Abstract

Aim

As a population ages, it can impact on the characteristics and outcomes of cardiogenic out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) patients. This study aimed to evaluate the relationship between the age incidence of cardiogenic OHCA and population aging.

Methods

This was a post‐hoc analysis of the Pan Asian Resuscitation Outcomes Study (PAROS) database. Data on the population old‐age dependency ratio (i.e. elderly/non‐elderly) were extracted from publicly accessible sources (United Nations and World Health Organization).

Results

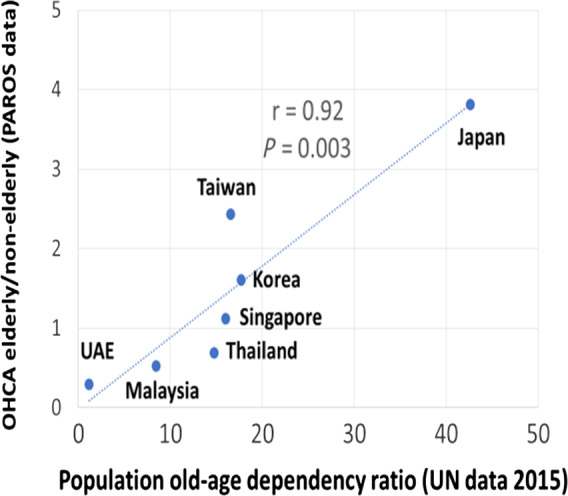

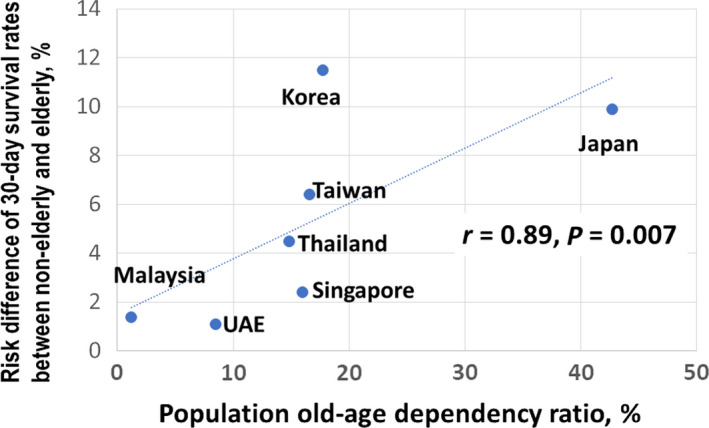

We analyzed 40,872 OHCA cases from seven PAROS countries over the period 2009 to 2013. We found significant correlation between the population old‐age dependency ratio and elderly/non‐elderly ratio in OHCA patients (r = 0.92, P = 0.003). There was a significant correlation between the population old‐age dependency ratio and risk differences of 30‐day survival rates for non‐elderly and elderly OHCA patients (r = 0.89, P = 0.007).

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that the proportion of elderly among OHCA patients will increase, and outcomes could increasingly differ between elderly and non‐elderly as a society ages progressively. This has implications for planning and delivery of emergency services as a society ages.

Keywords: Aging, cardiac arrest, epidemiology, old‐age dependency ratio

Our findings suggest that the proportion of elderly among OHCA patients will increase, and outcomes may increasingly differ between elderly and non‐elderly as a society ages progressively. This has implications for planning and delivery of emergency services as a society ages.

Introduction

Out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) is an important public health problem affecting approximately 100,000 people per year in Japan and 300,000 people each in the USA and Europe. Previous studies suggest that one of the important factors related to the outcome of cardiogenic OHCA patients is age.1

Recent research by the World Health Organization suggests that the overall world population is rapidly aging.2 Thus, in the near future, many countries will experience an unprecedented era of an aging society.2 Aging is an important risk factor for cardiovascular diseases, including cardiogenic OHCA. Therefore, it is rational to presume that the proportion of the elderly among cardiogenic OHCA patients would also increase in the near future. The more a population ages, the older OHCA patients become. Elderly patients generally have more comorbid diseases and complications, which could result in a greater health‐care burden.3 However, very few studies have evaluated the relationship between age incidence of cardiogenic OHCA and population aging.

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the relationship between age incidence of cardiogenic OHCA and population aging in Asian countries.

Method

This was a post‐hoc analysis of the Pan Asian Resuscitation Outcomes Study (PAROS)4 data from 2009 to 2013. The study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki as reflected in a priori approval by the Institutional Review Boards. Each participating site was responsible for obtaining approval from their local ethics committee to undertake the study.4

The concept and design of PAROS has been previously described in detail.4 In short, PAROS was established in collaboration with emergency medical services agencies and academic centers in Japan, Singapore, Korea, Malaysia, Taiwan, Thailand, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE; Dubai). We reported OHCA events using common data definitions and collection methods, thus arriving at a better understanding of OHCA trends in Asia.4

We defined the elderly as those aged ≥65 years, as per previous studies and the definition provided by the United Nations.5 Old‐age dependency ratio is the ratio of the number of elderly (i.e. age ≥65 years) to the number of working‐age people (age 15–64 years). The global average of the old‐age dependency ratio in 2015 was 12.6%.5 We thus defined “aged” countries as those with an old‐age dependency ratio ≥12.6%, and “aging” countries as those with an old‐age dependency ratio <12.6%. We evaluated cardiogenic OHCA patients in the current study; non‐cardiogenic OHCA patients were excluded. We evaluated the ratio of elderly/non‐elderly (i.e. old‐age dependency ratio in population data) from both OHCA (PAROS) and population (United Nations) data for each country.5 We also extracted population life expectancy data from the 2015 World Health Organization database for the corresponding seven countries.2

The data are presented as medians and interquartile ranges. We compared “aged” and “aging” countries using the Mann–Whitney U‐test. We evaluated 30‐day survival rates in both elderly and non‐elderly patients with risk differences in each country. Spearman's correlation coefficient (r) was used to determine the correlations among the variables. The statistical significance threshold was set at P < 0.05. All analyses were carried out using IBM spss version 23 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

A total of 66,780 OHCA cases from 808 receiving hospitals and 113 emergency medical service agencies in seven countries were identified in the PAROS database from 2009 to 2013. For the current study, 40,872 cases of cardiogenic OHCA were included, after excluding 25,908 cases of non‐cardiogenic OHCA.

Although we only found a maximum difference of 8.8 years in population life expectancy between Japan and Thailand, the highest difference in population median age was 18.2 years between Japan and Malaysia (Table 1). A variety of population old‐age dependency ratios was documented among the seven countries (range, 1.2–42.7).

Table 1.

Age‐related data among seven Pan‐Asian Resuscitation Outcomes Study (PAROS) countries

| Japan | Korea | Singapore | Taiwan | Thailand | United Arab Emirates | Malaysia | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population data | |||||||

| Life expectancy† | 83.7 | 82.3 | 83.1 | 80.1 | 74.9 | 77.1 | 75 |

| Median age‡ | 45.9 | 40.8 | 40 | 39.6 | 37.8 | 33.4 | 27.7 |

| Old‐age dependency ratio‡ | 42.7 | 17.7 | 16 | 16.6 | 14.8 | 1.2 | 8.5 |

| PAROS data, n | 29,929 | 5605 | 2251 | 2384 | 210 | 362 | 131 |

| Median age (interquartile range) | 78 (18) | 70 (24) | 66 (23) | 76 (24) | 60 (27) | 51 (24) | 59 (19) |

| Proportion of elderly, % | 79.2 | 61.6 | 52.7 | 70.8 | 40.7 | 22.3 | 34.4 |

| Ratio of elderly/non‐elderly | 3.8 | 1.6 | 1.1 | 2.4 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| 30‐day survival rate among non‐elderly, % | 14.0 | 16.5 | 4.8 | 11.6 | 10.4 | 3.9 | 1.2 |

| 30‐day survival rate among elderly, % | 4.1 | 5.0 | 2.4 | 5.2 | 5.9 | 2.5 | 2.3 |

| Risk difference of 30‐day survival rates between non‐elderly and elderly, % (95% CI) | 9.9 (9.2–10.5) | 11.5 (10.0–13.1) | 2.4 (0.8–3.9) | 6.4 (4.1–8.7) | 4.5 (−3.2–8.7) | 1.4 (−3.2–6.0) | 1.1 (−5.7–3.3) |

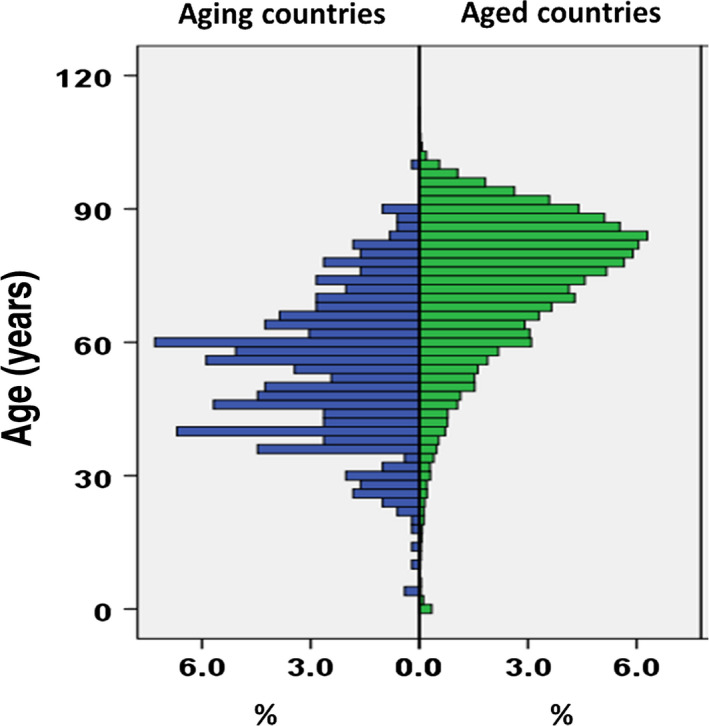

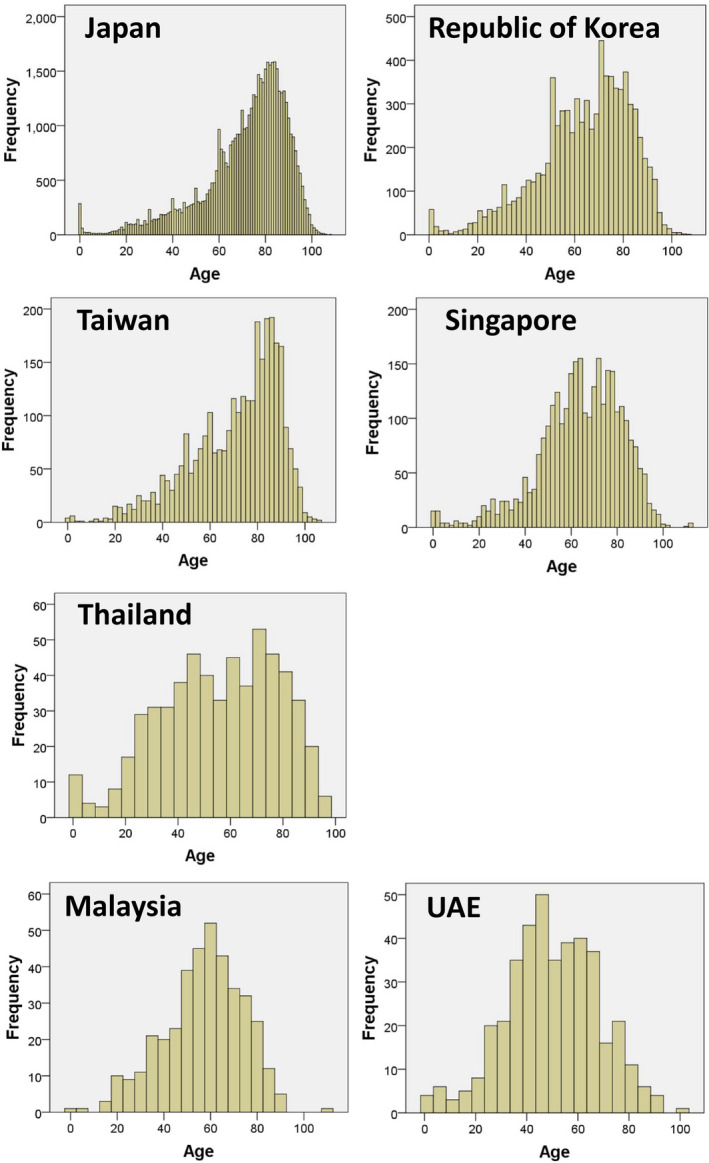

As shown in Figure 1, there was a significant difference in the age of OHCA patients between “aging” and “aged” countries (age, interquartile range: 55, 23 vs. 76, 21; P < 0.001). Figure 2 shows a histogram of the age distribution of cardiogenic OHCA in seven countries. The median age of OHCA patients in the PAROS data of Japan and Taiwan was 78 years and 76 years, respectively. In contrast, the median age of OHCA patients in the UAE was 51 years. We found a highly variable ratio of elderly/non‐elderly in OHCA patients in the seven countries (range, 0.3–3.8). We found more than 10% higher rate of 30‐day survival in non‐elderly as compared to elderly in Japan and Korea.

Figure 1.

Age distribution in out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest patients between seven “aging” and “aged” countries. We defined population “aged” countries as those with an old‐age dependency ratio ≥12.6% (global average in 2015) and population “aging” countries as those with an old‐age dependency ratio <12.6%. Population aged countries were Japan, Taiwan, Korea, Singapore, and Thailand. Population aging countries were Malaysia and the United Arab Emirates.

Figure 2.

Age distribution of cardiogenic out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest in seven countries

Although we could not find a significant correlation between population life expectancy and the median age of OHCA patients (r = −0.37, P = 0.41) or with elderly/non‐elderly ratio in OHCA patients (r = −0.24, P = 0.61), we found significant correlation between the population median age and median age of OHCA patients (r = 0.78, P = 0.04) and the elderly/non‐elderly ratio in OHCA patients (r = 0.80, P = 0.03). The population old‐age dependency ratio was significantly correlated with median age of OHCA patients (r = 0.82, P = 0.02). We found the strongest correlation between population old‐age dependency ratio and elderly/non‐elderly ratio in OHCA patients (r = 0.92, P = 0.003) (Figure 3). We investigated the risk differences in 30‐day mortality between non‐elderly and elderly patients among seven countries and found that the values were significantly correlated with the old‐age dependency ratio (r = 0.89, P = 0.007) (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Relationship between population old‐age dependency ratios of the United Nations (UN) data and elderly/non‐elderly ratios in the Pan Asian Resuscitation Outcomes Study (PAROS) data. UAE, United Arab Emirates.

Figure 4.

Relationship between population old‐age dependency ratios of the United Nations (UN) data and risk differences in 30‐day survival rates between non‐elderly and elderly individuals. UAE, United Arab Emirates.

Discussion

In this post‐hoc analysis of 40,872 cardiogenic OHCA patients using an international database from seven Asian countries, we found a significant correlation between population old‐age dependency ratios (i.e. elderly/non‐elderly) and elderly/non‐elderly ratios in OHCA patients. We also found significant correlations between risk difference of 30‐day survival rates between non‐elderly and elderly and the old‐age dependency ratio. Our findings suggest that the proportion of elderly among OHCA patients will increase and outcomes will increasingly differ between elderly and non‐elderly as a society ages progressively.

Our results are consistent with several previous studies. Becker et al.6 reported that the incidence of sudden cardiac arrest markedly increases with age, from 100 per 100,000 for 50‐year‐old patients to 800 per 100,000 for 75‐year‐old patients in Chicago, USA.6 Studies in OHCA from “aged” countries (e.g. country, old‐age dependency ratio, mean or median age of OHCA patients: Denmark, 29.7, 72.0;7 England, 28.2, 68.6;8 USA, 22.3, 60.19), show that their OHCAs seem to be older than those from “aging” countries (e.g. Cameroon, 5.9, 46.0;10 Qatar, 1.3, 51.011). As per Figure 1, we found higher proportions of older OHCA patients in “aged” countries (e.g. Japan, Taiwan, Korea, Singapore, and Thailand) than in “aging” countries (e.g. Malaysia and the UAE).

Many reports from several countries suggested that outcomes for cardiogenic OHCA have improved over the last 10 years for people aged 65 years and above.12, 13, 14, 15, 16 However, if the proportion of elderly increases among OHCA victims, the national outcomes could get worse in the near future. For example, Japan has one of the largest proportions of elderly in the world, with more than 21% of the population aged 65 years or more (old‐age dependency ratio 42.7% in 2015), and is called a “super‐aging society”.17 Owing to several investments in strengthening each link in the “chain of survival” for OHCA, the last decade has witnessed continuous improvement of favorable outcomes for cardiogenic OHCA in Japan.18 However, according to a recent report from the Japanese fire and disaster management agency, the proportion of favorable neurological outcomes and survival after 1 month among cardiogenic OHCA patients with bystander witnesses and automated external defibrillator provided has decreased for the first time since 2005. Although there might be several factors that have caused this decline in outcomes, aging could have influenced the outcome. In fact, our data found a significant correlation between the risk difference of 30‐day survival rates between non‐elderly and elderly and the old‐age dependency ratio. This might imply that the discrepancy of outcomes between the elderly and non‐elderly may increase, as a society ages progressively. This has implications for aging societies worldwide. These could include issues related to: (i) implementation of termination of resuscitation rules, (ii) geriatric medicine training for paramedics/physician, (iii) withdrawal/provision of expensive post‐resuscitation care.

The current study has some limitations. The PAROS data are not a population‐based registry in some countries, thus it may result in under‐reporting in these countries (Thailand, Malaysia). PAROS data for that period were limited only to 7 Asian countries. More data from other countries are required to confirm our results.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that the proportion of elderly among OHCA patients will increase and outcomes could increasingly differ between the elderly and non‐elderly as a society ages progressively. This has implications for planning and delivery of emergency services as a society ages.

Disclosure

Approval of the research protocol: The study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki as reflected in a priori approval by the Institutional Review Boards. Each participating site was responsible for obtaining approval from their local ethics committee to conduct the study.

Informed consent: N/A.

Registry and the registration no. of the study/trial: N/A.

Animal studies: N/A.

Conflict of interest: None.

Funding information

This work was supported in part by Grants‐in‐Aid for Scientific Research, Japan (Grant Nos. KAKENHI‐15H05685 and KAKENHI‐16KK0211) to Takashi Tagami.

References

- 1. Tanner R, Masterson S, Jensen M et al Out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrests in the older population in Ireland. Emerg. Med. J. 2017; 34: 659–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. World_Health_Organization . Available from: http://apps.who.int/gho/data/view.main.SDG2016LEXv?xml:lang=en (last updated 03, Jan, 2019).

- 3. Duong HV, Herrera LN, Moore JX et al National characteristics of emergency medical services responses for older adults in the United States. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2018; 22: 7–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ong ME, Shin SD, De Souza NN et al Outcomes for out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrests across 7 countries in Asia: The Pan Asian Resuscitation Outcomes Study (PAROS). Resuscitation. 2015; 96: 100–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. UNITED_NATIONS_DESA_POPULATION_DIVISION . Available from: https://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/Download/Standard/Population/. (last updated 03 Jan 2019).

- 6. Becker LB, Han BH, Meyer PM et al Racial differences in the incidence of cardiac arrest and subsequent survival. The CPR Chicago Project. N. Engl. J. Med. 1993; 329: 600–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wissenberg M, Lippert FK, Folke F et al Association of national initiatives to improve cardiac arrest management with rates of bystander intervention and patient survival after out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest. JAMA 2013; 310: 1377–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hawkes C, Booth S, Ji C et al Epidemiology and outcomes from out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrests in England. Resuscitation. 2017; 110: 133–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sasson C, Magid DJ, Chan P et al Association of neighborhood characteristics with bystander‐initiated CPR. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012; 367: 1607–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bonny A, Tibazarwa K, Mbouh S et al Epidemiology of sudden cardiac death in Cameroon: the first population‐based cohort survey in sub‐Saharan Africa. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2017; 46: 1230–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Irfan FB, Bhutta ZA, Castren M et al Epidemiology and outcomes of out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest in Qatar: a nationwide observational study. Int. J. Cardiol. 2016; 223: 1007–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Deasy C, Bray JE, Smith K et al Out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrests in the older age groups in Melbourne, Australia. Resuscitation. 2011; 82: 398–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. SOS‐KANTO_Study_Group . Changes in treatments and outcomes among elderly patients with out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest between 2002 and 2012: a post hoc analysis of the SOS‐KANTO 2002 and 2012. Resuscitation 2015; 97: 76–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Libungan B, Lindqvist J, Stromsoe A et al Out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest in the elderly: a large‐scale population‐based study. Resuscitation. 2015; 94: 28–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Funada A, Goto Y, Maeda T et al Improved survival with favorable neurological outcome in elderly individuals with out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest in Japan‐ A nationwide observational cohort study. Circ. J. 2016; 80: 1153–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fukuda T, Ohashi‐Fukuda N, Matsubara T et al Trends in outcomes for out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest by age in Japan: an observational study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015; 94: e2049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Muramatsu N, Akiyama H. Japan: Super‐aging society preparing for the future. Gerontologist. 2011; 51: 425–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. SOS‐KANTO_2012_Study_Group . Changes in pre‐ and in‐hospital management and outcomes for out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest between 2002 and 2012 in Kanto, Japan: the SOS‐KANTO 2012 Study. Acute Med. Surg. 2015; 2: 225–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]