Abstract

Natural products (NPs) from microorganisms have been important sources for discovering new therapeutic and chemical entities. While their corresponding biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) can be easily identified by gene‐sequence‐similarity‐based bioinformatics strategies, the actual access to these NPs for structure elucidation and bioactivity testing remains difficult. Deletion of the gene encoding the RNA chaperone, Hfq, results in strains losing the production of most NPs. By exchanging the native promoter of a desired BGC against an inducible promoter in Δhfq mutants, almost exclusive production of the corresponding NP from the targeted BGC in Photorhabdus, Xenorhabdus and Pseudomonas was observed including the production of several new NPs derived from previously uncharacterized non‐ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPS). This easyPACId approach (easy Promoter Activated Compound Identification) facilitates NP identification due to low interference from other NPs. Moreover, it allows direct bioactivity testing of supernatants containing secreted NPs, without laborious purification.

Keywords: bioactivity testing, easyPACId, natural products, proteobacteria, simplified production

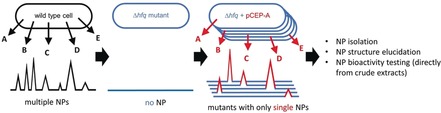

From all to nothing and back to just one! Promoter exchange in Δhfq mutants of proteobacteria allows the generation of strains that produce exclusively only one natural product (NP) class facilitating NP isolation and structure elucidation and even direct bioactivity testing of crude extracts.

Introduction

Natural products (NPs), also known as secondary or specialized metabolites, are produced by almost all bacteria, archaea and fungi. They fulfill numerous functions as part of their ecology acting for example as antibiotics, siderophores, toxins or signals mediating all aspects of organismic interaction between the microbes and their environment.1, 2 NPs and chemical derivatives thereof are also central to our health and agriculture, being applied as clinically‐relevant antibiotics, immunosuppressants, anticancer, antiviral drugs or as pesticides.3 Their biological properties are a result of their chemical structures that have been optimized during evolution towards a specific target. Hence, they represent a rich source of promising leads for new drugs capable of overcoming microbial resistances and to fight emerging diseases.

The ever‐increasing number of sequenced microbial genomes has created a number of resources and repositories for mining the data, with a particular emphasis on the identification of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) involved in NP production.4, 5 In most cases, the number of these BGCs encoded in the genomes far outnumbers the quantity of NPs produced under laboratory conditions. How to exploit the potential of this hidden chemical diversity and consequently deliver pure NPs in a simple, rapid and cost‐efficient method, gaining sufficient amounts of NPs for broad bioactivity testing is a major scientific challenge.

Different strategies have been implemented for the activation of these BGCs that sometimes might not be expressed under laboratory conditions and therefore are considered “silent”. Methods for BGC activation range from varying cultivation conditions (also called the OSMAC approach) to co‐cultivation approaches.2, 6, 7 An individual BGC can also be activated using deletion/overexpression of global (or specific) transcription factors,7, 8 application of transcription factor decoys9 or promoter exchange approaches activating these BGCs using inducible promoters.10, 11 Heterologous expression of a complete BGC has also been applied successfully for NP production.12, 13, 14 However, many challenges remain with all of these methods and particularly with heterologous hosts that may lack required building blocks (e.g. fatty acids, amino acids) for proper biosynthesis of the original NP. Furthermore, expression levels may be low due to toxicity against the heterologous producer.15

The drawback of all described approaches is that the NP of interest is generated in addition to undesired NPs that are also produced under any given condition. The resulting complex NP mixture might be very difficult to separate. Ideally, the activation of a single BGC would result in the production of a single corresponding NP and its derivatives. In the prolific NP producing bacterial genus Photorhabdus, we recently showed a dependence of NP production on the RNA chaperone, Hfq, that modulates BGC expression through sRNA/mRNA interactions.16 In a Δhfq strain, the biosynthesis of NPs is almost completely lost. Here we show that activation of desired BGCs in a Δhfq background led to the nearly exclusive production of the corresponding NPs in several proteobacteria following targeted BGC activation using the inducible promoter PBAD. Compared to BGC activation in wild type strains, or approach termed easyPACId (easy Promoter Activated Compound Identification) leads to culture supernatants lacking most undesired NPs, thereby enabling not only simplified identification and purification of the desired NP, but also direct bioactivity testing of culture extracts or supernatants against different target organisms, without time‐consuming NP purification (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic overview showing the outcome of promoter exchange for a desired biosynthetic gene cluster (BGC) in wild type (top) and Δhfq mutants (bottom) using integrative pCEP plasmids.10

Results and Discussion

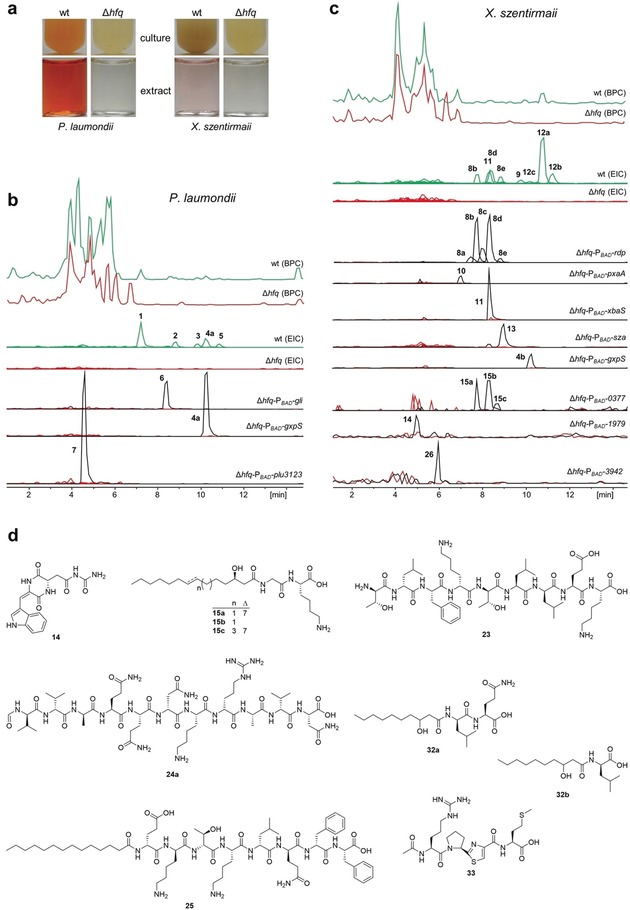

Compared to the wild type Photorhabdus laumondii TTO1 and Xenorhabdus szentirmaii, Δhfq mutants appear colorless (Figure 2 a) due to the absence of their main pigments, anthraquinones (1) and phenazines, respectively (see Supplementary Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 1 for all NP structures). HPLC‐MS analysis of culture supernatants confirmed the absence of all NPs in the Δhfq strains compared to WT when extracted ion chromatograms (EICs) of NPs were analyzed (Figure 2 b,c). Although in some Proteobacteria like Pseudomonas aeruginosa deletion of hfq results in a growth defect compared to the respective wild type,17 this was hardly observed for Photorhabdus and Xenorhabdus (Supplementary Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Promoter exchange in Δhfq results in specific NP production. a) Culture supernatants (top) and XAD‐16 extracts (bottom) of wild type (wt) and Δhfq mutants of P. laumondii TTO1 and X. szentirmaii. HPLC/MS analysis of P. laumondii TTO1 (b) and X. szentirmaii (c) wt and Δhfq mutants are shown as base peak chromatograms (BPC). For better visualization extracted ion chromatograms (EICs) representing major derivatives of all known NP classes in both strains (Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Figure 1) are shown at the bottom. For 14 and 26, the production titer was still very low compared to other NPs that only EICs of induced (red) and non‐induced Δhfq mutants (black) are shown. Both compounds were not detected in the wt. d) Structures of identified new NPs from X. szentirmaii (14, 15), Photorhabdus PB45.5 (23, 24 a), Xenorhabdus KJ12.1 (25) and Pseudomonas entomophila L48 (32, 33). The chiral centers of hydroxyl groups and amino acid residues in new NPs were predicted by analyzing the corresponding BGCs (for details see Supplementary Information A.5 and Supplementary Figure 3).

Targeted NP production in Xenorhabdus and Photorhabdus Δhfq mutants

In P. laumondii TTO1‐Δhfq, the known NPs18, 19 GameXPeptide A (4 a), glidobactin A (6), and ririwpeptide A (7) and in X. szentirmaii‐Δhfq GameXPeptides (4), rhabdopeptides (8) and pyrrolizixenamides (10) were individually produced upon promoter activation following genomic integration of the non‐replicating pCEP plasmids carrying the first 600 bp of the first gene in the BGC of interest behind the inducible PBAD promoter (Figure 1). For NPs that are also produced in wild type strains (e.g. 4, 8) their activation in a Δhfq‐mutant often leads to a strong increase in the production titer10 but with very little undesired NPs from other BGCs being produced. Furthermore, it allows the activation of BGCs that seem silent under the cultivation conditions used (6, 7, 10, 14, 15 a–c, 27). The independence of the induced promoter from (often unknown) intracellular regulation mechanisms may be a reason for this overproduction as well as the increased availability of building blocks due to all other NP pathways being inactive.

Promoter exchange of Xsze_03460 and Xsze_03680 in X. szentirmaii‐Δhfq led to the activation of the two BGC for the known xenobactin (11)20 and szentiamide (13)21 for which the BGCs had not been identified yet (Supplementary Figure 3). Promoter exchange of Xsze_03663 and Xsze_0377 in the Δhfq mutant resulted in the production of an oxidized diketopiperazine named szentirazine (14) and three lipopeptides (15 a–c) that represent shortened PAX‐peptides (Figure 2 d),22 none of which are detected in the wild type strain. The structures of 15 a–c were solved by detailed MS‐MS analysis (Supplementary Figure 4). Szentirazine (14) was isolated from a large‐scale culture and its structure was solved by NMR spectroscopy (Supplementary Figures 5–9, Supplementary Table 2). Compared to standard non‐ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPS), the bimodular NRPS involved in the production of 14 encodes an additional N‐terminal acyl‐CoA dehydrogenase (ACAD) domain23 that might introduce the double bond (Supplementary Figure 3).

When the approach was applied to additional Xenorhabdus‐Δhfq and Photorhabdus‐Δhfq strains several known (Supplementary Figure 10–12) and new NPs were readily identified showing its broad applicability: the new peptides silathride (23) and flesusides A and B (24 a and 24 b) from Photorhabdus PB45.5‐Δhfq (Figure 2 d, Supplementary Figure 12, Supplementary Table 3) and the new lipopeptide cuidadopeptide (25) from Xenorhabdus KJ12.1‐Δhfq (Figure 2 d). The structures of all new NPs were solved via a combination of labeling experiments and detailed mass spectrometry, including fragmentation analysis and comparison between the natural and synthetic NPs as shown for 23 and 24 (Supplementary Figure 13) and 25 (Supplementary Figures 14–16).

Bioactivity testing of single‐NP‐enriched Δhfq culture supernatants

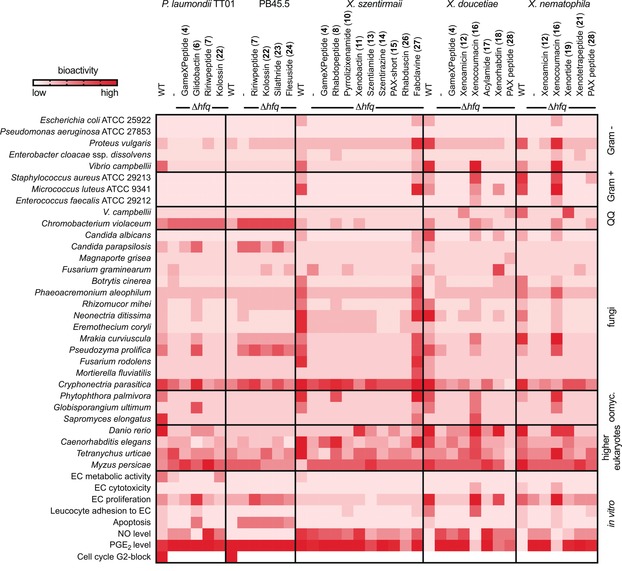

Culture supernatants of induced Δhfq‐PBAD_xy mutants grown in Luria Bertani medium enriched only with the desired NP suggested the possibility of direct testing for bioactivity. We therefore tested 38 supernatants from different strains, including the corresponding wild type and Δhfq controls, in multiple bioassays (Supplementary Table 5). These included antibiotic activity against Gram‐negative and Gram‐positive bacteria, quorum quenching (QQ) activity against Vibrio campbellii and Chromobacterium violaceum, activity against different human and plant pathogenic fungi, oomycetes, toxicity against higher organisms (zebrafish, nematodes, insects, mites) and biochemical assays (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Bioactivity of cell‐free culture supernatants enriched in desired NPs (top) derived from Δhfq‐PBAD‐xy mutants against wild type (WT) or Δhfq alone against different organisms and in vitro assays. Bioactivities are shown for none (white) to highest activity (red) in the different assays (Supplementary Table 5). For NP data and structures see Supplementary Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 1.

In these assays we observed a loss of activity for all Δhfq mutants compared to most wild type strains (Figure 3). One exception was an unknown quorum quenching activity in all Δhfq mutants of both Photorhabdus strains. Several known bioactivities were confirmed with our method, including quorum quenching activity of the phenylethylamides (17) and tryptamides against C. violaceum 24 and apoptosis‐inducing activity of the proteasome inhibitor glidobactin A (6).25, 26 Glidobactin A (6) additionally showed antifungal activity and inhibited the production of NO, but not of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) in vitro. Xenocoumacins (16 a and/or 16 b)27 and fabclavine (27)28 appeared to be the main bioactive contributors in both X. doucetiae and X. nematophila. While xenocoumacins show a broad‐spectrum bioactivity in most assays including inhibition of NO and PGE2 production, fabclavines show a similar broad‐spectrum activity without inhibiting the production of NO and PGE2. It must be mentioned that from the activation of some BGCs, multiple NP derivatives are produced (e.g. for the rhabdopeptides, xenoamicins or GameXPeptides)19 and that the corresponding bioactivity data cannot identify the active derivative. However, once a desired bioactivity is observed, the most active derivative can be identified following isolation of these derivatives and repeating the target assay(s) with the pure NPs. Differences in the amount or structure of these derivatives might also account for bioactivity differences as it was observed for activation of the xenocoumacin producing BGC in X. doucetiae and X. nematophila (compare the production of 16 in Supplementary Figure 10 and 11). While both xenocoumacin I (16 a) and xenocoumacin II (16 b) are produced in wild type and promoter exchange mutant of X. nematophila, in X. doucetiae only 16 b was observed but at a higher amount. Wild type supernatants of P. laumondii TTO1 showed a good antibiotic activity against V. campbelli that could not be repeated in any of the promoter exchange mutants suggesting that the responsible BGC was not activated. Activation of different BGCs in the same parental strain showed high bioactivity against higher eukaryotes like zebrafish and nematodes exemplified by 16/18 and 16/19 in X. doucetiae and X. nematophila. In general, the bioactivity of two NPs in the same assay might point towards an important ecological role of these NPs to act synergistically in a well‐defined (or concerted) mixture. The free‐living stage of the nematodes carrying Photorhabdus or Xenorhabdus in their gut, infect insect larvae in the soil that are used as a food source and shelter for nematode development. To guarantee an undisturbed propagation, the insect cadavers must be protected by NPs delivered by the nematode symbiont against potential food competitors including also invertebrates and vertebrates.19 Since many NPs are only produced in low amounts in the natural environment,29 synergism might be an efficient way to potentiate the overall activity as previously shown also for clinically used drugs30 while at the same time using less resources for NP production. Subsequently, activation of two BGCs together or mixing of the individual supernatants might help to elucidate such synergistic pairs.

easyPACId in Pseudomonas entomophila

Since Hfq has been shown to influence the production of some NPs in other proteobacteria like Pseudomonas, 17, 31, 32 Serratia 33, 34, 35 and Burkholderia, 36 we applied our method to Pseudomonas (Ps) entomophila since it contained known and unknown BGCs. The Δhfq mutant in Ps. entomophila showed a strong reduction of pyoverdines37 and labradorins (30)38 and a complete loss of the lipopeptide entolysin (31).39 Ps. entomophila‐Δhfq lost its swarming ability and antibiotic activity against Micrococcus luteus and Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Supplementary Figure 17). Activation of the BGC (PSEEN_RS10885) for the recently described pyreudiones (29)40 indeed resulted in the products that were not produced in the wild type strain under the cultivation conditions tested (Supplementary Figure 17). Additionally, a new tetrapeptide named pseudotetratide A (33) (Figure 2 d) was obtained from activation of PSEEN_RS12600 in the Δhfq mutant showing the potential of this approach in other NP‐producing proteobacteria encoding Hfq. The structure of 33 was confirmed after isolation from a large‐scale culture followed by detailed NMR analysis (Supplementary Figure 18–23, Supplementary Table 4).

Chances and limitations of easyPACId

If BGCs are composed of multiple separated transcription units, promoter activation of only one of these would result in only partial BGC activation and production of either none or not the complete NP. To achieve full BGC activation for complete NP production, multiple promoters must be activated. This limitation also applies to promoter activation in Δhfq mutants as it was evident for the BGC responsible for entolysin (31) biosynthesis in Ps. entomophila that is split into two loci etlA and etlBC.39 Activation of etlA encoding two NRPS modules only produced the starter fragments (32 a–b) of entolysin that were not detected in the wild type under the same conditions (Supplementary Figure 17). In cases where the biosynthesis of an unusual building block (e.g. amino acid, iso‐fatty acid) is also Hfq‐dependent, either no NP or non‐native NP derivatives will be produced which can also be advantageous due to the production of novel derivatives that the wild type does not produce. This is exemplarily shown for the production of xenorhabdins (18) in promoter exchange mutants of the X. doucetiae wild type and Δhfq strains: neither an iso‐fatty acid nor an N‐methyl group was found in the xenorhabdins produced in the Δhfq mutant in contrast to the derivatives produced in the wild type strain (Supplementary Figure 24).10 This suggests that enzymes responsible for these pathways/modifications are not encoded in the activated operon but encoded elsewhere in the genome and therefore are not produced in the Δhfq mutant. However, in general the BGC structure in proteobacteria is often rather simple compared to other prolific NP producers like actinobacteria, making them ideal targets for this approach that we termed easyPACId.

Even if Δhfq mutants would have a growth defect compared to the parental wild type strain as observed for Ps. aeruginosa 17 and Ps. entomophila (Supplementary Figure 2), the cleaner background of the Δhfq strain would still be advantageously for NP detection and isolation.

Currently, >30.000 BGCs from >24.000 unique bacterial strains are listed in the antiSMASH database,41 a repository for microbial genomes analyzed via antiSMASH. The major BGC types encode NRPS, polyketide synthases (PKS), terpene synthases and pathways involved in the production of ribosomally‐synthesized and post‐translationally modified peptides (RiPPs) but also >2000 “other” BGCs, that have not been assigned to known BGC classes so far. While Actinobacteria are still representing the majority in such databases, clearly Proteobacteria have a huge potential. In the antiSMASH database, several BGCs are found in Photorhabdus (>380), Xenorhabdus (>490), Serratia (>1200), Vibrio (>4000), Burkholderia (>11500), and Pseudomonas (>12 400) that all might be accessible to a promoter exchange in Δhfq mutants as all these strains show a reduction or loss in NP production as described here or in the literature.17, 32, 33, 34, 36

Conclusion

Although we applied easyPACId mainly to NRPS and NRPS/PKS‐derived NPs as they often represent the major NP classes, we assume that it also works for other BGC classes that are controlled by a single promoter as it is often the case in proteobacteria.42 Since the generation of Δhfq mutants as well as the activation of BGCs of interest can easily be performed in high‐throughput in these (and other) strains, it should be possible to obtain multiple new NPs in the future. This will accelerate the identification of bioactive NPs for various applications from direct testing of supernatants or crude extracts without time‐consuming isolation (Figure 3). In more well‐established NP producers like Actinobacteria, in the future maybe other global regulatory mechanisms could be used. As an example, it has been shown in Streptomyces that N‐acetylglucosamine acts as a signal for the onset of development and as a global elicitor molecule for antibiotic production.43 This said, there might also be a global suppressor mechanism for NP production in these bacteria that would be equivalent to Δhfq mutants in proteobacteria and that can be used for promoter exchange approaches even in BGCs with multiple transcriptional units applying CRISPR/Cas24 or similar technologies. In general, the isolation of NPs from such mutants with a reduced NP‐background or no NPs at all would be greatly simplified allowing the future illumination of the biosynthetic “dark matter” present in most microbes.10, 44

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the LOEWE‐Centre Translational Biodiversity Genomics (TBG) of the State of Hesse (to H.B.B., R.F., G.G., M.T., A.V.), the LOEWE research cluster MegaSyn (to H.B.B.), the LOEWE‐Centre Translational Medicine and Pharmacology (TMP) (to G.G.), the LOEWE‐Centre for Insect Biotechnology and Bioresources (to A.V.), and the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey (TUBITAK; TOVAG‐117O172). We would like to thank our students from the Goethe University Laura Pöschel, Laura Penkert, Hannah Müller and Marlen Sahlbach for help with mutant construction and synthesis of peptide standards, respectively. We are grateful to Tobias Kessel, Maximilian Seip, Jens Grotmann and Katja Michaelis from Fraunhofer Institute for Molecular Biology and Applied Ecology (Bioresources Project Group) in Giessen, Germany for their valuable help and support in this study.

E. Bode, A. K. Heinrich, M. Hirschmann, D. Abebew, Y.-N. Shi, T. D. Vo, F. Wesche, Y.-M. Shi, P. Grün, S. Simonyi, N. Keller, Y. Engel, S. Wenski, R. Bennet, S. Beyer, I. Bischoff, A. Buaya, S. Brandt, I. Cakmak, H. Çimen, S. Eckstein, D. Frank, R. Fürst, M. Gand, G. Geisslinger, S. Hazir, M. Henke, R. Heermann, V. Lecaudey, W. Schäfer, S. Schiffmann, A. Schüffler, R. Schwenk, M. Skaljac, E. Thines, M. Thines, T. Ulshöfer, A. Vilcinskas, T. A. Wichelhaus, H. B. Bode, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 18957.

References

- 1. Schmidt R., Ulanova D., Wick L. Y., Bode H. B., Garbeva P., ISME J. 2019, 13, 2656–2663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Molloy E. M., Hertweck C., Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2017, 39, 121–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Newman D. J., Cragg G. M., J. Nat. Prod. 2016, 79, 629–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Skinnider M. A., Merwin N. J., Johnston C. W., Magarvey N. A., Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, W49–W54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Blin K., Shaw S., Steinke K., Villebro R., Ziemert N., Lee S. Y., Medema M. H., Weber T., Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W81–W87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bode H. B., Bethe B., Höfs R., Zeeck A., ChemBioChem 2002, 3, 619–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brakhage A. A., Schroeckh V., Fungal Genet. Biol. 2011, 48, 15–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Okada B. K., Seyedsayamdost M. R., FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2017, 41, 19–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wang B., Guo F., Dong S.-H., Zhao H., Nat. Chem. Biol. 2019, 15, 111–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bode E., Brachmann A. O., Kegler C., Simsek R., Dauth C., Zhou Q., Kaiser M., Klemmt P., Bode H. B., ChemBioChem 2015, 16, 1115–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Biggins J. B., Kang H.-S., Ternei M. A., DeShazer D., Brady S. F., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 9484–9490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wenzel S. C., Müller R., Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2005, 16, 594–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. D′Agostino P. M., Gulder T. A. M., ACS Synth. Biol. 2018, 7, 1702–1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wang G., Zhao Z., Ke J., Engel Y., Shi Y.-M., Robinson D., Bingol K., Zhang Z., Bowen B., Louie K., et al., Nat. Microbiol. 2019, 349, 1254766–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Huo L., Hug J. J., Fu C., Bian X., Zhang Y., Müller R., Nat. Prod. Rep. 2019, 36, 1412–1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tobias N. J., Heinrich A. K., Eresmann H., Wright P. R., Neubacher N., Backofen R., Bode H. B., Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 19, 119–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sonnleitner E., Hagens S., Rosenau F., Wilhelm S., Habel A., Jäger K.-E., Bläsi U., Microb. Pathog. 2003, 35, 217–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vizcaino M. I., Guo X., Crawford J. M., J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 41, 285–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shi Y.-M., Bode H. B., Nat. Prod. Rep. 2018, 35, 309–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Grundmann F., Kaiser M., Kurz M., Schiell M., Batzer A., Bode H. B., RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 22072–22077. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ohlendorf B., Simon S., Wiese J., Imhoff J. F., Nat. Prod. Commun. 2011, 6, 1247–1250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fuchs S. W., Proschak A., Jaskolla T. W., Karas M., Bode H. B., Org. Biomol. Chem. 2011, 9, 3130–3132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schorn M., Zettler J., Noel J. P., Dorrestein P. C., Moore B. S., Kaysser L., ACS Chem. Biol. 2014, 9, 301–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bode E., He Y., Vo T. D., Schultz R., Kaiser M., Bode H. B., Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 19, 4564–4575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dudnik A., Bigler L., Dudler R., Microbiol. Res. 2013, 168, 73–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stein M. L., Beck P., Kaiser M., Dudler R., Becker C. F. W., Groll M., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 18367–18371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McInerney B. V., Taylor W. C., Lacey M. J., Akhurst R. J., Gregson R. P., J. Nat. Prod. 1991, 54, 785–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fuchs S. W., Grundmann F., Kurz M., Kaiser M., Bode H. B., ChemBioChem 2014, 15, 512–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Davies J., J. Antibiot. 2013, 66, 361–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Brochado A. R., Telzerow A., Bobonis J., Banzhaf M., Mateus A., Selkrig J., Huth E., Bassler S., Zamarreño Beas J., Zietek M., et al., Nature 2018, 559, 259–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sonnleitner E., Haas D., Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 91, 63–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wang G., Huang X., Li S., Huang J., Wei X., Li Y., Xu Y., J. Bacteriol. 2012, 194, 2443–2457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wilf N. M., Williamson N. R., Ramsay J. P., Poulter S., Bandyra K. J., Salmond G. P. C., Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 13, 2649–2666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Matilla M. A., Nogellova V., Morel B., Krell T., Salmond G. P. C., Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 18, 3635–3650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Matilla M. A., Leeper F. J., Salmond G. P. C., Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 17, 2993–3008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kim J., Mannaa M., Kim N., Lee C., Kim J., Park J., Lee H.-H., Seo Y.-S., Plant Pathol. J. 2018, 34, 412–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ringel M. T., Brüser T., Microb. Cell 2018, 5, 424–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Grundmann F., Dill V., Dowling A., Thanwisai A., Bode E., Chantratita N., ffrench-Constant R., Bode H. B., Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2012, 8, 749–752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Vallet-Gély I., Novikov A., Augusto L., Liehl P., Bolbach G., Péchy-Tarr M., Cosson P., Keel C., Caroff M., Lemaitre B., Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 910–921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Klapper M., Götze S., Barnett R., Willing K., Stallforth P., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 8944–8947; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2016, 128, 9090–9093. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Blin K., Medema M. H., Kottmann R., Lee S. Y., Weber T., Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, D555–D559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mohite O. S., Lloyd C. J., Monk J. M., Weber T., Palsson B. O., bioRxiv 2019, 10.1101/781328. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Barka E. A., Vatsa P., Sanchez L., Gaveau-Vaillant N., Jacquard C., Meier-Kolthoff J. P., Klenk H.-P., Clément C., Ouhdouch Y., van Wezel G. P., Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2016, 80, 1–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. McInerney B. V., Gregson R. P., Lacey M. J., Akhurst R. J., Lyons G. R., Rhodes S. H., Smith D. R., Engelhardt L. M., White A. H., J. Nat. Prod. 1991, 54, 774–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary