Abstract

BACKGROUND

Emblica officinalis, known as amla in Ayurveda, has been used as a folk medicine to treat numerous pathological conditions, including diabetes. However, the novel extract of E. officinalis fruit extract (amla fruit extract, AFE, Saberry®) containing 100 g kg−1 β‐glucogallin along with hydrolyzable tannins has not yet been extensively studied for its antidiabetic potential.

OBJECTIVE

The aim of this study was to investigate the antidiabetic and antioxidant activities of AFE and its stability during gastric stress as well as its thermostability.

METHODS

The effect of AFE on the inhibition of pancreatic α‐amylase and salivary α‐amylase enzymes was studied using starch and yeast α‐glucosidase enzyme using 4‐nitrophenyl α‐d‐glucopyranoside as substrate. Further, 2,2‐diphenyl‐1‐picrylhydrazyl radical scavenging and reactive oxygen species inhibition assay was performed against AFE.

RESULTS

AFE potently inhibited the activities of α‐amylase and α‐glucosidase in a concentration‐dependent manner with half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values of 135.70 μg mL−1 and 106.70 μg mL−1 respectively. Furthermore, it also showed inhibition of α‐glucosidase (IC50 562.9 μg mL−1) and dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 (DPP‐4; IC50 3770 μg mL−1) enzyme activities. AFE is a potent antioxidant showing a free radical scavenging activity (IC50 2.37 μg mL−1) and protecting against cellular reactive oxygen species (IC50 1.77 μg mL−1), and the effects elicited could be attributed to its phytoconstituents.

CONCLUSION

AFE showed significant gastric acid resistance and was also found to be thermostable against wet heat. Excellent α‐amylase, α‐glucosidase, and DPP‐4 inhibitory activities of AFE, as well as antioxidant activities, strongly recommend its use for the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus. © 2019 The Authors. Journal of The Science of Food and Agriculture published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd on behalf of Society of Chemical Industry.

Keywords: type 2 diabetes mellitus, Saberry®, amla fruit extract, α‐amylase, α‐glucosidase, DPP‐4, β‐glucogallin

Abbreviations

- AFE

amla fruit extract

- DPPH

2,2‐diphenyl‐1‐picrylhydrazyl

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- DPP‐4

dipeptidyl peptidase‐4

- GIP

Glucose‐dependent insulinotropic polypeptide

- GLP‐1

Glucagon‐like peptide–1

- BGG

β‐glucogallin

- cGMP

current good manufacturing practices

- DNS

dinitrosalicylic acid

- OD

optical density

- rhDPPIV

recombinant human DPP‐4/CD26 enzyme

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

INTRODUCTION

Carbohydrates are the most essential nutrients of the human diet on a weight basis, next only to water, and also a major component to fulfill the energy needs of the human body. As per nutritional guidelines, carbohydrates alone contribute 40–45% of our daily energy intake, of which 10–15% are simple carbohydrates or sugars and the remainder are starches and oligosaccharides.1 Complex carbohydrates from dietary food, specifically starch, must be broken down into monosaccharides (glucose) in order to be absorbed by the body to satisfy the immediate energy need and also for the storage purpose in liver and muscles.2 The breakdown of such carbohydrates is due to the hydrolytic activity of two major enzymes: amylase and glucosidase.3 In the process of carbohydrate digestion, amylase secreted by salivary glands, breaks down about 5% of carbohydrates, and later salivary amylase is destroyed in the stomach due to the highly acidic environment.4 However, when food enters the intestine, pancreatic amylases play a major role in breaking down complex carbohydrates into oligosaccharides.5 Further, glucosidase enzymes present in the intestine complete the breakdown of these oligosaccharides into monosaccharide units (glucose) that are absorbed into the body.6 Additionally, undigested carbohydrates undergo fermentation in the colon by the colonic microbiota, resulting in the production of short‐chain fatty acids that may exert a late action on satiety.7 However, excessive consumption of a high‐carbohydrate diet (high glycemic index) has been linked with the rapid rise in the blood sugar levels with increase in insulin levels.8 Moreover, an increased level of insulin has been reported to promote glucose uptake into liver cells and fatty acid synthesis that can result in the accumulation of glycogen and lipids.9 It has also been reported that the accumulation of lipid in skeletal muscle and the liver may decrease insulin sensitivity and may lead to insulin resistance, thereby giving rise to the chance of developing type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and obesity.10

Type 2 diabetes mellitus is a chronic metabolic disorder associated with a lifestyle that is characterized by hypoinsulinemia and hyperglycemia that causes serious health complications due to the known risk factor of excessive postprandial glucose excursions for developing diabetes.11, 12 The restoration of β‐cell mass and its function are of vital importance for an effective treatment. Glucagon‐like peptide—1 (GLP‐1) and glucose‐dependent insulinotropic polypeptide help to maintain the glucose homeostasis with increased β‐cell mass and function.13 GLP‐1 is a glucose‐dependent insulinotropic gut hormone secreted by the intestinal L‐cells that stimulates insulin secretion.14 However, GLP‐1 is rapidly degraded by the ubiquitous proteolytic enzyme dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 (DPP‐4). More recently, DPP‐4 inhibitors, such as gliptins, are being prescribed for the treatment of type 2 diabetes patients who have not responded well to drugs such as metformin and sulphonylureas.15 Further, DPP‐4 inhibitors are also reported to help with weight loss and to be effective in treating hyperglycemia. Hence, inhibition of DPP‐4 enzyme activity is a well‐established target and biomarker in order to discover new remedies for the management as well as in the treatment of weight loss and type 2 diabetes.16

Non therapeutic dietary strategy are being explored based on lowering the excessive intake of carbohydrates and adding more fats or soluble fiber in the diet for the management of weight loss and type 2 diabetes.11 However, usage of high fiber intake has been reported to adverse reactions resulting in gastrointestinal problems such as gas and diarrhea. Likewise, high fat induced diet has been reported for the cause of obesity and hyperlipidemia. Therefore, an alternative dietary strategy is proposed to impact the carbohydrate absorption by slowing down the complex carbohydrate breakdown in the gastrointestinal tract via inhibiting the digestive enzymes such as salivary and pancreatic amylase and also glucosidase.16 Based on this strategy, acarbose, a potent inhibitor of α‐glucosidase and pancreatic α‐amylase enzyme, has been approved as a prescription drug to treat type 2 diabetes mellitus in some countries. Plant bioactive compounds such as anthocyanins, ellagitannins, theaflavins, and catechins have also been reported to inhibit α‐glucosidase and α‐amylase activity. Therefore, bio‐actives from plant sources may offer an alternative dietary approach for the management and treatment of weight loss and type 2 diabetes mellitus.

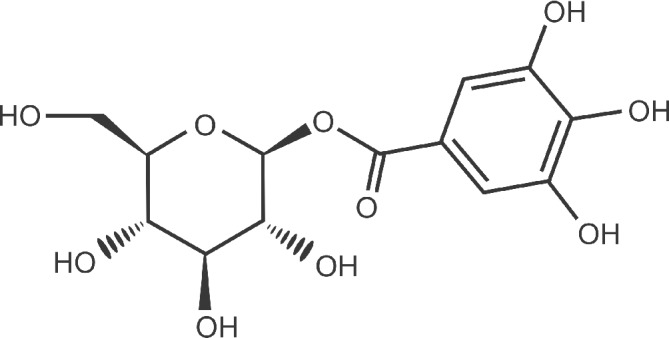

Emblica officinalis Gaertn. belongs to the Phyllanthaceae family, commonly called the Indian gooseberry, amla, and amalaki in Sanskrit. It is widely distributed in most tropical and subtropical countries.17 E. officinalis, used in Ayurveda, Unani, and in Tibetan, Sri Lankan, and Chinese systems of medicine is considered to be a powerful rejuvenator, for delaying aging and the degenerative process. Nevertheless, E. officinalis is reported for its antioxidant, gastroprotective, chemopreventive, hypolipidemic, antiviral, antibacterial, antiulcerogenic, hepatoprotective, cardiotonic, antipyretic, and antidiabetic properties.18, 19 The Saberry® brand is a proprietary patented extract of E. officinalis (synonymous with Phyllanthus emblica) fruit sold as a dietary supplement for over a decade worldwide. Saberry is a non‐genetically modified organism material, light‐colored powder that is manufactured by following a proprietary process from fresh amla fruit to obtain an extract with 100 g kg−1of β‐glucogallin (BGG) along with hydrolyzable tannins as a biomarker. Although the E. officinalis plant is reported for its antidiabetic activity, its biological properties may vary greatly based on the extraction methods and the biomarkers of a standardized preparation/extract. Therefore, there is a need for evaluation of the antidiabetic property of E. officinalis fruit extract standardized for specific biomarkers such as BGG along with hydrolyzable tannins. The literature also suggested that BGG showed better antioxidant potential when compared with ascorbic acid. Thus, we aimed to evaluate the in vitro antidiabetic activity of E. officinalis fruit extract (Saberry) containing 100 g kg−1 of BGG along with hydrolyzable tannins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

α‐Amylase, bovine serum albumin, sodium azide, 3,5‐dinitrosalicylic acid (DNS), sodium potassium tartrate, α‐glucosidase, recombinant human DPP‐4/CD26 (rhDPPIV) enzyme, BGG, 96‐well black polystyrene microplates, 4‐nitrophenyl α‐d‐glucopyranoside, dichloro‐dihydro‐fluorescein diacetate (DCFH‐DA) dye, diprotin A, human follicle dermal papilla cells, and starch were procured from Sigma‐Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA).

Preparation of standard extract of E. officinalis

AFE containing BGG along with hydrolyzable tannins was extracted from the fresh AFE (E. officinalis) as per the proprietary method of Sabinsa Corporation, USA, following current good manufacturing practices. Extraction, isolation, and quantification of the AFE were described in a previous study.20 Briefly, E. officinalis Gaertn. (Euphorbiaceae) fruits were procured locally from Bangalore, India. Fruits (10 kg) were cut into small pieces and expressed to obtain juice. Filtered juice (2.1 L) was spray dried to get 30 g of dry powder. The spray dried extract of E. officinalis was separated into seven major fractions using a preparative high‐performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system as described in a previous study.20 Different fractions 1–7 were collected as white amorphous powders.

HPLC estimation of standardized extract of E. officinalis for BGG

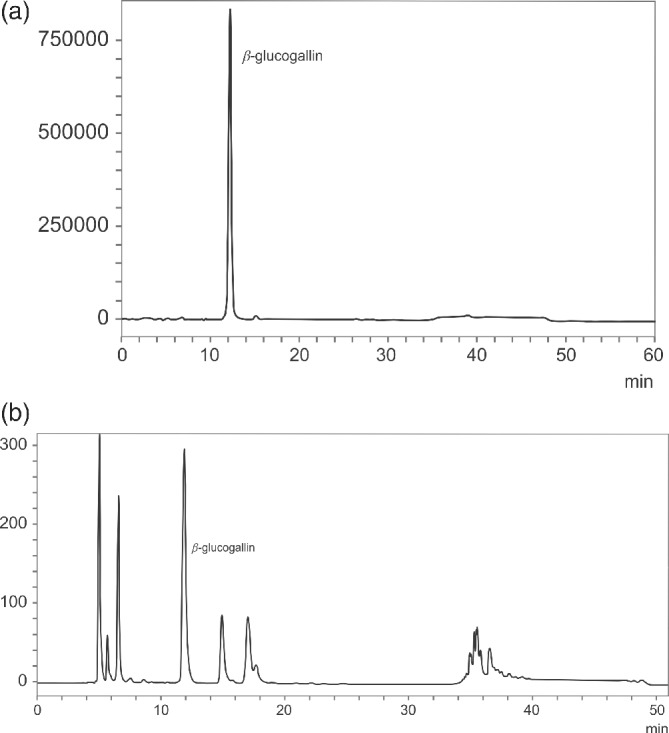

The identification and quantification of BGG were performed using a C18 DBS (Thermo) column (250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 μm) and mobile phases A (water; 0.1% formic acid) and B (methanol). The gradient used was 0–25 min, 5% B; 25–30 min, 100% B; 30–40 min, 100% B; 40–41 min, 5% B; and 40–50 min, 5% B. The injection volume was 20 μL. The flow rate was 0.7 mL min−1 and monitoring was performed at 250 and 280 nm. The standardized extract containing 100 g kg−1of BGG (Fig. 1) along with hydrolyzable tannins, including mucic acid 1,4‐lactone 5‐O‐gallate, mucic acid 2‐O‐gallate, mucic acid 6‐methyl ester 2‐O‐gallate, mucic acid 1‐methyl ester 2‐O‐gallate, and ellagic acid have been manufactured, and marketed for more than a decade under the brand name Saberry.20

Figure 1.

Structure of BGG.

α‐Amylase assay

The α‐amylase inhibitory potential of AFE was determined by the previously described method.21 Briefly, pancreatic α‐amylase from porcine pancreas (Sigma‐Aldrich) or salivary α‐amylase from human saliva (Sigma‐Aldrich) was prepared in sodium acetate buffer (0.1 mol L–1, pH 4.8). Different concentrations of AFE (1 mL, 7.8–500 μg mL−1) were incubated with α‐amylase (1 mL, 5.0 U mL−1) for 10 min at 37 °C. Starch (1 mL, 0.5% w/v) was added and the mixtures were incubated for 30 min at 37 °C, followed by the addition of DNS solution (2 mL, 40 mmol L–1 DNS, 1 mol L–1 sodium potassium tartrate, 0.4 mol L–1 sodium hydroxide) and incubated in a boiling water bath at 100 °C for 15 min. After boiling, 9 mL of demineralized water was added and the solution cooled to room temperature. The optical density was measured at a wavelength of 540 nm using a spectrophotometer (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan). A sample without adding AFE served as the untreated control. Acarbose was used as an experimental reference control. Each analysis was performed in triplicate on two different occasions. The following formula was used to calculate α‐amylase inhibition:

| (1) |

α‐Glucosidase assay

The anti‐α‐glucosidase activity of AFE was determined as per the method described previously22 with minor modifications. α‐Glucosidase (Sigma‐Aldrich) from Saccharomyces cerevisiae was dissolved in 67 mmol−1 potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6.8) containing 0.2% bovine serum albumin (Sigma‐Aldrich) and 0.02% sodium azide (Sigma‐Aldrich). AFE (50 μl) of different concentrations (62.5–1000 μg mL−1) was added to 50 μL of α‐glucosidase (0.15 U mL−1) and incubated for 5 min at 37 °C. After 5 min of incubation, 50 μL of 0.5 mmol−1 4‐nitrophenyl α‐d‐glucopyranoside (Sigma‐Aldrich) was added to the reaction and incubated for a further 20 min at 37 °C. The reaction was stopped by adding sodium carbonate (100 μL, 0.2 mol L−1) and the optical density was measured at a wavelength of 405 nm using a microplate reader (Fluostar Optima, Sigma‐Aldrich; BMG Labtech, Ortenberg, Germany). Acarbose was used as an internal experimental reference control. Each test was performed three times, and the mean absorption was used to calculate percentage α‐glucosidase inhibition using Eqn (1).

DPP‐4 assay

The antidiabetic potential of AFE was evaluated based on the inhibitory activity against rhDPPIV enzyme (Sigma‐Aldrich) using the 96‐well plate method described previously.23, 24 AFE (50 μL) at different concentrations (0.25, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, and 4.0 mg mL−1) was incubated with rhDPPIV (50 μL of 0.2 ng μL−1) for 30 min at 37 °C. After incubation, 50 μL of 20 μmol L−1 Gly‐Pro‐7‐amido‐4‐methylcoumarin hydrobromide (Bachem,Bubendorf, Switzerland catalog no.: I‐1225) was added to the reaction and further incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. After incubation, fluorescence was determined at excitation and emission wavelengths of 380 nm and 460 nm respectively in kinetic mode for 5 min. Sample without addition of AFE served as the untreated control. The assay was performed twice in triplicate with appropriate blanks and standard. Diprotin A (Sigma‐Aldrich) was used as the internal experimental control for the study. The percentage inhibition was calculated using Eqn (1).

2,2‐Diphenyl‐1‐picrylhydrazyl‐hydrate radical scavenging assay

The 2,2‐diphenyl‐1‐picrylhydrazyl‐hydrate (DPPH) radical scavenging activity of AFE was performed according to methodology described previously.25 The DPPH radical scavenging method was based on scavenging of the DPPH radical by antioxidants, producing a decrease in absorbance at 517 nm. The DPPH (Sigma‐Aldrich) was used at a concentration of 60 mmol L−1 in methyl alcohol. DPPH solution (4 mL) in methanol was mixed with 1 mL of AFE solution of varying concentrations (0.42, 0.83, 1.67, 3.33, and 6.67 μg mL−1). Corresponding blank samples were prepared, and l‐ascorbic acid (30 μg mL−1) was used as the reference standard. The reaction was carried out in triplicate, and the decrease in absorbance was measured at 517 nm after 30 min in dark using a spectrophotometer (Shimadzu Corporation). A mixture of methanol (4.0 mL) and the sample (1 mL) served as the blank. The antioxidant activity was calculated as %DPPH radical scavenging activity according to the method described previously25 by substituting the absorbance values into the following equation:

where B is the absorbance in the absence of antioxidant, C is the absorbance of the blank, and S is the absorbance in the presence of antioxidant.

Reactive oxygen species inhibition assay

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) was estimated using DCFH‐DA dye.26 Human follicle dermal papilla cells were seeded in a 96‐well black plate at a density of 1 × 104 cells per well. After 16 h of plating, cells were pretreated with different concentrations of AFE (12.5, 6.25, 3.13, 1.56, 0.78, 0.39, and 0.2 μg mL−1) for 1 h in 100 μL of Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium without phenol red followed by induction with UVB radiation (0.6 J cm−2). After specific treatment, the cells were incubated with 0.002% DCFH‐DA dye for 1 h at 37 °C. The fluorescence intensity was measured by a fluorescence microplate reader set for excitation at 485 nm and emission detection at 520 nm. The increase in fluorescence is proportional to the ROS induced. The percentage of ROS induced was calculated with respect to the fluorescence intensity of nonirradiated control cells:

where A is the fluorescence of nonirradiated cells (control) and B is the fluorescence of UVB‐irradiated cells with and without sample treatment.

Determinations of AFE stability under different thermal and pH conditions

The pH stability of AFE was determined by preincubating in buffer of different pH (1.5, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10) for 90 min at 37 °C as per the method described previously.27 After 90 min of incubation, AFE was added to the α‐amylase enzyme solution and incubated for 10 min at 37 °C followed by starch (5 mg mL−1) addition to the reaction. After 30 min of incubation, the reaction was stopped by adding DNS solution and the percentage inhibition of α‐amylase activity was determined as per the method described previously.21 Similarly, the thermostability of AFE was determined by preincubating AFE at different temperatures (37, 50, 70, and 90 °C) for 90 min. After preincubation of AFE, α‐amylase solution was added to the reaction mixture. α‐Amylase inhibition by the AFE was determined using the previously described spectrophotometer method.21

Long‐term stability studies of AFE

The effect of long‐term storage condition on the BGG content in AFE was carried out according to the International Conference on Harmonisation guidelines.28 Briefly, 5 g of AFE was sealed inside double transparent polyethylene bags (4 in. × 4 in.) and then transferred to high‐density polyethylene bottles. Samples were stored in a controlled temperature of 30 ± 2 °C with relative humidity 60 ± 5% and were analyzed at 0, 1, 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, 24, and 36 months according to the International Conference on Harmonisation guidelines.28 After every time interval, samples were analyzed for the moisture content as per United States Pharmacopoeia method (Chapter ⟨921⟩) and BGG content following the HPLC method described previously.29 Further, the α‐amylase inhibitory potential of AFE was determined by the method described previously.21

Statistical analyses

The results obtained from antidiabetic assays were expressed as mean plus/minus standard deviation from triplicate analyses. Differences between two means were evaluated by Student's t‐test. The level of statistical significance for all the tests was set at P < 0.05. For multiple comparisons, P values were determined by one‐way analysis of variance using GraphPad Prism software version 5.01 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA).

RESULTS

Identification and quantification of BGG

AFE fractions were pooled after the preparative HPLC to check the BGG content by HPLC. Fractions 2, 3, and 4 showed the presence of BGG by HPLC. The retention times of fractions matched well with standard BGG (Fig. 2). The extract was further spiked with a known concentration of BGG reference standard to quantify the compound. We have standardized a working standard for our commercial batches of 100 g kg−1 of BGG in AFE.

Figure 2.

HPLC chromatograms: (a) standard BGG; (b) AFE showing the presence of BGG.

Pancreatic α‐amylase and salivary α‐amylase

The inhibition of pancreatic α‐amylase and salivary α‐amylase enzymes was studied for AFE and the results are shown in Fig. 2. α‐Amylase cleaves the α‐(1–4) glycosidic linkages of starch, glycogen, and other oligosaccharides and yields dextrin, maltose, or maltotriose, whereas α‐glucosidase yields glucose molecules by hydrolyzing the terminal nonreducing 1–4‐linked α‐glucose. As shown in Table 1, there was release of maltose when α‐amylase was incubated with substrate; however, in the presence of AFE, the release of maltose was drastically reduced. Inhibition activity of AFE against pancreatic α‐amylase and salivary α‐amylase was concentration dependent, with half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 135.70 μg mL−1 and 106 μg mL−1 respectively (Table 1). AFE was significantly more potent against salivary α‐amylase than against porcine pancreatic pancreatin α‐amylase. Acarbose was used as a standard in the study for the inhibition of pancreatic α‐amylase and salivary α‐amylase enzymes, showing IC50 values of 25 μg mL−1 and 24.2 μg mL−1 respectively.

Table 1.

Inhibitory effect of AFE on α‐amylase, α‐glucosidase, and DPP‐4

| Inhibition (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α‐Amylase | ||||

| AFE (μg mL−1) | Porcine pancreas | Human saliva | α‐Glucosidase | DPP‐4 |

| 7.8 | 8.68 ± 1.1 | 7.58 ± 1.62 | 1.08 ± 0.29 | ND |

| 15.6 | 22.09 ± 1.87 | 24.1 ± 1.23 | 3.15 ± 0.95 | ND |

| 31.3 | 33.71 ± 1.59 | 26.54 ± 1.92 | 5.15 ± 1.14 | ND |

| 62.5 | 42.78 ± 1.24 | 40.5 ± 1.34 | 7.58 ± 1.69 | 1.26 ± 0.56 |

| 125 | 44.95 ± 1.57 | 51.24 ± 1.61 | 16.03 ± 1.82 | 2.15 ± 0.62 |

| 250 | 50.56 ± 1.98 | 65.41 ± 1.68 | 22.64 ± 1.57 | 3.41 ± 0.56 |

| 500 | 71.26 ± 1.25 | 75.24 ± 1.35 | 30.23 ± 1.98 | 9.04 ± 0.93 |

| 1000 | 84.15 ± 1.63 | 89.14 ± 1.56 | 93.92 ± 1.21 | 11.87 ± 1.08 |

| 2000 | ND | ND | ND | 27.9 ± 1.4 |

| 4000 | ND | ND | ND | 53.21 ± 4.21 |

| IC50 (μg mL−1) | ||||

| AFE | 135.70 | 106.70 | 562.9 | 3770 |

| Acarbose | 25 | 24.2 | 75 | |

| Diprotin A | 10 | |||

ND, not done.

Values are average mean of triplicates performed on two different occasions and presented as IC50 values.

α‐Glucosidase and DPP‐4 inhibition

The inhibitory effect of AFE against yeast α‐glucosidase enzyme was performed using 4‐nitrophenyl α‐d‐glucopyranoside as substrate. The inhibitory activity of AFE was concentration dependent, wherein 30.23% and 93.92% inhibitions were observed at concentrations of 500 μg mL−1 and 1000 μg mL−1 respectively, with an IC50 value of 562.9 μg mL−1 (Table 1). Furthermore, AFE exhibited a concentration‐dependent inhibitory activity against human rh DPP‐4 enzyme‐4 with highest inhibition (53.21%) at 4000 μg mL−1 (Table 1). Diprotin A was used as reference control for DPP‐4 inhibitory activity with an IC50 value of 10 μg mL−1.

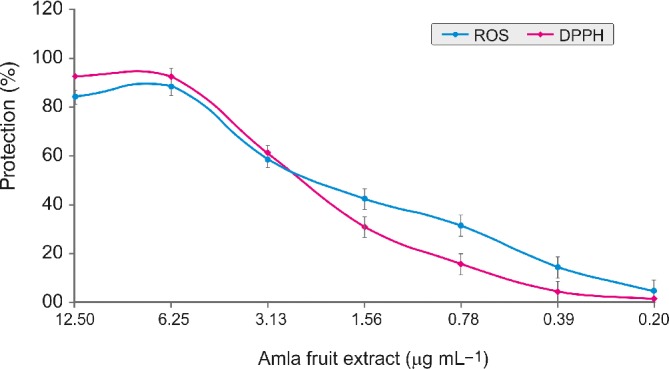

Antioxidant activity of AFE

Figure 3 shows the antioxidant capacity of AFE determined by DPPH assay and ROS scavenging assay. The DPPH radical scavenging activity was concentration dependent with the maximum protection of 92.11%, 91.78%, and 60.72% at concentrations of 12.50 μg mL−1, 6.25 μg mL−1, and 3.13 μg mL−1 respectively (Fig. 3). The IC50 value of AFE was 2.37 μg mL−1 compared with the IC50 value of standard tertiary butylhydroquinone of 2.65 μg mL−1. Furthermore, the maximum intracellular ROS generation protection by the AFE was observed at 6.25 μg mL−1 of AFE (Fig. 3). The protection of intracellular ROS generation by AFE was concentration dependent.

Figure 3.

Antioxidant activities of AFE determined by DPPH and ROS scavenging assay. Values are average mean of triplicates performed on two different occasions. Error bars represent plus/minus standard deviation.

pH and thermostability of AFE

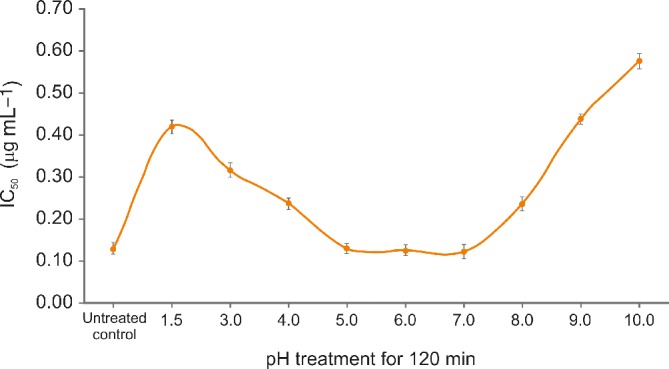

The effect of pH on the anti‐amylase activity of AFE was determined by preincubating at various pH values (1.5, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10) for 120 min. After the pH treatments, anti‐amylase activity was evaluated and compared with the untreated control. The pretreatment of AFE at pH 5, 6, and 7 for 120 min did not show any significant difference in the anti‐amylase activity when compared with untreated control (Fig. 4). However, there were approximately twofold and fourfold reductions of anti‐amylase activity of AFE when treated at pH 3.0 and pH 10.0 respectively (Fig. 4). Furthermore, the effect of wet heat on the anti‐amylase activity of AFE was evaluated at different temperatures (37, 50, 70, and 90 °C) for 90 min. The results are presented as the IC50 of AFE against pancreatic α‐amylase enzyme in Table 2. There was no significant difference in the anti‐amylase activity of AFE when incubated at 37 °C for 90 min and also at 50, 70, and 90 °C when incubated for 30 min. However, anti‐amylase activity of AFE was reduced sixfold when incubated at 90 °C for 90 min.

Figure 4.

The effect of pH on the anti‐amylase activity of AFE was determined by preincubating at different pH values for 120 min.

Table 2.

Effect of the various temperature treatments of AFE on the anti‐α‐amylase activity (IC50) µg ml−1

| IC50 µg ml−1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time (min) | 37 °C | 50 °C | 70 °C | 90 °C |

| 0 | 0.129 ± 0.004a | 0.129 ± 0.004b | 0.129 ± 0.004e | 0.129 ± 0.004h |

| 30 | 0.131 ± 0.007a | 0.132 ± 0.004b | 0.137 ± 0.008e | 0.183 ± 0.009i |

| 60 | 0.134 ± 0.005a | 0.243 ± 0.002c | 0.491 ± 0.009f | 0.513 ± 0.024j |

| 90 | 0.138 ± 0.006a | 0.581 ± 0.004d | 0.671 ± 0.019g | 0.691 ± 0.029k |

Values are average mean of triplicates performed on two different occasions and presented as IC50 values. Values in a given column followed by the same letter are not statistically different (P > 0.05). Different letters in the same row indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

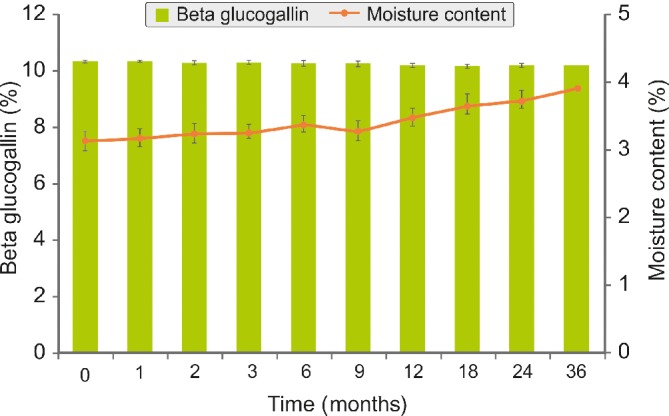

Stability of AFE at room temperature

Figure 5 shows the stability results of AFE as expressed by percentage of moisture content and BGG content. No significant reduction of BGG content was observed after 36 months of storage at a room temperature of 30 ± 2 °C with relative humidity of 65 ± 5% when compared with initial count (P > 0.05), thereby suggesting its shelf stability at room temperature. Furthermore, there was no significant difference in the α‐amylase inhibitory potential of AFE between the initial state (IC50 at 0.251 ± 0.05 mg mL−1) and after 36 months of storage (IC50 at 0.262 ± 0.07 mg mL−1). Furthermore, there was no significant difference in the moisture content and physical appearance (i.e. color, odor, and powder flow ability) upon storage for 36 months at 30 ± 2 °C (P > 0.05).

Figure 5.

Effect of storage conditions (30 ± 2 °C with 65 ± 5% relative humidity) on the BGG and moisture content of AFE. There was no significant difference in the BGG and moisture content between the initial state and after 36 months of storage. Each time point represents the percentage mean (plus/minus standard deviation) of three different experiments performed in duplicate.

DISCUSSION

It is a well‐known fact that the carbohydrate‐metabolizing enzymes α‐glucosidase and α‐amylase are the most important pharmacological targets for the management of type 2 diabetes. The inhibition of these enzymes slows down the breakdown of dietary carbohydrate, thereby modulating the postprandial blood sugar level in type 2 diabetes patients.30 This study demonstrates the α‐glucosidase and α‐amylase inhibitory potential of AFE containing 100 g kg−1 of BGG along with hydrolysable tannins. The α‐glucosidase and α‐amylase inhibitory activity of AFE is most likely to be due to BGG along with hydrolyzable tannins. Though various studies reported the hypoglycemic and antihyperglycemic activity of amla extract, a standardized preparation containing 100 g kg−1 of BGG along with hydrolyzable tannins has not been explored in detail for its enzyme inhibitory activities to the best of our knowledge. Although, amla plant (E. officinalis) has been used as a folklore medicine for its various pharmacological properties, including for diabetes, it is imperative to evaluate and validate the biological properties of a standardized preparation with different biomarkers. Furthermore, biological properties may depend on the selection of the part of the plant, the method of extraction, and, most notably, the chemical constituents present in the final preparation. The antidiabetic property of the amla extract has been associated with the presence of ascorbic acid. Previously, amla extracts were standardized using ascorbic acid as the main biomarker. However, recent research indicated that standardized amla extract did not contain substantial amounts of ascorbic acid, it often being present only in trace quantities.20, 31 Therefore, we studied a preparation standardized to contain BGG along with hydrolyzable tannins that were previously reported to exert better antioxidant potential than ascorbic acid.29 Furthermore, scientific evidence has grown on the considerable amounts of BGG in amla fruit and its positive aspects since the first disclosure by Majeed et al.20 BGG was found to be an active molecule in inhibiting human aldose reductase in an ex vivo model of cataract disease.32 The potent prevention of the conversion of glucose to sorbitol (the causative feature in the genesis of cataract in mammals) was attributed to the enhanced binding of BGG by occupying both the the anionic and the specificity pockets of human aldose reductase member AKR1B1, a member of the superfamily of aldose reductases implicated in the pathogenesis of cataract. In contrast, the standard reference material sorbinil was binding only the anionic pocket of the enzyme. It has also been demonstrated that BGG reduced the expression of inflammatory markers induced by lipopolysaccharide through aldose reductase inhibition.33 It was also established that as much as 8% of BGG was excreted in the urine samples of rats that were orally administered BGG, with a urinary half‐life of 31 h, thus demonstrating its bioavailability.34 Likewise, the current study provides further evidence of a preparation of AFE containing 100 g kg−1 of BGG along with hydrolyzable tannins exhibiting antidiabetic activity via inhibiting carbohydrate‐metabolizing enzymes (α‐glucosidase and α‐amylase).

Furthermore, in our study, AFE was able to inhibit the enzyme DPP‐4 activity in a concentration‐dependent manner, suggesting its potential role in the management of diabetes. Gliptins, a class of DPP‐4 inhibitors, are being used to treat type 2 diabetes mellitus, and the US Food and Drug Administration approved the first agent (sitagliptin) of this class in 2006. It has also been reported that intervention of DPP‐4 inhibitors is also linked with an increase of incretins (GLP‐1), thereby leading to improvement in glucose tolerance and increased insulin secretion.35 However, gliptins have been reported to have adverse side effects, including nausea, diarrhea and stomach pain, headache, runny nose, sore throat, and painful skin followed by a red or purple rash. Furthermore, in 2015, the US Food and Drug Administration issued a new warning and precaution, suggesting the carrying of labels such as 'severe and disabling' joint pain not only for sitagliptin, but also for other gliptins, such as saxagliptin, linagliptin, and alogliptin. Thus, it is imperative to search for a new DPP‐4 inhibitor from natural source which has been used as safe remedy for the treatment of various illnesses including diabetes. Hence, amla extract could provide an alternative option to help manage glucose tolerance and increase insulin secretion via increasing incretins (GLP‐1) level.

There has been substantial scientific evidence suggesting the pivotal roles of ROS and other oxidants in causing numerous disorders and diseases.36 These partially reduced metabolites of nitrogen and oxygen, termed free radicals, are reported to be highly toxic and reactive.37 The human body has mechanisms to fight against these free radicals. However, the excess generation of free radicals and/or the body's inability to fight against these free radicals has been linked with several acute and chronic disorders, including diabetes, neurodegeneration, immunosuppression, atherosclerosis, and aging.38 Chronic diabetes and hyperglycemia induce the generation of ROS, which can increase insulin resistance and lead to the aggravation of type 2 diabetes.39 Our study reports the protection against cellular ROS by AFE. It has been well established that plants, vegetables, and fruits exhibit antioxidant potential against these free radicals due to the presence of bioactive molecules such as phenolics, tannins, proanthocyanidins, and flavonoids. Likewise, the antioxidant activity of AFE could also be attributed to the presence of bio‐actives such as BGG along with hydrolyzable tannins.

In order to evaluate various commercial applications, it is important for a standardized preparation of plant extract to exert the biological function when subjected to extreme temperature in aqueous solution. It has been reported that BGG is unstable in aqueous solutions.40 On examining further, it was noted that the aqueous stability of BGG was measured by Li et al.40 at a very low pH of 0.33 at 80 °C, at which most esters will eventually hydrolyze let alone a water‐soluble BGG. Also, the urinary half‐life of 31 h further pointed to the stability of BGG in the mammalian system.34 By keeping these features in mind, we evaluated AFE for its thermostability in aqueous solution and also pH stability in acidic and alkaline media along with 36 months storage stability at 30 ± 2 °C with relative humidity of 65 ± 5%. The results of our study demonstrated that AFE was significantly stable at 90 °C for 30 min. Further, the thermostability of AFE was time and temperature dependent. This information could be vital for formulators using AFE in beverage formulations as a functional drink providing antidiabetic effects. It is also important that such beverages must exert the antidiabetic activity after extreme gastric pH treatments when ingested. We report the gastric stability at pH 1.5 after 120 min of treatment. It was found to be fairly stable at various pH treatments but had reduced antidiabetic activity at extremely alkaline pH ranges (9.0 to 10.0) after 90 min. It was also noted that BGG was found to be stable without impacting its functionality (anti‐amylase activity potential) at 30 ± 2 °C when stored for 36 months, thereby suggesting shelf stability of AFE at ambient temperature. The pH, thermostability, and long‐term storage stability of AFE provide practical advantages for formulation in various foods and beverages wherein a high temperature and extreme pH may be involved during the manufacturing processes.

CONCLUSIONS

This study demonstrates for the first time that AFE standardized to contain BGG along with hydrolyzable tannins possesses potent antidiabetic activity via inhibiting the activity of porcine pancreatic α‐amylase, human salivary α‐amylase, α‐glucosidase, and DPP‐4 enzyme. Further, it also exhibited antioxidant activities through free radical scavenging activity using DPPH radical scavenging and ROS inhibition assay. Although further in vivo study may be needed, the data presented in this study clearly provide the evidence of the effectiveness of AFE containing BGG along with hydrolyzable tannins as biomarkers in the management of hyperglycemia.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

This study was supported by the Sami Labs Limited/Sabinsa Corporation. The authors are employees of Sabinsa Corporation/Sami Labs Limited, manufacturer and marketer of Saberry® (AFE). The funder did not have any additional role in the study design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Ethics approval was not required for this study as the study did not involve humans or animals.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author(s) also recognize the following intellectual property rights for ingredients used in the current study: Saberry® is a registered US trademark of Sabinsa Corporation. Data described in the current study partly form the basis for patent applications (US 15971069 and PCT/US18/31037).

REFERENCES

- 1. Hockaday TDR, Hockaday JM, Mann JI and Turner RC, Prospective comparison of modified fat‐high‐carbohydrate with standard low‐carbohydrate dietary advice in the treatment of diabetes: one year follow‐up study. Br J Nutr 39:357–362 (1978). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jung CH and Choi KM, Impact of high‐carbohydrate diet on metabolic parameters in patients with type 2 diabetes. Nutrients 9:322 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Martinez‐Gonzalez AI, Díaz‐Sánchez ÁG, Rosa LA, Vargas‐Requena CL, Bustos‐Jaimes I and Alvarez‐Parrilla AE, Polyphenolic compounds and digestive enzymes: in vitro non‐covalent interactions. Molecules 22:E669 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ramya AS, Uppala D, Majumdar S, Surekha CH and Deepak KG, Are salivary amylase and pH – prognostic indicators of cancers? J Oral Biol Craniofac Res 5:81–85 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lovegrove A, Edwards CH, De Noni I, Patel H, El SN, Grassby T et al, Role of polysaccharides in food, digestion, and health. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 57:237–253 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kumar S, Narwal S, Kumar V and Prakash O, α‐Glucosidase inhibitors from plants: a natural approach to treat diabetes. Pharmacogn Rev 5:19–29 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. den Besten G, van Eunen K, Groen AK, Venema K, Reijngoud DJ and Bakker BM, The role of short‐chain fatty acids in the interplay between diet, gut microbiota, and host energy metabolism. J Lipid Res 54:2325–2340 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Radulian G, Rusu E, Dragomir A and Posea M, Metabolic effects of low glycaemic index diets. Nutr J 29:5 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sears B and Perry M, The role of fatty acids in insulin resistance. Lipids Health Dis 14:121 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wilcox G, Insulin and insulin resistance. Clin Biochem Rev 26:19–39 (2005). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bailes BK, Diabetes mellitus and its chronic complications. AORN J 76:266–276, 278–282. quiz 283–286 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Williamson G, Possible effects of dietary polyphenols on sugar absorption and digestion. Mol Nutr Food Res 57:48–57 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Seino Y and Yabe D, Glucose‐dependent insulinotropic polypeptide and glucagon‐like peptide‐1: incretin actions beyond the pancreas. J Diabetes Invest 4:108–130 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Deacon CF and Ahrén B, Physiology of incretins in health and disease. Rev Diabet Stud 8:293–306 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pathak R and Bridgeman MB, Dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 (DPP‐4) inhibitors in the management of diabetes. Pharm Ther 35:509–513 (2010). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Avogaro A and Fadini GP, The effects of dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 inhibition on microvascular diabetes complications. Diabetes Care 37:2884–2894 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Patel SS and Goyal RK, Emblica officinalis Geart: a comprehensive review on phytochemistry, pharmacology and ethnomedicinal uses. Res J Med Plant 6:6–16 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 18. Krishnaveni M and Mirunalini S, Therapeutic potential of Phyllanthus emblica (amla): the Ayurvedic wonder. J Basic Clin Physiol Pharmacol 21:93–105 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yang B and Liu P, Composition and biological activities of hydrolyzable tannins of fruits of Phyllanthus emblica . J Agric Food Chem 62:529–541 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Majeed M, Bhat B, Jadhav AN, Srivastava JS and Nagabhushanam K, Ascorbic acid and tannins from Emblica officinalis Gaertn. fruits – a revisit. J Agric Food Chem 57:220–225 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Okolo BN, Ezeogu LI and Mba CN, Production of raw starch digesting amylase by Aspergillus niger grown on native starch sources. J Sci Food Agric 69:109–115 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gowri PM, Tiwari AK, Ali AZ and Rao JM, Inhibition of α‐glucosidase and amylase by bartogenic acid isolated from Barringtonia racemosa Roxb. seeds. Phytother Res 21:796–799 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Christopherson KW, Cooper S and Broxmeyer HE, Cell surface peptidase CD26/DPPIV mediates G‐CSF mobilization of mouse progenitor cells. Blood 101:4680–4686 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kojima K, Hama T, Kato T and Nagatsu T, Rapid chromatographic purification of dipeptidyl peptidase IV in human submaxillary gland. J Chromatogr 189:233–240 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Majeed M, Majeed S, Nagabhushanam K, Arumugam S, Beede K and Ali F, Evaluation of probiotic Bacillus coagulans MTCC 5856 viability after tea and coffee brewing and its growth in GIT hostile environment. Food Res Int 121:497–505 (2019). 10.1016/j.foodres.2018.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. LeBel CP, Ischiropoulos H and Bondy SC, Evaluation of the probe 2′,7′‐dichlorofluorescin as an indicator of reactive oxygen species formation and oxidative stress. Chem Res Toxicol 5(2), 227–231(1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Majeed M, Majeed S, Nagabhushanam K, Arumugam S, Natarajan S, Beede K et al, Galactomannan from Trigonella foenum‐graecum L. seed: prebiotic application and its fermentation by the probiotic Bacillus coagulans strain MTCC 5856. Food Sci Nutr 6:666–673 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.ICH Expert Working Group. Stability testing of new drug substances and products Q1A(R2). Geneva, Switzerland. ICH, 2003. https://database.ich.org/sites/default/files/Q1A_R2_Guideline.pdf.

- 29. Majeed M, Bhat B and Anand TSS, Inhibition of UV induced adversaries by β‐glucogallin from amla (Emblica officinalis Gaertn.) fruits. Indian J Nat Prod Resour 1:462–465 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 30. Blaak EE, Antoine JM, Benton D, Björck I, Bozzetto L, Brouns F et al, Impact of postprandial glycaemia on health and prevention of disease. Obes Rev 13:923–984 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Olennikov DN, Kashchenko NI, Schwabl H, Vennos C and Loepfe C, New mucic acid gallates from Phyllanthus emblica . Chem Nat Compd 51:666–670 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 32. Puppala M, Ponder J, Suryanarayana P, Reddy GB, Petrash JM and LaBarbera DV, The isolation and characterization of β‐glucogallin as a novel aldose reductase inhibitor from Emblica officinalis . PLoS One 7:e31399 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chang KC, Laffin B, Ponder J, Enzsöly A, Németh J, LaBarbera DV et al, Beta‐glucogallin reduces the expression of lipopolysaccharide‐induced inflammatory markers by inhibition of aldose reductase in murine macrophages and ocular tissues. Chem Biol Interact 202:283–287 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Takemoto JK and Davies NM, Method development for β‐glucogallin and gallic acid analysis: application to urinary pharmacokinetic studies. J Pharm Biomed Anal 54:812–816 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Garber AJ, Incretin therapy – present and future. Rev Diabet Stud 8:307–322 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Uttara B, Singh AV, Zamboni PV and Mahajan RT, Oxidative stress and neurodegenerative diseases: a review of upstream and downstream antioxidant therapeutic options. Curr Neuropharmacol 7:65–74 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lobo V, Patil A, Phatak A and Chandra N, Free radicals, antioxidants and functional foods: impact on human health. Pharmacogn Rev 4:118–126 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pham‐Huy LA, He H and Pham‐Huy C, Free radicals, antioxidants in disease and health. Int J Biomed Sci 4:89–96 (2008). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kaneto H, Katakami N, Matsuhisa M and Matsuok TA, Role of reactive oxygen species in the progression of type 2 diabetes and atherosclerosis. Mediators Inflamm:453892 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Li L, Kun‐Che C, Yaming Z, Shieh B, Ponder J, Adedoyin D et al, Design of an amide N‐glycoside derivative of β‐glucogallin: a stable, potent, and specific inhibitor of aldose reductase. J Med Chem 57:71–77 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]