Abstract

Projections of climate change are available at coarse scales (70–400 km). But agricultural and species models typically require finer scale climate data to model climate change impacts. Here, we present a global database of future climates developed by applying the delta method –a method for climate model bias correction. We performed a technical evaluation of the bias-correction method using a ‘perfect sibling’ framework and show that it reduces climate model bias by 50–70%. The data include monthly maximum and minimum temperatures and monthly total precipitation, and a set of bioclimatic indices, and can be used for assessing impacts of climate change on agriculture and biodiversity. The data are publicly available in the World Data Center for Climate (WDCC; cera-www.dkrz.de), as well as in the CCAFS-Climate data portal (http://ccafs-climate.org). The database has been used up to date in more than 350 studies of ecosystem and agricultural impact assessment.

Subject terms: Climate-change impacts, Agriculture

| Measurement(s) | climate change • precipitation process • precipitation amount • consecutive dry months index per time period • temperature of air |

| Technology Type(s) | computational modeling technique |

| Factor Type(s) | spatial region |

| Sample Characteristic - Environment | climate system |

| Sample Characteristic - Location | Earth (planet) |

Machine-accessible metadata file describing the reported data: 10.6084/m9.figshare.11353664

Background & Summary

There is a variety of methods to project the impacts of climate change on agriculture and biodiversity. This diversity arises, at least in part, from the difficulty to couple local-scale agricultural or species distribution and abundance models with General Circulation Model (GCM) projections, which are inherently uncertain1–3. GCMs can only model earth processes in coarse grid-cells, which are unsuitable for local agricultural studies4,5. Most impact models for agriculture and biodiversity require high-resolution environmental data6,7.

Some authors (e.g. refs. 8–10) argue that original GCM resolutions should be kept so as not to bias or alter the physical plausibility of GCMs. Nevertheless, agricultural and natural landscapes have large spatial variations, particularly in the tropics, where orography, climate (especially precipitation), soils and crop management, vary across small distances11. The vast majority of agricultural and biodiversity researchers have used downscaling in impact studies6,12 (but see refs. 13,14). This is because conservation plans, niche models, crop models, and biodiversity evaluation require high resolution inputs. Downscaling and bias correction of climate model output produces data that allows local rather than regional or global projections of climate change and its impacts15,16. Planning, modeling and monitoring can therefore be at municipality, watershed or other sub-national scales17–21.

Downscaling techniques range from smoothing and interpolation of GCM anomalies19, to statistical modeling, neural networks, and regional dynamical climate modelling22. They differ in accuracy, output resolution, computational requirements and climatic science robustness. Dynamical and statistical downscaling are the most frequently used techniques to downscale GCMs for agricultural impact studies23,24. Bias-correction, on the other hand, focuses on using different types of statistical techniques to make the climate model output more realistic, and, in many cases (i.e. when observations are available at high spatial resolution), also of greater spatial resolution15,25.

Dynamical downscaling uses Regional Climate Models (RCMs) to increase the resolution of climate projections, with boundary and initial conditions from a GCM as inputs26–28. RCMs consider more detailed specifications of land use and water bodies, simulate mesoscale processes in more detail than GCMs, and, in some cases, are capable of explicitly resolving convective rainfall processes29,30. RCMs are computationally expensive, and require physical understanding of the climate system, time and storage to obtain a single scenario-by-period output21. RCM outputs have been made available recently through the Coordinated Regional Climate Downscaling Experiment (CORDEX)31. However, given their computational cost, only a handful of RCM–GCM combinations can realistically be used to produce future high-resolution climate change projections32,33. Moreover, RCM outputs are also subject to climate model error from both the structure of the RCM and the boundary conditions of the driving GCM30,34.

Statistical downscaling (SD) is an easier and computationally less expensive method to develop climate change projections with high spatial resolution35. SD typically consists of two steps, (i) developing a statistical relationship between local climate variables and large-scale predictors, and (ii) the application of those statistical models onto future GCM output to derive future downscaled data36. SD assumes that climates will only change at coarse scales and that relationships between variables at local scale remain relatively constant in the future period30,36. Bias correction (BC) is yet simpler than SD, and is typically implemented by applying a ‘change factor’ or ‘delta’ derived from a GCM onto the historical observations15,35. BC can also be implemented by applying a ‘nudging’ factor to the climate model output, or by quantile-mapping of climate model outputs onto observations16,37. Since no GCM is a perfect representation of the true climate, BC seeks to correct those attributes in the climate model output that are known or hypothesized to be important for impacts modeling4,15,38.

Here, we used BC to develop the CCAFS-Climate global database of bias corrected climate change projections. To develop the database, we applied the delta method (a simple BC) to 35 Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 5 (CMIP5) models39, and four representative concentrations pathways (RCPs)40. We used the delta method since we focus on providing data for 30-year mean climate conditions, and because the method has already been shown to be robust to correct mean climate conditions in other regions15. For each GCM, we used the 30-year future periods named as 2030s (2020–2049), 2050s (2040–2069), 2070s (2060–2089) and 2080s (2070–2099) and three climate variables (mean monthly maximum and minimum temperatures and monthly rainfall). We used the WorldClim global climate database11 as the reference set of observations for the historical period. The database is freely available through the World Data Center for Climate (WDCC; cera-www.dkrz.de)41, as well as through the CCAFS-Climate data portal (http://ccafs-climate.org). We evaluate the method to quantify the advantages of using bias-corrected climate data in comparison with the original GCM outputs, using a perfect sibling framework (see Methods). Furthermore, we summarize existing applications of the high-resolution gridded datasets produced here in environmental studies characterizations to assess the impacts of climate change on agricultural production, biodiversity, conservation, and water resources. Finally, we discuss the assumptions and limitations in the methods and data.

Methods

CCAFS-Climate was produced by bias-correcting the original GCM outputs using spatial interpolation of the anomalies or deltas (differences between future and current climates). To this aim, anomalies (‘deltas’) are first calculated using GCM output as the difference between future and historical periods, and then interpolated onto a 30 arc-s grid. We then applied the interpolated anomalies to the baseline climate of the WorldClim high resolution (30 arc-s) surfaces11. This method is called delta change or change factor42,43 (DC). Our implementation of DC seeks to correct the modeled mean climate from the climate models, which is a critical aspect in understanding crop and species distributions and productivity under climate change44,45, while also providing results at high spatial resolution.

Data acquisition

Present-day observed climatology

We used the high spatial resolution (30 arc-s, ~1 km at the Equator) climate datasets of WorldClim11. We chose WorldClim due to its high spatial resolution, wide use (i.e. more than 15,000 citations), and quality11. WorldClim used data from more of 47,000 weather stations from 1950–2000 worldwide as input to produce interpolations. WorldClim used the thin-plate splines algorithm46 to interpolate mean monthly maximum and minimum temperatures, and monthly precipitation. There are other global datasets for both temperature and precipitation47, but they use fewer locations or have coarser spatial resolution. Moreover, WorldClim compares well to other global datasets, especially in areas of high weather station density11,48,49.

General circulation models data

The Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 5 (CMIP5)39, coordinated by the World Climate Research Programme in support of the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report (AR5)50, provides simulations from state-of-the-art GCMs. CMIP5 provides, for a large number of models, climate projections for all four Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs)39.

We used present day simulations (1961–1990) and future projections (2010–2100) of global climate at original GCM resolution (70–400 Km) from a total of 35 GCMs, and all RCPs, namely, RCP 2.6, 4.5, 6.0 and 8.5 (Table 1)40. GCM data included monthly time series of maximum temperature, minimum temperature and precipitation flux. All GCM data were downloaded from the CMIP5 web data portal at https://esgf-node.llnl.gov/projects/cmip5/. Not all GCM-by-RCP combinations were available (see Table 1).

Table 1.

CMIP5 Global Climate Models.

| Model (Reference) | Institute | RCP | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.6 | 4.5 | 6.0 | 8.5 | ||

| BCC-CSM1.191–93 | Beijing Climate Center, China Meteorological Administration | O | O | O | O |

| BCC-CSM1.1(m)91–93 | O | O | O | O | |

| BNU-ESM94 | Beijing Normal University | O | O | X | O |

| CCCMA-CanESM295,96 | Canadian Centre for Climate Modelling and Analysis | O | O | X | O |

| CESM1-BGC97,98 | National Science Foundation, Department of Energy, National Center for Atmospheric Research | X | O | X | O |

| CESM1-CAM597 | O | O | O | O | |

| CNRM-CM599 | Centre National de Recherches Meteorologiques and Centre Europeen de Recherche et Formation Avancees en Calcul Scientifique | O | O | X | O |

| CSIRO-ACCESS1.0100,101 | Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization (CSIRO) and Bureau of Meteorology (BOM), Australia | X | O | X | O |

| CSIRO-ACCESS1.3100,101 | X | O | X | O | |

| CSIRO-Mk3.6.0102 | Queensland Climate Change Centre of Excellence and Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization | O | O | O | O |

| EC-EARTH103 | European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) | X | X | X | O |

| FIO-ESM104 | The First Institute of Oceanography, State Oceanic Administration, China | O | O | O | O |

| GFDL-CM3105,106 | NOAA Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory | O | O | O | O |

| GFDL-ESM2G107 | O | O | O | O | |

| GFDL-ESM2M107 | O | O | O | O | |

| GISS-E2H108,109 | NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies USA | O | X | O | O |

| GISS-E2HCC108,109 | X | O | X | X | |

| GISS-E2R108,109 | O | O | O | O | |

| GISS-E2RCC108,109 | X | O | X | X | |

| INM-CM4110 | Institute of Numerical Mathematics of the Russian Academy of Sciences | X | O | X | O |

| IPSL-CM5A-LR111 | Institut Pierre Simon Laplace | O | O | O | O |

| IPSL-CM5A-MR111 | O | O | X | O | |

| IPSL-CM5B-LR111 | X | X | X | O | |

| LASG-FGOALS-G2112 | Institute of Atmospheric Physics (LASG) and Tsinghua University (CESS) | O | O | X | O |

| MIROC-ESM113 | University of Tokyo, National Institute for Environmental Studies and Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology | O | O | O | O |

| MIROC-ESM-CHEM113 | O | O | O | O | |

| MIROC-MIROC5114 | O | O | O | O | |

| MOHC-HadGEM2-CC115,116 | UK Met Office Hadley Centre | X | O | X | O |

| MOHC-HadGEM2-ES115,116 | O | O | O | O | |

| MPI-ESM-LR117 | Max Planck Institute for Meteorology | O | O | X | O |

| MPI-ESM-MR117 | O | X | X | O | |

| MRI-CGCM3118,119 | Meteorological Research Institute | O | O | O | O |

| NCAR-CCSM4120 | US National Centre for Atmospheric Research | O | O | O | O |

| NCC-NorESM1-M121 | Norwegian Climate Centre | O | O | O | O |

| NIMR-HADGEM2-AO115,116 | National Institute of Meteorological Research and Korea Meteorological Administration | O | O | O | O |

| Total | 26 | 31 | 19 | 33 | |

Delta method downscaling

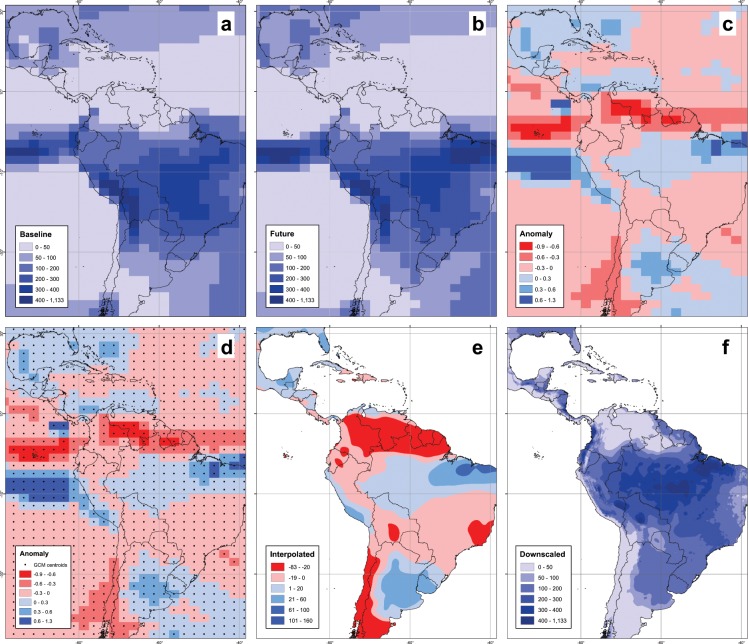

The DC approach presented here is a simple form of BC in which a change factor or ‘delta’ is derived from the GCM, and then added onto the observations (WorldClim). The purpose of our dataset is to provide a bias-corrected and high-resolution representation of the mean climates, and for this reason we employ the DC approach. The change factor is defined as the difference between the long-term (30-year) mean of a climate variable in the future and the historical period. The method comprises the following steps: (1) calculation of 30-year averages for present-day simulations and 4 future periods; (2) calculation of anomalies as the absolute difference between future and present day values in temperatures (minimum and maximum) and proportional differences in total precipitation; (3) interpolation of these anomalies using centroids of GCM grid cells as points for interpolation; and (4) addition of the interpolated gridded data to the current climates from WorldClim (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Illustration of the downscaling process with January total precipitation using the GFDL-CM3 GCM pattern. (a) Baseline data, (b) future data for 2050s (2040–2069 average), (c) delta or anomaly by 2050s, (d) delta or anomaly by 2050s with GCM centroids (points) overlaid, (e) 30 arc-s interpolated anomaly, and (f) future downscaled climate surface at 30 arc-second spatial resolution. Values in mm/month.

Using the full present-day monthly time-series from the GCM (Sect 0), we thus calculated 30-year means as a baseline (1961–1990), for each GCM and variable. Next, we calculated the 30-year means for each RCP and future period. The future periods are: 2020–2049 (2030s), 2040–2069 (2050s), 2060–2089 (2070s) and 2070–2099 (2080s). For each future period, we calculated the anomaly (delta change) with respect to the baseline climate of the same GCM for each variable and month. We used absolute differences for temperatures (Eq. 1) and relative changes for precipitation (Eq. 2).

| 1 |

| 2 |

where, ΔXi is the delta change, XCi the 30-year mean of the variable in the current climate, and XFi the 30-year mean of the variable in the future climate of each GCM in the month i.

The use of relative changes for precipitation avoids arriving at negative values when applying GCM delta values onto observed WorldClim precipitation. We note that in very dry areas (i.e. monthly historical precipitation close to zero) relative changes could produce unreasonably large relative precipitation increases (e.g. Sahara Desert). To avoid this, we made two adjustments: (1) we set a threshold of 0.1 mm month−1 both for current and future GCM values, which prevents indetermination in Eq. 2; and (2) we truncate the top 2% of anomaly values to the 98th percentile value in the empirical probability distribution for each anomaly gridded dataset. Truncation avoids situations in which very low values in the denominator in Eq. 2 lead to very high delta values, which when applied onto WorldClim may lead to unrealistically high values for the future precipitation.

We next apply a thin-plate splines interpolation (TPS)51,52 to derive 30 arc-s anomalies. TPS have been used extensively in climate science11,46,53,54. The procedure ensures a smooth (continuous and differentiable) surface together with continuous, first-derivative surfaces. Rapid changes in gradient or slope (the first derivative) may occur in the vicinity of the data points. The spline method performs a two-dimensional minimum curvature spline interpolation on a point dataset resulting in a smooth surface that passes exactly through the input points.

Original GCM grid cells are transformed to points with position equal to the centroid of the grid cell, and the TPS interpolation is applied across these points. We used 8 points as neighborhood, though using less (4) or more (12) produced similar results. Interpolations at coastlines are done using relevant ocean grid points from the GCM, only when strictly necessary. The resolution of the resulting interpolation is 30 arc-s, for consistency with WorldClim. This interpolation procedure yields surfaces of changes in climates for each of the 12 months and 3 variables. We produce a total of 36 interpolated surfaces of monthly changes in climates per GCM, RCP and period.

We add anomalies to the baseline climates from WorldClim to get the downscaled future. In the case of temperatures (minimum and maximum temperatures) for each pixel, the anomalies in degree Celsius are simply summed to the actual value in degree Celsius reported in WorldClim (Eq. 3). For precipitation, we use the absolute value of the change relative to the baseline period in order to avoid monthly precipitation values going below 0, and maintain homogeneities with WorldClim (Eq. 4).

| 3 |

| 4 |

where, XOBSi is the current climate from observations (i.e. WorldClim); ΔXIi is the interpolated anomaly (delta); and XDCi is the downscaled future climate of each GCM in the month i.

After calculating the corresponding future values for each of the 36 interpolated surfaces, we calculate mean temperatures, assuming a normal distribution in temperatures during the day, as the average of maximum and minimum temperatures.

Beyond the monthly data, we also calculated 19 bioclimatic indices55,56 (see full list in Table 2), which have become standard for species distributions modeling for wild and crop species57,58. These indices provide descriptions of annual trends (i.e. annual mean temperature, total annual rainfall), seasonality (temperature range, temperature and precipitation standard deviations), and stressful conditions (precipitation during dry or wet periods, temperatures during hot and cold periods).

Table 2.

List of bioclimatic variables derived from monthly data.

| Variable name | Description | Units |

|---|---|---|

| bio_1 | Annual mean temperature | °C |

| bio_2 | Mean Diurnal Range | °C |

| bio_3 | Isothermality | — |

| bio_4 | Temperature Seasonality | °C |

| bio_5 | Max Temperature of Warmest Month | °C |

| bio_6 | Min Temperature of Coldest Month | °C |

| bio_7 | Temperature Annual Range | °C |

| bio_8 | Mean Temperature of Wettest Quarter | °C |

| bio_9 | Mean Temperature of Driest Quarter | °C |

| bio_10 | Mean Temperature of Warmest Quarter | °C |

| bio_11 | Mean Temperature of Coldest Quarter | °C |

| bio_12 | Total annual precipitation | mm |

| bio_13 | Precipitation of Wettest Month | mm |

| bio_14 | Precipitation of Driest Month | mm |

| bio_15 | Precipitation Seasonality (Coefficient of Variation) | mm |

| bio_16 | Precipitation of Wettest Quarter | mm |

| bio_17 | Precipitation of Driest Quarter | mm |

| bio_18 | Precipitation of Warmest Quarter | mm |

| bio_19 | Precipitation of Coldest Quarter | mm |

Data Records

Our datasets comprise the most comprehensive bias-corrected set of climate change scenarios from IPCC AR5. The DC approach was applied over 35 different GCM outputs (Table 1) from CMIP539,50, four RCPs, and four different 30-year periods, including: 2030s (2020–2049), 2050s (2040–2069), 2060s (2050–2079) and 2080s (2070–2099). The combination of all these settings produce a total of 436 different global scenarios. Each scenario comprises four variables at a monthly time-step: mean, maximum, minimum temperature, and total precipitation, in addition to a set of 19 bioclimatic variables. We provide data at four spatial resolutions, namely, 30 arc-s (~1 km at the Equator), 2.5 arc-min (~5 km), 5 arc-min (~10 km), and 10 arc-min (~20 km). We pack the twelve months of the year for each variable and resolution in Zip archives containing ESRI-Arc/Info binary grids (for 2.5, 5 and 10 arc-min datasets) and ESRI-ASCII grids (all resolutions). Moreover, we offer datasets by tiles (18 tiles in total) to facilitate the data retrieval for users who seek only regional data. All the possible combinations produce 57,552 records which are freely available in a digital table59. The complete dataset set is ~7 TB in size. All data are freely available at the World Data Center for Climate (WDCC) repository41.

Technical Validation

The DC strategy focuses on identifying the aspects of the climate model that need correction (in our case the long-term mean), and then uses the observations to find a correction factor for the quantities of interest (e.g. long-term average monthly mean temperature). To illustrate the method, a comparison of the Probability Density Function (PDF) between observations, GCM-historical, GCM-future, and downscaled data is shown in Fig. 2 for precipitation and 3 for temperature, respectively. We chose for this example the highest emission scenario RCP 8.5 which displays greater differences than other scenarios and 2050s –a period of importance for adaptation and policy-making decisions in agriculture both from an adaptation and mitigation perspective, as it is the period around which global mean temperature is projected to exceed 2 °C above pre-industrial levels60–63.

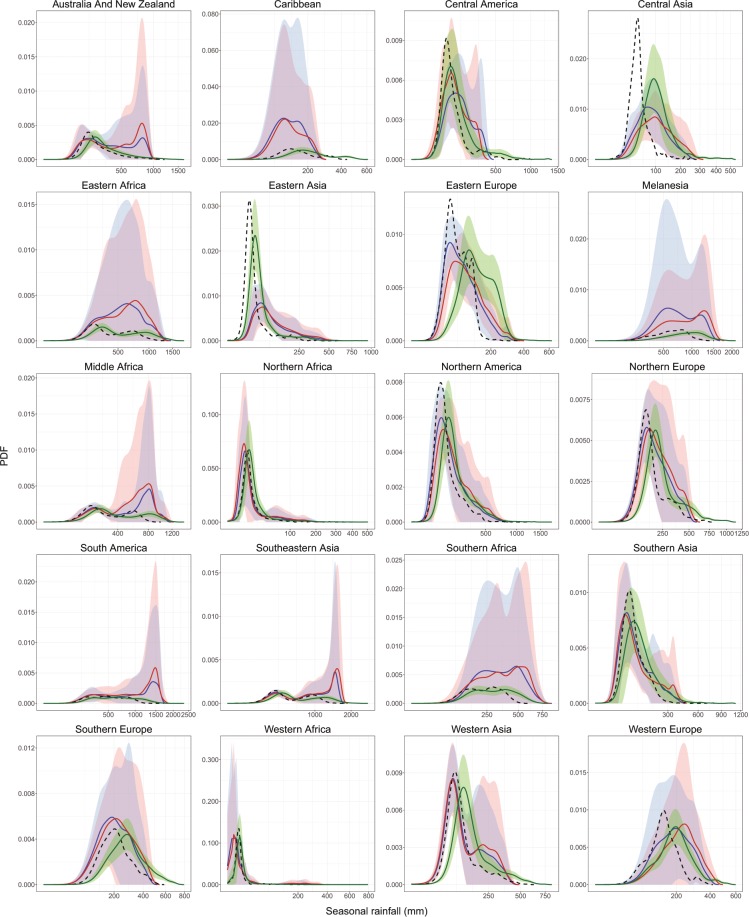

Fig. 2.

Probability density functions (PDF) of seasonal rainfall for December-January-February season in comparison with observations. The continuous lines belong to PDF average and the shading shows the average ± one standard deviation, for all GCM-future (red), GCM-historical (blue) and DC GCM (green). Dotted line is average PDF for the observations (i.e. WorldClim). The definition of areas of the world follows the United Nations Statistics Division (UNSD)122.

The DC approach changes much of the distribution of the mean seasonal temperature and seasonal rainfall in the majority of the world zones studied. In areas such as Australia and New Zealand, South America and Southeast Asia, the DC approach makes both the mean, the variance and the overall PDF distribution more consistent with that of WorldClim. In the Caribbean, Melanesia, Southern Africa, the method appears to correct the systematic underestimation of seasonal rainfall under 500 mm (Fig. 2). These high-frequency and low-intensity events are frequently referred to as the ‘drizzle problem’ in GCMs34,64,65. In Central America, GCMs tend to overestimate the distribution of rainfall values under 500 mm but also are not capable of simulating rainfall above 500 mm. In that case, the DC method modifies the variance, bringing it closer to that of WorldClim, although it can introduce some extreme high values that are unlikely to occur.

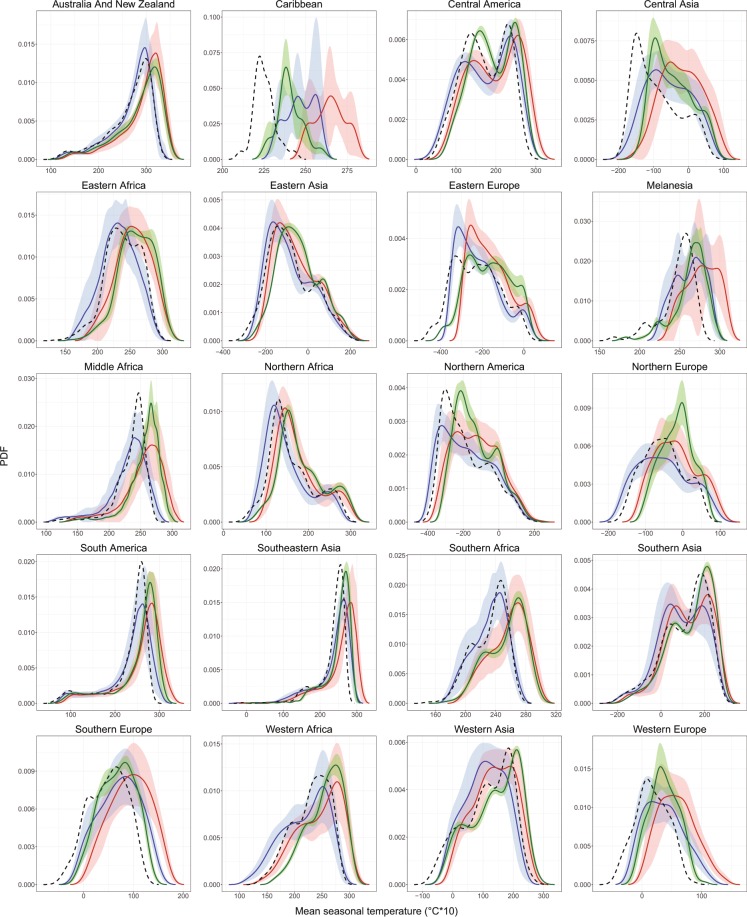

As for precipitation, historical uncorrected GCM outputs are not capable of representing the PDF of the temperature observations in many cases (Fig. 3). For example, GCMs do not reproduce very low temperatures such as those in Eastern Europe, and low tropical temperatures (Melanesia). The DC approach brings the shape of the PDF of the future projections closer to that of the observed PDF, therefore likely reducing model error. For instance, for temperatures in the Caribbean, the mean of the PDF is changed making so that it is closer to the observations. DC also helps to reproduce very low values (e.g. Eastern and Southern Africa) that are not observable in the original GCM.

Fig. 3.

Probability density functions (PDF) of seasonal mean temperature for DJF season in comparison with observations. The continuous lines belongs to PDF average and the shading shows the average ± one standard deviation, for all GCM-future (red), GCM-historical (blue) and DC GCM (green). Dotted line is average PDF for the observations (i.e. WorldClim). The x-axis is multiplied by 10 for consistency with the data provided online, which is multiplied by 10 to reduce storage space needs. The definition of areas of the world follows the United Nations Statistics Division (UNSD)122.

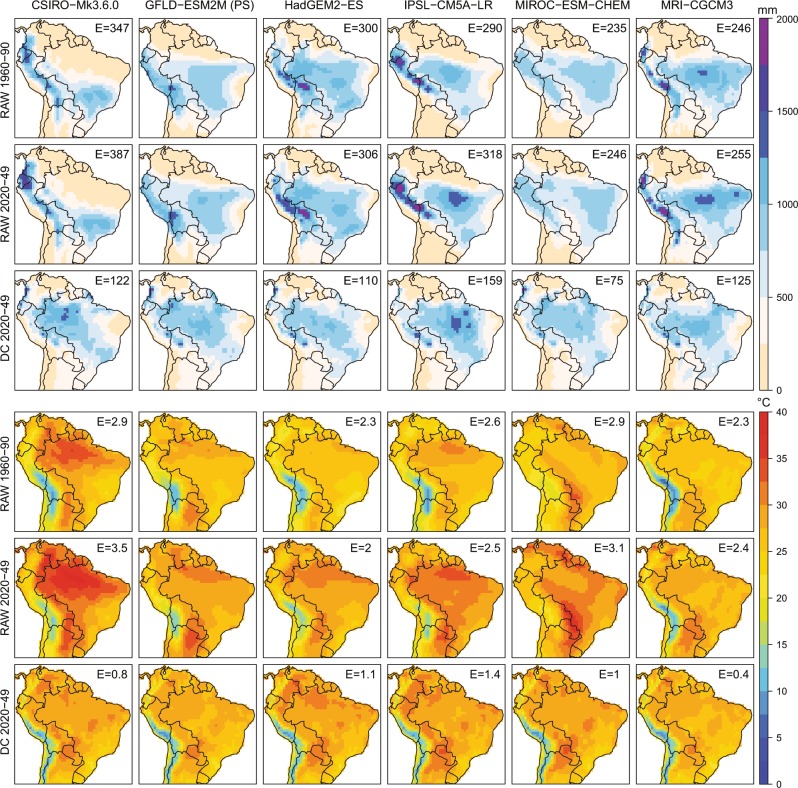

In addition to the comparison of the PDF we tested the DC method by means of a Perfect Sibling evaluation (PS)15,66. Since no observations of future climate exist, we used one GCM as pseudo-observations, to then try to predict the future evolution of that simulation using another independent simulation (Fig. 4). We selected the GFDL-ESM2M as the reference simulation (the ‘perfect sibling’ or ‘truth’) and compared with the same data from other 5 GCMs in the periods 1960–1990 and 2040–2069. Raw refers to the uncorrected data and DC after applying the bias-correction approach. We assessed the skill using the RMSE between the perfect sibling and the other GCMs. For this example, we selected South America, but we performed the evaluation for other regions and combinations of GCMs (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Demonstration of the DC calibration methodology using a range of GCM simulations. Top maps (in blue color scale) show results for DJF seasonal rainfall, and bottom maps (in rainbow color scale) for DJF mean seasonal temperature. GFDL-ESM2M is selected as the “prefect sibling” for verification against the calibrated projections using other GCM data. The RMS error for the region shown is given as the E value in the top-right of the maps.

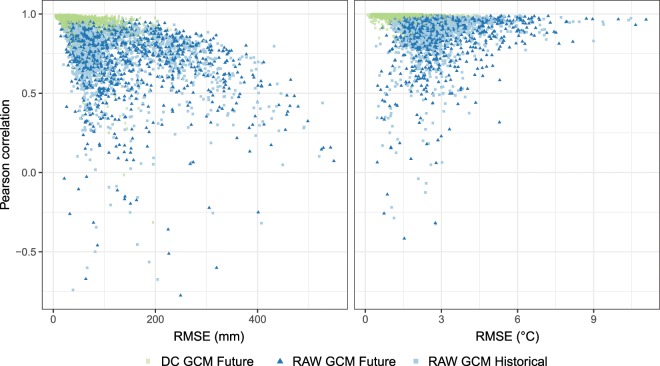

Fig. 5.

Error evaluation considering all seasons, regions and different combinations of the “Perfect Sibling” model. Left panel shows precipitation, and right panel temperature. Model error, measured using the RMSE and Pearson correlation coefficient are shown for the uncorrected GCMs in the historical period (light blue squares), the uncorrected GCMs in the future (dark blue triangles) and DC calibrated dataset (green circles).

Both for the example simulation and for all possible combinations, the RMSE decreases significantly applying DC compared with the uncalibrated case. For the South America region the error fluctuates between E = 246–387 mm season−1 in the raw case and E = 122–159 mm season−1 (i.e. roughly 50% lower) in the DC case for DJF seasonal precipitation, and between E = 2–3.5 °C season−1 in the raw case and E = 0.4–1.4 °C season−1 in the DC case for DJF seasonal mean temperature (Fig. 4). The correlation between corrected GCMs and the perfect sibling, considering all the 2,400 possible combinations (among GCMs, seasons, regions), is above 0.8 in virtually all cases (i.e. seasons, regions and GCMs) for both precipitation and temperature (Fig. 5, left). The RMSE for the same combinations is less than 200 mm season−1 (1.5 °C) for more than 90% (75%) of the cases for precipitation (temperature) (Fig. 5, right).

Overall, the evaluation suggests that DC produces reliable and robust future projections of the means of climate variables for use in impact assessment. However, we note that while mean seasonal conditions play a significant role in the eco-physiology of crops and wild species45,67, there are other aspects of climate projections that influence crops and biodiversity including the frequency and intensity of drought and/or hot spells, or the occurrence 1-day extreme precipitation events15,68,69. Some of these aspects, however, are not adequately simulated by GCMs70,71. More work is thus required to develop better models that can accurately simulate these events, or that generate plausible scenarios that can then be used into agricultural and species models. Additionally, other methods of bias-correction and downscaling exist (e.g. refs. 25,30,37) and can correct errors in the temporal aspects of GCM simulations. Future studies and datasets may focus exploring and comparing additional methods to DC or different implementations of DC (e.g. using different interpolation methods), especially as CMIP6 model outputs become available to the public, as different methods can produce varying results and thus add to the ‘uncertainty cascade’ in impacts modeling16,72.

Usage Notes

Recommendations to users

The World Data Center for Climate (WDCC) portal provides the open access high-resolution climate data presented in this article, with an associated permanent DOI (10.26050/WDCC/CCAFS-CMIP5_downscaling)41. In addition, the CCAFS-Climate portal (www.ccafs-climate.org) also provides the data, and includes useful explanations and documentation to help users understand the technical principles of the downscaling techniques and other useful information about the data. It also includes a Contact Us section providing user support via e-mail and an About Us section with institutional information and a quick guide to citing the data in peer-reviewed publications.

We provide data at four different resolutions (30 arc-s, 2.5 arc-min, 5 arc-min, and 10 arc-min), and encourage users of these data to understand the assumptions we made in producing them. The data provided here are intended to assess the impacts of changes in the mean climate state, especially as it relates to temperatures and precipitation, and the derived bioclimatic indices. For applications concerning changes in weather characteristics, extreme events, or interannual variability, users should find other datasets or bias-correction methods that address such aspects. As a whole, our assumptions might lead to uncertainties, and therefore, we suggest that users of these data perform a detailed uncertainty analysis in order to determine if these data in fact fulfil their requirements. We caution users regarding the uncertainties involved in our processes, and in no case should users understand these projections as future predictions of climate for particular places. Rather, the data should be understood as high-resolution and bias-corrected future projections in which a compromise is made between climate model physics and scale of analysis. It is noteworthy that as progress continues in climate modelling in the next decades, we expect that downscaling and bias-correction may no longer be required for using climate model output to assess the impacts of climate change.

Processing and storage capacity in research centers making use of these datasets might also be a limiting factor when using these data. We therefore suggest research centers to download the appropriate resolution datasets that suit their studies. We note that significant differences are of course present between 30 arc-s and 10 arc-min spatial resolutions. The former is the original WorldClim resolution, providing considerable detail on climatic patterns according to orography, whilst the latter, retrieves a credible high-resolution dataset, but with less level of detail.

Applications in agro-environmental research

From 2014 to date, CMIP5 DC downscaled data from the CCAFS-Climate portal have been downloaded by nearly 1,400 users in more than 186 countries around the world. Approximately 394,000 data files have been downloaded, amounting to 119 TB of data. Users of the data include representatives from national government research institutions and the NGO sector as well as the research community. Moreover, to date more than 300 journal papers, 10 book chapters, and 40 theses or reports have cited the data shown here. These data have been used for a wide variety of purposes; some examples are summarized below.

Guo et al.73 used DC data to investigate the current status and distribution of the Quiver tree Aloe dichotoma in southern Africa and assess the projected future changes of its habitat under different climatic scenarios. The tree provides moisture to a wide variety of mammals, birds and insects, and its conservation is critical to maintaining the local ecosystem in the future. Jennings and Harris74 used DC data to identify specific climate and vegetation parameters for anticipating how, where and when ecosystem vegetation may transform with climate change across the southwestern USA. CCAFS-Climate portal data were used in conjunction with a weather generator to map environmental suitability for the Zika virus, showing that over 2.17 billion people in the tropics and sub-tropics live in areas suitable for the virus and its vector75.

The CCAFS-Climate portal data have been widely used to help identify analogue sites. Comparing present-day farming systems with their future analogues can facilitate the exchange of knowledge between farmers in different locations who share common climate interests and allows adaptation strategies and technologies to be tested and validated76. Over the last several years, more than 15,000 farmers have been testing new seed varieties in seven districts of India as a component of improved local seed systems, by selecting and testing varieties identified using climate analogue analysis, thereby enhancing smallholders’ resilience to climate change77. In another example, the International NGO Concern Worldwide is using analogue analysis to identify adaptation options and investment strategies in Chad and South Sudan77.

Many studies have used the CCAFS-Climate portal data to project the impacts of climate change on agricultural production. Several examples are included in working papers for crop production78, and for livestock production79, both focused on sub-Saharan Africa. In Timor Leste, government response to the 2016 El Niño included committing US$12 million to buy reserve food stocks, partly as a result of the use of CCAFS-Climate data77. Other study80 assessed the impact of global warming on outdoor ice-skating in Canada, and showed that its availability and benefits are projected to continue declining at an accelerated rate, posing a real challenge to this popular cultural ecosystem service.

CMIP5 DC data has also contributed as a main input of agriculture sector-specific studies performed in Africa. It includes an analysis of the impacts of climate change on cocoa in Ghana and Cote d’Ivoire81, the climate change impacts and potential benefits of drought and heat tolerance in chickpea in East Africa82, simulate impacts of climate change on water use and yield of irrigated sugarcane in South Africa83, potential benefits of drought and heat tolerance in groundnut for adaptation to climate change in West Africa84, analysis and mapping of climate change risk and vulnerability in Central Rift Valley of Ethiopia85, study of matching seeds to needs-female farmers adapt to a changing climate in Ethiopia86, among others.

A recent outcome assessment based on Outcome Harvesting87 shows that the data in the CCAFS-Climate portal are not only widely used in research activities but are also effective in contributing to development outcomes. The climate data are influencing, directly or indirectly, a range of societal actors, including funders investing in further research, NGOs and government agencies changing their programming and planning for climate change adaptation, and farmers and communities adopting new agricultural practices. The CCAFS-Climate portal is providing scientific, robust and credible climate information, but there are also secondary functions that are contributing to the achievement of outcomes, such as supporting visualization and communication about future climates, enhancing reflective and independent thinking, and engaging partners and stakeholders in collaborative activities77.

Acknowledgements

This work was implemented as part of the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS), which is carried out with support from CGIAR Trust Fund Donors and through bilateral funding agreements. For details, please visit www.ccafs.cgiar.org/donors. The views expressed in this paper cannot be taken to reflect the official opinions of these organizations. We acknowledge the World Climate Research Programme’s Working Group on Coupled Modelling, which is responsible for CMIP, and we thank the climate modeling groups (listed in Table 1) for producing and making available their model output. For CMIP, the U.S. Department of Energy’s Program for Climate Model Diagnosis and Inter-comparison provides coordinating support and led the development of software infrastructure in partnership with the Global Organization for Earth System Science Portals. We gratefully acknowledge to Osana Bonilla-Findji, David Abreu, Héctor Tobón and all the Flagship 2 (Climate Smart Agricultural Practices) CCAFS team, who helped to the development of the CCAFS-Climate portal since its inception. We thank Kornelia Rassmann and Tonya Schuetz who performed an evaluation of the contribution of the portal to development outcomes and environmental impact research studies. We thank to Dr. Frank Toussaint for his help to host the data at WDCC and thank the WDCC for hosting our dataset. Finally, we thank Myles J. Fisher, emeritus scientist from CIAT, for his help with the editing of this manuscript.

Author contributions

C.N.-R. drafted the manuscript, produced the datasets and performed their technical validation. J.T.-M. produced the datasets and performed their technical validation. P.T. drafted the manuscript. A.J. conceived the study and aided with methodological design. J.R.-V. conceived the study, drafted the manuscript, edited the manuscript and aided with methodological design. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Code availability

The DC code used to produce the global database of future climates is publicly available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). We carried out the procedure mainly in ArcInfo Workstation 10, and the R language for statistical computing88. The source code consists of two Arc Macro Language (AML)89 (version 10.0) and two R (version 3.2.4) programming language scripts90.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Gleckler PJ, Taylor KE, Doutriaux C. Performance metrics for climate models. J. Geophys. Res. 2008;113:D06104. doi: 10.1029/2007JD008972. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olesen J, et al. Uncertainties in projected impacts of climate change on European agriculture and terrestrial ecosystems based on scenarios from regional climate models. Clim. Change. 2007;81:123–143. doi: 10.1007/s10584-006-9216-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Challinor AJ, et al. Improving the use of crop models for risk assessment and climate change adaptation. Agric. Syst. 2018;159:296–306. doi: 10.1016/j.agsy.2017.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baron C, et al. From GCM grid cell to agricultural plot: scale issues affecting modelling of climate impact. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2005;360:2095–2108. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2005.1741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Challinor AJ, et al. Methods and resources for climate impacts research. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2009;90:836–848. doi: 10.1175/2008BAMS2403.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adam M, Van Bussel LGJ, Leffelaar PA, Van Keulen H, Ewert F. Effects of modelling detail on simulated potential crop yields under a wide range of climatic conditions. Ecol. Modell. 2011;222:131–143. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2010.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoogenboom, G. et al. Crop Models. Decision Support System for Agrotechnology Transfer, Version 3.0 (DSSAT V3.0), vol. 2–2. International Benchmark Sites Network for Agrotechnology Transfer (IBSNAT) Project. (University of Hawaii, Department of Agronomy and Soil Science, 1994).

- 8.Buytaert W, et al. Uncertainties in climate change projections and regional downscaling: implications for water resources management. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss. 2010;7:1821–1848. doi: 10.5194/hessd-7-1821-2010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hewitson BC, Crane RG. Consensus between GCM climate change projections with empirical downscaling: precipitation downscaling over South Africa. Int. J. Climatol. 2006;26:1315–1337. doi: 10.1002/joc.1314. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacob D, et al. An inter-comparison of regional climate models for Europe: model performance in present-day climate. Clim. Change. 2007;81:31–52. doi: 10.1007/s10584-006-9213-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hijmans RJ, Cameron SE, Parra JL, Jones PG, Jarvis A. Very high resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 2005;25:1965–1978. doi: 10.1002/joc.1276. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilby RL, et al. A review of climate risk information for adaptation and development planning. Int. J. Climatol. 2009;29:1193–1215. doi: 10.1002/joc.1839. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baigorria GA, Jones JW, O’Brien JJ. Potential predictability of crop yield using an ensemble climate forecast by a regional circulation model. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2008;148:1353–1361. doi: 10.1016/j.agrformet.2008.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Challinor AJ, Wheeler TR, Craufurd PQ, Slingo JM. Simulation of the impact of high temperature stress on annual crop yields. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2005;135:180–189. doi: 10.1016/j.agrformet.2005.11.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hawkins E, Osborne TM, Ho CK, Challinor AJ. Calibration and bias correction of climate projections for crop modelling: an idealised case study over. Europe. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2013;170:19–31. doi: 10.1016/j.agrformet.2012.04.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quintana Seguí P, Ribes A, Martin E, Habets F, Boé J. Comparison of three downscaling methods in simulating the impact of climate change on the hydrology of Mediterranean basins. J. Hydrol. 2010;383:111–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2009.09.050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang X.-C. Spatial downscaling of global climate model output for site-specific assessment of crop production and soil erosion. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology. 2005;135(1-4):215–229. doi: 10.1016/j.agrformet.2005.11.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones PG, Thornton P. Generating downscaled weather data from a suite of climate models for agricultural modelling applications. Agric. Syst. 2013;114:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.agsy.2012.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tabor K, Williams JW. Globally downscaled climate projections for assessing the conservation impacts of climate change. Ecol. Appl. 2010;20:554–565. doi: 10.1890/09-0173.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jarvis A, Lane A, Hijmans RJ. The effect of climate change on crop wild relatives. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2008;126:13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2008.01.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Musau, J., Sang, J. & Gathenya, J. General Circulation Models (GCMs) Downscaling Techniques and Uncertainty Modeling for Climate Change Impact Assessment. Proceedings of Sustainable Research and Innovation Conference, [S.l.], p. 147–153, ISSN 2079-6226 (2014).

- 22.Rummukainen M. State-of-the-art with regional climate models. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Chang. 2010;1:82–96. doi: 10.1002/wcc.8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramirez-Villegas J, Challinor A. Assessing relevant climate data for agricultural applications. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2012;161:26–45. doi: 10.1016/j.agrformet.2012.03.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.White JW, Hoogenboom G, Kimball BA, Wall GW. Methodologies for simulating impacts of climate change on crop production. F. Crop. Res. 2011;124:357–368. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2011.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ehret U, Zehe E, Wulfmeyer V, Warrach-Sagi K, Liebert J. Should we apply bias correction to global and regional climate model data? Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss. 2012;9:5355–5387. doi: 10.5194/hessd-9-5355-2012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maurer EP, Hidalgo HG. Utility of daily vs. monthly large-scale climate data: an intercomparison of two statistical downscaling methods. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2008;12:551–563. doi: 10.5194/hess-12-551-2008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones, R. et al. Generating high resolution climate change scenarios using PRECIS. (Met Office Hadley Centre, 2004).

- 28.Xu Z, Yang Z-L. A new dynamical downscaling approach with GCM bias corrections and spectral nudging. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2015;120:2014JD022958. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garcia-Carreras L, et al. The Impact of Parameterized Convection on the Simulation of Crop Processes. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2015;54:1283–1296. doi: 10.1175/JAMC-D-14-0226.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilby RL, Wigley TML. Downscaling general circulation model output: a review of methods and limitations. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 1997;21:530–548. doi: 10.1177/030913339702100403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Giorgi F, Jones C, Asrar GR. Addressing climate information needs at the regional level: the CORDEX framework. World Meteorol. Organ. Bull. 2009;58:175–183. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kendon EJ, Jones RG, Kjellström E, Murphy JM. Using and Designing GCM–RCM Ensemble Regional Climate Projections. J. Clim. 2010;23:6485–6503. doi: 10.1175/2010JCLI3502.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sørland SL, Schär C, Lüthi D, Kjellström E. Bias patterns and climate change signals in GCM-RCM model chains. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018;13:074017. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/aacc77. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maraun D. Bias Correction, Quantile Mapping, and Downscaling: Revisiting the Inflation Issue. J. Clim. 2013;26:2137–2143. doi: 10.1175/JCLI-D-12-00821.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gebrechorkos SH, Hülsmann S, Bernhofer C. Statistically downscaled climate dataset for East Africa. Sci. Data. 2019;6:31. doi: 10.1038/s41597-019-0038-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilby, R., Charles, S., Zorita, E. & Timbal, B. Guidelines for use of climate scenarios developed from statistical downscaling methods. Supporting material of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, available from the DDC of IPCC TGCIA 27 (2004).

- 37.Themeßl JM, Gobiet A, Leuprecht A. Empirical-statistical downscaling and error correction of daily precipitation from regional climate models. Int. J. Climatol. 2011;31:1530–1544. doi: 10.1002/joc.2168. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ines AVM, Hansen JW, Robertson AW. Enhancing the utility of daily GCM rainfall for crop yield prediction. Int. J. Climatol. 2011;31:2168–2182. doi: 10.1002/joc.2223. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taylor KE, Stouffer RJ, Meehl GA. An Overview of CMIP5 and the Experiment Design. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2012;93:485–498. doi: 10.1175/BAMS-D-11-00094.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moss RH, et al. The next generation of scenarios for climate change research and assessment. Nature. 2010;463:747–756. doi: 10.1038/nature08823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Navarro-Racines CE, Tarapues-Montenegro JE, Thornton P, Jarvis A, Ramirez-Villegas J. 2019. CCAFS-CMIP5 Delta Method Downscaling for monthly averages and bioclimatic indices of four RCPs. World Data Center for Climate (WDCC) at DKR. [DOI]

- 42.Ho CK, Stephenson DB, Collins M, Ferro CAT, Brown SJ. Calibration strategies; a source of additional uncertainty in climate change projections. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2012;93:21–26. doi: 10.1175/2011BAMS3110.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hay LE, Wilby RL, Leavesley GH. A comparison of delta change and downscaled GCM scenarios for three mountainous basins in the United States. JAWRA J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2000;36:387–397. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-1688.2000.tb04276.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rippke U, et al. Timescales of transformational climate change adaptation in sub-Saharan African agriculture. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2016;6:605–609. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2947. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Warren R, et al. Quantifying the benefit of early climate change mitigation in avoiding biodiversity loss. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2013;3:678–682. doi: 10.1038/nclimate1887. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hutchinson MF. Interpolating mean rainfall using thin plate smoothing splines. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Syst. 1995;9:385–403. doi: 10.1080/02693799508902045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harris I, Jones PD, Osborn TJ, Lister DH. Updated high-resolution grids of monthly climatic observations – the CRU TS3.10 Dataset. Int. J. Climatol. 2014;34:623–642. doi: 10.1002/joc.3711. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Deblauwe V, et al. Remotely sensed temperature and precipitation data improve species distribution modelling in the tropics. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2016;25:443–454. doi: 10.1111/geb.12426. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Funk C, et al. The climate hazards infrared precipitation with stations—a new environmental record for monitoring extremes. Sci. Data. 2015;2:150066. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2015.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.IPCC. Climate Change 2013 The Physical Science Basis Working Group I Contribution to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Stocker, T. F. et al.] Cambridge Univ. Press United Kingdom New York, NY, USA 1535 pp (2013).

- 51.Franke R. Smooth interpolation of scattered data by local thin plate splines. Comput. Math. with Appl. 1982;8:273–281. doi: 10.1016/0898-1221(82)90009-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mitáš L, Mitášová H. General variational approach to the interpolation problem. Comput. Math. with Appl. 1988;16:983–992. doi: 10.1016/0898-1221(88)90255-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hutchinson, M. F. A summary of some surface fitting and contouring programs for noisy data. (1984).

- 54.Hutchinson MF, de Hoog FR. Smoothing noisy data with spline functions. Numer. Math. 1985;47:99–106. doi: 10.1007/BF01389878. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nix, H. A. A biogeographic analysis of Australian elapid snakes. Atlas of Elapid Snakes of Australia (Australian Government Publishing Service: Canberra, 1986).

- 56.Busby JR. BIOCLIM—a bioclimate analysis and prediction system. Plant Prot. Q. 1991;6:8–9. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Khoury CK, et al. Comprehensiveness of conservation of useful wild plants: An operational indicator for biodiversity and sustainable development targets. Ecol. Indic. 2019;98:420–429. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2018.11.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Castro-Llanos F., Hyman G., Rubiano J., Ramirez-Villegas J., Achicanoy H. Climate change favors rice production at higher elevations in Colombia. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change. 2019;24(8):1401–1430. doi: 10.1007/s11027-019-09852-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Navarro-Racines C, Tarapues-Montenegro J, Guevara E, Jarvis A, Ramírez-Villegas J. 2019. CCAFS-CMIP5 Delta Method Downscaling database. figshare. [DOI]

- 60.Nelson, G. C. et al. Food Security, Farming and Climate Change to 2050: Scenarios, Results and Policy Options. (International Food Policy Research Institute, 2010).

- 61.Grafton RQ, Daugbjerg C, Qureshi ME. Towards food security by 2050. Food Secur. 2015;7:179–183. doi: 10.1007/s12571-015-0445-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rogelj J, et al. Paris Agreement climate proposals need a boost to keep warming well below 2 °C. Nature. 2016;534:631–639. doi: 10.1038/nature18307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schleussner C-F, et al. Differential climate impacts for policy-relevant limits to global warming: the case of 1.5 °C and 2 °C. Earth Syst. Dyn. 2016;7:327–351. doi: 10.5194/esd-7-327-2016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.DeFlorio MJ, Pierce DW, Cayan DR, Miller AJ. Western U.S. Extreme Precipitation Events and Their Relation to ENSO and PDO in CCSM4. J. Clim. 2013;26:4231–4243. doi: 10.1175/JCLI-D-12-00257.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang Y, Zhang GJ, Craig GC. Stochastic convective parameterization improving the simulation of tropical precipitation variability in the NCAR CAM5. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2016;43:6612–6619. doi: 10.1002/2016GL069818. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hawkins E, et al. Increasing influence of heat stress on French maize yields from the 1960s to the 2030s. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2013;19:937–947. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Läderach P, et al. Climate change adaptation of coffee production in space and time. Clim. Change. 2017;141:47–62. doi: 10.1007/s10584-016-1788-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Katz RW, Brown BG. Extreme events in a changing climate: Variability is more important than averages. Clim. Change. 1992;21:289–302. doi: 10.1007/BF00139728. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Field Christopher B., Barros Vicente, Stocker Thomas F., Dahe Qin., editors. Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sillmann J, Kharin VV, Zhang X, Zwiers FW, Bronaugh D. Climate extremes indices in the CMIP5 multimodel ensemble: Part 1. Model evaluation in the present climate. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2013;118:1716–1733. doi: 10.1002/jgrd.50203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ramirez-Villegas J, Challinor AJ, Thornton PK, Jarvis A. Implications of regional improvement in global climate models for agricultural impact research. Environ. Res. Lett. 2013;8:24018. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/8/2/024018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Koehler A-K, Challinor AJ, Hawkins E, Asseng S. Influences of increasing temperature on Indian wheat: quantifying limits to predictability. Environ. Res. Lett. 2013;8:34016. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/8/3/034016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Guo D, Arnolds JL, Midgley GF, Foden WB. Conservation of Quiver Trees in Namibia and South Africa under a Changing Climate. J. Geosci. Environ. Prot. 2016;04:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jennings MD, Harris GM. Climate change and ecosystem composition across large landscapes. Landsc. Ecol. 2017;32:195–207. doi: 10.1007/s10980-016-0435-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Messina, J. P. et al. Mapping global environmental suitability for Zika virus. Elife5 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 76.Jarvis, A. et al. Farms of the future: An innovative approach for strengthening adaptive capacity. In International Conference on Agricultural Innovation Systems in Africa (ASIA), 10.13140/2.1.1269.9208 (2013).

- 77.Rassmann, K. & Schuetz, T. An assessment of the influence of CCAFS’ climate data and tools on outcomes achieved 2010–2016. CCAFS outcomes evaluation report1 (2017).

- 78.Ramirez-Villegas, J. & Thornton, P. K. Climate change impacts on African crop production. CCAFS Working Paper (2015).

- 79.Thornton, P. K., Boone, R. B. & Ramirez-Villegas, J. Climate Change Impacts on Livestock. (2015).

- 80.Brammer JR, Samson J, Humphries MM. Declining availability of outdoor skating in Canada. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2015;5:2–4. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2465. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Schroth G, Läderach P, Martinez-Valle AI, Bunn C, Jassogne L. Vulnerability to climate change of cocoa in West Africa: Patterns, opportunities and limits to adaptation. Sci. Total Environ. 2016;556:231–241. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Singh P, et al. Climate change impacts and potential benefits of drought and heat tolerance in chickpea in South Asia and East Africa. Eur. J. Agron. 2014;52:123–137. doi: 10.1016/j.eja.2013.09.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jones MR, Singels A, Ruane AC. Simulated impacts of climate change on water use and yield of irrigated sugarcane in South Africa. Agric. Syst. 2015;139:260–270. doi: 10.1016/j.agsy.2015.07.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Singh P, et al. Potential benefits of drought and heat tolerance in groundnut for adaptation to climate change in India and West. Africa. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Chang. 2014;19:509–529. doi: 10.1007/s11027-012-9446-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gizachew L, Shimelis A. Analysis and mapping of climate change risk and vulnerability in Central Rift Valley of Ethiopia. African Crop Sci. J. 2014;22:807–818. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gotor, E., Fadda, C. & Trincia, C. Matching Seeds to Needs-female farmers adapt to a changing climate in Ethiopia. (2014).

- 87.Wilson-Grau, R. & Britt, H. Outcome harvesting. 2012 (2013).

- 88.R Core Team R: A language and environment for statistical computing (2018).

- 89.ESRI. ArcGIS ArcInfo: Release 10 (2011).

- 90.Navarro-Racines C, 2018. Delta method downscaling programming language scripts. figshare. [DOI]

- 91.Wu T. A mass-flux cumulus parameterization scheme for large-scale models: description and test with observations. Clim. Dyn. 2012;38:725–744. doi: 10.1007/s00382-011-0995-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Xin X, Wu T, Li JF, Wang Z, Li W. How Well does BCC_CSM1.1 Reproduce the 20th Century Climate Change over China? Atmos. Ocean. Sci. Lett. 2012;6:21–26. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Xin X, Zhang L, Zhang J, Wu T, Fang Y. Climate Change Projections over East Asia with BCC_CSM1.1 Climate Model under RCP Scenarios. J. Meteorol. Soc. Japan. Ser. II. 2013;91:413–429. doi: 10.2151/jmsj.2013-401. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ji D, et al. Description and basic evaluation of Beijing Normal University Earth System Model (BNU-ESM) version 1. Geosci. Model Dev. 2014;7:2039–2064. doi: 10.5194/gmd-7-2039-2014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Arora VK, et al. Carbon emission limits required to satisfy future representative concentration pathways of greenhouse gases. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2011;38:L05805. doi: 10.1029/2010GL046270. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 96.von Salzen K, et al. The Canadian Fourth Generation Atmospheric Global Climate Model (CanAM4). Part I: Representation of Physical Processes. Atmosphere-Ocean. 2013;51:104–125. doi: 10.1080/07055900.2012.755610. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hurrell JW, et al. The Community Earth System Model: A Framework for Collaborative. Research. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2013;94:1339–1360. doi: 10.1175/BAMS-D-12-00121.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Long MC, Lindsay K, Peacock S, Moore JK, Doney SC. Twentieth-Century Oceanic Carbon Uptake and Storage in CESM1(BGC)*. J. Clim. 2013;26:6775–6800. doi: 10.1175/JCLI-D-12-00184.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Voldoire A, et al. The CNRM-CM5.1 global climate model: description and basic evaluation. Clim. Dyn. 2013;40:2091–2121. doi: 10.1007/s00382-011-1259-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bi D, et al. The ACCESS coupled model: description, control climate and evaluation. Aust. Meteorol. Oceanogr. J. 2013;63:41–64. doi: 10.22499/2.6301.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Dix M, et al. The ACCESS coupled model: documentation of core CMIP5 simulations and initial results. Aust. Meteorol. Oceanogr. J. 2013;63:83–99. doi: 10.22499/2.6301.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Rotstayn LD, et al. Aerosol- and greenhouse gas-induced changes in summer rainfall and circulation in the Australasian region: a study using single-forcing climate simulations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2012;12:6377–6404. doi: 10.5194/acp-12-6377-2012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hazeleger W, et al. EC-Earth V2.2: description and validation of a new seamless earth system prediction model. Clim. Dyn. 2012;39:2611–2629. doi: 10.1007/s00382-011-1228-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Qiao F, et al. Development and evaluation of an Earth System Model with surface gravity waves. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2013;118:4514–4524. doi: 10.1002/jgrc.20327. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Delworth TL, et al. GFDL’s CM2 Global Coupled Climate Models. Part I: Formulation and Simulation Characteristics. J. Clim. 2006;19:643–674. doi: 10.1175/JCLI3629.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Donner LJ, et al. The Dynamical Core, Physical Parameterizations, and Basic Simulation Characteristics of the Atmospheric Component AM3 of the GFDL Global Coupled Model CM3. J. Clim. 2011;24:3484–3519. doi: 10.1175/2011JCLI3955.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Dunne JP, et al. GFDL’s ESM2 Global Coupled Climate–Carbon Earth System Models. Part II: Carbon System Formulation and Baseline Simulation Characteristics*. J. Clim. 2013;26:2247–2267. doi: 10.1175/JCLI-D-12-00150.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Schmidt GA, et al. Present-Day Atmospheric Simulations Using GISS ModelE: Comparison to In Situ, Satellite, and Reanalysis Data. J. Clim. 2006;19:153–192. doi: 10.1175/JCLI3612.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Schmidt GA, et al. Configuration and assessment of the GISS ModelE2 contributions to the CMIP5 archive. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 2014;6:141–184. doi: 10.1002/2013MS000265. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Volodin EM, Dianskii NA, Gusev AV. Simulating present-day climate with the INMCM4.0 coupled model of the atmospheric and oceanic general circulations. Izv. Atmos. Ocean. Phys. 2010;46:414–431. doi: 10.1134/S000143381004002X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Dufresne J-L, et al. Climate change projections using the IPSL-CM5 Earth System Model: from CMIP3 to CMIP5. Clim. Dyn. 2013;40:2123–2165. doi: 10.1007/s00382-012-1636-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Li L, et al. The flexible global ocean-atmosphere-land system model, Grid-point Version 2: FGOALS-g2. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2013;30:543–560. doi: 10.1007/s00376-012-2140-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Watanabe S, et al. MIROC-ESM 2010: model description and basic results of CMIP5-20c3m experiments. Geosci. Model Dev. 2011;4:845–872. doi: 10.5194/gmd-4-845-2011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Watanabe M, et al. Improved Climate Simulation by MIROC5: Mean States, Variability, and Climate Sensitivity. J. Clim. 2010;23:6312–6335. doi: 10.1175/2010JCLI3679.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Collins WJ, et al. Development and evaluation of an Earth-System model – HadGEM2. Geosci. Model Dev. 2011;4:1051–1075. doi: 10.5194/gmd-4-1051-2011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Martin G, et al. The HadGEM2 family of Met Office Unified Model climate configurations. Geosci. Model Dev. 2011;4:723–757. doi: 10.5194/gmd-4-723-2011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Reick CH, Raddatz T, Brovkin V, Gayler V. Representation of natural and anthropogenic land cover change in MPI-ESM. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 2013;5:459–482. doi: 10.1002/jame.20022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Yukimoto, S. et al. Meteorological Research Institute-Earth System Model v1 (MRI-ESM1)—Model Description (2011).

- 119.Yukimoto S, et al. A New Global Climate Model of the Meteorological Research Institute: MRI-CGCM3: Model Description and Basic Performance. J. Meteorol. Soc. Japan. Ser. II. 2012;90A:23–64. doi: 10.2151/jmsj.2012-A02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Gent PR, et al. The Community Climate System Model Version 4. J. Clim. 2011;24:4973–4991. doi: 10.1175/2011JCLI4083.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Iversen T, et al. The Norwegian Earth System Model, NorESM1-M – Part 2: Climate response and scenario projections. Geosci. Model Dev. 2013;6:389–415. doi: 10.5194/gmd-6-389-2013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 122.United Nations Statistics Division. Standard Country or Area Codes for Statistical Use (Rev. 3), Series M: Miscellaneous Statistical Papers, No. 49 (1996).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Navarro-Racines CE, Tarapues-Montenegro JE, Thornton P, Jarvis A, Ramirez-Villegas J. 2019. CCAFS-CMIP5 Delta Method Downscaling for monthly averages and bioclimatic indices of four RCPs. World Data Center for Climate (WDCC) at DKR. [DOI]

- Navarro-Racines C, Tarapues-Montenegro J, Guevara E, Jarvis A, Ramírez-Villegas J. 2019. CCAFS-CMIP5 Delta Method Downscaling database. figshare. [DOI]

- Navarro-Racines C, 2018. Delta method downscaling programming language scripts. figshare. [DOI]

Data Availability Statement

The DC code used to produce the global database of future climates is publicly available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). We carried out the procedure mainly in ArcInfo Workstation 10, and the R language for statistical computing88. The source code consists of two Arc Macro Language (AML)89 (version 10.0) and two R (version 3.2.4) programming language scripts90.