Abstract

Objective

To compare the outcomes of Aquablation in 30–80 mL prostates with those in 80–150 mL prostates. Surgical options, especially with short learning curves, are limited when treating large prostates for lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) due to benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). Aquablation (AquaBeam System, PROCEPT BioRobotics Inc., Redwood City, CA, USA) could solve this issue with global reproducibility, independent of prostate volume.

Patients and Methods

Waterjet Ablation Therapy for Endoscopic Resection of prostate tissue (WATER [W‐I]; NCT02505919) is a prospective, double‐blind, multicentre, international clinical trial comparing Aquablation and transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) for the treatment of LUTS/BPH in prostates between 30 and 80 mL. WATER II (W‐II; NCT03123250) is a prospective, multicentre, single‐arm international clinical trial of Aquablation in prostates between 80 and 150 mL. We compare baseline parameters and 12‐month outcomes in 116 W‐I and 101 W‐II study patients. Students’ t‐test or Wilcoxon tests were used for continuous variables and Fisher’s test for binary variables.

Results

The mean (SD) operative time was 33 (17) and 37 (13) min in W‐I and W‐II, respectively. Actual treatment time was 4 and 8 min in W‐I and W‐II, respectively. The mean change in the International Prostate Symptom Score was substantial averaging (at 12 months) 15.1 in W‐I and 17.1 in W‐II (P = 0.605). By 3 months, Clavien–Dindo grade ≥II events occurred in 19.8% of W‐I patients and 34.7% of W‐II patients (P = 0.468).

Conclusion

Aquablation clinically normalises outcomes between patients with 30–80 mL prostates and patients with 80–150 mL prostates treated for LUTS/BPH, with an expected increase in the risk of complications in larger prostates. Long‐term outcomes of procedure durability are needed.

Keywords: benign prostatic hyperplasia, Aquablation, Robotics, #UroBPH

Introduction

BPH is one of the most commonly diagnosed conditions of the male genitourinary tract, with moderate‐to‐severe LUTS estimated to affect up to 30% of men aged >50 years and >90% in men aged >80 years 1. It is an important burden both in terms of health‐related quality of life (QOL) for the patient 2 and cost for society 3.

The initial management of most cases of BPH is non‐surgical and includes active surveillance and medical therapy 1. Surgical management of LUTS due to BPH is indicated in patients with LUTS refractory to the non‐surgical approach and in other specific situations, such as urinary retention 4. TURP for small‐to‐moderate glands is considered the historic ‘gold standard’ 5. More novel approaches include minimally invasive surgical treatments such as transurethral laser photo‐vaporisation of the prostate (PVP), as well as non‐tissue resective techniques, such as steam injection therapy (Rezum) and the use of implants (UroLift) 1. Additionally, enucleation techniques are always appropriate. It is important to consider the patient’s individual characteristics and the surgeon’s experience when considering surgical intervention 4.

For larger prostates of >80 mL, many of these options are not recommended per American, Canadian, and European Urological Association guidelines 4, 6, 7. Open prostatectomy (OP) remains the global reference standard for the surgical treatment of LUTS due to BPH in large prostates 4, 5. However, OP requires abdominal‐wall access and is associated with longer hospitalisation and catheterisation times with higher risks of bleeding 8, 9. Laser enucleation techniques, such as holmium laser enucleation of the prostate (HoLEP), have shown over two decades of evidence superior safety profiles with regards to complications rates 10, and also have the added benefit of being volume‐independent 11. However, HoLEP remains hindered by its steep learning curve (most often through a dedicated fellowship) and need for intra‐vesical tissue morcellation, limiting its widespread adoption 12. PVP has been used to treat large prostates in the context of BPH, but again requires a significant learning curve and prolonged operative time 13. To palliate the previously highlighted limitations, the BPH surgical armamentarium needs effective and volume‐independent options with smooth learning curves.

Aquablation (AquaBeam System, PROCEPT BioRobotics Inc., USA) may offer a unique solution in this challenging space. Aquablation, harnessing high‐pressure waterjet technology that eliminates the possibility of complications arising from thermal injury, was approved by the USA Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as an option for the management of LUTS due to BPH. In addition to the heat‐free waterjet, Aquablation combines real‐time, multidimensional imaging for improved decision‐making and surgical planning, with the accuracy of autonomous robotic execution following the surgeon’s aforementioned planning.

Since the first‐in‐man study of Aquablation for LUTS due to BPH published in 2016 14, additional studies have supported the safety and effectiveness of Aquablation with short learning curves required to demonstrate that the technology was safe and effective 15, 16. These outcomes are potentially volume‐independent, as explored in a recent sub‐analysis of the Waterjet Ablation Therapy for Endoscopic Resection of prostate tissue trial (WATER II [W‐II]) data, which found that Aquablation clinically normalised outcomes between patients of the <100 and >100 mL prostate cohorts 17.

Building on the existing literature, the aim of the present study was to determine if the effectiveness of Aquablation is independent of prostate size by comparing its outcomes in enlarged prostates between 30 and 80 mL with enlarged prostates between 80 and 150 mL from two separate clinical trials.

Patients and Methods

Trial Designs And Participants

WATER (W‐I; NCT02505919) is a prospective, double‐blind, multicentre, international clinical trial comparing the safety and efficacy of Aquablation and TURP as surgical treatments of LUTS due to BPH in men aged 45–80 years with a prostate volume between 30 and 80 mL, as measured by TRUS. Patients were enrolled at 17 centres between November 2015 and December 2016. They had moderate‐to‐severe symptoms as indicated by a baseline IPSS of ≥12 and a maximum urinary flow rate (Qmax) of <15 mL/s. Men were excluded from analysis if they had a body mass index of ≥42 kg/m2, a history of prostate or bladder cancer, neurogenic bladder, bladder calculus or clinically significant bladder diverticulum, active infection, treatment for chronic prostatitis, diagnosis of urethral stricture, meatal stenosis or bladder neck contracture, a damaged external urinary sphincter, stress urinary incontinence, post‐void residual urine volume (PVR) >300 mL or urinary retention, self‐catheterisation use, or prior prostate surgery. Men receiving anticoagulants or bladder anticholinergics and those with severe cardiovascular disease were also excluded.

W‐II (NCT03123250) is a prospective, multicentre, international clinical trial of Aquablation for the surgical treatment of LUTS/BPH in men aged 45–80 years with a prostate volume between 80 and 150 mL, as measured by TRUS. Patients were enrolled at 13 USA and three Canadian sites between September and December 2017. Patients on catheter use and those who had prior surgery were allowed to participate in W‐II. All other inclusion and exclusion criteria were the same as in W‐I. All patients provided informed consent using study‐specific forms prior to any test that went beyond standard care.

Intervention

The Aquablation procedure was performed using the AquaBeam System (PROCEPT BioRobotics), as previously described 14. Following the Aquablation treatment, the bladder was thoroughly irrigated to remove residual prostate tissue and blood clots. Haemostasis was achieved using tissue catheter tamponade with a low‐pressure Foley balloon catheter, which was inflated with 40–80 mL saline either at the bladder neck or within the prostatic fossa. The first 46 (40%) cases performed in W‐I used non‐resective cautery after Aquablation. The remaining 60% utilised balloon inflation in the prostatic fossa. In W‐II, bladder neck traction using a catheter tensioning device was used without any form of cautery.

Study Parameters

At baseline, patients completed the IPSS; answered validated questionnaires such as the Incontinence Severity Index (ISI), five‐item version of the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF‐5), and the Male Sexual Health Questionnaire for Ejaculatory Dysfunction (MSHQ‐EjD); received uroflowmetry, as well as PVR measurements; and underwent standard laboratory blood assessment. Questionnaires, uroflowmetry, PVR and laboratory tests were also required at the postoperative visits at 1 and 3 months. Adverse events rated by the clinical events committee as possibly, probably or definitely related to the study procedure were classified using the Clavien–Dindo grade for 3 months after treatment.

Statistical Analysis

The Student’s t‐test or Wilcoxon test was used for continuous variables and Fisher’s test for ordinal/binary variables. Prostate volume was analysed as both a continuous variable and grouped consistent with study (30–80 mL for W‐I vs 80–150 mL for W‐II). Repeated measures ANOVA was used to compare responses across time points accounting for score clustering within patients. All statistical analyses were performed using the R programming language (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Due to different follow‐up time periods, analyses through to month 12 are reported herein.

Results

The baseline characteristics of the study patients were similar (Table 1), with the exception of prostate volume, PSA level, and lower mean IIEF‐5 score.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics by study.

| Characteristic | W‐I | W‐II | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (sd) | 65.9 (7.3) | 67.5 (6.6) | 0.085 |

| Body mass index, mean (sd) | 28.4 (4.1) | 28.3 (4.1) | 0.823 |

| PSA level, g/dL, mean (sd) | 3.7 (3) | 7.1 (5.9) | <0.001 |

| Prostate size (TRUS), mL, mean (sd) | 54.1 (16.3) | 107.4 (20.2) | <0.001 |

| Median lobe present, n/N (%) | 58 (50) | 73 (72) | 0.004 |

| Intravesical component | 42/58 (72) | 69/73 (95) | |

| Use of catheters within 45 days prior to consent, n (%) | 0* | 16 (16) | – |

| Baseline questionnaires | |||

| IPSS, mean (sd) | 22.9 (6) | 23.2 (6.3) | 0.693 |

| IPSS‐QOL, mean (sd) | 4.8 (1.1) | 4.6 (1) | 0.181 |

| Sexually active, n (%) [MSHQ‐EjD] | 93 (80.2) | 77 (76.2) | 0.338 |

| MSHQ‐EjD, mean (sd)* | 8.1 (3.7) | 8.1 (3.9) | 0.916 |

| IIEF‐5, mean (sd)* | 17.2 (6.5) | 15.1 (7.4) | 0.050 |

Catheter use was excluded from W‐I. Patients reporting urinary catheter use in the 14 days prior to evaluation or with history of intermittent self‐catheterisation were excluded from W‐I.

The resection time, operative time (handpiece in to catheter in), handpiece in/out time, TRUS time (TRUS in to catheter in), and number of handpiece‐passes were statistically correlated with prostate volume (P < 0.001; Table 2 and 3). The length of stay for the <80 mL group was 1.4 days and was 1.6 days for the >80 mL group (P = 0.007). Using general linear modelling, a 50 mL prostate predicted mean operative time was 31 min; for a 100 mL prostate the predicted time was 38 min. Prostate resection efficiency rates were similar (Fig. 1). In recovery, postoperative pain medication in W‐I vs W‐II was 47% and 74%, respectively. The likely reason W‐II required more pain management was due to increased traction, as all cases were performed without cautery for haemostasis.

Table 2.

Procedure outcomes by study.

| W‐I cohort | W‐II cohort | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (sd; range) | Mean (sd; range) | ||

| Aquablation resection time, min | 3.9 (1.4; 2–11) | 8 (3.2; 2.5–17) | <0.001 |

| Operative time (handpiece in to catheter in), min | 32.8 (16.5; 10–96) | 37.4 (13.5; 15–97) | 0.027 |

| TRUS in to catheter in, min | 39.7 (15.2; 15–94) | 54.5 (19.2; 24–111) | <0.001 |

| Number of aquablation passes | 1.1 (0.3; 1–2) | 1.8 (0.6; 1–3) | <0.001 |

| Catheter days | 2 (2.3; 0.25–19 | 3.9 (3.6; 0.7–30) | <0.001 |

| Hospital length of stay, days | 1.4 (0.7; 1–5) | 1.6 (1.0; 0–6) | 0.087 |

| Haemoglobin at discharge, g/dL | 13.0 (1.7; 7.6–16) | 11.9 (2.2; 6.9–17) | <0.001 |

Table 3.

Laboratory changes and long‐term efficacy/re‐intervention.

| W‐I | W‐II | P* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean (sd) | N | Mean (sd) | |||

| PSA level, g/dL | ||||||

| Baseline | 116 | 3.7 (3) | 100 | 7.1 (5.9) | <0.001 | |

| 6 months | 110 | 2.5 (2) | 94 | 3.9 (3.8) | 0.001 | |

| 12 months | 114 | 2.7 (2.3) | 94 | 4.4 (4.3) | 0.001 | |

| TRUS volume, mL | ||||||

| Baseline | 54.1 (16.3) | 107.4 (20.2) | <0.001 | |||

| 3 months | 37.2 (15.6) | 63.1 (25.8) | <0.001 | |||

| Change at 3 months | −17.3 (14.4) | −44.2 (22.4) | <0.001 | |||

| Change as percentage, % (n) | −31 (22) | −42 (19) | <0.001 | |||

| Re‐interventions for symptomatic BPH by 12 months, n (%) | 3 (2.6) | 0 (0) | 0.250 | |||

| Proportion with chronic indwelling urinary catheter at 12 months, % | 0 | 0 | n/a | |||

Figure 1.

Baseline scores by prostate volume.

There was no relationship between baseline total IPSS, IPSS‐storage (IPSS‐S) and ‐voiding (IPSS‐V) subscores, or IPSS‐QOL and prostate volume (analysed both as a continuous variable and a binary variable by study). Not surprisingly, baseline Qmax was lower (P = 0.007) and PVR was higher (P = 0.007) with increasing prostate size.

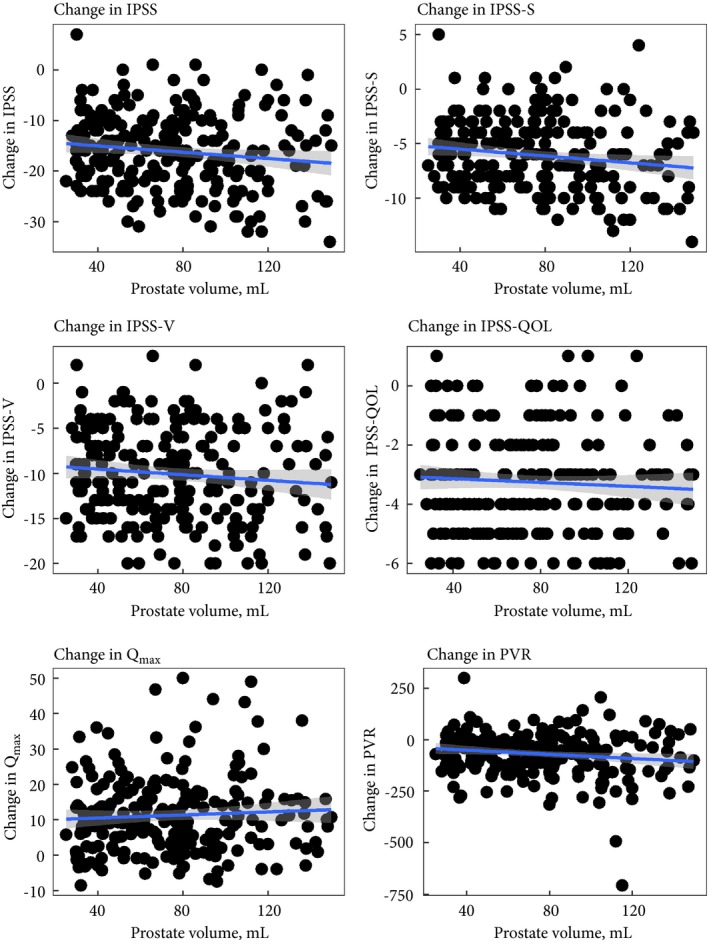

Repeated measures ANOVA for change scores between months 1 and 12 showed no statistically significant differences in responses across studies for all four variables (total IPSS, IPSS‐QOL, IPSS‐S, and IPSS‐V; Fig. 2). Repeated measures analysis was also used to examine differences in the change from baseline in Qmax, mean urinary flow rate (Qmean), and PVR across all follow‐up visits (1, 3, 6 and 12 months). No statistically significant differences across studies were observed for Qmax and Qmean; PVR decreased by 31 mL more in W‐II compared to W‐I (P = 0.020), but baseline PVR was higher in W‐II; when controlling for baseline PVR, change scores were similar between studies (P = 0.722; Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

Month 12 scores by prostate volume.

Figure 3.

12‐month change scores by prostate volume.

At month 12, no measure (total IPSS, IPSS‐S and IPSS‐V, IPSS‐QOL, Qmax, and PVR) was statistically significantly related to prostate volume (Fig. 2). Score improvements from baseline to 12 months were slightly larger in larger prostate volumes for total IPSS (P = 0.043), IPSS‐S (P = 0.02) and PVR (P = 0.027, Fig. 3), all of which could be related to slightly larger values at baseline in patients with larger prostate volumes (Figs 4, 5, 6).

Figure 4.

Aquablation resection efficiency.

Figure 5.

Change in total IPSS, IPSS‐QOL, IPSS‐V, and IPSS‐S.

Figure 6.

Qmax, PVR, and voided volume.

Transient Clavien–Dindo grade I perioperative complications occurred at a similar rate across studies. Clavien–Dindo persistent grade I events (mostly anejaculation) were more common in W‐II than in W‐I (18% vs 6%). Similarly, Clavien–Dindo grade II, III and IV events occurred at a slightly higher rate in W‐II (Table 4). Most of the Clavien–Dindo grade ≥II events were grade II, mainly comprised of bladder spasms and UTIs treated with standard pharmaceutical agents. In the W‐I study; the occurrence of Clavien–Dindo grade ≥II events was similar between Aquablation and TURP. The Clavien–Dindo grade ≥III events for both W‐I and W‐II were comprised of bleeding, where treatment was either a return to the operating room for fulguration or transfusion, or a urethral stricture/meatal stenosis treated via balloon dilatation 18, 19.

Table 4.

Number and rate of perioperative complications by day 210 in W‐I and W‐II.

| Clavien–Dindo grade | W‐I | W‐II | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N events | N subjects (rate %) | N events | N subjects (rate %) | ||

| I, not persistent | 82 | 47 (40.5) | 69 | 33 (32.7) | 0.768 |

| I, persistent* | 7 | 7 (6) | 20 | 18 (17.8) | 0.003 |

| II | 23 | 20 (17.2) | 26 | 22 (21.8) | 0.137 |

| III | 7 | 6 (5.2) | 15 | 13 (12.9) | 0.021 |

| IV | 1 | 1 (0.9) | 6 | 5 (5) | 0.052 |

Persistent outcomes: anejaculation, erectile dysfunction, or incontinence requiring a pad that do not resolve.

Discussion

Our present analysis of the trial data demonstrates that the clinical benefits of Aquablation for LUTS due to BPH in small‐to‐moderate sized prostates (30–80 mL) transfers to large‐to‐very‐large prostates (80–150 mL). The overall differences in procedural times and maintenance of antegrade ejaculation between both cohorts were statistically significant but clinically unimportant. Aquablation is a safe and effective treatment option in small‐to‐moderate sized (30–80 mL) and large‐to‐very‐large (80–150 mL) prostates, with an expected increase in complications in W‐II.

The mean operative and resection times in W‐II were respectively 37 and 8 min, which represents a difference of 4 min compared to W‐I. Although this represents a statistically significant difference, it is clinically not meaningful. Aquablation’s procedure time is significantly shorter than the average operative time associated with the treatment of a 100 mL prostate via OP (95 min) 20, HoLEP (72–118 min) 21 or PVP (93 min) 13. The 4‐min increase is also clinically not meaningful and comparable to other modalities. These operative times were those observed in surgeons who had little to no experience with the Aquablation procedure. In fact, nine out of 16 W‐II sites had never performed an Aquablation procedure before enrolling their first patient in the trial. The operative time may improve with greater surgical experience and proficiency with technique and instrumentation. For example, in a cohort of 118 unselected, consecutive patients with a mean prostate volume of 64.3 mL performed by a single surgeon, Bach et al. 22 reported a mean procedure time of 20 min.

The prostate resection efficiency rate in W‐I and W‐II were similar and averaged ~5 mL/min. On average, HoLEP’s resection efficiency rate has been reported to be ~1.46 mL/min 23 based on final pathological specimen weight, and PVP’s ~0.58 mL/min 24 based on TRUS volume at 3 months. While Aquablation’s and PVP’s values might not be as precise as the HoLEP values and may actually underestimate the amount of tissue resected as they rely on postoperative TRUS, there will likely be less inter‐operator variability with Aquablation as it is an autonomous robotically executed procedure.

Differences in Qmax and IPSS between both cohorts were not statistically significant and there was little relationship between prostate volume as a continuous variable and each score examined. The scores were comparable to those found with HoLEP (IPSS drops from 20 to 5.3 and Qmax increases from 8.4 to 22.7 mL/s) 21 and PVP (IPSS drops from 23 to 6 and Qmax increases from 6 to 16 mL/s) 25. Score improvements at 12 months were large across all prostate volumes, with slightly larger improvements in larger prostate sizes, possibly due to modest differences at baseline. Aquablation thus presents similar clinical outcomes between both cohorts. In terms of incontinence, the differences in the ISI were not significant, there were only two de novo cases of incontinence in the W‐II cohort and none in the W‐I cohort 19.

Maintenance of antegrade ejaculation was slightly lower in W‐II (81%) compared to 90% in the smaller prostates of W‐I. This difference is likely explained by a deeper, more aggressive, resection around the verumontanum in W‐II compared to W‐I. However, the rate of retrograde ejaculation with Aquablation is strikingly lower than that of OP (almost all patients) 26, HoLEP (76.3%) 27, and PVP (41.9%) 27. As sexual QOL is an important aspect of overall QOL, the higher rates of antegrade ejaculation with Aquablation represents a significant and important improvement compared to established surgical techniques. Regardless of prostate size, Aquablation is superior in terms of preservation of antegrade ejaculation when compared to volume‐independent alternatives like HoLEP and PVP.

The overall complications associated with Aquablation were mostly low grade and acceptable. In the W‐I trial looking at small‐to‐moderate sized prostates, the rate of Clavien–Dindo ≥II events was less compared to similar sized prostates undergoing TURP 15. Our present analysis of the trials’ data, indicated that there was a statistically significant (14.9%) higher complication rate with greater blood loss in the W‐II cohort compared to W‐I, which is expected with larger prostate glands. The study was also purposefully done completely athermal; it is possible that some cases in the W‐II cohort could have benefited from focal cautery. In addition, in the W‐I trial, cautery was performed on 40% of patients. No cautery was performed in any of the larger glands in W‐II. When dealing with smaller prostates, blood transfusion rates for PVP and HoLEP were respectively between 0% and 2% 21, 28. For larger prostates, the reported rates increased significantly between 12% and 29% for simple OP 29, 4% for PVP 29, and 3% for HoLEP 30. At the Montreal site (n = 12), no W‐II patients required a blood transfusion 31. This is likely due to the postoperative procedure care. Unique to the procedures performed in Montreal, the bladder was maintained under pressure and the saline bag was attached as quickly as possible to maintain bladder pressure, while the outflow was plugged. The saline was then stopped once the bladder was full, establishing hydrostatic pressure against the bladder neck. Patients then went to recovery without continuous bladder irrigation (CBI). At ~45 min, the surgeon checked on the patient, unplugged the outflow and started CBI. During the next 1–4 h, nurses aggressively titrated down the CBI flow 31.

The mean length of stay of ~1.5 days was similar in both groups. This is comparable to HoLEP (1–1.3 days) 23 and PVP (1–2 days) 25. It is much shorter than simple OP (3–7 days) [9]. In addition, novice users of Aquablation at the Montreal site of W‐II reported two patients being sent home the same day of the procedure with catheter removal 24–48 h later 31. Again, further experience with the Aquablation system and postoperative optimisation should lead to improvements in length of stay with the procedure potentially becoming a day surgery (outpatient procedure).

It is important to consider the experience of the surgeons involved when discussing these results. In W‐I, the median (range) number of cases per surgeon was 5 (1–18), with 14 of 17 sites having no previous experience. In W‐II, the median (range) number of cases per surgeon was 4 (1–25) and the median previous experience was 0.5 (0–17) cases/surgeon. This contrasts with HoLEP and PVP that have significantly steeper learning curves, which have limited their adoption. Aquablation thus does not require much experience to achieve these outcomes, which is a benefit of an automated and image‐guided surgery.

There are limitations to our present analysis of the trials data. We did not directly compare Aquablation to volume‐independent surgical alternatives, such as HoLEP and PVP. Doing so would have been particularly beneficial in comparing complications as standardised reporting of events categorised by Clavien–Dindo grades is limited in the literature. With only a 24‐month follow‐up for W‐I and 12‐month follow‐up for W‐II, longer‐term follow‐up data from these cohorts are needed to demonstrate the durability of the treatment outcomes.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the benefits of Aquablation, including short operating room times, short length of stay, maintenance of antegrade ejaculation, and short learning curves, are comparable in both small‐to‐moderate and large‐to‐very‐large prostates. The effectiveness of Aquablation is independent of prostate size and clinically normalises outcomes between patients with 30–80 mL prostates and patients with 80–150 mL prostates treated for LUTS due to BPH, with an expected increase in the risk of complications in larger prostates.

Conflicts of Interest

Mihir Desai and Mo Bidair are consultants for PROCEPT BioRobotics. Mihir Desai is also a consultant with Auris Surgical. Kevin Zorn and Naeem Bhojani have been paid for a training session at AUA 2018. Peter Gilling, Neil Barber, and Paul Anderson have performed commercial Aquablation procedures. No other author has a conflict of interest with PROCEPT BioRobotics.

Funding

The study was funded by PROCEPT BioRobotics.

Abbreviations

- CBI

continuous bladder irrigation

- HoLEP

holmium laser enucleation of the prostate

- IIEF‐5

five‐item version of the International Index of Erectile Function

- IPSS(‐QOL)(‐S)(‐V)

IPSS(‐quality of life)(‐storage)(‐voiding)

- ISI

Incontinence Severity Index

- MSHQ‐EjD

Male Sexual Health Questionnaire for Ejaculatory Dysfunction

- OP

open prostatectomy

- PVP

photo‐vaporisation of the prostate

- PVR

post‐void residual urine volume

- Q(max)(mean)

(maximum) (mean) urinary flow rate

- QOL

quality of life

- WATER(W‐I)(W‐II)

Waterjet Ablation Therapy for Endoscopic Resection of prostate tissue trial (WATER) (WATER II)

References

- 1. McAninch JW, Lue TF, Smith DR, Lue TF, McAninch JW. Smith & Tanagho’s General Urology, 18th edn McGraw Hill Medical, editor. New York, NY: McGraw Hill Medical, 2013: 758. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Welch G, Weinger K, Barry MJ. Quality‐of‐life impact of lower urinary tract symptom severity: results from the health professionals follow‐up study. Urology 2002; 59: 245–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Taub DA, Wei JT. The economics of benign prostatic hyperplasia and lower urinary tract symptoms in the United States. Curr Urol Rep 2006; 7: 272–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Foster HE, Barry MJ, Dahm P et al. Surgical management of lower urinary tract symptoms attributed to benign prostatic hyperplasia: AUA guideline. J Urol 2018; 200: 612–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Welliver C, McVary KT. Minimally invasive and endoscopic management of benign prostatic hyperplasia In Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Partin AW, Peters CA. eds, Campbell‐Walsh Urology, 11th edn Elsevier, 2016: 2504–34 [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nickel JC, Aaron L, Barkin J, Elterman D, Nachabé M, Zorn KC. Canadian Urological Association guideline on male lower urinary tract symptoms/benign prostatic hyperplasia (MLUTS/BPH): 2018 update. Can Urol Assoc J 2018; 12: 303–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gratzke C, Bachmann A, Descazeaud A et al. EAU guidelines on the assessment of non‐neurogenic male lower urinary tract symptoms including benign prostatic obstruction. Eur Urol 2015; 67: 1099–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pariser JJ, Pearce SM, Patel SG, Bales GT. National trends of simple prostatectomy for benign prostatic hyperplasia with an analysis of risk factors for adverse perioperative outcomes. Urology 2015; 86: 721–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lin Y, Wu X, Xu A et al. Transurethral enucleation of the prostate versus transvesical open prostatectomy for large benign prostatic hyperplasia: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. World J Urol 2016; 34: 1207–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kuntz RM, Lehrich K, Ahyai SA. Holmium laser enucleation of the prostate versus open prostatectomy for prostates greater than 100 grams: 5‐year follow‐up results of a randomised clinical trial. Eur Urol 2008; 53: 160–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Elzayat EA, Habib EI, Elhilali MM. Holmium laser enucleation of the prostate: A size‐independent new “gold standard”. Urology 2005; 66: 108–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Michalak J, Tzou D, Funk J. HoLEP: the gold standard for the surgical management of BPH in the 21(st) Century. Am J Clin Exp Urol 2015; 3: 36–42 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Valdivieso R, Hueber PA, Meskawi M et al. Multicentre international experience of 532‐nm laser photoselective vaporization with GreenLight XPS in men with very large prostates. BJU Int 2018; 122: 873–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gilling P, Reuther R, Kahokehr A, Fraundorfer M. Aquablation – image‐guided robot‐assisted waterjet ablation of the prostate: initial clinical experience. BJU Int 2016; 117: 923–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gilling PJ, Barber N, Bidair M et al. Randomized controlled trial of aquablation versus transurethral resection of the prostate in benign prostatic hyperplasia: one‐year outcomes. Urology 2019; 125: 169–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bhojani N, Bidair M, Zorn KC et al. Aquablation for benign prostatic hyperplasia in large prostates (80–150 cc): 1‐year results. Urology 2019; 129: 1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bhojani N, Nguyen DD, Kaufman RP, Elterman D, Zorn KC. Comparison of <100 cc prostates and >100 cc prostates undergoing aquablation for benign prostatic hyperplasia. World J Urol 2018; 37: 1361–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gilling P, Barber N, Bidair M et al. WATER: a double‐blind, randomized, controlled trial of aquablation vs transurethral resection of the prostate in benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol 2018; 199: 1252–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Desai M, Bidair M, Zorn KC et al. Aquablation for BPH in large prostates (80–150 cc): 6‐month results from the WATER II trial. BJU Int 2019; 124: 321–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sorokin I, Sundaram V, Singla N et al. Robot‐assisted versus open simple prostatectomy for benign prostatic hyperplasia in large glands: a propensity score‐matched comparison of perioperative and short‐term outcomes. J Endourol 2017; 31: 1164–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Krambeck AE, Handa SE, Lingeman JE. Experience with more than 1,000 holmium laser prostate enucleations for benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol 2010; 183: 1105–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bach T, Giannakis I, Bachmann A et al. Aquablation of the prostate: single‐center results of a non‐selected, consecutive patient cohort. World J Urol 2019; 37: 1369–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. El Tayeb MM, Jacob JM, Bhojani N, Bammerlin E, Lingeman JE. Holmium laser enucleation of the prostate in patients requiring anticoagulation. J Endourol 2016; 30: 805–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Thomas JA, Tubaro A, Barber N et al. A multicenter randomized noninferiority trial comparing GreenLight‐XPS laser vaporization of the prostate and transurethral resection of the prostate for the treatment of benign prostatic obstruction: two‐yr outcomes of the GOLIATH study. Eur Urol 2016; 69: 94–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Valdivieso R, Hueber PA, Bruyere F et al. Multicenter international experience of 180W LBO laser photo‐vaporization in men with extremely large prostates (prostate volume >200 cc): is there a size limit? Eur Urol Suppl. 2018; 17: e191 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Saluja M, Masters J, Van Rij S. Open simple prostatectomy In: Kasivisvanathan V, Challacombe B, eds, The Big Prostate. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2018: 143–52. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Marra G, Sturch P, Oderda M, Tabatabaei S, Muir G, Gontero P. Systematic review of lower urinary tract symptoms/benign prostatic hyperplasia surgical treatments on men’s ejaculatory function: time for a bespoke approach? Int J Urol 2016; 23: 22–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ajib K, Mansour M, Zanaty M et al. Photoselective vaporization of the prostate with the 180‐W XPS‐Greenlight laser: five‐year experience of safety, efficiency, and functional outcomes. Can Urol Assoc J 2018; 12: E318–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lanchon C, Fiard G, Long J‐A et al. Open prostatectomy versus 180‐W XPS GreenLight laser vaporization: long‐term functional outcome for prostatic adenomas >80 g. Prog Urol 2018; 28: 180–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jones P, Alzweri L, Rai BP, Somani BK, Bates C, Aboumarzouk OM. Holmium laser enucleation versus simple prostatectomy for treating large prostates: Results of a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Arab J Urol 2016; 14: 50–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zorn KC, Goldenberg SL, Paterson R, So A, Elterman D, Bhojani N. Aquablation among novice users in Canada: a WATER II subpopulation analysis. Can Urol Assoc J 2018; 13: E113–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]