Abstract

Nurse-Family Partnership is a targeted public health intervention program designed to improve child and maternal health through nurse home visiting. In the context of a process evaluation, we posed the question: “In what ways do Canadian public health nurses explain their experiences with delivering this program across different geographical environments?” The qualitative methodology of interpretive description guided study decisions and data were collected through 10 focus groups with 50 nurses conducted over 2 years. We applied an intersectionality lens to explore the influence of all types of geography on the delivery of Nurse-Family Partnership. The findings from our analysis suggest that the nature of clients’ place and their associated social and physical geography emphasizes inadequacies of organizational and support structures that create health inequities for clients. Geography had a significant impact on program delivery for clients who were living with multiple forms of oppression and it worked to reinforce disadvantage.

Keywords: Nurse-Family Partnership, intersectionality, public health nursing, health geography

Kendra was 16 years old when she learned she was pregnant. She has lived with her grandmother since she was a toddler when her mother first started treatment for drug and alcohol addiction. Kendra will have to move out of her grandmother’s home when the baby arrives because there is not enough room for all of them. She has no place to go. She hopes to find an affordable apartment with her boyfriend; however, she is feeling hesitant about this decision. Recently, his controlling behavior has escalated to include physical violence, and he does not allow her to go out with friends and limits her ability to make it to school. They have no consistent source of income and are looking for affordable housing in a large city experiencing a housing crisis. She worries if this stress will hurt her baby. Kendra herself was born extremely premature, around 30 weeks gestation. Shortly after birth she was diagnosed with Fetal Alcohol Syndrome and lives with developmental delays. Sometimes this makes her impulsive and she has difficulty retaining information. She hopes that she is going to make the best decisions for her baby and recently met for the first time with her public health nurse. She has lots of questions about pregnancy and parenting and has agreed to have a nurse visit her. Kendra’s story is a composite, which reflects the experiences of many of the adolescent girls and young women who are enrolled in the Nurse-Family Partnership® (NFP) Program. While providing comprehensive nursing care to clients who are preparing to parent and experiencing multiple challenges, public health nurses are committed to tailoring their services in a way that meets clients’ needs. This often requires that nurses adapt their nursing care to address the structural and organizational constructs that affect their clients, including their locations.

What Is NFP?

NFP is a targeted public health intervention program designed to improve child and maternal health through nurse home visiting (Dawley et al., 2007; Olds, 2006). This home-visitation program supports pregnant adolescent girls and young women by utilizing the skills of baccalaureate prepared registered nurses who receive specialized NFP education to increase their knowledge about the program model, its underlying theories of practice, and develop skills to establish therapeutic relationships with pregnant and parenting women to influence the adoption of healthy behaviors (Olds, 2006). In Canada, this early intervention program is delivered exclusively by specially trained public health nurses (Jack et al., 2012). The goals of NFP include (a) improving pregnancy outcomes by promoting healthy behaviors in the prenatal period; (b) improving child health, development, and safety by promoting competent and sensitive parenting behaviors; and (c) changing mothers’ life courses by promoting financial stability and delaying subsequent pregnancies (Dawley et al., 2007; Jack et al., 2012; Olds, 2006; Olds et al., 2007).

The NFP program has been rigorously evaluated in the United States through three randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that have consistently demonstrated improvements in prenatal health, birth outcomes, and child mental health and development for families enrolled in the program (Olds et al., 2007, 2014). More recently, findings from trials evaluating the effectiveness of NFP in the Netherlands and England have been published, which have demonstrated variability in the program’s capacity to influence a range of maternal and child health outcomes (Mejdoubi et al., 2015; Robling et al., 2016). The Dutch trial reported that NFP was an effective strategy for preventing child maltreatment and reducing intimate partner violence, among other health outcomes (Mejdoubi et al., 2013, 2015) However, in the British trial, no short-term benefits with respect to the primary outcomes (i.e., prenatal smoking, birthweight, child visits and admissions to emergency, and subsequent pregnancies) were measured (Robling et al., 2016). Unlike other implementations of NFP, the trial in England did not include an eligibility requirement of economic disadvantage; primary eligibility was aged 19 or under, first viable pregnancy, and no more than 24 weeks gestation at recruitment (Owen-Jones et al., 2013). These outcomes highlight the importance of conducting context-specific evaluations prior to large-scale implementation.

Currently in British Columbia (BC), Canada, the British Columbia Healthy Connections Project (BCHCP) scientific team is conducting an RCT to measure the effectiveness of NFP, compared with existing services, to improve multiple child and maternal health outcomes (Catherine et al., 2016). This trial is being conducted to establish the effectiveness of this intervention within the Canadian context. An adjunctive process evaluation was conducted between 2013 and 2018 to explore how NFP is implemented and delivered across five unique health authority regions (Jack et al., 2015). If NFP is found to be effective, the process evaluation findings will inform country-specific program adaptations that meet the needs of Canadian mothers and reflect the scope of practice among Canadian public health nurses (Jack et al., 2012, 2015).

NFP implementing agencies are required to deliver the intervention with fidelity to the program’s core model elements (Jack et al., 2012). In Canada, first-time pregnant adolescent girls and young women who meet socioeconomic disadvantage criteria at the time of enrollment are eligible for NFP (Catherine et al., 2016). Profiles of participants enrolled in the BCHCP RCT indicate that at baseline, these individuals experienced multiple social and economic disadvantages (Catherine et al., 2019). Participants are of young maternal age, with almost half (49%) between 14 and 19 years; consequently many had not completed high school (53%), and almost all (94%) were living below the British Columbia poverty threshold (Catherine et al., 2019). Although more than half (57%) of the participants identified as “white,” more than a quarter (27%) identified as “Indigenous” (Catherine et al., 2019, p. 11). In accordance with study ethical approval, all Indigenous participants were living in a place that was not part of a designated indigenous reserve.

Many participants reported pre-existing long-term health conditions (74%), mental health issues (47%), and experience with homelessness (47%) (Catherine et al., 2019). Catherine and colleagues also reported that more than half of study participants experienced moderate to severe childhood abuse (56%) and, within the previous year, half of participants reported intimate partner violence. The data reported reveal “pockets of deep socio-economic disadvantage for this group of BC girls and young women who were pregnant and preparing to parent for the first time” (Catherine et al., 2019, p. 5).

Intersectionality

Considering the layers of disadvantages experienced by the adolescent girls and young women enrolled in the BCHCP RCT, intersectionality was drawn upon to consider the complexities associated with their location in society. Although intersectionality was popularized by Black scholars in the 1990s, it has been proposed as an important theoretical framework in population health research and it is increasingly being applied with attention to equity issues for people living with marginalities (Bowleg, 2012; Hankivsky et al., 2010; Kelly, 2011; McCollum et al., 2019; Rogers & Kelly, 2011; Scheim & Bauer, 2019). Recognizing that many definitions exist to explain the concept of intersectionality (Collins, 2015), we use the following description:

Intersectionality is a way of understanding and analyzing the complexity in the world, in people, and in human experience. The events and conditions of social and political life and the self can seldom be understood as shaped by one factor. They are generally shaped by many factors in diverse and mutually influencing ways. When it comes to social inequality, people’s lives and the organization of power in a given society are better understood as being shaped not by a single axis of social division, be it race or gender or class, but by many axes that work together and influence each other. Intersectionality as an analytic tool gives people better access to the complexity of the work and of themselves. (Hill Collins & Bilge, 2016, p. 2)

It may be more important to consider how intersectionality is used rather than how it is defined. Specifically, understanding domains of power (i.e., interpersonal, disciplinary, cultural, and structural) and how they relate to each other to advantage or disadvantage people’s lives needs to consistently be applied as an analytic framework for social justice (Hancock, 2016; Hill Collins & Bilge, 2016; Hopkins, 2019). Intersectionality allows us to consider how rules are implemented in society and recognizes that inequities do not fall equally on individuals (Hill Collins & Bilge, 2016). From this perspective, we understand that micro factors (e.g., gender, race, ethnicity, and economic status) and existing macro factors (e.g., sexism, classism, and racism) can have a cumulative effect of oppression in society (Bowleg, 2012). Also, concurrent and compounding systems of oppression can negatively affect health outcomes and obstruct access to health services (Hankivsky et al., 2010; Kelly, 2011).

The application of an intersectionality lens to public health research findings is particularly relevant because it helps to understand the complex array of contextual factors experienced by individuals, exposes power differentials, and attends to forces of oppression (Bowleg, 2012; Hancock, 2016; Hill Collins & Bilge, 2016). This approach to health research recognizes that marginalized groups are underrepresented in research and that systems of oppression create multiplicative effects on health disparity (Rogers & Kelly, 2011). Intersectionality in health care seeks to identify and act on social inequalities (Rogers & Kelly, 2011). Pauly et al. (2009) identified the importance for nurses to apply critical perspectives, such as intersectionality, to social justice as a means to address existing health inequities for populations. In this analysis, the application of intersectionality to understanding the delivery of NFP involved: (a) considering how geography affects public health nurses’ ability to provide home-visitation to adolescent girls and young women experiencing social and economic disadvantage; (b) examining how nurses experience challenges in accessing and supporting NFP clients within the context of geography and place; and (c) understanding how these factors interact together to create health care or service-delivery challenges in the Canadian NFP program.

The influence of geography on the delivery of the NFP program was one specific focus of the BCHCP process evaluation. In the context of the larger process evaluation, we posed the question: “In what ways do public health nurses explain their experiences with delivering the NFP program across different geographical environments?” The purpose of this article is to therefore describe and explain how different types of disadvantage experienced by young pregnant and parenting adolescent girls and young women enrolled in this home-visitation program intersect with geographical contexts, and then how this confluence of factors affects how public health nurses deliver the NFP program in BC, Canada.

Methods

The primary objective of the five-year BCHCP process evaluation (2013–2018) was to explore how NFP was implemented and delivered across five BC health authorities. A secondary objective was to identify how nurses experience NFP when delivering the program in small town and rural communities (Jack et al., 2015). Within this process evaluation, the qualitative component was guided by the methodological principles of interpretive description (Thorne, 2016). This qualitative approach was selected because of its relevance for addressing clinical problems and using disciplinary logic to generate knowledge as a way of understanding health care challenges (Thorne, 2016; Thorne et al., 2004). As a methodology, interpretive description pulls from techniques used in social science research in a manner that is most suitable for studying practice-based problems in applied clinical areas (Thorne, 2014, 2016). We applied an intersectionality lens to explore the influence of all types of geography on the delivery of the NFP program in BC and integrated a nursing perspective by applying our nursing knowledge.

Ethics approval was received from 10 institutions: four where research team members held university appointments, at the five health authorities participating in BCHCP process evaluation, and from the Public Health Agency of Canada. Data sources from the process evaluations included NFP nurses, supervisors, and senior administrators; this analysis draws on data collected from the NFP public health nurses. The entire population of nurses delivering NFP in BC were invited to participate in the study and were recruited through their workplaces. All study participants provided written and verbal informed consent and their participation in the study was voluntary. For this analysis, participants included public health nurses (N = 50) from four health authorities that deliver the NFP across different geographical regions of BC. Because one health authority had nurses who only delivered NFP in a small urban area plus the surrounding rural areas, those nurses were interviewed individually to better understand the uniqueness of rural program delivery and the findings specific to rural NFP public health nurse experiences are reported elsewhere (Campbell et al., 2019).

This analysis includes data that were collected through 10 focus groups. Data were collected every 6 months for the BCHCP process evaluation; this analysis includes those data collected in May to June 2015 and April to May 2017. Focus groups ranged in duration from approximately 1.5 to 3 hours; participants ranged from 5 to 10 per group. Semi-structured interview questions guided the focus groups and are presented in Supplementary File 1. The first set of data collected in 2015 helped inform the development of the question guide for the 2017 interviews. Each focus group was conducted by one of two researchers who had graduate degrees in health fields and significant expertise and experience in conducting focus groups. Focus groups were audio-recorded, and all data were transcribed with any identifying information removed.

During the focus groups, nurses were encouraged to describe the types of geography in which clients lived. They were also asked to explain where the program, including home visits, was delivered in a way that helped to explain their experiences. Most frequently, they used community names, which have been removed to maintain confidentiality. We used Statistics Canada’s Population Centre and Rural Area Classification 2016 to organize and present the findings (Government of Canada, 2017). The Statistics Canada conceptual model reflects the existence of a rural-urban continuum and divides areas into three centers based on population size. These constructs include large population centers, medium population centers, and small population centers/rural. Although we recognize that community descriptors should not be reduced to population alone, this model was used to present findings in a manner that is useful for other researchers and knowledge users.

The pragmatic and flexible approach of the interpretive description methodology allowed for the application of a variety of strategies to bring rich interpretation and rigor to the data analysis (Thorne, 2016). We primarily employed the Sort and Sift, Think and Shift approach, which encouraged continuous movement between engaging with the data and stepping back to reflect on and review emerging findings (Maietta, 2006). The core elements of this approach include (a) becoming familiar with the data, (b) memo writing, (c) categorizing data, (d) producing reflective diagrams, (e) bridging the data, and (f) presenting the whole data set (Fryer et al., 2016; Maietta, 2006).

Although we reflected on the analysis of these data and observed the oppression of clients, we used intersectionality to provide a more critical examination of how geography affects the delivery of NFP for the nurses in this study. Following the tenets of interpretive description, the goal of this analysis was not to represent the whole population but rather to critically identify clinically relevant findings that are meaningful and credible to those who are interested in this topic (Thorne, 2016). Finally, drawing on intersectionality as an analytical tool provided a framework that helped us to consider how geography became an additional intersect compounding marginality for the clients that public health nurses visited when delivering the NFP program.

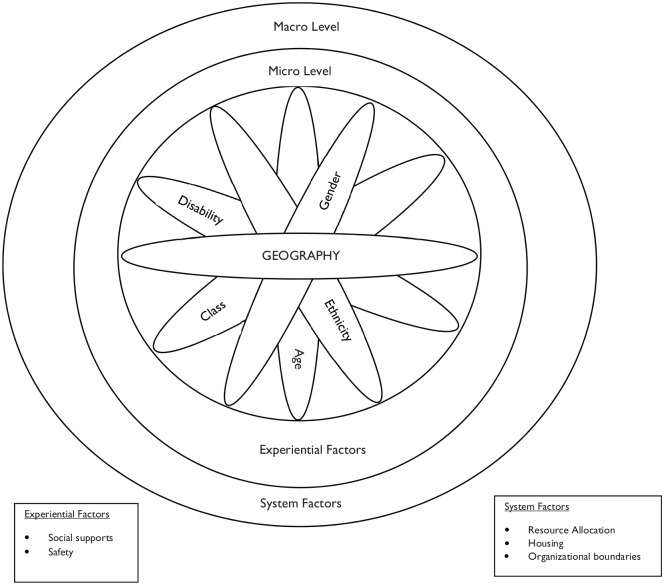

While applying an intersectionality lens to this analysis, we used Núñez’s (2014) multilevel intersectionality framework to acknowledge the multiple constructs of disadvantage experienced by clients enrolled in NFP and to reflect the complexities associated with delivering the NFP program within the Canadian context. Micro-level or social categories of gender, age, class, and disability are typically represented in models of intersectionality (Hancock, 2016; Hill Collins & Bilge, 2016). Our results suggest that geography is an additional consideration that must be taken into account because of how it intersects with other positionalities. Guided by Núñez’s framework, and outlined in Figure 1, we acknowledge the multiple positionalities that create health inequities for NFP clients from the perspectives of their public health nurses. The constructs of age, gender, class, and geography were experienced as a significant disadvantage for all women enrolled in NFP. Some NFP clients also experienced other forms of inequity through disability (physical or mental health) and ethnicity (most commonly Indigenous). We move beyond the micro-level (individual factors) and present the meso- (experiential) and macro- (system) level factors that interact with geography and affect the delivery of the NFP program.

Figure 1.

Multilevel model of intersectionality applied to NFP.

Note. NFP = Nurse-Family Partnership®.

Findings

The results of this analysis represent the experiences of 50 public health nurses in BC who took part in focus groups conducted over 2 years. Responses were overwhelmingly consistent over time and similar issues were raised. We learned from study participants that delivering client-centered care was a priority, which overcame any frustrations brought about by geography. Their accounts highlight the challenges and successes of delivering NFP across diverse geographical settings, regardless of the nurses’ primary work or home location. Geography ranged from urban centers to rural and small communities.

Experiential Factors

The following section includes experiential factors of safety and social support and presents participant observations of their intersections with geography. These factors involve intersections between geography and gender, class, age, and disability.

Geography and safety

Consistently across all focus groups over both years and all geographical settings, nurses expressed concerns about safety issues for their clients and themselves. The nature of NFP work was such that many clients lived in situations where their physical or emotional safety was depleted, as acknowledged by one nurse: “But it’s just [pause] I know their lives aren’t safe.” This was succinctly described by another nurse: “Safety is a challenge for almost all [clients] whether it’s personal safety in their relationships with either boyfriends or parents or housemates. Or big, general safety, like the neighbourhood they live in.” Nurses disclosed that almost all their NFP clients have a history of family violence or were currently living in situations where they were exposed to multiple forms of interpersonal or community-level violence.

Dimensions of NFP client safety extended to include neighborhood crime and social cohesion. Nurses reported how neighborhoods would transform in the evenings with an increasing safety risk. A public health nurse practicing in a large population center said, “And the community seems to change after about five o’clock. It’s almost like you could see it visibly happening.” Nurses were concerned for their clients’ safety but also for themselves and their property (i.e., their cars).

While NFP public health nurses were aware of the risks associated with their places of work, it was not a deterrent to delivering the program but an element of practice that required some additional planning:

It’s the community that we work in. Well, it has, I would say, a higher crime rate and there’s lots of homeless people. You kind of need to watch yourself so we tend not to want to do evening visits because of that.

They also adjusted their plans when needed because of police activity in neighborhoods:

One particular neighbourhood I was in, often there were police incidents. And so, having to adjust my plans of where I was going to park, where I was going to visit, like was I actually going to walk into that building circled by police officers and police cars? You know, so adjust your plans based on the incidents happening that day.

Effective planning helped NFP nurses to deliver the program in times and places where safety concerns were noted.

Completing sensitive nursing assessments during home visits, such as asking about intimate partner violence, while other family members were present and not allowing for privacy required nursing skill and awareness of safety issues for nurses and clients. Nurses disclosed that almost all of their NFP clients have a history of family violence or are currently living in situations of violence. The inherent difficulty of creating a connection and a relationship with the NFP client when she may not feel comfortable with the nurse in the home guided public health nurses to find alternative settings until the home environment was safe for visits. Settings such as walking trails or parks had the benefit of reducing client anxiety and increasing physical activity, but parks, and even coffee shops, became distracting and difficult to manage with active toddlers present. Nurses were also aware of client safety issues and concerned for clients who worried about being gone from the home, even to sites such as a library, for a longer period when a boyfriend did not want her to be involved in the program. However, libraries were also considered to be “a very calm, safe place” to conduct an NFP visit.

Geography and social support

Limited social capital in small population and rural centers further disadvantaged NFP clients, particularly when the NFP client was not well connected to the community. This was a significant issue for NFP nurses whose clients shared their need for social connection: “I had one client who said, ‘that’s my heart’s desire—a best friend’.” Another added, “A best friend. Yeah, I’ve heard that before.” The high incidence of mental health challenges for NFP clients complicated issues of isolation:

And really, I think many of our clients face isolation, social isolation. And that could be compounded if you have some anxiety around speaking to people or seeing people that could further [affect] your isolation, so in a smaller community that can [be hard].

Other public health nurses experienced similar difficulties supporting NFP clients who desired connection but encountered anxiety during social opportunities, such as new mother groups. As NFP public health nurses attempted to be client-centered and focused on clients’ goals, small community-level constraints challenged their success.

System Factors

In this section, we present the intersections of geography with (a) resource allocation, (b) housing, and (c) organizational boundaries. Systems of oppression inherent to these findings include class, gender, age, and ability.

Geography and resource allocation

Referring clients to appropriate health and social services was a frequent activity initiated and completed by NFP public health nurses. Clients were commonly referred to such community-based services such as education programs, financial support services, primary health care practitioners, housing, mental health, and child health services, among others. Predictably, when participants discussed the availability of resources complementary to NFP in large population centers, there was an abundance. In comparison, nurses providing the program in small population or rural areas reflected on the limited number of available or accessible resources:

In our smaller community we have less services available for clients and so that is definitely challenging. When perhaps you’re doing assessments and clients having concerns and then there’s not a lot of services to be able to support that client. And so that can be a disadvantage as well in being a smaller community.

In medium population centers, services were accessible with minimal travel time and many communities had suitable transit systems. Public health nurses seemed to have limited difficulties in supporting NFP clients who needed additional services and were living in medium-sized population centers.

Where geography intersects with limited accessible health and social services in small and rural communities, participants discussed how community practitioners were keenly aware of all available services and appropriately referred clients. The familiarity and collegiality between service providers was evident: “Sometimes smaller [communities] can be way simpler because you get to know the players.” However, this became an issue if a client or a practitioner were to “burn bridges” with a community service, rendering the service no longer available to that individual (or their clients in some cases) with no other accessible options and inadequate or nonexistent transit systems. The burden to fill this gap was placed on the NFP nurse: “We are not all things to all people. Not the addiction counsellor. Not the psychologist. Yet for many clients, we are it as their primary provider or there’s not resources in the community.” Although some frustration is noted in this narrative, NFP nurses practiced to the fullest extent of their scope to meet clients’ needs.

Large urban centers offered a different challenge for NFP public health nurses. Although there was an abundance of available resources, NFP clients encountered difficulty in accessing some of these services for a variety of reasons. In some instances, service locations were difficult to find or changes in funding caused an unexpected move in location. In addition to not knowing where services exist, many NFP public health nurses shared that in some cases they were unaware of the range of services available to their clients. This problem also existed for other service professionals who in turn may not know to refer their clients into the NFP program: “We are just one of 50 other places that they can refer their client to.” The myriad of possible resources in large population centers created difficulties for NFP nurses to provide, or receive, referrals from other sources.

As a result of numerous available services in these urban areas, public health nurses recognized that their clients were often burdened by many services. For example, one nurse commented, “Yeah, my client had five appointments yesterday and she canceled two. She said she prioritized. And she kept me. I was one of the top three.” This was a concern for NFP public health nurses who have prearranged scheduled visits and yet, clients become overwhelmed with the number of services provided to them:

A number of clients that I have are involved with a lot of other people. So, it might be like groups that are mandated by the ministry [responsible for social services] or medical appointments or just like a lot of those sorts of things. They have a lot of appointments and I’m one more appointment for them to keep.

NFP public health nurses revealed how their clients encounter difficulties in large population centers despite the availability of services and readily available transit.

Geography and housing

The housing affordability problem in the province was identified by nurses as the instigating factor contributing high levels of client mobility. Clients moved frequently to find affordable housing, often into unsafe environments, which resulted in further subsequent movement. Public health nurses indicated that almost all of their clients had moved at least once during their time in the program, with many relocating multiple times.

Nurses discussed the changing rural–urban interface, where previously rural areas and farmlands were developing housing infrastructure and enticing clients to move away from familiar communities. NFP clients’ decisions to move, from the perspective of their nurses, were primarily to secure affordable housing. During a focus group conversation, public health nurses discussed how the geography of the province was developing, landscapes were changing, and their NFP clients were moving to a specific newly constructed area. The following dialogue reflects two different experiences of NFP nurses, how they understood client decisions, the outcome of client mobility, and its impact on client safety:

City 1 public health nurse: I have clients in [City 1] and now in [Town 2]. [Town 2] used to all be rolling farmland and there’s been a huge, explosive development of all these areas for new housing [in Town 2] . . . Often my clients sign up in [City 1] but they move to [Town 2] because that’s where the affordable housing is. There’s a lot of new housing with basement suites going in all over the [Town 2] geography.

<General agreement from other focus group participants>

Town 2 public health nurse: It’s interesting because you guys are saying people are moving into [Town 2]. But all of my clients [in Town 2] want to move out because they don’t feel safe there. Because where they can afford to live is in certain rougher areas.

The housing problem created the need for frequent movement, which in turn led to unsafe environments for NFP clients, and ultimately to further movement for clients, despite newly developing areas.

Geography and organizational boundaries

Catchment areas established by health authorities determined how clients were assigned to NFP public health nurses. However, client mobility interfered with the premise of having a primary nurse inherent to the NFP program. Nurses explained that clients are transferred to another nurse if they move to a different health authority area. In some cases, this hyper-mobility led to NFP clients bouncing between nurses: “She [the client] was transferred to another health authority and then was transferred back when she moved here again, yeah.” It took commitment from the nurse to follow NFP clients when they moved because they were often in transit:

And then they [clients] move and so they, they transition a lot, right? Some of them don’t want to change nurses. So, then you make the choice and commitment to follow them wherever they go to. So, then that could really broaden your [geographical] horizon.

The ideal of maintaining a relationship with a primary nurse appeared to be important for both public health nurses and clients in the NFP program.

Nurses attempted to meet client needs and maintain consistency wherever possible. For example, one set of two nurses worked together to provide care by Nurse A in one city while the client was pregnant and working, transferred to Nurse B when she moved after the birth of the baby, and reassigned to the initial Nurse A when she returned to work in the city. NFP public health nurses discussed other strategies that allowed them to remain involved without transferring clients, such as meeting a client outside of her home on the nurse’s side of the catchment boundary or making appointment times at the beginning or end of the day to maximize the efficiency of the nurse’s driving time. Each strategy was client-focused, but also intended to reduce unnecessary travel especially across broad geographical regions.

The importance of client retention and the desire to follow mobile clients was abundantly clear across all focus groups and from each NFP public health nurse. Nurses understood that following NFP clients when they moved was difficult as indicated by this public health nurse: “The geography part [pause] that is going to be difficult if we are still following [the client] but yes we want to follow our clients. And I totally believe in that for client retention.” Another nurse noted that disrupting relationships with fragile and marginalized clients can change future interactions with other caregivers as shared in this quotation:

The [client] that I do the supervised [by family services] visits with has had a multitude of people [service providers] involved with her in the past before she had her baby and it appears that she has broken off relationships with different professionals over the time and I don’t sense that she [pause] I think it will take a long time [for her] to develop that trust again.

The outcome of breaking trust for clients with past traumas or health conditions was that clients lose faith in the system when they lose service providers. Nurses recognized the difficulties of maintaining care of clients with multiple health and social disadvantages and questioned services that did not ease transitions for clients:

I think for a lot of people [clients], and especially if they’ve had multiple issues all the time, they’re used to people [service providers]. Or they move and they’ve lost another social worker and they don’t really care. You know they’re used to that a little bit . . . It’s like wow, they’ve got mental health issues. How come they can’t [continue in a program/service]?

Other nurses shared similar insights into the challenges of delivering NFP to clients who moved across geographical and institutional (health authority) boundaries and its impact on clients’ service providers:

She [the client] said “I think you’re the only one that’s going to be coming with me when I move.” Because she was saying her social worker, her family education support worker, like everybody except for me [was not following the client post-move]. And so that was a big [pause] that was a big deal for her.

Public health nurses were ultimately motivated by client needs to provide consistency of care and to maintain involvement in the lives of their clients despite their home location.

A rural–urban interface was created by hyper-mobile NFP clients where public health nurses worked across boundaries to deliver the NFP program across a variety of communities despite their home office location. In addition, public health nurses working in large population centers discussed how they would be assigned to clients in small population or rural centers when rural public health nurses were at caseload capacity. Hence, NFP public health nurses were delivering the program despite their lack of familiarity with the community or its resources. In rural communities where homeless shelters or other services were unavailable, mobile clients often moved into other people’s homes for housing:

Yeah, they [rural NFP clients] tend to move around like as you’ve all discussed [about clients living in large and medium population centres]. So here in [rural area], people will move to different parts of the [area]. [Clients move in with] lots of extended family as well. [Clients] living with roommates or other folks because of the cost of housing. And that does impact the nature of home visiting as well when you talk about one-to-one [home visits]. Yes, there’s one visitor and one client; however, the context is often a lot more people. So, I think that is partially related to geography in the sense of housing costs and [living in] rural.

At times, geography could affect the place where home visits occurred when homeowners were not amenable to having an NFP nurse in the home. When providing home visits for clients, NFP public health nurses delivered care across geographical settings, institutional borders, and unsafe housing environments not limited by the location of their home office or catchment area.

Discussion

The results of our analysis suggest that the nature of clients’ place and their associated social and physical geography emphasizes inadequacies of organizational and support structures that create health inequities for clients enrolled in the NFP program. Geography had a significant impact on NFP program delivery for clients who were living with multiple forms of oppression and worked to reinforce disadvantage. Specifically, we address issues that are prevalent for public health nurses in BC who are delivering NFP to pregnant or parenting adolescent girls and young women who are living in situations of social and economic disadvantage. We learned that geographical contexts intersect with other positionalities in clients’ lives, thus affecting program delivery. NFP clients have multiple social, health, and economic disadvantages stemming from issues of poverty, disability, racism, sexism, and classism. Public health nurses delivering the program in varied geographical settings recognized how systems are inconsistently meeting clients’ needs or further marginalizing this population. Geography was an additional intersection of disadvantage for NFP clients. Although geography affected program delivery, public health nurses were able to identify the benefits of NFP program for their clients and understood the need to address issues for clients based on their location.

The results of this analysis, and the conclusions drawn, can assist health practitioners, clinicians, and policy makers who are interested in understanding more about geography when working with clients experiencing multiple forms of disadvantage. This analysis does not produce any definitive claims as that is beyond this form of inquiry but attends to patterns and difference (Thorne, 2016). We also recognize that these experiences are specific to the group of public health nurses who attended our focus groups and not representative of every possible scenario. We had no representation from remote communities, and it will be important to understand how the challenges of living in a remote community will affect adolescent girls’ and young women’s experiences if NFP was to be expanded into such communities. However, these findings provide important insights into place, disadvantage, and the delivery of NFP in BC.

It is a significant limitation of this research that race was notably missing from the findings. When using intersectionality, it is important to consider how race—along with other forces of oppressions—factor into the results (Hancock, 2016; Hill Collins & Bilge, 2016). This may have occurred because intersectionality was used as an analytic tool and the interviewers did not specifically ask about client ethnicity or how it affected program delivery. It may also have been useful to consider the ethnic backgrounds of the nurses as some may not have a heightened awareness of, or understand, race as an oppression. Given that just under half of the RCT participants identified as an ethnicity other than “white” (Catherine et al., 2019), it is likely that many NFP clients experienced oppression based on race. Intersectionality as a theory indicates that people of color or indigeneity experience compounding marginalities (Hancock, 2016; Hill Collins & Bilge, 2016). Therefore, it is important for future NFP studies to consider how race intersects with geography.

Clients often lived in neighborhoods that were unsafe, perhaps attributed to poverty—but clients’ lives were unsafe overall. This finding was consistent across the rural–urban continuum and nurses adjusted their home-visiting plans when needed to ensure the mutual safety of themselves and clients. Specifically, this form of safety refers to violence and neighborhood crime. It does contrast with findings from a cross-sectional survey conducted in Ontario, which described the differences in occupational hazards across geography for home care nurses (Wong et al., 2017). They found that nurses in rural areas practiced in safer environments than their urban counterparts. Wong and colleagues indicated that visits to unsafe neighborhoods in towns, suburban, or urban areas occurred 2.7 to 3.6 times that of rural areas. Our analysis indicated that NFP clients living in urbanized areas were commonly in unsafe neighborhoods, but rural clients were also living in riskier areas. This difference could be attributed to the multiple sources of oppression experienced by NFP clients compared with the diversity of economic and social positions (including those of privilege) of the families visited by home care nurses (Wong et al., 2017).

We learned from our study participants that clients’ lives are unsafe overall, and this is confirmed by the NFP RCT data, which indicated that many clients who were eligible for the NFP were living in situations of violence (Catherine et al., 2019). Internationally, urbanization is considered a key indicator of crime (Dijk et al., 2007). However, Canadian crime rates are not reported based on rural or urban boundaries; instead, information is provided from within or outside of metropolitan areas, with less known about rural violence (Ruddell & Lithopoulos, 2016). Northcott (2015) reported that Canadian domestic violence rates are higher in rural versus urban areas. Given the variances in literature, we suggest that attention to safety is necessary for home-visiting nurses regardless of the geography and should be reflected in program planning, nurse education, and policy development. This is particularly important for populations living in situations of violence. We also learned from nurses in our study that safety risks involved in delivering client care were not a deterrent to service delivery but rather something that required planning.

The mobility of clients had a significant impact on how nurses were able to deliver the NFP program. Beyond scheduling concerns, clients’ frequent moves out of catchment areas affected the NFP primary nurse model. It is important to note that NFP nurse recommendations include to continue to provide a primary nurse wherever possible, even when travel time will be extended, and to work with a secondary nurse when the client’s living arrangement is temporary. Other literature has also noted the importance of continuity of care for client satisfaction in maternity care, increasing client health outcomes, and the benefit of shared care models (Homer, 2016; Lewis et al., 2016; Russell et al., 2011). This study adds to the current understanding of continuity of care by highlighting that economically disadvantaged and precariously housed clients are disadvantaged by policies that discharge clients based on geographical boundaries.

Our study indicates that, in addition to clients’ preferences to maintain continuity of care with a single nurse, nurses were also more satisfied when they were able to follow mobile clients. This finding may have implications for both client and nurse retention in home-visiting programs. Other researchers have evaluated issues of client retention and attrition in NFP through mixed methods studies and indicated that consistency in nursing care is positively associated with client retention (Ingoldsby et al., 2013; O’Brien et al., 2012). Balancing nurse and clients’ preference for the primary nurse over possible demands of extended travel is essential for maintaining client involvement in NFP. Where this is not possible, we stress the importance of collaboration between providers to support clients’ needs and facilitate change. This is particularly important for primary care programs where trust and engagement are necessary to achieve desired client outcomes.

A recent review exploring scheduling home health care nurses recognized the heterogeneity that exists in home visiting and nurses are faced with multiple constraints including, but not limited to, scheduled breaks, client preference, and nurse workload (Fikar & Hirsch, 2017). To further this list of constraining factors, our analysis adds the barrier of delivering a program that is based on client need, for a group that regularly experience crises. Therefore, it is often difficult to cluster visits based on clients’ geographical location. This difficulty is further compromised by the mobile nature of NFP clients. Indeed, this finding is relevant to program managers and nurses who are considering the impact of geography on determining appropriate workload levels.

Public health nurses who participated in this study recognized the need to follow clients across different geographical landscapes. It is noteworthy that NFP nurses were one of the few, and often the only, health or social service providers who would follow clients when they moved across the rural–urban interface. Nurses cited that clients most often moved because of economic hardship and lack of access to safe and affordable housing. This is similar to the findings of Janczewski et al., (2019) who examined patterns of client attrition in long-term home visiting. They concluded that client mobility may be associated with lower socioeconomic stability. However, the impact of client attrition due to moving out of service is largely missing in home-visiting research. It may be that institutionally defined service boundaries further marginalize a disadvantaged group by removing access to health and social services based on geography. This may also cause harm to children by interrupting child protection services when clients move to low-resourced areas. For women who are living without a safe home and those living with physical or mental disabilities, the effects of service disruption may be more pronounced and negatively impactful.

From the NFP rural–urban interface, nurses had a unique vantage point to observe the geographical differences in available and accessible client services. Resources in rural areas were scarce but nurses and providers were well-connected and therefore able to promote and support client services. Though the under-servicing of rural clients is concerning, it is already well documented in the literature (Grzybowski et al., 2011; Kornelsen & Grzybowski, 2005, 2006; Sutherns & Bourgeault, 2008). The connection that exists in rural communities is also recognized in a large body of literature as a small town and rural community strength (Campbell et al., 2019; MacKinnon, 2008, 2012; MacLeod et al., 2008; Moules et al., 2010; Munro et al., 2013). Our study highlights the necessity of public health nursing programs for disadvantaged clients who may have few other available options and supports health equity.

Clients in large population centers were at times overscheduled and consequently missed appointments for some services. This suggests that although services are available, the appropriate dose, mix, and coordination of programs may not be delivered to clients. In addition, clients may experience feelings of heightened surveillance and attempt to evade services. These findings are of great concern and require further exploration and investigation into collaboration between programs serving similar populations. This unique finding of burdening clients with services should be urgently addressed so as to more efficiently utilize resources for a group that experiences consistent and multiple forms of disadvantage. Further disadvantaging clients by overscheduling may inflate negative program outcomes.

The results of this study suggest the need for a more nuanced understanding of the nature of geography and how it can intersect with other sources of disadvantage to contribute to health inequity. Within the context of nurse home-visitation programs, geography is a consideration for program delivery that requires the same attention as other aspects of nursing care. Further investigation is required to determine the effectiveness of programs such as NFP for clients living in small town or rural communities. It will be important to learn about how compounding disadvantages interfere with health outcomes for small population or rural-dwelling populations. Analyzing data using an intersectionality lens allowed for a critical exploration of geography and service-delivery boundaries as one way that disadvantage affects adolescent girls and young women in the NFP program and to a lesser extent for the nurses who provide complex nursing care for them.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Supplementary_file_1 for Nurse-Family Partnership and Geography: An Intersectional Perspective by Karen A. Campbell, Karen MacKinnon, Maureen Dobbins and Susan M. Jack in Global Qualitative Nursing Research

Author Biographies

Karen A. Campbell, RN, MN, is a PhD student at the School of Nursing, McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada.

Karen MacKinnon, RN, PhD, is an associate professor at the School of Nursing, University of Victoria in British Columbia, Canada.

Maureen Dobbins, RN, PhD, is a professor at the School of Nursing, McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada.

Susan M. Jack, RN, PhD, is a professor at the School of Nursing, McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported by the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) under Contract #4500309971 to Dr. Susan M. Jack.

ORCID iD: Karen A. Campbell  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5318-5112

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5318-5112

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- Bowleg L. (2012). The problem with the phrase women and minorities: Intersectionality-an important theoretical framework for public health. American Journal of Public Health, 102(7), 1267–1273. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell K. A., MacKinnon K., Dobbins M., Van Borek N., Jack S. M. (2019). Weathering the rural reality: Delivery of the Nurse-Family Partnership home visitation program in rural British Columbia, Canada. BMC Nursing, 18(1), Article 17. 10.1186/s12912-019-0341-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catherine N. L. A., Gonzalez A., Boyle M., Sheehan D., Jack S. M., Hougham K. A., Waddell C. (2016). Improving children’s health and development in British Columbia through nurse home visiting: A randomized controlled trial protocol. BMC Health Services Research, 16(1), Article 349. 10.1186/s12913-016-1594-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catherine N. L. A., Lever R., Sheehan D., Zheng Y., Boyle M. H., McCandless L., . . . For the British Columbia Healthy Connections Project Scientific Team. (2019). The British Columbia Healthy Connections Project: Findings on socioeconomic disadvantage in early pregnancy. BMC Public Health, 19(1), Article 1161. 10.1186/s12889-019-7479-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins P. H. (2015). Intersectionality’s definitional dilemmas. Annual Review of Sociology, 41(1), 1–20. 10.1146/annurev-soc-073014-112142 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dawley K., Loch J., Bindrich I. (2007). The Nurse-Family Partnership. American Journal of Nursing, 107(11), 60–67. 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000298065.12102.41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijk J. J. M., van Kesteren J., Smit P. (2007). Criminal victimisation in international perspective: Key findings from the 2004-2005 ICVS and EU ICS. Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek-en Documentatiecentrum, Boom Juridische Uitgevers. [Google Scholar]

- Fikar C., Hirsch P. (2017). Home health care routing and scheduling: A review. Computers & Operations Research, 77, 86–95. 10.1016/j.cor.2016.07.019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fryer C. S., Passmore S. R., Maietta R. C., Petruzzelli J., Casper E., Brown N. A., Quinn S. C. (2016). The symbolic value and limitations of racial concordance in minority research engagement. Qualitative Health Research, 26(6), 830–841. 10.1177/1049732315575708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Government of Canada. (2017). Population centre and rural area classification 2016. https://www.statcan.gc.ca/eng/subjects/standard/pcrac/2016/introduction

- Grzybowski S., Stoll K., Kornelsen J. (2011). Distance matters: A population based study examining access to maternity services for rural women. BMC Health Services Research, 11(1), Article 147. 10.1186/1472-6963-11-147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock A. M. (2016). Intersectionality: An intellectual history. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hankivsky O., Reid C., Cormier R., Varcoe C., Clark N., Benoit C., Brotman S. (2010). Exploring the promises of intersectionality for advancing women’s health research. International Journal for Equity in Health, 9(1), Article 5. 10.1186/1475-9276-9-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill Collins P., Bilge S. (2016). Intersectionality. Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Homer C. S. (2016). Models of maternity care: Evidence for midwifery continuity of care. Medical Journal of Australia, 205(8), 370–374. 10.5694/mja16.00844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins P. (2019). Social geography I: Intersectionality. Progress in Human Geography, 43(5), 937–947. 10.1177/0309132517743677 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ingoldsby E. M., Baca P., McClatchey M. W., Luckey D. W., Ramsey M. O., Loch J. M., Olds D. L. (2013). Quasi-experimental pilot study of intervention to increase participant retention and completed home visits in the nurse-family partnership. Prevention Science: The Official Journal of the Society for Prevention Research, 14(6), 525–534. 10.1007/s11121-013-0410-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack S. M., Busser D., Sheehan D., Gonzalez A., Zwygers E. J., Macmillan H. L. (2012). Adaptation and implementation of the Nurse-Family Partnership in Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health/Revue Canadienne de Sante Publique, 103(7 Suppl. 1), eS42–eS48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack S. M., Sheehan D., Gonzalez A., McMillan H. L., Catherine N., Waddell C. (2015). British Columbia Healthy Connections Project process evaluation: A mixed methods protocol to describe the implementation and delivery of the Nurse-Family Partnership in Canada. BMC Nursing, 14, Article 47. 10.1186/s12912-015-0097-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janczewski C. E., Mersky J. P., Brondino M. J. (2019). Those who disappear and those who say goodbye: Patterns of attrition in long-term home visiting. Prevention Science, 20(5), 609–619. 10.1007/s11121-019-01003-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly U. A. (2011). Theories of intimate partner violence: From blaming the victim to acting against injustice. Advances in Nursing Science, 34(3), E29–E51. 10.1097/ANS.0b013e3182272388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornelsen J., Grzybowski S. (2005). The costs of separation: The birth experiences of women in isolated and remote communities in British Columbia. Canadian Women Studies Journal, 24, 75–80. [Google Scholar]

- Kornelsen J., Grzybowski S. (2006). The reality of resistance: The experiences of rural parturient women. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 51(4), 260–265. 10.1016/j.jmwh.2006.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis L., Hauck Y. L., Ronchi F., Crichton C., Waller L. (2016). Gaining insight into how women conceptualize satisfaction: Western Australian women’s perception of their maternity care experiences. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 16(1), Article 29. 10.1186/s12884-015-0759-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon K. (2012). We cannot staff for “what ifs”: The social organization of rural nurses’ safeguarding work. Nursing Inquiry, 19(3), 259–269. 10.1111/j.1440-1800.2011.00574.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon K. A. (2008). Labouring to nurse: The work of rural nurses who provide maternity care. Rural and Remote Health, 8(1047), Article 16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod M. L. P., Martin Misener R., Banks K., Morton A. M., Vogt C., Bentham D. (2008). “I’m a different kind of nurse”: Advice from nurses in rural and remote Canada. Nursing Leadership, 21(3), 40–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maietta R. C. (2006). State of the art: Integrating software with qualitative analysis. In Curry L., Shield R., Wetle T. (Eds.), Improving aging and public health research: Qualitative and mixed methods (pp. 1–29). American Public Health Association and the Gerontological Society of America. [Google Scholar]

- McCollum R., Taegtmeyer M., Otiso L., Tolhurst R., Mireku M., Martineau T., Theobald S. (2019). Applying an intersectionality lens to examine health for vulnerable individuals following devolution in Kenya. International Journal for Equity in Health, 18(1), Article 24. 10.1186/s12939-019-0917-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mejdoubi J., Heijkant S. C. C. M., van den Leerdam F. J. M., Heymans M. W., Crijnen A., Hirasing R. A. (2015). The Effect of VoorZorg, the Dutch Nurse-Family Partnership, on child maltreatment and development: A randomized controlled trial. PLOS ONE, 10(4), Article e0120182. 10.1371/journal.pone.0120182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mejdoubi J., Heijkant S. C. C. M., van den Leerdam F. J. M., Heymans M. W., Hirasing R. A., Crijnen A. A. M. (2013). Effect of nurse home visits vs. usual care on reducing intimate partner violence in young high-risk pregnant women: A randomized controlled trial. PLOS ONE, 8(10), Article e78185. 10.1371/journal.pone.0078185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moules N. J., MacLeod M. L. P., Thirsk L. M., Hanlon N. (2010). “And then you’ll see her in the grocery store”: The working relationships of public health nurses and high-priority families in northern Canadian communities. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 25(5), 327–334. 10.1016/j.pedn.2008.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munro S., Kornelsen J., Grzybowski S. (2013). Models of maternity care in rural environments: Barriers and attributes of interprofessional collaboration with midwives. Midwifery, 29(6), 646–652. 10.1016/j.midw.2012.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northcott M. (2015). Domestic violence in rural Canada (Department of Justice No. Issue No. 4). https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/cj-jp/victim/rd4-rr4/p2.html

- Núñez A. M. (2014). Employing multilevel intersectionality in educational research: Latino identities, contexts, and college access. Educational Researcher, 43(2), 85–92. 10.3102/0013189X14522320 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien R. A., Moritz P., Luckey D. W., McClatchey M. W., Ingoldsby E. M., Olds D. L. (2012). Mixed methods analysis of participant attrition in the Nurse-Family Partnership. Prevention Science: The Official Journal of the Society for Prevention Research, 13(3), 219–228. 10.1007/s11121-012-0287-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olds D. L. (2006). The Nurse-Family Partnership: An evidence-based preventive intervention. Infant Mental Health Journal, 27(1), 5–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olds D. L., Kitzman H., Knudtson M. D., Anson E., Smith J. A., Cole R. (2014). Effect of home visiting by nurses on maternal and child mortality: Results of a 2-decade follow-up of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatrics, 168(9), Article 800. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olds D. L., Sadler L., Kitzman H. (2007). Programs for parents of infants and toddlers: Recent evidence from randomized trials. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 48(3–4), 355–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen-Jones E., Bekkers M. J., Butler C. C., Cannings-John R., Channon S., Hood K., Robling M. (2013). The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the Family Nurse Partnership home visiting programme for first time teenage mothers in England: A protocol for the Building Blocks randomised controlled trial. BMC Pediatrics, 13(1), Article 114. 10.1186/1471-2431-13-114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauly B. M., MacKinnon K., Varcoe C. (2009). Revisiting “who gets care?” Health equity as an arena for nursing action. Advances in Nursing Science, 32(2), 118–127. 10.1097/ANS.0b013e3181a3afaf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robling M., Bekkers M.-J., Bell K., Butler C. C., Cannings-John R., Channon S., Torgerson D. (2016). Effectiveness of a nurse-led intensive home-visitation programme for first-time teenage mothers (Building Blocks): A pragmatic randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 387(10014), 146–155. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00392-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers J., Kelly U. A. (2011). Feminist intersectionality: Bringing social justice to health disparities research. Nursing Ethics, 18(3), 397–407. 10.1177/0969733011398094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruddell R., Lithopoulos S. (2016). Policing rural Canada. In Donnermeyer J. F. (Ed.), The Routledge international handbook of rural criminology (pp. 399–408). Routledge [Google Scholar]

- Russell D., Rosati R. J., Rosenfeld P., Marren J. M. (2011). Continuity in home health care: Is consistency in nursing personnel associated with better patient outcomes? Journal for Healthcare Quality, 33(6), 33–39. 10.1111/j.1945-1474.2011.00131.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheim A. I., Bauer G. R. (2019). The Intersectional Discrimination Index: Development and validation of measures of self-reported enacted and anticipated discrimination for intercategorical analysis. Social Science & Medicine, 226, 225–235. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.12.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherns R., Bourgeault I. L. (2008). Accessing maternity care in rural Canada: There’s more to the story than distance to a doctor. Health Care for Women International, 29(8), 863–883. 10.1080/07399330802269568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorne S. (2014). Applied interpretive approaches. In Leavy P. (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of qualitative research. 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199811755.013.002 [DOI]

- Thorne S. (2016). Interpretive description: Qualitative research for applied practice (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Thorne S., Kirkham S. R., O’Flynn-Magee K. (2004). The analytic challenge in interpretive description. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 3(1), 1–11. 10.1177/160940690400300101 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wong M., Saari M., Patterson E., Puts M., Tourangeau A. E. (2017). Occupational hazards for home care nurses across the rural-to-urban gradient in Ontario, Canada. Health & Social Care in the Community, 25(3), 1276–1286. 10.1111/hsc.12430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, Supplementary_file_1 for Nurse-Family Partnership and Geography: An Intersectional Perspective by Karen A. Campbell, Karen MacKinnon, Maureen Dobbins and Susan M. Jack in Global Qualitative Nursing Research