Abstract

Campylobacter jejuni is one of the most common zoonotic pathogens worldwide. Although the main sources of human C. jejuni infection are livestock, wildlife can also affect C. jejuni transmission in humans. However, it remains unclear whether wild mice harbor C. jejuni and are involved in the “environment–wildlife–livestock–human” transmission cycle of C. jejuni in humans. Here, we characterized C. jejuni from wild mice and identified genetic traces of wild mouse-derived C. jejuni in other hosts using a traditional approach, along with comparative genomics. We captured 115 wild mice (49 Mus musculus and 66 Micromys minutus) without any clinical symptoms from 22 sesame fields in Korea over 2 years. Among them, M. minutus were typically caught in remote areas of human houses and C. jejuni was solely isolated from M. minutus (42/66, 63.6%). We identified a single clone (MLST ST-8388) in all 42 C. jejuni isolates, which had not been previously reported, and all isolates had the same virulence/survival-factor profile, except for the plasmid-mediated virB11 gene. No isolates exhibited antibiotic resistance, either in phenotypic and genetic terms. Comparative-genomic analysis and MST revealed that C. jejuni derived from M. minutus (strain SCJK2) was not genetically related to those derived from other sources (registered in the NCBI genome database and PubMLST database). Therefore, we hypothesize that C. jejuni from M. minutus is a normal component of the gut flora following adaptation to the gastro-intestinal tract. Furthermore, M. minutus-derived C. jejuni had different ancestral lineages from those derived from other sources, and there was a low chance of C. jejuni transmission from M. minutus to humans/livestock because of their habitat. In conclusion, M. minutus may be a potential reservoir for a novel C. jejuni, which is genetically different from those of other sources, but may not be involved in the transmission of C. jejuni to other hosts, including humans and livestock. This study could form the basis for further studies focused on understanding the transmission cycle of C. jejuni, as well as other zoonotic pathogens originating from wild mice.

Keywords: Campylobacter jejuni, wild mouse, transmission cycle, whole genome sequencing, comparative genomic analysis

Introduction

Campylobacter jejuni is one of the most common zoonotic pathogens worldwide, and human infections with this pathogen have increased in both developing and developed countries (Kaakoush et al., 2015). In particular, C. jejuni directly causes gastrointestinal diseases such as diarrhea and abdominal pain, and it can also lead to late complications such as neurological diseases, including Guillain–Barre and Miller–Fisher syndromes in humans (Nachamkin et al., 1998). The main sources of C. jejuni transmission in humans are livestock, including poultry and cattle, and humans in particular are easily exposed to C. jejuni during the handling or ingestion of poultry (Bronowski et al., 2014). Environmental sources are also reservoirs for C. jejuni infections in humans, and transmission through contaminated water and soil is prevalent (Gras et al., 2012). In addition, wildlife species can serve as potential reservoirs for C. jejuni infection in humans (Waldenström et al., 2007). Therefore, humans, livestock, environmental sources, and wildlife form complex interactions that contribute to C. jejuni infection and constitute a transmission cycle. Studies of C. jejuni in various reservoirs are needed to better understand the potential for C. jejuni transmission and the impact that such transmission could have on human health.

Studies on C. jejuni in wildlife have been conducted mainly with wild birds, since they can contribute to C. jejuni infections in humans and livestock (French et al., 2009; Weis et al., 2016). In addition to research on wild birds, C. jejuni infections in wild mice are also important to study, since wild mice are prevalent, come in close contact with humans, and are known carriers of various pathogens (Kruse et al., 2004; Han et al., 2015). However, few studies have examined C. jejuni infection in wild mice, and no studies evaluating the effects of wild mice on human C. jejuni infection have been reported. Only one study provided an estimate of C. jejuni-transmission events between rodents and pigs on the same farm (Meerburg et al., 2006). Thus, the possibility of wild mice being a reservoir of C. jejuni and playing a role in the transmission of C. jejuni between wild mice and other hosts remains unclear, and no studies have shown that wild mice (similarly to wild birds) contribute to human C. jejuni infection (Meerburg and Kijlstra, 2007).

The objectives of this study were to determine whether wild mice harbor C. jejuni in their normal gut and whether they are involved in the “environment–wildlife–livestock–human” transmission cycle of C. jejuni in human infections. To characterize C. jejuni from wild mice, C. jejuni was isolated from wild mice (Mus musculus and Micromys minutus) in 22 sesame fields over the course of 2 years. The clonal distribution of C. jejuni isolates from these wild mice was identified, and the virulence/survival-factor profiles and antibiotic-resistance patterns of all isolates were determined. Furthermore, to investigate a genetic trace of C. jejuni transmission between wild mice and other hosts, the genetic relatedness of C. jejuni between wild mice and other sources was compared using comparative-genomic analysis.

Materials and Methods

Sampling of Wild Mice and Isolation of C. jejuni

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Hallym University (approval number Hallym2017-5). Wild mice, including M. musculus and M. minutus, were captured under piles of dry sesame plants in 22 sesame fields that were separated by rivers, roads, and mountains in Hongcheon and Chuncheon (Gangwon Province, South Korea) over the course of 2 years. The global positioning system (GPS) coordinates for the regions where the sesame fields were located are shown in Figure 1. All captured wild mice were immediately transported to the laboratory, and each wild mouse was transferred to a single disinfected cage. Fresh fecal samples were collected within 10 min and stored at 4°C. Subsequently, pathological signs or lesions and total length and body weight were investigated for each wild mouse. In M. musculus, the mean total lengths were 12.41 ± 0.43 (males) and 12.63 ± 0.56 cm (females), respectively, and the mean body weights were 9.61 ± 1.16 (males) and 9.93 ± 1.23 g (females), respectively. In M. minutus, the mean total lengths were 12.71 ± 0.2 (males) and 11.72 ± 0.95 cm (females), respectively, and the mean body weights were 7.44 ± 1.41 (males) and 8.38 ± 1.76 g (females), respectively.

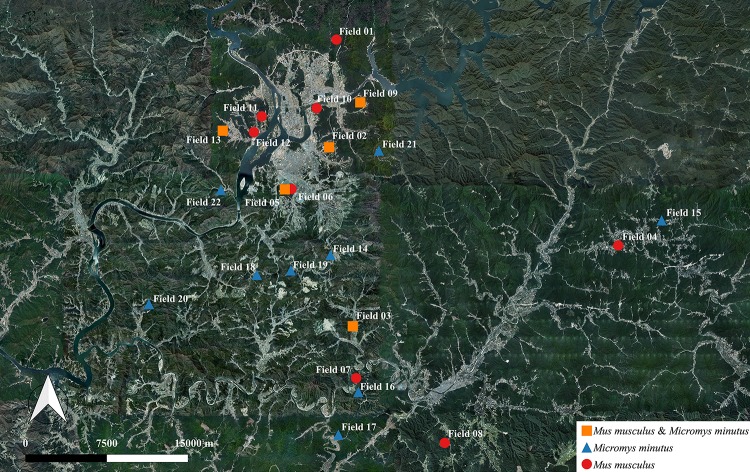

FIGURE 1.

Information regarding the habitat of wild mice, Mus musculus and Micromys minutus. We captured 115 wild mice, including 49 M. musculus and 66 M. minutus, in 22 sesame fields that were separated by rivers, roads, and mountains. M. musculus were caught in 13 fields near the vicinity of human houses, whereas M. minutus were caught in 14 fields distant from human houses. Both species of wild mice shared a habitat in only 5 of 22 fields. Maps based on GPS coordinates were created using Quantum Geographical Information System, version 3.4.4 (http://qgis.org).

Within 3 h after fecal sampling, we began isolating C. jejuni from the feces of the wild mice. Fecal samples collected from each wild mouse were homogenized in phosphate-buffered saline. The homogenized contents were directly spread onto modified charcoal–cefoperazone–deoxycholate agar plate (mCCDA; Oxoid, Ltd., Hampshire, United Kingdom) with a CCDA-selective supplement (Oxoid, Ltd., Hampshire, United Kingdom). Next, all plates were incubated at 42°C for 2 days under 83% N2, 7% CO2, 4% H2, and 6% O2 (Mace et al., 2015) in micro-aerobic jars using Anoxomat Mark II (MART Microbiology B.V., Lichtenvoorde, Netherlands). Next, colonies suspected to be C. jejuni were transferred to Müller–Hinton agar (Oxoid, Ltd., Hampshire, United Kingdom), and genomic DNA was extracted from each colony using the boiling method. Briefly, bacterial cells were suspended in 200 μL sterile distilled water, boiled for 10 min, and centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 3 min. The resulting supernatants were used as a template for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) experiments. C. jejuni was confirmed by running PCR experiments (Table 1; Wang et al., 2002). Then, to identify false negatives for C. jejuni, an isolation method with an enrichment process was applied. Briefly, the fecal samples that were negative for C. jejuni were enriched in Bolton broth (Oxoid, Ltd., Hampshire, United Kingdom) with a Bolton broth-selective supplement (Oxoid, Ltd., Hampshire, United Kingdom), and the enrichment broths were incubated at 42°C for 48 h under 83% N2, 7% CO2, 4% H2, and 6% O2 in micro-aerobic jars using Anoxomat Mark II (MART Microbiology B.V., Lichtenvoorde, Netherlands). Subsequently, the presence of C. jejuni in these samples was confirmed following the same procedure described above. Finally, the chi-square test was performed to compare the isolation rates of C. jejuni by the gender/age of the mice and the region/year in which mice were captured.

TABLE 1.

Primes used for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in this study.

| Target microbe | Target | Size (bp) | Primer | Sequence (5′-3′) | References | |

| PCR for confirmation of | C. jejuni | hipO | 323 | F | ACTTCTTTATTGCTTGCTGC | Wang et al., 2002 |

| C. jejuni colonies | R | GCCACAACAAGTAAAGAAGC | ||||

| Campylobacter spp. | 23S rRNA | 650 | F | TATACCGGTAAGGAGTGCTGGAG | Wang et al., 2002 | |

| R | ATCAATTAACCTTCGAGCACCG | |||||

| PCR for identification of | C. jejuni | flhB | 549 | F | TGGCAGGCGAAGATCAAGAA | Koolman et al., 2015 |

| virulence and survival-related | R | GCCAAGTAAGCTGTGCAACC | ||||

| genes of C. jejuni isolates | virB11 | 329 | F | TCAGGTGGAACAGGAAGTGG | Koolman et al., 2015 | |

| R | GCTTTGATCGCGTCTTCTGG | |||||

| hcp | 463 | F | CAAGCGGTGCATCTACTGAA | Harrison et al., 2014 | ||

| R | TAAGCTTTGCCCTCTCTCCA | |||||

| cadF | 400 | F | TTGAAGGTAATTTAGATATG | Konkel et al., 1999 | ||

| R | CTAATACCTAAAGTTGAAAC | |||||

| pldA | 913 | F | AAGCTTATGCGTTTTT | Datta et al., 2003 | ||

| R | TATAAGGCTTTCTCCA | |||||

| iamA | 518 | F | GCACAAAATATATCATTACAA | Müller et al., 2006 | ||

| R | TTCACGACTACTATGAGG | |||||

| cdtB | 376 | F | GCTCCTACATCAACGCGAGA | Koolman et al., 2015 | ||

| R | ACTACTCCGCCTTTTACCGC | |||||

| crsA | 878 | F | CACAGTCAGTGAAGGTGCTT | González-Hein et al., 2013 | ||

| R | ACTCGCACAATCGCTACTTC | |||||

| perR | 153 | F | CCCTTCAATCTCTTTAGCGACG | An et al., 2018 | ||

| R | ATACCACCACATTTGGCGCA | |||||

| htrA | 130 | F | CCATTGCGATATACCCAAACTT | Bui et al., 2012 | ||

| R | CTGGTTTCCAAGAGGGTGAT | |||||

| PCR for confirmation of | C. jejuni | tetO | 559 | F | GGCGTTTTGTTTATGTGCG | Gibreel et al., 2004 |

| antibiotic resistance of | R | ATGGACAACCCGACAGAAGC | ||||

| C. jejuni isolates | gyrA | F | TTTTTAGCAAAGATTCTGAT | Zirnstein et al., 1999 | ||

| 265 | R1 | CAAAGCATCATAAACTGCAA | ||||

| 368 | R2 | CAGTATAACGCATCGCAG |

Multilocus Sequence Typing of Wild Mouse-Derived C. jejuni

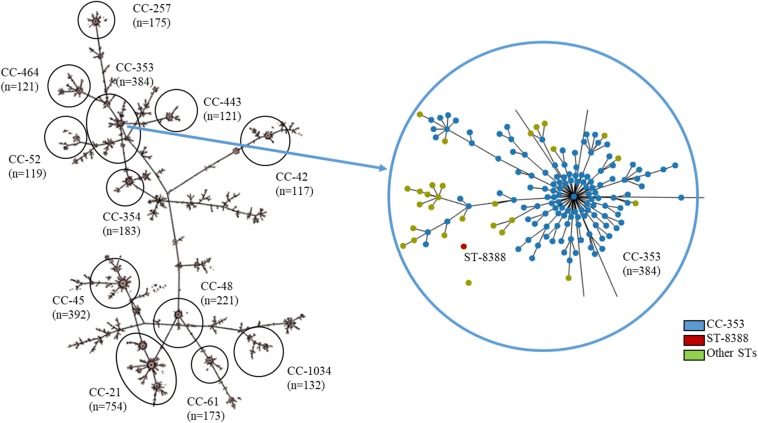

Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) was performed on all C. jejuni isolates from wild mice, according to the PubMLST protocol1. Briefly, seven housekeeping genes (aspartase A, glutamine synthetase, citrate synthase, serine hydroxymethyl transferase, phosphoglucomutase, transketolase, and ATP synthase alpha subunit) were amplified and sequenced with primer sets described in the PubMLST protocol. Amplification and sequencing were performed using Lamp Taq DNA Polymerase (BIOFACT, South Korea) and an ABI 3730XL DNA analyzer (Applied Biosystems, United States), respectively. Furthermore, a minimum-spanning tree based on the allelic MLST profiles of the current study (ST-8388) and other sequence types (STs) registered in PubMLST (accessed on 20 November 2019, about 6,800 STs from C. jejuni, Supplementary Table 1) was generated using the PHYLOViZ software2 (Francisco et al., 2012).

Profiling Virulence/Survival Factors and Antibiotic-Resistance Patterns of Wild Mouse-Derived C. jejuni

For all C. jejuni isolates, the presence and absence of virulence/survival-related genes were confirmed by PCR (Table 1; Konkel et al., 1999; Datta et al., 2003; Müller et al., 2006; Bui et al., 2012; González-Hein et al., 2013; Harrison et al., 2014; Koolman et al., 2015; An et al., 2018). These genes corresponded to three secretion systems (flhB, virB11, and hcp), one adherence/colonization-related protein (cadF), two cell invasion-related proteins (pldA and iamA), one cytotoxin-related protein (cdtB), and three survival-related factors (crsA, perR, and htrA). The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC; for erythromycin, chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin, tetracycline, telithromycin, gentamicin, azithromycin, streptomycin, and nalidixic acid), disk diffusion (for ciprofloxacin, tetracycline, and nalidixic acid), and sequence-based tests (for gyrA and tetO genes) were conducted for all C. jejuni isolates to evaluate antibiotic resistance (Table 1; Zirnstein et al., 1999; Gibreel et al., 2004).

Whole-Genome Sequencing of Representative Wild Mouse-Derived C. jejuni Strains

A representative strain of wild mouse-derived C. jejuni (strain SCJK2) was selected, and genomic DNA was extracted using the MGTM Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Macrogen, South Korea). Whole-genome sequencing was performed using a Pacific Biosciences RS II sequencer (Pacific Biosciences, Menlo Park, CA, United States). De novo microbial genome assemblies were carried out using Hierarchical Genome Assembly Process, version 3.0 (Chin et al., 2013), and all contigs were circularized using Circlator 1.4.0 (Sanger Institute, United Kingdom). The NCBI prokaryotic genome annotation pipeline3 and the EzBioCloud genome database4 were used for gene annotation. Functional classification was performed using the EggNOG (Powell et al., 2014), SwissProt (Pundir et al., 2015), KEGG (Kanehisa et al., 2015), and SEED (Overbeek et al., 2005) databases. Antibiotic resistance- and virulence-related genes of wild mouse-derived C. jejuni (strain SCJK2) sequence were analyzed using the comprehensive antibiotic resistance database (CARD) (Jia et al., 2016) and virulence factors of pathogenic bacteria database (VFDB) (Chen et al., 2015), respectively.

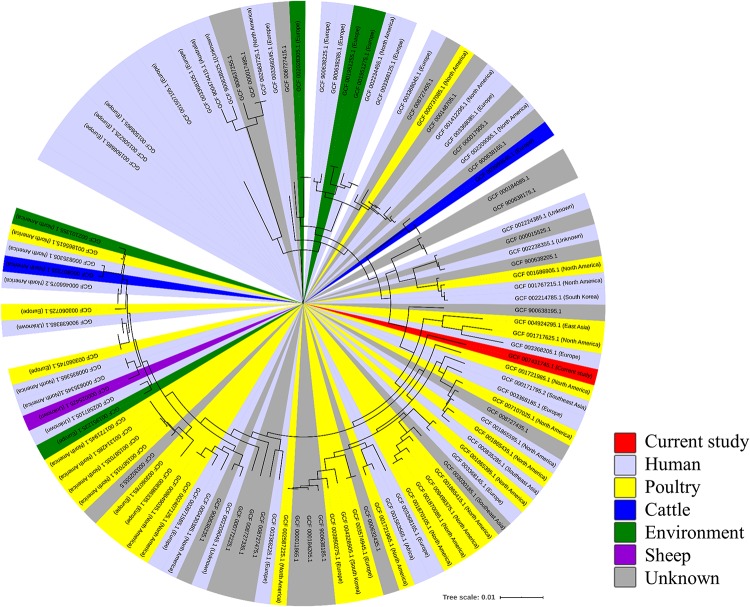

Comparative-Genomic Analysis of Wild Mouse-Derived C. jejuni With Previously Reported Isolates

For comparative genomic analysis, 174 complete genome sequences of C. jejuni from various sources, including humans, poultry, bovines, and sheep, as well as environmental isolates (Supplementary Table 2), were downloaded from the NCBI Genome database5. For phylogenetic characterization of the wild mouse-derived C. jejuni (strain SCJK2) sequence with other sequences obtained from the NCBI Genome database, functional annotation of all 175 genomes was performed using Prokka (Seemann, 2014), and then core genes (genes possessed by >95% genomes) and accessory genes (genes possessed by <95% strains) were identified using Roary (Page et al., 2015). Multiple alignments were performed on core genes and approximately maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree was constructed with generalized time reversible models using PRANK and Fast Tree (Price et al., 2010; Löytynoja, 2014). The phylogenetic tree was generated using the iTOl6.

Results

Habitat of Each Wild Mouse Species

We captured 115 wild mice, including 49 M. musculus (20 male and 29 female) and 66 M. minutus (40 male and 26 female) in 22 sesame fields; M. musculus were captured in 13 out of 22 sesame fields and M. minutus were captured in 14 out of 22 sesame fields (Figure 1 and Table 2). M. musculus were typically caught in the vicinity of human houses, whereas M. minutus were caught in remote areas of human houses, or near mountains or rivers. Both species of wild mice shared a habitat in only 5 of 22 sesame fields (fields 02, 03, 05, 09, and 13). Pathological signs or lesions were not observed in any of the captured wild mice.

TABLE 2.

Prevalence of Campylobacter jejuni and the virB11 gene from C jejuni in the different wild mouse species (Mus musculus and Micromys minutus).

|

Species |

Mus musculus |

Species |

Micromys minutus |

|||

| Field | Number of mouse (female/male) | Number of C. jejuni positive (female/male) | Field | Number of mouse (female/male) | Number of C. jejuni positive (female/male) | Number of virB11 positive isolates |

| 01 | 12 (7/5) | – | 02 | 3 (2/1) | 3 (2/1) | 3 (100%) |

| 02 | 2 (2/0) | – | 03 | 9 (2/7) | 6 (0/6) | 0 (0%) |

| 03 | 8 (7/1) | – | 05 | 1 (1/0) | – | – |

| 04 | 1 (1/0) | – | 09 | 3 (1/2) | 1(0/1) | 0 (0%) |

| 05 | 3 (0/3) | – | 13 | 9 (6/3) | 5 (4/1) | 5 (100%) |

| 06 | 1 (0/1) | – | 14 | 5 (3/2) | 3 (1/2) | 0 (0%) |

| 07 | 3 (1/2) | – | 15 | 10 (2/8) | 5 (0/5) | 0 (0%) |

| 08 | 1 (0/1) | – | 16 | 3 (2/1) | 2 (1/1) | 0 (0%) |

| 09 | 1 (0/1) | – | 17 | 12 (3/9) | 10 (3/7) | 10 (100%) |

| 10 | 7 (5/2) | – | 18 | 1 (0/1) | 1 (0/1) | 0 (0%) |

| 11 | 4 (3/1) | – | 19 | 1 (1/0) | – | – |

| 12 | 3 (1/2) | – | 20 | 3 (2/1) | 3 (2/1) | 0 (0%) |

| 13 | 3 (2/1) | – | 21 | 2 (0/2) | 1 (0/1) | 0 (0%) |

| 22 | 4 (1/3) | 2 (0/2) | 2 (100%) | |||

| Total | 49 (29/20) | 0 (0%) | Total | 66 (26/40) | 42 (63.6%) | 20 (47.62%) |

Prevalence and Clonal Distribution of C. jejuni in Wild Mice

Campylobacter jejuni was not isolated from any of the 49 M. musculus (0%), whereas C. jejuni was isolated from 42 of 66 M. minutus (63.6%). C. jejuni was isolated in 12 out of 14 sesame fields where M. minutus were captured; only one M. minutus mouse each was captured from field 05 and from field 19, where C. jejuni was not isolated. In addition, even in cases where the two species shared the same field, C. jejuni was isolated only from M. minutus (Table 2). No difference was observed in the prevalence of C. jejuni in M. minutus based on the gender/age of the wild mice or the region/year in which wild mice were captured.

Multilocus sequence typing analysis for all isolates revealed that the sequences of seven housekeeping genes (aspA, glnA, gltA, glyA, pgm, tkt, and uncA) were identical, regardless of various factors (gender, age, region, and year). In other words, only one ST was found among all 42 C. jejuni isolates from M. minutus. All sequences were submitted to PubMLST and a new ST, ST-8388 (aspA: 7, glnA: 618, gltA: 303, glyA: 688, pgm: 823, tkt: 645, and uncA: 6), was determined.

Virulence/Survival Factors Profile and Antibiotic-Resistance Patterns of C. jejuni in Wild Mice

Among 10 virulence- and survival-related genes, flhB, cadF, pldA, iamA, cdtB, crsA, perR, and htrA were present in all (100%) C. jejuni isolates. However, hcp was not detected in any isolates. In addition, virB11 was detected in 20/42 (47.6%) of isolates with a similar geographical distribution (Table 2). Specifically, all 20 isolates found in fields 02 (3 isolates), 13 (5 isolates), 17 (10 isolates), and 22 (2 isolates) were positive for virB11, whereas 22 isolates from other fields (fields 03, 05, 09, 14, 15, 16, 18, 19, 20, and 21) were negative for this gene. Wild mice were caught in different 2 years from fields 03 and 13, but an identical pattern was observed. In an antibiotic-resistance test, all C. jejuni isolates were susceptible to all tested antibiotics, regardless of testing method used (MIC, disk diffusion, or a sequence-based method).

Complete Genome Sequence and Genomic Characterization of Wild Mouse-Derived C. jejuni

One representative C. jejuni strain (SCJK2) was selected for sequencing, since all 42 isolates from M. minutus were presumed to be genetically identical, according to the MLST results. Based on the whole-genome sequence of M. minutus-derived C. jejuni (strain SCJK2), the complete genome has a total length of 1,859,287 bp and consists of three contigs (one chromosome and two plasmids) with an average GC content of 30.15%. The genome harbors 1,781 coding genes (chromosome: 1,642 genes; plasmid 1: 93 genes; plasmid 2: 46 genes), 44 tRNA, 9 rRNA, and 3 ncRNA (Table 3). Among these, 1,278 coding genes are assigned to EggNog/COG categories. The complete genome sequence of M. minutus-derived C. jejuni (strain SCJK2) was deposited in GenBank (accession numbers CP038862–CP038864). In virulence-factor analysis based on VFDB, the M. minutus-derived C. jejuni genome (strain SCJK2) contains most virulence-related genes associated with adherence (cadF, jlpA, porA, and pebA), colonization (capsule biosynthesis and transport-related genes), glycosylation (N-linked protein and O-linked flagella glycosylation-related genes), immune evasion (LOS-related genes), invasion (ciaB), motility (flagella-related genes), the secretion system (type IV secretion system-related genes), and toxins (cdtA/B/C). Antibiotic-resistance analysis indicated that the genome did not contain antibiotic-resistance genes which correspond to genes registered in CARD.

TABLE 3.

Genomic features of M. minutus-derived C. jejuni (str SCJK2).

| Feature | Chromosome | Plasmid 1 | Plasmid 2 | Total |

| Length (bp) | 1,737,053 | 86,091 | 36,143 | 1,859,287 |

| GC contents (%) | 30.4 | 27.9 | 25.9 | 30.2 |

| Number of coding genes | 1,642 | 93 | 46 | 1,781 |

| Number of tRNA | 44 | 0 | 0 | 44 |

| Number of rRNA | 9 | 0 | 0 | 9 |

| Number of ncRNA | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

Genetic Relatedness Between Wild Mouse-Derived C. jejuni and C. jejuni Derived From Other Sources, Based on MLST and Comparative-Genomic Analysis

A minimum-spanning tree was constructed based on MLST and was used to assess allelic differences between sequences of M. minutus-derived C. jejuni and previously reported sequences (Figure 2). In the case of C. jejuni from M. minutus, the allelic difference to the nearest ST was 5.0, indicating a low level of genetic relatedness with C. jejuni from other sources, such as humans, livestock, and the environment. The complete genome of M. minutus-derived C. jejuni (strain SCJK2) was compared with 174 other C. jejuni genome sequences from different sources (Figure 3). Among 1,203 core genes of 175 genomes, M. minutus-derived C. jejuni (strain SCJK2) did not harbor 12 genes, including aer_1 (aerotaxis receptor), glnM (putative glutamine ABC transporter permease protein), cheY (chemotaxis protein), tyrS (tyrosine-tRNA ligase), and peb1A (major cell-binding factor). In the approximately maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree, this genome sequence formed clades with other sequences. However, unlike most other sequences that were clustered by isolated country or source, this genome was not deeply clustered with other sequences, including GCF 002214785.1 and GCF 004328905.1, which were isolated from South Korea. In addition, the branch length from the closet bootstrap (0.009) in the tree of this strain was much longer than that of most other strains.

FIGURE 2.

MLST results showing the genetic relatedness between C. jejuni derived from Micromys minutus and those derived from other sources. Minimum-spanning tree based on the allelic profile of MLST, including ST-8388 isolated in this study and other STs registered in PubMLST (accessed on 20 November 2019, about 6,800 STs, https://pubmlst.org/). Cut-off value of the tree was set to allele differences of 5.0. The distance between M. minutus-derived C. jejuni (ST-8388) and the nearest ST (ST-353) was 5.0. This figure was generated using the Phyloviz software (http://www.phyloviz.net/).

FIGURE 3.

Comparative-genomic analysis of Micromys minutus-derived C. jejuni sequences (strain SCJK2) with 174 other C. jejuni sequences. An approximately maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree based on multiple alignment of core genes. Nodes lower than the cut-off value (branch length of 0.00005) were collapsed. The M. minutus-derived C. jejuni (strain SCJK2) sequence was not deeply clustered with other sequences, including GCF 002214785.1 and GCF 004328905.1, which were isolated from South Korea. In addition, the branch length (0.009) from the closet bootstrap in the tree of this strain was much longer than that of most other strains. This figure was generated using the iTOl (https://itol.embl.de/).

Discussion

This is the first study to identify and characterize C. jejuni from wild mice, in addition to analyzing the genetic relatedness of wild mouse-derived strains and those derived from other sources, including humans and livestock. Wildlife animals cause many infectious diseases in humans. In particular, wild mice are known to carry various pathogens that cause diseases such as Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome 1, plague, and typhus (Kruse et al., 2004; Wolfe et al., 2007). It is likely that wild mice may be reservoirs for C. jejuni infection for humans and livestock, but this has not been clearly demonstrated (Meerburg and Kijlstra, 2007). Therefore, the objectives of this study were to determine whether wild mice are a potential reservoir of C. jejuni and whether they are involved in the transmission cycle of C. jejuni in human infections. To accomplish this, we applied traditional research approaches, such as profiling of virulence-/survival-related genes and evaluating antibiotic resistance, in addition to performing MLST analysis. Furthermore, we utilized a whole-genome sequencing/comparative-genomic analysis approach for in-depth characterization of C. jejuni from wild mice and for in-depth analysis of the genetic relatedness between wild mouse-derived C. jejuni and C. jejuni derived from previously reported sources.

We found that most M. minutus harbored C. jejuni in their gastro-intestinal tracts, regardless of various factors, such as the gender/age of the mice and the region/year in which the mice were captured. The prevalence of C. jejuni in M. minutus was 63.6% on an individual basis (42 of 66 M. minutus) and 85.7% on a regional basis (12 of 14 sesame fields). Furthermore, we did not observe any clinical symptoms or lesions in any M. minutus from which C. jejuni was isolated. Generally, in humans, C. jejuni is pathogenic and causes campylobacteriosis, which can result in gastro-intestinal and neurological diseases (Nachamkin et al., 1998). However, in poultry, C. jejuni generally exists as a commensal flora in the gastro-intestinal tract and does not cause any clinical symptoms (Silva et al., 2011). Furthermore, its prevalence in chickens exceeds 50% (Skarp et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2019). Therefore, the high prevalence of C. jejuni in wild mice combined with the absence of any clinical symptoms suggest that C. jejuni could be a member of the normal gut flora in wild mice, similar to the situation with poultry.

We performed MLST, the most commonly used epidemiological tool for C. jejuni (Dingle et al., 2001), on all isolates to investigate the origin of C. jejuni in wild mice, in addition to the genetic relationship among isolates. Surprisingly, all 42 isolates from wild mice were from a single clone C. jejuni (ST-8388), although these M. minutus were captured from different habitats during different years, and were not all of the same gender. Moreover, this MLST type had not been previously reported. It is generally known that the genetic diversity of C. jejuni is higher than that of other microorganisms due to frequent genetic exchange (Young et al., 2007). Therefore, a variety of genetically different C. jejuni clones is distributed worldwide (Dingle et al., 2002), and more than 6,800 C. jejuni MLST types are registered in PubMLST (accessed on 20 November 2019). Previous studies on livestock, including cattle, sheep, pigs, and poultry have indicated that, though the frequency of a specific sequence is often host-dependent, diverse genotypes of C. jejuni strains can be distributed among the same hosts and individuals (Colles et al., 2009; Ogden et al., 2009). For example, in cattle or poultry, various clones of C. jejuni may be present, even if the experiment was carried out on the same farm (Behringer et al., 2011; An et al., 2018). Despite the previously determined genetic diversity of C. jejuni, the absence of genetic heterogeneity among all isolates in this study suggests that C. jejuni from wild mice may have adapted to the gastrointestinal tract (GI) of M. minutus and that all isolates were genetically similar to each other, a result that has not been seen with other C. jejuni hosts. In addition, M. minutus-derived C. jejuni formed separate clusters from other host-derived C. jejuni in the MLST analysis, suggesting that the origin of C. jejuni in wild mice might differ from that of other hosts, including livestock and humans.

In this study, none of the C. jejuni isolates from wild mice exhibited resistance to any antibiotics either phenotypically or genetically. Antibiotic-resistance patterns are generally used as an indicator of exposure histories for previous antibiotic use. Recently, due to the increased use of antibiotics for therapeutic or sub-therapeutic purposes in humans and livestock, a greater number of C. jejuni antibiotic-resistant strains have been found worldwide, especially those resistant to fluoroquinolones and tetracycline (Alfredson and Korolik, 2007; Luangtongkum et al., 2009). Antibiotic resistance in C. jejuni has been found to be especially severe in Korea. According to statistics provided by the Animal and Plant Quarantine Agency of Korea7 (accessed on May 2019) over the last 2 years, the antibiotic-resistance rates of poultry-derived C. jejuni against ciprofloxacin, nalidixic acid, and tetracycline were 97.4, 94.7, and 63.2%, respectively. In addition, almost all C. jejuni isolates from humans and livestock in Korea were resistant to at least one antibiotic (Kim et al., 2016; Chon et al., 2018). However, in this study, the antibiotic-resistance patterns of C. jejuni from wild mice deviated from this pattern. These results might provide evidence that wild mice were not previously exposed to antibiotics. Furthermore, considering that C. jejuni acquires antibiotic resistance by taking up foreign DNA, which makes antibiotic resistance easily transmitted between strains (Bae et al., 2014), C. jejuni from wild mice most likely had not been transmitted from other sources, such as livestock or humans that were frequently exposed to antibiotics.

Furthermore, in this study, C. jejuni from wild mice also had unique virulence/survival profiles compared to those of C. jejuni derived from other sources. Because of the high genetic diversity of C. jejuni mentioned above, differences in the virulence/survival profiles of C. jejuni have been observed in most previous studies for the same host, and even in studies of livestock in the same farm (Young et al., 2007; An et al., 2018). However, the presence or absence of virulence/survival genes in all isolates from this study was similar, except for the virB11 gene. This similarity might be related to the distribution of single C. jejuni clone among the M. minutus, as mentioned in the section “Genetic Relatedness Between Wild Mouse-Derived C. jejuni and C. jejuni Derived From Other Sources, Based on MLST and Comparative-Genomic Analysis.” The presence/absence of the virB11 gene was not the same for each isolate. However, if a single C. jejuni isolate from wild mice captured in one sesame field harbored this gene, then all isolates from wild mice captured in that field harbored the gene, even though the mouse were captured under different piles of dry sesame plants. Similarly, if a single C. jejuni isolate from wild mice captured in one sesame field did not harbor this gene, then no isolates from wild mice captured in that field harbored the gene (Table 2). VirB11, which is present on the pVir plasmid encoding a type-IV secretion system, is involved in horizontal gene transfer and is easily transferred between strains (Juhas et al., 2008); in the case of livestock, its distribution tendency has been found to be similar for the same farm (An et al., 2018). Therefore, the distribution of the virB11 gene in this study suggests that horizontal transmission of C. jejuni may occur frequently among M. minutus that share the same habitat. Alternatively, vertical transmission of C. jejuni harboring the virB11 gene may occur continuously, since wild mice captured in the same sesame field could all be family members.

To investigate the possibility of C. jejuni transmission from wild mice to humans, we investigated the habitat of wild mice (Figure 1). Two possible transmission routes can be considered for an event from wild mice to humans: either direct transmission through contact with the wild mice, or indirect transmission through the environment or livestock. Both routes involve sharing of a neighboring environment between humans and wild mice. M. musculus and M. minutus are widely distributed throughout Asia and Europe (Miyashita et al., 1985; Jing et al., 2015), and in particular, these two species are common in the South Korea (Kim et al., 2013). M. musculus, which has been domesticated as a laboratory mouse or pet, have been found in close proximity to commercial structures and have come into contact with humans (Panti-May et al., 2012). In contrast, M. minutus live in open communities, including mountains and agricultural fields, and have a unique nesting behavior, where small shelter nests are built off the ground (Jing et al., 2015). In this study, even though two wild mice species were caught in sesame fields, M. musculus were typically caught in the vicinity of human houses, indicating that M. musculus most likely have more contact with humans. However, M. minutus were caught in remote areas of human houses, which reduced the possibility of human contact. Therefore, since C. jejuni was isolated only from M. minutus, and there was a low chance of contact between M. minutus and humans/livestock, the probability of C. jejuni transmission from wild mouse to humans can be assumed to be relatively low.

Furthermore, to identify genetic traces of M. minutus-derived C. jejuni in other hosts, we compared the genetic relatedness of C. jejuni from M. minutus and other sources previously reported in the PubMLST and NCBI Genome databases, using MLST and comparative-genomic analysis. The relatively large distance of C. jejuni wild mouse isolates from other STs (i.e., from a different host or source) in the MST based on MLST allelic profiles suggests that M. minutus-derived C. jejuni is a novel strain that is not genetically closely related to C. jejuni derived from other sources. In the comparative genomic analysis conducted in this study, we did not find great genetic relatedness between M. minutus-derived C. jejuni and those derived from other sources (humans, livestock, environmental sources, and other wildlife). These results also indicate that C. jejuni derived from M. minutus might be a novel strain and has a different ancestral lineage from those derived from other hosts. Furthermore, there are no evidence for a genetic trace that could indicate a role for wild mice in the transmission of C. jejuni to other hosts.

Conclusion

In conclusion, based on the absence of clinical signs in wild mice harboring C. jejuni, in addition to its high prevalence, single clonal distribution, and lack of resistance to any tested antibiotics, we hypothesize that C. jejuni most likely forms a normal component of the gut flora of M. minutus and all C. jejuni isolates are adapted to the GI tract of M. minutus. In addition, the probability of C. jejuni transmission from M. minutus to humans is relatively low because M. minutus and other hosts did not share neighboring environments and genetic relatedness was not observed between C. jejuni derived from M. minutus and other sources. In summary, M. minutus might be a potential reservoir of C. jejuni, a novel strain that is genetically different from those of other sources, but is most likely not involved in C. jejuni transmission to other hosts, including humans and livestock.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets (genome sequence of C. jejuni strain SCJK2) for this study were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers CP038862–CP038864.

Ethics Statement

The animal study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Hallym University approval (Hallym2017-5).

Author Contributions

SC and JGS conceived the study. J-HG, S-HM, J-UA, WK, SL, and HS performed the sampling and experiments. JKS prepared and reviewed the manuscript. JK made a great contribution to the experiments and preparing the manuscript. All authors have approved the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding. This research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-234 2018R1A2B6002396) and the Korea Mouse Phenotyping Project (2016M3A9D5A01952417) of the Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2019.03066/full#supplementary-material

References

- Alfredson D. A., Korolik V. (2007). Antibiotic resistance and resistance mechanisms in Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 277 123–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An J.-U., Ho H., Kim J., Kim W.-H., Kim J., Lee S., et al. (2018). Dairy cattle, a potential reservoir of human campylobacteriosis: epidemiological and molecular characterization of Campylobacter jejuni from cattle farms. Front. Microbiol. 9:3136. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.03136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae J., Oh E., Jeon B. (2014). Enhanced transmission of antibiotic resistance in Campylobacter jejuni biofilms by natural transformation. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58 7573–7575. 10.1128/AAC.04066-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behringer M., Miller W. G., Oyarzabal O. A. (2011). Typing of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli isolated from live broilers and retail broiler meat by flaA-RFLP, MLST, PFGE and REP-PCR. J. Microbiol. Methods 84 194–201. 10.1016/j.mimet.2010.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronowski C., James C. E., Winstanley C. (2014). Role of environmental survival in transmission of Campylobacter jejuni. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 356 8–19. 10.1111/1574-6968.12488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bui X. T., Qvortrup K., Wolff A., Bang D. D., Creuzenet C. (2012). Effect of environmental stress factors on the uptake and survival of Campylobacter jejuni in Acanthamoeba castellanii. BMC Microbiol. 12:232. 10.1186/1471-2180-12-232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Zheng D., Liu B., Yang J., Jin Q. (2015). VFDB 2016: hierarchical and refined dataset for big data analysis—10 years on. Nucleic Acids Res. 44 D694–D697. 10.1093/nar/gkv1239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin C.-S., Alexander D. H., Marks P., Klammer A. A., Drake J., Heiner C., et al. (2013). Nonhybrid, finished microbial genome assemblies from long-read SMRT sequencing data. Nat. Methods 10:563. 10.1038/nmeth.2474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chon J.-W., Lee S.-K., Yoon Y., Yoon K.-S., Kwak H.-S., Joo I.-S., et al. (2018). Quantitative prevalence and characterization of Campylobacter from chicken and duck carcasses from poultry slaughterhouses in South Korea. Poultry Sci. 97 2909–2916. 10.3382/ps/pey120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colles F., McCarthy N., Howe J., Devereux C., Gosler A., Maiden M. (2009). Dynamics of Campylobacter colonization of a natural host, Sturnus vulgaris (European starling). Environ. Microbiol. 11 258–267. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01773.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta S., Niwa H., Itoh K. (2003). Prevalence of 11 pathogenic genes of Campylobacter jejuni by PCR in strains isolated from humans, poultry meat and broiler and bovine faeces. J. Med. Microbiol. 52 345–348. 10.1099/jmm.0.05056-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingle K. E., Colles F. M., Ure R., Wagenaar J. A., Duim B., Bolton F. J., et al. (2002). Molecular characterization of Campylobacter jejuni clones: a basis for epidemiologic investigation. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8:949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingle K. E., Colles F. M., Wareing D. R., Ure R., Fox A. J., Bolton F. E., et al. (2001). Multilocus sequence typing system for Campylobacter jejuni. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39 14–23. 10.1128/JCM.39.1.14-23.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francisco A. P., Vaz C., Monteiro P. T., Melo-Cristino J., Ramirez M., Carriço J. A. (2012). PHYLOViZ: phylogenetic inference and data visualization for sequence based typing methods. BMC Bioinformatics 13:87. 10.1186/1471-2105-13-87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French N. P., Midwinter A., Holland B., Collins-Emerson J., Pattison R., Colles F., et al. (2009). Molecular epidemiology of Campylobacter jejuni isolates from wild-bird fecal material in children’s playgrounds. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75 779–783. 10.1128/AEM.01979-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibreel A., Tracz D. M., Nonaka L., Ngo T. M., Connell S. R., Taylor D. E. (2004). Incidence of antibiotic resistance in Campylobacter jejuni isolated in Alberta, Canada, from 1999 to 2002, with special reference to tet (O)-mediated tetracycline resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48 3442–3450. 10.1128/aac.48.9.3442-3450.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Hein G., Huaracán B., García P., Figueroa G. (2013). Prevalence of virulence genes in strains of Campylobacter jejuni isolated from human, bovine and broiler. Braz. J. Microbiol. 44 1223–1229. 10.1590/s1517-83822013000400028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gras L. M., Smid J. H., Wagenaar J. A., de Boer A. G., Havelaar A. H., Friesema I. H., et al. (2012). Risk factors for campylobacteriosis of chicken, ruminant, and environmental origin: a combined case-control and source attribution analysis. PLoS One 7:e42599. 10.1371/journal.pone.0042599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han B. A., Schmidt J. P., Bowden S. E., Drake J. M. (2015). Rodent reservoirs of future zoonotic diseases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112 7039–7044. 10.1073/pnas.1501598112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison J. W., Dung T. T. N., Siddiqui F., Korbrisate S., Bukhari H., Tra M. P. V., et al. (2014). Identification of possible virulence marker from Campylobacter jejuni isolates. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 20:1026. 10.3201/eid2006.130635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia B., Raphenya A. R., Alcock B., Waglechner N., Guo P., Tsang K. K., et al. (2016). CARD 2017: expansion and model-centric curation of the comprehensive antibiotic resistance database. Nucleic Acids Res. 45 D566–D573. 10.1093/nar/gkw1004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing J., Song X., Yan C., Lu T., Zhang X., Yue B. (2015). Phylogenetic analyses of the harvest mouse, Micromys minutus (Rodentia: Muridae) based on the complete mitogenome sequences. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 62 121–127. 10.1016/j.bse.2015.08.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Juhas M., Crook D. W., Hood D. W. (2008). Type IV secretion systems: tools of bacterial horizontal gene transfer and virulence. Cellular microbiology 10 2377–2386. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01187.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaakoush N. O., Castaño-Rodríguez N., Mitchell H. M., Man S. M. (2015). Global epidemiology of Campylobacter infection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 28 687–720. 10.1128/CMR.00006-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M., Sato Y., Kawashima M., Furumichi M., Tanabe M. (2015). KEGG as a reference resource for gene and protein annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 44 D457–D462. 10.1093/nar/gkv1070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. C., Chong S. T., Nunn P. V., Jang W.-J., Klein T. A., Robbins R. G. (2013). Seasonal abundance of ticks collected from live-captured small mammals in Gyeonggi Province. Republic of Korea, during 2009. Syst. Appl. Acarol. 18 201–212. [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Guk J.-H., Mun S.-H., An J.-U., Song H., Kim J., et al. (2019). Metagenomic analysis of isolation methods of a targeted microbe, Campylobacter jejuni, from chicken feces with high microbial contamination. Microbiome 7:67. 10.1186/s40168-019-0680-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Lee M., Kim S., Jeon S. E., Cha I., Hong S., et al. (2016). High-level ciprofloxacin-resistant Campylobacter jejuni isolates circulating in humans and animals in incheon. Republic of Korea. Zoonoses Public Health 63 545–554. 10.1111/zph.12262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konkel M. E., Gray S. A., Kim B. J., Garvis S. G., Yoon J. (1999). Identification of the enteropathogensCampylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli based on the cadF virulence gene and its product. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37 510–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koolman L., Whyte P., Burgess C., Bolton D. (2015). Distribution of virulence-associated genes in a selection of Campylobacter isolates. Foodborne pathog. Dis. 12 424–432. 10.1089/fpd.2014.1883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruse H., Kirkemo A.-M., Handeland K. (2004). Wildlife as source of zoonotic infections. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 10:2067. 10.3201/eid1012.040707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löytynoja A. (2014). “Phylogeny-Aware Alignment with PRANK,” in Multiple Sequence Alignment Methods. Berlin: Springer, 155–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luangtongkum T., Jeon B., Han J., Plummer P., Logue C. M., Zhang Q. (2009). Antibiotic resistance in Campylobacter: emergence, transmission and persistence. Future Microbiol. 4 189–200. 10.2217/17460913.4.2.189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mace S., Haddad N., Zagorec M., Tresse O. (2015). Influence of measurement and control of microaerobic gaseous atmospheres in methods for Campylobacter growth studies. Food Microbiol. 52 169–176. 10.1016/j.fm.2015.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meerburg B., Jacobs-Reitsma W., Wagenaar J., Kijlstra A. (2006). Presence of Salmonella and Campylobacter spp. in wild small mammals on organic farms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72 960–962. 10.1128/aem.72.1.960-962.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meerburg B. G., Kijlstra A. (2007). Role of rodents in transmission of Salmonella and Campylobacter. J. Sci. Food Agricult. 87 2774–2781. 10.1111/zph.12147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyashita N., Moriwaki K., Minezawa M., Yonekawa H., Bonhomme F., Migita S., et al. (1985). Allelic constitution of the hemoglobin beta chain in wild populations of the house mouse. Mus musculus. Biochem. Genet. 23 975–986. 10.1007/bf00499941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller J., Schulze F., Müller W., Hänel I. (2006). PCR detection of virulence-associated genes in Campylobacter jejuni strains with differential ability to invade Caco-2 cells and to colonize the chick gut. Vet. Microbiol. 113 123–129. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2005.10.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachamkin I., Allos B. M., Ho T. (1998). Campylobacter species and Guillain-Barre syndrome. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11 555–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden I. D., Dallas J. F., MacRae M., Rotariu O., Reay K. W., Leitch M., et al. (2009). Campylobacter excreted into the environment by animal sources: prevalence, concentration shed, and host association. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 6 1161–1170. 10.1089/fpd.2009.0327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overbeek R., Begley T., Butler R. M., Choudhuri J. V., Chuang H.-Y., Cohoon M., et al. (2005). The subsystems approach to genome annotation and its use in the project to annotate 1000 genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 33 5691–5702. 10.1093/nar/gki866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page A. J., Cummins C. A., Hunt M., Wong V. K., Reuter S., Holden M. T., et al. (2015). Roary: rapid large-scale prokaryote pan genome analysis. Bioinformatics 31 3691–3693. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panti-May J. A., Hernández-Betancourt S., Ruíz-Piña H., Medina-Peralta S. (2012). Abundance and population parameters of commensal rodents present in rural households in Yucatan, Mexico. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 66 77–81. 10.1016/j.ibiod.2011.10.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Powell S., Forslund K., Szklarczyk D., Trachana K., Roth A., Huerta-Cepas J., et al. (2014). eggNOG v4. 0: nested orthology inference across 3686 organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 42 D231–D239. 10.1093/nar/gkt1253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price M. N., Dehal P. S., Arkin A. P. (2010). FastTree 2–approximately maximum-likelihood trees for large alignments. PLoS One 5:e9490. 10.1371/journal.pone.0009490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pundir S., Magrane M., Martin M. J., O’Donovan C., Consortium U. (2015). Searching and navigating UniProt databases. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 50:1.27.1-10. 10.1002/0471250953.bi0127s50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seemann T. (2014). Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 30 2068–2069. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva J., Leite D., Fernandes M., Mena C., Gibbs P. A., Teixeira P. (2011). Campylobacter spp. as a foodborne pathogen: a review. Front. Microbiol. 2:200. 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skarp C., Hänninen M.-L., Rautelin H. (2016). Campylobacteriosis: the role of poultry meat. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 22 103–109. 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldenström J., On S., Ottvall R., Hasselquist D., Olsen B. (2007). Species diversity of campylobacteria in a wild bird community in Sweden. J. Appl. Microbiol. 102 424–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G., Clark C. G., Taylor T. M., Pucknell C., Barton C., Price L., et al. (2002). Colony multiplex PCR assay for identification and differentiation of Campylobacter jejuni, C. coli, C. lari, C. upsaliensis, and C. fetus subsp. fetus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40 4744–4747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weis A. M., Storey D. B., Taff C. C., Townsend A. K., Huang B. C., Kong N. T., et al. (2016). Genomic comparison of Campylobacter spp. and their potential for zoonotic transmission between birds, primates, and livestock. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 82 7165–7175. 10.1128/aem.01746-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe N. D., Dunavan C. P., Diamond J. (2007). Origins of major human infectious diseases. Nature 447:279. 10.1038/nature05775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young K. T., Davis L. M., Dirita V. J. (2007). Campylobacter jejuni: molecular biology and pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5 665–679. 10.1038/nrmicro1718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zirnstein G., Li Y., Swaminathan B., Angulo F. (1999). Ciprofloxacin resistance in Campylobacter jejuniIsolates: detection of gyrA resistance mutations by mismatch amplification mutation assay PCR and DNA sequence analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37 3276–3280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets (genome sequence of C. jejuni strain SCJK2) for this study were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers CP038862–CP038864.