To the Editor,

Allergen‐specific immunotherapy (AIT) is a treatment for allergic airway disease that induces long‐term tolerance by repeated allergen injections and induced regulatory T (reg) cells at the expense of Th2 cells. Nonetheless, AIT requires large amounts of allergens that need to be administered over prolonged periods of time and treatment can induce severe side effects. Allergen‐derived peptides, encoding the dominant T‐cell epitopes, lack the capacity to bind IgE and are a safe alternative. Unfortunately, treatment response to peptide AIT is suboptimal for most allergens.1, 2 Peptides may have a short half‐life after administration and need to be phagocytosed by DCs for presentation to T cells to exert their tolerogenic activity. We have previously designed a novel strategy to increase uptake and presentation of peptides by DCs, while also influencing their tolerogenic phenotype.3

Dendritic cells (DCs) express sialic acid‐binding Ig‐like lectins (siglecs), which function as endocytic receptors. In mice, sialylation of antigens has been shown to instruct DCs to manifest an antigen‐specific tolerogenic state, enhancing generation of Treg cells while reducing the generation of inflammatory T cells.4 Therefore, we hypothesize that sialylation of peptides encoding the immunodominant T‐cell epitopes from the Phleum pratense 5a allergen (Phl‐p5a) has the potential to enhance the efficacy of peptide AIT. To test our hypothesis, we compared unmodified and sialylated Phl‐p5a‐peptides in an experimental grass pollen subcutaneous AIT (GP‐SCIT) model,5 to evaluate whether peptide SCIT is effective in suppressing allergic airway inflammation and whether the use of sialylated peptides leads to increased induction of Tregs and enhanced suppression of allergic phenotypes as compared to the unmodified peptide SCIT.

We first measured T‐cell activation by DCs loaded with unmodified or sialylated Phl‐p5a peptides in vitro. Next, GP‐sensitized mice received SCIT with unmodified or sialylated Phl‐p5a peptides (or control) followed by GP challenges to induce allergic airway inflammation. Ear swelling tests were performed, and specific immunoglobulins, airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR), and airway inflammation were measured.6

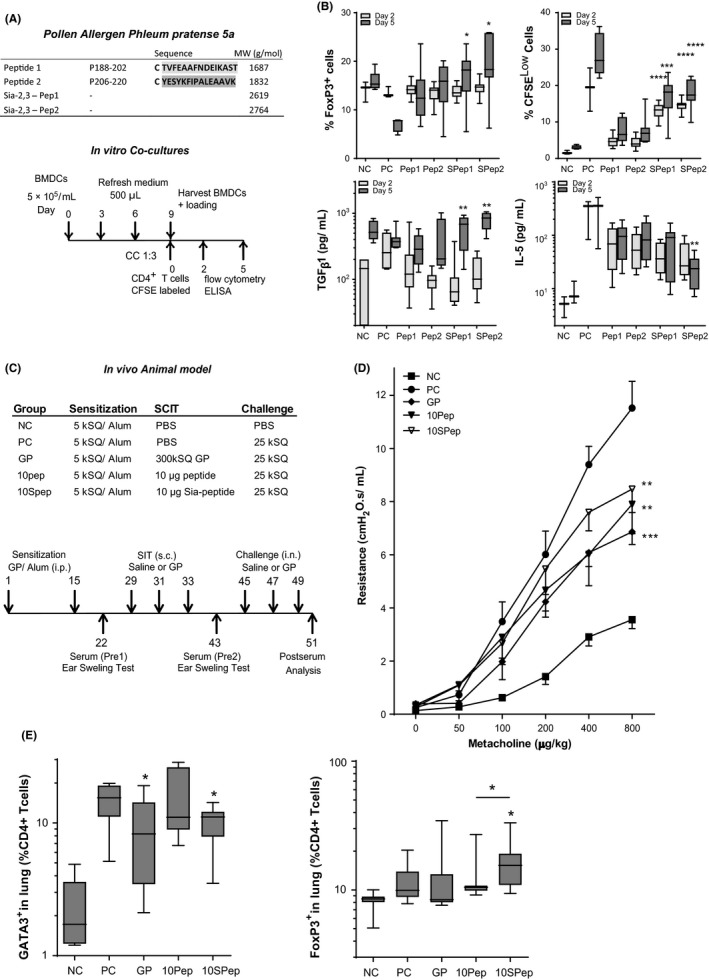

Two peptides encoding the immunodominant BALB/c T‐cell Phl‐p5a epitopes were synthesized, sialylated, and mixed in equimolar ratio for use in the in vitro T‐cell stimulations and in our in vivo SCIT model (Figures 1A‐C, S1). We observed that GP‐specific T cells showed increased proliferation, higher FoxP3 expression, and produced higher TGF‐β1 and reduced IL‐5 levels in response to Sia‐peptide‐loaded DCs, as compared to unsialylated controls (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

A, Outline of (Sia‐) peptides 1 and 2 and co‐cultures of GP‐ or (Sia)‐peptide stimulated BMDCs with CFSE‐labeled CD4+ T cells. B, FoxP3+ T cells and CFSELow T cells (both as % of total single living CD3+CD4+ T cells) and levels of TGF‐β1 and IL‐5 pg/mL, n = 12 (mean ± SEM). C, Outline of the SCIT protocol and treatment groups. D, Airway resistance (R in cmH2O.s/mL) at day 51. E, GATA3+ and FoxP3+ T cells in lung single cells (% live cells) (mean ± SEM). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.005 compared to unsialylated‐peptide

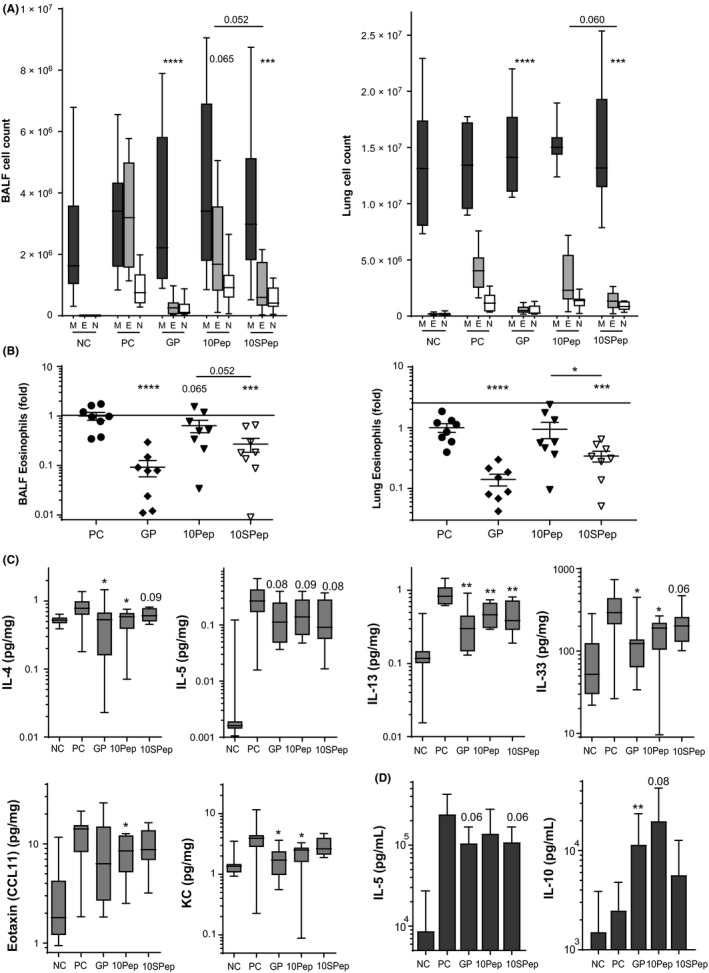

In our in vivo model, (Sia)‐peptide SCIT did not affect the GP‐specific B‐cell response, in contrast to SCIT using GP extracts (Figure S1C). In GP‐sensitized mice, GP‐SCIT and Sia‐peptide SCIT resulted in a significantly decreased ear swelling response to GP challenges, as compared to controls (Figure S2A). The airway resistance in response to a dose‐range of methacholine was significantly reduced in both GP‐SCIT and (Sia)‐peptide SCIT mice compared to controls, with no significant differences between the two treatment groups (Figure 1D). Suppression of eosinophilic airway inflammation was observed in GP‐SCIT mice compared with Sham‐treated mice in both bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) and lung tissue (Figure 2A). Although unmodified peptides failed to significantly reduce eosinophils in BALF and lung tissue compared with controls, the use of sialylated peptides did achieve a significant decrease in eosinophils in both BALF and lung tissue compared with sham‐treated mice (Figure 2A). We observed a relative suppression of eosinophil numbers by Sia‐peptide SCIT of 7‐fold for BALF and 6‐fold for lung compared with controls (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

A, Differential cytospin cell counts in BALF and in LUNG. M, Mononuclear cells; E, eosinophils; N, neutrophils. Absolute numbers are plotted in box‐and‐whiskers plots (min‐max). B, BALF eosinophils and lung eosinophils, both plotted as ratio of suppression (absolute eosinophils/average PC eosinophils; mean ± SEM). C, Levels of IL‐4, IL‐5, IL‐13, IL‐33, eotaxin, and KC (pg/mg) quantified via Luminex in lung tissue. D, Net levels of IL‐5 and IL‐10 measured in restimulated lung cells, calculated as the concentration after restimulation (30 μg GP for 5 d) minus unstimulated control (mean ± SEM, n = 8)

Next, we assessed T‐cell responses in the peptide SCIT‐treated mice. Although ILC2s numbers were unaffected by peptide SCIT in our model, the number of Th2 (GATA3+) cells was significantly decreased in lung tissue after both GP‐SCIT and Sia‐peptide SCIT treatment as compared to controls (Figures S2B, 1E). Interestingly, FoxP3+ Treg cells were increased in lung tissue only after Sia‐peptide SCIT, as compared to both controls and mice receiving the unmodified peptide (Figure 1E). We observed decreased levels of IL‐5 in BALF of GP‐SCIT mice, while IL‐10 and IL‐13 were not affected (Figure S1E). Moreover, we found significantly decreased levels of IL‐4, IL‐13, IL‐33, and IL‐17 in lung tissue from GP‐SCIT and/ or (Sia)‐peptide SCIT‐treated mice (Figures 2C, S2D).

Last, we evaluated the Th2 activity by measuring cytokine production in GP‐pulsed ex vivo‐cultured lung cell suspensions and observed a trend toward decreased levels of IL‐5, but not IL‐13, in cells from mice treated with GP‐SCIT or Sia‐peptide SCIT (Figures 2D, S2C). In addition, levels of IL‐10 were increased in cells from GP‐SCIT and unmodified peptide SCIT mice (Figure 2D). In contrast, TGF‐β1 levels were only significantly increased in lung cell suspensions from mice that had received unmodified peptide SCIT, although differences between groups were small (Figure S2C).

In this study, we provide evidence that the use of Phl‐p5a peptides for SCIT is effective in suppressing asthmatic manifestations induced by GP exposure in sensitized mice and that peptide SCIT is as effective as GP‐SCIT. Sialylation of the peptides used in SCIT resulted in increased T‐cell activation, enhanced numbers of FoxP3+ T cells both in vitro and in vivo, and achieved increased suppression of Th2 cells and eosinophilic inflammation in lung tissue compared to unmodified peptides.

Whereas the GP‐SCIT model is based on the whole GP‐extract encompassing all allergens, our peptide SCIT uses two short synthetic peptides based on the major T‐cell epitopes in Phl p5a,7 which might explain why peptide SCIT is not as effective on all parameters as the reference GP‐SCIT using crude extracts. It has recently been shown that AIT modifies CD4+ T cells in an epitope‐specific manner, resulting in depletion of those T‐cell clones that were specifically increased in allergic patients.8 Therefore, optimal peptide SCIT might require peptide sequences from all major GP allergens. Moreover, since T‐cell epitopes are dependent on MHC use, a wider variety of T‐cell epitopes will be needed to obtain a formulation that can be applied in most GP allergic individuals, while keeping the peptides as short as possible (20 AA) to prevent IgE cross‐linking and adverse events.7 Consequently, the net dosage of each individual peptide in the mixture used will be relatively low. We postulate that sialylation of the peptides used in such formulations is a valuable approach to increase efficiency of peptide SCIT.

In conclusion, the use of sialylated allergen‐derived peptides encoding T‐cell epitopes is a promising approach toward efficient and safe AIT treatment regimens.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors LH, RF, MA, WAdJ, AP, HV, WWJU, YvK, and MCN confirm that there are no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was financially supported by the Biobrug program in Groningen (Project 98 and 112). We would like to thank Uilke Brouwer (research technician) and Harold G. de Bruin for their assistance in the laboratory. Also, we thank the microsurgical team in the animal center (A. Smit‐van Oosten, M. Weij, B. Meijeringh, and A. Zandvoort) for expert assistance at various stages of the project.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hoffmann HJ, Valovirta E, Pfaar O, et al. Novel approaches and perspectives in allergen immunotherapy. Allergy. 2017;72:1022‐1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Moldaver DM, Bharhani MS, Rudulier CD, Wattie J, Inman MD, Larché M. Induction of bystander tolerance and immune deviation after Fel d 1 peptide immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143(3):1087‐1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lübbers J, Rodríguez E, Van KY. Modulation of immune tolerance via Siglec‐Sialic acid interactions. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1‐13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Perdicchio M, Ilarregui JM, Verstege MI, et al. Sialic acid‐modified antigens impose tolerance via inhibition of T‐cell proliferation and de novo induction of regulatory T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2016;113:3329‐3334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hesse L, Brouwer U, Petersen AH, et al. Subcutaneous immunotherapy suppresses Th2 inflammation and induces neutralizing antibodies, but sublingual immunotherapy suppresses airway hyperresponsiveness in grass pollen mouse models for allergic asthma. Clin Exp Allergy. 2018;48:1035‐1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hesse L, van Ieperen N, Habraken C, et al. Subcutaneous immunotherapy with purified Der p1 and 2 suppresses type 2 immunity in a murine asthma model. Allergy 2018;1‐13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sandrini A, Rolland JM, O’Hehir RE. Current developments for improving efficacy of allergy vaccines. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2015;14:1073‐1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wambre E, DeLong JH, James EA, et al. Specific immunotherapy modifies allergen‐specific CD4+ T‐cell responses in an epitope‐dependent manner. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:872‐879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials