similarity (58–94%) with the genome of Cycloclasticus sp. (Supplementary Table S9). In the case of L. antarctica microbiome, sox genes show similarity with diverse microorganisms, including Rhizobiales, Rhodospirillales, Burkholderiales, Nitrosomonadales, Methylococcales, Gammaproteobacteria TMED119 and Solemya elarraichensis gill symbiont (Supplementary Table S9). Additionally, all genes for catabolization of dimethylsulphoniopropionate (DMSP) via the demethylation pathway, and transport and degradation of taurine were also detected. This indicates the potential to utilize organic sulfur compounds by both Antarctic sponge microbiomes.

For the phosphorus cycle, polymerization via the enzyme polyphosphate kinase and depolymerization of polyphosphate (polyP), using exopolyphosphatase, are also potential functions exerted by the Antarctic sponge microbiomes analysed. The enzymes polyphosphate kinase and exopolyphosphatase were enriched in both sponge microbiomes compared to SW. Furthermore, ABC phosphate transporters, codified by pstABCS, were found in high abundance in the sponges analyzed here in comparison to SW (Supplementary Table S8). Further details of proteins related to biogeochemical cycling of carbon, nitrogen, sulfur and phosphorus, identified in Myxilla sp., L. antarctica, and SW are shown in Supplementary Table S8.

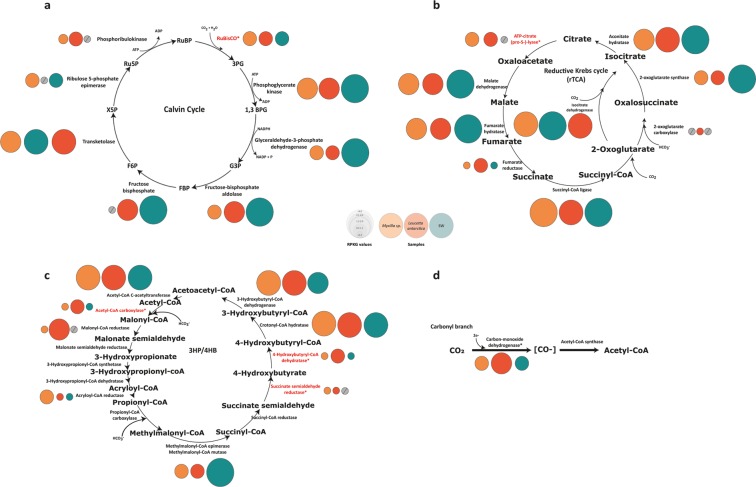

Finally, for carbon, four of the six described metabolic pathways for autotrophic carbon fixation were detected in the sponge microbiomes analyzed here: Calvin–Benson–Bassham (CBB), Reductive Krebs (rTCA), Wood–Ljungdahl (WL), and 3-Hydroxypropionate/4-Hydroxybutyrate (3HP/4HB) (Fig. 6). Genes coding for the key enzyme for the CBB cycle, Ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase (RuBisCO), were also detected in the three metagenomes, but were enriched in the L. antarctica microbiome (Supplementary Table S8). Taxonomic analyses of the detected RuBisCO genes revealed a dominance of bacterial form I of RuBisCO in both sponge microbiomes. All genes encoding RuBisCO recovered from the Myxilla sp. microbiome were assigned to the chemolithoautotroph bacteria “Candidatus Thioglobus sp.” (Gammaproteobacteria). In the case of L. antarctica, genes detected were assigned to Nitrosospira sp. (Betaproteobacteria), Rhodobium sp. (Alphaproteobacteria) and Rhodopseudomonas sp. (Alphaproteobacteria), and to the eukaryotic photosynthetic group of Stramenopiles and Haptophyceae (Supplementary Table S9). Abundances of key genes for the remaining three carbon fixation pathways detected in the Antarctic sponge metagenomes, i.e., rTCA, WL and 3HP/4HB, were slightly different between the sponge microbiomes, and these differences were higher for the 3HP/4HB cycle. The key enzymes for the 3HP/4HB cycle, Malonyl semialdehyde reductase, Propionyl-CoA carboxylase, and 4-Hydroxybutanoyl-CoA dehydratase, were enriched ten-fold in L. antarctica compared to Myxilla sp. (Fig. 6). Taxonomic identification of these key genes for the 3HP/4HB cycle shows between 93% and 100% identity with Nitrosopumilus sp. (Supplementary Table S9). Additionally, contigs containing these key genes were syntenic with the genome of Nitrosopumilus sp. (Supplementary Fig. S5). This is consistent with our taxonomic analysis based both on total and ribosomal reads, which indicated that Nitrosopumilus sp. was more abundant in L. antarctica than Myxilla sp. (see Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. S1 and Supplementary Fig. S2). Yet in SW, only genes related to Calvin and WL cycles were found, although one of the three known genes for rTCA, and two of the three for 3HP/4HB, were also found (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Autotrophic carbon pathways present in Antarctic sponge symbionts and SW communities. Bubbles reflect abundance (RPKG) of each enzyme involved in Calvin cycle (a), reductive Krebs cycle (rTCA) (b), 3-hydroxypropionate/4-hydroxybutyrate (3HP/4HB) cycle (c), and Wood–Ljungdahl pathway (d). Orange bubbles represent microbiome associated with Myxilla sp., red bubbles Leucetta antarctica and green bubbles, SW. Enzymes colored in red indicate key functional genes in each cycle. Grey circles represent functions that are absent in the metagenomes.

Discussion

Our metagenomic analysis of the microbiomes from two ubiquitous sponge species from Antarctica, Myxilla sp. and L. antarctica25,45, provide insights into sponge microbiomes from extreme environments. They are also helpful in comparing sponge holobionts from these extreme environments to temperate and tropical environments. To begin, the taxonomic composition of the two sponge microbiomes were similar to each other, and similarly different from those of surrounding SW. However, since there is no information about the individual variability of the microbiomes of the these two Antarctic sponges, comparisons with the surrounding SW could be affected by a potential effect of such variability. In general, we observed the commonly described bacterial and archaeal members of the sponge microbiota5,46,47. We show a dominance of Gamma- and Alphaproteobacteria, and the Archaea Thaumarchaeota, as opposed to the SW that was mainly dominated by Betaproteobacteria. Unlike most sponge-species from tropical and temperate environments, which are typically associated with Cyanobacteria, we did not detect Cyanobacterial sequences in the Antarctic sponges. The lack of Cyanobacteria in Antarctic sponges is in agreement with the absence of this taxon in marine systems from higher latitudes, and also with previous reports for Antarctic sponge microbiomes27,28,48. For Eukarya, the two sponge metagenomes were highly enriched in fungal sequences. Still, a large fraction of these Fungi also occurred in SW, and thus likely are non-symbiotic in nature. A similar conclusion was reached for sponges collected from the Mediterranean and North Sea49,50. The dominance of Fungi was unexpected since they had not been detected in our previous study28. Interestingly, the inferred taxonomic profiles based on total reads and on ribosomal genes fit almost exactly with expectations for Bacteria and Archaea domains based on the work of Rodríguez-Marconi et al.28, which used a different approach to analyze the same samples. But, our results significantly differed from this previous work in considering the Eukarya domain. These differences could be attributed to the lower representation of protist genomes in the database used as part of our taxonomic approach.

Additionally, the few Antarctic sponge microbiomes analysed here showed larger AGS and higher GC content in comparison to the SW planktonic community. Although genome reduction is a generalized strategy in bacterial symbionts51, larger genomes inside sponge bacterial communities such as those described here have been previously described13. This observation may be explained by the high exposition of free DNA for the sponge’s ingestion of food bacteria, which may, in turn, lead to higher levels of horizontal gene transfer (HGT) within sponges13. Differentiation of sponge-associated communities from surrounding SW is a common feature of sponge biology5,9, that reflects the intimate symbiotic relationship between the microbiome and the host invertebrate.

Functional analyses of the sponge holobionts revealed two broad categories of gene functions that differed from surrounding SW. First, sponge-associated microbiomes showed a high abundance of genes associated with the symbiotic lifestyle. These include high abundances of genes related to MGEs (e.g. transposons, phages genes), ELPs, and foreign DNA defensive mechanisms (e.g., CRISPR, T-A and R-M systems) in comparison to the planktonic microbial community. Previous work has identified these functions in genomes of bacteria associated with sponges, and in sponge metagenomes9,52–54. Thus, these genes could play a specific role in facilitating the symbiosis by promoting gene exchange, defending from foreign DNA, or limiting phagocytosis55. In doing so, they point to the possibility of genomic adaptations to the symbiotic lifestyle in Myxilla sp. and L. antarctica microbiomes, much like have been observed in sponge microbiomes from temperate and tropical environments9,13,56. More generally, they point to common molecular mechanisms mediating symbiosis with sponges across all environments, including Antarctica.

Second, both sponges also showed considerable functional diversity related to the cycling of sulfur, phosphorus, nitrogen and carbon. With respect to sulfur, results suggest that Antarctic sponge microbiomes analysed potentially carry out thiosulfate oxidation and sulfate oxidation, which could serve as an electron source of energy for these microorganisms57. Our taxonomic analysis of sox genes indicates that SOB in Myxilla sp. belong mainly to Gammaproteobacteria members, specifically to Cycloclasticus. This bacterial genus has been recently reported in association with the sponge Myxilla methanophila from hydrocarbon seeps of the Gulf of Mexico58. The presence of these microorganisms in two geographically distant sponges suggests that Cycloclasticus sp. could be a key member of the sulfur cycle, and specific to the microbiome of sponge genus Myxilla.

With respect to phosphorus cycling, genes coding for polyphosphate kinase, responsible for the synthesis of polyP, were detected in both Antarctic sponges. Previous work in tropical sponges suggested that symbiotic microorganisms may accumulate granules of polyP when the sponge is actively pumping, which could then function as an energy reserve for microorganisms when pumping ceases and nutrient inputs diminish21. Our results, though, suggest that polyP may also be synthesized for these purposes by Alpha-, Beta- and Gammaproteobacteria -abundant members of the Antarctic sponges known to possess this capacity21. If so, sponge holobionts may play a more prominent role than previously recognized in the phosphorus cycle of benthic Antarctic ecosystems.

Moreover, functional analyses show that Antarctic sponge microbiomes may play a significant role in nitrogen cycling by performing ammonia oxidation, nitrate oxidation, and denitrification. This is based on our detection of the archaeal and bacterial ammonia monooxygenase (amoA and amoC), the nitrate reductase-encoding gene (napA), the nitrous-oxide reductase-encoding gene (nosZ), the membrane-bound respiratory nitrate reductase gene (narGH), the nitrate reductase encoding gene (nirK), and the nitric oxide reductase encoding gene (qnor). The abundance of Nitrosopumilus sp. in L. antarctica, and the synteny of archaeal amo gene cluster, point to their role in ammonia oxidation. While similar results related to ammonia oxidation were not detected to Myxilla sp., they may still occur. Previous research in temperate and tropical sponges have similarly shown that microorganisms fulfill important roles in sponge nitrogen dynamics by metabolizing sponge waste products9,59,60.

Still, perhaps more than for any other nutrient, these results point to the special roles of these sponge microbiomes in carbon fixation. Unlike “phototrophic sponges” that harbor photosynthetic microorganisms to supply the sponge carbon requirements61, both Antarctic sponge holobionts display light-independent pathways for CO2 fixation mediated by chemoautotrophic microorganisms. Note that this was not the case for the SW metagenome, where the Calvin cycle was observed to be most important to carbon fixation. Only in previous work of deep-sea sponge microbiomes have chemoautotrophic microorganisms (e.g., Ammonia-Oxidizing Archaea (AOA) and Sulfur-Oxidizing Bacteria (SOB)) been described as key members18,59,62,63. We therefore speculate that the presence of chemoautotrophic microorganisms in the Antarctic sponges could be helpful in facing the extreme environmental conditions characterized by strong seasonal light variation. Further studies incorporating stable isotopic labeling and carbon flux measurements could help quantify the contribution of these microorganisms to carbon fixation.

Conclusion

Our functional metagenomic analyses of two abundant Antarctic sponges, Myxilla sp. and L. antarctica, show that the microbial communities are more similar to each other, than to surrounding SW. In both cases, they show larger AGS and higher GC-content in comparison to the planktonic community. Proteobacteria and Thaumarchaeota dominated the Bacteria and Archaea domains in the sponge-associated microbial communities, whereas Fungi dominated the Eukarya. Functional analyses point to a broad range of functions associated with the symbiotic lifestyle and biogeochemical cycling. Potential functions further suggest that the microbiomes play roles in the cycling of sulfur, phosphorus, nitrogen, and carbon. In particular, these results suggest that these microbiomes utilize light-independent pathways for CO2 fixation that are mediated by chemoautotrophic microorganisms. The diversity of functions observed for nutrient cycling suggest that sponge microbiomes in Antarctica may play an important role in the growth and survival of sponge holobionts from these harsh environments, and more broadly, in major nutrient cycles of Antarctic marine systems.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work has been funded by INACH grants RG_31-15, DG_12-17, RT_34-17, CONICYT- FONDECYT grant N°1190879, Puente “Linking microbial community structure with their functional traits in Antarctic sponge symbionts: insights into the mechanisms of host-microbe interactions” and FDP “Funcionalidad en comunidades microbianas asociadas a esponjas Antárticas” grants from the Direction of Research and Art Creation (Vicerrectoría de Investigación) of Universidad Mayor. We thank the staff at “Prof. Julio Escudero” INACH Research Station for logistic support. We are infinitely grateful to Ignacio Garrido, María José Díaz and Jorge Holtheuer for sponge sampling.

Author contributions

M.M. and N.T. conceived the experiments; M.M. and A.C. conducted the experiments; M.M. analyzed the data; M.M. and N.T. interpreted the data; M.M., J.G. and N.T. drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-57464-2.

References

- 1.Pita L, Fraune S, Hentschel U. Emerging sponge models of animal-microbe symbioses. Front. Microbiol. 2016;7:2102. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.02102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ryan JF, et al. The genome of the ctenophore Mnemiopsis leidyi and its implications for cell type evolution. Science. 2013;342:1242592. doi: 10.1126/science.1242592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor MW, Radax R, Steger D, Wagner M. Sponge-associated microorganisms: evolution, ecology, and biotechnological potential. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2007;71:295–347. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00040-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hentschel U, Usher KM, Taylor MW. Marine sponges as microbial fermenters. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2006;55:167–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2005.00046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomas T, et al. Diversity, structure and convergent evolution of the global sponge microbiome. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:11870. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmitt S, et al. Assessing the complex sponge microbiota: core, variable and species-specific bacterial communities in marine sponges. ISME J. 2012;6:564–576. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reveillaud J, et al. Host-specificity among abundant and rare taxa in the sponge microbiome. ISME J. 2014;8:1198–1209. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2013.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ribes M, et al. Functional convergence of microbes associated with temperate marine sponges. Environ. Microbiol. 2012;14:1224–1239. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2012.02701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fan L, et al. Functional equivalence and evolutionary convergence in complex communities of microbial sponge symbionts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:E1878–87. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203287109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burke C, Steinberg P, Rusch D, Kjelleberg S, Thomas T. Bacterial community assembly based on functional genes rather than species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:14288–14293. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1101591108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCutcheon JP, McDonald BR, Moran NA. Convergent evolution of metabolic roles in bacterial co-symbionts of insects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:15394–15399. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906424106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Talbot JM, et al. Endemism and functional convergence across the North American soil mycobiome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:6341–6346. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402584111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horn H, et al. An Enrichment of CRISPR and other defense-related features in marine sponge-associated microbial metagenomes. Front. Microbiol. 2016;7:1751. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mussmann M, et al. Clustered genes related to sulfate respiration in uncultured prokaryotes support the theory of their concomitant horizontal transfer. J. Bacteriol. 2005;187:7126–7137. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.20.7126-7137.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bell JJ. The functional roles of marine sponges. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2008;79:341–353. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2008.05.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang F, Vicente J, Hill RT. Temporal changes in the diazotrophic bacterial communities associated with Caribbean sponges Ircinia stroblina and Mycale laxissima. Front. Microbiol. 2014;5:561. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang F, et al. Symbiotic archaea in marine sponges show stability and host specificity in community structure and ammonia oxidation functionality. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2014;90:699–707. doi: 10.1111/1574-6941.12427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li, Z.-Y., Wang, Y.-Z., He, L.-M. & Zheng, H.-J. Metabolic profiles of prokaryotic and eukaryotic communities in deep-sea sponge Neamphius huxleyi indicated by metagenomics. Sci. Rep. 4 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Moitinho-Silva L, et al. Integrated metabolism in sponge–microbe symbiosis revealed by genome-centered metatranscriptomics. ISME J. 2017;11:1651–1666. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2017.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feng G, Sun W, Zhang F, Karthik L, Li Z. Inhabitancy of active Nitrosopumilus-like ammonia-oxidizing archaea and Nitrospira nitrite-oxidizing bacteria in the sponge Theonella swinhoei. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:24966. doi: 10.1038/srep24966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang F, et al. Phosphorus sequestration in the form of polyphosphate by microbial symbionts in marine sponges. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:4381–4386. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1423768112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Richter C, Wunsch M, Rasheed M, Kötter I, Badran MI. Endoscopic exploration of Red Sea coral reefs reveals dense populations of cavity-dwelling sponges. Nature. 2001;413:726–730. doi: 10.1038/35099547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Goeij JM, et al. Surviving in a marine desert: the sponge loop retains resources within coral reefs. Science. 2013;342:108–110. doi: 10.1126/science.1241981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rix L, et al. Differential recycling of coral and algal dissolved organic matter via the sponge loop. Funct. Ecol. 2016;31:778–789. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.12758. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McClintock JB, Amsler CD, Baker BJ, van Soest RWM. Ecology of antarctic marine sponges: an overview. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2005;45:359–368. doi: 10.1093/icb/45.2.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dayton, P. K. Polar benthos. In Polar Oceanography 631–685 (1990).

- 27.Webster NS, Negri AP, Munro MMHG, Battershill CN. Diverse microbial communities inhabit Antarctic sponges. Environ. Microbiol. 2004;6:288–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2004.00570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rodríguez-Marconi S, et al. Characterization of bacterial, archaeal and eukaryote symbionts from antarctic sponges reveals a high diversity at a three-domain level and a particular signature for this ecosystem. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0138837. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schmieder R, Edwards R. Quality control and preprocessing of metagenomic datasets. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:863–864. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martin M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet.journal. 2011;17:10. doi: 10.14806/ej.17.1.200. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kopylova E, Noé L, Touzet H. SortMeRNA: fast and accurate filtering of ribosomal RNAs in metatranscriptomic data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:3211–3217. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Quast C, et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D590–6. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bankevich A, et al. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 2012;19:455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhu W, Lomsadze A, Borodovsky M. Ab initio gene identification in metagenomic sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e132. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Menzel P, Ng KL, Krogh A. Fast and sensitive taxonomic classification for metagenomics with Kaiju. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:11257. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Buchfink B, Xie C, Huson DH. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods. 2015;12:59–60. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huson DH, Mitra S, Ruscheweyh H-J, Weber N, Schuster SC. Integrative analysis of environmental sequences using MEGAN4. Genome Res. 2011;21:1552–1560. doi: 10.1101/gr.120618.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huerta-Cepas J, et al. eggNOG 4.5: a hierarchical orthology framework with improved functional annotations for eukaryotic, prokaryotic and viral sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D286–93. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Silva GGZ, Lopes FAC, Edwards RA. An agile functional analysis of metagenomic data using SUPER-FOCUS. Methods Mol. Biol. 2017;1611:35–44. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7015-5_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rodriguez-R LM, Konstantinidis KT. Nonpareil: a redundancy-based approach to assess the level of coverage in metagenomic datasets. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:629–635. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nayfach S, Pollard KS. Average genome size estimation improves comparative metagenomics and sheds light on the functional ecology of the human microbiome. Genome Biol. 2015;16:51. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0611-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li H, et al. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wilkinson L. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis by WICKHAM, H. Biometrics. 2011;67:678–679. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2011.01616.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cárdenas CA, et al. Sponge richness on algae-dominated rocky reefs in the western Antarctic Peninsula and the Magellan Strait. Polar Res. 2016;35:30532. doi: 10.3402/polar.v35.30532. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pita, L., Rix, L., Slaby, B. M., Franke, A. & Hentschel, U. The sponge holobiont in a changing ocean: from microbes to ecosystems. Microbiome6 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Moitinho-Silva, L. et al. Predicting the HMA-LMA status in marine sponges by machine learning. Frontiers in Microbiology8 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Wilkins D, et al. Biogeographic partitioning of Southern Ocean microorganisms revealed by metagenomics. Environmental Microbiology. 2013;15:1318–1333. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nguyen MTHD, Thomas T. Diversity, host-specificity and stability of sponge-associated fungal communities of co-occurring sponges. PeerJ. 2018;6:e4965. doi: 10.7717/peerj.4965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Naim, M. A., Smidt, H. & Sipkema, D. Fungi found in Mediterranean and North Sea sponges: How specific are they?, 10.7287/peerj.preprints.3049 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.McCutcheon JP, Moran NA. Extreme genome reduction in symbiotic bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011;10:13–26. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Burgsdorf I, et al. Lifestyle evolution in cyanobacterial symbionts of sponges. MBio. 2015;6:e00391–15. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00391-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tian R-M, et al. The deep-sea glass sponge Lophophysema eversa harbours potential symbionts responsible for the nutrient conversions of carbon, nitrogen and sulfur. Environ. Microbiol. 2016;18:2481–2494. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gao Z-M, et al. Symbiotic adaptation drives genome streamlining of the cyanobacterial sponge symbiont ‘Candidatus Synechococcus spongiarum’. MBio. 2014;5:e00079–14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00079-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nguyen MTHD, Liu M, Thomas T. Ankyrin-repeat proteins from sponge symbionts modulate amoebal phagocytosis. Mol. Ecol. 2014;23:1635–1645. doi: 10.1111/mec.12384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tian, R.-M. et al. Genome reduction and microbe-host interactions drive adaptation of a sulfur-oxidizing bacterium associated with a cold seep sponge. mSystems2 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Vairavamurthy A, Manowitz B, Luther GW, Jeon Y. Oxidation state of sulfur in thiosulfate and implications for anaerobic energy metabolism. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 1993;57:1619–1623. doi: 10.1016/0016-7037(93)90020-W. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rubin-Blum M, et al. Short-chain alkanes fuel mussel and sponge Cycloclasticus symbionts from deep-sea gas and oil seeps. Nat Microbiol. 2017;2:17093. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li Z, et al. Metagenomic Analysis of genes encoding nutrient cycling pathways in the microbiota of deep-sea and shallow-water sponges. Mar. Biotechnol. 2016;18:659–671. doi: 10.1007/s10126-016-9725-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Radax R, Hoffmann F, Rapp HT, Leininger S, Schleper C. Ammonia-oxidizing archaea as main drivers of nitrification in cold-water sponges. Environ. Microbiol. 2012;14:909–923. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wilkinson CR. Net primary productivity in coral reef sponges. Science. 1983;219:410–412. doi: 10.1126/science.219.4583.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kennedy J, et al. Evidence of a putative deep sea specific microbiome in marine sponges. PLoS One. 2014;9:e91092. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.van Duyl FC, Hegeman J, Hoogstraten A, Maier C. Dissolved carbon fixation by sponge–microbe consortia of deep water coral mounds in the northeastern Atlantic Ocean. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2008;358:137–150. doi: 10.3354/meps07370. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.