Waterborne human viruses can persist in the environment, causing a risk to human health over long periods of time. In this work, we demonstrate that in both freshwater and seawater environments, indigenous bacteria and protists can graze on waterborne viruses and thereby reduce their persistence. We furthermore demonstrate that the efficiency of the grazing process depends on temperature, virus type, and protist species. These findings may facilitate the design of biological methods for the disinfection of water and wastewater.

KEYWORDS: grazing, predation, waterborne viruses, enterovirus, microbial inactivation, water treatment, virus predation, microbial virus control, waterborne pathogen

ABSTRACT

Human viruses are ubiquitous contaminants in surface waters, where they can persist over extended periods of time. Among the factors governing their environmental persistence, the control (removal or inactivation) by microorganisms remains poorly understood. Here, we determined the contribution of indigenous bacteria and protists to the decay of human viruses in surface waters. Incubation of echovirus 11 (E11) in freshwater from Lake Geneva and seawater from the Mediterranean Sea led to a 2.5-log10 reduction in the infectious virus concentration within 48 h at 22°C, whereas E11 was stable in sterile controls. The observed virus reduction was attributed to the action of both bacteria and protists in the biologically active matrices. The effect of microorganisms on viruses was temperature dependent, with a complete inhibition of microbial virus control in lake water at temperatures of ≤16°C. Among three protist isolates tested (Paraphysomonas sp., Uronema marinum, and Caecitellus paraparvulus), Caecitellus paraparvulus was particularly efficient at controlling E11 (2.1-log10 reduction over 4 days with an initial protist concentration of 103 cells ml−1). In addition, other viruses (human adenovirus type 2 and bacteriophage H6) exhibited different grazing kinetics than E11, indicating that the efficacy of antiviral action also depended on the type of virus. In conclusion, indigenous bacteria and protists in lake water and seawater can modulate the persistence of E11. These results pave the way for further research to understand how microorganisms control human viral pathogens in aquatic ecosystems and to exploit this process as a treatment solution to enhance microbial water safety.

IMPORTANCE Waterborne human viruses can persist in the environment, causing a risk to human health over long periods of time. In this work, we demonstrate that in both freshwater and seawater environments, indigenous bacteria and protists can graze on waterborne viruses and thereby reduce their persistence. We furthermore demonstrate that the efficiency of the grazing process depends on temperature, virus type, and protist species. These findings may facilitate the design of biological methods for the disinfection of water and wastewater.

INTRODUCTION

Human enteric viruses are introduced into aquatic environments by raw or treated sewage and pose a risk to human health. Exposure to contaminated recreational water, drinking water, or food crops can lead to human infection and the transmission of viral pathogens among susceptible populations. Enteric viruses have been found in source waters used for drinking water production, such as surface waters or groundwater (1). For example, Lodder and Husman (2) detected norovirus in surface waters in the Netherlands at concentrations where even if only 1% of the viral particles were infectious, it would still present an important risk of waterborne gastroenteritis outbreak. The risk posed by waterborne viruses is compounded by their high environmental persistence. For example, Yates et al. (3) showed that poliovirus 1 and echovirus 1 (E1) infectivity levels remained constant up to 28.8 days in natural waters.

In the aqueous environment, the persistence of human viruses can depend on many parameters, including temperature, exposure to sunlight, water type (fresh, estuarine, or marine), and the type of virus (4). While these abiotic parameters have been well investigated, knowledge gaps remain in our understanding of the effect of indigenous bacteria or protists on viral pathogens (5). Several studies have demonstrated that bacteria can exert antiviral action. For example, Cliver and Herrmann (6) inoculated different bacteria into filter-sterilized lake water (LW) samples and found that various bacterial species can inactivate some, but not all, species of enterovirus by producing proteolytic enzymes that hydrolyze the virus coat proteins. Antiviral action of bacteria was also demonstrated by Ward et al. (7), who showed that bacterial isolates obtained from a stream caused the decay of human enteroviruses.

The persistence of viruses is also modified through grazing by protists (8, 9). Species like Tetrahymena, heterotrophic nanoflagellates, and amoeba can control viruses by ingesting free viral particles (8, 10). In a study by Deng et al. (11), MS2 bacteriophage, which is often considered a surrogate for human enteric virus, was used to study microbial grazing of enteric viruses. When MS2 was incubated alone, no more than a 1-log10 reduction in the infectious virus concentration was observed over 3 months, while when MS2 was incubated with bacteria, a reduction of roughly 2.5 log10 was attained. When incubated with bacteria and the ciliate Tetrahymena coloniensis, the reduction was even greater and reached 7 log10 in 3 months. Gonzalez and Suttle (9) studied the uptake of marine viruses and bacteria by nanoflagellate protists. The authors reported ingestion rates ranging from 0.022 to 0.054 viral particles protist cell−1 min−1. Even though protist grazing rates were lower than those of bacteria, this study showed that natural assemblages of seawater (SW) protists were able to ingest and digest marine viral particles. It has also been shown that adenovirus type 3 (12) and poliovirus (13) can be inactivated by the ciliate Tetrahymena pyriformis, a filter-feeder protist often present in freshwater. However, not all protists or bacterial species inactivate viruses (6), and some protists can even act as reservoirs of viruses. For example, Acanthamoeba castellanii can internalize surrogates of human norovirus, which could enhance the transport of the virus through the environment and make it more persistent (14).

Thus, microorganisms can play important roles in the control of viruses in surface waters, but the associated processes are complex and are not fully characterized. In particular, the contribution of protists to viral decay in natural waters is only poorly understood. A better understanding of microbial disinfection in aquatic ecosystems is required to assess the persistence of viral pathogens in the environment and could eventually lead to engineered solutions for controlling human pathogens during (waste)water treatment or shell fish production. Such a biological approach, as an alternative or a complement to established physicochemical treatment processes like UV or chlorine disinfection, would minimize the use of chemicals, reduce the production of by-products, and, thus, limit the impacts of water treatment on human health and ecosystem pollution.

Here, we investigated the microbial control of a frequently encountered waterborne viral pathogen (echovirus 11) in different freshwater and marine waters. Hereafter, the term “control” refers to the decay in infectious virus concentrations in the water column, which may arise from both the physical removal of suspended viruses (e.g., by internalization) as well as their inactivation by antiviral agents. Specifically, we determined the roles of bacterial and eukaryotic populations in the observed virus decay, and we assessed the effects of temperature, water type, protist species, and virus type. Our results inform on the relative contribution of microbial action to virus decay in surface waters and identify parameters influencing microbial virus control.

RESULTS

Evidence of microbial virus control in different surface water samples.

In order to test if microbial virus control occurs in water from Lake Geneva, the decay of E11 in different batches of full LW was compared to that in the corresponding filter-sterilized LW. As is evident from Fig. 1, virus decay in full LW was always greater than that in the corresponding sterile control. At each time point, the mean decay in full LW was significantly greater than that in sterile LW (average of biological replicates, one-sided t test; P = 0.03 at 24 h; P = 0.003 at 48 h; P = 0.0008 at 72 h). The decay in full LW was also significantly faster than that in autoclaved full LW (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material), indicating that sorption to particles is not a major mechanism (average of biological triplicates, one-sided t test; P = 0.02 at 96 h). In LW, k corresponded to 0.13 ± 0.02 h−1 (R2 = 0.79) for full LW and to 0.03 ± 0.02 h−1 (R2 = 0.35) for sterile LW. Similar findings were obtained for SW (Mediterranean seawater [MSW]) (Fig. 1b), with k values of 0.09 ± 0.02 h−1 (R2 = 0.93) for MSW and 0.02 ± 0.02 h−1 (R2 = 0.37) for sterile MSW.

FIG 1.

Decay of E11 during incubation at room temperature in sterile or full lake water (a) or sterile or full seawater (b). Experiments with lake water were conducted in duplicate or triplicate (except at 72 h), using different batches of water taken from Lake Geneva. Experiments in seawater were conducted once, using a single batch of water from the Mediterranean Sea. Arrows indicate samples with infectious virus concentrations below the limit of detection.

Contribution of different microbial fractions to E11 decay.

To identify the main microorganism type leading to the control of E11, experiments were conducted using the bacterial and eukaryotic fractions obtained from LW and Atlantic Ocean seawater (ASW), along with corresponding sterile controls (Fig. 2). The decay kinetics were similar in the eukaryotic (k = 0.08 ± 0.02 h−1; R2 = 0.92) and bacterial (k = 0.07 ± 0.01 h−1; R2 = 0.82) LW fractions and were faster than those in the sterile LW (k = 0.02 ± 0.01 h−1; R2 = 0.62) (Fig. 2a). In ASW (Fig. 2b), virus decay in the eukaryotic fraction (k = 0.14 ± 0.02 h−1; R2 = 0.86) was more rapid than that in the bacterial (k = 0.07 ± 0.01 h−1; R2 = 0.84) and sterile fractions (k = 0.05 ± 0.02 h−1; R2 = 0.94).

FIG 2.

(a) Decay of E11 in the bacterial lake water fraction (with 5 × 106 bacterial cells ml−1 at t0) and the eukaryotic lake water fraction (with 6 × 104 protist cells ml−1 and 1 × 106 bacterial cells ml−1 at t0). Sterile lake water was used as a negative control. (b) Decay of E11 in the bacterial seawater fraction, the eukaryotic seawater fraction, and sterile seawater from the Atlantic Ocean. The concentrations of bacterial and eukaryotic cells in seawater were not measured. All experiments were conducted in duplicate at room temperature.

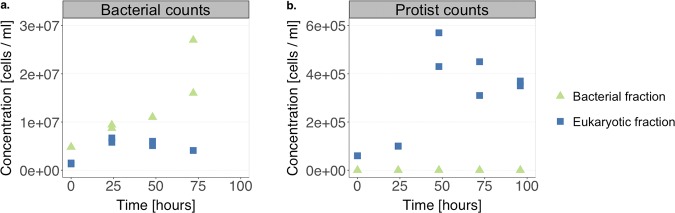

In addition to virus decay, we also monitored the change in the concentrations of protists and bacteria in both the bacterial and eukaryotic fractions of LW over the course of the experiment (Fig. 3). Bacterial cells were present in both the bacterial and the eukaryotic fractions, indicating that the 0.8-μm filter used to separate out the eukaryotic fraction (Fig. S1) retained a portion of the bacteria in the sample. In the bacterial fraction, the initial bacterial concentration was 5 × 106 bacterial cells ml−1, whereas in the eukaryotic fraction it was 1 × 106 bacterial cells ml−1. The initial protist concentration in the eukaryotic fraction was about 6 × 104 protist cells ml−1, whereas no protists were found in the bacterial fractions. Both protist and bacterial concentrations increased during the experiment, although the total increase remained below 1 log10 (Fig. 3).

FIG 3.

Evolution of the bacterial concentration (a) and the protist concentration (b) in the bacterial fraction and in the eukaryotic fraction of lake water during the E11 decay experiment shown in Fig. 2a.

In order to distinguish the effects of protist versus bacterial grazing in the eukaryotic LW fraction (Fig. 2a), we first estimated the contribution of bacteria to E11 decay. To this end, we estimated the clearance rate per bacterial cell, k′, based on the bacterial LW fraction, according to equation 2. The k′ in the bacterial fraction was 6 × 10−9 ml cell−1 h−1 (Fig. S3a). Because the bacteria in both the bacterial and eukaryotic fractions stem from the same water sample, we assumed that this k′ also applies to the viral grazing by bacteria contained in the eukaryotic fraction. Using equation 2 and the measured bacterial concentrations in the eukaryotic fraction (Fig. 3b), we then could estimate the virus decay in the eukaryotic fraction that is attributable to the action of bacteria (Fig. S3b). It was evident that the contribution of bacteria does not fully account for the extent of virus decay observed in the eukaryotic fraction. This suggests that other microorganisms, such as protists, contribute to virus control in the eukaryotic fraction. Thus, using the measured protist concentrations in the eukaryotic fraction (Fig. 3b) and correcting for the contribution of bacteria, we then estimated the clearance rate per protist cell, which corresponded to 9 × 10−8 ml cell−1 h−1.

Temperature dependence of microbial control of E11.

Environmental virus persistence is known to vary with environmental conditions, particularly temperature (4). To assess the effect of temperature on microbial virus control, we compared levels of E11 decay at five different temperatures (4°C, 8°C, 16°C, 22°C, and 30°C) in the eukaryotic LW fraction (containing 103 protist cells ml−1 at t0). To differentiate between abiotic and biotic processes, decay experiments were also conducted in sterile LW. At 4°C, 8°C, and 16°C, the infectious E11 concentration remained stable in both biologically active and sterile LW over the time scale considered (Fig. 4a). At these low temperatures, E11 was affected by neither microbial action nor any abiotic processes (e.g., adsorption to particles) over the time scale of the experiment. At 22°C, a 2-log10 E11 decay was observed in the eukaryotic fraction, while no decay was observed in the sterile LW. Thus, at 22°C the microorganisms contained in the eukaryotic fraction were sufficiently active to cause E11 decay, whereas thermal inactivation alone did not lead to measurable decay over the time scale considered. At 30°C, E11 decay in sterile LW sample was comparable to that in the eukaryotic LW fraction. The mechanism for the infectivity loss of E11 in sterile LW is currently unknown, but it cannot be attributed to thermal inactivation, as additional control experiments performed at 30°C in PBS and SW yielded no inactivation over the time scale considered (data not shown). In ASW and MSW, the biologically active, eukaryotic fraction (containing 103 protist cells ml−1 at t0) yielded a 2-log10 decay over 48 h at 30°C, whereas no decay was observed at 4°C (Fig. 4b).

FIG 4.

(a) Decay of infectious E11 after 48 h of incubation at different temperatures in sterile lake water or in the eukaryotic fraction of Lake Geneva water (containing 103 protist cells ml−1 at t0). Experiments were conducted in duplicate or triplicate. (b) Decay of infectious E11 after 48 h of incubation with the eukaryotic fractions (containing 103 protist cells ml−1 at t0) of Lake Geneva (LW), the Mediterranean Sea (MSW), or the Atlantic Ocean (ASW). Experiments were conducted in duplicate or triplicate at 4°C and 30°C.

Grazing of E11 by different protist isolates.

To confirm that protists in our water matrices can indeed contribute to virus control, three species of marine protists were isolated from MSW and ASW samples and were tested for their ability to exert virus control. These species were identified as Paraphysomonas species, Uronema marinum, and Caecitellus paraparvulus. Paraphysomonas species are flagellate protists found in freshwater, soils, and marine environments (15–17), Uronema marinum is a marine ciliate (15), and Caecitellus paraparvulus is a heterotrophic flagellate mostly found in marine environments (15, 18, 19). Figure 5 shows the decay of E11 induced by each of these protists when incubated at room temperature at an initial protist density between 103 and 104 cells ml−1. Caecitellus paraparvulus and Paraphysomonas sp. were efficient at grazing E11 (>2-log10 reduction over 4 days), but Uronema marinum had no effect on the viral titer.

FIG 5.

Grazing of E11 by Uronema marinum, Caecitellus paraparvulus, and Paraphysomonas sp. Initial protist density ranged from 103 to 104 cells ml−1. Experiments were conducted at room temperature in sterile seawater from the Atlantic Ocean.

Susceptibility of different viruses to control by microorganisms.

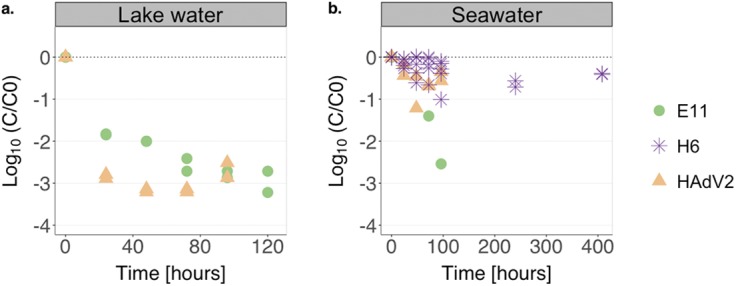

Different viruses are known to vary in their susceptibilities to physical and chemical inactivation processes (20–23). To determine if these differences also exist for microbial virus control, we compared the decay kinetics of HAdV2, E11, and H6 in the eukaryotic fractions of LW or SW (Fig. 6). In the eukaryotic LW fraction, the infectious HAdV2 concentration decreased by 2.8-log10 during the first 24 h but then remained relatively constant over the time scale considered (100 h) (Fig. 6a). On the contrary, E11 exhibited a decay of 1.8 log10 during the first 24 h, followed by a slower decrease in infectious titer up to 120 h. These results are similar to what was observed for SW (Fig. 6b), which also exhibited stable HAdV2 titers after 24 h, whereas E11 titers continued to decrease over the course of the experiment (96 h). Interestingly, the titer of the phage H6 incubated in the SW eukaryotic fraction remained stable over a period of 1 month (Fig. 6b).

FIG 6.

(a) Decay of E11 and HAdV2 upon incubation with the eukaryotic fraction of from Lake Geneva (protist concentration at time t0, 103 cells ml−1). Experiments were conducted in duplicate. (b) Decay of E11, HAdV2, and bacteriophage H6 upon incubation with the eukaryotic fraction isolated from the Atlantic Ocean (protist concentration at time t0, 103 cells ml−1). Data points represent a single replicate for E11, five replicates for H6 (from 0 h to 96 h), and two replicates for HAdV2.

DISCUSSION

Bacteria and protists both contribute to virus control.

Exposure of E11 to microbially active freshwater and seawater samples led to a significant reduction in infectious viruses over time (Fig. 1 and 2). Thus, the different water matrices tested contained biologically active constituents that either physically removed or inactivated viruses. This finding is consistent with the results of Ward et al. (7), who determined that the decay of poliovirus in fresh water samples was tightly linked with the presence of microorganisms. These authors demonstrated a reduction in infectious poliovirus type 1, coxsackievirus B5, rotavirus strain SA-11, and echovirus type 12 (E12) in four different freshwater sources but not in sterile distilled water. Specifically, after 2 days of incubation at 27°C, a 2.8-log10 decrease of E12 was observed in river water and a 5-log10 decrease was obtained in water from a creek. Thus, the decay of E11 in Lake Geneva water observed here (2.5-log10 decrease after 2 days) is comparable to that reported by Ward et al. for E12 in river water (7).

Both the bacterial and eukaryotic fractions of the waters tested caused E11 decay (Fig. 2). This confirms that bacteria alone can exert antiviral activity on E11. However, other microorganisms also contribute to the control of E11. This was evident from experiments in the eukaryotic fraction of Lake Geneva, where virus decay was at least as efficient as that in the bacterial fraction, even though fewer bacteria were present (Fig. 3). Besides bacteria, the eukaryotic fraction may include protists, algae, and fungi. Algae are not expected to contribute to virus control (24), and no literature reports were found on the effect of fungi on waterborne viruses. Thus, protists are the most likely contributors to microbial virus control in the eukaryotic fraction. This assumption was supported by the finding that at least two protist species isolated from the water matrices used here were capable of inducing E11 decay (Fig. 5).

Our results suggest a role of both protists and bacteria in microbial virus control. The calculated clearance rate of protists was 1 order of magnitude larger than that of bacteria. Because this work was conducted in complex natural samples, however, there are limitations to assessing their relative contributions. First, as discussed by Rose et al. (25), it is challenging to accurately monitor the changes in bacterial and protist populations in complex matrices such as the eukaryotic water fractions. In particular, the bacterial concentration in the eukaryotic fraction was likely overestimated. Second, we did not consider species variability in our sample. While each bacterial or protist population was composed of an assemblage of diverse species, all organisms were considered to have the same effect on viruses. However, the effect of bacteria and protists on viruses is in fact species dependent (6, 13). For example, Cliver and Herrmann (6) highlighted that not all bacterial species excrete proteolytic enzymes capable of degrading viruses, and our results suggested that different species of protists affect viruses to different extents (Fig. 5). Finally, while this study used natural water samples, the samples were maintained and cultured under laboratory conditions over the course of this study. It is likely that the environmental parameters encountered in the laboratory (e.g., temperature, light regime) altered the composition of the microbial communities compared to their natural state.

The contribution of microorganisms to virus decay depends on temperature.

At temperatures of 16°C or lower, no decay of E11 was observed in the eukaryotic fractions of any of the waters tested, which suggests that microbial activity was inhibited by cold temperature (Fig. 4). This implies that in winter or in cold environments, the contribution of microorganisms to virus decay is minimal. However, all microcosms used in this study were maintained at room temperature, even if sampled from lower temperatures. We therefore cannot exclude the possibility that microorganisms adapted to, and maintained at, lower temperatures exhibit antiviral activity even at temperatures of <16°C. At higher temperatures viral persistence was found to be modulated by microbial action. Specifically, in LW at 22°C, microbial control dominated over abiotic virus inactivation or removal. In SW, the contribution of microorganisms to E11 decay also dominated at 30°C, while in LW abiotic processes were also relevant.

Similar findings were reported by Ward et al. (7), who determined that the decay of E12 and rotavirus SA-11 in freshwater samples was temperature dependent. Specifically, no decay of E12 was measured after 2 days of incubation at 4°C, while a 3-log10 decay was obtained at 29°C. Although the study by Ward et al. considered freshwater samples rather than just the eukaryotic fraction studied here, their results are similar to findings in this study.

Antiviral action is similar across microbial populations from different water types.

The eukaryotic fractions from Lake Geneva and from the Atlantic Ocean, when adjusted to the same initial protist concentration, led to a similar E11 decay of about 2.6 log10 over 4 days (Fig. 6). In addition, the temperature sensitivity of the eukaryotic fraction was similar for all waters tested (Fig. 4). Thus, as long as the concentration of protists is similar, comparable antiviral effects on E11 were observed for the water types included in this study, even if they were obtained from different geographical locations. However, it should be considered that our sample size was small, and that the different microbial populations may have adapted to laboratory conditions. To confirm these findings, inclusion of additional water sources (rivers and estuaries) under different climates and over various seasons is needed.

Protist-mediated decay rates depend on both protist and viral species.

If studied in isolation rather than as environmental assemblages, different protist species affected E11 to different extents. Caecitellus paraparvulus and Paraphysomonas sp. could inactivate E11, while Uronema marinum had no effect on the timescale considered (Fig. 5). The grazing rate of protists may depend on their feeding behavior. Kim and Unno (13) reported that filter feeders like Tetrahymena sp. ciliates were more efficient at removing viruses than detritus-feeding microbes (13). Likewise, Deng et al. (11) reported that the feeding behavior of heterotrophic nanoflagellates drives their viral grazing efficiency, and that filter-feeding flagellates were more efficient than raptorial grazers. This trend was not confirmed in this study. Caecitellus paraparvulus species graze using an ingestion mechanism referred to as a “feeding basket,” which is composed of microtubules (18). The literature reports that Caecitellus protists behave like deposit feeders (26), using their flagella to collect food from surfaces. Paraphysomonas species exclusively graze on free bacteria and very little on attached bacteria (27). This suggests that Paraphysomonas protists behave like filter feeders. Finally, it has been reported that, like Paraphysomonas sp., Uronema marinum efficiently feeds on suspended bacteria (26). Specifically, Uronema can either create water currents to collect food or filter the surrounding water using their cilia. These protists are also considered filter feeders (26). Thus, the feeding behavior alone cannot explain the differences in virus grazing observed here, since the filter feeder Paraphysomonas and the deposit feeder Caecitellus protists led to E11 titer reduction while the filter feeder Uronema marinum did not. Instead, other determinants, such as the size ratio between predator and prey, may play a role in the grazing efficiency (28).

Virus decay rates not only varied with protist species but also depended on the virus type. For a given assemblage of microorganisms different viruses were inactivated at different rates (Fig. 6). Similar findings were reported for single protist species, which were found to exert vastly different effects on different viruses. For example, studies on fish viruses and bacteriophages have shown that ciliates could inactivate viral hemorrhagic septicemia virus (29) and bacteriophage T4 (10), but they internalized and then released chum salmon reovirus and bacteriophage phiX174 in an infective state (30, 31). Thus, our results suggest that, like for fish viruses or bacteriophages, not all human viruses are equally susceptible to protists. The properties that render a virus susceptible to microbial control are not understood. A likely determinant, however, is the size ratio between the protist and its prey (28). The two human viruses studied here spanned a size range of 30 nm (E11 [32]) to 90 nm (HAdV2 [33]) in diameter. It is probable that additional human viruses within this size range exhibit susceptibility to grazing similar to that of E11 and HAdV2. This suggestion, however, remains to be experimentally confirmed prior to generalizing our findings across the diverse population of waterborne viruses.

Interestingly, bacteriophage H6 was more resistant to microbial control than human viruses. While the size of this virus is unknown, adaptation to grazing by indigenous microbial populations may lead to greater resistance toward microbial virus control compared to contaminant viruses.

Contribution of microbial control to total virus decay in natural waters.

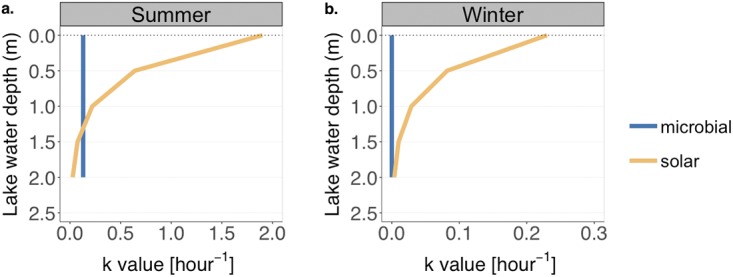

In the environment, solar UV light and temperature are important known stressors for enteric viruses (4). Their relative contributions to virus decay in a water body depend on the temperature profile and optical properties of the water column, which vary seasonally. To assess the relative contribution of microorganisms to virus decay, we compared the decay rates measured here (which inherently include thermal inactivation) with those previously studied for solar inactivation (20).

Solar inactivation rate constants were modeled at different depths (0 to 2 m) and different seasons (summer and winter) and were compared to the microbial decay rate constant (Fig. 7). Here, it was assumed that the composition of the microbial population in the first 2 m of the water column was similar to that of the samples used in this study. This is reasonable, since our samples were taken in the first meters of the water column, which is a well-mixed layer. Furthermore, the temperature dependency of microbial grazing observed in the eukaryotic fraction also applied to full LW.

FIG 7.

Estimated rate constants for solar inactivation and microbially induced decay of E11 in the top 2 m of the water column of Lake Geneva on a summer day (a) and on a winter day (b). Note the difference in scale on the x axis between the two plots.

In summer and at the lake surface (z0), solar inactivation (ksolar, summer, z0 = 1.9 h−1) was 10 times faster than microbial decay (kmicrobial, summer = 1.3 × 10−1 h−1 at 22°C; see Results). However, as depth increased, solar inactivation decreased due to the attenuation of UVB radiation by the water column; thus, microbial decay predominated over sunlight inactivation at depths below 1.3 m. In winter and at the lake surface (0 to 2 m below the surface), the solar inactivation rate constant, ksolar, winter, ranged from 2.3 × 10−1 to 3.7 × 10−3 h−1. However, it remained higher than microbial decay, which was inhibited by the low water temperature (6°C throughout the whole water column [34]).

These estimates indicate that in winter the antiviral role of microorganisms is small, regardless of the depth, whereas in summer, microbial action may play a major role in viral decay below the photic zone. These findings, however, remain to be confirmed in environmental systems, where additional parameters not considered here may play a role. Such parameters include the nutritional state of the indigenous bacteria and protists, the potential temperature adaptation of microorganisms, and the variability in the microbial abundance and diversity throughout the water column.

Conclusions.

This study demonstrates that microbial activity leads to inactivation or physical removal of human viruses in freshwater and seawater. Control by microorganisms is likely to modulate virus persistence in warm temperatures, in particular below the photic zone, where viruses are shielded from solar inactivation. In contrast, under the batch conditions studied, microorganisms exerted little virucidal effect under cold conditions. Not only indigenous bacteria but also protists contributed to virus control, and decay rates differed for different virus types. Decay rates, furthermore, depended on the protist species if studied in isolation, but the different microbial assemblages studied exhibited similar virucidal activity. This suggests that microbial control of viruses is a robust process that can be exploited for water and wastewater treatment applications. In future work, these findings should be confirmed under field conditions, for example, by suspending viruses contained in dialysis chambers in surface waters. Such an experimental setup will avoid any adaptation of the local microcosm to laboratory conditions and will better represent fluctuations in environmental parameters.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Water samples.

Coastal seawater (SW) samples (two liters per sample) were collected from the surface layer (<2 m) of the Atlantic Ocean (ASW; Lanzarote, Spain; January 2017; water temperature of 21°C) and the Mediterranean Sea (MSW; Palamós, Spain; December 2016; water temperature of 10°C). Lake water (LW) samples (four liters per sample) were collected from Lake Geneva (St-Sulpice, Switzerland; February to April 2018; water temperature ranged between 5°C and 10°C). After collection, seawater samples were stored up to 1 week at 4°C prior to use in experiments. Lake water samples were stored at 4°C for 1 to 2 days before use.

Isolation of microbial fractions.

To isolate different microbial fractions from the samples, one liter of water was prefiltered through a 8-μm-pore-size nitrocellulose filter (Millipore, Sigma-Aldrich) to remove larger suspended solids (here referred to as full sample). The samples then were serially filtered through 0.8-μm- and 0.45-μm-pore-size nitrocellulose filters (Millipore, Sigma-Aldrich). The 0.8-μm and 0.45-μm filters were transferred to 50-ml plastic tubes (Falcon, Greiner) containing 40 ml of sterilized water of the corresponding water matrix and were gently agitated at room temperature for 30 min to resuspend the retained microorganisms. The organisms resuspended from the 0.8-μm filter (here termed the eukaryotic fraction) were then transferred to a cell culture flask (TPP; Milian) and maintained at room temperature throughout the study. The organisms resuspended from the 0.45-μm filter (termed the bacterial fraction) were also maintained at room temperature for a maximum of 8 days. Sterile samples were prepared by filtering each water sample through a 0.22-μm-pore-size nitrocellulose membrane filter or by filtering followed by autoclaving to inhibit enzymatic activity. To quantify the extent of sorption to suspended solids, full LW was autoclaved to inhibit microbial action but preserve particles. A schematic of the different filtration steps and resulting microbial fractions is given in the supplemental material (Fig. S1).

Culturing and enumeration of viruses and phages.

Echovirus 11 (E11) (Gregory strain, ATCC VR737) and adenovirus 2 (HAdV2; kindly provided by Rosina Girones, University of Barcelona) stocks were produced by infecting subconfluent monolayers of BGMK (kindly provided by Spiez Laboratory, Switzerland) and A549 cells (kindly provided by Rosina Girones, University of Barcelona), respectively, as described previously (35). Both cell lines were maintained at 37°C in 5% CO2 with modified Eagle medium (MEM; Gibco, Frederick, MD), supplemented with 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco, Frederick, MD) and 10% (growth medium) or 2% (maintenance medium) heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco, Frederick, MD). The viruses were released from infected cells by freezing and thawing the culture flasks three times. To eliminate cell debris, the suspensions were centrifuged at 3,500 rpm for 5 min. The resulting stock solutions were stored in the freezer at –20°C. Infectious virus concentrations were enumerated by a most probable number (MPN) infectivity assay using 5 replicates per sample as described previously (35). E11 and HAdV2 concentrations in the samples were then determined as the most probable number of cytopathic units per milliliter (MPNCU ml−1).

Marine bacteriophage H6 and its host, Pseudoalteromonas marina, were kindly provided by Pierre Rossi (EPFL). The host bacteria were cultured in marine broth (Pronadisa) at room temperature. Upon reaching exponential phase they were infected with H6 and incubated overnight at room temperature without agitation. The infected cultures were then centrifuged to remove cell debris, and a few drops of chloroform were added in order to denature the remaining organic material. The obtained suspensions were quantified as PFU per milliliter by the double-layer agar technique.

Culturing of bacterial and eukaryotic assemblages.

Natural assemblages of bacteria (retained on the 0.45-μm filter or each sample) were cultured at room temperature in 25 ml of marine broth (Pronadisa) for SW bacteria and in 25 ml of LB broth for LW bacteria. After 2 days, the assemblage reached concentrations of 1 × 109 CFU ml−1 for seawater bacteria and 5 × 108 CFU ml−1 for LW bacteria. Organisms contained in the eukaryotic fractions (retained on the 0.8-μm filter of each sample and resuspended in sterile water matrix) were cultured at room temperature and were fed until they reached the required concentration for the experiments (4 to 8 days). Depending on the experiments and number of samples needed, the organisms were fed once or twice by addition of 30 μl of the corresponding cultured bacterial assemblage to 10 ml of the protist solution.

Protist isolation and identification.

Protist cultures dominated by one species were established from the eukaryotic SW fraction isolated from Atlantic and Mediterranean samples by a serial dilution culture method (36) using 96-well plates and sterile SW as a dilution solution. During the isolation process, 2 μl of cultured SW bacteria (from a stock of 1 × 109 CFU ml−1) was added once a week to each well of the plate. Inverted microscopy was used to qualitatively verify that the population in a well was dominated by a single species. Nucleic acid then was extracted from the wells using the PureLink viral RNA/DNA kit (Invitrogen), and the extracted nucleic acids were amplified using the HotStarTaq plus master mix kit (Qiagen) and 18S primers (37) (Microsynth) by following the supplier’s protocol. After purification using the MSB Spin PCRapace kit (Stratec Molecular), the 18S portions of the nucleic acids were sequenced by Sanger sequencing, and the dominant protist species were identified by BLAST.

Enumeration of bacteria and protists.

The total number of bacterial cells in a sample was determined by flow cytometry by following the protocol of del Giorgio et al. (38), except that the stain concentration was raised from 2.5 μM to 5 μM. In brief, a stock solution of SYTO 13 (5 mM in dimethyl sulfoxide; Lifetech) was 200-fold diluted with deionized water. Aliquots of 50 μl of the dye solution were then mixed with 200 μl of the bacterial sample and were incubated in the dark at room temperature for 10 min. The bacterial concentration was then measured using flow cytometry (Novocyte flow cytometer), and the NovoExpress software was used to determine the absolute bacterial count. The protocol of del Giorgio et al. (38) was followed for gating and cytometric analysis. The protist concentration in the eukaryotic fractions was measured using a Neubauer counting chamber (Bright-line; Hausser-Scientific) and an inverted microscope (Olympus CK X41). The flasks containing protists were gently vortexed, and a 10-μl aliquot was placed on the chamber under a cover slip. The number of protists in each of the four main squares of the chamber was counted by inverted microscopy, and the average value was calculated over four squares. Only the moving protists were counted.

Virus decay experiments.

The effect of microbial grazing on virus decay was quantified in experiments using E11 as a model virus. The eukaryotic fractions were diluted with autoclaved SW or LW prior to the experiments in order to reach a protist concentration of approximately 1,000 or 10,000 cells/ml, as specified in the respective figure legends. Three milliliters of the water sample under consideration was added to a 50-ml plastic tube (Falcon) and amended with E11 to reach an initial virus concentration of approximately 106 MPNCU ml−1. The solutions were incubated at room temperature, and 250-μl aliquots were periodically collected over up to 96 h. Samples were stored at –20°C to prevent further virus decay. At the end of the experiment all samples were enumerated to quantify the residual infective viral titer using the MPN assay. The limit of detection (LOD) of the MPN assay was 20 MPNCU ml−1. Measurements below the LOD were set to the LOD to calculate the log decrease, and all data points were used for the curve fits. Experiments were conducted at different temperatures (4°C, 8°C, 16°C, 22°C, and 30°C) and using different water samples (LW and SW), controls (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS; 5 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM NaCl, pH 7.4] and sterile LW and SW), microbial fractions (bacterial fraction, eukaryotic fraction, and full LW and SW), and nearly pure cultures of protist isolates. Experiments at low temperatures (4°C, 8°C, and 16°C) were conducted in a cooling water bath (Julabo F240), and experiments at 30°C were conducted in an incubator (Memmert, GmbH & Co.). Additionally, experiments were conducted individually for two human viruses (E11 and HAdV2) and a marine bacteriophage (H6), and the resulting decay curves were compared. Each experiment was conducted in duplicate or triplicate. For selected decay experiments, the bacteria and protist cell numbers were enumerated simultaneously. A first-order decay model was used to describe the decay of virus (equation 1):

| (1) |

where C is the viral titer at time t (in MPNCU per milliliter), C0 is the initial viral titer (in MPNCU per milliliter), and k is the decay rate constant (per hour).

The clearance rate per bacterial or protist cell, k′ (milliliters per cell per hour), was determined according to Carrias et al. (39):

| (2) |

where C is the viral titer at time t (in MPNCU per milliliter), C0 is the initial viral titer (in MPNCU per milliliter), and is the time-integrated protist or bacterial concentration (cells per milliliter per hour). The latter term accounts for the finding that both the protist and bacterial concentrations varied over time.

Estimation of solar inactivation.

The solar inactivation in Lake Geneva was estimated across the UVB wavelength range (280 to 320 nm) as

| (3) |

where ksolar, z is the solar inactivation rate constant in Lake Geneva (per hour) at depth z; ksolar′ is the irradiance-normalized inactivation rate constant of E11 by solar UVB light, which corresponds to 1.7 × 10−4 m2 J−1 (20); and (J s−1 m−2) is the solar irradiance for a given wavelength, λ, and water depth, z. The irradiance was determined based on Beer-Lambert’s law:

| (4) |

where (J s−1 m−2) represents the downwelling irradiance at wavelength λ determined using the online TUV calculator tool (40) and (per centimeter) is the absorbance of the water column of Lake Geneva at wavelength λ (Fig. S4).

Data analysis.

All data analyses and statistical tests were performed in R (41). Decay rate constants for pooled replicates were determined by log-linear fits to equation 1 and are reported with 95% confidence intervals as well as adjusted R2 values to indicate the goodness of fit. The following packages were used: ggplot2 (41), grid (41), scales (42), stats (41), reshape2 (43), matrixStats (43), plotrix (43), and pracma (44). The time-integrated protist and bacterial concentrations were calculated using the “cumtrapz” function of the pracma package.

Data availability.

18S rRNA sequences of the isolated protist species are available in GenBank under accession numbers MN555436 (for SUB6396628 Seq1), to MN555438 (for SUB6396628 Seq2). R scripts, which include raw virus decay data, can be downloaded from the journal’s website.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant number 31003A_182468). C.G. was supported by an EPFL Research Internship.

We thank Virginie Bachmann for laboratory assistance.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lodder WJ, van den Berg HHJL, Rutjes SA, de Roda Husman AM. 2010. Presence of enteric viruses in source waters for drinking water production in the Netherlands. Appl Environ Microbiol 76:5965–5971. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00245-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lodder WJ, de Roda Husman AM. 2005. Presence of noroviruses and other enteric viruses in sewage and surface waters in the Netherlands. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:1453–1461. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.3.1453-1461.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yates MV, Gerba CP, Kelley LM. 1985. Virus persistence in groundwater. Appl Environ Microbiol 49:778–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boehm AB, Silverman AI, Schriewer A, Goodwin K. 2019. Systematic review and meta-analysis of decay rates of waterborne mammalian viruses and coliphages in surface waters. Water Res 164:114898. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2019.114898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feichtmayer J, Deng L, Griebler C. 2017. Antagonistic microbial interactions: contributions and potential applications for controlling pathogens in the aquatic systems. Front Microbiol 8:2192–2114. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cliver DO, Herrmann JE. 1972. Proteolytic and microbial inactivation of enteroviruses. Water Res 6:797–805. doi: 10.1016/0043-1354(72)90032-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ward RL, Knowlton DR, Winston PE. 1986. Mechanism of inactivation of enteric viruses in freshwater. Appl Environ Microbiol 52:450–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miki T, Jacquet S. 2008. Complex interactions in the microbial world: underexplored key links between viruses, bacteria and protozoan grazers in aquatic environments. Aquat Microb Ecol 51:195–208. doi: 10.3354/ame01190. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gonzalez JM, Suttle CA. 1993. Grazing by marine nanoflagellates on viruses and virus-sized particles: ingestion and digestion. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 94:1–10. doi: 10.3354/meps094001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pinheiro MDO, Power ME, Butler BJ, Dayeh VR, Slawson R, Lee LEJ, Lynn DH, Bols NC. 2007. Use of Tetrahymena thermophila to study the role of protozoa in inactivation of viruses in water. Appl Environ Microbiol 73:643–649. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02363-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deng L, Krauss S, Feichtmayer J, Hofmann R, Arndt H, Griebler C. 2014. Grazing of heterotrophic flagellates on viruses is driven by feeding behaviour. Environ Microbiol Rep 6:325–330. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sepp T, Järvekülg L, Saarma M. 1992. Investigations of virus-protozoa relationships in the model of the free-living ciliate Tetrahymena pyriformis and adenovirus type 3. Eur J Protistol 28:170–174. doi: 10.1016/S0932-4739(11)80046-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim TD, Unno H. 1996. The roles of microbes in the removal and inactivation of viruses in a biological wastewater treatment system. Water Sci Technol 33:243–250. doi: 10.2166/wst.1996.0681. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsueh TY, Gibson KE. 2015. Interactions between human norovirus surrogates and Acanthamoeba spp. Appl Environ Microbiol 81:4005–4013. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00649-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.AlgaeBase. 2018. AlgaeBase. National University of Ireland, Galway, Ireland: http://www.algaebase.org. Accessed 19 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scoble JM, Cavalier-Smith T. 2014. Scale evolution in Paraphysomonadida (Chrysophyceae): sequence phylogeny and revised taxonomy of Paraphysomonas, new genus Clathromonas, and 25 new species. Eur J Protistol 50:551–592. doi: 10.1016/j.ejop.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lim EL, Dennett MR, Caron DA. 1999. The ecology of Paraphysomonas imperforata based on studies employing in coastal water samples and enrichment cultures. Limnol Oceanogr 44:37–51. doi: 10.4319/lo.1999.44.1.0037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hausmann K, Selchow P, Scheckenbach F, Weitere M, Arndt H. 2006. Cryptic species in a morphospecies complex of heterotrophic flagellates: the case study of Caecitellus spp. Acta Protozool 45:415–431. [Google Scholar]

- 19.WoRMS Editorial Board. 2019. World register of marine species. http://www.marinespecies.org. Accessed 19 December 2018.

- 20.Meister S, Verbyla ME, Klinger M, Kohn T. 2018. Variability in disinfection resistance between currently circulating enterovirus B serotypes and strains. Environ Sci Technol 52:3696–3705. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.8b00851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Payment P, Tremblay M, Trudel M. 1985. Relative resistance to chlorine of poliovirus and coxsackievirus isolates from environmental sources and drinking water. Appl Environ Microbiol 49:981–983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gerba CP, Gramos DM, Nwachuku N. 2002. Comparative inactivation of enteroviruses and adenovirus 2 by UV light. Appl Environ Microbiol 68:5167–5169. doi: 10.1128/aem.68.10.5167-5169.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heaselgrave W, Kilvington S. 2012. The efficacy of simulated solar disinfection (SODIS) against coxsackievirus, poliovirus and hepatitis A virus. J Water Health 10:531–538. doi: 10.2166/wh.2012.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun C-X, Vergara GGRV, Gin KY-H. 2017. Interaction of Microcystis and Phix174 in the aquatic environment. J Environ Eng 143:04017011. doi: 10.1061/(ASCE)EE.1943-7870.0001208. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rose JM, Caron DA, Sieracki ME, Poulton N. 2004. Counting heterotrophic nanoplanktonic protists in cultures and aquatic communities by flow cytometry. Aquat Microb Ecol 34:263–277. doi: 10.3354/ame034263. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zubkov MV, Sleigh MA. 2000. Comparison of growth efficiencies of protozoa growing on bacteria deposited on surfaces and in suspension. J Eukaryot Microbiol 47:62–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2000.tb00012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sibbald MJ, Albright LJ. 1988. Aggregated and free bacteria as food sources for heterotrophic microflagellates. Appl Environ Microbiol 54:613–616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hansen B, Bjornsen PK, Hansen PJ. 1994. The size ratio between planktonic predators and their prey. Limnol Oceanogr 39:395–403. doi: 10.4319/lo.1994.39.2.0395. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pinheiro MDO. 2013. Interactions of ciliates with cells and viruses of fish. PhD thesis. University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pinheiro MDO, Bols NC. 2018. Activation of an aquareovirus, chum salmon reovirus (CSV), by the ciliates Tetrahymena thermophila and T. canadensis. J Eukaryot Microbiol 65:694–704. doi: 10.1111/jeu.12514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Akunyili AA, Alfatlawi M, Upadhyaya B, Rhoads LS, Eichelberger H, Van Bell CT. 2008. Ingestion without inactivation of bacteriophages by Tetrahymena. J Eukaryot Microbiol 55:207–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2008.00316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.ViralZone. 2018. ExPASy bioinformatics resource portal. https://viralzone.expasy.org/. Accessed 29 August 2018.

- 33.Nemerow GR, Stewart PL, Reddy VS. 2012. Structure of human adenovirus. Curr Opin Virol 2:115–121. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2011.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tran Khac V, Quetin P, Anneville O. 2019. Physico-chemical changes in the waters of Lake Geneva and meteorological datas [sic]. Rapp Comm Int Prot Eaux Léman contre Pollut, Campagne 2018, 2019:26–75. (In French.) [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carratalà A, Shim H, Zhong Q, Bachmann V, Jensen JD, Kohn T. 2017. Experimental adaptation of human echovirus 11 to ultraviolet radiation leads to resistance to disinfection and ribavirin. Virus Evol 3:1–11. doi: 10.1093/ve/vex035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lara E, Berney C, Ekelund F, Harms H, Chatzinotas A. 2007. Molecular comparison of cultivable protozoa from a pristine and a polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon polluted site. Soil Biol Biochem 39:139–148. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2006.06.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Uyaguari-Diaz MI, Chan M, Chaban BL, Croxen MA, Finke JF, Hill JE, Peabody MA, Van Rossum T, Suttle CA, Brinkman FSL, Isaac-Renton J, Prystajecky NA, Tang P. 2016. A comprehensive method for amplicon-based and metagenomic characterization of viruses, bacteria, and eukaryotes in freshwater samples. Microbiome 4:20. doi: 10.1186/s40168-016-0166-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.del Giorgio P, Bird DF, Prairie YT, Planas D. 1996. Flow cytometric determination of bacterial abundance in lake plankton with the green nucleic acid stain SYTO 13. Limnol Oceanogr 41:783–789. doi: 10.4319/lo.1996.41.4.0783. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carrias JF, Amblard C, Bourdier G. 1996. Protistan bacterivory in an oligomesotrophic lake: importance of attached ciliates and flagellates. Microb Ecol 31:249–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.UCAR. 2019. Quick TUV calculator. http://cprm.acom.ucar.edu/Models/TUV/Interactive_TUV/. Accessed 20 September 2004.

- 41.R Core Team. 2017. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hadley W. 2017. scales: scale functions for visualization. R package version 0.5.0. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=scales.

- 43.Wickham H. 2007. Reshaping data with the reshape package. J Stat Soft 21:1–20. doi: 10.18637/jss.v021.i12. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hans WB. 2018. pracma: practical numerical math functions. R package version 2.2.2. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=pracma.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

18S rRNA sequences of the isolated protist species are available in GenBank under accession numbers MN555436 (for SUB6396628 Seq1), to MN555438 (for SUB6396628 Seq2). R scripts, which include raw virus decay data, can be downloaded from the journal’s website.