Abstract

Reactivation of the anti-tumor response has shown substantial progress in aggressive tumors such as melanoma and lung cancer. Data on less common histotypes are scanty. Immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy has been applied to few cases of uterine leiomyosarcomas, of which the immune cell composition was not examined in detail. We analyzed the inflammatory infiltrate of 21 such cases in high-dimensional, single cell phenotyping on routinely processed tissue. T-lymphoid cells displayed a composite phenotype common to all tumors, suggestive of antigen-exposure, acute and chronic exhaustion. To the contrary, myelomonocytic cells had case-specific individual combinations of phenotypes and subsets. We identified five distinct monocyte-macrophage cell types, some not described before, bearing immunosuppressive molecules (TIM3, B7H3, VISTA, PD1, PDL1). Detailed in situ analysis of routinely processed tissue yields comprehensive information about the immune status of sarcomas. The method employed provides equivalent information to extractive single-cell technology, with spatial contexture and a modest investment.

Subject terms: Tumour immunology, Oncology

Introduction

The adaptive immune system has evolved into a very refined and complex coordination of multiple actors (T, B, dendritic, NK cells etc.) devoted to the control of exogenous attackers, while avoiding the collateral damage of the self1. The onset of cancer affects both the adaptive and the innate immune system via multiple mechanisms: by increasing the cell turnover and mass, by creating new vascularized tissue, by presenting new antigens in a previously tolerant scenario and by recruiting heterotopic inflammatory cells2.

How the adaptive immune system deals with cancer has recently gained attention because of the promising clinical results with personalized medicine targeting the T-cell response against tumors3,4. The immune reaction against the tumor is placed in check by the combined action of tumor escape and naturally occurring mechanisms which dampen the immune response3–8. These mechanism may co-exist and function independently9 and the result is a cancer immunogram in which each tumor has a combination of the various components4,7. Inhibition of blocking immune checkpoints via therapeutic antibodies restores a pre-existing anti-tumor T-cell response and results in prolonged remission or cure of otherwise lethal cancers10–12.

Not all cancer patients respond to a checkpoint inhibitor therapy. The tumor mutational burden, i.e. the ability to present neoantigens to the adaptive immune system, has been identified as one major biomarker predictive of response10,12. Hypermutating tumors are good candidates for this therapy13. An altered DNA copy number or ongoing DNA damage repair mechanisms14,15 may also recruit intratumoral lymphocytes (TILs).

Distinctive modules of inflammation shared by diverse cancer histotypes have been revealed by pan-cancer analysis of deposited gene-expression databases16,17: these studies have shown that tumor mutation burden and CD8 TIL infiltration have an impact on the prognosis, but a macrophage signature may also affect the outcome17. Some studies have identified a macrophage signature independent of tumor type18, yet the awareness of the complex regulation of macrophage biology may suggest otherwise19.

Leiomyosarcomas originating from myometrium (ULMs), have not been intensively investigated because of their low incidence and because they are perceived as a minor target for immune intervention, given the few tumor TILs on H&E sections and the low mutational burden20.

As few as two dozens ULMs have been treated with checkpoint inhibitors, with dismal results21–23. However, with the exception of one responsive case22, in none of them the TILs or the macrophages have been thoroughly studied.

Here we present a comprehensive high-dimensional analysis of the inflammatory infiltrate in 21 sarcoma cases with a panel of 40 markers including lineage specific leukocyte proteins, activation markers and component of the immunological synapse, by using a novel robust method, effective on routinely processed materials, but capable of highly detailed single cell analysis.

Materials and Methods

Patients and case selection

21 cases of leiomyosarcoma were selected out of 77, based on both full clinical history and tissue block availability. The female patients were aged 51.2 ± 11.8 years (34–69), 52% post-menopausal, 11 FIGO stage IB, 1 stage IIB, 5 stage IIIB/C, 3 IVB, one unknown. 13 were classified TNM pT1, 1 pT2, 6 pT3. The biological parameters are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic and phenotypic data.

| Case N. | Age | Menopause | FIGO | TMN | Size cm. | Mitosis/10HPF | Necrosis | MHC Class I | MHC Dynamics | Desmin | B7H3 | Axl | IDO | Total cells/sq mm | Segmented/total DAPI | Predominant T cell phenotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 39 | No | IVB | pT3aNxM1 | 6 | 20 | Present | +++ | induced | + | + het | ++ | pos | 900 | 31% | Tex-chronic |

| 2 | 63 | Yes | IVB | pT1bNxM1 | 16 | 11 | Present | +++ | constitutive | + | + | ± | pos weak | 1248 | 23% | Tex-acute |

| 3 | 34 | No | N/A | N/A | 2 | 9 | Absent | + | induced | +++ | + het | ++ | pos | 517 | 15% | Deserted |

| 4 | 36 | No | IB | pT1bN0Mx | 11 | 50 | Present | ± | constitutive | ± | +++ | ++ | pos | 210 | 5% | Deserted |

| 5 | 55 | Yes | IIIB | pT3bNxMx | 20 | 18 | Absent | + | induced | neg | +++ | ++ het | pos | 2567 | 77% | Tex-acute |

| 6 | 61 | Yes | IB | pT1bNxMx | 12 | 25 | Focal | + | constitutive | +++ | + het | + het | pos | 474 | 8% | Deserted |

| 7 | 44 | No | IVB | pT1bNxM1 | 14 | 40 | Present | + | constitutive | neg | ± | pos | 363 | 6% | Tex-acute | |

| 8 | 40 | No | IIIB | pT3bN0Mx | 4 | 30 | Present | ± | constitutive | +++ | +het | + | pos | 481 | 8% | Deserted |

| 9 | 47 | No | IB | pT1bN0Mx | 9 | 35 | Focal | +++ | constitutive | + | + het | neg | pos weak | 593 | 14% | Deserted |

| 10 | 62 | Yes | IB | pT1bN0Mx | 8 | 25 | Focal | +++ | induced | +++ | +/− het | + | pos weak | 1780 | 38% | Tex-acute |

| 11 | 61 | Yes | IIB | pT2bNxMx | 13 | 25 | Focal | +++ | constitutive | neg | + | + | pos | 1644 | 44% | Deserted |

| 12 | 49 | No | IB | pT1bNxMx | 11 | 25 | Focal | + focal | induced | neg | +++ | ± | neg | 2890 | 54% | Deserted |

| 13 | 59 | Yes | IB | pT1bNxMx | 7 | 13 | Focal | ++ het | induced | neg | +++ | ++ | pos weak | 3533 | 93% | Tex-acute |

| 14 | 35 | No | IB | pT1bNxMx | 11 | 50 | Absent | + het | induced | ++ | + | ++ | pos | 2756 | 33% | Tex-mixed |

| 15 | 57 | Yes | IIIB | pT3bN0Mx | 7 | 20 | Present | + | constitutive | ++ | ++ het | neg | neg | 72 | 2% | Deserted |

| 16 | 49 | No | IIIC | pT3bN1Mx | 14 | 25 | Present | +++ | induced | neg | − | + | neg | 1631 | 33% | Tex-chronic |

| 17 | 60 | Yes | IB | pT1bN0Mx | 19 | 11 | Focal | + | induced | neg | − | ++ | pos | 984 | 50% | Tex-mixed |

| 18 | 71 | Yes | IB | pT1bN0Mx | 9 | 35 | Focal | + | constitutive | + | − | ++ | pos | 645 | 13% | Tex-mixed |

| 19 | 51 | Yes | IIIC | pT3bN1Mx | 19 | 60 | Present | +++ | constitutive | + | +/− het | ++het | neg | 1296 | 27% | Tex-chronic |

| 20 | 69 | Yes | IB | pT1bNxMx | 10 | 40 | Present | ± | induced | ++ | − | ++ | pos het | 666 | 21% | Deserted |

| 21 | 34 | No | IB | pT1bN0Mx | 3 | 10 | Absent | ++ het | constitutive | +++ | − | ++ | pos | 502 | 10% | Deserted |

NOTE: Abbreviations: FIGO: International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics staging system; TMN: standard for classifying the extent of spread of cancer; HPF: high power fields; het: heterogeneous; Total cells/sq mm: total number of cells in the core, based on DAPI staining; Tex: T cell exhausted. The predominant T cell phenotype was defined based on PD1 vs TCF7 expression: High PD1 – low/absent TCF7: acute exhaustion. Low PD1 – TCF7 present: chronic exhaustion. (See supplementary data).

The study has been approved by the Institutional Review Board Comitato Etico Brianza (https://www.asst-monza.it/comitato-etico), N. 3204, “High-dimensional single cell classification of pathology (HDSSCP)”, October 2019. Patients consent was obtained or waived according to article 89 of the EU general data protection regulation 2016/679 (GDPR) and decree N. 515, 12/19/2018 of the Italian Privacy Authority.

Two random 2 mm cores of non-necrotic, non-sclerotic, full tumor tissue for a total of 6.28 mm2 per case (equivalent to 40 HPF) were placed in a Tissue Microarray block (TMA model CK4500, Integrates Systems Engineering srl, Milan, Italy).

Multiple iterative labeling by antibody neodeposition (MILAN)

Dewaxed, antigen retrieved 3 µm sections were processed for indirect IHC or multiple labeling as previously described in detail24,25 and Supplementary Data.

Briefly, the sections were incubated overnight with optimally diluted primary antibodies in combination of four, washed and counterstained with four distinct fluorochrome-tagged secondary antibodies25. The slides, counterstained with DAPI and mounted, were scanned on an S60 Hamamatsu scanner (Nikon, Italia) at 20x magnification, after which the stains were removed with a beta-mercaptoethanol and sodium dodecyl sulphate mix, extensively washed and re-staind for the subsequent markers25. Re-staining a sample of antigens after about 30 cycles showed no consistent antigen loss and occasional increased antigenicity (Supplementary Fig. 1). The list of primary and secondary antibodies is available in the Supplementary Materials.

Preparation of immunofluorescent images for image analysis

Single.ndpi images for each case were registered via alignment of DAPI nuclear stained images with Fiji, saved as.tiff files and autofluorescence was subtracted25.

Two single cell masks were produced for each case with Cell Profiler (2.2.0)26 by segmentation of thresholded images: a DAPI mask encompassing all the nuclei and a mask obtained by the combined CD43, CD45, CD68 and CD163, henceforth named “targeted mask”. Regions of interest composed of small portions of dendritic-shaped cytoplasm were excluded digitally (see Supplementary Methods).

Comparison of the total cell yield and detailed high-dimensional phenotypic content obtained with the DAPI vs the targeted masks showed variable but constantly inferior cell number representation with the former (36%, 65%, 95%of the targeted mask-derived cells) and loss of minor phenotypic subsets by tSNE and Phenograph clustering (not shown). This because macrophages have reduced chromatin DAPI staining and do not provide enough contrast to be detected by threshold algorithms.

High-dimensional analysis

Individual masks and .tiff files from all cases were loaded in HistoCAT27, data obtained from the image analysis were processed by dimensional reduction and unsupervised clusterization algorithms, t-SNE and Phenograph plots were generated. Image analysis data were subsequently exported as .csv files. In order to analyze the infiltrate composition of individual cases, we developed an R script (Supplementary Methods) to systematically process all cells of all cases identified by image analysis. Phenoclusters were plotted as heatmaps (Supplementary Fig. 2) with a custom R script, to allow the identification of cell composition. Each heatmap was inspected for specific lineage- or function-associated markers, with the requirement that each defining marker needed to be expressed at high levels (clearly visualizable by a blue-red divergent color palette) in a third or more of the cells. A nine cell-type classification of inflammatory infiltrate was obtained by the inspection of all generated heatmaps and was based on criteria listed in Supplementary Table 1. The cell content of each phenogroup was used as the numerator to quantify the percentage of a given marker or phenotype.

Neighborhood analysis

An unbiased quantitative analysis of cell-cell interactions was performed using an adaptation of the algorithm described in27 for neighborhood analysis to systematically identify social networks of cells and to better understand the tissue microenvironment (Supplementary Methods).

PTEN status by FISH

In situ hybridization for PTEN was performed with the ZytoLight SPEC PTEN/CEN 10 dual color probe (ZytoVision GmbH, Germany) for the centromeric and the gene-specific regions of chromosome 10.

Results

The clinicopathologic data of the 21 sarcomas are reported in Table 1.

The inflammatory infiltrate

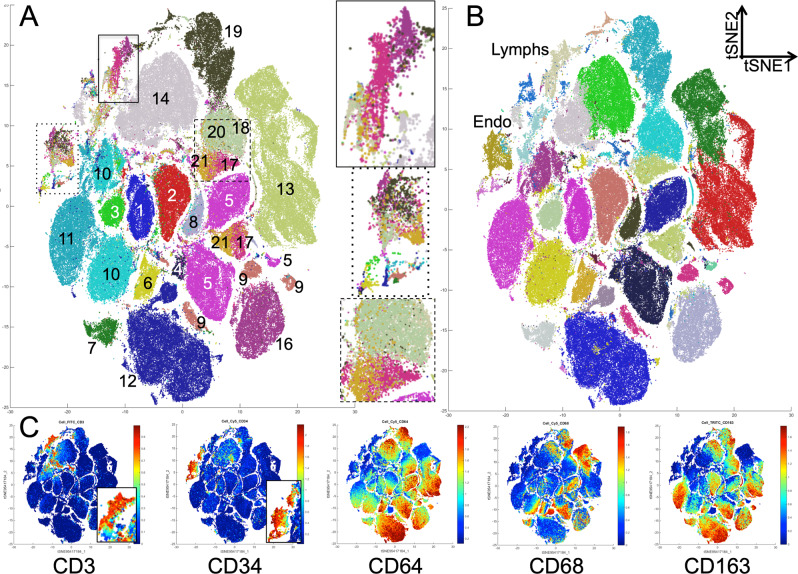

High-dimensional analysis of all 21 cases showed a majority of independent, non-overlapping clusters of myeloid phenotype, one or two per case, and smaller overlapping clusters, comprising T-cells and endothelial cells (Fig. 1). Only in four instances (cases N. 17,18, 20, 21) myeloid phenoclusters from separate cases did overlap (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

The lymphocyte and endothelial phenotypes are shared among the sarcoma cases but each one has an individual macrophage population. (A) tSNE plot of all 21 cases. Each case is color-coded and marked by the case number. On the right are enlarged portions highlighted on the plot. Note admixture of the cases in the boxed areas and in cases 17, 18, 20 and 21. Case 15, containing very few cells, is not marked. (B) Phenograph groups are plotted on the tSNE plot shown in A. Note the lymphocytes and the endothelial phenogroups, corresponding to the areas of case admixture shown in A. Macrophage populations for each case is represented by one to three phenogroups. (C) tSNE plots are highlighted with lymphoid (CD3; enlarged in the inset), endothelial (CD34; enlarged in the inset) and myelomonocytic markers.

Thus, the majority of the infiltrating inflammatory cells in each case is composed of macrophages whose phenotype reflects the unique biology of each tumor (Fig. 2), and a minor population of T-cells.

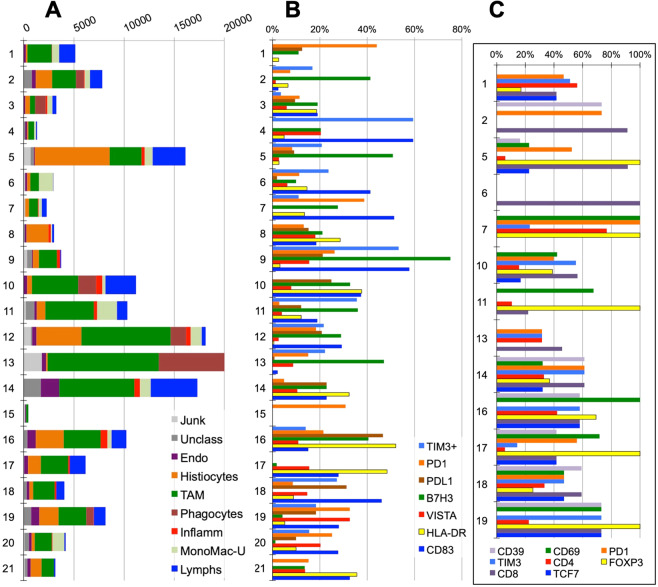

Figure 2.

Composite phenotype of the myelomonocytic and lymphoid infiltrate. (A) Absolute numbers of the inflammatory cells in each case per 6.28 mm2. Note the selective absence of CD16+TAMs in case 8, non neoplastic myometrium. Legend is shown in the bottom right of the graph. (B) Distribution of checkpoint protein and activation markers on myelomonocytic cells. Case 8, non neoplastic myometrium, has a small percentage of inflammatory cells with a coordinated activated phenotype; in all other cases, the expression of markers is uncoordinated. Legend is shown in the bottom right of the graph. (C) Distribution of relevant markers on lymphoid subsets. Note that only cases with enough lymphocytes are represented. CD39, CD69, PD1 and TIM3 are expressed as percentage of all CD3+ lymphocytes. FOXP3 percentages refer to the CD4+ subset. TCF7 refers to the CD8+ subset. Legend is shown at the bottom of the graph.

In order to understand the composition of the inflammatory infiltrate, each sarcoma case was analyzed separately in high-dimension (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3).

Lymphoid cells

TILs, almost exclusively T-cells and NK-cells, represents 3%-29% of the inflammatory infiltrate (0.3%-15.3% of the total sample cellularity), the rest being myelomonocytic cells (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Data). A few B cells in one case and no plasma cells were identified.

TILS were composed of 30% ± 22% CD4+, 62% ± 23% CD8+ and 9% ± 8% NK-cells.

CD4+ T-cells were 68% ± 36% FOXP3+, largely negative for activation markers (OX40, CD69,CD32). (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Data).

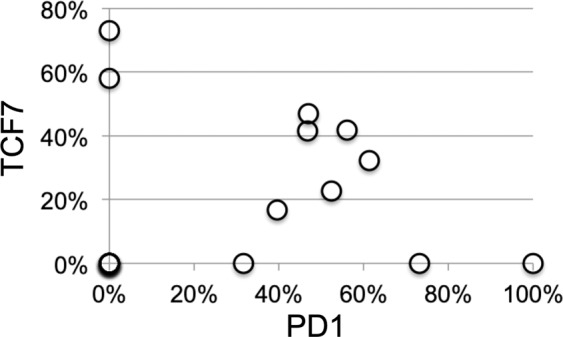

CD8+ T-cells were identified as distinct phenoclusters in about half of the cases, whenever a sufficient number of TILS was present. In those cases, often multiple phenotypically distinct phenoclusters were detected per case, displaying evidence of activation (CD69) and exhaustion (PD1, TIM3, VISTA, CD39). VISTA+ T-cells were observed in 8 cases, largely CD8+ TCF7−. TCF7, a transcription factor linked to resident memory phenotype and reactivation, was contained in 42% ± 18% of CD8+ cells, in an inverse relationship with PD1 (Figs. 3 and 4).

Figure 3.

Relationship between PD1+ and TCF7+ CD8+ T cells subsets. The coexistence of PD1+ TCF7− and of TCF7+ PD1− CD8+ T cells in each case is plotted as percentage of all CD8+ cells. Note that some samples show skewed expression by either population, others have a mixture of both. For complete data see Supplemental Data.

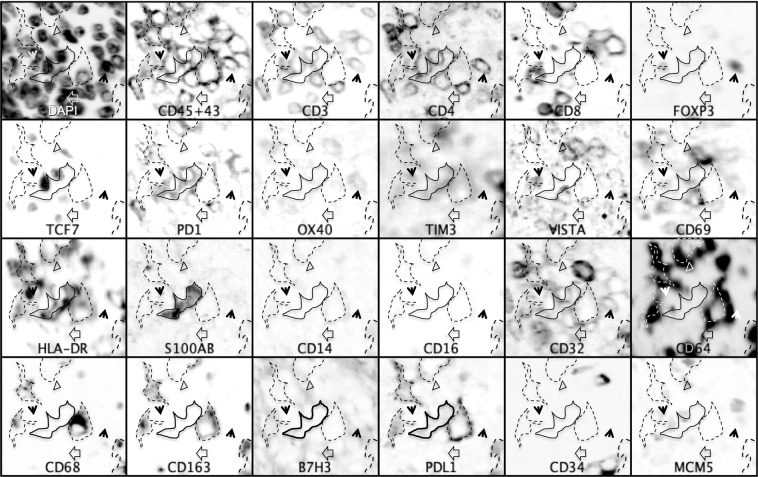

Figure 4.

T lymphocyte, macrophage and dendritic cell interactions in sarcomas. Inverted grayscale images of immunostained section detail from Case 14. PDL1+ macrophages expressing HLA-DR, CD16, CD64, CD68, CD163 and TIM3 are highlighted by a dashed line and are surrounded by PD1+ T cells, both CD8 and CD4. In the center, an HLA-DR+, S100AB+ CD14- dendritic cell is highlighted by a solid line. The empty arrowhead shows a CD8+, VISTA +, TCF7+ lymphocyte. The black arrowheads point to CD4+, FOXP3+, TCF7−, CD32±, OX40 ± regulatory T cells. The empty triangle points to a CD3+, CD8+, TCF7+, CD69+, VISTA+ lymphocyte. Note that TCF7 and FOXP3 are mutually exclusive. Negative markers are not represented. Image size 60 × 56 µm.

Lymphocytes expressing GranzymeB and Granulysin, partly CD8+, were identified as a separate phenocluster in some cases or as part of a single cluster of cells in samples with fewer TILs.

NK cells, defined as CD45+ CD3− and expressing GranzymeB and Granulysin, were a minority of lymphoid cells in abundant infiltrates only.

Myelomonocytic cells

Myelomonocytic cells represents 64% ± 13% of the infiltrate (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Data) and contained the most diversified cell type, often represented by multiple distinct phenogroups within each case (Fig. 5).

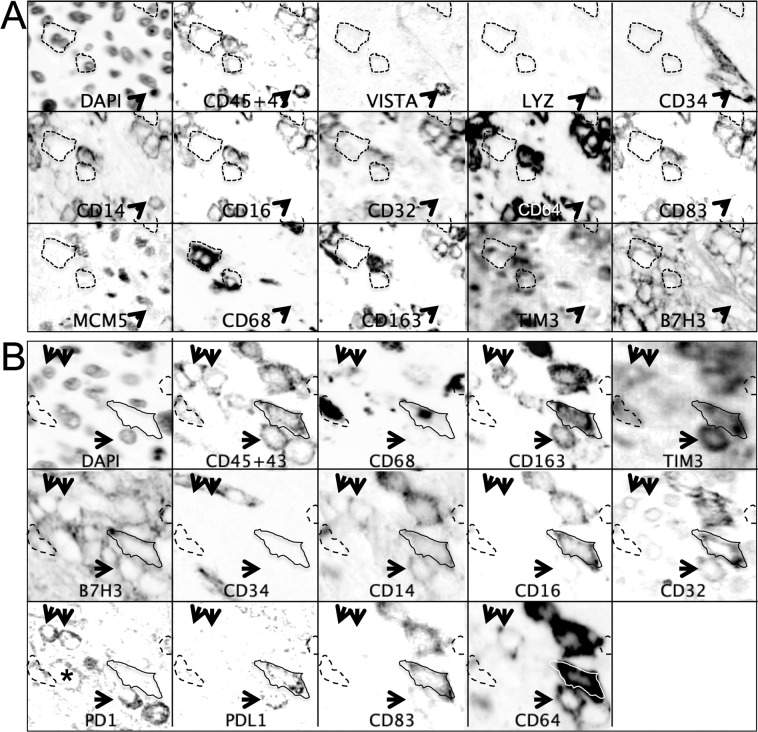

Figure 5.

Heterogeneity of macrophages in sarcomas. Inverted grayscale images of immunostained section detail from Case 13. (A) CD68+, CD14−, CD16−, CD64− CD163 phagocytes are highlighted by a dashed line. The arrowhead points to an endovascular VISTA+, LYZ+, CD14+ inflammatory monocyte. Negative markers are not represented. Image size 105 × 145 µm. (B) A solid line highlights an activated CD83+ PDL1+ TAM (CD14+, CD16+, CD32+, CD64+, CD68+, CD163+, TIM3+). The arrows point to PD1+ Monocytes/Macrophages undefined (CD14+, CD64±, CD68±, CD163±), one of which co-express PD1 and PDL1. The dashed outlines indicate PD1+, CD68+, TIM3± Phagocytes. Note a PD1+ isolated tumor cell (asterisk). Negative markers are not represented. Image size 76 × 67 µm.

The most distinctive group, named Tumor Associated Macrophages (TAM; 38% ± 13%) expressed CD16 and restricted lineage markers (CD68, CD163) and was consistently present in all tumor cases, but only occasionally in the non-neoplastic samples (Case #8 and 3 normal myometria, not shown). TIM3 expression among myelomonocytic cells was restricted to this cell type and to the inflammatory monocytes (see below).

The sarcomas contained CD16-negative histiocytes (20% ± 17%) and phagocytes (CD68+ CD163−; 5% ± 10%), these latter in 7/21 cases.

Phagocytes and Undefined Monocyte-Macrophagic cells (9% ± 12%) were characterized by the absence or spotty presence of several monocytic lineage markers (CD14, CD64, lysozyme/LYZ, CD163), PD1, PDL1, VISTA, CD83, B7H3.

All cases but five contained a small but very distinct population of small monocytic cells, often intravascular and proliferating, with a distinctive LYZ+ VISTA+ phenotype, which we defined “inflammatory” because of the association with the inflammatory infiltrate. These cells were often CD14+, CD16low or negative, sometimes TIM3+, but devoid of other myelomonocytic markers.

Spatial relationships between lymphoid and myelomonocytic cells

A neighborhood analysis between all phenotypic subsets revealed a substantial mutual avoidance across the phenotypes and clustering together of similar cell types, both at submicroscopic (<100 µm range) and at microscopic range (>100 µm range) (Supplementary Fig. 4). TILs avoid close contact with checkpoint-bearing macrophages (Supplementary Fig. 4 and Methods).

Tumor cells

Tumor cells had histocompatibility antigens staining patterns which could be defined as constitutive and induced; in the first case tumor cells were all positive or negative throughout the sections (Supplementary Fig. 5). In the second case, tumor cells admixed with the inflammatory infiltrate showed increased staining, compared to non-inflamed portions (Supplementary Fig. 5).

No HLA-DR was observed on tumor cells.

Tumor cells did not expressed most of the markers tested, including PDL1, with the notable exception of MCM5, IDO, B7H3 and Axl (see Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 5). Occasional PD1+ tumor cells were observed in some cases (Fig. 5B and Supplementary Data).

CD34+ endothelial cells stained for VISTA and B7H3 in about half of the cases, often in a subset28 (Supplementary Fig. 5).

The vast majority of the cases tested were either diploid or had loss of one copy of the PTEN gene in 3.1%-22.1% of the cells (Table 1), with only one case (case #7) carrying homozygous PTEN deletion in 13.2% of the cells.

Discussion

Data about the inflammatory infiltrate in untreated primary sarcomas are scarce. We detail here the composition of the innate and adaptive arm of the response of the host to a soft tissue tumor.

We found a variety of individual phenotypic profiles, not unlike other reports29,30.

In 11/21 cases we found a T-cell phenotype consistent with antigen exposure and acute or chronic stimulation, leading to exhaustion, mostly in tumors HLA Class I+.

The remaining 10 cases that we classified as “deserted” had usually less than 60 lymphocytes per mm2 and 0.3%-4.2% of total cellularity, with a phenotype suggestive of passer-by. These tumors were all negative or weakly expressing HLA-A,B,C, with two exceptions.

Each of the cases hosting antigen-experienced T-cell phenotypes displayed an unique combination of cell markers, which could be summarized as acutely exhausted CD8+ T cells, chronically exhausted CD8+ and FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells. These phenotypes were reminiscent of T-cells acutely exposed to a persistent antigen such as a virus or a neoantigen, bearing PD1, CD69, CD3931,32 and TIM333, and induced to anergy (exhaustion)3. Others expressed TIM3, lower levels of PD1 and TCF7 to a variable amount (17–73%), resembling exhausted CD8+ T-cells chronically exposed to an antigen, but in a resident memory state, susceptible of reactivation upon re-stimulation or therapeutic checkpoint inhibition reversal33,34. A mixture of these two cell types was sometimes present. It has been reported that up to a third of the cases displaying a CD8+ TCF7+ phenotype may benefit from a checkpoint blockade therapy33.

CD4+ T-cells had a FOXP3+ regulatory phenotype, occasionally as the minor population, as shown in other cancer models35.

The variability of T-cell phenotypes found between and within cases is suggestive of an ongoing editing of the adaptive immune response36, on a case-by-case basis.

The tumors we have examined are full blown malignant tumors of low mutation rate, yet, as shown in a single successful immunotherapy case22, this may induce an anti-tumor T-cell response. ULMs are also conspicuously devoid of HLA-DR+ CD14− dendritic cells and tertiary lymphoid structures, thus an adaptive response may occur in tumor-draining lymph nodes.

The failure of single-agent checkpoint inhibitor therapy in several published cases21–23 is at odd with our findings. One hypothesis is that the antigen to which the adaptive immune system responds is not a tumor antigen37. In the single ULM case studied22, T-cells were tumor antigen-specific and responded. None of our cases except one (Table 1) had homozygous deletion of PTEN, associated with an immunosuppressive tumor phenotype22.

Alternatively, failure to elicit an anti-tumor response may be caused by an independent immunosuppressive effect brought by the inflammatory infiltrate, chiefly the infiltrating macrophages.

Macrophages, and in particular tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) have been shown to mediate the suppression of an anti tumor response38,39. A dichotomic view of alternatively polarized macrophages has let to a more nuanced picture40, where there is a dynamic equilibrium between various defined stages of macrophage polarization.

As published by others16,41, we found a range of leukocytes (CD45+, CD43+) with myelomonocytic differentiation. Differently from lymphocytes, whose aggregate phenotype was conserved across all cases, myelomonocytic cells had unique, case-specific populations. A tissue-restricted secretome influencing macrophages has been described19; a similar effect may occur via monoclonal sarcoma cells, yielding a highly diversified, stimulus-driven differentiation reflecting individual tumor-specific microenvironment30,42,43. As shown by others30,38,44, the tumor harbors multiple subsets, often not found in the normal counterpart neither described before.

Furthermore, our neighborhood analysis of the macrophage subsets show both a submicroscopic and a microscopic local differentiation, producing a checkered pattern, which has to be kept in mind in order to sample the tissue adequately, as we did with larger (2 mm), multiple TMA cores.

Despite the large variety of individual phenotypes, by analyzing single cases with multiple markers we could identify five rather consistent groups present in all cases: histiocytes, phagocytes, TAM, inflammatory monocytes and Monocytes/Macrophages, undefined.

With the exception of TIM3, largely restricted to CD16+ TAMs, all the immuno-modulating markers were expressed in a minority of cells and were distributed across the five subsets.

We observed PD1, previously reported in circulating monocytes in HIV and in M2-type TAMs45 expressed on macrophages in 18/21 cases, occasionally with activation markers such as HLA-DR, OX40 and/or CD83. Interestingly, non-lymphoid PD1 expression in FFPE material could only be detected with UMAB197; this antibody has a broader reactivity than other PD1 antibodies and detects the molecule on B cells, monocytes and tumor cells, as reported by others45,46. Subtle subcellular variations in membrane staining by each antibody we tested (Supplementary Fig. 6) may has to do with the recognition of glycosylation-dependent, thus cell type restricted epitopes on PD1.

Consistent with the mouse data45, PD1 was expressed on 27 phenogroups, only two of them HLA-DR+ and CD83+.

Markers of activation (HLA-DR, CD83, OX40) were found on macrophages in almost all cases in all subsets, except on the inflammatory monocytes. Often activation was matched with proliferation (MCM5+).

More complex to understand was the expression of members of the immunological synapsis (PD1, PDL1, B7H3, VISTA), which, with the exception of TIM3, restricted to TAMs, were displayed by several subsets.

PDL1, expressed by myelomonocytic cells in 15/21 cases, is a ligand for PD1 and CD80 on cognate T-lymphocytes6,7 and a constitutively negative signaling molecules on macrophages47. Engagement of PDL1 induces proliferation, survival and upregulation of MHC Class-II, CD86 and cytokine secretion, promoting a proinflammatory phenotype47. In our PDL1-negative sarcoma cases, there is little relationship between activation and PDL1 expression in macrophages; of the 24 PDL1+ phenogroups, only seven express HLA-DR and eight CD83. These data hint at a lack of engagement of this molecule on macrophages.

VISTA-expressing macrophages have been described in prostate cancer48, particularly after chemotherapy; we do see this phenotype largely restricted to endocapillary LYZ+ VISTA+ monocytes, occasionally proliferating, which could be the seeding population from the bloodstream.

Human macrophages found in tumors may be able to present antigens to T-cells41, where the co-inhibitory molecules act to protect the macrophage from cytotoxicity during the encounter. We failed to demonstrate a statistically significative close interaction between T-cell subsets and checkpoint molecules-bearing macrophages, except for the suggestive images provided by tissue snapshots (Fig. 4). This may has to do with the highly motile properties of T-cells, whereby during an asynchronous activation of multiple immune synapsis, the challenged T-cells may distance themselves from the interactor by the time the phenotype has changed to reflect the effect of the challenge49.

In summary, we have described a variety of innate and adaptive immune cell phenotypes in ULMs, suggestive of antigen experience, and exploitable for a targeted immune intervention, despite the variability in phenotypes, particularly on the macrophage side.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work has been supported by Departmental University of Milano-Bicocca funds. MMB is employed by the Department of Medicine and Surgery of the University of Milano-Bicocca within a GlaxoSmithKline clinical research project BEL114054 (HGS1006-C1121), under which the Hamamatsu S60 digital scanner was obtained. AA was supported by the European Union Horizon 2020 grant SyMBioSys MSCA-ITN-2015-ETN #675585. Denis Schapiro (Harvard University, Boston, USA) graciously provided a pre-release copy of HistoCAT. We are grateful to Nicoletta Colombo, M.D. and Viviana Stufano, MSci (IEO) for clinical advice and contribution with the FISH analyses for PTEN, respectively.

Author contributions

G.C., M.M. and M.M.B. equally designed the experiments. M.M.B., M.F. and M.M. devised the image analysis algorithms. F.M.B., R.M. and S.C. provided essential reagents and tissues. F.M.B., A.A., M.M.B. and M.M. performed visual and digital image analysis as well as bioinformatic evaluation. M.F. provided a customized version of the AMICO software. M.M., M.M.B. and G.C. wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained an error in Affiliation 4, which incorrectly given as ‘Department of Experimental Oncology, European Institute of Oncology, via Adamello 16, 20139, Milan, Italy.’ The correct affiliation is ‘Department of Experimental Oncology, European Institute of Oncology, IRCCS, via Adamello 16, 20139, Milan, Italy.’

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Marco Manzoni and Maddalena M. Bolognesi.

Change history

8/5/2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1038/s41598-021-95855-1

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-57627-1.

References

- 1.Gregersen P, Behrens T. Genetics of autoimmune diseases–disorders of immune homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2006;7:917–928. doi: 10.1038/nrg1944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanahan D. Rethinking the war on cancer. Lancet. 2014;383:558–563. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62226-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen DS, Mellman I. Elements of cancer immunity and the cancer-immune set point. Nature. 2017;541:321–330. doi: 10.1038/nature21349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palucka AK, Coussens LM. The Basis of Oncoimmunology. Cell. 2016;164:1233–1247. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.01.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolchok JD, Chan TA. Cancer: Antitumour immunity gets a boost. Nature. 2014;515:496–498. doi: 10.1038/515496a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Topalian SL, Drake CG, Pardoll DM. Immune Checkpoint Blockade: A Common Denominator Approach to Cancer Therapy. Cancer Cell. 2015;27:450–461. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blank CU, Haanen JB, Ribas A, Schumacher TN. CANCER IMMUNOLOGY. The “cancer immunogram”. Science. 2016;352:658–660. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf2834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joyce JA, Fearon DT. T cell exclusion, immune privilege, and the tumor microenvironment. Science. 2015;348:74–80. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa6204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kowanetz M, et al. Differential regulation of PD-L1 expression by immune and tumor cells in NSCLC and the response to treatment with atezolizumab (anti-PD-L1) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:E10119–E10126. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1802166115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schumacher TN, Schreiber RD. Neoantigens in cancer immunotherapy. Science. 2015;348:69–74. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa4971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ribas A. Tumor immunotherapy directed at PD-1. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:2517–2519. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1205943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rizvi NA, et al. Cancer immunology. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Science. 2015;348:124–128. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Le DT, et al. Mismatch repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to PD-1 blockade. Science. 2017;357:409–413. doi: 10.1126/science.aan6733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGrail DJ, et al. Multi-omics analysis reveals neoantigen-independent immune cell infiltration in copy-number driven cancers. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:1317. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03730-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ock C-Y, et al. Genomic landscape associated with potential response to anti-CTLA-4 treatment in cancers. Nature. Communications. 2017;8:1050. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01018-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thorsson V, et al. The Immune Landscape of Cancer. Immunity. 2018;48:812–830 e814. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Varn FS, Wang Y, Mullins DW, Fiering S, Cheng C. Systematic Pan-Cancer Analysis Reveals Immune Cell Interactions in the Tumor Microenvironment. Cancer Res. 2017;77:1271–1282. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-2490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doig TN, et al. Coexpression analysis of large cancer datasets provides insight into the cellular phenotypes of the tumour microenvironment. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:469. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lavin Y, Mortha A, Rahman A, Merad M. Regulation of macrophage development and function in peripheral tissues. Nat. Rev. Immunology. 2015;15:731–744. doi: 10.1038/nri3920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Electronic address, e. d. s. c. & Cancer Genome Atlas Research, N. Comprehensive and Integrated Genomic Characterization of Adult Soft Tissue Sarcomas. Cell., 171, 950–965 e928, 10.1016/j.cell.2017.10.014 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Ben-Ami E, et al. Immunotherapy with single agent nivolumab for advanced leiomyosarcoma of the uterus: Results of a phase 2 study. Cancer. 2017;123:3285–3290. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.George S, et al. Loss of PTEN Is Associated with Resistance to Anti-PD-1 Checkpoint Blockade Therapy in Metastatic Uterine Leiomyosarcoma. Immunity. 2017;46:197–204. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Toulmonde M, et al. Use of PD-1 Targeting, Macrophage Infiltration, and IDO Pathway Activation in Sarcomas: A Phase 2 Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4:93–97. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cattoretti, G., Bosisio, F. M., Marcelis, L. & Bolognesi, M. M. Multiple Iteractive Labeling by Antibody Neodeposition (MILAN) Protocol Exchange, 10.1038/protex.2018.106 (2018).

- 25.Bolognesi MM, et al. Multiplex Staining by Sequential Immunostaining and Antibody Removal on Routine Tissue Sections. J. Histochemistry & Cytochemistry. 2017;65:431–444. doi: 10.1369/0022155417719419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carpenter AE, et al. CellProfiler: image analysis software for identifying and quantifying cell phenotypes. Genome Biol. 2006;7:R100. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-10-r100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schapiro D, et al. histoCAT: analysis of cell phenotypes and interactions in multiplex image cytometry data. Nat. methods. 2017;14:873–876. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seeber A, et al. High IDO-1 expression in tumor endothelial cells is associated with response to immunotherapy in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2018;109:1583–1591. doi: 10.1111/cas.13560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Egelston CA, et al. Human breast tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells retain polyfunctionality despite PD-1 expression. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:4297. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06653-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Azizi E, et al. Single-Cell Map of Diverse Immune Phenotypes in the Breast Tumor Microenvironment. Cell. 2018;174:1293–1308.e1236. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.05.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duhen T, et al. Co-expression of CD39 and CD103 identifies tumor-reactive CD8 T cells in human solid tumors. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:2724. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05072-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simoni Y, et al. Bystander CD8+ T cells are abundant and phenotypically distinct in human tumour infiltrates. Nat. Publ. Group. 2018;557:575–579. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0130-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sade-Feldman M, et al. Defining T Cell States Associated with Response to Checkpoint Immunotherapy in Melanoma. Cell. 2018;175:998–1013.e1020. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.10.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thommen DS, Schumacher TN. T Cell Dysfunction in Cancer. Cancer Cell. 2018;33:547–562. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saito T, et al. Two FOXP3(+)CD4(+) T cell subpopulations distinctly control the prognosis of colorectal cancers. Nat. Med. 2016;22:679–684. doi: 10.1038/nm.4086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jiménez-Sánchez A, et al. Heterogeneous Tumor-Immune Microenvironments among Differentially Growing Metastases in an Ovarian Cancer Patient. Cell. 2017;170:927–938.e920. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scheper W, et al. Low and variable tumor reactivity of the intratumoral TCR repertoire in human cancers. Nat. Med. 2019;25:89–94. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0266-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Franklin RA, et al. The cellular and molecular origin of tumor-associated macrophages. Science. 2014;344:921–925. doi: 10.1126/science.1252510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Biswas SK, Allavena P, Mantovani A. Tumor-associated macrophages: functional diversity, clinical significance, and open questions. Semin. immunopathology. 2013;35:585–600. doi: 10.1007/s00281-013-0367-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lawrence T, Natoli G. Transcriptional regulation of macrophage polarization: enabling diversity with identity. Nat. Rev. Immunology. 2011;11:750–761. doi: 10.1038/nri3088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Singhal S, et al. Human tumor-associated monocytes/macrophages and their regulation of T cell responses in early-stage lung cancer. Sci. Transl. Med. 2019;11:eaat1500. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aat1500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mosser DM, Edwards JP. Exploring the full spectrum of macrophage activation. Nat. Rev. Immunology. 2008;8:958–969. doi: 10.1038/nri2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xue J, et al. Transcriptome-based network analysis reveals a spectrum model of human macrophage activation. Immunity. 2014;40:274–288. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sconocchia G, et al. Tumor infiltration by FcγRIII (CD16)+ myeloid cells is associated with improved survival in patients with colorectal carcinoma. Int. J. cancer J. Int. du. cancer. 2011;128:2663–2672. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gordon SR, et al. PD-1 expression by tumour-associated macrophages inhibits phagocytosis and tumour immunity. Nature. 2017;545:495–499. doi: 10.1038/nature22396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thibult M-L, et al. PD-1 is a novel regulator of human B-cell activation. Int. immunology. 2013;25:129–137. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxs098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hartley GP, Chow L, Ammons DT, Wheat WH, Dow SW. Programmed Cell Death Ligand 1 (PD-L1) Signaling Regulates Macrophage Proliferation and Activation. Cancer immunology Res. 2018;6:1260–1273. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-17-0537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gao J, et al. VISTA is an inhibitory immune checkpoint that is increased after ipilimumab therapy in patients with prostate cancer. Nat. Med. 2017;23:551–555. doi: 10.1038/nm.4308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miller MJ, Hejazi AS, Wei SH, Cahalan MD, Parker I. T cell repertoire scanning is promoted by dynamic dendritic cell behavior and random T cell motility in the lymph node. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:998–1003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306407101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.